The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

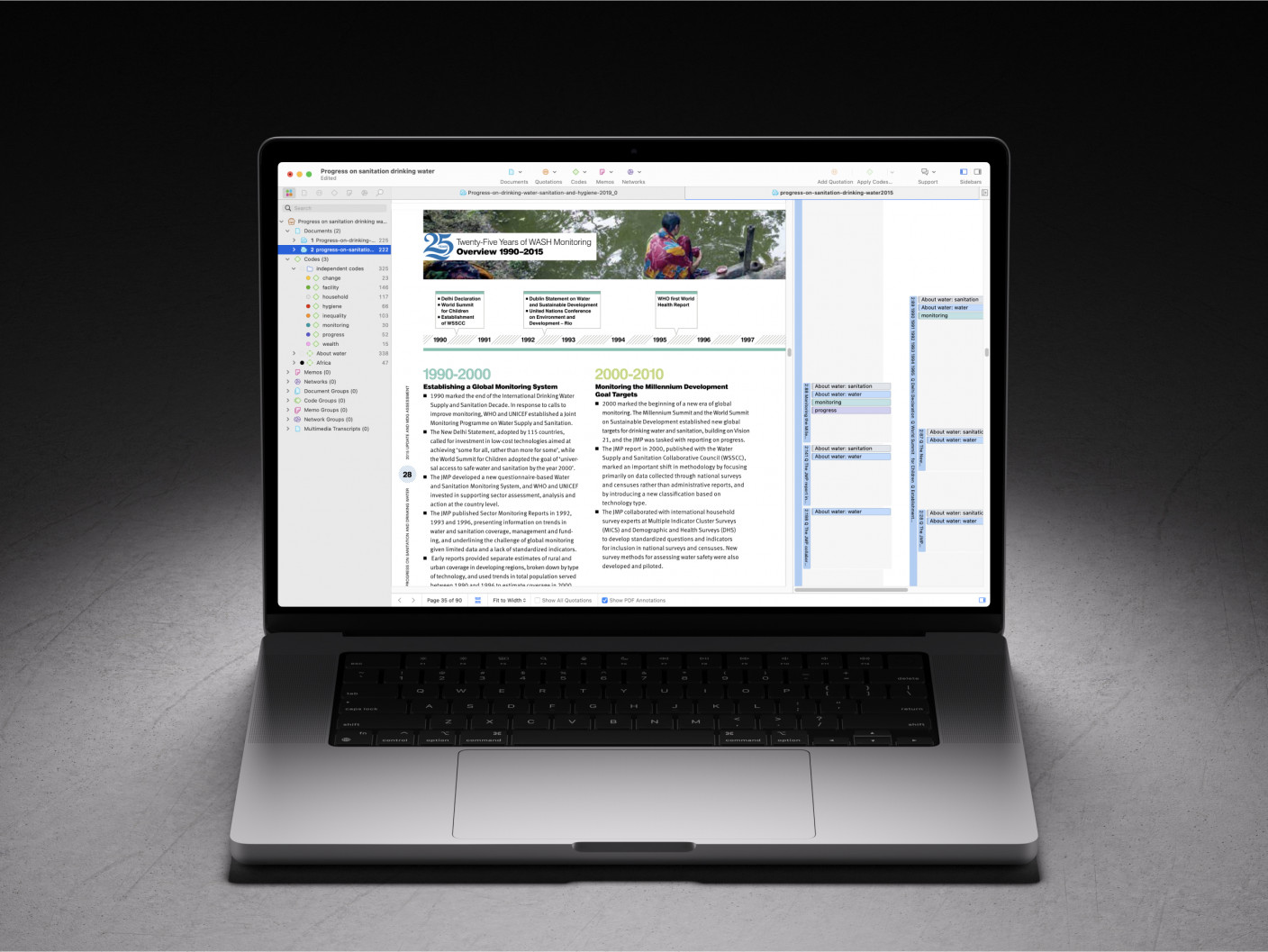

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

Site Search

- How to Search

- Advisory Group

- Editorial Board

- OEC Fellows

- History and Funding

- Using OEC Materials

- Collections

- Research Ethics Resources

- Ethics Projects

- Communities of Practice

- Get Involved

- Submit Content

- Open Access Membership

- Become a Partner

Using Case Studies in Teaching Research Ethics

An essay exploring how to effectively use case studies to teach research ethics.

It is widely believed that discussing case studies is the most effective method of teaching the responsible conduct of research (Kovac 1996; Macrina and Munro 1995), probably because discussing case studies is an effective way to get students involved in the issues. (I use the word “student” to cover all those who study, including faculty members and other professionals.)

Case studies are stories, Some of the many forms case studies can take are described in the Appendix. and narrative – the telling of stories – is a fundamental human tool for organizing, understanding, and explaining experience. Alasdair MacIntyre offers an amusing example of how one might make sense of a nonsensical event by embedding it into a story.

I am standing waiting for a bus and the young man standing next to me suddenly says, ‘The name of the common wild duck is Histrionicus histrionicus histrionicus.’ There is no problem as to the meaning of the sentence he uttered; the problem is, how to answer the question, what was he doing in uttering it? Suppose he just uttered such sentences at random intervals; this would be one possible form of madness. We would render his act of utterance intelligible if one of the following turned out to be true: He has mistaken me for someone who yesterday had approached him in the library and asked: ‘Do you by any chance know the Latin name of the common wild duck?’ Or he has just come from a session with his psychotherapist who has urged him to break down his shyness by talking to strangers. ‘But what shall I say?’ ‘Oh, anything at all.’ Or he is a Soviet spy waiting at a prearranged rendez-vous and uttering the ill-chosen code sentence which will identify him to his contact. In each case the act of utterance becomes intelligible by finding its place in a narrative. [MacIntyre 1981:195-196, italics in original] The young man is mistaken, by the way. Ducks belong to the family Anatidae, not Histrionicus.

Just as unintelligible actions invite us to put them into a story, stories invite us to interpret them. Stories imply causality, intention, and meaning; in the forms of parables, fables, and allegories, stories are favored vehicles for moral and religious instruction worldwide.

An in-depth discussion of a case is the closest approximation to actually confronting an ethical problem that can easily be set up in a classroom. Experience is the best teacher, but we can’t predict whether or when our students will face an actual ethical conflict in research, and we would not want to wish such an experience on them. Although a good case discussion is not the same as dealing with a real ethical problem, it can be an approximation of such an experience, just as watching a film about the decline and death of an aged friend can be a highly affecting approximation of the actual experience. Watching the film The Dresser can bring a person to real tears; discussing a case can bring a student to genuine ethical development.

The value of case study discussion can be illustrated with an anecdote. In the first year of the Teaching Research Ethics Workshop, we might have spent a bit too much time talking about using case studies and how to lead case study discussions. By Wednesday (the workshop began on a Sunday that year), one participant complained, saying something like, “Aren’t you going to talk about anything but cases? I’ve used them and students get bored with them.”

We spent less time on case studies thereafter, but I mention the incident because of an evaluation we did in the third year of the workshop. We hired an external evaluator to talk to past workshop participants about its impact on them. I asked our evaluator to talk to several specific participants, including the one who had complained about case studies. To my complete surprise, the report showed that this participant “identified mastery of the case study approach as having had the greatest direct impact” on his teaching. The other past participants interviewed made similar comments.

Like all teaching techniques, case study discussion can be done well or poorly, and I hope to provide some guidance to help you avoid the worst pitfalls. I will assume that you already know how to lead a discussion and limit my comments to considerations pertaining directly to using case studies in research ethics. My comments are rooted in what has worked for me with the assumption that most of it will work for you, too – but probably not all of it. Teaching is an art, and success depends a great deal on the skills and personality of the teacher.

Much of what follows might sound dogmatic, but that should be taken as a stylistic quirk. I could add all the hedges and exceptions of which I can think, but that would only muddy things. Use your own judgment and take the advice for what it’s worth. Also note that this is general advice; some cases are designed to be used in a particular way (see Bebeau et al. 1995).

Preparing to lead a case study discussion is much the same as preparing to teach anything – figure out what you want to accomplish, how much time you can spend on it, and the like.

In the classroom, start by laying out ground rules. In many settings this step does not have to be overt – if it is a group you have been meeting with already, and you have established a tone of respect and openness, there’s no need to go over this again. If the group has not established this kind of rapport, then it is important to make it clear that everyone’s opinion will be heard – and challenged – respectfully.

You might also want to offer your students some strategies and tactics before plunging into the discussion.

Strategies cover the broad direction for the discussion. For example, you can tell your students that you want them to:

- Decide which of two positions to defend – “Should Peterson copy the notes? Why or why not?”

- Solve a problem – “What should Peterson do?”

- Take a role – “What would you do if you were Peterson?” • Think about how the problem could have been avoided – “What went wrong here?”

Clearly these are not mutually exclusive, and there are probably other strategies you could use.

It is often also helpful to suggest some tactics . Sometimes students see a case study (or ethics) as an inchoate mass – or as too well integrated to analyze. It can be useful to give them some specific things to dig out of the case.

For example, in Moral Reasoning in Scientific Research: Cases for Teaching and Assessment , which I developed along with Mickey Bebeau, Karen Muskavitch, and several other colleagues (Bebeau et al. 1995), we suggest that students try to identify (a) the ethical issues and points of conflict, (b) the interested parties, (c) the likely consequences of the proposed course of action, and (d) the moral obligations of the protagonist.

Lucinda Peach (included in Penslar 1995) offers a different approach, suggesting the value of paying attention to six factors: facts; interpretations of the facts; consequences; obligations; rights; and virtues (or character). I have found it particularly helpful to point out the distinction between the facts presented in the case and the interpretations of facts that are sometimes made unconsciously.

When the time comes to start the actual discussion, I always distribute a copy of the case study to all students, and I often also display it using an overhead projector. If a case is at all complex or subtle, or has more than one or two characters, it is very difficult to take part in the discussion without having the case on hand for reference.

I usually ask one or more students to volunteer to read the case aloud . If there are several characters in the case, I often take the part of narrator and ask students to read the parts of the characters. Reading the case aloud ensures that everyone finishes at the same time; asking students to take part gets their voices heard early.

Then I give students a chance to ask any questions of factual clarification they might have. The answers might already be in the case, but they aren’t always. I don’t always answer all of these questions at this point, saying instead, “Let’s make sure we get to that when we discuss the case.” For example, if a student were to ask: “What kind of student is Peterson? Is she any good?” I would want to wait until the discussion period, when I would respond by asking, “What difference does it make?” (Not to imply that it doesn’t make a difference, but to see why the students think it does.)

I often then give students a few minutes to write some thoughts – perhaps to answer the strategic question, or identify the tactical elements I had already outlined. I usually don’t collect the papers; I do collect the papers when I use Moral Reasoning in Scientific Research; it’s part of the method outlined in the booklet. the object here is to give students a chance to collect their thoughts and make a commitment, however tentative, to a few of them. Ideas that remain only half-formed in the mind often fly away when the discussion begins, but the written ideas are there for the students’ reference.

If the group isn’t too large, I find it very useful to go around the room and ask every student to make one short response to the case. When the strategy is to defend a position, I first ask them each to answer the first question – “Should Peterson copy the notes?” – yes or no. I tally their answers on the board. Then I go around again and ask each student to offer one reason for their answer. (If the responses are unbalanced – say 10 yes and 2 no – I give the students who said “no” the chance to state their case first.) In larger groups, I get a random sample of responses.

Then I plunge into the discussion, trying to be as quiet as I can and to get the students to talk as much as possible. My part is to keep things orderly, to clarify points in the case (including relevant rules and regulations), and to gently direct the discussion toward profitable paths. I usually write main points on the board.

Finally, the case should be brought to some kind of closure . Sometimes this means describing what I take to be the areas of agreement and disagreement and the relative weight of each (“Almost everyone agrees on X, but we’re still pretty divided on Y”). Sometimes it even includes a pronouncement: “It would be wrong for Peterson to copy the notes.” But I would generally qualify the pronouncement by describing some of Peterson’s other options.

Case study discussion can work even if you use it only once, but the more often a group discusses cases, the better. Using case studies is not the only technique for teaching responsible science, but it is, I think, one of the best.

Works Cited

Barnbaum, Deborah R., and Michael Byron. 2001. Research Ethics: Text and Readings . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bebeau, Muriel J., et al. 1995. Moral Reasoning in Scientific Research : Cases for Teaching and Assessment. Bloomington, IN.: Poynter Center. http://poynter.indiana.edu/mr-main.shtml

Elliott, Deni, and Judy E. Stern, eds. 1997. Research Ethics: A Reader . Hanover, CT: University Press of New England.

Harris, Charles E. Jr., Michael S. Pritchard, and Michael J. Rabins. 1995. Engineering Ethics: Concepts and Cases . Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

King, Nancy M. P., Gail E. Henderson, and Jane Stein, eds. 1999. Beyond Regulations: Ethics in Human Subjects Research . Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Kovac, Jeffrey. 1996. “Scientific ethics in chemical education.” Journal of Chemical Education 73(10): 926-928.

MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1981. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory . Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Macrina, Francis L. 2000. Scientific Integrity: An Introductory Text with Cases . 2nd ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press.

Macrina, Francis L. and Cindy L. Munro. 1995. “The case-study approach to teaching scientific integrity in nursing and the biomedical sciences.” Journal of Professional Nursing 11(1): 40- 44.

Orlans, F. Barbara, et al. 1998. The Human Use of Animals: Case Studies in Ethical Choice . New York: Oxford University Press. Penslar, Robin Levin. 1995. Research Ethics: Cases and Materials. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Seebauer, Edmund G., and Robert L. Barry. 2001. Fundamentals of Ethics for Scientists and Engineers . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schrag, Brian, ed. 1997-2002. Research Ethics: Cases and Commentaries . Six volumes. Bloomington, IN: Association for Practical and Professional Ethics.

Appendix: Types of case studies

I don’t know of any thorough typology of case studies, but it is clear that case studies take many forms. Here are some of the forms that I have come across. The list is not intended to be exhaustive, and the descriptive names are my own – they should not be construed as definitive or in common use.

Illustrative cases are perhaps the most common form. They are included in textbooks written specifically for instruction in the responsible conduct of research and are generally found at the end of each chapter to illustrate the chapter’s major points. For examples, see Barnbaum and Byron 2001; Elliott and Stern 1997; Harris, Pritchard, and Rabins 1995; Macrina 2000; and Seebauer and Barry 2001.

Historical case studies start with a particular controversy, event, or series of related events. Good examples can be found in The Human Use of Animals (Orlans et al. 1998). The first case, “Baboon-human liver transplants: The Pittsburgh case,” describes an operation performed in 1992 at the University of Pittsburgh to replace a dying man’s defective liver with a healthy liver from a baboon. The case itself is presented in two pages, followed by about a page of historical context. The bulk of the chapter, about eight pages, consists of commentary on the ethical issues raised by the case. (See also King et.al 1999.) Historical cases are good because they are real, not made up, and students cannot dismiss them by saying, “That would never happen.” On the other hand, though, some students will view historical cases as settled and over with; the very fact that they have been written up can seem to imply that the issues raised have all be solved.

Historical synopses are shorter, often focusing on a well-known event. Fundamentals of Ethics for Scientists and Engineers (Seebauer and Barry 2001), for example, includes sixteen “real-life cases,” generally one or two pages long with a few questions for discussion. The first three cases are titled “Destruction of the Spaceship Challenger,” “Toxic Waste at Love Canal,” and “Dow Corning Corp. and Breast Implants.”

Journalistic case studies are historical case studies written by journalists for mass consumption. A recent example, “The Stuttering Doctor’s ‘Monster Study’,” can be found in the New York Times Magazine (Reynolds 2003). It is the story of Wendell Johnson’s research in the late 1930’s that involved inducing stuttering in orphans. Journalistic accounts generally are written in a more literary, less academic style – they are often more passionate and viscerally engaging than case studies prepared by philosophers and ethicists.

Cases with commentary present the case study first and then follow it with one or more commentaries. The six-volume series Research Ethics: Cases and Commentaries (Schrag 1996- 2002) presents a short case (about two-four pages) followed by a commentary by the case’s author and a second commentary by another expert. (See also King et.al 1999.)

Dramatic cases are formatted like a script, which allows the characters’ voices to carry most of the story. I find them very good for conveying subtleties.

Trigger tapes are short videos intended to trigger discussion. Among the best available are the five videos in the series “Integrity in Scientific Research” (see http://www.aaas.org/spp/video/ ).

Finally, a series of casuistic cases presents several very short, related cases, each one in some way a variation or elaboration of one or more of the previous cases in the series. The first one or two cases are generally straightforward, presenting, for example, a clear-cut case of cheating and a clear-cut case of acceptable sharing of information. Later cases are less straightforward, pushing the boundaries that make the earlier cases clear-cut. Excellent examples can be found in Penslar 1995 (see, e.g., Chapters 5 and 6). This book also includes examples of many of the other kinds of case studies described here.

Portions of this paper are adapted from a presentation at the Planning Workshop for a Guide for Teaching Responsible Science, sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health, February 1997.

Copyright 2003, 2007, Kenneth D. Pimple, Ph.D. All rights reserved.

Permission is hereby granted to reproduce and distribute copies of this work for nonprofit educational purposes, provided that copies are distributed at or below cost, and that the author, source, and copyright notice are included on each copy. This permission is in addition to rights of reproduction granted under Sections 107, 108, and other provisions of the U.S. Copyright Act.

Also available at the TeachRCR.us site.

Related Resources

Submit Content to the OEC Donate

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. 2055332. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 58 animated videos - 1 to 2 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Curated Resources UT Star Icon

Professional Ethics

Professionals work in a wide variety of settings and across many different industries including business, science, medicine, education, art, and public service.

Many professions have Codes of Conduct that specify ethical behavior and expectations particular to that industry. In addition, professionals must make ethical judgments in their area of specialty that fall outside their specific Code of Conduct.

The resources in this section offer insights that apply to a wide range of professionals as they seek to develop standards of ethical decision-making and behavior in their careers. Often, professionals need to apply moral reasoning to their interactions with co-workers, clients, and the general public to solve problems that arise in their work. Professionals also need to be on lookout for social and organizational pressures and situational factors that could cause them to err, unknowingly, in their ethical judgments and actions.

No profession is free from ethical dilemmas. All professionals will face ethical issues regardless of their career trajectory or the role they play within an organization. While Codes of Conduct are essential, and a good starting point for ethical conduct, they are no substitute for a well-rounded education in behavioral and applied ethics.

Start Here: Videos

Role Morality

Role morality is the tendency we have to use different moral standards for the different roles we play in society.

Bounded Ethicality

Bounded ethicality explains how social pressures and psychological processes cause us to behave in ways that are inconsistent with our own values.

Being Your Best Self, Part 4: Moral Action

Moral action means transforming the intent to do the right thing into reality. This involves moral ownership, moral efficacy, and moral courage.

Start Here: Cases

Freedom vs. Duty in Clinical Social Work

What should social workers do when their personal values come in conflict with the clients they are meant to serve?

High Stakes Testing

In the wake of the No Child Left Behind Act, parents, teachers, and school administrators take different positions on how to assess student achievement.

Healthcare Obligations: Personal vs. Institutional

A medical doctor must make a difficult decision when informing patients of the effectiveness of flu shots while upholding institutional recommendations.

Teaching Notes

Begin by viewing the “Start Here” videos. They introduce key topics that commonly emerge in our careers, such as making ethical decisions based on the role we’re playing at work. The four-part video, Being Your Best Self , describes the four components of ethical decision-making and action. To help strengthen ethical decision-making skills, watch the behavioral ethics videos in the “Additional Videos” section to learn about the psychological biases that can often lead to making poor choices.

Read through these videos’ teaching notes for details and related ethics concepts. Watch the “Related Videos” and/or read the related Case Study. The video’s “Additional Resources” offer further reading and a bibliography.

To use these resources in the classroom, show a video in class, assign a video to watch outside of class, or embed a video in an online learning module such as Canvas. Then, prompt conversation in class to encourage peer-to-peer learning. Ask students to answer the video’s “Discussion Questions,” and to reflect on the ideas and issues raised by the students in the video. How do their experiences align? How do they differ? The videos also make good writing prompts. Ask students to watch a video and apply the ethics concept to course content.

The case studies offer examples of professionals facing tough ethical decisions or ethically questionable situations in their careers in teaching, science, politics, and social services. Cases are an effective way to introduce ethics topics, and for people to learn how to spot ethical issues.

Select a case study from the Cases Series or find one in the “Additional Cases” section that resonates with your industry or profession. Then, reason through the ethical dimensions presented, and sketch the ethical decision-making process outlined by the case. Challenge yourself (and/or your team at work) to develop strategies to avoid these ethical pitfalls. Watch the case study’s “Related Videos” and “Related Terms” for further understanding.

To use the case studies in the classroom, ask students to read a video’s “Case Study” and answer the case study “Discussion Questions.” Then, follow the strategy outlined in the previous paragraph, challenging students to develop strategies to avoid the ethical pitfalls presented in the case.

Ethics Unwrapped blogs are also useful prompts to engage colleagues or students in discussions about ethics. Learning about ethics in the context of real-world (often current) events can enliven conversation and make ethics relevant and concrete. Share a blog in a meeting or class or post one to the company intranet or the class’s online learning module. To spur discussion, try to identify the ethical issues at hand and to name the ethics concepts related to the blog (or current event in the news). Dig more deeply into the topic using the Additional Resources listed at the end of the blog post.

Remember to review video, case study, and blogs’ relevant glossary terms. In this way, you will become familiar with all the ethics concepts contained in these material. Share this vocabulary with your colleagues or students, and use it to expand and enrich ethics and leadership conversations. To dive deeper in the glossary, watch “Related” glossary videos.

Many of the concepts covered in Ethics Unwrapped operate in tandem with each other. As you watch more videos, you will become more fluent in ethics and see the interrelatedness of ethics concepts more readily. You also will be able to spot ethical issues more easily – at least, that is the hope! It will also be easier to express your ideas and thoughts about what is and isn’t ethical and why. Hopefully, you will also come to realize the interconnectedness of ethics and leadership, and the essential role ethics plays in developing solid leadership skills that can advance your professional career.

Additional Videos

- Self-serving Bias

- Moral Equilibrium

- Conflict of Interest

- In It To Win: The Jack Abramoff Story

- In It To Win: Jack & Framing

- In It To Win: Jack & Rationalizations

- In It To Win: Jack & Self-Serving Bias

- In It To Win: Jack & Role Morality

- In It To Win: Jack & Moral Equilibrium

- Intro to GVV

- GVV Pillar 1: Values

- GVV Pillar 2: Choice

- GVV Pillar 3: Normalization

- GVV Pillar 4: Purpose

- GVV Pillar 5: Self-Knowledge & Alignment

- GVV Pillar 6: Voice

- GVV Pillar 7: Reasons & Rationalizations

- Obedience to Authority

- Loss Aversion

- Intro to Behavioral Ethics

- Moral Muteness

- Moral Myopia

- Being Your Best Self, Part 1: Moral Awareness

- Being Your Best Self, Part 2: Moral Decision Making

- Being Your Best Self, Part 3: Moral Intent

- Legal Rights & Ethical Responsibilities

Additional Cases

Liberal arts & fine arts.

- A Million Little Pieces

- Approaching the Presidency: Roosevelt & Taft

- Pardoning Nixon

Science & Engineering

- Retracting Research: The Case of Chandok v. Klessig

- Arctic Offshore Drilling

Social Science

- The CIA Leak

- Edward Snowden: Traitor or Hero?

- The Costco Model

- The Collapse of Barings Bank

- Teaching Blackface: A Lesson on Stereotypes

- Cyber Harassment

- Cheating: Atlanta’s School Scandal

Communication & Journalism

- Dr. V’s Magical Putter

- Limbaugh on Drug Addiction

- Reporting on Robin Williams

- Covering Yourself? Journalists and the Bowl Championship

- Sports Blogs: The Wild West of Sports Journalism?

- Cheney v. U.S. District Court

- Negotiating Bankruptcy

- Patient Autonomy & Informed Consent

- Prenatal Diagnosis & Parental Choice

Public Policy & Administration

- Gaming the System: The VA Scandal

- Krogh & the Watergate Scandal

Stay Informed

Support our work.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations in research refer to the principles and guidelines that researchers must follow to ensure that their studies are conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. These considerations are designed to protect the rights, safety, and well-being of research participants, as well as the integrity and credibility of the research itself

Some of the key ethical considerations in research include:

- Informed consent: Researchers must obtain informed consent from study participants, which means they must inform participants about the study’s purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and their right to withdraw at any time.

- Privacy and confidentiality : Researchers must ensure that participants’ privacy and confidentiality are protected. This means that personal information should be kept confidential and not shared without the participant’s consent.

- Harm reduction : Researchers must ensure that the study does not harm the participants physically or psychologically. They must take steps to minimize the risks associated with the study.

- Fairness and equity : Researchers must ensure that the study does not discriminate against any particular group or individual. They should treat all participants equally and fairly.

- Use of deception: Researchers must use deception only if it is necessary to achieve the study’s objectives. They must inform participants of the deception as soon as possible.

- Use of vulnerable populations : Researchers must be especially cautious when working with vulnerable populations, such as children, pregnant women, prisoners, and individuals with cognitive or intellectual disabilities.

- Conflict of interest : Researchers must disclose any potential conflicts of interest that may affect the study’s integrity. This includes financial or personal relationships that could influence the study’s results.

- Data manipulation: Researchers must not manipulate data to support a particular hypothesis or agenda. They should report the results of the study objectively, even if the findings are not consistent with their expectations.

- Intellectual property: Researchers must respect intellectual property rights and give credit to previous studies and research.

- Cultural sensitivity : Researchers must be sensitive to the cultural norms and beliefs of the participants. They should avoid imposing their values and beliefs on the participants and should be respectful of their cultural practices.

Types of Ethical Considerations

Types of Ethical Considerations are as follows:

Research Ethics:

This includes ethical principles and guidelines that govern research involving human or animal subjects, ensuring that the research is conducted in an ethical and responsible manner.

Business Ethics :

This refers to ethical principles and standards that guide business practices and decision-making, such as transparency, honesty, fairness, and social responsibility.

Medical Ethics :

This refers to ethical principles and standards that govern the practice of medicine, including the duty to protect patient autonomy, informed consent, confidentiality, and non-maleficence.

Environmental Ethics :

This involves ethical principles and values that guide our interactions with the natural world, including the obligation to protect the environment, minimize harm, and promote sustainability.

Legal Ethics

This involves ethical principles and standards that guide the conduct of legal professionals, including issues such as confidentiality, conflicts of interest, and professional competence.

Social Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that guide our interactions with other individuals and society as a whole, including issues such as justice, fairness, and human rights.

Information Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that govern the use and dissemination of information, including issues such as privacy, accuracy, and intellectual property.

Cultural Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that govern the relationship between different cultures and communities, including issues such as respect for diversity, cultural sensitivity, and inclusivity.

Technological Ethics

This refers to ethical principles and guidelines that govern the development, use, and impact of technology, including issues such as privacy, security, and social responsibility.

Journalism Ethics

This involves ethical principles and standards that guide the practice of journalism, including issues such as accuracy, fairness, and the public interest.

Educational Ethics

This refers to ethical principles and standards that guide the practice of education, including issues such as academic integrity, fairness, and respect for diversity.

Political Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that guide political decision-making and behavior, including issues such as accountability, transparency, and the protection of civil liberties.

Professional Ethics

This refers to ethical principles and standards that guide the conduct of professionals in various fields, including issues such as honesty, integrity, and competence.

Personal Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that guide individual behavior and decision-making, including issues such as personal responsibility, honesty, and respect for others.

Global Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that guide our interactions with other nations and the global community, including issues such as human rights, environmental protection, and social justice.

Applications of Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are important in many areas of society, including medicine, business, law, and technology. Here are some specific applications of ethical considerations:

- Medical research : Ethical considerations are crucial in medical research, particularly when human subjects are involved. Researchers must ensure that their studies are conducted in a way that does not harm participants and that participants give informed consent before participating.

- Business practices: Ethical considerations are also important in business, where companies must make decisions that are socially responsible and avoid activities that are harmful to society. For example, companies must ensure that their products are safe for consumers and that they do not engage in exploitative labor practices.

- Environmental protection: Ethical considerations play a crucial role in environmental protection, as companies and governments must weigh the benefits of economic development against the potential harm to the environment. Decisions about land use, resource allocation, and pollution must be made in an ethical manner that takes into account the long-term consequences for the planet and future generations.

- Technology development : As technology continues to advance rapidly, ethical considerations become increasingly important in areas such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and genetic engineering. Developers must ensure that their creations do not harm humans or the environment and that they are developed in a way that is fair and equitable.

- Legal system : The legal system relies on ethical considerations to ensure that justice is served and that individuals are treated fairly. Lawyers and judges must abide by ethical standards to maintain the integrity of the legal system and to protect the rights of all individuals involved.

Examples of Ethical Considerations

Here are a few examples of ethical considerations in different contexts:

- In healthcare : A doctor must ensure that they provide the best possible care to their patients and avoid causing them harm. They must respect the autonomy of their patients, and obtain informed consent before administering any treatment or procedure. They must also ensure that they maintain patient confidentiality and avoid any conflicts of interest.

- In the workplace: An employer must ensure that they treat their employees fairly and with respect, provide them with a safe working environment, and pay them a fair wage. They must also avoid any discrimination based on race, gender, religion, or any other characteristic protected by law.

- In the media : Journalists must ensure that they report the news accurately and without bias. They must respect the privacy of individuals and avoid causing harm or distress. They must also be transparent about their sources and avoid any conflicts of interest.

- In research: Researchers must ensure that they conduct their studies ethically and with integrity. They must obtain informed consent from participants, protect their privacy, and avoid any harm or discomfort. They must also ensure that their findings are reported accurately and without bias.

- In personal relationships : People must ensure that they treat others with respect and kindness, and avoid causing harm or distress. They must respect the autonomy of others and avoid any actions that would be considered unethical, such as lying or cheating. They must also respect the confidentiality of others and maintain their privacy.

How to Write Ethical Considerations

When writing about research involving human subjects or animals, it is essential to include ethical considerations to ensure that the study is conducted in a manner that is morally responsible and in accordance with professional standards. Here are some steps to help you write ethical considerations:

- Describe the ethical principles: Start by explaining the ethical principles that will guide the research. These could include principles such as respect for persons, beneficence, and justice.

- Discuss informed consent : Informed consent is a critical ethical consideration when conducting research. Explain how you will obtain informed consent from participants, including how you will explain the purpose of the study, potential risks and benefits, and how you will protect their privacy.

- Address confidentiality : Describe how you will protect the confidentiality of the participants’ personal information and data, including any measures you will take to ensure that the data is kept secure and confidential.

- Consider potential risks and benefits : Describe any potential risks or harms to participants that could result from the study and how you will minimize those risks. Also, discuss the potential benefits of the study, both to the participants and to society.

- Discuss the use of animals : If the research involves the use of animals, address the ethical considerations related to animal welfare. Explain how you will minimize any potential harm to the animals and ensure that they are treated ethically.

- Mention the ethical approval : Finally, it’s essential to acknowledge that the research has received ethical approval from the relevant institutional review board or ethics committee. State the name of the committee, the date of approval, and any specific conditions or requirements that were imposed.

When to Write Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations should be written whenever research involves human subjects or has the potential to impact human beings, animals, or the environment in some way. Ethical considerations are also important when research involves sensitive topics, such as mental health, sexuality, or religion.

In general, ethical considerations should be an integral part of any research project, regardless of the field or subject matter. This means that they should be considered at every stage of the research process, from the initial planning and design phase to data collection, analysis, and dissemination.

Ethical considerations should also be written in accordance with the guidelines and standards set by the relevant regulatory bodies and professional associations. These guidelines may vary depending on the discipline, so it is important to be familiar with the specific requirements of your field.

Purpose of Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are an essential aspect of many areas of life, including business, healthcare, research, and social interactions. The primary purposes of ethical considerations are:

- Protection of human rights: Ethical considerations help ensure that people’s rights are respected and protected. This includes respecting their autonomy, ensuring their privacy is respected, and ensuring that they are not subjected to harm or exploitation.

- Promoting fairness and justice: Ethical considerations help ensure that people are treated fairly and justly, without discrimination or bias. This includes ensuring that everyone has equal access to resources and opportunities, and that decisions are made based on merit rather than personal biases or prejudices.

- Promoting honesty and transparency : Ethical considerations help ensure that people are truthful and transparent in their actions and decisions. This includes being open and honest about conflicts of interest, disclosing potential risks, and communicating clearly with others.

- Maintaining public trust: Ethical considerations help maintain public trust in institutions and individuals. This is important for building and maintaining relationships with customers, patients, colleagues, and other stakeholders.

- Ensuring responsible conduct: Ethical considerations help ensure that people act responsibly and are accountable for their actions. This includes adhering to professional standards and codes of conduct, following laws and regulations, and avoiding behaviors that could harm others or damage the environment.

Advantages of Ethical Considerations

Here are some of the advantages of ethical considerations:

- Builds Trust : When individuals or organizations follow ethical considerations, it creates a sense of trust among stakeholders, including customers, clients, and employees. This trust can lead to stronger relationships and long-term loyalty.

- Reputation and Brand Image : Ethical considerations are often linked to a company’s brand image and reputation. By following ethical practices, a company can establish a positive image and reputation that can enhance its brand value.

- Avoids Legal Issues: Ethical considerations can help individuals and organizations avoid legal issues and penalties. By adhering to ethical principles, companies can reduce the risk of facing lawsuits, regulatory investigations, and fines.

- Increases Employee Retention and Motivation: Employees tend to be more satisfied and motivated when they work for an organization that values ethics. Companies that prioritize ethical considerations tend to have higher employee retention rates, leading to lower recruitment costs.

- Enhances Decision-making: Ethical considerations help individuals and organizations make better decisions. By considering the ethical implications of their actions, decision-makers can evaluate the potential consequences and choose the best course of action.

- Positive Impact on Society: Ethical considerations have a positive impact on society as a whole. By following ethical practices, companies can contribute to social and environmental causes, leading to a more sustainable and equitable society.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing...

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Thesis Format – Templates and Samples

Implications in Research – Types, Examples and...

Ethical Considerations In Psychology Research

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Ethics refers to the correct rules of conduct necessary when carrying out research. We have a moral responsibility to protect research participants from harm.

However important the issue under investigation, psychologists must remember that they have a duty to respect the rights and dignity of research participants. This means that they must abide by certain moral principles and rules of conduct.

What are Ethical Guidelines?

In Britain, ethical guidelines for research are published by the British Psychological Society, and in America, by the American Psychological Association. The purpose of these codes of conduct is to protect research participants, the reputation of psychology, and psychologists themselves.

Moral issues rarely yield a simple, unambiguous, right or wrong answer. It is, therefore, often a matter of judgment whether the research is justified or not.

For example, it might be that a study causes psychological or physical discomfort to participants; maybe they suffer pain or perhaps even come to serious harm.

On the other hand, the investigation could lead to discoveries that benefit the participants themselves or even have the potential to increase the sum of human happiness.

Rosenthal and Rosnow (1984) also discuss the potential costs of failing to carry out certain research. Who is to weigh up these costs and benefits? Who is to judge whether the ends justify the means?

Finally, if you are ever in doubt as to whether research is ethical or not, it is worthwhile remembering that if there is a conflict of interest between the participants and the researcher, it is the interests of the subjects that should take priority.

Studies must now undergo an extensive review by an institutional review board (US) or ethics committee (UK) before they are implemented. All UK research requires ethical approval by one or more of the following:

- Department Ethics Committee (DEC) : for most routine research.

- Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) : for non-routine research.

- External Ethics Committee (EEC) : for research that s externally regulated (e.g., NHS research).

Committees review proposals to assess if the potential benefits of the research are justifiable in light of the possible risk of physical or psychological harm.

These committees may request researchers make changes to the study’s design or procedure or, in extreme cases, deny approval of the study altogether.

The British Psychological Society (BPS) and American Psychological Association (APA) have issued a code of ethics in psychology that provides guidelines for conducting research. Some of the more important ethical issues are as follows:

Informed Consent

Before the study begins, the researcher must outline to the participants what the research is about and then ask for their consent (i.e., permission) to participate.

An adult (18 years +) capable of being permitted to participate in a study can provide consent. Parents/legal guardians of minors can also provide consent to allow their children to participate in a study.

Whenever possible, investigators should obtain the consent of participants. In practice, this means it is not sufficient to get potential participants to say “Yes.”

They also need to know what it is that they agree to. In other words, the psychologist should, so far as is practicable, explain what is involved in advance and obtain the informed consent of participants.

Informed consent must be informed, voluntary, and rational. Participants must be given relevant details to make an informed decision, including the purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits. Consent must be given voluntarily without undue coercion. And participants must have the capacity to rationally weigh the decision.

Components of informed consent include clearly explaining the risks and expected benefits, addressing potential therapeutic misconceptions about experimental treatments, allowing participants to ask questions, and describing methods to minimize risks like emotional distress.

Investigators should tailor the consent language and process appropriately for the study population. Obtaining meaningful informed consent is an ethical imperative for human subjects research.

The voluntary nature of participation should not be compromised through coercion or undue influence. Inducements should be fair and not excessive/inappropriate.

However, it is not always possible to gain informed consent. Where the researcher can’t ask the actual participants, a similar group of people can be asked how they would feel about participating.

If they think it would be OK, then it can be assumed that the real participants will also find it acceptable. This is known as presumptive consent.

However, a problem with this method is that there might be a mismatch between how people think they would feel/behave and how they actually feel and behave during a study.

In order for consent to be ‘informed,’ consent forms may need to be accompanied by an information sheet for participants’ setting out information about the proposed study (in lay terms), along with details about the investigators and how they can be contacted.

Special considerations exist when obtaining consent from vulnerable populations with decisional impairments, such as psychiatric patients, intellectually disabled persons, and children/adolescents. Capacity can vary widely so should be assessed individually, but interventions to improve comprehension may help. Legally authorized representatives usually must provide consent for children.

Participants must be given information relating to the following:

- A statement that participation is voluntary and that refusal to participate will not result in any consequences or any loss of benefits that the person is otherwise entitled to receive.

- Purpose of the research.

- All foreseeable risks and discomforts to the participant (if there are any). These include not only physical injury but also possible psychological.

- Procedures involved in the research.

- Benefits of the research to society and possibly to the individual human subject.

- Length of time the subject is expected to participate.

- Person to contact for answers to questions or in the event of injury or emergency.

- Subjects” right to confidentiality and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences.

Debriefing after a study involves informing participants about the purpose, providing an opportunity to ask questions, and addressing any harm from participation. Debriefing serves an educational function and allows researchers to correct misconceptions. It is an ethical imperative.

After the research is over, the participant should be able to discuss the procedure and the findings with the psychologist. They must be given a general idea of what the researcher was investigating and why, and their part in the research should be explained.

Participants must be told if they have been deceived and given reasons why. They must be asked if they have any questions, which should be answered honestly and as fully as possible.

Debriefing should occur as soon as possible and be as full as possible; experimenters should take reasonable steps to ensure that participants understand debriefing.

“The purpose of debriefing is to remove any misconceptions and anxieties that the participants have about the research and to leave them with a sense of dignity, knowledge, and a perception of time not wasted” (Harris, 1998).

The debriefing aims to provide information and help the participant leave the experimental situation in a similar frame of mind as when he/she entered it (Aronson, 1988).

Exceptions may exist if debriefing seriously compromises study validity or causes harm itself, like negative emotions in children. Consultation with an institutional review board guides exceptions.

Debriefing indicates investigators’ commitment to participant welfare. Harms may not be raised in the debriefing itself, so responsibility continues after data collection. Following up demonstrates respect and protects persons in human subjects research.

Protection of Participants

Researchers must ensure that those participating in research will not be caused distress. They must be protected from physical and mental harm. This means you must not embarrass, frighten, offend or harm participants.

Normally, the risk of harm must be no greater than in ordinary life, i.e., participants should not be exposed to risks greater than or additional to those encountered in their normal lifestyles.

The researcher must also ensure that if vulnerable groups are to be used (elderly, disabled, children, etc.), they must receive special care. For example, if studying children, ensure their participation is brief as they get tired easily and have a limited attention span.

Researchers are not always accurately able to predict the risks of taking part in a study, and in some cases, a therapeutic debriefing may be necessary if participants have become disturbed during the research (as happened to some participants in Zimbardo’s prisoners/guards study ).

Deception research involves purposely misleading participants or withholding information that could influence their participation decision. This method is controversial because it limits informed consent and autonomy, but can provide otherwise unobtainable valuable knowledge.

Types of deception include (i) deliberate misleading, e.g. using confederates, staged manipulations in field settings, deceptive instructions; (ii) deception by omission, e.g., failure to disclose full information about the study, or creating ambiguity.

The researcher should avoid deceiving participants about the nature of the research unless there is no alternative – and even then, this would need to be judged acceptable by an independent expert. However, some types of research cannot be carried out without at least some element of deception.