Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Image credit: Claire Scully

New advances in technology are upending education, from the recent debut of new artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots like ChatGPT to the growing accessibility of virtual-reality tools that expand the boundaries of the classroom. For educators, at the heart of it all is the hope that every learner gets an equal chance to develop the skills they need to succeed. But that promise is not without its pitfalls.

“Technology is a game-changer for education – it offers the prospect of universal access to high-quality learning experiences, and it creates fundamentally new ways of teaching,” said Dan Schwartz, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), who is also a professor of educational technology at the GSE and faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning . “But there are a lot of ways we teach that aren’t great, and a big fear with AI in particular is that we just get more efficient at teaching badly. This is a moment to pay attention, to do things differently.”

For K-12 schools, this year also marks the end of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding program, which has provided pandemic recovery funds that many districts used to invest in educational software and systems. With these funds running out in September 2024, schools are trying to determine their best use of technology as they face the prospect of diminishing resources.

Here, Schwartz and other Stanford education scholars weigh in on some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom this year.

AI in the classroom

In 2023, the big story in technology and education was generative AI, following the introduction of ChatGPT and other chatbots that produce text seemingly written by a human in response to a question or prompt. Educators immediately worried that students would use the chatbot to cheat by trying to pass its writing off as their own. As schools move to adopt policies around students’ use of the tool, many are also beginning to explore potential opportunities – for example, to generate reading assignments or coach students during the writing process.

AI can also help automate tasks like grading and lesson planning, freeing teachers to do the human work that drew them into the profession in the first place, said Victor Lee, an associate professor at the GSE and faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning. “I’m heartened to see some movement toward creating AI tools that make teachers’ lives better – not to replace them, but to give them the time to do the work that only teachers are able to do,” he said. “I hope to see more on that front.”

He also emphasized the need to teach students now to begin questioning and critiquing the development and use of AI. “AI is not going away,” said Lee, who is also director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), which provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students across subject areas. “We need to teach students how to understand and think critically about this technology.”

Immersive environments

The use of immersive technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality is also expected to surge in the classroom, especially as new high-profile devices integrating these realities hit the marketplace in 2024.

The educational possibilities now go beyond putting on a headset and experiencing life in a distant location. With new technologies, students can create their own local interactive 360-degree scenarios, using just a cell phone or inexpensive camera and simple online tools.

“This is an area that’s really going to explode over the next couple of years,” said Kristen Pilner Blair, director of research for the Digital Learning initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, which runs a program exploring the use of virtual field trips to promote learning. “Students can learn about the effects of climate change, say, by virtually experiencing the impact on a particular environment. But they can also become creators, documenting and sharing immersive media that shows the effects where they live.”

Integrating AI into virtual simulations could also soon take the experience to another level, Schwartz said. “If your VR experience brings me to a redwood tree, you could have a window pop up that allows me to ask questions about the tree, and AI can deliver the answers.”

Gamification

Another trend expected to intensify this year is the gamification of learning activities, often featuring dynamic videos with interactive elements to engage and hold students’ attention.

“Gamification is a good motivator, because one key aspect is reward, which is very powerful,” said Schwartz. The downside? Rewards are specific to the activity at hand, which may not extend to learning more generally. “If I get rewarded for doing math in a space-age video game, it doesn’t mean I’m going to be motivated to do math anywhere else.”

Gamification sometimes tries to make “chocolate-covered broccoli,” Schwartz said, by adding art and rewards to make speeded response tasks involving single-answer, factual questions more fun. He hopes to see more creative play patterns that give students points for rethinking an approach or adapting their strategy, rather than only rewarding them for quickly producing a correct response.

Data-gathering and analysis

The growing use of technology in schools is producing massive amounts of data on students’ activities in the classroom and online. “We’re now able to capture moment-to-moment data, every keystroke a kid makes,” said Schwartz – data that can reveal areas of struggle and different learning opportunities, from solving a math problem to approaching a writing assignment.

But outside of research settings, he said, that type of granular data – now owned by tech companies – is more likely used to refine the design of the software than to provide teachers with actionable information.

The promise of personalized learning is being able to generate content aligned with students’ interests and skill levels, and making lessons more accessible for multilingual learners and students with disabilities. Realizing that promise requires that educators can make sense of the data that’s being collected, said Schwartz – and while advances in AI are making it easier to identify patterns and findings, the data also needs to be in a system and form educators can access and analyze for decision-making. Developing a usable infrastructure for that data, Schwartz said, is an important next step.

With the accumulation of student data comes privacy concerns: How is the data being collected? Are there regulations or guidelines around its use in decision-making? What steps are being taken to prevent unauthorized access? In 2023 K-12 schools experienced a rise in cyberattacks, underscoring the need to implement strong systems to safeguard student data.

Technology is “requiring people to check their assumptions about education,” said Schwartz, noting that AI in particular is very efficient at replicating biases and automating the way things have been done in the past, including poor models of instruction. “But it’s also opening up new possibilities for students producing material, and for being able to identify children who are not average so we can customize toward them. It’s an opportunity to think of entirely new ways of teaching – this is the path I hope to see.”

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Biden will cap off a week of outreach to Black Americans with Morehouse commencement

Deepa Shivaram

Family members of plaintiffs in the historic Brown v. Board of Education met with President Biden to mark the 70th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision. Susan Walsh/AP hide caption

Family members of plaintiffs in the historic Brown v. Board of Education met with President Biden to mark the 70th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision.

President Biden is engaged in a flurry of events this week centered around the 70th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case that ended racial segregation in public schools, part of an intensified push to court Black voters crucial to his reelection bid.

On Sunday, he will give a closely watched commencement speech to Morehouse College, a historically Black university in Georgia.

Biden held a private meeting with plaintiffs and family members of plaintiffs from the Brown case on Thursday at the White House, and on Friday, he gave remarks at an NAACP event marking the Brown anniversary at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. On the weekend, he heads to the swing state of Michigan, where he'll address an NAACP dinner in Detroit.

We asked young Black voters about Biden and the Democrats. Here's what we learned

The Biden campaign said the engagement was a signal of how the administration has prioritized issues important to Black voters — and how it is working to earn their support.

"We are not, and will not, parachute into these communities at the last minute, expecting their vote," said Trey Baker, a senior adviser to the campaign, in a memo.

Biden's other engagements include a meeting with the Divine Nine , a group of historically Black sororities and fraternities, and interviews with Black media outlets. On Sunday, he will also visit a Black-owned small business in Detroit, Baker said.

Polling shows lack of enthusiasm among Black voters

Black voters have long been the backbone of the Democratic party, and helped ensure Biden's win in 2020. But if turnout is lower this year compared to four years ago, it could hurt Biden's chances for reelection.

A recent survey from the Washington Post and Ipsos showed that only 62% of Black voters said that they are absolutely certain to vote this year, compared to 74% this time in 2020.

A Biden victory in Michigan could depend on Black Voters

The poll also showed that just 38% of Black Americans feel Biden's policies have helped Black people, something Biden tried to explain more on in media appearances this week.

Talking over the phone to Atlanta radio show host Darian "Big Tigger" Morgan for his morning show this week, Biden listed off what he says he's done for Black Americans, including lowering unemployment rates and cancelling some student debt. He also went after his opponent.

"Trump hurt Black people every chance he got," Biden said.

President Biden speaks at the National Museum of African American History and Culture on May 17. Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

President Biden speaks at the National Museum of African American History and Culture on May 17.

In his speech on Friday, Biden told the NAACP that "an extreme movement led by my predecessor and his MAGA allies" was today's "insidious" version of the resistance faced by the Little Rock Nine in Arkansas, after the Brown decision.

Biden blamed former President Donald Trump for naming justices to the Supreme Court who then ended affirmation action for college admissions — and for working to end diversity, equity and inclusion programs across the country.

"They want a country for some, and not for all," Biden said.

The week's events will culminate with the president's commencement address at Morehouse

On Sunday, Biden will cap off his week giving the commencement address at Morehouse College.

His visit there has already received pushback from students, who have been critical of Biden in his handling of Israel's war in Gaza. The university's president David Thomas told NPR that he would halt the commencement ceremonies altogether if protests became too disruptive.

"Faced with the choice of having police take people out of the Morehouse commencement in zip ties, we would essentially cancel or discontinue the commencement services on the spot," Thomas said.

Biden uses Howard University commencement address to appeal to Black voters

Steve Benjamin, who leads the White House Office of Public Engagement, visited the campus to meet with some students and faculty earlier this week.

"The common thread was that they wanted to make sure we're centering the young people and that the president did that on Sunday," Benjamin said. "The goal will be to make sure we use this as an opportunity to continue to elevate the amazing work that's been done at Morehouse."

He stressed the investments the Biden administration has made in HBCUs. Since taking office, the Biden administration has funded $16 billion in support for HBCUs.

In his remarks to the NAACP, Biden paid tribute to Morehouse's history. The college was started after the Civil War to give freed slaves education and training to become ministers.

"The founders of Morehouse understood something fundamental: education is linked to freedom," he said. "Because to be free means to have something that no one can ever take away from you."

- black voters

- morehouse college

- black americans

- divine nine

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

High school students, frustrated by lack of climate education, press for change

Youth activists pushing for more climate education in Minnesota schools say working with peers to draft legislation gives them hope for a future under threat. (AP Video: Mark Vancleave)

B Rosas, left, Lucia Everist, center, and Libby Kramer, of Climate Generation, speak to the Minnesota Youth Council, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024, in St. Paul, Minn. The advocates called on the council, a liaison between young people and state lawmakers, to support a bill requiring schools to teach more about climate change. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

- Copy Link copied

Libby Kramer, left, Lucia Everist, center, and B Rosas, of Climate Generation, speak to the Minnesota Youth Council, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024, in St. Paul, Minn. The advocates called on the council, a liaison between young people and state lawmakers, to support a bill requiring schools to teach more about climate change. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

Lucia Everist, of Climate Generation, center, speaks to the Minnesota Youth Council, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024, in St. Paul, Minn. The advocates called on the council, a liaison between young people and state lawmakers, to support a bill requiring schools to teach more about climate change. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

FILE - Water floods a damaged trailer park in Fort Myers, Fla., Oct. 1, 2022, after Hurricane Ian passed by the area. (AP Photo/Steve Helber, File)

Minnesota Sen. Nicole Mitchell, left, sits with members of Climate Generation, from second left, B Rosas, Lucia Everist, Libby Kramer and Minnesota Rep. Larry Kraft, right, as they speak the Minnesota Youth Council, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024, in St. Paul, Minn. The advocates called on the council, a liaison between young people and state lawmakers, to support a bill requiring schools to teach more about climate change. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

Libby Kramer, of Climate Generation, right, speaks to the Minnesota Youth Council, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024, in St. Paul, Minn. The advocates called on the council, a liaison between young people and state lawmakers, to support a bill requiring schools to teach more about climate change. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

B Rosas, back left, Lucia Everist, back center, and Libby Kramer, back right, of Climate Generation, speak to the Minnesota Youth Council, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024, in St. Paul, Minn. The advocates called on the council, a liaison between young people and state lawmakers, to support a bill requiring schools to teach more about climate change. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

ST. PAUL, Minn. (AP) — Several dozen young people wearing light blue T-shirts imprinted with #teachclimate filled a hearing room in the Minnesota Capitol in St. Paul in late February. It was a cold and windy day, in contrast to the state’s nearly snowless, warm winter.

The high school and college students and other advocates, part of group Climate Generation, called on the Minnesota Youth Council, a liaison between young people and state lawmakers, to support a bill requiring schools to teach more about climate change .

Ethan Vue, who grew up with droughts and extreme temperatures in California, now lives in Minnesota and is a high school senior pushing for the bill.

“I just remember seeing my classmates always sweating, and they’d even drench themselves in water from the water fountains,” Vue said in a phone interview, noting climate change is making heat waves longer and hotter, but they didn’t learn about that in school.

“The topic is brushed on. If anything, we just learn about, there’s global warming, the planet’s warming up.”

Libby Kramer, left, Lucia Everist, center, and B Rosas, of Climate Generation, speak to the Minnesota Youth Council, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024, in St. Paul, Minn. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

In places that teach to standards formulated by the National Science Teachers Association, state governments and other organizations, many kids learn about air quality, ecosystems, biodiversity and land and water in Earth and environmental science classes.

But students and advocates say that is insufficient. They are demanding districts, boards and state lawmakers require more teaching about the planet’s warming and would like it woven into more subjects.

Some states and school districts have moved in the opposite direction. In Texas , the board of education turned down books with climate information. In Florida, school materials deny climate change .

“Someone could theoretically go through middle school and high school without really ever acknowledging the climate crisis,” said Jacob Friedman, a high school senior in Florida who hasn’t learned about climate except for in elective classes. “Or even acknowledging that there is an issue of global warming.”

That’s bizarre to Friedman, who experienced firsthand when Hurricane Ian closed nearby schools and submerged homes in 2022.

A study conducted after the storm found that climate change added at least 10% more rain to Hurricane Ian. Experts also say hurricanes are intensifying faster because of the extra greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that are collecting heat and warming the oceans.

“What an unfair reality to have a young person graduate from high school,” said Leah Qusba, executive director of nonprofit Action for the Climate Emergency, “without knowing about the biggest existential threat that they’re going to face in their lifetime.”

Some places are adding more instruction on the subject. In 2020, New Jersey required teaching climate change at all grade levels. Connecticut followed, then California. More than two dozen new measures across 10 states were introduced last year, according to the National Center for Science Education.

Libby Kramer, of Climate Generation, right, speaks to the Minnesota Youth Council, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024, in St. Paul, Minn. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

Where some proposals require teaching the basic science and human causes of climate change , the Minnesota bill goes further, requiring state officials to guide schools on teaching climate justice, including the idea that the changes hit disadvantaged communities harder .

Some legislators say they’ve heard from school administrators and teachers who say that goes too far.

“What was said to me is: ‘Why are we pushing a political perspective, a political agenda?’” Minnesota Rep. Ben Bakeberg, a Republican, said during a House Education Policy Committee hearing in March 2023. “That’s a reality.”

The bill didn’t advance in the 2023 session. Now it hasn’t this year either. Supporters say they will try again next year.

Aware of such opposition, some students interested in climate opt to campaign at their schools rather than through the legislative process.

Three years ago, floods destroyed Ariela Lara’s mom’s village in Oaxaca, Mexico, while they were visiting. Then Lara came home to California and was hit by smoke-filled skies caused by wildfires that pushed thousands to evacuate or be stuck inside for weeks.

Yet despite what she was seeing, Lara felt in school she was only taught about recycling and carbon footprints, a measure of a person’s personal greenhouse gas emissions.

So she went to the board of education.

“I had to really think about how I could go to the people in power to really rewrite the curriculum we were learning,” Lara said. “It would get so tiresome because for me, I was the one that was really trying to enforce it.”

By the time her school offered Advanced Placement Environmental Science, Lara was too senior to enroll in it. AP Enviro does cover climate change , according to the College Board, but it’s also more broad.

B Rosas, back left, Lucia Everist, back center, and Libby Kramer, back right, of Climate Generation, speak to the Minnesota Youth Council, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024, in St. Paul, Minn. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

When targeted efforts don’t work, some students feel they’re on their own.

For high school junior Siyeon Joo, climate education seems like a no-brainer where she lives in Lafayette, Louisiana, which was hit hard by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and has been affected by several other intense storms and heat waves.

But Joo wasn’t exposed to climate change at her public middle school and an educator there once told her it wasn’t real.

“I remember sitting in that classroom,” the now-16-year-old said, “being really angry that that was the system that was being forced upon me at the time.”

It took enrolling in a private school for Joo to learn about these topics. Many students don’t have that option.

Experts say climate material could be worked into lessons without burdening schools or putting the onus on students. But much like with legislation, that will take time students say they don’t have.

“I was part of these communities that were really just affirming how much is at stake if we don’t take action,” said Lara, the student in California, recalling how important to her it would have been to receive education about her experiences. “You should be able to go to school and learn about the gravity which the climate crisis is at.”

Alexa St. John reported from Detroit and Doug Glass reported from St. Paul, Minn.

Alexa St. John is an Associated Press climate solutions reporter. Follow her on X, formerly Twitter, @alexa_stjohn . Reach her at [email protected] .

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org .

- Share full article

A Night to Remember at the Opera, Complete With a Phantom

About 130 children took part in a sleepover at Rome’s opera house, part of a campaign to make up for a lack of music education by making the theater and the art form more familiar and accessible.

Children attending a rehearsal at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome. Credit...

Supported by

By Elisabetta Povoledo

Photographs by Alessandro Penso

Reporting from Rome

- May 13, 2024

In the pitch-dark auditorium of Rome’s Teatro Costanzi, a high-pitched lament floated from the top galleries. Dozens of flashlights snapped on, their beams crisscrossing crazily, seeking the source of the sound.

The shafts of light homed in on a spectral figure — a slim, dark-haired woman dressed in white, moving at a funereal pace and plaintively singing. In the audience, 130-odd children, ages 8 to 10, let loose squeals, some gasps, and one “it’s not real.” Several called out “Emma, Emma.”

The children had just been told that the Costanzi, the capital’s opera house, had a resident phantom. No, not that one. This was said to be the spirit of Emma Carelli, an Italian soprano who managed the theater a century ago, and loved it so much that she was loath to leave it, even in death.

“The theater is a place where strange things happen, where what is impossible becomes possible,” Francesco Giambrone, the Costanzi’s general manager, told the children Saturday afternoon when they arrived to participate in a get-to-know-the-theater-sleepover.

Music education ranks as a low priority in Italy, the country that invented opera and gave the world some of its greatest composers. Many experts, including Mr. Giambrone, say their country has rested on its considerable laurels rather than cultivate a musical culture that encourages students to learn about their illustrious heritage.

With little backing from schools or lawmakers, arts organizations like the Costanzi have concluded that it is up to them to reach out to the young.

Mr. Giambrone sought to dispel opera's stuffy image by abandoning the genre’s strict dress code. That change, like the sleepover, is part of his effort to make opera, often seen as an elitist, highbrow and abstruse art form for the initiated, more familiar and accessible, especially to children.

“We believe that the theater should be for everyone, and that it should make people feel at home,” Mr. Giambrone said in an interview. Hence the decision to welcome youngsters to eat, sleep and play there. “Once a theater is a home, it is no longer something distant, something a bit austere to fear, or somewhere you feel inadequate,” he said.

“There’s a lot of talk about Made in Italy, but real shortsightedness when it comes to our musical patrimony, which is envied throughout the world,” said Maestro Antonio Caroccia, who teaches music history at the Santa Cecilia conservatory in Rome. He said that “politicians are deaf to it.”

“Italy is far behind” many other countries, said Barbara Minghetti, of Opera Education , which creates programs for children. “This I can guarantee.”

When he was in Italy’s Parliament, Michele Nitti, a musician and former lawmaker with the 5 Star Movement, proposed a law adding musical education to school curricula. His bill never made it to a parliamentary vote.

He said that not even Giuseppe Verdi, the 19th century composer who also served in Parliament, was able, in his time, to get his fellow lawmakers to support music education in schools.

Mr. Nitti was also unsuccessful in getting lawmakers to declare opera singing a national treasure. He did support the country’s successful bid to have the practice of opera singing in Italy put on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity after switching to the Democratic Party.

“Oh well,” he said.

Rather than letting its opera culture wither, Mr. Giambrone said, “Italy should be teaching other countries how it’s done.”

At the Teatro Costanzi, more than half of the children at the sleepover belonged to scout troops from Rome’s outlying neighborhoods. They were accompanied by coolheaded scout leaders who — impressively — commanded silence just by raising a finger.

Most of the children had never visited the theater before. “Come to think of it, I haven’t been there either,” said Gianpaolo Ricciarelli, one of the parents who dropped off his son.

Another father, Armando Cereoli, said, “Between video games, cellphones and Netflix, there’s tough competition to get kids interested in beautiful things.”

Some of the children came from disadvantaged neighborhoods, so the visit was “a chance to free their minds and to dream,” said Sara Greci, a scout leader and Red Cross worker who brought four girls from a home for abused women and their children.

The opera house runs several outreach programs for the homeless or people who live in Rome’s most far-flung neighborhoods, a way to open the theater to the city and broaden its reach, said Andrea Bonadio, who was hired by the theater to work on such programs.

Nunzia Nigro, the theater’s director for marketing and education, said that several of the children who had participated in the theater’s educational programs over the past 25 years were loyal patrons today. “We’re beginning to reap some of those efforts, and have a younger public,” she said.

Ms. Nigro helped organize the sleepover, tailoring it for 8- to 10-year-olds — old enough to sleep away from home but not old enough to have hormones kick in, she said. As it was, two boys felt homesick enough to get their moms to pick them up.

On Saturday, the children watched part of a rehearsal for an upcoming performance of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony — “the conductor uses a wand to direct music, not so different from Harry Potter’s but more important,” Ms. Nigro said. They learned how the staff cleaned the world’s biggest chandelier in a historic building, and they got to know the ins and outs of the theater via a treasure hunt (read general mayhem) that had them scrambling up and down stairs, flitting in and out of stalls like a multicharacter French farce.

Emma the phantom — Valentina Gargano , a soprano in the opera’s young artists program — made an encore, exacting a promise from the children that they would tell their friends about “this magic place” and come back when they grew up.

One girl had been so convinced that Ms. Gargano was a real ghost that the organizers made sure they met when the soprano was in street clothes.

After being serenaded with music, including Brahms’ classic lullaby, the children settled down (or tried to) in a patchwork of sleeping bags on an artificial green lawn used in a previous production of Madama Butterfly. Above them loomed oversize photos of some of the stars who performed at the Costanzi, like Maria Callas, Herbert von Karajan and Rudolf Nureyev.

After breakfast on Sunday, the children took part in workshops at which they designed colorful paper ballet costumes, learned basic ballet positions, sang as part of a choir (some more enthusiastically than others) and played an opera-themed version of snakes and ladders. The game was designed and overseen by Giordano Punturo, the opera’s stage manager, done up in a tuxedo and colorful top hat.

He didn’t know about the kids, he said, “but I had the time of my life.”

After a group singalong and photo, it was almost time to head home.

“Did you have fun?” Mr. Giambrone asked the kids. “Yes!!” they cheered. “Did you sleep well?” he asked, to a more mixed response. Several “No “s were notably heard. Come back soon, he said.

After hugging his parents who had come to pick him up, Andrea Quadrini, almost 11, couldn’t wait to tell them that his team had won at snakes and ladders, and that the treasure hunt had been especially fun.

“Wow,” he said. “I saw an opera theater for the first time.”

Elisabetta Povoledo is a reporter based in Rome, covering Italy, the Vatican and the culture of the region. She has been a journalist for 35 years. More about Elisabetta Povoledo

Find the Right Soundtrack for You

Trying to expand your musical horizons take a listen to something new..

Meet Carlos Niño , the spiritual force behind L.A.’s eclectic music scene.

Listen to a conversation about Steve Albini’s legacy on Popcast .

Arooj Aftab knows you love her sad music. But she’s ready for more.

Hear 9 of the week’s most notable new songs on the Playlist .

Portishead’s Beth Gibbons returns with an outstanding solo album.

Advertisement

The child care system is broken. Here are 5 striking statistics that show why.

As more than 1,000 providers shut their doors for a day without child care, we examine a few numbers that reveal why the landscape is in crisis..

On Monday, more than 1,000 U.S. child care providers plan to temporarily shut down facilities or call in sick to take part in the country's third annual “Day Without Child Care.” The event seeks to raise awareness about early learning professionals' critical role in the nation’s economy and how little they earn in return for that labor.

“We can’t make it work without more money, bottom line,” Yessika Magdaleno, who has provided child care for nearly 23 years in Garden Grove, California, said in a statement. “I’m always told that I should close my doors and try working in a different, more lucrative industry, but I don’t want to do that.”

For a short period after the COVID-19 pandemic hit, society seemed to acknowledge that early learning professionals are the workforce behind the workforce, making it possible for essential employees to be on-site at their jobs.

The sector received an infusion of relief funding, including a historic $24 billion from the federal government. Tens of thousands of centers that would’ve otherwise shuttered kept their staff on payroll and stayed open. Parents were able to keep their positions.

But that funding expired last fall . And while some states have since increased child care allocations , many have not. An analysis published this month by the National Women’s Law Center found that, in states without significant funding increases, the percentage of families unable to access child care has grown since the federal dollars dried up. Nearly a quarter – 23.1% – can’t find or pay for care, up from 17.8% in the fall.

The workers planning to take the day off have drawn attention to inequities faced in their profession. Here are five striking statistics that shed light on America’s broken child care system.

Day Without Child Care: Hundreds of providers closed as educators went on strike. Here's why

That’s the median hourly wage for a child care worker in this country.

While the numbers vary by state and locale, these professionals earn less in part because they work with younger children, a situation scholars refer to as "a pay penalty." Poverty rates among early childhood professionals are 7.7 times higher than those among educators who teach students in grades K-8, according to research out of the University of California, Berkeley's Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

The pay penalty is especially pronounced among women of color, who account for much of the child care workforce. Black early educators, for example, are paid $0.78 less per hour on average than their white counterparts, according to the UC-Berkeley research.

One in 5 families spends this amount or more on child care in a single year, according to a report from Care.com , an online marketplace for finding such services. That’s nearly $12,000 more than the average cost of attending a public four-year university – including tuition, fees and room and board. And it’s more than double the average cost of rent in the U.S.

More broadly, the report found that nearly half of parents spend more than $18,000 a year on care expenses. This is unaffordable for most families, especially people struggling to make ends meet.

Yet the vast majority of children whose parents would be eligible for subsidies through the largest federal child care program don’t receive that support in a given month . That program – the Child Care and Development Block Grant – is severely underfunded.

According to a federal report last year, that’s the portion of a single parent’s income, in some areas (such as Washington, D.C.), that is spent on infant care . The cost is untenable even in states on the low end (such as South Dakota), where infant care accounted for a quarter of a single parent’s household income.

High child care costs often compel parents to leave the workforce. But without alternatives, many single parents turn to the lowest-cost option, which may mean unlicensed providers .

14.4 million

This is how many U.S. children 5 and younger have all available parents in the workforce and thus need care, Census data suggest . That's roughly 2 in 3 children in this age group . In other words, households with more than one income struggle, too.

Many parents find themselves having to choose between work and child care. In one 2023 poll of voters, more than a quarter of respondents with children under 6 said they or a family member had to miss work because of child care issues . Nearly 6 in 10 participants who aren’t working or only working part time said they’d work full time if they had access to quality, affordable child care.

Child care relief: Billions in funding just expired. Costs are already skyrocketing.

$122 billion

According to a report by ReadyNation , this is how much money is sucked out of the nation’s economy due to its child care crisis. The crisis forces parents out of jobs and undermines young children’s learning trajectories, culminating in huge losses in earnings, productivity and revenue.

In other words, it’s not just parents who suffer. Businesses and taxpayers also take a hit.

Why is the child care system so broken? The biggest reason is that such care is too expensive for families, and public funding is inadequate, said Marcy Whitebook, director emerita of UC-Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. “More often than not, public investment is temporary because policymakers decide the problem it was designed to solve is over. Of course, the needs aren't temporary in child care.”

As Kishia Saffold, a child care owner and operator in Alabama, put it, “It’s only a matter of time until the system implodes.”

Draft International Education and Skills Strategic Framework

- Migration Strategy

- Before studying in Australia

- During your studies in Australia

- After studying in Australia

- State and Territory Government resources to support international students

- International education engagement

- Data and research

- Financial assistance for international students

- Recognise overseas qualifications

- Resources to support students

- Australian Strategy for International Education

- Announcements

The draft International Education and Skills Strategic Framework (the Framework) has been released.

- Download Draft International Education and Skills Strategic Framework as a DOCX (298.31kb)

- Download Draft International Education and Skills Strategic Framework as a PDF (613.58kb)

We aim to provide documents in an accessible format. If you're having problems accessing a document, please contact us for help .

Hurry! Offer Valid for a Limited Time Only!

The plus that powers new age classrooms

School Integrated Program

Make your students jee / neet ready.

Learn what you want, how you want

Pioneering Next-gen Education

Discover the latest upgrades for students, schools, and teachers.

Rethink Schooling

Explore our school solutions, powering new age classrooms.

A digital solution that transforms traditional teaching-learning processes in classroom and beyond

Designed to make your school the ultimate destination for JEE / NEET test Preparation

Seamless learning from school to home

Accelerate student progress with an innovative learning platform that keeps them connected with school

Conducting assessments is now hassle-free

A scientifically designed platform for facilitating and automating assessment activities

Empower parents as partners

Fostering a dynamic parent-school collaboration

Transform Learning

Discover our latest solutions for students.

Experience the ease of learning at your own pace with a best-in-class, customisable solution

Engineering your JEE success

Accelerate your JEE dreams with expert guidance and personalized mentoring

Your perfect NEET preparation partner

Realise your medical aspirations with a comprehensive, customised, and rigorous approach to exam preparation

Innovate Teaching

Learn about our solutions for teachers.

Designed to make your teaching easier with the right tools and resources that provide real-time insights into student’s performance

Transforming education for generations

Founded in 2007, Extramarks is a new-age education technology company committed to revolutionizing the way students learn and teachers teach. Our digital learning solutions cover all subjects across boards and follow a curriculum-based approach. Join us today and experience the power of total learning in the digital age with Extramarks.

Number of Schools

Number of teachers, number of students, number of live lectures, number of contents, transformative power of our pedagogy.

Preliminary test to check concept clarity and preparedness in any topic.

Explore the vast content repository with 2D and 3D content on various topics for a fun and effective learning experience.

Solve unlimited practice questions on every topic in MCQ- and subjective-type format and get a 360-degree understanding of all concepts.

Check how well you have learned by attempting tests on various topics and get a complete report of your performance.

Evaluation of conceptual understanding on the basis of test performance reports.

Celebrating Achievements

Inspiring stories from extramarks community.

L.K. Singhania Education Centre

Architect & Engineer

The school that focuses on developing multiple skills & has 40 different clubs for its students.

Saharsh Bhardwaj

Class x- apeejay school, noida, extramarks helped him understand all concepts and score better in exams through interactive live classes and intuitive assessment center..

Mrs. Aditi Mukherjee

Principal gems academy, kolkata, mrs. aditi mukherjee is all praise for extramarks and states that engaging, effective and interactive extramarks modules have proven to be most useful for secondary classes..

Nitya Gargi

Class ix- gaurs international school, live interactive classes are as amazing as physical classroom experience, and with extramarks, she is confident about scoring even better in her next exams..

Mr. Sharad Tiwari

Principal mayoor chopasni school, jodhpur, mr. sharad tiwari points out that extramarks has aided teachers in making the curriculum more captivating and engaging for students..

Laidlaw Memorial School

A school surrounded by coniferous trees & located in the second-largest valley in the world..

Aditi Yadav

Class vi- gaurs international school, greater noida, learning has become convenient with extramarks because of the live interactive classes and recorded sessions that help her revisit concepts any time..

Mr. Joseph M Joseph

Principal st. george’s college, mussoorie, mr. joseph m joseph believes that extramarks is enhancing student’s understanding of various concepts, and contributing to teacher’s professional development..

Sanskriti Rawat

Class ix- dev samaj modern school, delhi, extramarks extremely helpful for her studies with infinite assessments, doubt sessions, accessible mentors, and 24x7 support for any technical issues..

Ms Kamini Bhasin

Principal dps noida, ms kamini bhasin says that her classrooms are bubbling with energy thanks to the informative, engaging and interesting modules provided by extramarks., our partners, trusted by leading schools in india.

Advertisement

Relative educational poverty: conceptual and empirical issues

- Open access

- Published: 29 September 2021

- Volume 56 , pages 2803–2820, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Judith Glaesser ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6173-3596 1

3279 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

This paper’s goal is to discuss implications for the empirical study of low educational status arising from the use of the concept of educational poverty in research. It has two related conceptual foci: (1) the relationship of educational poverty with material poverty and to what extent useful parallels exist, and (2) the distinction of absolute and relative (educational) poverty and whether the notion of absolute (educational) poverty is a sensible one. For the concept of educational poverty to be analytically fruitful, clear conceptualisation and operationalisation of the relevant issues are required. The paper contributes to the aim of providing these by building on existing work on educational poverty and by drawing on relevant work on material poverty as well as discussing some conceptual challenges and some of the challenges arising from the operationalisation of the concepts. Some of these challenges are illustrated using examples based on data from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). In a further step, factors which may lead to a greater risk of being in relative educational poverty are analysed, employing the method multi-value Qualitative Comparative Analysis. The empirical findings highlight the relative nature of educational qualifications: the usefulness of a basic school leaving qualification has changed over time, and it has not been the same for different groups. Thus, a conceptualisation of low educational status as educational poverty has been shown to be useful, and it has been demonstrated that the relative nature of educational poverty ought to be taken into account by researchers.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Relation Between Family Socioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement in China: A Meta-analysis

Education and Parenting in the Philippines

The Public Purposes of Private Education: a Civic Outcomes Meta-Analysis

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Poverty in the sense of material poverty is an everyday term. While the details of an expert definition of material poverty may differ from the way it is understood by lay people, the concept will be immediately understood by everyone more or less in the way in which it is intended. The term “educational poverty”, on the other hand, has not entered everyday vocabulary. This concept was introduced into academic discourse by Allmendinger ( 1999 ) and, up to now, it has mostly been taken up by German and other continental European scholars (e.g., Lohmann and Ferger 2014 ; Solga 2011 ; Blossfeld et al. 2019 ; Quenzel and Hurrelmann 2019a ). Given that it is distinct from the concept of inequality in education, Footnote 1 it has the potential to be an additional conceptual tool for analysing the role of education in enabling participation in modern society. Throughout this paper, educational poverty will be understood as a lack of formal qualifications Footnote 2 which precludes participation in the labour market (and possibly affects other spheres of life such as family life and health) in a way not experienced by individuals with higher levels of education.

Education and the certification of education in the form of qualifications are more important than ever, given technological progress and the accompanying demand for a highly skilled workforce. This tight coupling of skills and job opportunities suggests that the labour market is likely to be the most important area of life on which education has an impact. In addition, there is some evidence that educational status matters in other areas, too: Solga ( 2011 ) reports lower rates of marriage and, among those who do marry, higher rates of divorce for individuals with a low level of qualifications. They also remain childless more frequently than people with higher qualifications, but, conversely, they are also more likely to experience parenthood during their teenage years. In addition, their health tends to be worse (Quenzel and Hurrelmann 2019b ).

In research on material poverty, a distinction is commonly made between absolute and relative poverty, with the latter defining poverty in relation to some standard which can vary between points in time and between societies. As can be seen from the connection between education and the labour market noted above, it seems plausible that this distinction might also be relevant to educational poverty, since the effect on an individual’s life of their educational status is likely to be at least partially dependent on how important educational status is in a particular labour market. Indeed, the relative value of educational qualifications (and other material and immaterial resources) has been discussed extensively (key authors are Dore 1976 ; Hirsch 1976 ; see also, e.g., Thurow 1977 ), though a lack of formal qualifications has not been explicitly conceived as educational poverty by these authors.

This paper’s goal is to discuss implications for the empirical study of low educational status arising from the use of the concept of educational poverty—developed analogously to material poverty—in such research. It has two related conceptual foci: (1) the relationship of educational poverty with material poverty and to what extent useful parallels exist, and (2) the distinction of absolute and relative (educational) poverty and whether the notion of absolute (educational) poverty is a sensible one. For the concept of educational poverty to be analytically fruitful, clear conceptualisation and operationalisation of the relevant issues are required. This paper contributes to the aim of providing these by building on existing work on educational poverty (see above: Allmendinger 1999 ; Blossfeld et al. 2019 ; Lohmann and Ferger 2014 ; Solga 2011 ) and by drawing on relevant work on material poverty as well as discussing some conceptual challenges and some of the challenges arising from the operationalisation of the concepts. I will illustrate some of these challenges using examples based on data from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). In a further step, again drawing on NEPS data, I will analyse three factors which may lead to a greater risk of being in relative educational poverty. They are sex, school qualification, and cohort (i.e., whether someone was born by 1965 or later). Sex is of interest because of the differing experiences of men and women over time (e.g., Blossfeld et al. 2019 ), school qualifications are a prerequisite for most forms of post-school qualification and, in addition, they can be used by employers offering apprenticeship as a screening device, with higher school qualifications presumed to indicate greater suitability for an apprenticeship, and cohort matters because of the changing context in which qualifications are obtained and used (e.g., Lohmann and Ferger 2014 ). Clearly, other factors are likely to be involved in educational poverty (though the literature on what these may be is not very detailed), but given the need, for analytical reasons, to restrict the number of factors, I am concentrating here on ones of particular theoretical interest.

2 Challenges

2.1 conceptual issues, 2.1.1 material versus educational poverty.

Poverty, as noted in the Introduction, is commonly understood to refer to material poverty, and I therefore begin by discussing the relationship between material and educational poverty, noting similarities and differences. Peter Townsend, the renowned scholar in the field, describes poverty thus: “Individuals, families and groups in the population can be said to be in poverty when they lack the resources to obtain the type of diet, participate in the activities and have the living conditions and the amenities which are customary, or at least widely encouraged or approved, in the societies to which they belong. Their resources are so seriously below those commanded by the average family that they are in effect excluded from ordinary living patterns, customs and activities.” (Townsend 1979 , p.31) Clearly, material poverty affects nearly all spheres of life (including, of course, education as part of a reciprocal relationship: children growing up in poverty are less likely to obtain a high level of education, and individuals with low levels of education are more likely to experience poverty because of their greater difficulties in obtaining adequately-paid work). As I noted in the Introduction, insofar as educational status affects an individual’s opportunities in the labour market, educational poverty can also be expected to affect a wide range of areas of life, restricting societal participation in a variety of ways.

One feature of material poverty is that it is not always stable. Some individuals move in and out of poverty, for example because they lose and find work repeatedly. In fact, Townsend ( 1979 , pp.56/57) notes that the proportion of the population who are always poor is smaller than that of those who experience occasional spells of poverty, but who do not remain poor permanently. In addition, many more people live “under the constant threat of poverty and regard some of the resources flowing to them, or available to them, as undependable” (p. 57). Footnote 3 By contrast, educational resources are likely to be more stable. Once someone obtains a qualification, they will not lose it again, it remains linked to the person. While it is possible to move out of educational poverty by gaining qualifications later in life, these then cannot be lost either. However, relative to the demands of the labour market, qualifications may decrease in value over an individual’s lifetime: a level of qualification which would have been deemed sufficient at the beginning of someone’s working life may later on be considered insufficient with regard to the changing demands of the labour market. In that sense, the person would become educationally poor over time, but this would be a more gradual process compared to the possible fluctuations described by Townsend in relation to material poverty. Footnote 4 In a similar way, what would count as educationally not poor for parents might be seen as educationally poor for their children.

Another obvious difference between material and educational poverty is that it is perfectly possible to transfer money to people who are considered unacceptably poor (political will and availability of funds permitting, though given individuals’ life situations, the ameliorating effects of such transfers cannot be guaranteed). But it is not possible simply to transfer “education” onto people who have been unable to achieve some minimum standard (at least not legitimately). It is possible to implement educational programmes to allow them to catch up, but with no guarantee of success.

2.1.2 Relative versus absolute educational poverty

Rowntree (quoted in Townsend 1979 , p.33) defines families whose “total earnings are insufficient to obtain the minimum necessaries for the maintenance of merely physical efficiency as being in primary poverty”. Clearly, this describes a state of deprivation which would be considered as poverty regardless of historical period, society or political context, in other words, it is an absolute conceptualisation of poverty. Townsend (and others), however, does not agree that there is such a thing as absolute poverty. Instead, he goes on to show that the “minimum necessaries” can only ever be determined relative to the societal standard relevant at the time, coming to the conclusion that “… definitions which are based on some conception of ‘absolute’ deprivation disintegrate upon close and sustained examination and deserve to be abandoned. … In fact, people's needs even for food are conditioned by the society in which they live and to which they belong, and just as needs differ in different societies so they differ in different periods of the evolution of single societies. Any conception of poverty as ‘absolute’ is therefore inappropriate and misleading” (p. 38). Footnote 5 We can see a parallel with educational poverty: illiteracy would clearly seem to qualify as a definition of absolute educational poverty, as would a complete absence of qualifications. However, there were historical periods during which illiteracy would not have prevented an individual from participation in normal societal activities, and a lack of formal qualifications certainly would not have done so, so illiterate individuals and those lacking formal qualifications would not have been considered educationally poor (in fact, the concept itself would have been meaningless). Furthermore, the phenomenon of “illiteracy” can be discussed as illiteracy, an alternative conceptualisation as “educational poverty” is not needed. On the other hand, in many societies today it is perfectly possible to have basic literacy and even some educational certificates and still be considered educationally poor. It seems, then, that Townsend’s concerns re absolute material poverty apply equally to the concept of educational poverty which has to be defined relative to the historical period and the societal context in which the individual lives.

In introducing the concept of educational poverty, Allmendinger ( 1999 ) nevertheless takes up the distinction between absolute and relative poverty, defining absolute minimum standards of educational qualifications for each country under study, with those falling below this standard considered educationally poor. Footnote 6 She then defines relative educational poverty by referring to the distribution of educational certificates in the relevant country or society. Blossfeld et al. ( 2019 ), drawing on Allmendinger, also distinguish between absolute and relative educational poverty, though their empirical analysis based on NEPS data only considers absolute educational poverty. According to Quenzel and Hurrelmann ( 2019b ), this is a common way of proceeding, with many scholars discussing the conceptual difference between absolute and relative poverty, but then ignoring the distinction in their empirical analyses.

The fact that the distribution of resources (for material poverty) or educational certificates (for educational poverty) is employed as a standard against which relative poverty may be defined shows the connection between inequality and poverty, since inequality is also assessed by referring to the distribution of relevant resources. However, a large amount of inequality is not in itself an indicator of a large amount of poverty, since a few very rich individuals at the top end of the distribution can co-exist with individuals at the bottom end of the scale who have the resources to lead a way of life which is much more restricted, but not necessarily deprived in the sense described by Townsend. The difference between material poverty and material inequality does not arise so much from a difference in empirically demonstrable phenomena, but from the angle from which the issue is viewed: inequality focuses on distribution, whereas (relative) poverty is defined against a standard of behaviour (such as the tea drinking example offered by Townsend, see footnote 5 ). The latter of course partly depends on the distribution of resources—what is considered a normal standard of behaviour is linked to whether people have the resources to enable them to act on this standard—but it can be expected to be more stable since temporary changes in circumstances would not immediately alter such a behavioural standard. Turning to education, Lohmann and Ferger ( 2014 ) argue that the difference in focus between inequality and poverty is that “research on educational inequalities […] is primarily concerned with inequalities of opportunity”, while “research on educational poverty focuses on inequalities of condition” (p. 1).

Finally, in the context of a discussion of the relative position of individuals, whether regarding their material or immaterial resources such as educational certificates, it is important to acknowledge existing work in this area, especially that by Fred Hirsch ( 1976 ) on positional goods and Ronald Dore ( 1976 ) on qualifications inflation. Hirsch analyses the way in which the value of certain material as well as immaterial goods depends at least partly on how many other people have access (or not) to the same goods. An example is driving a car: if just one person drives their car, they will get to their destination more quickly than if they used slower means of transport, but if everybody drives, there will be congestion, slowing everybody down. Hirsch also discusses education, where the value of credentials partly depends on the number of people holding the same credentials, given the use of credentials as a screening device. Dore’s entire focus is on educational credentials. He demonstrates and discusses, amongst other things, how a surplus of individuals with a certain level of qualification against a background of a shortage of jobs at the relevant level can change the educational requirements for jobs: even if the demands of the job itself do not change, an employer may well demand higher levels of qualifications from applicants simply to be able to select candidates from a large pool of applicants. Clearly, this analysis matters for the exploration of educational poverty: what Dore describes can happen at any level, including that of the least qualified individuals who may see their employment opportunities diminish with rising qualifications among their competitors. Thus, they are being rendered (relatively) educationally poor without a change in their own qualifications.

2.2 Empirical issues

2.2.1 data: national educational panel study (neps).

Since I am going to illustrate some of the conceptual points made in the previous section by drawing on empirical examples, I first describe briefly the data I employ throughout the paper. The data come from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS): Starting Cohort Adults, https://doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC6:11.0.0 . From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data was collected as part of the Framework Program for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). As of 2014, NEPS is carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg in cooperation with a nationwide network (see also Blossfeld and Roßbach 2019 ). Its aim is to collect longitudinal data on all aspects of education in formal and informal contexts, covering certificates as well as competences, and enabling researchers to investigate causes and consequences of educational outcomes. Data are collected in six cohorts, covering respondents at birth, at the start of nursery, in school years 5 and 9, at the start of university, and as adults. General data collection started in 2011, with new waves added every 1 or 2 years. For the adult cohort, on which the present paper draws, data collection actually started as early as 2007, and the data include, amongst other things, retrospective information on educational experiences and data on parents’ educational and occupational statuses. The present paper uses data on respondents with no missing data on respondent’s education, joint parental education and joint parental class, n = 15,413. Footnote 7

2.2.2 The relationship between cognitive ability and educational certificates

Up to now, the discussion of educational poverty has centred on poverty of certificates, since certificates are what employers usually draw on in selecting employees. Given that a large part of the effects of educational poverty is mediated by labour market experiences, this is clearly an important aspect of educational poverty. It is also relatively easy to measure. However, attention should also be paid to cognitive ability and competences, since it seems plausible that they can affect the same outcomes, i.e. labour market opportunities, health, and family. Indeed, a number of researchers discuss both poverty of certificates and poverty of competences in their work on educational poverty (e.g., Blossfeld et al. 2019 ; Lohmann and Ferger 2014 ; Quenzel and Hurrelmann 2019b ; Solga 2011 ). The NEPS data contain a good range of competence measures; however, the difficulty is that these were obtained in adulthood, well after educational certificates were obtained (or not). But competences affect which certificates are obtained, rather than the other way round which makes the adult cohort NEPS data Footnote 8 unsuitable for investigating this relationship. In principle, it is possible to analyse the role of poverty of competences for, say, labour market outcomes, but given that such outcomes are likely to be at least equally strongly affected by certificates, this makes the analysis of the role of competences difficult in practice because the two measures are so closely intertwined. In addition, some attention will need to be paid to the mechanism by which competences can have effects on people’s experiences: in the labour market, a prospective employer does not usually have access to someone’s performance on a cognitive or competence test, so they rely on certificates as a proxy for competence.

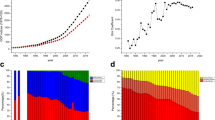

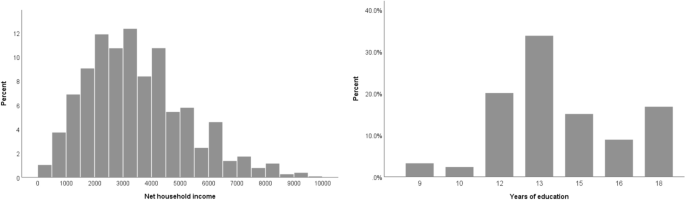

2.2.3 Measurement

The problem described in the previous paragraph is one where, in principle, it is possible to collect the data necessary to address it. In what follows, the nature of the problem lies in the nature of the measure rather than the process of data collection: educational poverty, understood as a shortage of qualifications so severe that it restricts societal participation, cannot be measured in the same way as material poverty. The main basis for measuring material poverty is income or resources in the form of money, with non-monetary resources such as benefits in kind sometimes taken into consideration. Money is easily measured on an interval scale. Level of education, Footnote 9 by contrast, is frequently indicated either by years of education or by highest qualification obtained. The former is not necessarily very helpful especially in systems with a high degree of educational stratification, since the type of qualification achieved is more meaningful than the time taken to achieve it. If anything, taking a greater number of years to achieve a certain qualification may actually be interpreted negatively compared with someone who takes a shorter period of time to achieve the same formal level, so using years of education as an indicator of educational achievement would be counterproductive. But even in systems with a low degree of stratification, years of education is highly correlated with level of education, thus not adding much extra information. At first glance, years of education appear to be measurable on an interval scale, but the range is very restricted, the distribution uneven, and the meaning of one additional year of education is not the same at each point of the scale. Table 1 and Fig. 1 illustrate the differences between income and years of education, two measures used to indicate material and educational poverty respectively, using NEPS data. It can be seen that, indeed, while using an interval scale appears appropriate for measuring income, years of education has only seven values and a concentration of the majority of cases in just two of them, 12 and 13. It also has a far smaller range than the income scale.

Graphical display of income and years of education

Highest qualification obtained, by contrast, is measured on an ordinal scale. It has the advantage of being relatively straightforward to measure and to interpret, at least by people familiar with the relevant educational system, but a mean cannot be calculated in a meaningful way (though mode and median are viable alternative measures of central tendency). Instead, simple frequencies and percentages of individuals in the different ordered categories form the key measures of interest, as in Table 2 .

The German qualifications are listed in Table 2 in ascending order of status. Hauptschule is the most basic form of school in the German tripartite system, offering a qualification which allows the recipient to enter vocational training for mostly manual trades. Mittlere Reife is the qualification offered by the intermediate school type of Realschule, suitable for most forms of vocational training. Footnote 10

These different forms and levels of measurement have implications for the operationalisation of concepts of interest, as I discuss in the next section.

2.2.4 Operationalisation

With respect to relative material poverty, there appear to be two—related and not entirely distinct—ways of operationalising the concept. One is fairly widespread. It relies on income distribution and defines a poverty line which is some percentage (50 or 60 percent) of the median income. Anyone below this line is considered poor. The other way relies on substantive criteria which describe the situation of someone living in relative poverty. Townsend describes in some detail relevant considerations in deciding upon a standard which separates (relatively) materially poor from (relatively) non-poor individuals, and it becomes clear that, while he does discuss income-based definitions, income alone cannot form the basis of a definition of material poverty. Instead, societal norms define obligations people are expected to meet. There is no single criterion which determines poverty status, instead, there is a “pattern of non-observance [of social customs which] may be conditioned by severe lack of resources” (p. 57). Thus, operationalising poverty solely based on income distribution is potentially misleading because it may not capture actual differences in the experience of living conditions. Using a poverty line based on the median income to determine whether or not someone is experiencing poverty has the effect of their being designated poor (or not) with rising and falling average incomes, even if neither their own incomes change nor, more importantly, their situation in terms of what they can afford or whether they can participate in normal societal activities (see also footnote 3) (for the problems associated with using a single dimension to create an indicator of a complex concept such as poverty, see also Berg-Schlosser 2018 ). The advantage, however, of an income-based poverty line is that it is fairly straightforward to measure and, despite the reservations noted here, it is likely to capture fairly accurately the situation experienced by poor people in the sense that normal participation in socially expected and accepted activities is likely to be difficult if not impossible given an income below the poverty line. In addition, what are socially expected and accepted activities will at least partly depend on what most people are able to afford, thus income distribution is relevant in that respect. However, as an alternative to a solely distribution-based measure, it is possible to construct a list of goods and activities, along with their cost, which together constitute a range of “normal” societal activities. Their combined cost would constitute a criterion-based poverty line, in other words, a threshold below which an individual or household would be considered relatively poor.

What are the implications for the operationalisation of educational poverty? Absolute educational poverty seems impossible to operationalise given that education always has its effects in social and historical context. Allmendinger ( 1999 ) suggests that everyone having less education (indicated through certificates) than the population average might be defined as educationally (relatively) poor, and this, according to her, would suggest that all those in the lowest quartile or quintile of the distribution would fulfil this criterion. However, using such a distribution-based measure would ignore substantive criteria such as those suggested above in relation to material poverty. In addition, Table 2 shows that the distribution of certificates can be very uneven, making it difficult to define “the average of the population” or a clear cut-off point. Footnote 11 It would seem more appropriate to consider substantive criteria in defining educational poverty, taking account of what certificates are needed to participate in normal social activities, including the labour market which is likely to be the sphere of life in which education has the greatest impact.

The method used for the analysis shown below is Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) in its multi-value (mvQCA) variant. I do not have space here to fully explain this method, but the references given in this section should be helpful to readers unfamiliar with it. The interpretation of the findings as I present them will also help the reader understand the method.

Briefly, then, QCA was developed by Charles Ragin (Ragin 1987 , 2000 , 2008 , see also, e.g., Rihoux and Ragin 2009 ; Rihoux 2020 ). Based on set theory and Boolean algebra, it offers a way of systematically analysing conjunctions of factors as potential necessary and sufficient conditions for an outcome. Data are arranged in a truth table which shows all the possible combinations of values on the conditions under study and their relationship with the outcome. This truth table forms the basis for Boolean minimisation which is a way of logically summarising all the possible combinations of factors leading to the outcome. Ragin developed crisp and fuzzy variants of QCA, with the former employing dichotomous variables indicating full membership or non-membership in a set, and the latter allowing partial membership of a set. Lasse Cronqvist introduced another QCA variant: in multi-value QCA (mvQCA) crisp sets with more than two categories may be used (Cronqvist 2003 ; Cronqvist and Berg-Schlosser 2009 ). Originally developed for the use with small to medium n, QCA has since been usefully employed with large n (e.g., Cooper 2005 ; Glaesser and Cooper 2011 ; Greckhamer et al. 2013 ; Ragin 2006 ; Ragin and Fiss 2017 ). QCA’s strengths are that it enables the researcher to analyse systematically complex connections amongst factors, allowing for multiple pathways to the outcome and investigating the effects of combinations of factors. I use the mvQCA variant in this paper because it is the most suitable for the type of data I analyse: since some of my factors have more than two categories, crisp set QCA would not be suitable (it is possible to employ dummies, but this makes the analyses clumsy and the findings harder to interpret). In order to use fsQCA, on the other hand, I would have had to decide how to calibrate the school qualification measure. Any decision taken in calibration affects the results, whereas the categories used in the mvQCA have substantive meanings which are straightforwardly interpretable. The analysis was performed using the R package QCApro (Thiem 2018 ). Footnote 12

4 Relative educational poverty: some empirical findings

Clearly, it is important to consider the relative nature of the value of educational certificates despite the challenges associated with operationalising relative educational poverty discussed above. As we have seen, this value changes over time: on the one hand, technological change leads to a change in the structure of the labour market in modern societies, so that there will be a demand for more highly skilled workers, on the other hand, educational expansion has produced an oversupply of candidates with high formal qualifications, a development which leads to lowly qualified candidates being rejected for jobs which previously had been carried out perfectly competently by workers with this level of qualification (Dore 1976 ). Taken together, these two developments lead to a devaluing of basic qualifications in the labour market.

4.1 Descriptive results

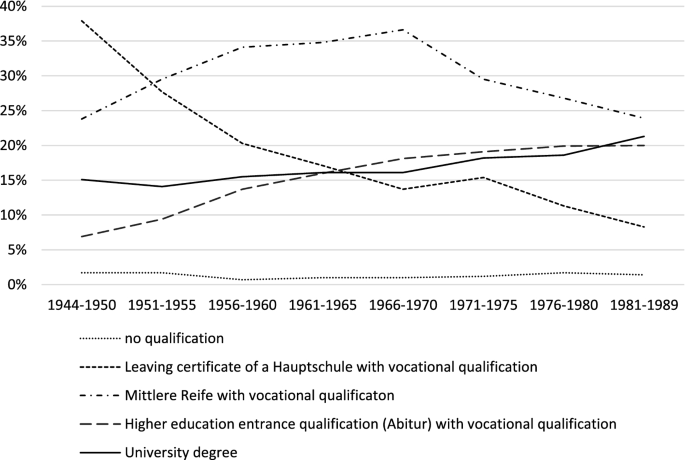

Qualifications inflation is evident in the NEPS data when considering changes over eight cohorts, ranging from those born between 1944 and 1950 to those born between 1981 and 1989: Hauptschulabschluss (HS) with vocational qualification was the most common qualification in the earlier cohorts. The proportion of respondents with this qualification then fell from 38% (1944–1950) to 8.3% (1981–1989). The combination Abitur (i.e., the Higher Education entrance qualification) with vocational qualification went from fairly uncommon (6.9% for the 1944–1950 cohort) to one held by a fifth of respondents (20.0% for the 1981–1989 cohort). Finally, having a university degree went from a qualification held by 15.1% of the 1944–1950 cohort to being the second most common one at 21.3% (only surpassed by Mittlere Reife with vocational qualification at 23.9%) for the 1981–1989 cohort. Over time, the proportions of respondents with Hauptschulabschluss who have remained without vocational qualification have increased, from 9.9% in the oldest cohort to 29.2% in the youngest. Figure 2 summarises some of these developments, and it is worth noting that what has sometimes been defined as absolute educational poverty—the absence of any qualification—has remained fairly constant over time. This is represented by the dotted line in Fig. 2 .

Changes over time in highest qualifications achieved

The two developments taken together—the seemingly greater risk for Hauptschulabschluss holders of remaining without a vocational qualification and the increasing number of Abitur holders who obtain vocational qualifications—may largely reflect changes in the composition of these groups. Presumably, Hauptschulabschluss is increasingly only obtained by individuals who struggle in some way—whether academically or in life more generally—so that they are unable or unwilling to gain a vocational qualification. Employers who can offer apprenticeships are more likely to offer their places to Mittlere Reife or Abitur holders given that there are enough candidates with these higher levels of qualifications. This may be because they use qualification as a simple screening device when faced with a large number of applicants, and/or because they fear that the group of Hauptschulabschluss holders is indeed negatively selected for academic ability and/or motivation (see Solga 2011 , p.430, who also discusses such developments).