Academic Essay: From Basics to Practical Tips

Has it ever occurred to you that over the span of a solitary academic term, a typical university student can produce sufficient words to compose an entire 500-page novel? To provide context, this equates to approximately 125,000 to 150,000 words, encompassing essays, research papers, and various written tasks. This content volume is truly remarkable, emphasizing the importance of honing the skill of crafting scholarly essays. Whether you're a seasoned academic or embarking on the initial stages of your educational expedition, grasping the nuances of constructing a meticulously organized and thoroughly researched essay is paramount.

Welcome to our guide on writing an academic essay! Whether you're a seasoned student or just starting your academic journey, the prospect of written homework can be exciting and overwhelming. In this guide, we'll break down the process step by step, offering tips, strategies, and examples to help you navigate the complexities of scholarly writing. By the end, you'll have the tools and confidence to tackle any essay assignment with ease. Let's dive in!

Types of Academic Writing

The process of writing an essay usually encompasses various types of papers, each serving distinct purposes and adhering to specific conventions. Here are some common types of academic writing:

.webp)

- Essays: Essays are versatile expressions of ideas. Descriptive essays vividly portray subjects, narratives share personal stories, expository essays convey information, and persuasive essays aim to influence opinions.

- Research Papers: Research papers are analytical powerhouses. Analytical papers dissect data or topics, while argumentative papers assert a stance backed by evidence and logical reasoning.

- Reports: Reports serve as narratives in specialized fields. Technical reports document scientific or technical research, while business reports distill complex information into actionable insights for organizational decision-making.

- Reviews: Literature reviews provide comprehensive summaries and evaluations of existing research, while critical analyses delve into the intricacies of books or movies, dissecting themes and artistic elements.

- Dissertations and Theses: Dissertations represent extensive research endeavors, often at the doctoral level, exploring profound subjects. Theses, common in master's programs, showcase mastery over specific topics within defined scopes.

- Summaries and Abstracts: Summaries and abstracts condense larger works. Abstracts provide concise overviews, offering glimpses into key points and findings.

- Case Studies: Case studies immerse readers in detailed analyses of specific instances, bridging theoretical concepts with practical applications in real-world scenarios.

- Reflective Journals: Reflective journals serve as personal platforms for articulating thoughts and insights based on one's academic journey, fostering self-expression and intellectual growth.

- Academic Articles: Scholarly articles, published in academic journals, constitute the backbone of disseminating original research, contributing to the collective knowledge within specific fields.

- Literary Analyses: Literary analyses unravel the complexities of written works, decoding themes, linguistic nuances, and artistic elements, fostering a deeper appreciation for literature.

Our essay writer service can cater to all types of academic writings that you might encounter on your educational path. Use it to gain the upper hand in school or college and save precious free time.

Essay Writing Process Explained

The process of how to write an academic essay involves a series of important steps. To start, you'll want to do some pre-writing, where you brainstorm essay topics , gather information, and get a good grasp of your topic. This lays the groundwork for your essay.

Once you have a clear understanding, it's time to draft your essay. Begin with an introduction that grabs the reader's attention, gives some context, and states your main argument or thesis. The body of your essay follows, where each paragraph focuses on a specific point supported by examples or evidence. Make sure your ideas flow smoothly from one paragraph to the next, creating a coherent and engaging narrative.

After the drafting phase, take time to revise and refine your essay. Check for clarity, coherence, and consistency. Ensure your ideas are well-organized and that your writing effectively communicates your message. Finally, wrap up your essay with a strong conclusion that summarizes your main points and leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

How to Prepare for Essay Writing

Before you start writing an academic essay, there are a few things to sort out. First, make sure you totally get what the assignment is asking for. Break down the instructions and note any specific rules from your teacher. This sets the groundwork.

Then, do some good research. Check out books, articles, or trustworthy websites to gather solid info about your topic. Knowing your stuff makes your essay way stronger. Take a bit of time to brainstorm ideas and sketch out an outline. It helps you organize your thoughts and plan how your essay will flow. Think about the main points you want to get across.

Lastly, be super clear about your main argument or thesis. This is like the main point of your essay, so make it strong. Considering who's going to read your essay is also smart. Use language and tone that suits your academic audience. By ticking off these steps, you'll be in great shape to tackle your essay with confidence.

Academic Essay Example

In academic essays, examples act like guiding stars, showing the way to excellence. Let's check out some good examples to help you on your journey to doing well in your studies.

Academic Essay Format

The academic essay format typically follows a structured approach to convey ideas and arguments effectively. Here's an academic essay format example with a breakdown of the key elements:

Introduction

- Hook: Begin with an attention-grabbing opening to engage the reader.

- Background/Context: Provide the necessary background information to set the stage.

- Thesis Statement: Clearly state the main argument or purpose of the essay.

Body Paragraphs

- Topic Sentence: Start each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that relates to the thesis.

- Supporting Evidence: Include evidence, examples, or data to back up your points.

- Analysis: Analyze and interpret the evidence, explaining its significance in relation to your argument.

- Transition Sentences: Use these to guide the reader smoothly from one point to the next.

Counterargument (if applicable)

- Address Counterpoints: Acknowledge opposing views or potential objections.

- Rebuttal: Refute counterarguments and reinforce your position.

Conclusion:

- Restate Thesis: Summarize the main argument without introducing new points.

- Summary of Key Points: Recap the main supporting points made in the body.

- Closing Statement: End with a strong concluding thought or call to action.

References/Bibliography

- Cite Sources: Include proper citations for all external information used in the essay.

- Follow Citation Style: Use the required citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) specified by your instructor.

- Font and Size: Use a standard font (e.g., Times New Roman, Arial) and size (12-point).

- Margins and Spacing: Follow specified margin and spacing guidelines.

- Page Numbers: Include page numbers if required.

Adhering to this structure helps create a well-organized and coherent academic essay that effectively communicates your ideas and arguments.

Ready to Transform Essay Woes into Academic Triumphs?

Let us take you on an essay-writing adventure where brilliance knows no bounds!

How to Write an Academic Essay Step by Step

Start with an introduction.

The introduction of an essay serves as the reader's initial encounter with the topic, setting the tone for the entire piece. It aims to capture attention, generate interest, and establish a clear pathway for the reader to follow. A well-crafted introduction provides a brief overview of the subject matter, hinting at the forthcoming discussion, and compels the reader to delve further into the essay. Consult our detailed guide on how to write an essay introduction for extra details.

Captivate Your Reader

Engaging the reader within the introduction is crucial for sustaining interest throughout the essay. This involves incorporating an engaging hook, such as a thought-provoking question, a compelling anecdote, or a relevant quote. By presenting an intriguing opening, the writer can entice the reader to continue exploring the essay, fostering a sense of curiosity and investment in the upcoming content. To learn more about how to write a hook for an essay , please consult our guide,

Provide Context for a Chosen Topic

In essay writing, providing context for the chosen topic is essential to ensure that readers, regardless of their prior knowledge, can comprehend the subject matter. This involves offering background information, defining key terms, and establishing the broader context within which the essay unfolds. Contextualization sets the stage, enabling readers to grasp the significance of the topic and its relevance within a particular framework. If you buy a dissertation or essay, or any other type of academic writing, our writers will produce an introduction that follows all the mentioned quality criteria.

Make a Thesis Statement

The thesis statement is the central anchor of the essay, encapsulating its main argument or purpose. It typically appears towards the end of the introduction, providing a concise and clear declaration of the writer's stance on the chosen topic. A strong thesis guides the reader on what to expect, serving as a roadmap for the essay's subsequent development.

Outline the Structure of Your Essay

Clearly outlining the structure of the essay in the introduction provides readers with a roadmap for navigating the content. This involves briefly highlighting the main points or arguments that will be explored in the body paragraphs. By offering a structural overview, the writer enhances the essay's coherence, making it easier for the reader to follow the logical progression of ideas and supporting evidence throughout the text.

Continue with the Main Body

The main body is the most important aspect of how to write an academic essay where the in-depth exploration and development of the chosen topic occur. Each paragraph within this section should focus on a specific aspect of the argument or present supporting evidence. It is essential to maintain a logical flow between paragraphs, using clear transitions to guide the reader seamlessly from one point to the next. The main body is an opportunity to delve into the nuances of the topic, providing thorough analysis and interpretation to substantiate the thesis statement.

Choose the Right Length

Determining the appropriate length for an essay is a critical aspect of effective communication. The length should align with the depth and complexity of the chosen topic, ensuring that the essay adequately explores key points without unnecessary repetition or omission of essential information. Striking a balance is key – a well-developed essay neither overextends nor underrepresents the subject matter. Adhering to any specified word count or page limit set by the assignment guidelines is crucial to meet academic requirements while maintaining clarity and coherence.

Write Compelling Paragraphs

In academic essay writing, thought-provoking paragraphs form the backbone of the main body, each contributing to the overall argument or analysis. Each paragraph should begin with a clear topic sentence that encapsulates the main point, followed by supporting evidence or examples. Thoroughly analyzing the evidence and providing insightful commentary demonstrates the depth of understanding and contributes to the overall persuasiveness of the essay. Cohesion between paragraphs is crucial, achieved through effective transitions that ensure a smooth and logical progression of ideas, enhancing the overall readability and impact of the essay.

Finish by Writing a Conclusion

The conclusion serves as the essay's final impression, providing closure and reinforcing the key insights. It involves restating the thesis without introducing new information, summarizing the main points addressed in the body, and offering a compelling closing thought. The goal is to leave a lasting impact on the reader, emphasizing the significance of the discussed topic and the validity of the thesis statement. A well-crafted conclusion brings the essay full circle, leaving the reader with a sense of resolution and understanding. Have you already seen our collection of new persuasive essay topics ? If not, we suggest you do it right after finishing this article to boost your creativity!

Proofread and Edit the Document

After completing the essay, a critical step is meticulous proofreading and editing. This process involves reviewing the document for grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and punctuation issues. Additionally, assess the overall coherence and flow of ideas, ensuring that each paragraph contributes effectively to the essay's purpose. Consider the clarity of expression, the appropriateness of language, and the overall organization of the content. Taking the time to proofread and edit enhances the overall quality of the essay, presenting a polished and professional piece of writing. It is advisable to seek feedback from peers or instructors to gain additional perspectives on the essay's strengths and areas for improvement. For more insightful tips, feel free to check out our guide on how to write a descriptive essay .

Alright, let's wrap it up. Knowing how to write academic essays is a big deal. It's not just about passing assignments – it's a skill that sets you up for effective communication and deep thinking. These essays teach us to explain our ideas clearly, build strong arguments, and be part of important conversations, both in school and out in the real world. Whether you're studying or working, being able to put your thoughts into words is super valuable. So, take the time to master this skill – it's a game-changer!

Ready to Turn Your Academic Aspirations into A+ Realities?

Our expert pens are poised, and your academic adventure awaits!

What Is An Academic Essay?

How to write an academic essay, how to write a good academic essay, related articles.

.webp)

- Corrections

Search Help

Get the most out of Google Scholar with some helpful tips on searches, email alerts, citation export, and more.

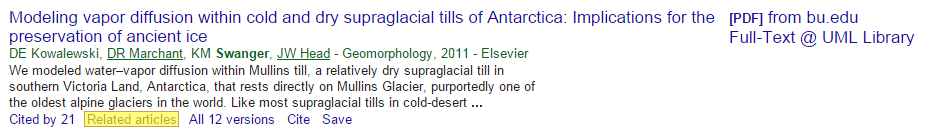

Finding recent papers

Your search results are normally sorted by relevance, not by date. To find newer articles, try the following options in the left sidebar:

- click "Since Year" to show only recently published papers, sorted by relevance;

- click "Sort by date" to show just the new additions, sorted by date;

- click the envelope icon to have new results periodically delivered by email.

Locating the full text of an article

Abstracts are freely available for most of the articles. Alas, reading the entire article may require a subscription. Here're a few things to try:

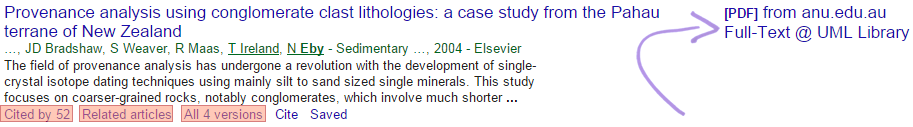

- click a library link, e.g., "FindIt@Harvard", to the right of the search result;

- click a link labeled [PDF] to the right of the search result;

- click "All versions" under the search result and check out the alternative sources;

- click "Related articles" or "Cited by" under the search result to explore similar articles.

If you're affiliated with a university, but don't see links such as "FindIt@Harvard", please check with your local library about the best way to access their online subscriptions. You may need to do search from a computer on campus, or to configure your browser to use a library proxy.

Getting better answers

If you're new to the subject, it may be helpful to pick up the terminology from secondary sources. E.g., a Wikipedia article for "overweight" might suggest a Scholar search for "pediatric hyperalimentation".

If the search results are too specific for your needs, check out what they're citing in their "References" sections. Referenced works are often more general in nature.

Similarly, if the search results are too basic for you, click "Cited by" to see newer papers that referenced them. These newer papers will often be more specific.

Explore! There's rarely a single answer to a research question. Click "Related articles" or "Cited by" to see closely related work, or search for author's name and see what else they have written.

Searching Google Scholar

Use the "author:" operator, e.g., author:"d knuth" or author:"donald e knuth".

Put the paper's title in quotations: "A History of the China Sea".

You'll often get better results if you search only recent articles, but still sort them by relevance, not by date. E.g., click "Since 2018" in the left sidebar of the search results page.

To see the absolutely newest articles first, click "Sort by date" in the sidebar. If you use this feature a lot, you may also find it useful to setup email alerts to have new results automatically sent to you.

Note: On smaller screens that don't show the sidebar, these options are available in the dropdown menu labelled "Year" right below the search button.

Select the "Case law" option on the homepage or in the side drawer on the search results page.

It finds documents similar to the given search result.

It's in the side drawer. The advanced search window lets you search in the author, title, and publication fields, as well as limit your search results by date.

Select the "Case law" option and do a keyword search over all jurisdictions. Then, click the "Select courts" link in the left sidebar on the search results page.

Tip: To quickly search a frequently used selection of courts, bookmark a search results page with the desired selection.

Access to articles

For each Scholar search result, we try to find a version of the article that you can read. These access links are labelled [PDF] or [HTML] and appear to the right of the search result. For example:

A paper that you need to read

Access links cover a wide variety of ways in which articles may be available to you - articles that your library subscribes to, open access articles, free-to-read articles from publishers, preprints, articles in repositories, etc.

When you are on a campus network, access links automatically include your library subscriptions and direct you to subscribed versions of articles. On-campus access links cover subscriptions from primary publishers as well as aggregators.

Off-campus access

Off-campus access links let you take your library subscriptions with you when you are at home or traveling. You can read subscribed articles when you are off-campus just as easily as when you are on-campus. Off-campus access links work by recording your subscriptions when you visit Scholar while on-campus, and looking up the recorded subscriptions later when you are off-campus.

We use the recorded subscriptions to provide you with the same subscribed access links as you see on campus. We also indicate your subscription access to participating publishers so that they can allow you to read the full-text of these articles without logging in or using a proxy. The recorded subscription information expires after 30 days and is automatically deleted.

In addition to Google Scholar search results, off-campus access links can also appear on articles from publishers participating in the off-campus subscription access program. Look for links labeled [PDF] or [HTML] on the right hand side of article pages.

Anne Author , John Doe , Jane Smith , Someone Else

In this fascinating paper, we investigate various topics that would be of interest to you. We also describe new methods relevant to your project, and attempt to address several questions which you would also like to know the answer to. Lastly, we analyze …

You can disable off-campus access links on the Scholar settings page . Disabling off-campus access links will turn off recording of your library subscriptions. It will also turn off indicating subscription access to participating publishers. Once off-campus access links are disabled, you may need to identify and configure an alternate mechanism (e.g., an institutional proxy or VPN) to access your library subscriptions while off-campus.

Email Alerts

Do a search for the topic of interest, e.g., "M Theory"; click the envelope icon in the sidebar of the search results page; enter your email address, and click "Create alert". We'll then periodically email you newly published papers that match your search criteria.

No, you can enter any email address of your choice. If the email address isn't a Google account or doesn't match your Google account, then we'll email you a verification link, which you'll need to click to start receiving alerts.

This works best if you create a public profile , which is free and quick to do. Once you get to the homepage with your photo, click "Follow" next to your name, select "New citations to my articles", and click "Done". We will then email you when we find new articles that cite yours.

Search for the title of your paper, e.g., "Anti de Sitter space and holography"; click on the "Cited by" link at the bottom of the search result; and then click on the envelope icon in the left sidebar of the search results page.

First, do a search for your colleague's name, and see if they have a Scholar profile. If they do, click on it, click the "Follow" button next to their name, select "New articles by this author", and click "Done".

If they don't have a profile, do a search by author, e.g., [author:s-hawking], and click on the mighty envelope in the left sidebar of the search results page. If you find that several different people share the same name, you may need to add co-author names or topical keywords to limit results to the author you wish to follow.

We send the alerts right after we add new papers to Google Scholar. This usually happens several times a week, except that our search robots meticulously observe holidays.

There's a link to cancel the alert at the bottom of every notification email.

If you created alerts using a Google account, you can manage them all here . If you're not using a Google account, you'll need to unsubscribe from the individual alerts and subscribe to the new ones.

Google Scholar library

Google Scholar library is your personal collection of articles. You can save articles right off the search page, organize them by adding labels, and use the power of Scholar search to quickly find just the one you want - at any time and from anywhere. You decide what goes into your library, and we’ll keep the links up to date.

You get all the goodies that come with Scholar search results - links to PDF and to your university's subscriptions, formatted citations, citing articles, and more!

Library help

Find the article you want to add in Google Scholar and click the “Save” button under the search result.

Click “My library” at the top of the page or in the side drawer to view all articles in your library. To search the full text of these articles, enter your query as usual in the search box.

Find the article you want to remove, and then click the “Delete” button under it.

- To add a label to an article, find the article in your library, click the “Label” button under it, select the label you want to apply, and click “Done”.

- To view all the articles with a specific label, click the label name in the left sidebar of your library page.

- To remove a label from an article, click the “Label” button under it, deselect the label you want to remove, and click “Done”.

- To add, edit, or delete labels, click “Manage labels” in the left column of your library page.

Only you can see the articles in your library. If you create a Scholar profile and make it public, then the articles in your public profile (and only those articles) will be visible to everyone.

Your profile contains all the articles you have written yourself. It’s a way to present your work to others, as well as to keep track of citations to it. Your library is a way to organize the articles that you’d like to read or cite, not necessarily the ones you’ve written.

Citation Export

Click the "Cite" button under the search result and then select your bibliography manager at the bottom of the popup. We currently support BibTeX, EndNote, RefMan, and RefWorks.

Err, no, please respect our robots.txt when you access Google Scholar using automated software. As the wearers of crawler's shoes and webmaster's hat, we cannot recommend adherence to web standards highly enough.

Sorry, we're unable to provide bulk access. You'll need to make an arrangement directly with the source of the data you're interested in. Keep in mind that a lot of the records in Google Scholar come from commercial subscription services.

Sorry, we can only show up to 1,000 results for any particular search query. Try a different query to get more results.

Content Coverage

Google Scholar includes journal and conference papers, theses and dissertations, academic books, pre-prints, abstracts, technical reports and other scholarly literature from all broad areas of research. You'll find works from a wide variety of academic publishers, professional societies and university repositories, as well as scholarly articles available anywhere across the web. Google Scholar also includes court opinions and patents.

We index research articles and abstracts from most major academic publishers and repositories worldwide, including both free and subscription sources. To check current coverage of a specific source in Google Scholar, search for a sample of their article titles in quotes.

While we try to be comprehensive, it isn't possible to guarantee uninterrupted coverage of any particular source. We index articles from sources all over the web and link to these websites in our search results. If one of these websites becomes unavailable to our search robots or to a large number of web users, we have to remove it from Google Scholar until it becomes available again.

Our meticulous search robots generally try to index every paper from every website they visit, including most major sources and also many lesser known ones.

That said, Google Scholar is primarily a search of academic papers. Shorter articles, such as book reviews, news sections, editorials, announcements and letters, may or may not be included. Untitled documents and documents without authors are usually not included. Website URLs that aren't available to our search robots or to the majority of web users are, obviously, not included either. Nor do we include websites that require you to sign up for an account, install a browser plugin, watch four colorful ads, and turn around three times and say coo-coo before you can read the listing of titles scanned at 10 DPI... You get the idea, we cover academic papers from sensible websites.

That's usually because we index many of these papers from other websites, such as the websites of their primary publishers. The "site:" operator currently only searches the primary version of each paper.

It could also be that the papers are located on examplejournals.gov, not on example.gov. Please make sure you're searching for the "right" website.

That said, the best way to check coverage of a specific source is to search for a sample of their papers using the title of the paper.

Ahem, we index papers, not journals. You should also ask about our coverage of universities, research groups, proteins, seminal breakthroughs, and other dimensions that are of interest to users. All such questions are best answered by searching for a statistical sample of papers that has the property of interest - journal, author, protein, etc. Many coverage comparisons are available if you search for [allintitle:"google scholar"], but some of them are more statistically valid than others.

Currently, Google Scholar allows you to search and read published opinions of US state appellate and supreme court cases since 1950, US federal district, appellate, tax and bankruptcy courts since 1923 and US Supreme Court cases since 1791. In addition, it includes citations for cases cited by indexed opinions or journal articles which allows you to find influential cases (usually older or international) which are not yet online or publicly available.

Legal opinions in Google Scholar are provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied on as a substitute for legal advice from a licensed lawyer. Google does not warrant that the information is complete or accurate.

We normally add new papers several times a week. However, updates to existing records take 6-9 months to a year or longer, because in order to update our records, we need to first recrawl them from the source website. For many larger websites, the speed at which we can update their records is limited by the crawl rate that they allow.

Inclusion and Corrections

We apologize, and we assure you the error was unintentional. Automated extraction of information from articles in diverse fields can be tricky, so an error sometimes sneaks through.

Please write to the owner of the website where the erroneous search result is coming from, and encourage them to provide correct bibliographic data to us, as described in the technical guidelines . Once the data is corrected on their website, it usually takes 6-9 months to a year or longer for it to be updated in Google Scholar. We appreciate your help and your patience.

If you can't find your papers when you search for them by title and by author, please refer your publisher to our technical guidelines .

You can also deposit your papers into your institutional repository or put their PDF versions on your personal website, but please follow your publisher's requirements when you do so. See our technical guidelines for more details on the inclusion process.

We normally add new papers several times a week; however, it might take us some time to crawl larger websites, and corrections to already included papers can take 6-9 months to a year or longer.

Google Scholar generally reflects the state of the web as it is currently visible to our search robots and to the majority of users. When you're searching for relevant papers to read, you wouldn't want it any other way!

If your citation counts have gone down, chances are that either your paper or papers that cite it have either disappeared from the web entirely, or have become unavailable to our search robots, or, perhaps, have been reformatted in a way that made it difficult for our automated software to identify their bibliographic data and references. If you wish to correct this, you'll need to identify the specific documents with indexing problems and ask your publisher to fix them. Please refer to the technical guidelines .

Please do let us know . Please include the URL for the opinion, the corrected information and a source where we can verify the correction.

We're only able to make corrections to court opinions that are hosted on our own website. For corrections to academic papers, books, dissertations and other third-party material, click on the search result in question and contact the owner of the website where the document came from. For corrections to books from Google Book Search, click on the book's title and locate the link to provide feedback at the bottom of the book's page.

General Questions

These are articles which other scholarly articles have referred to, but which we haven't found online. To exclude them from your search results, uncheck the "include citations" box on the left sidebar.

First, click on links labeled [PDF] or [HTML] to the right of the search result's title. Also, check out the "All versions" link at the bottom of the search result.

Second, if you're affiliated with a university, using a computer on campus will often let you access your library's online subscriptions. Look for links labeled with your library's name to the right of the search result's title. Also, see if there's a link to the full text on the publisher's page with the abstract.

Keep in mind that final published versions are often only available to subscribers, and that some articles are not available online at all. Good luck!

Technically, your web browser remembers your settings in a "cookie" on your computer's disk, and sends this cookie to our website along with every search. Check that your browser isn't configured to discard our cookies. Also, check if disabling various proxies or overly helpful privacy settings does the trick. Either way, your settings are stored on your computer, not on our servers, so a long hard look at your browser's preferences or internet options should help cure the machine's forgetfulness.

Not even close. That phrase is our acknowledgement that much of scholarly research involves building on what others have already discovered. It's taken from Sir Isaac Newton's famous quote, "If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."

- Privacy & Terms

The writer of the academic essay aims to persuade readers of an idea based on evidence. The beginning of the essay is a crucial first step in this process. In order to engage readers and establish your authority, the beginning of your essay has to accomplish certain business. Your beginning should introduce the essay, focus it, and orient readers.

Introduce the Essay. The beginning lets your readers know what the essay is about, the topic . The essay's topic does not exist in a vacuum, however; part of letting readers know what your essay is about means establishing the essay's context , the frame within which you will approach your topic. For instance, in an essay about the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of speech, the context may be a particular legal theory about the speech right; it may be historical information concerning the writing of the amendment; it may be a contemporary dispute over flag burning; or it may be a question raised by the text itself. The point here is that, in establishing the essay's context, you are also limiting your topic. That is, you are framing an approach to your topic that necessarily eliminates other approaches. Thus, when you determine your context, you simultaneously narrow your topic and take a big step toward focusing your essay. Here's an example.

The paragraph goes on. But as you can see, Chopin's novel (the topic) is introduced in the context of the critical and moral controversy its publication engendered.

Focus the Essay. Beyond introducing your topic, your beginning must also let readers know what the central issue is. What question or problem will you be thinking about? You can pose a question that will lead to your idea (in which case, your idea will be the answer to your question), or you can make a thesis statement. Or you can do both: you can ask a question and immediately suggest the answer that your essay will argue. Here's an example from an essay about Memorial Hall.

The fullness of your idea will not emerge until your conclusion, but your beginning must clearly indicate the direction your idea will take, must set your essay on that road. And whether you focus your essay by posing a question, stating a thesis, or combining these approaches, by the end of your beginning, readers should know what you're writing about, and why —and why they might want to read on.

Orient Readers. Orienting readers, locating them in your discussion, means providing information and explanations wherever necessary for your readers' understanding. Orienting is important throughout your essay, but it is crucial in the beginning. Readers who don't have the information they need to follow your discussion will get lost and quit reading. (Your teachers, of course, will trudge on.) Supplying the necessary information to orient your readers may be as simple as answering the journalist's questions of who, what, where, when, how, and why. It may mean providing a brief overview of events or a summary of the text you'll be analyzing. If the source text is brief, such as the First Amendment, you might just quote it. If the text is well known, your summary, for most audiences, won't need to be more than an identifying phrase or two:

Often, however, you will want to summarize your source more fully so that readers can follow your analysis of it.

Questions of Length and Order. How long should the beginning be? The length should be proportionate to the length and complexity of the whole essay. For instance, if you're writing a five-page essay analyzing a single text, your beginning should be brief, no more than one or two paragraphs. On the other hand, it may take a couple of pages to set up a ten-page essay.

Does the business of the beginning have to be addressed in a particular order? No, but the order should be logical. Usually, for instance, the question or statement that focuses the essay comes at the end of the beginning, where it serves as the jumping-off point for the middle, or main body, of the essay. Topic and context are often intertwined, but the context may be established before the particular topic is introduced. In other words, the order in which you accomplish the business of the beginning is flexible and should be determined by your purpose.

Opening Strategies. There is still the further question of how to start. What makes a good opening? You can start with specific facts and information, a keynote quotation, a question, an anecdote, or an image. But whatever sort of opening you choose, it should be directly related to your focus. A snappy quotation that doesn't help establish the context for your essay or that later plays no part in your thinking will only mislead readers and blur your focus. Be as direct and specific as you can be. This means you should avoid two types of openings:

- The history-of-the-world (or long-distance) opening, which aims to establish a context for the essay by getting a long running start: "Ever since the dawn of civilized life, societies have struggled to reconcile the need for change with the need for order." What are we talking about here, political revolution or a new brand of soft drink? Get to it.

- The funnel opening (a variation on the same theme), which starts with something broad and general and "funnels" its way down to a specific topic. If your essay is an argument about state-mandated prayer in public schools, don't start by generalizing about religion; start with the specific topic at hand.

Remember. After working your way through the whole draft, testing your thinking against the evidence, perhaps changing direction or modifying the idea you started with, go back to your beginning and make sure it still provides a clear focus for the essay. Then clarify and sharpen your focus as needed. Clear, direct beginnings rarely present themselves ready-made; they must be written, and rewritten, into the sort of sharp-eyed clarity that engages readers and establishes your authority.

Copyright 1999, Patricia Kain, for the Writing Center at Harvard University

Stand on the shoulders of giants

Google Scholar provides a simple way to broadly search for scholarly literature. From one place, you can search across many disciplines and sources: articles, theses, books, abstracts and court opinions, from academic publishers, professional societies, online repositories, universities and other web sites. Google Scholar helps you find relevant work across the world of scholarly research.

How are documents ranked?

Google Scholar aims to rank documents the way researchers do, weighing the full text of each document, where it was published, who it was written by, as well as how often and how recently it has been cited in other scholarly literature.

Features of Google Scholar

- Search all scholarly literature from one convenient place

- Explore related works, citations, authors, and publications

- Locate the complete document through your library or on the web

- Keep up with recent developments in any area of research

- Check who's citing your publications, create a public author profile

Disclaimer: Legal opinions in Google Scholar are provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied on as a substitute for legal advice from a licensed lawyer. Google does not warrant that the information is complete or accurate.

- Privacy & Terms

How to Write an Academic Essay in 6 Simple Steps

#scribendiinc

Written by Scribendi

Are you wondering how to write an academic essay successfully? There are so many steps to writing an academic essay that it can be difficult to know where to start.

Here, we outline how to write an academic essay in 6 simple steps, from how to research for an academic essay to how to revise an essay and everything in between.

Our essay writing tips are designed to help you learn how to write an academic essay that is ready for publication (after academic editing and academic proofreading , of course!).

Your paper isn't complete until you've done all the needed proofreading. Make sure you leave time for it after the writing process!

Download Our Pocket Checklist for Academic Papers. Just input your email below!

Types of academic writing.

With academic essay writing, there are certain conventions that writers are expected to follow. As such, it's important to know the basics of academic writing before you begin writing your essay.

Read More: What Is Academic Writing?

Before you begin writing your essay, you need to know what type of essay you are writing. This will help you follow the correct structure, which will make academic paper editing a faster and simpler process.

Will you be writing a descriptive essay, an analytical essay, a persuasive essay, or a critical essay?

Read More: How to Master the 4 Types of Academic Writing

You can learn how to write academic essays by first mastering the four types of academic writing and then applying the correct rules to the appropriate type of essay writing.

Regardless of the type of essay you will be writing, all essays will include:

An introduction

At least three body paragraphs

A conclusion

A bibliography/reference list

To strengthen your essay writing skills, it can also help to learn how to research for an academic essay.

Step 1: Preparing to Write Your Essay

The essay writing process involves a few main stages:

Researching

As such, in learning how to write an academic essay, it is also important to learn how to research for an academic essay and how to revise an essay.

Read More: Online Research Tips for Students and Scholars

To beef up your research skills, remember these essay writing tips from the above article:

Learn how to identify reliable sources.

Understand the nuances of open access.

Discover free academic journals and research databases.

Manage your references.

Provide evidence for every claim so you can avoid plagiarism .

Read More: 17 Research Databases for Free Articles

You will want to do the research for your academic essay points, of course, but you will also want to research various journals for the publication of your paper.

Different journals have different guidelines and thus different requirements for writers. These can be related to style, formatting, and more.

Knowing these before you begin writing can save you a lot of time if you also want to learn how to revise an essay. If you ensure your paper meets the guidelines of the journal you want to publish in, you will not have to revise it again later for this purpose.

After the research stage, you can draft your thesis and introduction as well as outline the rest of your essay. This will put you in a good position to draft your body paragraphs and conclusion, craft your bibliography, and edit and proofread your paper.

Step 2: Writing the Essay Introduction and Thesis Statement

When learning how to write academic essays , learning how to write an introduction is key alongside learning how to research for an academic essay.

Your introduction should broadly introduce your topic. It will give an overview of your essay and the points that will be discussed. It is typically about 10% of the final word count of the text.

All introductions follow a general structure:

Topic statement

Thesis statement

Read More: How to Write an Introduction

Your topic statement should hook your reader, making them curious about your topic. They should want to learn more after reading this statement. To best hook your reader in academic essay writing, consider providing a fact, a bold statement, or an intriguing question.

The discussion about your topic in the middle of your introduction should include some background information about your topic in the academic sphere. Your scope should be limited enough that you can address the topic within the length of your paper but broad enough that the content is understood by the reader.

Your thesis statement should be incredibly specific and only one to two sentences long. Here is another essay writing tip: if you are able to locate an effective thesis early on, it will save you time during the academic editing process.

Read More: How to Write a Great Thesis Statement

Step 3: Writing the Essay Body

When learning how to write academic essays, you must learn how to write a good body paragraph. That's because your essay will be primarily made up of them!

The body paragraphs of your essay will develop the argument you outlined in your thesis. They will do this by providing your ideas on a topic backed up by evidence of specific points.

These paragraphs will typically take up about 80% of your essay. As a result, a good essay writing tip is to learn how to properly structure a paragraph.

Each paragraph consists of the following:

A topic sentence

Supporting sentences

A transition

Read More: How to Write a Paragraph

In learning how to revise an essay, you should keep in mind the organization of your paragraphs.

Your first paragraph should contain your strongest argument.

The secondary paragraphs should contain supporting arguments.

The last paragraph should contain your second-strongest argument.

Step 4: Writing the Essay Conclusion

Your essay conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay and primarily reminds your reader of your thesis. It also wraps up your essay and discusses your findings more generally.

The conclusion typically makes up about 10% of the text, like the introduction. It shows the reader that you have accomplished what you intended to at the outset of your essay.

Here are a couple more good essay writing tips for your conclusion:

Don't introduce any new ideas into your conclusion.

Don't undermine your argument with opposing ideas.

Read More: How to Write a Conclusion Paragraph in 3 Easy Steps

Now that you know how to write an academic essay, it's time to learn how to write a bibliography along with some academic editing and proofreading advice.

Step 5: Writing the Bibliography or Works Cited

The bibliography of your paper lists all the references you cited. It is typically alphabetized or numbered (depending on the style guide).

Read More: How to Write an Academic Essay with References

When learning how to write academic essays, you may notice that there are various style guides you may be required to use by a professor or journal, including unique or custom styles.

Some of the most common style guides include:

Chicago style

For help organizing your references for academic essay writing, consider a software manager. They can help you collect and format your references correctly and consistently, both quickly and with minimal effort.

Read More: 6 Reference Manager Software Solutions for Your Research

As you learn how to research for an academic essay most effectively, you may notice that a reference manager can also help make academic paper editing easier.

Step 6: Revising Your Essay

Once you've finally drafted your entire essay . . . you're still not done!

That's because editing and proofreading are the essential final steps of any writing process .

An academic editor can help you identify core issues with your writing , including its structure, its flow, its clarity, and its overall readability. They can give you substantive feedback and essay writing tips to improve your document. Therefore, it's a good idea to have an editor review your first draft so you can improve it prior to proofreading.

A specialized academic editor can assess the content of your writing. As a subject-matter expert in your subject, they can offer field-specific insight and critical commentary. Specialized academic editors can also provide services that others may not, including:

Academic document formatting

Academic figure formatting

Academic reference formatting

An academic proofreader can help you perfect the final draft of your paper to ensure it is completely error free in terms of spelling and grammar. They can also identify any inconsistencies in your work but will not look for any issues in the content of your writing, only its mechanics. This is why you should have a proofreader revise your final draft so that it is ready to be seen by an audience.

Read More: How to Find the Right Academic Paper Editor or Proofreader

When learning how to research and write an academic essay, it is important to remember that editing is a required step. Don ' t forget to allot time for editing after you ' ve written your paper.

Set yourself up for success with this guide on how to write an academic essay. With a solid draft, you'll have better chances of getting published and read in any journal of your choosing.

Our academic essay writing tips are sure to help you learn how to research an academic essay, how to write an academic essay, and how to revise an academic essay.

If your academic paper looks sloppy, your readers may assume your research is sloppy. Download our Pocket Proofreading Checklist for Academic Papers before you take that one last crucial look at your paper.

About the Author

Scribendi's in-house editors work with writers from all over the globe to perfect their writing. They know that no piece of writing is complete without a professional edit, and they love to see a good piece of writing transformed into a great one. Scribendi's in-house editors are unrivaled in both experience and education, having collectively edited millions of words and obtained numerous degrees. They love consuming caffeinated beverages, reading books of various genres, and relaxing in quiet, dimly lit spaces.

Have You Read?

"The Complete Beginner's Guide to Academic Writing"

Related Posts

21 Legit Research Databases for Free Journal Articles in 2024

How to Find the Right Academic Paper Editor or Proofreader

How to Master the 4 Types of Academic Writing

Upload your file(s) so we can calculate your word count, or enter your word count manually.

We will also recommend a service based on the file(s) you upload.

English is not my first language. I need English editing and proofreading so that I sound like a native speaker.

I need to have my journal article, dissertation, or term paper edited and proofread, or I need help with an admissions essay or proposal.

I have a novel, manuscript, play, or ebook. I need editing, copy editing, proofreading, a critique of my work, or a query package.

I need editing and proofreading for my white papers, reports, manuals, press releases, marketing materials, and other business documents.

I need to have my essay, project, assignment, or term paper edited and proofread.

I want to sound professional and to get hired. I have a resume, letter, email, or personal document that I need to have edited and proofread.

Prices include your personal % discount.

Prices include % sales tax ( ).

Faculty and researchers : We want to hear from you! We are launching a survey to learn more about your library collection needs for teaching, learning, and research. If you would like to participate, please complete the survey by May 17, 2024. Thank you for your participation!

- University of Massachusetts Lowell

- University Libraries

Google Scholar Search Strategies

- About Google Scholar

- Manage Settings

- Enable My Library

- Google Scholar Library

- Cite from Google Scholar

- Tracking Citations

- Add Articles Manually

- Refine your Profile Settings

Using Google Scholar for Research

Google Scholar is a powerful tool for researchers and students alike to access peer-reviewed papers. With Scholar, you are able to not only search for an article, author or journal of interest, you can also save and organize these articles, create email alerts, export citations and more. Below you will find some basic search tips that will prove useful.

This page also includes information on Google Scholar Library - a resource that allows you to save, organize and manage citations - as well as information on citing a paper on Google Scholar.

Search Tips

- Locate Full Text

- Sort by Date

- Related Articles

- Court Opinions

- Email Alerts

- Advanced Search

Abstracts are freely available for most of the articles and UMass Lowell holds many subscriptions to journals and online resources. The first step is make sure you are affiliated with the UML Library on and off campus by Managing your Settings, under Library Links.

When searching in Google Scholar here are a few things to try to get full text:

- click a library link, e.g., "Full-text @ UML Library", to the right of the search result;

- click a link labeled [PDF] to the right of the search result;

- click "All versions" under the search result and check out the alternative sources;

- click "More" under the search result to see if there's an option for full-text;

- click "Related articles" or "Cited by" under the search result to explore similar articles.

Your search results are normally sorted by relevance, not by date. To find newer articles, try the following options in the left sidebar:

- click "Sort by date" to show just the new additions, sorted by date; If you use this feature a lot, you may also find it useful to setup email alerts to have new results automatically sent to you.

- click the envelope icon to have new results periodically delivered by email.

Note: On smaller screens that don't show the sidebar, these options are available in the dropdown menu labeled "Any time" right below the search button .

The Related Articles option under the search result can be a useful tool when performing research on a specific topic.

After clicking you will see articles from the same authors and with the same keywords.

You can select the jurisdiction from either the search results page or the home page as well; simply click "select courts". You can also refine your search by state courts or federal courts.

To quickly search a frequently used selection of courts, bookmark a search results page with the desired selection.

How do I sign up for email alerts?

Do a search for the topic of interest, e.g., "M Theory"; click the envelope icon in the sidebar of the search results page; enter your email address, and click " Create alert ". Google will periodically email you newly published papers that match your search criteria. You can use any email address for this; it does not need to be a Google Account.

If you want to get alerts from new articles published in a specific journal; type in the name of this journal in the search bar and create an alert like you would a keyword.

How do I get notified of new papers published by my colleagues, advisors or professors?

First, do a search for your their name, and see if they have a Citations profile. If they do, click on it, and click the "Follow new articles" link in the right sidebar under the search box.

If they don't have a profile, do a search by author, e.g., [author:s-hawking], and click on the mighty envelope in the left sidebar of the search results page. If you find that several different people share the same name, you may need to add co-author names or topical keywords to limit results to the author you wish to follow.

How do I change my alerts?

If you created alerts using a Google account, you can manage them all on the "Alerts" page .

From here you can create, edit or delete alerts. Select cancel under the actions column to unsubscribe from an alert.

This will pop-open the advanced search menu

Here you can search specific words/phrases as well as for author, title and journal. You can also limit your search results by date.

- << Previous: Enable My Library

- Next: Google Scholar Library >>

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 2:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uml.edu/googlescholar

Module 6: Research

Google scholar.

An increasingly popular article database is Google Scholar . It looks like a regular Google search, and it aims to include the vast majority of scholarly resources available. While it has some limitations (like not including a list of which journals they include), it’s a very useful tool if you want to cast a wide net.

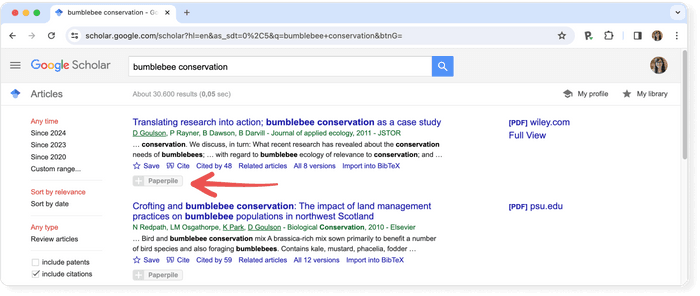

Here are three tips for using Google Scholar effectively:

- Add your topic field (economics, psychology, French, etc.) as one of your keywords . If you just put in “crime,” for example, Google Scholar will return all sorts of stuff from sociology, psychology, geography, and history. If your paper is on crime in French literature, your best sources may be buried under thousands of papers from other disciplines. A set of search terms like “crime French literature modern” will get you to relevant sources much faster.

- Don’t ever pay for an article . When you click on links to articles in Google Scholar, you may end up on a publisher’s site that tells you that you can download the article for $20 or $30. Don’t do it! You probably have access to virtually all the published academic literature through your library resources. Write down the key information (authors’ names, title, journal title, volume, issue number, year, page numbers) and go find the article through your library website. If you don’t have immediate full-text access, you may be able to get it through inter-library loan.

- Use the “cited by” feature . If you get one great hit on Google Scholar, you can quickly see a list of other papers that cited it. For example, the search terms “crime economics” yielded this hit for a 1988 paper that appeared in a journal called Kyklos :

Google Scholar search results.

Using Google Scholar

Watch this video to get a better idea of how to utilize Google Scholar for finding articles. While this video shows specifics for setting up an account with Eastern Michigan University, the same principles apply to other colleges and universities. Ask your librarian if you have more questions.

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Secondary Sources in Their Natural Habitats. Authored by : Amy Guptill. Provided by : The College at Brockport, SUNY. Located at : http://pressbooks.opensuny.org/writing-in-college-from-competence-to-excellence/chapter/4/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Using Google Scholar. Authored by : EMU Library. Located at : https://youtu.be/oqnjhjISHFk . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

11 Best Tips on How to use Google Scholar

Google Scholar was my Number 1 Tool and absolute best friend as a university student. It should be yours, too.

Google Scholar is a goldmine of a resource for boosting your grades.

It makes studying easier, means you can find tons more articles than you thought you could, and often saves you a few trips into your library to find sources.

In this article I’ll show you exactly how to use Google Scholar like a Pro.

I can’t stress enough how important it is to master Google Scholar.

Whenever I found myself in a situation where I had an essay due on short notice , Google Scholar saved my life. I’ve been in situations in Northern England where my university was closed due to snowfall and the only way I could get the articles I needed to finish my essays was to use Google Scholar.

It works. And it’s saved my life a million times. I’ve written over 25 academic articles , and even as a professional, Google Scholar is my go-to source.

If you want to save time while writing your essay , Google Scholar is the source for you. In fact, even if you don’t want to save time, you really should be using Google Scholar for every single essay you write at university.

Let’s take a look under the hood and find out what Google Scholar’s all about, and how to use Google Scholar like a Pro!

1. Ditch Regular Google. Google Scholar Kicks its Butt.

Look, you’ve probably been told this a million times, but from the perspective of a professor, let me tell you: it needs to be said again. Don’t use regular Google to find information for your essay.

Okay, let me reword that: Don’t cite sources from regular Google. I know that you will probably Wikipedia key ideas, read easy-to-digest blog posts about your topics, and generally get to understand ideas through google searches. Okay, that’s fine. But that’s not what you’re going to cite in your essays. In fact, that’s what we might call Pre-Research. It’s what we do before we get serious about writing our essay .

When it’s time to get serious, you’ve got to only read and cite the quality articles written by experts. Take a look at this infographic for some ideas of what you should and shouldn’t cite:

Google Scholar is your go-to source when you want to find quality articles to cite in your essays. It filters out the nonsense for you and works hard to provide only the high-quality sources on the infographic above. It cuts out the junk to save you time.

So next time you’re wanting to cite a blog post or website, stop yourself. Go to Google Scholar, spend three minutes looking up some keywords, and cite a real scholarly source instead.

Here’s how to use Google Scholar in a nutshell:

1. Go to the Google Scholar website. Pay special attention: Google Scholar is not normal Google.

2. Type in the keywords for the topic you’re researching:

3. Read the descriptions under each search result

4. Select a source that seems relevant .

5. Read the source

6. Cite the source.

Done! It’s that simple. But wait … if you want to be a pro Google Scholar user, read on and I’ll zoom in on some strategies to take your Google Scholar searching to the next level…

2. Use Google Scholar to find the most Relevant Articles (It is way better than your University Database)

Does your university search database suck? I’m yet to find one that doesn’t.

I remember back in the 2008-2012 years when I was an undergrad using my university’s database to search for sources. Let me tell you, I could never find a source that was worth my time! I would even find it hard to find sources on mainstream, well researched topics! My university database would show up irrelevant, pointless sources – if it found any at all!

Even nowadays, University online library search databases suck at finding quality sources.

Google Scholar, on the other hand, is one great intuitive piece of software.

The reason? Most universities:

a) Don’t have access to a wide range of Journals. Each journal costs the university an annual fee of several thousand dollars. I get emails from my university regularly asking me whether it’s really worthwhile renewing a subscription to X, Y, or Z journal. I’m also constantly told that I can’t recommend articles to my students because the university doesn’t have access to those articles. But you know who probably does? Google Scholar!

b) They also don’t have an intuitive search brain. The university databases often only search for keywords in the article title. By contrast, Google Scholar searches for keywords not only in the title but also the abstract. This dramatically increases your search net and finds you articles that are more relevant to you. Thanks, Google Scholar!

3. Use Google Scholar to bypass Paywalls

Most quality scholarly articles are blocked behind paywalls. The way you get access to them is that your university pays a yearly fee to get access (see Point 2).

Google Scholar has intuitively crawled the web looking for ways to get around Journal paywalls. And, frankly, it does a really good job.

These days scholars who publish articles behind paywalls also make copies available via their own university websites or on sites like ResearchGate.net and Academia.edu. Google finds those articles for you and gives you one-click access.

Here’s how you can take advantage of that: pay special attention to the [PDF] and [HTML] links on the right-hand side of the search results. All sources that you can have direct access to will have this link.

So, if you’re in a hurry, don’t pay attention to any others – just start looking for sources with those PDF and HTML links so you don’t waste time looking for articles you don’t have access to.

Fortunately, these days more than 50% of articles can be accessed without paywalls, all thanks to Google Scholar.

4. Link Up Google Scholar with your University Database

Okay, there’s still a purpose for your University search database. Here it is:

Google Scholar doesn’t technically have paid access to any Journals. I’ll explain to you how and why it gives you free access to so many articles in Point 4.

But it’s true, sometimes Google Scholar just can’t find you the full text of a source. Nonetheless, as I pointed out in Point 3, Google Scholar is still better at finding quality sources, even if it can’t give you access to them.

So, you should let Google Scholar know that you are attached to a University that might give you access. Then, Google Scholar will let you know if your university database can help you out.

Here’s what to do:

- Go to ‘Settings’ and ‘Library Links’.

- Enter your University’s name.

- Click Search.

- Check the box that shows your university database.

- Click Save.

- Then, go back and search for articles on Google Scholar (because it’s the best search engine for Scholarly sources!).

- Then, when you find articles that you think you want, see if Google Scholar can give you access (see Point 3 above)

- If it can’t, you should now have access to your University Database to see if your University can give you access in just one click.

5. Narrow your Search to Sources from the Past 10 Years

Has your teacher ever told you to only cite sources from the past 10 years? That’s a pretty solid piece of advice.

Google Scholar makes this so easy.

Simply conduct your search, then on the left-hand sidebar, click ‘Custom Range’ and narrow the search range to the past 10 years:

Done! Couldn’t be easier. Aren’t you glad you know how to use Google Scholar?

6. Use the ‘Cited By’ Method to find Newer (and more Relevant) Articles

Here’s where Google Scholar really comes into its own.

Let’s say you just couldn’t find a relevant source from the past 10 years. Sometimes it’s impossible!

There’s still a way around it.

Simply find an older source that still looks awesome and press the ‘Cited by’ button:

This will take you to all articles that have cited that original article. The upshot of this is that all these articles will have at least some relevance to the original article and will (naturally) also all be newer! This method often helps me find hard-to-reach articles that I can’t find any other way.

Next, to zoom in even more, you can set the custom range to the past 10 years again to find all articles that cite the original text, but happen to be new enough for you to cite!

But wait, there’s more. Let’s say you want to make sure the newer text you search for is still as relevant as possible. If you click ‘search within citing articles’, you can do a new search to find all articles that discuss the keyword you’re interested in and that cite the older text. For this example, I still wanted to look for newer articles like my original one (‘Inequality in Education’) but I also wanted to narrow it down to “gender” inequality. See below where I checked ‘Search within Citing Articles’ before searching ‘gender’:

7. Use Google Scholar to Generate Citations

Referencing is necessary, but tough. People often try to use citation generators online, but I hate citation generators. They never get citations right. And, to be honest, nor does Google Scholar’s. But, it is very convenient and helps me to get the basic skeleton of my citation that I can patch-up to make it right.

Here’s how to use Google Scholar to generate your citations:

1. Find the source you want to cite on Google Scholar.

2. Click the quote symbol beneath the source.

3. Copy the text for the citation style you are using.

4. Check it against a referencing style cheat sheet to make sure all the information is there and in the right spot.

8. Follow Author Links to find a Scholar’s Newest Articles

Another way to find more up-to-date sources is to follow an author’s list of works. When I was doing my PhD, I used an author called Neil Selwyn to examine a range of different ideas related to educational technologies . I therefore needed to be very much up to date with his complete works.

So, I went to Google Scholar, found one of his texts, and then clicked his name:

This took me to his complete list of works. I sorted them by ‘YEAR’, and hey presto! I found all of his newest ideas which I promptly read about and inserted into my thesis to improve my grade:

9. Google Scholar and Google Books work Hand-In-Hand

Google Scholar isn’t just for journal articles . You can also use Google Scholar to find relevant textbooks. Again, thanks to Google, you can read those books right on your computer – for free!

Here’s a book that I think might be relevant to my topic:

Google Scholar tells me it’s a [BOOK] and lets me click the link to go straight to the first page of the book. Sure, it’s a preview, but usually you get a good chunk of the book to read online (and can even search for keywords within the book):

If the link takes you elsewhere, you can always go to Google Books and search the full title of the book there to see if you can get access to a preview.

10. Bookmark Important Articles for Future Assignments

Sometimes one book comes in useful throughout your whole degree. My Education Studies students constantly cite a book by L. Pound that gives a really nice overview of a range of approaches to teaching. It’s a worthwhile book that students can go to in order to get great information.

So, my students often save this book in their Google Scholar bookmarks library for quick access. Simply save any book or article you love by pressing the star button under the title:

To access the books in your library, simply click ‘My Library’ in the top Menu. Here’s the first three articles saved in my library:

11. Create your own Google Scholar Profile

Academics can create their own Google Scholar profiles to claim publications of their own. I do this to claim my publications, but you should do it too – even if you’re not an author.

Because you can add ‘areas of interest’ to help Google Scholar find and recommend sources for you. You can also start to follow authors who are relevant to your studies – especially those authors whose work you use regularly (like L. Pound, who many of my students follow!)

Simply click ‘My Profile’ and then fill in the required questions.

Once you’ve made your profile, add ‘Areas of Interest’ and start following other authors. This will help Google Scholar recommend relevant articles for you in the future: Here’s the ‘Follow’ and ‘Areas of Interest’ links you might find useful:

Can you tell that I absolutely love Google Scholar? It saves time and increases my marks. What’s not to like? You need to know how to use Google Scholar!

In this post I’ve given you the advanced strategies that you need to use Google Scholar like a Pro. Use these strategies to navigate your way around, find top articles, save time, and grow your grades. Here’s a summary of the top 11 ways to use Google Scholar to grow your grades:

How to use Google Scholar Like a Pro

- Ditch Regular Google. Google Scholar Kicks its Butt.

- Use Google Scholar to find the most Relevant Articles (It is way better than your University Database)

- Use Google Scholar to bypass Paywalls

- Link Up Google Scholar with your University Database

- Use the ‘Cited By’ Method to find Newer (and more Relevant) Articles

- Use Google Scholar to Generate Citations

- Follow Author Links to find a Scholar’s Newest Articles

- Google Scholar and Google Books work Hand-In-Hand

- Bookmark Important Articles for Future Assignments

- Create your own Google Scholar Profile

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

1 thought on “11 Best Tips on How to use Google Scholar”

This is very helpful. I am even recommending it to my fellow first year students in Research and Academic Writing. Many thanks.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Reference management. Clean and simple.

The top list of academic search engines

1. Google Scholar

4. science.gov, 5. semantic scholar, 6. baidu scholar, get the most out of academic search engines, frequently asked questions about academic search engines, related articles.

Academic search engines have become the number one resource to turn to in order to find research papers and other scholarly sources. While classic academic databases like Web of Science and Scopus are locked behind paywalls, Google Scholar and others can be accessed free of charge. In order to help you get your research done fast, we have compiled the top list of free academic search engines.

Google Scholar is the clear number one when it comes to academic search engines. It's the power of Google searches applied to research papers and patents. It not only lets you find research papers for all academic disciplines for free but also often provides links to full-text PDF files.

- Coverage: approx. 200 million articles

- Abstracts: only a snippet of the abstract is available

- Related articles: ✔

- References: ✔

- Cited by: ✔

- Links to full text: ✔

- Export formats: APA, MLA, Chicago, Harvard, Vancouver, RIS, BibTeX

BASE is hosted at Bielefeld University in Germany. That is also where its name stems from (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine).

- Coverage: approx. 136 million articles (contains duplicates)

- Abstracts: ✔

- Related articles: ✘

- References: ✘

- Cited by: ✘

- Export formats: RIS, BibTeX

CORE is an academic search engine dedicated to open-access research papers. For each search result, a link to the full-text PDF or full-text web page is provided.

- Coverage: approx. 136 million articles

- Links to full text: ✔ (all articles in CORE are open access)

- Export formats: BibTeX

Science.gov is a fantastic resource as it bundles and offers free access to search results from more than 15 U.S. federal agencies. There is no need anymore to query all those resources separately!

- Coverage: approx. 200 million articles and reports

- Links to full text: ✔ (available for some databases)

- Export formats: APA, MLA, RIS, BibTeX (available for some databases)

Semantic Scholar is the new kid on the block. Its mission is to provide more relevant and impactful search results using AI-powered algorithms that find hidden connections and links between research topics.

- Coverage: approx. 40 million articles

- Export formats: APA, MLA, Chicago, BibTeX

Although Baidu Scholar's interface is in Chinese, its index contains research papers in English as well as Chinese.

- Coverage: no detailed statistics available, approx. 100 million articles

- Abstracts: only snippets of the abstract are available

- Export formats: APA, MLA, RIS, BibTeX

RefSeek searches more than one billion documents from academic and organizational websites. Its clean interface makes it especially easy to use for students and new researchers.

- Coverage: no detailed statistics available, approx. 1 billion documents

- Abstracts: only snippets of the article are available

- Export formats: not available