- Sign in to the Digital Toolbox

Already registered?

Not yet registered, the cold war (1945–1989), the vietnam war.

- Resources (33)

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

HISTORY T1 W3 Gr. 12: THE EXTENSION OF THE COLD WAR: CASE STUDY: VIETNAM

ESSAY: THE EXTENSION OF THE COLD WAR: CASE STUDY: VIETNAM

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- About OAH Magazine of History

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

The Cold War and Vietnam

George Herring is Alumni Professor of History at the University of Kentucky. Much of his research and writing has focused on the Vietnam War, and he is the author of America's Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950–1975, 4th ed. (2001) .

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

George C. Herring, The Cold War and Vietnam, OAH Magazine of History , Volume 18, Issue 5, October 2004, Pages 18–21, https://doi.org/10.1093/maghis/18.5.18

- Permissions Icon Permissions

T he cold war and the American war in Vietnam cannot be disentangled. Had it not been for the cold war, the U.S., China, and the Soviet Union would not have intervened in what would likely have remained a localized anticolonial struggle in French Indochina. The cold war shaped the way the Vietnam War was fought and significantly affected its outcome. The war in Vietnam in turn influenced the direction taken by the cold war after 1975.

The conflict in Vietnam stemmed from the interaction of two major phenomena of the post-World War II era, decolonization—the dissolution of colonial empires—and the cold war. The rise of nationalism in the colonial areas and the weakness of the European powers after the Second World War combined to destroy a colonial system that had been an established feature of world politics for centuries. A change of this magnitude did not occur smoothly, and in Vietnam it led to war. When France fell to Germany in 1940, Japan imposed a protectorate upon the French colony in Vietnam, and in March 1945 the Japanese overthrew the French puppet government. In August 1945, Vietnamese nationalists led by the charismatic patriot Ho Chi Minh seized the opportunity presented by Japan's surrender to proclaim the independence of their country. Determined to recover their empire, the French set out to regain control of Vietnam. After more than a year of ultimately futile negotiations, a war began in November 1946 that would not end until Saigon fell in April 1975.

Email alerts

Citing articles via, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1938-2340

- Print ISSN 0882-228X

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

The Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1955-1975) was a military conflict between North Vietnam (supported by China and the Soviet Union) and South Vietnam (supported by the United States, South Korea, Australia, and several other US allies). It is often described as a proxy war of the Cold War era. It ended with the capture of Saigon, the country’s capital, by the North Vietnamese Army in April 1975. The Vietnam War claimed millions of lives. It resulted in the reunification of Vietnam under a communist government and communist prevalence in neighboring Laos and Cambodia. In the United States, which lost more than 50,000 soldiers in the war, mass anti-war protests broke out during the last stage of the conflict.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

Viet nam and the cold war: a short bibliographical essay.

The Cold War in Asia blew the wars for post-colonial Việt Nam out of all proportion, magnified the centuries-old web of Vietnamese diaspora into a train wreck, and laid the ground for post-socialist transition to an especially lively civil society under abiding authoritarian rule. These fascinating stories are well served by world scholarship, but best told by Vietnamese witnesses, who testify through daily life experiences to the abstractions of policy and research.

Duong Van Mai Elliott’s The Sacred Willow , the history of her family from the eighteenth through the end of the twentieth century, introduces both the Vietnamese sense of the national past and accurately reflects mainstream scholarship. Her narrative is too substantial for most classrooms, but as preparation, it will situate the non-specialist instructor in a local view of the Vietnamese nation.

Elliott, a former RAND researcher in the war between Sài Ģòn and Hà Nội, researched and interviewed her extensive family to flesh out the story of Việt Nam since the dawn of the Nguyen dynasty (1802–1945). Her procedure is Tolstoyan, proceeding from set pieces on the stage of domestic life to social science overview, providing many dramatic passages that can be taught, as well as citations to the scholarly literature for research projects.

Most teachers in survey courses can bring only one or two Vietnamese texts into the classroom. There is a rich opportunity to select those exact texts that direct attention to Vietnamese views of the topic of the course. Despite ritual laments of scarcity, in fact a great many texts have been published in English over the last forty years. Improved access through interlibrary loan, Google, and dealer networks have made them all available with planning.

Two tools are at hand on the Web to guide the search for the right few texts. John C. Schafer’s Vietnamese Perspectives on the War in Vietnam provides a classified, annotated view of the translated literature available as of 1996. Schafer taught in Huế during the war and researched Vietnamese literature on his own during a career teaching college English despite a heavy class load. His two-handed grasp of both the subject matter and its possibilities in the US classroom is unmatched. The Yale University Council on Southeast Asian Studies, who published the book, now makes it available on their Web site. 1

Once oriented by Elliott and Schafer, an instructor can search further in Wikivietlit , the online encyclopedia of the Viet Nam Literature Project. 2 It is intended for those literate in Vietnamese and French as well as English, but automated categories provide lists of authors translated into English by genre and topic. Author entries provide both backgrounds for instructors and avenues for student research.

I made my own suggestions in “Not a War” in the fall 1997 issue of Education About Asia . 3 In the two stories by Le Minh Khue, I discussed teaching “Distant Stars” and “Last Rain of the Monsoon,” which depict two of the three most important Vietnamese aspects of the Cold War in Asia, the hot war in Việt Nam and the new society it created. Le Minh Khue, one of the most prestigious book editors in her country, has since worked with novelist Wayne Karlin and Curbstone Press to bring out a lengthy series of such work by her colleagues.

Where course content includes the memory of the war, an instructor might also consider works by foreigners who scrupulously attend to the testimony and interpretation of non-writers.

Where course content includes the memory of the war, an instructor might also consider works by foreigners who scrupulously attend to the testimony and interpretation of non-writers. Martha Hess’s Then the Americans Came , from a variety of Southerners; Lady Borton’s After Sorrow , from communist women in the North and Central regions; and, Heonik Kwon’s astonishing report of the afterlife of deceased Vietnamese, Ghosts of War in Viet Nam , are rich candidates.

Other texts, mostly memoir, address the third great consequence of the Cold War in Asia for the Vietnamese—their intensified diaspora after 1975. These texts range from those by adult emigrants with a firm grasp on the home country, such as Le Ly Haslip’s When Heaven and Earth Changed Places , Lucy Nguyen’s Dragon Child , Quang Van Nguyen and Marjorie Pivar’s Fourth Uncle in the Mountain —to writers from the next generation, such as Andrew X. Pham and le thi diem thuy [ sic ], for whom the war is fantasy and family secrets. Nguyen Qui Duc’s Where the Ashes Are and Quang X. Pham’s A Sense of Duty combine the two impulses, acting on their memories to investigate the family past and its public context.

In this brief introduction to teachable resources in English on the Cold War in Việt Nam, my largest point is that no longer are there just a handful of accessible texts to consider for teaching, whose limitations themselves determined the content of many past courses. There are now dozens of teachable texts in print or online from which the instructor may choose. Working through Elliott for a panoramic Vietnamese view of the Cold War, with Schafer’s bibliography, and the Wikivietlit encyclopedia, a motivated instructor can find exactly the right works for his or her students.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

1. John C. Schafer, Yale University Council on Southeast Asian Studies , “Vietnamese Studies on the War in Vietnam,” online at http://www.yale.edu/seas/bibliography/.

2. Wikivietlit, Viet Nam Literature Project, at http://vietnamlit.org/wiki/index.php?title=Wikivietlit .

3. Dan Duffy, “Not a War. Suggestions from a College Reading Course in Fiction and Poetry from Vietnam and Vietnamese Americans,” EAA , 2:2 (Fall 1997), 9.

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Throughout May, AAS is celebrating Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Heritage Month. Read more

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Pentagon Papers

The Secrets and Lies of the Vietnam War, Exposed in One Epic Document

With the Pentagon Papers revelations, the U.S. public’s trust in the government was forever diminished.

By Elizabeth Becker

This article is part of a special report on the 50th anniversary of the Pentagon Papers.

Brandishing a captured Chinese machine gun, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara appeared at a televised news conference in the spring of 1965. The United States had just sent its first combat troops to South Vietnam, and the new push, he boasted, was further wearing down the beleaguered Vietcong.

“In the past four and one-half years, the Vietcong, the Communists, have lost 89,000 men,” he said. “You can see the heavy drain.”

That was a lie. From confidential reports, McNamara knew the situation was “bad and deteriorating” in the South. “The VC have the initiative,” the information said. “Defeatism is gaining among the rural population, somewhat in the cities, and even among the soldiers.”

Lies like McNamara’s were the rule, not the exception, throughout America’s involvement in Vietnam . The lies were repeated to the public, to Congress, in closed-door hearings, in speeches and to the press. The real story might have remained unknown if, in 1967, McNamara had not commissioned a secret history based on classified documents — which came to be known as the Pentagon Papers .

By then, he knew that even with nearly 500,000 U.S. troops in theater, the war was at a stalemate. He created a research team to assemble and analyze Defense Department decision-making dating back to 1945. This was either quixotic or arrogant. As secretary of defense under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, McNamara was an architect of the war and implicated in the lies that were the bedrock of U.S. policy.

Daniel Ellsberg, an analyst on the study, eventually leaked portions of the report to The New York Times , which published excerpts in 1971. The revelations in the Pentagon Papers infuriated a country sick of the war, the body bags of young Americans, the photographs of Vietnamese civilians fleeing U.S. air attacks and the endless protests and counterprotests that were dividing the country as nothing had since the Civil War.

The lies revealed in the papers were of a generational scale, and, for much of the American public, this grand deception seeded a suspicion of government that is even more widespread today.

Officially titled “Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force,” the papers filled 47 volumes, covering the administrations of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to President Lyndon B. Johnson. Their 7,000 pages chronicled, in cold, bureaucratic language, how the United States got itself mired in a long, costly war in a small Southeast Asian country of questionable strategic importance.

They are an essential record of the first war the United States lost. For modern historians, they foreshadow the mind-set and miscalculations that led the United States to fight the “forever wars” of Iraq and Afghanistan.

The original sin was the decision to support the French rulers in Vietnam. President Harry S. Truman subsidized their effort to take back their Indochina colonies. The Vietnamese nationalists were winning their fight for independence under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, a Communist. Ho had worked with the United States against Japan in World War II, but, in the Cold War, Washington recast him as the stalking horse for Soviet expansionism.

American intelligence officers in the field said that was not the case, that they had found no evidence of a Soviet plot to take over Vietnam, much less Southeast Asia. As one State Department memo put it, “If there is a Moscow-directed conspiracy in Southeast Asia, Indochina is an anomaly.”

But with an eye on China, where the Communist Mao Zedong had won the civil war, President Dwight D. Eisenhower said defeating Vietnam’s Communists was essential “to block further Communist expansion in Asia.” If Vietnam became Communist, then the countries of Southeast Asia would fall like dominoes.

This belief in this domino theory was so strong that the United States broke with its European allies and refused to sign the 1954 Geneva Accords ending the French war. Instead, the United States continued the fight, giving full backing to Ngo Dinh Diem, the autocratic, anti-Communist leader of South Vietnam. Gen. J. Lawton Collins wrote from Vietnam, warning Eisenhower that Diem was an unpopular and incapable leader and should be replaced. If he was not, Gen. Collins wrote, “I recommend re-evaluation of our plans for assisting Southeast Asia.”

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles disagreed, writing in a cable included in the Pentagon Papers, “We have no other choice but continue our aid to Vietnam and support of Diem.”

Nine years and billions of American dollars later, Diem was still in power, and it fell to President Kennedy to solve the long-predicted problem.

After facing down the Soviet Union in the Berlin crisis, Kennedy wanted to avoid any sign of Cold War fatigue and easily accepted McNamara’s counsel to deepen the U.S. commitment to Saigon. The secretary of defense wrote in one report, “The loss of South Vietnam would make pointless any further discussion about the importance of Southeast Asia to the Free World.”

The president increased U.S. military advisers tenfold and introduced helicopter missions. In return for the support, Kennedy wanted Diem to make democratic reforms. Diem refused.

A popular uprising in South Vietnam, led by Buddhist clerics, followed. Fearful of losing power as well, South Vietnamese generals secretly received American approval to overthrow Diem. Despite official denials, U.S. officials were deeply involved.

“Beginning in August of 1963, we variously authorized, sanctioned and encouraged the coup efforts …,” the Pentagon Papers revealed. “We maintained clandestine contact with them throughout the planning and execution of the coup and sought to review their operational plans.”

The coup ended with Diem’s killing and a deepening of American involvement in the war. As the authors of the papers concluded, “Our complicity in his overthrow heightened our responsibilities and our commitment.”

Three weeks later, President Kennedy was assassinated, and the Vietnam issue fell to President Johnson.

He had officials secretly draft a resolution for Congress to grant him the authority to fight in Vietnam without officially declaring war.

Missing was a pretext, a small-bore “Pearl Harbor” moment. That came on Aug. 4, 1964, when the White House announced that the North Vietnamese had attacked the U.S.S. Maddox in international waters in the Gulf of Tonkin. This “attack,” though, was anything but unprovoked aggression. Gen. William C. Westmoreland, the head of U.S. forces in Vietnam, had commanded the South Vietnamese military while they staged clandestine raids on North Vietnamese islands. North Vietnamese PT boats fought back and had “mistaken Maddox for a South Vietnamese escort vessel,” according to a report. (Later investigations showed the attack never happened.)

Testifying before the Senate, McNamara lied, denying any American involvement in the Tonkin Gulf attacks: “Our Navy played absolutely no part in, was not associated with, was not aware of any South Vietnamese actions, if there were any.”

Three days after the announcement of the “incident,” the administration persuaded Congress to pass the Tonkin Gulf Resolution to approve and support “the determination of the president, as commander in chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression” — an expansion of the presidential power to wage war that is still used regularly. Johnson won the 1964 election in a landslide.

Seven months later, he sent combat troops to Vietnam without declaring war, a decision clad in lies. The initial deployment of 20,000 troops was described as “military support forces” under a “change of mission” to “permit their more active use” in Vietnam. Nothing new.

As the Pentagon Papers later showed, the Defense Department also revised its war aims: “70 percent to avoid a humiliating U.S. defeat … 20 percent to keep South Vietnam (and then adjacent) territory from Chinese hands, 10 percent to permit the people of South Vietnam to enjoy a better, freer way of life.”

Westmoreland considered the initial troop deployment a stopgap measure and requested 100,000 more. McNamara agreed. On July 20, 1965, he wrote in a memo that even though “the U.S. killed-in-action might be in the vicinity of 500 a month by the end of the year,” the general’s overall strategy was “likely to bring about a success in Vietnam.”

As the Pentagon Papers later put it, “Never again while he was secretary of defense would McNamara make so optimistic a statement about Vietnam — except in public.”

Fully disillusioned at last, McNamara argued in a 1967 memo to the president that more of the same — more troops, more bombing — would not win the war. In an about-face, he suggested that the United States declare victory and slowly withdraw.

And in a rare acknowledgment of the suffering of the Vietnamese people, he wrote, “The picture of the world’s greatest superpower killing or seriously injuring 1,000 noncombatants a week, while trying to pound a tiny backward nation into submission on an issue whose merits are hotly disputed, is not a pretty one.”

Johnson was furious and soon approved increasing the U.S. troop commitment to nearly 550,000. By year’s end, he had forced McNamara to resign, but the defense secretary had already commissioned the Pentagon Papers.

In 1968, Johnson announced that he would not run for re-election; Vietnam had become his Waterloo. Nixon won the White House on the promise to bring peace to Vietnam. Instead, he expanded the war by invading Cambodia, which convinced Daniel Ellsberg that he had to leak the secret history.

After The New York Times began publishing the Pentagon Papers on Sunday, June 13, 1971, the nation was stunned. The response ranged from horror to anger to disbelief. There was furor over the betrayal of national secrets. Opponents of the war felt vindicated. Veterans, especially those who had served multiple tours in Vietnam, were pained to discover that Americans officials knew the war had been a failed proposition nearly from the beginning.

Convinced that Ellsberg posed a threat to Nixon’s re-election campaign, the White House approved an illegal break-in at the Beverly Hills, Calif., office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, hoping to find embarrassing confessions on file. The burglars — known as the Plumbers — found nothing, and got away undetected. The following June, when another such crew broke into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters in the Watergate complex in Washington, they were caught.

The North Vietnamese mounted a final offensive, captured Saigon and won the war in April 1975. Three years later, Vietnam invaded Cambodia — another Communist country — and overthrew the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime. That was the sole country Communist Vietnam ever invaded, forever undercutting the domino theory — the war’s foundational lie.

Elizabeth Becker is a former New York Times correspondent who began her career covering the Cambodia campaign of the Vietnam War. She is the author, most recently, of “You Don’t Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War.”

The Cold War (1945-1989) essay

The Cold War is considered to be a significant event in Modern World History. The Cold War dominated a rather long time period: between 1945, or the end of the World War II, and 1990, the collapse of the USSR. This period involved the relationships between two superpowers: the United States and the USSR. The Cold War began in Eastern Europe and Germany, according to the researchers of the Institute of Contemporary British History (Warner 15). Researchers state that “the USSR and the United States of America held the trump cards, nuclear bombs and missiles” (Daniel 489). In other words, during the Cold War, two nations took the fate of the world under their control. The progression of the Cold War influenced the development of society, which became aware of the threat of nuclear war. After the World War II, the world experienced technological progress, which provided “the Space Race, computer development, superhighway construction, jet airliner development, the creation of international phone system, the advent of television, enormous progress in medicine, and the creation of mass consumerism, and many other achievements” (Daniel 489). Although the larger part of the world lived in poverty and lacked technological progress, the United States and other countries of Western world succeeded in economic development. The Cold War, which began in 1945, reflected the increased role of technological progress in the establishment of economic relationships between two superpowers. The Cold War involved internal and external conflicts between two superpowers, the United States and the USSR, leading to eventual breakdown of the USSR.

- The Cold War: background information

The Cold War consisted of several confrontations between the United States and the USSR, supported by their allies. According to researchers, the Cold War was marked by a number of events, including “the escalating arms race, a competition to conquer space, a dangerously belligerent for of diplomacy known as brinkmanship, and a series of small wars, sometimes called “police actions” by the United States and sometimes excused as defense measures by the Soviets” (Gottfried 9). The Cold War had different influences on the United States and the USSR. For the USSR, the Cold War provided massive opportunities for the spread of communism across the world, Moscow’s control over the development of other nations and the increased role of the Soviet Communist party.

In fact, the Cold War could split the wartime alliance formed to oppose the plans of Nazi Germany, leaving the USSR and the United States as two superpowers with considerable economic and political differences. The USSR was based on a single-party Marxist–Leninist system, while the United States was a capitalist state with democratic governance based on free elections.

The key figure in the Cold War was the Soviet leader Gorbachev, who was elected in 1985. He managed to change the direction of the USSR, making the economies of communist ruled states independent. The major reasons for changing in the course were poor technological development of the USSR (Gottfried 115). Gorbachev believed that radical changes in political power could improve the Communist system. At the same time, he wanted to stop the Cold War and tensions with the United States. The cost of nuclear arms race had negative impact on the economy of the USSR. The leaders of the United States accepted the proposed relationships, based on cooperation and mutual trust. The end of the Cold War was marked by signing the INF treaty in 1987 (Gottfried 115).

- The origins of the Cold War

Many American historians state that the Cold War began in 1945. However, according to Russian researchers, historians and analysts “the Cold War began with the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, for this was when the capitalist world began its systematic opposition to and effort to undermine the world’s first socialist state and society” (Warner13). For Russians, the Cold War was hot in 1918-1922, when the Allied Intervention policy implemented in Russia during the Russian Civil War. According to John W. Long, “the U.S. intervention in North Russia was a policy formulated by President Wilson during the first half of 1918 at the urgent insistence of Britain, France and Italy, the chief World War I allies” (380).

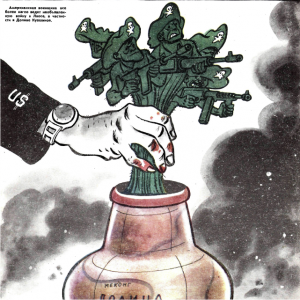

Nevertheless, there are some other opinions regarding the origins of the Cold War. For example, Geoffrey Barraclough, an outstanding English historian, states that the events in the Far East at the end of the century contributed to the origins of the Cold War. He argues that “during the previous hundred years, Russia and the United States has tended to support each other against England; but now, as England’s power passed its zenith, they came face to face across the Pacific” (Warner 13). According to Barraclough, the Cold War is associated with the conflict of interests, which involved European countries, the Middle East and South East Asia. Finally, this conflict divided the world into two camps. Thus, the Cold War origins are connected with the spread of ideological conflict caused by the emergence of the new power in the early 20-th century (Warner 14). The Cold War outbreak was associated with the spread of propaganda on the United States by the USSR. The propagandistic attacks involved the criticism of the U.S. leaders and their policies. These attacked were harmful to the interests of American nation (Whitton 151).

- The major causes of the Cold War

The United States and the USSR were regarded as two superpowers during the Cold War, each having its own sphere of influence, its power and forces. The Cold War had been the continuing conflict, caused by tensions, misunderstandings and competitions that existed between the United States and the USSR, as well as their allies from 1945 to the early 1990s (Gottfried 10). Throughout this long period, there was the so-called rivalry between the United States and the USSR, which was expressed through various transformations, including military buildup, the spread of propaganda, the growth of espionage, weapons development, considerable industrial advances, and competitive technological developments in different spheres of human activity, such as medicine, education, space exploration, etc.

There four major causes of the Cold War, which include:

- Ideological differences (communism v. capitalism);

- Mutual distrust and misperception;

- The fear of the United State regarding the spread of communism;

- The nuclear arms race (Gottfried 10).

The major causes of the Cold War point out to the fact that the USSR was focused on the spread of communist ideas worldwide. The United States followed democratic ideas and opposed the spread of communism. At the same time, the acquisition of atomic weapons by the United States caused fear in the USSR. The use of atomic weapons could become the major reason of fear of both the United States and the USSR. In other words, both countries were anxious about possible attacks from each other; therefore, they were following the production of mass destruction weapons. In addition, the USSR was focused on taking control over Eastern Europe and Central Asia. According to researchers, the USSR used various strategies to gain control over Eastern Europe and Central Asia in the years 1945-1980. Some of these strategies included “encouraging the communist takeover of governments in Eastern Europe, the setting up of Comecon, the Warsaw Pact, the presence of the Red Army in Eastern Europe, and the Brezhnev Doctrine” (Phillips 118). These actions were the major factors for the suspicions and concerns of the United States. In addition, the U.S. President had a personal dislike of the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and his policies. In general, the United States was concerned by the Soviet Union’s actions regarding the occupied territory of Germany, while the USSR feared that the United States would use Western Europe as the major tool for attack.

- The consequences of the Cold War

The consequences of the Cold War include both positive and negative effects for both the United States and the USSR.

- Both the United States and the USSR managed to build up huge arsenals of atomic weapons of mass destruction and ballistic missiles.

- The Cold War provided opportunities for the establishment of the military blocs, NATO and the Warsaw Pact.

- The Cold War led to the emergence of the destructive military conflicts, like the Vietnam War and the Korean War, which took the lives of millions of people (Gottfried13).

- The USSR collapsed because of considerable economic, political and social challenges.

- The Cold War led to the destruction of the Berlin Wall and the unification of the two German nations.

- The Cold War led to the disintegration of the Warsaw Pact (Gottfried 136).

- The Cold war provided the opportunities for achieving independence of the Baltic States and some former Soviet Republics.

- The Cold War made the United States the sole superpower of the world because of the collapse of the USSR in 1990.

- The Cold War led to the collapse of Communism and the rise of globalization worldwide (Phillips 119).

The impact of the Cold War on the development of many countries was enormous. The consequences of the Cold War were derived from numerous internal problems of the countries, which were connected with the USSR, especially developing countries (India, Africa, etc.). This fact means that foreign policies of many states were transformed (Gottfried 115).

The Cold War (1945-1989) essay part 2

Do you like this essay?

Our writers can write a paper like this for you!

Order your paper here .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Cold War History

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 26, 2023 | Original: October 27, 2009

The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension marked by competition and confrontation between communist nations led by the Soviet Union and Western democracies including the United States. During World War II , the United States and the Soviets fought together as allies against Nazi Germany . However, U.S./Soviet relations were never truly friendly: Americans had long been wary of Soviet communism and Russian leader Joseph Stalin ’s tyrannical rule. The Soviets resented Americans’ refusal to give them a leading role in the international community, as well as America’s delayed entry into World War II, in which millions of Russians died.

These grievances ripened into an overwhelming sense of mutual distrust and enmity that never developed into open warfare (thus the term “cold war”). Soviet expansionism into Eastern Europe fueled many Americans’ fears of a Russian plan to control the world. Meanwhile, the USSR came to resent what they perceived as U.S. officials’ bellicose rhetoric, arms buildup and strident approach to international relations. In such a hostile atmosphere, no single party was entirely to blame for the Cold War; in fact, some historians believe it was inevitable.

Containment

By the time World War II ended, most American officials agreed that the best defense against the Soviet threat was a strategy called “containment.” In his famous “Long Telegram,” the diplomat George Kennan (1904-2005) explained the policy: The Soviet Union, he wrote, was “a political force committed fanatically to the belief that with the U.S. there can be no permanent modus vivendi [agreement between parties that disagree].” As a result, America’s only choice was the “long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.”

“It must be the policy of the United States,” he declared before Congress in 1947, “to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation…by outside pressures.” This way of thinking would shape American foreign policy for the next four decades.

Did you know? The term 'cold war' first appeared in a 1945 essay by the English writer George Orwell called 'You and the Atomic Bomb.'

The Cold War: The Atomic Age

The containment strategy also provided the rationale for an unprecedented arms buildup in the United States. In 1950, a National Security Council Report known as NSC–68 had echoed Truman’s recommendation that the country use military force to contain communist expansionism anywhere it seemed to be occurring. To that end, the report called for a four-fold increase in defense spending.

In particular, American officials encouraged the development of atomic weapons like the ones that had ended World War II. Thus began a deadly “ arms race .” In 1949, the Soviets tested an atom bomb of their own. In response, President Truman announced that the United States would build an even more destructive atomic weapon: the hydrogen bomb, or “superbomb.” Stalin followed suit.

As a result, the stakes of the Cold War were perilously high. The first H-bomb test, in the Eniwetok atoll in the Marshall Islands, showed just how fearsome the nuclear age could be. It created a 25-square-mile fireball that vaporized an island, blew a huge hole in the ocean floor and had the power to destroy half of Manhattan. Subsequent American and Soviet tests spewed radioactive waste into the atmosphere.

The ever-present threat of nuclear annihilation had a great impact on American domestic life as well. People built bomb shelters in their backyards. They practiced attack drills in schools and other public places. The 1950s and 1960s saw an epidemic of popular films that horrified moviegoers with depictions of nuclear devastation and mutant creatures. In these and other ways, the Cold War was a constant presence in Americans’ everyday lives.

HISTORY Vault: Nuclear Terror

Now more than ever, terrorist groups are obtaining nuclear weapons. With increasing cases of theft and re-sale at dozens of Russian sites, it's becoming more and more likely for terrorists to succeed.

The Cold War and the Space Race

Space exploration served as another dramatic arena for Cold War competition. On October 4, 1957, a Soviet R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile launched Sputnik (Russian for “traveling companion”), the world’s first artificial satellite and the first man-made object to be placed into the Earth’s orbit. Sputnik’s launch came as a surprise, and not a pleasant one, to most Americans.

In the United States, space was seen as the next frontier, a logical extension of the grand American tradition of exploration, and it was crucial not to lose too much ground to the Soviets. In addition, this demonstration of the overwhelming power of the R-7 missile–seemingly capable of delivering a nuclear warhead into U.S. air space–made gathering intelligence about Soviet military activities particularly urgent.

In 1958, the U.S. launched its own satellite, Explorer I, designed by the U.S. Army under the direction of rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, and what came to be known as the Space Race was underway. That same year, President Dwight Eisenhower signed a public order creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), a federal agency dedicated to space exploration, as well as several programs seeking to exploit the military potential of space. Still, the Soviets were one step ahead, launching the first man into space in April 1961.

That May, after Alan Shepard become the first American man in space, President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) made the bold public claim that the U.S. would land a man on the moon by the end of the decade. His prediction came true on July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong of NASA’s Apollo 11 mission , became the first man to set foot on the moon, effectively winning the Space Race for the Americans.

U.S. astronauts came to be seen as the ultimate American heroes. Soviets, in turn, were pictured as the ultimate villains, with their massive, relentless efforts to surpass America and prove the power of the communist system.

The Cold War and the Red Scare

Meanwhile, beginning in 1947, the House Un-American Activities Committee ( HUAC ) brought the Cold War home in another way. The committee began a series of hearings designed to show that communist subversion in the United States was alive and well.

In Hollywood , HUAC forced hundreds of people who worked in the movie industry to renounce left-wing political beliefs and testify against one another. More than 500 people lost their jobs. Many of these “blacklisted” writers, directors, actors and others were unable to work again for more than a decade. HUAC also accused State Department workers of engaging in subversive activities. Soon, other anticommunist politicians, most notably Senator Joseph McCarthy (1908-1957), expanded this probe to include anyone who worked in the federal government.

Thousands of federal employees were investigated, fired and even prosecuted. As this anticommunist hysteria spread throughout the 1950s, liberal college professors lost their jobs, people were asked to testify against colleagues and “loyalty oaths” became commonplace.

The Cold War Abroad

The fight against subversion at home mirrored a growing concern with the Soviet threat abroad. In June 1950, the first military action of the Cold War began when the Soviet-backed North Korean People’s Army invaded its pro-Western neighbor to the south. Many American officials feared this was the first step in a communist campaign to take over the world and deemed that nonintervention was not an option. Truman sent the American military into Korea, but the Korean War dragged to a stalemate and ended in 1953.

In 1955, the United States and other members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) made West Germany a member of NATO and permitted it to remilitarize. The Soviets responded with the Warsaw Pact , a mutual defense organization between the Soviet Union, Albania, Poland, Romania, Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria that set up a unified military command under Marshal Ivan S. Konev of the Soviet Union.

Other international disputes followed. In the early 1960s, President Kennedy faced a number of troubling situations in his own hemisphere. The Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 and the Cuban missile crisis the following year seemed to prove that the real communist threat now lay in the unstable, postcolonial “Third World.”

Nowhere was this more apparent than in Vietnam , where the collapse of the French colonial regime had led to a struggle between the American-backed nationalist Ngo Dinh Diem in the south and the communist nationalist Ho Chi Minh in the north. Since the 1950s, the United States had been committed to the survival of an anticommunist government in the region, and by the early 1960s it seemed clear to American leaders that if they were to successfully “contain” communist expansionism there, they would have to intervene more actively on Diem’s behalf. However, what was intended to be a brief military action spiraled into a 10-year conflict .

The End of the Cold War and Effects

Almost as soon as he took office, President Richard Nixon (1913-1994) began to implement a new approach to international relations. Instead of viewing the world as a hostile, “bi-polar” place, he suggested, why not use diplomacy instead of military action to create more poles? To that end, he encouraged the United Nations to recognize the communist Chinese government and, after a trip there in 1972, began to establish diplomatic relations with Beijing.

At the same time, he adopted a policy of “détente”—”relaxation”—toward the Soviet Union. In 1972, he and Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev (1906-1982) signed the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I), which prohibited the manufacture of nuclear missiles by both sides and took a step toward reducing the decades-old threat of nuclear war.

Despite Nixon’s efforts, the Cold War heated up again under President Ronald Reagan (1911-2004). Like many leaders of his generation, Reagan believed that the spread of communism anywhere threatened freedom everywhere. As a result, he worked to provide financial and military aid to anticommunist governments and insurgencies around the world. This policy, particularly as it was applied in the developing world in places like Grenada and El Salvador, was known as the Reagan Doctrine .

Even as Reagan fought communism in Central America, however, the Soviet Union was disintegrating. In response to severe economic problems and growing political ferment in the USSR, Premier Mikhail Gorbachev (1931-2022) took office in 1985 and introduced two policies that redefined Russia’s relationship to the rest of the world: “glasnost,” or political openness, and “ perestroika ,” or economic reform.

Soviet influence in Eastern Europe waned. In 1989, every other communist state in the region replaced its government with a noncommunist one. In November of that year, the Berlin Wall –the most visible symbol of the decades-long Cold War–was finally destroyed, just over two years after Reagan had challenged the Soviet premier in a speech at Brandenburg Gate in Berlin: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” By 1991, the Soviet Union itself had fallen apart. The Cold War was over.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Reasons Behind U.S. Involvement in Vietnam

This essay about U.S. involvement in Vietnam examines the ideological, political, and strategic reasons behind America’s decision to intervene. It highlights the influence of the Cold War and the policy of containment, which aimed to prevent the spread of communism. The essay discusses the initial support for the French colonial government, the establishment of an anti-communist regime in South Vietnam, and the escalation of military involvement under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. It also addresses the challenges faced by U.S. forces, the impact of the Tet Offensive, the policy of Vietnamization under President Nixon, and the eventual withdrawal and fall of Saigon. The essay concludes by reflecting on the war’s lasting impacts on U.S. foreign policy and society.

How it works

The United States’ entanglement in Vietnam, which eventually burgeoned into one of the most disputed and prolonged conflicts in American annals, was impelled by a convergence of ideological, political, and strategic elements. Unraveling why the United States opted to intercede in Vietnam necessitates a deep plunge into the broader panorama of the Cold War, the containment strategies, and the intricate dynamics of Southeast Asia during the mid-20th century.

At the nucleus of the U.S. resolution to intervene lay the Cold War, a phase characterized by profound geopolitical tension and rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The chief objective of American foreign policy during this epoch was to curtail the dissemination of communism, as enunciated in the Truman Doctrine of 1947. This doctrine was predicated on the conviction that the proliferation of communism in any realm imperiled democracy universally. Vietnam, viewed as a plausible dominion susceptible to communism, emerged as a pivotal locus for U.S. strategic interests. The trepidation was that if Vietnam succumbed, other states in Southeast Asia might ensue, heralding a considerable augmentation of Soviet sway and a realignment of the global power equilibrium.

In tandem with ideological apprehensions, substantial political incentives underscored U.S. involvement in Vietnam. U.S. presidents from Harry Truman to Lyndon Johnson were swayed by the imperative to project strength against communism both domestically and internationally. The so-termed “domino theory,” positing that the collapse of one state to communism would precipitate the downfall of its neighbors, wielded considerable sway. This theory held particular sway during the 1950s and 1960s, as the United States endeavored to evince its unwavering commitment to safeguarding free nations from communist subversion and preserving its standing as a global leader.

The United States initially immersed itself in Vietnam by bolstering the French colonial administration against the Viet Minh, a communist-led independence movement. Post the French debacle at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the Geneva Accords provisionally partitioned Vietnam into a communist North and a non-communist South, with plans for nationwide elections to reunify the nation. However, apprehensive of an imminent communist triumph, the United States advocated for the establishment of an autonomous, anti-communist regime in South Vietnam, spearheaded by Ngo Dinh Diem. American advisors and financial assistance poured into South Vietnam in an endeavor to forge a stable, non-communist entity capable of thwarting communist expansion.

As the imbroglio in Vietnam intensified, the U.S. commitment deepened. The Kennedy administration augmented the contingent of military advisors in Vietnam, while also buttressing counterinsurgency endeavors against the burgeoning Viet Cong insurgency in the South. The Kennedy administration espoused the conviction that a robust, autonomous South Vietnam was imperative to containing communism in the region. This involvement escalated further under President Lyndon B. Johnson, particularly subsequent to the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964, wherein North Vietnamese forces purportedly assaulted U.S. naval vessels. This incident precipitated the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, endowing Johnson with sweeping authority to wield military force in Vietnam sans a formal declaration of war.

Johnson’s administration subsequently embarked on a policy of direct military intervention, deploying combat troops in 1965. This decision stemmed from a confluence of factors, including a conviction in the imperative of demonstrating American resolve, apprehensions of a communist victory, and the desire to maintain U.S. credibility with allies worldwide. Johnson and his advisors were also influenced by the perceived lessons of World War II, especially the perils of appeasement and the necessity of confronting aggressors promptly. The recollection of how the failure to curb aggression had culminated in global conflict in the past loomed large in the minds of U.S. policymakers.

Notwithstanding these motivations, U.S. involvement in Vietnam encountered formidable challenges. The intricate political and social milieu of Vietnam, characterized by regional, ideological, and ethnic divisions, rendered the establishment of a stable and efficacious government in the South arduous. Additionally, the guerrilla tactics employed by the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army proved markedly effective against conventional U.S. military stratagems. The dense jungles, unfamiliar terrain, and the elusive nature of the adversary compounded the trials faced by American forces.

As the war persisted, with mounting American casualties and no discernible path to victory, domestic opposition to the conflict burgeoned. The initial widespread support for the war dwindled as the American populace became increasingly cognizant of the war’s human and economic tolls. Media coverage, particularly televised depictions of combat and the stark realities of the battlefield, played a pivotal role in shaping public sentiment and opinion. The anti-war movement gained traction, precipitating widespread protests and exerting political pressure on the Johnson administration to pursue a resolution to the conflict.

The Tet Offensive of 1968 marked a pivotal juncture in the war. Though a military setback for the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces, it left an indelible psychological imprint on the American populace and policymakers. The magnitude and intensity of the offensive, characterized by coordinated assaults on urban centers and towns across South Vietnam, shattered the illusion of U.S. ascendancy in the conflict and underscored the resilience and resolve of the communist forces. In the aftermath of Tet, calls for de-escalation and dialogue intensified, prompting a gradual shift in U.S. policy.

President Richard Nixon, who assumed office following Johnson in 1969, endeavored to disentangle the United States from Vietnam through a strategy dubbed “Vietnamization.” This approach sought to bolster South Vietnamese military capabilities to assume the mantle of combat from U.S. troops, facilitating a phased withdrawal of American forces. Nixon also expanded the theater of war into neighboring Cambodia and Laos in a bid to sever North Vietnamese supply lines, a move that elicited further controversy and dissent.

Despite these endeavors, the conflict persisted, and the South Vietnamese regime grappled to withstand the onslaught from the North. The Paris Peace Accords of 1973 heralded the denouement of U.S. involvement, with American troops withdrawing and a ceasefire proclaimed. Nonetheless, the hostilities between North and South Vietnam endured, culminating in the fall of Saigon to communist forces in 1975, effectively concluding the conflict.

The Vietnam War engendered profound and enduring repercussions on U.S. foreign and domestic policy. It engendered a more circumspect approach to military intervention, often characterized as the “Vietnam Syndrome,” wherein the trauma of the conflict influenced American aversion to embarking on future overseas ventures sans well-defined objectives and broad public backing. The war also prompted a reassessment of U.S. intelligence and military capabilities, as well as the conduct and oversight of foreign policy.

In addition to its policy ramifications, the Vietnam War left an indelible mark on American society. It laid bare the constraints of U.S. power and the complexities inherent in waging war in unfamiliar and distant theaters. The conflict also laid bare schisms within American society, pitting proponents of the war effort against fervent dissenters. The ordeals endured by returning veterans, many of whom grappled with physical and psychological afflictions, underscored the human toll exacted by the war.

In hindsight, the rationale behind U.S. involvement in Vietnam was multifaceted and deeply enmeshed in the geopolitical context of the Cold War. The imperative to contain communism, safeguard international credibility, and bolster allies constituted pivotal factors that precipitated an escalating entanglement in Vietnam. However, the intricacies of the conflict, the tenacity of the communist adversaries, and the exigencies of waging a protracted campaign in Southeast Asia ultimately laid bare the limitations of American power and the challenges inherent in achieving a decisive triumph.

The Vietnam War serves as a cautionary saga and a poignant reminder of the imperative of comprehending the cultural, historical, and political backdrop of foreign interventions. It underscores the necessity of lucid objectives, comprehensive strategies, and the consideration of long-term repercussions when embroiling oneself in military conflicts. The insights gleaned from Vietnam continue to inform U.S. foreign policy and military doctrine, shaping the manner in which the United States approaches international crises and conflicts in the contemporary milieu.

Ultimately, U.S. involvement in Vietnam epitomized a convoluted and multifaceted endeavor propelled by a confluence of ideological, political, and strategic imperatives. While it aspired to curtail the spread of communism and uphold U.S. credibility, the conflict underscored the hurdles and constraints of military intervention in achieving political and strategic objectives. The legacy of the Vietnam War endures, influencing American foreign policy and serving as a sobering reminder of the costs and complexities inherent in warfare.

Cite this page

The Reasons Behind U.S. Involvement in Vietnam. (2024, May 28). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reasons-behind-u-s-involvement-in-vietnam/

"The Reasons Behind U.S. Involvement in Vietnam." PapersOwl.com , 28 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reasons-behind-u-s-involvement-in-vietnam/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Reasons Behind U.S. Involvement in Vietnam . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reasons-behind-u-s-involvement-in-vietnam/ [Accessed: 29 May. 2024]

"The Reasons Behind U.S. Involvement in Vietnam." PapersOwl.com, May 28, 2024. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reasons-behind-u-s-involvement-in-vietnam/

"The Reasons Behind U.S. Involvement in Vietnam," PapersOwl.com , 28-May-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reasons-behind-u-s-involvement-in-vietnam/. [Accessed: 29-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Reasons Behind U.S. Involvement in Vietnam . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reasons-behind-u-s-involvement-in-vietnam/ [Accessed: 29-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Origins of the Cold War - A Review Essay

Following the logic of earlier scholarly debates on which side is to be blamed for the Cold War it appears that in fact both or neither: it was the inevitable consequence of the fact that two superpowers emerged after the conflagration of WWII. The ideology confrontation mattered much less vis-a-vis this immense global power shift.

Related Papers

Jonathan Morales

Bibliography of New Cold War History

Aigul Kazhenova , Tsotne Tchanturia , Marijn Mulder , Ahmet Ömer Yüce , Sergei Zakharov , Mirkamran Huseynli , Pınar Eldemir , Angela Aiello , Rastko Lompar

This bibliography attempts to present the publications on the history of the Cold War published after 1989, the beginning of the „archival revolution” in the former Soviet bloc countries. While this first edition is still far from complete, it collects a huge number of books, articles and book chapters on the topic and it is the most extensive such bibliography so far, almost 600 pages in length. An enlarged and updated edition will be completed in 2018.

Tsotne Tchanturia , Vajda Barnabás , Gökay Çınar , Barnabás Vajda , Lenka Thérová , Simon Szilvási , Irem Osmanoglu , Rastko Lompar , Aigul Kazhenova , Pınar Eldemir , Natalija Dimić Lompar , Sára Büki

This bibliography attemts to present the publications on the history of the Cold War published after 1989, the beginning of the „archival revolution” in the former Soviet bloc countries. While this first edition is still far from complete, it collects a huge number of books, articles and book chapters on the topic and it is the most extensive such bibliography so far, almost 600 pages in length. An enlarged and updated edition will be completed in 2018. So, if you are a Cold War history scholar in any country and would like us to incude all of your publications on the Cold War (published after 1989) in the second edition, we will gladly do that. Please, send us a list of your works in which books and articles/book chapters are separated and follow the format of our bibliography. The titles of non-English language entries should be translated into English in square brackets. Please, send the list to: [email protected] The Cold War History Research Center owes special thanks to the Parallel History Project on Cooperative Security (formerly: on NATO and the Warsaw Pact) in Zurich–Washington D.C. for their permission to use the Selective Bibliography on the Cold War Alliances, compiled by Anna Locher and Cristian Nünlist, available at: http://www.php.isn.ethz.ch/lory1.ethz.ch/publications/bibliography/index.html

The Bibliography of New Cold War History (second enlarged edition)

Tsotne Tchanturia , Aigul Kazhenova , Khatia Kardava

This bibliography attempts to present the publications on the history of the Cold War published after 1989, the beginning of the „archival revolution” in the former Soviet bloc countries.

Soshum: Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities

Adewunmi J Falode , Moses Yakubu

The Cold War that occurred between 1945 and 1991 was both an international political and historical event. As a political event, the Cold War laid bare the fissures, animosities, mistrusts, misconceptions and the high-stake brinksmanship that has been part of the international political system since the birth of the modern nation-state in 1648. As a historical event, the Cold War and its end marked an important epoch in human social, economic and political development. The beginning of the Cold War marked the introduction of a new form of social and political experiment in human relations with the international arena as its laboratory. Its end signaled the end of a potent social and political force that is still shaping the course of political relationship among states in the 21 st century. The historiography of the Cold War has been shrouded in controversy. Different factors have been given for the origins of the conflict. This work is a historical and structural analysis of the historiography of the Cold War. The work analyzes the competing views of the historiography of the Cold War and create an all-encompassing and holistic historiography called the Structuralist School.

Jonathan Murphy

fabio capano

In Rosella Mamoli Zorzi e Simone Francescato (eds.), American Phantasmagoria. Modes of representation in US culture

Duccio Basosi

The first section shows that the presence of ghosts in the foreign policy decision making processes of both the United States and the Soviet Union has been detected mainly in relatively recent works. The second, third and fourth sections are dedicated to distinguishing between three different kinds of apparitions—ghosts of the past, specters of the future, and phantasmagorias, respectively. The concluding section attempts some reflections on the possible meanings of such interest of Cold War historiography for spectral figures, particularly in connection with the ongoing debates about the “very notion of Cold War.”

Eliza Gheorghe

Geoffrey Roberts

Review of Jonathan Haslam's Russia's Cold War, published in International Affairs

RELATED PAPERS

Saber and Scroll, 1:3 (Fall 2012), 34-39

Tsotne Tchanturia , Dionysios Dragonas

GTU academic journal “Intellectual”

Michelle Paranzino

Roham Alvandi , Eliza Gheorghe

Diplomatic History

William C. Wohlforth

Tina Machingaidze

Békés, Csaba, Melinda Kamár (Ed.): Students on the Cold War. New Findings and Interpretations. Budapest

Torben Gülstorff

Barbara D Krasner

Akindele Boladale

European History Quarterly

Benjamin Tromly

Helen Roche

Artemy Kalinovsky

Evanthis Hatzivassiliou

henry laycock

Cold War History

Vasil Paraskevov

Cold War International History Project Working Paper #89

Priscilla Roberts

Oxford Handbook in the History of Communism, ed. Stephen Anthony Smith (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Balazs Szalontai

Martin Grossheim

Journal of Cold War Studies

Silvio Pons

Contemporary European History

Gjert L Dyndal

The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East …

Jeffrey Burds

Stefano Bottoni

Péter Vámos

Dithekgo Mogadime

[w:] Disintegration and Integration in East-Central Europe 1919 – post-1989, red. W. Loth, N. Păun, Cluj-Napoca 2014, s. 134-146

Jerzy Lazor

Larry L Watts

Roger Voncken

The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review

Jakub Szumski

Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) Working Paper Series

Patryk Babiracki

COLD WAR. GEOPOLITICS

Patrick Kyanda

Petar Žarković

Rachel Alberstadt

gareth dale

Elidor Mehilli

Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

to submit an obituary

To place an obituary Monday through Friday, 8:30am to 3:00pm, please email [email protected] or call us at 610-235-2690 for further information.

Saturday & Sunday, please contact [email protected]

Memorial Day reflection: Vietnam was a…

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Things To Do

- Classifieds

- Special Sections

Latest Headlines

Memorial day reflection: vietnam was a different war in so many ways.

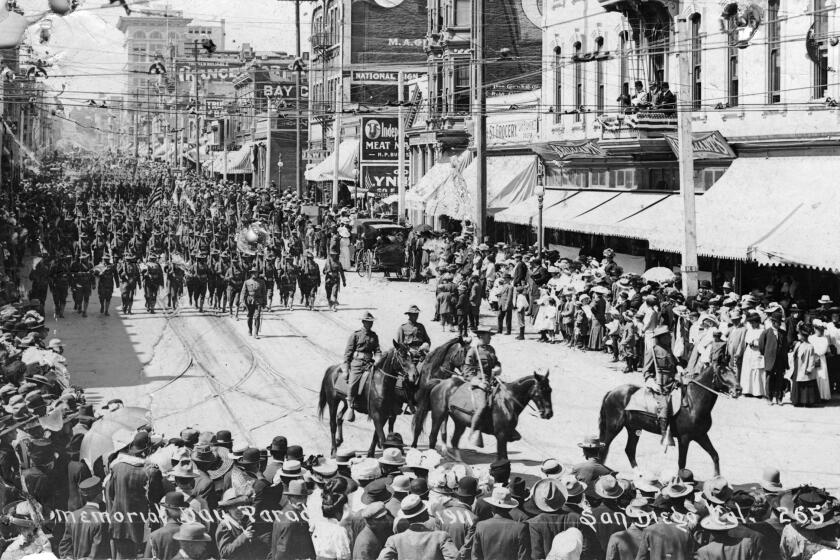

Vietnam was one of the longest wars of the 20th century, for America lasting from 1959-75.

The cost of human suffering was monumental and difficult to calculate. In what was then called South Vietnam, the war produced an estimated seven million displaced persons, and two million Vietnamese casualties.

And no one should forget the 58,000 Americans who were killed, the 300,000 seriously wounded, and the thousands still listed as “missing in action.”

Among other miasmic effects, the war had a profound impact on American culture and politics. Only now, after decades of avoidance, repression and silence, Americans have finally come to terms with this war which deeply divided our nation for years.

However, it was a different kind of war. Politically, militarily and in its outcome, Vietnam didn’t resemble what I learned in school about America’s other wars.

Bloody events, which included the coordinated attacks that occurred throughout South Vietnam as part of the Tet (New Year) offensive of 1968; the My Lai massacre of March 1968; and the Kent State shootings in 1970 also contributed to making it a different war.

Vietnam was a different war in a helicopter or an F-4 Phantom jet, or a B-52 bomber. Different in the Delta, the Highlands, near the DMZ, Laos or Cambodia.

It was different on the rivers, in the mud, in field hospitals, on ships in the South China Sea.

It was a different war for women, the seven thousand American women, mostly nurses, who volunteered to care for those doing the fighting.

And the eight women who died and whose names are inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Today it is remembered as a different war in its physical and emotional aftermath. For Americans and Vietnamese suffering from Agent Orange absorbed decades ago.

For the Vietnamese, Laotians and Cambodians still affected from exposure to toxic chemicals and unexploded ordnance left behind.

Finally, it is remembered today as a different war than it was 50 or 60 years years ago — for those who cannot forget it whether they were in Vietnam or not. Memorial Day’s significance, however, is in the hearts and minds of veterans and the families of veterans who are counted among the war’s casualties.

Especially each year on the observance of Memorial Day.

Ira Cooperman, a resident of Wyncote, served as an Air Force intelligence officer in the Vietnam War from 1965-66. His email address is: [email protected]

More in Opinion

Faith Matters: ‘God is the source of all life’s blessings’

Business | PERSONAL FINANCE: How to tell if your risk tolerance has changed over time

Letter to editor: North Penn School District issues rooted in Harrisburg failures

Business | PLANNING AHEAD: Simple wills often can tackle complex personal issues

This Day in History: Donald Ross, hero of Pearl Harbor

On this day in 1992, a hero passes away. Donald K. Ross was the first sailor to receive a Medal of Honor during World War II. At the time of his passing, he was also the oldest living recipient of the Medal.

Ross was serving in Pearl Harbor when the Japanese launched their surprise attack of December 7, 1941 . He was then a machinist mate aboard USS Nevada , but would you believe he wasn’t even supposed to be aboard Nevada that Sunday?

Indeed, his then-girlfriend (future wife) Helen was a bit upset with him for returning to the ship on Saturday night, the 6th. His birthday was Monday, so she’d planned a surprise Sunday birthday picnic. He was not on duty and should have been free to go.

“He insisted he needed to get back,” she later remembered. “He said he just had a feeling that he should be with the ship.”

Helen dropped him off that evening, just as it was getting dark. She would later remember an officer giving Ross orders. “He was to make sure he kept the boilers on the Nevada up and running through the night,” Helen explained. “A lot of the ships didn’t. They shut down on the weekends.”

Other reports say that one boiler was running, but an officer wanted to start a second so a switch could be made later. Either way, at least two boilers were running on the night of December 6-7, which proved important.

Ross remembers the attack early that Sunday morning. “I was shaving when it happened,” he explained. “But I stopped right then and there. We were prepared. We knew that a war was coming. We didn’t know it was then. We were all surprised.”

He ran to the engine room, prepared to do what was needed.

“[The story of] the daring rump crew that fought [on Nevada ] so gallantly,” Commander Jack D. Bruce observes, “during the 7 December 1941 surprise Japanese attack . . . has never been fully or accurately told. The stories are often inaccurate and sometimes misleading. Unlike her sister ships along Battleship Row that distant morning, the Nevada got under way, making a dramatic dash for the open sea despite a gaping torpedo wound in her port bow and bomb damage elsewhere.”

Which officers were in charge when? No one is sure. Nevertheless, a few facts are indisputable: First, Nevada had an extra boiler running, which proved vital in getting the engines up and running so quickly. Second, Ross played a critical role in the moments that followed.

He simply would not abandon his post in the engine room.

As he worked, he passed out from smoke inhalation, was resuscitated, then went back. He blacked out a second time and was resuscitated before returning yet again. On this third trip, a rope was tied around his chest so he could be pulled out of the engine room, as needed.

They had to have been assuming he’d pass out a third time.

It was enough. Nevada ’s engines roared to life, and she got underway in about 45 minutes—an unbelievable feat. As Nevada made her run for the open sea, she also cleared the way for other Navy ships to get out of the harbor.

When the dust had settled, Ross should have been hospitalized immediately, but he refused to go. Instead, he stayed to help with the evacuation and rescue of others. When he was finally hospitalized, it took three weeks for his eyesight to return to normal.

A few months later, Ross became the first sailor to receive the Medal of Honor. Naturally, he didn’t think he deserved it.

“I don’t know what all this fuss is about,” one officer remembers Ross saying decades later. “I’m just a poor Navy man who has always tried to do his duty. I love this country like I love my own family. God bless America.”

Enjoyed this post? More Medal of Honor

stories can be found on my website, HERE.

Primary Sources:

Commander Jack D. Bruce, U.S. Navy (Retired), The Enigma of Battleship Nevada (Naval History Magazine; Dec. 1991)

Donald Ross: Pearl Harbor Hero Honored by His Friends (Kitsap Sun; June 3, 1992) ( p. A1 )

Jackie Fitzpatrick, The Crew of the First Nevada Relives World War II Exploits (The Day; Sept. 15, 1985) ( p. A3 )

Medal of Honor citation ( Donald Kirby Ross; WWII )

Nevada Crewmen Visit for Ross Ceremony (Galveston Daily News; June 26, 1997) ( p. A1 )

New Destroyer Bears Proud Kansas Name (Wichita Eagle; May 26, 1997) ( p. A1 )

Obituaries: Donald Ross Won 1st World War II Medal of Honor (Indianapolis Star; June 1, 1992) ( p. C6 )

The Saga of the USS Nevada (Nevada Mag.; July – August 2014)

World War II Dispatch: Medal of Honor Recipient Buried at Sea (Department of Defense; Winter 1993) ( p. 18 )

- Medal of Honor

- World War II

Kommentarer

- Ancient History

Symposia: When ancient Greeks got drunk and argued about philosophy

In Athens , during the 5th century BCE, there were held lavish banquets that brought together the elite members of society where they would share ideas, drink wine, and enjoy various entertainments.

These events were called the symposium , and they even became a melting pot of philosophical discourse. Participants included poets, philosophers, and politicians, who were all eager to dazzle each other with their wit and wisdom.

However, with wine flowing freely, the atmosphere sometimes turned raucous and violent...

What was the ancient Greek symposium?

Historians date the earliest develop of the symposium to the early Archaic period in Greece, around the 7th century BCE.

These original gatherings were probably simple drinking parties or social gatherings involving eating together as a community.

By the 6th century BCE, they had become a key fixture in the lives of the Greek elite. For the participants, the symposium was an opportunity to build and strengthen social networks.

By bringing together influential individuals, it reinforced social hierarchies and alliances.

Due to its increased importance, the symposium also became a way to educate and initiate young men into the values and traditions of their society.

At these events, older and more experienced members of the community were expected to impart practical guidance to the younger participants.

This kind of mentorship helped maintain the continuity of certain cultural traditions.

What would happen at a Greek symposium?

The symposium typically took place in the men's dining room of a wealthy Greek household, known as the andron . This room was designed specifically for these gatherings, with couches arranged around the perimeter for guests to recline while eating and drinking.

In Athens, many androns were elaborately decorated with mosaics and paintings, as a way of demonstrating the host's wealth and taste.

The layout of the andron was designed to specifically facilitate conversation and interaction among the participants.

To begin, the symposium usually started with a meal called the deipnon . During this part of the evening, guests enjoyed a variety of foods, often served on small tables placed in front of each couch.

Common foods included olives, cheeses, and bread, accompanied by more elaborate dishes such as roasted meats and fish.

In many gatherings, the quality and diversity of the food reflected the status and generosity of the host.

Following the meal, the focus shifted to drinking, which was the central activity of the symposium. In the middle of the room, a large mixing bowl, or krater , was used to mix wine with water.

This practice distinguished Greek drinking customs from those of their neighbors, who often drank wine undiluted.

Consequently, the careful mixing of wine was considered a mark of civilization and moderation.

Greek symposia typically featured wines from renowned regions like Chios, Lesbos, and Thasos. These wines were often flavored with herbs and spices to enhance their taste.

Besides wine, the symposium included other beverages like kykeon, a mixed drink made from barley, water, and herbs.

This variety of drinks provided guests with different options to suit their preferences and added to the overall enjoyment of the evening.

For entertainment, musicians and entertainers performed for the guests. Sometimes, professional musicians were hired, while at other times, guests themselves would sing or recite poetry themselves.

Philosophers like Socrates often used these occasions to engage others in stimulating debates. Additionally, the symposium included a range of desserts and after-dinner treats.

Fruits such as figs, grapes, and pomegranates were common, along with honey cakes and pastries. The setting of the symposium, with its intimate and relaxed environment, encouraged open exchange of ideas.

Who was allowed to attend?

Participants in the symposium were typically drawn from the male aristocracy of Greek society. These gatherings included influential figures such as politicians, philosophers, and wealthy landowners.

In Athens, notable individuals like Pericles and Alcibiades attended symposia to discuss politics. By participating in these events, they reinforced their social status and built important networks.

The exclusion of women, except for entertainers and courtesans, was an unfortunate part of the male-dominated nature of wider Athenian culture.

As mentioned before, musicians, dancers, and courtesans provided amusement and diversion for the guests. Among them, the hetairai , or courtesans, were often highly educated and skilled in conversation.

Figures like Aspasia , the companion of Pericles, were known for their intelligence and wit at such events. Consequently, these women would have the freedom to engage in the intellectual discussions, which was denied to almost all other women.

The strange rituals performed at a symposium

Unlike modern parties, the symposium had a religious element, which included a series of rituals that established a formal tone.

One of the initial acts was the libation. This ritual, called the spondai , involved a ceremonial pouring of wine mixed with water onto the ground or an altar in honor of the gods.

It was thought that by doing this, the attendees would receive divine favor and protection for the evening. Guests would then enjoy the performances of the musicians and dancers.