- Department of Economic and Social Affairs Social Inclusion

- Meet our Director

- Milestones for Inclusive Social Development.

- Second World Summit For Social Development 2025

- World Summit For Social Development 1995

- 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- UN Common Agenda

- International Days

- International Years

- Social Media

- Social Development Issues

- Cooperatives

- Digital Inclusion

- Employment & Decent Work

- Indigenous Peoples

- Poverty Eradication

- Social Inclusion

- Social Protection

- Sport for Development & Peace

- Commission for Social Development (CSocD)

- Conference of States Parties to the CRPD (COSP)

- General Assembly Second Committee

- General Assembly Third Committee

- Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on Ageing

- United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII)

- Publications

- World Social Report

- World Youth Report

- UN Flagship Report On Disability And Development

- State Of The World’s Indigenous Peoples

- Policy Briefs

- General Assembly Reports and Resolutions

- ECOSOC Reports and Resolutions

- UNPFII Recommendations Database

- Capacity Development

- Civil Society

- Expert Group Meetings

Everyone Included: Social Impact of COVID-19

We are facing a global health crisis unlike any in the 75-year history of the United Nations — one that is killing people, spreading human suffering, and upending people’s lives. But this is much more than a health crisis. It is a human, economic and social crisis. The coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which has been characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), is attacking societies at their core.

The UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) is a pioneer of sustainable development and the home of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), where each goal finds its space and where all stakeholders can do their part to leave no one behind. UN DESA through the Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD), monitors national and global socio-economic trends, identifies emerging issues, and assesses their implications for social policy at the national and international levels. To this end, we are a leading analytical voice for promoting social inclusion, reducing inequalities and eradicating poverty.

The COVID-19 outbreak affects all segments of the population and is particularly detrimental to members of those social groups in the most vulnerable situations, continues to affect populations, including people living in poverty situations, older persons, persons with disabilities, youth, and indigenous peoples. Early evidence indicates that that the health and economic impacts of the virus are being borne disproportionately by poor people. For example, homeless people, because they may be unable to safely shelter in place, are highly exposed to the danger of the virus. People without access to running water, refugees, migrants, or displaced persons also stand to suffer disproportionately both from the pandemic and its aftermath – whether due to limited movement, fewer employment opportunities, increased xenophobia etc.

If not properly addressed through policy the social crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic may also increase inequality, exclusion, discrimination and global unemployment in the medium and long term. Comprehensive, universal social protection systems, when in place, play a much durable role in protecting workers and in reducing the prevalence of poverty, since they act as automatic stabilizers. That is, they provide basic income security at all times, thereby enhancing people’s capacity to manage and overcome shocks.

As emphasized by the United Nations Secretary-General, during the launch of a COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan on 23 March 2020 “We must come to the aid of the ultra-vulnerable – millions upon millions of people who are least able to protect themselves. This is a matter of basic human solidarity. It is also crucial for combating the virus. This is the moment to step up for the vulnerable.”

Older Persons

Older persons are not just struggling with greater health risks but are also likely to be less capable of supporting themselves in isolation. Although social distancing is necessary to reduce the spread of the disease, if not implemented correctly, such measures can also lead to increased social isolation of older persons at a time when they may be at most need of support.

The discourse around COVID-19, in which it is perceived as a disease of older people, exacerbates negative stereotypes about older persons who may be viewed as weak, unimportant and a burden on society. Such age-based discrimination may manifest in the provision of services because the treatment of older persons may be perceived to have less value than the treatment of younger generations. International human rights law guarantees everyone the right to the highest attainable standard of health and obligates Governments to take steps to provide medical care to those who need it. Shortages of ventilators, for example, necessitate the adoption of triage policies and protocols based on medical, evidence-based and ethical factors, rather than arbitrary decisions based on age. In this context, solidarity between generations, combating discrimination against older people, and upholding the right to health, including access to information, care and medical services is key. Read more..

Persons with Disabilities

General individual self-care and other preventive measures against the COVID-19 outbreak can entail challenges for persons with disabilities. For instance, some persons with disabilities may have difficulties in implementing measures to keep the virus at bay, including personal hygiene and recommended frequent cleaning of surfaces and homes. Cleaning homes and washing hands frequently can be challenging, due to physical impairments, environmental barriers, or interrupted services. Others may not be able to practice social distancing or cannot isolate themselves as thoroughly as other people, because they require regular help and support from other people for every day self-care tasks.

To ensure that persons with disabilities are able to access to information on COVID-19, it must be made available in accessible formats. Healthcare buildings must also be physically accessible to persons with mobility, sensory and cognitive impairments. Moreover, persons with disabilities must not be prevented from accessing the health services they need in times of emergency due to any financial barriers. Read more..

In terms of employment, youth are disproportionately unemployed, and those who are employed often work in the informal economy or gig economy, on precarious contracts or in the service sectors of the economy, that are likely to be severely affected by COVID-19.

More than one billion youth are now no longer physically in school after the closure of schools and universities across many jurisdictions. The disruption in education and learning could have medium and long-term consequences on the quality of education, though the efforts made by teachers, school administrations, local and national governments to cope with the unprecedented circumstances to the best of their ability should be recognized. Many vulnerable youth such as migrants or homeless youth are in precarious situations. They are the ones who can easily be overlooked if governments do not pay specific attention, as they tend to be already in a situation without even their minimum requirements being met on health, education, employment and well-being. Read more..

The first point of prevention is the dissemination of information in indigenous languages, thus ensuring that services and facilities are appropriate to the specific situation of indigenous peoples, and all are reached.

The large number of indigenous peoples who are outside of the social protection system further contributes to vulnerability, particularly if they are dependent on income from the broader economy – produce, tourism, handicrafts and employment in urban areas. In this regard, Governments should ensure that interim financial support measures include indigenous peoples and other vulnerable groups.

Indigenous peoples are also seeking their own solutions to this pandemic. They are taking action and using traditional knowledge and practices as well as preventive measures – in their languages. Read more..

Sport for Development and Peace

Since its onset, the COVID-19 pandemic has spread to almost all countries of the world. Social and physical distancing measures, lockdowns of businesses, schools and overall social life, which have become commonplace to curtail the spread of the disease, have also disrupted many regular aspects of life, including sport and physical activity. This policy brief highlights the challenges COVID-19 has posed to both the sporting world and to physical activity and well-being, including for marginalized or vulnerable groups. It further provides recommendations for Governments and other stakeholders, as well as for the UN system, to support the safe reopening of sporting events, as well as to support physical activity during the pandemic and beyond.

To safeguard the health of athletes and others involved, most major sporting events at international, regional and national levels have been cancelled or postponed – from marathons to football tournaments, athletics championships to basketball games, handball to ice hockey, rugby, cricket, sailing, skiing, weightlifting to wrestling and more. The Olympics and Paralympics, for the first time in the history of the modern games, have been postponed, and will be held in 2021. Read more..

“This is the moment to step up for the vulnerable” “Older persons, persons with chronic illness and persons with disabilities face particular, disproportionate risks, and require an all-out effort to save their lives and protect their future.” UN Secretary-General António Guterres launches a COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan together with Mark Lowcock, USG for Humanitarian Affairs; Tedros Ghebreyesus, Director-General of WHO and Henrietta Fore, Executive Director of UNICEF, 23 March 2020

Statement on COVID-19 by Under-Secretary-General Liu Zhenmin

It presents detailed analysis and solid evidence needed for effective decision-making on a number of critical social and economic issues – including designing inclusive stimulus packages; preventing a global debt crisis; supporting countries in special situations; protecting the most vulnerable groups of people; strengthening the role of science, technology and institutions for an effective response; and working together to build back better and achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

We need solidarity, political will and innovative policy action to protect vulnerable people and their well-being, and uphold the right to health, including access to information, care and medical services.

* When Everyone is Included, Everyone Benefits. *

For more information about United Nations Coronavirus global health emergency, please visit: https://www.un.org/coronavirus

Our Common Agenda is the Secretary-General's vision for the future of global cooperation. It calls for inclusive, networked, and effective multilateralism to better respond and deliver for the people and planet and to get the world back on track by turbocharging action on the Sustainable Development Goals . It outlines possible solutions to address the gaps and risks that have emerged since 2015, calling for a Summit of the Future that will be held in 2024. Read the report / Read the Summary / Learn More About Our Common Agenda Policy Brief: - Future Generations - Emergency Platform - Youth Engagement - Global Digital Impact - Information Integrity

The 75th Anniversary of the United Nations was marked in June 2020 with a declaration by Member States that included 12 overarching commitments along with a request to the Secretary-General for recommendations to address both current and future challenges. In September 2021, the Secretary-General responded with his report, Our Common Agenda , a wake-up call to speed up the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals and propel the commitments contained in the UN75 Declaration. In some cases, the proposals addressed gaps that emerged since 2015, requiring new intergovernmental agreements. The report, therefore, called for a Summit of the Future to forge a new global consensus on readying ourselves for a future that is rife with risks but also opportunities. The General Assembly welcomed the submission of the “rich and substantive” report and agreed to hold the Summit on 22-23 September 2024, preceded by a ministerial meeting in 2023. An action-oriented Pact for the Future is expected to be agreed by Member States through intergovernmental negotiations on issues they decide to take forward.

For 2023 SDG Summit, please visit https://www.un.org/en/ conferences/SDGSummit2023

- COVID-19: How the data and statistical community stepped up to the new challenges

- Social policy and social protection measures to build Africa better post-COVID-19

- Strengthening Data Governance for Effective Use of Open Data and Big Data Analytics for Combating COVID-19

- The long-term impact of COVID-19 on poverty

- COVID-19 and a primer on shock-responsive social protection systems

- Achieving SDGs in the wake of COVID-19: Scenarios for policymakers

- The role of public service and public servants during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Forests: at the heart of a green recovery from COVID-19 pandemic

- Resilient institutions in times of crisis: transparency, accountability and participation at the national level key to effective response to COVID-19

- Responses to the COVID-19 catastrophe could turn the tide on inequality

- Protecting and mobilizing youth in COVID-19 responses

- The COVID-19 crisis through the disability and gender lens

- United Nations Comprehensive Response to COVID-19 Saving Lives, Protecting Societies, Recovering Better

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: Impact of COVID-19 in Africa

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on South-East Asia

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Arab Region An Opportunity to Build Back Better

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Latin America and the Caribbean

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: COVID-19 and Universal Health Coverage

- COVID-19, Inequalities and Building Back Better: Policy Brief by the HLCP Inequalities Task Team

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health

- Tackling the inequality pandemic: a New Social Contract for a new era

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond

- UN Report on “Shared Responsibility, Global Solidarity: Responding to the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 | The Secretary-General’s UN Response and Recovery Fund

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on older persons

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: A Disability-Inclusive Response to COVID-19

- UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief: COVID-19 and Human Rights: We are all in this together

- Special UN DESA Voice edition puts spotlight on COVID-19 impact on our lives and societies

- WHO is working closely with global experts, governments and partners to rapidly expand scientific knowledge on this new virus, to track the spread and virulence of the virus, and to provide advice to countries and individuals on measures to protect health and prevent the spread of this outbreak. Resources on Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic by WHO.

- A new web portal that showcases UN DESA’s response to the global COVID-19 pandemic has been launched. The portal will shine a light on the cutting-edge analysis and policy advice in those areas where UN DESA’s voice is critical to addressing this global crisis. The portal will feature a series of policy briefs on COVID-19, which draw on unique expertise from around the Department.

- COVID-19 Outbreak and Gender: Key Advocacy Points from Asia and the Pacific by UN Women

- COVID-19 and the world of work by ILO

- Why Indigenous languages matter: The International Decade on Indigenous Languages 2022–2032

- Promoting youth participation in decision-making and public service delivery through harnessing digital technologies

- Old age inequality begins at birth: life course influences on late-life disability

- Old-age poverty has a woman’s face

- The monetary policy response to COVID-19: the role of asset purchase programmes

- COVID-19 pandemic disruption – Implications on the full deployment of the United Nations Legal Identity Agenda

- Policy implications of the disruption of the implementation of the 2020 World Population and Housing Census Programme due to the COVID-19 pandemic

- Horizontal and vertical integration are more necessary than ever for COVID-19 recovery and SDG implementation

- Digitally enabled new forms of work and policy implications for labour regulation frameworks and social protection systems

- Reducing poverty and inequality in rural areas: key to inclusive development

- COVID-19 and Beyond: Scaling up Private Investment for Sustainable Development

- Leveraging digital technologies for social inclusion

- The politics of economic insecurity in the COVID-19 era

- A new global deal must promote economic security

- Recovering from COVID-19: the importance of investing in global public goods for health

- Achieving the SDGs through the COVID-19 response and recovery

- COVID-19 poses grievous economic challenge to landlocked developing countries

- How can investors move from greenwashing to SDG-enabling?

- COVID-19: Reaffirming State-People Governance Relationships

- The impact of COVID-19 on sport, physical activity and well-being and its effects on social development

- COVID-19 and sovereign debt

- COVID-19 pandemic deals a huge blow to the manufacturing exports from LDCs

- The Impact of COVID-19 on Indigenous Peoples

- Leaving no one behind: the COVID-19 crisis through the disability and gender lens

- COVID-19 and Older Persons: A Defining Moment for an Informed, Inclusive and Targeted Response

- Responses to the COVID-19 catastrophe could turn the tide on inequality

- COVID-19 pandemic: a wake-up call for better cooperation at the science-policy-society interface

- COVID-19: Embracing digital government during the pandemic and beyond

- Commodity-dependent economies face mounting economic challenge as the pandemic ravages developed countries

- Corona crisis causes turmoil in financial markets

- COVID-19: Addressing the social crisis through fiscal stimulus plans

- COVID-19: Disrupting lives, economies and societies

In order to highlight the work that civil society organizations are doing on the ground, and the value added that they bring to the global response to the pandemic, the UN is inviting civil society to share their stories. Whatever the area of work of your organization, we believe that our common purpose will lift us during this difficult time, and that we can learn from and build on each other’s efforts. If your organization has been active in identifying or meeting the needs arising from COVID19 in your community, please follow this link and share your experiences, photos and videos with us so we can highlight your learnings. Submit your story.

For more information, please visit: www.un.org/en/civil-society/page/coronavirus-disease-covid-19

UN Chief Economist Mr. Elliott Harris and other experts from UN DESA have shared the main findings of three new briefing papers on the social, economic and financial impacts of COVID-19, as well as public policy recommendations. The online webinar took place on Thursday, 9 April 2020.

Watch a recording of this event on Facebook. Access the presentation here.

Join UN DESA’s Assistant Secretary-General for Policy Coordination and Inter-Agency Affairs Ms. Maria-Francesca Spatolisano, Mr. Fabrizio Hochschild-Drummond , Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on the Preparations for the Commemoration of the United Nations 75th Anniversary, and UN DESA experts for the second UN DESA Webinar on COVID-19: Strengthening Science and Technology and Addressing Inequalities on 6 May 2020, from 10 am to 12 noon EDT.

Watch a recording of this event on Facebook. Access the presentation here .

For more webinars, please visit https://social.desa.un.org/events/type/webinar

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, UN DESA has published a series of policy briefs in addition to its regular work in support of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To support this work and other initiatives of the Department and the wider UN system, UN DESA launched a Global Policy Dialogue Series in July 2020 aimed at highlighting solutions to the economic and social impacts of the pandemic. The series is made possible through the United Nations Peace and Development Trust Fund .

The sessions are dynamic, with UN DESA using its convening power to bring together global thought leaders and its own socioeconomic experts to consider today’s major issues. The conversations, typically 90 minutes long, are led by a journalist moderator to ensure that the discussions are sharp and to the point. UN DESA partners with other UN entities and top socioeconomic forums, and broadcasts everything live on the Department’s Facebook page to expand its reach to audiences that may not typically follow UN proceedings. The events are held in English with translation in American Sign Language and captions available in the six official UN languages.

The Dialogues aim to help countries recover better from the pandemic and closely align UN DESA’s work with the Decade of Action . The results of these discussions are shared with UN leadership and will inform future work on the economic and social effects of the pandemic.

- UN DESA Global Policy Dialogues to Turbocharge SDG Implementation

- Youth and Indigenous Solutions for Water

- Leaving No One Behind in an Ageing World: A UN DESA Global Policy Dialogue

- Building a Sustainable World for 8 Billion People: A UN DESA Fireside Chat

- Preparing for 8 Billion People: A UN DESA Global Policy Dialogue

- Protecting Biodiversity in Times of Crisis: Exploring SDGs 14 and 15

- Promoting Gender Equality Through Education: Exploring SDGs 4 and 5

- Big Questions for the Global Economic Recovery

- The Future of Sustainable Development Financing

- The Future of Population Growth

- The Future of Money

- The Future of Trust in Government

- The Future of Our Planet

- The Future of Community

- The Future of Work

- Financing Global Climate Action and Promoting Digital Solutions

- Strengthening Sustainable Forest and Ocean Management to Mitigate Climate Change

- Imagining the Carbon-neutral Future: Transformations in Energy and Transport

- Building Food and Water Security in an Era of Climate Shocks

- Shaping a New Social Contract: Session 2

- Shaping a New Social Contract: Session 1

- Advancing equitable livelihoods in food systems

- Gender Equality: A Data and Policy Dialogue

- Technological and Science-based Solutions to the COVID-19 Challenge

- Navigating Uncertainties: An Intergenerational dialogue on COVID-19 and youth employment

- Recover Better: Economic and Social Challenges and Opportunities

- COVID 19 and the disability movement by the International Disability Alliance (IDA)

- Families and family policies after COVID-19 by the International Federation for Family Development (IFFD)

- Search Search

Social and economic impact of COVID-19

Download the full working paper

Subscribe to Global Connection

Eduardo levy yeyati and eduardo levy yeyati former nonresident senior fellow - global economy and development @eduardoyeyati federico filippini federico filippini visiting professor - universidad torcuato di tella @efefilippini.

June 8, 2021

Introduction

The impact of the pandemic on world GDP growth is massive. The COVID-19 global recession is the deepest since the end of World War II (Figure 1). The global economy contracted by 3.5 percent in 2020 according to the April 2021 World Economic Outlook Report published by the IMF, a 7 percent loss relative to the 3.4 percent growth forecast back in October 2019. While virtually every country covered by the IMF posted negative growth in 2020 (IMF 2020b), the downturn was more pronounced in the poorest parts of the world (Noy et al. 2020) (Figure 2).

The impact of the shock is likely to be long-lasting. While the global economy is expected to recover this year, the level of GDP at the end of 2021 in both advanced and emerging market and developing economies (EMDE) is projected to remain below the pre-virus baseline (Figure 3). As with the immediate impact, the magnitude of the medium-term cost also varies significantly across countries, with EMDE suffering the greatest loss. The IMF (2021) projects that in 2024 the World GDP will be 3 percent (6 percent for low-income countries (LICs)) below the no-COVID scenario. Along the same lines, Djiofack et al. (2020) estimate that African GDP would be permanently 1 percent to 4 percent lower than in the pre-COVID outlook, depending on the duration of the crisis.

The pandemic triggered a health and fiscal response unprecedented in terms of speed and magnitude. At a global scale, the fiscal support reached nearly $16 trillion (around 15 percent of global GDP) in 2020. However, the capacity of countries to implement such measures varied significantly. In this note, we identify three important preexisting conditions that amplified the impact of the shock:

- Fiscal space: The capacity to support household and firms largely depends on access to international financial markets,

- State capacity: Fast and efficient implementation of policies to support household and firms requires a substantial state capacity and well-developed tax and transfer infrastructure; and

- Labor market structure: A large share of informal workers facing significant frictions to adopt remote working, and high levels of poverty and inequality, deepen the deleterious impact of the crisis.

Additionally, the speed and the strength of the recovery will be crucially dependent on the capacity of the governments to acquire and roll out the COVID-19 vaccines.

This paper presents a succinct summary of the existing economic literature on the economic and fiscal impact of the pandemic, and a preliminary estimate of the associated economic cost. It documents the incidence of initial conditions (with a particular focus on the role of the labor market channel) on the transmission of the shock and the speed and extent of the expected recovery, summarizes how countries attempted to attenuate the economic consequences and the international financial institutions assisted countries, reports preliminary accounts of medium-term COVID-related losses, and concludes with some forward-looking considerations based on the lessons learned in 2020.

Related Content

Homi Kharas, Meagan Dooley

June 2, 2021

Wolfgang Fengler, Homi Kharas

May 20, 2021

Global Economy and Development

Mark Schoeman

May 16, 2024

Ben S. Bernanke, Olivier Blanchard

Joseph Asunka, Landry Signé

May 15, 2024

- Frontiers in Genetics

- ELSI in Science and Genetics

- Research Topics

COVID-19 pandemics: ethical, legal and social issues

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

Living through the Covid-19 pandemic, many have seen a number of ethical, legal, and social issues arise as a result of the virus rapidly spreading worldwide. This timely special issue is designed to be a mid-stream retrospective: look at presenting a broad array of topics at the intersection of science and ...

Keywords : covid-19, pandemic, ESLI, patient screening, data privacy, contact tracing, quarantine measures, lockdown, drug and vaccine development

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

Special Issue: COVID-19

This essay was published as part of a Special Issue on Misinformation and COVID-19, guest-edited by Dr. Meghan McGinty (Director of Emergency Management, NYC Health + Hospitals) and Nat Gyenes (Director, Meedan Digital Health Lab).

Peer Reviewed

The causes and consequences of COVID-19 misperceptions: Understanding the role of news and social media

Article metrics.

CrossRef Citations

Altmetric Score

PDF Downloads

We investigate the relationship between media consumption, misinformation, and important attitudes and behaviours during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. We find that comparatively more misinformation circulates on Twitter, while news media tends to reinforce public health recommendations like social distancing. We find that exposure to social media is associated with misperceptions regarding basic facts about COVID-19 while the inverse is true for news media. These misperceptions are in turn associated with lower compliance with social distancing measures. We thus draw a clear link from misinformation circulating on social media, notably Twitter, to behaviours and attitudes that potentially magnify the scale and lethality of COVID-19.

Department of Political Science, McGill University, Canada

Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, University of Toronto, Canada

Max Bell School of Public Policy, McGill University, Canada

School of Computer Science, McGill University, Canada

Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, McGill University, Canada

Computer Science Program, McGill University, Canada

Research Questions

- How prevalent is misinformation surrounding COVID-19 on Twitter, and how does this compare to Canadian news media?

- Does the type of media one is exposed to influence social distancing behaviours and beliefs about COVID-19?

- Is there a link between COVID-19 misinformation and perceptions of the pandemic’s severity and compliance with social distancing recommendations?

Essay Summary

- We evaluate the presence of misinformation and public health recommendations regarding COVID-19 in a massive corpus of tweets as well as all articles published on nineteen Canadian news sites. Using these data, we show that preventative measures are more encouraged and covered on traditional news media, while misinformation appears more frequently on Twitter.

- To evaluate the impact of this greater level of misinformation, we conducted a nationally representative survey that included questions about common misperceptions regarding COVID-19, risk perceptions, social distancing compliance, and exposure to traditional news and social media. We find that being exposed to news media is associated with fewer misperceptions and more social distancing compliance while conversely, social media exposure is associated with more misperceptions and less social distancing compliance.

- Misperceptions regarding the virus are in turn associated with less compliance with social distancing measures, even when controlling for a broad range of other attitudes and characteristics.

- Association between social media exposure and social distancing non-compliance is eliminated when accounting for effect of misperceptions, providing evidence that social media is associated with non-compliance through increasing misperceptions about the virus.

Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has been accompanied by a so-called “infodemic”—a global spread of misinformation that poses a serious problem for public health. Infodemics are concerning because the spread of false or misleading information has the capacity to change transmission patterns (Kim et al., 2019) and consequently the scale and lethality of a pandemic. This information can be shared by any media, but there is reason to be particularly concerned about the role that social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, play in incidentally boosting misperceptions. These platforms are increasingly relied upon as primary sources of news (Mitchell et al., 2016) and misinformation has been heavily documented on them (Garrett, 2019; Vicario et al., 2016). Scholars have found medical and health misinformation on the platforms, including that related to vaccines (Radzikowski et al., 2016) and other virus epidemics such as Ebola (Fung et al., 2016) and Zika (Sharma et al., 2017).

However, misinformation content typically makes up a low percentage of overall discussion of a topic (e.g. Fung et al., 2016) and mere exposure to misinformation does not guarantee belief in that misinformation. More research is thus needed to understand the extent and consequences of misinformation surrounding COVID-19 on social media. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Twitter, Facebook and other platforms have engaged in efforts to combat misinformation but they have continued to receive widespread criticism that misinformation is still appearing on prominent pages and groups (Kouzy et al., 2020; NewsGuard, 2020). The extent to which misinformation continues to circulate on these platforms and influence people’s attitudes and behaviours is still very much an open question.

Here, we draw on three data sets and a sequential mixed method approach to better understand the consequences of online misinformation for important behaviours and attitudes. First, we collected nearly 2.5 million tweets explicitly referring to COVID-19 in the Canadian context. Second, we collected just over 9 thousand articles from nineteen Canadian English-language news sites from the same time period. We coded both of these media sets for misinformation and public health recommendations. Third, we conducted a nationally representative survey that included questions related to media consumption habits, COVID-19 perceptions and misperceptions, and social distancing compliance. As our outcome variables are continuous, we use Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression to identify relationships between news and social media exposure, misperceptions, compliance with social distancing measures, and risk perceptions. We use these data to illustrate: 1) the relative prevalence of misinformation on Twitter; and 2) a powerful association between social media usage and misperceptions, on the one hand, and social distancing non-compliance on the other.

Misinformation and compliance with social distancing

We first compare the presence of misinformation on Twitter with that on news media and find, consistent with the other country cases (Chadwick & Vaccari, 2019; Vicario et al., 2016), comparatively higher levels of misinformation circulating on the social media platform. We also found that recommendations for safe practices during the pandemic (e.g. washing hands, social distancing) appeared much more frequently in the Canadian news media. These findings are in line with literature examining fake news which finds a large difference in information quality across media (Al-Rawi, 2019; Guess & Nyhan, 2018).

Spending time in a media environment that contains misinformation is likely to change attitudes and behaviours. Even if users are not nested in networks that propagate misinformation, they are likely to be incidentally exposed to information from a variety of perspectives (Feezell, 2018; Fletcher & Nielsen, 2018; Weeks et al., 2017). Even a highly curated social media feed is thus still likely to contain misinformation. As cumulative exposure to misinformation increases, users are likely to experience a reinforcement effect whereby familiarity leads to stronger belief (Dechêne et al., 2010).

To evaluate this empirically, we conducted a national survey that included questions on information consumption habits and a battery of COVID-19 misperceptions that could be the result of exposure to misinformation. We find that those who self-report exposure to the misinformation-rich social media environment do tend to have more misperceptions regarding COVID-19. These findings are consistent with others that link exposure to misinformation and misperceptions (Garrett et al., 2016; Jamieson & Albarracín, 2020). Social media users also self-report less compliance with social distancing.

Misperceptions are most meaningful when they impact behaviors in dangerous ways. During a pandemic, misperceptions can be fatal. In this case, we find that misperceptions are associated with reduced COVID-19 risk perceptions and with lower compliance with social distancing measures. We continue to find strong effects after controlling for socio-economic characteristics as well as scientific literacy. After accounting for the effect of misperceptions on social distancing non-compliance, social media usage no longer has a significant association with non-compliance, providing evidence that social media may lead to less social distancing compliance through its effect on COVID-19 misperceptions.

While some social media companies have made efforts to suppress misinformation on their platforms, there continues to be a high level of misinformation relative to news media. Highly polarized political environments and media ecosystems can lead to the spread of misinformation, such as in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic (Allcott et al., 2020; Motta et al., 2020). But even in healthy media ecosystems with less partisan news (Owen et al., 2020), social media can continue to facilitate the spread of misinformation. There is a real danger that without concerted efforts to reduce the amount of misinformation shared on social media, the large-scale social efforts required to combat COVID-19 will be undermined.

We contribute to a growing base of evidence that misinformation circulating on social media poses public health risks and join others in calling for social media companies to put greater focus on flattening the curve of misinformation (Donovan, 2020). These findings also provide governments with stronger evidence that the misinformation circulating on social media can be directly linked to misperceptions and public health risks. Such evidence is essential for them to chart an effective policy course. Finally, the methods and approach developed in this paper can be fruitfully applied to study other waves of misinformation and the research community can build upon the link clearly drawn between misinformation exposure, misperceptions, and downstream attitudes and behaviours.

We found use of social media platforms broadly contributes to misperceptions but were unable to precise the overall level of misinformation circulating on non-Twitter social media. Data access for researchers to platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram is limited and virtually non-existent for SnapChat, WhatsApp, and WeChat. Cross-platform content comparisons are an important ingredient for a rich understand of the social media environment and these social media companies must better open their platforms to research in the public interest.

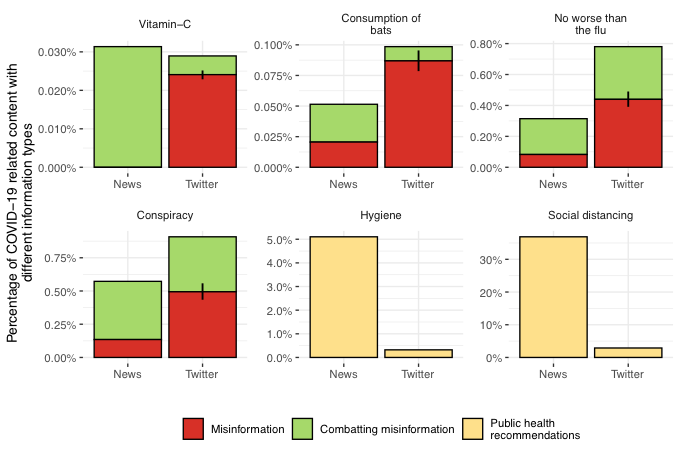

Finding 1: Misinformation about COVID-19 is circulated more on Twitter as compared to traditional media.

We find large differences between the quality of information shared about COVID-19 on traditional news and Twitter. Figure 1 shows the percentage of COVID-19 related content that contains information linked to a particular theme. The plot reports the prevalence of information on both social and news media for: 1) three specific pieces of misinformation; 2) a general set of content that describes the pandemic itself as a conspiracy or a hoax; and 3) advice about hygiene and social distancing during the pandemic. We differentiate content that shared misinformation (red in the plot) from content that debunked misinformation (green in the plot).

There are large differences between the levels of misinformation on Twitter and news media. Misinformation was comparatively more common on Twitter across all four categories, while debunking was relatively more common in traditional news. Meanwhile, advice on hygiene and social distancing appeared much more frequently in news media. Note that higher percentages are to be expected for longer format news articles since we rely on keyword searches for identification. This makes the misinformation findings even starker – despite much higher average word counts, far fewer news articles propagate misinformation.

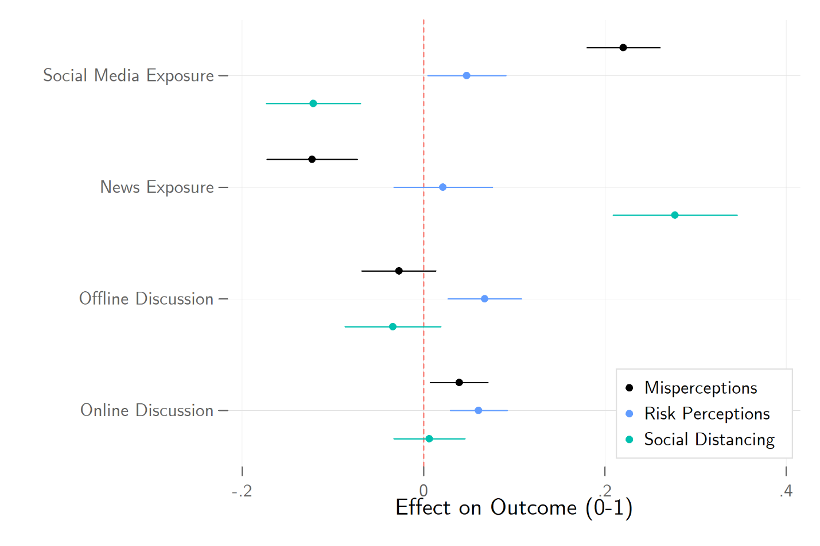

Finding 2: There is a strong association between social media exposure and misperceptions about COVID-19. The inverse is true for exposure to traditional news.

Among our survey respondents we find a corresponding strong association between social media exposure and misperceptions about COVID-19. These results are plotted in Figure 2, with controls included for both socioeconomic characteristics and demographics. Moving from no social media exposure to its maximum is expected to increase one’s misperceptions of COVID-19 by 0.22 on the 0-1 scale and decreased self-reported social distancing compliance by 0.12 on that same scale.

This result stands in stark contrast with the observed relationship between traditional news exposure and our outcome measures. Traditional news exposure is positively associated with correct perceptions regarding COVID-19. Moving from no news exposure to its highest level is expected to reduce misperceptions by 0.12 on the 0-1 scale and to increase social distancing compliance by 0.28 on that same scale. The effects are plotted in Figure 2. Social media usage appears to be correlated with COVID-19 misperceptions, suggesting these misperceptions are partially a result of misinformation on social media. The same cannot be said of traditional news exposure.

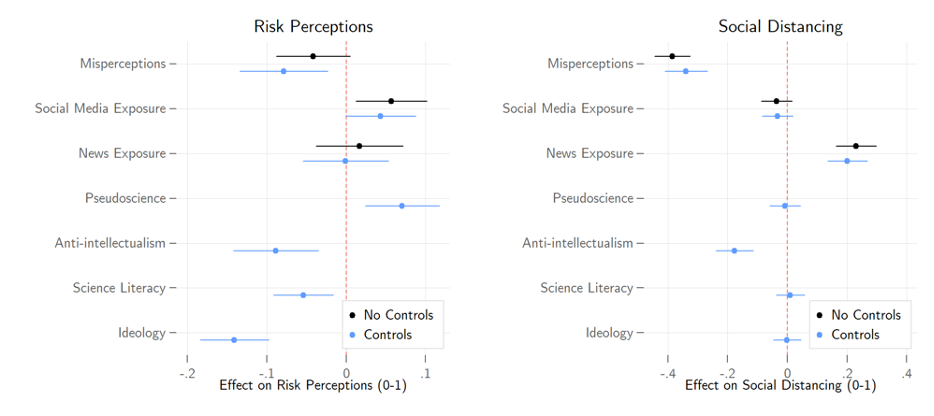

Finding 3: Misperceptions about the pandemic are associated with lower levels of risk perceptions and social distancing compliance.

COVID-19 misperceptions are also powerfully associated with lower levels of social distancing compliance. Moving from the lowest level of COVID-19 misperceptions to its maximum is associated with a reduction of one’s social distancing by 0.39 on the 0-1 scale. The previously observed relationship between social media exposure and misperceptions disappears, suggestive of a mediated relationship. That is, social media exposure increases misperceptions, which in turn reduces social distancing compliance. Misperceptions is also weakly associated with lower COVID-19 risk perceptions. Estimates from our models using COVID-19 concern as the outcome can be found in the left panel of Figure 3, while social distancing can be found in the right panel.

Finally, we also see that the relationship between misinformation and both social distancing compliance and COVID-19 concern hold when including controls for science literacy and a number of fundamental predispositions that are likely associated with both misperceptions and following the advice of scientific experts, such as anti-intellectualism, pseudoscientific beliefs, and left-right ideology. These estimates can similarly be found in Figure 3.

Canadian Twitter and news data were collected from March 26 th to April 6 th , 2020. We collected all English-language tweets from a set of 620,000 users that have been determined to be likely Canadians. For inclusion, a given user must self-identify as Canadian-based, follow a large number of Canadian political elite accounts, or frequently use Canadian-specific hashtags. News media was collected from nineteen prominent Canadian news sites with active RSS feeds. These tweets and news articles were searched for “covid” or “coronavirus”, leaving a sample of 2.25 million tweets and 8,857 news articles.

Of the COVID-19 related content, we searched for terms associated with four instances of misinformation that circulated during the COVID-19 pandemic: that COVID-19 was no more serious than the flu, that vitamin C or other supplements will prevent contraction of the virus, that the initial animal-to-human transfer of the virus was the direct result of eating bats, or that COVID-19 was a hoax or conspiracy. Given that we used keyword searches to identify content, we manually reviewed a random sample of 500 tweets from each instance of misinformation. Each tweet was coded as one of four categories: propagating misinformation, combatting misinformation, content with the relevant keywords but unrelated to misinformation, or content that refers to the misinformation but does not offer comment.

We then calculated the overall level of misinformation for that instance on Twitter by multiplying the overall volume of tweets by the proportion of hand-coded content where misinformation was identified. Each news article that included relevant keywords was similarly coded. The volume of the news mentioning these terms was sufficiently low that all news articles were hand coded. To identify health recommendations, we used a similar keyword search for terms associated with particular recommendations: 1) social distancing including staying at home, staying at least 6 feet or 2 meters away and avoiding gatherings; and 2) washing hands and not touching any part of your face. 1 Further details on the media collection strategy and hand-coding schema are available in the supporting materials.

For survey data, we used a sample of nearly 2,500 Canadian citizens 18 years or older drawn from a probability-based online national panel fielded from April 2-6, 2020. Quotas we set on age, gender, region, and language to ensure sample representativeness, and data was further weighted within region by gender and age based on the 2016 Canadian census.

We measure levels of COVID-19 misperceptions by asking respondents to rate the truthfulness of a series of nine false claims, such as the coronavirus being no worse than the seasonal flu or that it can be warded off with Vitamin C. Each was asked on a scale from definitely false (0) to definitely true (5). We use Cronbach’s Alpha as an indicator of scale reliability. Cronbach’s Alpha ranges from 0-1, with scores above 0.8 indicating the reliability is “good.” These items score 0.88, so we can safely construct a 0-1 scale of misperceptions from them.

We evaluate COVID-19 risk perceptions with a pair of questions asking respondents how serious of a threat they believe the pandemic to be for themselves and for Canadians, respectively. Each question was asked on a scale from not at all (0) to very (4). We construct a continuous index with these items.

We quantify social distancing by asking respondents to indicate which of a series of behaviours they had undertaken in response to the pandemic, such as working from home or avoiding in-person contact with friends, family, and acquaintances. We use principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the number of dimensions in these data while minimizing information loss. The analysis revealed 2 distinct dimensions in our questions. One dimension includes factors strongly determined by occupation, such as working from home and switching to online meetings. The other dimension contains more inclusive behaviours such as avoiding contact, travel, and crowded places. We generate predictions from the PCA for this latter dimension to use in our analyses. The factor loadings can be found in Table A1 of the supporting materials.

We gauge news and social media consumption by asking respondents to identify news outlets and social media platforms they have used over the past week for political news. The list of news outlets included 17 organizations such as mainstream sources like CBC and Global, and partisan outlets like Rebel Media and National Observer. The list of social media platforms included 10 options such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram. We sum the total number of outlets/platforms respondents report using and take the log to adjust for extreme values. We measure offline political discussion with an index based on questions asking how often respondents have discussed politics with family, friends, and acquaintances over the past week. Descriptions of our primary variables can be found in Table A2 of the supporting materials.

We evaluate our hypotheses using a standard design that evaluates the association between our explanatory and outcome variables controlling for other observable factors we measured. In practice, randomly assigning social media exposure is impractical, while randomly assigning misinformation is unethical. This approach allows us to describe these relationships, though we cannot make definite claims to causality.

We hypothesize that social media exposure is associated with misinformation on COVID-19. Figure 2 presents the coefficients of models predicting the effects of news exposure, social media exposure, and political discussion on COVID-19 misinformation, risk perceptions, and social distancing. Socio-economic and demographic control estimates are not displayed. Full estimation results can be found in the Table A3 of the supporting materials.

We further hypothesize that COVID-19 misinformation is associated with lower COVID-19 risk perceptions and less social distancing compliance. Figure 3 presents the coefficients for models predicting the effects of misinformation, news exposure, and social media exposure on severity perceptions and social distancing. We show models with and without controls for science literacy and other predispositions. Full estimation results can be found in the Table A4 of the supporting materials.

Limitations and robustness

A study such as this comes with clear limitations. First, we have evaluated information coming from only a section of the overall media ecosystem and during a specific time-period. The level of misinformation differs across platforms and online news sites and a more granular investigation into these dynamics would be valuable. Our analysis suggests that similar dynamics exist across social media platforms, however. In the supplementary materials we show that associations between misperceptions and social media usage are even higher for other social media platforms, suggesting that our analysis of Twitter content may underrepresent the prevalence of misinformation on social media writ large. As noted above, existing limitations on data access make such cross-platform research difficult.

Second, our data is drawn from a single country and language case study and other countries may have different media environments and levels of misinformation circulating on social media. We anticipate the underlying dynamics found in this paper to hold across these contexts, however. Those who consume information from platforms where misinformation is more prevalent will have greater misperceptions and that these misperceptions will be linked to lower compliance with social distancing and lower risk perceptions. Third, an ecological problem is present wherein we do not link survey respondents directly to their social media consumption (and evaluation of the misinformation they are exposed to) and lack the ability to randomly assign social media exposure to make a strong causal argument. We cannot and do not make a causal argument here but argue instead that there is strong evidence for a misinformation to misperceptions to lower social distancing compliance link.

- / Fake News

- / Mainstream Media

- / Public Health

- / Social Media

Cite this Essay

Bridgman, A., Merkley, E., Loewen, P. J., Owen, T., Ruths, D., Teichmann, L., & Zhilin, O. (2020). The causes and consequences of COVID-19 misperceptions: Understanding the role of news and social media. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review . https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-028

Bibliography

Allcott, H., Boxell, L., Conway, J. C., Gentzkow, M., Thaler, M., & Yang, D. Y. (2020). Polarization and Public Health: Partisan Differences in Social Distancing during the Coronavirus Pandemic (Working Paper No. 26946; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26946

Al-Rawi, A. (2019). Gatekeeping Fake News Discourses on Mainstream Media Versus Social Media. Social Science Computer Review , 37 (6), 687–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318795849

Chadwick, A., & Vaccari, C. (2019). News sharing on UK social media: Misinformation, disinformation, and correction [Report]. Loughborough University. https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/News_sharing_on_UK_social_media_misinformation_disinformation_and_correction/9471269

Dechêne, A., Stahl, C., Hansen, J., & Wänke, M. (2010). The Truth About the Truth: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Truth Effect. Personality and Social Psychology Review , 14 (2), 238–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309352251

Donovan, J. (2020). Social-media companies must flatten the curve of misinformation. Nature . https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01107-z

Feezell, J. T. (2018). Agenda Setting through Social Media: The Importance of Incidental News Exposure and Social Filtering in the Digital Era. Political Research Quarterly , 71 (2), 482–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917744895

Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. K. (2018). Are people incidentally exposed to news on social media? A comparative analysis. New Media & Society , 20 (7), 2450–2468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817724170

Fung, I. C.-H., Fu, K.-W., Chan, C.-H., Chan, B. S. B., Cheung, C.-N., Abraham, T., & Tse, Z. T. H. (2016). Social Media’s Initial Reaction to Information and Misinformation on Ebola, August 2014: Facts and Rumors. Public Health Reports , 131 (3), 461–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491613100312

Garrett, R. K. (2019). Social media’s contribution to political misperceptions in U.S. Presidential elections. PLoS ONE , 14 (3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213500

Garrett, R. K., Weeks, B. E., & Neo, R. L. (2016). Driving a Wedge Between Evidence and Beliefs: How Online Ideological News Exposure Promotes Political Misperceptions. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 21 (5), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12164

Guess, A., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Selective Exposure to Misinformation: Evidence from the consumption of fake news during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. European Research Council , 49.

Jamieson, K. H., & Albarracín, D. (2020). The Relation between Media Consumption and Misinformation at the Outset of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in the US. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review , 2 . https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-012

Kim, L., Fast, S. M., & Markuzon, N. (2019). Incorporating media data into a model of infectious disease transmission. PLOS ONE , 14 (2), e0197646. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197646

Kouzy, R., Abi Jaoude, J., Kraitem, A., El Alam, M. B., Karam, B., Adib, E., Zarka, J., Traboulsi, C., Akl, E. W., & Baddour, K. (2020). Coronavirus Goes Viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 Misinformation Epidemic on Twitter. Cureus , 12 (3). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7255

Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., Barthel, M., & Shearer, E. (2016, July 7). The Modern News Consumer. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project . https://www.journalism.org/2016/07/07/the-modern-news-consumer/

Motta, M., Stecula, D., & Farhart, C. E. (2020). How Right-Leaning Media Coverage of COVID-19 Facilitated the Spread of Misinformation in the Early Stages of the Pandemic [Preprint]. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/a8r3p

NewsGuard. (2020). Superspreaders . https://www.newsguardtech.com/superspreaders/

Owen, T., Loewen, P., Ruths, D., Bridgman, A., Gorwa, R., MacLellan, S., Merkley, E., & Zhilin, O. (2020). Lessons in Resilience: Canada’s Digital Media Ecosystem and the 2019 Election . Public Policy Forum. https://ppforum.ca/articles/lessons-in-resilience-canadas-digital-media-ecosystem-and-the-2019-election/

Radzikowski, J., Stefanidis, A., Jacobsen, K. H., Croitoru, A., Crooks, A., & Delamater, P. L. (2016). The Measles Vaccination Narrative in Twitter: A Quantitative Analysis. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance , 2 (1), e1. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.5059

Sharma, M., Yadav, K., Yadav, N., & Ferdinand, K. C. (2017). Zika virus pandemic—Analysis of Facebook as a social media health information platform. American Journal of Infection Control , 45 (3), 301–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2016.08.022

Shin, J., Jian, L., Driscoll, K., & Bar, F. (2018). The diffusion of misinformation on social media: Temporal pattern, message, and source. Computers in Human Behavior , 83 , 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.008

Vicario, M. D., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., Stanley, H. E., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 113 (3), 554–559. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517441113

Weeks, B. E., Lane, D. S., Kim, D. H., Lee, S. S., & Kwak, N. (2017). Incidental Exposure, Selective Exposure, and Political Information Sharing: Integrating Online Exposure Patterns and Expression on Social Media. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 22 (6), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12199

The project was funded through the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Digital Citizens Initiative.

Competing Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board at University of Toronto. Human subjects gave informed consent before participating and were debriefed at the end of the study.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/5QS2XP .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 16 February 2024

Changes in social norms during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic across 43 countries

- Giulia Andrighetto 1 , 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Aron Szekely ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5651-4711 1 , 4 na1 ,

- Andrea Guido 1 , 2 , 5 ,

- Michele Gelfand 6 ,

- Jered Abernathy 7 ,

- Gizem Arikan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2083-7321 8 ,

- Zeynep Aycan 9 , 10 ,

- Shweta Bankar 11 ,

- Davide Barrera ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0441-5073 4 , 12 ,

- Dana Basnight-Brown ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7200-6976 13 ,

- Anabel Belaus ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9657-8496 14 , 15 ,

- Elizaveta Berezina ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1972-8133 16 ,

- Sheyla Blumen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9960-7413 17 ,

- Paweł Boski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0984-5686 18 ,

- Huyen Thi Thu Bui 19 ,

- Juan Camilo Cárdenas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0005-7595 20 , 21 ,

- Đorđe Čekrlija ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8177-8663 22 , 23 ,

- Mícheál de Barra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4455-6214 24 ,

- Piyanjali de Zoysa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7382-6503 25 ,

- Angela Dorrough ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5645-949X 26 ,

- Jan B. Engelmann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6493-8792 27 ,

- Hyun Euh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0972-1640 28 ,

- Susann Fiedler ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9337-2142 29 ,

- Olivia Foster-Gimbel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4583-3060 30 ,

- Gonçalo Freitas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5888-3000 31 ,

- Marta Fülöp 32 , 33 ,

- Ragna B. Gardarsdottir ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3368-4616 34 ,

- Colin Mathew Hugues D. Gill ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3225-246X 16 , 35 ,

- Andreas Glöckner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7766-4791 26 ,

- Sylvie Graf ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7810-5457 36 ,

- Ani Grigoryan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5453-2879 37 ,

- Katarzyna Growiec ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4448-2561 18 ,

- Hirofumi Hashimoto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3648-9912 38 ,

- Tim Hopthrow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2331-7150 39 ,

- Martina Hřebíčková ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8700-1326 36 ,

- Hirotaka Imada ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3604-4155 40 ,

- Yoshio Kamijo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2184-9594 41 ,

- Hansika Kapoor ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0805-7752 42 ,

- Yoshihisa Kashima 43 ,

- Narine Khachatryan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3590-7131 37 ,

- Natalia Kharchenko 44 ,

- Diana León ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4596-3858 45 ,

- Lisa M. Leslie 30 ,

- Yang Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8239-3279 46 ,

- Kadi Liik ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5166-9893 47 ,

- Marco Tullio Liuzza ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6708-1253 48 ,

- Angela T. Maitner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3896-5783 49 ,

- Pavan Mamidi 11 ,

- Michele McArdle 8 ,

- Imed Medhioub ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4676-7330 50 ,

- Maria Luisa Mendes Teixeira ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0606-1723 51 ,

- Sari Mentser ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1520-8253 52 ,

- Francisco Morales ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0785-8838 53 ,

- Jayanth Narayanan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2720-1593 54 ,

- Kohei Nitta 55 ,

- Ravit Nussinson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7331-548X 56 , 57 ,

- Nneoma G. Onyedire ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4941-2300 58 ,

- Ike E. Onyishi 58 ,

- Evgeny Osin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3330-5647 59 ,

- Seniha Özden 9 ,

- Penny Panagiotopoulou 60 ,

- Oleksandr Pereverziev 61 ,

- Lorena R. Perez-Floriano ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6898-7794 62 ,

- Anna-Maija Pirttilä-Backman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7437-9645 63 ,

- Marianna Pogosyan 64 ,

- Jana Raver 65 ,

- Cecilia Reyna ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6097-4961 14 ,

- Ricardo Borges Rodrigues 66 ,

- Sara Romanò 12 ,

- Pedro P. Romero ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2616-4498 67 , 68 ,

- Inari Sakki ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8717-5804 63 ,

- Angel Sánchez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1874-2881 69 , 70 ,

- Sara Sherbaji ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7815-8962 49 , 71 ,

- Brent Simpson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9468-157X 7 ,

- Lorenzo Spadoni ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1208-2897 72 ,

- Eftychia Stamkou 73 ,

- Giovanni A. Travaglino ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4091-0634 40 ,

- Paul A. M. Van Lange ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7774-6984 74 ,

- Fiona Fira Winata 75 ,

- Rizqy Amelia Zein ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7840-0299 75 ,

- Qing-peng Zhang 76 &

- Kimmo Eriksson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7164-0924 2 , 77 , 78

Nature Communications volume 15 , Article number: 1436 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

4273 Accesses

1 Citations

33 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

The emergence of COVID-19 dramatically changed social behavior across societies and contexts. Here we study whether social norms also changed. Specifically, we study this question for cultural tightness (the degree to which societies generally have strong norms), specific social norms (e.g. stealing, hand washing), and norms about enforcement, using survey data from 30,431 respondents in 43 countries recorded before and in the early stages following the emergence of COVID-19. Using variation in disease intensity, we shed light on the mechanisms predicting changes in social norm measures. We find evidence that, after the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, hand washing norms increased while tightness and punishing frequency slightly decreased but observe no evidence for a robust change in most other norms. Thus, at least in the short term, our findings suggest that cultures are largely stable to pandemic threats except in those norms, hand washing in this case, that are perceived to be directly relevant to dealing with the collective threat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Evidence from 43 countries that disease leaves cultures unchanged in the short-term

Social and moral psychology of COVID-19 across 69 countries

Predictors of adherence to public health behaviors for fighting COVID-19 derived from longitudinal data

Introduction.

Societies vary extensively in the kinds and number of social norms—the unwritten social rules that guide behavior 1 , 2 —that they adopt and the extent to which people within those societies follow them. From religious ceremonies and dress codes to environmental conservation and infection-containment, we embrace an astonishing diversity of social norms. An influential theory proposes that societies with many strong social norms, and in which individuals who deviate from the script face severe social punishment, can be classified as tight, while those that are permissive, have few and weak social norms, and norm-breakers are subject to little punishment are known as loose 3 , 4 . Such differences in cultural tightness are also reflected in prevailing socio-political institutions and practices. Tighter countries, or regions, are likelier to have restrictive socio-political institutions (e.g., government, media, education, legal, and religious), stricter constraints across everyday situations (e.g., public park, library, restaurant, workplace, classroom), more incremental innovation, lower debt, and stronger metanorms (norms about punishment) among others 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 . Loose cultures are instead more open to new ideas, more predisposed to change and substantial innovation, but may have difficulties in facing collective risks. Indeed, recent work finds that looser societies had less success in limiting COVID-19 cases and deaths in the first stages of the pandemic 12 .

Given the broad practical and scientific importance of tightness-looseness, it is essential to understand what factors are associated with these differences across countries and cultures. Tightness-Looseness theory 3 contends that societies that have experienced chronic ecological and social threats—frequent disease, warfare, and environmental catastrophes—throughout history develop tighter cultures to maintain order and survive chaos and crises. In contrast, societies with less exposure to such ecological threats can afford to develop looser cultures that allow innovation and creativity at the cost of order. This core hypothesis, that social norm strength is related to the threats that nations have (or have not) historically encountered, is well supported by correlational evidence from cross-sectional surveys 3 , 6 , 7 , ethnographic datasets 8 , a long-term online experiment 13 , and a long-term survey about social distancing norms 14 . Moreover, computational models have shown that dramatic increases in threat cause tightening 15 . On the other hand, cultural evolution has been argued to be a slow process 16 , 17 , suggesting the alternative that norm strength is stable after a collective threat. The COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity to examine whether tightening naturally occurs or if culture remains stable in the early stages of a collective threat. This knowledge can help us not only predict the future responses of countries to similar situations and potentially identify effective interventions to deal with these crises but also to better anticipate social changes that can impact our societies for generations to come.

Here we address this question by studying a dataset on cultural tightness, social norms, and metanorms—norms about the punishment of norm-breakers 18 —and exploit variation in disease severity due to the COVID-19 pandemic to test whether tightening evolves after a collective threat. Specifically, we combine data from a survey collected between April–December 2019 (Wave 1) 5 prior to the pandemic with a repeat of the same survey, in the same countries and sampled from the same populations, that we conducted in March–July 2020 (Wave 2) during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. The combined data come from 30,431 respondents (samples from both students and non-students) and cover 55 cities in 43 countries (see Table S1 for summary).

The follow-up data (Wave 2) were collected during the initial stages of the pandemic so they capture the early changes (or their stability) in norms that occurred. While this means that we cannot infer the long-run consequences of the pandemic on norms, it also presents important advantages. First, our data provide an insight into norm change under extreme circumstances—while social, political, and economic systems were in upheaval—which provides strong stimuli for change to occur potentially shaping norms. Put differently, if norm change occurs, then there is a good chance we should be able to observe this in the early stages. Second, early data give an insight into the non-equilibrium dynamics of how cultures move from one stable state to another. Third, we are able to test the boundaries of tightness-looseness theory in terms of timeline: our data indicate a lower bound on the time that may be needed for large-scale norm change to occur in response to pandemic threat. Fourth, endogeneity issues are reduced. Specifically, it reduces the possibility for other large-scale shocks to affect the data and the possibility of time varying factors (e.g. hospital infrastructure development) to confound our results.

To study whether a change in disease threat is associated with a change in norms, we study five outcomes. (i) Tightness-looseness: elicited using the standard six questions (e.g., “There are many social norms that people are supposed to abide by in this country”) with ratings standardized to control for response sets 3 , 5 . (ii) Situation-specific social norms’ strength: measured with disapproval of norm-breaking in four settings (e.g., listening to music on headphones at a funeral 19 ) and stealing shared resources 20 . (iii) Metanorm strength: for each of the prior scenarios respondents also rated the appropriateness of different responses to the norm-breaker by another individual (verbal confrontation, ostracism, gossip, physical punishment, and non-action) 5 , 18 . (iv) Frequency of punishing norm-breakers. (v) Hand washing norms: respondents indicated the situations (e.g., after shaking someone’s hand) in which people should wash their hands. Our core expectation is that these outcomes are higher after the emergence of COVID-19 than before.

These outcomes vary in their relevance to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hand hygiene is strongly related, stealing is partly related (i.e. stealing shared resources during a pandemic is particularly harmful), while others, such as listening to music on headphones at a funeral, are unrelated to the pandemic. Intuitively, norms most related to preventing disease spread should change the most. Yet tightness-looseness theory does not make such detailed predictions. Instead, it proposes the overarching hypothesis that norms and metanorms strengthen. Such a broad change may happen for two interlinked reasons: in the presence of threats, people rely more on social norms as heuristics to safely determine what to do and this increase in conformity leads to a general tightening 21 ; it is beneficial to have tight norms across the board since tightening even irrelevant norms can increase a general norm-following tendency that implies increased norm-following for the more relevant ones.

To gain a deeper insight into the mechanisms that may be associated with change, we exploit the heterogeneity across countries in their exposure to COVID-19 and we collected data on three pathways through which we conjecture that COVID-19 pandemics may shape norms. Two of these are the respondent’s beliefs about the prevalence of COVID-19 and their fear of COVID-19, as we conjecture that disease threat shapes the strength of norms through individuals’ perceptions. The final pathway concerns government policy. By implementing strict (or lenient) anti-disease policies, governments can signal to their citizens the severity of the threat. Moreover, they impose policies that change their citizens’ behavioral patterns (e.g., not shaking hands, socially isolating) and these may have consequences on social expectations and norms. While all countries in the sample have been exposed to the pandemic, the continuous variation in our collected measures helps shed light on the association between cultural change and intensity of COVID-19 pandemic. The study, including the hypotheses and analyses, was pre-registered with the Open Science Framework (see Methods).

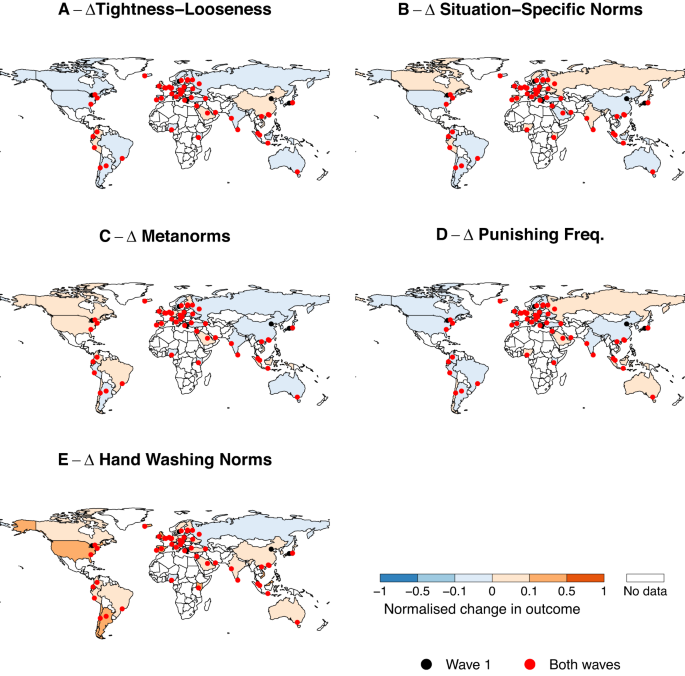

Overall, we find that in the short term, the global threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a significant strengthening of social norms related to hand washing, a behavior highly relevant to limit disease spread. Contrary to our initial predictions, other established social norms governing our daily lives exhibit resilience and remain largely unchanged. In addition, cultural tightness slightly decreased accompanied by small decrease in punishment frequency. These findings suggest that the immediate impact of a global threat is selective in changing those norms that are directly relevant to cope with the threat and emphasizes the adaptive nature of societies in the face of a collective crisis.

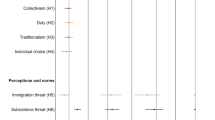

Our analytic strategy proceeds in two stages. We first compare Wave 1 to Wave 2 averages using multilevel models with individual responses grouped on city and country. We then seek to identify the mechanisms associated with changes for only those outcomes that show significant associations which are robust across both models and sub-items. To do this we use the change across waves (Wave 2 - Wave 1) as the dependent variable as predicted by perceived prevalence, fear, and government stringency and use country-level observations and OLS regression models with heteroskedastic robust standard errors. Prevalence is measured using “What percent of people living in your province do you think have been infected with COVID-19?” and fear is the combination of three items (Cronbach’s α = 0.84, see Methods for country-level variation). To capture variation in governmental policies, we use the Stringency Index from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker 22 .This second stage of our analysis is similar in spirit to a difference-in-differences design but differs to the classical setup in that we have no entirely untreated control group—all countries in our sample were to some extent affected by the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic—and instead of a treated and untreated group, we have many groups with different COVID-19 pandemic exposure levels. All analyses account for age, gender, and student status to control for any sample composition differences between the waves (see Methods). We also check whether deaths and cases, which account for the different levels of COVID-19 across countries, affect our results and find that they do not (see Supplementary Materials ).

After our analyses were conducted, we added equivalence tests using the two one-sided tests procedure 23 , 24 , 25 to identify whether significant changes that we find are practically meaningful and if non-significant findings provide evidence for the absence of a meaningful change. In this procedure, we specify a series of smallest effect size of interest (SESOI) and then compare Wave 1 to Wave 2 changes and the mechanism associations to these SESOIs. Our SESOIs were set ex-post and not pre-registered and, given the lack of existing literature, or even data, concerning the changes in our outcome variables, there is large uncertainty about how the SESOI should be set (see Methods for discussion). Consequently, we use a benchmark-based approach and set the SESOI to Cohen’s d = 0.1 (a small effect size 26 ) for our main individual-level analyses and β = ± 0.10 (a small effect size 26 ) for the mechanisms analyses (see Methods for details).

Tightness-Looseness

Tightness decreases (x̅ 1 = 1.90, x̅ 2 = 1.81; Fig. 1A ; Table S1 ) although the effect size is small (Cohen’s d = 0.11; b = −0.028, 95% CI = [−0.047; −0.009], p = 0.003; Table S2 ), and the change is heterogeneous across countries (varying slope model: b = −0.037, 95% CI = [−0.073; −0.001], p = 0.042; random effect variance τ 11 = 0.01; Table S2 ; Figure S2 ). In most countries, the change is not significant (81.4%; 35/43), it is negative in 16.3% (7/43) and even positive in 2.3% (1/43) (Fig. S2 ). Countries that have higher fear levels towards COVID-19 reduced their tightness the most ( b = −0.081, 95% CI = [−0.157; −0.005], p = 0.037; Table S3 ) though this association is small. Perceived prevalence and government stringency are not significantly associated with change in tightness-looseness ( b = −0.003, 95% CI = [−0.010; 0.003], p = 0.306 and b = 0.0003, 95% CI = [−0.002; 0.001], p = 0.721, respectively; Table S3 ).