Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Elements of Argument

9 Toulmin Argument Model

By liza long, amy minervini, and joel gladd.

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Toulmin devoted his works to analyzing moral reasoning. He sought to develop practical ways to evaluate ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components, was considered Toulmin’s most influential work, particularly in the fields of rhetoric, communication, and computer science. His components continue to provide useful means for analyzing arguments.

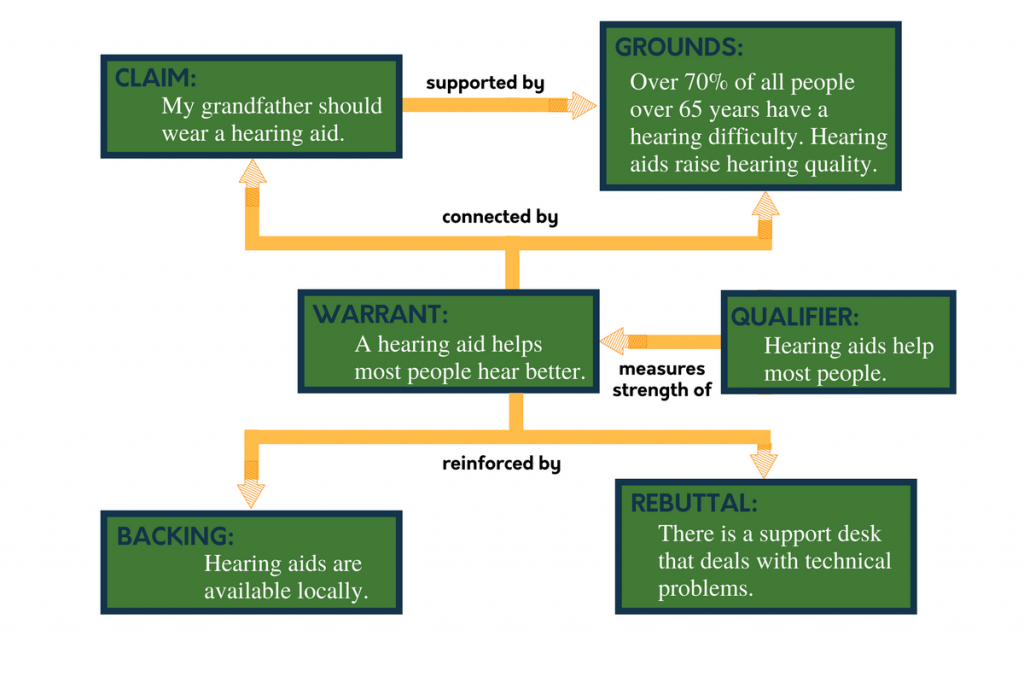

The following are the parts of a Toulmin argument (see Figure 9.1 for an example):

Claim: The claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept as true (i.e., a conclusion) and forms the nexus of the Toulmin argument because all the other parts relate back to the claim. The claim can include information and ideas you are asking readers to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. One example of a claim is the following:

My grandfather should wear a hearing aid.

This claim both asks the reader to believe an idea and suggests an action to enact. However, like all claims, it can be challenged. Thus, a Toulmin argument does not end with a claim but also includes grounds and warrant to give support and reasoning to the claim.

Grounds: The grounds form the basis of real persuasion and include the reasoning behind the claim, data, and proof of expertise. Think of grounds as a combination of premises and support. The truth of the claim rests upon the grounds, so those grounds should be tested for strength, credibility, relevance, and reliability. The following are examples of grounds:

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty. Hearing aids raise hearing quality.

Information is usually a powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational will more likely be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. Thus, grounds can also include appeals to emotion, provided they aren’t misused. The best arguments, however, use a variety of support and rhetorical appeals.

Warrant: A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant. The warrant may be carefully explained and explicit or unspoken and implicit. The warrant answers the question, “Why does that data mean your claim is true?” For example,

A hearing aid helps most people hear better.

The warrant may be simple, and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos, ethos or pathos, or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and, hence, unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

Backing: The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant. Backing can be confused with grounds, but the main difference is this: grounds should directly support the premises of the main argument itself, while backing exists to help the warrants make more sense. For example,

Hearing aids are available locally.

This statement works as backing because it gives credence to the warrant stated above, that a hearing aid will help most people hear better. The fact that hearing aids are readily available makes the warrant even more reasonable.

Qualifier: The qualifier indicates how the data justifies the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. The necessity of qualifying words comes from the plain fact that most absolute claims are ultimately false (all women want to be mothers, e.g.) because one counterexample sinks them immediately. Thus, most arguments need some sort of qualifier, words that temper an absolute claim and make it more reasonable. Common qualifiers include “most,” “usually,” “always,” or “sometimes.” For example,

Hearing aids help most people.

The qualifier “most” here allows for the reasonable understanding that rarely does one thing (a hearing aid) universally benefit all people. Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect:

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations can be used to bolster weak arguments, so it is important to recognize them. They are often used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus, they slip “usually,” “virtually,” “unless,” and so on into their claims to protect against liability. While this may seem like sneaky practice, and it can be for some advertisers, it is important to note that the use of qualifiers and reservations can be a useful and legitimate part of an argument.

Rebuttal: Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. For example, if you anticipated a counterargument that hearing aids, as a technology, may be fraught with technical difficulties, you would include a rebuttal to deal with that counterargument:

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and the other parts of the Toulmin structure.

Even if you do not wish to write an essay using strict Toulmin structure, using the Toulmin checklist can make an argument stronger. When first proposed, Toulmin based his layout on legal arguments, intending it to be used analyzing arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to other fields until later. The first three elements–“claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant”–are considered the essential components of practical arguments, while the last three—“qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”—may not be necessary for all arguments.

Toulmin Exercise

Find an argument in essay form and diagram it using the Toulmin model. The argument can come from an Op-Ed article in a newspaper or a magazine think piece or a scholarly journal. See if you can find all six elements of the Toulmin argument. Use the structure above to diagram your article’s argument.

Attributions

“Toulmin Argument Model” by Liza Long, Amy Minervini, and Joel Gladd is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Writing Arguments in STEM Copyright © by Jason Peters; Jennifer Bates; Erin Martin-Elston; Sadie Johann; Rebekah Maples; Anne Regan; and Morgan White is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, toulmin argument.

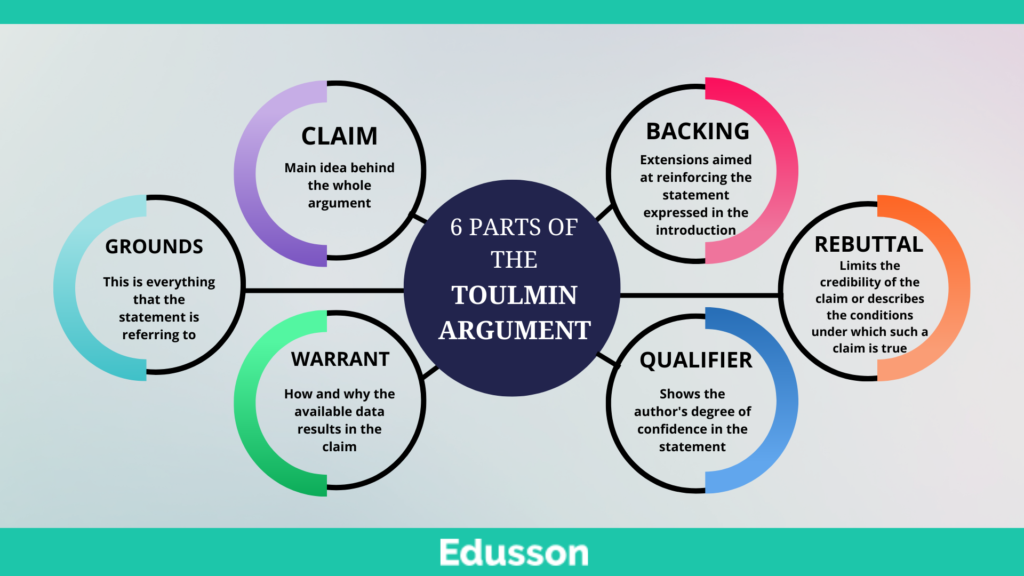

Stephen Toulmin's model of argumentation theorizes six rhetorical moves constitute argumentation: Evidence , Warrant , Claim , Qualifier , Rebuttal, and Backing . Learn to develop clear, persuasive arguments and to critique the arguments of others. By learning this model, you'll gain the skills to construct clearer, more persuasive arguments and critically assess the arguments presented by others, enhancing your writing and analytical abilities in academic and professional settings.

Stephen Toulmin’s (1958) model of argument conceptualizes argument as a series of six rhetorical moves :

- Data, Evidence

- Counterargument, Counterclaim

- Reservation/Rebuttal

Related Concepts

Evidence ; Persuasion; Rhetorical Analysis ; Rhetorical Reasoning

Why Does Toulmin Argument Matter?

Toulmin’s model of argumentation is particularly valuable for college students because it provides a structured framework for analyzing and constructing arguments, skills that are essential across various academic disciplines and real-world situations.

By understanding Toulmin’s components—claim, evidence, warrant, backing, qualifier, and rebuttal—students can develop more coherent, persuasive arguments and critically evaluate the arguments of others. This model encourages students to think deeply about the logic and effectiveness of their argumentation, emphasizing the importance of supporting claims with solid evidence and reasoning. Additionally, familiarity with Toulmin’s model prepares students for scenarios involving critical analysis and debate, whether in writing essays, participating in discussions, or presenting research.

By mastering this model, students enhance their ability to communicate effectively, a crucial skill for academic success and professional advancement.

When should writers or speakers consider Toulmin’s model of argument?

Toulmin’s model of argument works especially well in situations where disputes are being reviewed by a third party — such as judge, an arbitrator, or evaluation committee.

Declarative knowledge of Toulmin Argument helps with

- inventing or developing your own arguments (even if you’re developing a Rogerian or Aristotelian argument )

- critiquing your arguments or the arguments of others.

Summary of Stephen Toulmin’s Model of Argument

The three essential components of argument.

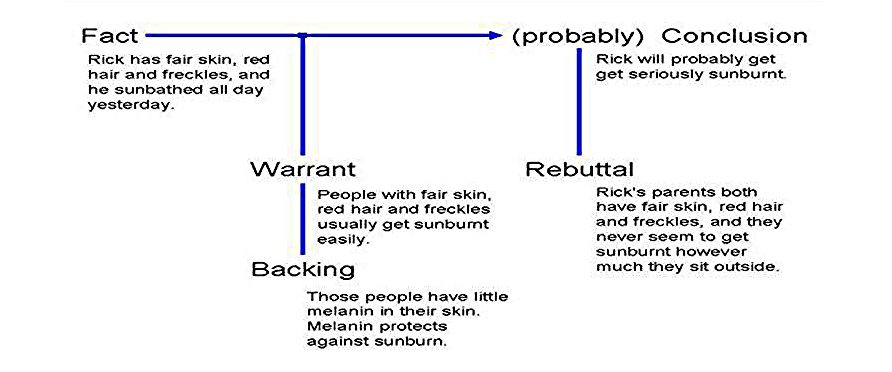

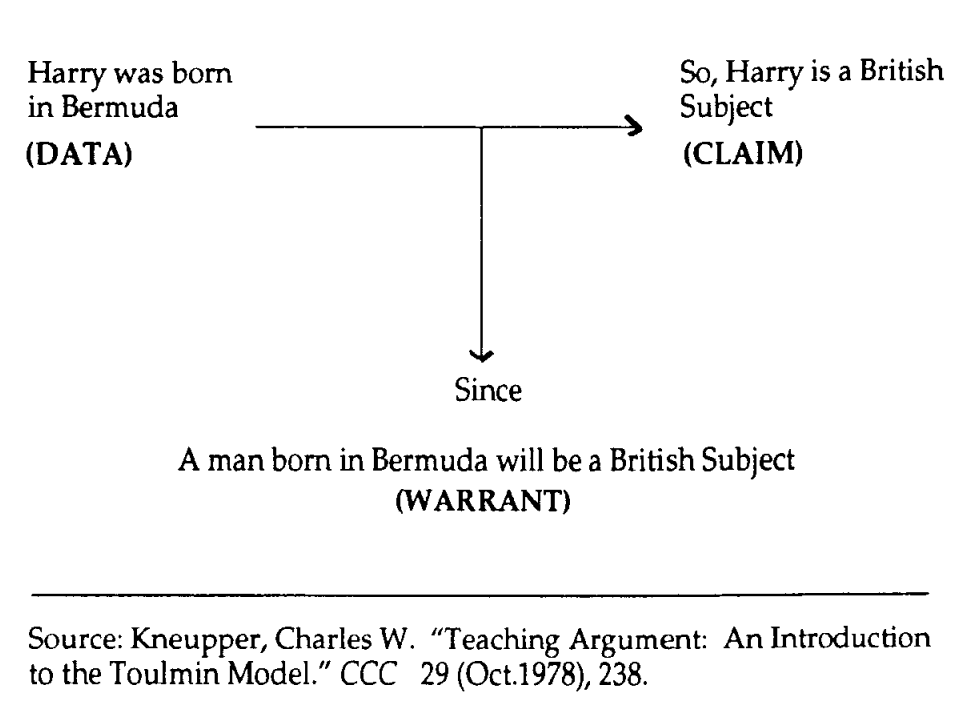

Stephen Toulmin’s model of argument posits the three essential elements of an argument are

- Data (aka a Fact or Evidence)

- Warrant (which the writer, speaker, knowledge worker . . . may imply rather than explicitly state).

Toulmin’s model presumes data, matters of fact and opinion, must be supplied as evidence to support a claim. The claim focuses the discourse by explicitly stating the desired conclusion of the argument.

In turn, a warrant, the third essential component of an argument, provides the reasoning that links the data to the claim.

The example in Figure 1 demonstrates the abstract, hypothetical linking between a claim and data that a warrant provides. Prior to this link–that. people born in Bermuda are British–the claim that Harry is a British subject because he was born in Bermuda is unsubstantiated.

The 6 Elements of Successful Argument

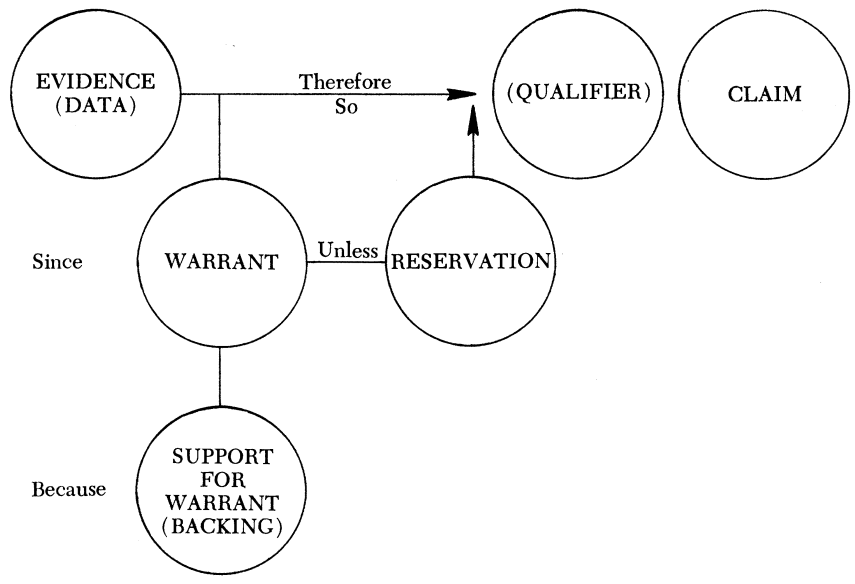

While the argument presented in Figure 1 is a simple one, life is not always simple.

In situations where people are likely to dispute the application of a warrant to data, you may need to develop backing for your warrants. o account for the conflicting desires and assumptions of an audience, Toulmin identifies a second triad of components that may not be used:

- Reservation

- Qualification.

Charles Kneupper provides us with the following diagram of these six elements (238):

*This article is adapted from Moxley, Joseph M. “ Reinventing the Wheel or Teaching the Basics ?: College Writers ‘ Knowledge of Argumentation .” Composition. Studies 21.2 (1993): 3-15.

Kneupper, C. W. (1978). Teaching Argument: An Introduction to the Toulmin Model. College Composition and Communication , 29 (3), 237–241. https://doi.org/10.2307/356935

Moxley, Joseph M. “ Reinventing the Wheel or Teaching the Basics ?: College Writers ‘ Knowledge of Argumentation .” Composition. Studies 21.2 (1993): 3-15.

Toulmin, S. (1969). The Uses of Argument , Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Toulmin Argument Model

In simplified terms this is the argument of “I am right — and here is why.” In this model of argument, the arguer creates a claim, also referred to as a thesis, that states the idea you are asking the audience to accept as true and then supports it with evidence and reasoning. The Toulmin argument goes further, though, than that basic model with a claim and support. It adds some additional parts such as rebuttals, warrants, backing, and qualifiers to create a water-tight argument.

Preview the Toulmin Argument Model

Stephen Toulmin and His Six-Part Argument Model

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Toulmin devoted his works to analyzing moral reasoning. He sought to develop practical ways to evaluate ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components, was considered Toulmin’s most influential work, particularly in the fields of rhetoric, communication, and computer science. His components continue to provide useful means for analyzing arguments.

Figure 8.1 “Toulmin Argument”

The following are the parts of a Toulmin argument:

1. Claim : The claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept as true (i.e., a conclusion) and forms the nexus of the Toulmin argument because all the other parts relate back to the claim. The claim can include information and ideas you are asking readers to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. One example of a claim:

My grandfather should wear a hearing aid.

This claim both asks the reader to believe an idea and suggests an action to enact. However, like all claims, it can be challenged. Thus, a Toulmin argument does not end with a claim but also includes grounds and warrant to give support and reasoning to the claim.

2. Grounds : The grounds form the basis of real persuasion and includes the reasoning behind the claim, data, and proof of expertise. Think of grounds as a combination of premises and support . The truth of the claim rests upon the grounds, so those grounds should be tested for strength, credibility, relevance, and reliability. The following are examples of grounds:

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty.

Hearing aids raise hearing quality.

Information is usually a powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational will more likely be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. Thus, grounds can also include appeals to emotion, provided they aren’t misused. The best arguments, however, use a variety of support and rhetorical appeals.

3. Warrant : A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant . The warrant may be carefully explained and explicit or unspoken and implicit. The warrant answers the question, “Why does that data mean your claim is true?” For example,

A hearing aid helps most people hear better.

The warrant may be simple, and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos , ethos or pathos , or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and, hence, unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

4. Backing : The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant. Backing can be confused with grounds, but the main difference is this: Grounds should directly support the premises of the main argument itself, while backing exists to help the warrants make more sense. For example,

Hearing aids are available locally.

This statement works as backing because it gives credence to the warrant stated above, that a hearing aid will help most people hear better. The fact that hearing aids are readily available makes the warrant even more reasonable.

5. Qualifier : The qualifier indicates how the data justifies the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. The necessity of qualifying words comes from the plain fact that most absolute claims are ultimately false (all women want to be mothers, e.g.) because one counterexample sinks them immediately. Thus, most arguments need some sort of qualifier, words that temper an absolute claim and make it more reasonable. Common qualifiers include “most,” “usually,” “always,” or “sometimes.” For example,

Hearing aids help most people.

The qualifier “most” here allows for the reasonable understanding that rarely does one thing (a hearing aid) universally benefit all people. Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect:

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations can be used to bolster weak arguments, so it is important to recognize them. They are often used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus, they slip “usually,” “virtually,” “unless,” and so on into their claims to protect against liability. While this may seem like sneaky practice, and it can be for some advertisers, it is important to note that the use of qualifiers and reservations can be a useful and legitimate part of an argument.

6. Rebuttal : Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. For example, if you anticipated a counterargument that hearing aids, as a technology, may be fraught with technical difficulties, you would include a rebuttal to deal with that counterargument:

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and the other parts of the Toulmin structure.

When to Use the Toulmin Argument Model

Overall, the Toulmin Argument Model may be used to create a strong, persuasive argument — and it can be used to analyze and examine an argument. You may use this approach for a speech, academic paper, or online argument that you are creating. This approach can help you to create a sound, persuasive argument. You also may use this model to analyze an argument that you read, watch, or hear. The model can help you to identify missing parts in an argument. Sometimes, an argument “feels” wrong, but this approach can help you to identify why it is flawed.

Even if you do not wish to write an essay using strict Toulmin structure, using the Toulmin checklist can make an argument stronger. When first proposed, Toulmin based his layout on legal arguments, intending it to be used analyzing arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to other fields until later. The first three elements–“claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant”–are considered the essential components of practical arguments, while the last three—“qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”—may not be necessary for all arguments.

Find an argument in essay form and diagram it using the Toulmin model. The argument can come from an Op-Ed article in a newspaper or a magazine think piece or a scholarly journal. See if you can find all six elements of the Toulmin argument. Use the structure above to diagram your article’s argument.

Key Takeaways

- Toulmin’s Argument Model —six interrelated components used to diagram an argument.

- A Toulmin Argument may be used in academic writing or to persuade someone online.

- A Toulmin Argument model can be used to analyze an argument you read

- A Toulmin Argument model also can be used to create an argument when you are writing.

Chapter Attribution

The material in this chapter is a derivative (including a short section written by Liona Burnham) of the following sources:

“The Toulmin Argument Model” in Let’s Get Writing! by Kirsten DeVries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

“Toulmin Argument” in Writing and Rhetoric by Heather Hopkins Bowers; Anthony Ruggiero; and Jason Saphara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Image Attributions

Figure 7.1: “Toulmin Argument,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0

Upping Your Argument and Research Game Copyright © 2022 by Liona Burnham is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

62 Toulmin Argument Model

Toulmin argument model.

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Toulmin devoted his works to analyzing moral reasoning. He sought to develop practical ways to evaluate ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components, was considered Toulmin’s most influential work, particularly in the fields of rhetoric, communication, and computer science. His components continue to provide useful means for analyzing arguments, and the terms involved can be added to those defined in earlier sections of this chapter.

The following are the parts of a Toulmin argument:

1. Claim : The claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept as true (i.e., a conclusion) and forms the nexus of the Toulmin argument because all the other parts relate back to the claim. The claim can include information and ideas you are asking readers to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. One example of a claim:

My grandfather should wear a hearing aid.

This claim both asks the reader to believe an idea and suggests an action to enact. However, like all claims, it can be challenged. Thus, a Toulmin argument does not end with a claim but also includes grounds and warrant to give support and reasoning to the claim.

2. Grounds : The grounds form the basis of real persuasion and includes the reasoning behind the claim, data, and proof of expertise. Think of grounds as a combination of premises and support . The truth of the claim rests upon the grounds, so those grounds should be tested for strength, credibility, relevance, and reliability. The following are examples of grounds:

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty.

Hearing aids raise hearing quality.

Information is usually a powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational will more likely be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. Thus, grounds can also include appeals to emotion, provided they aren’t misused. The best arguments, however, use a variety of support and rhetorical appeals.

3. Warrant : A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant . The warrant may be carefully explained and explicit or unspoken and implicit. The warrant answers the question, “Why does that data mean your claim is true?” For example,

A hearing aid helps most people hear better.

The warrant may be simple, and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos , ethos or pathos , or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and, hence, unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

4. Backing : The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant. Backing can be confused with grounds, but the main difference is this: Grounds should directly support the premises of the main argument itself, while backing exists to help the warrants make more sense. For example,

Hearing aids are available locally.

This statement works as backing because it gives credence to the warrant stated above, that a hearing aid will help most people hear better. The fact that hearing aids are readily available makes the warrant even more reasonable.

5. Qualifier : The qualifier indicates how the data justifies the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. The necessity of qualifying words comes from the plain fact that most absolute claims are ultimately false (all women want to be mothers, e.g.) because one counterexample sinks them immediately. Thus, most arguments need some sort of qualifier, words that temper an absolute claim and make it more reasonable. Common qualifiers include “most,” “usually,” “always,” or “sometimes.” For example,

Hearing aids help most people.

The qualifier “most” here allows for the reasonable understanding that rarely does one thing (a hearing aid) universally benefit all people. Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect:

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations can be used to bolster weak arguments, so it is important to recognize them. They are often used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus, they slip “usually,” “virtually,” “unless,” and so on into their claims to protect against liability. While this may seem like sneaky practice, and it can be for some advertisers, it is important to note that the use of qualifiers and reservations can be a useful and legitimate part of an argument.

6. Rebuttal : Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. For example, if you anticipated a counterargument that hearing aids, as a technology, may be fraught with technical difficulties, you would include a rebuttal to deal with that counterargument:

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and the other parts of the Toulmin structure.

Even if you do not wish to write an essay using strict Toulmin structure, using the Toulmin checklist can make an argument stronger. When first proposed, Toulmin based his layout on legal arguments, intending it to be used analyzing arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to other fields until later. The first three elements–“claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant”–are considered the essential components of practical arguments, while the last three—“qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”—may not be necessary for all arguments.

Toulmin Exercise

Find an argument in essay form and diagram it using the Toulmin model. The argument can come from an Op-Ed article in a newspaper or a magazine think piece or a scholarly journal. See if you can find all six elements of the Toulmin argument. Use the structure above to diagram your article’s argument.

Write What Matters Copyright © 2020 by Liza Long; Amy Minervini; and Joel Gladd is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Toulmin Method: Guide to Writing a Successful Essay

How to write an essay in the toulmin method.

Argumentative essays are a genre of writing that challenges the student to research a topic, gather, generate and evaluate evidence, and summarize a position on the issue. It helps to get as much benefit out of the study as possible. The Toulmin model essay could be part of the shaping and self-understanding of the individual, and one day it will provide evidence to rely on in becoming a professional.

What is the Toulmin Method?

The essay form has become widespread in contemporary higher education, so many students are faced with this question – how to write an essay using the Toulmin model? The idea of an essay comes to us from the Anglo-Saxon educational tradition, where it is one of the basic elements of learning, especially in the early years. Starting an essay, especially an argument one, is a creative and demanding task. Not all students have time for such a job, given their academic schedule. If you want professional assistance, you can hire a writer to write an argumentative essay to make sure of the quality.

Toulmin’s approach, based on logic and in-depth analysis, is best suited to solving complex questions. The British philosopher and professor engaged in practical argumentation believed that it is a process of proposing hypotheses involving the discovery of new ideas and verifying existing information. In The Uses of Argument (1958), Stephen Toulmin proposed a set containing six interrelated components for analyzing arguments, and these are what we will talk about today. Toulmin considered that a good argument could be successful in credibility and resistance to additional criticism. We shall therefore take a look at how it is done.

How do you compose an essay based on Toulmin model? Formulate the statement that you intend to defend. Provide evidence to support it. Then use the factors we talk about below. As an alternative, you can use information from a custom essay writing service that guarantees a good grade. Not everyone is really gifted at writing well-organized texts.

The Six Parts of The Toulmin Argument

The structure of Toulmin argumentative essay is slightly more complex than in other types of papers.

Think of this section as the main idea behind the whole argument. The claim can be divided into five following categories:

- definitions,

- strategies.

This is the part dealing with the answer to the question, “What is the author trying to prove?”.

The arguments are referred to as the basis for the claim. This is everything that the statement is referring to. It can be statistics, facts, evidence, expert opinions, or public attitudes. At this point, the following issue arises: “What is the author trying to demonstrate his point with?”. This is the body where the connection between the data and the argument is established.

Warrants are assumptions that show how and why the available data results in the claim. It gives credibility to the latter. In addition, it is often common knowledge for both the author and the audience, so in most cases, it is not expressed literally but only implied. The guiding question for determining the warrant of an argument has to be asked, “Why does the author draw this conclusion from the data?”.

Warrant Based Generalization

In the simplest Toulmin essays, the generalization essentially summarizes the common knowledge that applies to each specific case. Due to its simplicity, this technique is also used in public speaking as well as in Toulmin model essay.

Warrant Based on Analogy

An argument by analogy is an argument that is made by extrapolating information from one case to another. This is because they share many characteristics. Therefore, an argument by analogy is also very common.

Warrant Based on Sign

It is a matter of one thing deriving from something else. So one thing indicates the existence of another.

Warrant Based on Causality

The relationship between phenomena in which one major thing called the cause, given certain circumstances, brings about another thing called the effect.

Warrant Based on Authority

It is a reference to the views of persons who are recognized or influential in a particular technology or area of activity in society.

Warrant Based on Principle

Values and attitudes are the brightest and most important factors brought in argumentation. They can equally facilitate the achievement of mutual understanding, make it more difficult, and initially block the development of dialogue.

These are extensions aimed at reinforcing the statement expressed in the introduction. Such support should be used when the grounds themselves are not sufficiently persuasive to the readers and listeners.

It limits the credibility of the claim or describes the conditions under which such a claim is true. If the argument does not assume the existence of another opinion, it will be regarded as feeble. If you struggle to conceive of a contrary view, then writing the rebuttal may seem difficult. We advise you to read through the examples.

These can be words or phrases showing the author’s degree of confidence in the statement, namely: likely, possible, impossible, and unconditional.

The first three elements are considered essential to practical argumentation, while the last three are not always indispensable. An argument described in this way in a counter argument essay reveals its strength and limitations. This is the way it should be. There should be no argument that seems stronger than it is or applies more broadly than it is intended to. The point is not to outplay or defeat every counter-argument, but to get as close to the truth or a suitable solution as we are capable of. Once you have familiarized yourself with the process, you may find it complicated; however, don’t get frustrated and use an additional argumentative essay writing service to create a proper sample.

Sample of a Toulmin Argument Model

The following example of body paragraphs is for you to consider:

People should probably have firearms.

- Claim: People should probably have firearms.

- Grounds: People want to be protected.

- Warrant: Self-defense with a firearm is much more effective.

- Backing: Research shows that firearms owners are less likely to be robbed.

- Rebuttal: Not everyone should have access to firearms. Children and people with intellectual disabilities, for example, should not own firearms.

- Qualifier: The percentage of the population with intellectual health illnesses is much lower than that of the average human. The phrase ” probably” in the claim’s wording is a qualifier.

Essay Which Shows Toulmin Method

So why don’t we put all six points into practice and write a good argumentative essay to enhance understanding?

There is an age-old question of the 21st century. However, are current games more harmful or beneficial? To answer it as objectively as possible, one must rely on biology and psychology. Researchers at the University of Central Florida have proven that taking a short break from work to play a video game is far more effective in relieving stress than inactivity with total gadget avoidance and even meditation. Video games can be educational and informative. A popular stereotype is that games are bad for you. They overload the brain or are just a waste of time. Nonsense, there are plenty of benefits to be gained from gameplay if you know the limits.

Play is a way of making the brain stimulated. Games contribute to the socialization of people. Multiplayer games teach social interaction, trust, dialogue, group work, leadership, and management skills. It turns out that those who spend a lot of leisure on a PC or console solve difficult tasks easier. Attention to detail and the speed of brain and eye reactions, accelerated interaction between them, muscle response – all these things are trained to the highest degree. To do this kind of training in real life without threatening your health, you have to try very hard.

Researchers at the Open University of Catalonia have found that video games can positively affect memory, solve difficult issues, build algorithms, and improve attention span and other cognitive abilities of the brain. They stated that video game enthusiasts have an increase in the right side of the hippocampus, which is responsible for memory, over time. Studies have also shown their effectiveness in second language acquisition, learning math, and science. This is potentially good news for pupils, students, and the millions of people who love to play.

In addition, video games have changed significantly in recent years; they have become more complex, realistic, and socially oriented. Although video games have a pure entertainment status, their popularity has been deployed in the service of medicine with the aim of increasing patient health motivation.

Are all computer games completely harmless, and are they a great form of leisure? When it comes to the harms of computer games, they are mainly associated with excessive use. Taking a break will reduce the negative effects. To label them as “bad”, “violent”, and “aggressive” is to overlook many aspects inherent in modern games. People choose games with their advantages and disadvantages depending on their own inner motivation.

Don’t underestimate the importance of computer games as a stress reliever after a stressful day. It’s important to be able to distract yourself and just relax. And joining a virtual world is one of the easiest and most effective ways to escape from external problems for a while.

Most people who have experienced gaming either perceive the activity in a negative or a positive way. The indifferent ones, by and large, are few.

Related posts:

- How To Write A Good Compare And Contrast Essay: Topics, Examples And Step-by-step Guide

How to Write a Scholarship Essay

- The Best Online AP Courses For High School Students [Full Guide]

- Explaining Appeal to Ignorance Fallacy with Demonstrative Examples

Improve your writing with our guides

Definition Essay: The Complete Guide with Essay Topics and Examples

Critical Essay: The Complete Guide. Essay Topics, Examples and Outlines

Get 15% off your first order with edusson.

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

100% privacy. No spam ever.

Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2014

- Cite this reference work entry

- Frans H. van Eemeren 7 ,

- Bart Garssen 7 ,

- Erik C. W. Krabbe 8 ,

- A. Francisca Snoeck Henkemans 7 ,

- Bart Verheij 9 &

- Jean H. M. Wagemans 7

7183 Accesses

5 Citations

In this chapter, Toulmin’s contribution to argumentation theory is discussed. Toulmin presents in his model of argumentation a novel approach to analyzing the way in which claims can be justified in response to challenges. The model replaces the old concepts of “premise” and “conclusion” with the new concepts of “claim,” “data,” “warrant,” “modal qualifier,” “rebuttal,” and “backing.” Because of the impact Toulmin’s ideas about logic and everyday reasoning have had, he can be regarded as one of the founding fathers of modern argumentation theory.

In Sect. 4.2, the study The Uses of Argument , in which Toulmin expounded his views and explained his model, is introduced. Sect. 4.3 concentrates on the geometrical model of validity that is, according to Toulmin, at the heart of the misunderstandings about formal logic he wants to terminate. The distinction he makes in this endeavor between analytic and substantial arguments is treated in Sect. 4.4. In Sect. 4.5, the difference between field-invariant and field-dependent aspects of argumentative discourse is explained, which is vital to the alternative to the formal approach to analytic arguments offered by Toulmin. In Sect. 4.6 the forms arguments take and their validity are discussed, which leads to the presentation of Toulmin’s new model of argumentation in Sect. 4.7. Sect. 4.8 focuses on appropriations of the Toulmin model by argumentation theorists from different backgrounds. Sect. 4.9 discusses various applications of the model. In Sect. 4.10, the chapter is concluded with a critical appreciation of Toulmin’s contribution to argumentation theory.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Although the model does not appear in Toulmin’s later philosophical works, it can also be found in An Introduction to Reasoning , a practical textbook Toulmin published together with Richard Rieke and Allan Janik ( 1979 ). For the convenience of the reader, we shall refer in this chapter to the “updated edition” of The Uses of Argument published in 2003, which is readily accessible. The text of the book is unaltered since 1958, apart from the inclusion of a third (one-page) preface and a new (improved) index in the 2003 edition. It is important to notice that the 2003 edition has a new pagination.

In discussing Toulmin’s ideas we shall, like Toulmin, use the term argument , except when he speaks of the (central) use of argument to support a claim, as happens in the model, and then we use, in line with what we explained in Sect. 1.1 , the term argumentation .

In describing Toulmin’s model we use his terminology. In the textbook he coauthored with Rieke and Janik, Toulmin later replaced the term data with the term ground (Toulmin et al. 1979 ).

Peter Alexander, a colleague at Leeds, called it “Toulmin’s anti-logic book.” Much later, Toulmin’s Doktorvater at Cambridge, Richard Braithwaite, proved to be “deeply pained to see one of his own students attacking his commitment to Inductive Logic” (Toulmin 2003 , p. viii).

According to the preface to the 1964 paperback edition of The Uses of Argument , Toulmin’s target is “mathematical logic and much of twentieth-century epistemology” (p. viii).

In discussing the evaluation of arguments, Toulmin ( 2003 ) makes use of the words “soundness,” “validity,” “cogency,” and “strength,” without explaining the precise difference between them. This gives the impression that he uses them interchangeably.

In Human Understanding , Toulmin ( 1972 ) refers to what he considers to be the main issues discussed in The Uses of Argument.

Wherever Toulmin refers to formal validity, he also uses this phrase. When he uses the word “valid” without this qualifier “formally,” he usually seems to be using it in the imprecise way it is ordinarily used in everyday language. Under the influence of ordinary language philosophy, he probably does so deliberately.

Toulmin allows for the view that formal criteria apply to mathematical arguments ( 2003 , p. 118).

Such a radical reorientation would for Toulmin amount to going back to the Aristotelian roots of logic. He refers several times to the first sentence of the Prior analytics , where Aristotle expresses the double aim of logic: logic is concerned with apodeixis (i.e., with the way in which conclusions are to be established), and it is also the formal, deductive, and preferably axiomatic science ( episteme ) of their establishment (Toulmin 2003 , pp. 2, 163, 173). However, according to David Hitchcock (personal communication), Toulmin misinterprets the first sentence of Aristotle’s Prior analytics . In the first place, the sentence introduces the Analytics as a whole, not just the Prior analytics , and the explanation of what apodeixis and epistêmê apodeiktikê are does in fact not come until the Posterior analytics . The Analytics as a whole is not a treatise about logic but about deductive science. The logic of the Prior analytics is the underpinning for the scientific proofs (demonstrations) discussed in the Posterior analytics . The opening sentence therefore does not describe the subject matter of logic but the subject matter of the philosophy of the deductive sciences. In the second place, epistêmê apodeiktikê is not the science of proof (demonstration), but the understanding (knowledge, scientific knowledge) that consists in the ability to prove (demonstrate) something.

In elaborating on this concept in Knowing and Acting , Toulmin ( 1976 ) compares the “geometrical” view (or model) of rationality with the “anthropological” and the “critical” view of rationality (or reasonableness) (see Sect. 1.2 of this volume for these three conceptions). Toulmin traces the high status of the geometrical model back to Plato, who took, according to him, axiomatized geometry, with theorems deduced formally from supposedly self-evident and unchallengeable axioms, as a model of knowledge (Toulmin 1976 , pp. 70–71).

To keep it simple, we use commonly accepted premises which are supposed to be self-evident (which they are not really). A fully correct example is the following argument from number theory: x + 0 = x ; x + sy = s ( x + y ); hence s 0 + s 0. Here “ s ” abbreviates “the successor of” and “ x ” and “ y ” are variables. The conclusion states that 1 + 1 = 2.

In The Uses of Argument , Toulmin refers to the logic of the syllogism when discussing the formal approach, but in his Preface to the updated edition of 2003, he adds that his criticisms were also directed at “a rigidly demonstrative deduction of the kind to be found in Euclidean geometry” (p. vii).

In his exposé Toulmin took the validity of the argument form in the example, the Barbara syllogism, to be self-evident. See Sect. 2.6 of this volume.

In fact, the diagram contains more information than the premises, since it exhibits the claim that A is a proper subset of B and B is a proper subset of C. We know that this is true in certain cases, but not in others.

To be more precise, the premises state that the set represented by the A circle is a subset of the set represented by the B circle and that the set represented by the B circle is a subset of the set represented by the C circle.

Because of the possibility of overlapping, you need in fact four different Euler diagrams to accommodate the four different possibilities, and in one of the four diagrams of the premises, the circle for the minor term is coextensive with the circle for the major term.

As Hamby ( 2012 ) makes clear, it is very difficult to make sense of the various ways in which Toulmin characterizes the distinction between analytic and substantial arguments.

Toulmin does not use the term contained ; he speaks (in a similar vein) of an analytic argument “if and only if the backing for the warrant authorising it includes, explicitly or implicitly, the information conveyed in the conclusion itself” ( 2003 , p. 116). Unlike we do here, Toulmin does not use the term premise , but speaks of data , warrant , and backing . We shall introduce and explain these terms in Sect. 4.6 when preparing the introduction of the Toulmin model.

David Hitchcock (personal communication) notices an inconsistency in this exposé. If substantial arguments often involve type-jumps, then some substantial arguments do not involve type-jumps. According to Hitchcock, a type-jump from the premises to the conclusion cannot be the reason why the premises do not entail the conclusion. An argument is substantial when there is a type-jump, but it can also be substantial when there is no type-jump.

To be more precise, according to Toulmin, the conclusions of some substantial arguments are necessitated by the data, but not in the sense of being logically necessitated ( 2003 , pp. 18–20).

This does not mean that Toulmin thinks that analytic arguments are always formally valid and substantial arguments always formally invalid: “An argument in an[y] field whatever may be expressed in a formally valid manner, provided that the warrant is formulated explicitly as a warrant and authorises precisely the sort of inference in question […]. On the other hand, an argument may be analytic, and yet not be expressed in a formally valid way: this is the case, for instance, when an analytic argument is written out with the backing of the warrant cited in place of the warrant itself” ( 2003 , p. 125).

Argumentation that is conducted in accordance with a proper procedure and agrees with the pertinent soundness conditions can be viewed as “formally” valid in a procedural sense. See Sect. 6.1 of this volume for “formal” in the procedural (regulative) sense ( formal 3 ).

Toulmin extends his field-dependence thesis beyond the field of science to fields like morals and aesthetics.

Notice that Toulmin thinks that even in mathematics standards have evolved (Toulmin 2006 ).

In a similar way as we discussed when defining argumentation in Sect. 1.1 of this volume, Toulmin seems to construe the arguments he is interested in as (dialectical) verbal products resulting from a (dialectical) process of argumentative discourse.

Ausín ( 2006 ) argues that in this respect Toulmin’s approach resembles that of Leibniz, who also turned to jurisprudence as a model for reasoning. Also in other respects Toulmin’s conception of rationality is not as irreconcilable with that of Leibniz as Toulmin himself suggests. Leibniz distinguishes between contingent and necessary truths. Because the logical calculus does not apply to the first, the weighing argumentative method should be used instead. When trying to rationally justify contingent statements, Toulmin and Leibniz both share the view that rationality must be open to differences, pluralism, and controversy.

It is probable that Toulmin used the concept of “logical type” as it was in introduced by Ryle in 1949: “The logical type or category to which a concept belongs is the set of ways in which it is logically legitimate to operate with it” (Ryle 1976 , p. 10). The book in which Ryle used this concept had been highly influential, so Toulmin may have regarded the concept as so familiar that he did not think it necessary to give a definition.

Toulmin also speaks of the “moral” of a modal term, as in “the moral of a fable.”

Some of the implications Toulmin attaches to this observation relate to semantic and philosophical questions that are not directly relevant here. They pertain to the development of an adequate semantic theory for modal words and to the vigorous philosophical controversy about probability in the 1960s. In that controversy, Toulmin opposed the views on probability put forward by Carnap ( 1950 ) and Kneale ( 1949 ).

For the influence of the legal philosopher H. L. A. Hart on Toulmin’s views of defeasibility and the need for rebuttals, see Sect. 11.3 of this volume.

A qualifier need not always weaken the claim. As Toulmin says “Some warrants authorise us to accept a claim unequivocally, given the appropriate data – these warrants entitle us in suitable cases to qualify our conclusion with the adverb ‘necessarily’” ( 2003 , p. 93).

In Goodnight ( 1993 ) it is argued that the situation can be even more complex, because it may happen that the selection of backing to the warrant itself stands in need of justification. His legitimation inferences however do not justify the step from the backing to the warrant, but the selection of backing for the warrant (see Goodnight 2006 ).

It is the “D, W/B, so C” pattern that Toulmin contrasts with the analysis in Aristotelian categorical syllogistic of arguments as fitting a “Minor premise; major premise; so conclusion” pattern. See Sect. 2.6 of this volume.

According to Trent ( 1968 ), Toulmin does not claim completeness for his model, only adequacy for the purposes of the discussion.

With regard to the use of modal terms in qualifiers, Ennis ( 2006 ) presents and defends a delimited version in terms of speech acts of Toulmin’s contextual definition of the qualifier “probably.” With Toulmin, Ennis maintains “When I say ‘S is probably P’, I commit myself guardedly, tentatively or with reservations to the view that S is P, and (likewise guardedly) lend my authority to that view” (p. 163). In Ennis’s view the qualifier “probably” allows one to guardedly commit to a statement. Any attempt to reduce this qualifier to a numeric value (i.e., formalization) will not do justice to actual use, for it will never grasp the true implications of a tentative commitment. Ennis stresses the need to focus on real arguments, not artificial ones.

For the purpose of illustration, it is assumed (falsely) that the two conditions mentioned in the Harry example constitute a complete list.

Schellens ( 1979 ) observes that, in this case, R no longer functions as a condition of rebuttal. Instead, there are three data: “Harry was born in Bermuda,” “Neither of his parents were aliens,” and “He has not become a naturalized American” and a complex warrant “A man born in Bermuda will generally be a British subject unless his parents are aliens or he has become a naturalized American.” If the counter-rebuttals are to be treated as data, then the warrant would be “Given that a person was born in Bermuda, has at least one parent that was not an alien, and has not become a naturalized American, then you may take it that the person must be a British subject.”

It should be noted that Toulmin realizes that the validity of the “Data; warrant; so conclusion” argument is a consequence of the applicability and adequacy of the warrant rather than its formal properties ( 2003 , p. 111).

Toulmin’s view that validity is ultimately field-dependent implies that in principle every argument field may claim rationality for the arguments being used in that field. The only condition Toulmin requires is that in the field concerned the warrant must be accepted as authoritative.

See Sect. 2.6 of this volume for a discussion of Aristotle’s syllogistic.

In personal communication Hitchcock emphasized that this is an incorrect and inadequate account of formal validity as contemporary logicians conceive of it. First, not all arguments whose conclusions can be obtained by shuffling the parts of their premises are formally valid: “No horses are humans; all humans are animals; therefore, no horses are animals.” Second, not all formally valid arguments have conclusions that can be obtained by shuffling the parts of their premises: “You have credit for three one-semester courses in philosophy; therefore, you have met the prerequisite for this course of either being registered in a program in philosophy or having credit for at least two one-semester courses in philosophy.” On page 113 Toulmin ( 2003 ) expresses a much better conception of formal validity: “to state all the data and backing and yet to deny the conclusion would land one in a positive inconsistency or contradiction.”

Toulmin is probably not using the word “tautology” here in the logician’s sense, derived from Wittgenstein’s Tractatus , of a statement that is true regardless of how the world is, but in the older sense, common in literary criticism, of a discourse in which a point is repeated.

According to Hitchcock (personal communication), this claim is false. It is sometimes not at all obvious that information contained in the premises of a formally valid argument includes the information in the conclusion. For example, it took Bertrand Russell’s letter to Gottlob Frege in 1902 to show that the Basic Law V in his Grundgesetze (published in 1893) contained a contradiction. In fact, according to Gödel’s incompleteness theorem (whose proof was published in 1931), any consistent axiomatization of arithmetic has information in the axioms that cannot be gotten out of them by the rules of inference in the underlying logic. In Hitchcock’s view, Toulmin’s skepticism regarding the power of formally valid reasoning is certainly not justified. Mathematical proofs sometimes have surprising conclusions, yet are analytic in any defensible sense of that concept.

In personal communication Hitchcock explained that Toulmin’s skepticism about analytic arguments is not justified. Mathematical proofs sometimes have surprising conclusions, yet are analytic in any defensible sense of that concept. Examples are the proofs that the diagonal of a square is incommensurable with its side, that the square root of 2 is irrational, that no consistent axiomatization of arithmetic is complete, that there is no mechanical decision procedure for the logic of the quantifiers “all” and “some,” that there are only five regular solids (Toulmin 1976 , p. 67; cf. Aberdein 2006 , pp. 332–334), and so on. Given Toulmin’s first degree in mathematics and physics, Hitchcock finds his blindness to the power of formally valid reasoning hard to understand.

Loui ( 2006 ), who emphasized the influence that Toulmin’s ideas have had, reports that The Uses of Argument is Toulmin’s most cited work and that citations in the leading journals in the social sciences, humanities, and science and technology put Toulmin among philosophers of science and philosophical logicians in the top 10 of the twentieth century.

In citing the influences that have led to the rise of informal logic, Johnson and Blair ( 1980 ) explicitly mention the Toulmin model.

As is explained in Sect. 7.2 of this volume, Toulmin’s radical critique, and the new perspective on argumentation he provided, has been an inspiration to explore this territory with other models and instruments than those supplied by formal logic.

A recent interest in the Toulmin model was instigated by David Hitchcock, who dedicated an OSSA Conference he organized at McMaster University in May 2005 partly to the Toulmin model. Rather than concentrating on a critical evaluation of the Toulmin model, the papers focused on providing interpretations of elements of the model that are not sufficiently clear, revaluing elements that deserve more attention, and proposing necessary additions (see Hitchcock and Verheij 2006 ).

According to Hitchcock ( 2003 ), “Toulmin equivocates on whether a warrant is a statement or a rule, often within the space of two pages” (p. 70). Hitchcock believes this equivocation to be harmless since a warrant-statement is the verbal expression of a warrant-rule.

In making this comparison it should be noted that if the warrant is viewed as a bridging premise (different from Hitchcock’s interpretation), it is only a part of the argument scheme. This does not mean, of course, that warrants cannot be used to categorize argument schemes. As far as Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s notion of argument scheme is concerned, it should be noted that this notion is rather loose. Some of the associative argumentative schemes they distinguish do not seem to represent a general rule. See Sect. 1.3 of this volume for the notion of argument schemes.

This is, by the way, certainly not the position advocates of identifying implicit premises, such as the pragma-dialecticians, generally take. See, for instance, Sect. 10.5 of this volume.

For Pinto’s contribution to argumentation theory, see also Sect. 7.6 of this volume.

According to Pinto, an argument (or inference) is valid only if it is entitlement-preserving.

By elaborating a suitable concept of reliability , Pinto tries to capture what gives warrants their normative force.

For Bermejo-Luque’s contribution to argumentation theory, see also Sect. 12.13 of this volume.

The term pragmatic force used by Bermejo-Luque corresponds, roughly, with the degree of strength of the illocutionary point as defined by Searle. Inference claims are assertives, but they may have different degrees and types of strength.

In Bermejo-Luque’s view, bridging the gap between reason and conclusion by justifying the inference by means of a warrant, as Hitchcock and Pinto envisage, leads to an infinite regress. She attempts to avoid the regress by pointing out that backings justify inferences.

Contrary to the argumentation scholars from the American communication community who build on Toulmin’s ideas concerning field-dependency, several philosophers from the informal logic community firmly reject them (e.g., Freeman, Hitchcock, Johnson, and Pinto).

Their contributions to argumentation theory are further discussed in Sect. 8.6 of this volume.

Hastings’s classification, however, is used as a point of departure by other scholars, such as Kienpointner (see Sect. 12.7 of this volume) and Schellens (see Sect. 12.8 of this volume), in their theorizing.

Ehninger and Brockriede ( 1963 ) use the terms evidence and reservation instead of the terms data and condition of exception or rebuttal .

Kock ( 2006 ) argues that the typology of warrants concerning practical claims that stems from Brockriede and Ehninger is insufficient for pedagogical applications. In his essay “Multiple warrants in practical reasoning,” he maintains that the singleton set of the “motivational” warrant should be extended and refined. The resources for the extension and refinement, he holds, can be found in the ancient rhetorical handbook Rhetorica ad Alexandrum . On the basis of this handbook, Kock arrives at a taxonomy of warrants “invoked in arguing about actions” (p. 254). When it comes to actions in general, the warrants can be based on the following categories: (1) just ( dikaia) , (2) lawful ( nomina ), (3) expedient ( sympheronta ), (4) honorable ( kala ), (5) pleasant ( hēdea ), and (6) easy of accomplishment ( rhaidia ). For more difficult actions the warrants may be based on the following two categories: (1) practicable ( dynata ), and (2) necessary ( anankaia ) (p. 255).

Brockriede and Ehninger’s definition of substantive, motivational, and authoritative argumentation is slightly different from the classical tripartition into logos, pathos , and ethos discussed in Chap. 2, “Classical Backgrounds” of this volume. This is particularly true of authoritative argumentation, classical rhetoric being exclusively concerned with the speaker’s reliability and good character. It might be useful to add that in his Rhetoric Aristotle considers only logos as a means of persuasion by argument, while pathos and ethos are non-argumentative means (see Sect. 12.8 of this volume).

A rhetorical epicheireme resembles Brockriede and Ehninger’s authoritative argumentation, which is a rhetorical means of persuasion based on ethos.

In this way Toulmin counters the skepticism in British analytic philosophy of the 1960s about general claims, psychological claims, and moral claims. This part of the Toulmin case stands even if one rejects the claim that warrants can neatly be assigned to fields that can be identified with academic disciplines.

Also outside the United States the model is used in several textbooks, for example, in Schellens and Verhoeven ( 1988 ) (see Sect. 12.8 ).

In their textbook, Toulmin, Rieke, and Janik ( 1979 ) use the term grounds instead of data , clarify the concept of a warrant, and include five chapters on argument in specific fields (law, science, the arts, management, ethics) in which they exemplify Toulmin’s ( 1992 ) point that it is not just the warrants and backings that vary from field to field.

It is noteworthy that, unlike other authors before them, Toulmin, Rieke, and Janik ( 1979 ) do not present a general taxonomy of warrants or argument schemes.

In various reviews of The Uses of Argument , it is rightly assumed that Toulmin regards his model as generally applicable. Cowan, for one, writes: “This pattern has, according to Toulmin, the necessary scope to encompass all arguments” ( 1964 , p. 29).

This part of Toulmin, Rieke, and Janik ( 1979 ) underlies Toulmin’s remark quoted in Sect. 4.7 from his keynote speech at the 1990 ISSA conference about how he would expand his description of the field-dependence of argumentation if he were to write The Uses of Argument again.

Like Ehninger and Brockriede ( 1963 ), Crable ( 1976 ) uses the terms evidence and reservation to refer to the data and the rebuttal.

This may be no surprise, since Crable ( 1976 ) refers to Toulmin as his “most profound influence” and “a source of challenge and insight” (p. vi).

Prakken ( 2006 ) argues that, in its frequent use of an argument scheme approach, the field of artificial intelligence and law (AI & Law) has taken to heart some of the lessons of The Uses of Argument . It is also recognized that premises can play different roles (analogous to those of Toulmin’s data and counter-rebuttal) and that arguments are defeasible. The field-related treatment of argument schemes confirms Toulmin’s idea that the criteria for evaluating arguments differ from field to field. Prakken maintains that AI & Law has developed an account of the validity of reasoning that applies to every argument and is nevertheless formal and computational.

According to Tans ( 2006 ), a warrant should be understood as an abstraction from the data, which gets refined dynamically by discursive testing of its authority. Tans supports his view by using examples from legal practice – i.e., within the context of the Supreme Court in the United States – and captures an alternative diagram of the Toulmin model in his exposé.

See Abelson ( 1960–1961 ), Bird ( 1959 ), Castaneda ( 1960 ), Collins ( 1959 ), Cooley ( 1959 ), Cowan ( 1964 ), Hardin ( 1959 ), King-Farlow ( 1973 ), Körner ( 1959 ), Mason ( 1961 ), O’Connor ( 1959 ), Sikora ( 1959 ), and Will ( 1960 ). Less hostile but sometimes also critical were the reactions when the German translation of The Uses of Argument was published in 1975: Huth ( 1975 ), Schwitalla ( 1976 ), Metzing ( 1976 ), Schmidt ( 1977 ), Göttert ( 1978 ), Berk ( 1979 ), Öhlschläger ( 1979 ), and Kopperschmidt ( 1980 ).

More recent and generally more positive reviews of the Toulmin model are Hample ( 1977 b), Burleson ( 1979 ), Reinard ( 1984 ), and Healy ( 1987 ).

See Sect. 12.7 for a short overview of Kienpointner’s views.

Hitchcock notes (personal communication) that Toulmin ( 2006 ) later mistakenly claimed that Bird described The Uses of Argument in his review as “a rediscovery of Aristotle’s Topics” (p. 26).

According to Hitchcock (personal communication), Bird’s analysis is suspect, since the topical difference of medieval logic does not provide justification of the topical maxim (which is a rule of inference, rather like Toulmin’s warrant) but rather a specification of it.

Cf. for other criticisms of Toulmin’s treatment of fields of argument Habermas ( 1981 ), who opted as a consequence for a different approach.

In The Uses of Argument , Toulmin assumes that the main function of an argument is to justify a conclusion. According to Cowan ( 1964 , pp. 32, 43), its function is to supply a lucid organization of the material. Only in analytic arguments this objective is realized to the maximum. Cowan thinks that Toulmin’s substantial arguments can easily be made analytic by making one or more unexpressed premises explicit. The kind of “reconstructive deductivism” promoted by Cowan is criticized by informal logicians. For a discussion of these criticisms and a defense of deductivism, see Groarke ( 1992 ).

In spite of the fact that Toulmin is discussing the possibility of explaining validity in terms of formal properties in a geometrical sense, it might be the case however that, here too, he uses the term valid(ity) in its ordinary common speech meaning of being good, comparable to its use in phrases like “valid passport” and “valid point.”

By the way, unlike what Toulmin suggests, argument 1-2a-3 is in this form not formally valid in, say, standard syllogistic logic, propositional logic, or predicate logic. The same is true for the argument (1) “Petersen is a Swede” (2a) “A Swede is almost certainly not a Roman Catholic” so (3) “Petersen is almost certainly not a Roman Catholic.” This argument does in fact not even become formally valid if the warrant (2a) is interpreted as a major premise: (2) “Almost no Swedes are Roman Catholics.”

If an argument is to be formally valid, this can only be the case if and only if its conclusion can be obtained by the premises by a mere shuffling of terms, as Toulmin thinks formal validity to be defined. A condition for formal validity on the warrant would then be that it includes any term in the conclusion that is not in the data; it need not, and generally does not, include any term in the conclusion that is not in the data. According to Hitchcock (personal communication), the warrant is a license to infer from the sort of things said in the data about whatever is common to data and conclusion that which is said in the conclusion.

It is not exactly Toulmin’s position that only experts in a particular field are competent evaluators, but it may be true that in problematic cases the experts in a field are indeed the ultimate authority on what warrants are acceptable in that field. Going by Toulmin ( 2006 ), he seems to recognize this.

In response to the claim that, in practice, it is often difficult to establish which statements are the data and which statement is the warrant, Hitchcock ( 2003 ) reports having analyzed 50 samples he extracted randomly. For 49 arguments, he had no difficulty in singling out an applicable “inference-licensing covering generalization.”

For similar and other objections to the distinction between data and warrants, see Schellens ( 1979 ), Johnson ( 1980 ), and Freeman ( 1991 , pp. 49–90).

In spite of the fact that – according to Hitchcock – van Eemeren and Grootendorst’s example is unrealistic, it still poses a problem for the Toulmin model. Hitchcock thinks that this problem can be solved by pointing to the fact that “a first-order particular statement is logically equivalent to a second-order universal generalization, and thus can function as a general rule of inference” (personal communication).

Another option than issuing this singular statement would be, for instance, to point out that Harry was not born in Bermuda but enjoys for some other reason the same status.

Toulmin states that warrants are general, rule-like statements (p. 91), which is a problem here. He does not explicitly require the specific information provided in data to be confined to particular statements. Both Toulmin ( 2003 ) and Toulmin, Rieke, and Janik ( 1979 ) focus on examples in which the data (or grounds) are singular statements about a particular individual. The textbook even says explicitly that the demand for grounds is a demand for specific features of a specific situation rather than for general considerations (Toulmin et al. 1979 , p. 33). Nevertheless Toulmin allows for a universal statement like “All club-footed men have difficulty in walking” to be construed as a factual report of our observations that can function as a datum (Toulmin 2003 , p. 106).

According to Hitchcock (personal communication), the warrant is “If a man born in Bermuda is a British subject, then Harry is a British subject” or “Given that a man born in Bermuda is a British subject, we may take it that Harry is a British subject.” In statement form the rule of inference involved would go as follows: “Harry has whatever status belongs to a man born in Bermuda.” Hitchcock notes that this statement follows logically from the statement that Harry was born in Bermuda. It need not be logically equivalent to it.

Initially the model was not so much used for the purpose of evaluation, Hastings ( 1962 ) being an early exception. Later others joined in. See Sect. 4.8 .

For a survey of practical problems confronted in applying the Toulmin model to the analysis of argumentative texts, see Schellens ( 1979 ), who also offers some solutions.

For “complex” argumentation as distinguished from “single” argumentation, see Sect. 1.3 of this volume.

If a “micro-argument” is indeed equivalent with “single” argumentation, which is probably not what Toulmin had in mind, he claims that his way of laying out micro-arguments makes apparent the sources of their validity, i.e., the extent to which the arguments justify their conclusions, which may involve more than single argumentation.

For the notion of “subordinatively compound” argumentation, see Sect. 1.3 of this volume.

For further discussion of Freeman’s contribution to argumentation theory, see Sect. 7.7 of this volume.

Abelson, R. (1960–1961). In defense of formal logic. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 21 , 333–346.

Article Google Scholar

Aberdein, A. (2006). The uses of argument in mathematics. In D. L. Hitchcock & B. Verheij (Eds.), Arguing on the Toulmin model. New essays in argument analysis and evaluation (pp. 327–339). Dordrecht: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Ausín, T. (2006). The quest for rationalism without dogmas in Leibniz en Toulmin. In D. L. Hitchcock & B. Verheij (Eds.), Arguing on the Toulmin model. New essays in argument analysis and evaluation (pp. 261–272). Dordrecht: Springer.

Beardsley, M. C. (1950). Practical logic . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Google Scholar

Berk, U. (1979). Konstruktive Argumentationstheorie [A constructive theory of argumentation]. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Frommann-Holzboog.

Bermejo-Luque, L. (2006). Toulmin’s model of argument and the question of relativism. In D. L. Hitchcock & B. Verheij (Eds.), Arguing on the Toulmin model. New essays in argument analysis and evaluation (pp. 71–85). Dordrecht: Springer.

Bird, O. (1959). The uses of argument. Philosophy of Science, 9 , 185–189.

Bird, O. (1961). The re-discovery of the topics: Professor Toulmin’s inference warrants. Mind, 70 , 534–539.

Botha, R. P. (1970). The methodological status of grammatical argumentation . The Hague: Mouton.

Brockriede, W., & Ehinger, D. (1960). Toulmin on argument. An interpretation and application. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 46 , 44–53.

Burleson, B. R. (1979). On the analysis and criticism of arguments. Some theoretical and methodological considerations. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 15 , 137–147.

Carnap, R. (1950). Logical foundations of probability . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Castaneda, H. N. (1960). On a proposed revolution in logic. Philosophy of Science, 27 , 279–292.

Collins, J. (1959). The uses of argument. Cross Currents, 9 , 179.

Cooley, J. C. (1959). On Mr. Toulmin’s revolution in logic. Journal of Philosophy, 56 , 297–319.

Cowan, J. L. (1964). The uses of argument – An apology for logic. Mind, 73 , 27–45.

Crable, R. E. (1976). Argumentation as communication. Reasoning with receivers . Columbus: Charles E. Merill.

Cronkhite, G. (1969). Persuasion. Speech and behavioral change . Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill.

van Eemeren, F. H., Grootendorst, R., & Kruiger, T. (1978). Argumentatietheorie [Argumentation theory]. Utrecht/Antwerpen: Het Spectrum. (2nd extended ed. 1981; 3rd ed. 1986). (English transl. (1984, 1987)).

van Eemeren, F. H., Grootendorst, R., & Kruiger, T. (1984). The study of argumentation . New York: Irvington. [trans. Lake, F. H., van Eemeren, R., Grootendorst, R., & T. Kruiger (1981). Argumentatietheorie (2nd ed.). Utrecht: Het Spectrum. (1st ed. 1978)].