Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

African influences in modern art.

Reliquary: Standing Male Figure

Double Prestige Panel

Sculptural Bust from a Reliquary Ensemble (The Great Bieri)

Fang-Betsi artist

Seated Male Figure

Bell Mallet (Lawle)

Gertrude Stein

Pablo Picasso

Young Sailor II

Henri Matisse

Bust of a Man

Woman in an Armchair

Woman's Head

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude

Ventriloquist and Crier in the Moor

Bird in Space

Constantin Brancusi

Berlin Street

George Grosz

Comedians' Handbill

Goddess with Foliage

Wifredo Lam

Mother and Child

Elizabeth Catlett

The Beginning

Max Beckmann

Snow Flowers

Untitled [Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress]

Seydou Keïta

The Woodshed

Romare Bearden

Between Earth and Heaven

Denise Murrell Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University

During the early 1900s, the aesthetics of traditional African sculpture became a powerful influence among European artists who formed an avant-garde in the development of modern art. In France, Henri Matisse , Pablo Picasso , and their School of Paris friends blended the highly stylized treatment of the human figure in African sculptures with painting styles derived from the post-Impressionist works of Cézanne and Gauguin . The resulting pictorial flatness, vivid color palette, and fragmented Cubist shapes helped to define early modernism. While these artists knew nothing of the original meaning and function of the West and Central African sculptures they encountered, they instantly recognized the spiritual aspect of the composition and adapted these qualities to their own efforts to move beyond the naturalism that had defined Western art since the Renaissance.

German Expressionist painters such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner of Die Brücke (The Bridge) group, based in Dresden and Berlin, conflated African aesthetics with the emotional intensity of dissonant color tones and figural distortion, to depict the anxieties of modern life, while Paul Klee of the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) in Munich developed transcendent symbolic imagery. The Expressionists’ interest in non-Western art intensified after a 1910 Gauguin exhibition in Dresden, while modernist movements in Italy, England, and the United States initially engaged with African art through contacts with School of Paris artists.

These avant-garde artists, their dealers, and leading critics of the era were among the first Europeans to collect African sculptures for their aesthetic value. Starting in the 1870s, thousands of African sculptures arrived in Europe in the aftermath of colonial conquest and exploratory expeditions. They were placed on view in museums such as the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris, and its counterparts in cities including Berlin, Munich, and London. At the time, these objects were treated as artifacts of colonized cultures rather than as artworks, and held so little economic value that they were displayed in pawnshop windows and flea markets. While artworks from Oceania and the Americas also drew attention, especially during the 1930s Surrealist movement, the interest in non-Western art by many of the most influential early modernists and their followers centered on the sculpture of sub-Saharan Africa . For much of the twentieth century, this interest was often described as Primitivism, a term denoting a perspective on non-Western cultures that is now seen as problematic.

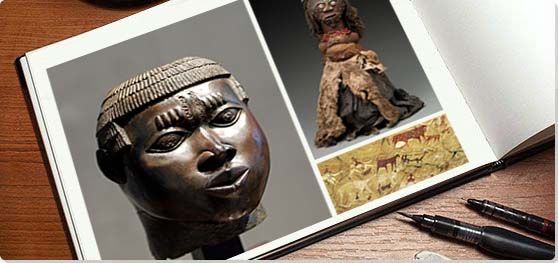

The Stylistic Influences of African Sculpture Modernist artists were drawn to African sculpture because of its sophisticated approach to the abstraction of the human figure, shown, for example, by a sculpted head from a Fang reliquary ensemble ( 1979.206.229 ), and a reliquary by a Mbete artist ( 2002.456.17 ). The provenance of the Fang work includes the collection of London-based sculptor Jacob Epstein, who had Vorticist associations and was a longtime friend of Picasso and Matisse; the Mbete reliquary was once owned by the pioneering Paris dealer Charles Ratton and then by Pierre Matisse, a son of the artist.

The Fang sculpture exemplifies the integration of form with function that had created a centuries-old tradition of abstraction in African art before the European colonial period. Affixed at the top of a bark vessel where remains of the most important individuals of an extended family were preserved, the sculptural element can be considered as the embodiment of the ancestor’s spirit. The representational style is therefore abstract rather than naturalistic. The abstract form of the Mbete piece goes even further to serve its function. Because the figure is the actual receptacle for the ancestral relics, the torso is elongated, hollow, and accessible from an opening in the back. The exaggerated flatness of the face in these reliquaries, and its lack of affect, typify elements of African aesthetics that were frequently evoked in modernist painting and sculpture.

Matisse, Picasso, and the School of Paris Matisse, an inveterate museum browser, had likely encountered African sculptures at the Trocadéro museum with fellow Fauve painter Maurice de Vlaminck, before embarking on a spring 1906 trip to North Africa. Upon returning that summer, Matisse painted two versions of The Young Sailor ( 1999.363.41 ) in which he replaced the first version’s naturalistically contoured facial features with a more rigidly abstract visage reminiscent of a mask. At about the same time, Picasso completed his portrait of the American expatriate writer Gertrude Stein ( 47.106 ), finalizing her face after many repaintings in the frozen, masklike style of archaic sculptural busts from his native Iberia.

In The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1913), Stein wrote an account of Matisse’s fall 1906 purchase of a small African sculpture, now identified as a Vili figure from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, at a curio shop on his way to visit her home. Since Picasso was present, she recalled, Matisse showed the sculpture to him. Picasso later told curators and writers of the pivotal visits he subsequently made, beginning in June 1907, to the African collections at the Trocadéro, famously describing his revulsion at the dimly lit, musty galleries but also his inability to turn away from his study of the objects’ inventive and elegant figural composition. The African sculptures, he said, had helped him to understand his purpose as a painter, which was not to entertain with decorative images, but to mediate between perceived reality and the creativity of the human mind—to be freed, or “exorcised,” from fear of the unknown by giving form to it. In 1907, after hundreds of preparatory sketches, Picasso completed the seminal Les Demoiselles d’Avignon , the painting to whose faceted female bodies and masklike faces some attribute the birth of Cubism and a defining role in the course of modern art throughout the twentieth century. He continued to make major paintings, sculptures, and sketches of mask-faced figures composed of fragmented geometric volumes throughout the Cubist period, including Bust of a Man ( 1996.403.5 ), from 1908, Head of a Woman ( 1996.403.6 ), from 1909, and the 1909–10 Woman in an Armchair ( 1997.149.7 ).

A younger member of the School of Paris, painter and sculptor Amedeo Modigliani, was a key contact between the School of Paris and the Futurist artists based in his native Italy. He was singular in his adaptation of stylistic influences primarily from the Baule of the Ivory Coast ( 1978.412.425 ). Modigliani made sketches of the elongated faces of Baule masks and figures, heart-shaped and narrowing to a point at the chin beneath a small mouth placed unnaturally low on the face. He later adapted this distinctive facial style in a series of sculptures including the 1912 Woman’s Head ( 1997.149.10 ); and later retained it in paintings such as the 1917 Reclining Nude ( 1997.149.9 ). Constantin Brancusi, Modigliani’s friend and Montparnasse studio neighbor, embraced African art because it, like sculpture of his native Romania, was directly carved from wood. Having trained with Rodin , one of Europe’s most prominent sculptors, Brancusi at times rejected the master’s bronze casting technique due to its expense and its remove from the direct hand of the artist, in favor of carvings from wood and, as in Bird in Space ( 1996.403.7ab ), from marble.

Modernism in America Matisse and Picasso were key figures in the spread of interest in African-influenced modernism among the avant-garde in the United States . In 1905, the American artist Max Weber moved to Paris and studied painting with Matisse. By 1908, Weber, a frequent guest at the Sunday evening salons hosted by Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo, had visited Picasso in his studio, where he may have viewed Picasso’s extensive collection of African art. After returning to the United States, Weber wrote to photographer Alfred Stieglitz about the African influences that he had observed in the work of Picasso and other Paris-based modernists; and Weber’s own paintings featured mask forms rendered in an increasingly abstract style. Stieglitz later presented the first Picasso exhibition in the United States at his small gallery, named “291” for its Fifth Avenue address, and then worked with Mexican artist Marius de Zayas on a 1914 exhibition that was among the first in the United States to present African sculpture as art. A 1923 exhibit at the Whitney Studio Club, a precursor of the Whitney Museum in New York, was among the earliest to present Picasso’s paintings together with African sculptures.

German Expressionism Artists in Germany between the world wars worked extensively with African compositional devices as they rejected naturalism as inadequate to their project of representing the anxiety, dislocation, and utopian fantasies of interwar German society. Paul Klee developed a distinctively individual abstract style while teaching at the Bauhaus . Mystical connotations are evoked, in paintings like his 1923 Ventriloquist and Crier in the Moor ( 1984.315.35 ) and the 1938 Comedians’ Handbill ( 1984.315.57 ), by massed signlike forms. Some scholars have suggested affinities between these works and masks of the Bwa culture of Burkina Faso and geometrically patterned fabrics from the Bambara of Mali .

Ex-Dadaist George Grosz masks the melancholy figures crowding his 1931 Berlin Street ( 63.220 ) in a more generalized style, which became influential for his students after he emigrated to New York, where he taught at the Art Students League. Max Beckmann overlays memory, nightmare, and dream in his allegorical 1949 triptych Beginning ( 67.187.53a–c ), completed after he, too, relocated to the United States.

The Mature Work of Matisse and Picasso The work of Picasso and Matisse continued to reflect the influence of African aesthetics well into the mid-twentieth century, and important aspects of this later influence have been disclosed by recent scholarship. Some of Picasso’s most significant early sculptural works, and his monumental 1930s busts of his young mistress Marie-Thérèse, have been linked, respectively, to Grebo and Nimba masks in his collection of African sculpture. Matisse, whose family had been weavers for generations, owned several Kuba cloths ( 1999.522.15 ) from Central Africa, as well as opulent fabrics from North Africa and eastern Europe.

Kuba cloths had been shown in early African art shows in Paris that Matisse may have attended, and several remained in his collection at his death. These handcrafted nineteenth-century fabrics from the Democratic Republic of the Congo were woven from raffia palm fibers and used in dowries; the larger ones served as festive attire at funerals. Matisse’s correspondence indicates their inspiration for the paper cutouts, such as the 1951 Snow Flowers ( 1999.363.46 ), that were his final major works. These collages blend Matisse’s vivid color palette with the allover patterning of the textiles to produce abstract floral forms free-floating in space, creating perspectival shifts between foreground and background. After hanging panels of the Kuba textiles across his studio walls, Matisse wrote in letters to his sister that he often looked at them for long periods, waiting for something to come to him.

Legacy for Postwar and Contemporary Art By the early twentieth century, African American modernists had joined other American artists in exploring the formal qualities of African art. In 1925, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, black philosopher Alain Locke argued that African American artists should look to African art as a source of inspiration. A variety of influences informs the work of artists such as Elizabeth Catlett ( 1999.529.34 ) and Romare Bearden , who came of age in the aftermath of this important period in black cultural history. Bearden studied under George Grosz in New York; in The Woodshed ( 1970.19 ), from 1969, he composed Dadaist-inflected collages from materials including fragmented photographs of African sculpture. This method was elaborated in The Block ( 1978.61.1–.6 ), an epic-scale celebration of everyday life in a Harlem neighborhood.

The Afro-Cuban artist Wifredo Lam, who was closely involved with the Surrealists in Paris, and whose dealer was Pierre Matisse, painted hybrid figures, such as in the 1942 Goddess with Foliage ( 2002.456.32 ), blending an uncanny Surrealist sensibility with African figural styles and references to spirituality. Several members of the postwar Abstract Expressionists , including the sculptor David Smith and the painter Adolph Gottlieb, were known to have viewed and collected African sculpture as their abstract styles evolved.

In the contemporary postcolonial era, the influence of traditional African aesthetics and processes is so profoundly embedded in artistic practice that it is only rarely evoked as such. The increasing globalization of the art world, which now includes contemporary African artists such as Malian photographer Seydou Keïta ( 1997.364 ) and Ghana-born sculptor El Anatsui ( 2007.96 ), renders increasingly moot any term that assumes a distinct divide between Western and non-Western art. The Primitivist worldview is being relegated to the past. It is in efforts to understand the full spectrum of the aesthetic foundations for early modernism that an investigation of African influences in modern art remains relevant today.

Murrell, Denise. “African Influences in Modern Art.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/aima/hd_aima.htm (April 2008)

Further Reading

FitzGerald, Michael. Picasso and American Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

LaGamma, Alisa, ed. Eternal Ancestors: The Art of the Central African Reliquary. Exhibition catalogue. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007. See on MetPublications

Messinger, Lisa Mintz, Lisa Gail Collins, and Rachel Mustalish. African-American Artists, 1929–1945. Exhibition catalogue. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003. See on MetPublications

Matisse, His Art and His Textiles: The Fabric of Dreams. Exhibition catalogue. London: Royal Academy of Arts,, 2004.

Rewald, Sabine. Twentieth Century Modern Masters: The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection . Exhibition catalogue. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989. See on MetPublications

Rubin, William, ed. "Primitivism" in 20th Century Art . 2 vols. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1984.

Vogel, Susan M. Primitivism Revisited: After the End of an Idea . New York: Sean Kelly Gallery, 2007.

Related Essays

- Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

- Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

- Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

- Antelopes and Queens: Bambara Sculpture from the Western Sudan : A Groundbreaking Exhibition at the Museum of Primitive Art, New York, 1960

- Senufo Sculpture from West Africa : An Influential Exhibition at the Museum of Primitive Art, New York, 1963

- Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

- Ethiopia’s Enduring Cultural Heritage

- Europe and the Age of Exploration

- Exchange of Art and Ideas: The Benin, Owo, and Ijebu Kingdoms

- Fernand Léger (1881–1955)

- Kingdoms of the Savanna: The Kuba Kingdom

- Kingdoms of the Savanna: The Luba and Lunda Empires

- Kongo Ivories

- Modern Art in West Asia: Colonial to Post-colonial

- Modern Storytellers: Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold

- Monumental Architecture of the Aksumite Empire

- Nineteenth-Century European Textile Production

- Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

- Paul Poiret (1879–1944)

- Portraits of African Leadership

- Trade Relations among European and African Nations

- Ways of Recording African History

- Women Leaders in African History, 17th–19th Century

- Central Africa, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Central Africa, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Central Africa, 1900 A.D.–present

- Eastern Africa, 1600–1800 A.D.

- France, 1800–1900 A.D.

- France, 1900 A.D.–present

- Guinea Coast, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1900 A.D.–present

- Southern Europe, 1800–1900 A.D.

- 20th Century A.D.

- Abstract Art

- Abstract Expressionism

- Biblical Scene

- Der Blaue Reiter

- Expressionism

- Floral Motif

- Funerary Art

- Gelatin Silver Print

- Geometric Abstraction

- Iberian Peninsula

- Literature / Poetry

- Modern and Contemporary Art

- Oil on Canvas

- Photography

- Primitivism

- Religious Art

- School of Paris

- United States

- Western Africa

- Women Artists

Artist or Maker

- Anatsui, El

- Bearden, Romare

- Beckmann, Max

- Brancusi, Constantin

- Catlett, Elizabeth

- Cézanne, Paul

- De Vlaminck, Maurice

- Gauguin, Paul

- Grosz, George

- Keita, Seydou

- Lam, Wifredo

- Matisse, Henri

- Modigliani, Amedeo

- Nxgongo, Beauty

- Picasso, Pablo

- Smith, David

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Prime of Life” by Alisa LaGamma

- The Artist Project: “Glenn Ligon on The Great Bieri “

- The Artist Project: “Mickalene Thomas on Seydou Keïta”

- Connections: “Africa” by Alisa LaGamma

- Connections: “Black” by Aimee Dixon

Advertisement

2022 Impact Factor: 0.3 2023 Google Scholar h5-index: 8 ISSN: 0001-9933 E-ISSN: 1937-2108

African Arts presents original research and critical discourse on traditional, contemporary, and popular African arts and expressive cultures. Since 1967, the journal has reflected the dynamism and diversity of several fields of study, publishing richly illustrated articles in full color, incorporating the most current theory, practice, and intercultural dialogue. The journal offers readers peer-reviewed scholarly articles concerning a striking range of art forms and visual cultures of the world’s second-largest continent and its diasporas, as well as special thematic issues, book and exhibition reviews, features on museum collections, exhibition previews, artist portfolios, photo essays, contemporary dialogues, and editorials. Looking for older African Arts issues? Volumes 1 - 39 are available here on JSTOR Latest Most Read Most Cited Erratum: Gosette Lubondo: Imaginary Trip An Ancient Terracotta Figure from Sierra Leone Pragmatism in Yoruba Art: Dada Areogun's Narrative Woodcarving as Cultural Stewardship Panoramas from the Periphery: Women's History Tapestries at Rorke's Drift Contemporary Mythos of Spirits and Genies: A Conversation with Ibrahima Thiam Editorial Consortium

UCLA : Marla C. Berns, Carlee S. Forbes, Silvia Forni, Erica P. Jones, Peri Klemm

Miami University, Ohio: Jordan Fenton, Matthew Rarey, Joseph Underwood, Sarah Van Beurden, Kristen Windmuller-Luna

University of Florida : Álvaro Lúis Lima, Nomusa Makhubu, Fiona Mc Laughlin, Robin Poynor, MacKenzie Moon Ryan

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Lisa Homann, Priscilla Layne, Carol Magee, David G. Pier, Victoria L. Rovine

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1937-2108

- Print ISSN 0001-9933

A product of The MIT Press

Mit press direct.

- About MIT Press Direct

Information

- Accessibility

- For Authors

- For Customers

- For Librarians

- Direct to Open

- Open Access

- Media Inquiries

- Rights and Permissions

- For Advertisers

- About the MIT Press

- The MIT Press Reader

- MIT Press Blog

- Seasonal Catalogs

- MIT Press Home

- Give to the MIT Press

- Direct Service Desk

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Crossref Member

- COUNTER Member

- The MIT Press colophon is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Search Google Appliance

- Online Book Collections

- Online Books by Topic

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Library Catalog (SIRIS)

- Image Gallery

- Art & Artist Files

- Caldwell Lighting

- Trade Literature

- All Digital Collections

- Current Exhibitions

- Online Exhibitions

- Past Exhibitions

- Index of Library & Archival Exhibitions on the Web

- Research Tools and OneSearch

- E-journals, E-books, and Databases

- Smithsonian Research Online (SRO)

- Borrowing and Access Privileges

- Smithsonian Libraries and Archives on PRISM (SI staff)

- E-news Sign Up

- Internships and Fellowships

- Work with Us

- About the Libraries

- Library Locations

- Departments

- History of the Libraries

- Advisory Board

- Annual Reports

- Adopt-a-Book

- Ways to Give

- Gifts-in-Kind

You are here

African art research guide, african archaeology and rock art, african art at the smithsonian, african art exhibitions, african art galleries, african art history, african art journals, african artists, african artists: south african artists, african currency, african posters, african textiles, cultural property in africa.

- Modern African Art: A Basic Reading List

Museums with African Art Collections

Welcome to the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives' African Art Research Guide. This is a select list of freely-available resources for students, teachers, and researchers to learn about African art. Please feel free to Contact Us with suggestions for additional resources or with questions.

- Egyptian Art and Archaeology (University of Memphis)

- Trust for African Rock Art (TARA)

- National Museum of African Art

- Smithsonian's African Art Library catalog

- “African Voices” at the National Museum of Natural History

- Africa: The Art of a Continent (1996)

- African Art: Aesthetics and Meaning (University of Virginia)

- African Connections: Perspectives on Collecting Culture (Michigan State University)

- Contemporary African Art Gallery, New York

- October Gallery, London

- African Visual Arts (Stanford University)

- Art and Life in Africa (University of Iowa project)

- African arts

- Revue noire

- African Crafts and Artisans

- AfricArt: Inventaire des Artistes Plasticiens Africains

- Harmon Foundation Contemporary African Art Collection (U.S. National Archives and Record Administration)

- Artslink: the South African Arts & Culture Hub

- Artthrob's "Contemporary Art in South Africa"

- African Currency: John B. Henry’s African metal currency collection

- African Posters (Northwestern University)

- Kate Kent collection of West African textiles (Denver Art Museum)

- ICOM’s Red List Database of Looted Antiquities

- British Museum

- Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

- Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale, Tervuren, Belgium

- Museums in the United States with Collections of African Art

- Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford

Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Culture, Design and Social Development (CDSD 2023)

Identity and Expression: The Influence of African Art on Modern Western Artists

This paper explores the profound and enduring influence of African art on modern Western artists. It traces the lineage of inspiration from African art to Western art and examines how the aesthetics, motifs, and philosophical underpinnings of African art have permeated Western art movements, with a particular focus on the 20th century. Through an in-depth analysis of key artists, artworks, and movements, this research uncovers the transformative impact of African art on Western creativity.

From the Cubist fascination with African masks to the Abstract Expressionists’ engagement with African aesthetics, this study elucidates the ways in which African art has enriched and challenged Western artistic traditions. It highlights the cross-cultural dialogue that has shaped the evolution of art, fostering a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of global artistic expressions. Ultimately, this research underscores the universal language of art and the enduring legacy of African art in the fabric of Western artistic innovation.

Download article (PDF)

Cite this article

African Women in African Arts: Making Art for Change

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 04 May 2021

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Adérónké Adésolá Adésànyà 3

51 Accesses

This essay about African women artists discusses the works of some women artists drawn from different regions of the continent whose trajectories place them within the framework of change agents, influencers, and institutional builders. Their works transcend art for art’s sake. This category of artists deserve mention not just because there is a dearth of literature on women artists even though their numbers have significantly increased over the decades, and there is a need to fill the lacuna. Beyond engendering studies on African art, the works of women artists need to be put on the front burner for several other reasons: the critical interventions they make – whether at economic or political level, the awareness they generate for individual, group, gender security and integrity, creating avenues to support professional or life transformations, and the ways they continue to influence societies towards rethinking local and global issues.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Adesanya, A. (2014). Interview with Nike Okundaye-Davies . Lekki: Nike Art Gallery.

Google Scholar

Alatishe, P. (2013). All scarves go to heaven (cloth on canvas), 115 cm × 216 cm. Retrieved from https://theartstack.com/artist/peju-alatise/all-scarves-go-heaven?product_referrer_user_id=429633467 . Accessed 12 Jan 2015.

Alexander, J. (2015). Quote. Retrieved from https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/jane-alexander-18870/who-is-jane-alexander . Accessed 13 Aug 2019.

Allsop, L. (2012). Looping the loop: Amina Menia in conversation with Laura Allsop. IBRAAZ. Retrieved from https://www.ibraaz.org/interviews/42/15

Berger, M. (2018). Zanele Muholi: Paying homage to the history of black women. The New York Times . Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/03/lens/zanele-muholi-somnyama-ngonyama-south-africa.html

Bick, T. (2010). Horror histories: Apartheid and the abject body in the work of Jane Alexander. African Arts, 43 , 30–41.

Boram-Hays, C. (2017). Afi Ekong: Laying the foundation for Nigerian women artists. In C. Bosah (Ed.), The art of Nigerian women (pp. 240–243). New Albany: Ben Bosah Books.

Bosah, C. (2017). The art of Nigerian women . New Albany: Ben Bosah Books.

Darwent, C. (2009). Unveiled: New art from the Middle East, Saatchi Gallery. London Independent . Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/reviews/unveiled-new-art-from-the-middle-east-saatchi-gallery-london-1522227.html

Dent, L. (2012). Global context: Q+A with Jane Alexander, art in America. Retrieved from https://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/interviews/jane-alexander-cam-houston/ . Accessed 20 Aug 2019.

Farjam, L., & The Saatchi Gallery. (2009). Unveiled: New art from the Middle East . London: Booth-Clibborn.

Gevisser, M. (2019). Zenele Muholi: Dark lioness. The Economist . Retrieved from https://www.1843magazine.com/culture/zanele-muholi-dark-lioness

Guggenheim.com. (2019). Zanele Muholi. Retrieved from https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/zanele-muholi

Hanna, W. (2014). Who is actually guilty of more than 60 years of Palestinian genocide?. Countercurrents . Retrieved from http://www.countercurrents.org/hanna110814.htm

International Center of Photography (nd.). Zanele Muholi (biography). Retrieved from https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/constituents/zanele-muholi?all/all/all/all/0 , https://www.artsy.net/artist/zanele-muholi

Jirsa, T. (2016). Portrait of absence: The aisthetic mediality of empty chairs (trans: Chocholova, T. (Czech)). Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/30138665/Portrait_of_Absence_The_Aisthetic_Mediality_of_Empty_Chairs?auto=download

Krauss, R. (1986). Notes on the index, part 2. In The originality of the avant-garde and other modernist myths . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mbah, F. (2019). Nigeria’s Chibok schoolgirls, five years on, 112 still missing. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/04/nigeria-chibok-school-girls-years-112-missing-190413192517739.html

Mercer, K. (2014). Postcolonial grotesque. Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, 33 , 80–90.

Nochlin, L. (1988). Women, art, and power. In Women, art, and power and other essays . New York: Harper and Row.

Okediji, M. (2017). She quelled the storm: Dissident aesthetics in Nigerian women’s art. In C. Ben-Bosah (Ed.), The art of Nigerian women (pp. 28–45). New Albany: Ben Bosah Books.

Packalén, L. (2009). Tanzania comic art: Vibrant and plentiful. In J. A. Lent (Ed.), Cartooning in Africa (pp. 307–322). Cresskill: Hampton Press.

Shabout, N. (2009). Contemporaneity and the Arab World. In H. Amirsadeghi et al., (Eds.) New Vision: Arab Contemporary Art in the 21st Century. Thames and Hudson, London.

Soyinka, W. (2014). Hatched from the egg of impunity: A fowl called Boko Haram. Excerpt from a lecture the Nobel Laureate delivered at the Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bT5_k9bnpF4 . Published 8 Nov 2014. Accessed 10 Feb 2016.

Strochlic, N. (2020). Chibok schoolgirls. The abduction of 276 Nigerian schoolgirls outraged the world. 112 are still missing. The survivors are reclaiming their lives. National Geographic , pp. 84–97.

Yanceyrichardson.com. (2019). Zanele Muholi. Retrieved from http://www.yanceyrichardson.com/artists/zanele-muholi

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA, USA

Adérónké Adésolá Adésànyà

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Adérónké Adésolá Adésànyà .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Babcock University, Ilishan Remo, Nigeria

Olajumoke Yacob-Haliso

Department of History, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA

Toyin Falola

Section Editor information

Women’s Research and Documentation Center (WORDOC), Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

Sharon Adetutu Omotoso

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 This is a U.S. Government work and not under copyright protection in the U.S.; foreign copyright protection may apply

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Adésànyà, A.A. (2020). African Women in African Arts: Making Art for Change. In: Yacob-Haliso, O., Falola, T. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of African Women's Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77030-7_46-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77030-7_46-1

Received : 28 March 2020

Accepted : 13 April 2020

Published : 04 May 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-77030-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-77030-7

eBook Packages : Springer Reference History Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Independent Curators Bridging African with the Global Art market

Nigerian-British Artist, Olaolu Slawn, Styles the Look of the 2024 FA Cup Trophy

John Randle Centre: Lagos' New Museum Makes Yoruba Culture Come Alive

"A Slow Succession with Many Interruptions" - Group Exhibition at Goodman Gallery

For years, curators of African decent have been the quiet force behind the intentional foundations of the African Art market. From...

CURRENTLY ON VIEW

In Conversation: Oliver Enwonwu's 'A Continued legacy' bridges generations and reclaims narratives

I had the pleasure of speaking with Visual Artist, Oliver Enwonwu on the powerful message behind his new body of work. Highlighting...

The Now Evening Auction At Sotheby's Sets New Auction Records

Rare Basquiat Works From Pellizzi Collection Up for Auction at Phillips

Jadé Fadojutimi Sets New World Record at Christie’s 20th/21st Century London Evening Sales

1-54 Marrakech – Galleries Announcement

MARKET REPORTS

SIGN UP TO GET OUR LATEST REPORT

Thanks for subscribing!

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

National Museum of African Art - Smithsonian Institution

The strength of the museum’s collection, which is the foundation of its programs and the primary vehicle through which the museum carries out its mission, lies in its unmatched depth and diversity. It is a collection that embraces all of the artistic expressions of Africa’s artists, from antiquity to the current moment.

The museum is also home to a state-of-the-art conservation lab , an unparalleled photographic archives , and the world’s leading library for the history of Africa’s arts.

Permanent Collection Facts

The permanent collection cared for by the museum includes more than 12,000 works of art and contains a broad range of works from throughout the continent of Africa and its diaspora, in all media across time periods and geographic origin. Collection strengths include, but are not limited to, sculpture, particularly masks and figures; paintings and works on paper; textiles, costumes, and jewelry; furniture and decorative objects; and architectural elements. With more than 10% of the collection consisting of works from the 20th and 21st centuries, the museum houses the largest and one of the oldest publicly held collections of 20th- and 21st-century African art. In addition, through the efforts of its ongoing Women’s Initiative , over 20% of the known and named artists represented in the collection identify as women—a percentage the museum actively seeks to increase.

The Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives holds over 550,000 photographs, archival materials, and digital media, and the Warren M. Robbins Library has well over 65,000 books and journals in its collection.

Provenance at the National Museum of African Art

Learn more about the museum’s work in researching collection provenance —and contribute tips in its efforts.

Shared Stewardship and Ethical Returns

The museum is committed to transparent and sincere engagement with source communities on shared stewardship and ethical returns of collection. Learn more here .

Browse the Art Collection

Eliot elisofon photographic archives, warren m. robbins library, conservation department.

Browse the Photographic Collection

Guidelines for artwork donations, requests for loans from the collection, search this site, location, hours, and admission, radio africa (a collaboration with smithsonian folkways), connect with us, artwork credits.

thanks a lot

You are now a Member of the National Museum of African Art. Thank you for supporting what we do! You can increase your giving at any point to gain increased access to the museum. Email [email protected] with any questions. Thank you!

Traditional African Art

Summary of Traditional African Art

The histories and lineages of African art are as diverse as the communities and cultures that traverse the continent. From the ornate cave paintings of South Africa's Cederberg Mountains to the abstract masks of myriad regional traditions, African art incorporates an extraordinary array of objects, materials, media, and themes. One striking aspect of African painting, pottery, and sculpture to Western viewers might be its marked difference from historical works produced in the European Renaissance tradition, with their emphasis on vanishing-point perspective and a form of naturalistic representation. Equally, traditional African art should be explored on its own termsand for the themes and motifs that unite much of it: for example, the production of objects and costumes for religious and ritual purposes.

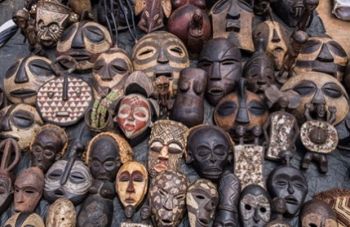

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Amongst the best-known examples of traditional African art are the striking masks produced by many cultures across the continent: from the Zamble masks of the Guro culture (located in present-day Ivory Coast), to Yoruba, Lulua, and Goma facial adornments - created by communities in Nigeria, Congo, and Tanzania. These masks often had a precise religious or ritual function, seen to take on magical properties in the context of a particular rite or event. They also had an incalculable impact on the development of modern art in Europe during the early 20 th century, with Cubists such as Pablo Picasso deeply moved and influenced by their animated abstraction.

- Traditional African art shares marked characteristics, in spite of its geographical differences. For example, many African sculptures are united by their intended function as talismans or vessels for communicating with the dead ancestors during religious events. As such, many works remind us of the close relationship between art and spirituality throughout human history; the fact that centuries-old traditions have survived in many African cultures gives us a vital window on the origins of human creativity.

- Pottery is a key form for many African artistic cultures. Jugs and vessels were often created with a utilitarian or domestic function in mind, yet also with great attention to visual beauty and detail. The case of African pottery indicates the less rigorous boundary placed between fine art and practical craftsmanship than in the Western tradition. In fact, this approach mirrored twentieth-century Western movements such as Constructivism , again indicating the ways in which traditional African art predicts and preempts Western equivalents.

- African art cannot be considered today apart from the controversies concerning its location in museums and galleries across the West. Works such as the Benin Bronzes - which the Nigerian government has repeatedly petitioned to have returned - were plundered by colonial empires and often sold on, hence their dispersal across Europe and North America. They therefore stand as markers of a global debate concerning the need for compensation and reparation following the violent subjugation of African societies by European states.

Overview of Traditional African Art

The traditions of African art are rich in their variety of objects, materials, and media, including sculpture, pottery, metalwork, painting, and textiles. While artworks differ depending on geographical area, historically African art has shared some underlying characteristics - including the fact that, unlike in the Western world, objects are often created for religious, ritual, or practical functions.

Artworks and Artists of Traditional African Art

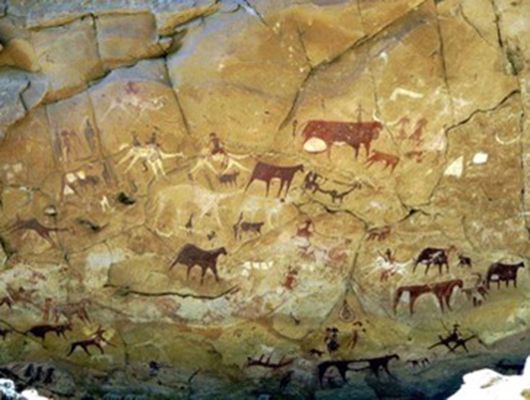

Untitled rock painting

Chad's Manda Guéli Cave is home to an array of painted figures and animals, including cattle and camels. This diversity of forms highlights an interesting feature of African rock art. Unlike in Europe, where cave paintings were not created beyond prehistoric times, many African cultures continued to produce this style of painting well after humans had settled in agricultural communities. Because of this, works like the above can be divided into four distinct categories, identifiable by the types of animals depicted. Early paintings tend to include wild animals such as bison and elephants, with later phases incorporating first cattle, then horses, and finally camels. The depiction of camels in this work places it in the last category of cave paintings, helping archaeologists to date the work. The presence of human figures interacting with animals, meanwhile, confirms this piece as a product of a period of domestication, well after the earliest, hunter-gatherer phase of human development had ended. Again, this suggests that this is a later cave painting. At the same time, the work also seems to serve as an abstract visual diary, or a series of time-stamps stretching across centuries. The fact that camels are depicted alongside, and sometimes seem to be transposed on top of cattle, supports the ideas that in many African caves paintings were not created during single phases of history. Rather, later groups of artists would have added to existing paintings with their own images, creating a remarkable graphic record of the passage of time and human development: indeed, works of African cave art provide a unique and captivating insight into past cultures in a way few other works of human creativity can match.

Pigment on Rock - Manda Guéli Cave, Ennedi Mountains, Chad, Central Africa

Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba

This artwork is one of a pair of African ivory masks featuring the face of a woman from the African country of Benin. Exquisitely detailed, these are arguably the most important historical works of the Edo people. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art notes, "although images of women are rare in Benin's courtly tradition, these two works have come to symbolize the legacy of a dynasty that continues to the present day. The pendant mask is believed to have been produced for...the king of Benin, to honor his mother, Idia. The oba [or king] may have worn it at rites commemorating his mother, although today such pendants are worn at annual ceremonies of spiritual renewal and purification." The details of this sculptural work are highly significant to its symbolic and communal meaning. First, the impression of scarification or tattooing on the face reflects a rite common amongst the Benin people - although the distinct facial features would have been based on the appearance of the individual, regal subject. However it is the headdress and collar that are perhaps the most interesting, as they tell a story of foreign influence. The Metropolitan Museum notes the presence of "carved stylized mudfish and the bearded faces of Portuguese [sailors]. Because they live on land and in the water mudfish represent the king's dual nature as human and divine. Having come from across the seas, the Portuguese were considered denizens of the spirit realm who brought wealth and power to the oba." Features like those described show the power of much historical African art to make visual statements about influences on a particular culture or community. This can be compared to the densely allusive references that populate religious paintings of the European Renaissance, for example. At the same time, the ceremonial function of artworks like the above mark them out from the purely ornamental and symbolic value of most Western works from the same era. For this reason, traditional African art provides an alternative rubric for thinking about the very essence and purpose of art, and is of the utmost importance to all who want a better understanding of the subject at a global level.

Ivory, iron, copper - Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Military Leader

This small relief plaque, measuring little more than a foot high and a foot wide, features a warrior dressed in full armor with spear in one hand and shield in the other. His direct and intense frontal gaze is barely visible under his large helmet, fastened with a chin strap. The background is notably replete with detail, including finely inscribed lines in the shape of large three-petaled flowers, or perhaps leaves. This work is one of thousands of plaques known as the Benin Bronzes, carved in brass by artists from the Benin Kingdom - part of modern-day Nigeria - several centuries ago. These pieces show the role that art can play in communicating a political statement or as a vehicle for propaganda. The Benin people were known for their military might and relief sculptures like this were used to reinforce the impression of this power to friend and foe by depicting warriors and leading military figures alongside the king, his family, and his attendants. While they should be treasured for their aesthetic and historical value, the Benin Bronzes also speak to a very modern predicament. According to the Ethnologisches Museum itself, these "historical 'bronzes' and ivory objects from Benin are seen as symbols of colonial collecting and their presence outside Nigeria is widely understood as a sign of colonial injustice." During the 19 th century, British troops attacked Benin, bringing the kingdom under colonial rule and looting much of its artwork, including these plaques. The Benin Bronzes were amongst the array of artefacts brought back to England, from where many were sold, ending up in private collections and museums around the world. The present-day Nigerian government, alongside innumerable activists, artists, and citizens, are pressing for these treasures to be returned to their native region.

Brass - Collection of Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin, Germany

Female Figure

This wooden sculpture depicts a female with an elongated neck, a frontal gaze, and arms bent at 90 degree angles resting formally at her side. A good deal of fine detail is evident in this work, including around her sandaled feet and the marks on her chest and shoulders.This statue was produced by an artist who belonged to the Bena Lulua people in present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo. The figurative sculptural tradition of this region is diverse in that it features both women and men and distinguishes between citizens, rulers, and warriors. However, all Lulua sculptures tend to bear several important features in common, allowing them to be identified clearly as products of their time, place, and culture. As African art expert Frank Willett notes, "the figurines of the Bena Lulua are highly distinctive. They show elaborate scarifications and usually have the navel emphasized presumably because it represents the physical link to the ancestors." Such geographical distinctions between artworks, especially with regards to the representation of the human body, indicate the breadth and complexity of historical traditions within African art. This disproves the outmoded idea that African artistic traditions are in any sense uniform or unsophisticated. It is also worth noting the similarities between the formal distortions of the Bena Lulua figurines and the work of modern European artists known for elongated depictions of the human form, such as Alberto Giacometti and Amedeo Modigliani. This is one of analogies that can be drawn between traditional African art and modern Western art, and another indication of the great significance of historical African art.

Wood with traces of tukula pigment - Collection of Honolulu Museum of Art, Honolulu, Hawaii

Zamble Helmet Crest Mask

This mask is typical of the style of the Guro culture of the Ivory Coast. With its elongated nose and large eyes, its other key distinguishing feature are the striped horns protruding from its forehead. The Guro people shape this type of mask to resemble a mythical creature called the Zamble which, according to African art expert Frank Willett, is "a mysterious being which resembles a beautiful, strong, young man. These qualities are reflected by its form - the beauty of the antelope and the strong teeth of the leopard together with the youthful rapidity of its dance steps." With its strong association with death, this mask indicates the importance of the spiritual world to the Guro people. According to the Art Institute of Chicago, Zamble masks would be worn "on the occasion of a man's second funeral, which would be organized months or years after the actual burial to commemorate the accomplishments of the deceased. Performances took the form of competitions between mask dancers from two different families." Works such as this mask show the vital role that much African art plays in ceremonies and religious events. The significance of masks generally extends far beyond that of a prop or performance aid. Instead, they are vital component of the ritual and often endowed with magical powers. In more recent years, masks such as these have been influential on pop culture in the West, and particularly African-American pop culture, influencing the aesthetics of the Marvel film The Black Panther , for example.

Wood and pigment - Collection of Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

A functional piece of pottery, this work shows how African art often combined practical use with artistic design. Most likely used to hold wine, the vessel has also been fashioned to depict the body shape and head of a female, complete with ornate necklace and distinct hairstyle. The elongated facial features are particularly distinctive, indicating the cultural and geographical specificity of the object. This work is from the Mangbetu culture located in the present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo and provides a good example of the way figures are depicted in the tradition of that community. As historian of African art Frank Willett explains, "the deformation of the head reflects the...practice of binding their babies' heads to make them long and beautiful." Amongst the Mangbetu, art is created by both genders. However, according to the Cleveland Museum of Art, "women were and still are responsible for the making of terracotta pots....It seems, however, that men added the figurative elements". This pot is believed to have had a utilitarian function. As author Victoria Rovine explains, it would have been "displayed by Mangbetu leaders as they sat in state or used along with a straw to consume palm wine. Pots of this type were also used to hold a mixture of palm wine and a root called naando, consumed by dancers at ceremonial events to energize them and improve their performance." In the early-to-mid 20 th century, modern Western art movements such as Constructivism and Concrete Art collapsed the distinction between artistic and functional objects in the same way as some African craftspeople had been doing for centuries. This is another indication of the ways in which traditional African art predicts the evolution of Western art during the 20 th century.

Terracotta - Collection of Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland Ohio

African Songye Power Figure

Carved from wood, this figurative sculpture with distinct facial features is embellished with decorative elements including feathers, fur, and even reptile skin. The piece is typical of a type of large-scale sculptural objects known as a "power figure." Works like these had an important ritual function amongst the Songye communitues in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Power figures are also an interesting example of the spiritual and religious significance of much African sculpture. Intended to act as an intermediary between the spirits of dead ancestors and living members of the community, works like these would be commissioned for particular ritual events. Once carved, this item would have been covered with a sacred substance. According to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, such sculptures "derive their authority from the insertion and application of spiritually charged substances. The identity of these substances is secret to the ritual specialist who applies them and varies significantly. Some of the many documented substances include certain river clay, some herbs, ashes of burnt trees from a battleground and the flesh of someone who has [died by] suicide." Once used in the ritual, the sculptures would remain part of the community, belonging to no individual person. They would also be used in future rituals whenever the need arose to address, according to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, "communal concerns such as crop failure, widespread illness, or a territorial dispute with a neighboring village. The figure with its spiritual charge was considered a protective entity." As such, power figures provide a good example of art being used to help explain and abate the impact of environmental and social disasters through religious narrative. Works like these provide a vital window on the role of creativity in past centuries and millennia, therefore, and can be used to unravel riddles about the origins of art in many other parts of the world, which would likely also have been in protective magic of various kinds.

Wood, cloth, feathers, fur, reptile skin, metals, pigment - Collection of Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, Indiana

Pair of door panels and a lintel

Artist: Olowe of Ise

This elaborately detailed and painted pair of door panels is a masterpiece of relief-carved design. Depicting a narrative across five distinct bands, the panels contain both human figures and, in the background, ornate geometric patterns. This is the work of well-respected artist Olowe of Ise who received many important commissions during his lifetime, including from royalty. According to African art specialist Frank Willett Olowe is "probably the greatest Yoruba virtuoso sculptor. His figures lean out from the door, the upper part being carved fully in the round." The panel was commissioned to commemorate a historical event for the Yoruba - the arrival of the first British official to the area, Captain Ambrose. The importance of his arrival is indicated by the fact that he is being carried in a hammock to King Ogoga by a number of his attendants in the second-from-top right-hand panel. Directly across from him to the left, the king awaits the introduction seated on his throne, his wife stood behind him. The king is elaborately dressed and wears an ornate crown befitting royalty. Interestingly there is also a visual message depicted on the lintel above the panels. According to the British Museum this "shows human faces whose eyes are being pecked out by vultures, a common motif in Nigerian royal art, ... probably suggesting the fate of enemies." This work, therefore, has a second layer of meaning, indicating a political agenda whereby the artist is attempting to stir up community pride and pugnacity. It is interesting to compare works like these to the elaborate relief carving of religious alters in the European Renaissance - one of many examples of analogies between historic traditions between continents.

Wood - Collection of British Museum, London, England

Artist: Ben Enwonwu

Nigerian artist Ben Enwonwu's stunning portrait shows a woman looking off to the left, staring absently past the viewer. The colors of the background, her head scarf, and even her skin tone are similarly muted, traversing shades of brown, cream, grey, and white. These appear in contrast to the more vibrant - though still soft - blue of the cloth draped over her left shoulder. The subject of this painting is one of the Nigerian royal princesses, Adetutu Ademiluyi. Enwonwu's rendering of her, one of three likenesses he created of the princess, became highly revered and helped to cement the artist's reputation. According to author Sarah Cascone, "Enwonwu tracked down the princess in the town of Ile-Ife and convinced the royal family to let him paint her portrait...The painting became a Nigerian icon, a sort of African Mona Lisa ; poster reproductions hang on walls all over the country". Interestingly, this painting was lost for several decades before being found in a home in London in 2017, a story which only adds to the magic and mystique of the piece. This painting is an important example of how traditional themes and approaches informed the development of modern African art. Putting aside the historical example of cave painting, two-dimensional art was in relatively scant evidence across the continent until around the 19 th century, to which a wide variety of styles can be dated. Enwonwu, born in Nigeria in 1917, worked in the wake of these traditions and became the most celebrated African painter of the twentieth century. His approach was strongly informed by Yoruba and other regional artistic themes and styles, and is therefore interesting to consider relation to the other works of African art.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Artist: Aboudia

A vibrant and colorful work, this painting by contemporary Ivorian-American artist Aboudia, depicts several abstracted and loosely rendered figures with enlarged eyes staring hauntingly out at the viewer. With its sketch-like quality the work resembles graffiti art - the first medium in which Aboudia worked. It also provides an important example of how today's African artists draw inspiration from and contemporize the essence of early African art. In this case, the influence is particularly evident in the abstracted facial and bodily appearance of his figures. Abdoulaye Diarrassouba, generally known as Aboudia, was born in the West-African country of Ivory Coast, where violence was a significant part of his upbringing. The country's two civil wars during the 2000s and 2010s became a subject for much of his work, as he turned to art to address the impact of the conflicts on his fellow citizens' psychology. As described by Bonhams, "during the 2011 crisis, Aboudia took refuge in his basement studio where he documented the surrounding violence on large scale canvases that channeled the brutal energy and horrors that were happening above ground. Soldiers with haunted, skull-like faces people these works. The artist has been compared to both Goya and Basquiat for his ability to fuse despair and anger with vigorous energy. Aboudia himself has commented that he uses 'colour to transform sadness into happiness'." For Aboudia, works like these simply reflect his keen desire to record the physical and emotional parameters of the world around him. At the same time, he has also spoken of himself as a mouthpiece for Ivorian culture. He states: "I was simply describing a situation, to create a record of my country's recent history. Artists, writers, filmmakers are spokespersons for an entire nation, their nation, and the world."

Acrylic and oil-stick on canvas - Private Collection

Beginnings and Development

First africans to make art.

African is home to some of the earliest evidence of art-making anywhere in the world. The first examples of African art include paintings made on rocks and on the interior walls and ceilings of caves. The earliest specimens are works from 23,000 BCE found in the Apollo 11 Cave in Namibia, including depictions of animals and human figures. While the purpose of these drawings will never be known, the fact that they were made at all indicates their significance to the cultures that produced them, given that early humans were hunter-gatherers who did not stay in one place for long.

What was depicted in these earliest paintings helps to shed light on life in this period, providing a record of the animals that lived and served as a food-source at the time. What is more mysterious about these paintings is the inclusion of many composite creatures with both human and animal features. Their depiction has led many to believe that there was a shamanistic and spiritual aspect to the drawings, and that they may have been used in rituals and ceremonies. At the very least, it shows that prehistoric humans in Africa, as elsewhere, possessed highly developed minds capable of rendering imaginary as well as figurative scenes and forms.

The content of the drawings and the location of these paintings throughout the continent also provide clues as to what life was like for the earliest Africans, including how it changed over decades and centuries. Taking the example of South Africa, African art specialist Frank Willett notes that "the earliest art consists of simple engravings, often scarcely visible....characterized by their peacefulness; the art is moreorless [sic.] naturalistic and there is no recognizably modern subject-matter. The later paintings are less carefully executed and include elaborate scenes of ceremonies, raids and battles. In the early phase of this period the different populations seem to be co-existing peacefully, but the late phase, the paintings of which are mostly concentrated round the south-eastern part of South Africa, reflects a period of constant struggle."

Unlike with European cave art , African art rendered in this style continued to be created long after the Paleolithic period, helping us to reconstruct the story of different communities over a longer timeframe, as well as the history of foreign exploration on the continent. As Willett explains, "it is usually possible to distinguish Bushmen (short stature, painted in yellow, red or brown and carrying bows and arrows), Bantu (tall stature, usually painted in black with ornaments on the arms and legs and armed with spears and shields) and Europeans (recognizable by their characteristic clothing, and often shown with guns and horses). Many allegedly foreign influences have been claimed in the art."

It is important to note that cave paintings were not the only type of art made during early African art history. Some of the oldest examples of African sculpture were produced by cultures associated with modern Nigeria, including Nok figural and animal statues dating back to 500 BCE. The pottery of the Yelwa people, meanwhile, can be traced back to 100 CE and Bura sculptures to 200 CE onwards.

Western Misunderstandings About African Art

For a long time, African art remained unknown to outsiders. It was only during the 15 th century that the continent began to be explored - and exploited - by foreign cultures, and African art began to be seen for the first time by Europeans. The artistic cultures discovered often seemed mysterious as they were so unlike anything that had been seen before. This led to misunderstandings and incorrect assumptions about what the art signified, as well as the myth that very little if any art had been made in the centuries prior to European journeys to Africa. According to Frank Willett, "very little art was brought back from Africa until the end of the nineteenth century", and many of the writings produced in that era reflected Eurocentric biases: "they are in some respects fallible guides, for they start from the premise of Western ideas of beauty and all too often express themselves ethnocentrically." It took several decades for a real appreciation and understanding of early African art to begin to be fostered by foreign scholars.

Concepts and Styles

Geographical distinctions.

The continent of Africa is vast, and at present comprised of 54 countries. It is no surprise, then, that its historical sculptural traditions are diverse, with significant geographical variations. Speaking of these distinctions, Frank Willett states that: "examples of African sculpture exhibited in museums or illustrated in books on African art are commonly considered to be representative of the style of the people from whom they were collected. William Fagg, for example, writes that 'every tribe is from the point of view of art, a universe to itself. [The tribe] uses art among many other means to express its internal solidarity and self-sufficiency, and conversely its difference from all others.'"

In spite of this diversity, some characteristics are shared in common across the continent. This was especially true during the early centuries of Africa's artistic history. Much of the sculptures and masks produced, for example, were used for religious purposes, whether as ceremonial talismans or, as in the case of Mali's Dogon community, as homes for the spirits of dead ancestors. Many such works are believed to have been originally painted and are small in size to make them portable. As Willett explains, one other feature of historical African sculpture, "which has intrigued scholars from the first is that the head is commonly represented as disproportionately large."

Spiritual Importance of African Sculptures and Masks

African sculptures produced for religious purposes, as elsewhere, can be imagined as having had a magical power to their creators, helping to bring about the wishes of an individual or community. The three-dimensional art of the Loango people in the Congo, for instance, according to Frank Willett, often includes "nails or metal blades", driven in to them "to activate their power to obtain supernatural aid." The Congo's Songye people, meanwhile, believe their figural sculptures can act as intermediaries between themselves and their dead ancestors.

The spiritual qualities of African art perhaps come across most clearly in the rich variety of masks created throughout the centuries. These are often used in ceremonies and ritual performances, and many tribes believe that when masks are worn in this context the wearer is able to communicate with the dead, with gods, or with other supernatural forces. While the style and distinguishing features of these masks often vary with geographical location, an interesting commonality is that most African masks were not intended to be shown or shared outside the community. Sometimes, masks were not even made visible to the community itself except in specific contexts such as ceremonies and celebrations.

As Frank Willett explains, even today "most people interested in African sculpture are unable to see it in use, and must form their own impressions from museum displays. A museum usually possesses only the wooden part of a mask, which it may display under a spotlight which projects a single interpretation of the sculpture. Kenneth Murray has pointed out that masks 'are intended to be seen in movement in a dance; frequently one which is inferior when held in the hand looks more effective than a finer carving when seen with its costume. It is moreover, essential to see masks in use before judging what they express, for it is easy to read into an isolated masks what was never meant to be there.'"

As foreign travel to Africa became more common, these masks were increasingly brought back home to explorers' own countries, and fascination with this striking artistic tradition grew. Over time, the original sanctity of these items has been increasingly forgotten, with copies of masks sold commercially and even displayed as decorative items in homes.

Early Developments in Pottery

While the Ancient Greeks are often credited for their developments in pottery, there is a rich tradition of same practice in Africa. In fact, as Frank Willett explains, "pottery appears to have been made in Africa for longer than anywhere else in the world. It has been dated to the tenth and eighth millennia BC in the central Sahara."

Despite the rich variety of African pottery, as with much of the art of this continent, it took a long time for work to be discovered and valued across the rest of the world. According to writer and curator Diana Lyn Roberts, "until recently, African ceramics has held a somewhat peripheral position in the Western artistic consciousness and in museum holdings. The influence of African art on the early Modernists is a common axiom in the Western canon...but the weight of art history - and the colonial collections that inform it - rests almost entirely on the shoulders of carved masks and figurative sculpture....Yet the prominence of ceramics in traditional daily life and ritual, not to mention indigenous systems of value and connoisseurship, tells a different story of the African engagement with clay and aesthetic continuities between materials."

The types and techniques of African pottery are as diverse as the different geographical locations where it is created and the groups of people who make it. Early on, works were often made without the use of a wheel, instead formed using the older "coil" method. This labor-intensive process, which was mostly undertaken by women, even involved crushing the clay by hand before it was worked to make the pottery. While many works of African pottery are purely functional and often used to carry liquids, others are highly decorative and have a decorative, even figurative, element - these works have generally appealed most to outsiders. This carries true to this day, with pottery still heavily produced in Africa.

African Textiles

While sculptures and masks are arguably the most widely recognized types of African art, textile design and manufacturing have also been an important aspect of art-making throughout the continent's history. The fabrics produced, as well as the processes used, tend to vary by country, as do norms concerning the gender of the weaver.

The patterns, designs, and colors used are of key importance in helping to make many examples of African textile works of art. Indigo is one of the most popular colors, along with shades of red and green. Traditional practices are employed to dye textiles. Resist dyeing, in which wax is applied to certain areas of a cloth and then dye applied to seep into the uncovered areas, is one of the most common techniques. However, other traditions also exist. In Mali, the favored method is mud-dyeing, using the natural mud from ponds to stain fabrics.

As with so much African art, textiles can often have both a functional use, for example, in the home or as clothing, and a spiritual role, used for costumes worn in ceremonies and rituals. While textile-making has been part of life in Africa for centuries, its popularity continues to grow to this day. Today, African textiles have achieved wide global appeal and have influenced both clothing and interior décor across the world. This has led some to consider African textiles to have transitioned in some cases from a type of fine art to a commercial product due to their popularity and use.

Interestingly, African textile production is not without controversy, as some believe the most popular designs are in fact based on designs from the Caribbean which were brought to be traded in West Africa by Dutch merchants. West-African craftspeople began incorporating these styles into their own designs. For some, this prevents many examples of African textiles from being considered uniquely and originally African.

Regardless of the origins, African textile designs continue to evolve today and have influenced many contemporary designers. Outlining the extent of their current appeal, author Franck Kuwonu states that "American artists such as Beyoncé Knowles, Rihanna, Madonna; politicians and world leaders like Nelson Mandela, Ghana's president Nana Addo Dankwa Akuffo Addo,...first ladies Michelle Obama and Jill Biden, have all embraced...Afrochic designs."

Later Developments and Legacy

Contemporary debates over ownership of traditional african art.

Many Africa countries fell victim to the plundering of the colonial era, with works of art taken without consent and placed in museums and galleries around the world. This has resulted in a decades-long effort on the part of many African nations to have historic works repatriated.

Perhaps the most famous case involves a group of sculptural busts and plaques known as the Benin Bronzes. In 1897, it is estimated that thousands of Nigerian works from the Benin Kingdom were taken from the country by British troops. Today, these pieces are in museums around the world, including 900 included in the collection of the British Museum. While works in private collections would be almost impossible to retrieve, serious efforts have been made to have works returned. According to author Alex Greenberger, "for many Nigerians, the Benin Bronzes are a potent reminder of colonialism and its continued effects on African society....Nigerians have continued to demand that museums across the world give back their Benin Bronzes."

While some institutions and governments have begun to seriously discuss returning the Benin Bronzes they own, progress has been slow. It is this inaction that has frustrated many Africans, including artist Victor Ehikhamenor, who has written that "generations of Africans have already lost incalculable history and cultural reference points because of the absence of some of the best artworks created on the continent. We shouldn't have to ask, over and over, to get back what is ours."

Legacy of African Art

Today, Africa can boast a myriad of intersecting artistic traditions, with many modern and contemporary African artists responding to the historical precedents of their nation or community (this is to say nothing of the huge array of African artists working in a more transnational, contemporary or post-conceptual style). Take, for example, the sculptural figures of Peju Alatise, the figures depicted in the paintings of Aboudia and Ben Enwonwu, and the textile sculptures of Nnenna Okore. Speaking of the importance of working in the traditions of her native country and furthering the reputation of African art, Alatise states: "in my opinion, art from Africa remains still largely burdened by negative social, political and economic realities from its mother continent, hence, is unable to be judged by its own merit and without negative bias or condescending patronage. However, Africans must take the responsibility upon themselves to project their own art and learn to value them as one of their greatest cultural exports."

The legacy of African art in the West, meanwhile, cannot be considered apart from the European modernist movements of the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries. Artists such as Georges Braque , André Derain , Juan Gris , Amedeo Modigliani , and Pablo Picasso found it to be the source of great inspiration because of its distinctions from post-Renaissance traditions of art. According to one historical account, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso were emotionally overwhelmed on encountering their first African mask in the studio of their friend André Derain.

The work of these modern artists often clearly shows the influence of African art in the elongation of faces and eyes, while the long necks of figures in Modigliani's portraits bear a striking resemblance to early African masks. In explaining this influence, author Carolina Sanmiguel states that "modern artists were...attracted to African art because it signified an opportunity to escape the rigid and outdated traditions that governed the artistic practice of 19th-century Western academic painting. Contrasting from the Western tradition, African art was not concerned with the canonical ideals of beauty nor with the idea of rendering nature with fidelity to reality. Instead, they cared about representing what they 'knew' rather than what they 'saw'."

Still, African art was so influential on some early modern artists such as Braque and Picasso that they used its forms and structure as the building blocks for the development of the early modern art movement Cubism . According to Sanmiguel, "the impact of African art's intense expression, structural clarity, and simplified forms inspired these artists to create fragmented geometrical compositions full of overlapping planes." An early example is Picasso's iconic painting, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907). Often considered to be a work documenting the transition of his work into Cubist style, the faces of the women in the brothel have the distinct appearance of African masks.

Cubism was not the only modern movement influenced by African art. Its impact can also be seen in works of Fauvism and German Expressionism. As Sanmiguel asserts, "[it] is also visible in the bold angular brushstrokes of Abstract Expressionists such as Willem de Kooning . And of course, contemporary artists as diverse as Jasper Johns , Roy Lichtenstein , Jean-Michel Basquiat , and David Salle have also incorporated African imagery into their works."

It can be argued that many works of modern art inspired by African art, and even certain movements such as Primitivism , which developed at the end of the 19 th century and drew inspiration from African and other tribal arts, helped to perpetuate the myth that African art reflected a state of uncivilized naivety. This was a misconception that would take decades to right, and is still addressed by some contemporary African artists.

Contemporary artists were not, however, the first artists to find fault with the treatment of African sources in modern Western art. Cuban artist Wifredo Lam , for instance, was inspired by African culture but tried to show it differently than many of his European contemporaries. He sought through his work to convey the sophistication and complexity of early African art. According to author Brendan Sainsbury, "for Lam, primitivism meant something more profound. Africa was in his heritage....He even went so far as to align himself with the Afrocubanismo movement which strived...to give greater legitimacy to Black culture by using art to integrate it more deeply into...society."