Enterprise Risk Management Case Studies: Heroes and Zeros

By Andy Marker | April 7, 2021

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Link copied

We’ve compiled more than 20 case studies of enterprise risk management programs that illustrate how companies can prevent significant losses yet take risks with more confidence.

Included on this page, you’ll find case studies and examples by industry , case studies of major risk scenarios (and company responses), and examples of ERM successes and failures .

Enterprise Risk Management Examples and Case Studies

With enterprise risk management (ERM) , companies assess potential risks that could derail strategic objectives and implement measures to minimize or avoid those risks. You can analyze examples (or case studies) of enterprise risk management to better understand the concept and how to properly execute it.

The collection of examples and case studies on this page illustrates common risk management scenarios by industry, principle, and degree of success. For a basic overview of enterprise risk management, including major types of risks, how to develop policies, and how to identify key risk indicators (KRIs), read “ Enterprise Risk Management 101: Programs, Frameworks, and Advice from Experts .”

Enterprise Risk Management Framework Examples

An enterprise risk management framework is a system by which you assess and mitigate potential risks. The framework varies by industry, but most include roles and responsibilities, a methodology for risk identification, a risk appetite statement, risk prioritization, mitigation strategies, and monitoring and reporting.

To learn more about enterprise risk management and find examples of different frameworks, read our “ Ultimate Guide to Enterprise Risk Management .”

Enterprise Risk Management Examples and Case Studies by Industry

Though every firm faces unique risks, those in the same industry often share similar risks. By understanding industry-wide common risks, you can create and implement response plans that offer your firm a competitive advantage.

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Banking

Toronto-headquartered TD Bank organizes its risk management around two pillars: a risk management framework and risk appetite statement. The enterprise risk framework defines the risks the bank faces and lays out risk management practices to identify, assess, and control risk. The risk appetite statement outlines the bank’s willingness to take on risk to achieve its growth objectives. Both pillars are overseen by the risk committee of the company’s board of directors.

Risk management frameworks were an important part of the International Organization for Standardization’s 31000 standard when it was first written in 2009 and have been updated since then. The standards provide universal guidelines for risk management programs.

Risk management frameworks also resulted from the efforts of the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). The group was formed to fight corporate fraud and included risk management as a dimension.

Once TD completes the ERM framework, the bank moves onto the risk appetite statement.

The bank, which built a large U.S. presence through major acquisitions, determined that it will only take on risks that meet the following three criteria:

- The risk fits the company’s strategy, and TD can understand and manage those risks.

- The risk does not render the bank vulnerable to significant loss from a single risk.

- The risk does not expose the company to potential harm to its brand and reputation.

Some of the major risks the bank faces include strategic risk, credit risk, market risk, liquidity risk, operational risk, insurance risk, capital adequacy risk, regulator risk, and reputation risk. Managers detail these categories in a risk inventory.

The risk framework and appetite statement, which are tracked on a dashboard against metrics such as capital adequacy and credit risk, are reviewed annually.

TD uses a three lines of defense (3LOD) strategy, an approach widely favored by ERM experts, to guard against risk. The three lines are as follows:

- A business unit and corporate policies that create controls, as well as manage and monitor risk

- Standards and governance that provide oversight and review of risks and compliance with the risk appetite and framework

- Internal audits that provide independent checks and verification that risk-management procedures are effective

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Pharmaceuticals

Drug companies’ risks include threats around product quality and safety, regulatory action, and consumer trust. To avoid these risks, ERM experts emphasize the importance of making sure that strategic goals do not conflict.

For Britain’s GlaxoSmithKline, such a conflict led to a breakdown in risk management, among other issues. In the early 2000s, the company was striving to increase sales and profitability while also ensuring safe and effective medicines. One risk the company faced was a failure to meet current good manufacturing practices (CGMP) at its plant in Cidra, Puerto Rico.

CGMP includes implementing oversight and controls of manufacturing, as well as managing the risk and confirming the safety of raw materials and finished drug products. Noncompliance with CGMP can result in escalating consequences, ranging from warnings to recalls to criminal prosecution.

GSK’s unit pleaded guilty and paid $750 million in 2010 to resolve U.S. charges related to drugs made at the Cidra plant, which the company later closed. A fired GSK quality manager alerted regulators and filed a whistleblower lawsuit in 2004. In announcing the consent decree, the U.S. Department of Justice said the plant had a history of bacterial contamination and multiple drugs created there in the early 2000s violated safety standards.

According to the whistleblower, GSK’s ERM process failed in several respects to act on signs of non-compliance with CGMP. The company received warning letters from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2001 about the plant’s practices, but did not resolve the issues.

Additionally, the company didn’t act on the quality manager’s compliance report, which advised GSK to close the plant for two weeks to fix the problems and notify the FDA. According to court filings, plant staff merely skimmed rejected products and sold them on the black market. They also scraped by hand the inside of an antibiotic tank to get more product and, in so doing, introduced bacteria into the product.

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Consumer Packaged Goods

Mars Inc., an international candy and food company, developed an ERM process. The company piloted and deployed the initiative through workshops with geographic, product, and functional teams from 2003 to 2012.

Driven by a desire to frame risk as an opportunity and to work within the company’s decentralized structure, Mars created a process that asked participants to identify potential risks and vote on which had the highest probability. The teams listed risk mitigation steps, then ranked and color-coded them according to probability of success.

Larry Warner, a Mars risk officer at the time, illustrated this process in a case study . An initiative to increase direct-to-consumer shipments by 12 percent was colored green, indicating a 75 percent or greater probability of achievement. The initiative to bring a new plant online by the end of Q3 was coded red, meaning less than a 50 percent probability of success.

The company’s results were hurt by a surprise at an operating unit that resulted from a so-coded red risk identified in a unit workshop. Executives had agreed that some red risk profile was to be expected, but they decided that when a unit encountered a red issue, it must be communicated upward when first identified. This became a rule.

This process led to the creation of an ERM dashboard that listed initiatives in priority order, with the profile of each risk faced in the quarter, the risk profile trend, and a comment column for a year-end view.

According to Warner, the key factors of success for ERM at Mars are as follows:

- The initiative focused on achieving operational and strategic objectives rather than compliance, which refers to adhering to established rules and regulations.

- The program evolved, often based on requests from business units, and incorporated continuous improvement.

- The ERM team did not overpromise. It set realistic objectives.

- The ERM team periodically surveyed business units, management teams, and board advisers.

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Retail

Walmart is the world’s biggest retailer. As such, the company understands that its risk makeup is complex, given the geographic spread of its operations and its large number of stores, vast supply chain, and high profile as an employer and buyer of goods.

In the 1990s, the company sought a simplified strategy for assessing risk and created an enterprise risk management plan with five steps founded on these four questions:

- What are the risks?

- What are we going to do about them?

- How will we know if we are raising or decreasing risk?

- How will we show shareholder value?

The process follows these five steps:

- Risk Identification: Senior Walmart leaders meet in workshops to identify risks, which are then plotted on a graph of probability vs. impact. Doing so helps to prioritize the biggest risks. The executives then look at seven risk categories (both internal and external): legal/regulatory, political, business environment, strategic, operational, financial, and integrity. Many ERM pros use risk registers to evaluate and determine the priority of risks. You can download templates that help correlate risk probability and potential impact in “ Free Risk Register Templates .”

- Risk Mitigation: Teams that include operational staff in the relevant area meet. They use existing inventory procedures to address the risks and determine if the procedures are effective.

- Action Planning: A project team identifies and implements next steps over the several months to follow.

- Performance Metrics: The group develops metrics to measure the impact of the changes. They also look at trends of actual performance compared to goal over time.

- Return on Investment and Shareholder Value: In this step, the group assesses the changes’ impact on sales and expenses to determine if the moves improved shareholder value and ROI.

To develop your own risk management planning, you can download a customizable template in “ Risk Management Plan Templates .”

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Agriculture

United Grain Growers (UGG), a Canadian grain distributor that now is part of Glencore Ltd., was hailed as an ERM innovator and became the subject of business school case studies for its enterprise risk management program. This initiative addressed the risks associated with weather for its business. Crop volume drove UGG’s revenue and profits.

In the late 1990s, UGG identified its major unaddressed risks. Using almost a century of data, risk analysts found that extreme weather events occurred 10 times as frequently as previously believed. The company worked with its insurance broker and the Swiss Re Group on a solution that added grain-volume risk (resulting from weather fluctuations) to its other insured risks, such as property and liability, in an integrated program.

The result was insurance that protected grain-handling earnings, which comprised half of UGG’s gross profits. The greater financial stability significantly enhanced the firm’s ability to achieve its strategic objectives.

Since then, the number and types of instruments to manage weather-related risks has multiplied rapidly. For example, over-the-counter derivatives, such as futures and options, began trading in 1997. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange now offers weather futures contracts on 12 U.S. and international cities.

Weather derivatives are linked to climate factors such as rainfall or temperature, and they hedge different kinds of risks than do insurance. These risks are much more common (e.g., a cooler-than-normal summer) than the earthquakes and floods that insurance typically covers. And the holders of derivatives do not have to incur any damage to collect on them.

These weather-linked instruments have found a wider audience than anticipated, including retailers that worry about freak storms decimating Christmas sales, amusement park operators fearing rainy summers will keep crowds away, and energy companies needing to hedge demand for heating and cooling.

This area of ERM continues to evolve because weather and crop insurance are not enough to address all the risks that agriculture faces. Arbol, Inc. estimates that more than $1 trillion of agricultural risk is uninsured. As such, it is launching a blockchain-based platform that offers contracts (customized by location and risk parameters) with payouts based on weather data. These contracts can cover risks associated with niche crops and small growing areas.

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Insurance

Switzerland’s Zurich Insurance Group understands that risk is inherent for insurers and seeks to practice disciplined risk-taking, within a predetermined risk tolerance.

The global insurer’s enterprise risk management framework aims to protect capital, liquidity, earnings, and reputation. Governance serves as the basis for risk management, and the framework lays out responsibilities for taking, managing, monitoring, and reporting risks.

The company uses a proprietary process called Total Risk Profiling (TRP) to monitor internal and external risks to its strategy and financial plan. TRP assesses risk on the basis of severity and probability, and helps define and implement mitigating moves.

Zurich’s risk appetite sets parameters for its tolerance within the goal of maintaining enough capital to achieve an AA rating from rating agencies. For this, the company uses its own Zurich economic capital model, referred to as Z-ECM. The model quantifies risk tolerance with a metric that assesses risk profile vs. risk tolerance.

To maintain the AA rating, the company aims to hold capital between 100 and 120 percent of capital at risk. Above 140 percent is considered overcapitalized (therefore at risk of throttling growth), and under 90 percent is below risk tolerance (meaning the risk is too high). On either side of 100 to 120 percent (90 to 100 percent and 120 to 140 percent), the insurer considers taking mitigating action.

Zurich’s assessment of risk and the nature of those risks play a major role in determining how much capital regulators require the business to hold. A popular tool to assess risk is the risk matrix, and you can find a variety of templates in “ Free, Customizable Risk Matrix Templates .”

In 2020, Zurich found that its biggest exposures were market risk, such as falling asset valuations and interest-rate risk; insurance risk, such as big payouts for covered customer losses, which it hedges through diversification and reinsurance; credit risk in assets it holds and receivables; and operational risks, such as internal process failures and external fraud.

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Technology

Financial software maker Intuit has strengthened its enterprise risk management through evolution, according to a case study by former Chief Risk Officer Janet Nasburg.

The program is founded on the following five core principles:

- Use a common risk framework across the enterprise.

- Assess risks on an ongoing basis.

- Focus on the most important risks.

- Clearly define accountability for risk management.

- Commit to continuous improvement of performance measurement and monitoring.

ERM programs grow according to a maturity model, and as capability rises, the shareholder value from risk management becomes more visible and important.

The maturity phases include the following:

- Ad hoc risk management addresses a specific problem when it arises.

- Targeted or initial risk management approaches risks with multiple understandings of what constitutes risk and management occurs in silos.

- Integrated or repeatable risk management puts in place an organization-wide framework for risk assessment and response.

- Intelligent or managed risk management coordinates risk management across the business, using common tools.

- Risk leadership incorporates risk management into strategic decision-making.

Intuit emphasizes using key risk indicators (KRIs) to understand risks, along with key performance indicators (KPIs) to gauge the effectiveness of risk management.

Early in its ERM journey, Intuit measured performance on risk management process participation and risk assessment impact. For participation, the targeted rate was 80 percent of executive management and business-line leaders. This helped benchmark risk awareness and current risk management, at a time when ERM at the company was not mature.

Conduct an annual risk assessment at corporate and business-line levels to plot risks, so the most likely and most impactful risks are graphed in the upper-right quadrant. Doing so focuses attention on these risks and helps business leaders understand the risk’s impact on performance toward strategic objectives.

In the company’s second phase of ERM, Intuit turned its attention to building risk management capacity and sought to ensure that risk management activities addressed the most important risks. The company evaluated performance using color-coded status symbols (red, yellow, green) to indicate risk trend and progress on risk mitigation measures.

In its third phase, Intuit moved to actively monitoring the most important risks and ensuring that leaders modified their strategies to manage risks and take advantage of opportunities. An executive dashboard uses KRIs, KPIs, an overall risk rating, and red-yellow-green coding. The board of directors regularly reviews this dashboard.

Over this evolution, the company has moved from narrow, tactical risk management to holistic, strategic, and long-term ERM.

Enterprise Risk Management Case Studies by Principle

ERM veterans agree that in addition to KPIs and KRIs, other principles are equally important to follow. Below, you’ll find examples of enterprise risk management programs by principles.

ERM Principle #1: Make Sure Your Program Aligns with Your Values

Raytheon Case Study U.S. defense contractor Raytheon states that its highest priority is delivering on its commitment to provide ethical business practices and abide by anti-corruption laws.

Raytheon backs up this statement through its ERM program. Among other measures, the company performs an annual risk assessment for each function, including the anti-corruption group under the Chief Ethics and Compliance Officer. In addition, Raytheon asks 70 of its sites to perform an anti-corruption self-assessment each year to identify gaps and risks. From there, a compliance team tracks improvement actions.

Every quarter, the company surveys 600 staff members who may face higher anti-corruption risks, such as the potential for bribes. The survey asks them to report any potential issues in the past quarter.

Also on a quarterly basis, the finance and internal controls teams review higher-risk profile payments, such as donations and gratuities to confirm accuracy and compliance. Oversight and compliance teams add other checks, and they update a risk-based audit plan continuously.

ERM Principle #2: Embrace Diversity to Reduce Risk

State Street Global Advisors Case Study In 2016, the asset management firm State Street Global Advisors introduced measures to increase gender diversity in its leadership as a way of reducing portfolio risk, among other goals.

The company relied on research that showed that companies with more women senior managers had a better return on equity, reduced volatility, and fewer governance problems such as corruption and fraud.

Among the initiatives was a campaign to influence companies where State Street had invested, in order to increase female membership on their boards. State Street also developed an investment product that tracks the performance of companies with the highest level of senior female leadership relative to peers in their sector.

In 2020, the company announced some of the results of its effort. Among the 1,384 companies targeted by the firm, 681 added at least one female director.

ERM Principle #3: Do Not Overlook Resource Risks

Infosys Case Study India-based technology consulting company Infosys, which employees more than 240,000 people, has long recognized the risk of water shortages to its operations.

India’s rapidly growing population and development has increased the risk of water scarcity. A 2020 report by the World Wide Fund for Nature said 30 cities in India faced the risk of severe water scarcity over the next three decades.

Infosys has dozens of facilities in India and considers water to be a significant short-term risk. At its campuses, the company uses the water for cooking, drinking, cleaning, restrooms, landscaping, and cooling. Water shortages could halt Infosys operations and prevent it from completing customer projects and reaching its performance objectives.

In an enterprise risk assessment example, Infosys’ ERM team conducts corporate water-risk assessments while sustainability teams produce detailed water-risk assessments for individual locations, according to a report by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development .

The company uses the COSO ERM framework to respond to the risks and decide whether to accept, avoid, reduce, or share these risks. The company uses root-cause analysis (which focuses on identifying underlying causes rather than symptoms) and the site assessments to plan steps to reduce risks.

Infosys has implemented various water conservation measures, such as water-efficient fixtures and water recycling, rainwater collection and use, recharging aquifers, underground reservoirs to hold five days of water supply at locations, and smart-meter usage monitoring. Infosys’ ERM team tracks metrics for per-capita water consumption, along with rainfall data, availability and cost of water by tanker trucks, and water usage from external suppliers.

In the 2020 fiscal year, the company reported a nearly 64 percent drop in per-capita water consumption by its workforce from the 2008 fiscal year.

The business advantages of this risk management include an ability to open locations where water shortages may preclude competitors, and being able to maintain operations during water scarcity, protecting profitability.

ERM Principle #4: Fight Silos for Stronger Enterprise Risk Management

U.S. Government Case Study The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, revealed that the U.S. government’s then-current approach to managing intelligence was not adequate to address the threats — and, by extension, so was the government’s risk management procedure. Since the Cold War, sensitive information had been managed on a “need to know” basis that resulted in data silos.

In the case of 9/11, this meant that different parts of the government knew some relevant intelligence that could have helped prevent the attacks. But no one had the opportunity to put the information together and see the whole picture. A congressional commission determined there were 10 lost operational opportunities to derail the plot. Silos existed between law enforcement and intelligence, as well as between and within agencies.

After the attacks, the government moved toward greater information sharing and collaboration. Based on a task force’s recommendations, data moved from a centralized network to a distributed model, and social networking tools now allow colleagues throughout the government to connect. Staff began working across agency lines more often.

Enterprise Risk Management Examples by Scenario

While some scenarios are too unlikely to receive high-priority status, low-probability risks are still worth running through the ERM process. Robust risk management creates a culture and response capacity that better positions a company to deal with a crisis.

In the following enterprise risk examples, you will find scenarios and details of how organizations manage the risks they face.

Scenario: ERM and the Global Pandemic While most businesses do not have the resources to do in-depth ERM planning for the rare occurrence of a global pandemic, companies with a risk-aware culture will be at an advantage if a pandemic does hit.

These businesses already have processes in place to escalate trouble signs for immediate attention and an ERM team or leader monitoring the threat environment. A strong ERM function gives clear and effective guidance that helps the company respond.

A report by Vodafone found that companies identified as “future ready” fared better in the COVID-19 pandemic. The attributes of future-ready businesses have a lot in common with those of companies that excel at ERM. These include viewing change as an opportunity; having detailed business strategies that are documented, funded, and measured; working to understand the forces that shape their environments; having roadmaps in place for technological transformation; and being able to react more quickly than competitors.

Only about 20 percent of companies in the Vodafone study met the definition of “future ready.” But 54 percent of these firms had a fully developed and tested business continuity plan, compared to 30 percent of all businesses. And 82 percent felt their continuity plans worked well during the COVID-19 crisis. Nearly 50 percent of all businesses reported decreased profits, while 30 percent of future-ready organizations saw profits rise.

Scenario: ERM and the Economic Crisis The 2008 economic crisis in the United States resulted from the domino effect of rising interest rates, a collapse in housing prices, and a dramatic increase in foreclosures among mortgage borrowers with poor creditworthiness. This led to bank failures, a credit crunch, and layoffs, and the U.S. government had to rescue banks and other financial institutions to stabilize the financial system.

Some commentators said these events revealed the shortcomings of ERM because it did not prevent the banks’ mistakes or collapse. But Sim Segal, an ERM consultant and director of Columbia University’s ERM master’s degree program, analyzed how banks performed on 10 key ERM criteria.

Segal says a risk-management program that incorporates all 10 criteria has these characteristics:

- Risk management has an enterprise-wide scope.

- The program includes all risk categories: financial, operational, and strategic.

- The focus is on the most important risks, not all possible risks.

- Risk management is integrated across risk types.

- Aggregated metrics show risk exposure and appetite across the enterprise.

- Risk management incorporates decision-making, not just reporting.

- The effort balances risk and return management.

- There is a process for disclosure of risk.

- The program measures risk in terms of potential impact on company value.

- The focus of risk management is on the primary stakeholder, such as shareholders, rather than regulators or rating agencies.

In his book Corporate Value of Enterprise Risk Management , Segal concluded that most banks did not actually use ERM practices, which contributed to the financial crisis. He scored banks as failing on nine of the 10 criteria, only giving them a passing grade for focusing on the most important risks.

Scenario: ERM and Technology Risk The story of retailer Target’s failed expansion to Canada, where it shut down 133 loss-making stores in 2015, has been well documented. But one dimension that analysts have sometimes overlooked was Target’s handling of technology risk.

A case study by Canadian Business magazine traced some of the biggest issues to software and data-quality problems that dramatically undermined the Canadian launch.

As with other forms of ERM, technology risk management requires companies to ask what could go wrong, what the consequences would be, how they might prevent the risks, and how they should deal with the consequences.

But with its technology plan for Canada, Target did not heed risk warning signs.

In the United States, Target had custom systems for ordering products from vendors, processing items at warehouses, and distributing merchandise to stores quickly. But that software would need customization to work with the Canadian dollar, metric system, and French-language characters.

Target decided to go with new ERP software on an aggressive two-year timeline. As Target began ordering products for the Canadian stores in 2012, problems arose. Some items did not fit into shipping containers or on store shelves, and information needed for customs agents to clear imported items was not correct in Target's system.

Target found that its supply chain software data was full of errors. Product dimensions were in inches, not centimeters; height and width measurements were mixed up. An internal investigation showed that only about 30 percent of the data was accurate.

In an attempt to fix these errors, Target merchandisers spent a week double-checking with vendors up to 80 data points for each of the retailer’s 75,000 products. They discovered that the dummy data entered into the software during setup had not been altered. To make any corrections, employees had to send the new information to an office in India where staff would enter it into the system.

As the launch approached, the technology errors left the company vulnerable to stockouts, few people understood how the system worked, and the point-of-sale checkout system did not function correctly. Soon after stores opened in 2013, consumers began complaining about empty shelves. Meanwhile, Target Canada distribution centers overflowed due to excess ordering based on poor data fed into forecasting software.

The rushed launch compounded problems because it did not allow the company enough time to find solutions or alternative technology. While the retailer fixed some issues by the end of 2014, it was too late. Target Canada filed for bankruptcy protection in early 2015.

Scenario: ERM and Cybersecurity System hacks and data theft are major worries for companies. But as a relatively new field, cyber-risk management faces unique hurdles.

For example, risk managers and information security officers have difficulty quantifying the likelihood and business impact of a cybersecurity attack. The rise of cloud-based software exposes companies to third-party risks that make these projections even more difficult to calculate.

As the field evolves, risk managers say it’s important for IT security officers to look beyond technical issues, such as the need to patch a vulnerability, and instead look more broadly at business impacts to make a cost benefit analysis of risk mitigation. Frameworks such as the Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations by the National Institute of Standards and Technology can help.

Health insurer Aetna considers cybersecurity threats as a part of operational risk within its ERM framework and calculates a daily risk score, adjusted with changes in the cyberthreat landscape.

Aetna studies threats from external actors by working through information sharing and analysis centers for the financial services and health industries. Aetna staff reverse-engineers malware to determine controls. The company says this type of activity helps ensure the resiliency of its business processes and greatly improves its ability to help protect member information.

For internal threats, Aetna uses models that compare current user behavior to past behavior and identify anomalies. (The company says it was the first organization to do this at scale across the enterprise.) Aetna gives staff permissions to networks and data based on what they need to perform their job. This segmentation restricts access to raw data and strengthens governance.

Another risk initiative scans outgoing employee emails for code patterns, such as credit card or Social Security numbers. The system flags the email, and a security officer assesses it before the email is released.

Examples of Poor Enterprise Risk Management

Case studies of failed enterprise risk management often highlight mistakes that managers could and should have spotted — and corrected — before a full-blown crisis erupted. The focus of these examples is often on determining why that did not happen.

ERM Case Study: General Motors

In 2014, General Motors recalled the first of what would become 29 million cars due to faulty ignition switches and paid compensation for 124 related deaths. GM knew of the problem for at least 10 years but did not act, the automaker later acknowledged. The company entered a deferred prosecution agreement and paid a $900 million penalty.

Pointing to the length of time the company failed to disclose the safety problem, ERM specialists say it shows the problem did not reside with a single department. “Rather, it reflects a failure to properly manage risk,” wrote Steve Minsky, a writer on ERM and CEO of an ERM software company, in Risk Management magazine.

“ERM is designed to keep all parties across the organization, from the front lines to the board to regulators, apprised of these kinds of problems as they become evident. Unfortunately, GM failed to implement such a program, ultimately leading to a tragic and costly scandal,” Minsky said.

Also in the auto sector, an enterprise risk management case study of Toyota looked at its problems with unintended acceleration of vehicles from 2002 to 2009. Several studies, including a case study by Carnegie Mellon University Professor Phil Koopman , blamed poor software design and company culture. A whistleblower later revealed a coverup by Toyota. The company paid more than $2.5 billion in fines and settlements.

ERM Case Study: Lululemon

In 2013, following customer complaints that its black yoga pants were too sheer, the athletic apparel maker recalled 17 percent of its inventory at a cost of $67 million. The company had previously identified risks related to fabric supply and quality. The CEO said the issue was inadequate testing.

Analysts raised concerns about the company’s controls, including oversight of factories and product quality. A case study by Stanford University professors noted that Lululemon’s episode illustrated a common disconnect between identifying risks and being prepared to manage them when they materialize. Lululemon’s reporting and analysis of risks was also inadequate, especially as related to social media. In addition, the case study highlighted the need for a system to escalate risk-related issues to the board.

ERM Case Study: Kodak

Once an iconic brand, the photo film company failed for decades to act on the threat that digital photography posed to its business and eventually filed for bankruptcy in 2012. The company’s own research in 1981 found that digital photos could ultimately replace Kodak’s film technology and estimated it had 10 years to prepare.

Unfortunately, Kodak did not prepare and stayed locked into the film paradigm. The board reinforced this course when in 1989 it chose as CEO a candidate who came from the film business over an executive interested in digital technology.

Had the company acknowledged the risks and employed ERM strategies, it might have pursued a variety of strategies to remain successful. The company’s rival, Fuji Film, took the money it made from film and invested in new initiatives, some of which paid off. Kodak, on the other hand, kept investing in the old core business.

Case Studies of Successful Enterprise Risk Management

Successful enterprise risk management usually requires strong performance in multiple dimensions, and is therefore more likely to occur in organizations where ERM has matured. The following examples of enterprise risk management can be considered success stories.

ERM Case Study: Statoil

A major global oil producer, Statoil of Norway stands out for the way it practices ERM by looking at both downside risk and upside potential. Taking risks is vital in a business that depends on finding new oil reserves.

According to a case study, the company developed its own framework founded on two basic goals: creating value and avoiding accidents.

The company aims to understand risks thoroughly, and unlike many ERM programs, Statoil maps risks on both the downside and upside. It graphs risk on probability vs. impact on pre-tax earnings, and it examines each risk from both positive and negative perspectives.

For example, the case study cites a risk that the company assessed as having a 5 percent probability of a somewhat better-than-expected outcome but a 10 percent probability of a significant loss relative to forecast. In this case, the downside risk was greater than the upside potential.

ERM Case Study: Lego

The Danish toy maker’s ERM evolved over the following four phases, according to a case study by one of the chief architects of its program:

- Traditional management of financial, operational, and other risks. Strategic risk management joined the ERM program in 2006.

- The company added Monte Carlo simulations in 2008 to model financial performance volatility so that budgeting and financial processes could incorporate risk management. The technique is used in budget simulations, to assess risk in its credit portfolio, and to consolidate risk exposure.

- Active risk and opportunity planning is part of making a business case for new projects before final decisions.

- The company prepares for uncertainty so that long-term strategies remain relevant and resilient under different scenarios.

As part of its scenario modeling, Lego developed its PAPA (park, adapt, prepare, act) model.

- Park: The company parks risks that occur slowly and have a low probability of happening, meaning it does not forget nor actively deal with them.

- Adapt: This response is for risks that evolve slowly and are certain or highly probable to occur. For example, a risk in this category is the changing nature of play and the evolution of buying power in different parts of the world. In this phase, the company adjusts, monitors the trend, and follows developments.

- Prepare: This category includes risks that have a low probability of occurring — but when they do, they emerge rapidly. These risks go into the ERM risk database with contingency plans, early warning indicators, and mitigation measures in place.

- Act: These are high-probability, fast-moving risks that must be acted upon to maintain strategy. For example, developments around connectivity, mobile devices, and online activity are in this category because of the rapid pace of change and the influence on the way children play.

Lego views risk management as a way to better equip itself to take risks than its competitors. In the case study, the writer likens this approach to the need for the fastest race cars to have the best brakes and steering to achieve top speeds.

ERM Case Study: University of California

The University of California, one of the biggest U.S. public university systems, introduced a new view of risk to its workforce when it implemented enterprise risk management in 2005. Previously, the function was merely seen as a compliance requirement.

ERM became a way to support the university’s mission of education and research, drawing on collaboration of the system’s employees across departments. “Our philosophy is, ‘Everyone is a risk manager,’” Erike Young, deputy director of ERM told Treasury and Risk magazine. “Anyone who’s in a management position technically manages some type of risk.”

The university faces a diverse set of risks, including cybersecurity, hospital liability, reduced government financial support, and earthquakes.

The ERM department had to overhaul systems to create a unified view of risk because its information and processes were not linked. Software enabled both an organizational picture of risk and highly detailed drilldowns on individual risks. Risk managers also developed tools for risk assessment, risk ranking, and risk modeling.

Better risk management has provided more than $100 million in annual cost savings and nearly $500 million in cost avoidance, according to UC officials.

UC drives ERM with risk management departments at each of its 10 locations and leverages university subject matter experts to form multidisciplinary workgroups that develop process improvements.

APQC, a standards quality organization, recognized UC as a top global ERM practice organization, and the university system has won other awards. The university says in 2010 it was the first nonfinancial organization to win credit-rating agency recognition of its ERM program.

Examples of How Technology Is Transforming Enterprise Risk Management

Business intelligence software has propelled major progress in enterprise risk management because the technology enables risk managers to bring their information together, analyze it, and forecast how risk scenarios would impact their business.

ERM organizations are using computing and data-handling advancements such as blockchain for new innovations in strengthening risk management. Following are case studies of a few examples.

ERM Case Study: Bank of New York Mellon

In 2021, the bank joined with Google Cloud to use machine learning and artificial intelligence to predict and reduce the risk that transactions in the $22 trillion U.S. Treasury market will fail to settle. Settlement failure means a buyer and seller do not exchange cash and securities by the close of business on the scheduled date.

The party that fails to settle is assessed a daily financial penalty, and a high level of settlement failures can indicate market liquidity problems and rising risk. BNY says that, on average, about 2 percent of transactions fail to settle.

The bank trained models with millions of trades to consider every factor that could result in settlement failure. The service uses market-wide intraday trading metrics, trading velocity, scarcity indicators, volume, the number of trades settled per hour, seasonality, issuance patterns, and other signals.

The bank said it predicts about 40 percent of settlement failures with 90 percent accuracy. But it also cautioned against overconfidence in the technology as the model continues to improve.

AI-driven forecasting reduces risk for BNY clients in the Treasury market and saves costs. For example, a predictive view of settlement risks helps bond dealers more accurately manage their liquidity buffers, avoid penalties, optimize their funding sources, and offset the risks of failed settlements. In the long run, such forecasting tools could improve the health of the financial market.

ERM Case Study: PwC

Consulting company PwC has leveraged a vast information storehouse known as a data lake to help its customers manage risk from suppliers.

A data lake stores both structured or unstructured information, meaning data in highly organized, standardized formats as well as unstandardized data. This means that everything from raw audio to credit card numbers can live in a data lake.

Using techniques pioneered in national security, PwC built a risk data lake that integrates information from client companies, public databases, user devices, and industry sources. Algorithms find patterns that can signify unidentified risks.

One of PwC’s first uses of this data lake was a program to help companies uncover risks from their vendors and suppliers. Companies can violate laws, harm their reputations, suffer fraud, and risk their proprietary information by doing business with the wrong vendor.

Today’s complex global supply chains mean companies may be several degrees removed from the source of this risk, which makes it hard to spot and mitigate. For example, a product made with outlawed child labor could be traded through several intermediaries before it reaches a retailer.

PwC’s service helps companies recognize risk beyond their primary vendors and continue to monitor that risk over time as more information enters the data lake.

ERM Case Study: Financial Services

As analytics have become a pillar of forecasting and risk management for banks and other financial institutions, a new risk has emerged: model risk . This refers to the risk that machine-learning models will lead users to an unreliable understanding of risk or have unintended consequences.

For example, a 6 percent drop in the value of the British pound over the course of a few minutes in 2016 stemmed from currency trading algorithms that spiralled into a negative loop. A Twitter-reading program began an automated selling of the pound after comments by a French official, and other selling algorithms kicked in once the currency dropped below a certain level.

U.S. banking regulators are so concerned about model risk that the Federal Reserve set up a model validation council in 2012 to assess the models that banks use in running risk simulations for capital adequacy requirements. Regulators in Europe and elsewhere also require model validation.

A form of managing risk from a risk-management tool, model validation is an effort to reduce risk from machine learning. The technology-driven rise in modeling capacity has caused such models to proliferate, and banks can use hundreds of models to assess different risks.

Model risk management can reduce rising costs for modeling by an estimated 20 to 30 percent by building a validation workflow, prioritizing models that are most important to business decisions, and implementing automation for testing and other tasks, according to McKinsey.

Streamline Your Enterprise Risk Management Efforts with Real-Time Work Management in Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.

Discover why over 90% of Fortune 100 companies trust Smartsheet to get work done.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

RiskManagement →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

- Contact sales

Start free trial

How to Make a Risk Management Plan (Template Included)

You identify them, record them, monitor them and plan for them: risks are an inherent part of every project. Some project risks are bound to become problem areas—like executing a project over the holidays and having to plan the project timeline around them. But there are many risks within any given project that, without risk assessment and risk mitigation strategies, can come as unwelcome surprises to you and your project management team.

That’s where a risk management plan comes in—to help mitigate risks before they become problems. But first, what is project risk management ?

What Is Risk Management?

Risk management is an arm of project management that deals with managing potential project risks. Managing your risks is arguably one of the most important aspects of project management.

The risk management process has these main steps:

- Risk Identification: The first step to manage project risks is to identify them. You’ll need to use data sources such as information from past projects or subject matter experts’ opinions to estimate all the potential risks that can impact your project.

- Risk Assessment: Once you have identified your project risks, you’ll need to prioritize them by looking at their likelihood and level of impact.

- Risk Mitigation: Now it’s time to create a contingency plan with risk mitigation actions to manage your project risks. You also need to define which team members will be risk owners, responsible for monitoring and controlling risks.

- Risk Monitoring: Risks must be monitored throughout the project life cycle so that they can be controlled.

If one risk that’s passed your threshold has its conditions met, it can put your entire project plan in jeopardy. There isn’t usually just one risk per project, either; there are many risk categories that require assessment and discussion with your stakeholders.

That’s why risk management needs to be both a proactive and reactive process that is constant throughout the project life cycle. Now let’s define what a risk management plan is.

What Is a Risk Management Plan?

A risk management plan defines how your project’s risk management process will be executed. That includes the budget , tools and approaches that will be used to perform risk identification, assessment, mitigation and monitoring activities.

Get your free

Risk Management Plan Template

Use this free Risk Management Plan Template for Word to manage your projects better.

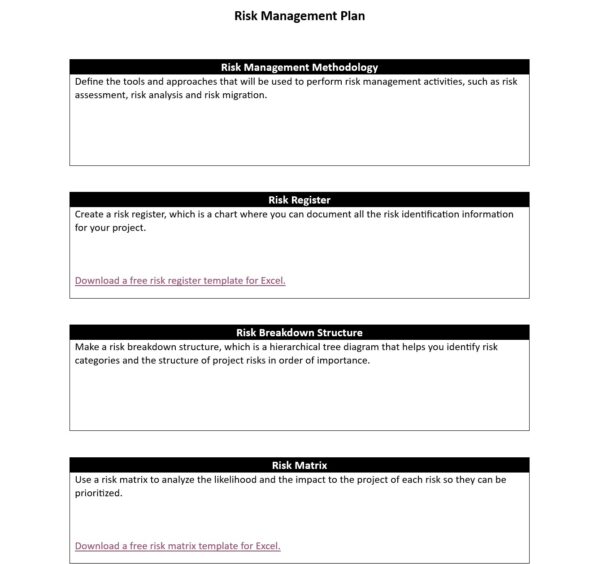

A risk management plan usually includes:

- Methodology: Define the tools and approaches that will be used to perform risk management activities such as risk assessment, risk analysis and risk mitigation strategies.

- Risk Register: A risk register is a chart where you can document all the risk identification information of your project.

- Risk Breakdown Structure: It’s a chart that allows you to identify risk categories and the hierarchical structure of project risks.

- Risk Assessment Matrix: A risk assessment matrix allows you to analyze the likelihood and the impact of project risks so you can prioritize them.

- Risk Response Plan: A risk response plan is a project management document that explains the risk mitigation strategies that will be employed to manage your project risks.

- Roles and responsibilities: The risk management team members have responsibilities as risk owners. They need to monitor project risks and supervise their risk response actions.

- Budget: Have a section where you identify the funds required to perform your risk management activities.

- Timing: Include a section to define the schedule for the risk management activities.

How to Make a Risk Management Plan

For every web design and development project, construction project or product design, there will be risks. That’s truly just the nature of project management. But that’s also why it’s always best to get ahead of them as much as possible by developing a risk management plan. The steps to make a risk management plan are outlined below.

1. Risk Identification

Risk identification occurs at the beginning of the project planning phase, as well as throughout the project life cycle. While many risks are considered “known risks,” others might require additional research to discover.

You can create a risk breakdown structure to identify all your project risks and classify them into risk categories. You can do this by interviewing all project stakeholders and industry experts. Many project risks can be divided up into risk categories, like technical or organizational, and listed out by specific sub-categories like technology, interfaces, performance, logistics, budget, etc. Additionally, create a risk register that you can share with everyone you interviewed for a centralized location of all known risks revealed during the identification phase.

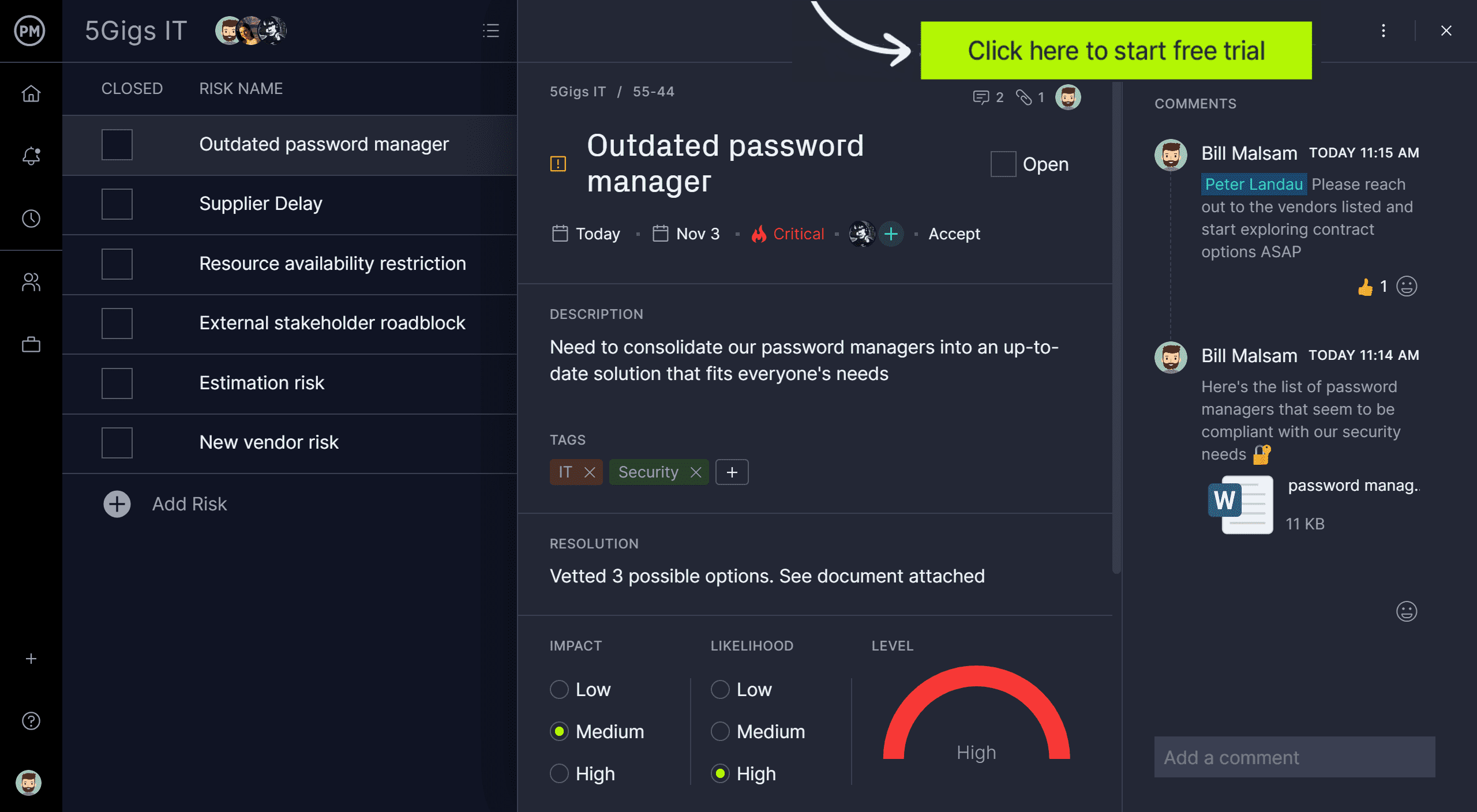

You can conveniently create a risk register for your project using online project management software. For example, use the list view on ProjectManager to capture all project risks, add what level of priority they are and assign a team member to own identify and resolve them. Better than to-do list apps, you can attach files, tags and monitor progress. Track the percentage complete and even view your risks from the project menu. Keep risks from derailing your project by signing up for a free trial of ProjectManager.

2. Risk Assessment

In this next phase, you’ll review the qualitative and quantitative impact of the risk—like the likelihood of the risk occurring versus the impact it would have on your project—and map that out into a risk assessment matrix

First, you’ll do this by assigning the risk likelihood a score from low probability to high probability. Then, you’ll map out your risk impact from low to medium to high and assign each a score. This will give you an idea of how likely the risk is to impact the success of the project, as well as how urgent the response will need to be.

To make it efficient for all risk management team members and project stakeholders to understand the risk assessment matrix, assign an overall risk score by multiplying your impact level score with your risk probability score.

3. Create a Risk Response Plan

A risk response is the action plan that is taken to mitigate project risks when they occur. The risk response plan includes the risk mitigation strategies that you’ll execute to mitigate the impact of risks in your project. Doing this usually comes with a price—at the expense of your time, or your budget. So you’ll want to allocate resources, time and money for your risk management needs prior to creating your risk management plan.

4. Assign Risk Owners

Additionally, you’ll also want to assign a risk owner to each project risk. Those risk owners become accountable for monitoring the risks that are assigned to them and supervising the execution of the risk response if needed.

Related: Risk Tracking Template

When you create your risk register and risk assessment matrix, list out the risk owners, that way no one is confused as to who will need to implement the risk response strategies once the project risks occur, and each risk owner can take immediate action.

Be sure to record what the exact risk response is for each project risk with a risk register and have your risk response plan it approved by all stakeholders before implementation. That way you can have a record of the issue and the resolution to review once the entire project is finalized.

5. Understand Your Triggers

This can happen with or without a risk already having impacted your project—especially during project milestones as a means of reviewing project progress. If they have, consider reclassifying those existing risks.

Even if those triggers haven’t been met, it’s best to come up with a backup plan as the project progresses—maybe the conditions for a certain risk won’t exist after a certain point has been reached in the project.

6. Make a Backup Plan

Consider your risk register and risk assessment matrix a living document. Your project risks can change in classification at any point during your project, and because of that, it’s important you come up with a contingency plan as part of your process.

Contingency planning includes discovering new risks during project milestones and reevaluating existing risks to see if any conditions for those risks have been met. Any reclassification of a risk means adjusting your contingency plan just a little bit.

7. Measure Your Risk Threshold

Measuring your risk threshold is all about discovering which risk is too high and consulting with your project stakeholders to consider whether or not it’s worth it to continue the project—worth it whether in time, money or scope .

Here’s how the risk threshold is typically determined: consider your risks that have a score of “very high”, or more than a few “high” scores, and consult with your leadership team and project stakeholders to determine if the project itself may be at risk of failure. Project risks that require additional consultation are risks that have passed the risk threshold.

To keep a close eye on risk as they raise issues in your project, use project management software. ProjectManager has real-time dashboards that are embedded in our tool, unlike other software where you have to build them yourself. We automatically calculate the health of your project, checking if you’re on time or running behind. Get a high-level view of how much you’re spending, progress and more. The quicker you identify risk, the faster you can resolve it.

Free Risk Management Plan Template

This free risk management plan template will help you prepare your team for any risks inherent in your project. This Word document includes sections for your risk management methodology, risk register, risk breakdown structure and more. It’s so thorough, you’re sure to be ready for whatever comes your way. Download your template today.

Best Practices for Maintaining Your Risk Management Plan

Risk management plans only fail in a few ways: incrementally because of insufficient budget, via modeling errors or by ignoring your risks outright.

Your risk management plan is one that is constantly evolving throughout the course of the project life cycle, from beginning to end. So the best practices are to focus on the monitoring phase of the risk management plan. Continue to evaluate and reevaluate your risks and their scores, and address risks at every project milestone.

Project dashboards and other risk tracking features can be a lifesaver when it comes to maintaining your risk management plan. Watch the video below to see just how important project management dashboards, live data and project reports can be when it comes to keeping your projects on track and on budget.

In addition to your routine risk monitoring, at each milestone, conduct another round of interviews with the same checklist you used at the beginning of the project, and re-interview project stakeholders, risk management team members, customers (if applicable) and industry experts.

Record their answers, adjust your risk register and risk assessment matrix if necessary, and report all relevant updates of your risk management plan to key project stakeholders. This process and level of transparency will help you to identify any new risks to be assessed and will let you know if any previous risks have expired.

How ProjectManager Can Help With Your Risk Management Plan

A risk management plan is only as good as the risk management features you have to implement and track them. ProjectManager is online project management software that lets you view risks directly in the project menu. You can tag risks as open or closed and even make a risk matrix directly in the software. You get visibility into risks and can track them in real time, sharing and viewing the risk history.

Tracking & Monitor Risks in Real Time

Managing risk is only the start. You must also monitor risk and track it from the point that you first identified it. Real-time dashboards give you a high-level view of slippage, workload, cost and more. Customizable reports can be shared with stakeholders and filtered to show only what they need to see. Risk tracking has never been easier.

Risks are bound to happen no matter the project. But if you have the right tools to better navigate the risk management planning process, you can better mitigate errors. ProjectManager is online project management software that updates in real time, giving you all the latest information on your risks, issues and changes. Start a free 30-day trial and start managing your risks better.

Deliver your projects on time and under budget

Start planning your projects.

- Predict! Software Suite

- Training and Coaching

- Predict! Risk Controller

- Rapid Deployment

- Predict! Risk Analyser

- Predict! Risk Reporter

- Predict! Risk Visualiser

- Predict! Cloud Hosting

- BOOK A DEMO

- Risk Vision

- Win Proposals with Risk Analysis

- Case Studies

- Video Gallery

- White Papers

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

Fehmarnbelt case study

. . . . . learn more

Lend Lease case study

ASC case study

Tornado IPT case study

LLW Repository case study

OHL case study

Babcock case study

HUMS case study

UK Chinook case study

- EMEA: +44 (0) 1865 987 466

- Americas: +1 (0) 437 269 0697

- APAC: +61 499 520 456

Subscribe for Updates

Copyright © 2024 risk decisions. All rights reserved.

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Company Registration No: 01878114

Powered by The Communications Group

Successful implementation of project risk management in small and medium enterprises: a cross-case analysis

International Journal of Managing Projects in Business

ISSN : 1753-8378

Article publication date: 16 February 2021

Issue publication date: 20 May 2021

Despite the emergence and strategic importance of project risk management (PRM), its diffusion is limited mainly to large companies, leaving a lack of empirical evidence addressing SMEs. Given the socio-economic importance of SMEs and their need to manage risks to ensure the success of their strategic and innovative projects, this research aims to investigate how to adopt PRM in SMEs with a positive cost–benefit ratio.

Design/methodology/approach

This study presents an exploratory and explanatory research conducted through multiple-case studies involving 10 projects performed in Spanish and Italian small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

The results obtained highlight how project features (commitment type, innovativeness, strategic relevance and managerial complexity) and firms' characteristics (sector of activity, production system and access to public incentives) influence PRM adoption, leading to different levels and types of benefits.

Originality/value

The paper offers practical indications about PRM phases, activities, tools and organizational aspects to be considered in different contexts to ensure the project's success and, ultimately, the company's growth and sustainability. Such indications could not be found in the literature.

- Project risk management

- Project management

- Successful implementation

Ferreira de Araújo Lima, P. , Marcelino-Sadaba, S. and Verbano, C. (2021), "Successful implementation of project risk management in small and medium enterprises: a cross-case analysis", International Journal of Managing Projects in Business , Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 1023-1045. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-06-2020-0203

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Priscila Ferreira de Araújo Lima, Sara Marcelino-Sadaba and Chiara Verbano

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Risk Management (RM) is a very relevant process that can be related to many companies' survival. The strategic plan of the enterprises is frequently implemented by tackling projects, so project risk management (PRM) has arisen as a very important approach. Taking into account that SMEs make a very relevant contribution to the economy ( Turner et al ., 2010 ); the analysis and the understanding of the key processes of PRM in SMEs is a relevant and pressing question, and the guidelines and tools used by large firms are usually too expensive or too complex to be suitable for SMEs ( Pereira et al. , 2015 ).

Although the relationship between the utilization of a project management (PM) methodology and project success has been well established ( Joslin and Müller, 2015 ), a review of the literature shows that there is not enough deep case analysis about how SMEs have implemented an RM methodology and how the project and the company benefit from it. Therefore, this study aims to understand how PRM can be adopted by SMEs with a positive cost–benefits ratio, considering the managerial and organizational aspects.

Experiences of empirical investigations about RM in other areas, such as portfolio management, project control, multicultural environments, stakeholders management or value creation, have been analysed, but they have not taken into account the RM and the specific characteristics of SMEs ( Teller and Kock, 2013 ; Lin et al. , 2019 ; Liu et al ., 2015 ; Xia et al. , 2018 ; Willumsen et al. , 2019 ). Rodney et al. (2015) have developed an integrated model that simultaneously represents RM and all the PM processes, including the environmental factors, but requires the project manager's effort in establishing different scenarios and identifying and analysing different risks. Nevertheless, the resources that are needed to support the application of this model, in terms of time, costs and knowledge, are usually beyond the capability and affordability of SMEs. These resource-related constraints increase the SMEs’ vulnerability and lead them to an additional need of PRM adoption ( Blanc Alquier and Lagasse Tignol, 2006 ; Dallago and Guglielmetti, 2012 ).

However, the literature on RM has focused mainly on large companies, leaving a gap of empirical evidence addressing small companies ( Kim and Vonortas, 2014 ). A recent literature review conducted on the development paths of RM in SMEs identified the PRM stream as an emerging and relevant field of application only slightly studied ( de Araújo Lima et al ., 2020 ).

Given this gap of knowledge, the current study aims at contributing meaningfully to understand how PRM processes have been implemented in SMEs. Based on the analysis of 10 cases, the benefits of efficiently conducting PRM along the project lifecycle have been identified. Moreover, this paper depicts the enabling and hindering factors for SMEs to successfully adopt PRM with a positive cost–benefit ratio, to projects with different features and in different types of industries.

Additionally, these findings have allowed the researchers to obtain different clusters with specific procedures to follow in order to obtain different levels of benefits in the project. They also provide SME's project managers indications about RM-specific tools that are appropriate for particular innovation levels or specific economic sectors.

In the following section, the result of an in-depth search for previous publications related to PRM and, more specifically, related to PRM in SMEs, has been conducted. As it is described in Section 3 , the main aim of this paper is to identify how to implement a PRM in SMEs reaching high benefits without many resources. This research has been performed through a deep multiple-case study involving 10 projects conducted in Spanish and Italian SMEs. The objectives and methodology applied in the investigation are also detailed in the referred Section. The results obtained are included in Section 4 , organized in within-case analysis and cross-cases analysis. The implications of these results are discussed in the following section, where the different clusters that have been identified – according to the level of benefits obtained through the implementation of PRM – are explained.

2. Literature review

2.1 project risk management.

The specific characteristics of the projects, such as novelty, uniqueness, high number of stakeholders and temporality, indicate that RM is useful to successfully achieve the project's objectives ( PMI, 2017 ). PRM is an integral part of PM, a process in which methods, knowledge, tools and techniques are applied to a project, integrating the various phases of a project's lifecycle in order to achieve its goal ( ISO 21500, 2012 ; PMI, 2017 ).

According to the Project Management Book of Knowledge (PMBoK), all projects involve associated risks, the positive side of which facilitates achieving certain benefits ( PMI, 2017 ). Some of the overall qualitative definitions of risk are the possibility of an unfortunate occurrence, the consequences of the activity and associated uncertainties and the deviation from a reference value ( Aven, 2016 ). A common definition of risk related to PM is an uncertain event or condition that, if takes place, has both negative and positive effects on the project's objectives ( PMI, 2017 ; ISO 31000, 2018 ; Pritchard and PMP, 2014 ; A Project risk management in SMEs PM, 2004 ; TSO, 2009 ). Therefore, organizations must achieve, through PRM, a balance between the risk assumed and the expected benefit.

RM is considered one of the most relevant areas in the training of project managers ( Nguyen et al ., 2017 ); even the project stakeholders expect them to analyse the different risks that can affect projects.

The way risk is understood and described strongly influences the way risk is analysed, and hence it may have serious implications for RM and decision-making ( Aven, 2016 ). It is also important to consider risk as systemic as it allows the investigation of the interactions between risks and encourages the management of the causality of relationships between them, thus forcing a more holistic appreciation of the project risks ( Ackermann et al. , 2007 ).

Technical-operative risks: technology selection, risks related to materials and equipment, risks related to change requests and its implementation, design risks

Organizational risks related to human factors (organizational, individual, project team): risks derived from regulations, policies, behaviour (lack of coordination/integration, human mistakes related to lack of knowledge)

Contract risks: risks of the contract related to the project

Financial/economic risks: inflation, interest rates fluctuation, exchange rate fluctuation

Political risk: environmental authorizations, governmental authorizations

The RM process defined in ISO 31000:2018 is composed of the following phases: initiate (context analysis); identify (risk identification); analyse (qualification and quantification); treatment (plan and implement) and risk monitor and control (monitoring and re-evaluation). The process must be continuous throughout the project lifecycle to increase the chances of the project's success ( Raz and Michael, 2001 ).

Within these processes, communication acquires great importance within RM and is a key element in its success, but only Portman (2009) specifically analyses it. Communication is the basis that allows the entire project team (including the main stakeholders) to understand the context of the project to develop the PRM approach. It is also necessary to define the support structure to address the risks that materialize and to monitor them by periodically communicating the status of defined indicators.

RM helps to achieve project objectives in a much more efficient way as it facilitates the proactive management of problems and the maximization of benefits if opportunities materialize ( Elkington and Smallman, 2002 ; Borge, 2002 ). Teams work with greater confidence and a lower level of stress, which increases their effectiveness ( APM, 2004 ). However, it is clear that a large number of project managers still believe that RM involves a great deal of work, for which they do not have time, and this is particularly common in projects addressed by SMEs ( Marcelino-Sádaba et al. , 2014 ).

One of the biggest issues in performing RM is the lack of systematic risk identification methods that provide characteristic taxonomies for specific project types based on lessons learned from similar projects ( Pellerin and Perrier, 2019 ).

2.2 Project risk management in SMES

The importance of PRM carried out in SMEs has been analysed and highlighted in the literature ( Blanc Alquier and Lagasse Tignol, 2006 ; Naude and Chiweshe, 2017 ). For SMEs, PRM should be carried out at an early stage in the strategic selection of projects to be implemented because their success has a great influence on its survival. However, as Vacik et al. (2018) indicate in their study, only 4% of the companies studied in their research have used risk measurement methodologies in their decision-making, carrying out the process in a qualitative way.

Some studies are available to assist SMEs in identifying and managing risks in specific business sectors; for example in ICT, where software projects are characterized by a high level of uncertainty in the definition of requirements, RM acquires great importance for SMEs project management ( Neves et al. , 2014 ). There are other studies about risk identification and their management in this area, including the one of Sharif et al. (2013) , Lam et al. (2017) , and Taherdoost et al. (2016) .

Despite the fact that different web tools have been developed for SMEs to solve their biggest difficulties in RM ( Sharif and Rozan, 2010 ; Pereira et al. , 2015 ), RM is generally carried out in person by the project manager due to the high cost of a tool and the need for qualified staff to use it.

Many sectors, such as IT, construction and design, usually work by projects and therefore have information on the specific risks associated to them. In the construction sector, for instance, different analyses, methodologies and tools for RM could be identified ( Tang et al ., 2009 ; Rostami et al. , 2015 ; Oduoza et al ., 2017 ; Hwang et al ., 2014 ). The main problems – lack of time and budget – arise when implementing RM among SMEs in this sector.

Tupa et al. (2017) and Moeuf et al . (2020) have analysed the risks and opportunities inherent to SMEs in the new paradigm brought by the Industry 4.0, in which relationships between people and systems are characterized by high connectivity and a significant quantity of data and information to manage. As a result, a new information security risk has emerged. In addition, due to the new connection systems, it will be possible to establish new information flows that update the indicators established for RM. Due to the great importance of decision-making in project success, the training of project managers in these disciplines is one of the key factors that will affect the PRM in the future.

Sanchez-Cazorla et al. (2016) concluded in their study of PRM, “Risk Identification in Megaprojects”, that further empirical studies are required to provide process information over the project lifecycle. The literature review also shows that there are not enough studies on how PRM could be adapted to SMEs.

Although Marcelino et al. (2014) established a methodology related to the project lifecycle and Lima and Verbano (2019) analysed how to implement a PRM methodology with a positive cost–benefit ratio, more studies are needed about the real practice RM in SMEs, best practices in this area and how to adapt them to different economic sectors, company sizes or types of projects addressed.

From the literature review, it could be concluded that specific methodologies are needed for SMEs in order to tackle PRM in an effective way. Nevertheless, not many methodologies in the literature are suitable for SMEs and their specific characteristics since these methodologies require a great amount of resources or the availability of specific tools and software that SMEs usually do not have.

This paper presents a more detailed analysis of the process developed to obtain good practice patterns according to the different economic sectors and types of projects.

3. Objective and methodology

What are the main RM phases, activities, tools and organizational aspects adopted by SMEs in the PRM process?

What are the evidences and outcomes of PRM adoption in SMEs?

What are the enabling and hindering factors to perform PRM in SMEs?

In particular, RQ1 and RQ3 are formulated to understand how to adopt PRM in SMEs, and RQ2 is defined to identify the evidences and outcomes deriving from a successful PRM adoption.

To achieve the research objective and answer the research questions, an exploratory and explanatory research through multiple case studies was conducted as it is the most suitable methodology for this type of research ( Voss et al ., 2002 ; Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007 ; Yin, 2009 ).

To this extent, a specific empirical framework proposed by Lima and Verbano (2019) for analysing multiple cases of PRM adoption in SMEs was used since it is the only one available in literature in order to analyse cases with objectives similar to the ones in this study. In Figure 1 the process followed to build the framework and the main constructs and variables investigated with the questionnaire can be observed.

The final questionnaire is structured in nine sections reflecting the framework:

Company and respondents profile;

Project overview (i.e. objectives, type of commitment, innovativeness, strategic relevance and managerial complexity of the project);

PRM organization (people involved, training, procedures)

PRM plan, risks and opportunities considered;

(5-8)regarding each PRM phases (risk identification, analysis, treatment, monitoring and control), activities, tools and difficulties faced; finally, PRM hindering and enabling factors were analysed for the whole process;

Evidences and outcomes of the PRM adoption (i.e. the benefits, time and costs of PRM implementation).

The questionnaire included close-ended questions (i.e. number of employees, total cost of the project, etc.), perception questions on a 5-point Likert scale (regarding for example the level of technology innovativeness of the project and the benefits obtained from PRM) and open-ended questions (concerning, for example, the activities and tools adopted and the difficulties faced in each PRM phase, the enabling and hindering factors for PRM adoption). The choice of the type of questions depends on:

the qualitative or quantitative nature of the specific object investigated,