Reported Speech – Rules, Examples & Worksheet

| Candace Osmond

Candace Osmond

Candace Osmond studied Advanced Writing & Editing Essentials at MHC. She’s been an International and USA TODAY Bestselling Author for over a decade. And she’s worked as an Editor for several mid-sized publications. Candace has a keen eye for content editing and a high degree of expertise in Fiction.

They say gossip is a natural part of human life. That’s why language has evolved to develop grammatical rules about the “he said” and “she said” statements. We call them reported speech.

Every time we use reported speech in English, we are talking about something said by someone else in the past. Thinking about it brings me back to high school, when reported speech was the main form of language!

Learn all about the definition, rules, and examples of reported speech as I go over everything. I also included a worksheet at the end of the article so you can test your knowledge of the topic.

What Does Reported Speech Mean?

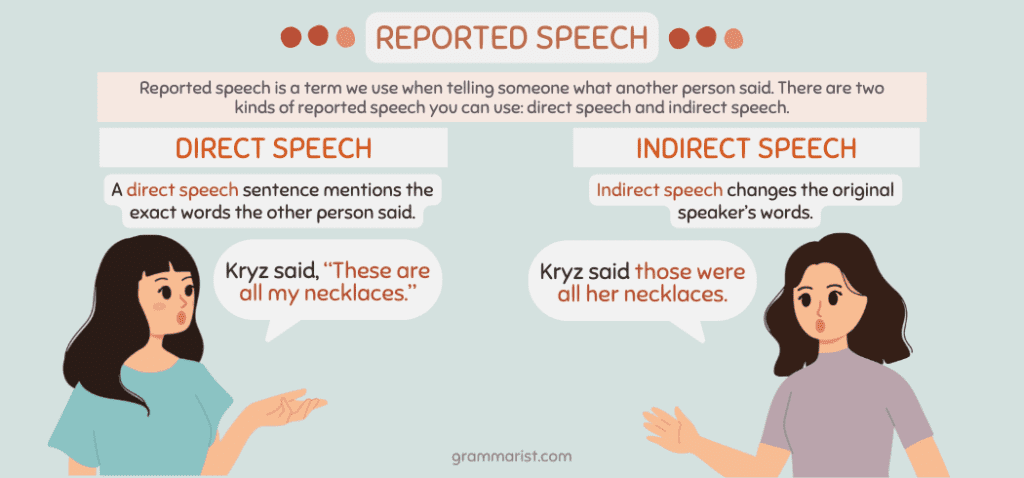

Reported speech is a term we use when telling someone what another person said. You can do this while speaking or writing.

There are two kinds of reported speech you can use: direct speech and indirect speech. I’ll break each down for you.

A direct speech sentence mentions the exact words the other person said. For example:

- Kryz said, “These are all my necklaces.”

Indirect speech changes the original speaker’s words. For example:

- Kryz said those were all her necklaces.

When we tell someone what another individual said, we use reporting verbs like told, asked, convinced, persuaded, and said. We also change the first-person figure in the quotation into the third-person speaker.

Reported Speech Examples

We usually talk about the past every time we use reported speech. That’s because the time of speaking is already done. For example:

- Direct speech: The employer asked me, “Do you have experience with people in the corporate setting?”

Indirect speech: The employer asked me if I had experience with people in the corporate setting.

- Direct speech: “I’m working on my thesis,” I told James.

Indirect speech: I told James that I was working on my thesis.

Reported Speech Structure

A speech report has two parts: the reporting clause and the reported clause. Read the example below:

- Harry said, “You need to help me.”

The reporting clause here is William said. Meanwhile, the reported clause is the 2nd clause, which is I need your help.

What are the 4 Types of Reported Speech?

Aside from direct and indirect, reported speech can also be divided into four. The four types of reported speech are similar to the kinds of sentences: imperative, interrogative, exclamatory, and declarative.

Reported Speech Rules

The rules for reported speech can be complex. But with enough practice, you’ll be able to master them all.

Choose Whether to Use That or If

The most common conjunction in reported speech is that. You can say, “My aunt says she’s outside,” or “My aunt says that she’s outside.”

Use if when you’re reporting a yes-no question. For example:

- Direct speech: “Are you coming with us?”

Indirect speech: She asked if she was coming with them.

Verb Tense Changes

Change the reporting verb into its past form if the statement is irrelevant now. Remember that some of these words are irregular verbs, meaning they don’t follow the typical -d or -ed pattern. For example:

- Direct speech: I dislike fried chicken.

Reported speech: She said she disliked fried chicken.

Note how the main verb in the reported statement is also in the past tense verb form.

Use the simple present tense in your indirect speech if the initial words remain relevant at the time of reporting. This verb tense also works if the report is something someone would repeat. For example:

- Slater says they’re opening a restaurant soon.

- Maya says she likes dogs.

This rule proves that the choice of verb tense is not a black-and-white question. The reporter needs to analyze the context of the action.

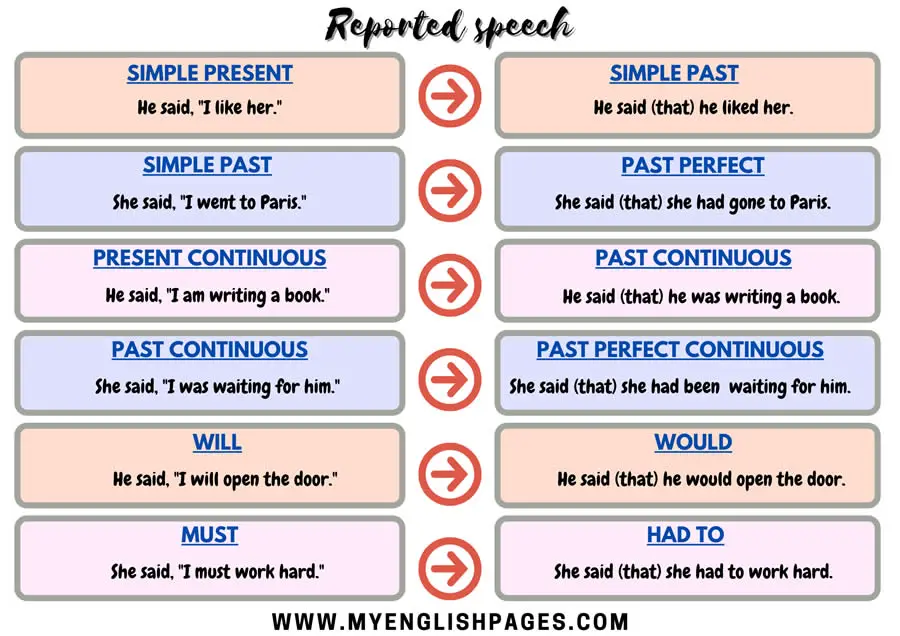

Move the tense backward when the reporting verb is in the past tense. That means:

- Present simple becomes past simple.

- Present perfect becomes past perfect.

- Present continuous becomes past continuous.

- Past simple becomes past perfect.

- Past continuous becomes past perfect continuous.

Here are some examples:

- The singer has left the building. (present perfect)

He said that the singers had left the building. (past perfect)

- Her sister gave her new shows. (past simple)

- She said that her sister had given her new shoes. (past perfect)

If the original speaker is discussing the future, change the tense of the reporting verb into the past form. There’ll also be a change in the auxiliary verbs.

- Will or shall becomes would.

- Will be becomes would be.

- Will have been becomes would have been.

- Will have becomes would have.

For example:

- Direct speech: “I will be there in a moment.”

Indirect speech: She said that she would be there in a moment.

Do not change the verb tenses in indirect speech when the sentence has a time clause. This rule applies when the introductory verb is in the future, present, and present perfect. Here are other conditions where you must not change the tense:

- If the sentence is a fact or generally true.

- If the sentence’s verb is in the unreal past (using second or third conditional).

- If the original speaker reports something right away.

- Do not change had better, would, used to, could, might, etc.

Changes in Place and Time Reference

Changing the place and time adverb when using indirect speech is essential. For example, now becomes then and today becomes that day. Here are more transformations in adverbs of time and places.

- This – that.

- These – those.

- Now – then.

- Here – there.

- Tomorrow – the next/following day.

- Two weeks ago – two weeks before.

- Yesterday – the day before.

Here are some examples.

- Direct speech: “I am baking cookies now.”

Indirect speech: He said he was baking cookies then.

- Direct speech: “Myra went here yesterday.”

Indirect speech: She said Myra went there the day before.

- Direct speech: “I will go to the market tomorrow.”

Indirect speech: She said she would go to the market the next day.

Using Modals

If the direct speech contains a modal verb, make sure to change them accordingly.

- Will becomes would

- Can becomes could

- Shall becomes should or would.

- Direct speech: “Will you come to the ball with me?”

Indirect speech: He asked if he would come to the ball with me.

- Direct speech: “Gina can inspect the room tomorrow because she’s free.”

Indirect speech: He said Gina could inspect the room the next day because she’s free.

However, sometimes, the modal verb should does not change grammatically. For example:

- Direct speech: “He should go to the park.”

Indirect speech: She said that he should go to the park.

Imperative Sentences

To change an imperative sentence into a reported indirect sentence, use to for imperative and not to for negative sentences. Never use the word that in your indirect speech. Another rule is to remove the word please . Instead, say request or say. For example:

- “Please don’t interrupt the event,” said the host.

The host requested them not to interrupt the event.

- Jonah told her, “Be careful.”

- Jonah ordered her to be careful.

Reported Questions

When reporting a direct question, I would use verbs like inquire, wonder, ask, etc. Remember that we don’t use a question mark or exclamation mark for reports of questions. Below is an example I made of how to change question forms.

- Incorrect: He asked me where I live?

Correct: He asked me where I live.

Here’s another example. The first sentence uses direct speech in a present simple question form, while the second is the reported speech.

- Where do you live?

She asked me where I live.

Wrapping Up Reported Speech

My guide has shown you an explanation of reported statements in English. Do you have a better grasp on how to use it now?

Reported speech refers to something that someone else said. It contains a subject, reporting verb, and a reported cause.

Don’t forget my rules for using reported speech. Practice the correct verb tense, modal verbs, time expressions, and place references.

Grammarist is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. When you buy via the links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission at no cost to you.

2024 © Grammarist, a Found First Marketing company. All rights reserved.

- English Grammar

- Reported Speech

Reported Speech - Definition, Rules and Usage with Examples

Reported speech or indirect speech is the form of speech used to convey what was said by someone at some point of time. This article will help you with all that you need to know about reported speech, its meaning, definition, how and when to use them along with examples. Furthermore, try out the practice questions given to check how far you have understood the topic.

Table of Contents

Definition of reported speech, rules to be followed when using reported speech, table 1 – change of pronouns, table 2 – change of adverbs of place and adverbs of time, table 3 – change of tense, table 4 – change of modal verbs, tips to practise reported speech, examples of reported speech, check your understanding of reported speech, frequently asked questions on reported speech in english, what is reported speech.

Reported speech is the form in which one can convey a message said by oneself or someone else, mostly in the past. It can also be said to be the third person view of what someone has said. In this form of speech, you need not use quotation marks as you are not quoting the exact words spoken by the speaker, but just conveying the message.

Now, take a look at the following dictionary definitions for a clearer idea of what it is.

Reported speech, according to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, is defined as “a report of what somebody has said that does not use their exact words.” The Collins Dictionary defines reported speech as “speech which tells you what someone said, but does not use the person’s actual words.” According to the Cambridge Dictionary, reported speech is defined as “the act of reporting something that was said, but not using exactly the same words.” The Macmillan Dictionary defines reported speech as “the words that you use to report what someone else has said.”

Reported speech is a little different from direct speech . As it has been discussed already, reported speech is used to tell what someone said and does not use the exact words of the speaker. Take a look at the following rules so that you can make use of reported speech effectively.

- The first thing you have to keep in mind is that you need not use any quotation marks as you are not using the exact words of the speaker.

- You can use the following formula to construct a sentence in the reported speech.

- You can use verbs like said, asked, requested, ordered, complained, exclaimed, screamed, told, etc. If you are just reporting a declarative sentence , you can use verbs like told, said, etc. followed by ‘that’ and end the sentence with a full stop . When you are reporting interrogative sentences, you can use the verbs – enquired, inquired, asked, etc. and remove the question mark . In case you are reporting imperative sentences , you can use verbs like requested, commanded, pleaded, ordered, etc. If you are reporting exclamatory sentences , you can use the verb exclaimed and remove the exclamation mark . Remember that the structure of the sentences also changes accordingly.

- Furthermore, keep in mind that the sentence structure , tense , pronouns , modal verbs , some specific adverbs of place and adverbs of time change when a sentence is transformed into indirect/reported speech.

Transforming Direct Speech into Reported Speech

As discussed earlier, when transforming a sentence from direct speech into reported speech, you will have to change the pronouns, tense and adverbs of time and place used by the speaker. Let us look at the following tables to see how they work.

Here are some tips you can follow to become a pro in using reported speech.

- Select a play, a drama or a short story with dialogues and try transforming the sentences in direct speech into reported speech.

- Write about an incident or speak about a day in your life using reported speech.

- Develop a story by following prompts or on your own using reported speech.

Given below are a few examples to show you how reported speech can be written. Check them out.

- Santana said that she would be auditioning for the lead role in Funny Girl.

- Blaine requested us to help him with the algebraic equations.

- Karishma asked me if I knew where her car keys were.

- The judges announced that the Warblers were the winners of the annual acapella competition.

- Binsha assured that she would reach Bangalore by 8 p.m.

- Kumar said that he had gone to the doctor the previous day.

- Lakshmi asked Teena if she would accompany her to the railway station.

- Jibin told me that he would help me out after lunch.

- The police ordered everyone to leave from the bus stop immediately.

- Rahul said that he was drawing a caricature.

Transform the following sentences into reported speech by making the necessary changes.

1. Rachel said, “I have an interview tomorrow.”

2. Mahesh said, “What is he doing?”

3. Sherly said, “My daughter is playing the lead role in the skit.”

4. Dinesh said, “It is a wonderful movie!”

5. Suresh said, “My son is getting married next month.”

6. Preetha said, “Can you please help me with the invitations?”

7. Anna said, “I look forward to meeting you.”

8. The teacher said, “Make sure you complete the homework before tomorrow.”

9. Sylvester said, “I am not going to cry anymore.”

10. Jade said, “My sister is moving to Los Angeles.”

Now, find out if you have answered all of them correctly.

1. Rachel said that she had an interview the next day.

2. Mahesh asked what he was doing.

3. Sherly said that her daughter was playing the lead role in the skit.

4. Dinesh exclaimed that it was a wonderful movie.

5. Suresh said that his son was getting married the following month.

6. Preetha asked if I could help her with the invitations.

7. Anna said that she looked forward to meeting me.

8. The teacher told us to make sure we completed the homework before the next day.

9. Sylvester said that he was not going to cry anymore.

10. Jade said that his sister was moving to Los Angeles.

What is reported speech?

What is the definition of reported speech.

Reported speech, according to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, is defined as “a report of what somebody has said that does not use their exact words.” The Collins Dictionary defines reported speech as “speech which tells you what someone said, but does not use the person’s actual words.” According to the Cambridge Dictionary, reported speech is defined as “the act of reporting something that was said, but not using exactly the same words.” The Macmillan Dictionary defines reported speech as “the words that you use to report what someone else has said.”

What is the formula of reported speech?

You can use the following formula to construct a sentence in the reported speech. Subject said that (report whatever the speaker said)

Give some examples of reported speech.

Given below are a few examples to show you how reported speech can be written.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Reported Speech

Perfect english grammar.

Reported Statements

Here's how it works:

We use a 'reporting verb' like 'say' or 'tell'. ( Click here for more about using 'say' and 'tell' .) If this verb is in the present tense, it's easy. We just put 'she says' and then the sentence:

- Direct speech: I like ice cream.

- Reported speech: She says (that) she likes ice cream.

We don't need to change the tense, though probably we do need to change the 'person' from 'I' to 'she', for example. We also may need to change words like 'my' and 'your'. (As I'm sure you know, often, we can choose if we want to use 'that' or not in English. I've put it in brackets () to show that it's optional. It's exactly the same if you use 'that' or if you don't use 'that'.)

But , if the reporting verb is in the past tense, then usually we change the tenses in the reported speech:

- Reported speech: She said (that) she liked ice cream.

* doesn't change.

- Direct speech: The sky is blue.

- Reported speech: She said (that) the sky is/was blue.

Click here for a mixed tense exercise about practise reported statements. Click here for a list of all the reported speech exercises.

Reported Questions

So now you have no problem with making reported speech from positive and negative sentences. But how about questions?

- Direct speech: Where do you live?

- Reported speech: She asked me where I lived.

- Direct speech: Where is Julie?

- Reported speech: She asked me where Julie was.

- Direct speech: Do you like chocolate?

- Reported speech: She asked me if I liked chocolate.

Click here to practise reported 'wh' questions. Click here to practise reported 'yes / no' questions. Reported Requests

There's more! What if someone asks you to do something (in a polite way)? For example:

- Direct speech: Close the window, please

- Or: Could you close the window please?

- Or: Would you mind closing the window please?

- Reported speech: She asked me to close the window.

- Direct speech: Please don't be late.

- Reported speech: She asked us not to be late.

Reported Orders

- Direct speech: Sit down!

- Reported speech: She told me to sit down.

- Click here for an exercise to practise reported requests and orders.

- Click here for an exercise about using 'say' and 'tell'.

- Click here for a list of all the reported speech exercises.

Hello! I'm Seonaid! I'm here to help you understand grammar and speak correct, fluent English.

Read more about our learning method

Reported Speech (Indirect Speech) in English – Summary

How to use reported speech.

If you have a sentence in Direct Speech, try to follow our 5 steps to put the sentence into Reported Speech..

- Define the type of the sentence (statement, questions, command)

- What tense is used in the introductory sentence?

- Do you have to change the person (pronoun)?

- Do you have to backshift the tenses?

- Do you have to change expressions of time and place?

1. Statements, Questions, Commands

Mind the type of sentences when you use Reported Speech. There is more detailed information on the following pages.

- Commands, Requests

2. The introductory sentence

If you use Reported Speech there are mostly two main differences.

The introductory sentence in Reported Speech can be in the Present or in the Past .

If the introductory sentences is in the Simple Present, there is no backshift of tenses.

Direct Speech:

- Susan, “ Mary work s in an office.”

Reported Speech:

- Introductory sentence in the Simple Present → Susan says (that)* Mary work s in an office.

- Introductory sentence in the Simple Past → Susan said (that)* Mary work ed in an office.

3. Change of persons/pronouns

If there is a pronoun in Direct Speech, it has possibly to be changed in Reported Speech, depending on the siutation.

- Direct Speech → Susan, “I work in an office.”

- Reported Speech → Susan said (that)* she worked in an office.

Here I is changed to she .

4. Backshift of tenses

If there is backshift of tenses in Reported Speech, the tenses are shifted the following way.

- Direct Speech → Peter, “ I work in the garden.”

- Reported Speech → Peter said (that)* he work ed in the garden.

5. Conversion of expressions of time and place

If there is an expression of time/place in the sentence, it may be changed, depending on the situation.

- Direct Speech → Peter, “I worked in the garden yesterday .”

- Reported Speech → Peter said (that) he had worked in the garden the day before .

6. Additional information

In some cases backshift of tenses is not necessary, e.g. when statements are still true. Backshift of tenses is never wrong.

- John, “My brother is at Leipzig university.”

- John said (that) his brother was at Leipzig university. or

- John said (that) his brother is at Leipzig university.

when you use general statements.

- Mandy, “The sun rises in the east.”

- Mandy said (that) the sun rose in the east. or

- Mandy said (that) the sun rises in the east.

* The word that is optional, that is the reason why we put it in brackets.

- You are here:

- Grammar Explanations

- Reported Speech

Search form

- B1-B2 grammar

Reported speech

Daisy has just had an interview for a summer job.

Instructions

As you watch the video, look at the examples of reported speech. They are in red in the subtitles. Then read the conversation below to learn more. Finally, do the grammar exercises to check you understand, and can use, reported speech correctly.

Sophie: Mmm, it’s so nice to be chilling out at home after all that running around.

Ollie: Oh, yeah, travelling to glamorous places for a living must be such a drag!

Ollie: Mum, you can be so childish sometimes. Hey, I wonder how Daisy’s getting on in her job interview.

Sophie: Oh, yes, she said she was having it at four o’clock, so it’ll have finished by now. That’ll be her ... yes. Hi, love. How did it go?

Daisy: Well, good I think, but I don’t really know. They said they’d phone later and let me know.

Sophie: What kind of thing did they ask you?

Daisy: They asked if I had any experience with people, so I told them about helping at the school fair and visiting old people at the home, that sort of stuff. But I think they meant work experience.

Sophie: I’m sure what you said was impressive. They can’t expect you to have had much work experience at your age.

Daisy: And then they asked me what acting I had done, so I told them that I’d had a main part in the school play, and I showed them a bit of the video, so that was cool.

Sophie: Great!

Daisy: Oh, and they also asked if I spoke any foreign languages.

Sophie: Languages?

Daisy: Yeah, because I might have to talk to tourists, you know.

Sophie: Oh, right, of course.

Daisy: So that was it really. They showed me the costume I’ll be wearing if I get the job. Sending it over ...

Ollie: Hey, sis, I heard that Brad Pitt started out as a giant chicken too! This could be your big break!

Daisy: Ha, ha, very funny.

Sophie: Take no notice, darling. I’m sure you’ll be a marvellous chicken.

We use reported speech when we want to tell someone what someone said. We usually use a reporting verb (e.g. say, tell, ask, etc.) and then change the tense of what was actually said in direct speech.

So, direct speech is what someone actually says? Like 'I want to know about reported speech'?

Yes, and you report it with a reporting verb.

He said he wanted to know about reported speech.

I said, I want and you changed it to he wanted .

Exactly. Verbs in the present simple change to the past simple; the present continuous changes to the past continuous; the present perfect changes to the past perfect; can changes to could ; will changes to would ; etc.

She said she was having the interview at four o’clock. (Direct speech: ' I’m having the interview at four o’clock.') They said they’d phone later and let me know. (Direct speech: ' We’ll phone later and let you know.')

OK, in that last example, you changed you to me too.

Yes, apart from changing the tense of the verb, you also have to think about changing other things, like pronouns and adverbs of time and place.

'We went yesterday.' > She said they had been the day before. 'I’ll come tomorrow.' > He said he’d come the next day.

I see, but what if you’re reporting something on the same day, like 'We went yesterday'?

Well, then you would leave the time reference as 'yesterday'. You have to use your common sense. For example, if someone is saying something which is true now or always, you wouldn’t change the tense.

'Dogs can’t eat chocolate.' > She said that dogs can’t eat chocolate. 'My hair grows really slowly.' > He told me that his hair grows really slowly.

What about reporting questions?

We often use ask + if/whether , then change the tenses as with statements. In reported questions we don’t use question forms after the reporting verb.

'Do you have any experience working with people?' They asked if I had any experience working with people. 'What acting have you done?' They asked me what acting I had done .

Is there anything else I need to know about reported speech?

One thing that sometimes causes problems is imperative sentences.

You mean like 'Sit down, please' or 'Don’t go!'?

Exactly. Sentences that start with a verb in direct speech need a to + infinitive in reported speech.

She told him to be good. (Direct speech: 'Be good!') He told them not to forget. (Direct speech: 'Please don’t forget.')

OK. Can I also say 'He asked me to sit down'?

Yes. You could say 'He told me to …' or 'He asked me to …' depending on how it was said.

OK, I see. Are there any more reporting verbs?

Yes, there are lots of other reporting verbs like promise , remind , warn , advise , recommend , encourage which you can choose, depending on the situation. But say , tell and ask are the most common.

Great. I understand! My teacher said reported speech was difficult.

And I told you not to worry!

Check your grammar: matching

Check your grammar: error correction, check your grammar: gap fill, worksheets and downloads.

What was the most memorable conversation you had yesterday? Who were you talking to and what did they say to you?

Sign up to our newsletter for LearnEnglish Teens

We will process your data to send you our newsletter and updates based on your consent. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the "unsubscribe" link at the bottom of every email. Read our privacy policy for more information.

Reported Speech in English Grammar

Direct speech, changing the tense (backshift), no change of tenses, question sentences, demands/requests, expressions with who/what/how + infinitive, typical changes of time and place.

- Lingolia Plus English

Introduction

In English grammar, we use reported speech to say what another person has said. We can use their exact words with quotation marks , this is known as direct speech , or we can use indirect speech . In indirect speech , we change the tense and pronouns to show that some time has passed. Indirect speech is often introduced by a reporting verb or phrase such as ones below.

Learn the rules for writing indirect speech in English with Lingolia’s simple explanation. In the exercises, you can test your grammar skills.

When turning direct speech into indirect speech, we need to pay attention to the following points:

- changing the pronouns Example: He said, “ I saw a famous TV presenter.” He said (that) he had seen a famous TV presenter.

- changing the information about time and place (see the table at the end of this page) Example: He said, “I saw a famous TV presenter here yesterday .” He said (that) he had seen a famous TV presenter there the day before .

- changing the tense (backshift) Example: He said, “She was eating an ice-cream at the table where you are sitting .” He said (that) she had been eating an ice-cream at the table where I was sitting .

If the introductory clause is in the simple past (e.g. He said ), the tense has to be set back by one degree (see the table). The term for this in English is backshift .

The verbs could, should, would, might, must, needn’t, ought to, used to normally do not change.

If the introductory clause is in the simple present , however (e.g. He says ), then the tense remains unchanged, because the introductory clause already indicates that the statement is being immediately repeated (and not at a later point in time).

In some cases, however, we have to change the verb form.

When turning questions into indirect speech, we have to pay attention to the following points:

- As in a declarative sentence, we have to change the pronouns, the time and place information, and set the tense back ( backshift ).

- Instead of that , we use a question word. If there is no question word, we use whether / if instead. Example: She asked him, “ How often do you work?” → She asked him how often he worked. He asked me, “Do you know any famous people?” → He asked me if/whether I knew any famous people.

- We put the subject before the verb in question sentences. (The subject goes after the auxiliary verb in normal questions.) Example: I asked him, “ Have you met any famous people before?” → I asked him if/whether he had met any famous people before.

- We don’t use the auxiliary verb do for questions in indirect speech. Therefore, we sometimes have to conjugate the main verb (for third person singular or in the simple past ). Example: I asked him, “What do you want to tell me?” → I asked him what he wanted to tell me.

- We put the verb directly after who or what in subject questions. Example: I asked him, “ Who is sitting here?” → I asked him who was sitting there.

We don’t just use indirect questions to report what another person has asked. We also use them to ask questions in a very polite manner.

When turning demands and requests into indirect speech, we only need to change the pronouns and the time and place information. We don’t have to pay attention to the tenses – we simply use an infinitive .

If it is a negative demand, then in indirect speech we use not + infinitive .

To express what someone should or can do in reported speech, we leave out the subject and the modal verb and instead we use the construction who/what/where/how + infinitive.

Say or Tell?

The words say and tell are not interchangeable. say = say something tell = say something to someone

How good is your English?

Find out with Lingolia’s free grammar test

Take the test!

Maybe later

The Reported Speech

Table of Contents

What is reported speech.

Reported speech is when you tell somebody what you or another person said before. When reporting a speech, some changes are necessary.

For example, the statement:

- Jane said she was waiting for her mom .

is a reported speech, whereas:

- Jane said, “I’m waiting for my mom.”

is a direct speech.

Reported speech is also referred to as indirect speech or indirect discourse .

Before explaining how to report a discourse, let us first distinguish between direct speech and reported speech .

Direct speech vs reported speech

1. We use direct speech to quote a speaker’s exact words. We put their words within quotation marks. We add a reporting verb such as “he said” or “she asked” before or after the quote.

- He said, “I am happy.”

2. Reported speech is a way of reporting what someone said without using quotation marks. We do not necessarily report the speaker”‘s exact words. Some changes are necessary: the time expressions, the tense of the verbs, and the demonstratives.

- He said that he was happy.

More examples:

Different types of reported speech

When you use reported speech, you either report:

- Requests/commands

- Other types

A. Reporting statements

When transforming statements, check whether you have to change:

- place and time expression

1- Pronouns

In reported speech, you often have to change the pronoun depending on who says what.

She says, “My dad likes roast chicken.” => She says that her dad likes roast chicken.

- If the sentence starts in the present, there is no backshift of tenses in reported speech.

- If the sentence starts in the past, there is often a backshift of tenses in reported speech.

No backshift

Do not change the tense if the introductory clause (i.e., the reporting verb) is in the present tense (e. g. He says ). Note, however, that you might have to change the form of the present tense verb (3rd person singular).

- He says, “I write poems.” => He says that he writes English.

You must change the tense if the introductory clause (i.e., the reporting verb) is in the past tense (e. g. He said ).

- He said, “I am happy.”=> He said that he was happy.

Examples of the main changes in verb tense :

3. Modal verbs

The modal verbs could, should, would, might, needn’t, ought to, and used to do not normally change.

- He said: “She might be right.” => He said that she might be right.

- He told her: “You needn’t see a doctor.” => He told her that she needn’t see a doctor.

Other modal verbs such as can, shall, will, must, and ma y change:

4- Place, demonstratives, and time expressions

Place, demonstratives, and time expressions change if the context of the reported statement (i.e. the location and/or the period of time) is different from that of the direct speech.

In the following table, you will find the different changes of place; demonstratives, and time expressions.

B. Reporting Questions

When transforming questions, check whether you have to change:

- The pronouns

- The place and time expressions

- The tenses (backshift)

Also, note that you have to:

- transform the question into an indirect question

- use the question word ( where, when, what, how ) or if / whether

>> EXERCISE ON REPORTING QUESTIONS <<

C. Reporting requests/commands

When transforming requests and commands, check whether you have to change:

- place and time expressions

- She said, “Sit down.” – She asked me to sit down.

- She said, “don’t be lazy” – She asked me not to be lazy

D. Other transformations

- Expressions of advice with must , should, and ought are usually reported using advise / urge . Example: “You must read this book.” He advised/urged me to read that book.

- The expression let’s is usually reported using suggest . In this case, there are two possibilities for reported speech: gerund or statement with should . Example : “Let’s go to the cinema.” 1. He suggested going to the cinema. 2. He suggested that we should go to the cinema.

Main clauses connected with and/but

If two complete main clauses are connected with and or but , put that after the conjunction.

- He said, “I saw her but she didn’t see me.=> He said that he had seen her but that she hadn’t seen him.

If the subject is dropped in the second main clause (the conjunction is followed by a verb), do not use that .

- She said, “I am a nurse and work in a hospital.=> He said that she was a nurse and worked in a hospital.

punctuation rules of the reported speech

Direct speech:

We normally add a comma between the reporting verbs (e.g., she/he said, reported, he replied, etc.) and the reported clause in direct speech. The original speaker”s words are put between inverted commas, either single (“…”) or double (“…”).

- She said, “I wasn’t ready for the competition”.

Note that we insert the comma within the inverted commas if the reported clause comes first:

- “I wasn’t ready for the competition,” she said.

Indirect speech:

In indirect speech, we don’t put a comma between the reporting verb and the reported clause and we omit the inverted quotes.

- She said that she hadn’t been ready for the competition.

In reported questions and exclamations, we remove the question mark and the exclamation mark.

- She asked him why he looked sad?

- She asked him why he looked sad.

Can we omit that in the reported speech?

Yes, we can omit that after reporting verbs such as he said , he replied , she suggested , etc.

- He said that he could do it. – He said he could do it.

- She replied that she was fed up with his misbehavior. – She replied she was fed up with his misbehavior.

List of reporting verbs

Reported speech requires a reporting verb such as “he said”, she “replied”, etc.

Here is a list of some common reporting verbs:

- Cry (meaning shout)

- Demonstrate

- Hypothesize

- Posit the view that

- Question the view that

- Want to know

In reported speech, we put the words of a speaker in a subordinate clause introduced by a reporting verb such as – “ he said ” and “ she asked “- with the required person and tense adjustments.

Related pages

- Reported speech exercise (mixed)

- Reported speech exercise (questions)

- Reported speech exercise (requests and commands)

- Reported speech lesson

Reported Speech

Hero Images/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Reported speech is the report of one speaker or writer on the words spoken, written, or thought by someone else. Also called reported discourse .

Traditionally, two broad categories of reported speech have been recognized: direct speech (in which the original speaker's words are quoted word for word) and indirect speech (in which the original speaker's thoughts are conveyed without using the speaker's exact words). However, a number of linguists have challenged this distinction, noting (among other things) that there's significant overlap between the two categories. Deborah Tannen, for instance, has argued that "[w] hat is commonly referred to as reported speech or direct quotation in conversation is constructed dialogue ."

Observations

- " Reported speech is not just a particular grammatical form or transformation , as some grammar books might suggest. We have to realize that reported speech represents, in fact, a kind of translation , a transposition that necessarily takes into account two different cognitive perspectives: the point of view of the person whose utterance is being reported, and that of a speaker who is actually reporting that utterance." (Teresa Dobrzyńska, "Rendering Metaphor in Reported Speech," in Relative Points of View: Linguistic Representation of Culture , ed. by Magda Stroińska. Berghahn Books, 2001)

Tannen on the Creation of Dialogue

- "I wish to question the conventional American literal conception of ' reported speech ' and claim instead that uttering dialogue in conversation is as much a creative act as is the creation of dialogue in fiction and drama.

- "The casting of thoughts and speech in dialogue creates particular scenes and characters--and . . . it is the particular that moves readers by establishing and building on a sense of identification between speaker or writer and hearer or reader. As teachers of creative writing exhort neophyte writers, the accurate representation of the particular communicates universality, whereas direct attempts to represent universality often communicate nothing." (Deborah Tannen, Talking Voices: Repetition, Dialogue, and Imagery in Conversational Discourse , 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2007)

Goffman on Reported Speech

- "[Erving] Goffman's work has proven foundational in the investigation of reported speech itself. While Goffman is not in his own work concerned with the analysis of actual instances of interaction (for a critique, see Schlegoff, 1988), it provides a framework for researchers concerned with investigating reported speech in its most basic environment of occurrence: ordinary conversation. . . .

- "Goffman . . . proposed that reported speech is a natural upshot of a more general phenomenon in interaction: shifts of 'footing,' defined as 'the alignment of an individual to a particular utterance . . .' ([ Forms of Talk ,] 1981: 227). Goffman is concerned to break down the roles of speaker and hearer into their constituent parts. . . . [O]ur ability to use reported speech stems from the fact that we can adopt different roles within the 'production format,' and it is one of the many ways in which we constantly change footing as we interact . . .."(Rebecca Clift and Elizabeth Holt, Introduction. Reporting Talk: Reported Speech in Interaction . Cambridge University Press, 2007)

Reported Speech in Legal Contexts

- " [R]eported speech occupies a prominent position in our use of language in the context of the law. Much of what is said in this context has to do with rendering people's sayings: we report the words that accompany other people's doings in order to put the latter in the correct perspective. As a consequence, much of our judiciary system, both in the theory and in the practice of law, turns around the ability to prove or disprove the correctness of a verbal account of a situation. The problem is how to summarize that account, from the initial police report to the final imposed sentence, in legally binding terms, so that it can go 'on the record,' that is to say, be reported in its definitive, forever immutable form as part of a 'case' in the books." (Jacob Mey, When Voices Clash: A Study in Literary Pragmatics . Walter de Gruyter, 1998)

- Constructed Dialogue in Storytelling and Conversation

- Cooperative Overlap in Conversation

- Dialogue Guide Definition and Examples

- What Are Reporting Verbs in English Grammar?

- The Power of Indirectness in Speaking and Writing

- Definition and Examples of "Exophora" in English Grammar

- Direct Speech Definition and Examples

- How to Use Indirect Quotations in Writing for Complete Clarity

- Politeness Strategies in English Grammar

- Speech Act Theory

- The Meaning of Innuendo

- Conversation Defined

- Dialogue Definition, Examples and Observations

- What Is Relevance Theory in Terms of Communication?

- Speech Acts in Linguistics

- Verbal Hedge: Definition and Examples

Direct and Indirect Speech: Useful Rules and Examples

Are you having trouble understanding the difference between direct and indirect speech? Direct speech is when you quote someone’s exact words, while indirect speech is when you report what someone said without using their exact words. This can be a tricky concept to grasp, but with a little practice, you’ll be able to use both forms of speech with ease.

Direct and Indirect Speech

When someone speaks, we can report what they said in two ways: direct speech and indirect speech. Direct speech is when we quote the exact words that were spoken, while indirect speech is when we report what was said without using the speaker’s exact words. Here’s an example:

Direct speech: “I love pizza,” said John. Indirect speech: John said that he loved pizza.

Using direct speech can make your writing more engaging and can help to convey the speaker’s tone and emotion. However, indirect speech can be useful when you want to summarize what someone said or when you don’t have the exact words that were spoken.

To change direct speech to indirect speech, you need to follow some rules. Firstly, you need to change the tense of the verb in the reported speech to match the tense of the reporting verb. Secondly, you need to change the pronouns and adverbs in the reported speech to match the new speaker. Here’s an example:

Direct speech: “I will go to the park,” said Sarah. Indirect speech: Sarah said that she would go to the park.

It’s important to note that when you use indirect speech, you need to use reporting verbs such as “said,” “told,” or “asked” to indicate who is speaking. Here’s an example:

Direct speech: “What time is it?” asked Tom. Indirect speech: Tom asked what time it was.

In summary, understanding direct and indirect speech is crucial for effective communication and writing. Direct speech can be used to convey the speaker’s tone and emotion, while indirect speech can be useful when summarizing what someone said. By following the rules for changing direct speech to indirect speech, you can accurately report what was said while maintaining clarity and readability in your writing.

Differences between Direct and Indirect Speech

When it comes to reporting speech, there are two ways to go about it: direct and indirect speech. Direct speech is when you report someone’s exact words, while indirect speech is when you report what someone said without using their exact words. Here are some of the key differences between direct and indirect speech:

Change of Pronouns

In direct speech, the pronouns used are those of the original speaker. However, in indirect speech, the pronouns have to be changed to reflect the perspective of the reporter. For example:

- Direct speech: “I am going to the store,” said John.

- Indirect speech: John said he was going to the store.

In the above example, the pronoun “I” changes to “he” in indirect speech.

Change of Tenses

Another major difference between direct and indirect speech is the change of tenses. In direct speech, the verb tense used is the same as that used by the original speaker. However, in indirect speech, the verb tense may change depending on the context. For example:

- Direct speech: “I am studying for my exams,” said Sarah.

- Indirect speech: Sarah said she was studying for her exams.

In the above example, the present continuous tense “am studying” changes to the past continuous tense “was studying” in indirect speech.

Change of Time and Place References

When reporting indirect speech, the time and place references may also change. For example:

- Direct speech: “I will meet you at the park tomorrow,” said Tom.

- Indirect speech: Tom said he would meet you at the park the next day.

In the above example, “tomorrow” changes to “the next day” in indirect speech.

Overall, it is important to understand the differences between direct and indirect speech to report speech accurately and effectively. By following the rules of direct and indirect speech, you can convey the intended message of the original speaker.

Converting Direct Speech Into Indirect Speech

When you need to report what someone said in your own words, you can use indirect speech. To convert direct speech into indirect speech, you need to follow a few rules.

Step 1: Remove the Quotation Marks

The first step is to remove the quotation marks that enclose the relayed text. This is because indirect speech does not use the exact words of the speaker.

Step 2: Use a Reporting Verb and a Linker

To indicate that you are reporting what someone said, you need to use a reporting verb such as “said,” “asked,” “told,” or “exclaimed.” You also need to use a linker such as “that” or “whether” to connect the reporting verb to the reported speech.

For example:

- Direct speech: “I love ice cream,” said Mary.

- Indirect speech: Mary said that she loved ice cream.

Step 3: Change the Tense of the Verb

When you use indirect speech, you need to change the tense of the verb in the reported speech to match the tense of the reporting verb.

- Indirect speech: John said that he was going to the store.

Step 4: Change the Pronouns

You also need to change the pronouns in the reported speech to match the subject of the reporting verb.

- Direct speech: “Are you busy now?” Tina asked me.

- Indirect speech: Tina asked whether I was busy then.

By following these rules, you can convert direct speech into indirect speech and report what someone said in your own words.

Converting Indirect Speech Into Direct Speech

Converting indirect speech into direct speech involves changing the reported speech to its original form as spoken by the speaker. Here are the steps to follow when converting indirect speech into direct speech:

- Identify the reporting verb: The first step is to identify the reporting verb used in the indirect speech. This will help you determine the tense of the direct speech.

- Change the pronouns: The next step is to change the pronouns in the indirect speech to match the person speaking in the direct speech. For example, if the indirect speech is “She said that she was going to the store,” the direct speech would be “I am going to the store,” if you are the person speaking.

- Change the tense: Change the tense of the verbs in the indirect speech to match the tense of the direct speech. For example, if the indirect speech is “He said that he would visit tomorrow,” the direct speech would be “He says he will visit tomorrow.”

- Remove the reporting verb and conjunction: In direct speech, there is no need for a reporting verb or conjunction. Simply remove them from the indirect speech to get the direct speech.

Here is an example to illustrate the process:

Indirect Speech: John said that he was tired and wanted to go home.

Direct Speech: “I am tired and want to go home,” John said.

By following these steps, you can easily convert indirect speech into direct speech.

Examples of Direct and Indirect Speech

Direct and indirect speech are two ways to report what someone has said. Direct speech reports the exact words spoken by a person, while indirect speech reports the meaning of what was said. Here are some examples of both types of speech:

Direct Speech Examples

Direct speech is used when you want to report the exact words spoken by someone. It is usually enclosed in quotation marks and is often used in dialogue.

- “I am going to the store,” said Sarah.

- “It’s a beautiful day,” exclaimed John.

- “Please turn off the lights,” Mom told me.

- “I will meet you at the library,” said Tom.

- “We are going to the beach tomorrow,” announced Mary.

Indirect Speech Examples

Indirect speech, also known as reported speech, is used to report what someone said without using their exact words. It is often used in news reports, academic writing, and in situations where you want to paraphrase what someone said.

Here are some examples of indirect speech:

- Sarah said that she was going to the store.

- John exclaimed that it was a beautiful day.

- Mom told me to turn off the lights.

- Tom said that he would meet me at the library.

- Mary announced that they were going to the beach tomorrow.

In indirect speech, the verb tense may change to reflect the time of the reported speech. For example, “I am going to the store” becomes “Sarah said that she was going to the store.” Additionally, the pronouns and possessive adjectives may also change to reflect the speaker and the person being spoken about.

Overall, both direct and indirect speech are important tools for reporting what someone has said. By using these techniques, you can accurately convey the meaning of what was said while also adding your own interpretation and analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is direct and indirect speech?

Direct and indirect speech refer to the ways in which we communicate what someone has said. Direct speech involves repeating the exact words spoken, using quotation marks to indicate that you are quoting someone. Indirect speech, on the other hand, involves reporting what someone has said without using their exact words.

How do you convert direct speech to indirect speech?

To convert direct speech to indirect speech, you need to change the tense of the verbs, pronouns, and time expressions. You also need to introduce a reporting verb, such as “said,” “told,” or “asked.” For example, “I love ice cream,” said Mary (direct speech) can be converted to “Mary said that she loved ice cream” (indirect speech).

What is the difference between direct speech and indirect speech?

The main difference between direct speech and indirect speech is that direct speech uses the exact words spoken, while indirect speech reports what someone has said without using their exact words. Direct speech is usually enclosed in quotation marks, while indirect speech is not.

What are some examples of direct and indirect speech?

Some examples of direct speech include “I am going to the store,” said John and “I love pizza,” exclaimed Sarah. Some examples of indirect speech include John said that he was going to the store and Sarah exclaimed that she loved pizza .

What are the rules for converting direct speech to indirect speech?

The rules for converting direct speech to indirect speech include changing the tense of the verbs, pronouns, and time expressions. You also need to introduce a reporting verb and use appropriate reporting verbs such as “said,” “told,” or “asked.”

What is a summary of direct and indirect speech?

Direct and indirect speech are two ways of reporting what someone has said. Direct speech involves repeating the exact words spoken, while indirect speech reports what someone has said without using their exact words. To convert direct speech to indirect speech, you need to change the tense of the verbs, pronouns, and time expressions and introduce a reporting verb.

You might also like:

- List of Adjectives

- Predicate Adjective

- Superlative Adjectives

Related Posts:

This website is AMNAZING

MY NAAMEE IS KISHU AND I WANTED TO TELL THERE ARE NO EXERCISES AVAILLABLEE BY YOUR WEBSITE PLEASE ADD THEM SSOON FOR OUR STUDENTS CONVIENCE IM A EIGHT GRADER LOVED YOUR EXPLABATIO

sure cries l miss my friend

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Reported speech: indirect speech

Indirect speech focuses more on the content of what someone said rather than their exact words. In indirect speech , the structure of the reported clause depends on whether the speaker is reporting a statement, a question or a command.

Indirect speech: reporting statements

Indirect reports of statements consist of a reporting clause and a that -clause. We often omit that , especially in informal situations:

The pilot commented that the weather had been extremely bad as the plane came in to land. (The pilot’s words were: ‘The weather was extremely bad as the plane came in to land.’ )

I told my wife I didn’t want a party on my 50th birthday. ( that -clause without that ) (or I told my wife that I didn’t want a party on my 50th birthday .)

Indirect speech: reporting questions

Reporting yes-no questions and alternative questions.

Indirect reports of yes-no questions and questions with or consist of a reporting clause and a reported clause introduced by if or whether . If is more common than whether . The reported clause is in statement form (subject + verb), not question form:

She asked if [S] [V] I was Scottish. (original yes-no question: ‘Are you Scottish?’ )

The waiter asked whether [S] we [V] wanted a table near the window. (original yes-no question: ‘Do you want a table near the window? )

He asked me if [S] [V] I had come by train or by bus. (original alternative question: ‘Did you come by train or by bus?’ )

Questions: yes-no questions ( Are you feeling cold? )

Reporting wh -questions

Indirect reports of wh -questions consist of a reporting clause, and a reported clause beginning with a wh -word ( who, what, when, where, why, how ). We don’t use a question mark:

He asked me what I wanted.

Not: He asked me what I wanted?

The reported clause is in statement form (subject + verb), not question form:

She wanted to know who [S] we [V] had invited to the party.

Not: … who had we invited …

Who , whom and what

In indirect questions with who, whom and what , the wh- word may be the subject or the object of the reported clause:

I asked them who came to meet them at the airport. ( who is the subject of came ; original question: ‘Who came to meet you at the airport?’ )

He wondered what the repairs would cost. ( what is the object of cost ; original question: ‘What will the repairs cost?’ )

She asked us what [S] we [V] were doing . (original question: ‘What are you doing?’ )

Not: She asked us what were we doing?

When , where , why and how

We also use statement word order (subject + verb) with when , where, why and how :

I asked her when [S] it [V] had happened (original question: ‘When did it happen?’ ).

Not: I asked her when had it happened?

I asked her where [S] the bus station [V] was . (original question: ‘Where is the bus station?’ )

Not: I asked her where was the bus station?

The teacher asked them how [S] they [V] wanted to do the activity . (original question: ‘How do you want to do the activity?’ )

Not: The teacher asked them how did they want to do the activity?

Questions: wh- questions

Indirect speech: reporting commands

Indirect reports of commands consist of a reporting clause, and a reported clause beginning with a to -infinitive:

The General ordered the troops to advance . (original command: ‘Advance!’ )

The chairperson told him to sit down and to stop interrupting . (original command: ‘Sit down and stop interrupting!’ )

We also use a to -infinitive clause in indirect reports with other verbs that mean wanting or getting people to do something, for example, advise, encourage, warn :

They advised me to wait till the following day. (original statement: ‘You should wait till the following day.’ )

The guard warned us not to enter the area. (original statement: ‘You must not enter the area.’ )

Verbs followed by a to -infinitive

Indirect speech: present simple reporting verb

We can use the reporting verb in the present simple in indirect speech if the original words are still true or relevant at the time of reporting, or if the report is of something someone often says or repeats:

Sheila says they’re closing the motorway tomorrow for repairs.

Henry tells me he’s thinking of getting married next year.

Rupert says dogs shouldn’t be allowed on the beach. (Rupert probably often repeats this statement.)

Newspaper headlines

We often use the present simple in newspaper headlines. It makes the reported speech more dramatic:

JUDGE TELLS REPORTER TO LEAVE COURTROOM

PRIME MINISTER SAYS FAMILIES ARE TOP PRIORITY IN TAX REFORM

Present simple ( I work )

Reported speech

Reported speech: direct speech

Indirect speech: past continuous reporting verb

In indirect speech, we can use the past continuous form of the reporting verb (usually say or tell ). This happens mostly in conversation, when the speaker wants to focus on the content of the report, usually because it is interesting news or important information, or because it is a new topic in the conversation:

Rory was telling me the big cinema in James Street is going to close down. Is that true?

Alex was saying that book sales have gone up a lot this year thanks to the Internet.

‘Backshift’ refers to the changes we make to the original verbs in indirect speech because time has passed between the moment of speaking and the time of the report.

In these examples, the present ( am ) has become the past ( was ), the future ( will ) has become the future-in-the-past ( would ) and the past ( happened ) has become the past perfect ( had happened ). The tenses have ‘shifted’ or ‘moved back’ in time.

The past perfect does not shift back; it stays the same:

Modal verbs

Some, but not all, modal verbs ‘shift back’ in time and change in indirect speech.

We can use a perfect form with have + - ed form after modal verbs, especially where the report looks back to a hypothetical event in the past:

He said the noise might have been the postman delivering letters. (original statement: ‘The noise might be the postman delivering letters.’ )

He said he would have helped us if we’d needed a volunteer. (original statement: ‘I’ll help you if you need a volunteer’ or ‘I’d help you if you needed a volunteer.’ )

Used to and ought to do not change in indirect speech:

She said she used to live in Oxford. (original statement: ‘I used to live in Oxford.’ )

The guard warned us that we ought to leave immediately. (original statement: ‘You ought to leave immediately.’ )

No backshift

We don’t need to change the tense in indirect speech if what a person said is still true or relevant or has not happened yet. This often happens when someone talks about the future, or when someone uses the present simple, present continuous or present perfect in their original words:

He told me his brother works for an Italian company. (It is still true that his brother works for an Italian company.)

She said she ’s getting married next year. (For the speakers, the time at the moment of speaking is ‘this year’.)

He said he ’s finished painting the door. (He probably said it just a short time ago.)

She promised she ’ll help us. (The promise applies to the future.)

Indirect speech: changes to pronouns

Changes to personal pronouns in indirect reports depend on whether the person reporting the speech and the person(s) who said the original words are the same or different.

Indirect speech: changes to adverbs and demonstratives

We often change demonstratives ( this, that ) and adverbs of time and place ( now, here, today , etc.) because indirect speech happens at a later time than the original speech, and perhaps in a different place.

Typical changes to demonstratives, adverbs and adverbial expressions

Indirect speech: typical errors.

The word order in indirect reports of wh- questions is the same as statement word order (subject + verb), not question word order:

She always asks me where [S] [V] I am going .

Not: She always asks me where am I going .

We don’t use a question mark when reporting wh- questions:

I asked him what he was doing.

Not: I asked him what he was doing?

Word of the Day

If you are on hold when using the phone, you are waiting to speak to someone.

Searching out and tracking down: talking about finding or discovering things

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

To add ${headword} to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add ${headword} to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Reported Speech – Free ESL Lesson Plan

Our new ESL Lesson Plan , “Introduction to Reported Speech,” helps students understand how to describe someone else’s words. Learning how to transform direct speech into reported speech is essential to everyday communication, and students will certainly benefit from this engaging lesson that includes clear descriptions, examples and practice opportunities. Keep reading to find out what to expect and how to teach it virtually or in-person.

When should you teach “Introduction to Reported Speech”?

“Introduction to Reported Speech” is an ESL lesson plan download aimed at students with advanced proficiency levels. To fully grasp the material, students must be very comfortable with changing verbs between various tenses including the perfect, simple and continuous tenses.

You can download the lesson plan here:

How to teach the “Introduction to Reported Speech” lesson

To help students understand this concept, this lesson breaks down the components of transforming direct speech into reported speech: pronouns, tenses, time and the removal of quotation marks. It also spends a substantial portion of slides going over how to backshift by “going back a tense” and how to employ possessive adjectives successfully.

The slides are playful and illustrated with many pictures and fun examples to keep your students engaged and motivated.

If you are looking for even more information on how to teach this lesson plan on reported speech, be sure to download a free Off2Class account . You will gain access to teacher notes that will guide and prepare you.

Don’t forget about our free lessons!

If you enjoyed this ESL lesson plan download, there are 149 more available here . The lesson plans are designed to save you time . Also, let us know what kind of lessons you are looking for from Off2Class. More than anything, we love hearing from our teachers. So leave your general suggestions, lesson plan ideas, teaching philosophy or anything related in the comments below. Happy teaching!

One Comment

May 11, 2024 at 11:10 am

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email is never published nor shared. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me by email when the comment gets approved.

Back to Lesson Plan Downloads

Categories:, more lesson plan downloads.

ESL Worksheets for Teachers

Check out our selection of worksheets filed under grammar: reported speech. use the search filters on the left to refine your search..

FILTER LESSONS

Customised lessons

Worksheet type

Intermediate (B1-B2)

In this lesson, students learn language related to government and human rights by discussing control of technology and information. The control of technology and information is important to lawyers working in diverse fields, ranging from human rights to business.

by Susan Iannuzzi

This worksheet teaches reported speech . The rules for changing the tense of the verb from direct speech are presented and practised. The worksheet is suitable for both classroom practice and self-study.

Pre-intermediate (A2-B1)

In this lesson, students read an article about pros and cons of Sweden's six-hour work day. The 5-page worksheet includes a grammar activity on reported speech.

The first of a two-part lesson plan that looks at the causes and impact of stress in the workplace. Students read about how stress is affecting small and medium-sized businesses in the UK. The lesson rounds off with a grammar exercise on reported speech in which students complete a stressful negotiation dialogue using the target language structures.

This lesson is based on an article about a woman from New Zealand who became an 'accidental millionaire' when her partner's bank mistakenly increased his overdraft limit by nearly £5 million ($8 million). There is plenty of crime and punishment vocabulary as well as banking terms and expressions (which should be familiar to students who have done the worksheet Banking ). In the grammar section, there is an exercise on the past perfect simple , which is used throughout the article. Use this worksheet with a strong intermediate or upper intermediate class. Important notes are included in the key.

Upper-intermediate (B2-C1)

This lesson teaches the vocabulary and grammar necessary for taking meeting minutes in English. Students listen to a dialogue of a meeting and read an extract from the minutes. After studying the vocabulary and grammar used in the text, they practise reporting statements and taking minutes.

This lesson is based on an article on the nascent space tourism industry. The text focuses on the different companies that will be operating in this market, including Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, as well as the future costs and environmental impact of commercial space flights. In the grammar section of the worksheets, reported statements and questions are studied and practised. At the end of the lesson, students discuss whether they believe space tourism could become mass market.

The theme of this lesson is prediction. Students read an amusing article on eight embarrassing predictions made by well-respected experts at different periods of modern history. In the grammar exercises, structures for reporting a prediction made in the past are learnt and the use and omission of the definite article for talking in general is studied. At the end of the lesson, students practise making and reporting predictions.

- All topics A-Z

- Grammar

- Vocabulary

- Speaking

- Reading

- Listening

- Writing

- Pronunciation

- Virtual Classroom

- Worksheets by season

- 600 Creative Writing Prompts

- Warmers, fillers & ice-breakers

- Coloring pages to print

- Flashcards

- Classroom management worksheets

- Emergency worksheets

- Revision worksheets

- Resources we recommend

- Copyright 2007-2021 пїЅ

- Submit a worksheet

- Mobile version

Advertisement

Content Validity of the Modified Functional Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (f-SARA) Instrument in Spinocerebellar Ataxia

- Open access

- Published: 07 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Michele Potashman 1 ,

- Katja Rudell 2 ,

- Ivanna Pavisic 2 ,

- Naomi Suminski 2 ,

- Rinchen Doma 2 ,

- Maggie Heinrich 2 ,

- Linda Abetz-Webb 3 ,

- Melissa Wolfe Beiner 1 ,

- Sheng-Han Kuo 4 ,

- Liana S. Rosenthal 5 ,

- Theresa Zesiwicz 6 ,

- Terry D. Fife 7 ,

- Bart P. van de Warrenburg 8 ,

- Giovanni Ristori 9 ,

- Matthis Synofzik 10 ,

- Susan Perlman 11 ,

- Jeremy D. Schmahmann 12 &

- Gilbert L’Italien 1

481 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The functional Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (f-SARA) assesses Gait, Stance, Sitting, and Speech. It was developed as a potentially clinically meaningful measure of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) progression for clinical trial use. Here, we evaluated content validity of the f-SARA. Qualitative interviews were conducted among individuals with SCA1 ( n = 1) and SCA3 ( n = 6) and healthcare professionals (HCPs) with SCA expertise (USA, n = 5; Europe, n = 3). Interviews evaluated symptoms and signs of SCA and relevance of f-SARA concepts for SCA. HCP cognitive debriefing was conducted. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, coded, and analyzed by ATLAS.TI software. Individuals with SCA1 and 3 reported 85 symptoms, signs, and impacts of SCA. All indicated difficulties with walking, stance, balance, speech, fatigue, emotions, and work. All individuals with SCA1 and 3 considered Gait, Stance, and Speech relevant f-SARA concepts; 3 considered Sitting relevant (42.9%). All HCPs considered Gait and Speech relevant; 5 (62.5%) indicated Stance was relevant. Sitting was considered a late-stage disease indicator. Most HCPs suggested inclusion of appendicular items would enhance clinical relevance. Cognitive debriefing supported clarity and comprehension of f-SARA. Maintaining current abilities on f-SARA items for 1 year was considered meaningful for most individuals with SCA1 and 3. All HCPs considered meaningful changes as stability in f-SARA score over 1–2 years, 1–2-point change in total f-SARA score, and deviation from natural history. These results support content validity of f-SARA for assessing SCA disease progression in clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions on Psychological and Cognitive Health Outcomes Compared with Other Forms of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis

Management of functional neurological disorder

Clinical Evidence of Exercise Benefits for Stroke

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) are a dominantly inherited heterogeneous group of rare disorders that cause progressive neurodegeneration of the cerebellum and spinal cord [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Almost 50 different SCA genotypes have been identified, each with a distinct pathophysiology and clinical profile. Of these, SCA types 1, 2, 3, and 6 have been considered the most common worldwide [ 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The recent identification and characterization of the newly discovered SCA27b variant has suggested that this may account for a substantial proportion of previously unexplained late-onset dominant and sporadic cerebellar ataxias, though its global prevalence remains to be established [ 4 , 5 , 8 , 9 ]. Whereas symptom manifestation and disease trajectory vary across SCA types, all share the cardinal features of cerebellar dysfunction, which includes progressive lack of voluntary motor coordination, gait impairment, loss of balance and associated falls, and speech and swallowing difficulties [ 1 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. In addition to affecting physical functioning, symptoms impair independent ability to conduct activities of daily living (ADLs), which increases reliance on caregivers and severely impacts patient quality of life [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Patient life expectancy varies widely between SCA types [ 7 , 17 ].

To reliably measure the severity and progression of cerebellar ataxia, notably SCA, the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) was developed by a panel of expert clinicians to provide semi-quantitative scoring of patient gross and fine motor function [ 18 ]. The SARA evaluates 8 items concerning gait, stance, sitting, speech, and upper and lower limb coordination. It provides a combined total score that indicates disease severity, with higher scores denoting more severe disease. A number of patient registries and clinical studies have used the SARA as an outcome measure to date to assess the impact of pharmacologic and/or non-pharmacologic therapies on SCA symptom progression [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Recently, the SARA was modified to serve as a primary endpoint in a randomized clinical trial of individuals with SCA [ 33 ]. Accounting for feedback from discussions with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and upon analysis of US natural history data from the Clinical Research Consortium for the Study of Cerebellar Ataxia and a phase 2 study of troriluzole [ 34 ], removal of the 4 appendicular items from the original SARA was implemented. These items were not considered sensitive for measurement of meaningful change in a clinical trial setting conducted over 48 weeks.

The resulting modification of the SARA, the functional SARA (f-SARA), is a 4-item scale that assesses Gait, Stance, Sitting, and Speech. Each of the 4 items is rated on an ordinal scale from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates normal or unimpaired function, and higher responses indicate progressive impairment. The total f-SARA score is the sum of the 4 individual items (16 points).

When developing or adapting a clinical outcome assessment (COA), it is important to collect patient perspectives on their lived experience of the disease of interest, as well as clinical perspectives on the temporal progression of the disease, to support the content validity of the measure [ 35 , 36 ]. In addition, cognitive debriefing and discussions centered around what constitutes meaningful changes in the context of the disease are important steps in establishing the content validity of a new or modified COA. These discussions ensure that the measure has the potential to assess meaningful changes in patient-experienced symptoms reliably [ 35 , 36 ].

The f-SARA was developed to support the primary endpoint in a phase 3 study evaluating the efficacy of troriluzole on ataxia symptoms in individuals with SCA (NCT03701399; trial registration date: October 8, 2018), but the content validity of the items that comprise the f-SARA (i.e., comprehensiveness, relevance, comprehension, and understandability) remains to be determined. To address this need, we conducted qualitative interviews with individuals with SCA and healthcare professionals (HCPs) with expertise in treating SCA to assess the content validity of the f-SARA and to explore what constitutes clinically meaningful changes in SCA symptoms.

Patients and Methods

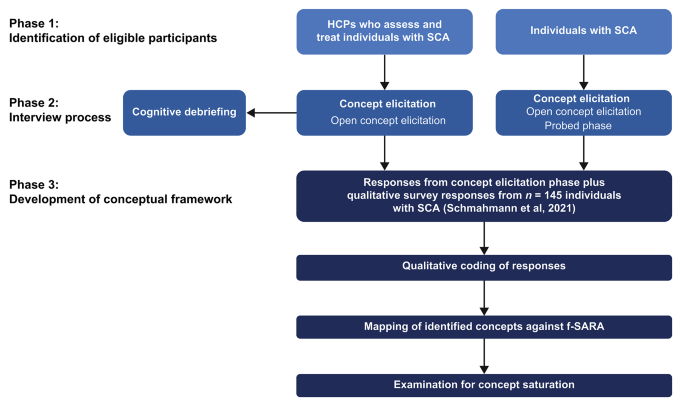

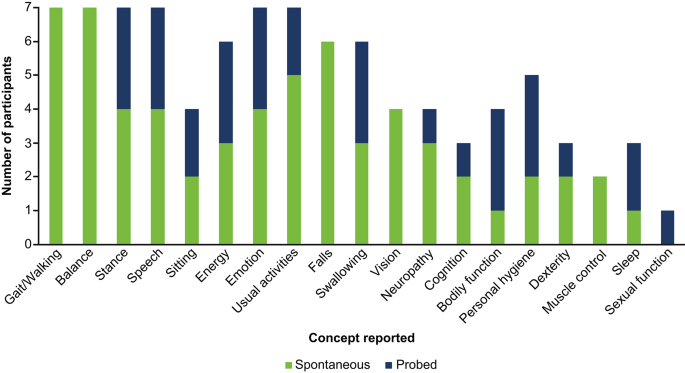

Study design.