Yale Economic Growth Center

Agte et al.: "Gender Gaps and Economic Growth: Why Haven't Women Won Globally (Yet)?"

EGC Discussion Paper No. 1105, May, 2024, by members of the Gender and Growth Gaps project team: Patrick Agte, Orazio Attanasio, Pinelopi K. Goldberg, Aishwarya Lakshmi Ratan, Rohini Pande, Michael Peters, Charity Troyer Moore, and Fabrizio Zilibotti.

Does economic growth close labor market-linked gender gaps that disadvantage women? Conversely, do gender inequalities in the labor market impede growth? To inform these questions, we conduct two analyses. First, we estimate regressions using data on gender gaps in a range of labor market outcomes from 153 countries spanning two decades (1998-2018). Second, we conduct a systematic review of the recent economics literature on gender gaps in labor markets, examining 16 journals over 21 years. Our empirical analysis demonstrates that growth is not a panacea. While economic gender gaps have narrowed and growth is associated with gender gap closures specifically in incidence of paid work, the relationship between growth and labor market gaps is otherwise mixed, and results vary by specification. This result reflects, in part, the gendered nature of structural transformation, in which growth leads men to transition from agriculture to industry and services while many women exit the labor force. Disparities in hours worked and wages persist despite growth, and heterogeneity in trends and levels between regions highlight the importance of local institutions. To better understand whether gender inequalities impeded growth, we explore a nascent literature that shows that reducing gender gaps in labor markets increases aggregate productivity. Our broader review highlights how traditional explanations for gender differences do not adequately explain existing gaps and how policy responses need to be sensitive to the changing nature of economic growth. We conclude by posing open questions for future research.

P. Agte, O. Attanasio, P. Goldberg, A. Lakshmi Ratan, R. Pande, M. Peters, C. Troyer Moore, and F. Zilibotti. "Gender Gaps and Economic Growth: Why Haven't Women Won Globally (Yet)?" EGC Discussion Paper No. 1105.

View Publication

- EGC Discussion Papers on EliScholar

Report | Wages, Incomes, and Wealth

“Women’s work” and the gender pay gap : How discrimination, societal norms, and other forces affect women’s occupational choices—and their pay

Report • By Jessica Schieder and Elise Gould • July 20, 2016

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

What this report finds: Women are paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to men—despite the fact that over the last several decades millions more women have joined the workforce and made huge gains in their educational attainment. Too often it is assumed that this pay gap is not evidence of discrimination, but is instead a statistical artifact of failing to adjust for factors that could drive earnings differences between men and women. However, these factors—particularly occupational differences between women and men—are themselves often affected by gender bias. For example, by the time a woman earns her first dollar, her occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations set by those who raised her, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work–family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society. In other words, even though women disproportionately enter lower-paid, female-dominated occupations, this decision is shaped by discrimination, societal norms, and other forces beyond women’s control.

Why it matters, and how to fix it: The gender wage gap is real—and hurts women across the board by suppressing their earnings and making it harder to balance work and family. Serious attempts to understand the gender wage gap should not include shifting the blame to women for not earning more. Rather, these attempts should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for women at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

Introduction and key findings

Women are paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to men (Hegewisch and DuMonthier 2016). This is despite the fact that over the last several decades millions more women have joined the workforce and made huge gains in their educational attainment.

Critics of this widely cited statistic claim it is not solid evidence of economic discrimination against women because it is unadjusted for characteristics other than gender that can affect earnings, such as years of education, work experience, and location. Many of these skeptics contend that the gender wage gap is driven not by discrimination, but instead by voluntary choices made by men and women—particularly the choice of occupation in which they work. And occupational differences certainly do matter—occupation and industry account for about half of the overall gender wage gap (Blau and Kahn 2016).

To isolate the impact of overt gender discrimination—such as a woman being paid less than her male coworker for doing the exact same job—it is typical to adjust for such characteristics. But these adjusted statistics can radically understate the potential for gender discrimination to suppress women’s earnings. This is because gender discrimination does not occur only in employers’ pay-setting practices. It can happen at every stage leading to women’s labor market outcomes.

Take one key example: occupation of employment. While controlling for occupation does indeed reduce the measured gender wage gap, the sorting of genders into different occupations can itself be driven (at least in part) by discrimination. By the time a woman earns her first dollar, her occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations set by those who raised her, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work–family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society. In other words, even though women disproportionately enter lower-paid, female-dominated occupations, this decision is shaped by discrimination, societal norms, and other forces beyond women’s control.

This paper explains why gender occupational sorting is itself part of the discrimination women face, examines how this sorting is shaped by societal and economic forces, and explains that gender pay gaps are present even within occupations.

Key points include:

- Gender pay gaps within occupations persist, even after accounting for years of experience, hours worked, and education.

- Decisions women make about their occupation and career do not happen in a vacuum—they are also shaped by society.

- The long hours required by the highest-paid occupations can make it difficult for women to succeed, since women tend to shoulder the majority of family caretaking duties.

- Many professions dominated by women are low paid, and professions that have become female-dominated have become lower paid.

This report examines wages on an hourly basis. Technically, this is an adjusted gender wage gap measure. As opposed to weekly or annual earnings, hourly earnings ignore the fact that men work more hours on average throughout a week or year. Thus, the hourly gender wage gap is a bit smaller than the 79 percent figure cited earlier. This minor adjustment allows for a comparison of women’s and men’s wages without assuming that women, who still shoulder a disproportionate amount of responsibilities at home, would be able or willing to work as many hours as their male counterparts. Examining the hourly gender wage gap allows for a more thorough conversation about how many factors create the wage gap women experience when they cash their paychecks.

Within-occupation gender wage gaps are large—and persist after controlling for education and other factors

Those keen on downplaying the gender wage gap often claim women voluntarily choose lower pay by disproportionately going into stereotypically female professions or by seeking out lower-paid positions. But even when men and women work in the same occupation—whether as hairdressers, cosmetologists, nurses, teachers, computer engineers, mechanical engineers, or construction workers—men make more, on average, than women (CPS microdata 2011–2015).

As a thought experiment, imagine if women’s occupational distribution mirrored men’s. For example, if 2 percent of men are carpenters, suppose 2 percent of women become carpenters. What would this do to the wage gap? After controlling for differences in education and preferences for full-time work, Goldin (2014) finds that 32 percent of the gender pay gap would be closed.

However, leaving women in their current occupations and just closing the gaps between women and their male counterparts within occupations (e.g., if male and female civil engineers made the same per hour) would close 68 percent of the gap. This means examining why waiters and waitresses, for example, with the same education and work experience do not make the same amount per hour. To quote Goldin:

Another way to measure the effect of occupation is to ask what would happen to the aggregate gender gap if one equalized earnings by gender within each occupation or, instead, evened their proportions for each occupation. The answer is that equalizing earnings within each occupation matters far more than equalizing the proportions by each occupation. (Goldin 2014)

This phenomenon is not limited to low-skilled occupations, and women cannot educate themselves out of the gender wage gap (at least in terms of broad formal credentials). Indeed, women’s educational attainment outpaces men’s; 37.0 percent of women have a college or advanced degree, as compared with 32.5 percent of men (CPS ORG 2015). Furthermore, women earn less per hour at every education level, on average. As shown in Figure A , men with a college degree make more per hour than women with an advanced degree. Likewise, men with a high school degree make more per hour than women who attended college but did not graduate. Even straight out of college, women make $4 less per hour than men—a gap that has grown since 2000 (Kroeger, Cooke, and Gould 2016).

Women earn less than men at every education level : Average hourly wages, by gender and education, 2015

The data below can be saved or copied directly into Excel.

The data underlying the figure.

Source : EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Copy the code below to embed this chart on your website.

Steering women to certain educational and professional career paths—as well as outright discrimination—can lead to different occupational outcomes

The gender pay gap is driven at least in part by the cumulative impact of many instances over the course of women’s lives when they are treated differently than their male peers. Girls can be steered toward gender-normative careers from a very early age. At a time when parental influence is key, parents are often more likely to expect their sons, rather than their daughters, to work in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) fields, even when their daughters perform at the same level in mathematics (OECD 2015).

Expectations can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. A 2005 study found third-grade girls rated their math competency scores much lower than boys’, even when these girls’ performance did not lag behind that of their male counterparts (Herbert and Stipek 2005). Similarly, in states where people were more likely to say that “women [are] better suited for home” and “math is for boys,” girls were more likely to have lower math scores and higher reading scores (Pope and Sydnor 2010). While this only establishes a correlation, there is no reason to believe gender aptitude in reading and math would otherwise be related to geography. Parental expectations can impact performance by influencing their children’s self-confidence because self-confidence is associated with higher test scores (OECD 2015).

By the time young women graduate from high school and enter college, they already evaluate their career opportunities differently than young men do. Figure B shows college freshmen’s intended majors by gender. While women have increasingly gone into medical school and continue to dominate the nursing field, women are significantly less likely to arrive at college interested in engineering, computer science, or physics, as compared with their male counterparts.

Women arrive at college less interested in STEM fields as compared with their male counterparts : Intent of first-year college students to major in select STEM fields, by gender, 2014

Source: EPI adaptation of Corbett and Hill (2015) analysis of Eagan et al. (2014)

These decisions to allow doors to lucrative job opportunities to close do not take place in a vacuum. Many factors might make it difficult for a young woman to see herself working in computer science or a similarly remunerative field. A particularly depressing example is the well-publicized evidence of sexism in the tech industry (Hewlett et al. 2008). Unfortunately, tech isn’t the only STEM field with this problem.

Young women may be discouraged from certain career paths because of industry culture. Even for women who go against the grain and pursue STEM careers, if employers in the industry foster an environment hostile to women’s participation, the share of women in these occupations will be limited. One 2008 study found that “52 percent of highly qualified females working for SET [science, technology, and engineering] companies quit their jobs, driven out by hostile work environments and extreme job pressures” (Hewlett et al. 2008). Extreme job pressures are defined as working more than 100 hours per week, needing to be available 24/7, working with or managing colleagues in multiple time zones, and feeling pressure to put in extensive face time (Hewlett et al. 2008). As compared with men, more than twice as many women engage in housework on a daily basis, and women spend twice as much time caring for other household members (BLS 2015). Because of these cultural norms, women are less likely to be able to handle these extreme work pressures. In addition, 63 percent of women in SET workplaces experience sexual harassment (Hewlett et al. 2008). To make matters worse, 51 percent abandon their SET training when they quit their job. All of these factors play a role in steering women away from highly paid occupations, particularly in STEM fields.

The long hours required for some of the highest-paid occupations are incompatible with historically gendered family responsibilities

Those seeking to downplay the gender wage gap often suggest that women who work hard enough and reach the apex of their field will see the full fruits of their labor. In reality, however, the gender wage gap is wider for those with higher earnings. Women in the top 95th percentile of the wage distribution experience a much larger gender pay gap than lower-paid women.

Again, this large gender pay gap between the highest earners is partially driven by gender bias. Harvard economist Claudia Goldin (2014) posits that high-wage firms have adopted pay-setting practices that disproportionately reward individuals who work very long and very particular hours. This means that even if men and women are equally productive per hour, individuals—disproportionately men—who are more likely to work excessive hours and be available at particular off-hours are paid more highly (Hersch and Stratton 2002; Goldin 2014; Landers, Rebitzer, and Taylor 1996).

It is clear why this disadvantages women. Social norms and expectations exert pressure on women to bear a disproportionate share of domestic work—particularly caring for children and elderly parents. This can make it particularly difficult for them (relative to their male peers) to be available at the drop of a hat on a Sunday evening after working a 60-hour week. To the extent that availability to work long and particular hours makes the difference between getting a promotion or seeing one’s career stagnate, women are disadvantaged.

And this disadvantage is reinforced in a vicious circle. Imagine a household where both members of a male–female couple have similarly demanding jobs. One partner’s career is likely to be prioritized if a grandparent is hospitalized or a child’s babysitter is sick. If the past history of employer pay-setting practices that disadvantage women has led to an already-existing gender wage gap for this couple, it can be seen as “rational” for this couple to prioritize the male’s career. This perpetuates the expectation that it always makes sense for women to shoulder the majority of domestic work, and further exacerbates the gender wage gap.

Female-dominated professions pay less, but it’s a chicken-and-egg phenomenon

Many women do go into low-paying female-dominated industries. Home health aides, for example, are much more likely to be women. But research suggests that women are making a logical choice, given existing constraints . This is because they will likely not see a significant pay boost if they try to buck convention and enter male-dominated occupations. Exceptions certainly exist, particularly in the civil service or in unionized workplaces (Anderson, Hegewisch, and Hayes 2015). However, if women in female-dominated occupations were to go into male-dominated occupations, they would often have similar or lower expected wages as compared with their female counterparts in female-dominated occupations (Pitts 2002). Thus, many women going into female-dominated occupations are actually situating themselves to earn higher wages. These choices thereby maximize their wages (Pitts 2002). This holds true for all categories of women except for the most educated, who are more likely to earn more in a male profession than a female profession. There is also evidence that if it becomes more lucrative for women to move into male-dominated professions, women will do exactly this (Pitts 2002). In short, occupational choice is heavily influenced by existing constraints based on gender and pay-setting across occupations.

To make matters worse, when women increasingly enter a field, the average pay in that field tends to decline, relative to other fields. Levanon, England, and Allison (2009) found that when more women entered an industry, the relative pay of that industry 10 years later was lower. Specifically, they found evidence of devaluation—meaning the proportion of women in an occupation impacts the pay for that industry because work done by women is devalued.

Computer programming is an example of a field that has shifted from being a very mixed profession, often associated with secretarial work in the past, to being a lucrative, male-dominated profession (Miller 2016; Oldenziel 1999). While computer programming has evolved into a more technically demanding occupation in recent decades, there is no skills-based reason why the field needed to become such a male-dominated profession. When men flooded the field, pay went up. In contrast, when women became park rangers, pay in that field went down (Miller 2016).

Further compounding this problem is that many professions where pay is set too low by market forces, but which clearly provide enormous social benefits when done well, are female-dominated. Key examples range from home health workers who care for seniors, to teachers and child care workers who educate today’s children. If closing gender pay differences can help boost pay and professionalism in these key sectors, it would be a huge win for the economy and society.

The gender wage gap is real—and hurts women across the board. Too often it is assumed that this gap is not evidence of discrimination, but is instead a statistical artifact of failing to adjust for factors that could drive earnings differences between men and women. However, these factors—particularly occupational differences between women and men—are themselves affected by gender bias. Serious attempts to understand the gender wage gap should not include shifting the blame to women for not earning more. Rather, these attempts should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for women at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

— This paper was made possible by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

— The authors wish to thank Josh Bivens, Barbara Gault, and Heidi Hartman for their helpful comments.

About the authors

Jessica Schieder joined EPI in 2015. As a research assistant, she supports the research of EPI’s economists on topics such as the labor market, wage trends, executive compensation, and inequality. Prior to joining EPI, Jessica worked at the Center for Effective Government (formerly OMB Watch) as a revenue and spending policies analyst, where she examined how budget and tax policy decisions impact working families. She holds a bachelor’s degree in international political economy from Georgetown University.

Elise Gould , senior economist, joined EPI in 2003. Her research areas include wages, poverty, economic mobility, and health care. She is a co-author of The State of Working America, 12th Edition . In the past, she has authored a chapter on health in The State of Working America 2008/09; co-authored a book on health insurance coverage in retirement; published in venues such as The Chronicle of Higher Education , Challenge Magazine , and Tax Notes; and written for academic journals including Health Economics , Health Affairs, Journal of Aging and Social Policy, Risk Management & Insurance Review, Environmental Health Perspectives , and International Journal of Health Services . She holds a master’s in public affairs from the University of Texas at Austin and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Anderson, Julie, Ariane Hegewisch, and Jeff Hayes 2015. The Union Advantage for Women . Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn 2016. The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations . National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 21913.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2015. American Time Use Survey public data series. U.S. Census Bureau.

Corbett, Christianne, and Catherine Hill. 2015. Solving the Equation: The Variables for Women’s Success in Engineering and Computing . American Association of University Women (AAUW).

Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata (CPS ORG). 2011–2015. Survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics [ machine-readable microdata file ]. U.S. Census Bureau.

Goldin, Claudia. 2014. “ A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter .” American Economic Review, vol. 104, no. 4, 1091–1119.

Hegewisch, Ariane, and Asha DuMonthier. 2016. The Gender Wage Gap: 2015; Earnings Differences by Race and Ethnicity . Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Herbert, Jennifer, and Deborah Stipek. 2005. “The Emergence of Gender Difference in Children’s Perceptions of Their Academic Competence.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology , vol. 26, no. 3, 276–295.

Hersch, Joni, and Leslie S. Stratton. 2002. “ Housework and Wages .” The Journal of Human Resources , vol. 37, no. 1, 217–229.

Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, Carolyn Buck Luce, Lisa J. Servon, Laura Sherbin, Peggy Shiller, Eytan Sosnovich, and Karen Sumberg. 2008. The Athena Factor: Reversing the Brain Drain in Science, Engineering, and Technology . Harvard Business Review.

Kroeger, Teresa, Tanyell Cooke, and Elise Gould. 2016. The Class of 2016: The Labor Market Is Still Far from Ideal for Young Graduates . Economic Policy Institute.

Landers, Renee M., James B. Rebitzer, and Lowell J. Taylor. 1996. “ Rat Race Redux: Adverse Selection in the Determination of Work Hours in Law Firms .” American Economic Review , vol. 86, no. 3, 329–348.

Levanon, Asaf, Paula England, and Paul Allison. 2009. “Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950-2000 U.S. Census Data.” Social Forces, vol. 88, no. 2, 865–892.

Miller, Claire Cain. 2016. “As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops.” New York Times , March 18.

Oldenziel, Ruth. 1999. Making Technology Masculine: Men, Women, and Modern Machines in America, 1870-1945 . Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. The ABC of Gender Equality in Education: Aptitude, Behavior, Confidence .

Pitts, Melissa M. 2002. Why Choose Women’s Work If It Pays Less? A Structural Model of Occupational Choice. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Paper 2002-30.

Pope, Devin G., and Justin R. Sydnor. 2010. “ Geographic Variation in the Gender Differences in Test Scores .” Journal of Economic Perspectives , vol. 24, no. 2, 95–108.

See related work on Wages, Incomes, and Wealth | Women

See more work by Jessica Schieder and Elise Gould

The Gender Wage Gap: Skills, Sorting, and Returns

Humphries, John Eric, Juanna Schrøter Joensen, and Gregory F. Veramendi. 2024. "The Gender Wage Gap: Skills, Sorting, and Returns." AEA Papers and Proceedings, 114: 259-64.

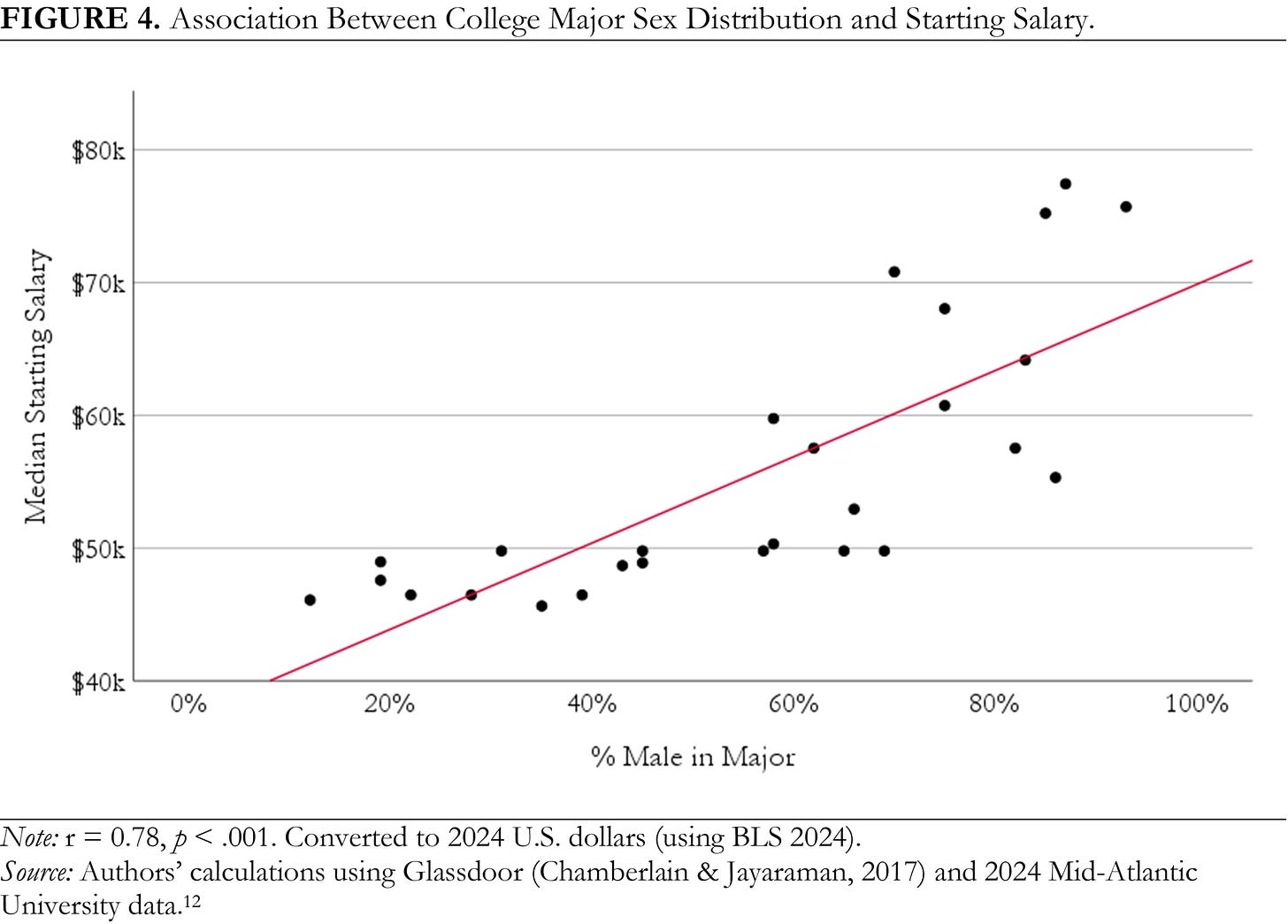

There is a large gender wage gap among college graduates. This gender gap could be partially driven by differences in college major and prior skills. We use Swedish register data to study how much of the gender gap can be explained by differences in majors, skills, and skill prices. College majors explain 60 percent of the gender wage gap, but large gaps remain within majors. We find that within-major wage gaps are driven by neither differences in multidimensional skills nor returns to these skills. In fact, women are positively selected in terms of college preparation and skills in almost every major.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Gender pay gap in U.S. hasn’t changed much in two decades

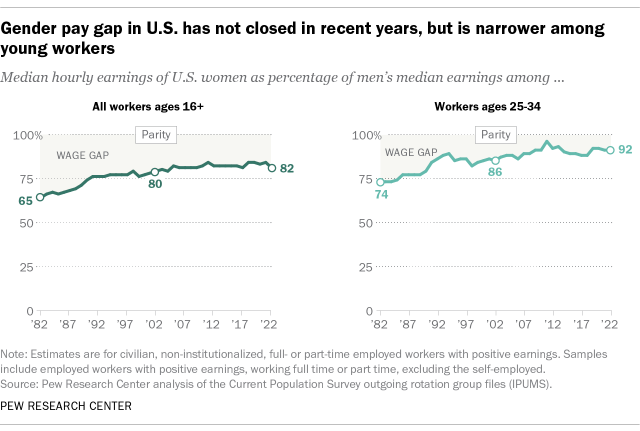

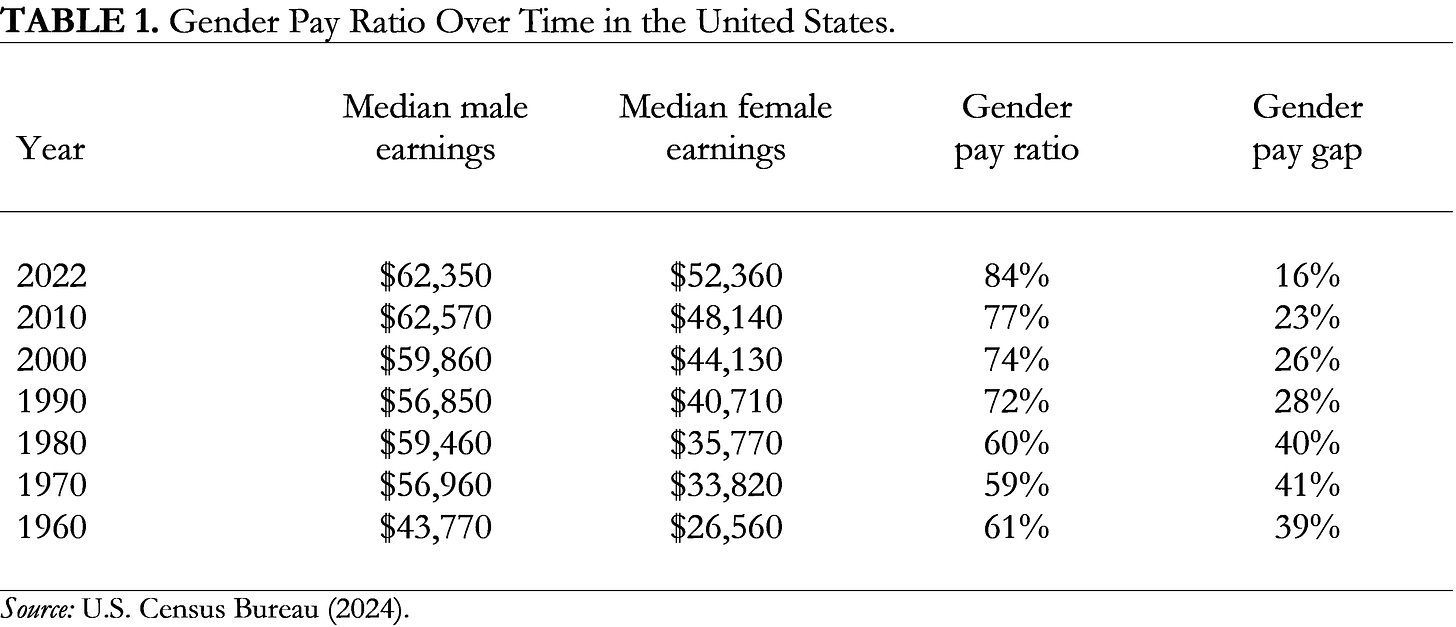

The gender gap in pay has remained relatively stable in the United States over the past 20 years or so. In 2022, women earned an average of 82% of what men earned, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of median hourly earnings of both full- and part-time workers. These results are similar to where the pay gap stood in 2002, when women earned 80% as much as men.

As has long been the case, the wage gap is smaller for workers ages 25 to 34 than for all workers 16 and older. In 2022, women ages 25 to 34 earned an average of 92 cents for every dollar earned by a man in the same age group – an 8-cent gap. By comparison, the gender pay gap among workers of all ages that year was 18 cents.

While the gender pay gap has not changed much in the last two decades, it has narrowed considerably when looking at the longer term, both among all workers ages 16 and older and among those ages 25 to 34. The estimated 18-cent gender pay gap among all workers in 2022 was down from 35 cents in 1982. And the 8-cent gap among workers ages 25 to 34 in 2022 was down from a 26-cent gap four decades earlier.

The gender pay gap measures the difference in median hourly earnings between men and women who work full or part time in the United States. Pew Research Center’s estimate of the pay gap is based on an analysis of Current Population Survey (CPS) monthly outgoing rotation group files ( IPUMS ) from January 1982 to December 2022, combined to create annual files. To understand how we calculate the gender pay gap, read our 2013 post, “How Pew Research Center measured the gender pay gap.”

The COVID-19 outbreak affected data collection efforts by the U.S. government in its surveys, especially in 2020 and 2021, limiting in-person data collection and affecting response rates. It is possible that some measures of economic outcomes and how they vary across demographic groups are affected by these changes in data collection.

In addition to findings about the gender wage gap, this analysis includes information from a Pew Research Center survey about the perceived reasons for the pay gap, as well as the pressures and career goals of U.S. men and women. The survey was conducted among 5,098 adults and includes a subset of questions asked only for 2,048 adults who are employed part time or full time, from Oct. 10-16, 2022. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used in this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology .

The U.S. Census Bureau has also analyzed the gender pay gap, though its analysis looks only at full-time workers (as opposed to full- and part-time workers). In 2021, full-time, year-round working women earned 84% of what their male counterparts earned, on average, according to the Census Bureau’s most recent analysis.

Much of the gender pay gap has been explained by measurable factors such as educational attainment, occupational segregation and work experience. The narrowing of the gap over the long term is attributable in large part to gains women have made in each of these dimensions.

Related: The Enduring Grip of the Gender Pay Gap

Even though women have increased their presence in higher-paying jobs traditionally dominated by men, such as professional and managerial positions, women as a whole continue to be overrepresented in lower-paying occupations relative to their share of the workforce. This may contribute to gender differences in pay.

Other factors that are difficult to measure, including gender discrimination, may also contribute to the ongoing wage discrepancy.

Perceived reasons for the gender wage gap

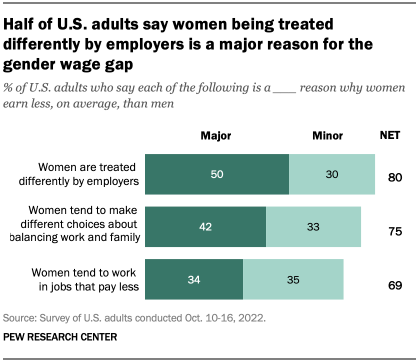

When asked about the factors that may play a role in the gender wage gap, half of U.S. adults point to women being treated differently by employers as a major reason, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in October 2022. Smaller shares point to women making different choices about how to balance work and family (42%) and working in jobs that pay less (34%).

There are some notable differences between men and women in views of what’s behind the gender wage gap. Women are much more likely than men (61% vs. 37%) to say a major reason for the gap is that employers treat women differently. And while 45% of women say a major factor is that women make different choices about how to balance work and family, men are slightly less likely to hold that view (40% say this).

Parents with children younger than 18 in the household are more likely than those who don’t have young kids at home (48% vs. 40%) to say a major reason for the pay gap is the choices that women make about how to balance family and work. On this question, differences by parental status are evident among both men and women.

Views about reasons for the gender wage gap also differ by party. About two-thirds of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (68%) say a major factor behind wage differences is that employers treat women differently, but far fewer Republicans and Republican leaners (30%) say the same. Conversely, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say women’s choices about how to balance family and work (50% vs. 36%) and their tendency to work in jobs that pay less (39% vs. 30%) are major reasons why women earn less than men.

Democratic and Republican women are more likely than their male counterparts in the same party to say a major reason for the gender wage gap is that employers treat women differently. About three-quarters of Democratic women (76%) say this, compared with 59% of Democratic men. And while 43% of Republican women say unequal treatment by employers is a major reason for the gender wage gap, just 18% of GOP men share that view.

Pressures facing working women and men

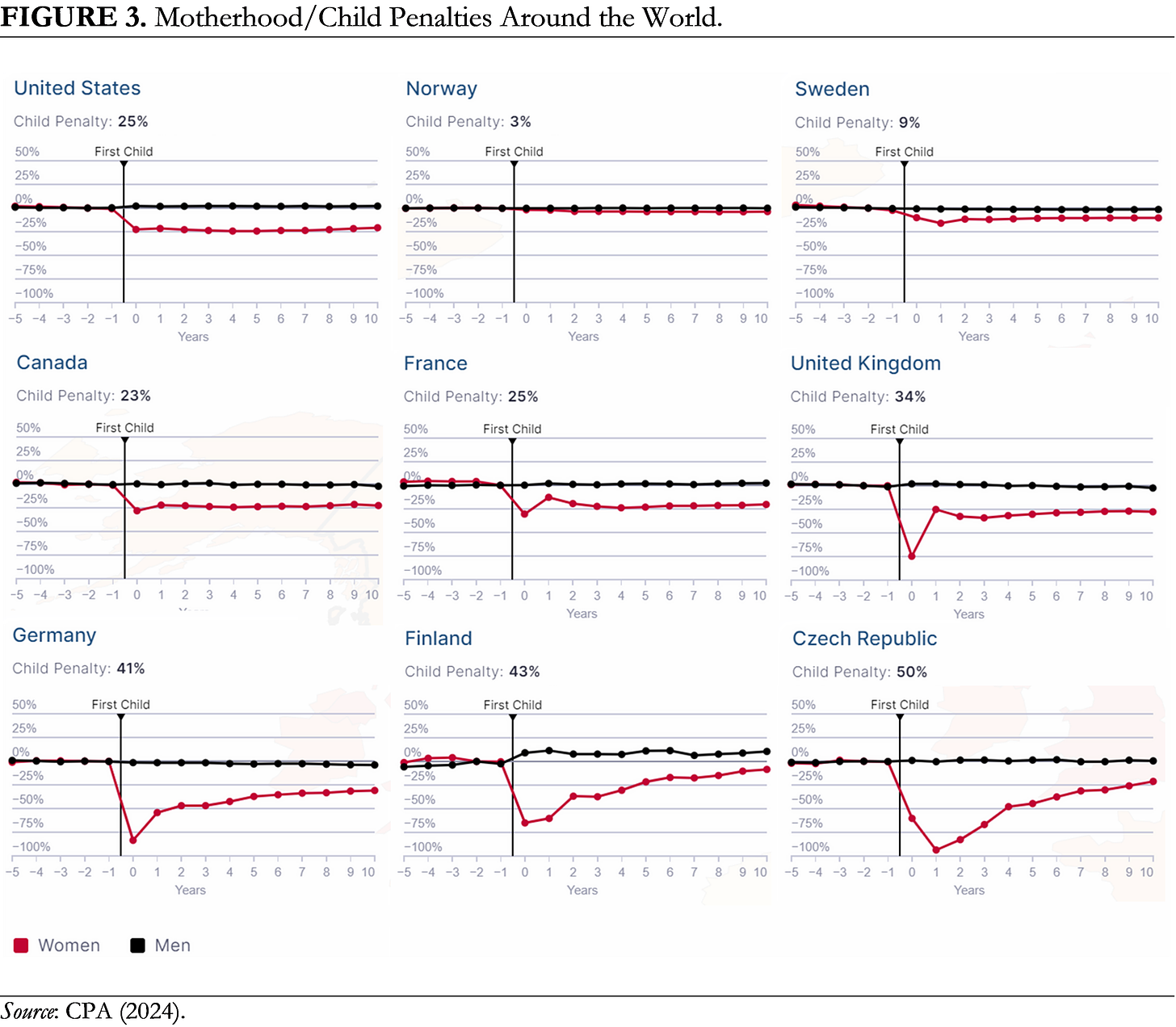

Family caregiving responsibilities bring different pressures for working women and men, and research has shown that being a mother can reduce women’s earnings , while fatherhood can increase men’s earnings .

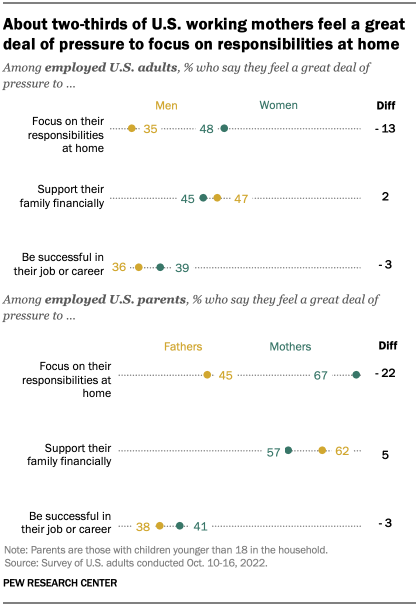

Employed women and men are about equally likely to say they feel a great deal of pressure to support their family financially and to be successful in their jobs and careers, according to the Center’s October survey. But women, and particularly working mothers, are more likely than men to say they feel a great deal of pressure to focus on responsibilities at home.

About half of employed women (48%) report feeling a great deal of pressure to focus on their responsibilities at home, compared with 35% of employed men. Among working mothers with children younger than 18 in the household, two-thirds (67%) say the same, compared with 45% of working dads.

When it comes to supporting their family financially, similar shares of working moms and dads (57% vs. 62%) report they feel a great deal of pressure, but this is driven mainly by the large share of unmarried working mothers who say they feel a great deal of pressure in this regard (77%). Among those who are married, working dads are far more likely than working moms (60% vs. 43%) to say they feel a great deal of pressure to support their family financially. (There were not enough unmarried working fathers in the sample to analyze separately.)

About four-in-ten working parents say they feel a great deal of pressure to be successful at their job or career. These findings don’t differ by gender.

Gender differences in job roles, aspirations

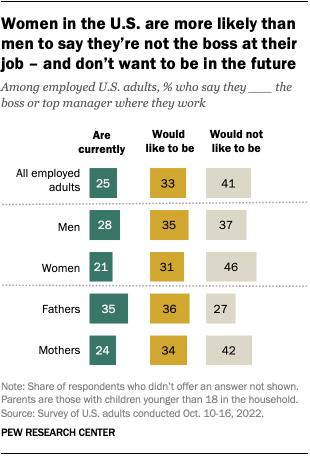

Overall, a quarter of employed U.S. adults say they are currently the boss or one of the top managers where they work, according to the Center’s survey. Another 33% say they are not currently the boss but would like to be in the future, while 41% are not and do not aspire to be the boss or one of the top managers.

Men are more likely than women to be a boss or a top manager where they work (28% vs. 21%). This is especially the case among employed fathers, 35% of whom say they are the boss or one of the top managers where they work. (The varying attitudes between fathers and men without children at least partly reflect differences in marital status and educational attainment between the two groups.)

In addition to being less likely than men to say they are currently the boss or a top manager at work, women are also more likely to say they wouldn’t want to be in this type of position in the future. More than four-in-ten employed women (46%) say this, compared with 37% of men. Similar shares of men (35%) and women (31%) say they are not currently the boss but would like to be one day. These patterns are similar among parents.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published on March 22, 2019. Anna Brown and former Pew Research Center writer/editor Amanda Barroso contributed to an earlier version of this analysis. Here are the questions used in this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology .

What is the gender wage gap in your metropolitan area? Find out with our pay gap calculator

- Gender & Work

- Gender Equality & Discrimination

- Gender Pay Gap

- Gender Roles

Carolina Aragão is a research associate focusing on social and demographic trends at Pew Research Center .

Half of Latinas Say Hispanic Women’s Situation Has Improved in the Past Decade and Expect More Gains

A majority of latinas feel pressure to support their families or to succeed at work, women have gained ground in the nation’s highest-paying occupations, but still lag behind men, diversity, equity and inclusion in the workplace, the enduring grip of the gender pay gap, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Sociol

The Gender Pay Gap: Income Inequality Over Life Course – A Multilevel Analysis

Lisa toczek.

1 Department of Medical Sociology, Institute of the History, Philosophy and Ethics of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany

2 Department of Social Medicine, Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands

Richard Peter

Maria Bohdalova , Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia

Associated Data

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the study data contain social security information. Due to legal regulations in Germany, it is not permitted to share data with social security information. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to [email protected] .

The gender pay gap has been observed for decades, and still exists. Due to a life course perspective, gender differences in income are analyzed over a period of 24 years. Therefore, this study aims to investigate income trajectories and the differences regarding men and women. Moreover, the study examines how human capital determinants, occupational positions and factors that accumulate disadvantages over time contribute to the explanation of the GPG in Germany. Therefore, this study aims to contribute to a better understanding of the GPG over the life course. The data are based on the German cohort study lidA (living at work), which links survey data individually with employment register data. Based on social security data, the income of men and women over time are analyzed using a multilevel analysis. The results show that the GPG exists in Germany over the life course: men have a higher daily average income per year than women. In addition, the income developments of men rise more sharply than those of women over time. Moreover, even after controlling for factors potentially explaining the GPG like education, work experience, occupational status or unemployment episodes the GPG persists. Concluding, further research is required that covers additional factors like individual behavior or information about the labor market structure for a better understanding of the GPG.

1 Introduction

In the European Union (EU) in 2019, women’s average gross hourly earnings were 14.1% below the earnings of men ( Eurostat, 2021a ). The gender pay gap (GPG) has existed for decades and still remains to date. According to Eurostat GPG statistics, the key priorities of gender policies are to reduce the wage differences between men and women at both the EU and national levels ( Eurostat, 2021a ). Nevertheless, the careers of men and women differ considerably in the labor market, with women being paid less than men ( Arulampalam et al., 2005 ; Radl, 2013 ; Boll et al., 2017 ). A report from the European Parliament in 2015 about gender equality assessed Germany’s performance in that field as mediocre. The federal government in Germany has already improved laws that focus on gender equality ( Botsch, 2015 ). Regarding Germany, in 2019 the earning difference between men and women were found to be 19.2% ( Eurostat, 2021a ). The reasons behind gender income inequality are complex and have multidimensional explanations.

1.1 Determinants of the GPG

The early 1990s represented a turning point for the participation of women in the labor market ( Botsch, 2015 ). In previous years, women’s participation rate in the workforce has strongly increased, from 51.9% in the year 1980 (West Germany) to 74.9% in 2019 ( OECD, 2021 ). This upward trend represents the increase of women working at older ages ( Sackmann, 2018 ). However, the gender income inequality remains. Different explaining factors of the GPG were found in previous research: patterns of employment, access to education and interruptions in the careers of men and women.

Although there are nearly equal numbers of men and women in the labor market, when considering women’s careers, various gender-specific barriers are occurring. The working patterns were found to have a relevant impact on the GPG in previous research. Atypical employment is increasing and this result in an expansion of the low-wage sector, which mainly affects women in Germany ( Botsch, 2015 ). Additionally, labor market integration of women has mainly been in jobs that provide few working hours and low wages ( Botsch, 2015 ). Moreover, part-time employment represents a common employment type in Germany, which is more frequent among women – as various studies have demonstrated – and explains the GPG significantly ( Boll et al., 2017 ; Ponthieux and Meurs, 2015 ; Boll and Leppin, 2015 ). In addition, the part-time employment occurs more often in occupations characterized by a high proportion of women and low wages ( Matteazzi et al., 2018 ; Boll and Leppin, 2015 ; Hasselhorn, 2020 ; Manzoni et al., 2014 ). Another employment type with few working hours and low pay is a special form of part-time work: marginal work. Marginal work is defined as earnings up to 450 Euros per month or up to 5.400 Euros annually. Also, it is also more common among women than among men ( Botsch, 2015 ; Broughton et al., 2016 ). The marginal part-time work has increased in nearly all EU countries, especially in Germany where it can be found to be above the EU average ( Broughton et al., 2016 ). Besides the working time, occupational status influences the wage differences of men and women. Female-dominated occupational sectors are characterized by lower wages compared to male-dominated ones ( Brynin and Perales, 2016 ). Additionally, in women-dominant industries, remunerations are less attractive and it often entails low-status work in sectors like retail, caregiving or education ( Boll and Leppin, 2015 ; Hasselhorn, 2020 ; Matteazzi et al., 2018 ; Brynin and Perales, 2016 ). Hence, working patterns such as the amount of working time or the occupational status are crucial determinants that contribute to explaining the GPG in Germany ( Blau and Kahn, 2017 ; Boll et al., 2017 ).

The access to education and vocational training are important factors, that influence the GPG. Both influence a first access to the labor market and are considered to be ‘door openers’ for the working life ( Manzoni et al., 2014 ). In Germany, education represents a largely stable variable over time, i.e. only few individuals increase their first educational attainment. Education influences the careers of men and women and can be seen as important an determinant of future earnings ( Boll et al., 2017 ; Bovens and Wille, 2017 ). Although women’s educational attainment caught up with those of men’s in recent years, for men, a higher qualification was still rewarded more than for women ( Botsch, 2015 ; Boll et al., 2017 ). Moreover, in previous research the impact of education on the GPG was not found to be consistent with different influences for men than for women ( Aisenbrey and Bruckner, 2008 ; Ponthieux and Meurs, 2015 ). Manzoni et al. (2014) found out, that the effect of education on career developments were dependent of their particular educational levels. In addition, regardless of the women’s educational catching-up in the last years, looking at older cohorts – born between 1950 and 1964 – women had a lower average level of education than men ( Boll et al., 2017 ).

An increasing GPG over time can also be the result of interruptions in careers, which are found more often for women than for men ( Eurostat, 2021a ; Boll and Leppin, 2015 ). Previous research of Boll and Leppin (2015) has identified explanations for the GPG in Germany by analyzing data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) in 2011. They demonstrated that the amount of time spent in actual work was lower for women than for men. Therefore, women gain less work experience than their male counterparts ( Boll and Leppin, 2015 ). Career interruptions not only impact the accumulation of work experience but also the scope of future work. Especially in the period of family formation higher rates of part-time employment among women can be observed ( Boll et al., 2017 ; Ponthieux and Meurs, 2015 ). Moreover, work-life interruptions such as raising children or caring for family members have a major impact on the employment development and are more likely to appear for women than for men ( Ponthieux and Meurs, 2015 ). Although the employment rate of mothers has increased in recent years in Germany, it is still considerably lower than that of fathers ( Federal Statistical Office, 2021 ). Hence, taking care of children is still attributed to mothers, to the detriment of their careers ( Botsch, 2015 ). A recent study, however, found sizable wage differences between men and women who were not parents, refuting the assumption that the GPG applies only to parents ( Joshi et al., 2020 ). Other interruptions in the working lives of men and women are caused by unemployment. Azmat et al. (2006) found that in Germany, transition rates from employment to unemployment were higher for women than for men. Career interruptions have lasting negative effects on women’s wages. Therefore, it can be useful to examine unemployment when analyzing gender inequality in the labor market ( Eurostat, 2021b ).

1.2 Theoretical Background

1.2.1 human capital model.

In previous research, economic theories had been applied to explain the income differences of men and women. Two essential factors could be found: qualification and discrimination. The human capital model claims that qualifications with greater investments can be directly related to higher wages of men and women. The earnings are assumed to be based on skills and abilities that are required through education and vocational training, and work experience ( Grybaitė, 2006 ; Lips, 2013 ; Blau and Kahn, 2007 ). Educational attainment of women has caught up in recent years ( Botsch, 2015 ). However, women’s investments in qualifications were still not equally rewarded as those of men. Therefore, the expected narrowing of the GPG was not confirmed in earlier research ( Boll et al., 2017 ; Lips, 2013 ). Another determinant of the human capital model is work experience. Labor market experience contributes to a large extent to the gender inequality in earnings ( Sierminska et al., 2010 ). Hence, work experience influences the wages of men and women. On the one hand, interruptions due to family life lower especially women’s labor market experience compared to men. On the other hand, part-time employment is more frequent among women with fewer working hours and therefore less work experience. The lesser accumulation of work experience leads to lower human capital and lower earnings for women compared with men ( Blau and Kahn, 2007 ; Mincer and Polachek, 1974 ). Nonetheless, the association of work experience and income is more complex. Regarding the wages of men and women the influence of occupation itself also needs to be considered ( Lips, 2013 ). In the paper of Polachek (1981) different occupations over the careers of men and women were explained by different labor force participation over lifetime. Referring to the human capital model, it is argued that women more likely expect discontinuous employment. Therefore, women choose occupations with fewer penalties for interruptions ( Polachek, 1981 ). However, it should be questioned if working in specific occupations can be defined as a simple choice ( Lips, 2013 ). Besides, part-time employment is found to be more frequent among women, which ultimately leads to few working hours and hence low earnings ( Botsch, 2015 ; Ponthieux and Meurs, 2015 ; Boll et al., 2017 ). Though different working hours cannot be defined as a simple choice either ( Lips, 2013 ).

Earlier criticism about the human capital model discussed that the wage differences of men and women cannot only be explained by the qualification and the labor market experience ( Grybaitė, 2006 ; Lips, 2013 ). Another theoretical approach explaining the GPG refers to labor market discriminations, which effect occupations and wages ( Boll et al., 2017 ; Grybaitė, 2006 ). On the one hand, occupational sex segregation can be associated with income differences of men and women. The different occupational allocation in the labor market of men and women are defined as allocative discrimination ( Petersen and Morgan, 1995 ). In addition, occupations in female-dominated sectors are mostly characterized by low-wages compared to more male-dominated occupations ( Brynin and Perales, 2016 ). On the other hand, even with equal occupational positions and skill requirements women mostly earn less than men, this refers to the valuative discrimination ( Petersen and Morgan, 1995 ). Even within female-dominated jobs a certain discrimination exists, with men being paid more than women for the same occupation. Additionally, employment sectors with a large number of female workers are more likely to be associated with less prestige and lower earnings ( Lips, 2013 ). Achatz et al. (2005) analyzed the GPG with an employer-employee database in Germany. The authors examined the discrimination in the allocation of jobs, differences in productivity-, and firm-related characteristics. They found out that in occupational groups within companies, the wages decreased with a higher share of women in a group. Additionally, a higher proportion of women in a groups resulted in a higher wage loss for women than for men ( Achatz et al., 2005 ).

Although relevant criticism of the human capital model exists, its determinants are still found to be important in explaining the wage differences of men and women ( Boll et al., 2017 ). Nonetheless, income differences of men and women can still be found even with the same investments in human capital. The reason for this could be the occupational discrimination of women ( Brynin and Perales, 2016 ; Achatz et al., 2005 ; Lips, 2013 ). Therefore, the occupational positions can be associated as a relevant factor of the GPG.

1.2.2 Life Course Approach

Besides economic theories, there are other theoretical approaches of explaining the GPG. One of them focusses on the accumulation of disadvantages over the life course: the ‘cumulative advantage/disadvantage theory’ by Dannefer (2003) . It also involves social inequalities which can expand over time. The employment histories of men and women evolve over their working lives and during different career stages, advantages and disadvantages can accumulate. First, this life course perspective considers and underlines the dynamic approach of how factors shape each individual life course. Secondly, it can contribute to explain the different income trajectories of men and women over their working lives ( Doren and Lin, 2019 ; Dannefer, 2003 ; Härkönen et al., 2016 ; Manzoni et al., 2014 ; Barone and Schizzerotto, 2011 ).

The importance of the life course perspective was underlined by some earlier studies. They demonstrated that certain conditions in adolescence or early work-life affected future careers of men and women. Visser et al. (2016) found evidence for an accumulation of disadvantages in the labor market over working life, in particular for the lower educated. The cohort study SHARE had assessed economic and social changes over the life course in numerous European countries in several publications ( Börsch-Supan et al., 2013 ). Overall, education and vocational training, occupational positions and income illustrate parts of the social structure which in turn can demonstrate gender inequality in the labor market ( Boll and Leppin, 2015 ; Hasselhorn, 2020 ; Du Prel et al., 2019 ). Moreover, family events and labor market processes repeatedly affect one another over the life course. The work-family trajectories have consequences on employment outcomes such as earnings ( Aisenbrey and Fasang, 2017 ; Jalovaara and Fasang, 2019 ). Furthermore, the income differences of men and women are not steady but tend to be lower at the beginning of employment and increase with age ( Goldin, 2014 ; Eurostat, 2021a ). Therefore, careers should not be analyzed in a single snapshot, but with a more appropriate life course approach that takes into account factors that influences the wages of men and women over time.

1.3 Aim and Hypotheses

The aim of the present study is to examine income trajectories and to investigate the income differences of men and women over their life course. We are interested in how human capital determinants, occupational positions and the accumulation of disadvantages over time contribute to the explanation of the GPG from a life course perspective.

Focusing on older German employees, our study includes 24 years of their careers and considers possible cumulative disadvantages of women in the labor market compared to those of men. In contrast to Polachek (1981) , who analyzed the GPG as a unit over lifetime, we used a life course approach in regard to the theory of cumulative disadvantages of Dannefer (2003) . Accordingly, we analyze explaining factors of the GPG not only in a single snapshot but over the working careers of men and women. Life course data based on register data and characteristics of employment biographies with information on a daily basis are two additional important and valuable advantages of our study. Existing studies rarely have this information in the form of life course data and when they do, the data is either self-reported and retrospective including possible recall bias, or based on register data which was only collected on a yearly basis. We expect to find differences in the income of men and women over a period of time with overall higher, and more increasing earnings of men than of women.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The differences of income trajectories throughout working life is expected to demonstrate more income over time among men than among women.

Education and vocational training, and work experience are human capital determinants. They have influence on the earnings of men and women. Although previous research estimated additional important factors contributing to the GPG, human capital capabilities continue to be relevant in explaining the wage differences of men and women ( Blau and Kahn, 2007 ; Boll et al., 2017 ). In our life course approach, we control for human capital determinants due to the information about education and vocational training, and work experience via the amount of working time (full-/part-time) for each year. We expect to find a strong influence of both determinants on the wages of men and women in Germany.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The income differences between men and women can be explained by determinants of the human capital model.

Previous research found out that factors such as occupational status had an impact on the income differences of men and women ( Blau and Kahn, 2007 ; Boll et al., 2017 ). For a better understanding and explanation of the GPG, gender differences regarding occupational positions must be included to human capital determinants ( Boll et al., 2017 ). We assume that men and women can be found in different occupations, measured via occupational status, and these explain a substantial part of the wage differences between men and women.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): The occupational status of men and women can contribute to the explanation of the GPG.

The life-course approach acknowledges time as an important influence on the wages of men and women. Income differences of men and women can change over time and career stages, while the GPG was found to be lower at the beginning of the employment career and widened with age ( Goldin, 2014 ). Hence, the earning differences between men and women tend to be higher for older employees ( Eurostat, 2021a ; Federal Statistical Office, 2016 ). To account for the influence of age, we additionally included the age of each person in our analysis. Another factor that changes over time and contribute to explain the GPG is part-time work. In general, part-time work result in a disadvantage in pay compared to full-time employment ( Ponthieux and Meurs, 2015 ). However, explanations of the GPG due to different amount of part-time work need to include a special form of part-time work: marginal work. Marginal employment conditions are characterized by low wages and high job insecurities. Also discontinuous employment due to unemployment are characterized by job insecurities and affect the low-paid sector – therefore mainly women ( Botsch, 2015 ). Besides the human capital determinants and occupational positions as important factors explaining the GPG, the region of employment influences the wages of men and women and can also change over the career stages. Evidence from the Federal Statistical Office of Germany in 2014 noticed a divergence of the GPG trend in the formerly separated parts of Germany. The GPG among employees was wider in the Western part (24%) compared to the Eastern part of Germany, where it was found to be 9% ( Federal Statistical Office, 2016 ). Therefore, to examine income differences, the amount of less advantaged employment such as marginal work or periods of unemployment throughout the careers of men and women needs to be considered, as well as the region of employment and the age of a person.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Factors of the living environment such as regional factors, and social disadvantage work conditions such as marginal work or unemployment, contribute to the income difference between men and women.

Our study about the GPG in Germany adds to earlier research in different ways. First, the accumulation of inequalities over the life course of men and women is known, but only few studies exist that focus on income through life course approach. We can analyze factors that influence the GPG over the careers of men and women due to the availability of social security data with daily information of each person. Besides the wages of men and women, the data additionally contains time-varying information about occupational status, working time and unemployment breaks. Therefore, we use longitudinal data of the German baby-boomers which allow us to measure changes of factors explaining the GPG over time. Second, a relevant contribution of our study is that we can consider different factors contributing to the explanation of the GPG through a life course perspective. The few studies focusing on the GPG over life course included either only determinants of the human capital model ( Joshi et al., 2020 ) or factors of occupational careers ( Moore, 2018 ). Some research included both aspects but had other disadvantages, such as Monti et al. (2020) , who could not analyze temporal evolution of the GPG with the data available. Moreover, previous research on the GPG in Germany could not trace vertical occupational segregation due to missing information of part-time workers, included only data of West Germany and used merely accumulated earnings over time ( Boll et al., 2017 ). Nonetheless, previous research demonstrated the need of analyzing the GPG via life course approach with which the accumulation of advantages and disadvantages for both, men and women, can be considered. Third, due to the usage of a multilevel framework we can examine income trajectories simultaneously at an individual and at a time-related level. Moreover, the influences of time-invariant and time-varying factors can be analyzed regarding differences in earnings of men and women. Hence, the multilevel approach examines income changes between and also within individuals. Furthermore, it acknowledges the importance of the life course perspective with including time as a factor in the model. A recent study also used growth curve modelling to explain gender inequality in the US. However, gender inequality measured through gender earnings was analyzed only across education and race without considering other variables explaining the GPG ( Doren and Lin, 2019 ). To our knowledge, there exists no research on the GPG that covers several essential determinants, hence we aim to fill those research gaps with our study.

2 Materials and Methods

The data were obtained from the cohort study lidA (living at work). The lidA sample includes two cohorts of employees (born in 1959 and in 1965) and was drawn randomly from social security data. LidA combines two major sources of information – register data of social insurance and questionnaire data derived from a survey. The survey was conducted in two waves, 2011 (t 0 ) and 2014 (t 1 ) ( Hasselhorn et al., 2014 ). The ethics commission of the University of Wuppertal approved the study.

In Germany, the social insurance system assists people in case of an emergency such as unemployment, illness, retirement, or nursing care. Employees have to make a contribution to the system depending on their income – except of civil servants or self-employed ( Federal Agency for Civic Education, 2021 ). In our analyses, we included men and women in Germany who participated in the baseline (2011) and in the follow-up (2014), were employed during both waves and subjected to social security contributions. We only included persons who agreed via written consent to the linkage of the survey data to their social security data. Thus, our sample for analysis included 3,338 individuals ( Figure 1 ).

Decision tree – inclusion and exclusion criteria in the sample for analysis.

2.2 Measurements

The social security data of the Institute for Employment Research of the German Federal Employment Agency is based on employers’ reports. The so-called “Integrated Employment Biographies” (IEB) or register data comprises information about individual employment; that is, type of employment, occupational status, episodes of unemployment and income with information about age, gender and education and vocational training. The IEB data are retrieved from employers’ yearly reports submitted to the social security authority ( Hasselhorn et al., 2014 ). The information of the register data was available on a daily basis and contained yearly information from 1993 to 2017 for each person. However, the IEB data contain missing details, especially regarding information that is not directly relevant for social security data and therefore, not of the highest priority for employers’ reports. This is particularly true for data on gender and education and vocational training. As our sample participants consented to the linkage of IEB with questionnaire data, we were able to impute the missing information on these variables with the help of the survey data. All time-varying information in the IEB is coded to the day. Our data have a multilevel structure with time of measurements (Level 1) being nested within individuals (Level 2) and defined as follows.

2.2.1 Level 1 Variables

In our analysis the variable time was based on information about the year of measurement. The starting point represents 1993 and was coded with zero. The outcome variable income was calculated from the IEB data as nominal wages in Euros (€). As time-varying variable, it can be defined as the average daily income per year of each person whose work contributes to social security and/or marginal employment. Information about the work experience due to working time was available for jobs that require social security contribution. To draw this information from the IEB data, the time-varying variable working time was computed with three different types: full- and part-time, part-time, and full-time. The data on occupational status were based on the International Standard of Classification of Occupations 2008 (ISCO-08). This time-varying variable contained information on the occupational status of each job that a person has held over the years. For the multilevel analysis, ISCO-08 was transformed from the German classification KldB 2010 (classification of occupations 2010) of the register data. ISCO-08 is structured according to the skill level and specialization of jobs, which are grouped into four hierarchical levels. Occupational status in our study was defined by the 10 major groups (level one of the classifications ISCO-08), without the group of armed forces who did not appear in our data. Therefore, the nine groups were analyzed: elementary occupations; plant and machine operators and assemblers; craft and related trades workers; skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers; services and sales workers; clerical support workers; technicians and associate professionals; professionals; and managers ( International Labour Office, 2012 ). Moreover, information about the number of episodes of marginal work could also be drawn from the register data. Marginal work was defined due to having at least one marginal employment per year. The time periods (episodes) of every marginal employment were counted and added up yearly. Furthermore, the duration of unemployment as time-varying variable was calculated due to information of the register data about the days of unemployment per year. In the register data unemployment is defined as being unemployed or unable to work for up to 42 days, excluding those with sickness absence benefits or disability pensions. The IEB data also provided information on the region of employment, which represents the area in which a company is located (East Germany and West Germany). This time-varying variable was available for each person over the years. A description of the Level 1 characteristics of our sample is provided in Table 2 using the last available information (2017) from the IEB data.

Characteristics of Level 1 variables a for men (n = 1,552) and women (n = 1,786).

M mean; SD standard deviation.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

2.2.2 Level 2 Variables

Information about the time-invariant variable education and vocational training was assessed from the survey data in 2011 (baseline). Education and vocational achievements of the sample were grouped in: low, intermediate and high education and vocational training (see Supplementary Table S1 ). The time-invariant variable gender had missing values in the register data. Therefore, we imputed the missing data using information of the survey data. The variable was coded 0 = female and 1 = male. Also based on the survey data, we included the time-invariant variable year of birth with measurements of 1959 and 1965 in the analysis. The characteristics of the Level 2 variables are displayed in Table 1 .

Characteristics of the Level 2 variables a for men (n = 1,552) and women (n = 1,786).

2.3 Statistical Analysis

The characteristics of our sample are displayed in Table 1 and Table 2 . Statistical analyses were performed using either Cramer’s V or by unpaired two sample t -test for numeric variables. Regarding the multilevel analysis, we used a so-called growth curve analysis. It demonstrates a multilevel approach for longitudinal data that model growth or decline over time. For this purpose, all daily information in the IEB were transformed into data on a yearly basis. Level 1 (year of measurements) represents the intraindividual change with time-varying variables. Interindividual changes are determined with time-invariant variables on Level 2 (individuals). Therefore, time of measurements predictors was nested within individuals. We applied a random intercept and slope model, which assumed variations in intercept and slope of individuals over time ( Singer and Willett, 2003 ; Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal, 2012 ; Hosoya et al., 2014 ). Besides the Level 1 and Level 2 predictors, the cross-level interaction of gender*time interaction was constituted to analyze differences in income slopes of men and women over time ( Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal, 2012 ).

Level 1 of the two-level growth model is presented below ( Eq. (1) ). y i j measures the income trajectory y for individual i at time j . True initial income for each person is represented with β 0 i . The slope of the individual change trajectory demonstrates β i j . T I M E i j stands for the measure of assessment at time j for individual i (Level 1 predictor). The residual or random error, specific to time and the individual is demonstrated by ε i j .

Eq. 2 and 3 represent the submodels of the Level 2. Eq. 2 defines the intercept γ 00 for individual i with the intercept of z i (illustrating a Level 2 predictor) and residual in the intercept v 0 i . The slope at Level 2 is represented in Eq. 3 with γ 10 and the slope error v 1 i . The effect γ 11 provides information on the extent to which the effect of the Level 1 predictor ( T I M E i j ) varies depending on the Level 2 predictor ( z i ).

To test our hypotheses, we calculated the influence of different variables with adjusting various predictors stepwise into the multilevel analysis. First, we estimated an unconditional means model which describes the outcome variation only and not its change over time (model 1). The next preliminary step was calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of this model 1. It identifies and partitions the two components: within- and between-person variance. The ICC estimates the proportion of total variation of the outcome y that lies between persons ( Singer and Willett, 2003 ). In the next model (model 2), we calculated an unconditional growth curve model which included time as predictor on Level 1. In model 3, the GCA was controlled for gender and time as well as the interaction of both variables. Model 4 was additionally adjusted for human capital determinant: education and vocational training, and working time. The GCA of model 5 was controlled for occupational status. The last model included year of birth, number of episodes of marginal work, duration of unemployment and region of employment (model 6 – fully adjusted model).

In Table 5 , the indices of the Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) were used to compare models and explore the best model fit ( Singer and Willett, 2003 ; Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal, 2012 ). The statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS 25.

Goodness-of-fit statistics of the GCA.

AIC Akaike’s Information Criterion.

3.1 Descriptive

Characteristics of Level 2 variables stratified by gender are displayed in Table 1 . 1,552 men and 1,786 women were included in the analyses. It is observed that women significantly differ from men in education and vocational training. Women were less likely than men to have both low and high levels of education and vocational training.

The characteristics of Level 1 variable are represented in Table 2 . Men and women differ significantly in their occupational positions. Also, men had a higher average daily income than women. Part-time jobs are more likely among women as compared to men, who are more likely to be represented in full-time jobs. Moreover, the numbers of episodes of marginal work differ significantly between men and women.

Figure 2 displays the income trajectories over the observation period (1993–2017) among men and women. In 24 years, average daily income per year increased for both. However, men have a higher average income over their life course than women. Over time, a steeper growth of the average daily income per year can be observed for men, compared to the income development of women.

Income trajectories of men and women.

3.2 Growth Curve Analysis

Results of the multilevel analyses with average daily income per year as dependent variable concerning H1 are presented in Table 3 . The ICC of the unconditional means model (model 1) demonstrates that 74% of the total variability in income can be attributed to differences between persons and 26% to the differences within persons. Adding time as a predictor in the multilevel analysis (model 2), the variance components on Level 1 become smaller. Concluding that time accounts for 68% (from 607.34 to 197.12) of the within-person variance in average income. On Level 2, time explains 40% of the variance between persons (interindividual). However, there can be still found significant unexplained results in both levels which suggests that predictors on both levels should be further included. The GCA in model 3 was adjusted for gender (with women as reference group) and the interaction gender*time. The results show a significant effect of gender on the average income over time. The starting place (intercept) lies at 41.74€ with an incremental growth per year of 1.76€. However, regarding women as reference group, men have a higher average income. The significant interaction term also indicates different income development of men and women over time – with men having higher average income trajectory than women. As expected, no relevant change can be found in the within-person variance due to the adding of the Level 2 variable: gender. The variance on Level 2, however, become less concluding that gender accounts for 26% of the variance between persons. Overall, we can verify H1 with these results.

Growth curve models 1 to 3: Estimates of average daily income per year.

L1 = Level 1; L2 = Level 2.

Results of the GCA with average daily income per year as the dependent variable controlled by determinants of the human capital model are presented in Table 4 (model 4). In addition to the multilevel analysis of model 3, model 4 is also adjusted for: education and vocational training, and working time. The results show that the average income is found to be significantly higher for full-time workers and higher educated. There is a social gradient for income regarding education and vocational training – with decreasing levels of education, the income also reduces. People who are working full-time have a higher average income than those who work part-time or full- and part-time. The effect of gender is found to be significant with less average income of women compared to men. Moreover, the income development of men and women over time is still significantly different, with more income growth over time for men than for women. The results of the variance components demonstrate that human capital determinants are explaining 16% of the variance within person and 25% of the variance between persons. However, on both levels there can be still found significant variance and additional variables need to be considered. Our hypothesis 2 can be partially confirmed.

Growth curve models 4 to 6: Estimates of average daily income per year.

Model 5 ( Table 4 ) embeds occupational status to the analysis to find out the contribution of the occupational positions on the earning differences of men and women. Significant differences in the daily average income for each occupational group can be identified. The reference group is represented with the highest occupational group ‘manager’. In nearly all other occupations, manager had the highest average income, except of ‘technicians and associate professionals’. Moreover, the effects of occupational status on income are significant for all ISCO groups except for professionals. However, compared to education and vocational training, occupational status trends are less clear, and a social gradient cannot be identified. The estimated of the fixed effect of gender persists and stays the same, concluding that the occupational position of a person could not influence the effect of gender on income. The increase of income over time can be still found to be significant higher for men than for women. Moreover, including the Level 1 variable, occupational position cannot explain a substantial part of the within-person variance. We can identify occupational positions as significant predictor of the income, but a relevant contribution to explain the GPG cannot be observed. Therefore, we cannot approve hypothesis 3.

The results of investigating the influence of factors of the living environment are presented in Table 4 (model 6). Those, who are born earlier (1959) are found to have a higher average daily income, compared to those born in 1965. Having at least one marginal employment per year influences the average daily income negatively, as does having more unemployed days. Furthermore, average income is influenced by the region of employment, being lower in East Germany than in West Germany. The estimate of gender become a little less, but the average income and the development of income over time still substantially differs between men and women. The factors of living environment account for 10% of the variance between persons. We can only partially accept hypothesis 4.

3.3 Goodness of Fit

Table 5 displays the goodness of fit statistics for the different models of the GCA. The AIC is computed to find the best model fit. Considering the different indices of AIC, model 6 has the best fit.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to examine the income differences of men and women over their life course. We investigated how different factors can explain the GPG over time. Even after extensive control for human capital determinants, occupational factors and various factors of the living environment, the effect of gender on the average daily income persisted. Moreover, the average income development was found to be higher for men compared to women.