Surveys and questionnaires in nursing research

Affiliation.

- 1 Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

- PMID: 26080989

- DOI: 10.7748/ns.29.42.42.e8904

Surveys and questionnaires are often used in nursing research to elicit the views of large groups of people to develop the nursing knowledge base. This article provides an overview of survey and questionnaire use in nursing research, clarifies the place of the questionnaire as a data collection tool in quantitative research design and provides information and advice about best practice in the development of quantitative surveys and questionnaires.

Keywords: Data collection; nursing research; qualitative research; quantitative research; questionnaire; research; survey; validity.

- Nursing Research / methods*

- Surveys and Questionnaires* / standards

- NCSBN Member Login Submit

Access provided by

Login to your account

If you don't remember your password, you can reset it by entering your email address and clicking the Reset Password button. You will then receive an email that contains a secure link for resetting your password

If the address matches a valid account an email will be sent to __email__ with instructions for resetting your password

Download started.

- Academic & Personal: 24 hour online access

- Corporate R&D Professionals: 24 hour online access

- Add To Online Library Powered By Mendeley

- Add To My Reading List

- Export Citation

- Create Citation Alert

Survey Research: An Effective Design for Conducting Nursing Research

- Vicki A. Keough, PhD, RN-BC, ACNP Vicki A. Keough Affiliations Dean and Professor at Loyola University Chicago, Marcella Niehoff School of Nursing, Maywood, Illinois Search for articles by this author

- Paula Tanabe, PhD, MPH, RN Paula Tanabe Affiliations Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine and the Institute for Healthcare Studies at Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois Search for articles by this author

Purchase one-time access:

- For academic or personal research use, select 'Academic and Personal'

- For corporate R&D use, select 'Corporate R&D Professionals'

- Clarke S.P.

- Silber J.H.

- Google Scholar

- Blegen M.A.

- Gearhart S.

- Sehgal N.L.

- Alldredge B.K.

- Scopus (119)

- Brommage D.

- Full Text PDF

- Dillman D.A.

- Draugalis J.R.

- Scopus (283)

- Edwards P.J.

- Clarke M.J.

- DiGuiseppi C.

- Grava-Gubins I.

- Keating N.L.

- Zaslavsky A.M.

- Goldstein J.

- Ayanian J.Z.

- Scopus (50)

- Kleinpell R.M.

- McPherson L.

- Leverene R.

- The Prime Net Consortium

- Scopus (48)

- McCabe S.E.

- Nelson T.F.

- Weitzman E.R.

- Scopus (83)

- Thornlow D.

- Nicotera N.

- Scopus (56)

- Paulhus D.L.

- Scopus (10)

- Ryan M.A.K.

- Scopus (163)

- McLean S.L.

- Scopus (160)

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration

- • Describe the steps of the survey research project.

- • Differentiate survey research methods.

- a. social desirability

- b. social status.

- c. validated practice.

- d. validated response.

- a. Web-based

- b. Face-to-face interviews

- c. U.S. mail

- a. They have the potential for researcher bias.

- b. They are time consuming.

- c. They reach too many participants.

- d. They have the potential for subject bias.

- a. A signed consent form from each participant is required.

- b. Approval from an institutional review board is not needed.

- c. Informed consent is implied when the survey is completed and returned.

- d. Respondents cannot be asked for information that would identify them.

- a. Purposive sample

- b. Population study

- c. Target survey

- d. Subset sample

- a. A questionnaire sent by registered mail

- b. A questionnaire that is at least 10 pages long

- c. Four contacts by mail followed by a "special" contact

- d. The addition of a form letter to the questionnaire

- a. outcome validity.

- b. inter-rater validity.

- c. face validity.

- d. construct validity.

- a. Outcome validity

- b. Inter-rater validity

- c. Face validity

- d. Construct validity

- a. inter-rater reliability.

- b. intra-rater reliability.

- c. concept validity.

- d. database validity.

- a. send the surveys out in waves.

- b. send all surveys out at one time.

- c. hold data entry until the end of data collection.

- d. hold data cleaning until the end of data collection.

- a. Statistical techniques should be independent of the design.

- b. Statistical techniques should match the design.

- c. Regression models should be used in the analysis.

- d. Pattern testing should be used in the analysis.

- c. Data analysis

- d. Discussion

- • Describe the steps of the survey research project. 1 2 3 4 5 ______________

- • Differentiate survey research methods. 1 2 3 4 5 ______________

- 2 Were the authors knowledgeable about the subject? 1 2 3 4 5 ______________

- 3 Were the methods of presentation (text, tables, figures, etc.) effective? 1 2 3 4 5 ______________

- 4 Was the content relevant to the objectives? 1 2 3 4 5 ______________

- 5 Was the article useful to you in your work? 1 2 3 4 5 ______________

- 6 Was there enough time allotted for this activity? 1 2 3 4 5 ______________ Comments: ______________ ______________ ______________ ______________ ______________ ______________

- □ Member (no charge)

- □ Nonmembers (must include a check for $15 payable to NCSBN)

Article info

Identification.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30315-X

ScienceDirect

Related articles.

- Download Hi-res image

- Download .PPT

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Current Issue

- List of Issues

- Supplements

- For Authors

- Guide for Authors

- Author Services

- Permissions

- Researcher Academy

- Submit a Manuscript

- Journal Info

- About the Journal

- Contact Information

- Editorial Board

- New Content Alerts

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

Session Timeout (2:00)

Your session will expire shortly. If you are still working, click the ‘Keep Me Logged In’ button below. If you do not respond within the next minute, you will be automatically logged out.

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

- Forming Evidence-Based (EBP) Questions

- Reference Sources

- Drugs, Patient Care and Education

- Article Databases

Narrowing a Clinical Question

Two types of clinical questions, what is pico anyway, picott alternatives and additions, pico process in action, using pico to form the research question, tips and tricks.

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Psychological Tests

- Web Resources

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Citation Guides

- Mobile Applications

- Unit Recommended Online Journals

- Resource Types and Evaluating Information

- Investigate

- Tools and Resources

To begin to develop and narrow a clinical research question it is advisable to craft an answerable question that begins and ends with a patient, population, or problem. These are the beginnings of not only developing an answerable EBP question, but also using the PICO process for developing well-built searchable and answerable clinical questions.

There are many elements to developing a good clinical question. Clinical questions can be further divided into two major areas: Background Questions and Foreground Questions .

Background Questions refer to general knowledge and facts. The majority of the information that can be used to inform answers to background questions are found in reference resources like Encyclopedias, Dictionaries, Textbooks, Atlases, Almanacs, Government Publications & Statistical Information, and Indexes.

Foreground Questions are generally more precise and usually revolve around patient/s, populations, or a specific problem. Crafting an appropriate EBP question will not only inform your search strategy which you will apply to the medical literature but will also create a framework for how to maintain and develop your investigative process.

What are some examples of P ?

- Diabetes mellitus, Type 2 (problem) Obese

- elderly (population)

What are some examples of I ?

- Chlorpropamide

What are some examples of C ?

What are some examples of O ?

- Management of glucose levels

Using the example from the bottom-center we can start forming a research question:

Is Chlorpropamide (intevention) more efficient than Metformin (comparator) in managing Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 (problem) for obese elderly patients (population)?

*Note: It is not necessary to use every element in PICO or to have both a problem and population in your question. PICO is a tool that helps researchers frame an answerable EBP question.

Synonyms can very helpful throughout your investigative and research process. Using synonyms with boolean operators can potentially expand your search. Databases with subject headings or controlled vocabularies like MeSH in PubMed often have a thesaurus that can match you with appropriate terms.

Boolean operators allow you to manipulate your search.

Use AND to narrow your search

eg. elderly AND diabetes

Use OR to broaden your search

eg. myocardial infarction OR heart attack

Use NOT to exclude terms from your search

eg. children NOT infants

- << Previous: Article Databases

- Next: Evidence-Based Practice >>

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 11:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/nursing

- Login / Register

‘Much will be said and promised over the next six weeks’

STEVE FORD, EDITOR

- You are here: Nurse managers

Using online questionnaires to conduct nursing research

23 November, 2008 By NT Contributor

This article explores the concept of using online questionnaires to carry out nursing research. It discusses options for nurses who do not have advanced technical IT skills for electronic distribution of survey questionnaires.

The general principles of web distribution are explained, and some approaches are evaluated in terms of current access to technology and its ease of use. The article also offers some practical advice for nurse researchers, and examines the advantages and disadvantages of using this new method of data collection, compared with traditional hard copy.

Jones, S. et al (2008) Using online questionnaires to conduct nursing research. Nursing Times ; 104: 47, 66–69.

Authors Steve Jones, MBA, BA, CertEd (FE), RMN, DN, is lecturer and head of information technology; Fiona Murphy, MSc, PGCE (FE), BN, NDN, RCNT, HV, RN, is senior lecturer; Mark Edwards, BSc, RN, is tutor; Jane James, MSc, RN, is tutor; all at School of Health Science, University of Wales Swansea.

Download a print-friendly PDF of this article

Introduction

Increasingly, there is an expectation that nurses and other health care professionals will be involved in research and audit activities and will use the findings from these activities to inform their clinical practice. They are expected to be able to critically appraise evidence from research, be involved in conducting and contributing to audit and be actively involved in undertaking research projects themselves. This requires knowledge about research and in particular the methods that could be used to collect data.

A popular method of collecting data is through surveys, which involves using questionnaires. These are designed through the careful construction of questions to identify facts and opinions from specific groups of respondents (Denscombe, 2003). Using a questionnaire to gather research data is often an attractive proposition as they are arguably more precise and focused than alternative methods such as interviewing and observation by researchers.

The advantages and disadvantages of their use have been widely debated (McKenna et al, 2006; Giuffre, 1997). The main advantage of well-constructed questionnaires appears to be that they enable researchers to easily collect relatively unambiguous data which lends itself to quantitative data analysis (Bowling, 2002). However, questionnaires also have their disadvantages, one of which is that they often achieve a poor rate of return, leading to low response rates.

Two further problems relate to issues of control and transcription. The control issue occurs where researchers have no control over the order in which respondents answer questions (which might be critical to the study), no facility to check on incomplete responses or incomplete questionnaires, and no ability to prevent the questionnaires being passed on to others (Oppenheim, 1992). The transcription issue relates to the task of accurately reading the data from the finished questionnaire – and manually entering it into the analysis software. This is where transcription errors may creep in – particularly where a respondent’s handwriting is difficult to decipher.

Administering questionnaires

Questionnaires can be administered in a variety of ways. They can be distributed by hand or by post, or sent by email to be printed out, completed and then returned.

A newer alternative approach is to deliver the questionnaire entirely electronically via the internet, as an online questionnaire. Respondents access the web page, read the questionnaire and enter their responses directly on to the page.

Online questionnaires have the advantages of hard copy but also have features which make spoiled and incomplete responses impossible to submit. For example, respondents can be guided through the process to ensure they complete the questionnaire fully, properly and in the correct order before they are able to submit it (Solomon, 2001). This overcomes the control issue associated with hard copy.

Another advantageous feature of online questionnaires is that the data analysis tools will either be an integral part of the website or data can be copied or ported directly into analysis software such as SPSS or Microsoft Excel. Typically both options are offered. This means the results are available as the data is entered, and transcription errors and the chore of manual data entry into separate analysis software are eliminated.

However, the problem of low response rates associated with questionnaires remains. In fact there is evidence that the rates are lower for online surveys than for postal surveys (Solomon, 2001). Although these findings are from research carried out almost a decade ago they may still apply.

In a large study conducted in Norway, researchers found that adding the option to respond to a questionnaire via the internet did not significantly increase the overall response to a postal survey (Brøgger et al, 2007). In another large study in Sweden, the return rate for the online version of a questionnaire was 15% compared with 55% for the postal version (Dannetun et al, 2007).

However, it is worth noting that in both the above studies participants were selected randomly. Whitehead (2007) found evidence that response rates for internet-mediated surveys are lower when the request is unsolicited. However, they can still be as high or higher than postal surveys in which people are recruited either face-to-face or online.

Research in practice

An assumption behind this article is that nurses undertaking research are not likely to be targeting large numbers of people at random. Since email is increasingly used as the system of choice for keeping in touch with patient groups, it seems reasonable that web links to research questionnaires could be appended or attached to emailed documents such as appointment reminders, in the same way they are sometimes enclosed with postal versions.

In the surveys cited where low response rates have been reported (Brøgger et al, 2007; Dannetun et al, 2007), login credentials have always been sent to potential respondents by post. The Swedish respondents were offered a choice of completing the form contained in the envelope they had just opened, or turning on their computer, finding the site, successfully logging in and then completing and submitting the same questionnaire online (Dannetun et al, 2007).

The proposal here is that links to questionnaires should be integrated into patients’ ordinary interaction with the health service. They will be sitting at their computer and logged in when they first encounter the questionnaire. So, while it seems people are reluctant to go to the trouble of responding to a web address printed on hard copy – particularly if this is unsolicited – the invitation to click on a link in an already open email is probably a more attractive option. It is also less intrusive than either hard copy or telephone follow-up and works asynchronously, in that patients can respond in their own time.

Including a questionnaire within routine support from their usual health care provider also offers patients assurance they are not responding to a commercial study, as may happen if they arrive at a questionnaire through using a search engine (Etter, 2006). A wide range of data could be collected using questionnaires in this way, such as feedback on the nature and type of post-operative pain or discomfort patients experience, or on particular difficulties they have encountered after discharge. They could even be used to give patients the opportunity to rate aspects of care they received while in hospital.

Technological capabilities

The question remains as to whether or not the target client group for web questionnaires exists, even assuming that nurses are now beginning to embrace a technology they have been hitherto slow to use and adopt (Im and Chee, 2001). However, there is no doubt that in the general population people are more technologically competent than ever before.

Whitehead (2007) identified older adults to be the fastest growing group of internet users. Since this is the most likely target demographic for ex-patient surveys run by nurses it seems likely there is a growing body of potential respondents, as well as access to the sort of technology needed to deliver a survey electronically.

Delivering online questionnaires

To successfully administer an online questionnaire it is necessary to have some degree of IT knowledge or at least to have access to someone with that knowledge. It is probably appropriate to explain here how an online survey works.

Most everyday computer systems still work on the ‘client server’ principle. The ordinary person uses a client computer, which interacts with a remote server computer holding their information store. Data is sent between the client computer, where it is processed, and the server where it is stored.

At the client end is the web-browser, such as Internet Explorer, or perhaps Fire Fox, which loads and displays the questionnaire pages from the website located on the remote server. Any data entered into a questionnaire at the client end is transferred to the website on the remote server, usually by hitting a submit button.

Provided a researcher has the technical skills, or access to someone else who does, the easiest way to manage the delivery of an online questionnaire and the subsequent collection, analysis and storage of data is to have complete control of both ends of this operation.

Unfortunately, this approach is really only suitable for technically able people or for those with unrestricted access to sophisticated IT support. Even today, releasing an online survey is not as simple as creating a questionnaire in Microsoft Word, copying it to a website and then sending around the web address. Any data entered into the questionnaire has to be passed to a database somewhere.

To create this database and link it to the questionnaire is quite technically demanding, and the systems that permit this such as Adobe Enterprise Server are not suitable for people who have only average IT skills.

However, this is far from the only way to deliver an online questionnaire. There are at least three simpler alternatives (Box 1), all three of which involve renting or borrowing space on someone else’s computer, putting the questionnaire on that, and letting the service provider, who has all the IT expertise required, manage the collection and storage of the data.

As usual, in doing things this way, there is a trade-off between the amount of flexibility in the questionnaire creation tools and their ease of use. And, although typically time-limited or restricted demonstrations are free, there will always be a charge for the full version of these products and services.

Using an existing service

The first, simplest and cheapest approach of all, but one really only open to educators, is to exploit the capabilities of whatever virtual learning environment (VLE) is used by the individual researcher’s organisation. The two market leaders are Blackboard – which is used in many universities, and Moodle – the choice of the Open University and many NHS trusts. Both have questionnaire creation modules. A disadvantage to most researchers, other than the simplicity of what is possible, is that potential respondents would need to have an account on the VLE; this means they need to be students at least in name.

Adding a PC application

A better option might be Email Questionnaire 4.15 by CompressWeb, which costs just over £50 for the standard version. This is an example of an application that runs on the PC within Microsoft Outlook or Outlook Express and allows the construction of quite sophisticated questionnaires. It also provides an extensive library of ready-made templates and a variety of reports. A disadvantage for novices is that they may need to know something about their email service, the name, for example, of their ‘PoP server’ – the computer which sends them their internet email. Another requirement is that the software be installed on the PC rather than accessed via the web. This means users need sufficient IT skills and sufficient rights on the PC to do this.

Using a web service

A simpler but slightly more expensive option is to use a web-based questionnaire builder. This requires little more IT skill than the ability to create an account on a website. The site will not interact with the user’s PC other than to send emails confirming, for example, that ‘your questionnaire is launched’. The questionnaire can be distributed by email attachment, by simply sending the web link to potential respondents, but it is not restricted to email recipients running particular email programmes as it runs entirely within the web-browser.

An example, currently costing around £175, is ‘Zoomerang’. Like Email Questionnaire 4.15, Zoomerang offers a range of questionnaire templates. An advantage of using a template, rather than designing a screen from scratch, is that there is no need to worry about design or technical issues, such as keeping the relationship between the elements on the page consistent at different screen resolutions. All this is taken care of, and logos and graphics can be easily added to the basic pages.

Other alternatives

In this article only one application of each type has been examined. Table 1 offers a list of similar alternatives, which would work in similar ways (this list is not exhaustive). Wright (2005) offered a comparative analysis of such products (company mergers have taken place since that evaluation). Of the applications evaluated, only one seems to allow questions to be spread over a number of pages but this may be no bad thing as the requirement to scroll may increase the speed at which questionnaires are completed (Manfreda et al, 2002), and simplify navigation.

Ethical considerations

Electronic data poses a special challenge. Unlike hard copy, it is easy to transmit and duplicate and will be collected using the internet, the electronic infrastructure that supports the worldwide web. Before using electronic means of data collection, in addition to providing the usual letter of explanation and asking for patients’ consent, nurse researchers should ensure the system chosen is acceptable to local IT management, and is in line with local and national connection policies. In practice, it would be better to approach the IT department early and ensure they are happy about the plans before arranging the normal ethical review, as this might save some work. It is also possible they will have encountered people in the area using web questionnaires, or will know of reliable service providers, and will be able to provide some specific support.

Another consideration is that delivering a questionnaire by email, or via patients’ login to a service, targets them personally. This may convince them, despite reassurances to the contrary, that they can be identified in a completed return. Sometimes this may not matter, as they may want to be identified. However, where anonymity is an issue, fear of breach of confidentiality has been identified as a key element affecting survey response rates (Dillman, 2000) and fears of identification associated with non-response (Saewyc et al, 2004; Morrel-Samuels, 2003). Recent research has identified this as a significant determinant of the quality and level of return, even in a highly structured environment with full control over the technology, with participants invited to attend timetabled sessions in PC labs to respond to the questionnaire (Jones et al, 2008).

It is also important to consider the security of data collected. If an individual’s record could be identified from the data collected, then the obligations towards personal data under the Data Protection Act 1998 will apply. If, on the other hand, the data is fully anonymised it will not apply. Difficulties exist where, although personal identifiers are not collected, it may still be possible to deduce patients’ identity from other data in the record. If there is any doubt, clearance should be sought from the organisation’s data protection officer. The Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology has provided advice on this point. In addition, data collected and downloaded will need to be stored safely.

Questionnaires will remain an important method of data collection. The opportunity to deliver these via the internet brings some key advantages but also some challenges. The main issue currently is the need to have a degree of IT expertise in order to distribute the questionnaires. The technology remains a challenge, both for would-be researchers and for respondents. It seems responses tend to come mainly from experienced computer users who find completing a questionnaire with a mouse easy and straightforward (Kiernan et al, 2005). People who are not as accustomed to using computers need some preparation, support and follow-up (Hayslett and Wildemuth, 2004).

Rising to this challenge will become easier as internet use increases and new products arrive on the market designed to allow professionals with no specialist IT skills to create their own online questionnaires. Although there is always a learning curve in using the internet to conduct surveys, like most applications of technology, once basic skills have been learnt the relative effortlessness of this method makes the earlier ‘hard copy’ approach unappealing. Other important considerations, such as assuring respondents of the anonymity and confidentiality of their participation, remain a challenge.

Bowling, A. (2002) Research Methods in Health. Investigating Health and Health Services (2nd ed). Buckingham: Open University Press.

Brøgger, J. et al (2007) No increase in response rate by adding a web response option to a postal population survey: a randomized trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research ; 9: 5, e40.

Dannetun, E. et al (2007) Parents’ attitudes towards hepatitis B vaccination for their children. A survey comparing paper and web questionnaires , Sweden 2005. BMC Public Health; 7: 86.

Denscombe, M. (2003) The Good Research Guide for Small Scale Research Projects (2nd ed). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Dillman, D.A. (2000) Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method . New York, NY: Wiley.

Etter, J. (2006) Internet-based smoking cessation programs. International Journal of Medical Information ; 75: 1, 110–116.

Giuffre, M. (1997) Designing research survey design: part two. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing ; 12: 5, 358–362.

Hayslett, M.M., Wildemuth, B.M. (2004) Pixels or pencils? The relative effectiveness of web-based versus paper surveys. Library and Information Science Research ; 26: 1, 73–93.

Im, E., Chee, W. (2001) A feminist critique of the use of the internet in nursing research. Advances in Nursing Science ; 23: 4, 67–82.

Jones, S. et al (2008) Doing things differently: advantages and disadvantages of web questionnaires. Nurse Researcher ; 15: 3, 15–26.

Kiernan, N.E. et al (2005) Is a web survey as effective as a mail survey? A field experiment among computer users. American Journal of Evaluation ; 26: 2, 245–252.

Manfreda, K.L. et al (2002) Design of web survey questionnaires: three basic experiments. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication ; 7: 3.

McKenna, H.P. et al (2006) Surveys. In: Gerrish, K., Lacey, A. (eds) The Research Process in Nursing (5th ed). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Morrel-Samuels, P . (2003) Web surveys hidden hazards. Harvard Business Review ; 81: 7, 16–18.

Oppenheim, A.N . (1992) Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement. London: Pinter Publishers.

Saewyc, E.M. et al (2004) Measuring sexual orientation in adolescent health surveys: evaluation of eight school-based surveys. Journal of Adolescent Health ; 35: 4, 345e1–15.

Solomon, D.J. (2001) Conducting web-based surveys. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation ; 7: 19.

Whitehead, L.C. (2007) Methodological and ethical issues in internet-mediated research in the field of health: an integrated review of the literature. Social Science and Medicine ; 65: 4, 782–791.

Wright, K.B. (2005) Researching internet-based populations: advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication ; 10: 3, article 11.

Related files

081125using online questionnaires to conduct nursing research.

- Add to Bookmarks

Have your say

Sign in or Register a new account to join the discussion.

PICOT Question Examples for Nursing Research

Are you looking for examples of nursing PICOT questions to inspire your creativity as you research for a perfect nursing topic for your paper? You came to the right place.

We have a comprehensive guide on how to write a good PICO Question for your case study, research paper, white paper, term paper, project, or capstone paper. Therefore, we will not go into the details in this post. A good PICOT question possesses the following qualities:

- A clinical-based question addresses the nursing research areas or topics.

- It is specific, concise, and clear.

- Patient, problem, or population.

- Intervention.

- Comparison.

- Includes medical, clinical, and nursing terms where necessary.

- It is not ambiguous.

For more information, read our comprehensive PICOT Question guide . You can use these questions to inspire your PICOT choice for your evidence-based papers , reports, or nursing research papers.

If you are stuck with assignments and want some help, we offer the best nursing research assignment help online. We have expert nursing writers who can formulate an excellent clinical, research, and PICOT question for you. They can also write dissertations, white papers, theses, reports, and capstones. Do not hesitate to place an order.

List of 180 Plus Best PICOT Questions to Get Inspiration From

Here is a list of nursing PICO questions to inspire you when developing yours. Some PICOT questions might be suitable for BSN and MSN but not DNP. If you are writing a change project for your DNP, try to focus on PICOT questions that align to process changes.

- Among healthy newborn infants in low- and middle-income countries (P), does early skin-to-skin contact of the baby with the mother in the first hour of life (I) compared with drying and wrapping (C) have an impact on neonatal mortality, hypothermia or initiation/exclusivity/ duration of breastfeeding (O)?

- Is it necessary to test blood glucose levels 4 times daily for a patient suffering from Type 1 diabetes?

- Does raising the head of the bed of a mechanically ventilated patient reduce the chances of pneumonia?

- Does music therapy is an effective mode of PACU pain management for patients who are slowly coming out from their anesthesia?

- For all neonates (P), should vitamin K prophylaxis (I) be given for the prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding (O)?

- For young infants (0-2 months) with suspected sepsis managed in health facilities (P), should third generation cephalosporin monotherapy (I) replace currently recommended ampicillin-gentamicin combination (C) as first line empiric treatment for preventing death and sequelae (O)?

- In low-birth-weight/pre-term neonates in health facilities (P), is skin-to-skin contact immediately after birth (I) more effective than conventional care (C) in preventing hypothermia (O)?

- In children aged 2–59 months (P), what is the most effective antibiotic therapy (I, C) for severe pneumonia (O)?

- Is skin-to-skin contact of the infant with the mother a more assured way of ensuring neonatal mortality compared to drying and wrapping?

- Are oral contraceptives effective in stopping pregnancy for women above 30 years?

- Is spironolactone a better drug for reducing the blood pressure of teenagers when compared to clonidine?

- What is the usefulness of an LP/spinal tap after the beginning of antivirals for a pediatric population suffering from fever?

- In children aged 2–59 months in developing countries (P), which parenteral antibiotic or combination of antibiotics (I), at what dose and duration, is effective for the treatment of suspected bacterial meningitis in hospital in reducing mortality and sequelae (O)?

- Does the habit of washing hands third-generation workers decrease the events of infections in hospitals?

- Is the intake of zinc pills more effective than Vitamin C for preventing cold during winter for middle-aged women?

- In children with acute severe malnutrition (P), are antibiotics (I) effective in preventing death and sequelae (O)?

- Among, children with lower respiratory tract infection (P), what are the best cut off oxygen saturation levels (D), at different altitudes that will determine hypoxaemia requiring oxygen therapy (O)?

- In infants and children in low-resource settings (P), what is the most appropriate method (D) of detecting hypoxaemia in hospitals (O)?

- In children with shock (P), what is the most appropriate choice of intravenous fluid therapy (I) to prevent death and sequelae (O)?

- In fully conscious children with hypoglycaemia (P) what is the effectiveness of administering sublingual sugar (I)?

- Is using toys as distractions during giving needle vaccinations to toddlers an effective pain response management?

- What is the result of a higher amount of potassium intake among children with low blood pressure?

- Is cup feeding an infant better than feeding through tubes in a NICU setup?

- Does the intervention of flushing the heroin via lines a more effective way of treating patients with CVLs/PICCs?

- Is the use of intravenous fluid intervention a better remedy for infants under fatal conditions?

- Do bedside shift reports help in the overall patient care for nurses?

- Is home visitation a better way of dealing with teen pregnancy when compared to regular school visits in rural areas?

- Is fentanyl more effective than morphine in dealing with the pain of adults over the age of 50 years?

- What are the health outcomes of having a high amount of potassium for adults over the age of 21 years?

- Does the use of continuous feed during emesis a more effective way of intervention when compared to the process of stopping the feed for a short period?

- Does controlling the amount of sublingual sugar help completely conscious children suffering from hypoglycemia?

- Is the lithotomy position an ideal position for giving birth to women in labor?

- Does group therapy help patients with schizophrenia to help their conversational skills?

- What are the probable after-effects, in the form of bruises and other injuries, of heparin injection therapy for COPD patients?

- Would standardized discharge medication education improve home medication adherence in adults age 65 and older compared to-standardized discharge medication education?

- In patients with psychiatric disorders is medication non-compliance a greater risk compared with adults experiencing chronic illness?

- Is the use of beta-blockers for lowering blood pressure for adult men over the age of 70 years effective?

- Nasal swab or nasal aspirate? Which one is more effective for children suffering from seasonal flu?

- What are the effects of adding beta-blockers for lowering blood pressure for adult men over the age of 70 years?

- Does the process of stopping lipids for 4 hours an effective measure of obtaining the desired TG level for patients who are about to receive TPN?

- Is medical intervention a proper way of dealing with childhood obesity among school-going children?

- Can nurse-led presentations of mental health associated with bullying help in combating such tendencies in public schools?

- What are the impacts of managing Prevacid before a pH probe study for pediatric patients with GERD?

- What are the measurable effects of extending ICU stays and antibiotic consumption amongst children with sepsis?

- Does the use of infrared skin thermometers justified when compared to the tympanic thermometers for a pediatric population?

- What are the roles of a pre-surgery cardiac nurse in order to prevent depression among patients awaiting cardiac operation?

- Does the increase in the habit of smoking marijuana among Dutch students increase the chances of depression?

- What is the direct connection between VAP and NGT?

- Is psychological intervention for people suffering from dementia a more effective measure than giving them a placebo?

- Are alarm sensors effective in preventing accidents in hospitals for patients over the age of 65 years?

- Is the sudden change of temperature harmful for patients who are neurologically devastated?

- Is it necessary to test blood glucose levels, 4 times a day, for a patient suffering from Type 1 diabetes?

- Is the use of MDI derive better results, when compared to regular nebulizers, for pediatric patients suffering from asthma?

- What are the effects of IVF bolus in controlling the amount of Magnesium Sulfate for patients who are suffering from asthma?

- Is the process of stopping lipids for 4 hours an effective measure of obtaining the desired TG level for patients who are about to receive TPN?

- What are the standards of vital signs for a pediatric population?

- Is daily blood pressure monitoring help in addressing the triggers of hypertension among males over 65 years?

- Does receiving phone tweets lower blood sugar levels for people suffering from Type 1 diabetes?

- Are males over the age of 30 years who have smoked for more than 1 year exposed to a greater risk of esophageal cancer when compared to the same age group of men who have no history of smoking?

- Does the increase in the use of mosquito nets in Uganda help in the reduction of malaria among the infants?

- Does the increase in the intake of oral contraceptives increase the chances of breast cancer among 20-30 years old women in the UK?

- In postpartum women with postnatal depression (P), does group therapy (I) compared to individual therapy (C) improve maternal-infant bonding (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In patients with chronic pain (P), does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (I) compared to pharmacotherapy (C) improve quality of life (O) after 12 weeks (T)?

- In patients with type 2 diabetes (P), does continuous glucose monitoring (I) compared to self-monitoring of blood glucose (C) improve glycemic control (O) over a period of three months (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does a vegetarian diet (I) compared to a regular diet (C) slow the decline in renal function (O) after one year (T)?

- In pediatric patients with acute otitis media (P), does delayed antibiotic prescribing (I) compared to immediate antibiotic prescribing (C) reduce antibiotic use (O) within one week (T)?

- In older adults with dementia (P), does pet therapy (I) compared to no pet therapy (C) decrease agitation (O) after three months (T)?

- In patients with chronic heart failure (P), does telemonitoring of vital signs (I) compared to standard care (C) reduce hospital readmissions (O) within six months (T)?

- In patients with anxiety disorders (P), does exposure therapy (I) compared to cognitive therapy (C) reduce anxiety symptoms (O) after 12 weeks (T)?

- In postpartum women with breastfeeding difficulties (P), does lactation consultation (I) compared to standard care (C) increase breastfeeding rates (O) after four weeks (T)?

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P), does long-acting bronchodilator therapy (I) compared to short-acting bronchodilator therapy (C) improve lung function (O) after three months (T)?

- In patients with major depressive disorder (P), does bright light therapy (I) compared to placebo (C) reduce depressive symptoms (O) after six weeks (T)?

- In patients with diabetes (P), does telemedicine-based diabetes management (I) compared to standard care (C) improve glycemic control (O) over a period of six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does a low-phosphorus diet (I) compared to a regular diet (C) decrease serum phosphate levels (O) after one year (T)?

- In pediatric patients with acute gastroenteritis (P), does probiotic supplementation (I) compared to placebo (C) reduce the duration of diarrhea (O) within 48 hours (T)?

- In patients with chronic pain (P), does acupuncture (I) compared to sham acupuncture (C) reduce pain intensity (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In older adults at risk of falls (P), does a home modification program (I) compared to no intervention (C) reduce the incidence of falls (O) over a period of six months (T)?

- In patients with schizophrenia (P), does cognitive remediation therapy (I) compared to standard therapy (C) improve cognitive function (O) after one year (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (I) compared to angiotensin receptor blockers (C) slow the progression of renal disease (O) over a period of two years (T)?

- In postoperative patients (P), does chlorhexidine bathing (I) compared to regular bathing (C) reduce the risk of surgical site infections (O) within 30 days (T)?

- In patients with type 2 diabetes (P), does a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet (I) compared to a low-fat diet (C) improve glycemic control (O) over a period of six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P), does pulmonary rehabilitation combined with telemonitoring (I) compared to standard pulmonary rehabilitation (C) improve exercise capacity (O) after three months (T)?

- In patients with heart failure (P), does a nurse-led heart failure clinic (I) compared to usual care (C) improve self-care behaviors (O) after six months (T)?

- In postpartum women with postnatal depression (P), does telephone-based counseling (I) compared to face-to-face counseling (C) reduce depressive symptoms (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In patients with chronic migraine (P), does prophylactic treatment with topiramate (I) compared to amitriptyline (C) reduce the frequency of migraines (O) after three months (T)?

- In pediatric patients with acute otitis media (P), does watchful waiting (I) compared to immediate antibiotic treatment (C) reduce the duration of symptoms (O) within seven days (T)?

- In older adults with dementia (P), does reminiscence therapy (I) compared to usual care (C) improve cognitive function (O) after three months (T)?

- In patients with chronic heart failure (P), does telemonitoring combined with a medication reminder system (I) compared to telemonitoring alone (C) reduce hospital readmissions (O) within six months (T)?

- In patients with asthma (P), does self-management education (I) compared to standard care (C) reduce asthma exacerbations (O) over a period of one year (T)?

- In postoperative patients (P), does the use of wound dressings with antimicrobial properties (I) compared to standard dressings (C) reduce the incidence of surgical site infections (O) within 30 days (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does mindfulness-based stress reduction (I) compared to usual care (C) improve psychological well-being (O) over a period of three months (T)?

- In adult patients with chronic pain (P), does biofeedback therapy (I) compared to relaxation techniques (C) reduce pain intensity (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In patients with type 2 diabetes (P), does a low-glycemic index diet (I) compared to a high-glycemic-index diet (C) improve glycemic control (O) over a period of six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P), does regular physical activity (I) compared to no physical activity (C) improve health-related quality of life (O) after three months (T)?

- In patients with major depressive disorder (P), does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (I) compared to antidepressant medication (C) reduce depressive symptoms (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In postpartum women (P), does perineal warm compresses (I) compared to standard perineal care (C) reduce perineal pain (O) after vaginal delivery (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does a low-protein, low-phosphorus diet (I) compared to a low-protein diet alone (C) slow the progression of renal disease(O) after two years (T)?

- In pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (P), does mindfulness-based interventions (I) compared to medication alone (C) improve attention and behavior (O) after six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic pain (P), does cognitive-behavioral therapy (I) compared to physical therapy (C) reduce pain interference (O) after 12 weeks (T)?

- In elderly patients with osteoarthritis (P), does aquatic exercise (I) compared to land-based exercise (C) improve joint flexibility and reduce pain (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In patients with multiple sclerosis (P), does high-intensity interval training (I) compared to moderate-intensity continuous training (C) improve physical function (O) after three months (T)?

- In postoperative patients (P), does preoperative carbohydrate loading (I) compared to fasting (C) reduce postoperative insulin resistance (O) within 24 hours (T)?

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P), does home-based tele-rehabilitation (I) compared to center-based rehabilitation (C) improve exercise capacity (O) after six months (T)?

- In patients with rheumatoid arthritis (P), does tai chi (I) compared to pharmacological treatment (C) reduce joint pain and improve physical function (O) after six months (T)?

- In postpartum women with postpartum hemorrhage (P), does early administration of tranexamic acid (I) compared to standard administration (C) reduce blood loss (O) within two hours (T)?

- In patients with hypertension (P), does mindfulness meditation (I) compared to relaxation techniques (C) reduce blood pressure (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In elderly patients with hip fractures (P), does multidisciplinary geriatric care (I) compared to standard care (C) improve functional outcomes (O) after three months (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does aerobic exercise (I) compared to resistance exercise (C) improve renal function (O) after six months (T)?

- In patients with major depressive disorder (P), does add-on treatment with omega-3 fatty acids (I) compared to placebo (C) reduce depressive symptoms (O) after 12 weeks (T)?

- In postoperative patients (P), does preoperative education using multimedia materials (I) compared to standard education (C) improve patient satisfaction (O) after surgery (T)?

- In patients with type 2 diabetes (P), does a plant-based diet (I) compared to a standard diet (C) improve glycemic control (O) after three months (T)?

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P), does high-flow oxygen therapy (I) compared to standard oxygen therapy (C) improve exercise tolerance (O) after three months (T)?

- In patients with heart failure (P), does nurse-led telephone follow-up (I) compared to standard care (C) reduce hospital readmissions (O) within six months (T)?

- In postpartum women with postnatal depression (P), does online cognitive-behavioral therapy (I) compared to face-to-face therapy (C) reduce depressive symptoms (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In patients with chronic migraine (P), does mindfulness-based stress reduction (I) compared to medication alone (C) reduce the frequency and severity of migraines (O) after three months (T)?

- In older adults with delirium (P), does structured music intervention (I) compared to standard care (C) reduce the duration of delirium episodes (O) during hospitalization (T)?

- In patients with chronic low back pain (P), does yoga (I) compared to physical therapy (C) reduce pain intensity (O) after six weeks (T)?

- In pediatric patients with acute otitis media (P), does watchful waiting with pain management (I) compared to immediate antibiotic treatment (C) reduce the need for antibiotics (O) within one week (T)?

- In patients with schizophrenia (P), does family psychoeducation (I) compared to standard treatment (C) improve medication adherence (O) over a period of six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does a low-phosphorus diet (I) compared to a regular diet (C) slow the progression of renal disease (O) after one year (T)?

- In postoperative patients (P), does wound irrigation with saline solution (I) compared to povidone-iodine solution (C) reduce the incidence of surgical site infections (O) within 30 days (T)?

- In patients with type 1 diabetes (P), does continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (I) compared to multiple daily injections (C) improve glycemic control (O) over a period of six months (T)?

- In postoperative patients (P), does the use of prophylactic antibiotics (I) compared to no antibiotics (C) reduce the incidence of surgical site infections (O) within 30 days (T)?

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P), does smoking cessation counseling (I) compared to no counseling (C) decrease the frequency of exacerbations (O) over a period of six months (T)?

- In patients with diabetes (P), does a multidisciplinary team approach (I) compared to standard care (C) improve self-management behaviors (O) over a period of one year (T)?

- In pregnant women with gestational hypertension (P), does bed rest (I) compared to regular activity (C) reduce the risk of developing preeclampsia (O) before delivery (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (I) compared to placebo (C) slow the progression of renal disease (O) over a period of two years (T)?

- In older adults with hip fractures (P), does early surgical intervention (I) compared to delayed surgery (C) improve functional outcomes (O) after six months (T)?

- In patients with major depressive disorder (P), does exercise (I) compared to antidepressant medication (C) reduce depressive symptoms (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In children with autism spectrum disorder (P), does applied behavior analysis (I) compared to standard therapy (C) improve social communication skills (O) over a period of one year (T)?

- In postoperative patients (P), does the use of incentive spirometry (I) compared to no spirometry (C) decrease the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications (O) within seven days (T)?

- In patients with hypertension (P), does a combination of diet modification and exercise (I) compared to medication alone (C) lower blood pressure (O) after six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P), does home oxygen therapy (I) compared to no oxygen therapy (C) improve exercise capacity (O) after threemonths (T)?

- In patients with heart failure (P), does a multidisciplinary heart failure management program (I) compared to standard care (C) reduce hospital readmissions (O) within six months (T)?

- In postpartum women with postnatal depression (P), does mindfulness meditation (I) compared to relaxation techniques (C) reduce depressive symptoms (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does a low-sodium diet (I) compared to a regular diet (C) lower blood pressure (O) after six months (T)?

- In pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (P), does neurofeedback training (I) compared to medication (C) improve attention and behavior (O) after six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic pain (P), does transcranial direct current stimulation (I) compared to sham stimulation (C) reduce pain intensity (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In older adults with osteoporosis (P), does a structured exercise program (I) compared to no exercise (C) improve bone mineral density (O) after six months (T)?

- In patients with type 2 diabetes (P), does a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet (I) compared to a standard diet (C) improve glycemic control (O) over a period of six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P), does mindfulness-based stress reduction (I) compared to usual care (C) improve dyspnea symptoms (O) after three months (T)?

- In postpartum women with postnatal depression (P), does online peer support (I) compared to individual therapy (C) reduce depressive symptoms (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does resistance training (I) compared to aerobic training (C) improve muscle strength (O) after six months (T)?

- In pediatric patients with asthma (P), does a written asthma action plan (I) compared to verbal instructions (C) reduce emergency department visits (O) within six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic pain (P), does yoga (I) compared to pharmacological treatment (C) reduce pain interference (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In older adults at risk of falls (P), does a multifactorial falls prevention program (I) compared to no intervention (C) reduce the rate of falls (O) over a period of six months (T)?

- In patients with schizophrenia (P), does cognitive-behavioral therapy (I) compared to medication alone (C) reduce positive symptom severity (O) after six months (T)?

- In postpartum women with breastfeeding difficulties (P), does breast massage (I) compared to no massage (C) improve milk flow (O) after four weeks (T)?

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P), does long-term oxygen therapy (I) compared to short-term oxygen therapy (C) improve survival rates (O) after one year (T)?

- In patients with major depressive disorder (P), does repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (I) compared to sham treatment (C) reduce depressive symptoms (O) after six weeks (T)?

- In patients with diabetes (P), does a digital health app (I) compared to standard care (C) improve medication adherence (O) over a period of six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (P), does a low-potassium diet (I) compared to a regular diet (C) lower serum potassium levels (O) after one year (T)?

- In pediatric patients with acute gastroenteritis (P), does oral rehydration solution (I) compared to intravenous fluid therapy (C) reduce hospital admissions (O) within 48 hours (T)?

- In patients with chronic pain (P), does hypnotherapy (I) compared to no hypnotherapy (C) reduce pain intensity (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- In older adults at risk of falls (P), does a tai chi program (I) compared to no exercise program (C) improve balance and stability (O) after six months (T)?

- In patients with chronic heart failure (P), does a home-based self-care intervention (I) compared to standard care (C) reduce hospital readmissions (O) within six months (T)?

- In patients with anxiety disorders (P), does acceptance and commitment therapy (I) compared to cognitive-behavioral therapy (C) reduce anxiety symptoms (O) after 12 weeks (T)?

- In postpartum women with breastfeeding difficulties (P), does the use of nipple shields (I) compared to no nipple shields (C) improve breastfeeding success (O) after four weeks (T)?

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P), does a comprehensive self-management program (I) compared to usual care (C) improve health-related quality of life (O) after three months (T)?

- In patients with major depressive disorder (P), does internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (I) compared to face-to-face therapy (C) reduce depressive symptoms (O) after eight weeks (T)?

- Does the increase in the habit of smoking marijuana among Dutch students increase the likelihood of depression?

- Does the use of pain relief medication during surgery provide more effective pain reduction compared to the same medication given post-surgery?

- Does the increase in the intake of oral contraceptives increase the risk of breast cancer among women aged 20-30 in the UK?

- Does the habit of washing hands among healthcare workers decrease the rate of infections in hospitals?

- Does the use of modern syringes help in reducing needle injuries among healthcare workers in America?

- Does encouraging male work colleagues to talk about sexual harassment decrease the rate of depression in the workplace?

- Does bullying in boarding schools in Scotland increase the likelihood of domestic violence within a 20-year timeframe?

- Does breastfeeding among toddlers in urban United States decrease their chances of obesity as pre-schoolers?

- Does the increase in the intake of antidepressants among urban women aged 30 years and older affect their maternal health?

- Does forming work groups to discuss domestic violence among the rural population of the United States reduce stress and depression among women?

- Does the increased use of mosquito nets in Uganda help in reducing malaria cases among infants?

- Can colon cancer be more effectively detected when colonoscopy is supported by an occult blood test compared to colonoscopy alone?

- Does regular usage of low-dose aspirin effectively reduce the risk of heart attacks and stroke for women above the age of 80 years?

- Is yoga an effective medical therapy for reducing lymphedema in patients recovering from neck cancer?

- Does daily blood pressure monitoring help in addressing the triggers of hypertension among males over 65 years?

- Does a regular 30-minute exercise regimen effectively reduce the risk of heart disease in adults over 65 years?

- Does prolonged exposure to chemotherapy increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases among teenagers suffering from cancer?

- Does breastfeeding among toddlers in the urban United States decrease their chances of obesity as pre-schoolers?

- Are first-time mothers giving birth to premature babies more prone to postpartum depression compared to second or third-time mothers in the same condition?

- For women under the age of 50 years, is a yearly mammogram more effective in preventing breast cancer compared to a mammogram done every 3 years?

- After being diagnosed with blood sugar levels, is a four-times-a-day blood glucose monitoring process more effective in controlling the onset of Type 1 diabetes?

Related: How to write an abstract poster presentation.

You can never go wrong with getting expertly written examples as a source for your inspiration. They factor in all the qualities of a good PICO question, which sets you miles ahead in your research process.

If you need a personalized approach to choosing a good PICOT question and writing a problem and purpose statement, our nursing paper acers can help you.

Nursing research specialists work with nursing students, professional nurses, and medical students to advance their academic and career goals. We offer private, reliable, confidential, and top-quality services.

Struggling with

Related Articles

How to Create an Effective Poster Presentation (A Nurse Student’s Guide)

Why you should Get a Doctorate in Nursing (DNP) Degree

Nursing Topics for Research plus Ideas

NurseMyGrades is being relied upon by thousands of students worldwide to ace their nursing studies. We offer high quality sample papers that help students in their revision as well as helping them remain abreast of what is expected of them.

Nursing Research Nursing Test Bank and Practice Questions (60 Items)

Welcome to your nursing test bank and practice questions for nursing research.

Nursing Research Test Bank

Nursing research has a great significance on the contemporary and future professional nursing practice , thus rendering it an essential component of the educational process. Research is typically not among the traditional responsibilities of an entry-level nurse . Many nurses are involved in either direct patient care or administrative aspects of health care. However, nursing research is a growing field in which individuals within the profession can contribute a variety of skills and experiences to the science of nursing care. Nursing research is critical to the nursing profession and is necessary for continuing advancements that promote optimal nursing care. Test your knowledge about nursing research in this 60-item nursing test bank .

Quiz Guidelines

Before you start, here are some examination guidelines and reminders you must read:

- Practice Exams : Engage with our Practice Exams to hone your skills in a supportive, low-pressure environment. These exams provide immediate feedback and explanations, helping you grasp core concepts, identify improvement areas, and build confidence in your knowledge and abilities.

- You’re given 2 minutes per item.

- For Challenge Exams, click on the “Start Quiz” button to start the quiz.

- Complete the quiz : Ensure that you answer the entire quiz. Only after you’ve answered every item will the score and rationales be shown.

- Learn from the rationales : After each quiz, click on the “View Questions” button to understand the explanation for each answer.

- Free access : Guess what? Our test banks are 100% FREE. Skip the hassle – no sign-ups or registrations here. A sincere promise from Nurseslabs: we have not and won’t ever request your credit card details or personal info for our practice questions. We’re dedicated to keeping this service accessible and cost-free, especially for our amazing students and nurses. So, take the leap and elevate your career hassle-free!

- Share your thoughts : We’d love your feedback, scores, and questions! Please share them in the comments below.

Quizzes included in this guide are:

Recommended Resources

Recommended books and resources for your NCLEX success:

Disclosure: Included below are affiliate links from Amazon at no additional cost from you. We may earn a small commission from your purchase. For more information, check out our privacy policy .

Saunders Comprehensive Review for the NCLEX-RN Saunders Comprehensive Review for the NCLEX-RN Examination is often referred to as the best nursing exam review book ever. More than 5,700 practice questions are available in the text. Detailed test-taking strategies are provided for each question, with hints for analyzing and uncovering the correct answer option.

Strategies for Student Success on the Next Generation NCLEX® (NGN) Test Items Next Generation NCLEX®-style practice questions of all types are illustrated through stand-alone case studies and unfolding case studies. NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM) is included throughout with case scenarios that integrate the six clinical judgment cognitive skills.

Saunders Q & A Review for the NCLEX-RN® Examination This edition contains over 6,000 practice questions with each question containing a test-taking strategy and justifications for correct and incorrect answers to enhance review. Questions are organized according to the most recent NCLEX-RN test blueprint Client Needs and Integrated Processes. Questions are written at higher cognitive levels (applying, analyzing, synthesizing, evaluating, and creating) than those on the test itself.

NCLEX-RN Prep Plus by Kaplan The NCLEX-RN Prep Plus from Kaplan employs expert critical thinking techniques and targeted sample questions. This edition identifies seven types of NGN questions and explains in detail how to approach and answer each type. In addition, it provides 10 critical thinking pathways for analyzing exam questions.

Illustrated Study Guide for the NCLEX-RN® Exam The 10th edition of the Illustrated Study Guide for the NCLEX-RN Exam, 10th Edition. This study guide gives you a robust, visual, less-intimidating way to remember key facts. 2,500 review questions are now included on the Evolve companion website. 25 additional illustrations and mnemonics make the book more appealing than ever.

NCLEX RN Examination Prep Flashcards (2023 Edition) NCLEX RN Exam Review FlashCards Study Guide with Practice Test Questions [Full-Color Cards] from Test Prep Books. These flashcards are ready for use, allowing you to begin studying immediately. Each flash card is color-coded for easy subject identification.

Recommended Links

If you need more information or practice quizzes, please do visit the following links:

An investment in knowledge pays the best interest. Keep up the pace and continue learning with these practice quizzes:

- Nursing Test Bank: Free Practice Questions UPDATED ! Our most comprehenisve and updated nursing test bank that includes over 3,500 practice questions covering a wide range of nursing topics that are absolutely free!

- NCLEX Questions Nursing Test Bank and Review UPDATED! Over 1,000+ comprehensive NCLEX practice questions covering different nursing topics. We’ve made a significant effort to provide you with the most challenging questions along with insightful rationales for each question to reinforce learning.

4 thoughts on “Nursing Research Nursing Test Bank and Practice Questions (60 Items)”

Thanks for the well prepared questions and answers. It will be of a great help for those who look up your contributions.

Hi Zac, we’re having some performance issues with the quizzes so we’re forced to change their settings in the meantime. We are working on a solution and will revert the changes once we’re sure that the problem is resolved. Thanks for the understanding!

I need pass question and answer on nursing research

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- Bureaus and Offices

- Contact HRSA

- Data & Research

- Data Tools and Dashboards

National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (NSSRN)

New findings on the state of the nursing workforce.

In March 2024, HRSA released new data, survey results, and workforce projections on the U.S. nursing workforce.

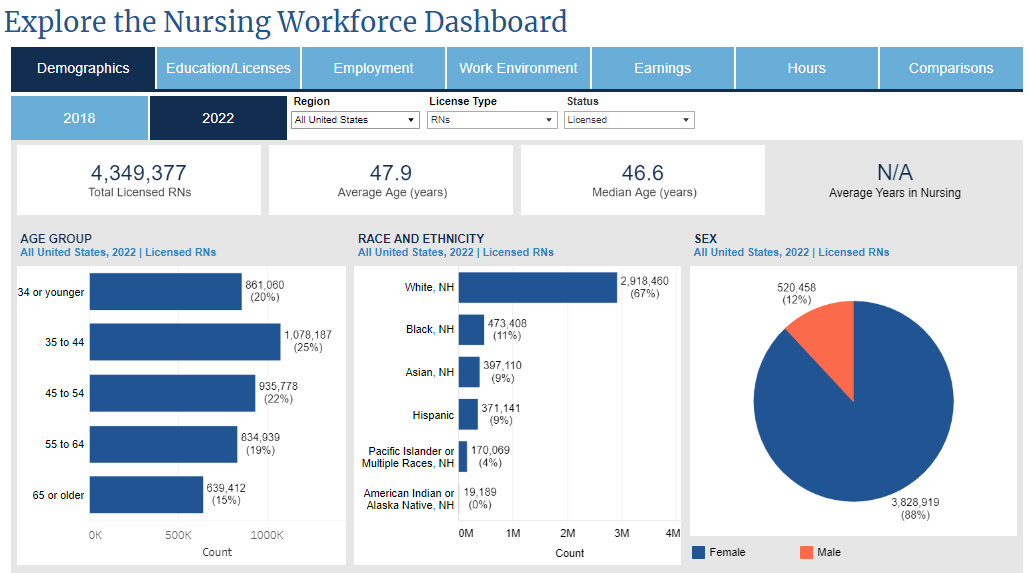

Key findings of the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (NSSRN) show that the nursing workforce is becoming more diverse, more highly educated, but less satisfied with their job. The survey data also show the effects of COVID on the profession, while workforce projections show shortages increasing in nursing occupations through 2036.

Read the factsheet (PDF - 83 KB) for more information.

In 2022–2023, the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, in collaboration with the U.S. Census Bureau, surveyed registered nurses in the United States. Nearly 50,000 registered nurses provided data. We compiled the results, produced several reports on the data, and updated an easy-to-use dashboard to display the latest information.

From its inaugural assessment in 1977, the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (NSSRN) represents the longest running survey of registered nurses (RNs) in the United States. The survey examines the characteristics of registered nurses and their experiences in nursing.

How can I review findings on the nursing workforce?

We provide summary reports as well as a dashboard to present our findings on the nursing workforce, based on data from the 2022 NSSRN.

Nursing reports and briefs

- Nursing Education and Training: Data from the 2022 NSSRN (PDF - 425 KB)

- Experiences of Nurses Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Data from the 2022 NSSRN (PDF - 288 KB)

- Job Satisfaction Among Registered Nurses: Data from the 2022 NSSRN (PDF - 389 KB)

Nursing Workforce Dashboard

The Nursing Workforce Dashboard visualizes data from both the 2022 and 2018 NSSRN, which includes detailed information on the nursing workforce in the United States. This dashboard provides insights on the nursing profession by showing their work environment, education, demographics, hours, earnings, and more. It also helps us predict what nurses will need in the future.

The dashboard enables you to access the 400,000 unique data points from the survey and visualize this data on the nursing workforce landscape, including demographics, employment, education, earnings, and hours for various categories of nurses (RNs, NPs, and APRNs).

The dashboard serves as a benchmark for providing educators, health workforce leaders, and policymakers with key details and developments of the nursing workforce supply.

Because these data were based on the nursing workforce in December 2021, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is now reflected in the dashboard.

Training videos on the Nursing Dashboard

We developed these videos in Zoom to demonstrate how to use the features of the dashboard.

Part 1: Introduction, the Demographics Tab, the Education/Licenses Tab (21:34 min) Part 2: The Employment and Work Environment Tabs (8:32 min) Part 3: The Earnings and Hours Tabs (8:16 min)

Where can I find more data from the NSSRN?

Visit the Data Warehouse for Nursing Workforce Survey Data . Find data on registered nurses from 1977-2022 and nurse practitioners from our 2012 survey.

You can also download the survey questionnaire, 2022 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (PDF - 1 MB) .

Where can I find information on the 2018 NSSRN?

We maintain the following information on the 2018 survey and findings from the data.

- Brief Summary of Results: 2018 NSSRN (PDF - 848 KB)

- Technical Documentation for the 2018 NSSRN (PDF - 7 MB) *

- Nursing Education and Training in the United States (PDF - 524 KB)

- Brief: Job Satisfaction Among Registered Nurses – Pre-COVID

- 2018 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (PDF - 906 KB) *

Who do I contact with questions?

Email us at [email protected] .

* If you use assistive technology, you may not be able to access information in this file. For help, call 1-800-221-9393 (TTY: 877-897-9910), 8 a.m.-8 p.m. ET weekdays (except federal holidays).

- Dean's Message

- Mission Statement

- Diversity At VUSN

- Our History

- Faculty Fellows & Honors

- Accreditation

- Privacy Policy

- Academic Programs

- Master of Science in Nursing

- Master of Nursing

- Doctor of Nursing Practice

- PhD in Nursing Science

- Post-Master's Certificate

- Postdoctoral Program

- Special (Non-Degree) Students

- Admissions Information

- Admissions Requirements

- MSN Admissions

- MN Admissions

- DNP Admissions

- PhD Admissions

- Post-Master's Certificates

- Postdoctoral Admissions

- Center for Research Development and Scholarship (CRDS)

- Signature Areas

- CRDS Behavorial Labs

- Research Resources

- Faculty Scholarship Program

- Research Faculty

- Preparing For Practice

- Faculty Practice Network

- Credentialing Process

- Faculty Practice History

- Vanderbilt Nurse-Midwifery Faculty Practice

- What is Advanced Practice Nursing?

- Preceptor Resources

- The Vanderbilt Advantage

- Making A Difference

- Informatics

- Global Health

- Organizations

- Veterans/Military

Examples of Research Questions

Phd in nursing science program, examples of broad clinical research questions include:.

- Does the administration of pain medication at time of surgical incision reduce the need for pain medication twenty-four hours after surgery?

- What maternal factors are associated with obesity in toddlers?

- What elements of a peer support intervention prevent suicide in high school females?

- What is the most accurate and comprehensive way to determine men’s experience of physical assault?

- Is yoga as effective as traditional physical therapy in reducing lymphedema in patients who have had head and neck cancer treatment?

- In the third stage of labor, what is the effect of cord cutting within the first three minutes on placenta separation?

- Do teenagers with Type 1 diabetes who receive phone tweet reminders maintain lower blood sugars than those who do not?

- Do the elderly diagnosed with dementia experience pain?

- How can siblings’ risk of depression be predicted after the death of a child?

- How can cachexia be prevented in cancer patients receiving aggressive protocols involving radiation and chemotherapy?

Examples of some general health services research questions are:

- Does the organization of renal transplant nurse coordinators’ responsibilities influence live donor rates?

- What activities of nurse managers are associated with nurse turnover? 30 day readmission rates?

- What effect does the Nurse Faculty Loan program have on the nurse researcher workforce? What effect would a 20% decrease in funds have?

- How do psychiatric hospital unit designs influence the incidence of patients’ aggression?

- What are Native American patient preferences regarding the timing, location and costs for weight management counseling and how will meeting these preferences influence participation?

- What predicts registered nurse retention in the US Army?

- How, if at all, are the timing and location of suicide prevention appointments linked to veterans‘ suicide rates?

- What predicts the sustainability of quality improvement programs in operating rooms?

- Do integrated computerized nursing records across points of care improve patient outcomes?

- How many nurse practitioners will the US need in 2020?

PhD Resources

- REQUEST INFO

- CAREER SERVICES

- PRIVACY POLICY

- VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY

- VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER

DISTINCTIONS

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Lippincott Open Access

Questionnaire Development of a Good Nurse and Better Nursing From Korean Nurses' Perspective

Mihyun park.

1 PhD, RN, Associate Professor, College of Nursing, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, ROK

Eun-Jun PARK

2 PhD, RN, Professor, Department of Nursing, Konkuk University, ROK.

The concepts of “good nurse” and “better nursing” have changed over time and should be investigated from the perspective of nurses.

The aim of this study was to develop and assess the psychometric properties of two questionnaires used to assess “good nurse” and “better nursing.”

The interview data of 30 registered nurses (RNs) from a previous study were reviewed to develop the questionnaire items, and content validity was examined. One hundred seventeen RNs participated in a pilot survey for pretesting the constructs, 469 RNs participated in a main survey to explore these constructs using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and 468 RNs participated in model refining and validation using confirmatory factor analysis.