The Story of An Hour - Study Guide

Kate Chopin 's The Story of An Hour (1894) is considered one of the finest pieces of Feminist Literature. We hope that our study guide is particularly useful for teachers and students to get the most from the story and appreciate its boldness shaking up the literary community of its time.

Here's the story: The Story of An Hour , Character Analysis & Summary , Genre & Themes , Historical Context , Quotes , Discussion Questions , Useful Links , and Notes/Teacher Comments

Character Analysis & Summary

Plot Summary : Chopin basically summarizes the external events of the story in the first sentence: "Knowing that Mrs. Mallard was afflicted with a heart trouble, great care was taken to break to her as gently as possible the news of her husband's death."

Genre & Themes

Challenge Social Conventions : Rather than conform to what's expected, honor your own needs. Just because it's the way it's always been, doesn't mean it has to continue at your expense.

Situational Irony : Life's a bitch-- just when you think you're free from obligation, you go and die yourself, which kind of makes liberation a bit pointless. Chopin's story is a great example of the literary device called situational irony .

Historical Context

Feminist literature, both fiction and non-fiction, supports feminist goals for the equal rights of women in their economic, social, civic, and political status relative to men. Such literature dates back to the 15th century (The Tale of Joan of Arc by Christine de Pisan), Mary Wollstonecraft in the 18th century, Virginia Woolf , Elizabeth Cady Stanton , Florence Nightingale , Elizabeth Perkins Gilman , and Louisa May Alcott . Kate Chopin 's best known novel, The Awakening (1899) and Mary E. Wilkins Freeman 's A New England Nun (1891) led the emerging modern feminist literary movement into the 20th century, during which women earned the right to vote, fought for economic, social, political, educational, and reproductive rights with Gloria Steinem and the Women's Liberation Movement. The 21st century has brought a resurgence of interest in Margaret Atwood 's The Handmaid's Tale with a new streaming video series , and the Women's March After President Trump's Inauguration (2017) drew more than a million protesters in cities throughout the country and world.

It's helpful to know the list of grievances and demands a group of activitists (mostly women) published in The Declaration of Sentiments in 1848. Principal author and first women's conference organizer was Elizabeth Cady Stanton , with high-profile support from abolitionist Frederick Douglass . Many more struggles and attempts to change public opinion followed the conference; it took 72 more years for women to secure the right to vote.

A brief History of Feminism

“Knowing that Mrs. Mallard was afflicted with a heart trouble, great care was taken to break to her as gently as possible the news of her husband's death."

“She did not hear the story as many women have heard the same, with a paralyzed inability to accept its significance."

“When the storm of grief had spent itself she went away to her room alone. She would have no one follow her."

“She was beginning to recognize this thing that was approaching to possess her, and she was striving to beat it back with her will--as powerless as her two white slender hands would have been."

"'Free, free, free!'' The vacant stare and the look of terror that had followed it went from her eyes. They stayed keen and bright."

"What could love, the unsolved mystery, count for in the face of this possession of self-assertion which she suddenly recognized as the strongest impulse of her being!"

"When the doctors came they said she had died of heart disease--of the joy that kills."

Discussion Questions

9. Elaborate on Chopin's uses of irony: 1) Situational Irony : when she gets her freedom, she dies anyway 2) Verbal irony : What is said explicitly is much different than the text's inferences (thinking rather than saying). Reacting to news of a spouse's death with relief, nevermind "monstrous joy" is an "inappropriate" response, for sure. She keeps these thoughts in her head (whispering her chant), with the door closed.

10. Discuss the concept of repression and Chopin's assertion of her real cause of death: "the joy that kills."

11. Read Chopin's allegory about freedom from a cage, her short-short story, Emancipation: A Life Fable . Compare its theme, tone, symbols, and use of irony to this story.

Essay Prompt : Tell the same story from Josephine's point of view (remember, Louisa keeps her door shut most of the time).

Essay Prompt : Consider reading the one act play by Susan Glaspell , Trifles (1916), about a murder trial which challenges our perceptions of justice and morality. Compare it to Chopin's The Story of An Hour

Essay Prompt : Read Kate Chopin 's biography (feel free to extend your research to other sources). How does her personal story reflect her writing?

Useful Links

Biography and Works by Kate Chopin

American Literature's biographies of featured Women Writers

ELA Common Core Lesson plan ideas for "The Story of An Hour"

Veiled Hints and Irony in Chopin's "The Story of An Hour"

Feminist Approaches to Literature , read more about the genre

Kate Chopin's "The Awakening": Searching for Women & Identity

KateChopin.org's biography and assessment of her work

Is It Actually Ironic? TED-Ed lessons on irony

Notes/Teacher Comments

Visit our Teacher Resources , supporting literacy instruction across all grade levels

American Literature's Study Guides

'The Story of an Hour' Questions for Study and Discussion

Kate Chopin's Famous Short Story

David Madison/Getty Images

- Study Guides

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., English Literature, California State University - Sacramento

- B.A., English, California State University - Sacramento

" The Story of an Hour " is one of the greatest works by Kate Chopin.

Mrs. Mallard has a heart condition, which means that if she's startled she could die. So, when news comes that her husband's been killed in an accident, the people who tell her have to cushion the blow. Mrs. Mallard's sister Josephine sits down with her and dances around the truth until Mrs. Mallard finally understands what happened. The deceased Mr. Mallard's friend, Richards, hangs out with them for moral support.

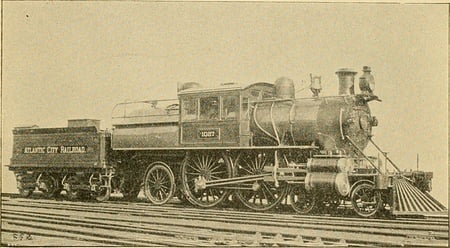

Richards originally found out because he had been in the newspaper headquarters when a report of the accident that killed Mr. Mallard, which happened on a train, came through. Richards waited for proof from a second source before going to the Mallards' to share the news.

When Mrs. Mallard finds out what happened she acts differently from most women in the same position, who might disbelieve it. She cries passionately before deciding to go to her room to be by herself.

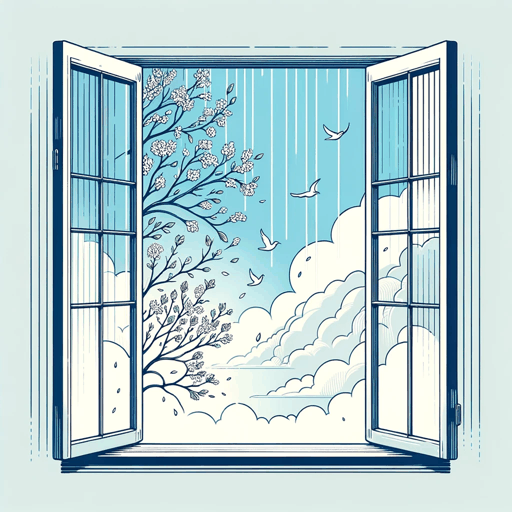

In her room, Mrs. Mallard sits down on a comfy chair and feels completely depleted. She looks out the window and looks out at a world that seems alive and fresh. She can see the sky coming between the rain clouds .

Mrs. Mallard sits still, occasionally crying briefly like a kid might. The narrator describes her as youthful and pretty, but because of this news she looks preoccupied and absent. She seems to be holding out for some kind of unknown news or knowledge, which she can tell is approaching. Mrs. Mallard breathes heavily and tries to resist before succumbing to this unknown thing, which is a feeling of freedom.

Acknowledging freedom makes her revive, and she doesn't consider whether she should feel bad about it. Mrs. Mallard thinks to herself about how she'll cry when she sees her husband's dead body and how much he loved her. Even so, she's kind of excited about the chance to make her own decisions and not feel accountable to anyone.

Mrs. Mallard feels even more swept up by the idea of freedom than the fact that she had felt love for her husband. She focuses on how liberated she feels. Outside the locked door to the room, her sister Josephine is pleading to her to open up and let her in. Mrs. Mallard tells her to go away and fantasizes about the exciting life ahead. Finally, she goes to her sister and they go downstairs.

Suddenly, the door opens and Mr. Mallard comes in. He's not dead and doesn't even know anyone thought he was. Even though Richards and Josephine try to protect Mrs. Mallard from the sight, they can't. She receives the shock they tried to prevent at the beginning of the story. Later, the medical people who examine her say that she was full of so much happiness that it murdered her.

Study Guide Questions

- What is important about the title?

- What are the conflicts in "The Story of an Hour"? What types of conflict (physical, moral, intellectual, or emotional) do you see in this story?

- How does Kate Chopin reveal character in "The Story of an Hour"?

- What are some themes in the story? How do they relate to the plot and characters?

- What are some symbols in "The Story of an Hour"? How do they relate to the plot and characters?

- Is Mrs. Millard consistent in her actions? Is she a fully developed character? How? Why?

- Do you find the characters likable? Would you want to meet the characters?

- Does the story end the way you expected? How? Why?

- What is the central/primary purpose of the story? Is the purpose important or meaningful?

- Why is the story usually considered a work of feminist literature?

- How essential is the setting to the story? Could the story have taken place anywhere else?

- What is the role of women in the text? What about single/independent women?

- Would you recommend this story to a friend?

- "The Story of an Hour" Characters

- Quotes From 'The Story of an Hour' by Kate Chopin

- Analysis of "The Story of an Hour" by Kate Chopin

- 'The Awakening' Quotes

- 'Wuthering Heights' Questions for Study and Discussion

- 'A Rose for Emily' Questions for Study and Discussion

- Jane Eyre Study Guide

- 'The Yellow Wallpaper' Questions for Study

- Kate Chopin's 'The Storm': Quick Summary and Analysis

- 'The Devil and Tom Walker' Study Guide

- Biography of Kate Chopin, American Author and Protofeminist

- 'Invisible Man' Questions for Study and Discussion

- Analysis of Flannery O'Connor's 'Good Country People'

- Discussion Questions for Pride and Prejudice

- Analysis of 'The Yellow Wallpaper' by C. Perkins Gilman

- 'Their Eyes Were Watching God' Summary

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

116 The Story of an Hour Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

The Story of an Hour by Kate Chopin is a short but powerful story that explores the complexities of marriage, freedom, and self-discovery. With its rich themes and thought-provoking narrative, this classic piece of literature has inspired countless essays and discussions. If you're looking for essay topic ideas and examples for The Story of an Hour, you've come to the right place. Here are 116 essay topics to help you get started:

- Analyze the character of Mrs. Mallard and how she evolves throughout the story.

- Explore the theme of freedom in The Story of an Hour.

- Discuss the role of marriage in the story and how it impacts the characters.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's emotions before and after learning of her husband's death.

- Examine the use of irony in the story and how it contributes to the overall theme.

- Discuss the significance of the title "The Story of an Hour" and how it relates to the plot.

- Analyze the symbolism of the open window in the story.

- Explore the theme of female independence in The Story of an Hour.

- Discuss the role of societal expectations in the story and how they influence the characters' actions.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's reaction to her husband's death with that of other characters in the story.

- Analyze the significance of the setting in The Story of an Hour.

- Discuss the theme of repression in the story and how it affects the characters' relationships.

- Explore the theme of mortality in The Story of an Hour.

- Discuss the role of gender in the story and how it shapes the characters' experiences.

- Analyze the use of foreshadowing in The Story of an Hour.

- Discuss the theme of self-discovery in the story and how it impacts the characters' development.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's reaction to her husband's death with that of society's expectations.

- Analyze the symbolism of the heart trouble in the story.

- Discuss the theme of isolation in The Story of an Hour.

- Explore the theme of rebirth in the story and how it relates to Mrs. Mallard's journey.

- Analyze the role of communication in the story and how it affects the characters' relationships.

- Discuss the theme of empowerment in The Story of an Hour.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's reaction to her husband's death with that of her sister's.

- Analyze the role of denial in the story and how it influences the characters' actions.

- Discuss the theme of time in The Story of an Hour.

- Explore the theme of grief in the story and how it impacts the characters' emotions.

- Analyze the symbolism of the railroad in the story.

- Discuss the theme of liberation in The Story of an Hour.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's reaction to her husband's death with that of her friend's.

- Analyze the role of symbolism in the story and how it enhances the narrative.

- Discuss the theme of identity in The Story of an Hour.

- Explore the theme of fate in the story and how it influences the characters' choices.

- Analyze the symbolism of the staircase in the story.

- Discuss the theme of transformation in The Story of an Hour.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's reaction to her husband's death with that of her mother's.

- Analyze the role of foils in the story and how they contribute to the characters' development.

- Discuss the theme of betrayal in The Story of an Hour.

- Explore the theme of forgiveness in the story and how it impacts the characters' relationships.

- Analyze the symbolism of the storm in the story.

- Discuss the theme of redemption in The Story of an Hour.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's reaction to her husband's death with that of her father's.

- Analyze the role of irony in the story and how it enhances the narrative.

- Discuss the theme of sacrifice in The Story of an Hour.

- Explore the theme of perspective in the story and how it influences the characters' perceptions.

- Analyze the symbolism of the caged bird in the story.

- Discuss the theme of acceptance in The Story of an Hour.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's reaction to her husband's death with that of her neighbors'.

- Explore the theme of choice in the story and how it impacts the characters' decisions.

- Analyze the symbolism of the garden in the story.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's reaction to her husband's death with that of her colleagues'.

- Analyze the role of foreshadowing in the story and how it contributes to the overall theme.

- Explore the theme of self-discovery in the story and how it impacts the characters' development.

- Analyze the symbolism of the mirror in the story.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's reaction to her husband's death with that of her classmates'.

- Discuss the theme of mortality in The Story of an Hour.

- Discuss the theme of female independence in The Story of an Hour.

- Explore the theme of repression in the story and how it affects the characters' relationships.

- Discuss the theme of freedom in The Story of an Hour.

- Explore the role of marriage in the story and how it impacts the characters.

- Analyze the use of irony in the story and how it contributes to the overall theme.

- Discuss the significance of the setting in The Story of an Hour.

- Analyze the role of marriage in the story and how it impacts the characters.

- Analyze the significance of the title "The Story of an Hour" and how it relates to the plot.

- Compare and contrast Mrs. Mallard's reaction to

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

The Story of an Hour Critical Analysis Essay

Looking for a critical analysis of The Story of an Hour ? The essay on this page contains a summary of Kate Chopin’s short story, its interpretation, and feminist criticism. Find below The Story of an Hour critique together with the analysis of its characters, themes, symbolism, and irony.

Introduction

Works cited.

The Story of an Hour was written by Kate Chopin in 1984. It describes a woman, Mrs. Mallard, who lost her husband in an accident, but later the truth came out, and the husband was alive. This essay will discuss The Story of an Hour with emphasis on the plot and development of the protagonist, Mrs. Mallard, who goes through contrasting emotions and feelings that finally kill her on meeting her husband at the door, yet he had been said to be dead.

The Story of an Hour Summary

Kate Chopin narrated the story of a woman named Mrs. Mallard who had a heart health problem. One day the husband was mistaken to have died in an accident that occurred. Due to her heart condition, her sister had to take care while breaking the bad news to her. She was afraid that such news of her husband’s death would cost her a heart attack. She strategized on how to break the news to her sister bit by bit, which worked perfectly well. Mrs. Mallard did not react as expected; instead, she started weeping just once.

She did not hear the story as many women have had the same with a paralyzed inability to accept its significance. She wept once, with sudden, wild abandonment, in her sister’s arms (Woodlief 2).

Mrs. Mallard wondered how she would survive without a husband. She went to one room and locked herself alone to ponder what the death of her husband brought to her life. She was sorrowful that her husband had died, like it is human to be sad at such times. This is someone very close to her, but only in a short span of time was no more. This sudden death shocked her. Her sister Josephine and friends Mr. Richard and Louise are also sorry for the loss (Taibah 1).

As she was in that room alone, she thought genuinely about the future. Unexpectedly, she meditated on her life without her husband. Apart from sorrow, she started counting the better part of her life without her husband. She saw many opportunities and freedom to do what she wanted with her life. She believed that the coming years would be perfect for her as she only had herself to worry about. She even prayed that life would be long.

After some time, she opened the door for Josephine, her sister, who had a joyous face. They went down the stairs of the house, and Mr. Mallard appeared as he opened the gate. Mr. Mallard had not been involved in the accident and could not understand why Josephine was crying. At the sight of her husband, Mr. Mallard, his wife, Mrs. Mallard, collapsed to death. The doctors said that she died because of heart disease.

The Story of an Hour Analysis

Mrs. Mallard was known to have a heart problem. Richard, who is Mr. Mallard’s friend, was the one who learned of Mr. Mallard’s death while in the office and about the railroad accident that killed him. They are with Josephine, Mrs. Mallard’s sister, as she breaks the news concerning the sudden death of her husband. The imagery clearly describes the situation.

The writer brought out the suspense in the way he described how the news was to be broken to a person with a heart problem. There is a conflict that then follows in Mrs. Mallard’s response which becomes more complicated. The death saddens Mrs. Mallard, but, on the other hand, she counts beyond the bitter moments and sees freedom laid down for her for the rest of her life. The description of the room and the environment symbolize a desire for freedom.

This story mostly focuses on this woman and a marriage institution. Sad and happy moments alternate in the protagonist, Mrs. Mallard. She is initially sad about the loss of her husband, then in a moment, ponders on the effects of his death and regains strength.

Within a short period, she is shocked by the sight of her husband being alive and even goes to the extreme of destroying her life. She then dies of a heart attack, whereas she was supposed to be happy to see her husband alive. This is an excellent contrast of events, but it makes the story very interesting.

She could see in the open square before her house the tops of trees that were all aquiver with the new spring life. The delicious breath of rain was in the air. In the street below, a peddler was crying his wares. The notes of a distant song that someone was singing reached her faintly, and countless sparrows were twittering in the eaves. There were patches of blue sky showing here and there through the clouds that had met and piled one above the other in the west facing her window (Woodlief 1).

Therefore, an open window is symbolic. It represents new opportunities and possibilities that she now had in her hands without anyone to stop her, and she refers to it as a new spring of life.

She knew that she was not in a position to bring her husband back to life.

Her feelings were mixed up. Deep inside her, she felt that she had been freed from living for another person.

She did not stop to ask if it were or were not a monstrous joy that held her… She knew that she would weep again when she saw the kind, tender hands folded in death, the face that had never looked save with love upon her, fixed and gray and dead (Sparknotes 1).

The author captured a marriage institution that was dominated by a man. This man, Mr. Mallard, did not treat his wife as she would like (the wife) at all times, only sometimes. This Cleary showed that she was peaceful even if her husband was dead. Only some sorrow because of the loss of his life but not of living without him. It seemed that she never felt the love for her husband.

And yet she had loved him sometimes. Often she had not. What did it matter! What could love the unsolved mystery, count for in the face of this procession of self-assertion which she suddenly recognized as the strongest impulse of her being! (Woodlief 1).

How could a wife be peaceful at the death of her husband? Though people thought that she treasured her husband, Mr. Mallard, so much and was afraid that she would be stressed, she did not see much of the bitterness like she found her freedom. This reveals how women are oppressed in silence but never exposed due to other factors such as wealth, money, and probably outfits.

As much as wealth is essential, the characters Mr. and Mrs. Mallard despise the inner being. Their hearts were crying amid a physical smile: “Free! Body and soul free!”…Go away. I am not making myself ill.” No; she was drinking in a very elixir of life through that open window” (Woodlief 1).

In this excerpt, Mrs. Mallard knows what she is doing and believes that she is not harming herself. Instead, she knew that though the husband was important to her, marriage had made her a subject to him. This was not in a positive manner but was against her will. It seems she had done many things against her will, against herself, but to please her husband.

Mrs. Mallard’s character is therefore developed throughout this story in a short time and reveals many values that made her what she was. She is a woman with a big desire for freedom that was deprived by a man in marriage. She is very emotional because after seeing her freedom denied for the second time by her husband, who was mistaken to have died, she collapses and dies. The contrast is when the writer says, “She had died of heart disease…of the joy that kills” (Woodlief 1).

Mrs. Mallard was not able to handle the swings in her emotions, and this cost her life. Mr. Mallard was left probably mourning for his wife, whom he never treasured. He took her for granted and had to face the consequences. Oppressing a wife or another person causes a more significant loss to the oppressor. It is quite ironic that Mr. Mallard never knew that his presence killed his wife.

Sparknotes. The Story of an Hour. Sparknotes, 2011. Web.

Taibah. The Story of an Hour. Taibah English Forum, 2011. Web.

Woodlief. The story of an hour . VCU, 2011. Web.

Further Study: FAQ

📌 who is the protagonist in the story of an hour, 📌 when was the story of an hour written, 📌 what is the story of an hour about, 📌 what is the conclusion the story of an hour.

- The Story of an Hour by Kate Chopin

- Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour”

- Protagonists in Literature

- Symbolism in the "Death of a Salesman" by Arthur Miller

- The Other Wes Moore

- Henry David Thoreau: The Maine Woods, Walden, Cape Cod

- Analysis of “The Dubious Rewards of Consumption”

- Moral Dilemma’s in the Breakdown 1968 and the Missing Person

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 12). The Story of an Hour Critical Analysis Essay. https://ivypanda.com/essays/critical-analysis-of-the-story-of-an-hour/

"The Story of an Hour Critical Analysis Essay." IvyPanda , 12 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/critical-analysis-of-the-story-of-an-hour/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The Story of an Hour Critical Analysis Essay'. 12 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The Story of an Hour Critical Analysis Essay." October 12, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/critical-analysis-of-the-story-of-an-hour/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Story of an Hour Critical Analysis Essay." October 12, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/critical-analysis-of-the-story-of-an-hour/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Story of an Hour Critical Analysis Essay." October 12, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/critical-analysis-of-the-story-of-an-hour/.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the story of an hour: summary and analysis.

General Education

Imagine a world where women are fighting for unprecedented rights, the economic climate is unpredictable, and new developments in technology are made every year. While this world might sound like the present day, it also describes America in the 1890s .

It was in this world that author Kate Chopin wrote and lived, and many of the issues of the period are reflected in her short story, “The Story of an Hour.” Now, over a century later, the story remains one of Kate Chopin’s most well-known works and continues to shed light on the internal struggle of women who have been denied autonomy.

In this guide to Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour,” we’ll discuss:

- A brief history of Kate Chopin and America the 1890s

- “The Story of an Hour” summary

- Analysis of the key story elements in “The Story of an Hour,” including themes, characters, and symbols

By the end of this article, you’ll have an expert grasp on Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour.” So let’s get started!

“The Story of an Hour” Summary

If it’s been a little while since you’ve read Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour,” it can be hard to remember the important details. This section includes a quick recap, but you can find “The Story of an Hour” PDF and full version here . We recommend you read it again before diving into our analyses in the next section!

For those who just need a refresher, here’s “The Story of an Hour” summary:

Mrs. Louise Mallard is at home when her sister, Josephine, and her husband’s friend, Richards, come to tell her that her husband, Brently Mallard, has been killed in a railroad accident . Richards had been at the newspaper office when the news broke, and he takes Josephine with him to break the news to Louise since they’re afraid of aggravating her heart condition. Upon hearing the news of her husband’s death, Louise is grief-stricken, locks herself in her room, and weeps.

From here, the story shifts in tone. As Louise processes the news of her husband’s death, she realizes something wonderful and terrible at the same time: she is free . At first she’s scared to admit it, but Louise quickly finds peace and joy in her admission. She realizes that, although she will be sad about her husband (“she had loved him—sometimes,” Chopin writes), Louise is excited for the opportunity to live for herself. She keeps repeating the word “free” as she comes to terms with what her husband’s death means for her life.

In the meantime, Josephine sits at Louise’s door, coaxing her to come out because she is worried about Louise’s heart condition. After praying that her life is long-lived, Louise agrees to come out. However, as she comes downstairs, the front door opens to reveal her husband, who had not been killed by the accident at all. Although Richards tries to keep Louise’s heart from shock by shielding her husband from view, Louise dies suddenly, which the doctors later attribute to “heart disease—of the joy that kills .”

Kate Chopin, the author of "The Story of an Hour," has become one of the most important American writers of the 19th century.

The History of Kate Chopin and the 1890s

Before we move into “The Story of an Hour” analysis section, it’s helpful to know a little bit about Kate Chopin and the world she lived in.

A Short Biography of Kate Chopin

Born in 1850 to wealthy Catholic parents in St. Louis, Missouri, Kate Chopin (originally Kate O’Flaherty) knew hardship from an early age. In 1855, Chopin lost her father, Thomas, when he passed away in a tragic and unexpected railroad accident. The events of this loss would stay with Kate for the rest of her life, eventually becoming the basis for “The Story of an Hour” nearly forty years later.

Chopin was well-educated throughout her childhood , reading voraciously and becoming fluent in French. Chopin was also very aware of the divide between the powerful and the oppressed in society at the time . She grew up during the U.S. Civil War, so she had first-hand knowledge of violence and slavery in the United States.

Chopin was also exposed to non-traditional roles for women through her familial situation. Her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother chose to remain widows (rather than remarry) after their husbands died. Consequently, Chopin learned how important women’s independence could be, and that idea would permeate much of her writing later on.

As Chopin grew older, she became known for her beauty and congeniality by society in St. Louis. She was married at the age of nineteen to Oscar Chopin, who came from a wealthy cotton-growing family. The couple moved to New Orleans, where they would start both a general store and a large family. (Chopin would give birth to seven children over the next nine years!)

While Oscar adored his wife, he was less capable of running a business. Financial trouble forced the family to move around rural Louisiana. Unfortunately, Oscar would die of swamp fever in 1882 , leaving Chopin in heavy debt and with the responsibility of managing the family’s struggling businesses.

After trying her hand at managing the property for a year, Chopin conceded to her mother’s requests to return with her children to St. Louis. Chopin’s mother died the year after. In order to support herself and her children, Kate began to write to support her family.

Luckily, Chopin found immediate success as a writer. Many of her short stories and novels—including her most famous novel, The Awakening— dealt with life in Louisiana . She was also known as a fast and prolific writer, and by the end of the 1900s she had written over 100 stories, articles, and essays.

Unfortunately, Chopin would pass away from a suspected cerebral hemorrhage in 1904, at the age of 54 . But Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” and other writings have withstood the test of time. Her work has lived on, and she’s now recognized as one of the most important American writers of the 19th century.

American life was undergoing significant change in the 19th century. Technology, culture, and even leisure activities were changing.

American Life in the 1890s

“The Story of an Hour” was written and published in 1894, right as the 1800s were coming to a close. As the world moved into the new century, American life was also changing rapidly.

For instance, t he workplace was changing drastically in the 1890s . Gone were the days where most people were expected to work at a trade or on a farm. Factory jobs brought on by industrialization made work more efficient, and many of these factory owners gradually implemented more humane treatment of their workers, giving them more leisure time than ever.

Though the country was in an economic recession at this time, technological changes like electric lighting and the popularization of radios bettered the daily lives of many people and allowed for the creation of new jobs. Notably, however, work was different for women . Working women as a whole were looked down upon by society, no matter why they found themselves in need of a job.

Women who worked while they were married or pregnant were judged even more harshly. Women of Kate Chopin’s social rank were expected to not work at all , sometimes even delegating the responsibility of managing the house or child-rearing to maids or nannies. In the 1890s, working was only for lower class women who could not afford a life of leisure .

In reaction to this, the National American Woman Suffrage Association was created in 1890, which fought for women’s social and political rights. While Kate Chopin was not a formal member of the suffragette movements, she did believe that women should have greater freedoms as individuals and often talked about these ideas in her works, including in “The Story of an Hour.”

Kate Chopin's "The Story of an Hour" a short exploration of marriage and repression in America.

“The Story of an Hour” Analysis

Now that you have some important background information, it’s time to start analyzing “The Story of an Hour.”

This short story is filled with opposing forces . The themes, characters, and even symbols in the story are often equal, but opposite, of one another. Within “The Story of an Hour,” analysis of all of these elements reveals a deeper meaning.

“The Story of an Hour” Themes

A theme is a message explored in a piece of literature. Most stories have multiple themes, which is certainly the case in “The Story of an Hour.” Even though Chopin’s story is short, it discusses the thematic ideas of freedom, repression, and marriage.

Keep reading for a discussion of the importance of each theme!

Freedom and Repression

The most prevalent theme in Chopin’s story is the battle between freedom and “repression.” Simply put , repression happens when a person’s thoughts, feelings, or desires are being subdued. Repression can happen internally and externally. For example, if a person goes through a traumatic accident, they may (consciously or subconsciously) choose to repress the memory of the accident itself. Likewise, if a person has wants or needs that society finds unacceptable, society can work to repress that individual. Women in the 19th century were often victims of repression. They were supposed to be demure, gentle, and passive—which often went against women’s personal desires.

Given this, it becomes apparent that Louise Mallard is the victim of social repression. Until the moment of her husband’s supposed death, Louise does not feel free . In their marriage, Louise is repressed. Readers see this in the fact that Brently is moving around in the outside world, while Louise is confined to her home. Brently uses railroad transportation on his own, walks into his house of his own accord, and has individual possessions in the form of his briefcase and umbrella. Brently is even free from the knowledge of the train wreck upon his return home. Louise, on the other hand, is stuck at home by virtue of her position as a woman and her heart condition.

Here, Chopin draws a strong contrast between what it means to be free for men and women. While freedom is just part of what it means to be a man in America, freedom for women looks markedly different. Louise’s life is shaped by what society believes a woman should be and how a wife should behave. Once Louise’s husband “dies,” however, she sees a way where she can start claiming some of the more “masculine” freedoms for herself. Chopin shows how deeply important freedom is to the life of a woman when, in the end, it’s not the shock of her husband’s return of her husband that kills Louise, but rather the thought of losing her freedom again.

Marriage as a “The Story of an Hour” theme is more than just an idyllic life spent with a significant other. The Mallard’s marriage shows a reality of 1890s life that was familiar to many people. Marriage was a means of social control —that is to say, marriage helped keep women in check and secure men’s social and political power. While husbands were usually free to wander the world on their own, hold jobs, and make important family decisions, wives (at least those of the upper class) were expected to stay at home and be domestic.

Marriage in Louise Mallard’s case has very little love. She sees her marriage as a life-long bond in which she feels trapped, which readers see when she confesses that she loved her husband only “sometimes.” More to the point, she describes her marriage as a “powerful will bending hers in that blind persistence with which men and women believe they have a right to impose a private will upon a fellow-creature.” In other words, Louise Mallard feels injustice in the expectation that her life is dictated by the will of her husband.

Like the story, the marriages Kate witnessed often ended in an early or unexpected death. The women of her family, including Kate herself, all survived their husbands and didn’t remarry. While history tells us that Kate Chopin was happy in her marriage, she was aware that many women weren’t. By showing a marriage that had been built on control and society’s expectations, Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” highlights the need for a world that respected women as valuable partners in marriage as well as capable individuals.

While this painting by Johann Georg Meyer wasn't specifically of Louise Mallard, "Young Woman Looking Through a Window" is a depiction of what Louise might have looked like as she realized her freedom.

"The Story of an Hour" Characters

The best stories have developed characters, which is the case in “The Story of an Hour,” too. Five characters make up the cast of “The Story of an Hour”:

Louise Mallard

Brently mallard.

- The doctor(s)

By exploring the details of each character, we can better understand their motivations, societal role, and purpose to the story.

From the opening sentence alone, we learn a lot about Louise Mallard. Chopin writes, “Knowing that Mrs. Mallard was afflicted with a heart trouble, great care was taken to break to her as gently as possible the news of her husband’s death.”

From that statement alone, we know that she is married, has a heart condition, and is likely to react strongly to bad news . We also know that the person who is sharing the bad news views Louise as delicate and sensitive. Throughout the next few paragraphs, we also learn that Louise is a housewife, which indicates that she would be part of the middle-to-upper class in the 1890s. Chopin also describes Louise’s appearance as “young,” “fair, calm face,” with lines of “strength.” These characteristics are not purely physical, but also bleed into her character throughout the story.

Louise’s personality is described as different from other women . While many women would be struck with the news in disbelief, Louise cries with “wild abandonment”—which shows how powerful her emotions are. Additionally, while other women would be content to mourn for longer, Louise quickly transitions from grief to joy about her husband’s passing.

Ultimately, Chopin uses Louise’s character to show readers what a woman’s typical experience within marriage was in the 1890s. She uses Louise to criticize the oppressive and repressive nature of marriage, especially when Louise rejoices in her newfound freedom.

Josephine is Louise’s sister . We never hear of Josephine’s last name or whether she is married or not. We do know that she has come with Richards, a friend of Brently’s, to break the news of his death to her sister.

When Josephine tells Louise the bad news, she’s only able to tell Louise of Brently’s death in “veiled hints,” rather than telling her outright. Readers can interpret this as Josephine’s attempt at sparing Louise’s feelings. Josephine is especially worried about her sister’s heart condition, which we see in greater detail later as she warns Louise, “You will make yourself ill.” When Louise locks herself in her room, Josephine is desperate to make sure her sister is okay and begs Louise to let her in.

Josephine is the key supporting character for Louise, helping her mourn, though she never knows that Louise found new freedom from her husband’s supposed death . But from Josephine’s actions and interactions with Louise, readers can accurately surmise that she cares for her sister (even if she’s unaware of how miserable Louise finds her life).

Richards is another supporting character, though he is described as Brently’s friend, not Louise’s friend. It is Richards who finds out about Brently Mallard’s supposed death while at the newspaper office—he sees Brently’s name “leading the list of ‘killed.’” Richards’ main role in “The Story of an Hour” is to kick off the story’s plot.

Additionally, Richard’s presence at the newspaper office suggests he’s a writer, editor, or otherwise employee of the newspaper (although Chopin leaves this to readers’ inferences). Richards takes enough care to double-check the news and to make sure that Brently’s likely dead. He also enlists Josephine’s help to break the news to Louise. He tries to get to Louise before a “less careful, less tender friend” can break the sad news to her, which suggests that he’s a thoughtful person in his own right.

It’s also important to note is that Richards is aware of Louise’s heart condition, meaning that he knows Louise Mallard well enough to know of her health and how she is likely to bear grief. He appears again in the story at the very end, when he tries (and fails) to shield Brently from his wife’s view to prevent her heart from reacting badly. While Richards is a background character in the narrative, he demonstrates a high level of friendship, consideration, and care for Louise.

Brently Mallard would have been riding in a train like this one when the accident supposedly occurred.

Mr. Brently Mallard is the husband of the main character, Louise. We get few details about him, though readers do know he’s been on a train that has met with a serious accident. For the majority of the story, readers believe Brently Mallard is dead—though the end of “The Story of an Hour” reveals that he’s been alive all along. In fact, Brently doesn’t even know of the railroad tragedy when he arrives home “travel-stained.”

Immediately after Louise hears the news of his death, she remembers him fondly. She remarks on his “kind, tender hands” and says that Brently “never looked save with love” upon her . It’s not so much Brently as it’s her marriage to him which oppresses Louise. While he apparently always loved Louise, Louise only “sometimes” loved Brently. She constantly felt that he “impose[d] a private will” upon her, as most husbands do their wives. And while she realizes that Brently likely did so without malice, she also realized that “a kind intention or a cruel intention” makes the repression “no less a crime.”

Brently’s absence in the story does two things. First, it contrasts starkly with Louise’s life of illness and confinement. Second, Brently’s absence allows Louise to imagine a life of freedom outside of the confines of marriage , which gives her hope. In fact, when he appears alive and well (and dashes Louise’s hopes of freedom), she passes away.

The Doctor(s)

Though the mention of them is brief, the final sentence of the story is striking. Chopin writes, “When the doctors came they said she had died of heart disease—of the joy that kills.” Just as she had no freedom in life, her liberation from the death of her husband is told as a joy that killed her.

In life as in death, the truth of Louise Mallard is never known. Everything the readers know about her delight in her newfound freedom happens in Louise’s own mind; she never gets the chance to share her secret joy with anyone else.

Consequently, the ending of the story is double-sided. If the doctors are to be believed, Louise Mallard was happy to see her husband, and her heart betrayed her. And outwardly, no one has any reason to suspect otherwise. Her reaction is that of a dutiful, delicate wife who couldn’t bear the shock of her husband returned from the grave.

But readers can infer that Louise Mallard died of the grief of a freedom she never had , then found, then lost once more. Readers can interpret Louise’s death as her experience of true grief in the story—that for her ideal life, briefly realized then snatched away.

In "The Story of an Hour," the appearance of hearts symbolize both repression and hope.

“The Story of an Hour” Symbolism and Motifs

Symbols are any object, word, or other element that appear in the story and have additional meanings beyond. Motifs are elements from a story that gain meaning from being repeated throughout the narrative. The line between symbols and motifs is often hazy, but authors use both to help communicate their ideas and themes.

In “The Story of an Hour,” symbolism is everywhere, but the three major symbols present in the story are:

- The heart

- The house and the outdoors

- Joy and sorrow

Heart disease, referred to as a “heart condition” within the text, opens and closes the text. The disease is the initial cause for everyone’s concern, since Louise’s condition makes her delicate. Later, heart disease causes Louise’s death upon Brently’s safe return. In this case, Louise’s ailing heart has symbolic value because it suggests to readers that her life has left her heartbroken. When she believes she’s finally found freedom, Louise prays for a long life...when just the day before, she’d “had thought with a shudder that life might be long.”

As Louise realizes her freedom, it’s almost as if her heart sparks back to life. Chopin writes, “Now her bosom rose and fell tumultuously...she was striving to beat it back...Her pulses beat fast, and the coursing blood warmed and relaxed every inch of her body.” These words suggest that, with her newfound freedom, the symptoms of her heart disease have lifted. Readers can surmise that Louise’s diseased heart is the result of being repressed, and hope brings her heart back to life.

Unfortunately, when Brently comes back, so does Louise’s heart disease. And, although her death is attributed to joy, the return of her (both symbolic and literal) heart disease kills her in the end.

The House and the Outdoors

The second set of symbols are Louise’s house and the world she can see outside of her window. Chopin contrasts these two symbolic images to help readers better understand how marriage and repression have affected Louise.

First of all, Louise is confined to the home—both within the story and in general. For her, however, her home isn’t a place to relax and feel comfortable. It’s more like a prison cell. All of the descriptions of the house reinforce the idea that it’s closed off and inescapable . For instance, the front door is locked when Mr. Mallard returns home. When Mrs. Mallard is overcome with grief, she goes deeper inside her house and locks herself in her room.

In that room, however, Mrs. Mallard takes note of the outdoors by looking out of her window. Even in her momentary grief, she describes the “open square before her house” and “the new spring life.” The outdoors symbolize freedom in the story, so it’s no surprise that she realizes her newfound freedom as she looks out her window. Everything about the outside is free, beautiful, open, inviting, and pleasant...a stark contrast from the sadness inside the house .

The house and its differences from outdoors serve as one of many symbols for how Louise feels about her marriage: barred from a world of independence.

Joy and Sorrow

Finally, joy and sorrow are motifs that come at unexpected times throughout “The Story of an Hour.” Chopin juxtaposes joy and sorrow to highlight how tragedy releases Louise from her sorrow and gives her a joyous hope for the future.

At first, sorrow appears as Louise mourns the death of her husband. Yet, in just a few paragraphs, she finds joy in the event as she discovers a life of her own. Though Louise is able to see that feeling joy at such an event is “monstrous,” she continues to revel in her happiness.

It is later that, when others expect her to be joyful, Josephine lets out a “piercing cry,” and Louise dies. Doctors interpret this as “the joy that kills,” but more likely it’s a sorrow that kills. The reversal of the “appropriate” feelings at each event reveals how counterintuitive the “self-assertion which she suddenly recognized as the strongest impulse of her being” is to the surrounding culture. This paradox reveals something staggering about Louise’s married life: she is so unhappy with her situation that grief gives her hope...and she dies when that hope is taken away.

Key Takeaways: Kate Chopin's “The Story of an Hour”

Analyzing Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” takes time and careful thought despite the shortness of the story. The story is open to multiple interpretations and has a lot to reveal about women in the 1890s, and many of the story’s themes, characters, and symbols critique women’s marriage roles during the period .

There’s a lot to dig through when it comes to “The Story of an Hour” analysis. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, just remember a few things :

- Events from Kate Chopin’s life and from social changes in the 1890s provided a strong basis for the story.

- Mrs. Louise Mallard’s heart condition, house, and feelings represent deeper meanings in the narrative.

- Louise goes from a state of repression, to freedom, and then back to repression, and the thought alone is enough to kill her.

Remembering the key plot points, themes, characters, and symbols will help you write any essay or participate in any discussion. Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” has much more to uncover, so read it again, ask questions, and start exploring the story beyond the page!

What’s Next?

You may have found your way to this article because analyzing literature can be tricky to master. But like any skill, you can improve with practice! First, make sure you have the right tools for the job by learning about literary elements. Start by mastering the 9 elements in every piece of literature , then dig into our element-specific guides (like this one on imagery and this one on personification .)

Another good way to start practicing your analytical skills is to read through additional expert guides like this one. Literary guides can help show you what to look for and explain why certain details are important. You can start with our analysis of Dylan Thomas’ poem, “Do not go gentle into that good night.” We also have longer guides on other words like The Great Gatsby and The Crucible , too.

If you’re preparing to take the AP Literature exam, it’s even more important that you’re able to quickly and accurately analyze a text . Don’t worry, though: we’ve got tons of helpful material for you. First, check out this overview of the AP Literature exam . Once you have a handle on the test, you can start practicing the multiple choice questions , and even take a few full-length practice tests . Oh, and make sure you’re ready for the essay portion of the test by checking out our AP Literature reading list!

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

The Story of an Hour

Kate chopin, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

A Summary and Analysis of Kate Chopin’s ‘The Story of an Hour’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

Some short stories can say all they need to do in just a few pages, and Kate Chopin’s three-page 1894 story ‘The Story of an Hour’ (sometimes known as ‘The Dream of an Hour’) is a classic example. Yet those three pages remain tantalisingly ambiguous, perhaps because so little is said, so much merely hinted at. Yet Chopin’s short story is, upon closer inspection, a subtle, studied analysis of death, marriage, and personal wishes.

Written in April 1894 and originally published in Vogue in December of that year, the story focuses on an hour in the life of a married woman who has just learnt that her husband has apparently died.

‘The Story of an Hour’: plot summary

What happens in that brief hour, that story of an hour? A married woman, Mrs Louise Mallard, who has heart trouble, learns that her husband has died in a railroad accident.

Her sister Josephine breaks the news to her; it was her husband’s friend Richards who first heard about the railroad disaster and saw her husband’s name, Brently Mallard, at the top of the list of fatalities. Her first reaction is to weep at the news that her husband is dead; she then takes herself off to her room to be alone.

She sinks into an armchair and finds herself attuned to a series of sensations: the trees outside the window ‘aquiver with the new spring life’, the ‘breath of rain’ in the air; the sound of a peddler crying his wares in the street below. She finds herself going into a sort of trancelike daze, a ‘suspension of intelligent thought’.

Then, gradually, a feeling begins to form within her: a sense of freedom. Now her husband is dead, it seems, she feels free. She dreads seeing her husband’s face (as she knows she must, when she goes to identify the body), but she knows that beyond that lie years and years of her life yet to be lived, and ‘would all belong to her absolutely’.

She reflects that she had loved her husband – sometimes. Sometimes she hadn’t. But now, that didn’t matter: what matters is the ‘self-assertion’, the declaration of independence, that her life alone represents a new start.

But then, her sister Josephine calls from outside the door for her to come out, worried that Louise is making herself ill. But Louise doesn’t feel ill: she feels on top of the world. She used to dread the prospect of living to a ripe old age, but now she welcomes such a prospect. Eventually she opens the door and she and Josephine go back downstairs.

Richards is still down there, waiting for them. Then, there’s a key in the front door and who should enter but … Mrs Mallard’s husband, Brently Mallard.

It turns out he was nowhere near the scene of the railroad accident, and is unharmed! Mrs Mallard is so shocked at his return that she dies, partly because of her heart disease but also, so ‘they’ said, from the unexpected ‘joy’ of her husband’s return.

‘The Story of an Hour’: analysis

In some ways, ‘The Story of an Hour’ prefigures a later story like D. H. Lawrence’s ‘ Odour of Chrysanthemums ’ (1911), which also features a female protagonist whose partner’s death makes her reassess her life with him and to contemplate the complex responses his death has aroused in her.

However, in Lawrence’s story the husband really has died (in a mining accident), whereas in ‘The Story of an Hour’, we find out at the end of the story that Mr Mallard was not involved in the railroad accident and is alive and well. In a shock twist, it is his wife who dies, upon learning that he is still alive.

What should we make of this ‘dream of an hour’? That alternative title is significant, not least because of the ambiguity surrounding the word ‘dream’. Is Louise so plunged into shock by the news of her husband’s apparent death that she begins to hallucinate that she would be better off without him? Is this her way of coping with traumatic news – to try to look for the silver lining in a very black cloud? Or should we analyse ‘dream’ as a sign that she entertains aspirations and ambitions, now her husband is out of the way?

‘The Dream of an Hour’ perhaps inevitably puts us in mind of Kate Chopin’s most famous story, the short novel The Awakening (1899), whose title reflects its female protagonist Edna Pontellier’s growing awareness that there is more to life than her wifely existence.

But Louisa Mallard’s ‘awakening’ remains a dream; when she awakes from it, upon learning that her husband is still alive and all her fancies about her future life have been in vain, she dies.

‘The Story of an Hour’ and modernism

‘The Story of an Hour’ is an early example of the impressionistic method of storytelling which was also being developed by Anton Chekhov around the same time as Chopin, and which would later be used by modernists such as Katherine Mansfield, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf.

Although the story uses an omniscient third-person narrator, we are shown things from particular character perspectives in a way that reflects their own confusions and erratic thoughts – chiefly, of course, Louisa Mallard’s own.

But this impressionistic style – which is more interested in patterns of thought, daydreaming, and emotional responses to the world than in tightly structured plots – continues right until the end of the story.

Consider the final sentence of the story: ‘When the doctors came they said she had died of heart disease – of joy that kills.’ The irony, of course, is that Louisa appears to have accepted her husband’s death and to have taken his demise as a chance to liberate herself from an oppressive marriage (note Chopin’s reference to the lines on her face which ‘bespoke repression and even a certain strength’ – what did she need that strength for, we wonder?).

So it was not joy but disappointment, if anything, that brought on the heart attack that killed her. But the (presumably male) doctors who attended her death would not have assumed any such thing: they would have analysed her death as a result of her love for her husband, and the sheer joy she felt at having him back.

Chopin’s story also foreshadows Katherine Mansfield’s ‘The Garden Party’ , and Laura Sheridan’s enigmatic emotional reaction to seeing her first dead body (as with Chopin’s story, a man who has died in an accident). If you enjoyed this analysis of ‘The Story of an Hour’, you might also enjoy Anton Chekhov’s 1900 story ‘At Christmas Time’, to which Chopin’s story has been compared.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

The Story of an Hour

21 pages • 42 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Story Analysis

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Discussion Questions Beta

Use the dropdowns below to tailor your questions by title, pre- or post-reading status, topic, and the difficulty level that suits your audience. Click "Generate," and that's it! Your set of ready-to-discuss questions will populate in seconds.

Select and customize your discussion questions!

Your Discussion Questions

Your results will show here.

Our AI tools are evolving, sometimes exhibiting inaccuracies or biases that don't align with our principles. Discover how AI and expert content drive our innovative tools. Read more

Related Titles

By Kate Chopin

A Pair of Silk Stockings

Kate Chopin

A Respectable Woman

At the ’Cadian Ball

Desiree's Baby

The Awakening

The Night Came Slowly

Featured Collections

Allegories of Modern Life

View Collection

Feminist Reads

Fiction with Strong Female Protagonists

Required Reading Lists

School Book List Titles

English Studies

This website is dedicated to English Literature, Literary Criticism, Literary Theory, English Language and its teaching and learning.

“The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin: A Critical Analysis

“The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin, first published in 1894 in the St. Louis Life magazine, was later included in the 1895 collection “Vojageur” and in the 1895 edition of “Bayou Folk”.

Introduction: “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

“The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin, first published in 1894 in the St. Louis Life magazine, was later included in the 1895 collection “Vojageur” and in the 1895 edition of “Bayou Folk”. This iconic short story features a unique narrative structure, where the protagonist, Louise Mallard, experiences a rollercoaster of emotions upon learning of her husband’s death in a railroad accident. The story showcases Chopin’s mastery of exploring themes of freedom, marriage, and the human psyche, all within a concise and gripping narrative that has captivated readers for over a century. Some key features of the story include its use of irony, symbolism, and a focus on the inner experiences of the protagonist, making it a landmark of American literary modernism.

Main Events in “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

Table of Contents

- Mrs. Mallard Learns of Her Husband’s Death : Mrs. Mallard, afflicted with a heart condition, is gently informed of her husband’s death in a train accident by her sister Josephine and their friend Richards.

- Initial Grief and Solitude : Mrs. Mallard weeps in her sister’s arms and then withdraws to her room alone, overwhelmed by grief.

- Contemplation by the Window : Sitting alone in her room, Mrs. Mallard gazes out the window, observing signs of new life and feeling a sense of physical and emotional exhaustion.

- A Subtle Awakening : Mrs. Mallard begins to feel a subtle and elusive sense of freedom creeping over her, whispering “free, free, free!” as she starts to recognize a new sensation within herself.

- Embracing Freedom : As Mrs. Mallard acknowledges the prospect of freedom from her husband’s will and societal expectations, she feels a rush of joy and welcomes the years ahead for herself.

- Recognition of Self-Assertion : Mrs. Mallard reflects on the strength of her own desires for autonomy and self-assertion, realizing that it surpasses the complexities of love and relationships.

- Resistance and Revelation : Despite her sister’s pleas, Mrs. Mallard resists leaving her newfound sense of liberation, reveling in the elixir of life streaming through her open window.

- Vision of the Future : Mrs. Mallard’s imagination runs wild with possibilities for her future, filled with dreams of spring and summer days that will be entirely her own.

- Triumphant Reveal : Mrs. Mallard emerges from her room, exuding a feverish triumph, and descends the stairs with her sister, unaware of what awaits her.

- Shocking Revelation and Tragic End : The story takes a dramatic turn as Mrs. Mallard’s husband, Brently Mallard, returns home unharmed, unaware of the news of his death. The shock of his appearance leads to Mrs. Mallard’s sudden death, attributed by doctors to “the joy that kills.”

Literary Devices in “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

Characterization in “the story of an hour” by kate chopin.

- Afflicted with a heart condition, which influences her physical and emotional state throughout the story.

- Initially portrayed as experiencing grief and sorrow over her husband’s death but undergoes a transformation as she contemplates the prospect of freedom.

- Symbolizes themes of repression, liberation, and the complexities of marriage and societal expectations.

- Acts as a supportive figure to Mrs. Mallard, informing her of her husband’s death and attempting to comfort her.

- Represents familial bonds and the role of women in supporting each other in times of crisis.

- Present when the news of Brently Mallard’s death is revealed to Mrs. Mallard.

- His actions highlight the societal norms of male friendship and the expectation of delivering difficult news to women.

- Appears briefly at the end of the story, shocking Mrs. Mallard and ultimately leading to her death.

- Serves as a catalyst for Mrs. Mallard’s emotional journey and the revelation of her desire for freedom.

- Represents the constraints of traditional marriage and the loss of individual identity within such relationships.

Major Themes in “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

- Freedom and Liberation : The story explores the theme of freedom through Mrs. Mallard’s reaction to her husband’s death. Initially grieving, she experiences a profound sense of liberation and anticipates a future free from the constraints of marriage and societal expectations.

- Repression and Identity : Mrs. Mallard’s emotional journey highlights the repression of her true feelings within her marriage and society. Her brief moment of freedom allows her to glimpse her own desires and identity apart from her role as a wife.

- Irony and Unexpected Twists : Chopin employs irony and unexpected twists to challenge conventional narrative expectations. The revelation of Brently Mallard’s survival and Mrs. Mallard’s subsequent death subverts the reader’s assumptions and underscores the complexities of human emotion and experience.

- Death and Joy : The story juxtaposes themes of death and joy, suggesting that liberation and self-realization can emerge from unexpected or even tragic circumstances. Mrs. Mallard’s death, attributed to “the joy that kills,” underscores the paradoxical nature of human emotions and the complexities of inner lives.

Writing Style in “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

- Descriptive Imagery : Chopin employs vivid and sensory language to create imagery that immerses the reader in the setting and emotions of the story. Descriptions of the springtime scene outside Mrs. Mallard’s window, such as “aquiver with the new spring life,” evoke a sense of renewal and vitality.

- Stream-of-Consciousness : The story delves into Mrs. Mallard’s thoughts and feelings, often in a stream-of-consciousness style. This technique allows readers to experience her internal turmoil and the rapid shifts in her emotions as she grapples with the news of her husband’s death and the prospect of freedom.

- Symbolism : Chopin utilizes symbolism to convey deeper themes and meanings throughout the narrative. For example, the open window symbolizes the possibility of escape and liberation, while Mrs. Mallard’s physical and emotional confinement within her home reflects the constraints of her marriage and societal expectations.

- Irony and Subtext : The story is marked by irony and subtle subtext, particularly in its exploration of Mrs. Mallard’s reaction to her husband’s death. While her initial response appears to be one of grief, it gradually becomes clear that she is experiencing a sense of liberation and joy at the prospect of newfound freedom.

- Economy of Language : Chopin’s writing in “The Story of an Hour” is characterized by its economy of language, with each word carefully chosen to maximize impact. This concise style contributes to the story’s intensity and emotional resonance, allowing readers to experience the protagonist’s inner journey with clarity and immediacy.

Literary Theories and Interpretation of “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

Feminist Theory :

- Interpretation: Louise’s struggle for autonomy and independence

- Example: “There would be no one to live for during those coming years; she would live for herself.”

- Explanation: Louise’s desire for self-assertion and freedom from patriarchal oppression is a central theme. She rejects the societal expectations of women and seeks to live for herself, symbolizing her autonomy and independence.

Psychoanalytic Theory:

- Interpretation: Louise’s repressed emotions and inner conflict

- Example: “She was beginning to recognize this thing that was approaching to possess her, and she was striving to beat it back with her will—”

- Explanation: Louise’s inner turmoil and emotional struggle with her husband’s death reveal her repressed desires and inner conflict. Her feelings of freedom and joy are juxtaposed with her guilt and grief, highlighting her complex psyche.

Symbolic Theory:

- Interpretation: Symbols of freedom and oppression

- Example: “The open window and blue sky”

- Explanation: The open window and blue sky symbolize freedom, hope, and new life, while the closed door and darkness symbolize oppression and confinement. The window and sky represent Louise’s desire for escape and freedom, while the door and darkness represent her trapped and oppressive life.

Topics, Questions, and Thesis Statements about “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

Short questions/answers about/on “the story of an hour” by kate chopin.

- What is the significance of the title “The Story of an Hour” and how does it relate to the story’s themes? The title “The Story of an Hour” refers to the brief period of time during which the protagonist, Louise Mallard, experiences a sense of freedom and liberation after hearing of her husband’s death. This hour represents a turning point in her life, as she momentarily breaks free from the societal expectations and constraints that have defined her marriage. The title highlights the story’s exploration of freedom, individuality, and the oppressive nature of societal norms.

- How does Kate Chopin use symbolism in “The Story of an Hour” to convey the protagonist’s emotional journey and the themes of the story? Kate Chopin employs symbolism throughout the story to convey Louise’s emotional journey and the themes of freedom, individuality, and oppression. The open window, for instance, symbolizes Louise’s newfound freedom and her desire to break free from the constraints of her marriage. The “blue and far” sky represents the limitless possibilities and opportunities that lie ahead. The “new spring of life” and the “delicious breath of rain” symbolize renewal and rejuvenation, reflecting Louise’s growing sense of hope and liberation.

- What role does irony play in “The Story of an Hour,” and how does it contribute to the story’s themes and character development? Irony plays a significant role in “The Story of an Hour,” as it underscores the contradictions and tensions that exist between societal expectations and individual desires. The story’s use of dramatic irony, where the reader is aware of Louise’s inner thoughts and feelings, while the other characters are not, highlights the disconnect between her public and private selves. The situational irony, where Louise’s husband returns alive, subverts the reader’s expectations and underscores the oppressive nature of societal norms, which deny women their individuality and freedom.

- How does “The Story of an Hour” reflect the social and cultural context in which it was written, and what commentary does it offer on the status of women during this time period? “The Story of an Hour” reflects the social and cultural context of the late 19th century, a time when women’s rights and freedoms were severely limited. The story critiques the patriarchal society and the institution of marriage, which often trapped women in loveless and oppressive relationships. Through Louise’s character, Chopin highlights the suffocating nature of societal expectations and the longing for individuality and freedom that many women experienced during this time period. The story’s exploration of these themes offers a commentary on the status of women and the need for greater autonomy and self-expression.

Literary Works Similar to “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

- “ The Yellow Wallpaper ” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman : This story explores themes of female oppression and mental health as a woman confined to a room by her husband begins to unravel psychologically.

- “ A Jury of Her Peers ” by Susan Glaspell : Based on Glaspell’s play “Trifles,” this story delves into gender roles and justice as women uncover crucial evidence while accompanying their husbands on a murder investigation.

- “The Awakening” by Kate Chopin : Another work by Chopin, this novella examines the constraints of marriage and societal expectations as a woman seeks independence and self-discovery in late 19th-century Louisiana.

- “ The Chrysanthemums ” by John Steinbeck : Set in the Salinas Valley during the Great Depression, this story follows a woman’s encounter with a traveling tinkerer, exploring themes of isolation, longing, and gender roles.

- “The Story of a Dead Man” by Ambrose Bierce : Bierce’s story, similar to “The Story of an Hour,” explores themes of freedom and liberation as a man seemingly returns from the dead, causing his widow to contemplate her newfound independence.

Suggested Readings about/on “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

Books on kate chopin and “the story of an hour”:.

- Bonner, Thomas Jr. The Kate Chopin Companion . Greenwood, 1988.

- Ewell, Barbara C. Kate Chopin . Ungar, 1986.

- Papke, Mary E. Verging on the Abyss: The Social Fiction of Kate Chopin and Edith Wharton . Greenwood, 1990.

- Seyersted, Per. Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography . Louisiana State UP, 1969.

- Skaggs, Peggy. Kate Chopin . Twayne, 1985.

Articles on “The Story of an Hour”:

- Mitchell, Angelyn. “Feminine Double Consciousness in Kate Chopin’s ‘The Story of an Hour.'” CEAMagazine 5.1 (1992): 59-64.

- Miner, Madonne M. “Veiled Hints: An Affective Stylist’s Reading of Kate Chopin’s ‘Story of an Hour.'” Markham Review 11 (1982): 29-32.

Web Resource:

- The Kate Chopin International Society offers a wealth of information on Chopin and “The Story of an Hour,” including the full text of the story and critical essays: Kate Chopin International Society: https://www.katechopin.org/story-hour/

Representative Quotations from “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

Related posts:.

- “The Use of Force” by William Carlos Williams

- “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” by Ambrose Bierce: Analysis

- “The Shawl” by Cynthia Ozick: Analysis

- “The Old Pond” by Matsuo Basho: Analysis

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.6: Discussion Questions for “Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 22674

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)