- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Visual Representation

What is visual representation.

Visual Representation refers to the principles by which markings on a surface are made and interpreted. Designers use representations like typography and illustrations to communicate information, emotions and concepts. Color, imagery, typography and layout are crucial in this communication.

Alan Blackwell, cognition scientist and professor, gives a brief introduction to visual representation:

- Transcript loading…

We can see visual representation throughout human history, from cave drawings to data visualization :

Art uses visual representation to express emotions and abstract ideas.

Financial forecasting graphs condense data and research into a more straightforward format.

Icons on user interfaces (UI) represent different actions users can take.

The color of a notification indicates its nature and meaning.

Van Gogh's "The Starry Night" uses visuals to evoke deep emotions, representing an abstract, dreamy night sky. It exemplifies how art can communicate complex feelings and ideas.

© Public domain

Importance of Visual Representation in Design

Designers use visual representation for internal and external use throughout the design process . For example:

Storyboards are illustrations that outline users’ actions and where they perform them.

Sitemaps are diagrams that show the hierarchy and navigation structure of a website.

Wireframes are sketches that bring together elements of a user interface's structure.

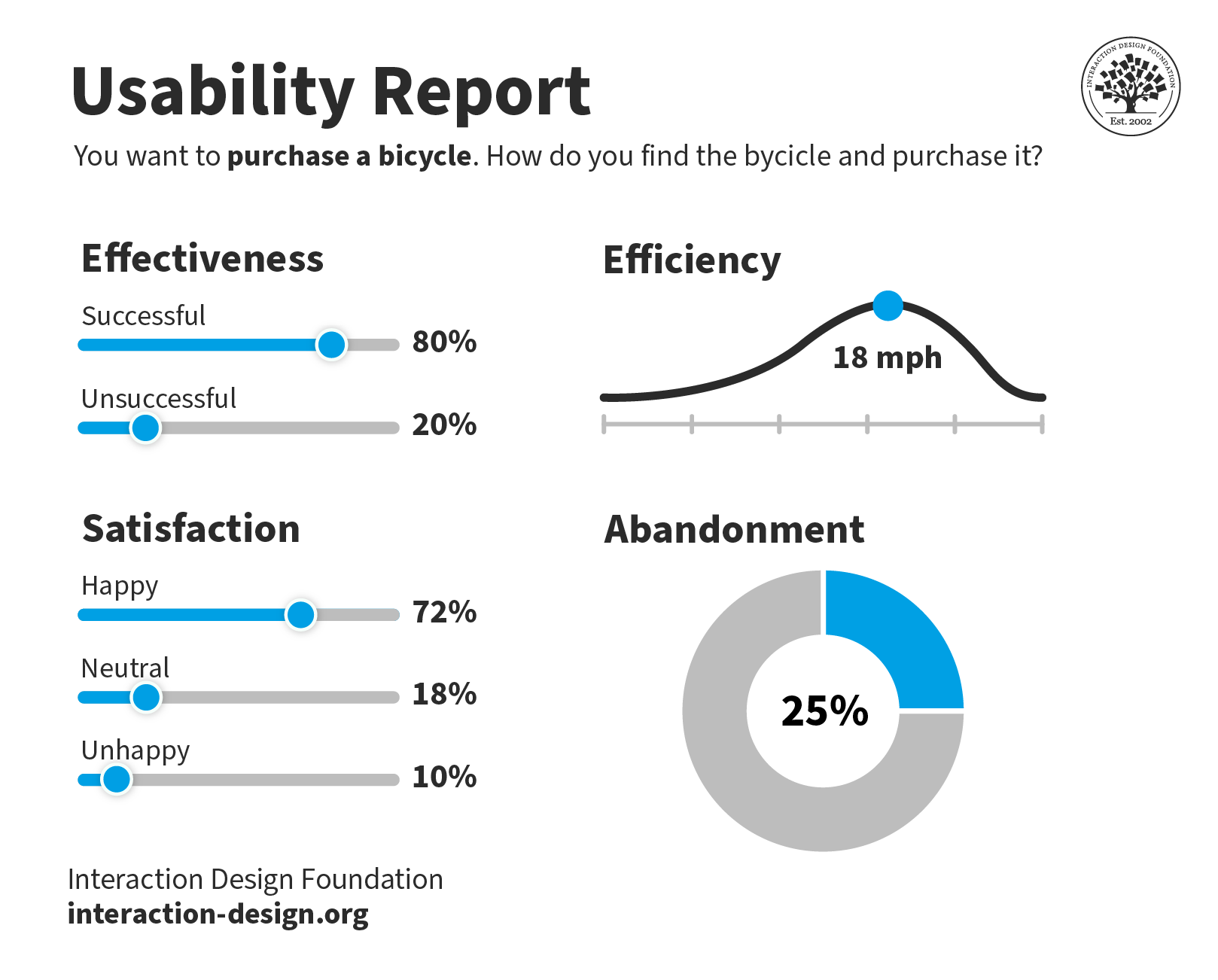

Usability reports use graphs and charts to communicate data gathered from usability testing.

User interfaces visually represent information contained in applications and computerized devices.

This usability report is straightforward to understand. Yet, the data behind the visualizations could come from thousands of answered surveys.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

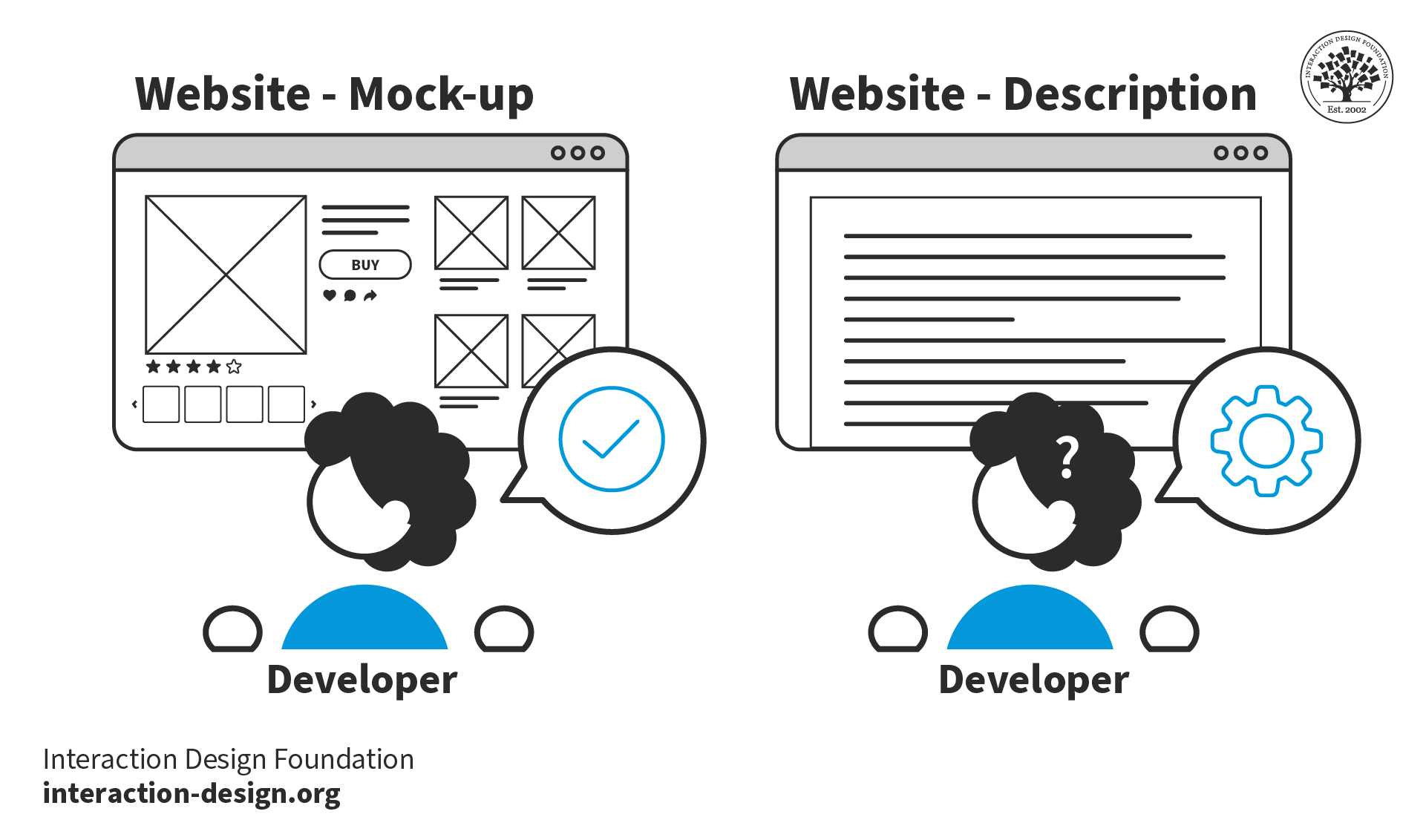

Visual representation simplifies complex ideas and data and makes them easy to understand. Without these visual aids, designers would struggle to communicate their ideas, findings and products . For example, it would be easier to create a mockup of an e-commerce website interface than to describe it with words.

Visual representation simplifies the communication of designs. Without mockups, it would be difficult for developers to reproduce designs using words alone.

Types of Visual Representation

Below are some of the most common forms of visual representation designers use.

Text and Typography

Text represents language and ideas through written characters and symbols. Readers visually perceive and interpret these characters. Typography turns text into a visual form, influencing its perception and interpretation.

We have developed the conventions of typography over centuries , for example, in documents, newspapers and magazines. These conventions include:

Text arranged on a grid brings clarity and structure. Gridded text makes complex information easier to navigate and understand. Tables, columns and other formats help organize content logically and enhance readability.

Contrasting text sizes create a visual hierarchy and draw attention to critical areas. For example, headings use larger text while body copy uses smaller text. This contrast helps readers distinguish between primary and secondary information.

Adequate spacing and paragraphing improve the readability and appearance of the text. These conventions prevent the content from appearing cluttered. Spacing and paragraphing make it easier for the eye to follow and for the brain to process the information.

Balanced image-to-text ratios create engaging layouts. Images break the monotony of text, provide visual relief and illustrate or emphasize points made in the text. A well-planned ratio ensures neither text nor images overwhelm each other. Effective ratios make designs more effective and appealing.

Designers use these conventions because people are familiar with them and better understand text presented in this manner.

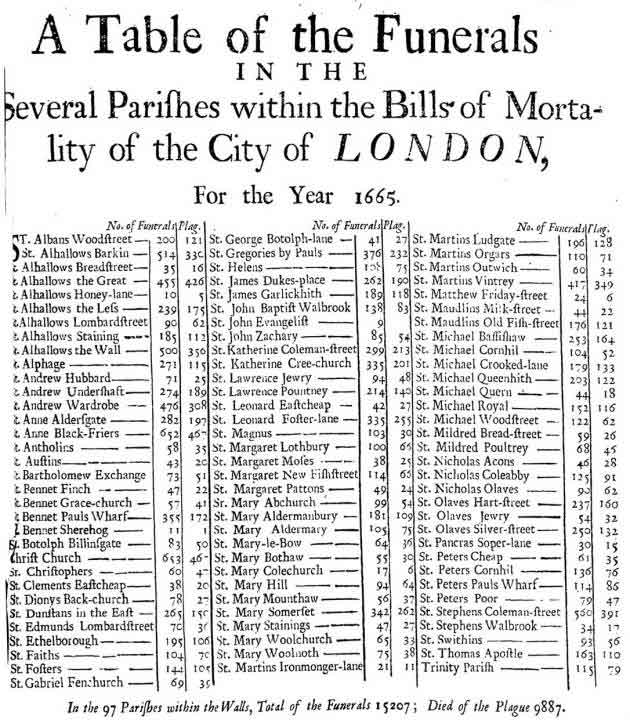

This table of funerals from the plague in London in 1665 uses typographic conventions still used today. For example, the author arranged the information in a table and used contrasting text styling to highlight information in the header.

Illustrations and Drawings

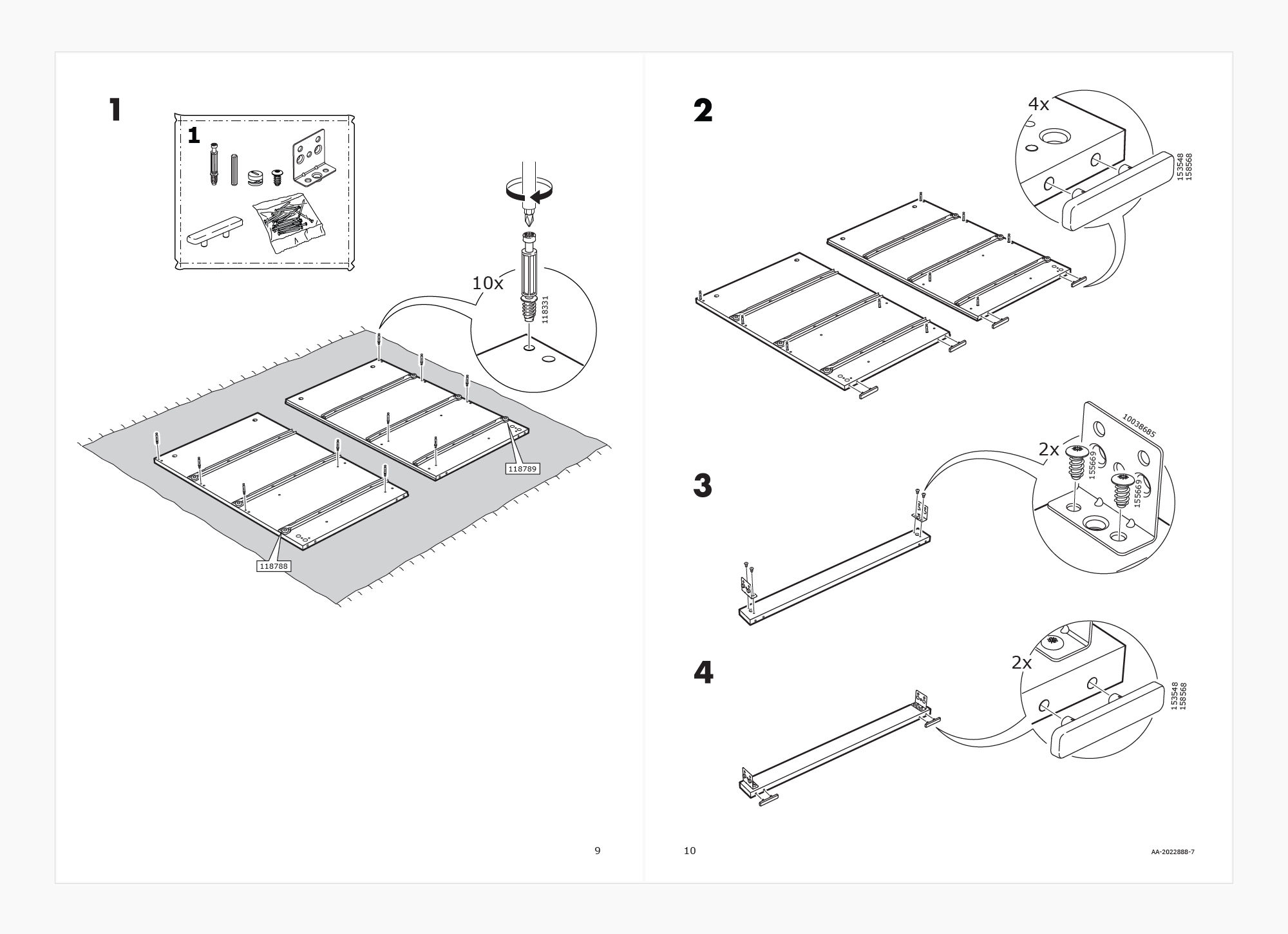

Designers use illustrations and drawings independently or alongside text. An example of illustration used to communicate information is the assembly instructions created by furniture retailer IKEA. If IKEA used text instead of illustrations in their instructions, people would find it harder to assemble the furniture.

IKEA assembly instructions use illustrations to inform customers how to build their furniture. The only text used is numeric to denote step and part numbers. IKEA communicates this information visually to: 1. Enable simple communication, 2. Ensure their instructions are easy to follow, regardless of the customer’s language.

© IKEA, Fair use

Illustrations and drawings can often convey the core message of a visual representation more effectively than a photograph. They focus on the core message , while a photograph might distract a viewer with additional details (such as who this person is, where they are from, etc.)

For example, in IKEA’s case, photographing a person building a piece of furniture might be complicated. Further, photographs may not be easy to understand in a black-and-white print, leading to higher printing costs. To be useful, the pictures would also need to be larger and would occupy more space on a printed manual, further adding to the costs.

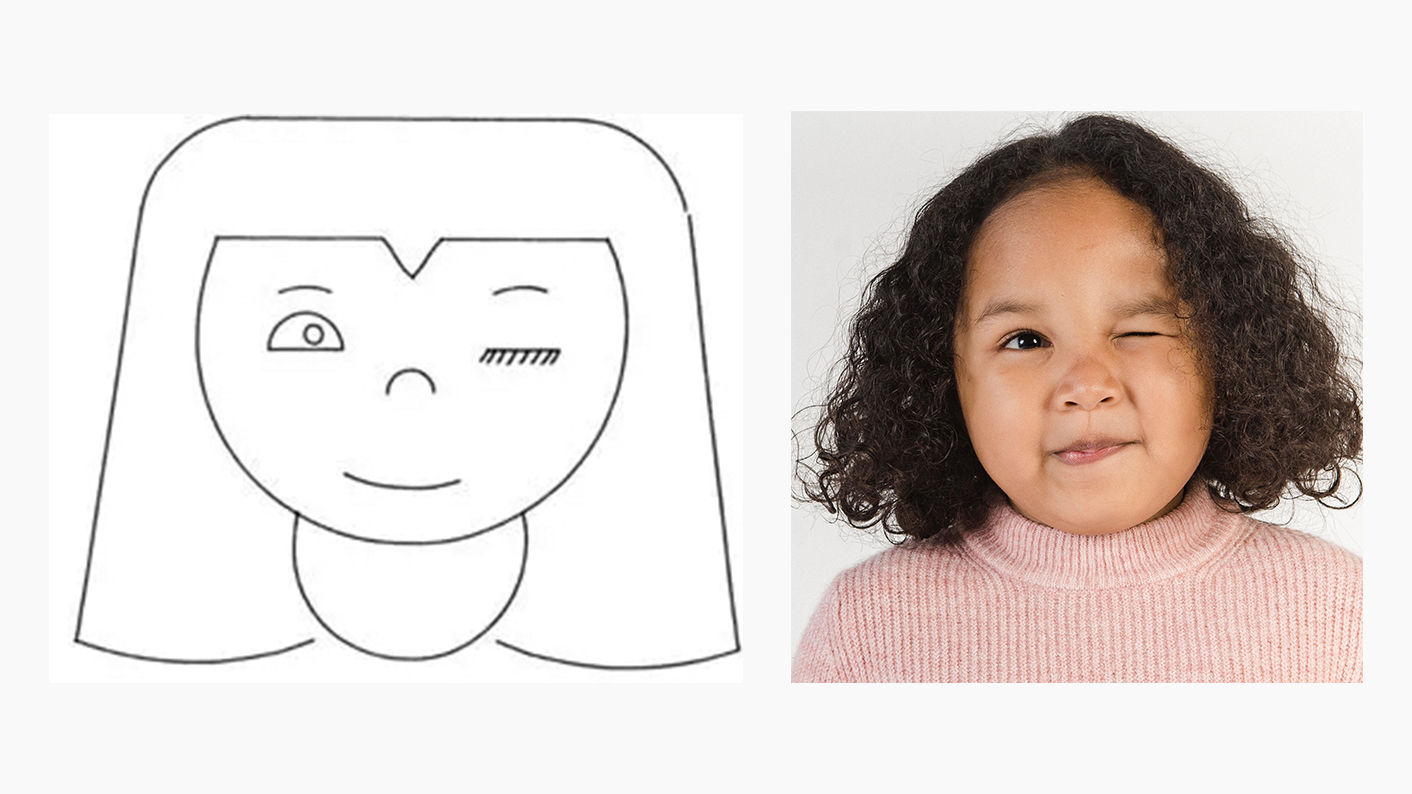

But imagine a girl winking—this is something we can easily photograph.

Ivan Sutherland, creator of the first graphical user interface, used his computer program Sketchpad to draw a winking girl. While not realistic, Sutherland's representation effectively portrays a winking girl. The drawing's abstract, generic elements contrast with the distinct winking eye. The graphical conventions of lines and shapes represent the eyes and mouth. The simplicity of the drawing does not draw attention away from the winking.

A photo might distract from the focused message compared to Sutherland's representation. In the photo, the other aspects of the image (i.e., the particular person) distract the viewer from this message.

© Ivan Sutherland, CC BY-SA 3.0 and Amina Filkins, Pexels License

Information and Data Visualization

Designers and other stakeholders use data and information visualization across many industries.

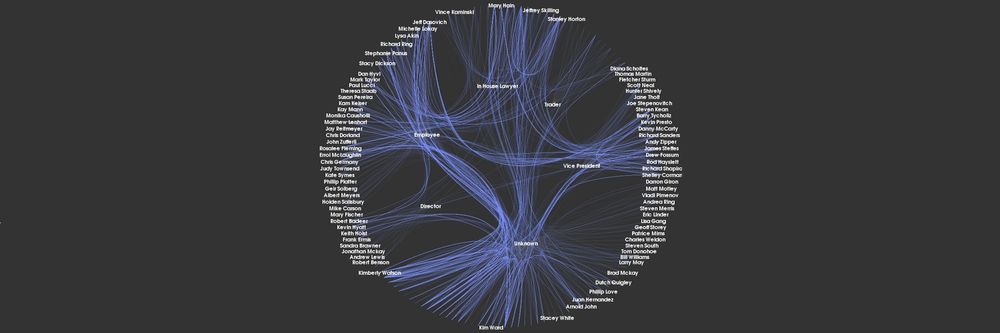

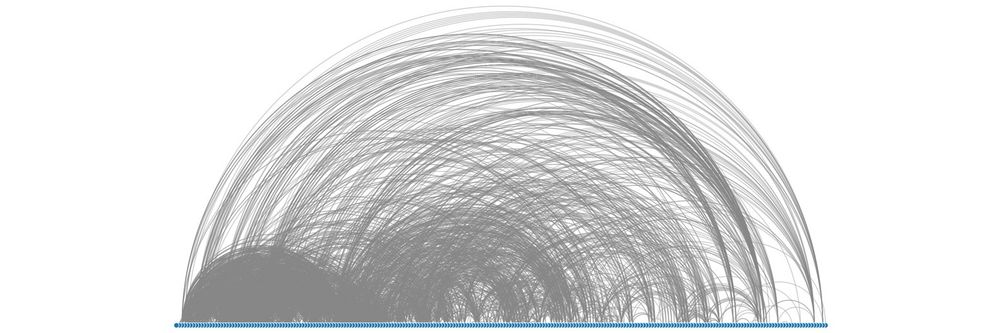

Data visualization uses charts and graphs to show raw data in a graphic form. Information visualization goes further, including more context and complex data sets. Information visualization often uses interactive elements to share a deeper understanding.

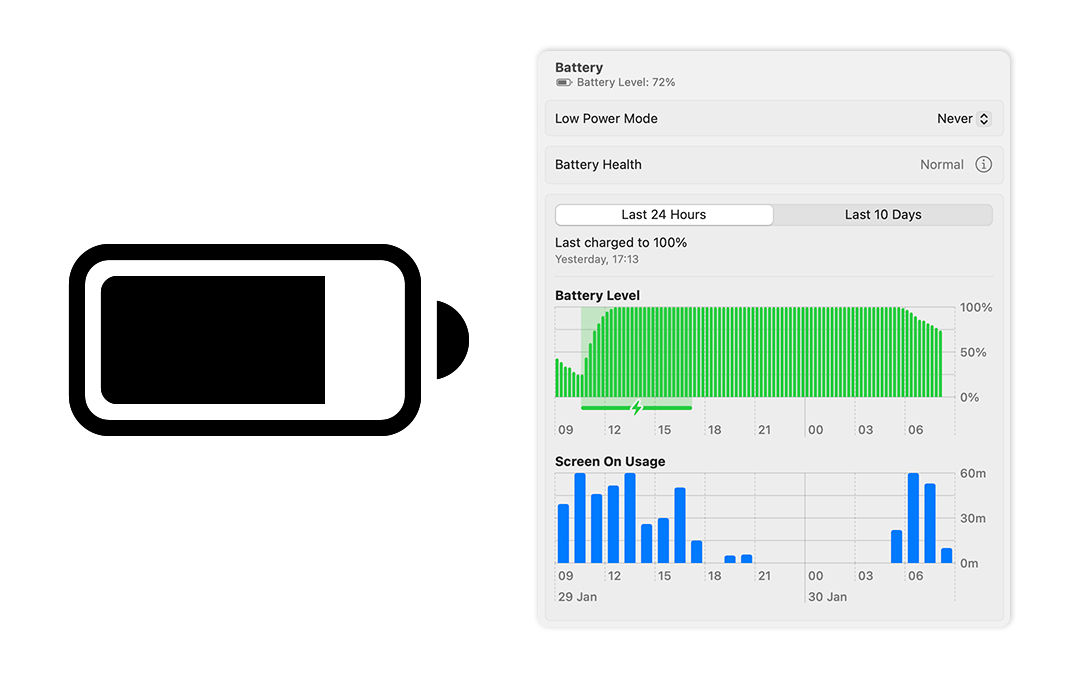

For example, most computerized devices have a battery level indicator. This is a type of data visualization. IV takes this further by allowing you to click on the battery indicator for further insights. These insights may include the apps that use the most battery and the last time you charged your device.

macOS displays a battery icon in the menu bar that visualizes your device’s battery level. This is an example of data visualization. Meanwhile, macOS’s settings tell you battery level over time, screen-on-usage and when you last charged your device. These insights are actionable; users may notice their battery drains at a specific time. This is an example of information visualization.

© Low Battery by Jemis Mali, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0, and Apple, Fair use

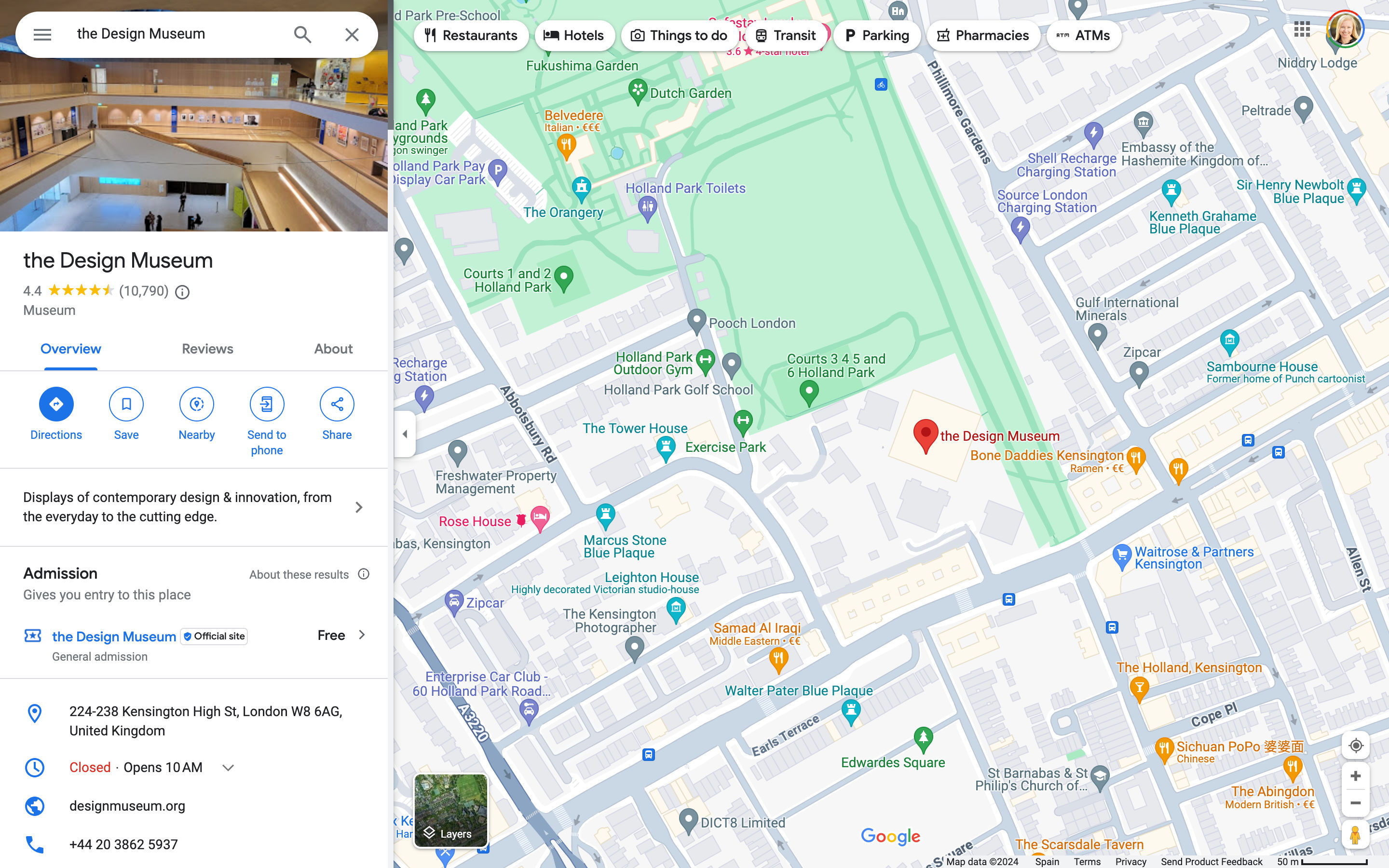

Information visualization is not exclusive to numeric data. It encompasses representations like diagrams and maps. For example, Google Maps collates various types of data and information into one interface:

Data Representation: Google Maps transforms complex geographical data into an easily understandable and navigable visual map.

Interactivity: Users can interactively customize views that show traffic, satellite imagery and more in real-time.

Layered Information: Google Maps layers multiple data types (e.g., traffic, weather) over geographical maps for comprehensive visualization.

User-Centered Design : The interface is intuitive and user-friendly, with symbols and colors for straightforward data interpretation.

The volume of data contained in one screenshot of Google Maps is massive. However, this information is presented clearly to the user. Google Maps highlights different terrains with colors and local places and businesses with icons and colors. The panel on the left lists the selected location’s profile, which includes an image, rating and contact information.

© Google, Fair use

Symbolic Correspondence

Symbolic correspondence uses universally recognized symbols and signs to convey specific meanings . This method employs widely recognized visual cues for immediate understanding. Symbolic correspondence removes the need for textual explanation.

For instance, a magnifying glass icon in UI design signifies the search function. Similarly, in environmental design, symbols for restrooms, parking and amenities guide visitors effectively.

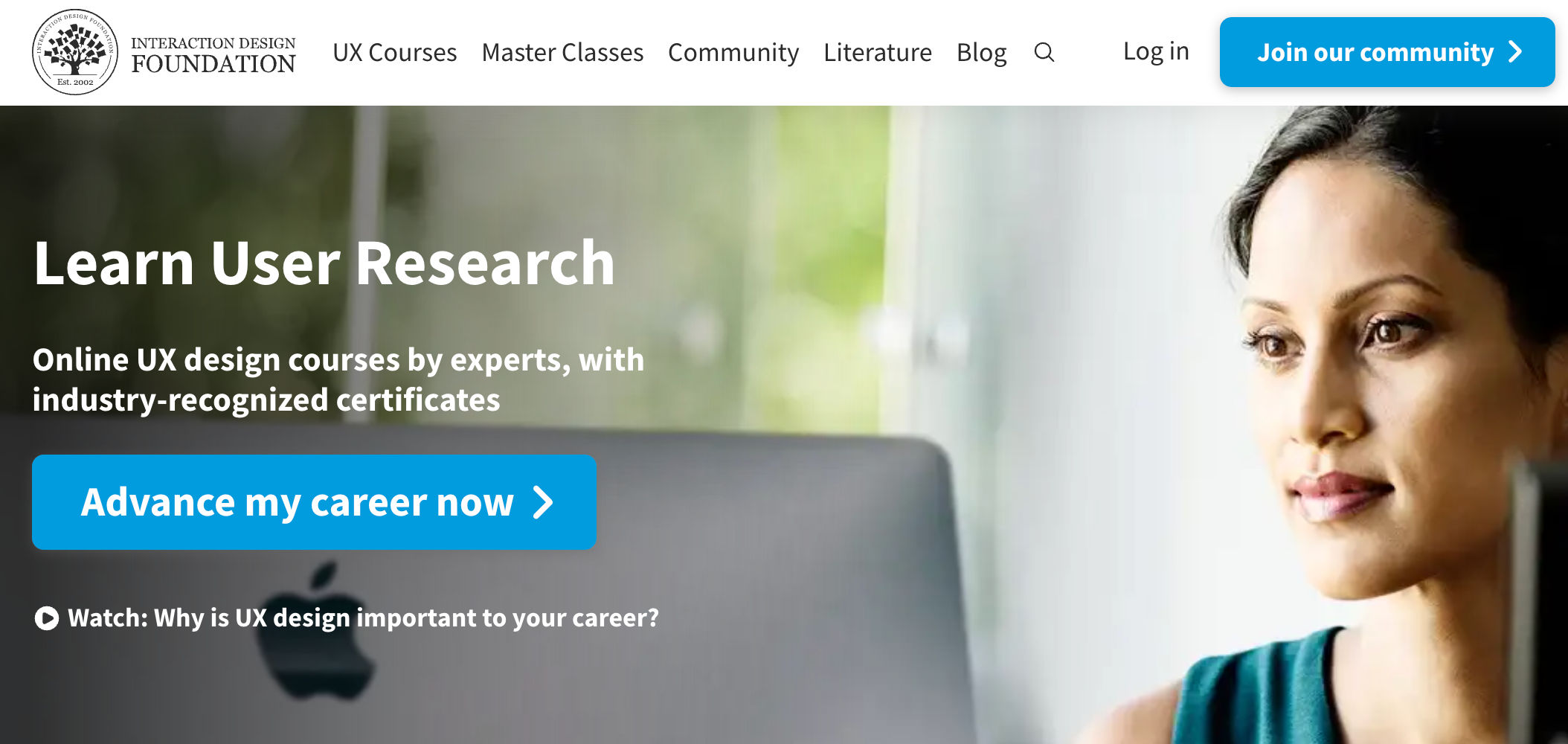

The Interaction Design Foundation (IxDF) website uses the universal magnifying glass symbol to signify the search function. Similarly, the play icon draws attention to a link to watch a video.

How Designers Create Visual Representations

Visual language.

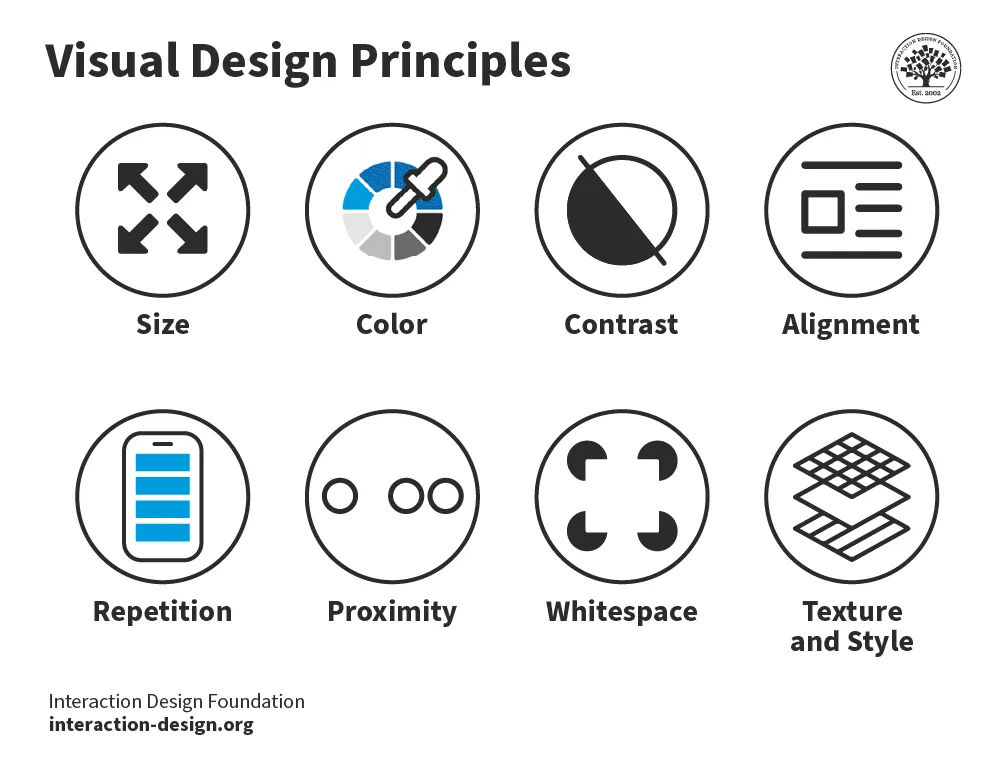

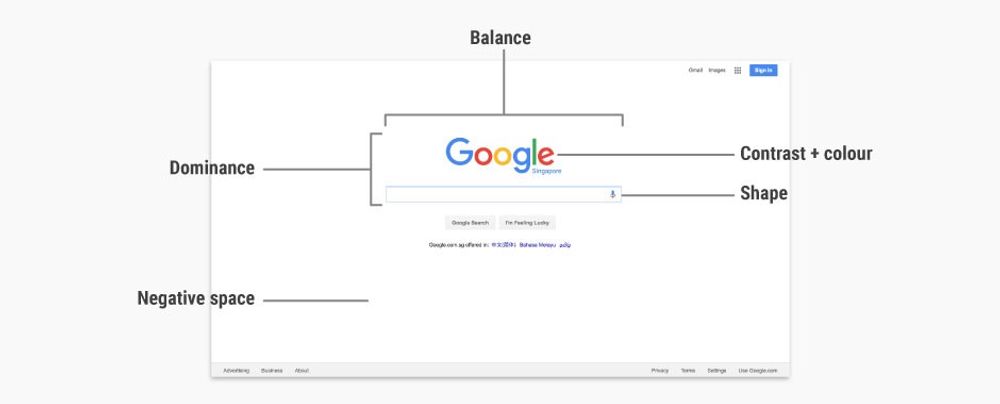

Designers use elements like color , shape and texture to create a communicative visual experience. Designers use these 8 principles:

Size – Larger elements tend to capture users' attention readily.

Color – Users are typically drawn to bright colors over muted shades.

Contrast – Colors with stark contrasts catch the eye more effectively.

Alignment – Unaligned elements are more noticeable than those aligned ones.

Repetition – Similar styles repeated imply a relationship in content.

Proximity – Elements placed near each other appear to be connected.

Whitespace – Elements surrounded by ample space attract the eye.

Texture and Style – Users often notice richer textures before flat designs.

The 8 visual design principles.

In web design , visual hierarchy uses color and repetition to direct the user's attention. Color choice is crucial as it creates contrast between different elements. Repetition helps to organize the design—it uses recurring elements to establish consistency and familiarity.

In this video, Alan Dix, Professor and Expert in Human-Computer Interaction, explains how visual alignment affects how we read and absorb information:

Correspondence Techniques

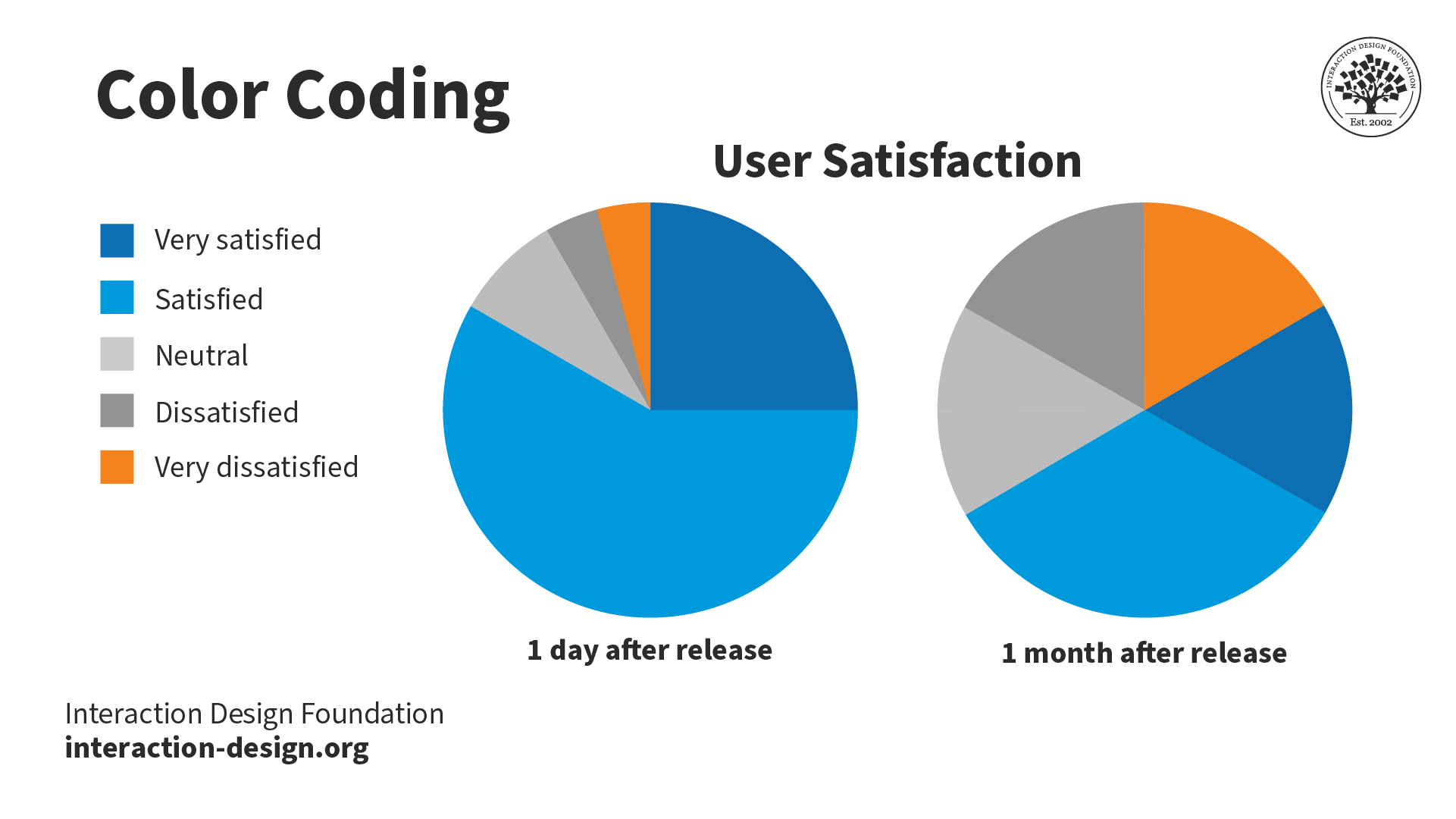

Designers use correspondence techniques to align visual elements with their conceptual meanings. These techniques include color coding, spatial arrangement and specific imagery. In information visualization, different colors can represent various data sets. This correspondence aids users in quickly identifying trends and relationships .

Color coding enables the stakeholder to see the relationship and trend between the two pie charts easily.

In user interface design, correspondence techniques link elements with meaning. An example is color-coding notifications to state their nature. For instance, red for warnings and green for confirmation. These techniques are informative and intuitive and enhance the user experience.

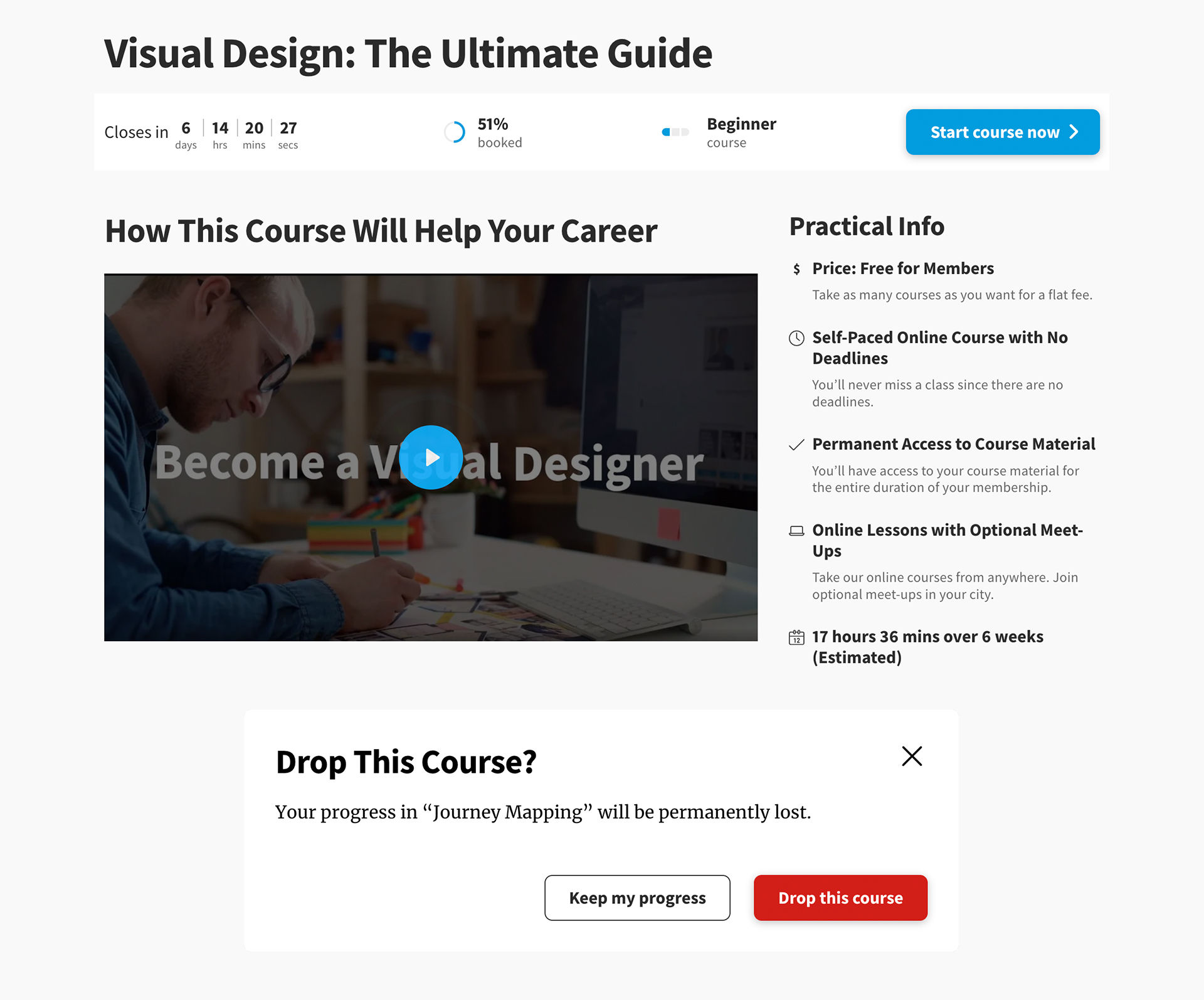

The IxDF website uses blue for call-to-actions (CTAs) and red for warnings. These colors inform the user of the nature of the action of buttons and other interactive elements.

Perception and Interpretation

If visual language is how designers create representations, then visual perception and interpretation are how users receive those representations. Consider a painting—the viewer’s eyes take in colors, shapes and lines, and the brain perceives these visual elements as a painting.

In this video, Alan Dix explains how the interplay of sensation, perception and culture is crucial to understanding visual experiences in design:

Copyright holder: Michael Murphy _ Appearance time: 07:19 - 07:37 _ Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C67JuZnBBDc

Visual perception principles are essential for creating compelling, engaging visual representations. For example, Gestalt principles explain how we perceive visual information. These rules describe how we group similar items, spot patterns and simplify complex images. Designers apply Gestalt principles to arrange content on websites and other interfaces. This application creates visually appealing and easily understood designs.

In this video, design expert and teacher Mia Cinelli discusses the significance of Gestalt principles in visual design . She introduces fundamental principles, like figure/ground relationships, similarity and proximity.

Interpretation

Everyone's experiences, culture and physical abilities dictate how they interpret visual representations. For this reason, designers carefully consider how users interpret their visual representations. They employ user research and testing to ensure their designs are attractive and functional.

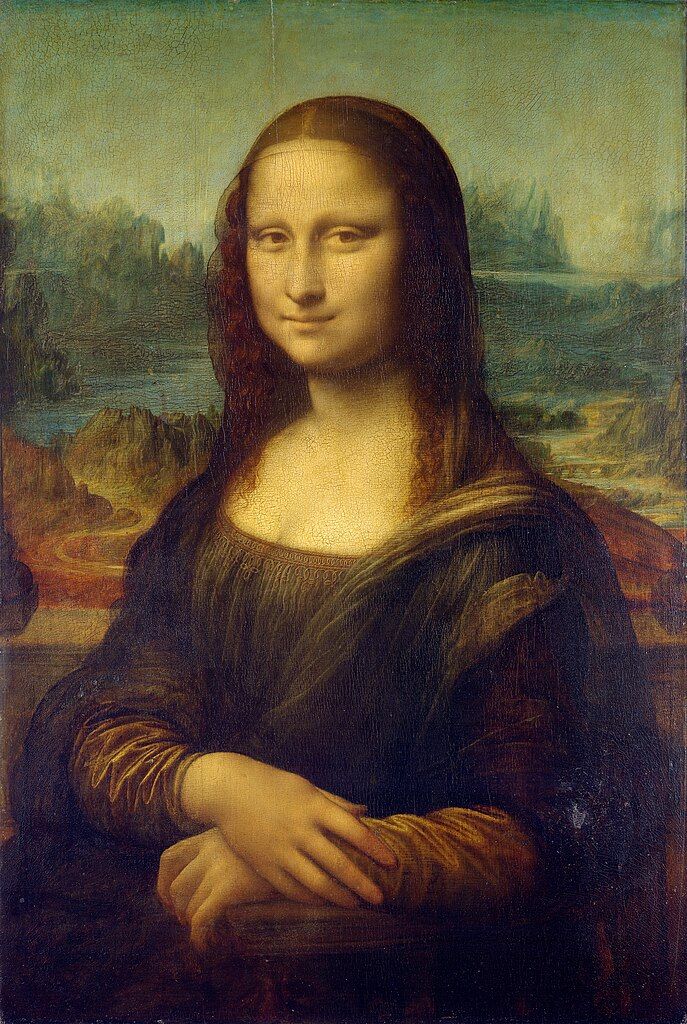

Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa", is one of the most famous paintings in the world. The piece is renowned for its subject's enigmatic expression. Some interpret her smile as content and serene, while others see it as sad or mischievous. Not everyone interprets this visual representation in the same way.

Color is an excellent example of how one person, compared to another, may interpret a visual element. Take the color red:

In Chinese culture, red symbolizes luck, while in some parts of Africa, it can mean death or illness.

A personal experience may mean a user has a negative or positive connotation with red.

People with protanopia and deuteranopia color blindness cannot distinguish between red and green.

In this video, Joann and Arielle Eckstut, leading color consultants and authors, explain how many factors influence how we perceive and interpret color:

Learn More about Visual Representation

Read Alan Blackwell’s chapter on visual representation from The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction.

Learn about the F-Shaped Pattern For Reading Web Content from Jakob Nielsen.

Read Smashing Magazine’s article, Visual Design Language: The Building Blocks Of Design .

Take the IxDF’s course, Perception and Memory in HCI and UX .

Questions related to Visual Representation

Some highly cited research on visual representation and related topics includes:

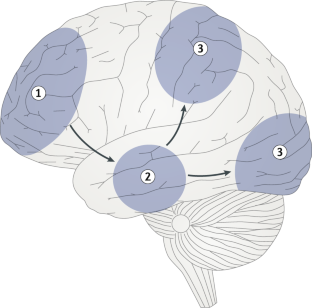

Roland, P. E., & Gulyás, B. (1994). Visual imagery and visual representation. Trends in Neurosciences, 17(7), 281-287. Roland and Gulyás' study explores how the brain creates visual imagination. They look at whether imagining things like objects and scenes uses the same parts of the brain as seeing them does. Their research shows the brain uses certain areas specifically for imagination. These areas are different from the areas used for seeing. This research is essential for understanding how our brain works with vision.

Lurie, N. H., & Mason, C. H. (2007). Visual Representation: Implications for Decision Making. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 160-177.

This article looks at how visualization tools help in understanding complicated marketing data. It discusses how these tools affect decision-making in marketing. The article gives a detailed method to assess the impact of visuals on the study and combination of vast quantities of marketing data. It explores the benefits and possible biases visuals can bring to marketing choices. These factors make the article an essential resource for researchers and marketing experts. The article suggests using visual tools and detailed analysis together for the best results.

Lohse, G. L., Biolsi, K., Walker, N., & Rueter, H. H. (1994, December). A classification of visual representations. Communications of the ACM, 37(12), 36+.

This publication looks at how visuals help communicate and make information easier to understand. It divides these visuals into six types: graphs, tables, maps, diagrams, networks and icons. The article also looks at different ways these visuals share information effectively.

If you’d like to cite content from the IxDF website , click the ‘cite this article’ button near the top of your screen.

Some recommended books on visual representation and related topics include:

Chaplin, E. (1994). Sociology and Visual Representation (1st ed.) . Routledge.

Chaplin's book describes how visual art analysis has changed from ancient times to today. It shows how photography, post-modernism and feminism have changed how we see art. The book combines words and images in its analysis and looks into real-life social sciences studies.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (1994). Picture Theory. The University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell's book explores the important role and meaning of pictures in the late twentieth century. It discusses the change from focusing on language to focusing on images in cultural studies. The book deeply examines the interaction between images and text in different cultural forms like literature, art and media. This detailed study of how we see and read visual representations has become an essential reference for scholars and professionals.

Koffka, K. (1935). Principles of Gestalt Psychology. Harcourt, Brace & World.

"Principles of Gestalt Psychology" by Koffka, released in 1935, is a critical book in its field. It's known as a foundational work in Gestalt psychology, laying out the basic ideas of the theory and how they apply to how we see and think. Koffka's thorough study of Gestalt psychology's principles has profoundly influenced how we understand human perception. This book has been a significant reference in later research and writings.

A visual representation, like an infographic or chart, uses visual elements to show information or data. These types of visuals make complicated information easier to understand and more user-friendly.

Designers harness visual representations in design and communication. Infographics and charts, for instance, distill data for easier audience comprehension and retention.

For an introduction to designing basic information visualizations, take our course, Information Visualization .

Text is a crucial design and communication element, transforming language visually. Designers use font style, size, color and layout to convey emotions and messages effectively.

Designers utilize text for both literal communication and aesthetic enhancement. Their typography choices significantly impact design aesthetics, user experience and readability.

Designers should always consider text's visual impact in their designs. This consideration includes font choice, placement, color and interaction with other design elements.

In this video, design expert and teacher Mia Cinelli teaches how Gestalt principles apply to typography:

Designers use visual elements in projects to convey information, ideas, and messages. Designers use images, colors, shapes and typography for impactful designs.

In UI/UX design, visual representation is vital. Icons, buttons and colors provide contrast for intuitive, user-friendly website and app interfaces.

Graphic design leverages visual representation to create attention-grabbing marketing materials. Careful color, imagery and layout choices create an emotional connection.

Product design relies on visual representation for prototyping and idea presentation. Designers and stakeholders use visual representations to envision functional, aesthetically pleasing products.

Our brains process visuals 60,000 times faster than text. This fact highlights the crucial role of visual representation in design.

Our course, Visual Design: The Ultimate Guide , teaches you how to use visual design elements and principles in your work effectively.

Visual representation, crucial in UX, facilitates interaction, comprehension and emotion. It combines elements like images and typography for better interfaces.

Effective visuals guide users, highlight features and improve navigation. Icons and color schemes communicate functions and set interaction tones.

UX design research shows visual elements significantly impact emotions. 90% of brain-transmitted information is visual.

To create functional, accessible visuals, designers use color contrast and consistent iconography. These elements improve readability and inclusivity.

An excellent example of visual representation in UX is Apple's iOS interface. iOS combines a clean, minimalist design with intuitive navigation. As a result, the operating system is both visually appealing and user-friendly.

Michal Malewicz, Creative Director and CEO at Hype4, explains why visual skills are important in design:

Learn more about UI design from Michal in our Master Class, Beyond Interfaces: The UI Design Skills You Need to Know .

The fundamental principles of effective visual representation are:

Clarity : Designers convey messages clearly, avoiding clutter.

Simplicity : Embrace simple designs for ease and recall.

Emphasis : Designers highlight key elements distinctively.

Balance : Balance ensures design stability and structure.

Alignment : Designers enhance coherence through alignment.

Contrast : Use contrast for dynamic, distinct designs.

Repetition : Repeating elements unify and guide designs.

Designers practice these principles in their projects. They also analyze successful designs and seek feedback to improve their skills.

Read our topic description of Gestalt principles to learn more about creating effective visual designs. The Gestalt principles explain how humans group elements, recognize patterns and simplify object perception.

Color theory is vital in design, helping designers craft visually appealing and compelling works. Designers understand color interactions, psychological impacts and symbolism. These elements help designers enhance communication and guide attention.

Designers use complementary , analogous and triadic colors for contrast, harmony and balance. Understanding color temperature also plays a crucial role in design perception.

Color symbolism is crucial, as different colors can represent specific emotions and messages. For instance, blue can symbolize trust and calmness, while red can indicate energy and urgency.

Cultural variations significantly influence color perception and symbolism. Designers consider these differences to ensure their designs resonate with diverse audiences.

For actionable insights, designers should:

Experiment with color schemes for effective messaging.

Assess colors' psychological impact on the audience.

Use color contrast to highlight critical elements.

Ensure color choices are accessible to all.

In this video, Joann and Arielle Eckstut, leading color consultants and authors, give their six tips for choosing color:

Learn more about color from Joann and Arielle in our Master Class, How To Use Color Theory To Enhance Your Designs .

Typography and font choice are crucial in design, impacting readability and mood. Designers utilize them for effective communication and expression.

Designers' perception of information varies with font type. Serif fonts can imply formality, while sans-serifs can give a more modern look.

Typography choices by designers influence readability and user experience. Well-spaced, distinct fonts enhance readability, whereas decorative fonts may hinder it.

Designers use typography to evoke emotions and set a design's tone. Choices in font size, style and color affect the emotional impact and message clarity.

Designers use typography to direct attention, create hierarchy and establish rhythm. These benefits help with brand recognition and consistency across mediums.

Read our article to learn how web fonts are critical to the online user experience .

Designers create a balance between simplicity and complexity in their work. They focus on the main messages and highlight important parts. Designers use the principles of visual hierarchy, like size, color and spacing. They also use empty space to make their designs clear and understandable.

The Gestalt law of Prägnanz suggests people naturally simplify complex images. This principle aids in making even intricate information accessible and engaging.

Through iteration and feedback, designers refine visuals. They remove extraneous elements and highlight vital information. Testing with the target audience ensures the design resonates and is comprehensible.

Michal Malewicz explains how to master hierarchy in UI design using the Gestalt rule of proximity:

Literature on Visual Representation

Here’s the entire UX literature on Visual Representation by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Visual Representation

Take a deep dive into Visual Representation with our course Perception and Memory in HCI and UX .

How does all of this fit with interaction design and user experience? The simple answer is that most of our understanding of human experience comes from our own experiences and just being ourselves. That might extend to people like us, but it gives us no real grasp of the whole range of human experience and abilities. By considering more closely how humans perceive and interact with our world, we can gain real insights into what designs will work for a broader audience: those younger or older than us, more or less capable, more or less skilled and so on.

“You can design for all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot design for all the people all the time.“ – William Hudson (with apologies to Abraham Lincoln)

While “design for all of the people all of the time” is an impossible goal, understanding how the human machine operates is essential to getting ever closer. And of course, building solutions for people with a wide range of abilities, including those with accessibility issues, involves knowing how and why some human faculties fail. As our course tutor, Professor Alan Dix, points out, this is not only a moral duty but, in most countries, also a legal obligation.

Portfolio Project

In the “ Build Your Portfolio: Perception and Memory Project ”, you’ll find a series of practical exercises that will give you first-hand experience in applying what we’ll cover. If you want to complete these optional exercises, you’ll create a series of case studies for your portfolio which you can show your future employer or freelance customers.

This in-depth, video-based course is created with the amazing Alan Dix , the co-author of the internationally best-selling textbook Human-Computer Interaction and a superstar in the field of Human-Computer Interaction . Alan is currently a professor and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Gain an Industry-Recognized UX Course Certificate

Use your industry-recognized Course Certificate on your resume , CV , LinkedIn profile or your website.

All open-source articles on Visual Representation

Data visualization for human perception.

The Key Elements & Principles of Visual Design

- 1.1k shares

Guidelines for Good Visual Information Representations

- 4 years ago

Philosophy of Interaction

Information visualization – an introduction to multivariate analysis.

- 8 years ago

Aesthetic Computing

How to represent linear data visually for information visualization.

- 5 years ago

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

- Open access

- Published: 19 July 2015

The role of visual representations in scientific practices: from conceptual understanding and knowledge generation to ‘seeing’ how science works

- Maria Evagorou 1 ,

- Sibel Erduran 2 &

- Terhi Mäntylä 3

International Journal of STEM Education volume 2 , Article number: 11 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

73k Accesses

78 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

The use of visual representations (i.e., photographs, diagrams, models) has been part of science, and their use makes it possible for scientists to interact with and represent complex phenomena, not observable in other ways. Despite a wealth of research in science education on visual representations, the emphasis of such research has mainly been on the conceptual understanding when using visual representations and less on visual representations as epistemic objects. In this paper, we argue that by positioning visual representations as epistemic objects of scientific practices, science education can bring a renewed focus on how visualization contributes to knowledge formation in science from the learners’ perspective.

This is a theoretical paper, and in order to argue about the role of visualization, we first present a case study, that of the discovery of the structure of DNA that highlights the epistemic components of visual information in science. The second case study focuses on Faraday’s use of the lines of magnetic force. Faraday is known of his exploratory, creative, and yet systemic way of experimenting, and the visual reasoning leading to theoretical development was an inherent part of the experimentation. Third, we trace a contemporary account from science focusing on the experimental practices and how reproducibility of experimental procedures can be reinforced through video data.

Conclusions

Our conclusions suggest that in teaching science, the emphasis in visualization should shift from cognitive understanding—using the products of science to understand the content—to engaging in the processes of visualization. Furthermore, we suggest that is it essential to design curriculum materials and learning environments that create a social and epistemic context and invite students to engage in the practice of visualization as evidence, reasoning, experimental procedure, or a means of communication and reflect on these practices. Implications for teacher education include the need for teacher professional development programs to problematize the use of visual representations as epistemic objects that are part of scientific practices.

During the last decades, research and reform documents in science education across the world have been calling for an emphasis not only on the content but also on the processes of science (Bybee 2014 ; Eurydice 2012 ; Duschl and Bybee 2014 ; Osborne 2014 ; Schwartz et al. 2012 ), in order to make science accessible to the students and enable them to understand the epistemic foundation of science. Scientific practices, part of the process of science, are the cognitive and discursive activities that are targeted in science education to develop epistemic understanding and appreciation of the nature of science (Duschl et al. 2008 ) and have been the emphasis of recent reform documents in science education across the world (Achieve 2013 ; Eurydice 2012 ). With the term scientific practices, we refer to the processes that take place during scientific discoveries and include among others: asking questions, developing and using models, engaging in arguments, and constructing and communicating explanations (National Research Council 2012 ). The emphasis on scientific practices aims to move the teaching of science from knowledge to the understanding of the processes and the epistemic aspects of science. Additionally, by placing an emphasis on engaging students in scientific practices, we aim to help students acquire scientific knowledge in meaningful contexts that resemble the reality of scientific discoveries.

Despite a wealth of research in science education on visual representations, the emphasis of such research has mainly been on the conceptual understanding when using visual representations and less on visual representations as epistemic objects. In this paper, we argue that by positioning visual representations as epistemic objects, science education can bring a renewed focus on how visualization contributes to knowledge formation in science from the learners’ perspective. Specifically, the use of visual representations (i.e., photographs, diagrams, tables, charts) has been part of science and over the years has evolved with the new technologies (i.e., from drawings to advanced digital images and three dimensional models). Visualization makes it possible for scientists to interact with complex phenomena (Richards 2003 ), and they might convey important evidence not observable in other ways. Visual representations as a tool to support cognitive understanding in science have been studied extensively (i.e., Gilbert 2010 ; Wu and Shah 2004 ). Studies in science education have explored the use of images in science textbooks (i.e., Dimopoulos et al. 2003 ; Bungum 2008 ), students’ representations or models when doing science (i.e., Gilbert et al. 2008 ; Dori et al. 2003 ; Lehrer and Schauble 2012 ; Schwarz et al. 2009 ), and students’ images of science and scientists (i.e., Chambers 1983 ). Therefore, studies in the field of science education have been using the term visualization as “the formation of an internal representation from an external representation” (Gilbert et al. 2008 , p. 4) or as a tool for conceptual understanding for students.

In this paper, we do not refer to visualization as mental image, model, or presentation only (Gilbert et al. 2008 ; Philips et al. 2010 ) but instead focus on visual representations or visualization as epistemic objects. Specifically, we refer to visualization as a process for knowledge production and growth in science. In this respect, modeling is an aspect of visualization, but what we are focusing on with visualization is not on the use of model as a tool for cognitive understanding (Gilbert 2010 ; Wu and Shah 2004 ) but the on the process of modeling as a scientific practice which includes the construction and use of models, the use of other representations, the communication in the groups with the use of the visual representation, and the appreciation of the difficulties that the science phase in this process. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to present through the history of science how visualization can be considered not only as a cognitive tool in science education but also as an epistemic object that can potentially support students to understand aspects of the nature of science.

Scientific practices and science education

According to the New Generation Science Standards (Achieve 2013 ), scientific practices refer to: asking questions and defining problems; developing and using models; planning and carrying out investigations; analyzing and interpreting data; using mathematical and computational thinking; constructing explanations and designing solutions; engaging in argument from evidence; and obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information. A significant aspect of scientific practices is that science learning is more than just about learning facts, concepts, theories, and laws. A fuller appreciation of science necessitates the understanding of the science relative to its epistemological grounding and the process that are involved in the production of knowledge (Hogan and Maglienti 2001 ; Wickman 2004 ).

The New Generation Science Standards is, among other changes, shifting away from science inquiry and towards the inclusion of scientific practices (Duschl and Bybee 2014 ; Osborne 2014 ). By comparing the abilities to do scientific inquiry (National Research Council 2000 ) with the set of scientific practices, it is evident that the latter is about engaging in the processes of doing science and experiencing in that way science in a more authentic way. Engaging in scientific practices according to Osborne ( 2014 ) “presents a more authentic picture of the endeavor that is science” (p.183) and also helps the students to develop a deeper understanding of the epistemic aspects of science. Furthermore, as Bybee ( 2014 ) argues, by engaging students in scientific practices, we involve them in an understanding of the nature of science and an understanding on the nature of scientific knowledge.

Science as a practice and scientific practices as a term emerged by the philosopher of science, Kuhn (Osborne 2014 ), refers to the processes in which the scientists engage during knowledge production and communication. The work that is followed by historians, philosophers, and sociologists of science (Latour 2011 ; Longino 2002 ; Nersessian 2008 ) revealed the scientific practices in which the scientists engage in and include among others theory development and specific ways of talking, modeling, and communicating the outcomes of science.

Visualization as an epistemic object

Schematic, pictorial symbols in the design of scientific instruments and analysis of the perceptual and functional information that is being stored in those images have been areas of investigation in philosophy of scientific experimentation (Gooding et al. 1993 ). The nature of visual perception, the relationship between thought and vision, and the role of reproducibility as a norm for experimental research form a central aspect of this domain of research in philosophy of science. For instance, Rothbart ( 1997 ) has argued that visualizations are commonplace in the theoretical sciences even if every scientific theory may not be defined by visualized models.

Visual representations (i.e., photographs, diagrams, tables, charts, models) have been used in science over the years to enable scientists to interact with complex phenomena (Richards 2003 ) and might convey important evidence not observable in other ways (Barber et al. 2006 ). Some authors (e.g., Ruivenkamp and Rip 2010 ) have argued that visualization is as a core activity of some scientific communities of practice (e.g., nanotechnology) while others (e.g., Lynch and Edgerton 1988 ) have differentiated the role of particular visualization techniques (e.g., of digital image processing in astronomy). Visualization in science includes the complex process through which scientists develop or produce imagery, schemes, and graphical representation, and therefore, what is of importance in this process is not only the result but also the methodology employed by the scientists, namely, how this result was produced. Visual representations in science may refer to objects that are believed to have some kind of material or physical existence but equally might refer to purely mental, conceptual, and abstract constructs (Pauwels 2006 ). More specifically, visual representations can be found for: (a) phenomena that are not observable with the eye (i.e., microscopic or macroscopic); (b) phenomena that do not exist as visual representations but can be translated as such (i.e., sound); and (c) in experimental settings to provide visual data representations (i.e., graphs presenting velocity of moving objects). Additionally, since science is not only about replicating reality but also about making it more understandable to people (either to the public or other scientists), visual representations are not only about reproducing the nature but also about: (a) functioning in helping solving a problem, (b) filling gaps in our knowledge, and (c) facilitating knowledge building or transfer (Lynch 2006 ).

Using or developing visual representations in the scientific practice can range from a straightforward to a complicated situation. More specifically, scientists can observe a phenomenon (i.e., mitosis) and represent it visually using a picture or diagram, which is quite straightforward. But they can also use a variety of complicated techniques (i.e., crystallography in the case of DNA studies) that are either available or need to be developed or refined in order to acquire the visual information that can be used in the process of theory development (i.e., Latour and Woolgar 1979 ). Furthermore, some visual representations need decoding, and the scientists need to learn how to read these images (i.e., radiologists); therefore, using visual representations in the process of science requires learning a new language that is specific to the medium/methods that is used (i.e., understanding an X-ray picture is different from understanding an MRI scan) and then communicating that language to other scientists and the public.

There are much intent and purposes of visual representations in scientific practices, as for example to make a diagnosis, compare, describe, and preserve for future study, verify and explore new territory, generate new data (Pauwels 2006 ), or present new methodologies. According to Latour and Woolgar ( 1979 ) and Knorr Cetina ( 1999 ), visual representations can be used either as primary data (i.e., image from a microscope). or can be used to help in concept development (i.e., models of DNA used by Watson and Crick), to uncover relationships and to make the abstract more concrete (graphs of sound waves). Therefore, visual representations and visual practices, in all forms, are an important aspect of the scientific practices in developing, clarifying, and transmitting scientific knowledge (Pauwels 2006 ).

Methods and Results: Merging Visualization and scientific practices in science

In this paper, we present three case studies that embody the working practices of scientists in an effort to present visualization as a scientific practice and present our argument about how visualization is a complex process that could include among others modeling and use of representation but is not only limited to that. The first case study explores the role of visualization in the construction of knowledge about the structure of DNA, using visuals as evidence. The second case study focuses on Faraday’s use of the lines of magnetic force and the visual reasoning leading to the theoretical development that was an inherent part of the experimentation. The third case study focuses on the current practices of scientists in the context of a peer-reviewed journal called the Journal of Visualized Experiments where the methodology is communicated through videotaped procedures. The three case studies represent the research interests of the three authors of this paper and were chosen to present how visualization as a practice can be involved in all stages of doing science, from hypothesizing and evaluating evidence (case study 1) to experimenting and reasoning (case study 2) to communicating the findings and methodology with the research community (case study 3), and represent in this way the three functions of visualization as presented by Lynch ( 2006 ). Furthermore, the last case study showcases how the development of visualization technologies has contributed to the communication of findings and methodologies in science and present in that way an aspect of current scientific practices. In all three cases, our approach is guided by the observation that the visual information is an integral part of scientific practices at the least and furthermore that they are particularly central in the scientific practices of science.

Case study 1: use visual representations as evidence in the discovery of DNA

The focus of the first case study is the discovery of the structure of DNA. The DNA was first isolated in 1869 by Friedrich Miescher, and by the late 1940s, it was known that it contained phosphate, sugar, and four nitrogen-containing chemical bases. However, no one had figured the structure of the DNA until Watson and Crick presented their model of DNA in 1953. Other than the social aspects of the discovery of the DNA, another important aspect was the role of visual evidence that led to knowledge development in the area. More specifically, by studying the personal accounts of Watson ( 1968 ) and Crick ( 1988 ) about the discovery of the structure of the DNA, the following main ideas regarding the role of visual representations in the production of knowledge can be identified: (a) The use of visual representations was an important part of knowledge growth and was often dependent upon the discovery of new technologies (i.e., better microscopes or better techniques in crystallography that would provide better visual representations as evidence of the helical structure of the DNA); and (b) Models (three-dimensional) were used as a way to represent the visual images (X-ray images) and connect them to the evidence provided by other sources to see whether the theory can be supported. Therefore, the model of DNA was built based on the combination of visual evidence and experimental data.

An example showcasing the importance of visual representations in the process of knowledge production in this case is provided by Watson, in his book The Double Helix (1968):

…since the middle of the summer Rosy [Rosalind Franklin] had had evidence for a new three-dimensional form of DNA. It occurred when the DNA 2molecules were surrounded by a large amount of water. When I asked what the pattern was like, Maurice went into the adjacent room to pick up a print of the new form they called the “B” structure. The instant I saw the picture, my mouth fell open and my pulse began to race. The pattern was unbelievably simpler than those previously obtained (A form). Moreover, the black cross of reflections which dominated the picture could arise only from a helical structure. With the A form the argument for the helix was never straightforward, and considerable ambiguity existed as to exactly which type of helical symmetry was present. With the B form however, mere inspection of its X-ray picture gave several of the vital helical parameters. (p. 167-169)

As suggested by Watson’s personal account of the discovery of the DNA, the photo taken by Rosalind Franklin (Fig. 1 ) convinced him that the DNA molecule must consist of two chains arranged in a paired helix, which resembles a spiral staircase or ladder, and on March 7, 1953, Watson and Crick finished and presented their model of the structure of DNA (Watson and Berry 2004 ; Watson 1968 ) which was based on the visual information provided by the X-ray image and their knowledge of chemistry.

X-ray chrystallography of DNA

In analyzing the visualization practice in this case study, we observe the following instances that highlight how the visual information played a role:

Asking questions and defining problems: The real world in the model of science can at some points only be observed through visual representations or representations, i.e., if we are using DNA as an example, the structure of DNA was only observable through the crystallography images produced by Rosalind Franklin in the laboratory. There was no other way to observe the structure of DNA, therefore the real world.

Analyzing and interpreting data: The images that resulted from crystallography as well as their interpretations served as the data for the scientists studying the structure of DNA.

Experimenting: The data in the form of visual information were used to predict the possible structure of the DNA.

Modeling: Based on the prediction, an actual three-dimensional model was prepared by Watson and Crick. The first model did not fit with the real world (refuted by Rosalind Franklin and her research group from King’s College) and Watson and Crick had to go through the same process again to find better visual evidence (better crystallography images) and create an improved visual model.

Example excerpts from Watson’s biography provide further evidence for how visualization practices were applied in the context of the discovery of DNA (Table 1 ).

In summary, by examining the history of the discovery of DNA, we showcased how visual data is used as scientific evidence in science, identifying in that way an aspect of the nature of science that is still unexplored in the history of science and an aspect that has been ignored in the teaching of science. Visual representations are used in many ways: as images, as models, as evidence to support or rebut a model, and as interpretations of reality.

Case study 2: applying visual reasoning in knowledge production, the example of the lines of magnetic force

The focus of this case study is on Faraday’s use of the lines of magnetic force. Faraday is known of his exploratory, creative, and yet systemic way of experimenting, and the visual reasoning leading to theoretical development was an inherent part of this experimentation (Gooding 2006 ). Faraday’s articles or notebooks do not include mathematical formulations; instead, they include images and illustrations from experimental devices and setups to the recapping of his theoretical ideas (Nersessian 2008 ). According to Gooding ( 2006 ), “Faraday’s visual method was designed not to copy apparent features of the world, but to analyse and replicate them” (2006, p. 46).

The lines of force played a central role in Faraday’s research on electricity and magnetism and in the development of his “field theory” (Faraday 1852a ; Nersessian 1984 ). Before Faraday, the experiments with iron filings around magnets were known and the term “magnetic curves” was used for the iron filing patterns and also for the geometrical constructs derived from the mathematical theory of magnetism (Gooding et al. 1993 ). However, Faraday used the lines of force for explaining his experimental observations and in constructing the theory of forces in magnetism and electricity. Examples of Faraday’s different illustrations of lines of magnetic force are given in Fig. 2 . Faraday gave the following experiment-based definition for the lines of magnetic forces:

a Iron filing pattern in case of bar magnet drawn by Faraday (Faraday 1852b , Plate IX, p. 158, Fig. 1), b Faraday’s drawing of lines of magnetic force in case of cylinder magnet, where the experimental procedure, knife blade showing the direction of lines, is combined into drawing (Faraday, 1855, vol. 1, plate 1)

A line of magnetic force may be defined as that line which is described by a very small magnetic needle, when it is so moved in either direction correspondent to its length, that the needle is constantly a tangent to the line of motion; or it is that line along which, if a transverse wire be moved in either direction, there is no tendency to the formation of any current in the wire, whilst if moved in any other direction there is such a tendency; or it is that line which coincides with the direction of the magnecrystallic axis of a crystal of bismuth, which is carried in either direction along it. The direction of these lines about and amongst magnets and electric currents, is easily represented and understood, in a general manner, by the ordinary use of iron filings. (Faraday 1852a , p. 25 (3071))

The definition describes the connection between the experiments and the visual representation of the results. Initially, the lines of force were just geometric representations, but later, Faraday treated them as physical objects (Nersessian 1984 ; Pocovi and Finlay 2002 ):

I have sometimes used the term lines of force so vaguely, as to leave the reader doubtful whether I intended it as a merely representative idea of the forces, or as the description of the path along which the power was continuously exerted. … wherever the expression line of force is taken simply to represent the disposition of forces, it shall have the fullness of that meaning; but that wherever it may seem to represent the idea of the physical mode of transmission of the force, it expresses in that respect the opinion to which I incline at present. The opinion may be erroneous, and yet all that relates or refers to the disposition of the force will remain the same. (Faraday, 1852a , p. 55-56 (3075))

He also felt that the lines of force had greater explanatory power than the dominant theory of action-at-a-distance:

Now it appears to me that these lines may be employed with great advantage to represent nature, condition, direction and comparative amount of the magnetic forces; and that in many cases they have, to the physical reasoned at least, a superiority over that method which represents the forces as concentrated in centres of action… (Faraday, 1852a , p. 26 (3074))

For giving some insight to Faraday’s visual reasoning as an epistemic practice, the following examples of Faraday’s studies of the lines of magnetic force (Faraday 1852a , 1852b ) are presented:

(a) Asking questions and defining problems: The iron filing patterns formed the empirical basis for the visual model: 2D visualization of lines of magnetic force as presented in Fig. 2 . According to Faraday, these iron filing patterns were suitable for illustrating the direction and form of the magnetic lines of force (emphasis added):

It must be well understood that these forms give no indication by their appearance of the relative strength of the magnetic force at different places, inasmuch as the appearance of the lines depends greatly upon the quantity of filings and the amount of tapping; but the direction and forms of these lines are well given, and these indicate, in a considerable degree, the direction in which the forces increase and diminish . (Faraday 1852b , p.158 (3237))

Despite being static and two dimensional on paper, the lines of magnetic force were dynamical (Nersessian 1992 , 2008 ) and three dimensional for Faraday (see Fig. 2 b). For instance, Faraday described the lines of force “expanding”, “bending,” and “being cut” (Nersessian 1992 ). In Fig. 2 b, Faraday has summarized his experiment (bar magnet and knife blade) and its results (lines of force) in one picture.

(b) Analyzing and interpreting data: The model was so powerful for Faraday that he ended up thinking them as physical objects (e.g., Nersessian 1984 ), i.e., making interpretations of the way forces act. Of course, he made a lot of experiments for showing the physical existence of the lines of force, but he did not succeed in it (Nersessian 1984 ). The following quote illuminates Faraday’s use of the lines of force in different situations:

The study of these lines has, at different times, been greatly influential in leading me to various results, which I think prove their utility as well as fertility. Thus, the law of magneto-electric induction; the earth’s inductive action; the relation of magnetism and light; diamagnetic action and its law, and magnetocrystallic action, are the cases of this kind… (Faraday 1852a , p. 55 (3174))

(c) Experimenting: In Faraday's case, he used a lot of exploratory experiments; in case of lines of magnetic force, he used, e.g., iron filings, magnetic needles, or current carrying wires (see the quote above). The magnetic field is not directly observable and the representation of lines of force was a visual model, which includes the direction, form, and magnitude of field.

(d) Modeling: There is no denying that the lines of magnetic force are visual by nature. Faraday’s views of lines of force developed gradually during the years, and he applied and developed them in different contexts such as electromagnetic, electrostatic, and magnetic induction (Nersessian 1984 ). An example of Faraday’s explanation of the effect of the wire b’s position to experiment is given in Fig. 3 . In Fig. 3 , few magnetic lines of force are drawn, and in the quote below, Faraday is explaining the effect using these magnetic lines of force (emphasis added):

Picture of an experiment with different arrangements of wires ( a , b’ , b” ), magnet, and galvanometer. Note the lines of force drawn around the magnet. (Faraday 1852a , p. 34)

It will be evident by inspection of Fig. 3 , that, however the wires are carried away, the general result will, according to the assumed principles of action, be the same; for if a be the axial wire, and b’, b”, b”’ the equatorial wire, represented in three different positions, whatever magnetic lines of force pass across the latter wire in one position, will also pass it in the other, or in any other position which can be given to it. The distance of the wire at the place of intersection with the lines of force, has been shown, by the experiments (3093.), to be unimportant. (Faraday 1852a , p. 34 (3099))

In summary, by examining the history of Faraday’s use of lines of force, we showed how visual imagery and reasoning played an important part in Faraday’s construction and representation of his “field theory”. As Gooding has stated, “many of Faraday’s sketches are far more that depictions of observation, they are tools for reasoning with and about phenomena” (2006, p. 59).

Case study 3: visualizing scientific methods, the case of a journal

The focus of the third case study is the Journal of Visualized Experiments (JoVE) , a peer-reviewed publication indexed in PubMed. The journal devoted to the publication of biological, medical, chemical, and physical research in a video format. The journal describes its history as follows:

JoVE was established as a new tool in life science publication and communication, with participation of scientists from leading research institutions. JoVE takes advantage of video technology to capture and transmit the multiple facets and intricacies of life science research. Visualization greatly facilitates the understanding and efficient reproduction of both basic and complex experimental techniques, thereby addressing two of the biggest challenges faced by today's life science research community: i) low transparency and poor reproducibility of biological experiments and ii) time and labor-intensive nature of learning new experimental techniques. ( http://www.jove.com/ )

By examining the journal content, we generate a set of categories that can be considered as indicators of relevance and significance in terms of epistemic practices of science that have relevance for science education. For example, the quote above illustrates how scientists view some norms of scientific practice including the norms of “transparency” and “reproducibility” of experimental methods and results, and how the visual format of the journal facilitates the implementation of these norms. “Reproducibility” can be considered as an epistemic criterion that sits at the heart of what counts as an experimental procedure in science:

Investigating what should be reproducible and by whom leads to different types of experimental reproducibility, which can be observed to play different roles in experimental practice. A successful application of the strategy of reproducing an experiment is an achievement that may depend on certain isiosyncratic aspects of a local situation. Yet a purely local experiment that cannot be carried out by other experimenters and in other experimental contexts will, in the end be unproductive in science. (Sarkar and Pfeifer 2006 , p.270)

We now turn to an article on “Elevated Plus Maze for Mice” that is available for free on the journal website ( http://www.jove.com/video/1088/elevated-plus-maze-for-mice ). The purpose of this experiment was to investigate anxiety levels in mice through behavioral analysis. The journal article consists of a 9-min video accompanied by text. The video illustrates the handling of the mice in soundproof location with less light, worksheets with characteristics of mice, computer software, apparatus, resources, setting up the computer software, and the video recording of mouse behavior on the computer. The authors describe the apparatus that is used in the experiment and state how procedural differences exist between research groups that lead to difficulties in the interpretation of results:

The apparatus consists of open arms and closed arms, crossed in the middle perpendicularly to each other, and a center area. Mice are given access to all of the arms and are allowed to move freely between them. The number of entries into the open arms and the time spent in the open arms are used as indices of open space-induced anxiety in mice. Unfortunately, the procedural differences that exist between laboratories make it difficult to duplicate and compare results among laboratories.

The authors’ emphasis on the particularity of procedural context echoes in the observations of some philosophers of science:

It is not just the knowledge of experimental objects and phenomena but also their actual existence and occurrence that prove to be dependent on specific, productive interventions by the experimenters” (Sarkar and Pfeifer 2006 , pp. 270-271)

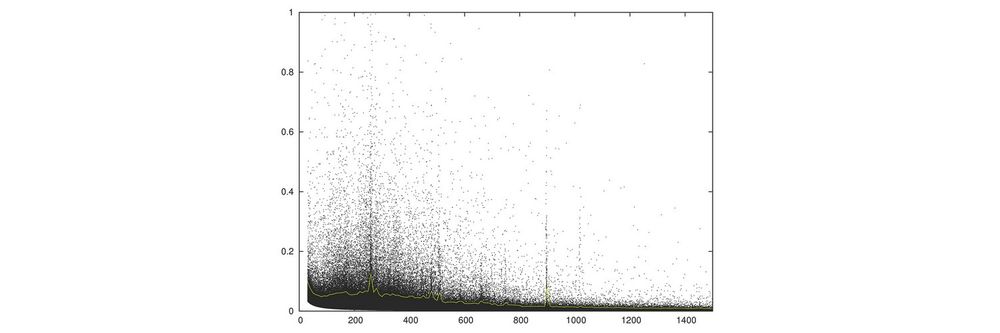

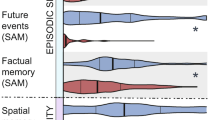

The inclusion of a video of the experimental procedure specifies what the apparatus looks like (Fig. 4 ) and how the behavior of the mice is captured through video recording that feeds into a computer (Fig. 5 ). Subsequently, a computer software which captures different variables such as the distance traveled, the number of entries, and the time spent on each arm of the apparatus. Here, there is visual information at different levels of representation ranging from reconfiguration of raw video data to representations that analyze the data around the variables in question (Fig. 6 ). The practice of levels of visual representations is not particular to the biological sciences. For instance, they are commonplace in nanotechnological practices:

Visual illustration of apparatus

Video processing of experimental set-up

Computer software for video input and variable recording

In the visualization processes, instruments are needed that can register the nanoscale and provide raw data, which needs to be transformed into images. Some Imaging Techniques have software incorporated already where this transformation automatically takes place, providing raw images. Raw data must be translated through the use of Graphic Software and software is also used for the further manipulation of images to highlight what is of interest to capture the (inferred) phenomena -- and to capture the reader. There are two levels of choice: Scientists have to choose which imaging technique and embedded software to use for the job at hand, and they will then have to follow the structure of the software. Within such software, there are explicit choices for the scientists, e.g. about colour coding, and ways of sharpening images. (Ruivenkamp and Rip 2010 , pp.14–15)

On the text that accompanies the video, the authors highlight the role of visualization in their experiment:

Visualization of the protocol will promote better understanding of the details of the entire experimental procedure, allowing for standardization of the protocols used in different laboratories and comparisons of the behavioral phenotypes of various strains of mutant mice assessed using this test.

The software that takes the video data and transforms it into various representations allows the researchers to collect data on mouse behavior more reliably. For instance, the distance traveled across the arms of the apparatus or the time spent on each arm would have been difficult to observe and record precisely. A further aspect to note is how the visualization of the experiment facilitates control of bias. The authors illustrate how the olfactory bias between experimental procedures carried on mice in sequence is avoided by cleaning the equipment.

Our discussion highlights the role of visualization in science, particularly with respect to presenting visualization as part of the scientific practices. We have used case studies from the history of science highlighting a scientist’s account of how visualization played a role in the discovery of DNA and the magnetic field and from a contemporary illustration of a science journal’s practices in incorporating visualization as a way to communicate new findings and methodologies. Our implicit aim in drawing from these case studies was the need to align science education with scientific practices, particularly in terms of how visual representations, stable or dynamic, can engage students in the processes of science and not only to be used as tools for cognitive development in science. Our approach was guided by the notion of “knowledge-as-practice” as advanced by Knorr Cetina ( 1999 ) who studied scientists and characterized their knowledge as practice, a characterization which shifts focus away from ideas inside scientists’ minds to practices that are cultural and deeply contextualized within fields of science. She suggests that people working together can be examined as epistemic cultures whose collective knowledge exists as practice.

It is important to stress, however, that visual representations are not used in isolation, but are supported by other types of evidence as well, or other theories (i.e., in order to understand the helical form of DNA, or the structure, chemistry knowledge was needed). More importantly, this finding can also have implications when teaching science as argument (e.g., Erduran and Jimenez-Aleixandre 2008 ), since the verbal evidence used in the science classroom to maintain an argument could be supported by visual evidence (either a model, representation, image, graph, etc.). For example, in a group of students discussing the outcomes of an introduced species in an ecosystem, pictures of the species and the ecosystem over time, and videos showing the changes in the ecosystem, and the special characteristics of the different species could serve as visual evidence to help the students support their arguments (Evagorou et al. 2012 ). Therefore, an important implication for the teaching of science is the use of visual representations as evidence in the science curriculum as part of knowledge production. Even though studies in the area of science education have focused on the use of models and modeling as a way to support students in the learning of science (Dori et al. 2003 ; Lehrer and Schauble 2012 ; Mendonça and Justi 2013 ; Papaevripidou et al. 2007 ) or on the use of images (i.e., Korfiatis et al. 2003 ), with the term using visuals as evidence, we refer to the collection of all forms of visuals and the processes involved.

Another aspect that was identified through the case studies is that of the visual reasoning (an integral part of Faraday’s investigations). Both the verbalization and visualization were part of the process of generating new knowledge (Gooding 2006 ). Even today, most of the textbooks use the lines of force (or just field lines) as a geometrical representation of field, and the number of field lines is connected to the quantity of flux. Often, the textbooks use the same kind of visual imagery than in what is used by scientists. However, when using images, only certain aspects or features of the phenomena or data are captured or highlighted, and often in tacit ways. Especially in textbooks, the process of producing the image is not presented and instead only the product—image—is left. This could easily lead to an idea of images (i.e., photos, graphs, visual model) being just representations of knowledge and, in the worse case, misinterpreted representations of knowledge as the results of Pocovi and Finlay ( 2002 ) in case of electric field lines show. In order to avoid this, the teachers should be able to explain how the images are produced (what features of phenomena or data the images captures, on what ground the features are chosen to that image, and what features are omitted); in this way, the role of visualization in knowledge production can be made “visible” to students by engaging them in the process of visualization.

The implication of these norms for science teaching and learning is numerous. The classroom contexts can model the generation, sharing and evaluation of evidence, and experimental procedures carried out by students, thereby promoting not only some contemporary cultural norms in scientific practice but also enabling the learning of criteria, standards, and heuristics that scientists use in making decisions on scientific methods. As we have demonstrated with the three case studies, visual representations are part of the process of knowledge growth and communication in science, as demonstrated with two examples from the history of science and an example from current scientific practices. Additionally, visual information, especially with the use of technology is a part of students’ everyday lives. Therefore, we suggest making use of students’ knowledge and technological skills (i.e., how to produce their own videos showing their experimental method or how to identify or provide appropriate visual evidence for a given topic), in order to teach them the aspects of the nature of science that are often neglected both in the history of science and the design of curriculum. Specifically, what we suggest in this paper is that students should actively engage in visualization processes in order to appreciate the diverse nature of doing science and engage in authentic scientific practices.

However, as a word of caution, we need to distinguish the products and processes involved in visualization practices in science:

If one considers scientific representations and the ways in which they can foster or thwart our understanding, it is clear that a mere object approach, which would devote all attention to the representation as a free-standing product of scientific labor, is inadequate. What is needed is a process approach: each visual representation should be linked with its context of production (Pauwels 2006 , p.21).

The aforementioned suggests that the emphasis in visualization should shift from cognitive understanding—using the products of science to understand the content—to engaging in the processes of visualization. Therefore, an implication for the teaching of science includes designing curriculum materials and learning environments that create a social and epistemic context and invite students to engage in the practice of visualization as evidence, reasoning, experimental procedure, or a means of communication (as presented in the three case studies) and reflect on these practices (Ryu et al. 2015 ).

Finally, a question that arises from including visualization in science education, as well as from including scientific practices in science education is whether teachers themselves are prepared to include them as part of their teaching (Bybee 2014 ). Teacher preparation programs and teacher education have been critiqued, studied, and rethought since the time they emerged (Cochran-Smith 2004 ). Despite the years of history in teacher training and teacher education, the debate about initial teacher training and its content still pertains in our community and in policy circles (Cochran-Smith 2004 ; Conway et al. 2009 ). In the last decades, the debate has shifted from a behavioral view of learning and teaching to a learning problem—focusing on that way not only on teachers’ knowledge, skills, and beliefs but also on making the connection of the aforementioned with how and if pupils learn (Cochran-Smith 2004 ). The Science Education in Europe report recommended that “Good quality teachers, with up-to-date knowledge and skills, are the foundation of any system of formal science education” (Osborne and Dillon 2008 , p.9).

However, questions such as what should be the emphasis on pre-service and in-service science teacher training, especially with the new emphasis on scientific practices, still remain unanswered. As Bybee ( 2014 ) argues, starting from the new emphasis on scientific practices in the NGSS, we should consider teacher preparation programs “that would provide undergraduates opportunities to learn the science content and practices in contexts that would be aligned with their future work as teachers” (p.218). Therefore, engaging pre- and in-service teachers in visualization as a scientific practice should be one of the purposes of teacher preparation programs.

Achieve. (2013). The next generation science standards (pp. 1–3). Retrieved from http://www.nextgenscience.org/ .

Google Scholar

Barber, J, Pearson, D, & Cervetti, G. (2006). Seeds of science/roots of reading . California: The Regents of the University of California.

Bungum, B. (2008). Images of physics: an explorative study of the changing character of visual images in Norwegian physics textbooks. NorDiNa, 4 (2), 132–141.

Bybee, RW. (2014). NGSS and the next generation of science teachers. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 25 (2), 211–221. doi: 10.1007/s10972-014-9381-4 .

Article Google Scholar

Chambers, D. (1983). Stereotypic images of the scientist: the draw-a-scientist test. Science Education, 67 (2), 255–265.

Cochran-Smith, M. (2004). The problem of teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 55 (4), 295–299. doi: 10.1177/0022487104268057 .

Conway, PF, Murphy, R, & Rath, A. (2009). Learning to teach and its implications for the continuum of teacher education: a nine-country cross-national study .

Crick, F. (1988). What a mad pursuit . USA: Basic Books.

Dimopoulos, K, Koulaidis, V, & Sklaveniti, S. (2003). Towards an analysis of visual images in school science textbooks and press articles about science and technology. Research in Science Education, 33 , 189–216.

Dori, YJ, Tal, RT, & Tsaushu, M. (2003). Teaching biotechnology through case studies—can we improve higher order thinking skills of nonscience majors? Science Education, 87 (6), 767–793. doi: 10.1002/sce.10081 .

Duschl, RA, & Bybee, RW. (2014). Planning and carrying out investigations: an entry to learning and to teacher professional development around NGSS science and engineering practices. International Journal of STEM Education, 1 (1), 12. doi: 10.1186/s40594-014-0012-6 .

Duschl, R., Schweingruber, H. A., & Shouse, A. (2008). Taking science to school . Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Erduran, S, & Jimenez-Aleixandre, MP (Eds.). (2008). Argumentation in science education: perspectives from classroom-based research . Dordrecht: Springer.

Eurydice. (2012). Developing key competencies at school in Europe: challenges and opportunities for policy – 2011/12 (pp. 1–72).

Evagorou, M, Jimenez-Aleixandre, MP, & Osborne, J. (2012). “Should we kill the grey squirrels?” A study exploring students’ justifications and decision-making. International Journal of Science Education, 34 (3), 401–428. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2011.619211 .

Faraday, M. (1852a). Experimental researches in electricity. – Twenty-eighth series. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 142 , 25–56.

Faraday, M. (1852b). Experimental researches in electricity. – Twenty-ninth series. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 142 , 137–159.

Gilbert, JK. (2010). The role of visual representations in the learning and teaching of science: an introduction (pp. 1–19).

Gilbert, J., Reiner, M. & Nakhleh, M. (2008). Visualization: theory and practice in science education . Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Gooding, D. (2006). From phenomenology to field theory: Faraday’s visual reasoning. Perspectives on Science, 14 (1), 40–65.

Gooding, D, Pinch, T, & Schaffer, S (Eds.). (1993). The uses of experiment: studies in the natural sciences . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.