The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

The Advantages and Limitations of Single Case Study Analysis

As Andrew Bennett and Colin Elman have recently noted, qualitative research methods presently enjoy “an almost unprecedented popularity and vitality… in the international relations sub-field”, such that they are now “indisputably prominent, if not pre-eminent” (2010: 499). This is, they suggest, due in no small part to the considerable advantages that case study methods in particular have to offer in studying the “complex and relatively unstructured and infrequent phenomena that lie at the heart of the subfield” (Bennett and Elman, 2007: 171). Using selected examples from within the International Relations literature[1], this paper aims to provide a brief overview of the main principles and distinctive advantages and limitations of single case study analysis. Divided into three inter-related sections, the paper therefore begins by first identifying the underlying principles that serve to constitute the case study as a particular research strategy, noting the somewhat contested nature of the approach in ontological, epistemological, and methodological terms. The second part then looks to the principal single case study types and their associated advantages, including those from within the recent ‘third generation’ of qualitative International Relations (IR) research. The final section of the paper then discusses the most commonly articulated limitations of single case studies; while accepting their susceptibility to criticism, it is however suggested that such weaknesses are somewhat exaggerated. The paper concludes that single case study analysis has a great deal to offer as a means of both understanding and explaining contemporary international relations.

The term ‘case study’, John Gerring has suggested, is “a definitional morass… Evidently, researchers have many different things in mind when they talk about case study research” (2006a: 17). It is possible, however, to distil some of the more commonly-agreed principles. One of the most prominent advocates of case study research, Robert Yin (2009: 14) defines it as “an empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident”. What this definition usefully captures is that case studies are intended – unlike more superficial and generalising methods – to provide a level of detail and understanding, similar to the ethnographer Clifford Geertz’s (1973) notion of ‘thick description’, that allows for the thorough analysis of the complex and particularistic nature of distinct phenomena. Another frequently cited proponent of the approach, Robert Stake, notes that as a form of research the case study “is defined by interest in an individual case, not by the methods of inquiry used”, and that “the object of study is a specific, unique, bounded system” (2008: 443, 445). As such, three key points can be derived from this – respectively concerning issues of ontology, epistemology, and methodology – that are central to the principles of single case study research.

First, the vital notion of ‘boundedness’ when it comes to the particular unit of analysis means that defining principles should incorporate both the synchronic (spatial) and diachronic (temporal) elements of any so-called ‘case’. As Gerring puts it, a case study should be “an intensive study of a single unit… a spatially bounded phenomenon – e.g. a nation-state, revolution, political party, election, or person – observed at a single point in time or over some delimited period of time” (2004: 342). It is important to note, however, that – whereas Gerring refers to a single unit of analysis – it may be that attention also necessarily be given to particular sub-units. This points to the important difference between what Yin refers to as an ‘holistic’ case design, with a single unit of analysis, and an ’embedded’ case design with multiple units of analysis (Yin, 2009: 50-52). The former, for example, would examine only the overall nature of an international organization, whereas the latter would also look to specific departments, programmes, or policies etc.

Secondly, as Tim May notes of the case study approach, “even the most fervent advocates acknowledge that the term has entered into understandings with little specification or discussion of purpose and process” (2011: 220). One of the principal reasons for this, he argues, is the relationship between the use of case studies in social research and the differing epistemological traditions – positivist, interpretivist, and others – within which it has been utilised. Philosophy of science concerns are obviously a complex issue, and beyond the scope of much of this paper. That said, the issue of how it is that we know what we know – of whether or not a single independent reality exists of which we as researchers can seek to provide explanation – does lead us to an important distinction to be made between so-called idiographic and nomothetic case studies (Gerring, 2006b). The former refers to those which purport to explain only a single case, are concerned with particularisation, and hence are typically (although not exclusively) associated with more interpretivist approaches. The latter are those focused studies that reflect upon a larger population and are more concerned with generalisation, as is often so with more positivist approaches[2]. The importance of this distinction, and its relation to the advantages and limitations of single case study analysis, is returned to below.

Thirdly, in methodological terms, given that the case study has often been seen as more of an interpretivist and idiographic tool, it has also been associated with a distinctly qualitative approach (Bryman, 2009: 67-68). However, as Yin notes, case studies can – like all forms of social science research – be exploratory, descriptive, and/or explanatory in nature. It is “a common misconception”, he notes, “that the various research methods should be arrayed hierarchically… many social scientists still deeply believe that case studies are only appropriate for the exploratory phase of an investigation” (Yin, 2009: 6). If case studies can reliably perform any or all three of these roles – and given that their in-depth approach may also require multiple sources of data and the within-case triangulation of methods – then it becomes readily apparent that they should not be limited to only one research paradigm. Exploratory and descriptive studies usually tend toward the qualitative and inductive, whereas explanatory studies are more often quantitative and deductive (David and Sutton, 2011: 165-166). As such, the association of case study analysis with a qualitative approach is a “methodological affinity, not a definitional requirement” (Gerring, 2006a: 36). It is perhaps better to think of case studies as transparadigmatic; it is mistaken to assume single case study analysis to adhere exclusively to a qualitative methodology (or an interpretivist epistemology) even if it – or rather, practitioners of it – may be so inclined. By extension, this also implies that single case study analysis therefore remains an option for a multitude of IR theories and issue areas; it is how this can be put to researchers’ advantage that is the subject of the next section.

Having elucidated the defining principles of the single case study approach, the paper now turns to an overview of its main benefits. As noted above, a lack of consensus still exists within the wider social science literature on the principles and purposes – and by extension the advantages and limitations – of case study research. Given that this paper is directed towards the particular sub-field of International Relations, it suggests Bennett and Elman’s (2010) more discipline-specific understanding of contemporary case study methods as an analytical framework. It begins however, by discussing Harry Eckstein’s seminal (1975) contribution to the potential advantages of the case study approach within the wider social sciences.

Eckstein proposed a taxonomy which usefully identified what he considered to be the five most relevant types of case study. Firstly were so-called configurative-idiographic studies, distinctly interpretivist in orientation and predicated on the assumption that “one cannot attain prediction and control in the natural science sense, but only understanding ( verstehen )… subjective values and modes of cognition are crucial” (1975: 132). Eckstein’s own sceptical view was that any interpreter ‘simply’ considers a body of observations that are not self-explanatory and “without hard rules of interpretation, may discern in them any number of patterns that are more or less equally plausible” (1975: 134). Those of a more post-modernist bent, of course – sharing an “incredulity towards meta-narratives”, in Lyotard’s (1994: xxiv) evocative phrase – would instead suggest that this more free-form approach actually be advantageous in delving into the subtleties and particularities of individual cases.

Eckstein’s four other types of case study, meanwhile, promote a more nomothetic (and positivist) usage. As described, disciplined-configurative studies were essentially about the use of pre-existing general theories, with a case acting “passively, in the main, as a receptacle for putting theories to work” (Eckstein, 1975: 136). As opposed to the opportunity this presented primarily for theory application, Eckstein identified heuristic case studies as explicit theoretical stimulants – thus having instead the intended advantage of theory-building. So-called p lausibility probes entailed preliminary attempts to determine whether initial hypotheses should be considered sound enough to warrant more rigorous and extensive testing. Finally, and perhaps most notably, Eckstein then outlined the idea of crucial case studies , within which he also included the idea of ‘most-likely’ and ‘least-likely’ cases; the essential characteristic of crucial cases being their specific theory-testing function.

Whilst Eckstein’s was an early contribution to refining the case study approach, Yin’s (2009: 47-52) more recent delineation of possible single case designs similarly assigns them roles in the applying, testing, or building of theory, as well as in the study of unique cases[3]. As a subset of the latter, however, Jack Levy (2008) notes that the advantages of idiographic cases are actually twofold. Firstly, as inductive/descriptive cases – akin to Eckstein’s configurative-idiographic cases – whereby they are highly descriptive, lacking in an explicit theoretical framework and therefore taking the form of “total history”. Secondly, they can operate as theory-guided case studies, but ones that seek only to explain or interpret a single historical episode rather than generalise beyond the case. Not only does this therefore incorporate ‘single-outcome’ studies concerned with establishing causal inference (Gerring, 2006b), it also provides room for the more postmodern approaches within IR theory, such as discourse analysis, that may have developed a distinct methodology but do not seek traditional social scientific forms of explanation.

Applying specifically to the state of the field in contemporary IR, Bennett and Elman identify a ‘third generation’ of mainstream qualitative scholars – rooted in a pragmatic scientific realist epistemology and advocating a pluralistic approach to methodology – that have, over the last fifteen years, “revised or added to essentially every aspect of traditional case study research methods” (2010: 502). They identify ‘process tracing’ as having emerged from this as a central method of within-case analysis. As Bennett and Checkel observe, this carries the advantage of offering a methodologically rigorous “analysis of evidence on processes, sequences, and conjunctures of events within a case, for the purposes of either developing or testing hypotheses about causal mechanisms that might causally explain the case” (2012: 10).

Harnessing various methods, process tracing may entail the inductive use of evidence from within a case to develop explanatory hypotheses, and deductive examination of the observable implications of hypothesised causal mechanisms to test their explanatory capability[4]. It involves providing not only a coherent explanation of the key sequential steps in a hypothesised process, but also sensitivity to alternative explanations as well as potential biases in the available evidence (Bennett and Elman 2010: 503-504). John Owen (1994), for example, demonstrates the advantages of process tracing in analysing whether the causal factors underpinning democratic peace theory are – as liberalism suggests – not epiphenomenal, but variously normative, institutional, or some given combination of the two or other unexplained mechanism inherent to liberal states. Within-case process tracing has also been identified as advantageous in addressing the complexity of path-dependent explanations and critical junctures – as for example with the development of political regime types – and their constituent elements of causal possibility, contingency, closure, and constraint (Bennett and Elman, 2006b).

Bennett and Elman (2010: 505-506) also identify the advantages of single case studies that are implicitly comparative: deviant, most-likely, least-likely, and crucial cases. Of these, so-called deviant cases are those whose outcome does not fit with prior theoretical expectations or wider empirical patterns – again, the use of inductive process tracing has the advantage of potentially generating new hypotheses from these, either particular to that individual case or potentially generalisable to a broader population. A classic example here is that of post-independence India as an outlier to the standard modernisation theory of democratisation, which holds that higher levels of socio-economic development are typically required for the transition to, and consolidation of, democratic rule (Lipset, 1959; Diamond, 1992). Absent these factors, MacMillan’s single case study analysis (2008) suggests the particularistic importance of the British colonial heritage, the ideology and leadership of the Indian National Congress, and the size and heterogeneity of the federal state.

Most-likely cases, as per Eckstein above, are those in which a theory is to be considered likely to provide a good explanation if it is to have any application at all, whereas least-likely cases are ‘tough test’ ones in which the posited theory is unlikely to provide good explanation (Bennett and Elman, 2010: 505). Levy (2008) neatly refers to the inferential logic of the least-likely case as the ‘Sinatra inference’ – if a theory can make it here, it can make it anywhere. Conversely, if a theory cannot pass a most-likely case, it is seriously impugned. Single case analysis can therefore be valuable for the testing of theoretical propositions, provided that predictions are relatively precise and measurement error is low (Levy, 2008: 12-13). As Gerring rightly observes of this potential for falsification:

“a positivist orientation toward the work of social science militates toward a greater appreciation of the case study format, not a denigration of that format, as is usually supposed” (Gerring, 2007: 247, emphasis added).

In summary, the various forms of single case study analysis can – through the application of multiple qualitative and/or quantitative research methods – provide a nuanced, empirically-rich, holistic account of specific phenomena. This may be particularly appropriate for those phenomena that are simply less amenable to more superficial measures and tests (or indeed any substantive form of quantification) as well as those for which our reasons for understanding and/or explaining them are irreducibly subjective – as, for example, with many of the normative and ethical issues associated with the practice of international relations. From various epistemological and analytical standpoints, single case study analysis can incorporate both idiographic sui generis cases and, where the potential for generalisation may exist, nomothetic case studies suitable for the testing and building of causal hypotheses. Finally, it should not be ignored that a signal advantage of the case study – with particular relevance to international relations – also exists at a more practical rather than theoretical level. This is, as Eckstein noted, “that it is economical for all resources: money, manpower, time, effort… especially important, of course, if studies are inherently costly, as they are if units are complex collective individuals ” (1975: 149-150, emphasis added).

Limitations

Single case study analysis has, however, been subject to a number of criticisms, the most common of which concern the inter-related issues of methodological rigour, researcher subjectivity, and external validity. With regard to the first point, the prototypical view here is that of Zeev Maoz (2002: 164-165), who suggests that “the use of the case study absolves the author from any kind of methodological considerations. Case studies have become in many cases a synonym for freeform research where anything goes”. The absence of systematic procedures for case study research is something that Yin (2009: 14-15) sees as traditionally the greatest concern due to a relative absence of methodological guidelines. As the previous section suggests, this critique seems somewhat unfair; many contemporary case study practitioners – and representing various strands of IR theory – have increasingly sought to clarify and develop their methodological techniques and epistemological grounding (Bennett and Elman, 2010: 499-500).

A second issue, again also incorporating issues of construct validity, concerns that of the reliability and replicability of various forms of single case study analysis. This is usually tied to a broader critique of qualitative research methods as a whole. However, whereas the latter obviously tend toward an explicitly-acknowledged interpretive basis for meanings, reasons, and understandings:

“quantitative measures appear objective, but only so long as we don’t ask questions about where and how the data were produced… pure objectivity is not a meaningful concept if the goal is to measure intangibles [as] these concepts only exist because we can interpret them” (Berg and Lune, 2010: 340).

The question of researcher subjectivity is a valid one, and it may be intended only as a methodological critique of what are obviously less formalised and researcher-independent methods (Verschuren, 2003). Owen (1994) and Layne’s (1994) contradictory process tracing results of interdemocratic war-avoidance during the Anglo-American crisis of 1861 to 1863 – from liberal and realist standpoints respectively – are a useful example. However, it does also rest on certain assumptions that can raise deeper and potentially irreconcilable ontological and epistemological issues. There are, regardless, plenty such as Bent Flyvbjerg (2006: 237) who suggest that the case study contains no greater bias toward verification than other methods of inquiry, and that “on the contrary, experience indicates that the case study contains a greater bias toward falsification of preconceived notions than toward verification”.

The third and arguably most prominent critique of single case study analysis is the issue of external validity or generalisability. How is it that one case can reliably offer anything beyond the particular? “We always do better (or, in the extreme, no worse) with more observation as the basis of our generalization”, as King et al write; “in all social science research and all prediction, it is important that we be as explicit as possible about the degree of uncertainty that accompanies out prediction” (1994: 212). This is an unavoidably valid criticism. It may be that theories which pass a single crucial case study test, for example, require rare antecedent conditions and therefore actually have little explanatory range. These conditions may emerge more clearly, as Van Evera (1997: 51-54) notes, from large-N studies in which cases that lack them present themselves as outliers exhibiting a theory’s cause but without its predicted outcome. As with the case of Indian democratisation above, it would logically be preferable to conduct large-N analysis beforehand to identify that state’s non-representative nature in relation to the broader population.

There are, however, three important qualifiers to the argument about generalisation that deserve particular mention here. The first is that with regard to an idiographic single-outcome case study, as Eckstein notes, the criticism is “mitigated by the fact that its capability to do so [is] never claimed by its exponents; in fact it is often explicitly repudiated” (1975: 134). Criticism of generalisability is of little relevance when the intention is one of particularisation. A second qualifier relates to the difference between statistical and analytical generalisation; single case studies are clearly less appropriate for the former but arguably retain significant utility for the latter – the difference also between explanatory and exploratory, or theory-testing and theory-building, as discussed above. As Gerring puts it, “theory confirmation/disconfirmation is not the case study’s strong suit” (2004: 350). A third qualification relates to the issue of case selection. As Seawright and Gerring (2008) note, the generalisability of case studies can be increased by the strategic selection of cases. Representative or random samples may not be the most appropriate, given that they may not provide the richest insight (or indeed, that a random and unknown deviant case may appear). Instead, and properly used , atypical or extreme cases “often reveal more information because they activate more actors… and more basic mechanisms in the situation studied” (Flyvbjerg, 2006). Of course, this also points to the very serious limitation, as hinted at with the case of India above, that poor case selection may alternatively lead to overgeneralisation and/or grievous misunderstandings of the relationship between variables or processes (Bennett and Elman, 2006a: 460-463).

As Tim May (2011: 226) notes, “the goal for many proponents of case studies […] is to overcome dichotomies between generalizing and particularizing, quantitative and qualitative, deductive and inductive techniques”. Research aims should drive methodological choices, rather than narrow and dogmatic preconceived approaches. As demonstrated above, there are various advantages to both idiographic and nomothetic single case study analyses – notably the empirically-rich, context-specific, holistic accounts that they have to offer, and their contribution to theory-building and, to a lesser extent, that of theory-testing. Furthermore, while they do possess clear limitations, any research method involves necessary trade-offs; the inherent weaknesses of any one method, however, can potentially be offset by situating them within a broader, pluralistic mixed-method research strategy. Whether or not single case studies are used in this fashion, they clearly have a great deal to offer.

References

Bennett, A. and Checkel, J. T. (2012) ‘Process Tracing: From Philosophical Roots to Best Practice’, Simons Papers in Security and Development, No. 21/2012, School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University: Vancouver.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2006a) ‘Qualitative Research: Recent Developments in Case Study Methods’, Annual Review of Political Science , 9, 455-476.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2006b) ‘Complex Causal Relations and Case Study Methods: The Example of Path Dependence’, Political Analysis , 14, 3, 250-267.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2007) ‘Case Study Methods in the International Relations Subfield’, Comparative Political Studies , 40, 2, 170-195.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2010) Case Study Methods. In C. Reus-Smit and D. Snidal (eds) The Oxford Handbook of International Relations . Oxford University Press: Oxford. Ch. 29.

Berg, B. and Lune, H. (2012) Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences . Pearson: London.

Bryman, A. (2012) Social Research Methods . Oxford University Press: Oxford.

David, M. and Sutton, C. D. (2011) Social Research: An Introduction . SAGE Publications Ltd: London.

Diamond, J. (1992) ‘Economic development and democracy reconsidered’, American Behavioral Scientist , 35, 4/5, 450-499.

Eckstein, H. (1975) Case Study and Theory in Political Science. In R. Gomm, M. Hammersley, and P. Foster (eds) Case Study Method . SAGE Publications Ltd: London.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006) ‘Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research’, Qualitative Inquiry , 12, 2, 219-245.

Geertz, C. (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays by Clifford Geertz . Basic Books Inc: New York.

Gerring, J. (2004) ‘What is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?’, American Political Science Review , 98, 2, 341-354.

Gerring, J. (2006a) Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Gerring, J. (2006b) ‘Single-Outcome Studies: A Methodological Primer’, International Sociology , 21, 5, 707-734.

Gerring, J. (2007) ‘Is There a (Viable) Crucial-Case Method?’, Comparative Political Studies , 40, 3, 231-253.

King, G., Keohane, R. O. and Verba, S. (1994) Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research . Princeton University Press: Chichester.

Layne, C. (1994) ‘Kant or Cant: The Myth of the Democratic Peace’, International Security , 19, 2, 5-49.

Levy, J. S. (2008) ‘Case Studies: Types, Designs, and Logics of Inference’, Conflict Management and Peace Science , 25, 1-18.

Lipset, S. M. (1959) ‘Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy’, The American Political Science Review , 53, 1, 69-105.

Lyotard, J-F. (1984) The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge . University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis.

MacMillan, A. (2008) ‘Deviant Democratization in India’, Democratization , 15, 4, 733-749.

Maoz, Z. (2002) Case study methodology in international studies: from storytelling to hypothesis testing. In F. P. Harvey and M. Brecher (eds) Evaluating Methodology in International Studies . University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor.

May, T. (2011) Social Research: Issues, Methods and Process . Open University Press: Maidenhead.

Owen, J. M. (1994) ‘How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace’, International Security , 19, 2, 87-125.

Seawright, J. and Gerring, J. (2008) ‘Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options’, Political Research Quarterly , 61, 2, 294-308.

Stake, R. E. (2008) Qualitative Case Studies. In N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (eds) Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry . Sage Publications: Los Angeles. Ch. 17.

Van Evera, S. (1997) Guide to Methods for Students of Political Science . Cornell University Press: Ithaca.

Verschuren, P. J. M. (2003) ‘Case study as a research strategy: some ambiguities and opportunities’, International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 6, 2, 121-139.

Yin, R. K. (2009) Case Study Research: Design and Methods . SAGE Publications Ltd: London.

[1] The paper follows convention by differentiating between ‘International Relations’ as the academic discipline and ‘international relations’ as the subject of study.

[2] There is some similarity here with Stake’s (2008: 445-447) notion of intrinsic cases, those undertaken for a better understanding of the particular case, and instrumental ones that provide insight for the purposes of a wider external interest.

[3] These may be unique in the idiographic sense, or in nomothetic terms as an exception to the generalising suppositions of either probabilistic or deterministic theories (as per deviant cases, below).

[4] Although there are “philosophical hurdles to mount”, according to Bennett and Checkel, there exists no a priori reason as to why process tracing (as typically grounded in scientific realism) is fundamentally incompatible with various strands of positivism or interpretivism (2012: 18-19). By extension, it can therefore be incorporated by a range of contemporary mainstream IR theories.

— Written by: Ben Willis Written at: University of Plymouth Written for: David Brockington Date written: January 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Identity in International Conflicts: A Case Study of the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Imperialism’s Legacy in the Study of Contemporary Politics: The Case of Hegemonic Stability Theory

- Recreating a Nation’s Identity Through Symbolism: A Chinese Case Study

- Ontological Insecurity: A Case Study on Israeli-Palestinian Conflict in Jerusalem

- Terrorists or Freedom Fighters: A Case Study of ETA

- A Critical Assessment of Eco-Marxism: A Ghanaian Case Study

Please Consider Donating

Before you download your free e-book, please consider donating to support open access publishing.

E-IR is an independent non-profit publisher run by an all volunteer team. Your donations allow us to invest in new open access titles and pay our bandwidth bills to ensure we keep our existing titles free to view. Any amount, in any currency, is appreciated. Many thanks!

Donations are voluntary and not required to download the e-book - your link to download is below.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Research Guides

Multiple Case Studies

Nadia Alqahtani and Pengtong Qu

Description

The case study approach is popular across disciplines in education, anthropology, sociology, psychology, medicine, law, and political science (Creswell, 2013). It is both a research method and a strategy (Creswell, 2013; Yin, 2017). In this type of research design, a case can be an individual, an event, or an entity, as determined by the research questions. There are two variants of the case study: the single-case study and the multiple-case study. The former design can be used to study and understand an unusual case, a critical case, a longitudinal case, or a revelatory case. On the other hand, a multiple-case study includes two or more cases or replications across the cases to investigate the same phenomena (Lewis-Beck, Bryman & Liao, 2003; Yin, 2017). …a multiple-case study includes two or more cases or replications across the cases to investigate the same phenomena

The difference between the single- and multiple-case study is the research design; however, they are within the same methodological framework (Yin, 2017). Multiple cases are selected so that “individual case studies either (a) predict similar results (a literal replication) or (b) predict contrasting results but for anticipatable reasons (a theoretical replication)” (p. 55). When the purpose of the study is to compare and replicate the findings, the multiple-case study produces more compelling evidence so that the study is considered more robust than the single-case study (Yin, 2017).

To write a multiple-case study, a summary of individual cases should be reported, and researchers need to draw cross-case conclusions and form a cross-case report (Yin, 2017). With evidence from multiple cases, researchers may have generalizable findings and develop theories (Lewis-Beck, Bryman & Liao, 2003).

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Lewis-Beck, M., Bryman, A. E., & Liao, T. F. (2003). The Sage encyclopedia of social science research methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Key Research Books and Articles on Multiple Case Study Methodology

Yin discusses how to decide if a case study should be used in research. Novice researchers can learn about research design, data collection, and data analysis of different types of case studies, as well as writing a case study report.

Chapter 2 introduces four major types of research design in case studies: holistic single-case design, embedded single-case design, holistic multiple-case design, and embedded multiple-case design. Novice researchers will learn about the definitions and characteristics of different designs. This chapter also teaches researchers how to examine and discuss the reliability and validity of the designs.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

This book compares five different qualitative research designs: narrative research, phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and case study. It compares the characteristics, data collection, data analysis and representation, validity, and writing-up procedures among five inquiry approaches using texts with tables. For each approach, the author introduced the definition, features, types, and procedures and contextualized these components in a study, which was conducted through the same method. Each chapter ends with a list of relevant readings of each inquiry approach.

This book invites readers to compare these five qualitative methods and see the value of each approach. Readers can consider which approach would serve for their research contexts and questions, as well as how to design their research and conduct the data analysis based on their choice of research method.

Günes, E., & Bahçivan, E. (2016). A multiple case study of preservice science teachers’ TPACK: Embedded in a comprehensive belief system. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11 (15), 8040-8054.

In this article, the researchers showed the importance of using technological opportunities in improving the education process and how they enhanced the students’ learning in science education. The study examined the connection between “Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge” (TPACK) and belief system in a science teaching context. The researchers used the multiple-case study to explore the effect of TPACK on the preservice science teachers’ (PST) beliefs on their TPACK level. The participants were three teachers with the low, medium, and high level of TPACK confidence. Content analysis was utilized to analyze the data, which were collected by individual semi-structured interviews with the participants about their lesson plans. The study first discussed each case, then compared features and relations across cases. The researchers found that there was a positive relationship between PST’s TPACK confidence and TPACK level; when PST had higher TPACK confidence, the participant had a higher competent TPACK level and vice versa.

Recent Dissertations Using Multiple Case Study Methodology

Milholland, E. S. (2015). A multiple case study of instructors utilizing Classroom Response Systems (CRS) to achieve pedagogical goals . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3706380)

The researcher of this study critiques the use of Classroom Responses Systems by five instructors who employed this program five years ago in their classrooms. The researcher conducted the multiple-case study methodology and categorized themes. He interviewed each instructor with questions about their initial pedagogical goals, the changes in pedagogy during teaching, and the teaching techniques individuals used while practicing the CRS. The researcher used the multiple-case study with five instructors. He found that all instructors changed their goals during employing CRS; they decided to reduce the time of lecturing and to spend more time engaging students in interactive activities. This study also demonstrated that CRS was useful for the instructors to achieve multiple learning goals; all the instructors provided examples of the positive aspect of implementing CRS in their classrooms.

Li, C. L. (2010). The emergence of fairy tale literacy: A multiple case study on promoting critical literacy of children through a juxtaposed reading of classic fairy tales and their contemporary disruptive variants . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3572104)

To explore how children’s development of critical literacy can be impacted by their reactions to fairy tales, the author conducted a multiple-case study with 4 cases, in which each child was a unit of analysis. Two Chinese immigrant children (a boy and a girl) and two American children (a boy and a girl) at the second or third grade were recruited in the study. The data were collected through interviews, discussions on fairy tales, and drawing pictures. The analysis was conducted within both individual cases and cross cases. Across four cases, the researcher found that the young children’s’ knowledge of traditional fairy tales was built upon mass-media based adaptations. The children believed that the representations on mass-media were the original stories, even though fairy tales are included in the elementary school curriculum. The author also found that introducing classic versions of fairy tales increased children’s knowledge in the genre’s origin, which would benefit their understanding of the genre. She argued that introducing fairy tales can be the first step to promote children’s development of critical literacy.

Asher, K. C. (2014). Mediating occupational socialization and occupational individuation in teacher education: A multiple case study of five elementary pre-service student teachers . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3671989)

This study portrayed five pre-service teachers’ teaching experience in their student teaching phase and explored how pre-service teachers mediate their occupational socialization with occupational individuation. The study used the multiple-case study design and recruited five pre-service teachers from a Midwestern university as five cases. Qualitative data were collected through interviews, classroom observations, and field notes. The author implemented the case study analysis and found five strategies that the participants used to mediate occupational socialization with occupational individuation. These strategies were: 1) hindering from practicing their beliefs, 2) mimicking the styles of supervising teachers, 3) teaching in the ways in alignment with school’s existing practice, 4) enacting their own ideas, and 5) integrating and balancing occupational socialization and occupational individuation. The study also provided recommendations and implications to policymakers and educators in teacher education so that pre-service teachers can be better supported.

Multiple Case Studies Copyright © 2019 by Nadia Alqahtani and Pengtong Qu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Holism in Psychology: Definition and Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Holism is often referred to as Gestalt psychology . It argues that behavior cannot be understood in terms of the components that make them up. This is commonly described as ‘the whole being greater than the sum of its parts.’

In other words, human behavior has its own properties that are not explicable in terms of the properties of the elements from which it is derived.

A holistic approach, therefore, suggests that there are different levels of explanation and that at each level, there are “emergent properties” that cannot be reduced to the one below.

Holistic approaches include Humanism, Social, and Gestalt psychology and make use of the case study method. Jahoda’s six elements of Optimal Living are an example of a holistic approach to defining abnormality.

Reductionist explanations, which might work in some circumstances, are considered inappropriate to the study of human subjectivity because here, the emergent property that we have to take account of is that of the “whole person.”

Otherwise, it makes no sense to try to understand the meaning of anything that anybody might do.

Holism in Psychology

In psychology, holism refers to an approach or perspective that emphasizes the importance of studying and understanding the whole person or system rather than focusing solely on its individual parts or components.

It suggests that individuals should be viewed as integrated and complex beings, with various interconnected aspects that influence their thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and overall functioning.

Holism in psychology recognizes that human beings are not simply the sum of their individual traits, but rather they are influenced by multiple factors that interact with one another.

These factors may include biological, psychological, social, cultural, and environmental aspects. Holistic psychologists aim to understand how these elements interact and shape an individual’s experiences and behaviors.

The holistic perspective emphasizes the interconnectedness of various dimensions of human functioning. For example, it acknowledges that individual thoughts and emotions do not solely determine psychological well-being but can also be influenced by social relationships, cultural context, physical health, and environmental factors.

Holistic approaches in psychology often strive to consider the whole person in assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. This can involve considering the person’s background, beliefs, values, relationships, and broader social and environmental factors contributing to their well-being or challenges.

By adopting a holistic perspective, psychologists aim to gain a comprehensive understanding of individuals and their experiences, considering both internal and external factors.

This approach recognizes the complexity of human beings and the need to address multiple dimensions for a more complete understanding and effective intervention.

Humanism investigates all aspects of the individual and the interactions between people.

It emerged as a reaction against those dehumanizing psychological perspectives that attempted to reduce behavior to a set of simple elements.

Humanistic, or third force psychologists, feel that holism is the only valid approach to the complete understanding of mind and behavior. They reject reductionism in all its forms.

Their starting point is the self (our sense of personal identity) which they consider a functioning whole. In Carl Rogers’s words, it is an “organized, consistent set of perceptions and beliefs about oneself.”

It includes an awareness of the person I am and could be. It directs our behavior in all the consciously chosen aspects of our lives and is fundamentally motivated towards achieving self-actualization .

For humanists, then, the self is the most essential and unique quality of human beings. It is what makes us what we are and is the basis of the difference between psychology and all-natural science.

Humanistic psychology investigates all aspects of the individual and the interactions between people.

Reductionist explanations undermine the indivisible unity of experience. They run counter to and ultimately destroy the very object of psychological inquiry. A holistic point of view is, thus, in humanist terms, the very basis of all knowledge of the human psyche .

Social Psychology

Social psychology looks at the behavior of individuals in a social context. Group behavior (e.g., conformity, de-individualization) may show characteristics greater than the sum of the individuals comprising it.

Psychoanalysis

Freud adopted an interactionist approach in that he considered that behavior resulted from a dynamic interaction between the id, ego, and superego .

Abnormal psychology

This is where the brain understands and interprets sensory information . Visual illusions show that humans perceive more than the sum of the sensations on the retina.

- Looks at everything that may impact behavior.

- Does not ignore the complexity of behavior.

- Integrates different components of behavior in order to understand the person as a whole.

- Can be higher in ecological validity.

Limitations

- Overcomplicates behaviors that may have simpler explanations (Occam’s Razor).

- Does not lend itself to the scientific method and empirical testing.

- Makes it hard to determine cause and effect.

- Neglects the importance of biological explanations.

- Almost impossible to study all the factors that influence complex human behaviors

Keep Learning

- Freeman J. Towards a definition of holism. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(511):154–155.

- Michaelson V, Pickett W, King N, Davison C. (2016) Testing the theory of holism: A study of family systems and adolescent health. Prev Med Rep, 4, 313–319.

Related Articles

Social Science

Hard Determinism: Philosophy & Examples (Does Free Will Exist?)

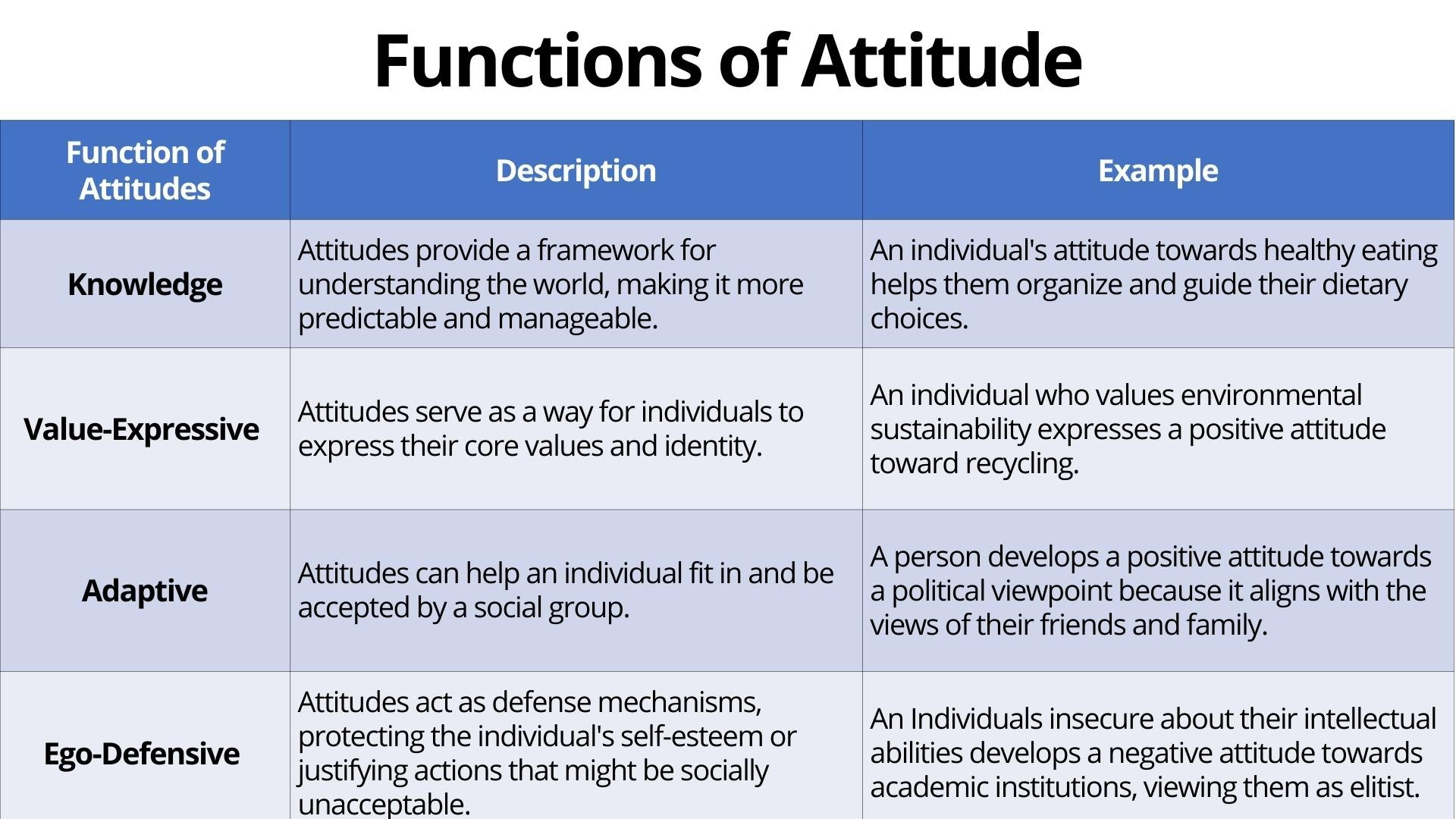

Functions of Attitude Theory

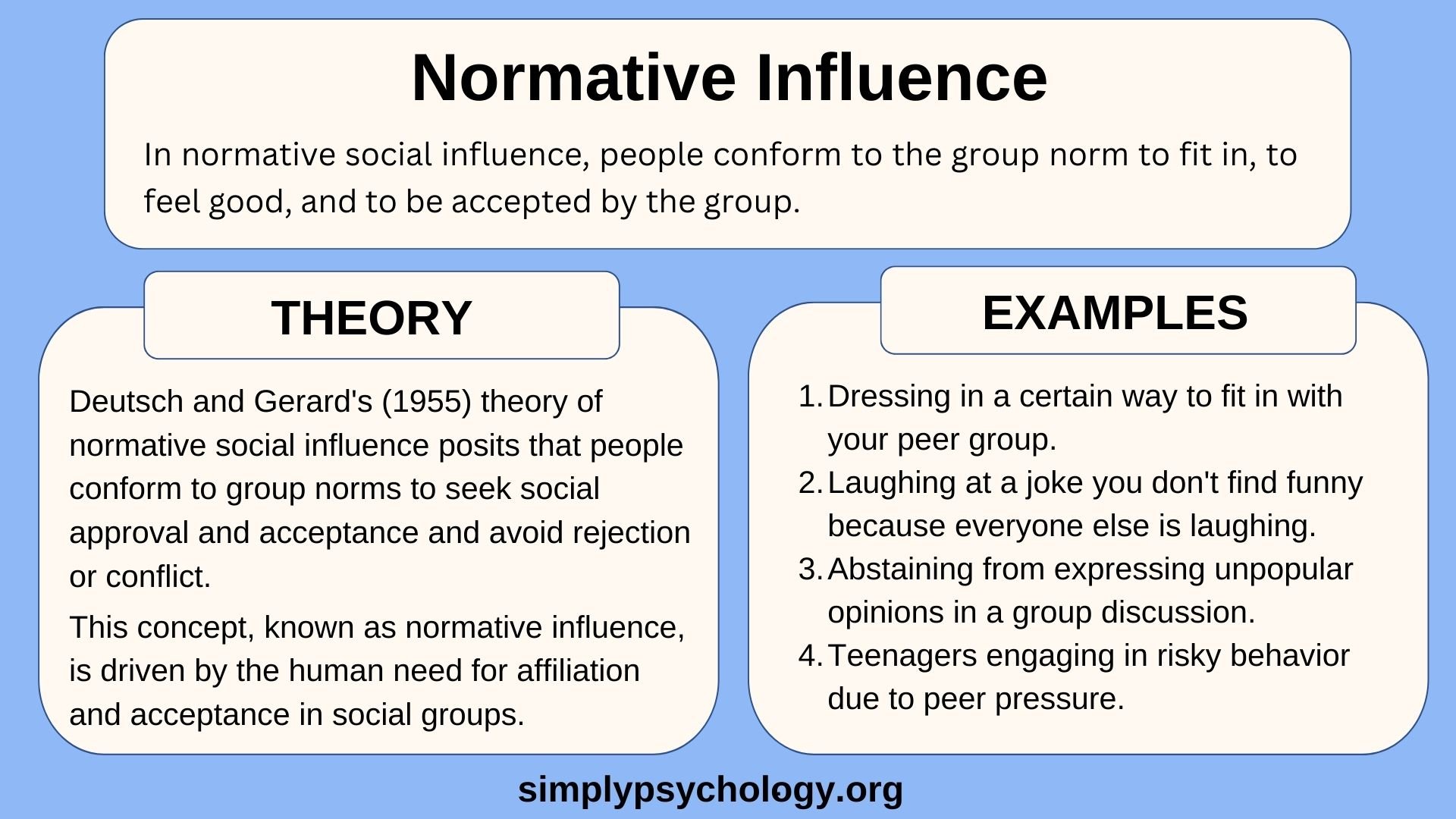

Understanding Conformity: Normative vs. Informational Social Influence

Social Control Theory of Crime

Emotions , Mood , Social Science

Emotional Labor: Definition, Examples, Types, and Consequences

Famous Experiments , Social Science

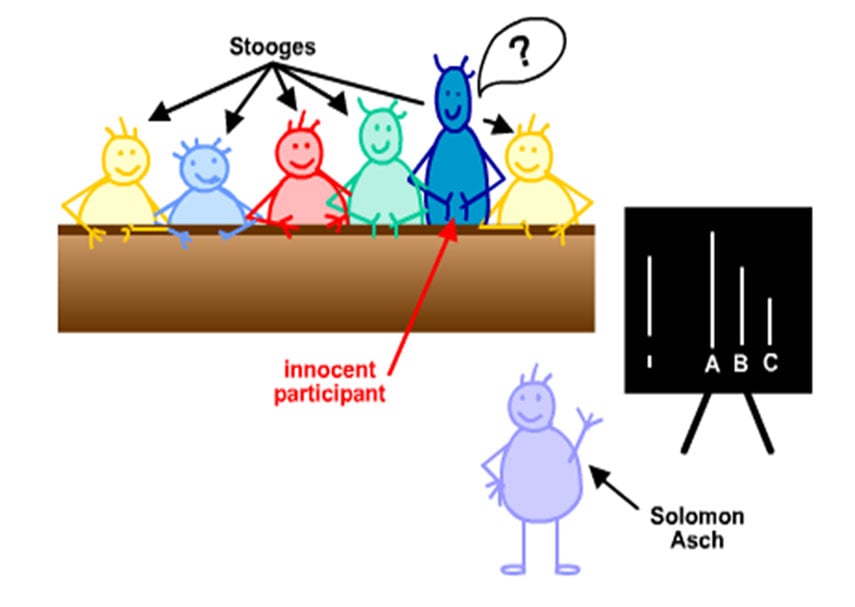

Solomon Asch Conformity Line Experiment Study

The Impact of WeFuture’s ‘Challenge Your World’ Workshop in Amsterdam | Case Study

Holistic thinking: what it is, why it’s important, and how to do it.

- Holistic Thinking

- World Conservation

We humans like to simplify things. And that's a good thing, to begin with, because this characteristic protects us from too many stimuli, excessive demands and overload. We develop routines that help us cope with everyday life without having to expend a lot of thought and energy. We build a microcosm around ourselves, focusing on people and things in our immediate environment. We know our family and friends, our city and our work so well that we think we know how life works.

Sometimes, however, we find that things are not as simple as we would like to believe. Namely, when we encounter complex problems. Abruptly, we tend to realize that our individual view of the world can be one-sided. For example, we can feel quite uncomfortable when we realize that climate change is a real threat. Here, our microcosm with its usual solution patterns suddenly reaches its limits. We are faced with a problem that seems so complex and abstract that it can (and often does) make us feel overwhelmed.

But in this, there is creative power. In chaos lies the chance of creativity. Why? Because it forces us to step back from familiar perceptions. Because it allows us to see that our ‘individual’ world, to which we devote all our attention, is only a part of reality. And we see that we, as individuals, are a part of the whole of nature in its beauty. Changing our perspective from the individual details to the whole forms the basis for a way of thinking that aims to help solve problems in a more cohesive way: Holistic thinking.

What Is Holistic Thinking?

Holistic thinking means having a holistic approach by contemplating the bigger picture. "Holistic“ derives from the Greek word "holos", which stands for "whole" and "comprehensive". "Holistic" therefore, means "wholeness."

Aristotle, the famous Greek philosopher, has a quote that provides a great description of how the holistic way of thinking works: "The whole is more than the sum of its parts." To help explain the impact of this quote, let’s break the process down using a simple example:

- Collect all of the ‘parts’ of something - eg. building blocks.

- Sum them up by adding them together, ordering, and arranging them in a way that makes sense - eg. build up walls, create windows, and doors.

- After summing up the parts, we create a whole. - eg. a house

- However, the ‘whole’ (or in this case, the house) is more than that because we get more value and understanding through the ‘summing’ process. By adding these parts up together, we may now better understand: - Physical structures eg. the best way to build walls so they are insulated. - Scientific principles eg. balancing the weight of the house so gravity won't tear it down. - Human Impact eg. Once we move into the house, it becomes a home. We now have shelter, security, and an increased likelihood of survival.

By summing these parts, we have received so much more - the intangible assets like understanding, value, and meaning - about the whole that was not available to its parts alone. The holistic approach leads us to truly appreciate and comprehend the sum of parts, thus making it "more than".

How is Holistic Thinking Applied?

Holistic thinking can be applied to many systems; such as biological, social, mental, economic or spiritual systems.

It is a way of thinking that has been practiced by many indigenous people for many, many years - especially when it comes to health and wellness (an example of biological, mental, and spiritual systems). Whatsmore, some traditional health care systems that are rooted in holistic principles, such as the Ancient Indian Ayurveda and Amazonian Shamanism, are still practiced today!

One of the famous personalities associated with a holistic vision was Leonardo Da Vinci, the well-known Italian painter of the Mona Lisa, living in the Renaissance. He is admired by the world for his multidisciplinary approach to connecting logic and creativity. His holistic perspective of knowledge gathering was based on thinking beyond limits and resulted in iconic creative expression that has stood the test of time.

Holism was also the core of the worldview of another famous individual - Alexander von Humboldt, German naturalist and explorer. He didn’t see organisms, geological structures, weather phenomena, or human activities as detached; but as interacting entities of a larger complex system. He shaped the scientific perception of how everything is connected. Both Da Vinci and von Humboldt showed with their interdisciplinary approach how existing ideas and new concepts complement each other.

From ancient practices to famous personalities, the application and outcomes of holistic thinking is timeless. And this is most likely because this way of thinking stems from something bigger; Holism.

The Significance of Holism

“Holism (noun): the idea that the whole of something must be considered in order to understand its different parts” - Oxford Advanced American Dictionary

While clearly defined by man, Holism is by no means a thought construct of man. Nature exemplifies and dictates holism to us; every part needs the whole and the whole needs every part. Balance, cooperation, symbiosis and synergy defines life. From animate and inanimate nature to ecosystems, physiology of organisms to climate or social interactions - every single piece of a system affects the others and the whole.

This complexity becomes particularly clear when we consider the big challenges of today. The major challenges humanity is facing are on a global scale. If we look at climate change, for example, we often think of industry and mobility. The fires in the Amazon rainforest? The (majorly illegal) deforestation of the rainforest for the cultivation of palm oil or soy and loss of biodiversity? Corruption, the displacement of the local population or conflicts with indigenous groups? All of these aspects are also defined as climate change.

It’s not possible to break the world down into its components. Whether it is climate change, mass poverty or mass extinction – there are no simple solutions to global crises. Holistic thinking makes us realise the complexity of all of the issues we face. It aims to help us to identify different perspectives and needs. Furthermore, it helps us to develop and create long-term solutions for these global challenges. Creativity, interdisciplinarity, participation and collaboration are important prerequisites to try to achieve this.

The United Nations established a plan of action for sustainable development, known as the 2030 Agenda , and is an example of a holistic approach to multilateral sustainability policy. The agenda is based on the three dimensions model of sustainability: economy, society and the environment, which are interrelated. The Agenda is broken down into Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) , which are considered universal and apply equally to all countries when striving for a balance between the three dimensions.

Holistic thinking is the prerequisite to the 2030 Agenda and is a necessary consequence of the cooperation between all countries working towards the SDGs. It’s the key to tackling our global challenges.

WeFuture Global’s guide to holistic thinking

Many people have learned to solve a problem where it appears visibly and tangibly for everyone. While this approach may well lead to initial successes – these are not long-lasting, since the core of the problem is often hidden at first glance.

For example, In order to contribute to the fight against climate change by reducing carbon emissions, it makes sense to use the bicycle more often than a car. But, if we really want to make a difference, we should look further than just at one piece of the puzzle and adopt a holistic approach. This can be done in many ways, such as questioning our own consumption in all areas of life (not just with personal transportation), taking a look at the sustainable practices implemented on other sides of the globe, and increasing the pressure on businesses and politicians to implement sustainable practices, to name a few.