- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Virtual Issue archive

- The Pitelka Award

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Behavioral Ecology

- About the International Society for Behavioral Ecology

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, what is hbe, a systematic overview of current research, hbe: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and open questions, supplementary material, human behavioral ecology: current research and future prospects.

Forum editor: Sue Healy

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Daniel Nettle, Mhairi A. Gibson, David W. Lawson, Rebecca Sear, Human behavioral ecology: current research and future prospects, Behavioral Ecology , Volume 24, Issue 5, September-October 2013, Pages 1031–1040, https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/ars222

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Human behavioral ecology (HBE) is the study of human behavior from an adaptive perspective. It focuses in particular on how human behavior varies with ecological context. Although HBE is a thriving research area, there has not been a major review published in a journal for over a decade, and much has changed in that time. Here, we describe the main features of HBE as a paradigm and review HBE research published since the millennium. We find that the volume of HBE research is growing rapidly, and its composition is changing in terms of topics, study populations, methodology, and disciplinary affiliations of authors. We identify the major strengths of HBE research as its vitality, clear predictions, empirical fruitfulness, broad scope, conceptual coherence, ecological validity, increasing methodological rigor, and topical innovation. Its weaknesses include a relative isolation from the rest of behavioral ecology and evolutionary biology and a somewhat limited current topic base. As HBE continues to grow, there is a major opportunity for it to serve as a bridge between the natural and social sciences and help unify disparate disciplinary approaches to human behavior. HBE also faces a number of open questions, such as how understanding of proximate mechanisms is to be integrated with behavioral ecology’s traditional focus on optimal behavioral strategies, and the causes and extent of maladaptive behavior in humans.

Very soon after behavioral ecology (henceforth BE) emerged as a paradigm in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a tradition of applying behavioral ecological models to human behavior developed. This tradition, henceforth human behavioral ecology (HBE), quickly became an important voice in the human-related sciences, just as BE itself was becoming an established and recognized approach in biology more generally. HBE continues to be an active and innovative area of research. However, it tends not to receive the attention it might, perhaps in part because its adherents are dispersed across a number of different academic disciplines, spanning the life and social sciences. Although there were a number of influential earlier reviews, particularly by Cronk (1991) and Winterhalder and Smith (2000) , there has not been a major review of the HBE literature published in a journal for more than a decade. In this paper, we undertake such a review, with the aim of briefly but systematically characterizing current research activity in HBE, and drawing attention to prospects and issues for the future. The structure of our paper is as follows. In the section “What is HBE?”, we provide a brief overview of the HBE approach to human behavior. The section “A systematic overview of current research” presents our review methodology and briefly describes what we found. We argue that the HBE research published in the period since 2000 represents a distinct phase in the paradigm’s development, with a number of novel trends that require comment. Finally, the section “HBE: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and open questions” presents our reflections on the current state and future prospects of HBE, which we structure in terms of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and open questions.

BE is the investigation of how behavior evolves in relation to ecological conditions ( Davies et al. 2012 ). Empirically, there are 2 arms to this endeavor. One arm is the study of how measurable variation in ecological conditions predicts variation in the behavioral strategies that individuals display, be it at the between-species, between-population, between-individual, or even within-individual level. (Throughout this paper, “ecological conditions” is to be interpreted in its broadest sense, to include the physical and social aspects of the environment, as well as the state of the individual within that environment.). The other arm concerns the fitness consequences of the behavioral strategies that individuals adopt. Because fitness—the number of descendants left by individuals following a strategy at a point many generations in the future—cannot usually be measured within a study, this generally means measuring the consequences of behavioral strategies in some more immediate proxy currency related to fitness, such as survival, mating success, or energetic return. The 2 arms of BE are tightly linked to one another; the fitness consequences of some behavioral strategy will differ according to the prevailing ecological conditions. Moreover, central to BE is the adaptationist stance. That is, we expect to see, in the natural world, organisms whose behavior is close to optimal in terms of maximizing their fitness given the ecological conditions that they face. This expectation is used as a hypothesis-generating engine about which behaviors we will see under which ecological conditions. The justification for the adaptationist stance is the power of natural selection. Selection, other things being equal, favors genes that contribute to the development of individuals who are prone to behaving optimally across the kinds of environments in which they have to live ( Grafen 2006 ). Note that this does not imply that behavioral strategies are under direct genetic control. On the contrary, selection favors various mechanisms for plasticity, such as individual and social learning, exactly because they allow individuals to acquire locally adaptive behavioral strategies over a range of environments ( Scheiner 1993 ; Pigliucci 2005 ), and it is these plastic mechanisms that are often in immediate control of behavioral decisions. However, the capacity for plasticity is ultimately dependent on genotype, and plasticity is deployed in the service of genetic fitness maximization.

BE is also characterized by a typical approach, to which actual exemplars of research projects conform to varying degrees. This approach is to formulate simple a priori models of what the individual would gain, in fitness terms, by doing A rather than B, and using these models to make predictions either about how variation in ecological conditions will affect the prevalence of behaviors A and B, or about what the payoffs to individuals doing A and B will be, in some currency related to fitness. These models are usually characterized by the assumption that there are no important phylogenetic or developmental constraints on the range of strategies that individuals are able to adopt and also by a relative agnosticism about exactly how individuals arrive at particular behavioral strategies (i.e., about questions of proximate mechanism as opposed to ultimate function; Mayr 1961 ; Tinbergen 1963 ). The assumptions of no mechanistic constraints coming from the genetic architecture or the neural mechanisms are known, respectively, as the phenotypic gambit ( Grafen 1984 ) and the behavioral gambit ( Fawcett et al. 2012 ). To paraphrase Krebs and Davies (1981 ), “think of the strategies and let the mechanisms look after themselves.” We return to the issue of the validity of the behavioral gambit in particular in section “Open questions.” However, one of the remarkable features of early research in BE (what Owens 2006 calls “the romantic period of BE”) was just how well the observed behavior of animals of many different species was explained by very simple optimality models based on the gambits.

HBE is the study of human behavior from an adaptive perspective. Humans are remarkable for their ability to adapt to new niches much faster than the time required for genetic change ( Laland and Brown 2006 ; Wells and Stock 2007 ; Nettle 2009b ). HBE has been particularly concerned with explaining this rapid adaptation and diversity, and thus, the concept of adaptive phenotypic plasticity has been even more central to HBE than it is to BE in general. HBE represents a rejection of the notion that fundamentally different explanatory approaches are necessary for the study of human behavior as opposed to that of any other animal. Note that this does not imply that humans have no unique cognitive and behavioral mechanisms. On the contrary, they clearly do. Rather, it implies that the general scientific strategy for explaining behavior instantiated in BE remains similar for the human case: understand the fitness costs and benefits given the ecological context, make predictions based on the hypothesis of fitness maximization, and test them. There is a pleasing cyclicity to the development of HBE. BE showed that microeconomic models based on maximization, which had come from the human discipline of economics, could be used at least as a first approximation to predict the behavior of nonhuman animals. HBE imported these principles, enriched from their sojourn in biology by a focus on fitness as the relevant currency, back to humans again.

The first recognizably HBE papers appeared in the 1970s (e.g., Wilmsen 1973 ; Dyson-Hudson and Smith 1978 ). The pioneers were anthropologists, and to a lesser extent archaeologists. A major focus was on explaining foraging patterns in hunting and gathering populations ( Smith 1983 ), though other topics were also represented from the outset ( Cronk 1991 ). The focus on foragers was due to the evolutionary antiquity of this mode of subsistence, as well as these being the populations in which optimal foraging theory was most straightforwardly applicable. However, there is no reason in principle for HBE research to be restricted to such populations. The emphasis in HBE is on human adaptability; humans have mechanisms of adaptive learning and plasticity by virtue of which they can rapidly find adaptive solutions to living in many kinds of environments. Thus, we might expect their behavior to be adaptively patterned in societies of all kinds, not just the types of human society, which have existed for many millennia.

The first phase of HBE lasted through the 1980s ( Borgerhoff Mulder 1988 ). In the second phase, the 1990s, HBE grew rapidly, with Winterhalder and Smith (2000) estimating that there were nearly 300 studies published during the decade. Its focus broadened to encompass more studies from nonforaging subsistence populations, such as horticulturalists and pastoralists (e.g., Borgerhoff Mulder 1990 ), and the use of historical demographic data (e.g., Voland 2000 ; Clarke and Low 2001 ). There were also some pioneering forays into the BE of industrialized populations ( Kaplan 1996 ; Wilson and Daly 1997 ). The 1990s were characterized by an increasing emphasis on topics which fall under the general headings of distribution (cooperation and social structure) and particularly reproduction (mate choice, mating systems, reproductive decisions, parental investment), rather than production (foraging). Anthropologists continued to dominate HBE, and the methodologies of the studies reflect this: many of the studies represented the field observations of a single field researcher from a single population, usually a single site. Having briefly outlined what HBE is and where it came from, we now turn to reviewing the HBE research that has appeared in the years since the publication of Winterhalder and Smith (2000) .

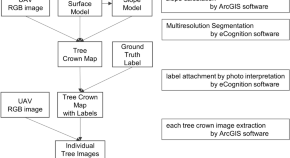

Our objective was to ascertain what empirical research has been done within the HBE paradigm since 2000, and characterize its key features, quantitatively where possible. We thus conducted a systematic search of 17 key journals for papers published between the beginning of 2000 and late 2011, which clearly belong in the HBE tradition (see Supplementary material for full methodology). This involved some contentious decisions about how to draw the boundaries of HBE and in the end, we drew it narrowly, including only papers containing quantitative data on naturally occurring behavior in human populations and employing a clearly adaptive perspective. This excludes a large number of studies that take an adaptive perspective but measure hypothetical preferences or decisions in experimental scenarios. It also excludes many studies that focus on nonbehavioral traits such as stature or physical maturation. The sample is not exhaustive even of our chosen subset of HBE, given that some HBE research is published in edited volumes, books, or journals other than those we searched. However, we feel that our strategy provides a good transect through current research, which is prototypically HBE, and the sampling method is at least repeatable and self-consistent over time.

We used the full text of the papers identified to code a number of key variables relevant to our review, including year of publication, journal, first author country of affiliation, and first author academic discipline. We also adopted Winterhalder and Smith’s (2000) ternary classification of topics into production (foraging and other productive activity), distribution (resource sharing, cooperation, social structure), and reproduction (mate choice decisions, sexual selection, life-history decisions, parental and alloparental investment). Finally, we coded the presence of some key features we wished to examine: the presence of any data from foraging populations, the presence of any data from industrialized populations, the use of secondary data, and the use of comparative data from more than one population.

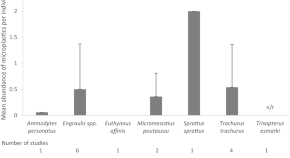

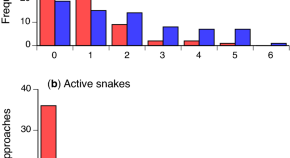

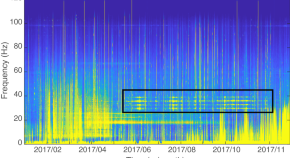

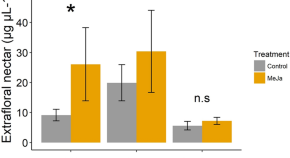

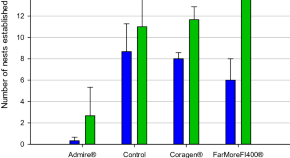

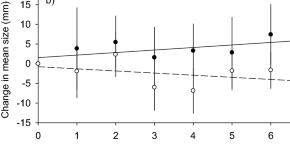

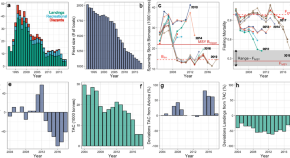

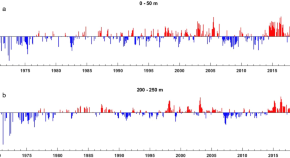

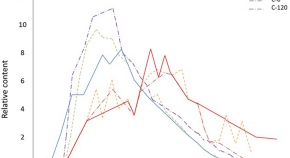

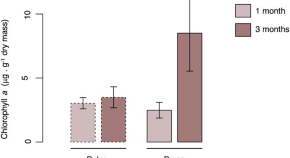

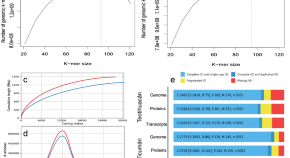

The search resulted in a database of 369 papers (see Supplementary material for reference list and formal statistical analysis; an endnote library of the references of the papers in the database is also available from the corresponding author). The distribution of papers across journals is shown in Table 1 , which also shows the median year of publication of a paper in that journal. The overall median year of publication for the full sample was 2007; thus, the table can be used to identify those journals that carried HBE papers disproportionately earlier in the study interval (e.g., American Anthropologist , median 2004), and those which carried them disproportionately more recently (e.g., American Journal of Human Biology , median 2009). The total number of papers found per year increased significantly over the 12 years sampled, from around 20 at the beginning to nearly 50 in 2011 ( Figure 1a ; regression analysis suggests an average increase of 2.4 papers per year). In the Supplementary material , we show that HBE papers also increased as a proportion of all papers published in our target journals. First authors were affiliated with institutions in 28 different countries, with 57.5% based in the United States and 20.1% in the United Kingdom. In terms of discipline, anthropology (including archaeology) was strongly represented (49.9% of papers), followed by psychology (19.5%) and biology (12.7%). The remaining papers came from demography (3.3%), medicine and public health (3.0%), sociology and social policy (2.4%), economics and political science (2.2%), or were for various reasons unclassifiable (7.0%). However, the growth in number of papers over time was due to increasing HBE activity outside anthropology ( Figure 1a ). In 2000–2003, 64.0% of papers were from anthropology departments, whereas by 2009–2011, this figure was 47.4%. Our search strategy may, if anything, have underestimated the growth in HBE research from outside anthropology, because our search strategy was based on the journals that had carried important BE or HBE research prior to 2000 and did not include any specialist journals from disciplines such as demography or public health.

Numbers and percentages of papers in the database by journal. Also shown is the median year of publication of an HBE paper in the sample in that journal

a Formerly Journal of Cultural and Evolutionary Psychology .

b Targeted search only; for all other journals, all abstracts read.

Number of published papers identified by year over the study period (a) by disciplinary affiliation of first author; (b) by type of study population (other = agriculturalist, pastoralist, horticulturalist, or multiple types); (c) by tripartite classification of topic.

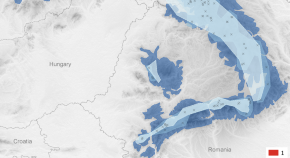

In terms of type of population studied, 80 papers (21.7%) contained some data from foragers, broadly defined to include any subsistence population for whom foraging forms a substantial part of the diet. One hundred and forty-five papers (39.3%) contained data from industrialized populations. The remainder of papers studied either contemporary or historical agricultural, horticultural, and pastoral populations. As Figure 1b shows, the amount of work on industrialized populations has tended to increase over time, with 22 such papers in 2000–2002 (29.3% of total) and 58 in 2009–2011 (43.0%). By contrast, the amount of work on forager populations is much more stable (20 papers [26.7%] in 2000–2002, 27 papers [20.0%] in 2009–2011). As for topic, we classified 64.8% of our papers as concerning reproduction, with 9.5% concerning production and 13.3% distribution. The remaining 12.5% either spanned several topics or fit none of the 3 categories. Table 2 gives some examples of popular research questions addressed in each of the 3 topic areas. The preponderance of reproduction has increased over time ( Figure 1c ); in 2000–2002, 53.3% of the papers fell into this category, whereas by 2009–2011, it was 68.9%. In fact, the growth of HBE papers during the study period has been completely driven by an increase in papers on reproductive topics (see Supplementary material ). We classified papers according to whether they involved analysis of secondary data sets gathered for other purposes. The number of papers involving such secondary analysis increased sharply through the study period, whereas those involving primary data did not (see Supplementary material ). Comparative analyses also increased significantly over time, but not faster than the overall growth in paper numbers.

Some examples of popular research questions in our database of recent HBE papers

To summarize, the data suggest that HBE has changed measurably in the period since 2000. Some of the changes in this period represent continuations of trends already incipient before, such as the expansion away from foraging and foragers toward reproduction and other types of population ( Winterhalder and Smith 2000 ). Our analysis suggests that it is primarily research into the BE of industrialized societies, which has expanded in the subsequent years, such that over 40% of HBE research published in the most recent 3-year period was conducted on such populations. More “traditional” HBE studies of foraging and small-scale food producing societies have continued, but only at a modestly increased rate compared with the 1990s. An unexpected feature of HBE post-2000 is the expansion of HBE in disciplines outside anthropology. Much of the growth has come from the adoption of HBE ideas by researchers based in departments of psychology, and, to a modest extent, other social sciences such as demography, public health, economics, and sociology. This is concomitant with the increasing focus on large-scale industrialized societies, as well as changes in methodology. Anthropologists often work alone or in small teams to gather special-purpose, opportunistic data sets from a particular field site, and many of the pioneering HBE studies were done in this way. In demography, public health, and sociology, by contrast, research tends to be based on very large, systematically collected, representative data sets, such as censuses, cohort, and panel studies, which are designed with multiple purposes in mind. Particular researchers can then interrogate them secondarily to address their particular questions. As HBE has welcomed more researchers from these other social sciences, it has also adopted these secondary methods more strongly (see section “Strengths” for further discussion). We also note the increase in the number of comparative studies. Comparative methods (albeit usually comparing related species rather than populations of the same species) have been a strong feature of BE since the outset (or before, Cullen 1957 ), and thus this is a natural development for HBE. HBE comparative studies use existing cross-cultural databases ( Quinlan 2007 ), integrate multiple ethnographic or historical sources ( Brown et al. 2009 ), or, increasingly, coordinate researchers to collect or derive standardized measures across multiple populations ( Walker et al. 2006 ; Borgerhoff Mulder et al. 2009 ). Comparative studies have become more powerful in their analytical strategies (see section “Strengths”).

The literature review in section “A systematic overview of current research” allowed us to characterize current HBE research and show some of the ways it has changed in the last decade. In this section, we discuss what we see as the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and open questions for HBE as a paradigm. This is inevitably more of a personal assessment than the preceding sections, and we appreciate that not everyone in the field will share our views.

The first obvious strength of HBE is vitality . As Darwinians, it comes naturally to us to assume that something that is increasing in frequency has some beneficial features. Thus, the fact that the number of recognizably HBE papers per year found by our search strategy has doubled in a decade, and that there are more and more adopters outside of anthropology, indicates that a range of people find an HBE approach useful. Where does this utility spring from? In part, it is that HBE models tend to make very clear, a priori predictions motivated by theory. The same cannot be said of all other approaches in the human sciences, and, arguably, the more we complicate behavioral ecological models by including details about how proximate mechanisms work, the more this clarity tends to disappear. We return in section “Open questions” to the issue of whether agnosticism about mechanism can be justified, but we note here that a great strength of (and defense for) simple HBE models is that they so often turn out to be empirically fruitful, despite their simplicity. Whether we are considering when to have a first baby ( Nettle 2011 ), what the effects of having an extra child will be in different ecologies ( Lawson and Mace 2011 ), whether to marry polygynously, polyandrously, or monogamously ( Fortunato and Archetti 2010 ; Starkweather and Hames 2012 ), or which relatives to invest time and resources in ( Fox et al. 2010 ), predictions using simple behavioral ecological principles turn out to be useful in making sense of empirically observed diversity in behavior. HBE has also demonstrated the generality of certain principles, such as the fact that male culturally defined social success is positively associated with reproductive success in many different types of society, albeit that the slope of the relationship differs according to features of the social system ( Irons 1979 ; Kaplan and Hill 1985 ; Borgerhoff Mulder 1987 ; Hopcroft 2006 ; Fieder and Huber 2007 ; Nettle and Pollet 2008 ).

A related strength of HBE is its broad scope . HBE models can apply to many kinds of behavioral decision (in principle, all kinds) and in all kinds of society. It is relatively rare in the human sciences for the same set of predictive principles to apply to variation both within and between societies and to societies ranging from small-scale subsistence populations to large-scale industrial states, but HBE thinking about, for example, reproductive decisions has exactly this scope ( Nettle 2011 ; Sear and Coall 2011 ). This would be a strength indeed, even without the crucial additional feature that the explanatory principles invoked are closely related to those that can be applied to species other than our own. Thus, HBE brings a relative conceptual coherence to the study of human behavior, a study that has traditionally been spread across a number of different disciplines each with different conceptual starting points.

Another strength of HBE as we have defined it here is its relatively high ecological validity . Much psychological research into human behavior relies on hypothetical self-reports and self-descriptions, or contrived experimental situations ( Baumeister et al. 2007 ), and much of behavioral economics consists of artificial games whose relevance to actual allocation decisions outwith the laboratory has been questioned ( Levitt and List 2007 ; Bardsley 2008 ; Gurven and Winking 2008 ). Although human behavioral ecologists use such techniques as their purposes require, at the heart of HBE is still a commitment to looking at what people really do, in the environments in which they really live, as a central component of the endeavor. Furthermore, HBE’s focus on behavioral diversity means that it has studied a much wider range of populations than other approaches in the human sciences (see Henrich et al. 2010 ), and this has led to a healthy skepticism of simple generalizations about human universal preferences or motivations ( Brown et al. 2009 ). Measuring relationships between behavior and fitness-relevant outcomes across a broad range of environments, HBE has now amassed considerable evidence in favor of its core assumptions that context matters when studying the adaptive consequences of human behavior and that behavioral diversity arises because the payoffs to alternative behavioral strategies are ecologically contingent.

HBE is also characterized by increasing methodological rigor. The early phases of HBE were defined by exciting theoretical developments, as evolutionary hypotheses for human behavioral variation were first formulated and presented in the literature. However, conducting empirical studies capable of rigorously testing hypotheses derived from HBE theory presents a number of methodological challenges, not least because the human species is relatively long lived and rarely amenable to experimental manipulation. These challenges are now being increasingly overcome, as HBE expands its tool kit to include new sources of data, statistical methods, and study designs. As noted in the section “A systematic overview of current research,” recent years have witnessed an increased use of secondary demographic and social survey data sets, which often provide larger, more representative samples and a broader range of variables than afforded by field research. Some sources of secondary data have also enabled lineages to be tracked beyond the life span of any individual researcher, providing valuable new data on the correlates of long-term fitness (e.g., Lahdenpera et al. 2004 ; Goodman and Koupil 2009 ).

Statistical methods have also become more advanced. Multilevel analyses are now routinely used in HBE research to deal with hierarchically structured data and accurately partition sources of behavioral variance at different levels (e.g., within and between villages; Lamba and Mace 2011 ). Phylogenetic comparative methods, which utilize information on historical relationships between populations, have become popular for testing coevolutionary hypotheses since they were first applied to human populations in the early 1990s ( Mace and Pagel 1994 ; Mace and Holden 2005 ), though debate remains about their suitability for modeling behavioral transmission in humans ( Borgerhoff Mulder et al. 2006 ). Issues of causal inference are also being addressed with more sophisticated analytical techniques. For example, structural equation modeling and longitudinal methods such as event history analysis have enabled researchers to achieve greater confidence when controlling for potential cofounding relationships (e.g., Sear et al. 2002 ; Lawson and Mace 2009 ; Nettle et al. 2011 ). HBE researchers are also following wider trends in the social and natural sciences by exploring alternatives to classic significance testing, such as information-theoretic and Bayesian approaches for considering competing hypotheses ( Towner and Luttbeg 2007 ). Some researchers have also been able to harness “natural experiments” in situations where comparable populations or individuals are selectively exposed to socioecological change. For example, Gibson and Gurmu (2011) examined the effect of changes in land tenure (from family inheritance to government redistribution) on a population in rural Ethiopia, demonstrating that competition between siblings for marital and reproductive success only occurs when land is inherited across generations. These advancements represent an exciting and necessary step forward, as empirical methods “catch up” with the powerful theoretical framework set out in the early days of HBE.

Finally, HBE has shown itself capable of topical innovation. A pertinent recent example is cooperative breeding (typically loosely defined in HBE as the system whereby women receive help from other individuals in raising their offspring). The idea that human females might breed cooperatively had been around for several decades ( Williams 1957 ), and began to be tested empirically in the late 1980s and 1990s (e.g., Hill and Hurtado 1991 ), but it was the 21st century that saw a real upsurge in interest in this topic, leading to a revitalization of the study of kinship in humans ( Shenk and Mattison 2011 ). HBE has now mined many of the rich demographic databases available for our species to test empirically the hypothesis that the presence of other kin members is associated with reproductive outcomes such as child survival rates and fertility rates. These analyses typically find support for the hypothesis that women adopt a flexible cooperative breeding strategy where they corral help variously from the fathers of their children, other men, and pre- and postreproductive women ( Hrdy 2009 ).

Though we see HBE as a strong paradigm, there are some important weaknesses of its current research to be noted. The first is HBE’s relative isolation from the rest of BE. The core journals of BE are Behavioral Ecology and Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology . Our search revealed only 8 HBE papers in these journals (2.2% of the sample). The vast majority of papers in our sample appeared in journals which never carry studies of species other than humans, and we know of rather few human behavioral ecologists who also work on other systems. West et al. (2011) have recently argued that evolutionary concepts are widely misapplied (or outdated understandings are applied, a phenomenon colloquially dubbed “the disco problem”) in human research, due to insufficient active integration between HBE and the rest of evolutionary biology.

HBE is clearly not completely decoupled from the rest of BE (see Machery and Cohen 2012 for quantitative evidence on this point). For example, within BE, there has been a decline in interest in foraging theory and a rise in interest in sexual selection ( Owens 2006 ), which are mirrored in the changes in HBE described in section “A systematic overview of current research.” Behavioral ecologists have also become less concerned with simply showing that animals make adaptive decisions, and more concerned with the nature of the neurobiological and genetic mechanisms underlying this ( Owens 2006 ). Parallel developments have occurred in the human literature, with the rise of adaptive studies of psychological mechanisms (see e.g., Buss 1995 ). Our search strategy did not include these studies, because their methodologies are different from those of “classical” HBE, but there is no doubt that they have increased in number. Finally, we note that there has been a recent increase in interest in measuring natural selection directly in contemporary human populations ( Nettle and Pollet 2008 ; Byars et al. 2010 ; Stearns et al. 2010 ; Milot et al. 2011 ; Courtiol et al. 2012 ). This anchors HBE much more strongly to evolutionary biology in general. Despite these developments, we see the isolation of HBE from the rest of biology as a potential risk. We hope to see more behavioral ecologists start to work on humans, and more projects across taxonomic boundaries, in the future.

Finally, we note the rather restricted topic base. HBE has had a great deal to say recently about mating strategies, reproductive decisions, fertility, and reproductive success, but much less about diet, resource extraction, resource storage, navigation, spatial patterns of habitat use, hygiene, social coordination, or the many other elements involved in staying alive. In part, this is because, as HBE expands to focus more on large-scale populations, it discovers that there are already disciplines (economics, sociology, human geography, public health) that deal extensively with these topics. It is in the general area of reproduction that it is easiest to come up with predictions that are obviously Darwinian and differentiate HBE from existing social science approaches. Nonetheless, the explanatory strategy of HBE is of potential use for any topic where behavioral effort has to be allocated in one way rather than another, and thus we would hope to see a broadening of the range of questions addressed as HBE continues to grow.

Opportunities

As HBE continues to expand, we see a major opportunity for HBE to build bridges to the social sciences. At the moment, most HBE papers are published in journals that only carry papers that take an adaptive evolutionary perspective, not general social science journals. Thus, HBE is possibly as separated from other approaches to human behavior as it is from parallel approaches to the behavior of other species. This may be because early proponents of HBE saw it as radically different from existing social science approaches to the same problems, by virtue of its generalizing hypothetico-deductive framework and commitment to quantitative hypothesis testing ( Winterhalder and Smith 2000 ). However, the social science those authors came into closest contact with was sociocultural anthropology, which is perhaps not a very typical social science (see Irons 2000 for an account of the hostile reception of HBE within sociocultural anthropology). As HBE’s expansion brings it into closer proximity with disciplines like economics, sociology, demography, public health, development studies, and political science, there may be more common ground than was previously thought. Social scientists are united in the notion that human behavior is very variable and that context is extremely important in giving rise to this variation. These are commitments that HBE obviously shares. Indeed, although it is still common in the human sciences for authors to rhetorically oppose “evolutionary” to “nonevolutionary” (or “social” and “biological”) explanations of the same problem as if these were mutually exclusive endeavors ( Nettle 2009a ), HBE defies such dichotomies adeptly.

Much of social science is highly quantitative and, generally lacking the ability to perform true experiments, relies on multivariate statistical approaches applied to observational data sets to test between competing explanations for behavior patterns. HBE is just the same, and indeed, since the millennium, has become much more closely allied to other social sciences, adopting the large-scale data resources they provide, as well as methodological tools like multilevel modeling, which they have developed to deal with these. HBE employs a priori models based on the individual as maximizer, a position not shared explicitly by all social sciences. However, this approach is widespread in economics and political science. Indeed, it was economics that gave it to BE. The big difference between HBE and much of social science is the explicit invocation of inclusive fitness (or its proxies) as the end to which behavior is deployed. This does not necessarily make it a competing endeavor, especially because what is measured in HBE is not usually fitness itself, but more immediate proxies. Rather, HBE models can often be seen as adding an explicitly ultimate layer of explanation, giving rise to new predictions and unifying diverse empirical observations, without being incompatible with existing, more proximate theories.

Indeed, our perception is that a number of social science theories make assumptions about the ends of behavior, which are quite similar to those of HBE, just not explicitly expressed in Darwinian terms; basically, people’s sets of choices are constrained by the environment in which they have to live, and they make the best choices they can given these constraints, often with knock-on effects that behavioral ecologists would describe as trade-offs. Examples include the work of Geronimus on how African American women adjust their patterns of childbearing to the prevailing rates of mortality and morbidity in their neighborhoods ( Geronimus et al. 1999 ), the work of Drewnowski and colleagues on how people adjust the type of foodstuffs they consume to the budgets they have to spend ( Drewnowski and Specter 2004 ; Drewnowski et al. 2007 ), or Downey’s work on the effects of increasing family size on socioeconomic outcomes of the children ( Downey 2001 ). If the introductory sections of any of these papers were written from a more explicitly Darwinian perspective, they would look perfectly at home in a BE journal. The breaking down of the social science–natural science divide has long been held as desirable, but is not easy to achieve in practice. HBE’s boundary with the social sciences may be one frontier where some progress can occur. Social scientists have long lamented the fragmentation of their field into multiple disciplinary areas with little common ground (e.g., Davis 1994 ). Given HBE’s broad scope and general principles, it has the potential to serve as something of a lingua franca across social scientists working on different kinds of problems.

A related opportunity for HBE is the potential for applied impact . HBE models have the potential to provide new and practical insights into contemporary world issues, from natural resource management ( Tucker 2007 ) to the consequences of inequality within developed populations ( Nettle 2010 ). The causes and consequences of recent human behavioral and environmental changes (including urbanization, economic development, and population growth) are recurring themes in recent studies in HBE. The utility of an ecological approach is clearly demonstrated in studies exploring the effectiveness of public policies or intervention schemes seeking to change human behavior or environments. HBE models clarify that human behavior tends to be deployed in the service of reproductive success, not financial prudence, health, personal or societal wellbeing ( Hill 1993 ), an important insight that differs from some economic or psychological theories. By providing insights into ultimate motivations and proximate pathways to human behavioral change, HBE studies can sometimes offer direct recommendations for the design and implementation of future initiatives ( Gibson and Mace 2006 ; Shenk 2007 ; Gibson and Gurmu 2011 ). Addressing contemporary world issues does, however, present methodological and theoretical challenges for HBE, requiring more explicit consideration of how research insights may be translated into interventions and communicated to policymakers and users ( Tucker and Taylor 2007 ).

Open questions

An open question for HBE is how the study of mechanism can be integrated into functional enquiry. This is an issue for BE generally, not just the human case. As mentioned in the section “What is HBE?”, BE has tended to proceed by the behavioral gambit—the assumption that the nature of the proximate mechanisms underlying behavioral decisions is not important in theorizing about the functions of behavior. It is important to understand the status of the behavioral gambit because it has sometimes been unfairly criticized (see Parker and Maynard Smith 1990 ). In the natural world, individuals do not always behave optimally with respect to any particular decision because there are phylogenetic or mechanistic constraints on their ability to reach adaptive solutions. However, in general terms, the only way to discover the existence of such departures from optimality is to have a theoretical model that shows what the optimal behavior would be and to test empirically whether individual behavior shows the predicted pattern. Where it does not, this may point to unappreciated constraints or trade-offs and thus shed light on the biology of the organism under study. Thus, the use of the term gambit is entirely apt; the behavioral gambit is a way of opening the enquiry designed to gain some advantage in the quest to understand. It is not the end game.

Where there is no sizable departure from predicted optimality, the ultimate adaptive explanation does not depend critically on understanding the mechanisms. This does not mean the question of mechanism is unimportant, of course; mechanistic explanations must still be sought and integrated with functional ones. This is beginning to occur in some cases. In the field of human reproductive ecology, the physiological mechanisms involved in adaptive strategies are beginning to be understood ( Kuzawa et al. 2009 ; Flinn et al. 2011 ), and there is also increasing interchange between HBE researchers and experimentalists studying psychological mechanisms ( Sear et al. 2007 ), which is clearly a development to be welcomed.

Where there is a patterned departure from optimality, understanding the mechanism becomes more critical. Aspects of mechanism can then be modeled as additional constraints, which may explain the strategies individuals pursue. For example, Kacelnik and Bateson (1996) showed that the pattern of risk aversion for variability in food amount and risk proneness for variability in food delay is not predicted by optimal foraging theory, except when Weber’s law (the principle that perceptions of stimulus magnitude are logarithmically, not linearly, related to actual stimulus magnitude) is incorporated into models as a mechanistic constraint. At a deeper level, though, this just raises further questions. Why should Weber’s law have evolved, and once it has evolved, can selection relax it for any particular task? These are what McNamara and Houston call “evo-mecho” questions ( McNamara and Houston 2009 ). Departures from optimality in one particular context raise such questions pervasively. Issues such as the robustness, neural instantiability, efficiency, and developmental cost of different kinds of mechanisms become salient here, and many apparently irrational quirks of behavior become interpretable as side effects of evolved mechanisms whose overall benefits have exceeded their costs over evolutionary time ( Fawcett et al. 2012 ). However, we would still argue that the best first approximation in understanding a question is to employ the behavioral gambit to generate and test simple optimality predictions, even though an understanding of mechanism will be essential for explaining why these may fail.

Although the issue of how incorporation of mechanism changes the predictions of BE models is a general one, in the human case, it has been discussed in particular with reference to transmitted culture because this is a class of mechanism on which humans are reliant to a unique extent ( Richerson and Boyd 2005 ). Transmitted culture refers to the behavioral traditions that arise from repeated social learning. Social learning can be an evolutionarily adaptive strategy, and the equilibrium solutions reached by it will often be the fitness-maximizing ones under reasonable assumptions ( Henrich and McElreath 2003 ). After all, if reliance on culture on average led to maladaptive outcomes, there would be strong selection on humans to rely on it less. Indeed, there is evidence that humans tend to forage efficiently for socially acquired information, using it when it is adaptive to do so ( Morgan et al. 2012 ). Thus, we would argue that culture can be treated, to a first approximation, just like any other proximate mechanism: that is, it can be set aside in the initial formulation of functional explanations ( Scott-Phillips et al. 2011 , though see Laland et al. 2011 for a different view). As an example, we could take Henrich and Henrich’s (2010) data on food taboos for pregnant and lactating women in Fiji. These authors show that the taboos reduce women’s chances of fish poisoning by 30% during pregnancy and 60% during breastfeeding and thus are plausibly adaptive. The fact that in this case it is culture by which women acquire them, rather than genes or individual learning, does not affect this conclusion or the data needed to test it. However, the quirks of how human social learning works may well explain some nonadaptive taboos that are found alongside the adaptive ones, which are in effect carried along by the generally adaptive reliance on social learning. Thus, although the behavioral gambit can be used to explain the major adaptive features of these taboos, an understanding of the cultural mechanisms is required to explain the details of how the observed behavior departs in subtle ways from the optimal pattern. Culture may often lead to maladaptive side effects in this way ( Richerson and Boyd 2005 ). Although its general effect is to allow humans to rapidly reach adaptive equilibria, nonadaptive traits can be carried along by it, and, compared with other proximate mechanisms, it produces very different dynamics of adaptive change.

A final open question is the extent of human maladaptation. Humans have increased their absolute numbers by orders of magnitude and colonized all major habitats of the planet, so they are clearly adept at finding adaptive solutions to the problem of living. However, there are also some clear cases of quite systematic departures from adaptive behavior. Perhaps most pertinently, the low fertility rate typical of industrial populations still defies a convincing adaptive explanation, despite being a longstanding topic for HBE research (see Borgerhoff Mulder 1998 ; Kaplan et al. 2002 ; Shenk 2009 ). There are patterns in the fertility of modernizing populations, which can be readily understood from an HBE perspective: parents in industrialized populations who have large families suffer a cost to the quality of their offspring, particularly with regard to educational achievement and adult socioeconomic success, so there is a quality–quantity trade-off ( Lawson and Mace 2011 ). Moreover, the reduction in fertility rate is closely associated with improvement in the survival of offspring to breed themselves, so that, as the transition to small families proceeds, the probability of having at least one grandchild may remain roughly constant ( Liu and Lummaa 2011 ). However, despite all this, it remains the case that people in affluent societies could still have many more grandchildren and great-grandchildren by having more children, and yet they do not ( Goodman et al. 2012 ). Any explanation of the demographic transition must, therefore, invoke some kind of maladaptation or mismatch between the conditions under which decision-making mechanisms evolved and those under which they are now operating.

Our review has shown that HBE is a growing and rapidly developing research area. The weaknesses of HBE mostly amount to a need for more research activity, and the unresolved questions, though important, do not in our view undermine HBE’s core strengths of theoretical coherence and empirical utility. HBE is being applied to more questions in more human populations with better methods than ever before. Our hope is that HBE will inspire more behavioral biologists to work on humans, for whom a wealth of data is available, and more social scientists to adopt an adaptive, ecological perspective on their behavioral questions, thus adding a layer of deeper explanations, as well as generating new insights.

Supplementary material can be found at Supplementary Data

Anderson KG Kaplan H Lancaster JB . 2007 . Confidence of paternity, divorce, and investment in children by Albuquerque men . Evol Hum Behav . 28 : 1 – 10 .

Google Scholar

Bardsley N . 2008 . Dictator game giving: altruism or artefact? Exp Econ . 11 : 122 – 133 .

Baumeister RF Vohs KD Funder DC . 2007 . Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: whatever happened to actual behavior? Perspect Psychol Sci . 2 : 396 – 408 .

Bliege Bird R Codding BF Bird DW . 2009 . What explains differences in men’s and women’s production? Hum Nat . 20 : 105 – 129 .

Bock J . 2002 . Learning, life history, and productivity . Hum Nat . 13 : 161 – 197 .

Borgerhoff Mulder M . 1987 . On cultural and reproductive success: Kipsigis evidence . Am Anthropol . 89 : 617 – 634 .

Borgerhoff Mulder M . 1988 . Behavioral ecology in traditional societies . Trends Ecol Evol . 3 : 260 – 264 .

Borgerhoff Mulder M . 1990 . Kipsigis women’s preferences for wealthy men: evidence for female choice in mammals . Behav Ecol Sociobiol . 27 : 255 – 264 .

Borgerhoff Mulder M . 1998 . The demographic transition: are we any closer to an evolutionary explanation? Trends Ecol Evol . 13 : 266 – 270 .

Borgerhoff Mulder M . 2007 . Hamilton’s rule and kin competition: the Kipsigis case . Evol Hum Behav . 28 : 299 – 312 .

Borgerhoff Mulder M Bowles S Hertz T Bell A Beise J Clark G Fazzio I Gurven M Hill K Hooper PL et al. 2009 . The intergenerational transmission of wealth and the dynamics of inequality in pre-modern societies . Science . 326 : 682 – 688 .

Borgerhoff Mulder M Nunn CL Towner MC . 2006 . Cultural macroevolution and the transmission of traits . Evol Anthropol . 15 : 52 – 64 .

Brown GR Laland KN Borgerhoff Mulder M . 2009 . Bateman’s principles and human sex roles . Trends Ecol Evol . 24 : 297 – 304 .

Bulled NL Sosis R . 2010 . Examining the relationship between life expectancy, reproduction, and educational attainment . Hum Nat . 21 : 269 – 289 .

Burton-Chellew MN Dunbar RIM . 2011 . Are affines treated as biological kin? Curr Anthropol . 52 : 741 – 746 .

Buss DM . 1995 . Evolutionary psychology: a new paradigm for psychological science . Psychol Inquiry . 6 : 1 – 49 .

Byars SG Ewbank D Govindaraju DR Stearns SC . 2010 . Natural selection in a contemporary human population . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 107 : 1787 – 1792 .

Chisholm JS Quinlivan JA Petersen RW Coall DA . 2005 . Early stress predicts age at menarche and first birth, adult attachment, and expected lifespan . Hum Nat . 16 : 233 – 265 .

Clarke AL Low BS . 2001 . Testing evolutionary hypotheses with demographic data . Popul Dev Rev . 27 : 633 – 660 .

Codding BF Bird RB Bird DW . 2011 . Provisioning offspring and others: risk-energy trade-offs and gender differences in hunter-gatherer foraging strategies . Proc R Soc B Biol Sci . 278 : 2502 – 2509 .

Courtiol A Pettay JE Jokela M Rotkirch A Lummaa V . 2012 . Natural and sexual selection in a monogamous historical human population . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 109 : 8044 – 8049 .

Cronk L . 1991 . Human behavioral ecology . Annu Rev Anthropol . 20 : 25 – 53 .

Cullen E . 1957 . Adaptations in the kittiwake to cliff nesting . Ibis . 99 : 275 – 302 .

Davies NB Krebs JR West SA . 2012 . An introduction to behavioural ecology . Chichester : Wiley-Blackwell p. 22 .

Google Preview

Davis J Werre D . 2008 . A longitudinal study of the effects of uncertainty on reproductive behaviors . Hum Nat . 19 : 426 – 452 .

Davis JA . 1994 . What’s wrong with sociology? Sociol Forum . 9 : 179 – 197 .

Downey DB . 2001 . Number of siblings and intellectual development—the resource dilution explanation . Am Psychol . 56 : 497 – 504 .

Drewnowski A Monsivais P Maillot M Darmon N . 2007 . Low-energy-density diets are associated with higher diet quality and higher diet costs in French adults . J Am Diet Assoc . 107 : 1028 – 1032 .

Drewnowski A Specter SE . 2004 . Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs . Am J Clin Nutr . 79 : 6 – 16 .

Dyson-Hudson R Smith EA . 1978 . Human territoriality: an ecological reassessment . Am Anthropol . 80 : 21 – 41 .

Fawcett TW Hamblin S Giraldeau LA . Forthcoming 2012 . Exposing the behavioral gambit: the evolution of learning and decision rules . Behav Ecol . Advance Access published July 25 2012, doi:10.1093/beheco/ars085.

Fieder M Huber S . 2007 . The effects of sex and childlessness on the association between status and reproductive output in modern society . Evol Hum Behav . 28 : 392 – 398 .

Flinn MV Nepomnaschy PA Muehlenbein MP Ponzi D . 2011 . Evolutionary functions of early social modulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis development in humans . Neurosci Biobehav Rev . 35 : 1611 – 1629 .

Fortunato L Archetti M . 2010 . Evolution of monogamous marriage by maximization of inclusive fitness . J Evol Biol . 23 : 149 – 156 .

Fox M Sear R Beise J Ragsdale G Voland E Knapp LA . 2010 . Grandma plays favourites: X-chromosome relatedness and sex-specific childhood mortality . Proc R Soc B Biol Sci . 277 : 567 – 573 .

Geronimus AT Bound J Waidmann TA . 1999 . Health inequality and population variation in fertility-timing . Soc Sci Med . 49 : 1623 – 1636 .

Gibson MA Gurmu E . 2011 . Land inheritance establishes sibling competition for marriage and reproduction in rural Ethiopia . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 108 : 2200 – 2204 .

Gibson MA Mace R . 2006 . An energy-saving development initiative increases birth rate and childhood malnutrition in rural Ethiopia . PLoS Med . 3 : e87 .

Gibson MA Mace R . 2007 . Polygyny, reproductive success and child health in rural Ethiopia: why marry a married man? J Biosoc Sci . 39 : 287 – 300 .

Goodman A Koupil I . 2009 . Social and biological determinants of reproductive success in Swedish males and females born 1915–1929 . Evol Hum Behav . 30 : 329 – 341 .

Goodman A Koupil I Lawson DW . 2012 . Low fertility increases descendant socioeconomic position but reduces long-term fitness in a modern post-industrial society . Proc R Soc B Biol Sci . 279 : 4342 – 4351 .

Grafen A . 1984 . Natural selection, kin selection and group selection . In: Krebs JR Davies NB , editors. Behavioural ecology: an evolutionary approach . 2nd ed Oxford : Blackwell p. 62 – 84 .

Grafen A . 2006 . Optimization of inclusive fitness . J Theor Biol . 238 : 541 – 563 .

Gurven M . 2004 . Reciprocal altruism and food sharing decisions among Hiwi and Ache hunter-gatherers . Behav Ecol Sociobiol . 56 : 366 – 380 .

Gurven M Borgerhoff Mulder M Hooper Paul L Kaplan H Quinlan R Sear R Schniter E von Rueden C Bowles S Hertz T et al. 2010 . Domestication alone does not lead to inequality . Curr Anthropol . 51 : 49 – 64 .

Gurven M Kaplan H . 2006 . Determinants of time allocation across the lifespan . Hum Nat . 17 : 1 – 49 .

Gurven M Winking J . 2008 . Collective action in action: prosocial behavior in and out of the laboratory . Am Anthropol . 110 : 179 – 190 .

Hadley C . 2004 . The costs and benefits of kin . Hum Nat . 15 : 377 – 395 .

Hames R McCabe C . 2007 . Meal sharing among the Ye’kwana . Hum Nat . 18 : 1 – 21 .

Hamilton MJ Milne BT Walker RS Brown JH . 2007 . Nonlinear scaling of space use in human hunter-gatherers . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 104 : 4765 – 4769 .

Hawkes K O’Connell JF Blurton Jones NG . 2001 . Hadza meat sharing . Evol Hum Behav . 22 : 113 – 142 .

Henrich J Heine SJ Norenzayan A . 2010 . The weirdest people in the world? Behav Brain Sci . 33 : 61 – 83 .

Henrich J Henrich N . 2010 . The evolution of cultural adaptations: Fijian food taboos protect against dangerous marine toxins . Proc R Soc B Biol Sci . 277 : 3715 – 3724 .

Henrich J McElreath R . 2003 . The evolution of cultural evolution . Evol Anthropol . 12 : 123 – 135 .

Hill K . 1993 . Life history theory and evolutionary anthropology . Evol Anthropol . 2 : 78 – 88 .

Hill K Hurtado AM . 1991 . The evolution of premature reproductive senescence and menopause in human females: an evaluation of the “grandmother” hypothesis . Hum Nat . 2 : 313 – 350 .

Hilton CE Greaves RD . 2008 . Seasonality and sex differences in travel distance and resource transport in Venezuelan foragers . Curr Anthropol . 49 : 144 – 153 .

Hopcroft RL . 2006 . Sex, status and reproductive success in the contemporary US . Evol Hum Behav . 27 : 104 – 120 .

Hrdy SB . 2009 . Mothers and others: the evolutionary origins of mutual understanding . Cambridge (MA) : The Belknap Press

Irons W . 1979 . Cultural and biological success . In: Chagnon NA Irons W , editors. Evolutionary biology and human social behavior: an anthropological perspective . North Scituate : Duxbury p. 257 – 272 .

Irons W . 2000 . Two decades of a new paradigm . In: Cronk L Chagnon N Irons W , editors. Adaptation and human behavior: an anthropological perspective . New York : Aldine p. 2 – 26 .

Kacelnik A Bateson M . 1996 . Risky theories—the effects of variance on foraging decisions . Am Zool . 36 : 402 – 434 .

Kaplan H . 1996 . A theory of fertility and parental investment in traditional and modern societies . Yearbk Phys Anthropol . 39 : 91 – 135 .

Kaplan H Hill K . 1985 . Hunting ability and reproductive success amongst male Ache foragers . Curr Anthropol . 26 : 131 – 133 .

Kaplan H Lancaster JB Tucker WT Anderson KG . 2002 . Evolutionary approach to below replacement fertility . Am J Hum Biol . 14 : 233 – 256 .

Kramer KL Greaves RD . 2011 . Juvenile subsistence effort, activity levels, and growth patterns . Hum Nat . 22 : 303 – 326 .

Krebs JR Davies NB . 1981 . An introduction to behavioural ecology . Oxford : Blackwell

Kuzawa CW Gettler LT Muller MN McDade TW Feranil AB . 2009 . Fatherhood, pairbonding and testosterone in the Philippines . Horm Behav . 56 : 429 – 435 .

Lahdenpera M Lummaa V Helle S Tremblay M Russell AF . 2004 . Fitness benefits of prolonged post-reproductive lifespan in women . Nature . 428 : 178 – 181 .

Laland KN Brown GR . 2006 . Niche construction, human behavior, and the adaptive-lag hypothesis . Evol Anthropol . 15 : 95 – 104 .

Laland KN Sterelny K Odling-Smee J Hoppitt W Uller T . 2011 . Cause and effect in biology revisited: is Mayr’s proximate-ultimate dichotomy still useful? Science . 334 : 1512 – 1516 .

Lamba S Mace R . 2011 . Demography and ecology drive variation cooperation across human populations . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 108 : 14426 – 14430 .

Lawson DW Mace R . 2009 . Trade-offs in modern parenting: a longitudinal study of sibling competition for parental care . Evol Hum Behav . 30 : 170 – 183 .

Lawson DW Mace R . 2011 . Parental investment and the optimization of human family size . Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci . 366 : 333 – 343 .

Levitt SD List JA . 2007 . On the generalizability of lab behaviour to the field . Can J Econ . 40 : 347 – 370 .

Liu JH Lummaa V . 2011 . Age at first reproduction and probability of reproductive failure in women . Evol Hum Behav . 32 : 433 – 443 .

Mace R Holden CJ . 2005 . A phylogenetic approach to cultural evolution . Trends Ecol Evol . 20 : 116 – 121 .

Mace R Pagel M . 1994 . The comparative method in anthropology . Curr Anthropol . 35 : 549 – 564 .

Machery E Cohen K . 2012 . An evidence-based study of the evolutionary behavioral sciences . Br J Philos Sci . 63 : 177 – 226 .

Mayr E . 1961 . Cause and effect in biology . Science . 134 : 1501 – 1506 .

McNamara JM Houston AI . 2009 . Integrating function and mechanism . Trends Ecol Evol . 24 : 670 – 675 .

Migliano AB Vinicius L Lahr MM . 2007 . Life history trade-offs explain the evolution of human pygmies . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 104 : 20216 – 20219 .

Milot E Mayer FM Nussey DH Boisvert M Pelletier F Reale D . 2011 . Evidence for evolution in response to natural selection in a contemporary human population . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 108 : 17040 – 17045 .

Morgan TJH Rendell LE Ehn M Hoppitt W Laland KN . 2012 . The evolutionary basis of human social learning . Proc R Soc B Biol Sci . 279 : 653 – 662 .

Næss MW Bårdsen B-J Fauchald P Tveraa T . 2010 . Cooperative pastoral production—the importance of kinship . Evol Hum Behav . 31 : 246 – 258 .

Nettle D . 2009 . Beyond nature versus culture: cultural variation as an evolved characteristic . J Roy Anthropol Inst . 15 : 223 – 240 .

Nettle D . 2009 . Ecological influences on human behavioural diversity: a review of recent findings . Trends Ecol Evol . 24 : 618 – 624 .

Nettle D . 2010 . Why are there social gradients in preventative health behavior? A perspective from behavioral ecology . PLoS ONE . 5 :– e13371 .

Nettle D . 2011 . Flexibility in reproductive timing in human females: integrating ultimate and proximate explanations . Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci . 36 : 357 – 365 .

Nettle D Coall DA Dickins TE . 2011 . Early-life conditions and age at first pregnancy in British women . Proc R Soc B Biol Sci . 278 : 1721 – 1727 .

Nettle D Pollet TV . 2008 . Natural selection on male wealth in humans . Am Nat . 172 : 658 – 666 .

Owens IPF . 2006 . Where is behavioural ecology going? Trends Ecol Evol . 21 : 356 – 361 .

Pacheco-Cobos L Rosetti M Cuatianquiz C Hudson R . 2010 . Sex differences in mushroom gathering: men expend more energy to obtain equivalent benefits . Evol Hum Behav . 31 : 289 – 297 .

Panter-Brick C . 2002 . Sexual division of labor: energetic and evolutionary scenarios . Am Anthropol . 14 : 627 – 640 .

Parker GA Maynard Smith J . 1990 . Optimality theory in evolutionary biology . Nature . 348 : 27 – 33 .

Pashos A McBurney DH . 2008 . Kin relationships and the caregiving biases of grandparents, aunts, and uncles . Hum Nat . 19 : 311 – 330 .

Patton JQ . 2005 . Meat sharing for coalitional support . Evol Hum Behav . 26 : 137 – 157 .

Pigliucci M . 2005 . Evolution of phenotypic plasticity: where are we going now? Trends Ecol Evol . 20 : 481 – 486 .

Pollet TV Nettle D . 2009 . Market forces affect patterns of polygyny in Uganda . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 106 : 2114 – 2117 .

Quinlan RJ . 2007 . Human parental effort and environmental risk . Proc R Soc B Biol Sci . 274 : 121 – 125 .

Richerson PJ Boyd R . 2005 . Not by genes alone: how culture transformed human evolution . Chicago (IL) : Chicago University Press

Roth EA . 2000 . On pastoralist egalitarianism: consequences of primogeniture among the Rendille . Curr Anthropol . 41 : 269 – 271 .

Scheiner SM . 1993 . Genetics and evolution of phenotypic plasticity . Annu Rev Ecol Syst . 24 : 35 – 68 .

Scott-Phillips TC Dickins TE West SA . 2011 . Evolutionary theory and the ultimate-proximate distinction in the human behavioral sciences . Perspect Psychol Sci . 6 : 38 – 47 .

Sear R Coall D . 2011 . How much does family matter? Cooperative breeding and the demographic transition . Popul Dev Rev . 37, Issue Supplement s1 : 81 – 112 .

Sear R Lawson DW Dickins TE . 2007 . Synthesis in the human evolutionary behavioural sciences . J Evol Psychol . 5 : 3 – 28 .

Sear R Steele F McGregor AA Mace R . 2002 . The effects of kin on child mortality in rural Gambia . Demography . 39 : 43 – 63 .

Shenk MK . 2007 . Dowry and public policy in contemporary India—the behavioral ecology of a “social evil” . Hum Nat . 18 : 242 – 263 .

Shenk MK . 2009 . Testing three evolutionary models of the demographic transition: patterns of fertility and age at marriage in urban South India . Am J Hum Biol . 21 : 501 – 511 .

Shenk MK Borgerhoff Mulder M Beise J Clark G Irons W Leonetti D Low Bobbi S Bowles S Hertz T Bell A et al. 2010 . Intergenerational wealth transmission among agriculturalists . Curr Anthropol . 51 : 65 – 83 .

Shenk MK Mattison SM . 2011 . The rebirth of kinship: evolutionary and quantitative approaches in the revitalization of a dying field . Hum Nat . 22 : 1 – 15 .

Smith EA . 1983 . Anthropological applications of optimal foraging theory: a critical review . Curr Anthropol . 24 : 625 – 651 .

Starkweather K Hames R . 2012 . A survey of non-classical polyandry . Hum Nat . 23 : 149 – 172 .

Stearns SC Byars SG Govindaraju DR Ewbank D . 2010 . Measuring selection in contemporary human populations . Nat Rev Genet . 11 : 611 – 622 .

Stewart-Williams S . 2007 . Altruism among kin vs. nonkin: effects of cost of help and reciprocal exchange . Evol Hum Behav . 28 : 193 – 198 .

Strassmann BI Gillespie B . 2002 . Life-history theory, fertility and reproductive success in humans . Proc R Soc B Biol Sci . 269 : 553 – 562 .

Tanskanen AO Rotkirch A Danielsbacka M . 2011 . Do grandparents favor granddaughters? Biased grandparental investment in UK . Evol Hum Behav . 32 : 407 – 415 .

Tifferet S Manor O Constantini S Friedman O Elizur Y . 2007 . Parental investment in children with chronic disease: the effect of child’s and mother’s age . Evol Psychol . 5 : 844 – 859 .

Tinbergen N . 1963 . On aims and methods in ethology . Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie . 20 : 410 – 433 .

Towner MC Luttbeg B . 2007 . Alternative statistical approaches to the use of data as evidence for hypotheses in human behavioral ecology . Evol Anthropol . 16 : 107 – 118 .

Tracer DP . 2009 . Breastfeeding structure as a test of parental investment theory in Papua New Guinea . Am J Hum Biol . 21 : 635 – 642 .

Tucker B . 2007 . Applying behavioral ecology and behavioral economics to conservation and development planning: an example from the Mikea forest, Madagascar . Hum Nat . 18 : 190 – 208 .

Tucker B Taylor LR . 2007 . The human behavioral ecology of contemporary world issues—applications to public policy and international development . Hum Nat . 18 : 181 – 189 .

Voland E . 2000 . Contributions of family reconstitution studies to evolutionary reproductive ecology . Evol Anthropol . 9 : 134 – 146 .

Voland E Beise J . 2002 . Opposite effects of maternal and paternal grandmothers on infant survival in historical Krummhörn . Behav Ecol Sociobiol . 52 : 435 – 443 .

Walker R Gurven M Hill K Migliano H Chagnon N De Souza R Djurovic G Hames R Hurtado AM Kaplan H et al. 2006 . Growth rates and life histories in twenty-two small-scale societies . Am J Hum Biol . 18 : 295 – 311 .

Wells JCK Stock JT . 2007 . The biology of the colonizing ape . In: Stinson S , editor. Yearbook of physical anthropology . Vol. 50 : New York : Wiley-Liss, Inc p. 191 – 222 .

West SA El Mouden C Gardner A . 2011 . Sixteen common misconceptions about the evolution of cooperation in humans . Evol Hum Behav . 32 : 231 – 262 .

Williams GC . 1957 . Pleiotropy, natural selection and the evolution of senescence . Evolution . 11 : 398 – 411 .

Wilmsen EN . 1973 . Interaction, spacing behavior, and the organization of hunting bands . J Anthropol Res . 29 : 1 – 31 .

Wilson M Daly M . 1997 . Life expectancy, economic inequality, homicide, and reproductive timing in Chicago neighbourhoods . Br Med J . 314 : 1271 – 1274 .

Winterhalder B Smith EA . 2000 . Analyzing adaptive strategies: human behavioral ecology at twenty-five . Evol Anthropol . 9 : 51 – 72 .

Ziker J Schnegg M . 2005 . Food sharing at meals . Hum Nat . 16 : 178 – 210 .

Author notes

Supplementary data, email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-7279

- Copyright © 2024 International Society of Behavioral Ecology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Coming soon

- New releases

- Press Archive 1965–1991

- Authors & editors

- News & events

- For authors

- For libraries

Subscribe to the ANU Press Newsletter

Human Ecology Review

- Aims & scope

- Journal information

- Editorial Board

- Submission information

Human Ecology Review (HER) is a semi-annual journal that publishes peer-reviewed interdisciplinary research on all aspects of human–environment interactions (Research in Human Ecology) and reviews books of relevance to the journal’s subject matter and the interest of its readers. HER will not publish manuscripts that are purely biophysical nor ones that are purely sociocultural and it will not publish manuscripts that are monodisciplinary or specialisations to a specific discipline. Authors are strongly encouraged to make clear their manuscript’s connection to an understanding of human ecology and human ecological scholarship more broadly.

Ownership and management

Human Ecology Review is the official journal of the Society for Human Ecology.

Publishing schedule

Human Ecology Review is published by ANU Press twice yearly, in the first and second half of the year.

Human Ecology Review is an open-access journal, available from ANU Press. Individual print-on-demand copies are also available from ANU Press at the same address. Hard copies are available from Society for Human Ecology to subscribing members who selected to pay a premium for them when they registered. These copies are automatically mailed to these members.

Back copies of Human Ecology Review are available from ANU Press to Volume 21(2). JSTOR hosts all back issues.

Copyright and licensing

All issues published from Volume 24(2) onwards are published under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Issues published previous to this are under a standard copyright licence.

Authors retain copyright of articles published in this journal.

Revenue sources

The cost of publishing Human Ecology Review is covered by Society for Human Ecology member fees in the spirit of open access to knowledge and its distribution. There are no costs to authors for publishing in or submitting an article to HER.

Readers of Human Ecology Review are strongly encouraged to become members by contacting the Society at [email protected] .

Author fees

There are no fees charged to authors for publishing work in Human Ecology Review .

Peer review process

Manuscripts that conform to the author instructions are allocated to an associate editor who has expertise in the area addressed by the manuscript. The associate editor arranges blind peer review and recommends publication, amendment or rejection to the chief editor. The chief editor makes a final decision based on that recommendation. Resubmitted manuscripts may be subject to further review.

Process for identification of and dealing with allegations of research misconduct

If the Editor or an Editorial Board member receives a credible allegation of misconduct by an author, reviewer or editor, then they have a duty to investigate the matter, in consultation with the publisher and Editorial Board. If the claim is substantiated, the Editor will follow the guidelines set out by COPE for retracting or correcting the article in question.

Publication ethics

Authors may be asked to confirm that the ethical dimension of their research was approved by an independent ethics review process within their institution, or as conforming to their national standards for research ethics. If necessary, documented evidence of ethics approval may be asked for. Plagiarism and fraud are not tolerated by the journal and would be dealt with under the ‘research misconduct’ guidelines above.

Duties/responsibilities of authors

To generate a manuscript that conforms to the author guidelines, and to assert that permission has been obtained for any copyright material, and that the research was conducted in accordance with appropriate ethical guidelines and is their own work, unless otherwise acknowledged.

Duties/responsibilities of editors

To publish material suitable for the journal Human Ecology Review in a timely manner and to freely make that material available to readers globally. Editors should be vigilant in guarding against, and reporting, any suspicion of academic malpractice.

Duties/responsibilities of reviewers

To provide a critically engaged, honest, and unbiased recommendation on the suitability of the manuscript for publication in the journal. Reviewers are encouraged to provide feedback to contributing authors in the spirit of supporting and encouraging improvements to their academic skills.

Editorial team

- Editor in Chief: Robert Dyball, Australian National University

- Book Review Editor: Thomas J. Burns, Department of Sociology, University of Oklahoma

- Copy Editors: Ngaire Kinnear, Message Connect Editing Tracy Harwood, Editing and Indexing Services

Contact: [email protected]

Board members

- Jordan Besek, University of Buffalo, SUNY

- Annie Booth, University of Northern British Columbia

- Rich Borden, College of the Atlantic

- Debra Davidson, University of Alberta

- Federico Davila, University of Technology Sydney

- Federico Dickinson, Cinvestav-Merida

- Thomas Dietz, Michigan State University

- Adam Driscoll, University of Wisconsin, La Crosse

- Alan Ewert, Indiana University

- Angela Franz-Balsen, German Society for Human Ecology

- Luc Hens, Flemish Institute for Technological Research

- Cassandra Johnson Gaither, USDA Forest Service

- Andrew K. Jorgenson, Boston College

- Stefano Longo, North Carolina State University

- Priscila Lopes, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

- Andrew MacKenzie, The Australian National University

- Thom Meredith, McGill University

- Angela Mertig, Middle Tennessee State University

- Iva Pires, Universidade Nova de Lisboa

- Liam Phelan, University of Newcastle

- Melinda Storie, Northeastern Illinois University

- Mihnea Tanasescu, Free University of Brussels

- Joanne Vining, University of Illinios, Urbana

- Rachael Wakefield-Rann, University of Technology Sydney

- Cory Whitney, University of Bonn

Manuscripts should be submitted online via http://mstracker.com/submit1.php?jc=her . Authors should follow the guidelines on the Society for Human Ecology (SHE) webpage https://www.societyforhumanecology.org/instructions-for-authors . Attributions should only be made where authors have had a direct intellectual contribution in writing the manuscript.

Human Ecology Review: Volume 27, Number 2 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 27, Number 1 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 26, Number 2 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 26, Number 1 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 25, Number 2 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 25, Number 1 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 24, Number 2 »

Special issue: addressing the great indoors — a transdisciplinary conversation.

Human Ecology Review: Volume 24, Number 1 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 23, Number 2 »

Special issue: human ecology—a gathering of perspectives: portraits from the past—prospects for the future.

Human Ecology Review: Volume 23, Number 1 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 22, Number 2 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 22, Number 1 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 21, Number 2 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 21, Number 1 »

Human Ecology Review: Volume 20, Number 2 »

ANU Press is a globally recognised leader in open-access academic publishing. We produce fully peer-reviewed monographs and journals across a wide range of subject areas, with a special focus on Australian and international policy, Indigenous studies and the Asia-Pacific region.

View the latest ANU Press catalogue

- Search titles

- News & events

- Freedom of information

+61 2 6125 0262

The Australian National University, Canberra

CRICOS Provider: 00120C

ABN: 52 234 063 906

www.anu.edu.au

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Human Ecology (IEG, Second edition, 2018)

2018. Human Ecology, International Encyclopedia of Geography, edited by D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. F. Goodchild, A. Kobayashi, W. Liu and R. A. Marston. doi:10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0477.pub2. Second edition. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0477.pub2

Related Papers

Gregory Knapp

2017.Human Ecology, in The International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment, and Technology, edited by Douglas Richardson et al., pp. 3392-3400. Wiley.

2007. “Human Ecology,” Encyclopedia of Environment and Society, edited by Paul Robbins, Vol. 3, pp. 880-884. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, California.

Landscape and Urban Planning

Roderick J . Lawrence

Clive Hamilton

Ecological Economics

Manfred Max-neef

Todd Lindley