- Create new account

- Reset your password

Gendered Impact on Unemployment: A Case Study of India during the COVID-19 Pandemic

India witnessed one of the worst coronavirus crises in the world. The pandemic induced sharp contraction in economic activity that caused unemployment to rise, upheaving the existing gender divides in the country. Using monthly data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy on subnational economies of India from January 2019 to May 2021, we find that a) unemployment gender gap narrowed during the COVID-19 pandemic in comparison to the pre-pandemic era, largely driven by male unemployment dynamics, b) the recovery in the post-lockdown periods had spillover effects on the unemployment gender gap in rural regions, and c) the unemployment gender gap during the national lockdown period was narrower than the second wave.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has adversely impacted labour markets all around the world. According to the International Labour Organization, the working hours lost in 2020 were equal to 255 million full-time jobs, which translated into labour income losses worth US$3.7 trillion (International Labour Organization 2021). Due to the existing gender inequalities, women were more vulnerable to the economic impact of COVID-19 (Madgavkar et al. 2020). The sudden closure of schools and daycare centres due to the Great Lockdown exacerbated the burden of unpaid care on women (Collins et al. 2020; Power 2020; Czymara et al. 2020; Seck et al. 2021). Women also disproportionately represented the accommodation, food services, and retail and wholesale trade sectors, which were worst-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic (Alon et al. 2020; Adams-Prassl et al. 2020; Bonacini et al. 2021). In most countries, women often work in these sectors without any work protection or job guarantee (United Nations Women 2020), leading them to loose their livelihoods faster than men while also dealing with their deteriorating mental health. India is an interesting case study with one of the lowest female labour force participation rates (LFPRs) globally to analyse how the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the pre-existing gender disparities in unemployment. According to the World Bank data, India’s female LFPRs was approximately 21% in 2019, the lowest among the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and 26 percentage points lower than the global average. An even more troubling fact is that women’s LFPRs has been falling since the mid-2000s (Ghai 2018; Andres et al. 2017; Sarkar et al. 2019). Since the onset of the pandemic, women in India have been increasingly dropping out of the labour force. As seen in Figure 1, the greater female labour force, which comprises unemployed females who are active and inactive job seekers, has been lower than the pre-pandemic average since April 2020. The number of unemployed women actively looking for jobs has also been lower than the pre-pandemic average barring the months of April, May, and December in 2020. On the contrary, the number of women who are unemployed but inactive in their job search has risen drastically, albeit with minor fluctuations, during this period (Figure 2). A recent survey by Deloitte (2021) identified that the burden of household chores and responsibility for childcare and family dependents increased exponentially for women worldwide and more so in India due to the pandemic. The surveyed women mentioned increase in work and caregiving responsibilities as the main reasons for considering leaving the workforce.

Figure 1 : Percent Change in Female Greater Labour Force and Unemployed Active Job Seekers Compared to the Pre-pandemic Average

Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy April 2020 - May 2021

Figure 2: Percent Change in Female Unemployed and Inactive Job Seekers Compared to the Pre-pandemic Average

Figure 3: Unemployment Rate in India (Percent)

Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Jan 2020 - May 2021

This study analyses the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the gender unemployment gap from its onset until the second wave using the subnational-level monthly data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). The gender unemployment gap is defined as the difference between male and female unemployment rates ( Albanesi and Şahin 2018 ). We assess the gender unemployment gap during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic era using a difference-in-differences (DID) model. A preliminary investigation of the gender unemployment gap based on the raw data reveals that the gap declined in the lockdown period compared to the pre-lockdown period (Figure 3). We find the gender gap to widen during the second wave, albeit smaller than the pre-pandemic level.

Although a large number of national-level studies were conducted on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on unemployment (Estupinan and Sharma 2020; Estupinan et al. 2020; Bhalotia et al. 2020; Chiplunkar et al. 2020; Afridi et al. 2021; Deshpande 2020; Desai et al. 2021), this study is among the very first to assess the impact of the second wave of COVID-19 on the unemployment gender gap in India. A previous study found the rise in male unemployment during the lockdown period contributing to a smaller gender gap (Zhang et al. 2021). In this study, we take one step further to assess the effect of the second COVID-19 wave on the unemployment gender gap in India.

The remainder of the article is organised as follows. In Sections 2 and 3, we present the data sources and some facts on the unemployment trend in India. The effects of first and second COVID-19 waves on unemployment disaggregated by gender are discussed in Section 4. Section 5 delves into the gendered impact on unemployment dynamics across urban and rural regions. The concluding remarks are presented in Section 6.

Data and Methodology

In this study, we use the subnational-level monthly employment data from the CMIE from the period of

January 2019 to May 2021 . Starting from January 2016, the CMIE has been conducting household surveys in India on a triennial basis, covering the periods of January to April, May to August, and September to December. This is the only nationally representative employment data in the absence of official government data (Abraham and Shrivastava 2019) and has been used by several employment studies on India (Beyer et al. 2020; Deshpande 2020; Deshpande and Ramachandran 2020).

The employment data are classified into three categories—the number of persons employed, the number of persons unemployed and actively seeking jobs, and the number of persons unemployed and not actively seeking jobs. The sum of these three categories constitutes the greater labour force. The data are also disaggregated by gender (male and female) and residence (rural and urban).[1] For the analysis, we focus on five time periods as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1: Time Periods

For state[2] i at time t, we construct the unemployment rate as given below:

Unemployment rate = Number of persons unemployed and seeking jobs/Greater labour force (1)

Stylised Facts on Unemployment

This section describes some stylised facts based on the subnational unemployment data from February 2019 to May 2021. To this end, we estimate the regression model below:

where Unemp it is the unemployment rate of state i in time t . To see the unemployment dynamics over the period of study, we use a binary variable Month s that takes the value one for month s and 0, otherwise. The model takes into consideration the impact of past unemployment rates, represented by Unemp it −1. Additionally, the state fixed effects δ i are included to account for unobserved, time-invariant state-level characteristics that may potentially confound our estimates.

Figure 4: Trends in Unemployment Rate

Our coefficient of interest is β 1 s which depicts the time trend in unemployment. The results from the model estimation are shown in Figure 4, in which we can see the dynamics of aggregate unemployment in India from February 2019 to May 2021. The vertical axis pertains to coefficient β 1 s , and the horizontal axis corresponds to the respective months. In Figure 4, the aggregate unemployment rate is found to be relatively stable during the pre-pandemic era. This trend faces an overhaul during the national lockdown (April–May 2020) with a structural upward shift in the unemployment rate. The shock to the unemployment rate does not persist as economic recovery during the post-lockdown period enables unemployment to fall steadily from June 2020 onwards. The unemployment rate becomes stable from January to March 2020 as the country returned to a sense of normalcy with the continued resumption of economic activity.[3] However, the economic impact from the onset of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic caused the unemployment rate to rise again in April and May 2021.

Next, we estimate Equation (3) separately for the female and male unemployment rates to assess the gender differential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on unemployment in India.[4]

where binary variable Quarter s takes the value one for quarter s in the time period of our sample. The model also accounts for lagged unemployment effects through Unemp it −1.

Figure 5: Trends in Unemployment Rate by Gender

Figure 5 shows that a stark gender gap in the unemployment rate (distance between the red and blue lines) exists in the pre-pandemic era as the male unemployment rate is consistently lower than that of the female. Figure 5 also shows that the gender gap dynamics are primarily driven by male unemployment. The sharp rise in male unemployment during the national lockdown causes the gender gap to close in Q2 2020. The post-lockdown recovery (Q3–Q4 2020) is found to have a favourable impact on male unemployment, causing gender gap to revert to the pre-pandemic levels. Although both males and females lost jobs during the onset of the second wave (Q2 2021), the gender gap narrowed as males are found to lose more jobs in absolute terms.

Figure 6: Trends in Urban and Rural Unemployment Rate by Gender

Figure 6 shows the estimates of β 1 s (see Equation [3]) for urban and rural unemployment in Panels (a) and (b), respectively. During the national lockdown, the sharp rise in male unemployment is more evident in urban areas than rural. In fact, the national lockdown period dynamics in aggregate male and female unemployment in Figure 5 largely resemble the effects seen in the urban region (see Figure 6, Panel [a]). The post-lockdown recovery suits male unemployment, both in rural and urban areas. Female unemployment remains stable in rural areas during the pandemic.

Figure 7: Trends in Regional Unemployment Rate by Gender

7 c

The subsample regression estimates of β 1 s pertaining to the north, east, west and south regions are shown in Figure 7. All regions witnessed a rise in male unemployment during the national lockdown period. On the contrary, the female unemployment dynamics differ between regions. During the national lockdown period, female unemployment rose in the west and south regions (Panels [c] and [d] in Figure 7). The north region shows an interesting anomaly (Panel [a] in Figure 7). Contrary to other regions, female unemployment dipped steeply in the north during the national lockdown period. East region alone did not

experience any strong movements in female unemployment throughout the pandemic (Panel [b] in Figure 7).

Impact of COVID-19 on Unemployment

Section 3 discussed how the overall unemployment and unemployment gender gap witnessed structural breaks during the COVID-19 pandemic. To further investigate the gender aspect of the COVID-19 unemployment dynamics in India, we begin our empirical exercise by examining the unemployment changes during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic era. We use the following model:

where Period 1 , Period 2 , Period 3 , and Period 4 pertain to lockdown, post-lockdown, post-lockdown normalcy, and second wave time periods, respectively. Besides the overall unemployment, we also estimate Equation (4) for male and female unemployment separately. The results are shown in Table 2. We can see from Column (1) of Table 2 that the overall unemployment rate ( β 11 ) witnessed an increase of 0.066 (statistically significant at one percent level) during the lockdown period in comparison to the pre-pandemic period. This effect was primarily driven by the rise in the male unemployment that shot up by 0.082 during the lockdown period (Column [3]).

The uneven distributional effects of the post-lockdown recovery are seen from β 12 estimates. Male unemployment rose by 0.01, while female unemployment fell by 0.036 in comparison to the pre-pandemic era. The fall in female unemployment does not necessarily indicate that the overall labour conditions improved for women during this period. Equation (1) shows that the unemployment rate is driven by two components. Figure 1 validates that the female unemployment rate fell over time due to the decline in the number of unemployed females actively seeking jobs being higher than the decline in the female labour force.[5]

β 14 estimate in Column (1) indicates that the total unemployment rose by 0.019 (statistically significant at 10 percent level) during the second wave compared to the pre-pandemic period. A comparison between β 14 and β 11 estimates reveals an interesting policy highlight that the second wave’s impact on unemployment was smaller than the nationwide lockdown. Finally, the rise in unemployment during the second wave is primarily driven by male unemployment.

Table 2: Impact of COVID-19 on Unemployment

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, and * p<0.1. The robust standard errors are in parentheses.

Unemployment Gender Gap in Urban and Rural Regions

This section delves further into the gendered impact of lockdown on the unemployment dynamics across urban and rural regions. As defined in Section 1, the unemployment gender gap measures the difference between female and male unemployment rates. To identify the effect of the first and second COVID-19 waves on the unemployment gender gap, we estimate the regression model below:

where Female is a binary variable that takes the value 1 for female unemployment and 0, otherwise.

Table 3 shows the estimation results of Equation (5). We discuss the coefficient estimates that are found to be significant. The significant β 1 coefficient reiterates that the unemployment gender gap was an existential problem in India even before the COVID-19 pandemic. The β 31 estimates reveal that the urban region dynamics drove the narrow unemployment gender gap during the lockdown period. Although the magnitude of the narrowing gap during the lockdown did not persist to the post-lockdown period ( β 32 ), rural regions experienced a narrow unemployment gender gap (marginally significant at 10%). This trend continues even in the post-lockdown normalcy period ( β 33 ) as the unemployment gender gap is narrower than the pre-pandemic level by 0.047 in the rural region. This highlights the possibility that the post-lockdown recovery process had a spillover effect on the unemployment gender gap in rural regions. Finally, β 34 estimates show that the narrowing gender gap trend persists only in the urban region during the second wave.

Table 3: Impact of COVID-19 on Unemployment across Urban and Rural Regions during the post-lockdown and post-lockdown normalcy periods.

This article analyses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic vis-à-vis the pre-pandemic period on the gender unemployment gap. Our findings indicate that the gender gap in unemployment narrowed during the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily driven by male unemployment dynamics. Interestingly, we find that female unemployment declined during the post-lockdown period. Such a decline was likely driven by women dropping out of the labour force rather than a dip in the absolute number of unemployed persons. Further, the region-wide subsample analysis finds the unemployment gender gap in urban regions to narrow across all periods of the COVID-19 era. In contrast, the rural regions witness narrowing gender gap during the post-lockdown normalcy. This indicates that the rural regions’ unemployment gender gap witnessed spillover effects from recovery associated with the economic reopening. Finally, the narrow gender gap (compared to the pre-pandemic level) is smaller during the second wave.

There is a looming uncertainty whether the impending third wave will further narrow the gender unemployment gap at the expense of increasing male unemployment and females being pushed out of the workforce. Further research is required with a more extended period of assessment and focussed on household-level data to understand the difference in the impact of COVID-19 on the gender unemployment gap across the different parts of the country and income strata.

The authors thank Paul Cheung and the anonymous referee for their valuable comments and feedback. They also thank Rohanshi Vaid for her excellent research assistance.

[1] The data are not available for Jammu and Kashmir, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, Lakshadweep, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Sikkim. Hence, the main analysis focuses on only 26 subnational economies.

[2] The terms “state” and “subnational economy” are used interchangeably throughout the article.

[3] According to the official data, power consumption grew by 10.2% in January 2021; the highest growth rate in three months, which was indicative of higher commercial and industrial demand (Press Trust of India 2021).

[4] In order to obtain the unemployment dynamics on a quarterly basis, Equation (2) is revised to Equation (3) with dummies pertaining to quarter instead of month.

[5] This reason is also validated by CMIE who found the female labour participation in urban regions to fall to 7.2% in October 2020, the lowest since the organisation started measuring this indicator in 2016 (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy 2020).

Abraham, Rosa and Anand Shrivastava (2019): “How Comparable Are India’s Labour Market Surveys? An Analysis of NSS, Labour Bureau, and CMIE Estimates,’’ Azim Premji University CSE Working Paper 2019-03.

Adams-Prassl, et al (2020): “Work Tasks That Can be Done From Home: Evidence on Variation Within & Across Occupations and Industries,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14901.

Afridi, Farzana, Kanika Mahajan and Nikita Sangwan (2021): “Employment Guaranteed? Social Protection during a Pandemic,” Oxford Open Economics, Vol 1, https://doi.org/10.1093/ooec/odab003 .

Albanesi, Stephania and Ayşegül Şahin (2018): “The Gender Unemployment Gap,” Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol 30, pp 47–67.

Alon, Titan, et al (2020): “The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality,” Technical Report w26947, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Andres, Luis A, et al (2017): “ Precarious Drop: Re- Assessing Patterns of Female Labor Force Participation in India ,” Technical Report 5595-1149, Vol 8024, World Bank, Washington DC.

Beyer, Robert C.M., Tarun Jain and Sonalika Sinha (2020): “Lights Out? COVID-19 Containment Policies and Economic Activity,” Policy Research Working Papers , The World Bank.

Bhalotia, Shania, Swati Dhingra and Fjolla Kondirolli (2020): “City of Dreams no More: The Impact of Covid-19 on Urban Workers in India,” Centre for Economic Performance, https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cepcovid-19-008.pdf.

Bonacini, Luca, Giovanni Gallo and Sergio Scicchitano (2021): “Working from Home and Income Inequality: Risks of A ‘New Normal’ With COVID-19,” Journal of Population Economics , Vol 34, No 1, pp 303–60.

Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (2020): “Female Workforce Shrinks in Economic Shocks.” www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=20201214124829&msec=703&ver=pf

Chiplunkar, Gaurav, Erin Kelley and Gregory Lane (2020): “Which Jobs Are Lost during a Lockdown? Evidence from Vacancy Postings in India,” SSRN Journal. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3659916

Collins, Caitlyn, et al (2020): “COVID-19 and the Gender Gap in Work Hours,” Gender, Work & Organization , Vol 28, pp 101–12, https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12506 .

Czymara, Chritian S., Alexander Langenkamp and Tomás Cano (2020): “Cause For Concerns: Gender Inequality In Experiencing The COVID-19 Lockdown In Germany,” European Societies , Vol 23, Sup 1, pp 1–14.

Deloitte (2021): “Women @ Work: A Global Outlook India Findings,” https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/about-deloitte/in-women-at-work-india-outlook-report-noexp.pdf.

Desai, Sonalde, Neerad Deshmukh and Santanu Pramanik (2021): “Precarity in a Time of Uncertainty:

Gendered Employment Patterns during the Covid-19 Lockdown in India,” Feminist Economics , Vol 27, Nos 1–2, pp 152–72.

Deshpande, Ashwini (2020): “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Gendered Division of Paid and Unpaid Work: Evidence from India,” IZA – Institute of Labor Economics.

Deshpande, Ashwini and Rajesh Ramachandran (2020): “Is Covid-19 ‘The Great Leveler’?” The

Critical Role of Social Identity in Lockdown-induced Job Losses , GLO Discussion Paper 622, Global Labor Organization (GLO).

Estupinan, Xavier and Mohit Sharma (2020): “Job and Wage Losses in Informal Sector due to the COVID-19 Lockdown Measures in India,” SSRN Electronic Journal .

Estupinan, Xavier, et al (2020): “Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Labor Supply and Gross Value Added in India,” SSRN Electronic Journal .

Ghai, Surbhi (2018): “The Anomaly of Women’s Work And Education In India,” Working Paper 368, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), New Delhi.

International Labour Organization (2021): “ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. Seventh

Edition,” Updated Estimates and Analysis. Int Labour Organ .

Madgavkar, Anu, et al (2020): “COVID19 and Gender Equality: Countering The Regressive Effects,” McKinsey Global Institute, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/covid-19-and-gender-equality-countering-the-regressive-effects .

Power, Kate (2020): “The COVID-19 Pandemic has Increased the Care Burden of Women and

Families,” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy , Vol 16, No 1, pp 67–73.

Press Trust of India (2021): “India’s Power Consumption Grows At 3-Month High Rate Of 10.2% In January,” Business Standard India , https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/india-s-power-consumption-grows-at-3-month-high-rate-of-10-2-in-january-121020100353_1.html.

Sarkar, Sudipa, Soham Sahoo, and Stephan Klasen (2019): “Employment Transitions Of Women In

India: A Panel Analysis,” World Development , Vol 115, pp 291–309.

Seck, Papa A., et al (2021): “Gendered Impacts of COVID-19 in Asia and the Pacific: Early Evidence on Deepening Socioeconomic Inequalities in Paid and Unpaid Work,” Feminist Economics , Vol 27, Nos 1–2, pp 117–32.

United Nations Women (2020): “From Insights to Action: Gender Equality in the Wake of COVID-19,” Technical report, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2020/Gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-COVID-19-en.pdf.

Zhang, Xuyao, et al (2021): Annual Competitivness Analysis and Gendered Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Unemployment in the Sub-National Economies of India , Singapore: Asia Competitiveness Institute, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

Image Courtesy; Canva

In light of the triple talaq judgment that has now criminalised the practice among the Muslim community, there is a need to examine the politics that guide the practice and reformation of personal....

- About Engage

- For Contributors

- About Open Access

- Opportunities

Term & Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Style Sheet

Circulation

- Refund and Cancellation

- User Registration

- Delivery Policy

Advertisement

- Why Advertise in EPW?

- Advertisement Tariffs

Connect with us

320-322, A to Z Industrial Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai, India 400 013

Phone: +91-22-40638282 | Email: Editorial - [email protected] | Subscription - [email protected] | Advertisement - [email protected]

Designed, developed and maintained by Yodasoft Technologies Pvt. Ltd.

This website uses cookies

The only cookies we store on your device by default let us know anonymously whether you have seen this message. With your permission, we also set Google Analytics cookies. You can click “Accept all” below if you are happy for us to store cookies (you can always change your mind later). For more information please see our Cookie Policy .

Google Analytics will anonymize and store information about your use of this website, to give us data with which we can improve our users’ experience.

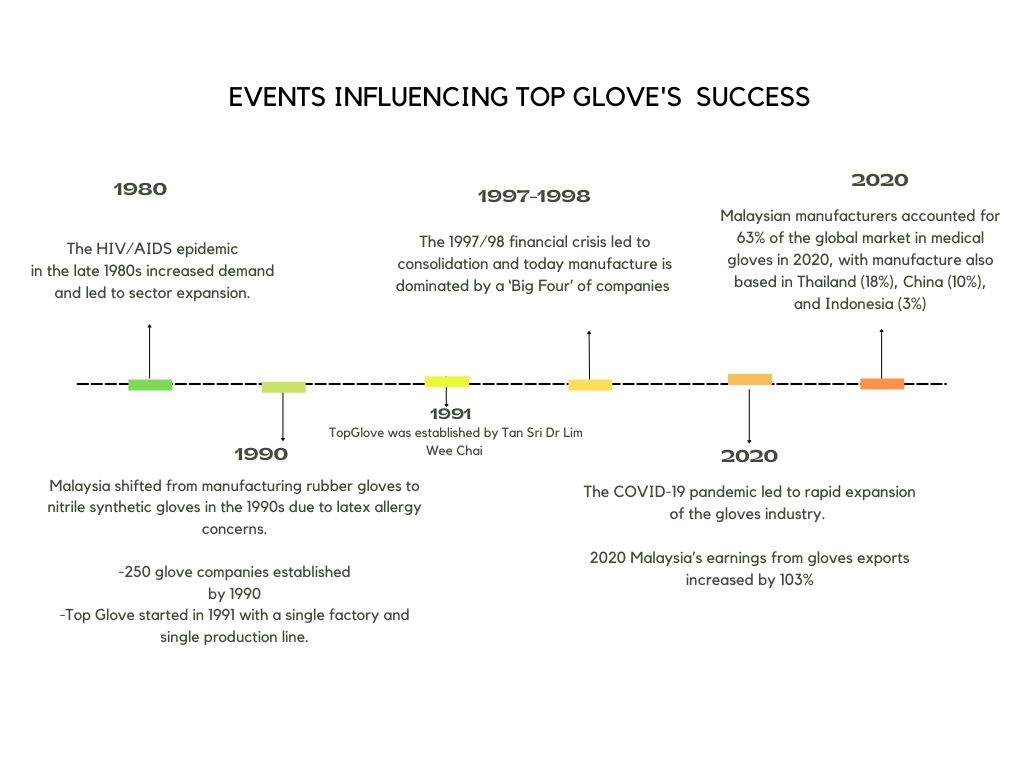

Created in partnership with the Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights

Forced Labour

If you have questions, feedback or you're looking for further help in protecting human rights, please contact us at

Case Studies

This section includes examples of company actions to address forced labour in their operations and supply chains.

Advertisement

Female Labour Force Participation in India: An Empirical Study

- Published: 11 April 2022

- Volume 65 , pages 59–83, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Syamantak Chattopadhyay 1 &

- Subhanil Chowdhury 2

745 Accesses

Explore all metrics

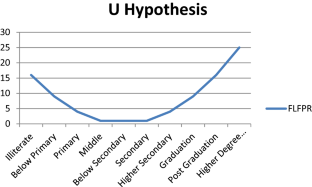

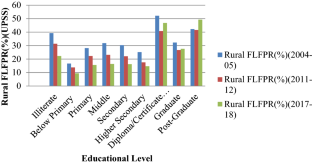

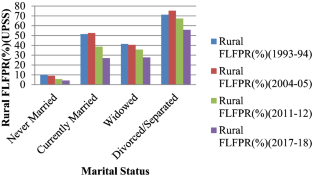

This paper attempts to analyse the factors which affect Indian working age women’s continuous withdrawal from the labourforce. The main objective deals with two specific questions: probing the empirical validity of the U-hypothesis and exploring whether supply side factors could sufficiently explain the falling FLFPR in India, especially in its rural sectors. Through a review of available empirical literature, factors like social constraints, upward mobility among lower castes and household burden have been identified as some of the major determinants. Using three rounds of NSSO data namely 50th round (1993–94), 61st round (2004–05), 68th round (2011–12) of Employment and Unemployment Surveys and the PLFS (2017–18) data, our analysis (across factors) have shown the existence of U-shaped relationship between FLFPR and education, however it shifts downwards with time. The relationship between FLFPR and MPCE deciles is not U-shaped but negative. Women from higher income class are more likely of being graduates thus increasing their probability of joining the labour force; even then a lower labour force participation of women in the upper deciles show the dominance of Income effect over education. It is significant that FLFPR declines with time irrespective of income and education. This indicates existence of factors other than supply side for explaining the problem of falling FLFPR. Particularly, one needs to focus on demand side problems and social-institutional factors inhibiting women from joining the labour force.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Source : Authors’ calculations based on NSSO and PLFS data. Note: The horizontal axis measures decile classes of households based on MPCE

Source : Same as Fig. 2

Similar content being viewed by others

The gender pay gap in the USA: a matching study

Economic instability, income, and unemployment effects on mortality: using SUR panel data in Iran

Hukou reform and labor market outcomes of urban natives in China

For this analysis, data from the year 2004–05 and onwards are used since the coding pattern of 1993–94 was changed subsequently by the NSSO.

Abraham, V. 2009. Employment growth in rural India: Distress-driven? Economic and Political Weekly 44 (16): 97–104.

Google Scholar

Abraham, V. 2013. Missing labour or consistent “De Feminisation”? Economic and Political Weekly 48 (31): 99–108.

Afridi, F., T. Dinkelman, and K. Mahajan. 2018. Why are fewer married women joining the work force in rural India? A decomposition analysis over two decades. Journal of Population Economics 31 (3): 783–818.

Article Google Scholar

Attanasio, O., H. Low, and V. Sánchez-Marcos. 2005. Female labor supply as insurance against idiosyncratic risk. Journal of the European Economic Association 3 (2–3): 755–764.

Bhalla, S., and R. Kaur. 2011. Labour force participation of women in India: some facts, some queries . London: London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE Library.

Bhalotra, S. R., and M. Umana-Aponte. 2012. The dynamics of women's labour supply in developing countries. IZA Discussion Paper No. 4879.

Boserup, E. 2007. Woman’s role in economic development . London: Earthscan.

Chatterjee, E., S. Desai, and R. Vanneman. 2018. Indian paradox: rising education, declining women’s employment. Demographic Research 38: 855.

Chaudhary, R., and S. Verick. 2014. Female labour force participation in India and beyond. ILO Working Papers , (994867893402676).

Chowdhury, S. 2011. Employment in India: What does the latest data show? Economic and Political Weekly 46 (32): 23–26.

Das, M.B., and S. Desai. 2003. Why are educated women less likely to be employed in India?: Testing competing hypotheses . Washington: Social Protection, World Bank.

Das, M.B., and I. Žumbytė. 2017. The motherhood penalty and female employment in urban India . Washington: The World Bank.

Book Google Scholar

Desai, S. 2018. Do public works programs increase women’s economic empowerment: Evidence from rural India, India Human Development Survey , Working Paper No. 2018-02.

Districts of India. 2020. States and UTs. http://districts.nic.in/

Eswaran, M., B. Ramaswami, and W. Wadhwa. 2013. Status, caste, and the time allocation of women in rural India. Economic Development and Cultural Change 61 (2): 311–333.

Goldin, C. 1994. The U-shaped female labor force function in economic development and economic history. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), NBER Working Paper No. 4707

Himanshu. 2011. Employment trends in India: A re-examination. Economic and Political Weekly 46 (37): 43–59.

Kannan, K.P., and G. Raveendran. 2012. Counting and profiling the missing labour force. Economic and Political Weekly 47 (6): 77–80.

Klasen, S., and J. Pieters. 2015. What explains the stagnation of female labor force participation in urban India? The World Bank Economic Review 29 (3): 449–478.

Lahoti, R., and H. Swaminathan. 2013. Economic development and female labor force participation in India. IIM Bangalore Research Paper . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2284073 .

Majumdar, I., and N. Neetha. 2011. Gender dimensions: Employment trends in India, 1993–94 to 2009–10. Economic and Poiltical Weekly 46 (43): 118–126.

Mammen, K., and C. Paxson. 2000. Women’s work and economic development. Journal of Economic Perspectives 14 (4): 141–164.

Maps of India. 2020. Zonal maps of India. https://www.mapsofindia.com/zonal/

Mehrotra, S., and S. Sinha. 2017. Explaining falling female employment during a high growth period. Economic & Political Weekly 52 (39): 54–62.

Naidu, S.C. 2016. Domestic labour and female labour force participation, adding a piece to the puzzle. Economic and Political Weekly 50 (44&45): 101–107.

Neff, D., Sen, K., & Kling, V. (2012). The puzzling decline in rural women's labor force participation in India: A reexamination. German Institute of Global and Area Studies(GIGA) Working Paper No 196.

Olsen, W., and S. Mehta. 2006. Female labour participation in rural and urban India: Does housewives’ work count? Radical Statistics 93: 57.

Rangarajan, C., P. I. Kaul, and Seema. 2011. Where is the missing labour force?. Economic and Political Weekly 46 (39): 68–72.

Srivastava, N., and R. Srivastava. 2010. Women, work, and employment outcomes in rural India. Economic and Political Weekly 45 (28): 49–63.

Tansel, A. 2002. Economic development and female labour force participation in Turkey: time series evidence and cross-section estimates. ERF , WP ,0124.

Thomas, J.J. 2012. India's labour market during the 2000s: Surveying the changes. Economic and Political Weekly 47 (51): 39–51.

Download references

No funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Studies in Social Sciences Calcutta, Calcutta, India

Syamantak Chattopadhyay

St. Xavier’s University Kolkata, Calcutta, India

Subhanil Chowdhury

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Subhanil Chowdhury .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Predicted Probabilities Obtained from Logistic Regression with Statistical Significance

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Chattopadhyay, S., Chowdhury, S. Female Labour Force Participation in India: An Empirical Study. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 65 , 59–83 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-022-00362-0

Download citation

Accepted : 08 March 2022

Published : 11 April 2022

Issue Date : March 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-022-00362-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Female Labour Force Participation Rate

- Labour Market

- U-Hypothesis

- Indian Economy

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Casestudies

Forced labour

"how can a company practically and responsibly identify and address problems of forced labour in lower tiers of its supply chain, particularly when it extends into areas or sectors known to use forced labour", dilemmas and case studies.

- Access to water

- Child labour

- Community relocation

- Conflict minerals

- Cumulative impacts

- Doing business in conflict-affected countries

- Freedom of association

- Freedom of religion

- Freedom of speech

- Gender equality

- Health and safety

- Human trafficking

- Indigenous peoples’ rights

- Living wage

- Migrant workers

- Non-discrimination and minorities

- Product misuse

- Security forces

- Stabilisation clauses

- Working hours

- Working with SOEs

- Case studies

This page presents all relevant good practice case studies that showcase how business have addressed the Forced labour dilemma. Case studies have been developed in close collaboration with a range of multi-national companies and relevant government, inter-governmental and civil society stakeholders. We also draw on public domain sources, including the UN Global Compact's own published Communications on Progress through which signatories are required to report on their performance against the Ten Principles.

The case studies explore the specific dilemmas and challenges faced by each organisation, good practice actions they have taken to resolve them and the results of such action. We reference challenges as well as achievements and invite you to submit commentary and suggestions through the Forum.

IN-DEPTH (Print seperately) Responsible Cotton Network: Combating forced child labour during the cotton harvest - Uzbekistan

IN-DEPTH (Print seperately) ICC: Combating slave labour in the Brazilian charcoal and steel sector - Brazil

Verite, a US-based NGO, conducts research on forced labour and human trafficking around the world, with a particular focus on exploitive labour broker practices. Some of Verite’s projects include:

· The use of forced labour in the electronics sector in Malaysia

· Unscrupulous labour practices in the Guatemalan palm oil sector

· Human rights abuses perpetuated throughout global supply chains of artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM), with a focus on ASM gold in Peru

Verite aims to engage with companies in implementing strategies to identify and eliminate exploitive labour broker practices from their supply chains in order to minimise the risk of forced labour. Verite also provides courses that provide participants the competencies to perform audits of labour practices within companies, with a focus on auditing compensation, business ethics and working hours. These audits are run by Verite’s partnership organisation, the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC).

http://www.verite.org

Established in 2002, the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI) is a partnership between NGOs, trade unions, cocoa processors and companies focused on tackling exploitative child labour. Member companies include: Cargill, Hershey’s, Kraft Foods, Mars, Nestle, Twinings and Toms International, amongst others. The ICI works at both the national- and the community-level to foster programmes to combat and prevent forced child labour. The ICI has implemented programmes in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana.

http://www.cocoainitiative.org

Business Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI) was launched in 2003 by the Foreign Trade Association, a Brussels-based trade association that represents the trade interests of European companies. BSCI acts as an umbrella group for around 1,300 retail companies focused on improving working conditions in their supply chains.

The organisation has developed the BSCI code which addresses a wide range of supply chain issues, including a prohibition on forced labour as well as disciplinary measures for suppliers failing to comply with the code. Members adopt the BSCI Code internally and require their suppliers to come into compliance. BSCI provides capacity building in the form of training and technical assistance. BSCI also relies on external monitoring to ensure conformance to the code. BSCI is a member of the UN Global Compact.

http://www.bsci-eu.org

Founded in 2004, FFC is a New York-based membership organisation of companies seeking to improve working conditions in factories that make consumer goods. FFC shares compliance data between companies in order to improve the availability and standardisation of standards and audits on social, environmental and security standards. Amongst its members are Wal-Mart, Reebok, and Levi Strauss & Co. The FFC receives funding from the US Department of State. Its founders include Reebok, the National Retail Federation and the Retail Council of Canada.

http://www.fairfactories.org

The International Council on Metals and Mining (ICMM) is a CEO-led initiative founded in 2011 which focuses on promoting good practice in the mining and metals sector. Composed of 18 of the world’s largest mining companies and 30 associations, its corporate members include Anglo-American, BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, Vale, Newmont and Mitsubishi Materials. Members commit to implementing ICMM’s Sustainable Development Framework. The framework comprises a set of 10 principles focused on integrating ethnical business practices across the mining sector, supported by public reporting and independent third-party assurance. The principles were adopted in May 2003. Principle 3 prohibits the use of forced, compulsory and child labour.

Global paper manufacturer Glatfleter implements a policy focused on combating forced labour in its supply chain, based on ILO conventions and national law. The company’s ‘Child and Forced Labor Policy’, which “recognises regional and cultural differences”, explicitly prohibits exploitative working conditions and the use of any forced labour. In order to address the problem, Glatfelter engages with suppliers, industry organisations, civil society representatives and governments.

In its policy document, Glatfelter acknowledges that the risks are particularly elevated for companies sourcing raw agricultural products, due to supply chains which are often long, complex and at risk of perpetuating forced labour use. The company strongly encourages its suppliers, subcontractors and business partners to adhere to its principles on the issue.

http://www.glatfelter.com

As part of its ‘No Child or Forced Labour’ policy, Indian multi-business conglomerate ITC Limited prohibits the use of forced or compulsory labour at all of its units, and maintains that no employee be made to work against their will or be subject to corporal punishment or coercion. The policy is made available to all employees through accessible induction programmes, policy manuals and intranet portals. Trade unions also engage with workers at each ITC unit to ensure they are aware of their rights. All units provide an annual report on any incidents of child or forced labour to divisional heads, and are subject to Corporate Internal Audits and Environment, Health and Safety assessments.

http://www.itcportal.com

Under the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act of 2010 (SB 657), which applies to retail sellers and manufacturers “doing business in the state”, multinational automaker Ford has disclosed its four key principles for the prevention of forced labour use in its supply chains:

· Firstly, the company engages in risk assessment of its supply base, taking into account the geographic context, commodity type, level of labour required for production, supplier ownership structure and quality performance and the nature of the transaction.

· Secondly, Ford operates purchase orders which require suppliers to certify compliance with standard terms and conditions on the prohibition of forced labour.

· Thirdly, along with the other members of the Automotive Industry Action Group (AIAG), Ford conducts training and capacity building for global purchasing staff and suppliers in high-risk markets.

· Finally, the company carries out regular audits of at-risk ‘Tier 1’ supplier factories, resulting, if necessary, in the completion of corrective action plans to then be reassessed six to 12 months after the original audit.

http://www.ford.com

On 6 May 2013, global sportswear brand Adidas announced that it was gradually launching a new whistle-blowing helpline at all of its Asia-based operations – to enable factory employees to voice potential grievances about labour violations. Workers employed in factories supplying Adidas will be able to send anonymous text messages – limited to 160 characters – to the SMS Worker Hotline . While managers at the factories will be the main recipients of these text messages, Adidas will also be able to access them. This will allow the company to take direct action – particularly in cases where serious violations such as forced, bonded or child labour are identified.

Adidas acknowledges that workers sometimes do not feel comfortable in bringing issues to the attention of factory management in person. The move by the Germany multinational follows a spate of deadly incidents in Bangladeshi garment factories during 2013, one of the most important source countries for the global clothing industry. In this context, the establishment of worker hotlines can enable factory employees to raise practical issues related to health and safety, as well as labour violations.

Ford implements a supplier training programme to promote responsible working conditions in its supply chain. The programme is focused on “high-priority” countries including those in:

- The Americas (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and Venezuela)

- Asia (China, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam)

- Europe, the Middle East and Africa (Morocco, Romania, Russia, South Africa and Turkey)

Training was originally based on Ford’s own Code of Basic Working Conditions and was implemented by Ford at supplier factories. The programme is based on one-day interactive workshops involving multiple suppliers, and is targeted at human resources, health and safety, and legal managers within supplier companies. Each participant is expected to ‘cascade’ relevant training materials to personnel within their own companies – and to their own direct suppliers. Indeed, Ford requires confirmation from participant suppliers that training information has been disseminated to these target groups within four months of each workshop.

The programme has since evolved into a joint initiative with other car manufacturers – in order to reach a larger number of suppliers (many of whom provide parts to multiple brands) more efficiently. This resulted in the formation of the Automotive Industry Action Group (‘AIAG’) through which car manufacturers from North America, Europe and Asia have developed common guidance statements on working conditions – as well as an online training programme for suppliers to the sector. These cover a range of issues including child labour, forced labour, freedom of association, discrimination, health and safety, wages and working hours.

Ford estimates that its training activity (carried out both unilaterally and in conjunction with the AIAG) has reached 2,900 supplier representatives – and been ‘cascaded’ to around 25,000 supplier managers, 485,000 workers and 100,000 sub-tier supplier companies.

Ending Forced Labor in India: What Does It Take?

For immediate release: Thursday, March 31, 2016

Boston, MA – Neither legal nor socio-economic interventions have eradicated widespread forced and bonded labor in India. But a new report published today by Harvard University’s FXB Center for Health and Human Rights provides some hope for progress. With detailed evidence and meticulous analysis, the report documents the very positive impact of a community organization’s work on entrenched labor exploitation in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state. It is the first report of its kind.

Entitled “When We Raise Our Voice: The Challenge of Eradicating Labor Exploitation,” the report examines the impact of a multifaceted, sustained, community-based intervention to eradicate forced and bonded labor. It centers on the efforts of Manav Sansadhan Evam Mahila Vikas Sansthan (MSEMVS), a local NGO dedicated to the elimination of exploitative labor practices within low caste, remote communities, home to some of India’s most economically disenfranchised and vulnerable populations. Agriculture, brick making, and carpet weaving—well known hubs of forced and abusive labor—are the main sources of employment in this area.

According to the report, MSEMVS has had a dramatic impact on improving the lives of individuals and households in the communities studied. The organization’s approach, the report claims, is a promising example of the robust, rights enhancing role such community empowerment interventions can play. Among other positives, MSEMVS increases residents’ understanding of legal rights and available legal support, and fosters critically important opportunities for education and new skill development.

Key findings attesting to the success of the MSEMVS approach include the following:

- Improved labor conditions, including dramatic reductions in threats of physical violence.

- Markedly improved food security and food availability, leading to increases in daily food intake and regular meals.

- Increased uptake of social protection and other government services by community members.

- Significantly reduced debt and a lowering of debt related to medical expenses.

Given the entrenched and devastating impact of forced labor in India, these findings are both encouraging and urgent. They suggest that past failures do not justify apathy or inaction. On the contrary, the report shows that much more can be done to support community-based efforts to eradicate some of the most egregious labor and human rights violations of our age.

For additional information, please contact Tizzy Tulloch, Harvard FXB communications director, at [email protected] or (617) 432-7134.

The FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University is a university-wide interdisciplinary center that conducts rigorous investigation of the most serious threats to health and wellbeing globally. Based at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, we work closely with scholars, students, the international policy community, and civil society to engage in ongoing strategic efforts to promote equity and dignity for those oppressed by grave poverty and stigma around the world. http://fxb.harvard.edu

What’s going on with India’s female labour force participation?

Why india's female labour force participation rate remains low compared to global levels, and what needs to be done to change it..

READ THIS ARTICLE IN

Labour force participation rate (LFPR) is defined as the percentage of people in the labour force (that is, working, seeking, or available for work) among the population. LFPR includes those who are self-employed (for instance, in agriculture, forestry, fishing, etc. for their own consumption), salaried employees or casual labour, and those who are unemployed.

What’s happening with India’s female labour force participation rate (FLFPR)?

India is home to approximately 663 million women, of which approximately 450 million women fall in the working age of 15–64 years. India’s FLFPR had been showing a sharp declining trend over the last three decades, from 30.2 percent in 1990 to hitting an all-time low of 17.5 percent in 2018, as per reports by World Bank, Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), and Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS). (The PLFS is India’s official labour force survey, and became an annual exercise only in 2017–18.)

Unlike the downward trend India has seen in the FLFPR since the 1990s, the 2020–21 PLFS 1 for all ages shows a significant improvement in the last three years, going up from 17.5 percent to 24.8 percent (for women aged 15 and above, the rate increased from 23.3 percent in 2017–18 to 32.8 in 2020–21). A recent press release from the Ministry of Finance highlights that this improvement can be attributed to a range of factors, including progressive labour reform measures, better employment trends in the manufacturing sector, increasing share of self-employed people, and a rise in formal employment levels.

The global FLFPR is 52.4 percent (ages 15+), and has been at a similar level for the last three decades. However, in developing countries and emerging economies, there is a significant variation. In the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia, this rate is approximately 25 percent, whereas it reaches up to approximately 66 percent in East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Interestingly, we don’t see such a trend variation in men’s LFPR, which stands at approximately 80 percent across economies.

Why has India’s FLFPR been low?

Informality.

According to the PLFS, we have approximately 166 million women either working, seeking work, or available for work. Out of the population of working women, more than 90 percent work in the informal sector. They are either self-employed or casual workers, predominantly in agricultural and construction sectors. This means that they face increased exploitation, poor working conditions, lack of mobility, and higher risk of violence . This discourages women from entering the workforce.

Patriarchal social norms

There is low support in society for working women. This arises from patriarchal structures, which dictate that women prioritise their domestic responsibilities over professional aspirations. The disproportionate burden of household duties, accompanied by mobility and safety constraints, results in women forgoing their employment. A recent NITI Aayog report states that women in India spend 9.8 times more time than men on unpaid domestic chores (against a global average of 2.6 as reported by UN Women). Globally, unpaid care work is the key reason that women are outside the labour force whereas for men it is “being in education, sick, or disabled ”. Additionally, deep-rooted social norms and lack of agency leave women with little choice in their employment decisions.

A large proportion of educated women are full-time housewives engaged in domestic household chores.

A large proportion of educated women are full-time housewives engaged in domestic household chores such as cooking, cleaning, and childcare. Their services are not paid for and neither are they accounted for in the FLFPR. Their economic output is not included in the GDP either. A 2023 report by State Bank of India suggests that unpaid women’s total contribution to the economy is around INR 22.7 lakh crore—approximately 7.5 percent of India’s GDP.

Economists have argued that India’s FLFPR is not as low as commonly assumed, and that including unpaid work in the calculation will improve this number. A working paper by the Economic Advisory Council highlights that the PLFS does not capture “economically productive work done by women like poultry farming, milking of cows, etc. as part of their domestic duties”. Upon correcting for this omission, the Economic Survey 2022-2023 estimated an FLFPR of 46.2 percent for 2020-21.

While we need to figure out ways to measure unpaid care work, ensure better estimations, and acquire timely, high-quality data from international and national statistical agencies, this may also reinforce patriarchal norms about women’s roles in the household and limit the opportunities for women who would like to work outside of their homes.

Structural changes in the economy are contributing to the recent rise in the FLFPR

Recent PLFS data shows a possible Feminisation U Hypothesis in female participation rates in India. This hypothesis was created on the basis of a cross section of 169 countries from 1990 to 2013. It shows that the early stages of economic growth are accompanied by a decline in female labour force participation. This is because women who were previously working to make ends meet can now opt out of the workforce due to rising household incomes. However, as incomes rise further, women tend to become economically active again. And this increase in economic activity tends to be accompanied by a drop in both fertility rates and the gender education gap.

Despite a significant positive trend, women’s labour force participation remains considerably low in comparison to that of men.

The recent improvement in India’s FLFPR can be explained by the structural changes the nation is experiencing, including a decline in fertility rates and improvement of women’s education. Despite this significant positive trend, women’s labour force participation remains considerably low in comparison to that of men (57.5 percent). Moreover, it represents the underutilisation of their capacity, given that approximately 70 percent of all Indian women of working age remain outside the labour force at present. Another concern is that the increase in women’s share in the labour force post pandemic is primarily driven by rural women joining the workforce, out of necessity , as self-employed workers.

What could full female participation in the workforce look like for India?

Unlocking the full potential of women in our workforce would provide multiple times the return on initial investments made by the government and businesses. As per McKinsey Global Institute’s report , India could achieve an 18 percent increase over business-as-usual GDP (USD 770 billion) by 2025.

The real economic, business, and societal value of the participation of women in India’s labour force can only be achieved through the active involvement of women across the formal economic ecosystem. Studies have shown how, in advanced economies, women in professional occupations outsource their care work , which further results in employment and income generation for more people. Similarly, Indian women and the economy will immensely benefit from solutions that focus on improving the participation of women in the formal economy. This will include reducing, redistributing, and rewarding unpaid care work.

- The PLFS surveyed 1,00,344 households (55,389 in rural areas and 44,955 in urban areas) and 4,10,818 people in the period from July 2020 to June 2021 to arrive at these numbers. Therefore, its results should be viewed as estimates and not as absolute figures.

- Learn about the widening gender gap in the workforce.

- Learn how philanthropy can be mobilised to benefit women entrepreneurs in India.

- Learn about how Indians view gender roles in family and society.

Savita, a farmer in rural Maharashtra, tends to her farm from sunrise until sunset to provide a simple meal for her children in the evening. Saloni, a bank manager in […]

Shruti Deora is an associate principal and lead for ecosystem engagement and policy advisory at Sattva Consulting . She has worked with multinational organisations in India and globally and led engagements with social development organisations, collaboratives, government stakeholders, and international foundations. She has expertise in strategy, implementation, technology, and data in gender and education projects. Shruti is a chartered accountant and an alumna of IIM Kozhikode and Takshila Institute.

If you like what you're reading and find value in our articles, please support IDR by making a donation.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 18 January 2024

The impact of artificial intelligence on employment: the role of virtual agglomeration

- Yang Shen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6781-6915 1 &

- Xiuwu Zhang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 122 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

49k Accesses

3 Citations

16 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies

Sustainable Development Goal 8 proposes the promotion of full and productive employment for all. Intelligent production factors, such as robots, the Internet of Things, and extensive data analysis, are reshaping the dynamics of labour supply and demand. In China, which is a developing country with a large population and labour force, analysing the impact of artificial intelligence technology on the labour market is of particular importance. Based on panel data from 30 provinces in China from 2006 to 2020, a two-way fixed-effect model and the two-stage least squares method are used to analyse the impact of AI on employment and to assess its heterogeneity. The introduction and installation of artificial intelligence technology as represented by industrial robots in Chinese enterprises has increased the number of jobs. The results of some mechanism studies show that the increase of labour productivity, the deepening of capital and the refinement of the division of labour that has been introduced into industrial enterprises through the introduction of robotics have successfully mitigated the damaging impact of the adoption of robot technology on employment. Rather than the traditional perceptions of robotics crowding out labour jobs, the overall impact on the labour market has exerted a promotional effect. The positive effect of artificial intelligence on employment exhibits an inevitable heterogeneity, and it serves to relatively improves the job share of women and workers in labour-intensive industries. Mechanism research has shown that virtual agglomeration, which evolved from traditional industrial agglomeration in the era of the digital economy, is an important channel for increasing employment. The findings of this study contribute to the understanding of the impact of modern digital technologies on the well-being of people in developing countries. To give full play to the positive role of artificial intelligence technology in employment, we should improve the social security system, accelerate the process of developing high-end domestic robots and deepen the reform of the education and training system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

Participatory action research

Introduction.

Ensuring people’s livelihood requires diligence, but diligence is not scarce. Diversification, technological upgrading, and innovation all contribute to achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of full and productive employment for all (SDGs 8). Since the outbreak of the industrial revolution, human society has undergone four rounds of technological revolution, and each technological change can be regarded as the deepening of automation technology. The conflict and subsequent rebalancing of efficiency and employment are constantly being repeated in the process of replacing people with machines (Liu 2018 ; Morgan 2019 ). When people realize the new wave of human economic and social development that is created by advanced technological innovation, they must also accept the “creative destruction” brought by the iterative renewal of new technologies (Michau 2013 ; Josifidis and Supic 2018 ; Forsythe et al. 2022 ). The questions of where technology will eventually lead humanity, to what extent artificial intelligence will change the relationship between humans and work, and whether advanced productivity will lead to large-scale structural unemployment have been hotly debated. China has entered a new stage of deep integration and development of the “new technology cluster” that is represented by the internet and the real economy. Physical space, cyberspace, and biological space have become fully integrated, and new industries, new models, and new forms of business continue to emerge. In the process of the vigorous development of digital technology, its characteristics in terms of employment, such as strong absorption capacity, flexible form, and diversified job demands are more prominent, and many new occupations have emerged. The new practice of digital survival that is represented by the platform economy, sharing economy, full-time economy, and gig economy, while adapting to, leading to, and innovating the transformation and development of the economy, has also led to significant changes in employment carriers, employment forms, and occupational skill requirements (Dunn 2020 ; Wong et al. 2020 ; Li et al. 2022 ).

Artificial intelligence (AI) is one of the core areas of the fourth industrial revolution, along with the transformation of the mechanical technology, electric power technology, and information technology, and it serves to promote the transformation and upgrading of the digital economy industry. Indeed, the rapid iteration and cross-border integration of general information technology in the era of the digital economy has made a significant contribution to the stabilization of employment and the promotion of growth, but this is due only to the “employment effect” caused by the ongoing development of the times and technological progress in the field of social production. Digital technology will inevitably replace some of the tasks that were once performed by human labour. In recent years, due to the influence of China’s labour market and employment structure, some enterprises have needed help in recruiting workers. Driven by the rapid development of artificial intelligence technology, some enterprises have accelerated the pace of “machine replacement,” resulting in repetitive and standardized jobs being performed by robots. Deep learning and AI enable machines and operating systems to perform more complex tasks, and the employment prospects of enterprise employees face new challenges in the digital age. According to the Future of Jobs 2020 report released by the World Economic Forum, the recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the rapid development of automation technology are changing the job market much faster than expected, and automation and the new division of labour between humans and machines will disrupt 85 million jobs in 15 industries worldwide over the next five years. The demand for skilled jobs, such as data entry, accounting, and administrative services, has been hard hit. Thanks to the wave of industrial upgrading and the vigorous development of digitalization, the recruitment demand for AI, big data, and manufacturing industries in China has maintained high growth year-on-year under the premise of macroenvironmental uncertainty during the period ranging from 2019 to 2022, and the average annual growth rate of new jobs was close to 30%. However, this growth has also aggravated the sense of occupational crisis among white-collar workers. The research shows that the agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, fishery, mining, manufacturing, and construction industries, which are expected to adopt a high level of intelligence, face a high risk of occupational substitution, and older and less educated workers are faced with a very high risk of substitution (Wang et al. 2022 ). Whether AI, big data, and intelligent manufacturing technology, as brand-new forms of digital productivity, will lead to significant changes in the organic composition of capital and effectively decrease labour employment has yet to reach consensus. As the “pearl at the top of the manufacturing crown,” a robot is an essential carrier of intelligent manufacturing and AI technology as materialized in machinery and equipment, and it is also an important indicator for measuring a country’s high-end manufacturing industry. Due to the large number of manufacturing employees in China, the challenge of “machine substitution” to the labour market is more severe than that in other countries, and the use of AI through robots is poised to exert a substantial impact on the job market (Xie et al. 2022 ). In essence, the primary purpose of the digital transformation of industrial enterprises is to improve quality and efficiency, but the relationship between machines and workers has been distorted in the actual application of digital technology. Industrial companies use robots as an entry point, and the study delves into the impact of AI on the labour market to provide experience and policy suggestions on the best ways of coordinating the relationship between enterprise intelligent transformation and labour participation and to help realize Chinese-style modernization.

As a new general technology, AI technology represents remarkable progress in productivity. Objectively analysing the dual effects of substitution and employment creation in the era of artificial intelligence to actively integrate change and adapt to development is essential to enhancing comprehensive competitiveness and better qualifying workers for current and future work. This research is organized according to a research framework from the published literature (Luo et al. 2023 ). In this study, we used data published by the International Federation of Robotics (IFR) and take the installed density of industrial robots in China as the main indicator of AI. Based on panel data from 30 provinces in China covering the period from 2006–2020, the impact of AI technology on employment in a developing country with a large population size is empirically examined. The issues that need to be solved in this study include the following: The first goal is to examine the impact of AI on China’s labour market from the perspective of the economic behaviour of those enterprises that have adopted the use of industrial robots in production. The realistic question we expect to answer is whether the automated processing of daily tasks has led to unemployment in China during the past fifteen years. The second goal is to answer the question of how AI will continue to affect the employment market by increasing labour productivity, changing the technical composition of capital, and deepening the division of labour. The third goal is to examine how the transformation of industrial organization types in the digital economy era affects employment through digital industrial clusters or virtual clusters. The fourth goal is to test the role of AI in eliminating gender discrimination, especially in regard to whether it can improve the employment opportunities of female employees. Then, whether workers face different employment difficulties in different industry attributes is considered. The final goal is to provide some policy insights into how a developing country can achieve full employment in the face a new technological revolution in the context of a large population and many low-skilled workers.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section Literature Review, we summarize the literature on the impact of AI on the labour market and employment and classify it from three perspectives: pessimistic, negative, and neutral. Based on a literature review, we then summarize the marginal contribution of this study. In Section Theoretical mechanism and research hypothesis, we provide a theoretical analysis of AI’s promotion of employment and present the research hypotheses to be tested. In Section Study design and data sources, we describe the data source, variable setting and econometric model. In Section Empirical analysis, we test Hypothesis 1 and conduct a robustness test and the causal identification of the conclusion. In Section Extensibility analysis, we test Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3, as well as testing the heterogeneity of the baseline regression results. The heterogeneity test employee gender and industry attributes increase the relevance of the conclusions. Finally, Section Conclusions and policy implications concludes.

Literature review

The social effect of technological progress has the unique characteristics of the times and progresses through various stages, and there is variation in our understanding of its development and internal mechanism. A classic argument of labour sociology and labour economics is that technological upgrading objectively causes workers to lose their jobs, but the actual historical experience since the industrial revolution tells us that it does not cause large-scale structural unemployment (Zhang 2023a ). While neoclassical liberals such as Adam Smith claimed that technological progress would not lead to unemployment, other scholars such as Sismondi were adamant that it would. David Ricardo endorsed the “Luddite fear” in his book On Machinery, and Marx argued that technological progress can increase labour productivity while also excluding labour participation, thus leaving workers in poverty. The worker being turned ‘into a crippled monstrosity’ by modern machinery. Technology is not used to reduce working hours and improve the quality of work, rather, it is used to extend working hours and speed up work (Spencer 2023 ). According to Schumpeter’s innovation theory, within a unified complex system, the essence of technological innovation forms from the unity of positive and negative feedback and the oneness of opposites such as “revolutionary” and “destructive.” Even a tiny technological impact can cause drastic consequences. The impact of AI on employment is different from the that of previous industrial revolutions, and it is exceptional in that “machines” are no longer straightforward mechanical tools but have assumed more of a “worker” role, just as people who can learn and think tend to do (Boyd and Holton 2018 ). AI-related technologies continue to advance, the industrialization and commercialization process continues to accelerate, and the industry continues to explore the application of AI across multiple fields. Since AI was first proposed at the Dartmouth Conference in 1956, discussions about “AI replacing human labor” and “AI defeating humans” have endlessly emerged. This dynamic has increased in intensity since the emergence of ChatGPT, which has aroused people’s concerns about technology replacing the workforce. Summarizing the literature, we can find three main arguments concerning the relationship between AI and employment:

First, AI has the effect of creating and filling jobs. The intelligent manufacturing industry paradigm characterized by AI technology will assist in forming a high-quality “human‒machine cooperation” employment mode. In an enlightened society, the social state of shared prosperity benefits the lowest class of people precisely because of the advanced productive forces and higher labour efficiency created through the refinement of the division of labour. By improving production efficiency, reducing the sales price of final products, and stimulating social consumption, technological progress exerts both price effects and income effects, which in turn drive related enterprises to expand their production scale, which, in turn, increases the demand for labour (Li et al. 2021 ; Ndubuisi et al. 2021 ; Yang 2022 ; Sharma and Mishra 2023 ; Li et al. 2022 ). People habitually regard robots as competitors for human beings, but this view only represents the materialistic view of traditional machinery. The coexistence of man and machine is not a zero-sum game. When the task evolves from “cooperation for all” to “cooperation between man and machine,” it results in fewer production constraints and maximizes total factor productivity, thus creating more jobs and generating novel collaborative tasks (Balsmeier and Woerter 2019 ; Duan et al. 2023 ). At the same time, materialized AI technology can improve the total factor production efficiency in ways that are suitable for its factor endowment structure and improve the production efficiency between upstream and downstream enterprises in the industrial chain and the value chain. This increase in the efficiency of the entire market will subsequently drive the expansion of the production scale of enterprises and promote reproduction, and its synergy will promote the synchronous growth of the labour demand involving various skills, thus resulting in a creative effect (Liu et al. 2022 ). As an essential force in the fourth industrial revolution, AI inevitably affects the social status of humans and changes the structure of the labour force (Chen 2023 ). AI and machines increase labour productivity by automating routine tasks while expanding employee skills and increasing the value of work. As a result, in a machine-for-machine employment model, low-skilled jobs will disappear, while new and currently unrealized job roles will emerge (Polak 2021 ). We can even argue that digital technology, artificial intelligence, and robot encounters are helping to train skilled robots and raise their relative wages (Yoon 2023 ).