News from the Columbia Climate School

Future of Food: Exploring Challenges to Global Food Systems

Mahak Agrawal

Food is fuel to human existence, and in the evolution of human settlements, food— its production, availability, demand and supply — and food systems have steered the development, expansion and decline of human settlements.

In the 21st century, global food systems face dual challenges of increasing food demand while competing for resources — such as land, water, and energy — that affect food supply. In context of climate change and unpredictable shocks, such as a global pandemic, the need for resiliency in global food systems has become more pressing than ever.

With the globalization of food systems in 1950s, the global food production and associated trade has witnessed a sustained growth, and continues to be driven by advancements in transport and communications, reduction in trade barriers and agricultural tariffs. But, the effectiveness of global food system is undermined by two key challenges: waste and nutrition.

Food wastage is common across all stages of the food chain. Nearly 13.8% of food is lost in supply chains — from harvesting to transport to storage to processing. However, limited research and scientific understanding of price elasticity of food waste makes it tough to evaluate how food waste can be reduced with pricing strategy.

When food is wasted, so are the energy, land, and resources that were used to create it . Nearly 23% of total anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions between 2007-2016 were derived from agriculture, forestry and other land uses. Apart from cultivation and livestock rearing, agriculture also adds emissions through land clearance for cultivation. Overfishing, soil erosion, and depletion and deterioration of aquifers threaten food security. At the same time, food production faces increasing risks from climate change — particularly droughts, increasing frequency of storms, and other extreme weather events.

The world has made significant progress in reducing hunger in the past 50 years. Yet there are nearly 800 million people without access to adequate food. Additionally, two billion people are affected by hidden hunger wherein people lack key micronutrients such as iron, zinc, vitamin A and iodine. Apart from nutrient deficiency, approximately two billion people are overweight and affected by chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

In essence, the global food system is inadequate in delivering the changing and increasing demands of the human population. The system requires an upgrade that takes into account the social-cultural interactions, changing diets, increasing wealth and wealth gap, finite resources, challenges of inequitable access, and the needs of the disadvantaged who spend the greatest proportion of their income on food. To feed the projected 10 billion people by 2050, it is essential to increase and stabilize global food trade and simultaneously align the food demand and supply chains across different geographies and at various scales of space and time.

Back in 1798, Thomas Robert Malthus, in his essay on the principle of population, concluded that “ the power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must come in some shape or other visit the human race .” Malthus projected that short-term gains in living standards would eventually be undermined as human population growth outstripped food production, thereby pushing back living standards towards subsistence.

Malthus’ projections were based on a model where population grew geometrically, while food production increased arithmetically. While Malthus emphasized the importance of land in population-food production dynamics, he understated the role of technology in augmenting total production and family planning in reducing fertility rates. Nonetheless, one cannot banish the Malthusian specter; food production and population are closely intertwined. This close relationship, however, is also affected by changing and improving diets in developing countries and biofuel production — factors that increase the global demand for food and feed.

Around the world, enough food is produced to feed the planet and provide 3,000 calories of nutritious food to each human being every day. In the story of global food systems once defined by starvation and death to now feeding the world, there have been a few ratchets — technologies and innovations that helped the human species transition from hunters and gatherers to shoppers in a supermarket . While some of these ratchets have helped improve and expand the global food systems, some create new opportunities for environmental damage.

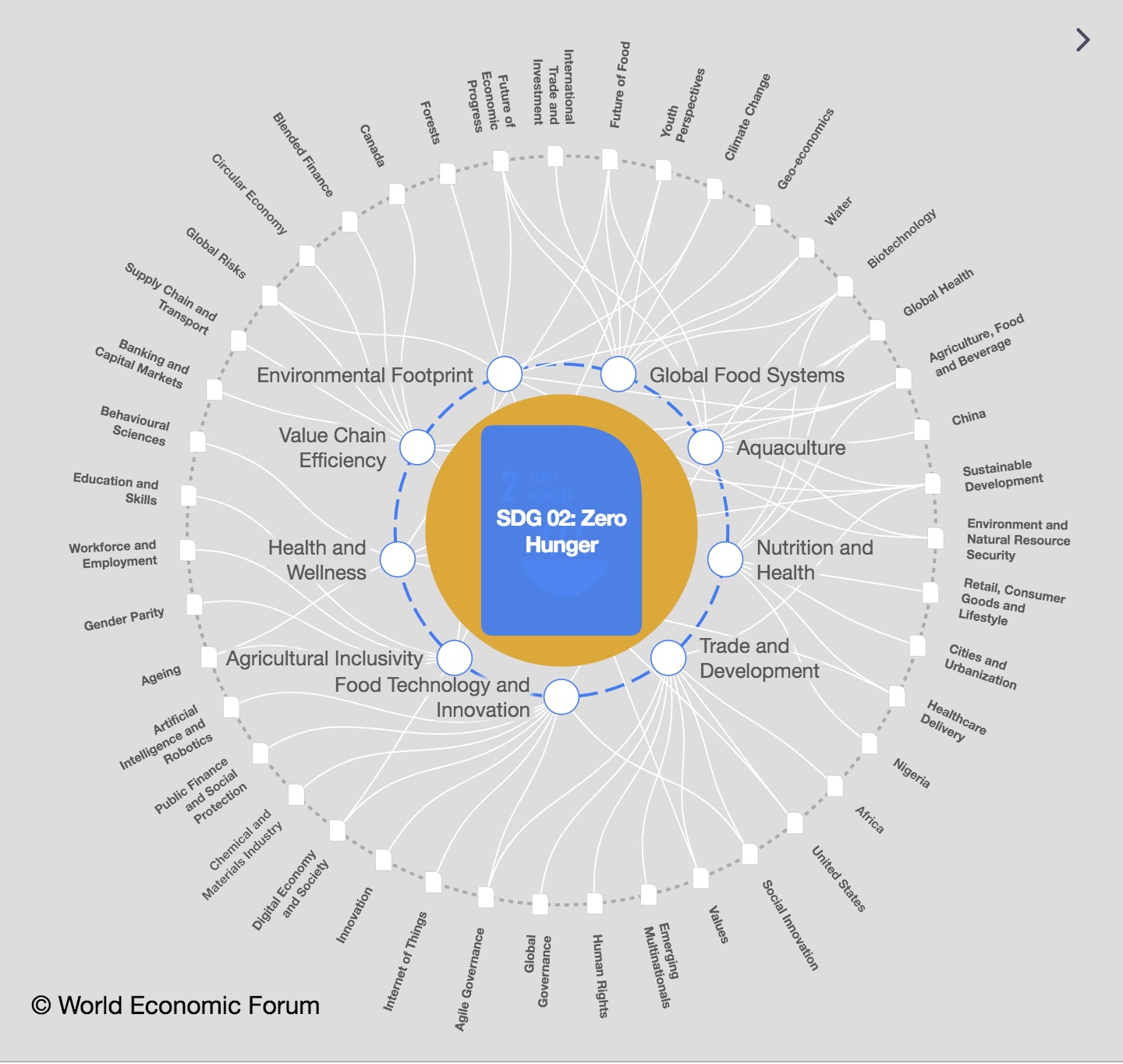

To sum it up, the future of global food systems is strongly interlinked to the planning, management and development of sustainable, equitable and healthy food systems delivering food and nutrition security for all. A bundle of interventions and stimulus packages are needed at both the supply and demand ends to feed the world in the present as well as the future — sustainably, within the planetary boundaries defining a safe operating space for humanity. It requires an intersectoral policy analysis, multi-stakeholder engagement — involving farms, retailers, food processors, technology providers, financial institutions, government agencies, consumers — and interdisciplinary actions.

This blog post is based on an independent study — Future of Food: Examining the supply-demand chains feeding the world — led by Mahak Agrawal in fall 2020 under the guidance of Steven Cohen.

Mahak Agrawal is a medical candidate turned urban planner, exploring innovative, implementable, impactful solutions for pressing urban-regional challenges in her diverse works. Presently, she is studying environmental science and policy at Columbia University as a Shardashish Interschool Fellow and SIPA Environmental Fellow. In different capacities, Mahak has worked with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Town and Country Planning Organization-Government of India, Institute of Transport Economics, Oslo. In 2019, she founded Spatial Perspectives as an initiative that uses the power of digital storytelling and open data to dismantle myths and faulty perspectives associated with spaces around the world. In her spare time, Mahak creates sustainable artwork to tell tales of environmental crisis.

Related Posts

All in the Family: One Environmental Science and Policy Student’s Path to Columbia

Why New Yorkers Long for the Natural World

Environmental Science and Policy Program Seeks Teaching Assistants for Summer 2024

Congratulations to our Columbia Climate School MA in Climate & Society Class of 2024! Learn about our May 10 Class Day celebration. #ColumbiaClimate2024

I’m doing an assignment on food production, ad I just happened to come across this article! Wow, what a lucky find! I’m going to use it for some information in my paragraphs.

it’s more better to have new fruits and reduce human and other thing more thing that you can do.

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter

- Social Justice

- Environment

- Health & Happiness

- Get YES! Emails

- Teacher Resources

- Give A Gift Subscription

- Teaching Sustainability

- Teaching Social Justice

- Teaching Respect & Empathy

- Student Writing Lessons

- Visual Learning Lessons

- Tough Topics Discussion Guides

- About the YES! for Teachers Program

- Student Writing Contest

Follow YES! For Teachers

Six brilliant student essays on the power of food to spark social change.

Read winning essays from our fall 2018 “Feeding Ourselves, Feeding Our Revolutions,” student writing contest.

For the Fall 2018 student writing competition, “Feeding Ourselves, Feeding Our Revolutions,” we invited students to read the YES! Magazine article, “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” by Korsha Wilson and respond to this writing prompt: If you were to host a potluck or dinner to discuss a challenge facing your community or country, what food would you cook? Whom would you invite? On what issue would you deliberate?

The Winners

From the hundreds of essays written, these six—on anti-Semitism, cultural identity, death row prisoners, coming out as transgender, climate change, and addiction—were chosen as essay winners. Be sure to read the literary gems and catchy titles that caught our eye.

Middle School Winner: India Brown High School Winner: Grace Williams University Winner: Lillia Borodkin Powerful Voice Winner: Paisley Regester Powerful Voice Winner: Emma Lingo Powerful Voice Winner: Hayden Wilson

Literary Gems Clever Titles

Middle School Winner: India Brown

A Feast for the Future

Close your eyes and imagine the not too distant future: The Statue of Liberty is up to her knees in water, the streets of lower Manhattan resemble the canals of Venice, and hurricanes arrive in the fall and stay until summer. Now, open your eyes and see the beautiful planet that we will destroy if we do not do something. Now is the time for change. Our future is in our control if we take actions, ranging from small steps, such as not using plastic straws, to large ones, such as reducing fossil fuel consumption and electing leaders who take the problem seriously.

Hosting a dinner party is an extraordinary way to publicize what is at stake. At my potluck, I would serve linguini with clams. The clams would be sautéed in white wine sauce. The pasta tossed with a light coat of butter and topped with freshly shredded parmesan. I choose this meal because it cannot be made if global warming’s patterns persist. Soon enough, the ocean will be too warm to cultivate clams, vineyards will be too sweltering to grow grapes, and wheat fields will dry out, leaving us without pasta.

I think that giving my guests a delicious meal and then breaking the news to them that its ingredients would be unattainable if Earth continues to get hotter is a creative strategy to initiate action. Plus, on the off chance the conversation gets drastically tense, pasta is a relatively difficult food to throw.

In YES! Magazine’s article, “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” Korsha Wilson says “…beyond the narrow definition of what cooking is, you can see that cooking is and has always been an act of resistance.” I hope that my dish inspires people to be aware of what’s at stake with increasing greenhouse gas emissions and work toward creating a clean energy future.

My guest list for the potluck would include two groups of people: local farmers, who are directly and personally affected by rising temperatures, increased carbon dioxide, drought, and flooding, and people who either do not believe in human-caused climate change or don’t think it affects anyone. I would invite the farmers or farm owners because their jobs and crops are dependent on the weather. I hope that after hearing a farmer’s perspective, climate-deniers would be awakened by the truth and more receptive to the effort to reverse these catastrophic trends.

Earth is a beautiful planet that provides everything we’ll ever need, but because of our pattern of living—wasteful consumption, fossil fuel burning, and greenhouse gas emissions— our habitat is rapidly deteriorating. Whether you are a farmer, a long-shower-taking teenager, a worker in a pollution-producing factory, or a climate-denier, the future of humankind is in our hands. The choices we make and the actions we take will forever affect planet Earth.

India Brown is an eighth grader who lives in New York City with her parents and older brother. She enjoys spending time with her friends, walking her dog, Morty, playing volleyball and lacrosse, and swimming.

High School Winner: Grace Williams

Apple Pie Embrace

It’s 1:47 a.m. Thanksgiving smells fill the kitchen. The sweet aroma of sugar-covered apples and buttery dough swirls into my nostrils. Fragrant orange and rosemary permeate the room and every corner smells like a stroll past the open door of a French bakery. My eleven-year-old eyes water, red with drowsiness, and refocus on the oven timer counting down. Behind me, my mom and aunt chat to no end, fueled by the seemingly self-replenishable coffee pot stashed in the corner. Their hands work fast, mashing potatoes, crumbling cornbread, and covering finished dishes in a thin layer of plastic wrap. The most my tired body can do is sit slouched on the backless wooden footstool. I bask in the heat escaping under the oven door.

As a child, I enjoyed Thanksgiving and the preparations that came with it, but it seemed like more of a bridge between my birthday and Christmas than an actual holiday. Now, it’s a time of year I look forward to, dedicated to family, memories, and, most importantly, food. What I realized as I grew older was that my homemade Thanksgiving apple pie was more than its flaky crust and soft-fruit center. This American food symbolized a rite of passage, my Iraqi family’s ticket to assimilation.

Some argue that by adopting American customs like the apple pie, we lose our culture. I would argue that while American culture influences what my family eats and celebrates, it doesn’t define our character. In my family, we eat Iraqi dishes like mesta and tahini, but we also eat Cinnamon Toast Crunch for breakfast. This doesn’t mean we favor one culture over the other; instead, we create a beautiful blend of the two, adapting traditions to make them our own.

That said, my family has always been more than the “mashed potatoes and turkey” type.

My mom’s family immigrated to the United States in 1976. Upon their arrival, they encountered a deeply divided America. Racism thrived, even after the significant freedoms gained from the Civil Rights Movement a few years before. Here, my family was thrust into a completely unknown world: they didn’t speak the language, they didn’t dress normally, and dinners like riza maraka seemed strange in comparison to the Pop Tarts and Oreos lining grocery store shelves.

If I were to host a dinner party, it would be like Thanksgiving with my Chaldean family. The guests, my extended family, are a diverse people, distinct ingredients in a sweet potato casserole, coming together to create a delicious dish.

In her article “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” Korsha Wilson writes, “each ingredient that we use, every technique, every spice tells a story about our access, our privilege, our heritage, and our culture.” Voices around the room will echo off the walls into the late hours of the night while the hot apple pie steams at the table’s center.

We will play concan on the blanketed floor and I’ll try to understand my Toto, who, after forty years, still speaks broken English. I’ll listen to my elders as they tell stories about growing up in Unionville, Michigan, a predominately white town where they always felt like outsiders, stories of racism that I have the privilege not to experience. While snacking on sunflower seeds and salted pistachios, we’ll talk about the news- how thousands of people across the country are protesting for justice among immigrants. No one protested to give my family a voice.

Our Thanksgiving food is more than just sustenance, it is a physical representation of my family ’s blended and ever-changing culture, even after 40 years in the United States. No matter how the food on our plates changes, it will always symbolize our sense of family—immediate and extended—and our unbreakable bond.

Grace Williams, a student at Kirkwood High School in Kirkwood, Missouri, enjoys playing tennis, baking, and spending time with her family. Grace also enjoys her time as a writing editor for her school’s yearbook, the Pioneer. In the future, Grace hopes to continue her travels abroad, as well as live near extended family along the sunny beaches of La Jolla, California.

University Winner: Lillia Borodkin

Nourishing Change After Tragedy Strikes

In the Jewish community, food is paramount. We often spend our holidays gathered around a table, sharing a meal and reveling in our people’s story. On other sacred days, we fast, focusing instead on reflection, atonement, and forgiveness.

As a child, I delighted in the comfort of matzo ball soup, the sweetness of hamantaschen, and the beauty of braided challah. But as I grew older and more knowledgeable about my faith, I learned that the origins of these foods are not rooted in joy, but in sacrifice.

The matzo of matzo balls was a necessity as the Jewish people did not have time for their bread to rise as they fled slavery in Egypt. The hamantaschen was an homage to the hat of Haman, the villain of the Purim story who plotted the Jewish people’s destruction. The unbaked portion of braided challah was tithed by commandment to the kohen or priests. Our food is an expression of our history, commemorating both our struggles and our triumphs.

As I write this, only days have passed since eleven Jews were killed at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh. These people, intending only to pray and celebrate the Sabbath with their community, were murdered simply for being Jewish. This brutal event, in a temple and city much like my own, is a reminder that anti-Semitism still exists in this country. A reminder that hatred of Jews, of me, my family, and my community, is alive and flourishing in America today. The thought that a difference in religion would make some believe that others do not have the right to exist is frightening and sickening.

This is why, if given the chance, I would sit down the entire Jewish American community at one giant Shabbat table. I’d serve matzo ball soup, pass around loaves of challah, and do my best to offer comfort. We would take time to remember the beautiful souls lost to anti-Semitism this October and the countless others who have been victims of such hatred in the past. I would then ask that we channel all we are feeling—all the fear, confusion, and anger —into the fight.

As suggested in Korsha Wilson’s “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” I would urge my guests to direct our passion for justice and the comfort and care provided by the food we are eating into resisting anti-Semitism and hatred of all kinds.

We must use the courage this sustenance provides to create change and honor our people’s suffering and strength. We must remind our neighbors, both Jewish and non-Jewish, that anti-Semitism is alive and well today. We must shout and scream and vote until our elected leaders take this threat to our community seriously. And, we must stand with, support, and listen to other communities that are subjected to vengeful hate today in the same way that many of these groups have supported us in the wake of this tragedy.

This terrible shooting is not the first of its kind, and if conflict and loathing are permitted to grow, I fear it will not be the last. While political change may help, the best way to target this hate is through smaller-scale actions in our own communities.

It is critical that we as a Jewish people take time to congregate and heal together, but it is equally necessary to include those outside the Jewish community to build a powerful crusade against hatred and bigotry. While convening with these individuals, we will work to end the dangerous “otherizing” that plagues our society and seek to understand that we share far more in common than we thought. As disagreements arise during our discussions, we will learn to respect and treat each other with the fairness we each desire. Together, we shall share the comfort, strength, and courage that traditional Jewish foods provide and use them to fuel our revolution.

We are not alone in the fight despite what extremists and anti-semites might like us to believe. So, like any Jew would do, I invite you to join me at the Shabbat table. First, we will eat. Then, we will get to work.

Lillia Borodkin is a senior at Kent State University majoring in Psychology with a concentration in Child Psychology. She plans to attend graduate school and become a school psychologist while continuing to pursue her passion for reading and writing. Outside of class, Lillia is involved in research in the psychology department and volunteers at the Women’s Center on campus.

Powerful Voice Winner: Paisley Regester

As a kid, I remember asking my friends jokingly, ”If you were stuck on a deserted island, what single item of food would you bring?” Some of my friends answered practically and said they’d bring water. Others answered comically and said they’d bring snacks like Flamin’ Hot Cheetos or a banana. However, most of my friends answered sentimentally and listed the foods that made them happy. This seems like fun and games, but what happens if the hypothetical changes? Imagine being asked, on the eve of your death, to choose the final meal you will ever eat. What food would you pick? Something practical? Comical? Sentimental?

This situation is the reality for the 2,747 American prisoners who are currently awaiting execution on death row. The grim ritual of “last meals,” when prisoners choose their final meal before execution, can reveal a lot about these individuals and what they valued throughout their lives.

It is difficult for us to imagine someone eating steak, lobster tail, apple pie, and vanilla ice cream one moment and being killed by state-approved lethal injection the next. The prisoner can only hope that the apple pie he requested tastes as good as his mom’s. Surprisingly, many people in prison decline the option to request a special last meal. We often think of food as something that keeps us alive, so is there really any point to eating if someone knows they are going to die?

“Controlling food is a means of controlling power,” said chef Sean Sherman in the YES! Magazine article “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” by Korsha Wilson. There are deeper stories that lie behind the final meals of individuals on death row.

I want to bring awareness to the complex and often controversial conditions of this country’s criminal justice system and change the common perception of prisoners as inhuman. To accomplish this, I would host a potluck where I would recreate the last meals of prisoners sentenced to death.

In front of each plate, there would be a place card with the prisoner’s full name, the date of execution, and the method of execution. These meals could range from a plate of fried chicken, peas with butter, apple pie, and a Dr. Pepper, reminiscent of a Sunday dinner at Grandma’s, to a single olive.

Seeing these meals up close, meals that many may eat at their own table or feed to their own kids, would force attendees to face the reality of the death penalty. It will urge my guests to look at these individuals not just as prisoners, assigned a number and a death date, but as people, capable of love and rehabilitation.

This potluck is not only about realizing a prisoner’s humanity, but it is also about recognizing a flawed criminal justice system. Over the years, I have become skeptical of the American judicial system, especially when only seven states have judges who ethnically represent the people they serve. I was shocked when I found out that the officers who killed Michael Brown and Anthony Lamar Smith were exonerated for their actions. How could that be possible when so many teens and adults of color have spent years in prison, some even executed, for crimes they never committed?

Lawmakers, police officers, city officials, and young constituents, along with former prisoners and their families, would be invited to my potluck to start an honest conversation about the role and application of inequality, dehumanization, and racism in the death penalty. Food served at the potluck would represent the humanity of prisoners and push people to acknowledge that many inmates are victims of a racist and corrupt judicial system.

Recognizing these injustices is only the first step towards a more equitable society. The second step would be acting on these injustices to ensure that every voice is heard, even ones separated from us by prison walls. Let’s leave that for the next potluck, where I plan to serve humble pie.

Paisley Regester is a high school senior and devotes her life to activism, the arts, and adventure. Inspired by her experiences traveling abroad to Nicaragua, Mexico, and Scotland, Paisley hopes to someday write about the diverse people and places she has encountered and share her stories with the rest of the world.

Powerful Voice Winner: Emma Lingo

The Empty Seat

“If you aren’t sober, then I don’t want to see you on Christmas.”

Harsh words for my father to hear from his daughter but words he needed to hear. Words I needed him to understand and words he seemed to consider as he fiddled with his wine glass at the head of the table. Our guests, my grandma, and her neighbors remained resolutely silent. They were not about to defend my drunken father–or Charles as I call him–from my anger or my ultimatum.

This was the first dinner we had had together in a year. The last meal we shared ended with Charles slopping his drink all over my birthday presents and my mother explaining heroin addiction to me. So, I wasn’t surprised when Charles threw down some liquid valor before dinner in anticipation of my anger. If he wanted to be welcomed on Christmas, he needed to be sober—or he needed to be gone.

Countless dinners, holidays, and birthdays taught me that my demands for sobriety would fall on deaf ears. But not this time. Charles gave me a gift—a one of a kind, limited edition, absolutely awkward treat. One that I didn’t know how to deal with at all. Charles went home that night, smacked a bright red bow on my father, and hand-delivered him to me on Christmas morning.

He arrived for breakfast freshly showered and looking flustered. He would remember this day for once only because his daughter had scolded him into sobriety. Dad teetered between happiness and shame. Grandma distracted us from Dad’s presence by bringing the piping hot bacon and biscuits from the kitchen to the table, theatrically announcing their arrival. Although these foods were the alleged focus of the meal, the real spotlight shined on the unopened liquor cabinet in my grandma’s kitchen—the cabinet I know Charles was begging Dad to open.

I’ve isolated myself from Charles. My family has too. It means we don’t see Dad, but it’s the best way to avoid confrontation and heartache. Sometimes I find myself wondering what it would be like if we talked with him more or if he still lived nearby. Would he be less inclined to use? If all families with an addict tried to hang on to a relationship with the user, would there be fewer addicts in the world? Christmas breakfast with Dad was followed by Charles whisking him away to Colorado where pot had just been legalized. I haven’t talked to Dad since that Christmas.

As Korsha Wilson stated in her YES! Magazine article, “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” “Sometimes what we don’t cook says more than what we do cook.” When it comes to addiction, what isn’t served is more important than what is. In quiet moments, I like to imagine a meal with my family–including Dad. He’d have a spot at the table in my little fantasy. No alcohol would push him out of his chair, the cigarettes would remain seated in his back pocket, and the stench of weed wouldn’t invade the dining room. Fruit salad and gumbo would fill the table—foods that Dad likes. We’d talk about trivial matters in life, like how school is going and what we watched last night on TV.

Dad would feel loved. We would connect. He would feel less alone. At the end of the night, he’d walk me to the door and promise to see me again soon. And I would believe him.

Emma Lingo spends her time working as an editor for her school paper, reading, and being vocal about social justice issues. Emma is active with many clubs such as Youth and Government, KHS Cares, and Peer Helpers. She hopes to be a journalist one day and to be able to continue helping out people by volunteering at local nonprofits.

Powerful Voice Winner: Hayden Wilson

Bittersweet Reunion

I close my eyes and envision a dinner of my wildest dreams. I would invite all of my relatives. Not just my sister who doesn’t ask how I am anymore. Not just my nephews who I’m told are too young to understand me. No, I would gather all of my aunts, uncles, and cousins to introduce them to the me they haven’t met.

For almost two years, I’ve gone by a different name that most of my family refuses to acknowledge. My aunt, a nun of 40 years, told me at a recent birthday dinner that she’d heard of my “nickname.” I didn’t want to start a fight, so I decided not to correct her. Even the ones who’ve adjusted to my name have yet to recognize the bigger issue.

Last year on Facebook, I announced to my friends and family that I am transgender. No one in my family has talked to me about it, but they have plenty to say to my parents. I feel as if this is about my parents more than me—that they’ve made some big parenting mistake. Maybe if I invited everyone to dinner and opened up a discussion, they would voice their concerns to me instead of my parents.

I would serve two different meals of comfort food to remind my family of our good times. For my dad’s family, I would cook heavily salted breakfast food, the kind my grandpa used to enjoy. He took all of his kids to IHOP every Sunday and ordered the least healthy option he could find, usually some combination of an overcooked omelet and a loaded Classic Burger. For my mom’s family, I would buy shakes and burgers from Hardee’s. In my grandma’s final weeks, she let aluminum tins of sympathy meals pile up on her dining table while she made my uncle take her to Hardee’s every day.

In her article on cooking and activism, food writer Korsha Wilson writes, “Everyone puts down their guard over a good meal, and in that space, change is possible.” Hopefully the same will apply to my guests.

When I first thought of this idea, my mind rushed to the endless negative possibilities. My nun-aunt and my two non-nun aunts who live like nuns would whip out their Bibles before I even finished my first sentence. My very liberal, state representative cousin would say how proud she is of the guy I’m becoming, but this would trigger my aunts to accuse her of corrupting my mind. My sister, who has never spoken to me about my genderidentity, would cover her children’s ears and rush them out of the house. My Great-Depression-raised grandparents would roll over in their graves, mumbling about how kids have it easy nowadays.

After mentally mapping out every imaginable terrible outcome this dinner could have, I realized a conversation is unavoidable if I want my family to accept who I am. I long to restore the deep connection I used to have with them. Though I often think these former relationships are out of reach, I won’t know until I try to repair them. For a year and a half, I’ve relied on Facebook and my parents to relay messages about my identity, but I need to tell my own story.

At first, I thought Korsha Wilson’s idea of a cooked meal leading the way to social change was too optimistic, but now I understand that I need to think more like her. Maybe, just maybe, my family could all gather around a table, enjoy some overpriced shakes, and be as close as we were when I was a little girl.

Hayden Wilson is a 17-year-old high school junior from Missouri. He loves writing, making music, and painting. He’s a part of his school’s writing club, as well as the GSA and a few service clubs.

Literary Gems

We received many outstanding essays for the Fall 2018 Writing Competition. Though not every participant can win the contest, we’d like to share some excerpts that caught our eye.

Thinking of the main staple of the dish—potatoes, the starchy vegetable that provides sustenance for people around the globe. The onion, the layers of sorrow and joy—a base for this dish served during the holidays. The oil, symbolic of hope and perseverance. All of these elements come together to form this delicious oval pancake permeating with possibilities. I wonder about future possibilities as I flip the latkes.

—Nikki Markman, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California

The egg is a treasure. It is a fragile heart of gold that once broken, flows over the blemishless surface of the egg white in dandelion colored streams, like ribbon unraveling from its spool.

—Kaylin Ku, West Windsor-Plainsboro High School South, Princeton Junction, New Jersey

If I were to bring one food to a potluck to create social change by addressing anti-Semitism, I would bring gefilte fish because it is different from other fish, just like the Jews are different from other people. It looks more like a matzo ball than fish, smells extraordinarily fishy, and tastes like sweet brine with the consistency of a crab cake.

—Noah Glassman, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

I would not only be serving them something to digest, I would serve them a one-of-a-kind taste of the past, a taste of fear that is felt in the souls of those whose home and land were taken away, a taste of ancestral power that still lives upon us, and a taste of the voices that want to be heard and that want the suffering of the Natives to end.

—Citlalic Anima Guevara, Wichita North High School, Wichita, Kansas

It’s the one thing that your parents make sure you have because they didn’t. Food is what your mother gives you as she lies, telling you she already ate. It’s something not everybody is fortunate to have and it’s also what we throw away without hesitation. Food is a blessing to me, but what is it to you?

—Mohamed Omar, Kirkwood High School, Kirkwood, Missouri

Filleted and fried humphead wrasse, mangrove crab with coconut milk, pounded taro, a whole roast pig, and caramelized nuts—cuisines that will not be simplified to just “food.” Because what we eat is the diligence and pride of our people—a culture that has survived and continues to thrive.

—Mayumi Remengesau, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California

Some people automatically think I’m kosher or ask me to say prayers in Hebrew. However, guess what? I don’t know many prayers and I eat bacon.

—Hannah Reing, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, The Bronx, New York

Everything was placed before me. Rolling up my sleeves I started cracking eggs, mixing flour, and sampling some chocolate chips, because you can never be too sure. Three separate bowls. All different sizes. Carefully, I tipped the smallest, and the medium-sized bowls into the biggest. Next, I plugged in my hand-held mixer and flicked on the switch. The beaters whirl to life. I lowered it into the bowl and witnessed the creation of something magnificent. Cookie dough.

—Cassandra Amaya, Owen Goodnight Middle School, San Marcos, Texas

Biscuits and bisexuality are both things that are in my life…My grandmother’s biscuits are the best: the good old classic Southern biscuits, crunchy on the outside, fluffy on the inside. Except it is mostly Southern people who don’t accept me.

—Jaden Huckaby, Arbor Montessori, Decatur, Georgia

We zest the bright yellow lemons and the peels of flavor fall lightly into the batter. To make frosting, we keep adding more and more powdered sugar until it looks like fluffy clouds with raspberry seed rain.

—Jane Minus, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

Tamales for my grandma, I can still remember her skillfully spreading the perfect layer of masa on every corn husk, looking at me pitifully as my young hands fumbled with the corn wrapper, always too thick or too thin.

—Brenna Eliaz, San Marcos High School, San Marcos, Texas

Just like fry bread, MRE’s (Meals Ready to Eat) remind New Orleanians and others affected by disasters of the devastation throughout our city and the little amount of help we got afterward.

—Madeline Johnson, Spring Hill College, Mobile, Alabama

I would bring cream corn and buckeyes and have a big debate on whether marijuana should be illegal or not.

—Lillian Martinez, Miller Middle School, San Marcos, Texas

We would finish the meal off with a delicious apple strudel, topped with schlag, schlag, schlag, more schlag, and a cherry, and finally…more schlag (in case you were wondering, schlag is like whipped cream, but 10 times better because it is heavier and sweeter).

—Morgan Sheehan, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

Clever Titles

This year we decided to do something different. We were so impressed by the number of catchy titles that we decided to feature some of our favorites.

“Eat Like a Baby: Why Shame Has No Place at a Baby’s Dinner Plate”

—Tate Miller, Wichita North High School, Wichita, Kansas

“The Cheese in Between”

—Jedd Horowitz, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

“Harvey, Michael, Florence or Katrina? Invite Them All Because Now We Are Prepared”

—Molly Mendoza, Spring Hill College, Mobile, Alabama

“Neglecting Our Children: From Broccoli to Bullets”

—Kylie Rollings, Kirkwood High School, Kirkwood, Missouri

“The Lasagna of Life”

—Max Williams, Wichita North High School, Wichita, Kansas

“Yum, Yum, Carbon Dioxide In Our Lungs”

—Melanie Eickmeyer, Kirkwood High School, Kirkwood, Missouri

“My Potluck, My Choice”

—Francesca Grossberg, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

“Trumping with Tacos”

—Maya Goncalves, Lincoln Middle School, Ypsilanti, Michigan

“Quiche and Climate Change”

—Bernie Waldman, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

“Biscuits and Bisexuality”

“W(health)”

—Miles Oshan, San Marcos High School, San Marcos, Texas

“Bubula, Come Eat!”

—Jordan Fienberg, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

Get Stories of Solutions to Share with Your Classroom

Teachers save 50% on YES! Magazine.

Inspiration in Your Inbox

Get the free daily newsletter from YES! Magazine: Stories of people creating a better world to inspire you and your students.

OUTSIDE FESTIVAL JUNE 1-2

Don't miss Thundercat + Fleet Foxes, adventure films, experiences, and more!

GET TICKETS

What Food and Nutrition Will Look Like in 50 Years

We wanted to know: in the face of climate change and innovation, how will food fare? Top food experts weigh in.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

Welcome to dinnertime in the year 2070. Your food—perfectly tailored to your genome—is prepared by a robot chef . Your kitchen is full of healthy fats and regionally sourced food, and you haven’t counted calories in decades. You can credit your longer life span to the doctor-prescribed medication in your cabinet: produce. And the majority of your protein comes from insects.

How we’ll eat 50 years from now is uncertain. But according to leading experts in food policy, agriculture, and nutrition, factors like climate change, individual and societal health trends, and technology will all change what’s on our plates. We asked five leaders in the food industry about what to expect in the coming decades. From the unsurprising to the Jetsons -esque, here are some of their most compelling predictions.

Dinner Will Be Served Hot and Fresh Out of the Lab

Expert: dr. stuart farrimond.

Physician, food-science writer, and BBC radio host

According to Farrimond , the future of nutrition will have two separate camps: “We’re going to have one group of people who want ‘the fix,’” he says. “They will want processed food that has all the answers.” You’ll find this group of people taking DNA tests to get personalized meal plans , popping exercise pills marketed as “advanced supplements,” biohacking , and eating food that’s designed for them based on their genetics.

“And then you’ve got another group of people who shun all of that,” Farrimond says. “They want natural, uncontaminated, organic, back-to-nature food.” This group will be conscious of the environment, eating food technologically altered for their health and the planet’s. According to Farrimond, this population will abandon the carbon-intensive meat industry and opt for powdered blends of meat’s high-protein, low-impact cheap alternative: insects. They’ll also cook with sugar enhanced by nanotechnology to be sweeter (making it possible to use less) and 3-D “print” ingredients into intricate gastronomic masterpieces.

“You’ll have the most spectacular dinner parties,” Farrimond says.

We ’ ll Finally Embrace Fat

Expert: elyse kopecky.

Nutrition coach and New York Times bestselling author

Many experts already think it’s time to kill the calorie , and Kopckey is one of them. The author, who cowrote both Run Fast. Eat Slow. cookbooks with four-time Olympian Shalane Flanagan , thinks that the future is simpler than wacky gene blends and technology. Instead, she believes that all athletes will embrace healthy fats and eliminate restrictive eating from the mix.

“Butter is a health food,” says Kopecky. “It’s more nutrient dense than kale.” She predicts that in a decade or two, the athlete’s kitchen will be filled with calorically dense unrefined oils, butter, and other flavor-packed ingredients. “When you cook with fat, it tastes better,” she says.

As a young runner, Kopecky experienced amenorrhea and stress fractures , and looking back, she blames her diet. “Low-fat everything and all frozen, prepackaged meals,” she says. When she changed her eating habits to include ample calories, particularly from fat, her symptoms disappeared. Kopecky hopes that athletes of the future won’t have to wait until their bodies break down to change their diets.

Don’t Count on California

Expert: tom philpott.

Food and agriculture correspondent for Mother Jones

California is the number-one state in the country for agricultural production today, boasting a long list of exports including almonds, pistachios, strawberries, avocados, dairy, walnuts, and more. However, Philpott says that consumers of the future will have to count the state, and its crops, out. California, along with the rest of America, is projected to experience some hefty damage at the hands of climate change, including more wildfires like the one in Paradise , severe drought, and the looming possibility of an overdue catastrophic earthquake . That’s bad news for a host of reasons, but, according to Philpott, it will hit the food-supply chain especially hard.

“We’re going to have to engage in what I call decalifornization,” he says. (In other words, avocado toast will no longer be the brunch food of the moment.)

Sustainability Will Be Law

Expert: tim griffin.

Director of the agriculture, food, and environment program at Tufts University

Griffin, an adviser to the most recent U.S. Dietary Guidelines , thinks sustainability will color the future of food at every stage of production, shopping, and preparation. Consumers of tomorrow will be hyperaware of how food gets to their plate, he says. “They’ll need to ask not just, ‘What am I going to eat for dinner?’ but ‘What am I going to eat for dinner, and how will that impact X, Y, and Z?’”

Griffin says that everyday shoppers have the most sway in what happens to our food system, and she believes that a greater awareness of how our eating habits impact the planet will, eventually, influence policy.

“Twenty-five to 40 percent of food grown on [American] farms is wasted,” he says. “But in the past, things have changed because of consumers. Social outcomes are important.” People are taking waste more seriously, he says, and if that continues, sustainability will become part of our new guidelines. He points out that trend-based changes to the guidelines have happened before, but slowly; it took until 2010 for physical activity to be written in as an essential balance to our diets.

Your New Medicine Cabinet Is the Fridge

Expert: monica mills.

Executive director of Food Policy Action

Americans today have more prescriptions than ever, but they can’t afford the medication they need. Similarly, fresh fruits and veggies are necessary for your body to function properly—they can even directly affect your brain structure—but for some people, the high cost of produce means choosing between dinner and rent . “Food is medicine,” says Mills, whose organization in Washington, D.C., lobbies for improved access to food, farmers’ rights, and reducing the environmental impact of food production. Doctors and governments of the future, according to Mills, will understand that.

Farmers are currently federally incentivized to grow mass crops like corn and soy, but no commodities are given to fruit and vegetable growers. That makes corn-based food—soda, fast-food burgers, nutrition bars—cheaper, says Mills, and it gives low-income individuals less access to healthy, fresh foods.

The future food market, according to Mills, will be saturated with programs like Double Up Bucks , which helps low-income people buy healthy, local food, and Wholesome Wave , which allows doctors to prescribe produce as medicine. Mills acknowledges that the government’s stance on food production has historically been slow to change. “But 100 years from now,” she says, “I hope it will look very, very different.”

- Climate Change

- Environment

When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small commission. We do not accept money for editorial gear reviews. Read more about our policy.

Popular on Outside Online

Enjoy coverage of racing, history, food, culture, travel, and tech with access to unlimited digital content from Outside Network's iconic brands.

Healthy Living

- Clean Eating

- Vegetarian Times

- Yoga Journal

- Fly Fishing Film Tour

- National Park Trips

- Warren Miller

- Fastest Known Time

- Trail Runner

- Women's Running

- Bicycle Retailer & Industry News

- FinisherPix

- Outside Events Cycling Series

- Outside Shop

© 2024 Outside Interactive, Inc

- Subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine

- Previous Issues

- Future tech

- Everyday science

- Planet Earth

- Newsletters

The future of food: what we’ll eat in 2028

We’ve all heard that the future menu may involve less meat and dairy. But don’t worry, we could have customised diets, outlandish vegetables, robot chefs and guilt-free gorging to look forward to instead. And we reckon that makes up for missing out on the odd sausage

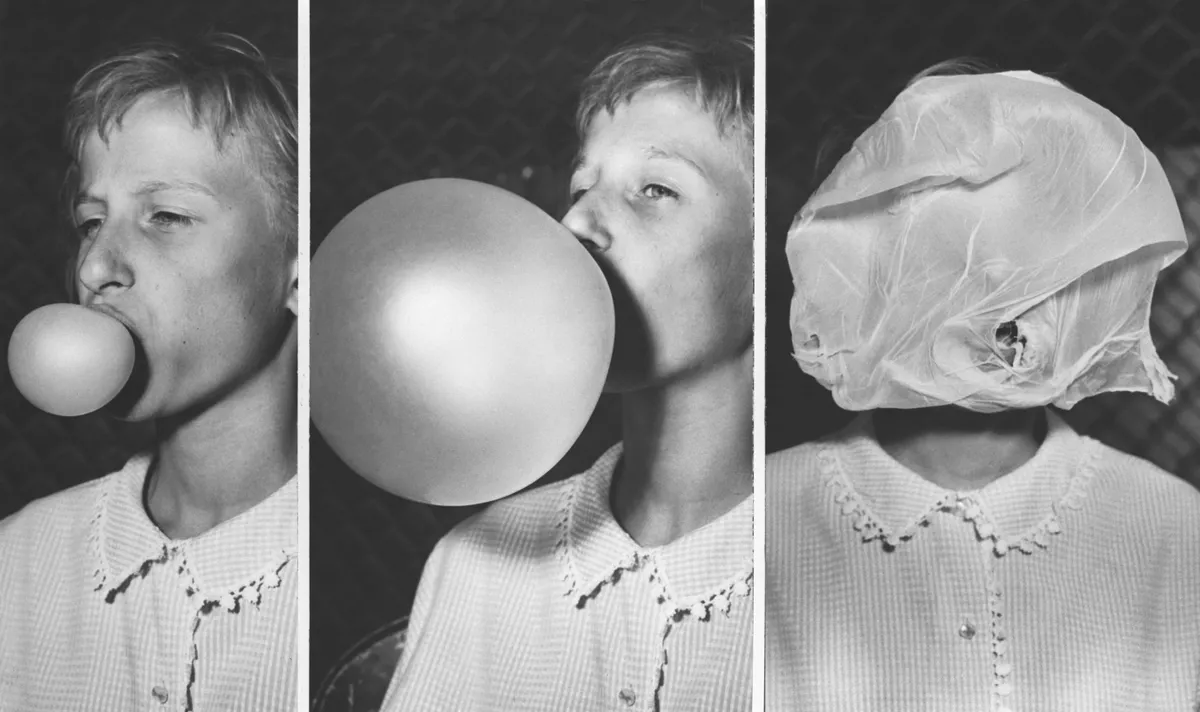

Dr Stuart Farrimond

Before 1928, no one had tasted bubblegum. In the late 1930s, frozen cream desserts threw off their reputation for being as hard as rock with the US invention of soft-serve ice cream (often called Mr Whippy in the UK). Popping candy introduced children’s mouths to a bizarre effervescence 20 years later. And in the late 1990s, Red Bull showcased a strange medicinal flavour that’s since become synonymous with energy drinks. The foods we eat are always evolving and new tastes are being created. By 2028, you can expect to be tucking into foods unlike anything you’ve experienced before.

In 2028 food will be tailored to your genome

Today, we know that healthy eating is important to keep our bodies in tip-top condition. This link between diet and health was first ‘proved’ in the mid-1800s by Scottish naval surgeon Dr Joseph Lind, who is credited with running one of the earliest ever clinical controlled trials. His study demonstrated that citrus fruits could protect sailors from scurvy. The watershed finding set the stage for lemons and limes to be issued as standard in sailors’ rations, and showed how healthy eating can save untold numbers of lives.

These days, science may have dissected almost every element of our diet, but many of us still feel at sea. Even when sticking to official advice, healthy foods that seem to energise one person can cause another to feel fatigued and bloated. In 2015, a team of scientists from Israel tracked blood sugar levels in the blood of 800 people over several days, making the surprising discovery that individuals’ biological response to identical foods varied wildly. Some people had a blood glucose ‘spike’ after eating sugaryice cream, while others’ glucose levelsonly increased with starchy rice – a finding at odds with conventional wisdom.

In the next 10 years, the emerging field of ‘personalised nutrition’ will offer healthy eating guidance tailored to the individual

Our bodies’ idiosyncratic handling of nutrients seems to be down to our genetics, the microbes in our gut, and variations in our organs’ internal physiology. Clinical trials like those pioneered by Lind have given us general dietary guidelines, but nutrition research tends to assume all humans are the same, and so can miss the nuances and specific needs ofthe individual.

In the next 10 years, the emerging field of ‘personalised nutrition’ will use genetic tests to fill in those gaps to offer healthy eating guidance tailored to the individual. Some companies, so-called ‘nutrigenetics services’, already test your DNA and offer dietary advice – but the advice can be hit-and-miss. By 2028, we will understand much more about our genetics. Dr Jeffrey Blumberg, a professor of nutrition science and policy at Tufts University in Massachusetts, is one of the most outspoken advocates of this new science. He insists that DNA testing will unlock personalised nutrition. “I’ll be able to tell you what kinds of fruits, what kinds of vegetables and what kinds of wholegrains you should be choosing, or exactly how often,” he says.

Sadly, personalised nutrition looks set to make cooking meals for the whole family just that little bit more taxing.

In 2028 food will be engineered to be more nutritious

‘Natural’ is a buzz term food marketers love to use, but barely any of our current produce ever existed in the natural world. The fruit and vegetables that we enjoy today have been selectively bred over thousands of years, often mutated out of all recognition from the original wild crop. Carrots weren’t originally orange, they were scrawny and white; peaches once resembled cherries and tasted salty; watermelons were small, round, hard and bitter; aubergines used to look like white eggs.

- Five things you probably didn’t know about processed food

- The Angry Chef on debunking food myths

But the selective breeding for bulky and tasty traits, combined with intensive farming practices, has sometimes come at a nutritional cost. Protein, calcium, phosphorus, iron, riboflavin (vitamin B2) and vitamin C have all waned in fruit and vegetables over the past century, with today’s vegetables having about two-thirds of the minerals they used to have.

By 2028, genetics and biomolecular science should have redressed the balance, so that DNA from one organism is inserted into another, eliminating the need to undertake generations of selective breeding to acquire desirable traits.

Just last year, researchers from Australia showcased a banana with high levels of provitamin A, an important nutrient not normally present in the fruit. To create this fruit, the researchers snipped out genes from a specific type of Papua New Guinean banana that’s naturally high in provitamin A, then inserted them into the common banana variety.

More controversially, DNA can be transplanted from completely different organisms to create varieties that would never occur with selective breeding. Corn has been successfully given a boost of methionine – a key nutrient missing in the cereal – by splicing in DNA from a bacterium. Even the genetic code itself can be edited to develop ‘superpowers’: in 2008, for example, researchers created modified carrots that increase the body’s absorption of calcium.

There have been hundreds of examples of these incredible botanical creations: potatoes, corn and rice containing more protein; linseed having more omega-3 and omega-6 fats; tomatoes containing antioxidants originally found in snapdragons; and lettuce that carries iron in a form that’s easily digestible by the body.

Over the next ten years, the number of nutritionally enhanced crops will probably explode. Precise DNA-editing technology – namely a technique called CRISPR-Cas9 – now allows alteration of plant genetic code with unprecedented accuracy. Get ready for tasty apples with all the goodness of their bitter forebears, peanuts that don’t trigger allergies, and lentils that have a protein content equivalent to meat. It will be like creating the orange carrot all over again!

In 2028 food will be different from anything you have tasted before

New flavours arrive unpredictably as food manufacturers create new products. Silicon Valley – well known for attracting the brightest minds – is becoming the global hub for food innovation. A start-up currently making waves is Impossible Foods, which has created a meat-free burger that sizzles in the pan, tastes like meat and ‘bleeds’. Designed to be sustainable and environmentally friendly, the patties are made with wheat protein, coconut oil, potato protein, and flavourings. The secret ingredient is heme – the oxygen-carrying molecule that makes both meat and blood red – and seems to give meat much of its flavour. The heme that Impossible Foods uses has been extracted from plants and produced using fermentation. It’s a growth industry, with competitors such as Beyond Meat and Moving Mountains cooking up similar burgers, and plans are afoot for plant-based steaks andchicken. It doesn’t stop there, however: other start-ups are pioneering animal-free milk and egg whites. Expect to get usedto the new tastes of meat-free meat and dairy-free dairy.

It’s now been more than a decade since chef Heston Blumenthal first served his famous ‘sound of the seas’ dish, for which diners listened to a recording of breaking waves to heighten the salty flavours of seafood. It is well established that all senses inform the flavour of food: desserts taste creamier if served in a round bowl rather than on a square plate; background hissing or humming makes food taste less sweet; and crisps feel softer if we can’t hear them crunching in the mouth. The emerging field of ‘neurogastronomy’ brings together our latest understanding of neurology and food science and will be a big player in our 2028 dining.

Today, you might hear James Blunt crooning in your favourite eatery, but in the restaurant of 2028, there may be aromatic mists, subtle sound effects and controlled lighting, all optimised to make your steak and chips taste better than you thought possible. At home, augmented reality headsets that superimpose digital imagery on the real world could offer a tranquil seascape for a fish dish, or the wilds of Texas for barbecued ribs.

Unusual processed foods will make a splash in the years to come, including novelties like edible spray paint, algae protein snack bars, beer made with wastewater, and even lollipops designed to cure hiccups. We don’t know exactly what will be on tomorrow’s supermarket shelves (if supermarkets still exist, that is) due to the secretive nature of the multinational food corporations. But we do know that ice cream and chocolate that don’t melt in warm weather are definitely under development. Nanotechnology is going to feature: researchers are currently devising nanoparticles that give delayed bursts of flavour in the mouth, and earlier this year, a team of chemists created tiny magnetic particles that bind to and remove off-tasting flavour compounds in red wine while preserving its full aroma.

- Five recipe books to tantalise your scientific senses

- The Big Mac and the bee

Cookbooks in 2028 will have some weird recipes. By analysing foods for their flavour compounds – aroma-carrying substances that convey flavour – ingredients can be paired to create novel experiences. In 2016, researchers from the International Society of Neurogastronomy demonstrated a menu with hitherto untried ingredient blends, designed to be flavourful for people who had lost their sense of taste and smell through chemotherapy.A lip-smacking highlight was: clementine upside-down cake with a dab of basil and pistachio pesto, crowned with a scoop of olive oil gelato.

Perhaps the most outlandish proposal to enhance the eating experience is to ‘hack’ the brain. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is designing implantable ‘neural interfaces’ that aim to boost human senses by transmitting high-resolution audiovisual information, and potentially smells and tastes, directly to the brain.

In 2028 food will be guilt free

We just keep getting heavier. Today around 40 per cent of all adults are overweight or obese and every single nation on Earth is getting fatter. Obesity-related diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, are soaring on a trajectory that will cripple many health services. Most troublingly, there have been no success stories in the past 33 years – not one country has been able to halt the growth of the bulge. Processed, calorie-dense foods continue to become more widely available worldwide and, short of an international catastrophe like a global famine or mass outbreak of war, turning the tide is going to take some truly innovative thinking.

A short-term solution is to re-engineer calorific ‘junk’ food to have less fat, sugar, salt and fewer calories, while still giving the same satisfaction. There are artificial sweeteners, but they can haveunpleasant side effects and can’t be cooked as sugar can. Low-calorie sugar substitutes, such as sugar-alcohols like sorbitol, taste like the real thing but cause flatulence and diarrhoea if eaten excessively. But food technologists have managed to coat inert mineral particles with sugar, increasing the surface area that contacts the tongue, so that less sugar can be used to provide the same sweetness.

In the longer term, fine-tuning our biology could allow us to eat without guilt. Few people realise that our appetite is precisely regulated. Overeat on a Monday, and you usually eat less on Tuesday and Wednesday. Our hunger is usually set to a level almost identical to the number of calories we need. Unfortunately, the hunger ‘thermostat’ is set a little too high, by an average of about 0.4 per cent (or 11 calories a day). Left to our own devices, we will each tend to eat an extra peanut’s worth of calories each day. That doesn’t sound like much, but it adds up to nearly half a kilogramme weight gain each year. Our unfortunate tendency to develop ‘middle-aged spread’ has presumably evolved as an insurance against the next famine.

The hunt is on to nudge the appetite set point down by 11 calories or more. Many hormones swirl around the blood to tell us when to eat and when to stop. One hormone, CCK, is released by the gut when food enters it, making us feel full. Another hormone, leptin, is released by body fat and apparently tells the body when our fat stores are adequate. It’s a complex picture and attempts at manipulating individual hormone levels have been unsuccessful. Everyone is hoping that we will soon untangle the web of brain-hormone messages and managed to devise supplements, foods or medicine that can make a tiny tweak to the dial.

In 2028 food will be more creative

Kitchen creativity has few limits. From Weetabix ice cream to liquid nitrogen cocktail balls, exciting dishes are made by chefs who love to surprise, but few such culinary masterpieces make it into the home, owing to a reliance on specialist equipment and professional skills. Expect that to change as equipment becomes more affordable. Even today, the sous-vide water bath that was once reserved for fine dining restaurants can be purchased for less than a set of pans. In the coming years, the spiraliser will have been eclipsed by a handheld spherificator or foam-making espuma gun. For the ambitious home cook, getting creative is going to be a lot more fun.

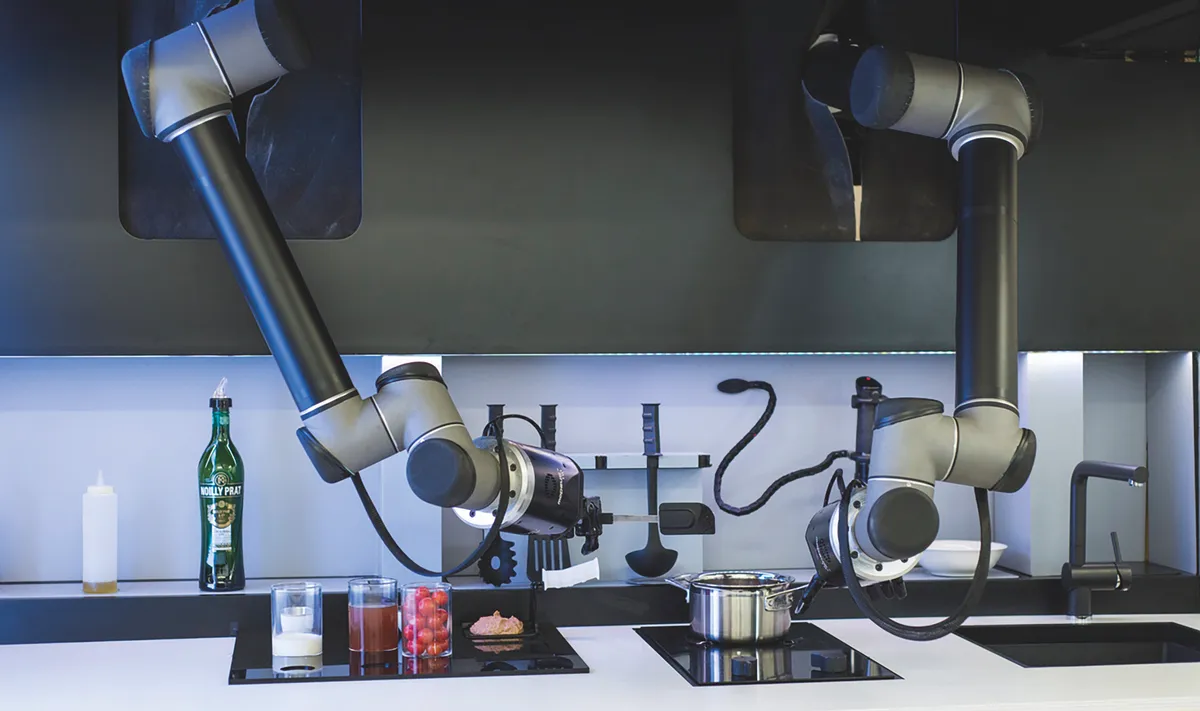

When skills are lacking, a robotic sous-chef may lend a helping hand. Imagine being able to send a message your Robo-Chef while on the commute home to prepare a recipe of your choice. Within moments, android arms will be gathering ingredients from the fridge, julienning the turnips and deboning the chicken.

It’s not completely pie-in-the-sky, either. UK-based Moley Robotics has already developed a ‘robotic kitchen’, set for consumer release this year. Consisting of two articulated arms, cooking hobs, oven and touchscreen interface, this is a robot that can chop, whisk, stir, pour and clean. It’s no clumsy Dalek either: each hand has 20 motors, 24 joints and 129 sensors to mimic the movements of human hands. Skills are ‘learnt’ by replicating the movements of chefs and other cooks, and their recipes can be selected via an iTunes-like recipe catalogue. The speed and dexterity of the robotic kitchen will have foodies salivating at the possibilities. But with the first devices expected to cost around £10,000 each, it might be worth holding out until they throw in a dishwasher.

Elsewhere, 3D-printed food offers endless opportunities for creating intricate dishes that are impossible to create by human hands alone. Everything from toys to aeroplane parts, from prosthetics to clothing – even whole houses – are already being made with 3D printers. And the food frontier has been crossed. Custom sweets can be designed and made using sugar-rich ‘ink’ to construct anything from interlocking candy cubes and chewable animal shapes, to lollipops in the shape of Queen Elizabeth’s head.

Until recently, 3D printing has been sugar-based, but technology is emerging that reliably prints savoury and fresh ingredients. Natural Machines has developed one such kitchen appliance that can be loaded with multiple ingredient capsules to create and cook all manner of weird and wonderful foods. These include: crackers shaped like coral, hexagonal crisps, heart-shaped pizzas and hollow croutons that dissolve in sauce. With the promise of cutting waste by repurposing ‘ugly’ food and offcuts for food capsules, Natural Machines has the potential to drastically reduce packaging and transport costs. Not yet sold on the idea? Imagine wowing your nearest and dearest by serving upthe ultimate romantic meal finished off with a personalised chocolate torte, where an invisible series of grooves in the chocolate surface plays their favourite song when placed in a special ‘record player’. Delicious!

This is an extract from issue 322 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

Follow Science Focus on Twitter , Facebook , Instagram and Flipboard

Share this article

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Code of conduct

- Magazine subscriptions

- Manage preferences

- Ways to Give

- Contact an Expert

- Explore WRI Perspectives

Filter Your Site Experience by Topic

Applying the filters below will filter all articles, data, insights and projects by the topic area you select.

- All Topics Remove filter

- Climate filter site by Climate

- Cities filter site by Cities

- Energy filter site by Energy

- Food filter site by Food

- Forests filter site by Forests

- Freshwater filter site by Freshwater

- Ocean filter site by Ocean

- Business filter site by Business

- Economics filter site by Economics

- Finance filter site by Finance

- Equity & Governance filter site by Equity & Governance

Search WRI.org

Not sure where to find something? Search all of the site's content.

Creating a Sustainable Food Future

A Menu of Solutions to Feed Nearly 10 Billion People by 2050

- Jillian Holzer

- Shifting Diets for a Sustainable Food Future: Creating a Sustainable Food Future, Installment Eleven

- Ensuring Crop Expansion is Limited to Lands with Low Environmental Opportunity Costs

- Avoiding Bioenergy Competition for Food Crops and Land

- Wetting and Drying: Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Saving Water from Rice Production

- Crop Breeding: Renewing the Global Commitment

- Indicators of Sustainable Agriculture: A Scoping Analysis

- Improving Productivity and Environmental Performance of Aquaculture

- Creating a Sustainable Food Future: Interim Findings

- Improving Land and Water Management

- Achieving Replacement Level Fertility

By 2050, nearly 10 billion people will live on the planet. Can we produce enough food sustainably? World Resources Report: Creating a Sustainable Food Future shows that it is possible – but there is no silver bullet. This report offers a five-course menu of solutions to ensure we can feed everyone without increasing emissions, fueling deforestation or exacerbating poverty. Intensive research and modeling examining the nexus of the food system, economic development, and the environment show why each of the 22 items on the menu is important and quantifies how far each solution can get us.

WRI produced the report in partnership with the World Bank, UN Environment, UN Development Programme, and the French agricultural research agencies CIRAD and INRA.

World Resources Report

The World Resources Report is World Resources Institute's flagship publication.

Coolfood helps people and organizations reduce the climate impact of their food through shifting toward more plant-rich diets.

Better Buying Lab

Cooking up cutting-edge strategies that enable consumers to buy and consume more sustainable foods.

Food Loss & Waste Protocol

Addressing the challenges of quantifying food loss and waste.

Land & Carbon Lab

This initiative connects those at the vanguard of land monitoring with those at the frontlines of land use decisions.

Primary Contacts

Communications Manager, Food

How You Can Help

WRI relies on the generosity of donors like you to turn research into action. You can support our work by making a gift today or exploring other ways to give.

Stay Informed

World Resources Institute 10 G Street NE Suite 800 Washington DC 20002 +1 (202) 729-7600

© 2024 World Resources Institute

Envision a world where everyone can enjoy clean air, walkable cities, vibrant landscapes, nutritious food and affordable energy.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 19 August 2020

The future of food from the sea

- Christopher Costello ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9646-7806 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Ling Cao 3 na1 ,

- Stefan Gelcich ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5976-9311 4 , 5 na1 ,

- Miguel Á. Cisneros-Mata ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5525-5498 6 ,

- Christopher M. Free 1 , 2 ,

- Halley E. Froehlich 7 , 8 ,

- Christopher D. Golden ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0358-4625 9 , 10 ,

- Gakushi Ishimura 11 , 12 ,

- Jason Maier 1 ,

- Ilan Macadam-Somer 1 , 2 ,

- Tracey Mangin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6111-0914 1 , 2 ,

- Michael C. Melnychuk 13 ,

- Masanori Miyahara 14 ,

- Carryn L. de Moor 15 ,

- Rosamond Naylor 16 , 17 ,

- Linda Nøstbakken 18 ,

- Elena Ojea 19 ,

- Erin O’Reilly 1 , 2 ,

- Ana M. Parma 20 ,

- Andrew J. Plantinga 1 , 2 ,

- Shakuntala H. Thilsted 21 &

- Jane Lubchenco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3540-5879 22

Nature volume 588 , pages 95–100 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

104k Accesses

395 Citations

921 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Ecosystem services

- Environmental sciences

Matters Arising to this article was published on 09 March 2022

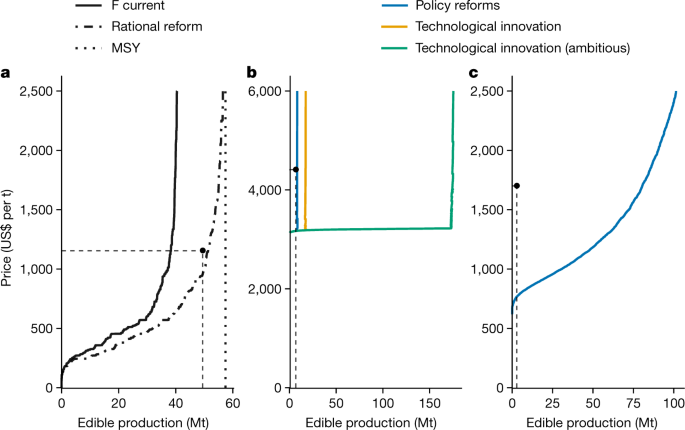

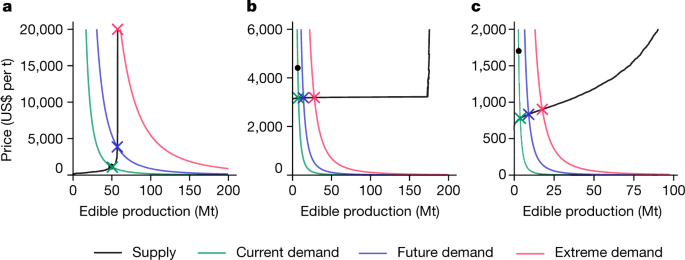

Global food demand is rising, and serious questions remain about whether supply can increase sustainably 1 . Land-based expansion is possible but may exacerbate climate change and biodiversity loss, and compromise the delivery of other ecosystem services 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . As food from the sea represents only 17% of the current production of edible meat, we ask how much food we can expect the ocean to sustainably produce by 2050. Here we examine the main food-producing sectors in the ocean—wild fisheries, finfish mariculture and bivalve mariculture—to estimate ‘sustainable supply curves’ that account for ecological, economic, regulatory and technological constraints. We overlay these supply curves with demand scenarios to estimate future seafood production. We find that under our estimated demand shifts and supply scenarios (which account for policy reform and technology improvements), edible food from the sea could increase by 21–44 million tonnes by 2050, a 36–74% increase compared to current yields. This represents 12–25% of the estimated increase in all meat needed to feed 9.8 billion people by 2050. Increases in all three sectors are likely, but are most pronounced for mariculture. Whether these production potentials are realized sustainably will depend on factors such as policy reforms, technological innovation and the extent of future shifts in demand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Expanding ocean food production under climate change

Reducing global land-use pressures with seaweed farming

Farming fish in the sea will not nourish the world

Human population growth, rising incomes and preference shifts will considerably increase global demand for nutritious food in the coming decades. Malnutrition and hunger still plague many countries 1 , 7 , and projections of population and income by 2050 suggest a future need for more than 500 megatonnes (Mt) of meat per year for human consumption (Supplementary Information section 1.1.6 ). Scaling up the production of land-derived food crops is challenging, because of declining yield rates and competition for scarce land and water resources 2 . Land-derived seafood (freshwater aquaculture and inland capture fisheries; we use seafood to denote any aquatic food resource, and food from the sea for marine resources specifically) has an important role in food security and global supply, but its expansion is also constrained. Similar to other land-based production, the expansion of land-based aquaculture has resulted in substantial environmental externalities that affect water, soil, biodiversity and climate, and which compromise the ability of the environment to produce food 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . Despite the importance of terrestrial aquaculture in seafood production (Supplementary Fig. 3 ), many countries—notably China, the largest inland-aquaculture producer—have restricted the use of land and public waters for this purpose, which constrains expansion 8 . Although inland capture fisheries are important for food security, their contribution to total global seafood production is limited (Supplementary Table 1 ) and expansion is hampered by ecosystem constraints. Thus, to meet future needs (and recognizing that land-based sources of fish and other foods are also part of the solution), we ask whether the sustainable production of food from the sea has an important role in future supply.

Food from the sea is produced from wild fisheries and species farmed in the ocean (mariculture), and currently accounts for 17% of the global production of edible meat 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 (Supplementary Information section 1.1 , Supplementary Tables 1 – 3 ). In addition to protein, food from the sea contains bioavailable micronutrients and essential fatty acids that are not easily found in land-based foods, and is thus uniquely poised to contribute to global food and nutrition security 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 .

Widely publicized reports about climate change, overfishing, pollution and unsustainable mariculture give the impression that sustainably increasing the supply of food from the sea is impossible. On the other hand, unsustainable practices, regulatory barriers, perverse incentives and other constraints may be limiting seafood production, and shifts in policies and practices could support both food provisioning and conservation goals 17 , 18 . In this study, we investigate the potential of expanding the economically and environmentally sustainable production of food from the sea for meeting global food demand in 2050. We do so by estimating the extent to which food from the sea could plausibly increase under a range of scenarios, including demand scenarios under which land-based fish act as market substitutes.

The future contribution of food from the sea to global food supply will depend on a range of ecological, economic, policy and technological factors. Estimates based solely on ecological capacity are useful, but do not capture the responses of producers to incentives and do not account for changes in demand, input costs or technology 19 , 20 . To account for these realities, we construct global supply curves of food from the sea that explicitly account for economic feasibility and feed constraints. We first derive the conceptual pathways through which food could be increased in wild fisheries and in mariculture sectors. We then empirically derive the magnitudes of these pathways to estimate the sustainable supply of food from each seafood sector at any given price 21 . Finally, we match these supply curves with future demand scenarios to estimate the likely future production of sustainable seafood at the global level.

Sustainably increasing food from the sea

We describe four main pathways by which food supply from the ocean could increase: (1) improving the management of wild fisheries; (2) implementing policy reforms of mariculture; (3) advancing feed technologies for fed mariculture; and (4) shifting demand, which affects the quantity supplied from all three production sectors.

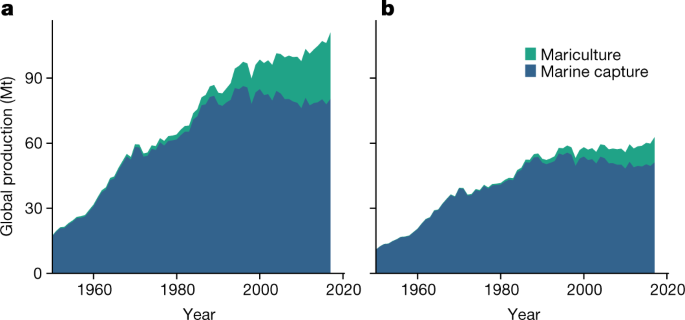

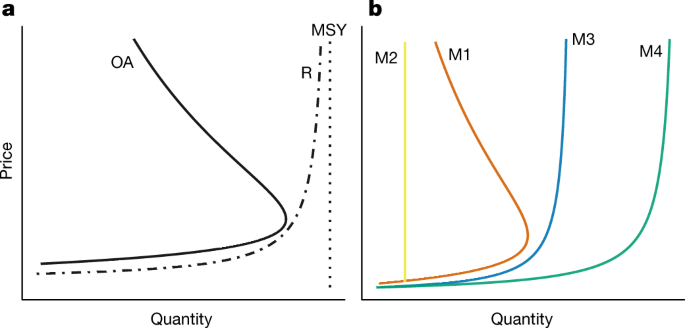

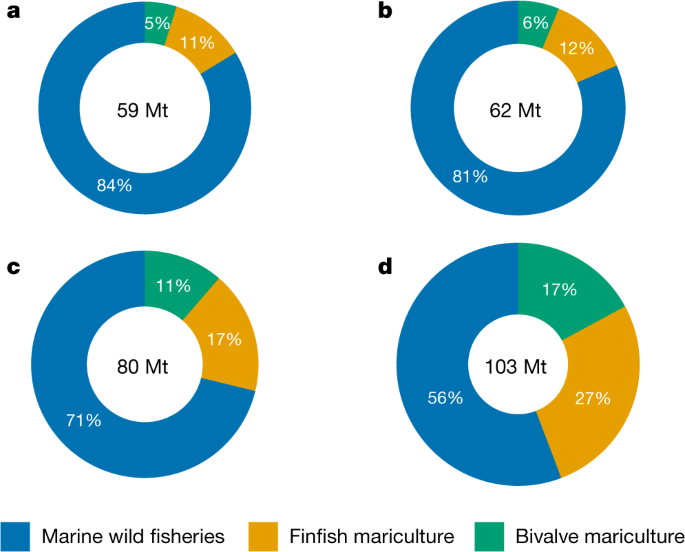

Although mariculture production has grown steadily over the past 60 years (Fig. 1 ) and provides an important contribution to food security 22 , the vast majority (over 80%) of edible meat from the sea comes from wild fisheries 9 (Fig. 1b ). Over the past 30 years, supply from this wild food source has stabilized globally despite growing demand worldwide, which has raised concerns about our ability to sustainably increase production. Of nearly 400 fish stocks around the world that have been monitored since the 1970s by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), approximately one third are currently not fished within sustainable limits 1 . Indeed, overfishing occurs often in poorly managed (‘open access’) fisheries. This is disproportionately true in regions with food and nutrition security concerns 1 . In open-access fisheries, fishing pressure increases as the price rises: this can result in a ‘backward-bending’ supply curve 23 , 24 (the OA curve in Fig. 2a ), in which higher prices result in the depletion of fish stocks and reduced productivity—and thus reduced equilibrium food provision.

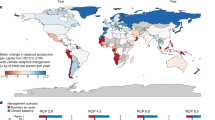

Data are from ref. 9 . a , b , Harvests (live-weight production) ( a ) are converted to food equivalents (edible production) 10 ( b ). In b , there is also an assumption that 18% of the annual landings of marine wild fisheries are directed towards non-food purposes 47 .

a , Wild fisheries. Curves represent poorly managed (open access) fisheries (OA); management reform for all fisheries (MSY); and economically rational management reform (R). b , Mariculture. Curves represent weak regulations that allow for ecologically unsustainable production (M1); overly restrictive policies (M2); policies that allow for sustainable expansion (M3); and a reduced dependence on limited feed ingredients for fed-mariculture production (M4).

Fishery management allows overexploited stocks to rebuild, which can increase long-term food production from wild fisheries 25 , 26 . We present two hypothetical pathways by which wild fisheries could adopt improved management (Fig. 2a ). First, independent of economic conditions, governments can impose reforms in fishery management. The resulting production in 2050 from this pathway—assuming that fisheries are managed for maximum sustainable yield (MSY)—is represented by the MSY curve in Fig. 2a , and is independent of price. The second pathway explicitly recognizes that wild fisheries are expensive to monitor (for example, via stock assessments) and manage (for example, via quotas)—management reforms are adopted only by fisheries for which future profits outweigh the associated costs of improved management. When management entities respond to economic incentives, the number of fisheries for which the benefits of improved management outweigh the costs increases as demand (and thus price) increases. This economically rational management endogenously determines which fisheries are well-managed, and thus how much food production they deliver, resulting in supply curve designated R in Fig. 2a .

Although the production of wild fisheries is approaching its ecological limits, current mariculture production is far below its ecological limits and could be increased through policy reforms, technological advancements and increased demand 19 , 27 . We present explanations for why food production from mariculture is currently limited, and describe how the relaxation of these constraints gives rise to distinct pathways for expansion (Fig. 2b ). The first pathway recognizes that ineffective policies have limited the supply 28 , 29 . Lax regulations in some regions have resulted in poor environmental stewardship, disease and even collapse, which have compromised the viability of food production in the long run (curve M1 in Fig. 2b ). In other regions, regulations are overly restrictive, convoluted and poorly defined 30 , 31 , and thus limit production (curve M2 in Fig. 2b ). In both cases, improved policies and implementation can increase food production by preventing and ending environmentally damaging mariculture practices (the shift from M1 to M3 in Fig. 2b ) and allowing for environmentally sustainable expansion (the shift from M2 to M3 in Fig. 2b ).