Intelligent. Optimistic. Curious.

- Latest Show

- Arts & Culture

- Politics & History

- Science & Technology

- Religion & Philosophy

- Going For Broke

- Dangerous Ideas

- Deep Tracks

- Sonic Sidebar

- The News From Poems

- Ideas from Africa

- Find A Station

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

You are here

'i am because we are': the african philosophy of ubuntu.

Steve Paulson (TTBOOK)

Rene Descartes is often called the first modern philosopher, and his famous saying, “I think, therefore I am,” laid the groundwork for how we conceptualize our sense of self. But what if there’s an entirely different way to think about personal identity — a non-Western philosophy that rejects this emphasis on individuality?

Consider the African philosophy of “ubuntu” — a concept in which your sense of self is shaped by your relationships with other people. It’s a way of living that begins with the premise that “I am” only because “we are.” The Kenyan literary scholar James Ogude believes ubuntu might serve as a counterweight to the rampant individualism that’s so pervasive in the contemporary world.

"Ubuntu is rooted in what I call a relational form of personhood, basically meaning that you are because of the others," said Ogude, speaking to Steve Paulson and Anne Strainchamps in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. "In other words, as a human being, you—your humanity, your personhood—you are fostered in relation to other people."

In practice, ubuntu means believing the common bonds within a group are more important than any individual arguments and divisions within it. "People will debate, people will disagree; it's not like there are no tensions," said Ogude. "It is about coming together and building a consensus around what affects the community. And once you have debated, then it is understood what is best for the community, and then you have to buy into that."

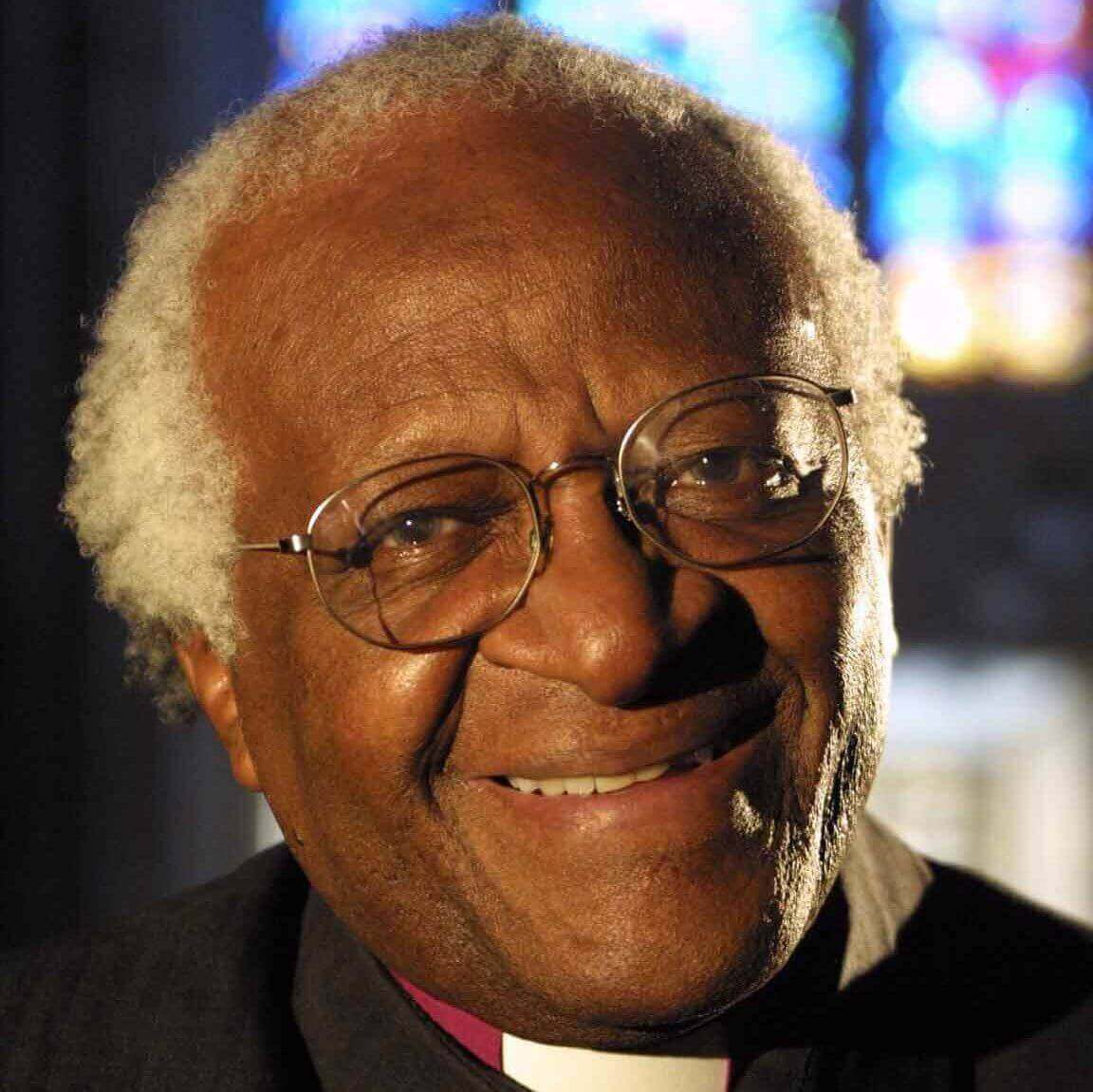

Archbishop Desmond Tutu drew on the concept of ubuntu when he led South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which helped South Africa reckon with its history of apartheid. Ubuntu promotes restorative justice and a community-centric ethos. "We have the ability, as people, to dig into our human values, to go for the best of them, in order to bring about healing and to bridge the gap," Ogude said. This idea also extends to our relationships with the non-human world of rivers, plants and animals.

Ogude spoke with Steve and Anne at the first African Humanities Workshop, which took place at the University of Addis Ababa. The workshop was sponsored by the Consortium of Humanities Centers and Institutes (CHCI). Here's an excerpt from the transcript of their conversation, which you can find on IDEA S, a publication published by CHCI.

Steve Paulson: We've been talking about ubuntu in this legal sense of how to redress wrongs, and I am wondering at the more everyday level, how ubuntu plays out. I'm thinking in terms of what constitutes “a good life.” In the West, that concept seems to be rooted in the concept of selfhood: how I think about, or know, myself or the course of my life and achievements. It's not necessarily defined by my relationship with other people. Is there a different way of thinking about the self in this African tradition you've been describing? James Ogude: There's a sense in which ubuntu as a concept, and the African communitarian ethos, imposes a sense of moral obligation regarding your responsibility for others even before you think of yourself. You must, as the Russian critic Bakhtin would say, look into another person’s eyes and have that person return the gaze. When the gaze is returned, that recognition is what humanizes you. SP: There's empathy built into it. JO: An empathy, yes, there's empathy, there's trust, that is built in this process. That, for me, is the moral obligation that sometimes is absent when undue emphasis is placed on individualism and the self, when it’s “all about me,” and everybody else comes second. Yet, even the West is haunted by other, competing, values such as human rights. There have always been movements in the West that have prioritized the other over the self. That's why all human beings fundamentally have a certain element of conscience even when our societies may push us to be individualistic. A measure of responsibility is part of our obligation, whether it comes to us through religion or a moral obligation of duty to others.

You can read the full conversation on IDEAS .

James Ogude

- South Africa

- Understanding The Meaning Of Ubuntu...

Understanding the Meaning of Ubuntu: A Proudly South African Philosophy

Freelance Writer - instagram.com/andrewthompsonsa

South Africa is a country that carries massive collective trauma. The political system of institutionalised racism, called apartheid, was devastating for the majority of the population. Yet, in spite of the painful, oppressive system, many of those most deeply affected by it rose up and remained resolute and united – with some crediting one philosophical concept, that of ubuntu , as a guiding ideal.

Did you know you can now travel with Culture Trip? Book now and join one of our premium small-group tours to discover the world like never before.

The presence of ubuntu is still widely referenced in South Africa , more than two decades after the end of apartheid. It’s a compact term from the Nguni languages of Zulu and Xhosa that carries a fairly broad English definition of “a quality that includes the essential human virtues of compassion and humanity”.

In modern South Africa, though, it’s often simplified further and used by politicians, public figures and the general public as a catch-all phase for the country’s moral ideals, spirit of togetherness, ability to work together towards a common goal or to refer to examples of collective humanity.

A concept from the mid-1800s

The history of ubuntu shows that it is not a new concept, though – it’s one that Christian Gade, who wrote about it in a paper published by Aarhus University, says dates as far back as 1846.

“The analysis shows that in written sources published prior to 1950, it appears that ubuntu is always defined as a human quality,” said Gade. “At different stages during the second half of the 1900s, some authors began to define ubuntu more broadly: definitions included ubuntu as African humanism, a philosophy, an ethic and as a worldview.”

But as Gade points out, in spite of the ubuntu’s term history, it gained prominence more recently – primarily during transitions from white minority rule to black majority rule – in both South Africa, and neighbouring Zimbabwe .

“Of course, the search for African dignity in postcolonial Africa did not begin with the literature on ubuntu that was published during the periods of transition to black majority rule in Zimbabwe and South Africa,” said Gade.

Prior to these periods of political transition, Gade said, the search for African dignity was reflected in the thinking of many influential postcolonial African leaders – and has much to do with restoring dignity once the colonisers had moved on.

“Some of the narratives that were told to restore African dignity in the former colonies, which gained their independence in the late 1950s and 1960s, can be characterised as narratives of return,” said Gade, “since they contain the idea that a return to something African (for instance traditional African socialism or humanism) is necessary in order for society to prosper.”

An inappropriate term for modern South Africa

Much like the Danish philosophy of hygge, though, a lot is lost in the English translation, simplification and popularisation of the term. And this had lead some to criticise its use – especially in a modern South African context.

Thaddeus Metz, professor of philosophy at the University of Johannesburg, said that the term and ideas associated with ubuntu are often “deemed to be an inappropriate basis for a public morality” in present-day South Africa – for three broad reasons.

“One is that they are too vague; a second is that they fail to acknowledge the value of individual freedom; and a third is that they fit traditional, small-scale culture more than a modern, industrial society,” Metz wrote in an article published in the African Human Rights Law Journal.

Popular radio host, author and political commentator Eusebius McKaiser was quoted in the African Human Rights Law Journal saying that the term has several interpretations, and in a legal context is largely undefinable. He called it “a terribly opaque notion not fit as a normative moral principle that can guide our actions, let alone be a transparent and substantive basis for legal adjudication”.

Ubuntu embodied by Desmond Tutu

In spite of its potential shortcomings and misuses, ubuntu is a term that has a demonstrated the ability to unite the country towards common good – with many choosing a definition that bests applies to their circumstances.

Brand South Africa , an organisation mandated to develop and articulate the country’s national brand and identity, and to manage the country’s reputation, regularly uses the term in its messaging.

In 2013, the government made the plea for South Africans to “live with ubuntu” – although as Brand South Africa points out, this has different meanings for different people. “Goodness Ncube, a shoe salesman in Killarney, Johannesburg , defines ubuntu as the ability to relate to each other. Tabitha Mahaka, a Zimbabwean expatriate, believes it is about feeling at home in a foreign country. And Ismail Bennet, a store manager, has not even heard of the term,” Brand South Africa reported on its website.

But if there is one South African who can be credited with popularising, and embodying, the philosophical concept of ubuntu to its fullest, it’s Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Tutu fought vehemently against apartheid, but also chaired the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, under the principal of restorative justice.

As Metz points out, Tutu, who defined ubuntu as “I participate, I share”, drew on the principles of ubuntu to guide South Africa’s reconciliatory approach to apartheid-era crimes.

“As is well known, Tutu maintained that, by ubuntu, democratic South Africa was right to deal with apartheid-era political crimes by seeking reconciliation or restorative justice,” Metz wrote in an article for The Conversation .

Instead of emphasising the differences between people within South Africa, Tutu was famous for celebrating them.

“We are different so that we can know our need of one another, for no one is ultimately self-sufficient,” Tutu wrote in No Future Without Forgiveness (1999). “The completely self-sufficient person would be sub-human.”

For many in South Africa, it’s this approach that is the epitome of ubuntu.

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

Places to Stay

The most luxurious hotels in the world you can stay at with culture trip.

Guides & Tips

The best luxury trips to take this year.

The Most Amazing Kayaking Experiences With Culture Trip

The Best Private Trips You Can Book With Your Friends

The Best Private Trips to Book for a Special Occasion

The Ultimate South Africa Safari Holiday

The Best Private Trips to Book for Birthdays

Unforgettable Trips for Exploring National Parks

The Best Hotels in East London, South Africa, for Every Traveller

Top Small-Group Tours for Solo Travellers

The Best Hotels in Nelspruit for Every Traveller

The Best Places to Travel for Adventure

Culture trip spring sale, save up to $1,100 on our unique small-group trips limited spots..

- Post ID: 1001444060

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Thanks for signing up as a global citizen. In order to create your account we need you to provide your email address. You can check out our Privacy Policy to see how we safeguard and use the information you provide us with. If your Facebook account does not have an attached e-mail address, you'll need to add that before you can sign up.

This account has been deactivated.

Please contact us at [email protected] if you would like to re-activate your account.

When former president of the United States, Barack Obama, made a speech earlier this year in Johannesburg — at the 2018 Nelson Mandela annual lecture — he said that Mandela “understood the ties that bind the human spirit.”

“There is a word in South Africa — Ubuntu — that describes his greatest gift: his recognition that we are all bound together in ways that can be invisible to the eye; that there is a oneness to humanity; that we achieve ourselves by sharing ourselves with others, and caring for those around us,” Obama said.

Take Action: End Modern Slavery: Ask World Leaders to Ratify the Forced Labour Protocol

“Umuntu Ngumuntu Ngabantu” or “I am, because you are” is how we describe the meaning of Ubuntu. It speaks to the fact that we are all connected and that one can only grow and progress through the growth and progression of others.

Ubuntu has since been used as a reminder for society on how we should be treating others.

Speaking in South Africa for Nelson Mandela's 100th birthday, @BarackObama once again proved why he's a true Global Citizen 🙌🏾 pic.twitter.com/mvKn6WTAaE — Global Citizen (@GlblCtzn) July 21, 2018

Nelson Mandela once said : “A traveller through a country would stop at a village and he didn’t have to ask for food or for water. Once he stops, the people give him food, entertain him. That is one aspect of Ubuntu but it will have various aspects."

This example of the concept of Ubuntu shows the exact “oneness” Obama describes in his speech. As a society, looking after one another plays a major role in the success of humanity.

Mandela is the true definition of Ubuntu, as he used this concept to lead South Africa to a peaceful post-apartheid transition. He never had the intention of teaching our oppressors a lesson. Instead, he operated with compassion and integrity, showing us that for us to be a better South Africa, we cannot act out of vengeance or retaliation, but out of peace.

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, who led the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1996, also touched on the meaning of Ubuntu and how it defines us as a society.

“We think of ourselves far too frequently as just individuals, separated from one another, whereas you are connected and what you do affects the whole world,” he said. “When you do well, it spreads out; it is for the whole of humanity."

This is exactly what Ubuntu is about, it’s a reminder that no one is an island — every single thing that you do, good or bad, has an effect on your family, friends, and society. It also reminds us that we need think twice about the choices we want to make and the kind of impact they may have on others.

What exactly are we doing to live Ubuntu and make it a daily act in our lives?

Gender inequality, poverty, and violence happens on a global scale and these atrocities are what tells us that we need to do more as a society to actively live and breathe Ubuntu and put it into action on a daily basis.

Everyone in society needs to play a part, regardless of how small one may think it is. We all have a role to play and it’s of vital importance that our actions inspire others to want to be a part of a better and brighter future.

Ubuntu is also about justice, and particularly, justice for all people. As much as we must look after each other, it is also just as important that we exercise fairness and equality for all people regardless of race, gender, or social status.

So essentially, Ubuntu is about togetherness as well as a fight for the greater good. This is what Mandela was prepared to sacrifice his life for.

Ubuntu is the common thread and DNA that runs through the UN’s Global Goals, because without the spirit of Ubuntu within us, we cannot implement great change in our society. It’s imperative that we help all people, young and old, to achieve only the best for our future.

The Global Citizen Festival: Mandela 100 is presented and hosted by The Motsepe Foundation, with major partners House of Mandela, Johnson & Johnson, Cisco, Nedbank, Vodacom, Coca Cola Africa, Big Concerts, BMGF Goalkeepers, Eldridge Industries, and associate partners HP and Microsoft.

Demand Equity

What Is the Spirit of Ubuntu? How Can We Have It in Our Lives?

Oct. 19, 2018

I am, because of you: Further reading on Ubuntu

Boyd Varty speaks about Ubuntu, and how it can be seen in nature, at TEDWomen 2013. Photo: Kristoffer Heacox

“While it’s true that Africa is a harsh place, I also know it to be a place whose people, animals and ecosystems teach us about a more interconnected world,” says Varty in this emotional talk . “[Nelson] Mandela said often that the gift of prison was the ability to go within and to think, to create within himself the things he most wanted for South Africa: peace, reconciliation, harmony. Through this act of intense open-heartedness, he was to become the embodiment of what in South Africa we call Ubuntu . ‘I am; because of you.’”

Ubuntu is a beautiful — and old — concept. According to Wikipedia, at its most basic, Ubuntu can be translated as “human kindness,” but its meaning is much bigger in scope than that — it embodies the ideas of connection, community, and mutual caring for all. Liberian peace activist Leymah Gbowee ( watch her TED Talk ) once defined using slightly different words than Varty: “I am what I am because of who we all are.”

Interested in hearing more? Check out these sources.

- A (very) brief history of the term . For a great overview of the origins of Ubuntu, check out this article from Media Club South Africa . According to the piece, the first use of the term in print came in 1846 in the book I-Testamente Entsha by HH Hare. However, the word didn’t become popularized until the 1950s, when Jordan Kush Ngubane wrote about it in The African Drum magazine and in his novels. In 1960, the term made another leap as it was used at the South African Institute for Race Relations conference. According to Wikipedia , the concept of Ubuntu transformed into a political ideology in Zimbabwe, as the nation was granted independence from the United Kingdom. From there, in the 1990s, it became a unifying idea in South Africa, as the nation transitioned from apartheid. In fact, the word Ubuntu even appears in South Africa’s Interim Constitution, created in 1993: “There is a need for understanding but not for vengeance, a need for reparation but not for retaliation, a need for ubuntu but not for victimization.” .

- Desmond Tutu’s take . Ubuntu became known in the West largely through the writings of Desmond Tutu, the archbishop of Cape Town who was a leader of the anti-apartheid movement and who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work. As he approached retirement, Tutu was asked by Mandela to chair South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which sought to come to terms with the human rights offenses of the past in order to move into the future. In his memoir of that time period, No Future Without Forgiveness , Tutu writes, “Ubuntu is very difficult to render into a Western language. It speaks of the very essence of being human. When we want to give high praise to someone we say, ‘Yu, u nobunto’; ‘Hey so-and-so has ubuntu .’ Then you are generous, you are hospitable, you are friendly and caring and compassionate. You share what you have. It is to say, ‘My humanity is inextricably bound up in yours.’ We belong in a bundle of life.” For more analysis of how Ubuntu inspired Tutu, check out the book Reconciliation: The Ubuntu Theology of Desmond Tutu , written by Michael Battle, who studied under the archbishop. .

- Nelson Mandela’s take . In 2006, South African journalist Tim Modise interviewed Mandela and asked him specifically how he defines the concept of Ubuntu . Mandela replies, “In the old days when we were young, a traveller through a country would stop at a village, and he didn’t have to ask for food or water; once he stops, the people give him food, entertain him. That is one aspect of Ubuntu, but it will have various aspects. Ubuntu does not mean that people should not address themselves. The question therefore is, are you going to do so in order to enable the community around you, and enable it to improve? These are important things in life. And if you can do that, you have done something very important.” Watch Modise reflect on Mandela’s death on CBS This Morning . .

- Bill Clinton’s take. Former US President and 2007 TED Prize winner Bill Clinton ( watch his talk ) has embraced the philosophy of Ubuntu in his philanthropic work at the Clinton Foundation. “So Ubuntu — for us it means that the world is too small, our wisdom too limited, our time here too short, to waste any more of it in winning fleeting victories at other people’s expense. We have to now find a way to triumph together,” he said at the Clinton Global Initiative’s annual meeting in 2006. He’s applied these theories to politics as well. At a Labour Party conference in the UK in 2006 , he told the Labour delegates that society and collaboration is important because of Ubuntu. “If we were the most beautiful, the most intelligent, the most wealthy, the most powerful person — and then found all of a sudden that we were alone on the planet, it wouldn’t amount to a hill of beans,” he said. .

- Ubuntu, the operating system . Ubuntu is also the name of “the world’s most popular free OS.” It was named this by South African entrepreneur Mark Shuttleworth, who launched Ubuntu in 2005 to compete with Microsoft. Unbuntu is all about open source development — people are encouraged to improve upon the software so that it continually gets better. According to thi s article in The New York Times from 2009 , “Created just over four years ago, Ubuntu (pronounced oo-BOON-too) has emerged as the fastest-growing and most celebrated version of the Linux operating system, which competes with Windows primarily through its low, low price: $0.” Read up on Ubuntu’s latest release , or check out this list of great Ubuntu apps. .

- Ubuntu in basketball . According to ESPN.com , Ubuntu has had an effect on the NBA. The concept trickled into American professional basketball through Kita Thierry Matungulu, a founder of the South African organization Hoops 4 Hope. In 2002, Matungulu ended up at the same table at a fundraising event with Doc Rivers of the Boston Celtics and introduced him to the concept of Ubuntu. Five years later, Rivers invited Matungulu to speak to his team, and Ubuntu became their rallying call — it was even inscribed in their championship rings in 2008. Most recently, Rivers brought the concept to the Los Angeles Clippers. “Ubuntu works in life. It works for everybody. It doesn’t have to be basketball,” says Rivers. “It’s about being resilient and sharing the joy with your teammate when he’s doing well and feeling the pain when your teammate is feeling bad.” .

- Ubuntu to turn back climate change? Can Ubuntu’s ideas about collectivity be applied to climate change? South African activist Alex Lenferna argues yes. In an essay published today in Think Africa Press, “ What Climate Change Activists Can Learn From Mandela’s Great Legacy ,” Lenferna shares how thinking about our collective humanity could help form a united front of environmentalism. Of Ubuntu, Lenferna writes, “If we accept such a philosophy, then given our knowledge of anthropogenic climate change, our drive to enrich ourselves through the use of greenhouse gas intensive modes of development at the expense of our climate, our planet and the well-being of current and future generations should not be seen as true development but something that violates Ubuntu, diminishes our humanity, and makes us as individuals, nations, and as a global community, less than we could otherwise be.” This idea of Ubuntu inspiring an overhaul of our resource use is gaining traction — it came up at the Climate Change Conference in Durban, South Africa in January of 2012. Could this way of thinking extend across the globe?

- Subscribe to TED Blog by email

Comments (93)

Pingback: The singles of TAM - Page 1582

Pingback: UBUNTU WEAKENED BY MANDELA DAY | YFM

Pingback: Ubuntu - Travels and Tripulations

Pingback: UBUNTU | think authentic

Pingback: Märkamistest.

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of … | Matias Vangsnes

Pingback: » Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa - Nice World News

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | Travel Vacation Dream! Plan your next Vacation

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa – JUANMONEGRO.COM

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | Political Ration

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | Noticias de Paraguay

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | Go to News!

Pingback: Claire Ann Peetz Blog Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa - Claire Ann Peetz Blog

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | InfoCnxn.com

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | NewsCenterd

Pingback: Boyd Varty: What I learned from Nelson Mandela | Disorganized Trimmings

Pingback: Remembering A Giant, Today: Nelson Mandela | Racism Is Not A Game

What Archbishop Tutu’s ubuntu credo teaches the world about justice and harmony

Professor of Philosophy, University of Pretoria

Disclosure statement

Thaddeus Metz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Pretoria provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Archbishop Emeritus Bishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu’s 90th birthday on October 7 is a good occasion to reflect on the man’s contributions to South African society and global thought. I do so as a philosopher and in the light of ubuntu , the southern African (specifically, Nguni) word for humanness that is often used to encapsulate sub-Saharan moral ideals.

An ubuntu ethic is often expressed with the maxim,

A person is a person through other persons .

In plain English, this does not say much. But one idea that indigenous Africans often associate with this maxim is that your basic aim in life should be to become a real or genuine person. You should strive to realise your higher, human nature, in a word to exhibit ubuntu.

How is one to do that? “Through other persons”, which is shorthand for prizing communal or harmonious relationships with them. For many southern African intellectuals, communion or harmony consists of identifying with and exhibiting solidarity towards others, in other words, enjoying a sense of togetherness, cooperating and helping people – out of sympathy and for their own sake.

Tutu sums up his understanding of how to exhibit ubuntu as:

I participate, I share .

Apartheid as inhuman

Tutu is well known for having invoked an ubuntu ethic to evaluate South African society, and he can take substantial credit for having made the term familiar to politicians , activists and scholars around the world.

Tutu criticised the National Party , which formalised apartheid, and its supporters for having prized discord, the opposite of harmony.

Apartheid not only prevented “races” from identifying with each other or exhibiting solidarity with one another. It went further by having one “race” subordinate and harm others. In Tutu’s words, apartheid made people “less human” for their failure to participate on an evenhanded basis and to share power, wealth, land, opportunities and even themselves.

One of Tutu’s more striking, contested claims is that apartheid damaged not only black people, but also white people . Although most white people became well off as a result of apartheid, they did not become as morally good, or human, as they could have.

As is well known, Tutu maintained that, by ubuntu, democratic South Africa was right to deal with apartheid-era political crimes by seeking reconciliation or restorative justice. If “social harmony is for us the summum bonum – the greatest good” , then the primary aim when dealing with wrongdoing - as ones who hold African values - should be to establish harmonious relationships between wrongdoers and victims. From this perspective, punishment merely for the purpose of paying back wrongdoers, in the manner of an eye for an eye, is unjustified.

Controversies regarding Tutu’s ubuntu

Tutu is often criticised these days for having advocated a kind of reconciliation that lets white beneficiaries of apartheid injustice off the hook. But this criticism isn’t fair. Reconciliation for Tutu has not meant merely shaking hands after one party has exploited and denigrated another. Instead, it has meant that the wrongdoer, and those who benefited, should acknowledge the wrongdoing, and seek to repair the damage that he did at some real cost.

Tutu has remarked since the 1990s that

unless there is real material transformation in the lives of those who have been apartheid’s victims, we might just as well kiss reconciliation goodbye. It just won’t happen without some reparation.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission that he chaired was aimed at helping South Africans come to terms with their past and laid the foundation for reconciliation. In the fifth volume of its Report it was also adamant about the need for redistribution that would improve the lives of black South Africans. And Tutu has continued to lament the failure of white communities to undertake sacrifices on their own, and to demand compensation from them, for instance, by calling for a “wealth” or “white” tax that would be used to uplift black communities.

Another criticism of Tutu is that his interpretation of ubuntu has been distorted through the lens of Christianity. Although Tutu’s Christian beliefs have influenced his understanding of ubuntu, it’s also the case that his understanding of ubuntu has influenced his Christian beliefs . Tutu’s background as an Archbishop of the Anglican Church does not necessarily render his construal of ubuntu utterly unAfrican or implausible.

In particular, Tutu has controversially continued to believe that forgiveness is essential for reconciliation, and it is reasonable to suspect that his Christian beliefs have influenced his understanding of what ubuntu requires, here.

I agree with critics who contend that reconciliation does not require forgiveness. But, might not Tutu have a point in thinking that forgiveness would be part of the best form of reconciliation, an ideal for which to strive?

A neglected view of human dignity

Tutu’s ideas about humanness, harmony and reconciliation have been enormously influential, not merely in South Africa, but throughout the world. There is one more idea of his that I mention in closing that has not been as influential, but that also merits attention. It is Tutu’s rejection of the notion that what is valuable about us as human beings is our autonomy, which is a characteristically Western idea.

Instead, according to Tutu :

We are different so that we can know our need of one another, for no one is ultimately self-sufficient. The completely self-sufficient person would be sub-human.

In short, what gives us a dignity is not our independence, but rather our interdependence, our ability to participate and share with one another, indeed our vulnerability. This African and relational conception of human dignity has yet to influence many outside sub-Saharan Africa. I hope that this tribute might help in some way.

- Social justice

- Reparations

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- Moral virtues

- Desmond Tutu

- Virtue ethics

- Global perspectives

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Desmond Tutu, Ubuntu and the Possibility of Hope

Truth, Reconciliation, and Ubuntu

The day after Christmas day last year marked the death of Desmond Mpilo Tutu (1931 - 2021), the Nobel Prizewinner, anti-apartheid activist and former archbishop of Cape Town.

Tutu’s life was extraordinary, as is his legacy. Born in 1931 to Tswana and Xhosa parents, he studied theology in London before returning to his native South Africa, where he became a powerful voice in the fight against apartheid.

When I was growing up in the 1980s, Tutu was a familiar figure on the evening news: unstoppable, ebullient, fierce and uncompromising. In 1986, he was appointed Archbishop of Cape Town, and after the fall of apartheid, Nelson Mandela appointed him to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In his book No Future Without Forgiveness , Tutu wrote of how the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was an attempt to balance, “justice, accountability, stability, peace, and reconciliation” while attempting to set out a public account of the horrors of the apartheid regime. [1]

Since Tutu’s death, I’ve been thinking again about his work, and also about its philosophical underpinnings. Because Tutu was responsible for helping to disseminate and popularise a philosophical concept that has since become widespread (and has also lent its name to a popular distribution of the Linux operating system): and that concept, of course, is the concept of ubuntu .

I’ve been wanting to write more about African philosophical traditions for a while here on Looking for Wisdom. So, this seems to be a good time to launch into this idea of ubuntu , to ask what it means, and why it matters.

What is Ubuntu?

The term ubuntu (and its variants) is found in languages from the Bantu language family. It is made up of two parts: the root ntu , and the prefix ubu . The root means something like “entity” or “object”, while the prefix ubu (or mu ) simply means “human.” So the term as a whole suggests the entity that is a human being. As such, it is both descriptive, in that it suggests what human beings are, and it is prescriptive, in that it suggests what human beings should be. Or, to put it in fancier philosophical language, it is both ontological (it talks about the nature of human being), and it is ethical (it talks about what it is for this particular being, human being, to be good).

Scholarly references to the term ubuntu and its equivalents go back to the middle of the twentieth century. And perhaps one of the most famously concise glosses of the term is that from the philosopher John Mbiti. For Mbiti, ubuntu can be captured by the idea “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore, I am.” Mbiti explained the concept like this:

Only in terms of other people does the individual become conscious of his own being, his own duties, his privileges and responsibilities towards himself and towards other people. When he suffers, he does not suffer alone but with the corporate group; when he rejoices, he rejoices not alone but with his kinsmen, his neighbors and his relatives whether dead or living. [2]

Tutu’s Ubuntu

It is this reading of Ubuntu that became a central peg of Tutu’s own philosophy and theology. And while the idea of Ubuntu had deep roots in Bantu language-speaking communities, it was Tutu more than anyone who popularised the term, and gave it a contemporary religious, ethical, philosophical and political urgency. In his short essay, ‘Ubuntu: On the Nature of Human Community’, Tutu wrote as follows:

IN OUR AFRICAN weltanschauung , our worldview, we have something called ubuntu . In Xhosa, we say, “Umntu ngumtu ngabantu.” This expression is very difficult to render in English, but we could translate it by saying, “A person is a person through other persons.” We need other human beings for us to learn how to be human, for none of us comes fully formed into the world. We would not know how to talk, to walk, to think, to eat as human beings unless we learned how to do these things from other human beings. For us, the solitary human being is a contradiction in terms. Ubuntu is the essence of being human. It speaks of how my humanity is caught up and bound up inextricably with yours. It says, not as Descartes did, “I think, therefore I am” but rather, “I am because I belong.” I need other human beings in order to be human. The completely self-sufficient human being is subhuman. I can be me only if you are fully you. I am because we are, for we are made for togetherness, for family. We are made for complementarity. We are created for a delicate network of relationships, of interdependence with our fellow human beings, with the rest of creation. I have gifts that you don’t have, and you have gifts that I don’t have. We are different in order to know our need of each other. To be human is to be dependent. [3]

Recently, there has been a huge amount of philosophical work on the concept of ubuntu : far more than can be summarised in a short article. But for present purposes, it is worth looking at two aspects of ubuntu : the ontological aspect that asks what it means to be a person, and the ethical aspect that asks how we ought to live in the light of this.

Ubuntu and personhood

The first aspect of ubuntu , then, is a claim about the nature of personhood. For those brought up in cultures that are relatively individualistic, it is easy to imagine that we are born as individuals, unique and distinct, and that we gather together into societies to help meet our individual needs: for company, for connection, for security, for material well-being. In this kind of view, individuals come first. They are logically prior to the societies that they form and the social contracts that they make.

But the notion of ubuntu turns this on its head, reversing this order of priority. First, there is society. And our uniqueness, individuality, and personhood are all born out of this social connectedness. Taking the perspective of ubuntu , it makes no sense to ask about how individuals come together to form societies. We are, all of us, irreducibly bound up in social connections, webs and networks of material dependence, language, myth, story, and imagination. Even if we retire to the mountains to live as hermits, we are still, at root, irreducibly social beings. And being a hermit is not a refusal of society, but instead simply another way of living in relation to society.

This is the ontological claim of ubuntu philosophy. Society is not just an add-on, or an afterthought, or a set of necessary and regrettable compromises. Instead, it is the cradle of our personhood. And this ontological claim seems to me to be plausible–far more plausible, in fact, than the idea that individual personhood comes first. Our being in the world, as the German philosopher Martin Heidegger once put it, is a being-with-others ( Mitsein ).

Ubuntu and ethics

But ubuntu philosophy doesn’t just involve ontological claims. It also involves claims about how we ought to be, given that this is who we are. Here’s Tutu again,

In traditional African society, ubuntu was coveted more than anything else—more than wealth as measured in cattle and the extent of one’s land. Without this quality a prosperous man, even though he might have been a chief, was regarded as someone deserving of pity and even contempt. It was seen as what ultimately distinguished people from animals—the quality of being human and so also humane. Those who had ubuntu were compassionate and gentle, they used their strength on behalf of the weak, and they did not take advantage of others—in short, they cared, treating others as what they were: human beings. If you lacked ubuntu, in a sense you lacked an indispensable ingredient of being human. [4]

For Tutu, if we are indeed interdependent to the very root of our being, this means that we have irreducible obligations to others. But in meeting these irreducible obligations, it is not a question of the trade-off between self-interest and other-interest.

If we conceptualise society as a group of individuals entering a social contract, then to be in society always involves trading in some of our self-interest for the benefits that society may bring. In this view, society always involves a balance of competing interests.

But the idea of ubuntu holds a more radical possibility: the possibility of finding a way of living in society that augments the interests of everyone. This is an idea that goes beyond an ethics of consensus or accommodation, to an idea of mutual flourishing and uplift. And in this way, it offers a challenge to find new and creative forms of political organisation that might serve this mutual flourishing.

Tutu’s own work is a testimony to this. Later, writing about restorative justice and about the horrors of the testimonies gathered by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he claimed that, “Ubuntu (and so restorative justice) gives up on no one. No one is a totally hopeless and irredeemable case.” Because ultimately, to give up on anyone is to give up on interdependence, and it is to give up on the possibility of community.

And if is something perhaps utopian in this, Tutu’s own example reminds us that it is not an easy or naive utopianism. It is, instead, a robust and tough-minded kind of hope. a determination to find better ways of flourishing as the determinedly, irreducibly social beings that we are.

- Desmond Mpilo Tutu, No Future Without Forgiveness (Doubleday 1999). E-book.

- Quoted in Aloo Osotsi Mojola, ‘Ubuntu in the Christian Theology and Praxis of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and its Implications for Global Justice and Human Rights,’ in James Ogude, Ubuntu and the Reconstitution of Community (Indiana University Press 2019), chapter 2. E-book

- Desmond Mpilo Tutu, ‘Ubuntu: On the Nature of Human Community’, in God is Not A Christian (Rider 2011). E-book.

Further Reading

A recent and accessible philosophical account of Ubuntu, try the edited collection by James Ogude, Ubuntu and the Reconstitution of Community (Indiana University Press 2019).

For an extraordinary, searing account of the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, read Antjie Krog’s Country of My Skull: Guilt, Sorrow and the Limits of Forgiveness in The new South Africa , published by Three Rivers Press in 2000).

Sign up to my newsletter

You may also like.

Kautilya on the Crooked Business of Politics

The ancient Indian treatise on rulership, and the pragmatics of maintaining power

The Swoop and Surge of Life: Lucretius on Ethics in Motion

Ethics, power and a life in motion.

Lucretius on Chance, Necessity and Free Will

Lucretius, the Roman poet and philosopher, on free will, creativity and the mysterious swerve of an atom.

- Search Results

Everyday Ubuntu by Mungi Ngomane

The Southern African philosophy of ubuntu is based on the idea of our shared humanity and can be best described by the proverb, ‘A person is a person through other persons’. Mungi Ngomane, author of Everyday Ubuntu , introduces the idea of ubuntu , emphasising the significance of our connections and challenging the notion of the ‘self-made person’. The book finds its grounding in South Africa, journeying from the end of apartheid through the rebuilding of a nation.

What Is Ubuntu?

By Mungi Ngomane

Ubuntu is a way of life from which we can all learn. And it’s one of my favourite words. Whoever we are, wherever we live, whatever our culture, ubuntu can help us co-exist in harmony and peace.

My grandfather coined the term ‘Rainbow Nation’ for South Africa, after the country’s first democratic elections in 1994, to symbolize the unity of its cultures after the collapse of apartheid. I was lucky enough to be raised in a community, which taught me ubuntu as soon as I was able to walk and talk. My grandfather explained the essence of ubuntu as, ‘My humanity is caught up, is inextricably bound up, in yours.’

In my family, we were brought up to understand that a person who has ubuntu is one whose life is worth emulating. The bedrock of the philosophy is respect, for yourself and for others. So if you’re able to see other people, even strangers, as humans you will never treat them as disposable or without worth.

Ubuntu teaches us to look outside ourselves to find answers. It’s about seeing the bigger picture; the other side of the story. The meaning of the word ‘ ubuntu ’ varies between African countries and tribes. Rooted in Zulu wisdom, the philosophy of ubuntu has been passed down by word of mouth for generations.

I aspire to live by its teachings in my everyday life. By introducing this philosophy to you, I hope it enhances your life experience as much as it has enhanced mine. I hope it encourages you to reach out to the people around you – both friends and strangers – who make you who you are.

Lesson one: See yourself in other people

If we are able to see ourselves in other people, our experience in the world will inevitably be a richer, kinder, more connected one. If we look at others and see ourselves reflected back, we inevitably treat people better.

This is ubuntu . Ubuntu shouldn’t be confused with kindness, however. Kindness is something we might try to show more of, but ubuntu goes much deeper. It recognizes the inner worth of every human being – starting with you.

Ubuntu tells us we are only who we are thanks to other people. Of course we have our parents to credit for bringing us into the world, but beyond this there are hundreds – if not thousands – of relationships, big and small, along the way, which teach us something about life and how to live it well. Our parents or guardians teach us how to walk and talk. Our teachers at school teach us how to read and write. A mentor might help us find fulfilling work. A lover might teach us emotional lessons, both good and bad – we learn from all experiences. Every interaction will have brought us to where we are today.

However, in the West we are also taught that it’s a badge of honour to claim to be self-made. We applaud those whom we perceive as having achieved fame and fortune through their own efforts, happy to overlook the fact that nothing can be achieved in a vacuum. We are further taught that competition leads to self-fulfillment and progression, even though pitting yourself against others leads to unhelpful comparisons and a grinding sense of not being enough.

How often have you compared your own life to someone else’s and felt worse off? How often do you crave more, however much you already have? A bigger house. More money. More work, more time off.

However wonderful it is to celebrate the good things in our friends’ lives, many of us also follow hundreds – sometimes thousands – of strangers who appear to live lives that are richer, more fun and shinier than our own. These are people who we don’t know personally but who influence what we long to buy, the way we feel and our aspirations. The subtext is that an ‘influencer’ is a better person than the ordinary person.

Ubuntu teaches us the opposite of this and says that absolutely everyone on this earth is of equal value because our humanity is what matters the most. Instead of comparing ourselves to others, we should value other people’s contributions to our day-to-day life.

Sign up to the Penguin Newsletter

By signing up, I confirm that I'm over 16. To find out what personal data we collect and how we use it, please visit our Privacy Policy

March 6, 2015 by Jacky A. Yenga 34 Comments

The Spirit of Ubuntu

This is a story that has been shared online in various sites. The version below seems to be the most complete one. I am sharing this story as my very first blog because it is the perfect way for me to introduce you to a key African concept I will be exploring with you moving forward.

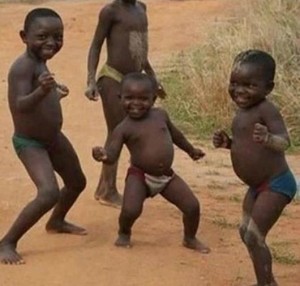

In some comments I read over the net, I saw that while many people praised the outcome, others had doubt about whether the story was real or just another fictional story created to make people feel good. Whether it is a “real” story or not, it accurately represents what many children who grew up in Africa have been taught about life. We value togetherness and collaboration and actively practice it. We believe in sharing with one another. It is true that modern life and “globalisation” has affected our traditional teachings and the way Africans live their lives today, but our foundational values are still true and their practice is still alive in many places.

This story is about true collaboration. This is the mindset I want you to understand, and to consider in your own life. Enjoy the story. I welcome your comments.

She explained how an anthropologist had been studying the habits and customs of this tribe, and when he finished his work, had to wait for transportation that would take him to the airport to return home. He’d always been surrounded by the children of the tribe, so to help pass the time before he left, he proposed a game for the children to play.

He’d bought lots of candy and sweets in the city, so he put everything in a basket with a beautiful ribbon attached. He placed it under a solitary tree, and then he called the kids together. He drew a line on the ground and explained that they should wait behind the line for his signal. And that when he said “Go!” they should rush over to the basket, and the first to arrive there would win all the candies.

When he said “Go!” they all unexpectedly held each other’s hands and ran off towards the tree as a group. Once there, they simply shared the candy with each other and happily ate it.

The anthropologist was very surprised. He asked them why they had all gone together, especially if the first one to arrive at the tree could have won everything in the basket – all the sweets.

A young girl simply replied: “How can one of us be happy if all the others are sad?”

The anthropologist was dumbfounded! For months and months he’d been studying the tribe, yet it was only now that he really understood their true essence…

Source : “ This is the Age of Ubuntu ” from harisingh.com . While the veracity of this story is unknown, the term itself is quite real .

Can you imagine living your own life with this mindset? Can you imagine everyone else around you having the same mindset? If that were the case, is there anything that we could NOT accomplish together? Some food for thoughts… I welcome your comments.

Until next time… STAY CONNECTED.

“If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” ~ African Proverb

Jacky A. Yenga

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

You’re welcome to share today’s article. when you do, please include this complete blurb with it:, jacky yenga, “the village wisdom messenger” and author of the upcoming book “the spirit of the village” powerfully combines both emerging scientific concepts and age-old wisdom to succeed at living a more enriched life the result is a global movement of conscious individuals who practice living a more authentic and connected life every day and who unleash their authentic expression of togetherness, share their own unique gifts and confidently make their difference in the world. trusted and celebrated for her wisdom and her down to earth, exotic, authentic and inspiring approach, jacky is quickly becoming a well-recognized leader of the transformational movement in the west. join her free 30-day village challenge at www.jackyyenga.com ..

December 7, 2017 at 9:33 am

Coming from the actual african country where this word originated (South Africa) I can tell you that Ubuntu is very high in the people’s belief system. For example, if you have a car, you HAVE TO lock it to avoid other people letting you “share” it with them. Same goes for everything in your house, if you don’t buy the best security possible you will “share” everything you own with other people. I can continue, but you get the point.

Ubuntu in South Africa is an idiology used to excuse crime, to praise stupidity (or at least a lack of capitalism) and to ultimately bend justice into the morphed picture it has today. You are right in stating that Ubuntu (loosely) means I am happy beacause others are happy, but it shouldn’t be forgotten that it extends into the terrain of “I suffer, so others should suffer with me”

December 19, 2017 at 5:17 am

Good point, and fair enough!

January 13, 2018 at 1:13 am

haha yeah i much prefer america where you are shot when you were in the vicinity of a crime.

and def nobody in america EVER tries to steal things, bc they don’t have ubuntu. what kind of fresh hell did you crawl out of my dude

August 1, 2018 at 3:44 pm

It’s just a proposal of a right idea, in my opinion, towards which the world needs to move. And, btw, in my opinion, it’s not about the existing system/s

January 11, 2020 at 7:38 pm

Please excuse “Tiny Ford” – he knows nothing about Ubuntu, and certainly his views do not represent what the majority of peace loving South Africans believe. Ubuntu IS a very beautiful and fundamental humane philosophy, which has much to teach the world. Attributing crime to ubuntu, is disingenous and ridiculous, at best. And quite possibly, simply racist.

February 16, 2020 at 5:27 am

Thanks Jonny.

February 12, 2020 at 4:18 pm

“.. but it shouldn’t be forgotten that it extends into the terrain of ‘I suffer, so others should suffer with me'”

But why we don’t say “I’m sad because others are sad.” I think in this context “I” is the result of “we” And doesn’t mean the one who suffer has right to ask the others for helping but that one will not be ignored from the others too.

July 8, 2020 at 12:37 pm

Ubuntu extends to other languages such as Ndebeles from Zimbabwe and it has nothing to do with crime. In the true spirit of ubuntu, there would be equal division of resources, where everyone has a fair chance and equal access to opportunities. On the contrary, in South Africa, the apartheid/ colonizer/slave master descendants drive the economy leaving the native people in poverty. So let’s not butcher and misinterpret ubuntu without examining the root of crime and history, which broke and bastardized the concepts of ubuntu.

August 19, 2020 at 9:36 am

Thank you so much for such an excellent clarification Sima!

March 10, 2018 at 7:51 am

I loved the story, whether true or not. These days when people tend to be selfish, this can go a long way to instil value of sharing and caring in kids.

April 8, 2018 at 2:40 pm

Imagine the kind of world we’d have if the spirit of Unbuntu was the dominant paradigm. It can happen, but only if enough people see it and claim it as their personal responsibility. The choice is ours. The time is now.

April 16, 2018 at 9:30 am

I so agree with your words! Thank you for your wise comment.

May 27, 2018 at 6:52 am

This beautiful story reveals two entirely different modes of being. On the one hand, there is the western and American mode of being which is predominantly ego-driven as can be seen from the way the anthropologist sets up the game: winner-takes-all. For someone to win, there must be losers. On the other hand, the way the children respond to the win-lose game shows an African philosophy rooted in the spirit of collaboration. It is rather unfortunate and tragic that the dehumanizing winner-takes-all mode of being has been imposed on the rest of the world as a result of military, economic, and cultural imperialism.

July 21, 2018 at 3:27 am

Great comment Anas. Thank you!

August 19, 2018 at 3:29 pm

I admire the story to the stage of googling it to get the full highlight, that showed that they people of Zulu have their own philosophers that generated this thought among the younger generation, a form of perception was build, but I may not agree with the story to be real, because of many things I may not like to start expanding…

October 13, 2018 at 6:51 am

Wow, i wish people all over the world will see things the its been seen in the story, the world would have been a better place. Tha reminds me of the musketeers, All for one and One for all. Nice piece.

January 26, 2019 at 12:49 pm

It is the positive side of humanity, called caring, loving, helping supporting one another. We are so floaded with negativity and real life death murder stealing cheating that we stop seeing the the good among humans. In July 2017 I got to such a frustrated state of Mind seeing all the bad news in SA so I started a FB page called POSITIVE RELATIONSHIPS IN SA to show the good side as well. Currently we have over 10500 members and climbing steadily. Members are in over 80 countries already. It is a controlled page where only Admin can add real life stories and no negativity is allowed. Only constructive responses. After reading this article I am going to stay today a new page to articulate the Ubuntu consept. Thank you.

February 5, 2019 at 4:44 am

Thank you for sharing, and thank you for what you do to contribute to the creation of a more positive world. Africa truly has a beautiful culture that is healing for the human soul, and that beauty is available to anyone who seeks it. I wish you all the best with Positive Relationships in SA!

March 4, 2019 at 7:52 pm

Hi Jacky. Africa is the place to be whether the west likes it or not. Ubuntu will simply cause Cain not to kill Abel again.

April 1, 2019 at 10:04 pm

Hahaha! Interesting comment Kolle.

April 4, 2019 at 4:47 pm

It hurts me to see the world being so demanding on us and we forget about being there for each other in love and unity.

The little children really have a lesson to teach us. You know, I have learnt something about this children… and that is their spirit of forgiveness to the extent that they forget you have beaten them awhile ago and willing to be your friend the next moment they practice forgiveness to the later.

Ubuntu with love

April 20, 2019 at 8:30 pm

Well said my friend.

July 7, 2019 at 8:35 am

The idea of Ubuntu makes sense and is interesting..Realistic probably not in our world etc but ok. I only have one difficulty in this story its just another colonial cliche of the missionary who comes and shares his sweets with the poor children of africa(by the way south africa is a country and there are no facts that say the whole of africa uses the concept of ubuntu). Lets just stop using these beautiful stories about a specific country and put the whole of africa in one bag(not all villages in south africa are poor etc…if u feel my flow). This is just another hippy movement spreading the word of ubuntu but what exactly are you doing to make changes etc…Preaching doesn’t help or living in a little bubble in a village of wisdom to block out all the bad of the world.Act and you will see very small changes around you..

August 12, 2019 at 9:35 pm

Hello Django, Thank you for your contribution. Since you took the time to share your point of view about this story, I thought it was only fair that I address some of the points you mentioned. First of all, the fact that something might be cliche doesn’t mean it isn’t true! Yes, South Africa is a country and I know this since I am from Cameroon myself, and I know how to differentiate one country from another in my continent. Yes, the concept of Ubuntu is found in OTHER COUNTRIES IN AFRICA, we just do not call it Ubuntu everywhere. It so happens that Ubuntu as a term was made popular in the rest of the world because of the process South Africa undertook after apartheid, but the concept itself has existed for centuries in many countries. Nobody said that all villages in South Africa are poor! Where did you see that here? As for your last remark, hopefully you too are doing what you preach, i.e. acting to make small changes. It’s always far too easy to criticize those spreading a message. Yes, I am making changes not only in my own village but in Vancouver where I live with the education I provide and other specific actions I take in my work and in my life. I am not preaching, but rather, (hopefully!) I am inspiring people to look at the world differently and realize that we are all rich and poor in different ways. The wisdom of Africa has a lot to offer to the rest of the world, it is pertinent in today’s reality and I strongly believe in it, and I do what I do based on that belief. What are you doing to make those small changes?

September 4, 2019 at 2:14 am

The same spirit is destroying properties and lives of Nigerians in South Africa?

September 21, 2019 at 7:58 am

What do you think, Nkoro? I’m sure you already have the answer to your own question.

April 9, 2020 at 5:25 pm

It’s a nice story but obviously a fabrication.

April 25, 2020 at 10:10 pm

Alain DeWitt: Why do you say “obviously”? Do you know about African traditions?

May 6, 2020 at 8:41 am

Hello Jacky, I am originally from Zimbabwe but have lived in Helsinki, Finland for 28years. I have recently founded an NGO Ubuntu-Fin. We are in the process of launching and designing a website and would very much like to use the photo with the kids sitting in a circle with their feet touching. We understand copyright laws and are kindly requesting for the use of the photo on our website. If we can use it could we have the the name of the photographer, the date and the exact location the photo was taken.

June 22, 2020 at 6:18 am

Hi Julia, I apologize for the delay. I took the picture from a friend’s page a long time ago, but I can’t remember who! Maybe if you search google with a description of the picture, you might find the original version. It seems like a long shot but it does work. Good luck!

June 10, 2020 at 6:20 pm

I was born and raised in South Africa (although I’ve been living abroad for many years). I can say with absolute certainty that Ubuntu is a real thing. And a very important part of all of us who come from that part of the world. And something that I have taken with me wherever I go. And something I take great pride in telling other people about. Because I believe that the world could use a bit more Ubuntu right now. Whether you agree with the philosophy or not, it’s ultimately rooted in our humanity and a belief that I am only because we are. And I think we can all agree that the world would be a better place if we all focussed a little bit more on the collective and remember to be kind to one another. Call it Ubuntu or call it by any other name. But just f*cking do it.

June 22, 2020 at 6:12 am

Thanks Annie. In Cameroon my country, we have a similar tradition with different names depending on the tribe we are from. The world could indeed use a big dose of this right now…

July 30, 2020 at 2:18 am

Thank you very much for the invitation :). Best wishes. PS: How are you? I am from France 🙂

August 19, 2020 at 9:25 am

Thanks Mark. Best wishes to you too.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Ubuntu, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and South African National Identity

2011, Thamyris/Intersecting: Place, Sex and Race

Related Papers

Hanneke Stuit

Martha Evans

Svend Erik Larsen

Isak Dinesen's Out of Africa (1937) is an autobiographical novel-like narrative about life in colonial Kenya, set on her coffee plantation near Nairobi from WWI to the early 1930s during the years of British jurisdiction. "Kitosch's Story"¹ forms a short subsection of this narrative. It tells how a killing exposes a gap between British law in the European tradition and local custom law as well as a gap between the two continents concerning such issues as explicit and implicit conceptions of law, the individual human being, culture and society, ethics, justice, punishment, verdict and retribution. The fatal killing renders the differences between two judiciaries clear for everybody, but not necessarily the mutual understanding of how and why the two systems are formed as they are, and how and why they work as they do. What is obvious, however, is the need to recognise the existence of this cultural disparity and to find ways to approach it, a need which, in Kitosch's case, has no resonance in either of the two cultures. Hence, the legal particularity of each system opens a cultural context much larger than the case itself and the problems of issuing a verdict that can be accepted in accordance with a particular sense of justice. However, neither of the systems is able to discuss its own limitations vis-à-vis its counterpart, which would require an imaginative capacity to view the law with the eyes of others through the lens of a sense of justice different from one's own. Such a capacity is not spurred by legal thinking. Instead, it is the task of a literary narrative to nurture the eye-opening comprehension of others and, not least, to be attentive to the limits of the respective legal systems. In the story, such an awareness is created with a criminal case and divergent legal practices as its plot, which leads to a demonstration of the open-ended ambiguity of law when squeezed between two cultures that are alien to each other yet co-exist in the same place. With legal issues as a filter, literature enables us to address the larger cultural question of encounters between cultures as well as the formal and informal value systems and the identity formations each of them underpins, particularly Karen Blixen and Isak Dinesen, Out of Africa (London: Penguin, 1985), 289-294.

Windsor YB Access Just.

Richard Weisman

Kazeem A Adebiyi-Adelabu

The truth and reconciliation project was a major political undertaking in South Africa that has continued to offer the country's creative writers a mine from which to draw materials and inspiration for thematic explorations. Critical responses to such creative works have equally been numerous, but they have placed more emphasis on inter-racial dimensions of rapprochement in their works. This paper critically examines the twin issues of truth and reconciliation in John Kani's Nothing but the Truth from inter-personal and intra-racial angles in order to demonstrate that inter-personal and intra-racial reconciliation, though not without challenges, provides a model of genuine and lasting national inter-racial reconciliation. Truth is depicted in different ways. The truth people tell in private and inter-personal conflicts appears more reliable, yet ambivalent because it is experiential. The one told in the public is depicted as unreliable, yet tolerable in the spirit of forging national unity. It is also depicted as desirable but sometimes painful. It is politicised. However, genuine truth is depicted as necessary to engendering lasting reconciliation while reconciliation itself is predicated on earned forgiveness.

Sandra Young

Rhetoric & Public Affairs

erik doxtader

Beyond the Rhetoric of Pain (eds. Nike Jung and Stella Bruzzi)

Derilene (Dee) Marco

Rianna Oelofsen

RELATED PAPERS

Natalia Riveros Anzola

Peace & Change: A Journal of Peace Research

Megan Shore

Ethics & International Affairs

Lyn Graybill

African Studies Quarterly

Roger Bromley

Nicola Mariani

In die Skriflig/In Luce Verbi

Robert Vosloo

48(3), 192-200.

Julia Sertel

Journal of Moral Education

Sharlene Swartz

Meg Samuelson

Sidonie Smith

Studia Historiae Ecclesiastiae

Eugene Baron

Dina Al-Kassim

Allard Duursma

Miłosława Stępień

Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy

Alexia Smit

South African Journal of Psychology

Everett Worthington , Richard Cowden

Cori Wielenga

Eduardus Van der Borght

Paul Muldoon

Nina K Thomas

Bonny Ibhawoh

George Wachira , Prisca Kamungi

Melbourne Journal of Politics

Evelyn Rose

Quincy Pule

Journal of Narrative Theory

Chielozona Eze

PUMLA GOBODO-MADIKIZELA

Helen Scanlon

Bethany Davis

Yianna Liatsos

Martin Terre Blanche

Claire Moon

Judith Renner

Alison James

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Introduction: The Culture of Ubuntu

- First Online: 01 January 2014

Cite this chapter

- Leonard Tumaini Chuwa 4

Part of the book series: Advancing Global Bioethics ((AGBIO,volume 1))

951 Accesses

1 Citations

Bioethics is a relatively new formal academic discipline. An increasing sense of the significance of Global Bioethics is emerging in which indigenous cultures are recognized as making valuable contributions to the general field of bioethics. The culture of Ubuntu is a representative example of an indigenous African ethics that can contribute to an emerging understanding of Global Bioethics. Ubuntu, which has existed for centuries, is a sub-Sahara African culture that refers to respectful treatment of all people as sharing, caring, and living in harmony with all creation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Murove (2004, p. 200).

Richards (1980, pp. 76–77).

Ten Have (2013, p. 601).

Ten Have (2013, pp. 603–604).

Ten Have (2013, p. 604).

Kelley Martin. Top 5 causes of world war I. http://americanhistory.about.com/od/worldwari/tp/causes-of-world-war-1.htm (Accessed 25 Sept 2013).

“World War Two—Causes.” http://www.historyonthenet.com/WW2/causes.htm (Accessed 25 Sept 2013).

“World War Two—Causes.” http://www.historyonthenet.com/WW2/causes.htm (Accessed 27 Sept 2013).

“History of the United Nations.” http://www.un.org/en/aboutun/history/ (Accessed 25 Sept 2013).

Briney (2011).

World Health Organization (2009).

Benatar (1998, pp. 295–300).

Ten Have (2013, p. 600).

Ten Have (2013, p. 608).

Ten Have (2013, p. 611).

World Health Organization (2010b, p. 3).

World Health Organization (2010b).

Wynberg et al. (2009).

Widdows (2009, p. 6).

Widdows (2009, pp. 10–16).

Ten Have (2013, p. 607).

Garrafa et al. (2010, pp. 500–501).

Garrafa et al. (2010, p. 501).

Mathew 7:12; Luke 6:31; Leviticus 19:18; Leviticus 19:34; Tobit 4:15; Sirach 31:15; Talmud, Shabbat 31a.

Asante (2008, p. 114).

Broodryk, Johann. 2002. Ubuntu. Life lessons from Africa, 26. Pretoria: Ubuntu School of Philosophy.

Louw (2007).

Mbiti, John S. 1969. African religions and philosophy, 16, 28. 2nd ed . New Hampshire: Heinemann Educational Books Inc.

Bujo (2001, p. 2). Bujo was citing Reese-Schaffer W. 1994. Was ist Kommunitarianismus? Frankfurt a. M./New York.

Bujo (2001, p. 2).

Bujo (2001, p. 3).

Holdstock (2000, pp. 162–181).

Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre. 1969. Human energy (Trans. J. M. Cohen), 113–162. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Metz (2011).

Some (1998, p. 38).

Broodryk (1997, p. 26).

Shutte (1993 p. 46).

Willie and Marwe (1996, pp. 1–3).

Willie and Marwe (1996, pp. 2–3).

Mbiti, John. 1970. African religions and philosophies, 141. New York: Anchor Books.

Bénézet (2001, p. 27).

Mbiti (1970, p. 141).

Gyekye, Kwame. 2002. Person and Community in African Thought. In Philosophy from Africa. A text with readings , ed. P. H. Coetzee and A. P. J. Roux, 319. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa.

Mbiti, John. 1969. African traditional religions and philosophy, 106.

Kasanene (1994, p. 140).

Mbiti (1970, p. 1).

Bujo (2001, p. 26).

Biko (2004, p. 46).

Menkiti (1984, pp.170–175).

Mbiti, John. 1970. African religions and philosophies , 1.

Mbiti, John. 1970. African religions and philosophies , 25.

Mbiti, John. 1970. African Religions and Philosophies , 22–28.

Bujo (2001, p. 89).

Mbiti, John. 1971. African traditional religions and philosophy, 13. London: Heinemann.

Mbiti, John. 1971. African traditional religions and philosophy, 13.

Bujo (2001, p. 37).

The word “magician” in this work means a person who uses evil forces to hurt or destroy life. This use is different from the western understanding of magic. Anything that disrupts life, unity or harmony is considered evil. Magic in this context is always evil as it is intentional causation of evil. Witch doctors and medicine men/women work against magicians and magic.

Bujo (2001, p. 7).

Bujo (2001, p. 6).

Bujo (2001, p. 6). The words in the brackets are mine.

Mbiti, John. 1969. African traditional religions and philosophy, 107.

Mbiti, John. 1969. African traditional religions and philosophy, 107–108.

Mbiti, John. 1969. African traditional religions and philosophy, 110.

Shutte, Augustine. 2001. Ubuntu: An ethic for the new South Africa, 30. Cape Town: Cluster Publications.

Bhengu (1996, p. 27).

Gbadegesin (1991, p. 65).

Metz and Gaie (2010, p. 275).

Metz and Gaie (2010, p. 283).

Justice Yvonne Mokgoro of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, The State versus T. Makwanyane and m Mchumu , para. 309. Cited by Metz (2007, p. 329).

Onah Godfrey. The meaning of peace in African traditional religion and culture. http://www.afrikaworld.net/afrel/goddionah.htm . (Accessed 4 Sept 2012).

Metz (2007, p. 330).

Tutu (1999, p. 35).

Bujo (1992, pp. 21–26).

Benhabib (1997, p. 73).

Taylor (1989, p. 111).

Taylor (1989, p. 112).

Taylor (1989, pp. 111–176).

See Reese-Schaffer, Was ist Kommunitarianismus? In Bujo (2001, p. 4).

Ratzinger, Joseph. 1968. Einfuhrung in das Christentum: Vorlesungen uber das Apostolische Glaubensbekenntnis (Munich),176. See Bujo (2001, p. 4).

Bujo (2001, p. 4). In this passage Bujo dwells on Franz von Baader’s criticism of Descartes. Joseph Ratzinger agrees with Baader’s line of argument and validates cognatus sum, ergo sumus (I am thought, therefore we are) against Descartes Cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore I am). Ratzinger argues that “it is only on the basis of his being known that the knowledge of the human person and his person himself can be understood,” In Einfuhrung in das Christentum , 177.

Bujo (2001, p. 5).

Ruch (1975, p. 2).

Bujo (1998, p. 123).

Bujo (1998, p. 182).

du Toit (1980, p. 23).

Peter Kasenene (1994, p. 142).

Bujo (2001, p. 97).

Bujo (2001, p. 123).

Mbombo (1996, p. 115).

Pal (2002, p. 519).

See Murove (2005, p. 153).

Okwu A. S. O. 1979. Life, death, reincarnation, and traditional healing in Africa. A Journal of Opinion 9 (Autumn, 1979) 19–23.

Mbombo (1996, p. 114).

Berg (2003, p. 200).