Want to Get your Dissertation Accepted?

Discover how we've helped doctoral students complete their dissertations and advance their academic careers!

Join 200+ Graduated Students

Get Your Dissertation Accepted On Your Next Submission

Get customized coaching for:.

- Crafting your proposal,

- Collecting and analyzing your data, or

- Preparing your defense.

Trapped in dissertation revisions?

How to write a literature review for a dissertation, published by steve tippins on july 5, 2019 july 5, 2019.

Last Updated on: 22nd May 2024, 04:06 am

Chapter 2 of your dissertation, your literature review, may be the longest chapter. It is not uncommon to see lit reviews in the 40- to 60-page range. That may seem daunting, but I contend that the literature review could be the easiest part of your dissertation.

It is also foundational. To be able to select an appropriate research topic and craft expert research questions, you’ll need to know what has already been discovered and what mysteries remain.

Remember, your degree is meant to indicate your achieving the highest level of expertise in your area of study. The lit review for your dissertation could very well form the foundation for your entire career.

In this article, I’ll give you detailed instructions for how to write the literature review of your dissertation without stress. I’ll also provide a sample outline.

When to Write the Literature Review for your Dissertation

Though technically Chapter 2 of your dissertation, many students write their literature review first. Why? Because having a solid foundation in the research informs the way you write Chapter 1.

Also, when writing Chapter 1, you’ll need to become familiar with the literature anyway. It only makes sense to write down what you learn to form the start of your lit review.

Some institutions even encourage students to write Chapter 2 first. But it’s important to talk with your Chair to see what he or she recommends.

How Long Should a Literature Review Be?

There is no set length for a literature review. The length largely depends on your area of study. However, I have found that most literature reviews are between 40-60 pages.

If your literature review is significantly shorter than that, ask yourself (a) if there is other relevant research that you have not explored, or (b) if you have provided enough of a discussion about the information you did explore.

Preparing to Write the Literature Review for your Dissertation

Step 1. Search Using Key Terms

Most people start their lit review searching appropriate databases using key terms. For example, if you’re researching the impact of social media on adult learning, some key terms you would use at the start of your search would be adult learning, androgogy, social media, and “learning and social media” together.

If your topic was the impact of natural disasters on stock prices, then you would need to explore all types of natural disasters, other market factors that impact stock prices, and the methodologies used.

You can save time by skimming the abstracts first; if the article is not what you thought it might be you can move on quickly.

Once you start finding articles using key terms, two different things will usually happen: you will find new key terms to search, and the articles will lead you directly to other articles related to what you are studying. It becomes like a snowball rolling downhill.

Note that the vast majority of your sources should be articles from peer-reviewed journals.

Step 2. Immerse Yourself in the Literature

When people ask what they should do first for their dissertation the most common answer is “immerse yourself in the literature.” What exactly does this mean?

Think of this stage as a trip into the quiet heart of the forest. Your questions are at the center of this journey, and you’ll need to help your reader understand which trees — which particular theories, studies, and lines of reasoning — got you there.

There are lots of trees in this particular forest, but there are particular trees that mark your path. What makes them unique? What about J’s methodology made you choose that study over Y’s? How did B’s argument triumph over A’s, thus leading you to C’s theory?

You are showing your reader that you’ve fully explored the forest of your topic and chosen this particular path, leading to these particular questions (your research questions), for these particular reasons.

Step 3. Consider Gaps in the Research

The gaps in the research are where current knowledge ends and your study begins. In order to build a case for doing your study, you must demonstrate that it:

- Is worthy of doctoral-level research, and

- Has not already been studied

Defining the gaps in the literature should help accomplish both aims. Identifying studies on related topics helps make the case that your study is relevant, since other researchers have conducted related studies.

And showing where they fall short will help make the case that your study is the appropriate next step. Pay special attention to the recommendations for further research that the authors of studies make.

Step 4. Organize What You Find

As you find articles, you will have to come up with methods to organize what you find.

Whether you find a computer-based system (three popular systems are Zotero, endNote, and Mendeley) or some sort of manual system such as index cards, you need to devise a method where you can easily group your references by subject and methodology and find what you are looking for when you need it. It is very frustrating to know you have found an article that supports a point that you are trying to make, but you can’t find the article!

One way to save time and keep things organized is to cut and paste relevant quotations (and their references) under topic headings. You’ll be able to rearrange and do some paraphrasing later, but if you’ve got the quotations and the citations that are important to you already embedded in your text, you’ll have an easier time of it.

If you choose this method, be sure to list the whole reference on the reference/bibliography page so you don’t have to do this page separately later. Some students use Scrivener for this purpose, as it offers a clear way to view and easily navigate to all sections of a written document.

Need help with your literature review? Take a look at my dissertation coaching and dissertation editing services.

How to Write the Literature Review for your Dissertation

Once you have gathered a sufficient number of pertinent references, you’ll need to string them together in a way that tells your story. Explain what previous researchers have done by telling the story of how knowledge on this topic has evolved. Here, you are laying the support for your topic and showing that your research questions need to be answered. Let’s dive into how to actually write your dissertation’s literature review.

Step 1. Create an Outline

If you’ve created a system for keeping track of the sources you’ve found, you likely already have the bones of an outline. Even if not, it may be relatively easy to see how to organize it all. The main thing to remember is, keep it simple and don’t overthink it. There are several ways to organize your dissertation’s literature review, and I’ll discuss some of the most common below:

- By topic. This is by far the most common approach, and it’s the one I recommend unless there’s a clear reason to do otherwise. Topics are things like servant leadership, transformational leadership, employee retention, organizational knowledge, etc. Organizing by topic is fairly simple and it makes sense to the reader.

- Chronologically. In some cases, it makes sense to tell the story of how knowledge and thought on a given subject have evolved. In this case, sub-sections may indicate important advances or contributions.

- By methodology. Some students organize their literature review by the methodology of the studies. This makes sense when conducting a mixed-methods study, and in cases where methodology is at the forefront.

Step 2. Write the Paragraphs

I said earlier that I thought the lit review was the easiest part to write, and here is why. When you write about the findings of others, you can do it in small, discrete time periods. You go down the path awhile, then you rest.

Once you have many small pieces written, you can then piece them together. You can write each piece without worrying about the flow of the chapter; that can all be done at the end when you put the jigsaw puzzle of references together.

Step 3. Analyze

The literature review is a demonstration of your ability to think critically about existing research and build meaningfully on it in your study. Avoid simply stating what other researchers said. Find the relationships between studies, note where researchers agree and disagree, and– especiallyy–relate it to your own study.

Pay special attention to controversial issues, and don’t be afraid to give space to researchers who you disagree with. Including differing opinions will only strengthen the credibility of your study, as it demonstrates that you’re willing to consider all sides.

Step 4. Justify the Methodology

In addition to discussing studies related to your topic, include some background on the methodology you will be using. This is especially important if you are using a new or little-used methodology, as it may help get committee members onboard.

I have seen several students get slowed down in the process trying to get committees to buy into the planned methodology. Providing references and samples of where the planned methodology has been used makes the job of the committee easier, and it will also help your reader trust the outcomes.

Advice for Writing Your Dissertation’s Literature Review

- Remember to relate each section back to your study (your Problem and Purpose statements).

- Discuss conflicting findings or theoretical positions. Avoid the temptation to only include research that you agree with.

- Sections should flow together, the way sections of a chapter in a nonfiction book do. They should relate to each other and relate back to the purpose of your study. Avoid making each section an island.

- Discuss how each study or theory relates to the others in that section.

- Avoid relying on direct quotes–you should demonstrate that you understand the study and can describe it accurately.

Sample Outline of a Literature Review (Dissertation Chapter 2)

Here is a sample outline, with some brief instructions. Note that your institution probably has specific requirements for the structure of your dissertation’s literature review. But to give you a general idea, I’ve provided a sample outline of a dissertation ’s literature review here.

- Introduction

- State the problem and the purpose of the study

- Give a brief synopsis of literature that establishes the relevance of the problem

- Very briefly summarize the major sections of your chapter

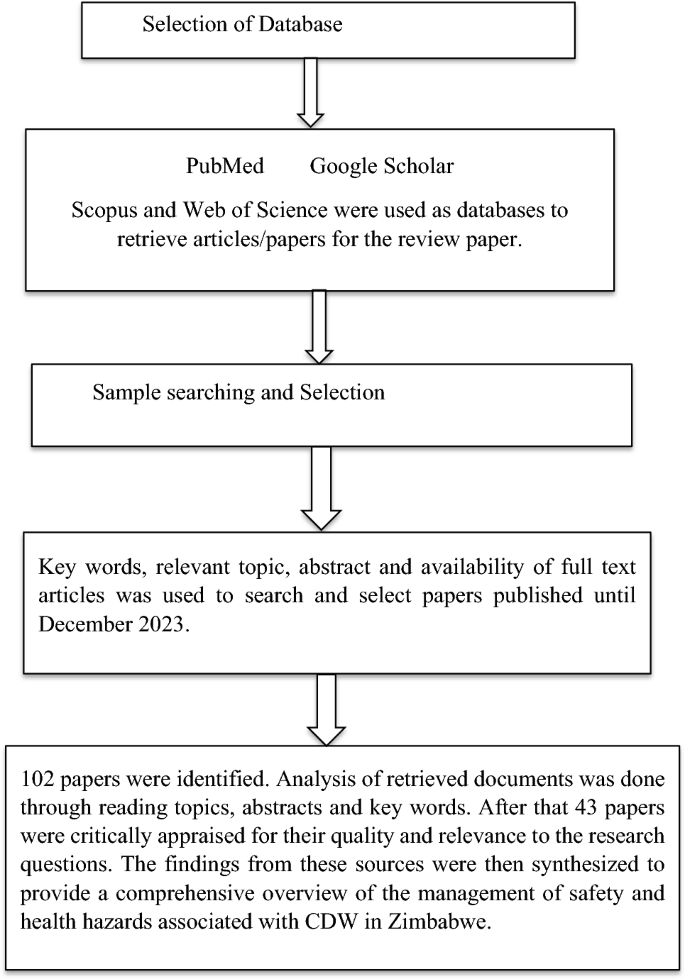

Documentation of Literature Search Strategy

- Include the library databases and search engines you used

- List the key terms you used

- Describe the scope (qualitative) or iterative process (quantitative). Explain why and based on what criteria you selected the articles you did.

Literature Review (this is the meat of the chapter)

- Sub-topic a

- Sub-topic b

- Sub-topic c

See below for an example of what this outline might look like.

How to Write a Literature Review for a Dissertation: An Example

Let’s take an example that will make the organization, and the outline, a little bit more clear. Below, I’ll fill out the example outline based on the topics discussed.

If your questions have to do with the impact of the servant leadership style of management on employee retention, you may want to saunter down the path of servant leadership first, learning of its origins , its principles , its values , and its methods .

You’ll note the different ways the style is employed based on different practitioners’ perspectives or circumstances and how studies have evaluated these differences. Researchers will draw conclusions that you’ll want to note, and these conclusions will lead you to your next questions.

Next, you’ll want to wander into the territory of management styles to discover their impact on employee retention in general. Does management style really make a difference in employee retention, and if so, what factors, exactly, make this impact?

Employee retention is its own path, and you’ll discover factors, internal and external, that encourage people to stick with their jobs.

You’ll likely find paradoxes and contradictions in here that just bring up more questions. How do internal and external factors mix and match? How can employers influence both psychology and context ? Is it of benefit to try and do so?

At first, these three paths seem somewhat remote from one another, but your interest is where the three converge. Taking the lit review section by section like this before tying it all together will not only make it more manageable to write but will help you lead your reader down the same path you traveled, thereby increasing clarity.

Example Outline

So the main sections of your literature review might look something like this:

- Literature Search Strategy

- Conceptual Framework or Theoretical Foundation

- Literature that supports your methodology

- Origins, principles, values

- Seminal research

- Current research

- Management Styles’ Impact on employee retention

- Internal Factors

- External Factors

- Influencing psychology and context

- Summary and Conclusion

Final Thoughts on Writing Your Dissertation’s Chapter 2

The lit review provides the foundation for your study and perhaps for your career. Spend time reading and getting lost in the literature. The “aha” moments will come where you see how everything fits together.

At that point, it will just be a matter of clearly recording and tracing your path, keeping your references organized, and conveying clearly how your research questions are a natural evolution of previous work that has been done.

PS. If you’re struggling with your literature review, I can help. I offer dissertation coaching and editing services.

Steve Tippins

Steve Tippins, PhD, has thrived in academia for over thirty years. He continues to love teaching in addition to coaching recent PhD graduates as well as students writing their dissertations. Learn more about his dissertation coaching and career coaching services. Book a Free Consultation with Steve Tippins

Related Posts

Dissertation

Dissertation memes.

Sometimes you can’t dissertate anymore and you just need to meme. Don’t worry, I’ve got you. Here are some of my favorite dissertation memes that I’ve seen lately. My Favorite Dissertation Memes For when you Read more…

Surviving Post Dissertation Stress Disorder

The process of earning a doctorate can be long and stressful – and for some people, it can even be traumatic. This may be hard for those who haven’t been through a doctoral program to Read more…

PhD by Publication

PhD by publication, also known as “PhD by portfolio” or “PhD by published works,” is a relatively new route to completing your dissertation requirements for your doctoral degree. In the traditional dissertation route, you have Read more…

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

AP ® Research Handbook

Chapter 2 literature review.

List resources for conducting literature review. Show example of literature review with inline citations. Show ways to keep track of sources for bibliography.

- contains example literature reviews from political science, philosophy, and chemistry.

Consider using a reference management system like Mendeley to organize your sources as you conduct your literature review. In fact, Mendeley has a Literature Search function, so you can manage sources and conduct literature reviews at the same time. See the Bibliography Management Section for more information on managing sources.

Databases for Literature Reviews

- Browse by subjects in the humanities and sciences. This can be your starting point if you have not developed a research topic.

- Open-access journal articles in fields such as mathematics, statistics, economics, physics, quantitative biology, quantiative finance, and electrical engineering

- arXiv to BibTex : Outputs automated citations in BibTeX and other formats by typing the arXiv number of the article. For instance, just type in 1905.03758 into the search engine if the article is labeled arXiv: 1905.03758.

- Alternatively, use Mendeley Web Importer to import article into Mendeley Desktop for automated citation outputs.

- Download Mendeley Desktop and register for a free account. Mendeley Desktop syncs with your online Mendeley account, but the literature search is currently only available in the desktop version.

- Mendeley is primarly a reference managements software, so you can organize your citations as you conduct your literature review.

- Search engine with the world’s largest collectin of open-access research papers.

- For batch searches of metadata and full texts, you may consider requesting a free API key to use the Core API .

- Search for content, authors, collections, and journals in the advanced search , where you have the option to search by discipline or key word.

- Search for articles in clincial sciences, biochemistry, public health, physical chemistry, and materials engineering.

- Search open-access journals and dissertations. Note that dissertations can vary in quality, since they have not gone through peer review.

- AP Research students should have access to a free EBSCO account from the AP Capstone program.

- Many of the social science articles are free access.

- Search for articles related to to education research.

- The search engine includes the open to search for full-text articles.

- Index of major computer science publications.

- Option to search for open-access articles.

- Search for journal articles, working papers, and conference papers in economics and business.

- You can sign up for a free MyJSTOR account to access up to six articles a month for free.

- This may be helpful for accessing articles that are not open access.

Tips for Accessing Paywalled Articles

- Search for the author’s website. Many researchers have draft manuscripts on their websites or research profiles on sites such as ResearchGate .

- Consult your school’s research librarian for other ways to access the article.

- Send the author an e-mail to request for a digital copy of the article. You should provide context in the e-mail request by including a brief description of your AP Research project and its relevance and connection to the author’s article.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

CHAPTER 2 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE AND STUDIES

Related Papers

Ana Liza Sigue

Motoky Hayakawa

Rene E Ofreneo

... Rene E. Ofreneo University of the Philippines School of Labor and Industrial Relations ... Erickson, Christopher L.; Kuruvilla, Sarosh ; Ofreneo, Rene E.; and Ortiz, Maria Asuncion , "Recent Developments in Employment Relations in the Philippines" (2001). ...

Lucita Lazo

This book begins by looking at the status of women in Filipino society and their place in the general socio-economic situation. It continues with sections on education and training in the Philippines and work and training. The next section reviews the constraints to women’s participation in training. In the summary the author gives a general overview of the situation of women and opportunities for work and training in the Philippines and offers some practical suggestions for the enhancement of women’s training and development.

EducationInvestor Global

Tony Mitchener

Rosalyn Eder

In this article, I examine the role of CHED and the Technical Panels (TPs) in the “production” of the globally competitive Filipina/o worker. For this paper, I draw on relevant literature on the topic and take nurse education, which is rooted in the colonial system established during the US-American occupation, as an example of how CHED and the TPs could be more linked to labor migration. I use the colonial difference - a space that offers critical insights and interpretation - to illustrate how coloniality remains hidden under the cloak of modernity. Link to the article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2016.1214913

Asia Pacific Journal of Management and Sustainable Development ISSN 2782-8557(Print)

Ryan O Tayco , Pio Supat

This study aims to determine the employability of the Negros Oriental State University graduates from 2016 to 2020. Employability is measured using different dimensions-from the graduates' side including the perspectives of the employers. A total of 1, 056 NORSU graduates and 68 employers locally and abroad answered the questionnaire through online and offline survey methods. Basic statistics were used and simple linear regression was also used to estimate the relationship between manifestations of respondents in NORSU VMGOs and the job performance as perceived by the employers. Most of the respondents in the study are presently employed and work locally. Many of them stay and accept the job because of the salaries and benefits they received, a career challenge, and related to the course they have taken in college. The study shows that the curriculum used and competencies learned by the NORSU graduates are relevant to their job. Competencies such as communication skills, human relations skills, critical thinking skills, and problem-solving skills are found to be useful by the respondents. It is found that the manifestation of the respondents is very high and homogenous. The same can be said with job performance as perceived by employers in terms of attitudes and values, skills and competencies, and knowledge. Furthermore, job performance and the manifestation of NORSU VMGOs have a significant relationship. That is, those respondents who have higher job performance in terms of attitude and values, skills and competencies, and knowledge have higher manifestations of NORSU VMGOs.

Annals of Tropical Research

Pedro Armenia

Ezekiel Succor

RELATED PAPERS

Juan Manuel Aragüés

Prostaglandins

Charles Serhan

Synergies Espagne

Araceli Gómez-Fernández

Carla Diniz

Arnaldo Azevedo

Patricia Cecilia Gonsales

Chaos, Solitons & Fractals

Arianna Dal forno

PLoS neglected tropical diseases

Mamoudou oulén Diallo

Basil M Al-Hadithi

Human Molecular Genetics

Silvana Santos

Ariel Sarid

Journal of Spinal Disorders

Seth Zeidman

Ivan Juranic

Bruno Raffin

Psicologia para América Latina

Maria Sara DE LIMA DIAS

Bacia do Lis

Joao Teixeira

BMC Infectious Diseases

Ioana Berciu

卡尔加里大学毕业证书办理成绩单购买 加拿大文凭办理卡尔加里大学文凭学位证书

Afyon Kocatepe University Journal of Sciences and Engineering

Psychological Applications and Trends 2019

Maša Vidmar

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Ancillary Asset Data Stewardship and Models (2024)

Chapter: chapter 2 - literature review.

Below is the uncorrected machine-read text of this chapter, intended to provide our own search engines and external engines with highly rich, chapter-representative searchable text of each book. Because it is UNCORRECTED material, please consider the following text as a useful but insufficient proxy for the authoritative book pages.

7  Literature Review This chapter provides an overview of previous work that has been conducted regarding ancillary asset data stewardship and models. The information in this chapter serves as back- ground for the survey questionnaire and for the case examples. 2.1 Transportation Asset Management State DOTs manage and maintain transportation assets in the United States. State DOTs usually prioritize the management of high-visibility, high-value assets such as pavements and bridges. However, transportation systems extend beyond pavement and bridges to include a wide variety of ancillary assets, including but not limited to lighting structures, roadway signs, operations facilities, and technology equipment (AASHTO 2022). In order to manage different transportation assets, state DOTs use a performance-based approach to maintain asset conditions to a desired service level. This is achieved by implementing Transportation Asset Management (TAM) strategies that require the availability of quality inventories, asset condition data, and tools that can support assessment of the impact that different investment levels have on network-wide conditions and in consideration of multiple objectives. Implementing efficient TAM strategies necessitates the existence of well-developed information technology (IT) systems to collect, process, and manage asset data (Allen et al. 2019). State DOTs develop TAMPs as a pivotal point for information about transportation assets and strategies for managing them, as well as for long-term expense forecasts and business management processes. TAMPs are necessary management tools for joining related business stakeholders and business processes in order to better understand and commit to improv- ing asset performance. A state DOTâs TAMP should include at least the following elements (FHWA 2021): (1) A summary listing of the pavement and bridge assets on the National Highway System in the state, including a description of the condition of those assets (2) Asset management objectives and measures (3) Performance gap identification (4) Life-cycle cost and risk management analysis (5) A financial plan (6) Investment strategies Since state DOTs are responsible for managing a variety of assets, they face challenges in how to prioritize their investments in advanced, formal asset management. Building asset management requires that DOTs evaluate different management approaches and determine the organizationâs maturity level for implementing such approaches. AASHTOâs TAM Guide describes three methods for managing highway assets; each process requires additional data C H A P T E R  2

8 Ancillary Asset Data Stewardship and Models input and varied ways to generate and implement the management process. These methods include the following: 1. Reactive Based: Treatment is performed to fix a problem after it has occurred. 2. Interval Based: The asset is treated based on a time or usage basis, regardless of whether it is needed. 3. Condition Based (life-cycle approach): An intervention is selected based on a forecasted condition exceedance interval. Generally, a state DOT will start with a superficial asset management level and will mature toward more holistic and complex asset management to support asset prioritization and decision- making (AASHTO 2022). It is important that state DOTs first develop a list of asset classes in order to facilitate the prioritization process; each asset class should be well-defined (Allen et al. 2019). 2.2 Ancillary Asset Data Management Traditionally, state DOTs have focused on managing pavements and bridges; the availability of asset inventory and condition data for ancillary assets is less common. However, the variability of the assets composing the ancillary transportation asset system and its statewide spread can represent a significant part of the total value of a state DOTâs transportation system. For example, for fiscal year 2021, the Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) was responsible for man- aging a transportation system with a total value of $51 billion, of which bridges accounted for $10 billion (19.6%), pavement accounted for $30 billion (58.8%), and ancillary assets accounted for $11 billion (21.6%) (Ammar, Nassereddine, and Dadi 2022). The need to focus on ancillary asset management was recognized in Akofio-Sowah et al. (2013). Although ancillary assets represent a significant portion of the total value of the trans- portation system managed by a transportation agency, managing this diverse type of assets is challenging. State DOTs often struggle with prioritizing the various ancillary assets and including them in a formal management system (Akofio-Sowah et al. 2013). To overcome this challenge, state DOTs are focusing their efforts to collect the data necessary for managing ancillary assets. However, issues including incomplete inventories, outdated asset conditions, and missing analysis tools that are needed to implement risk-based TAM are often encountered. Some state DOTs have implemented MQA programs to assist maintenance personnel in identifying and prioritizing maintenance requirements and in focusing on ancillary assets. Other state DOTs have taken the approach of including ancillary assets in their TAMPs (Allen et al. 2019). A list of common ancillary assets that state DOTs can include in their TAMPs, as developed by the National Highway Institute, is presented in Table 2-1 (National Highway Institute 2017). The Traffic Management Data Dictionary also provides a list of managed ancillary assets. These assets include traffic networks, closed-circuit television cameras and switches, dynamic message signs, environmental sensor stations, lane closure gates and swing bridges, highway advisory radio and low-power FM stations, lane control signals, ramp meters, traffic detectors, and traffic signals, as well as information on agencies, centers, systems, and users (Institute of Transportation Engineers 2020). The FHWA developed a handbook for including ancillary assets in TAM programs. In that handbook, the authors introduced a seven-step process that agencies can adapt in order to prioritize which assets are incorporated into their TAMPs, including (1) getting organized, (2) selecting criteria, (3) establishing a rating system, (4) establishing relative weights, (5) setting rating values, (6) calculating scores, and (7) developing priority tiers. As a result of implementing this process, each agency will generate its own prioritized list of asset classes that are grouped

Literature Review 9  Functional Area Asset Class Structures (not bridges or otherwise found in the National Bridge Inventory) Drainage Structures Overhead sign and signal Retaining walls (earth retaining structures) Noise barriers Sight barrier High-mast light poles Traffic control and managementâ active devices Signals ITS equipment Network backbone Traffic control and managementâ passive control devices Signs Guardrail Guardrail end treatments Impact attenuator Other barrier systems Drainage systems and environmental mitigation features Drain inlets and outlets Culverts (<20 ft total span)/pipes Ditches Stormwater retention systems Curb and gutter Erosion control Other drains (e.g., underdrain and edge drain) Other safety features Lighting Pavement markings Rockfall Roadside features Sidewalks Curbs Fence Turf Brush control Roadside hazard Landscaping Access ramps Bike paths Other facilities and items Rest areas Weigh stations Parking lots Buildings Fleet Roadside graffiti Roadside litter Table 2-1. Typical highway asset classes. into priority tiers. The handbook recommended that agencies document their prioritization process so that the tiers can be updated to keep track of inventory status, data collection costs, and asset management costs (Allen et al. 2019). NCHRP Project 08-36/Task 114, âTransportation Asset Management for Ancillary Structures,â aimed to provide guidelines on the application of asset management to selected ancillary assets. The contractorâs final report for the project developed an ancillary asset classification hierarchy that can be used as a common starting point for state DOTs in their enterprise approaches to asset management information when establishing inventories of ancillary assets and when devel- oping management systems for these assets. The report presents an asset hierarchy for ancillary assets by organizing ancillary asset classes into the following categories (Rose et al. 2014): ⢠Structures [not bridges or otherwise found in the National Bridge Inventory (NBI)] ⢠Traffic Control & Management â Active Devices ⢠Traffic Control & Management â Passive Devices ⢠Drainage Systems and Environmental Mitigation Features ⢠Other Safety Features ⢠Roadside Features

10 Ancillary Asset Data Stewardship and Models State DOTs are including ancillary assets in their TAMPs and defining different asset manage- ment tiers for various asset groups and asset classes. For example, UDOT developed a three-tier TAM plan; tier one is the most extensive management plan for the highest-value assets. The tiers are described as follows (UDOT 2019): UDOT Tier 1: Performance-based management. Assets in the Tier 1 management level are those of the highest value combined with the highest risk of negative financial impact for poor management. These are assets that are very important to UDOT. Tier 1 management plans include elements such as accurate and sophisticated data collection, set and tracked targets and measures, predictive modeling and risk analysis, and dedicated funding. Assets in Tier 1 include the following: ⢠Pavements ⢠Bridges ⢠Automated traffic management systems devices ⢠Signal devices UDOT Tier 2: Condition-based management. Assets in the Tier 2 management level are those of moderate value and of substantial importance to transportation system operation. These assets have a moderate risk of negative impact for poor management or asset failure. Tier 2 management plans include elements such as accurate data collection, condition targets, and risk assessment that are primarily based on asset failure. Assets in Tier 2 include the following: ⢠Pipe culverts ⢠Signs ⢠Walls ⢠Rumble strips ⢠ADA-compliant ramps, barriers, and pavement markings UDOT Tier 3: Reactive management. Assets in the Tier 3 management level are generally the assets of lowest value and that have the lowest risk of negative impact for poor management or asset failure. Tier 3 management plans include elements such as risk assessment (primarily based on asset failure), general condition analysis, and repair or replacement when the asset is damaged. Assets in Tier 3 include the following: ⢠Cattle guards ⢠Interstate lighting ⢠Fences ⢠Rest areas ⢠Curb gutters ⢠Trails ⢠Bike lanes ⢠Surplus land ⢠At-grade railroad crossings Similarly, the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) developed four criticality tiers to represent the importance of each asset class to the agencyâs mission and to establish the level of resources needed to manage each asset class (MnDOT 2022). MnDOT Tier 1 assets represent a combination of the highest monetary valued assets and assets critical to public safety, mobility, and the economy. Failure of a single asset could lead to an immediate safety risk or impact on the transportation network for an entire region. Assets classified as Tier 1 receive the greatest scrutiny and resources dedicated to inventory and con- dition data collection, investment decision-making, maintenance, and capital investments to provide the highest practical level of service and reliability. Assets in Tier 1 include the following:

Literature Review 11  ⢠Bridges (vehicle bridges >10 ft and tunnels) ⢠Pavements (highway mainline), maintenance (snow and ice winter plow routes) ⢠Facilities (Class 1 rest areas, Class 1 truck stations, office buildings, and salt sheds) ⢠Allied Radio Matrix for Emergency Response structures (ARMER Systemâradio towers, equipment shelters, radio transmission equipment, and facilities). MnDOT Tier 2 assets are typically not as high in value as Tier 1 assets but still represent a significant consequence to public safety for a corridor or municipality should they fail. Resources are therefore dedicated to proactively monitoring and conducting subsequent interventions on Tier 2 assets to prevent unacceptable performance. Asset inventory and condition data are used to identify, prioritize, and deliver maintenance and repair actions to manage these assets cost-effectively throughout their service lives. Assets in Tier 2 include the following: ⢠Bike and pedestrian infrastructure [including ADA-accessible on-street parking, pedestrian curb ramps, signals, and sidewalks as well as bike lanes (not separated) and shared roadways] ⢠Pedestrian, bicycle, and utility bridges ⢠Geotechnical assets including earth retaining systems (gravity, soil nail, soldier pile, sheet pile, reinforced concrete cantilever, mechanically stabilized earth, crib, bin, timber, and other types on the TAM list), reinforced soil slopes, and improved ground MnDOT Tier 3 assets support safety and system performance at their specific locations. Individual failures of these assets can have significant local impacts but are of limited conse- quence to overall network performance. These assets typically benefit from a routine or cyclic replacement either of components or of whole assets to ensure proper performance. Asset inventory data is collected to support the efficient scheduling and delivery of appropriate cyclical work. Additionally, condition data may be collected for some assets in order to comply with mandates (e.g., municipal separate storm sewer systems), to optimize the maintenance and replacement cycles (e.g., sign panels), or both. Assets in Tier 3 include the following: ⢠Bike and pedestrian, including shared-use paths, side paths, and separate bike lanes ⢠Facilities including Class 2 and 3 rest areas, Class 2 and 3 truck stations, brine buildings (service and inspection operations), and weigh stations ⢠Instrumentation systems such as inclinometers, pressure cells, gauges, cabinets, and piezometers ⢠Geotechnical, including (1) special drainage systems such as chimney drains, perforated drains, herringbone drains, geomembrane caps and liners, and trench drains (but not including edge drains); (2) green assets (noxious weeds, deep stormwater tunnels); (3) hydraulic infrastructure such as ponds, infiltration basins, and underground storage; (4) storm sewer pipes and struc- tures; (5) structural pollution control devices; and (6) local road culverts ⢠Maintenance, including Road Weather Information Systems and pavements (such as paved shoulders and low-volume frontage roads) ⢠Structures such as wood noise walls and entrance monuments as well as traffic structuresâ including static sign panels, static panel ground-mounted sign structures, static panel overheads with foundations, and I-beam with static panel sign structures ⢠Roadway lighting and barrier attenuators (crash cushions) ⢠Barriers, including plate-beam end treatments, high-tension cable barriers, and plate-beam barriers ⢠Pavement markings, including messaging and striping MnDOT Tier 4 assets represent a limited risk to the transportation network, and failure of one of these assets generally impacts only the location served by that asset. Guidelines regard- ing maintenance response times (to repair or replace assets within a certain period after being notified of the unacceptable condition) are set in order to minimize the impact that the assetâs condition or the maintenance work will have on safety and system performance. Asset data is