What Life Was Like for Students in the Pandemic Year

- Share article

In this video, Navajo student Miles Johnson shares how he experienced the stress and anxiety of schools shutting down last year. Miles’ teacher shared his experience and those of her other students in a recent piece for Education Week. In these short essays below, teacher Claire Marie Grogan’s 11th grade students at Oceanside High School on Long Island, N.Y., describe their pandemic experiences. Their writings have been slightly edited for clarity. Read Grogan’s essay .

“Hours Staring at Tiny Boxes on the Screen”

By Kimberly Polacco, 16

I stare at my blank computer screen, trying to find the motivation to turn it on, but my finger flinches every time it hovers near the button. I instead open my curtains. It is raining outside, but it does not matter, I will not be going out there for the rest of the day. The sound of pounding raindrops contributes to my headache enough to make me turn on my computer in hopes that it will give me something to drown out the noise. But as soon as I open it up, I feel the weight of the world crash upon my shoulders.

Each 42-minute period drags on by. I spend hours upon hours staring at tiny boxes on a screen, one of which my exhausted face occupies, and attempt to retain concepts that have been presented to me through this device. By the time I have the freedom of pressing the “leave” button on my last Google Meet of the day, my eyes are heavy and my legs feel like mush from having not left my bed since I woke up.

Tomorrow arrives, except this time here I am inside of a school building, interacting with my first period teacher face to face. We talk about our favorite movies and TV shows to stream as other kids pile into the classroom. With each passing period I accumulate more and more of these tiny meaningless conversations everywhere I go with both teachers and students. They may not seem like much, but to me they are everything because I know that the next time I am expected to report to school, I will be trapped in the bubble of my room counting down the hours until I can sit down in my freshly sanitized wooden desk again.

“My Only Parent Essentially on Her Death Bed”

By Nick Ingargiola, 16

My mom had COVID-19 for ten weeks. She got sick during the first month school buildings were shut. The difficulty of navigating an online classroom was already overwhelming, and when mixed with my only parent essentially on her death bed, it made it unbearable. Focusing on schoolwork was impossible, and watching my mother struggle to lift up her arm broke my heart.

My mom has been through her fair share of diseases from pancreatic cancer to seizures and even as far as a stroke that paralyzed her entire left side. It is safe to say she has been through a lot. The craziest part is you would never know it. She is the strongest and most positive person I’ve ever met. COVID hit her hard. Although I have watched her go through life and death multiple times, I have never seen her so physically and mentally drained.

I initially was overjoyed to complete my school year in the comfort of my own home, but once my mom got sick, I couldn’t handle it. No one knows what it’s like to pretend like everything is OK until they are forced to. I would wake up at 8 after staying up until 5 in the morning pondering the possibility of losing my mother. She was all I had. I was forced to turn my camera on and float in the fake reality of being fine although I wasn’t. The teachers tried to keep the class engaged by obligating the students to participate. This was dreadful. I didn’t want to talk. I had to hide the distress in my voice. If only the teachers understood what I was going through. I was hesitant because I didn’t want everyone to know that the virus that was infecting and killing millions was knocking on my front door.

After my online classes, I was required to finish an immense amount of homework while simultaneously hiding my sadness so that my mom wouldn’t worry about me. She was already going through a lot. There was no reason to add me to her list of worries. I wasn’t even able to give her a hug. All I could do was watch.

“The Way of Staying Sane”

By Lynda Feustel, 16

Entering year two of the pandemic is strange. It barely seems a day since last March, but it also seems like a lifetime. As an only child and introvert, shutting down my world was initially simple and relatively easy. My friends and I had been super busy with the school play, and while I was sad about it being canceled, I was struggling a lot during that show and desperately needed some time off.

As March turned to April, virtual school began, and being alone really set in. I missed my friends and us being together. The isolation felt real with just my parents and me, even as we spent time together. My friends and I began meeting on Facetime every night to watch TV and just be together in some way. We laughed at insane jokes we made and had homework and therapy sessions over Facetime and grew closer through digital and literal walls.

The summer passed with in-person events together, and the virus faded into the background for a little while. We went to the track and the beach and hung out in people’s backyards.

Then school came for us in a more nasty way than usual. In hybrid school we were separated. People had jobs, sports, activities, and quarantines. Teachers piled on work, and the virus grew more present again. The group text put out hundreds of messages a day while the Facetimes came to a grinding halt, and meeting in person as a group became more of a rarity. Being together on video and in person was the way of staying sane.

In a way I am in a similar place to last year, working and looking for some change as we enter the second year of this mess.

“In History Class, Reports of Heightening Cases”

By Vivian Rose, 16

I remember the moment my freshman year English teacher told me about the young writers’ conference at Bread Loaf during my sophomore year. At first, I didn’t want to apply, the deadline had passed, but for some strange reason, the directors of the program extended it another week. It felt like it was meant to be. It was in Vermont in the last week of May when the flowers have awakened and the sun is warm.

I submitted my work, and two weeks later I got an email of my acceptance. I screamed at the top of my lungs in the empty house; everyone was out, so I was left alone to celebrate my small victory. It was rare for them to admit sophomores. Usually they accept submissions only from juniors and seniors.

That was the first week of February 2020. All of a sudden, there was some talk about this strange virus coming from China. We thought nothing of it. Every night, I would fall asleep smiling, knowing that I would be able to go to the exact conference that Robert Frost attended for 42 years.

Then, as if overnight, it seemed the virus had swung its hand and had gripped parts of the country. Every newscast was about the disease. Every day in history, we would look at the reports of heightening cases and joke around that this could never become a threat as big as Dr. Fauci was proposing. Then, March 13th came around--it was the last day before the world seemed to shut down. Just like that, Bread Loaf would vanish from my grasp.

“One Day Every Day Won’t Be As Terrible”

By Nick Wollweber, 17

COVID created personal problems for everyone, some more serious than others, but everyone had a struggle.

As the COVID lock-down took hold, the main thing weighing on my mind was my oldest brother, Joe, who passed away in January 2019 unexpectedly in his sleep. Losing my brother was a complete gut punch and reality check for me at 14 and 15 years old. 2019 was a year of struggle, darkness, sadness, frustration. I didn’t want to learn after my brother had passed, but I had to in order to move forward and find my new normal.

Routine and always having things to do and places to go is what let me cope in the year after Joe died. Then COVID came and gave me the option to let up and let down my guard. I struggled with not wanting to take care of personal hygiene. That was the beginning of an underlying mental problem where I wouldn’t do things that were necessary for everyday life.

My “coping routine” that got me through every day and week the year before was gone. COVID wasn’t beneficial to me, but it did bring out the true nature of my mental struggles and put a name to it. Since COVID, I have been diagnosed with severe depression and anxiety. I began taking antidepressants and going to therapy a lot more.

COVID made me realize that I’m not happy with who I am and that I needed to change. I’m still not happy with who I am. I struggle every day, but I am working towards a goal that one day every day won’t be as terrible.

Coverage of social and emotional learning is supported in part by a grant from the NoVo Foundation, at www.novofoundation.org . Education Week retains sole editorial control over the content of this coverage. A version of this article appeared in the March 31, 2021 edition of Education Week as What Life Was Like for Students in the Pandemic Year

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Our Mission

Covid-19’s Impact on Students’ Academic and Mental Well-Being

The pandemic has revealed—and exacerbated—inequities that hold many students back. Here’s how teachers can help.

The pandemic has shone a spotlight on inequality in America: School closures and social isolation have affected all students, but particularly those living in poverty. Adding to the damage to their learning, a mental health crisis is emerging as many students have lost access to services that were offered by schools.

No matter what form school takes when the new year begins—whether students and teachers are back in the school building together or still at home—teachers will face a pressing issue: How can they help students recover and stay on track throughout the year even as their lives are likely to continue to be disrupted by the pandemic?

New research provides insights about the scope of the problem—as well as potential solutions.

The Achievement Gap Is Likely to Widen

A new study suggests that the coronavirus will undo months of academic gains, leaving many students behind. The study authors project that students will start the new school year with an average of 66 percent of the learning gains in reading and 44 percent of the learning gains in math, relative to the gains for a typical school year. But the situation is worse on the reading front, as the researchers also predict that the top third of students will make gains, possibly because they’re likely to continue reading with their families while schools are closed, thus widening the achievement gap.

To make matters worse, “few school systems provide plans to support students who need accommodations or other special populations,” the researchers point out in the study, potentially impacting students with special needs and English language learners.

Of course, the idea that over the summer students forget some of what they learned in school isn’t new. But there’s a big difference between summer learning loss and pandemic-related learning loss: During the summer, formal schooling stops, and learning loss happens at roughly the same rate for all students, the researchers point out. But instruction has been uneven during the pandemic, as some students have been able to participate fully in online learning while others have faced obstacles—such as lack of internet access—that have hindered their progress.

In the study, researchers analyzed a national sample of 5 million students in grades 3–8 who took the MAP Growth test, a tool schools use to assess students’ reading and math growth throughout the school year. The researchers compared typical growth in a standard-length school year to projections based on students being out of school from mid-March on. To make those projections, they looked at research on the summer slide, weather- and disaster-related closures (such as New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina), and absenteeism.

The researchers predict that, on average, students will experience substantial drops in reading and math, losing roughly three months’ worth of gains in reading and five months’ worth of gains in math. For Megan Kuhfeld, the lead author of the study, the biggest takeaway isn’t that learning loss will happen—that’s a given by this point—but that students will come back to school having declined at vastly different rates.

“We might be facing unprecedented levels of variability come fall,” Kuhfeld told me. “Especially in school districts that serve families with lots of different needs and resources. Instead of having students reading at a grade level above or below in their classroom, teachers might have kids who slipped back a lot versus kids who have moved forward.”

Disproportionate Impact on Students Living in Poverty and Students of Color

Horace Mann once referred to schools as the “great equalizers,” yet the pandemic threatens to expose the underlying inequities of remote learning. According to a 2015 Pew Research Center analysis , 17 percent of teenagers have difficulty completing homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection. For Black students, the number spikes to 25 percent.

“There are many reasons to believe the Covid-19 impacts might be larger for children in poverty and children of color,” Kuhfeld wrote in the study. Their families suffer higher rates of infection, and the economic burden disproportionately falls on Black and Hispanic parents, who are less likely to be able to work from home during the pandemic.

Although children are less likely to become infected with Covid-19, the adult mortality rates, coupled with the devastating economic consequences of the pandemic, will likely have an indelible impact on their well-being.

Impacts on Students’ Mental Health

That impact on well-being may be magnified by another effect of school closures: Schools are “the de facto mental health system for many children and adolescents,” providing mental health services to 57 percent of adolescents who need care, according to the authors of a recent study published in JAMA Pediatrics . School closures may be especially disruptive for children from lower-income families, who are disproportionately likely to receive mental health services exclusively from schools.

“The Covid-19 pandemic may worsen existing mental health problems and lead to more cases among children and adolescents because of the unique combination of the public health crisis, social isolation, and economic recession,” write the authors of that study.

A major concern the researchers point to: Since most mental health disorders begin in childhood, it is essential that any mental health issues be identified early and treated. Left untreated, they can lead to serious health and emotional problems. In the short term, video conferencing may be an effective way to deliver mental health services to children.

Mental health and academic achievement are linked, research shows. Chronic stress changes the chemical and physical structure of the brain, impairing cognitive skills like attention, concentration, memory, and creativity. “You see deficits in your ability to regulate emotions in adaptive ways as a result of stress,” said Cara Wellman, a professor of neuroscience and psychology at Indiana University in a 2014 interview . In her research, Wellman discovered that chronic stress causes the connections between brain cells to shrink in mice, leading to cognitive deficiencies in the prefrontal cortex.

While trauma-informed practices were widely used before the pandemic, they’re likely to be even more integral as students experience economic hardships and grieve the loss of family and friends. Teachers can look to schools like Fall-Hamilton Elementary in Nashville, Tennessee, as a model for trauma-informed practices .

3 Ways Teachers Can Prepare

When schools reopen, many students may be behind, compared to a typical school year, so teachers will need to be very methodical about checking in on their students—not just academically but also emotionally. Some may feel prepared to tackle the new school year head-on, but others will still be recovering from the pandemic and may still be reeling from trauma, grief, and anxiety.

Here are a few strategies teachers can prioritize when the new school year begins:

- Focus on relationships first. Fear and anxiety about the pandemic—coupled with uncertainty about the future—can be disruptive to a student’s ability to come to school ready to learn. Teachers can act as a powerful buffer against the adverse effects of trauma by helping to establish a safe and supportive environment for learning. From morning meetings to regular check-ins with students, strategies that center around relationship-building will be needed in the fall.

- Strengthen diagnostic testing. Educators should prepare for a greater range of variability in student learning than they would expect in a typical school year. Low-stakes assessments such as exit tickets and quizzes can help teachers gauge how much extra support students will need, how much time should be spent reviewing last year’s material, and what new topics can be covered.

- Differentiate instruction—particularly for vulnerable students. For the vast majority of schools, the abrupt transition to online learning left little time to plan a strategy that could adequately meet every student’s needs—in a recent survey by the Education Trust, only 24 percent of parents said that their child’s school was providing materials and other resources to support students with disabilities, and a quarter of non-English-speaking students were unable to obtain materials in their own language. Teachers can work to ensure that the students on the margins get the support they need by taking stock of students’ knowledge and skills, and differentiating instruction by giving them choices, connecting the curriculum to their interests, and providing them multiple opportunities to demonstrate their learning.

How is COVID-19 affecting student learning?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, initial findings from fall 2020, megan kuhfeld , megan kuhfeld senior research scientist - nwea @megankuhfeld jim soland , jim soland assistant professor, school of education and human development - university of virginia, affiliated research fellow - nwea @jsoland beth tarasawa , bt beth tarasawa executive vice president of research - nwea @bethtarasawa angela johnson , aj angela johnson research scientist - nwea erik ruzek , and er erik ruzek research assistant professor, curry school of education - university of virginia karyn lewis karyn lewis director, center for school and student progress - nwea @karynlew.

December 3, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced uncertainty into major aspects of national and global society, including for schools. For example, there is uncertainty about how school closures last spring impacted student achievement, as well as how the rapid conversion of most instruction to an online platform this academic year will continue to affect achievement. Without data on how the virus impacts student learning, making informed decisions about whether and when to return to in-person instruction remains difficult. Even now, education leaders must grapple with seemingly impossible choices that balance health risks associated with in-person learning against the educational needs of children, which may be better served when kids are in their physical schools.

Amidst all this uncertainty, there is growing consensus that school closures in spring 2020 likely had negative effects on student learning. For example, in an earlier post for this blog , we presented our research forecasting the possible impact of school closures on achievement. Based on historical learning trends and prior research on how out-of-school-time affects learning, we estimated that students would potentially begin fall 2020 with roughly 70% of the learning gains in reading relative to a typical school year. In mathematics, students were predicted to show even smaller learning gains from the previous year, returning with less than 50% of typical gains. While these and other similar forecasts presented a grim portrait of the challenges facing students and educators this fall, they were nonetheless projections. The question remained: What would learning trends in actual data from the 2020-21 school year really look like?

With fall 2020 data now in hand , we can move beyond forecasting and begin to describe what did happen. While the closures last spring left most schools without assessment data from that time, thousands of schools began testing this fall, making it possible to compare learning gains in a typical, pre-COVID-19 year to those same gains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using data from nearly 4.4 million students in grades 3-8 who took MAP ® Growth™ reading and math assessments in fall 2020, we examined two primary research questions:

- How did students perform in fall 2020 relative to a typical school year (specifically, fall 2019)?

- Have students made learning gains since schools physically closed in March 2020?

To answer these questions, we compared students’ academic achievement and growth during the COVID-19 pandemic to the achievement and growth patterns observed in 2019. We report student achievement as a percentile rank, which is a normative measure of a student’s achievement in a given grade/subject relative to the MAP Growth national norms (reflecting pre-COVID-19 achievement levels).

To make sure the students who took the tests before and after COVID-19 school closures were demographically similar, all analyses were limited to a sample of 8,000 schools that tested students in both fall 2019 and fall 2020. Compared to all public schools in the nation, schools in the sample had slightly larger total enrollment, a lower percentage of low-income students, and a higher percentage of white students. Since our sample includes both in-person and remote testers in fall 2020, we conducted an initial comparability study of remote and in-person testing in fall 2020. We found consistent psychometric characteristics and trends in test scores for remote and in-person tests for students in grades 3-8, but caution that remote testing conditions may be qualitatively different for K-2 students. For more details on the sample and methodology, please see the technical report accompanying this study.

In some cases, our results tell a more optimistic story than what we feared. In others, the results are as deeply concerning as we expected based on our projections.

Question 1: How did students perform in fall 2020 relative to a typical school year?

When comparing students’ median percentile rank for fall 2020 to those for fall 2019, there is good news to share: Students in grades 3-8 performed similarly in reading to same-grade students in fall 2019. While the reason for the stability of these achievement results cannot be easily pinned down, possible explanations are that students read more on their own, and parents are better equipped to support learning in reading compared to other subjects that require more formal instruction.

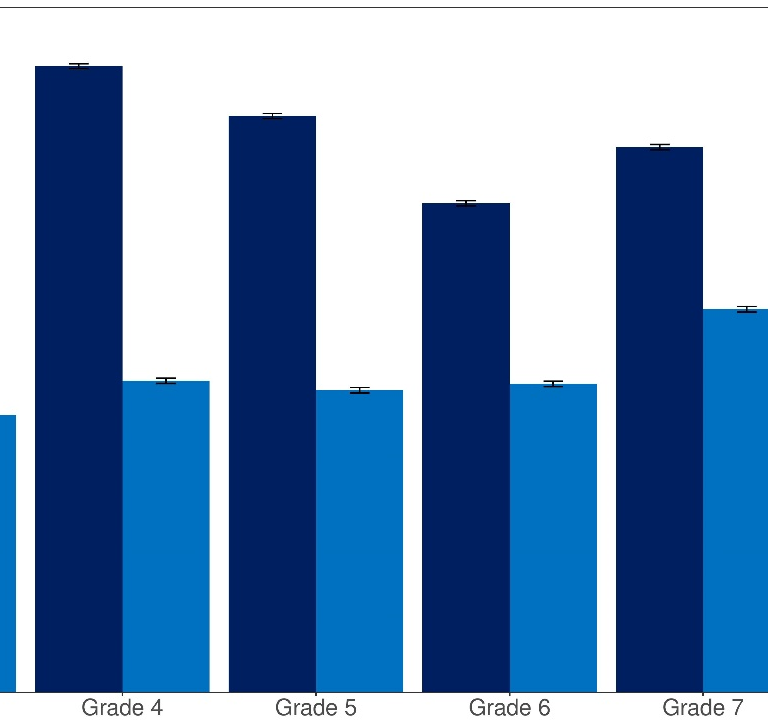

The news in math, however, is more worrying. The figure below shows the median percentile rank in math by grade level in fall 2019 and fall 2020. As the figure indicates, the math achievement of students in 2020 was about 5 to 10 percentile points lower compared to same-grade students the prior year.

Figure 1: MAP Growth Percentiles in Math by Grade Level in Fall 2019 and Fall 2020

Source: Author calculations with MAP Growth data. Notes: Each bar represents the median percentile rank in a given grade/term.

Question 2: Have students made learning gains since schools physically closed, and how do these gains compare to gains in a more typical year?

To answer this question, we examined learning gains/losses between winter 2020 (January through early March) and fall 2020 relative to those same gains in a pre-COVID-19 period (between winter 2019 and fall 2019). We did not examine spring-to-fall changes because so few students tested in spring 2020 (after the pandemic began). In almost all grades, the majority of students made some learning gains in both reading and math since the COVID-19 pandemic started, though gains were smaller in math in 2020 relative to the gains students in the same grades made in the winter 2019-fall 2019 period.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of change in reading scores by grade for the winter 2020 to fall 2020 period (light blue) as compared to same-grade students in the pre-pandemic span of winter 2019 to fall 2019 (dark blue). The 2019 and 2020 distributions largely overlapped, suggesting similar amounts of within-student change from one grade to the next.

Figure 2: Distribution of Within-student Change from Winter 2019-Fall 2019 vs Winter 2020-Fall 2020 in Reading

Source: Author calculations with MAP Growth data. Notes: The dashed line represents zero growth (e.g., winter and fall test scores were equivalent). A positive value indicates that a student scored higher in the fall than their prior winter score; a negative value indicates a student scored lower in the fall than their prior winter score.

Meanwhile, Figure 3 shows the distribution of change for students in different grade levels for the winter 2020 to fall 2020 period in math. In contrast to reading, these results show a downward shift: A smaller proportion of students demonstrated positive math growth in the 2020 period than in the 2019 period for all grades. For example, 79% of students switching from 3 rd to 4 th grade made academic gains between winter 2019 and fall 2019, relative to 57% of students in the same grade range in 2020.

Figure 3: Distribution of Within-student Change from Winter 2019-Fall 2019 vs. Winter 2020-Fall 2020 in Math

It was widely speculated that the COVID-19 pandemic would lead to very unequal opportunities for learning depending on whether students had access to technology and parental support during the school closures, which would result in greater heterogeneity in terms of learning gains/losses in 2020. Notably, however, we do not see evidence that within-student change is more spread out this year relative to the pre-pandemic 2019 distribution.

The long-term effects of COVID-19 are still unknown

In some ways, our findings show an optimistic picture: In reading, on average, the achievement percentiles of students in fall 2020 were similar to those of same-grade students in fall 2019, and in almost all grades, most students made some learning gains since the COVID-19 pandemic started. In math, however, the results tell a less rosy story: Student achievement was lower than the pre-COVID-19 performance by same-grade students in fall 2019, and students showed lower growth in math across grades 3 to 8 relative to peers in the previous, more typical year. Schools will need clear local data to understand if these national trends are reflective of their students. Additional resources and supports should be deployed in math specifically to get students back on track.

In this study, we limited our analyses to a consistent set of schools between fall 2019 and fall 2020. However, approximately one in four students who tested within these schools in fall 2019 are no longer in our sample in fall 2020. This is a sizeable increase from the 15% attrition from fall 2018 to fall 2019. One possible explanation is that some students lacked reliable technology. A second is that they disengaged from school due to economic, health, or other factors. More coordinated efforts are required to establish communication with students who are not attending school or disengaging from instruction to get them back on track, especially our most vulnerable students.

Finally, we are only scratching the surface in quantifying the short-term and long-term academic and non-academic impacts of COVID-19. While more students are back in schools now and educators have more experience with remote instruction than when the pandemic forced schools to close in spring 2020, the collective shock we are experiencing is ongoing. We will continue to examine students’ academic progress throughout the 2020-21 school year to understand how recovery and growth unfold amid an ongoing pandemic.

Thankfully, we know much more about the impact the pandemic has had on student learning than we did even a few months ago. However, that knowledge makes clear that there is work to be done to help many students get back on track in math, and that the long-term ramifications of COVID-19 for student learning—especially among underserved communities—remain unknown.

Related Content

Jim Soland, Megan Kuhfeld, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, Jing Liu

May 27, 2020

Amie Rapaport, Anna Saavedra, Dan Silver, Morgan Polikoff

November 18, 2020

Education Access & Equity K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Rebecca Winthrop, Sweta Shah

May 2, 2024

Jing Liu, Cameron Conrad, David Blazar

May 1, 2024

Online only

7:00 am - 8:00 am EDT

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

20 beautiful college campuses.

Cole Claybourn May 1, 2024

Congress Comes Down on Campus Protests

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 1, 2024

University Leaders in Their Own Words

Laura Mannweiler May 1, 2024

Nationwide Campus Protests Escalate

Laura Mannweiler April 30, 2024

Best Colleges Surveys Are Out

Eric Brooks April 30, 2024

Questions to Ask on a College Visit

Sarah Wood April 30, 2024

Columbia Gives Ultimatum to Protesters

Lauren Camera April 29, 2024

Photos: Pro-Palestinian Student Protests

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton and Avi Gupta April 26, 2024

How to Win a Fulbright Scholarship

Cole Claybourn and Ilana Kowarski April 26, 2024

Honors Colleges and Programs

Sarah Wood April 26, 2024

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Cease-fire will fail as long as Hamas exists, journalist says

Imagining a different Russia

Remember Eric Garner? George Floyd?

Rubén Rodriguez/Unsplash

Time to fix American education with race-for-space resolve

Harvard Staff Writer

Paul Reville says COVID-19 school closures have turned a spotlight on inequities and other shortcomings

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

As former secretary of education for Massachusetts, Paul Reville is keenly aware of the financial and resource disparities between districts, schools, and individual students. The school closings due to coronavirus concerns have turned a spotlight on those problems and how they contribute to educational and income inequality in the nation. The Gazette talked to Reville, the Francis Keppel Professor of Practice of Educational Policy and Administration at Harvard Graduate School of Education , about the effects of the pandemic on schools and how the experience may inspire an overhaul of the American education system.

Paul Reville

GAZETTE: Schools around the country have closed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Do these massive school closures have any precedent in the history of the United States?

REVILLE: We’ve certainly had school closures in particular jurisdictions after a natural disaster, like in New Orleans after the hurricane. But on this scale? No, certainly not in my lifetime. There were substantial closings in many places during the 1918 Spanish Flu, some as long as four months, but not as widespread as those we’re seeing today. We’re in uncharted territory.

GAZETTE: What lessons did school districts around the country learn from school closures in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and other similar school closings?

REVILLE: I think the lessons we’ve learned are that it’s good [for school districts] to have a backup system, if they can afford it. I was talking recently with folks in a district in New Hampshire where, because of all the snow days they have in the wintertime, they had already developed a backup online learning system. That made the transition, in this period of school closure, a relatively easy one for them to undertake. They moved seamlessly to online instruction.

Most of our big systems don’t have this sort of backup. Now, however, we’re not only going to have to construct a backup to get through this crisis, but we’re going to have to develop new, permanent systems, redesigned to meet the needs which have been so glaringly exposed in this crisis. For example, we have always had large gaps in students’ learning opportunities after school, weekends, and in the summer. Disadvantaged students suffer the consequences of those gaps more than affluent children, who typically have lots of opportunities to fill in those gaps. I’m hoping that we can learn some things through this crisis about online delivery of not only instruction, but an array of opportunities for learning and support. In this way, we can make the most of the crisis to help redesign better systems of education and child development.

GAZETTE: Is that one of the silver linings of this public health crisis?

REVILLE: In politics we say, “Never lose the opportunity of a crisis.” And in this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly. There are things we can learn in the messiness of adapting through this crisis, which has revealed profound disparities in children’s access to support and opportunities. We should be asking: How do we make our school, education, and child-development systems more individually responsive to the needs of our students? Why not construct a system that meets children where they are and gives them what they need inside and outside of school in order to be successful? Let’s take this opportunity to end the “one size fits all” factory model of education.

GAZETTE: How seriously are students going to be set back by not having formal instruction for at least two months, if not more?

“The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling,” Paul Reville said of the current situation. “We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

REVILLE: The first thing to consider is that it’s going to be a variable effect. We tend to regard our school systems uniformly, but actually schools are widely different in their operations and impact on children, just as our students themselves are very different from one another. Children come from very different backgrounds and have very different resources, opportunities, and support outside of school. Now that their entire learning lives, as well as their actual physical lives, are outside of school, those differences and disparities come into vivid view. Some students will be fine during this crisis because they’ll have high-quality learning opportunities, whether it’s formal schooling or informal homeschooling of some kind coupled with various enrichment opportunities. Conversely, other students won’t have access to anything of quality, and as a result will be at an enormous disadvantage. Generally speaking, the most economically challenged in our society will be the most vulnerable in this crisis, and the most advantaged are most likely to survive it without losing too much ground.

GAZETTE: Schools in Massachusetts are closed until May 4. Some people are saying they should remain closed through the end of the school year. What’s your take on this?

REVILLE: That should be a medically based judgment call that will be best made several weeks from now. If there’s evidence to suggest that students and teachers can safely return to school, then I’d say by all means. However, that seems unlikely.

GAZETTE: The digital divide between students has become apparent as schools have increasingly turned to online instruction. What can school systems do to address that gap?

REVILLE: Arguably, this is something that schools should have been doing a long time ago, opening up the whole frontier of out-of-school learning by virtue of making sure that all students have access to the technology and the internet they need in order to be connected in out-of-school hours. Students in certain school districts don’t have those affordances right now because often the school districts don’t have the budget to do this, but federal, state, and local taxpayers are starting to see the imperative for coming together to meet this need.

Twenty-first century learning absolutely requires technology and internet. We can’t leave this to chance or the accident of birth. All of our children should have the technology they need to learn outside of school. Some communities can take it for granted that their children will have such tools. Others who have been unable to afford to level the playing field are now finding ways to step up. Boston, for example, has bought 20,000 Chromebooks and is creating hotspots around the city where children and families can go to get internet access. That’s a great start but, in the long run, I think we can do better than that. At the same time, many communities still need help just to do what Boston has done for its students.

Communities and school districts are going to have to adapt to get students on a level playing field. Otherwise, many students will continue to be at a huge disadvantage. We can see this playing out now as our lower-income and more heterogeneous school districts struggle over whether to proceed with online instruction when not everyone can access it. Shutting down should not be an option. We have to find some middle ground, and that means the state and local school districts are going to have to act urgently and nimbly to fill in the gaps in technology and internet access.

GAZETTE : What can parents can do to help with the homeschooling of their children in the current crisis?

“In this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly.”

More like this

The collective effort

Notes from the new normal

‘If you remain mostly upright, you are doing it well enough’

REVILLE: School districts can be helpful by giving parents guidance about how to constructively use this time. The default in our education system is now homeschooling. Virtually all parents are doing some form of homeschooling, whether they want to or not. And the question is: What resources, support, or capacity do they have to do homeschooling effectively? A lot of parents are struggling with that.

And again, we have widely variable capacity in our families and school systems. Some families have parents home all day, while other parents have to go to work. Some school systems are doing online classes all day long, and the students are fully engaged and have lots of homework, and the parents don’t need to do much. In other cases, there is virtually nothing going on at the school level, and everything falls to the parents. In the meantime, lots of organizations are springing up, offering different kinds of resources such as handbooks and curriculum outlines, while many school systems are coming up with guidance documents to help parents create a positive learning environment in their homes by engaging children in challenging activities so they keep learning.

There are lots of creative things that can be done at home. But the challenge, of course, for parents is that they are contending with working from home, and in other cases, having to leave home to do their jobs. We have to be aware that families are facing myriad challenges right now. If we’re not careful, we risk overloading families. We have to strike a balance between what children need and what families can do, and how you maintain some kind of work-life balance in the home environment. Finally, we must recognize the equity issues in the forced overreliance on homeschooling so that we avoid further disadvantaging the already disadvantaged.

GAZETTE: What has been the biggest surprise for you thus far?

REVILLE: One that’s most striking to me is that because schools are closed, parents and the general public have become more aware than at any time in my memory of the inequities in children’s lives outside of school. Suddenly we see front-page coverage about food deficits, inadequate access to health and mental health, problems with housing stability, and access to educational technology and internet. Those of us in education know these problems have existed forever. What has happened is like a giant tidal wave that came and sucked the water off the ocean floor, revealing all these uncomfortable realities that had been beneath the water from time immemorial. This newfound public awareness of pervasive inequities, I hope, will create a sense of urgency in the public domain. We need to correct for these inequities in order for education to realize its ambitious goals. We need to redesign our systems of child development and education. The most obvious place to start for schools is working on equitable access to educational technology as a way to close the digital-learning gap.

GAZETTE: You’ve talked about some concrete changes that should be considered to level the playing field. But should we be thinking broadly about education in some new way?

REVILLE: The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling. We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives. In order for children to come to school ready to learn, they need a wide array of essential supports and opportunities outside of school. And we haven’t done a very good job of providing these. These education prerequisites go far beyond the purview of school systems, but rather are the responsibility of communities and society at large. In order to learn, children need equal access to health care, food, clean water, stable housing, and out-of-school enrichment opportunities, to name just a few preconditions. We have to reconceptualize the whole job of child development and education, and construct systems that meet children where they are and give them what they need, both inside and outside of school, in order for all of them to have a genuine opportunity to be successful.

Within this coronavirus crisis there is an opportunity to reshape American education. The only precedent in our field was when the Sputnik went up in 1957, and suddenly, Americans became very worried that their educational system wasn’t competitive with that of the Soviet Union. We felt vulnerable, like our defenses were down, like a nation at risk. And we decided to dramatically boost the involvement of the federal government in schooling and to increase and improve our scientific curriculum. We decided to look at education as an important factor in human capital development in this country. Again, in 1983, the report “Nation at Risk” warned of a similar risk: Our education system wasn’t up to the demands of a high-skills/high-knowledge economy.

We tried with our education reforms to build a 21st-century education system, but the results of that movement have been modest. We are still a nation at risk. We need another paradigm shift, where we look at our goals and aspirations for education, which are summed up in phrases like “No Child Left Behind,” “Every Student Succeeds,” and “All Means All,” and figure out how to build a system that has the capacity to deliver on that promise of equity and excellence in education for all of our students, and all means all. We’ve got that opportunity now. I hope we don’t fail to take advantage of it in a misguided rush to restore the status quo.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Share this article

You might like.

Times opinion writer Bret Stephens also weighs in on campus unrest in final Middle East Dialogues event

Former ambassador sees two tragedies: Ukraine war and the damage Putin has inflicted on his own country

Mother, uncle of two whose deaths at hands of police officers ignited movement talk about turning pain into activism, keeping hope alive

How old is too old to run?

No such thing, specialist says — but when your body is trying to tell you something, listen

Alcohol is dangerous. So is ‘alcoholic.’

Researcher explains the human toll of language that makes addiction feel worse

Seem like Lyme disease risk is getting worse? It is.

The risk of Lyme disease has increased due to climate change and warmer temperature. A rheumatologist offers advice on how to best avoid ticks while going outdoors.

Mission: Recovering Education in 2021

THE CONTEXT

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused abrupt and profound changes around the world. This is the worst shock to education systems in decades, with the longest school closures combined with looming recession. It will set back progress made on global development goals, particularly those focused on education. The economic crises within countries and globally will likely lead to fiscal austerity, increases in poverty, and fewer resources available for investments in public services from both domestic expenditure and development aid. All of this will lead to a crisis in human development that continues long after disease transmission has ended.

Disruptions to education systems over the past year have already driven substantial losses and inequalities in learning. All the efforts to provide remote instruction are laudable, but this has been a very poor substitute for in-person learning. Even more concerning, many children, particularly girls, may not return to school even when schools reopen. School closures and the resulting disruptions to school participation and learning are projected to amount to losses valued at $10 trillion in terms of affected children’s future earnings. Schools also play a critical role around the world in ensuring the delivery of essential health services and nutritious meals, protection, and psycho-social support. Thus, school closures have also imperilled children’s overall wellbeing and development, not just their learning.

It’s not enough for schools to simply reopen their doors after COVID-19. Students will need tailored and sustained support to help them readjust and catch-up after the pandemic. We must help schools prepare to provide that support and meet the enormous challenges of the months ahead. The time to act is now; the future of an entire generation is at stake.

THE MISSION

Mission objective: To enable all children to return to school and to a supportive learning environment, which also addresses their health and psychosocial well-being and other needs.

Timeframe : By end 2021.

Scope : All countries should reopen schools for complete or partial in-person instruction and keep them open. The Partners - UNESCO , UNICEF , and the World Bank - will join forces to support countries to take all actions possible to plan, prioritize, and ensure that all learners are back in school; that schools take all measures to reopen safely; that students receive effective remedial learning and comprehensive services to help recover learning losses and improve overall welfare; and their teachers are prepared and supported to meet their learning needs.

Three priorities:

1. All children and youth are back in school and receive the tailored services needed to meet their learning, health, psychosocial wellbeing, and other needs.

Challenges : School closures have put children’s learning, nutrition, mental health, and overall development at risk. Closed schools also make screening and delivery for child protection services more difficult. Some students, particularly girls, are at risk of never returning to school.

Areas of action : The Partners will support the design and implementation of school reopening strategies that include comprehensive services to support children’s education, health, psycho-social wellbeing, and other needs.

Targets and indicators

2. All children receive support to catch up on lost learning.

Challenges : Most children have lost substantial instructional time and may not be ready for curricula that were age- and grade- appropriate prior to the pandemic. They will require remedial instruction to get back on track. The pandemic also revealed a stark digital divide that schools can play a role in addressing by ensuring children have digital skills and access.

Areas of action : The Partners will (i) support the design and implementation of large-scale remedial learning at different levels of education, (ii) launch an open-access, adaptable learning assessment tool that measures learning losses and identifies learners’ needs, and (iii) support the design and implementation of digital transformation plans that include components on both infrastructure and ways to use digital technology to accelerate the development of foundational literacy and numeracy skills. Incorporating digital technologies to teach foundational skills could complement teachers’ efforts in the classroom and better prepare children for future digital instruction.

While incorporating remedial education, social-emotional learning, and digital technology into curricula by the end of 2021 will be a challenge for most countries, the Partners agree that these are aspirational targets that they should be supporting countries to achieve this year and beyond as education systems start to recover from the current crisis.

3. All teachers are prepared and supported to address learning losses among their students and to incorporate digital technology into their teaching.

Challenges : Teachers are in an unprecedented situation in which they must make up for substantial loss of instructional time from the previous school year and teach the current year’s curriculum. They must also protect their own health in school. Teachers will need training, coaching, and other means of support to get this done. They will also need to be prioritized for the COVID-19 vaccination, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations. School closures also demonstrated that in addition to digital skills, teachers may also need support to adapt their pedagogy to deliver instruction remotely.

Areas of action : The Partners will advocate for teachers to be prioritized in COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations, and provide capacity-development on pedagogies for remedial learning and digital and blended teaching approaches.

Country level actions and global support

UNESCO, UNICEF, and World Bank are joining forces to support countries to achieve the Mission, leveraging their expertise and actions on the ground to support national efforts and domestic funding.

Country Level Action

1. Mobilize team to support countries in achieving the three priorities

The Partners will collaborate and act at the country level to support governments in accelerating actions to advance the three priorities.

2. Advocacy to mobilize domestic resources for the three priorities

The Partners will engage with governments and decision-makers to prioritize education financing and mobilize additional domestic resources.

Global level action

1. Leverage data to inform decision-making

The Partners will join forces to conduct surveys; collect data; and set-up a global, regional, and national real-time data-warehouse. The Partners will collect timely data and analytics that provide access to information on school re-openings, learning losses, drop-outs, and transition from school to work, and will make data available to support decision-making and peer-learning.

2. Promote knowledge sharing and peer-learning in strengthening education recovery

The Partners will join forces in sharing the breadth of international experience and scaling innovations through structured policy dialogue, knowledge sharing, and peer learning actions.

The time to act on these priorities is now. UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank are partnering to help drive that action.

Last Updated: Mar 30, 2021

- (BROCHURE, in English) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BLOG) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Arabic) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- World Bank Education and COVID-19

- World Bank Blogs on Education

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- Current Issue

- Journal Archive

- Current Call

Search form

Coronavirus: My Experience During the Pandemic

Anastasiya Kandratsenka George Washington High School, Class of 2021

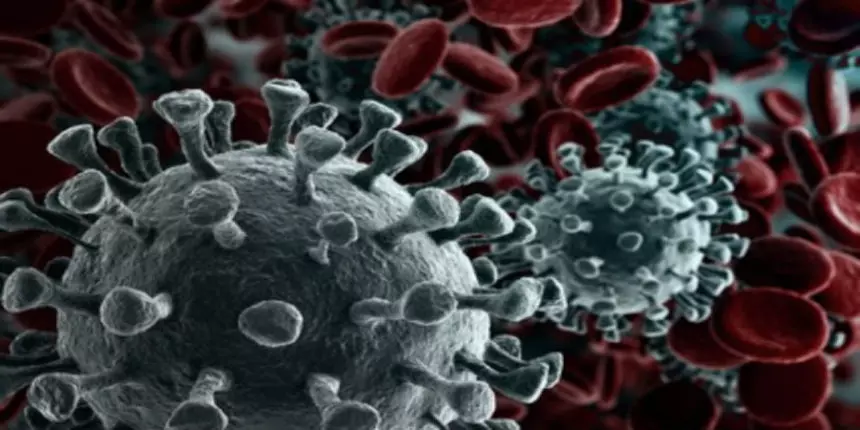

At this point in time there shouldn't be a single person who doesn't know about the coronavirus, or as they call it, COVID-19. The coronavirus is a virus that originated in China, reached the U.S. and eventually spread all over the world by January of 2020. The common symptoms of the virus include shortness of breath, chills, sore throat, headache, loss of taste and smell, runny nose, vomiting and nausea. As it has been established, it might take up to 14 days for the symptoms to show. On top of that, the virus is also highly contagious putting all age groups at risk. The elderly and individuals with chronic diseases such as pneumonia or heart disease are in the top risk as the virus attacks the immune system.

The virus first appeared on the news and media platforms in the month of January of this year. The United States and many other countries all over the globe saw no reason to panic as it seemed that the virus presented no possible threat. Throughout the next upcoming months, the virus began to spread very quickly, alerting health officials not only in the U.S., but all over the world. As people started digging into the origin of the virus, it became clear that it originated in China. Based on everything scientists have looked at, the virus came from a bat that later infected other animals, making it way to humans. As it goes for the United States, the numbers started rising quickly, resulting in the cancellation of sports events, concerts, large gatherings and then later on schools.

As it goes personally for me, my school was shut down on March 13th. The original plan was to put us on a two weeks leave, returning on March 30th but, as the virus spread rapidly and things began escalating out of control very quickly, President Trump announced a state of emergency and the whole country was put on quarantine until April 30th. At that point, schools were officially shut down for the rest of the school year. Distanced learning was introduced, online classes were established, a new norm was put in place. As for the School District of Philadelphia distanced learning and online classes began on May 4th. From that point on I would have classes four times a week, from 8AM till 3PM. Virtual learning was something that I never had to experience and encounter before. It was all new and different for me, just as it was for millions of students all over the United States. We were forced to transfer from physically attending school, interacting with our peers and teachers, participating in fun school events and just being in a classroom setting, to just looking at each other through a computer screen in a number of days. That is something that we all could have never seen coming, it was all so sudden and new.

My experience with distanced learning was not very great. I get distracted very easily and find it hard to concentrate, especially when it comes to school. In a classroom I was able to give my full attention to what was being taught, I was all there. However, when we had the online classes, I could not focus and listen to what my teachers were trying to get across. I got distracted very easily, missing out on important information that was being presented. My entire family which consists of five members, were all home during the quarantine. I have two little siblings who are very loud and demanding, so I’m sure it can be imagined how hard it was for me to concentrate on school and do what was asked of me when I had these two running around the house. On top of school, I also had to find a job and work 35 hours a week to support my family during the pandemic. My mother lost her job for the time being and my father was only able to work from home. As we have a big family, the income of my father was not enough. I made it my duty to help out and support our family as much as I could: I got a job at a local supermarket and worked there as a cashier for over two months.

While I worked at the supermarket, I was exposed to dozens of people every day and with all the protection that was implemented to protect the customers and the workers, I was lucky enough to not get the virus. As I say that, my grandparents who do not even live in the U.S. were not so lucky. They got the virus and spent over a month isolated, in a hospital bed, with no one by their side. Our only way of communicating was through the phone and if lucky, we got to talk once a week. Speaking for my family, that was the worst and scariest part of the whole situation. Luckily for us, they were both able to recover completely.

As the pandemic is somewhat under control, the spread of the virus has slowed down. We’re now living in the new norm. We no longer view things the same, the way we did before. Large gatherings and activities that require large groups to come together are now unimaginable! Distanced learning is what we know, not to mention the importance of social distancing and having to wear masks anywhere and everywhere we go. This is the new norm now and who knows when and if ever we’ll be able go back to what we knew before. This whole experience has made me realize that we, as humans, tend to take things for granted and don’t value what we have until it is taken away from us.

Articles in this Volume

[tid]: dedication, [tid]: new tools for a new house: transformations for justice and peace in and beyond covid-19, [tid]: black lives matter, intersectionality, and lgbtq rights now, [tid]: the voice of asian american youth: what goes untold, [tid]: beyond words: reimagining education through art and activism, [tid]: voice(s) of a black man, [tid]: embodied learning and community resilience, [tid]: re-imagining professional learning in a time of social isolation: storytelling as a tool for healing and professional growth, [tid]: reckoning: what does it mean to look forward and back together as critical educators, [tid]: leader to leaders: an indigenous school leader’s advice through storytelling about grief and covid-19, [tid]: finding hope, healing and liberation beyond covid-19 within a context of captivity and carcerality, [tid]: flux leadership: leading for justice and peace in & beyond covid-19, [tid]: flux leadership: insights from the (virtual) field, [tid]: hard pivot: compulsory crisis leadership emerges from a space of doubt, [tid]: and how are the children, [tid]: real talk: teaching and leading while bipoc, [tid]: systems of emotional support for educators in crisis, [tid]: listening leadership: the student voices project, [tid]: global engagement, perspective-sharing, & future-seeing in & beyond a global crisis, [tid]: teaching and leadership during covid-19: lessons from lived experiences, [tid]: crisis leadership in independent schools - styles & literacies, [tid]: rituals, routines and relationships: high school athletes and coaches in flux, [tid]: superintendent back-to-school welcome 2020, [tid]: mitigating summer learning loss in philadelphia during covid-19: humble attempts from the field, [tid]: untitled, [tid]: the revolution will not be on linkedin: student activism and neoliberalism, [tid]: why radical self-care cannot wait: strategies for black women leaders now, [tid]: from emergency response to critical transformation: online learning in a time of flux, [tid]: illness methodology for and beyond the covid era, [tid]: surviving black girl magic, the work, and the dissertation, [tid]: cancelled: the old student experience, [tid]: lessons from liberia: integrating theatre for development and youth development in uncertain times, [tid]: designing a more accessible future: learning from covid-19, [tid]: the construct of standards-based education, [tid]: teachers leading teachers to prepare for back to school during covid, [tid]: using empathy to cross the sea of humanity, [tid]: (un)doing college, community, and relationships in the time of coronavirus, [tid]: have we learned nothing, [tid]: choosing growth amidst chaos, [tid]: living freire in pandemic….participatory action research and democratizing knowledge at knowledgedemocracy.org, [tid]: philly students speak: voices of learning in pandemics, [tid]: the power of will: a letter to my descendant, [tid]: photo essays with students, [tid]: unity during a global pandemic: how the fight for racial justice made us unite against two diseases, [tid]: educational changes caused by the pandemic and other related social issues, [tid]: online learning during difficult times, [tid]: fighting crisis: a student perspective, [tid]: the destruction of soil rooted with culture, [tid]: a demand for change, [tid]: education through experience in and beyond the pandemics, [tid]: the pandemic diaries, [tid]: all for one and 4 for $4, [tid]: tiktok activism, [tid]: why digital learning may be the best option for next year, [tid]: my 2020 teen experience, [tid]: living between two pandemics, [tid]: journaling during isolation: the gold standard of coronavirus, [tid]: sailing through uncertainty, [tid]: what i wish my teachers knew, [tid]: youthing in pandemic while black, [tid]: the pain inflicted by indifference, [tid]: education during the pandemic, [tid]: the good, the bad, and the year 2020, [tid]: racism fueled pandemic, [tid]: coronavirus: my experience during the pandemic, [tid]: the desensitization of a doomed generation, [tid]: a philadelphia war-zone, [tid]: the attack of the covid monster, [tid]: back-to-school: covid-19 edition, [tid]: the unexpected war, [tid]: learning outside of the classroom, [tid]: why we should learn about college financial aid in school: a student perspective, [tid]: flying the plane as we go: building the future through a haze, [tid]: my covid experience in the age of technology, [tid]: we, i, and they, [tid]: learning your a, b, cs during a pandemic, [tid]: quarantine: a musical, [tid]: what it’s like being a high school student in 2020, [tid]: everything happens for a reason, [tid]: blacks live matter – a sobering and empowering reality among my peers, [tid]: the mental health of a junior during covid-19 outbreaks, [tid]: a year of change, [tid]: covid-19 and school, [tid]: the virtues and vices of virtual learning, [tid]: college decisions and the year 2020: a virtual rollercoaster, [tid]: quarantine thoughts, [tid]: quarantine through generation z, [tid]: attending online school during a pandemic.

Report accessibility issues and request help

Copyright 2024 The University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education's Online Urban Education Journal

School Wasn’t So Great Before COVID, Either

Yes, remote schooling has been a misery—but it’s offering a rare chance to rethink early education entirely.

T he litany of tragedies and inconveniences visited upon Americans by COVID-19 is long, but one of the more pronounced sources of misery for parents has been pandemic schooling. The logistical gymnastics necessary to balance work and school when all the crucial resources—time, physical space, internet bandwidth, emotional reserves—are limited have pushed many to the point of despair.

Pandemic school is clearly not working well, especially for younger children—and it’s all but impossible for the 20 percent of American students who lack access to the technology needed for remote learning. But what parents are coming to understand about their kids’ education—glimpsed through Zoom windows and “asynchronous” classwork—is that school was not always working so great before COVID-19 either. Like a tsunami that pulls away from the coast, leaving an exposed stretch of land, the pandemic has revealed long-standing inattention to children’s developmental needs—needs as basic as exercise, outdoor time, conversation, play, even sleep. All of the challenges of educating young children that we have minimized for years have suddenly appeared like flotsam on a beach at low tide, reeking and impossible to ignore. Parents are not only seeing how flawed and glitch-riddled remote teaching is—they’re discovering that many of the problems of remote schooling are merely exacerbations of problems with in-person schooling.

Emily Gould: Remote learning is a bad joke

It’s remarkable how little schools have changed over time; most public elementary schools are stuck with a model that hasn’t evolved to reflect advances in cognitive science and our understanding of human development. When I walked into my 10-year-old son’s fourth-grade classroom a year ago, it looked almost exactly like my now-28-year-old son’s classroom in 2001, which in turn looked strikingly like my own fourth-grade classroom in 1972. They all had the same configuration of desks, cubbies, and rigidly grade-specific accoutrements. The school schedule also remains much the same: 35 hours of weekly instructional time for about 180 days. The same homework, too, despite the growing wealth of evidence suggesting that homework for elementary-school children (aside from nightly reading) offers minimal or no benefits. Elementary education also values relatively superficial learning that’s too focused on achieving mastery of shallow (but test-friendly) skills unmoored from real content knowledge or critical thinking. School hours are marked by disruptions and noise as students shift, mostly en masse and in age-stratified groups, from one strictly demarcated topic or task to another. Many educators and child-development experts believe that some of the still-standard features of pre‑K and elementary education—age and ability cohorts, short classroom periods, confinement mostly indoors—are not working for many children. And much of what has changed—less face time with teachers, assignments on iPads or computers, a narrowed curriculum—has arguably made things worse.

As distance learning has (literally) brought home these realities about how we educate young children, an opportunity to do things better presents itself—not just for the duration of the pandemic but afterward as well.

Ever since it became clear last spring that school closures would be protracted, we’ve heard an outpouring of concern about potential learning loss and other serious costs for kids, including undetected child abuse and hunger. For a sizable fraction of children—those with disabilities whose educational needs can’t be met remotely, and the millions of kids eligible for free or reduced-price lunch who weren’t fed during the spring and summer—that concern has obvious merit. A McKinsey analysis concluded that if remote learning continues into 2021, students will suffer an average of seven months of “learning loss”—in essence, they’ll be seven months behind in mastering certain concepts and skills. Latino and Black students will fall a little further behind, McKinsey found, and low-income students will lose more than a year. A report out of the Brookings Institution in the spring projected that an extended break from in-person school could cause a “COVID Slide,” in which third-to-eighth-grade students could lose a substantial portion of the progress they would have been expected to make in math and reading.

Recommended Reading

The New Preschool Is Crushing Kids

The Dangers of Distracted Parenting

A Journey Into the Animal Mind