- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Thomas Jefferson

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 22, 2022 | Original: October 29, 2009

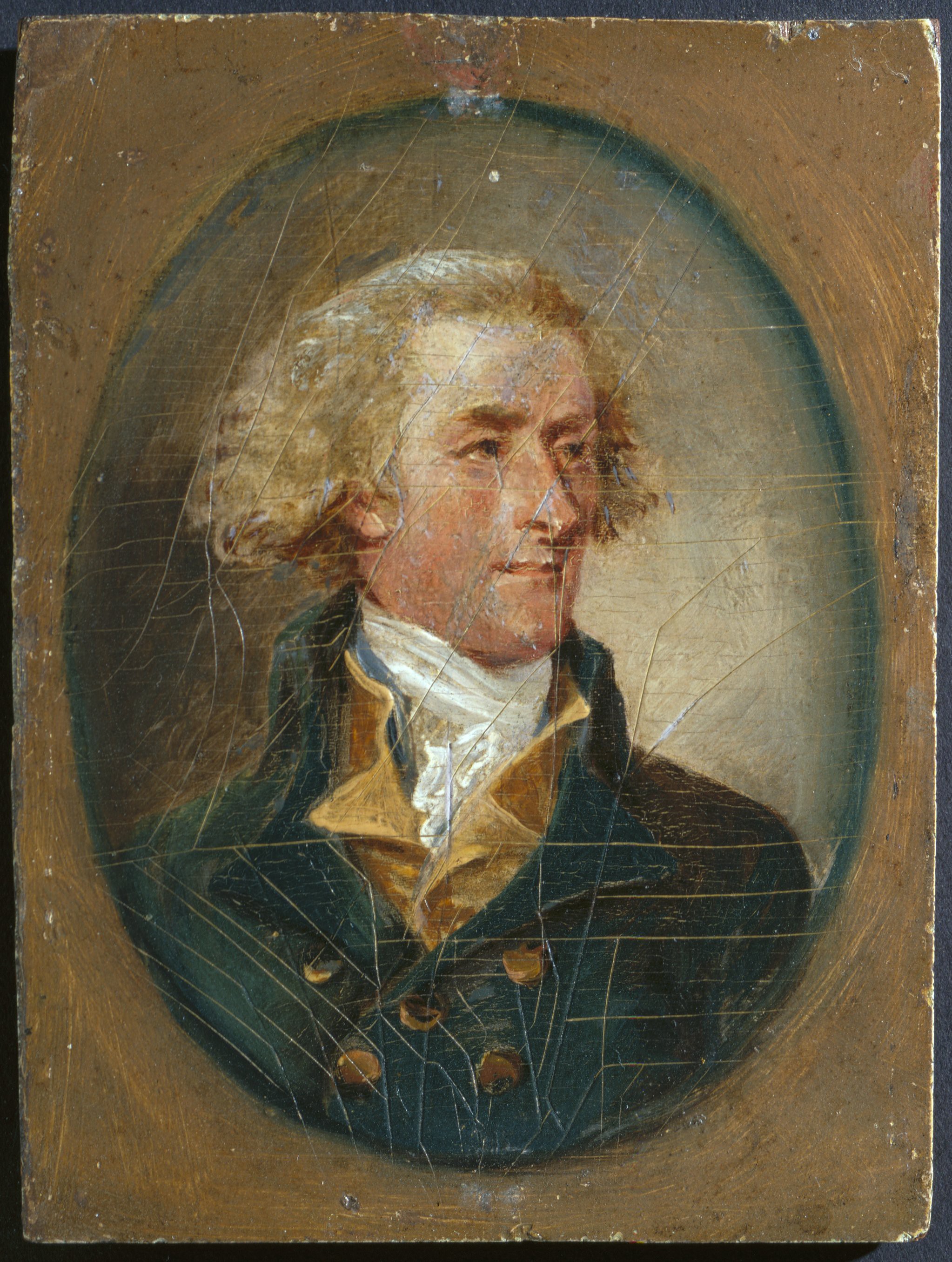

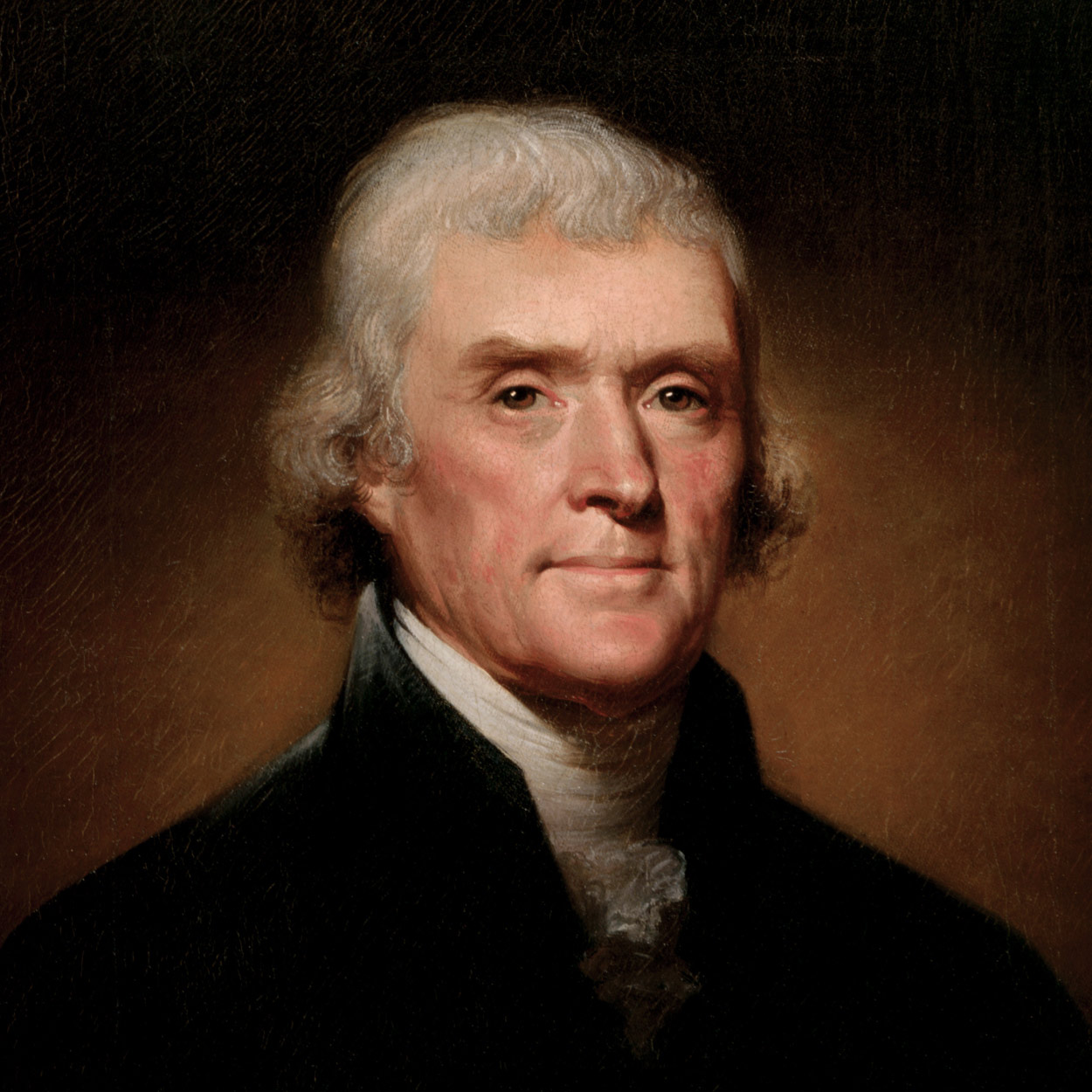

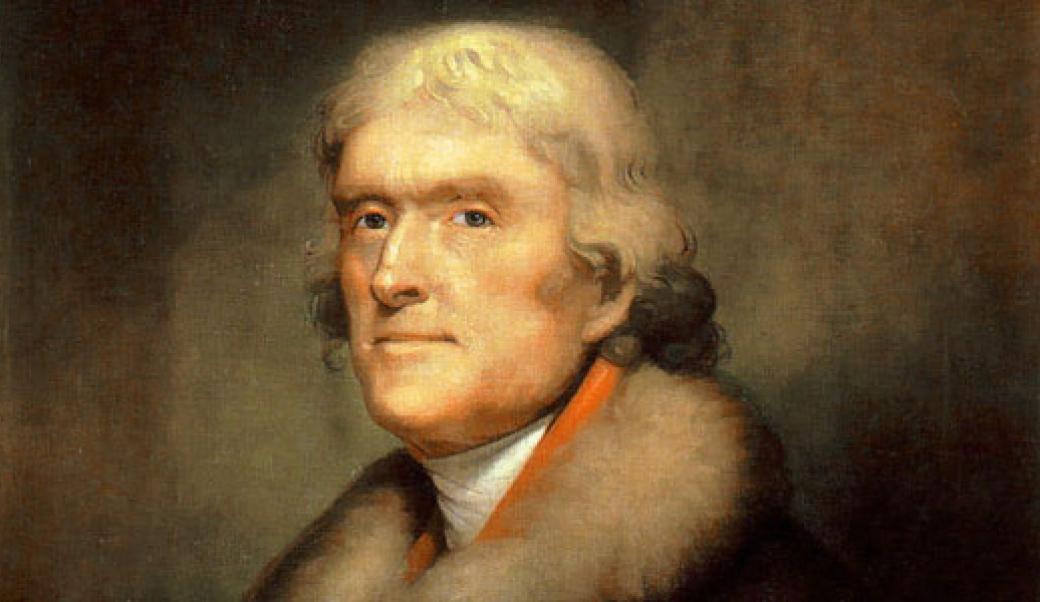

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), author of the Declaration of Independence and the third U.S. president, was a leading figure in America’s early development. During the American Revolutionary War (1775-83), Jefferson served in the Virginia legislature and the Continental Congress and was governor of Virginia. He later served as U.S. minister to France and U.S. secretary of state and was vice president under John Adams (1735-1826).

Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican who thought the national government should have a limited role in citizens’ lives, was elected president in 1800. During his two terms in office (1801-1809), the U.S. purchased the Louisiana Territory and Lewis and Clark explored the vast new acquisition. Although Jefferson promoted individual liberty, he also enslaved over six hundred people throughout his life. After leaving office, he retired to his Virginia plantation, Monticello, and helped found the University of Virginia.

Thomas Jefferson’s Early Years

Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743, at Shadwell, a plantation on a large tract of land near present-day Charlottesville, Virginia . His father, Peter Jefferson (1707/08-57), was a successful planter and surveyor and his mother, Jane Randolph Jefferson (1720-76), came from a prominent Virginia family. Thomas was their third child and eldest son; he had six sisters and one surviving brother.

Did you know? In 1815, Jefferson sold his 6,700-volume personal library to Congress for $23,950 to replace books lost when the British burned the U.S. Capitol, which housed the Library of Congress, during the War of 1812. Jefferson's books formed the foundation of the rebuilt Library of Congress's collections.

In 1762, Jefferson graduated from the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, where he reportedly enjoyed studying for 15 hours, then practicing violin for several more hours on a daily basis. He went on to study law under the tutelage of respected Virginia attorney George Wythe (there were no official law schools in America at the time, and Wythe’s other pupils included future Chief Justice John Marshall and statesman Henry Clay ).

Jefferson began working as a lawyer in 1767. As a member of colonial Virginia’s House of Burgesses from 1769 to 1775, Jefferson, who was known for his reserved manner, gained recognition for penning a pamphlet, “A Summary View of the Rights of British America” (1774), which declared that the British Parliament had no right to exercise authority over the American colonies .

Marriage and Monticello

After his father died when Jefferson was a teen, the future president inherited the Shadwell property. In 1768, Jefferson began clearing a mountaintop on the land in preparation for the elegant brick mansion he would construct there called Monticello (“little mountain” in Italian). Jefferson, who had a keen interest in architecture and gardening, designed the home and its elaborate gardens himself.

Over the course of his life, he remodeled and expanded Monticello and filled it with art, fine furnishings and interesting gadgets and architectural details. He kept records of everything that happened at the 5,000-acre plantation, including daily weather reports, a gardening journal and notes about his slaves and animals.

On January 1, 1772, Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton (1748-82), a young widow. The couple moved to Monticello and eventually had six children; only two of their daughters—Martha (1772-1836) and Mary (1778-1804)—survived into adulthood. In 1782, Jefferson’s wife Martha died at age 33 following complications from childbirth. Jefferson was distraught and never remarried. However, it is believed he fathered more children with one of his enslaved women, Sally Hemings (1773-1835), who was also his wife’s half-sister .

Slavery was a contradictory issue in Jefferson’s life. Although he was an advocate for individual liberty and at one point promoted a plan for the gradual emancipation of slaves in America, he enslaved people throughout his life. Additionally, while he wrote in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal,” he believed African Americans were biologically inferior to whites and thought the two races could not coexist peacefully in freedom. Jefferson inherited some 175 enslaved people from his father and father-in-law and owned an estimated 600 slaves over the course of his life. He freed only a small number of them in his will; the majority were sold following his death.

Thomas Jefferson and the American Revolution

In 1775, with the American Revolutionary War recently underway, Jefferson was selected as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. Although not known as a great public speaker, he was a gifted writer and at age 33, was asked to draft the Declaration of Independence (before he began writing, Jefferson discussed the document’s contents with a five-member drafting committee that included John Adams and Benjamin Franklin ). The Declaration of Independence , which explained why the 13 colonies wanted to be free of British rule and also detailed the importance of individual rights and freedoms, was adopted on July 4, 1776.

In the fall of 1776, Jefferson resigned from the Continental Congress and was re-elected to the Virginia House of Delegates (formerly the House of Burgesses). He considered the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which he authored in the late 1770s and which Virginia lawmakers eventually passed in 1786, to be one of the significant achievements of his career. It was a forerunner to the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution , which protects people’s right to worship as they choose.

From 1779 to 1781, Jefferson served as governor of Virginia, and from 1783 to 1784, did a second stint in Congress (then officially known, since 1781, as the Congress of the Confederation). In 1785, he succeeded Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) as U.S. minister to France. Jefferson’s duties in Europe meant he could not attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787; however, he was kept informed of the proceedings to draft a new national constitution and later advocated for including a bill of rights and presidential term limits.

Jefferson's Path to the Presidency

After returning to America in the fall of 1789, Jefferson accepted an appointment from President George Washington (1732-99) to become the new nation’s first secretary of state. In this post, Jefferson clashed with U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1755/57-1804) over foreign policy and their differing interpretations of the U.S. Constitution. In the early 1790s, Jefferson, who favored strong state and local government, co-founded the Democratic-Republican Party to oppose Hamilton’s Federalist Party , which advocated for a strong national government with broad powers over the economy.

In the presidential election of 1796, Jefferson ran against John Adams and received the second-highest amount of votes, which, according to the law at the time, made him vice president.

Jefferson ran against Adams again in the presidential election of 1800, which turned into a bitter battle between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Jefferson defeated Adams; however, due to a flaw in the electoral system, Jefferson tied with fellow Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr (1756-1836). The House of Representatives broke the tie and voted Jefferson into office. In order to avoid a repeat of this situation, Congress proposed the Twelfth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which required separate voting for president and vice president. The amendment was ratified in 1804.

Jefferson Becomes Third U.S. President

Jefferson was sworn into office on March 4, 1801; he was the first presidential inauguration held in Washington, D.C. ( George Washington was inaugurated in New York in 1789; in 1793, he was sworn into office in Philadelphia, as was his successor, John Adams, in 1797.) Instead of riding in a horse-drawn carriage, Jefferson broke with tradition and walked to and from the ceremony.

One of the most significant achievements of Jefferson’s first administration was the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France for $15 million in 1803. At more than 820,000 square miles, the Louisiana Purchase (which included lands extending between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains and the Gulf of Mexico to present-day Canada) effectively doubled the size of the United States. Jefferson then commissioned explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore the uncharted land, plus the area beyond, out to the Pacific Ocean. (At the time, most Americans lived within 50 miles of the Atlantic Ocean.) Lewis and Clark’s expedition , known today as the Corps of Discovery, lasted from 1804 to 1806 and provided valuable information about the geography, American Indian tribes and animal and plant life of the western part of the continent.

In 1804, Jefferson ran for re-election and defeated Federalist candidate Charles Pinckney (1746-1825) of South Carolina with more than 70 percent of the popular vote and an electoral count of 162-14. During his second term, Jefferson focused on trying to keep America out of Europe’s Napoleonic Wars (1803-15). However, after Great Britain and France, who were at war, both began harassing American merchant ships, Jefferson implemented the Embargo Act of 1807.

The act, which closed U.S. ports to foreign trade, proved unpopular with Americans and hurt the U.S. economy. It was repealed in 1809 and, despite the president’s attempts to maintain neutrality, the U.S. ended up going to war against Britain in the War of 1812. Jefferson chose not to run for a third term in 1808 and was succeeded in office by James Madison (1751-1836), a fellow Virginian and former U.S. secretary of state.

Thomas Jefferson’s Later Years and Death

Jefferson spent his post-presidential years at Monticello, where he continued to pursue his many interests, including architecture, music, reading and gardening. He also helped found the University of Virginia, which held its first classes in 1825. Jefferson was involved with designing the school’s buildings and curriculum and ensured that unlike other American colleges at the time, the school had no religious affiliation or religious requirements for its students.

Jefferson died at age 83 at Monticello on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Coincidentally, John Adams, Jefferson’s friend, former rival and fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence, died the same day . Jefferson was buried at Monticello. However, due to the significant debt the former president had accumulated during his life, his mansion, furnishing and enslaved people were sold at auction following his death. Monticello was eventually acquired by a nonprofit organization, which opened it to the public in 1954.

Jefferson remains an American icon. His face appears on the U.S. nickel and is carved into stone at Mount Rushmore . The Jefferson Memorial, near the National Mall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated on April 13, 1943, the 200th anniversary of Jefferson’s birth.

HISTORY Vault: U.S. Presidents

Stream U.S. Presidents documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Books | New Thomas Jefferson biography captures complex…

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Music and Concerts

- The Theater Loop

- TV and Streaming

Things To Do

Books | new thomas jefferson biography captures complex president in his place and time.

That was April 1962, and that was how Jefferson was then viewed: as a man of astonishingly varied and sophisticated knowledge and accomplishments, a Founding Father to rank beside Washington and Franklin. Then, a dozen years later, came Fawn Brodie’s “Jefferson: An Intimate History,” an inquiry into Jefferson’s relations with his slaves, most specifically the possibility of sexual relations with the house servant Sally Hemings. It sold well for a work of ostensibly serious history, though it aroused passionate indignation among Jefferson loyalists in Virginia and elsewhere, and it set Jefferson on the downhill course he has followed ever since. As John B. Boles says at the outset of this magisterial biography:

“Jefferson’s complexity renders him easy to caricature in popular culture. Particularly in recent years, Jefferson, long the hero of small d as well as capital D democrats, has seen his reputation wane due to his views on race, the revelation of his relationship with Sally Hemings, and his failure to free his own slaves. Once lauded as the champion of the little man, today he is vilified as a hypocritical slave owner, professing a love of liberty while quietly driving his own slaves to labor harder in his pursuit of luxury. Surely an interpretive middle ground is possible, if not necessary. If we hope to understand the enigma that is Thomas Jefferson, we must view him holistically and within the rich context of his time and place. This biography aims to provide that perspective.”

To say that it does so is massive understatement. “Jefferson: Architect of American Liberty” is perhaps the finest one-volume biography of an American president. Boles, a professor of history at Rice University, has spent many years studying Jefferson’s native American South in all its mysteries, contradictions, follies and outrages, as well as its unique contributions to the national culture and literature. This biography is the culmination of a long, distinguished career. I admire it so passionately that, almost 2 1/2 years into a happy retirement, I had no choice except to violate my pledge never again to write another book review.

To his study of this deeply controversial man, Boles brings an ample supply of what has been so lamentably missing in the discussion over the past half-century: a calm insistence on separating truth (so far as we can know it) from rumor and invective, and a refusal to judge a man who lived more than two centuries ago by the moral, ethical and political standards of today. Boles admires Jefferson and maintains a sympathetic attitude toward him through this long, immensely satisfying narrative, but he does not flinch when Jefferson’s behavior and attitudes seem, according to 21st-century standards, offensive at worst, inexplicable at best.

Because the focus in recent years has been almost entirely on Jefferson’s attitudes toward slavery and his actions regarding the several hundred slaves who fell under his ownership, it is important to recall that there was vastly more to his long life than this. In Boles’ “full-scale biography,” Jefferson is presented to us “in all his guises: politician, diplomat, party leader, executive; architect, musician, oenophile, gourmand, traveler; inventor, historian, political theorist; land owner, farmer, slaveholder; and son, father, grandfather.” Without smothering the reader under mountains of detail, Boles briskly but authoritatively takes Jefferson from his birth in Virginia in 1743 to his death, at home in his beloved Monticello, on the Fourth of July, 1826, several hours before the death in Massachusetts of his old friend and occasional rival, John Adams, that other great Founding Father.

As Boles notes, the world into which Jefferson was born was so different from our own that we are hard-pressed to imagine it, yet it was out of this distant world that our own eventually emerged, and Jefferson was at the very center as the transformation from colony to nation got under way. He wrote the immortal Declaration of Independence, which gave voice to the convictions and hopes that impelled his fellow colonists into revolution. At the end of his life, he said the Declaration was one of his three singular accomplishments, the others being the enactment of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) and the establishment of the University of Virginia a couple of years before his death.

He represented the new nation in Paris from 1784 to 1790, and while he was there delighted in and learned from the varied aspects of that city, whether musical or literary or architectural. In Philadelphia and New York, from 1790 to 1801, he participated in the formation of the new government and served a term as John Adams’ vice president, spending much of that term at Monticello, just as Adams spent much of his term at his Massachusetts home. He then sought and won the presidency in February 1801 in a breathtakingly close vote in the House of Representatives.

The accomplishments of his presidency are well known, most notably the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the Lewis and Clark expedition to the far West, though his second term was less successful than his first. He lived for more than a decade and a half after it ended, and while he continued to be active in the public lives of his nation and state, he found his greatest pleasures in Monticello and within the bonds of the family to which he was utterly devoted. His wife, Martha, had died in 1782, pleading with him on her deathbed not to marry again, a request that he honored willingly but one that probably had much to do with his later escape into the arms of Hemings.

Thanks largely to the diligent research of Annette Gordon-Reed and the two books that emerged from it, “Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings” (1997) and “The Hemingses of Monticello” (2008), we now know almost certainly as much as we ever will about this essentially mysterious connection. We do know that Hemings “gave birth to five children,” that Jefferson “was demonstrably present at Monticello nine months prior to each of these births” and that one of her children bore an almost uncanny resemblance to Jefferson. Gordon-Reed “argues that Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, as unlikely as it might seem, probably had genuine mutual affection,” which if true can only leave us all the more puzzled by “his failure to emancipate his own slaves or work actively to end slavery completely.” Boles writes:

“Activists in Jefferson’s time … much less the abolitionists who emerged soon after his death, could not accept such a patient approach; nor can modern readers. Jefferson’s willingness to wait tells us a great deal about his character and also about his era, his race, and his class. As a wealthy white man, he saw little need for urgency; he believed, rather, that in God’s good time, emancipation would somehow be effected. In no other aspect of his life does Jefferson seem more distant from us or more disappointing.”

Disappointing, to be sure, but also understandable. He was a creature of his own time, not of ours, and at the end of this superb, utterly riveting biography, Boles strikes exactly the right note. He describes the “simple obelisk” erected over Jefferson’s grave at Monticello and then says: “It was a simple marker for a man of vast accomplishments and complexities, the supreme spokesman of America’s promise. Ironically, today he is often found wanting for not practicing the principles he articulated best. Yet Jefferson, despite his limitations, more than anyone else was the intellectual architect of the nation’s highest ideals. He will always belong in the American pantheon.”

Yardley was the book critic of The Washington Post from 1981 to 2014.

“Jefferson: Architect of American Liberty” b y John B. Boles

Basic. 626 pp. $35

.galleries:after { content: ”; display: block; background-color: #144A7C; margin: 16px auto 0; height: 5px; width: 100px;

} .galleries:before { content: “More From Books”; display: block; font: 700 23px/25px Georgia,serif; text-align: center; color: #1e1e1e;

More in Books

Books | Biblioracle: In Reese’s Book Club vs. Read with Jenna, we pick a winner

Restaurants, Food and Drink | Hiking for hops: Chicago couple’s new book uses nature and beer to explore the city

Books | Biblioracle: Lydia Millet’s ‘We Loved It All’ is a beautiful and sad meditation on the world’s creatures

Arts | Coming to Chicago museums: SpaceX Dragon at MSI, Georgia O’Keeffe at Art Institute

Trending nationally.

- Cambridge couple stranded in Brazil with premature newborn say they are stuck in ‘bureaucratic morass’

- Scottie Scheffler arrested at PGA Championship for traffic violation, returns to course hours later

- Ben Affleck spotted staying at separate home amid Jennifer Lopez split rumors

- ABC’s ‘Golden Bachelorette’ is 61-year-old Maryland grandmother

- Preakness 2024: From Mystik Dan to Uncle Heavy, get to know the eight horses in the field

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello

Thomas jefferson, thomas jefferson biography.

(Born April 13, 1743, at Shadwell, Virginia; died July 4, 1826, Monticello)

Lawyer. Father. Scientist. Writer. Revolutionary. Governor. Vice-president. President. Philosopher. Architect. Slave Owner.

Many words describe Thomas Jefferson. He is best remembered as the person who wrote the Declaration of Independence and third president of the United States.

Early Life and Monticello

Jefferson was born April 13, 1743, on his father’s plantation of Shadwell located along the Rivanna River in the Piedmont region of central Virginia at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. 1 His father Peter Jefferson was a successful planter and surveyor and his mother Jane Randolph a member of one of Virginia’s most distinguished families. When Jefferson was fourteen, his father died, and he inherited a sizeable estate of approximately 5,000 acres. That inheritance included the house at Shadwell, but Jefferson dreamed of living on a mountain. 2

Shadwell, where it all began

Have you ever wondered where our third president was born? Learn about his early life, as presented by Research Archaeologist Derek Wheeler.

In 1768 he contracted for the clearing of a 250 feet square site on the topmost point of the 868-foot mountain that rose above Shadwell and where he played as a boy. 3 He would name this mountain Monticello, and the house that he would build and rebuild over a forty-year period took on this name as well. He would later refer to this ongoing project, the home that he loved, as “my essay in Architecture.” 4 The following year, after preparing the site, he began construction of a small brick structure that would consist of a single room with a walk-out basement kitchen and workroom below. This would eventually be referred to as the South Pavilion and was where he lived first alone and then with his bride, Martha Wayles Skelton, following their marriage in January 1772.

Unfortunately, Martha would never see the completion of Monticello; she died in the tenth year of their marriage, and Jefferson lost “the cherished companion of my life.” Their marriage produced six children but only two survived into adulthood, Martha (known as Patsy) and Mary (known as Maria or Polly). 5

Martha Wayles Jefferson, A Vivid Personality

In this short video, hear how Martha W.S. Jefferson stands out as a vivid personality in the recollections of those who knew and remembered her.

Along with the land Jefferson inherited slaves from his father and even more slaves from his father-in-law, John Wayles ; he also bought and sold enslaved people. In a typical year, he owned about 200, almost half of them under the age of sixteen. About eighty of these enslaved individuals lived at Monticello; the others lived on his adjacent Albemarle County farms, and on his Poplar Forest estate in Bedford County, Virginia. Over the course of his life, he owned over 600 enslaved people. These men, women and children were integral to the running of his farms and building and maintaining his home at Monticello. Some were given training in various trades, others worked the fields, and some worked inside the main house.

Many of the enslaved house servants were members of the Hemings family. Elizabeth Hemings and her children were a part of the Wayles estate and tradition says that John Wayles was the father of six of Hemings’s children and, thus, they were the half-brothers and sisters of Jefferson’s wife Martha. Jefferson gave the Hemingses special positions, and the only slaves Jefferson freed in his lifetime and in his will were all Hemingses, giving credence to the oral history. Years after his wife’s death, Jefferson fathered at least six of Sally Hemings’s children. Four survived to adulthood and are mentioned in Jefferson’s plantation records. Their daughter Harriet and eldest son Beverly were allowed to leave Monticello during Jefferson’s lifetime and the two youngest sons, Madison and Eston , were freed in Jefferson’s will.

Videos and podcasts about Jefferson

Learn more about Jefferson's life, career, and legacy in this gallery of recorded livestreams, podcasts, and videos.

Education and Professional Life

After a two-year course of study at the College of William and Mary that he began at age seventeen, Jefferson read the law for five years with Virginia’s prominent jurist, George Wythe, and recorded his first legal case in 1767. In two years he was elected to Virginia’s House of Burgesses (the legislature in colonial Virginia).

His first political work to gain broad acclaim was a 1774 draft of directions for Virginia’s delegation to the First Continental Congress, reprinted as a “Summary View of the Rights of British America.” Here he boldly reminded George III that, “he is no more than the chief officer of the people, appointed by the laws, and circumscribed with definite powers, to assist in working the great machine of government. . . .” Nevertheless, in his “Summary View” he maintained that it was not the wish of Virginia to separate from the mother country. 6 But two years later as a member of the Second Continental Congress and chosen to draft the Declaration of Independence , he put forward the colonies’ arguments for declaring themselves free and independent states. The Declaration has been regarded as a charter of American and universal liberties. The document proclaims that all men are equal in rights, regardless of birth, wealth, or status; that those rights are inherent in each human, a gift of the creator, not a gift of government, and that government is the servant and not the master of the people.

Jefferson recognized that the principles he included in the Declaration had not been fully realized and would remain a challenge across time, but his poetic vision continues to have a profound influence in the United States and around the world. Abraham Lincoln made just this point when he declared:

All honor to Jefferson – to the man who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, and so to embalm it there, that to-day and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of reappearing tyranny and oppression. 7

After Jefferson left Congress in 1776, he returned to Virginia and served in the legislature. In late 1776, as a member of the new House of Delegates of Virginia, he worked closely with James Madison. Their first collaboration, to end the religious establishment in Virginia, became a legislative battle which would culminate with the passage of Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786.

Elected governor from 1779 to 1781, he suffered an inquiry into his conduct during the British invasion of Virginia in his last year in office that, although the investigation was finally repudiated by the General Assembly, left him with a life-long pricklishness in the face of criticism and generated a life-long enmity toward Patrick Henry whom Jefferson blamed for the investigation. The investigation “inflicted a wound on my spirit which will only be cured by the all-healing grave” Jefferson told James Monroe. 8

During the brief private interval in his life following his governorship, Jefferson completed the one book which he authored, Notes on the State of Virginia . Several aspects of this work were highly controversial. With respect to slavery, in Notes Jefferson recognized the gross injustice of the institution – warning that because of slavery “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his Justice cannot sleep for ever.” But he also expressed racist views of blacks’ abilities; albeit he recognized that his views of their limitations might result from the degrading conditions to which they had been subjected for many years. With respect to religion, Jefferson’s Notes emphatically supported a broad religious freedom and opposed any establishment or linkage between church and state, famously insisting that “it does me no injury for my neighbour to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” 9

In 1784, he entered public service again, in France, first as trade commissioner and then as Benjamin Franklin's successor as U.S. minister. During this period, he avidly studied European culture, sending home to Monticello, books, seeds and plants, along with architectural drawings, artwork, furniture, scientific instruments, and information.

In 1790 he agreed to be the first secretary of state under the new Constitution in the administration of the first president, George Washington . His tenure was marked by his opposition to the policies of Alexander Hamilton which Jefferson believed both encouraged a larger and more powerful national government and were too pro-British.

In 1796, as the presidential candidate of the nascent Democratic-Republican Party, he became vice-president after losing to John Adams by three electoral votes. Four years later, he defeated Adams in another hotly contested election and became president, the first peaceful transfer of authority from one party to another in the history of the young nation.

Perhaps the most notable achievements of his first term were the purchase of the Louisiana Territory in 1803 and his support of the Lewis and Clark expedition . His second term, a time when he encountered more difficulties on both the domestic and foreign fronts, is most remembered for his efforts to maintain neutrality in the midst of the conflict between Britain and France. Unfortunately, his efforts did not avert a war with Britain in 1812 after he had left office and his friend and colleague, James Madison, had assumed the presidency.

Jefferson as President

More on Jefferson's two terms as America's third president.

During the last seventeen years of his life, Jefferson generally remained at Monticello, welcoming the many visitors who came to call upon the Sage. During this period, he sold his collection of books (almost 6500 volumes) to the government to form the nucleus of the Library of Congress before promptly beginning to purchase more volumes for his final library. Noting the irony, Jefferson famously told John Adams that “I cannot live without books.” 10

Jefferson embarked on his last great public service at the age of seventy-six with the founding of the University of Virginia . He spearheaded the legislative campaign for its charter, secured its location, designed its buildings, planned its curriculum, and served as the first rector.

Unfortunately, Jefferson’s retirement was clouded by debt. Like so many Virginia planters, he had contended with debts most of his adult life, but along with the constant fluctuations in the agricultural markets, he was never able to totally liquidate the sizeable debt attached to the inheritance from his father-in-law John Wayles. His finances worsened in retirement with the War of 1812 and the subsequent recession, headed by the Panic of 1819. He had felt compelled to sign on notes for a friend in 1818, who died insolvent two years later, leaving Jefferson with two $10,000 notes. This he labeled his coup de grâce, as his extensive land holdings in Virginia, with the deflated land prices, could no longer cover what he owed. He complained to James Madison that the economic crisis had “peopled the Western States” and “drew off bidders” for lands in Virginia and along the Atlantic seaboard. 11 Ironically, Jefferson’s greatest accomplishment during his presidency, the purchase of the port of New Orleans and the Louisiana Territory that opened the western migration, would contribute to his financial discomfort in his final years. 12

Jefferson's Three Greatest Achievements

A Monticello guide looks at the three contributions that Jefferson considered his greatest achievements.

Despite his debts, when he died just a few hours before his friend John Adams on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1826, he was optimistic as to the future of the republican experiment. Just ten days before his death, he had declined an invitation to the planned celebration in Washington but offered his assurance, “All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man.” 13

Jefferson wrote his own epitaph and designed the obelisk grave marker that was to bear three of his accomplishments and “not a word more:”

HERE WAS BURIED THOMAS JEFFERSON AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE OF THE STATUTE OF VIRGINIA FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM AND FATHER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA BORN APRIL 2, 1743 O.S. DIED JULY 4. 1826

He could have filled several markers had he chosen to list his other public offices: third president of the new United States, vice president, secretary of state, diplomatic minister, and congressman. For his home state of Virginia he served as governor and member of the House of Delegates and the House of Burgesses as well as filling various local offices — all tallied into almost five decades of public service. He also omitted his work as a lawyer, architect, writer, farmer, gentleman scientist, and life as patriarch of an extended family at Monticello, both white and black. He offered no particular explanation as to why only these three accomplishments should be recorded, but they were unique to Jefferson.

Other men would serve as U.S. president and hold the public offices he had filled, but only he was the primary draftsman of the Declaration of Independence and of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom , nor could others claim the position as the Father of the University of Virginia . More importantly, through these three accomplishments he had made an enormous contribution to the aspirations of a new America and to the dawning hopes of repressed people around the world. He had dedicated his life to meeting the challenges of his age: political freedom, religious freedom, and educational opportunity. While he knew that we would continue to face these challenges through time, he believed that America’s democratic values would become a beacon for the rest of the world. He never wavered from his belief in the American experiment.

I have no fear that the result of our experiment will be that men may be trusted to govern themselves. . . . Thomas Jefferson, 2 July 1787

He spent much of his life laying the groundwork to insure that the great experiment would continue.

Jefferson, Politics, and Citizenship

Timeline of jefferson's public service.

From pro bono law work to founding the University of Virginia, Jefferson's career was one of public service.

The Art of Citizenship

A hub of stories, quotes, videos, biographies, podcasts, and timelines on Jefferson and civics in America.

Articles in our Jefferson Encyclopedia

Jefferson's personal life, interests, and habits.

Jefferson's Community

The people in Jefferson's life.

Articles about Jefferson's political career and accomplishments.

Science and Exploration

Learn more about Jefferson's "tranquil pursuits of science" which he called his "supreme delight."

Information about Jefferson's religious beliefs and his promotion of religious freedom.

Reports some of Jefferson's documents, his correspondence, and his writing habits.

Jefferson in Legend

Anecdotes and stories, generally inaccurate, about Jefferson's life.

1. Jefferson was born April 2nd according to the Julian calendar then in use (“ old style ”), but when the Georgian calendar was adopted in 1752, his birthday became April 13th (“new style”).

2. Dumas Malone, Jefferson and His Time , 6 vols. (Boston: 1948-77). I:3-33; Appendix I, I:435-46.

3. Jefferson’s Memorandum Books , James A. Bear and Lucia Stanton, eds. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997). I: 76.

4. TJ to Benjamin Latrobe, 10 Oct. 1809, PTJR:RS, 1:595.

5. “Autobiography” in Jefferson’s Writings, PTJ 6:210.

6. PTJ 1:121.

7. Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Henry L. Pierce, et al ., April 6, 1859, John G. Nicolay and John Hay, eds., Abraham Lincoln: Complete Works (New York: Century Co., 1894): 533.

8. Jefferson to James Monroe, May 20, 1782, PTJ 6:185 (ftnt omitted).

9. Notes on the State of Virginia . Ed. by William Peden. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982.

10. Jefferson to John Adams, 15 June 1815, PTJR 8:522.

11. For coup de grâce and following quote, see TJ to James Madison 17 February 1826, Jefferson Writing, Merrill Peterson, ed. (Library of America, 1984), 1512-15.

12. For Jefferson’s retirement debt see, Herbert Sloan, Principle & Interest: Thomas Jefferson and the Problem of Debt (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995), 202-237; for notes signed in 1818, see p. 219.

13. TJ to Roger Weightman, 24 June 1826, Jefferson Writings , 1516-17.

ADDRESS: 931 Thomas Jefferson Parkway Charlottesville, VA 22902 GENERAL INFORMATION: (434) 984-9800

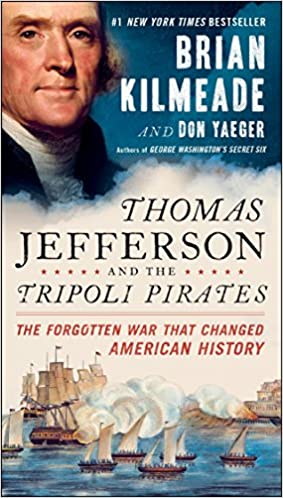

The Essentials: Five Books on Thomas Jefferson

A Jefferson expert provides a list of indispensable reads about the founding father

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino

Senior Editor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Thomas-Jefferson-books-631.jpg)

Historian Marc Leepson is the author of seven books, including Saving Monticello (2001), a comprehensive history of the house built by Thomas Jefferson and the hands it passed through since his death in 1826.

Here, Leepson provides a list of five must-reads for a better understanding of the author of the Declaration of Independence and the third president of the United States.

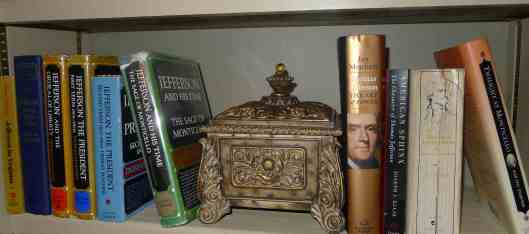

Jefferson and His Time , by Dumas Malone

This classic biography of Thomas Jefferson, written by one of the most renowned Jefferson scholars, was published in six volumes over 33 years. It consists of Jefferson the Virginian (1948), covering his childhood through his drafting of the Declaration of Independence; Jefferson and the Rights of Man (1951), about his years as a minister to France and secretary of state; Jefferson and the Ordeal of Liberty (1962), leading up through his presidential election; Jefferson the President: First Term, 1801-1805 (1970) and Jefferson the President: Second Term, 1805-1809 (1974); and The Sage of Monticello (1981), about the last 17 years of his life, as his priorities changed from politics to family, architecture and education. In 1975, author Dumas Malone won the Pulitzer Prize for history for the first five volumes.

From Leepson: Malone is a Jefferson partisan, but his scholarship is impeccable .

American Sphinx (1996), by Joseph J. Ellis

National Book Award winner Joseph J. Ellis’ newest book, First Family , takes on the relationship between Abigail and John Adams. But a decade and a half ago, the Mount Holyoke history professor made Thomas Jefferson—and his elusive, complicated and sometimes duplicitous nature—the subject of American Sphinx . “The best and worst of American history are inextricably entangled in Jefferson,” he wrote in the New York Times in 1997.

The book—one volume in length and written in layman’s terms—is perhaps a more digestible read than Malone’s series. “While I certainly hope my fellow scholars will read the book, and even find the interpretation fresh and the inevitable blunders few, the audience I had in my mind’s eye was that larger congregation of ordinary people with a general but genuine interest in Thomas Jefferson,” writes Ellis in the preface.

From Leepson: An insightful, readable look at Jefferson’s character .

Twilight at Monticello (2008), by Alan Pell Crawford

Alan Pell Crawford, a former political speechwriter and Congressional press secretary who now covers history and politics, pored over archives across the country, at one point holding a residential fellowship at the International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello, to research this book. And the digging paid off. He found documents and letters of Jefferson’s relatives and neighbors, some never before studied, and pieced them together into a narrative of the president’s twilight years. During this far from restful period, Jefferson experienced family and financial dramas, opposed slavery on principle and yet, with slaves working on his own plantation, did not actively push to abolish it, and founded the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

From Leepson: The best treatment by far of Jefferson’s life post-presidency (1809-26) .

The Jefferson Image in the American Mind (1960), by Merrill D. Peterson

“The most important thing in my education was my dissertation,” said Merrill D. Peterson in 2005, about his time studying at Harvard in the late 1940s. Instead of researching the president’s life, Peterson focused on his afterlife, studying the lasting impact he had on American thought.

The idea became the basis of his first book, The Jefferson Image in the American Mind , published in 1960. And the book, which won a Bancroft Prize for excellence in American history, established Peterson as a Jefferson scholar. After stints teaching at Brandeis University and Princeton, Peterson filled the big shoes of Jefferson biographer Dumas Malone as the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor of History at the University of Virginia. He wrote Jefferson and the New Nation , a 1970 biography of the president, among other books, and edited the Library of America edition of Jefferson’s collected writings.

From Leepson: A revealing history of Jefferson’s historical reputation from the 1820s to the 1930s .

The Hemingses of Monticello (2008), by Annette Gordon-Reed

Harvard law and history professor Annette Gordon-Reed tells the story of three generations in the family of Sally Hemings, a slave of Thomas Jefferson’s thought to have bore him children. She starts with Elizabeth Hemings, born in 1735, who with Jefferson’s father-in-law, John Wayles, had Sally, and then follows the narrative through Sally’s children. Without historical evidence, no one can be certain of the nature of Jefferson’s relationship with Hemings. But Gordon-Reed argues that it was a consensual romance. She won the 2008 National Book Award for nonfiction, the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for history and, in 2010, a MacArthur “genius grant.”

From Leepson: No list would be complete without a book on Jefferson, slavery and the Hemings family. This is the best one .

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino | | READ MORE

Megan Gambino is a senior web editor for Smithsonian magazine.

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

Thomas Jefferson

The 3rd President of the United States

The biography for President Jefferson and past presidents is courtesy of the White House Historical Association.

Thomas Jefferson, a spokesman for democracy, was an American Founding Father, the principal author of the Declaration of Independence (1776), and the third President of the United States (1801–1809).

In the thick of party conflict in 1800, Thomas Jefferson wrote in a private letter, “I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.”

This powerful advocate of liberty was born in 1743 in Albemarle County, Virginia, inheriting from his father, a planter and surveyor, some 5,000 acres of land, and from his mother, a Randolph, high social standing. He studied at the College of William and Mary, then read law. In 1772 he married Martha Wayles Skelton, a widow, and took her to live in his partly constructed mountaintop home, Monticello.

Freckled and sandy-haired, rather tall and awkward, Jefferson was eloquent as a correspondent, but he was no public speaker. In the Virginia House of Burgesses and the Continental Congress, he contributed his pen rather than his voice to the patriot cause. As the “silent member” of the Congress, Jefferson, at 33, drafted the Declaration of Independence. In years following he labored to make its words a reality in Virginia. Most notably, he wrote a bill establishing religious freedom, enacted in 1786.

Jefferson succeeded Benjamin Franklin as minister to France in 1785. His sympathy for the French Revolution led him into conflict with Alexander Hamilton when Jefferson was Secretary of State in President Washington’s Cabinet. He resigned in 1793.

Sharp political conflict developed, and two separate parties, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, began to form. Jefferson gradually assumed leadership of the Republicans, who sympathized with the revolutionary cause in France. Attacking Federalist policies, he opposed a strong centralized Government and championed the rights of states.

As a reluctant candidate for President in 1796, Jefferson came within three votes of election. Through a flaw in the Constitution, he became Vice President, although an opponent of President Adams. In 1800 the defect caused a more serious problem. Republican electors, attempting to name both a President and a Vice President from their own party, cast a tie vote between Jefferson and Aaron Burr. The House of Representatives settled the tie. Hamilton, disliking both Jefferson and Burr, nevertheless urged Jefferson’s election.

When Jefferson assumed the Presidency, the crisis in France had passed. He slashed Army and Navy expenditures, cut the budget, eliminated the tax on whiskey so unpopular in the West, yet reduced the national debt by a third. He also sent a naval squadron to fight the Barbary pirates, who were harassing American commerce in the Mediterranean. Further, although the Constitution made no provision for the acquisition of new land, Jefferson suppressed his qualms over constitutionality when he had the opportunity to acquire the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon in 1803.

During Jefferson’s second term, he was increasingly preoccupied with keeping the Nation from involvement in the Napoleonic wars, though both England and France interfered with the neutral rights of American merchantmen. Jefferson’s attempted solution, an embargo upon American shipping, worked badly and was unpopular.

Jefferson retired to Monticello to ponder such projects as his grand designs for the University of Virginia. A French nobleman observed that he had placed his house and his mind “on an elevated situation, from which he might contemplate the universe.”

He died on July 4, 1826.

Learn more about Thomas Jefferson’s spouse, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson .

Stay Connected

We'll be in touch with the latest information on how President Biden and his administration are working for the American people, as well as ways you can get involved and help our country build back better.

Opt in to send and receive text messages from President Biden.

Help inform the discussion

U.S. Presidents / Thomas Jefferson

1743 - 1826

Thomas jefferson.

…some honest men fear that a republican government can not be strong, that this Government is not strong enough; but would the honest patriot…abandon a government which has so far kept us free and firm…? I trust not. I believe this, on the contrary, the strongest Government on earth. First Inaugural Address

Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, spent his childhood roaming the woods and studying his books on a remote plantation in the Virginia Piedmont. Thanks to the prosperity of his father, Jefferson had an excellent education. After years in boarding school, where he excelled in classical languages, Jefferson enrolled in William and Mary College in his home state of Virginia, taking classes in science, mathematics, rhetoric, philosophy, and literature. He also studied law, and by the time he was admitted to the Virginia bar in April 1767, many considered him to have one of the nation's best legal minds.

Life In Depth Essays

- Life in Brief

- Life Before the Presidency

- Campaigns and Elections

- Domestic Affairs

- Foreign Affairs

- Life After the Presidency

- Family Life

- The American Franchise

- Impact and Legacy

Chicago Style

Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Thomas Jefferson.” Accessed May 14, 2024. https://millercenter.org/president/jefferson.

Professor of History

Professor Peter Onuf is the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Professor of History at the University of Virginia.

- -The Mind of Thomas Jefferson

- -Jefferson's Empire: The Language of American Nationhood

- -Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory, and Civic Culture (editor…

Featured Insights

US Presidents and Slavery

Before the Civil War, many US presidents, including Jefferson, owned enslaved people, and all of them had to deal with slavery as a political issue

Thomas Jefferson’s electoral revolution of 1800

Alan Taylor, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor at the University of Virginia, talks about the transfer of power to President Jefferson during the election of 1800

Thomas Jefferson and the problem of Union

History professors Gary Gallagher and Peter Onuf discuss Thomas Jefferson as part of the Miller Center’s Historical Presidency series

American Gospel: God, the founding fathers, and the making of a nation

Jon Meacham discusses America's ongoing struggle between politics and religion and looks at how our founding fathers' views on faith shaped religion's place in American public life

March 4, 1801: First Inaugural Address

June 20, 1803: instructions to captain lewis, december 6, 1805: special message to congress on foreign policy, featured video.

Redeeming Thomas Jefferson?

This American Forum episode examines Thomas Jefferson with two of America’s most esteemed Jefferson scholars.

Featured Publications

Advertisement

Supported by

Grand Bargainer

- Share full article

By Jill Abramson

- Nov. 2, 2012

The political biographies most popular in the modern era often tell us less about their subjects than about the moment in which the books themselves are published. John F. Kennedy’s “Profiles in Courage” won the Pulitzer Prize in 1957. But few remember its portraits of Senate lions like Thomas Hart Benton and George Norris. What lingers is its status as a kind of campaign document that set the table for Kennedy’s own rise from the Senate to the presidency. Similarly, “The Age of Jackson,” Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.’s vivid book, published in 1945, the year Franklin D. Roosevelt died, recast the populist Andrew Jackson as the bold progenitor of the New Deal — and also won a Pulitzer. Schlesinger’s multivolume history of the New Deal was called “The Age of Roosevelt” — tightening the link between the two projects and the two presidents.

In our time, presidential historians have been reaching back even further, to the founders, either in search of lessons useful for current debates or to re-examine the characters and leadership of those colossal figures in ways that can help clarify our own preoccupations. Thus, Joseph Ellis (in 1993) and David McCullough (in 2001), reviving John Adams, who had fallen into disrepute (in part because of the infamous Alien and Sedition Acts), depicted him as a farsighted statesman whose conservative instincts could be held up as a counterexample to the destructive passions of the Clinton and Bush years. Some recastings of the founders have been so original or counterintuitive as to alter their current reputations. This happened with “American Sphinx,” Ellis’s study of “the character of Thomas Jefferson,” which argued that the author of the Declaration of Independence and putative father of American democracy was also a scheming and even paranoid anti-monarchist, deficient in both wisdom and judgment, unlike his adversary, the stolid if unromantic Adams. This stinging revisionism was amplified in 2008, with the publication of “The Hemingses of Monticello,” Annette Gordon-Reed’s majestic study of Jefferson’s “other” family, his slave mistress and the children Jefferson had with her. The author’s exhaustive research resulted in both a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award and “gave fresh energy to the image of Jefferson-as-hypocrite,” as Jon Meacham observes in his new book, “Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power.”

Meacham is one of several journalists turned historians who belong to what might be called the Flawed Giant School. Other members include Walter Isaacson (on Benjamin Franklin), Evan Thomas (on Robert F. Kennedy and Dwight Eisenhower) and Jonathan Alter (on Roosevelt and the New Deal). Books in this mode usually present their subjects as figures of heroic grandeur despite all-too-human shortcomings — and so, again, speak directly to the current moment, with its diminished faith in government and in the nation’s elected leaders.

Few are better suited to this uplifting task than Meacham. A former editor of Newsweek, he has spent his career in the bosom of the Washington political and New York media establishments. His highly readable biographies are well researched, drawing on new anecdotal material and up-to-date historiographical interpretations (thereby satisfying both journalistic and scholarly expectation). At the same time his rendering of people and events reflects and reifies Establishment values and ideals. His new book lacks the conceptual boldness of those by Ellis and Gordon-Reed but lies close to his own preoccupations — as gleaned from the many glittering names in his acknowledgments, from Robert Caro to Mika Brzezinski, that exhibit an impressively well-tuned appreciation for the social status quo.

And Meacham has been here before. His previous book, “American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House,” published just as a grass-roots tide swept Barack Obama into office, was a best seller and also won the Pulitzer. The quintessential Flawed Giant biography, it made the case that Jackson was a fresh voice of the people who protected individual liberty yet simultaneously “pressed the known limits of presidential power.” Meacham didn’t sugarcoat Jackson’s ruthless handling of slavery and American Indians, even as he made the case that Jackson’s presidency was among the greatest in history.

Meacham reaches the same conclusion about Jefferson, this time writing on the heels of a bruising presidential campaign in which voters have openly expressed their alienation from politicians as a class and have objected to the ever-growing partisan divide and the resulting near-paralysis of the federal government. The time does seem right to highlight Jefferson’s skills as a practicing politician, unafraid to wield “the art of power” or to put it to uses often at odds with his small-government ideology. So insistently does Meacham stress Jefferson’s pragmatism, which at times made him appear hypocritical to his followers no less than to his opponents, that in places the book has a curiously focus-grouped quality, as though Meacham has carefully balanced the consensus view of Jefferson the visionary “framer” and “founder” against the dissenting claims of assorted critics and skeptics, apportioning equal time to each. But to be fair, he also suggests that Jefferson himself was attuned to the medley of voices and competing interests. And what could be more reassuring in 2012 than a biography that explains how in turbulent, divided times a great president actually managed to govern?

“Jefferson understood a timeless truth,” Meacham writes, “that politics is kaleidoscopic, constantly shifting, and the morning’s foe may well be the afternoon’s friend.” One hears the ice cubes clinking in President Reagan’s highball as he and House Speaker Tip O’Neill shared drinks and jokes in the White House and hammered together a deal on Social Security. Jefferson too “believed in the politics of the personal relationship,” Meacham observes, and “saw himself as a political creature,” not only the philosophe and dreamer others supposed. In moves that Meacham clearly admires — and that he implies are instructive today — Jefferson repeatedly reached out to his enemies and showed ideological flexibility. A momentous example came in 1790, when he was George Washington’s secretary of state. Jefferson’s archenemy Alexander Hamilton, the Treasury secretary, had laid out a plan for the federal assumption of states’ debts, anathema to Jefferson, since it “would create the need for federal taxes to pay down the debts,” Meacham explains, “and the power to tax was, as ever, the most fundamental and far-reaching of all the powers of government.” The issue bitterly divided the states, and Jefferson’s great friend and ideological soul mate, James Madison, had led the forces in Congress that voted down Hamilton’s proposal. Jefferson, for his part, had come “to see Hamilton as the embodiment of the deepest of republican fears: as a man who might be willing to sacrifice the American undertaking in liberty to the expediency of arbitrary authority,” Meacham writes. But then, one night in New York (then the nation’s capital), the two cabinet adversaries met near Washington’s door. Hamilton, looking “somber, haggard and dejected beyond description,” as Jefferson later remembered, pleaded for help. Realizing “matters were dire,” Jefferson pitched in. “The beginning of wisdom, Jefferson thought, might lie in a meeting of the principals out of the public eye,” Meacham writes. “So he convened a dinner,” on the grounds that, as Jefferson put it, “men of sound heads and honest views needed nothing more than explanation and mutual understanding to enable them to unite in some measures which might enable us to get along.” And in this case the stakes were high, for “if everyone retains inflexibly his present opinion, there will be no bill passed at all,” Jefferson warned, and “without funding there is an end of the government.” Needless to say, a compromise was reached. “Jefferson had struck the deal he could strike, and for the moment, America was the stronger for it.” President Obama and Speaker Boehner, are you listening?

But Meacham doesn’t simply dispense soothing history lessons. He argues persuasively that for Jefferson the ideal of liberty was not incompatible with a strong federal government, and also that Jefferson’s service in the Congress in 1776 left him thoroughly versed in the ways and means of politics. “He had defined an ideal in the Declaration, using words to transform principle into policy, and he had lived with the reality of managing both a war and a fledgling government,” Meacham writes. “A politician’s task was to bring reality and policy into the greatest possible accord with the ideal and the principled.”

Not that Jefferson was lavishly endowed with obvious political gifts. “Shy in manner, seeming cold; awkward in attitude, and with little in his bearing that suggested command” — so Henry Adams described him, in his great study of Jefferson’s two presidential terms. Though a peerless rhetorician, he did not always use this skill to best effect when in office. As the historian Eric McKitrick has pointed out, Jefferson gave no speeches during his entire presidency apart from reading, inaudibly, his two Inaugural Addresses.

One wishes Meacham offered more concrete details about Jefferson’s highest political achievements — including drafting, at age 33, the Declaration of Independence and, one year later, the seminal Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. Both define the fundamental liberties that are the heart of democracy as well as Jefferson’s sweeping political vision for the new nation. Meacham does justice to other writings, especially the 158 letters Jefferson and Adams exchanged in the winter of their lives when, after decades of bitterness over perceived betrayals, they reconciled, two “aging revolutionaries” rekindling the shared intellectual and moral interests that had bound them together so many years before when both emerged as leaders in the Continental Congress, and renewing their longstanding debates about democracy and America.

“Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power” guides us through the entire life, but without much color or drama. When Meacham offers revealing details — for instance illustrating Jefferson’s lifelong love of horses by listing the funny names he gave his own (Polly Peachum, Peggy Waffington) — the book comes alive, and Jefferson does too. But other opportunities are missed. Sally Hemings has only a few walk-on scenes, leaving the reader hungry for more on this fascinating, and troubling, relationship. For Meacham, pronouncement trumps storytelling. Often he resorts to the formulaic summarizing sentence: “Though he had hardly left the arena, he was now unmistakably back in it,” Meacham writes of Jefferson during Washington’s second term. Jefferson then lost the presidency, barely, to Adams in the Electoral College. It was an ugly fight, but Meacham, characteristically, covers it with balm: “However different in form presidential contests were, one feature has been constant from the beginning,” he reminds us. “They have been rife with attacks and counterattacks.”

We have heard this before, of course. But then, Jefferson’s life and career have been subjected to exhaustive scrutiny since at least 1943, when Dumas Malone began work on the definitive six-volume biography, completed some 40 years later, that sealed Jefferson’s place as the most interesting and conceivably greatest president.

Meacham touches all the familiar bases, beginning with Jefferson’s birth in 1743. The son of distinguished parents — his father a successful planter and surveyor, his mother from one of Virginia’s best families — Jefferson “was raised to wield power,” Meacham writes, and to “grow comfortable with authority.”

His range of talents was almost limitless. He was 26 when he sketched the first designs for Monticello, his grand construction project, the 33-room mansion that was his home until his death, though never definitively completed. (Visitors reported having to step over beams or piles of soil from one of Jefferson’s constant renovations.) After studying with a tutor and attending the College of William and Mary, he served in the House of Burgesses and in the Continental Congress and was chosen to draft the Declaration over elders, including John Adams, who said, “You can write 10 times better than I can.”

But Jefferson’s first executive position, as governor of Virginia during the Revolutionary War, ended in near disgrace. When the British troops massed, Jefferson fled to Monticello and was accused of both dereliction of duty and cowardice. He was exonerated, but the episode haunted him for many years. Sent to the Continent after the war to help negotiate treaties with the great powers, he came to love European culture and food. He then returned to Washington’s cabinet, where he pursued his battles and compromises with Hamilton, the two elucidating the quarrel, over the size and role of the federal government, that still shapes our most profound political disagreements. When Jefferson became president, in 1801, it was the first time in our history that leadership transferred from one party to another.

The Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark expedition highlighted his first term, while his second bogged down in an unsuccessful effort to prevent further war with England and possibly France. When he left office, he returned to his beloved Monticello, where he resumed his many extrapolitical enthusiasms — horses, literature and the serious study of science, agronomy and architecture. He also undertook his last great project, founding the University of Virginia and designing many of its buildings, including the magnificent rotunda. He died, as did John Adams, on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, on July 4, 1826. He was 83.

It is easy to see why such a life, with its grand sweep and many events so central to American history, took up so many volumes by Henry Adams and then Dumas Malone. Meacham wisely has chosen to look at Jefferson through a political lens, assessing how he balanced his ideals with pragmatism while also bending others to his will. And just as he scolded Jackson, another slaveholder and champion of individual liberty, for being a hypocrite, so Meacham gives a tough-minded account of Jefferson’s slippery recalibrations on race, noting, “Slavery was the rare subject where Jefferson’s sense of realism kept him from marshaling his sense of hope in the service of the cause of reform.” In 1814 Jefferson wrote, “There is nothing I would not sacrifice to a practicable plan of abolishing every vestige of this moral and political depravity.” This wasn’t true. Jefferson “was not willing to sacrifice his own way of life, though he characteristically left himself a rhetorical escape by introducing the subjective standard of practicability,” Meacham observes. In fact, his slaves were his most valuable possessions. He also believed emancipation would precipitate a race war. The only solution was for free blacks to be exiled to another country. These were the reasons, or excuses, that underlay Jefferson’s justifications of slavery, though they were not his ideas alone. Lincoln, too, considered expatriation a viable solution to the slavery problem.

The art of power often involves brutality — and other offenses too. Jefferson was sometimes more sneaky than artful. Meacham lets him off fairly easily for having smeared John Adams, though it was Jefferson who secretly paid for a poisonous anti-Adams pamphlet prepared by the hack journalist James Thomson Callender. Joseph Ellis, referring to this bleak campaign, accuses Jefferson of “paying off hired character assassins.” Meacham, in extenuation, says first that Callender was someone “whom Jefferson had supported financially” and later that this support “had been based on opposition to the sedition laws and his agreement” with Callender’s politics, as if these reasons justified Jefferson’s collusion.

Elsewhere Meacham is more convincing. Where other historians have found hypocrisy in Jefferson’s use of executive power to complete the Louisiana Purchase, Meacham is nuanced and persuasive. His solid argument is that in order to transform the United States into a continental power, Jefferson sensibly drew on all of his political skills to secure the vast territory from France, but did so without abandoning his distrust of strong, centralized power.

Meacham, so determined to celebrate Jefferson and his use of power, departs from others as well in his relatively kind assessment of Jefferson’s second term, marked by a trade embargo that failed to prevent European wars and also exacted severe hardship at home. Going further, Jefferson, the enemy of federal power, assumed total control over American shipping. Meacham concedes that “history has not been kind to Jefferson’s embargo” but concludes it was a pragmatic power play that at least delayed war. If not a good idea, “it was the least bad.” Others disagree. Henry Adams, writing in the 1880s, judged Jefferson’s second term a failure “under which his old hopes and ambitions were crushed,” and added that the ensuing “loss of popularity was his bitterest trial.” Yet Meacham is right to note that Jefferson influenced almost all the presidents who came immediately after him, with the exception of John Quincy Adams, and right as well to reckon this as an immense political legacy. As an Establishment man, Meacham ultimately celebrates the art of political compromise in service of moving the nation forward. It is an argument unlikely to meet with disapproval.

THOMAS JEFFERSON

The art of power.

By Jon Meacham

Illustrated. 759 pp. Random House. $35.

An earlier version of the caption with the picture showing a group of the founders drafting the Declaration of Independence reversed the identifications of John Adams and Robert Livingston.

How we handle corrections

Jill Abramson is the executive editor of The Times.

My Journey Through the Best Presidential Biographies

The Best Biographies of Thomas Jefferson

16 Thursday May 2013

Posted by Steve in Best Biographies Posts , President #03 - T Jefferson

≈ 62 Comments

American history , best biographies , book reviews , Dumas Malone , John Boles , Jon Meacham , Joseph Ellis , Kevin Hayes , Merrill Peterson , presidential biographies , Presidents , Thomas Jefferson , Willard Sterne Randall

After nearly two months with Thomas Jefferson involving five biographies (ten books in total) and over 5,000 pages of reading, I still feel I know Jefferson less well than many other revolutionary-era figures…including some like Alexander Hamilton who I’ve only encountered through his numerous appearances in various presidential biographies.

But that’s part of the intriguing mystery that Jefferson presents – even the most dedicated Jefferson scholars such as Malone and Peterson have admitted difficulty in getting to know our third president on a personal level. In his biography of Jefferson, Merrill Peterson acknowledged being mortified in confessing he still found Jefferson “impenetrable” after years of study.

Part of what seems to make Jefferson so complex is that he is not merely a two-dimensional figure. The set of internal rules governing his behavior resembles a multi-variable differential equation whose output seems maddeningly inconsistent at times. But on a basic level, Jefferson is no different than most of us – guided by a small number of core convictions, steered by a larger set of general principles, and influenced by a broad group of more nebulous forces.

Only that smallest group of convictions seemed to guide Jefferson as if they were immutable laws of physics. His other principles and beliefs were more maleable, able to change under great strain, competing forces, or compelling circumstances of the moment. He was a passionately private man, yet ended up in public office for most of his adult life. He professed the evils of slavery, yet owned slaves (and may have even had a long-term relationship with one). He was intensely afraid of the power of a broad federal government under the direction of a strong president, yet as president did very little to curb that power and in many instances did just the opposite.

* Dumas Malone’s six-volume series (“Jefferson and His Time”) took over three decades to complete – it was begun when my parents were not old enough to walk, and finished when I was almost entering middle school. This series, to which Malone dedicated a huge chunk of his adult life, took me just five (rather intense) weeks to read.

Although this series does not receive high marks as a means of “entertainment” it receives the very best marks for its content and scholarship. The first five volumes won the Pulitzer Prize in 1975.

Volume 1 (“Jefferson the Virginian”) covers the first four decades of Jefferson’s life, up to the point when became a diplomat in Europe. Volume 2 (“Jefferson and the Rights of Man”) covers the years 1784-1792 which Jefferson spent in Europe as a diplomat and as George Washington’s first Secretary of State.

Volume 3 (“Jefferson and the Ordeal of Liberty”) covers the last year of Jefferson’s tenure as Secretary of State, his three-year retirement at Monticello, his years as John Adams’ Vice President and his election to the presidency in 1800. Volumes 4 and 5 (“Jefferson the President”) cover his eight year presidency while Volume 6 (“The Sage of Monticello”) covers the final seventeen years of Jefferson’s life.

As thorough and comprehensive as any biography on Jefferson could possibly be, the series suffers only from being less “readable” than more recent biographies which are written in modern, well-flowing verse, and perhaps for not addressing the Hemings controversy with evidence that has only recently come to light.

Malone’s series on Thomas Jefferson reminds me of Thomas Flexner’s series on Washington and Page Smith’s on John Adams – together, these three great works are in a class all to themselves. (Full reviews: Vol 1 , Vol 2 , Vol 3 , Vol 4 , Vol 5 , Vol 6 )

Merrill Peterson’s “ Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation, ” published in 1970, was written while Malone was about halfway through his series on Jefferson. In no other single-volume biography of any of our first three presidents can a reader find a more comprehensive book, chock-a-block with such an impressive level of relevant detail. Yet compared to Malone’s series, while it seems to contain proportionately similar granularity, it also seems to contain relatively fewer interesting conclusory remarks and insights.

Without a doubt, no serious library would be complete without a copy of Peterson’s classic. But with the benefit of hindsight, if I were forced to choose between reading Malone’s six-volume series or Peterson’s single-volume biography, I would not hesitate to invest the additional time required to experience Malone’s series. ( Full review here )

Joseph Ellis’s “ American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson ” was published in 1996, three years after he published his biography of John Adams. This is by far my favorite of Ellis’s books, and the second most “enjoyable” read among the Jefferson biographies.

Like each of Ellis’s works I’ve read so far, this book is not quite a biography and should not be read as such. In my opinion, the best way to enjoy “American Sphinx” is to first read either Malone’s series or Peterson’s biography. Ellis not only observes Jefferson’s behavior throughout life, as have other authors, but also synthesizes his observations into a set of characteristics that seems to have defined Jefferson’s personality. This book comes as close to getting into Jefferson’s mind as any book I’ve read. ( Full review here )

“ Twilight at Monticello: The Final Years of Thomas Jefferson ” by Alan Pell Crawford was published in 2008 and, despite a number of imperfections, proves quite an enjoyable and easy read. Although it exudes a slight tabloid “feel” Crawford has exploited a niche never before fully explored – even Malone’s last volume focusing on Jefferson’s retirement years seems slightly incomplete in hindsight.

By the end of the book, though, it feels as thought the author may have tried too hard to make his case. Rather than coming across as insightful and revealing, the book finally beings to feel hyperbolic and melodramatic. Nonetheless, as my next-to-last book on Jefferson, it was perfectly timed and absorbingly provocative. ( Full review here )

“ Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power ” by Jon Meacham was published in 2012 and is currently the most popular of the Jefferson biographies. As I’ve discovered from readers of this site, Meacham is a polarizing author. Those who love him do so because his primary mission seems to be to entertain and, only secondarily, to inform. Others find him distressing for exactly the same reason, sensing that he merely puts new wrapping paper on an old treasure.

But no matter your take on Meacham, “The Art of Power” is both easy and enjoyable to read. At times it is thoroughly engrossing and contains its own interesting perspective on Jefferson’s life. Although it is lighter on penetrating, recently-uncovered insights and heavier on clever one-liners than previous Jefferson biographies, it probably serves as the perfect “second” biography of Jefferson. ( Full review here )

– – – – – – –

[ Added January 2020 ]

* In 2013, I read four single-volume biographies of Jefferson and the six-volume series described above. Since then I’ve had the chance to read a biography of Jefferson I missed on that first trip through Jefferson: Willard Sterne Randall’s “ Thomas Jefferson: A Life ” which was published in 1993. But while it is uniquely valuable as a study of Jefferson’s legal studies and career, it covers most of the remainder of his life – including his presidency – with less dexterity and it turned out to be my least-favorite biography of Jefferson thus far. ( Full review here )

[ Added October 2021 ]

* I’ve also now read John Boles’s 2017 biography “ Jefferson: Architect of American Liberty .” With 520 pages of text, this biography proves uncommonly thoughtful, thorough and revealing. Boles expends no small effort in attempting to unravel Jefferson’s complexity and perplexing contradictions – including the large gap between his attitude toward slavery and his actions – and here the book is quite successful. Less ideal is the relative lack of focus on understanding and revealing Jefferson’s friendships with figures such as James Madison and John Adams. And Boles’s writing style, while crisp and articulate, is rarely particularly colorful or engrossing. But overall this is perhaps the best modern, single-volume introduction to Jefferson’s life and times. ( Full review here )

[ Added August 2022 ]