Why Every Educator Needs to Teach Problem-Solving Skills

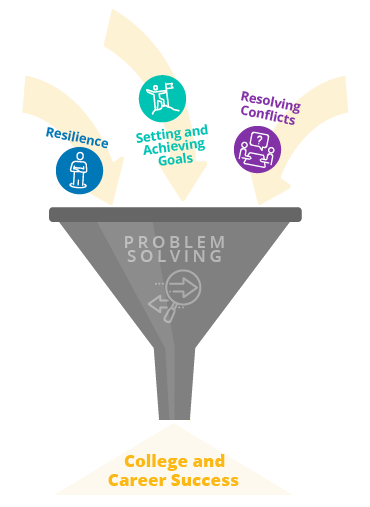

Strong problem-solving skills will help students be more resilient and will increase their academic and career success .

Want to learn more about how to measure and teach students’ higher-order skills, including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication?

Problem-solving skills are essential in school, careers, and life.

Problem-solving skills are important for every student to master. They help individuals navigate everyday life and find solutions to complex issues and challenges. These skills are especially valuable in the workplace, where employees are often required to solve problems and make decisions quickly and effectively.

Problem-solving skills are also needed for students’ personal growth and development because they help individuals overcome obstacles and achieve their goals. By developing strong problem-solving skills, students can improve their overall quality of life and become more successful in their personal and professional endeavors.

Problem-Solving Skills Help Students…

develop resilience.

Problem-solving skills are an integral part of resilience and the ability to persevere through challenges and adversity. To effectively work through and solve a problem, students must be able to think critically and creatively. Critical and creative thinking help students approach a problem objectively, analyze its components, and determine different ways to go about finding a solution.

This process in turn helps students build self-efficacy . When students are able to analyze and solve a problem, this increases their confidence, and they begin to realize the power they have to advocate for themselves and make meaningful change.

When students gain confidence in their ability to work through problems and attain their goals, they also begin to build a growth mindset . According to leading resilience researcher, Carol Dweck, “in a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment.”

Set and Achieve Goals

Students who possess strong problem-solving skills are better equipped to set and achieve their goals. By learning how to identify problems, think critically, and develop solutions, students can become more self-sufficient and confident in their ability to achieve their goals. Additionally, problem-solving skills are used in virtually all fields, disciplines, and career paths, which makes them important for everyone. Building strong problem-solving skills will help students enhance their academic and career performance and become more competitive as they begin to seek full-time employment after graduation or pursue additional education and training.

Resolve Conflicts

In addition to increased social and emotional skills like self-efficacy and goal-setting, problem-solving skills teach students how to cooperate with others and work through disagreements and conflicts. Problem-solving promotes “thinking outside the box” and approaching a conflict by searching for different solutions. This is a very different (and more effective!) method than a more stagnant approach that focuses on placing blame or getting stuck on elements of a situation that can’t be changed.

While it’s natural to get frustrated or feel stuck when working through a conflict, students with strong problem-solving skills will be able to work through these obstacles, think more rationally, and address the situation with a more solution-oriented approach. These skills will be valuable for students in school, their careers, and throughout their lives.

Achieve Success

We are all faced with problems every day. Problems arise in our personal lives, in school and in our jobs, and in our interactions with others. Employers especially are looking for candidates with strong problem-solving skills. In today’s job market, most jobs require the ability to analyze and effectively resolve complex issues. Students with strong problem-solving skills will stand out from other applicants and will have a more desirable skill set.

In a recent opinion piece published by The Hechinger Report , Virgel Hammonds, Chief Learning Officer at KnowledgeWorks, stated “Our world presents increasingly complex challenges. Education must adapt so that it nurtures problem solvers and critical thinkers.” Yet, the “traditional K–12 education system leaves little room for students to engage in real-world problem-solving scenarios.” This is the reason that a growing number of K–12 school districts and higher education institutions are transforming their instructional approach to personalized and competency-based learning, which encourage students to make decisions, problem solve and think critically as they take ownership of and direct their educational journey.

Problem-Solving Skills Can Be Measured and Taught

Research shows that problem-solving skills can be measured and taught. One effective method is through performance-based assessments which require students to demonstrate or apply their knowledge and higher-order skills to create a response or product or do a task.

What Are Performance-Based Assessments?

With the No Child Left Behind Act (2002), the use of standardized testing became the primary way to measure student learning in the U.S. The legislative requirements of this act shifted the emphasis to standardized testing, and this led to a decline in nontraditional testing methods .

But many educators, policy makers, and parents have concerns with standardized tests. Some of the top issues include that they don’t provide feedback on how students can perform better, they don’t value creativity, they are not representative of diverse populations, and they can be disadvantageous to lower-income students.

While standardized tests are still the norm, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona is encouraging states and districts to move away from traditional multiple choice and short response tests and instead use performance-based assessment, competency-based assessments, and other more authentic methods of measuring students abilities and skills rather than rote learning.

Performance-based assessments measure whether students can apply the skills and knowledge learned from a unit of study. Typically, a performance task challenges students to use their higher-order skills to complete a project or process. Tasks can range from an essay to a complex proposal or design.

Preview a Performance-Based Assessment

Want a closer look at how performance-based assessments work? Preview CAE’s K–12 and Higher Education assessments and see how CAE’s tools help students develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and written communication skills.

Performance-Based Assessments Help Students Build and Practice Problem-Solving Skills

In addition to effectively measuring students’ higher-order skills, including their problem-solving skills, performance-based assessments can help students practice and build these skills. Through the assessment process, students are given opportunities to practically apply their knowledge in real-world situations. By demonstrating their understanding of a topic, students are required to put what they’ve learned into practice through activities such as presentations, experiments, and simulations.

This type of problem-solving assessment tool requires students to analyze information and choose how to approach the presented problems. This process enhances their critical thinking skills and creativity, as well as their problem-solving skills. Unlike traditional assessments based on memorization or reciting facts, performance-based assessments focus on the students’ decisions and solutions, and through these tasks students learn to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Performance-based assessments like CAE’s College and Career Readiness Assessment (CRA+) and Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) provide students with in-depth reports that show them which higher-order skills they are strongest in and which they should continue to develop. This feedback helps students and their teachers plan instruction and supports to deepen their learning and improve their mastery of critical skills.

Explore CAE’s Problem-Solving Assessments

CAE offers performance-based assessments that measure student proficiency in higher-order skills including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication.

- College and Career Readiness Assessment (CCRA+) for secondary education and

- Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) for higher education.

Our solution also includes instructional materials, practice models, and professional development.

We can help you create a program to build students’ problem-solving skills that includes:

- Measuring students’ problem-solving skills through a performance-based assessment

- Using the problem-solving assessment data to inform instruction and tailor interventions

- Teaching students problem-solving skills and providing practice opportunities in real-life scenarios

- Supporting educators with quality professional development

Get started with our problem-solving assessment tools to measure and build students’ problem-solving skills today! These skills will be invaluable to students now and in the future.

Ready to Get Started?

Learn more about cae’s suite of products and let’s get started measuring and teaching students important higher-order skills like problem solving..

Teaching problem solving: Let students get ‘stuck’ and ‘unstuck’

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, kate mills and km kate mills literacy interventionist - red bank primary school helyn kim helyn kim former brookings expert @helyn_kim.

October 31, 2017

This is the second in a six-part blog series on teaching 21st century skills , including problem solving , metacognition , critical thinking , and collaboration , in classrooms.

In the real world, students encounter problems that are complex, not well defined, and lack a clear solution and approach. They need to be able to identify and apply different strategies to solve these problems. However, problem solving skills do not necessarily develop naturally; they need to be explicitly taught in a way that can be transferred across multiple settings and contexts.

Here’s what Kate Mills, who taught 4 th grade for 10 years at Knollwood School in New Jersey and is now a Literacy Interventionist at Red Bank Primary School, has to say about creating a classroom culture of problem solvers:

Helping my students grow to be people who will be successful outside of the classroom is equally as important as teaching the curriculum. From the first day of school, I intentionally choose language and activities that help to create a classroom culture of problem solvers. I want to produce students who are able to think about achieving a particular goal and manage their mental processes . This is known as metacognition , and research shows that metacognitive skills help students become better problem solvers.

I begin by “normalizing trouble” in the classroom. Peter H. Johnston teaches the importance of normalizing struggle , of naming it, acknowledging it, and calling it what it is: a sign that we’re growing. The goal is for the students to accept challenge and failure as a chance to grow and do better.

I look for every chance to share problems and highlight how the students— not the teachers— worked through those problems. There is, of course, coaching along the way. For example, a science class that is arguing over whose turn it is to build a vehicle will most likely need a teacher to help them find a way to the balance the work in an equitable way. Afterwards, I make it a point to turn it back to the class and say, “Do you see how you …” By naming what it is they did to solve the problem , students can be more independent and productive as they apply and adapt their thinking when engaging in future complex tasks.

After a few weeks, most of the class understands that the teachers aren’t there to solve problems for the students, but to support them in solving the problems themselves. With that important part of our classroom culture established, we can move to focusing on the strategies that students might need.

Here’s one way I do this in the classroom:

I show the broken escalator video to the class. Since my students are fourth graders, they think it’s hilarious and immediately start exclaiming, “Just get off! Walk!”

When the video is over, I say, “Many of us, probably all of us, are like the man in the video yelling for help when we get stuck. When we get stuck, we stop and immediately say ‘Help!’ instead of embracing the challenge and trying new ways to work through it.” I often introduce this lesson during math class, but it can apply to any area of our lives, and I can refer to the experience and conversation we had during any part of our day.

Research shows that just because students know the strategies does not mean they will engage in the appropriate strategies. Therefore, I try to provide opportunities where students can explicitly practice learning how, when, and why to use which strategies effectively so that they can become self-directed learners.

For example, I give students a math problem that will make many of them feel “stuck”. I will say, “Your job is to get yourselves stuck—or to allow yourselves to get stuck on this problem—and then work through it, being mindful of how you’re getting yourselves unstuck.” As students work, I check-in to help them name their process: “How did you get yourself unstuck?” or “What was your first step? What are you doing now? What might you try next?” As students talk about their process, I’ll add to a list of strategies that students are using and, if they are struggling, help students name a specific process. For instance, if a student says he wrote the information from the math problem down and points to a chart, I will say: “Oh that’s interesting. You pulled the important information from the problem out and organized it into a chart.” In this way, I am giving him the language to match what he did, so that he now has a strategy he could use in other times of struggle.

The charts grow with us over time and are something that we refer to when students are stuck or struggling. They become a resource for students and a way for them to talk about their process when they are reflecting on and monitoring what did or did not work.

For me, as a teacher, it is important that I create a classroom environment in which students are problem solvers. This helps tie struggles to strategies so that the students will not only see value in working harder but in working smarter by trying new and different strategies and revising their process. In doing so, they will more successful the next time around.

Related Content

Esther Care, Helyn Kim, Alvin Vista

October 17, 2017

David Owen, Alvin Vista

November 15, 2017

Loren Clarke, Esther Care

December 5, 2017

Global Education K-12 Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Annelies Goger, Katherine Caves, Hollis Salway

May 16, 2024

Sofoklis Goulas, Isabelle Pula

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Elizabeth D. Steiner, Ashley Woo

Center for Teaching

Teaching problem solving.

Print Version

Tips and Techniques

Expert vs. novice problem solvers, communicate.

- Have students identify specific problems, difficulties, or confusions . Don’t waste time working through problems that students already understand.

- If students are unable to articulate their concerns, determine where they are having trouble by asking them to identify the specific concepts or principles associated with the problem.

- In a one-on-one tutoring session, ask the student to work his/her problem out loud . This slows down the thinking process, making it more accurate and allowing you to access understanding.

- When working with larger groups you can ask students to provide a written “two-column solution.” Have students write up their solution to a problem by putting all their calculations in one column and all of their reasoning (in complete sentences) in the other column. This helps them to think critically about their own problem solving and helps you to more easily identify where they may be having problems. Two-Column Solution (Math) Two-Column Solution (Physics)

Encourage Independence

- Model the problem solving process rather than just giving students the answer. As you work through the problem, consider how a novice might struggle with the concepts and make your thinking clear

- Have students work through problems on their own. Ask directing questions or give helpful suggestions, but provide only minimal assistance and only when needed to overcome obstacles.

- Don’t fear group work ! Students can frequently help each other, and talking about a problem helps them think more critically about the steps needed to solve the problem. Additionally, group work helps students realize that problems often have multiple solution strategies, some that might be more effective than others

Be sensitive

- Frequently, when working problems, students are unsure of themselves. This lack of confidence may hamper their learning. It is important to recognize this when students come to us for help, and to give each student some feeling of mastery. Do this by providing positive reinforcement to let students know when they have mastered a new concept or skill.

Encourage Thoroughness and Patience

- Try to communicate that the process is more important than the answer so that the student learns that it is OK to not have an instant solution. This is learned through your acceptance of his/her pace of doing things, through your refusal to let anxiety pressure you into giving the right answer, and through your example of problem solving through a step-by step process.

Experts (teachers) in a particular field are often so fluent in solving problems from that field that they can find it difficult to articulate the problem solving principles and strategies they use to novices (students) in their field because these principles and strategies are second nature to the expert. To teach students problem solving skills, a teacher should be aware of principles and strategies of good problem solving in his or her discipline .

The mathematician George Polya captured the problem solving principles and strategies he used in his discipline in the book How to Solve It: A New Aspect of Mathematical Method (Princeton University Press, 1957). The book includes a summary of Polya’s problem solving heuristic as well as advice on the teaching of problem solving.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Why STEM? Success Starts With Critical Thinking, Problem-Solving Skills

- Partner Content

- Author: Stephen F. DeAngelis, Enterra Solutions. Stephen F. DeAngelis, Enterra Solutions

Our educational system is tasked with preparing the next-generation to succeed in life. That’s a tall order and it will substantially fail if it doesn’t teach children how to think critically and solve problems. In a post entitled “ STEM Education: Why All the Fuss? ,” I wrote, “Educating students in STEM subjects (if taught correctly) prepares students for life, regardless of the profession they choose to follow. Those subjects teach students how to think critically and how to solve problems — skills that can be used throughout life to help them get through tough times and take advantage of opportunities whenever they appear.”

I’m not alone in making this assessment. Vince Bertram, President and CEO of Project Lead The Way, Inc., feels the same way. “The United States can no longer excuse its poor academic performance by asserting that students in other nations excel in rote learning, while ours are better at problem solving. Recent test results clearly tell a different story.” [“ We Have to Get Serious About Creativity and Problem Solving ,” Huffington Post The Blog , 7 May 2014] Naveen Jain, Entrepreneur and Founder of the World Innovation Institute, adds, “Please don’t get me started on ‘No Child Left Behind.’ It might as well be called ‘All Children Left Behind.’ This system of standardized, rote learning that teaches to a test is exactly the type of education our children don’t need in this world that is plagued by systemic, pervasive and confounding global challenges. Today’s education system does not focus enough on teaching children to solve real world problems and is not interdisciplinary, nor collaborative enough in its approach.” [“ School’s Out for Summer: Rethinking Education for the 21st Century ,” Wall Street Journal , 27 June 2013] He continues:

“Imagine education that is as entertaining and addictive as video games. Sound far-fetched? I believe that this is exactly the idea — driven by dynamic innovation and entrepreneurism — that will help bring our education system out of the stone ages.”

There a numerous examples of how teachers have involved students in problem-solving activities and, as a result, have excited them about education while teaching them how to better cope with the world around them. As Bertram noted above, Americans can no longer boast that we are teaching our children how to solve problems better than the rest of the world. He explains:

“The latest round of international standardized test results showed American students are lagging behind the rest of the developed world not just in math, science and reading , but in problem solving as well. The 2012 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) test examined 44 countries’ students’ problem-solving abilities — American students landed just above the average, but they still scored below many other developed countries, including Britain, Singapore, Korea, Japan, China and Canada.”

Jeevan Vasagar insists that the data shows that countries that teach their children how to solve problems are more successful than those who don’t. It sounds both obvious and sensible; yet, America seems to have turned its back on that approach. “Education is under pressure to respond to a changing world,” writes Vasagar. “As repetitive tasks are eroded by technology and outsourcing, the ability to solve novel problems has become increasingly vital.” [“ Countries that excel at problem-solving encourage critical thinking ,” Financial Times , 19 May 2014] He continues:

“Students from the main western European countries — England, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Belgium — all performed above the average, as did pupils from the Czech Republic and Estonia. In the rest of the rich world, the US, Canada and Australia also performed above average. But the laurels were taken by east Asian territories; Singapore and South Korea performed best, followed by Japan, and the Chinese regions of Macau and Hong Kong. That result poses a challenge to schools in the west. Critics of east Asian education systems attribute their success at maths and science to rote learning. But the OECD’s assessment suggests that schools in east Asia are developing thinking skills as well as providing a solid grounding in core subjects. Across the world, the OECD study found a strong and positive correlation between performance in problem solving and performance in maths, reading and science. In general, the high-performing students were also the ones best able to cope with unfamiliar situations.”

The lesson that needs to be learned here is that, if you want your child to succeed in life, teach him or her how to think critically and solve problems. The best way to do that is to provide them with a good foundation in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). As I noted at the beginning of this article, grounding student in STEM subjects doesn’t mean that other social or liberal arts subjects aren’t important , only that STEM subjects teach life-skills that other disciplines don’t. Bertram explains:

“In America, we must make core subjects like math and science relevant for students, and at the same time, foster creativity, curiosity and a passion for problem solving. That’s what STEM education does. STEM is about using math and science to solve real-world challenges and problems. This applied, project-based way of teaching and learning allows students to understand and appreciate the relevancy of their work to their own lives and the world around them. Once they grasp core concepts, students are able to choose a problem and use their own creativity and curiosity to research, design, test and improve a viable solution.”

One of the reasons that I, along with a few colleagues, founded The Project for STEM Competitiveness , was to help get a project-based, problem-solving approach into schools. As an employer of people with technical skills, I am naturally interested in ensuring that, in the future, I will have an adequate employee pool from which to draw; but, as a parent, I want to ensure that our children are equipped to succeed in a changing world. As I’ve noted in previous articles, many of the jobs our children will asked to fill don’t even exist today. Daisy Christodoulou, an educationalist and the author of Seven Myths about Education , explains that students need exposure to a broad array of disciplines so that they are exposed to the problem-solving skills required in each area. She “argues that such skills are domain specific – they cannot be transferred to an area where our knowledge is limited.” She also believes this will help teach students to think more critically. Vasagar explains:

“Critical thinking is a skill that is impossible to teach directly but must be intertwined with content, Christodoulou argues. … Some argue that placing too strong an emphasis on children acquiring knowledge alone leaves them struggling when faced with more complex problems. Tim Taylor, a former primary school teacher who now trains teachers, says: ‘If you front-load knowledge and leave all the thinking and critical questioning until later, children don’t develop as effective learners.’ There are some generic tools that transfer across disciplines, Taylor argues. ‘What is reading if not a cognitive tool? And that is clearly “transferable”.’ … The way to teach generic skills is to be ‘mindful of it as a teacher’, Taylor suggests. ‘You create opportunities to keep that in the forefront of what you are doing – how is this helping us? How can we use this in another context? That is the point of education, to develop a “growth mindset”,’ he states.”

I agree with Bertram that we must foster educational approaches that appeal to a child’s natural sense of curiosity. He explains:

“Children are born with a natural curiosity. Give a child a toy and watch him or her play for hours. Listen to the questions a child asks. Children have a thirst to understand things. But then they go to school. They are taught how to take tests, how to respond to questions — how to do school. At our own peril, we teach them compliance. We teach them that school isn’t a place for creativity. That must change.”

We are all familiar with the adage “give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” Too often we are feeding our students instead of teaching them how to feed themselves. The disciplines that do that best are STEM-related.

Stephen F. DeAngelis is President and CEO of the cognitive computing firm Enterra Solutions.

Get The Magazine

Subscribe now to get 6 months for $5 - plus a free portable phone charger., get our newsletter, wired's biggest stories, delivered to your inbox., follow us on twitter.

Visit WIRED Photo for our unfiltered take on photography, photographers, and photographic journalism wrd.cm/1IEnjUH

Follow Us On Facebook

Don't miss our latest news, features and videos., we’re on pinterest, see what's inspiring us., follow us on youtube, don't miss out on wired's latest videos..

Teaching Problem-Solving Skills

Many instructors design opportunities for students to solve “problems”. But are their students solving true problems or merely participating in practice exercises? The former stresses critical thinking and decision making skills whereas the latter requires only the application of previously learned procedures.

Problem solving is often broadly defined as "the ability to understand the environment, identify complex problems, review related information to develop, evaluate strategies and implement solutions to build the desired outcome" (Fissore, C. et al, 2021). True problem solving is the process of applying a method – not known in advance – to a problem that is subject to a specific set of conditions and that the problem solver has not seen before, in order to obtain a satisfactory solution.

Below you will find some basic principles for teaching problem solving and one model to implement in your classroom teaching.

Principles for teaching problem solving

- Model a useful problem-solving method . Problem solving can be difficult and sometimes tedious. Show students how to be patient and persistent, and how to follow a structured method, such as Woods’ model described below. Articulate your method as you use it so students see the connections.

- Teach within a specific context . Teach problem-solving skills in the context in which they will be used by students (e.g., mole fraction calculations in a chemistry course). Use real-life problems in explanations, examples, and exams. Do not teach problem solving as an independent, abstract skill.

- Help students understand the problem . In order to solve problems, students need to define the end goal. This step is crucial to successful learning of problem-solving skills. If you succeed at helping students answer the questions “what?” and “why?”, finding the answer to “how?” will be easier.

- Take enough time . When planning a lecture/tutorial, budget enough time for: understanding the problem and defining the goal (both individually and as a class); dealing with questions from you and your students; making, finding, and fixing mistakes; and solving entire problems in a single session.

- Ask questions and make suggestions . Ask students to predict “what would happen if …” or explain why something happened. This will help them to develop analytical and deductive thinking skills. Also, ask questions and make suggestions about strategies to encourage students to reflect on the problem-solving strategies that they use.

- Link errors to misconceptions . Use errors as evidence of misconceptions, not carelessness or random guessing. Make an effort to isolate the misconception and correct it, then teach students to do this by themselves. We can all learn from mistakes.

Woods’ problem-solving model

Define the problem.

- The system . Have students identify the system under study (e.g., a metal bridge subject to certain forces) by interpreting the information provided in the problem statement. Drawing a diagram is a great way to do this.

- Known(s) and concepts . List what is known about the problem, and identify the knowledge needed to understand (and eventually) solve it.

- Unknown(s) . Once you have a list of knowns, identifying the unknown(s) becomes simpler. One unknown is generally the answer to the problem, but there may be other unknowns. Be sure that students understand what they are expected to find.

- Units and symbols . One key aspect in problem solving is teaching students how to select, interpret, and use units and symbols. Emphasize the use of units whenever applicable. Develop a habit of using appropriate units and symbols yourself at all times.

- Constraints . All problems have some stated or implied constraints. Teach students to look for the words "only", "must", "neglect", or "assume" to help identify the constraints.

- Criteria for success . Help students consider, from the beginning, what a logical type of answer would be. What characteristics will it possess? For example, a quantitative problem will require an answer in some form of numerical units (e.g., $/kg product, square cm, etc.) while an optimization problem requires an answer in the form of either a numerical maximum or minimum.

Think about it

- “Let it simmer”. Use this stage to ponder the problem. Ideally, students will develop a mental image of the problem at hand during this stage.

- Identify specific pieces of knowledge . Students need to determine by themselves the required background knowledge from illustrations, examples and problems covered in the course.

- Collect information . Encourage students to collect pertinent information such as conversion factors, constants, and tables needed to solve the problem.

Plan a solution

- Consider possible strategies . Often, the type of solution will be determined by the type of problem. Some common problem-solving strategies are: compute; simplify; use an equation; make a model, diagram, table, or chart; or work backwards.

- Choose the best strategy . Help students to choose the best strategy by reminding them again what they are required to find or calculate.

Carry out the plan

- Be patient . Most problems are not solved quickly or on the first attempt. In other cases, executing the solution may be the easiest step.

- Be persistent . If a plan does not work immediately, do not let students get discouraged. Encourage them to try a different strategy and keep trying.

Encourage students to reflect. Once a solution has been reached, students should ask themselves the following questions:

- Does the answer make sense?

- Does it fit with the criteria established in step 1?

- Did I answer the question(s)?

- What did I learn by doing this?

- Could I have done the problem another way?

If you would like support applying these tips to your own teaching, CTE staff members are here to help. View the CTE Support page to find the most relevant staff member to contact.

- Fissore, C., Marchisio, M., Roman, F., & Sacchet, M. (2021). Development of problem solving skills with Maple in higher education. In: Corless, R.M., Gerhard, J., Kotsireas, I.S. (eds) Maple in Mathematics Education and Research. MC 2020. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1414. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81698-8_15

- Foshay, R., & Kirkley, J. (1998). Principles for Teaching Problem Solving. TRO Learning Inc., Edina MN. (PDF) Principles for Teaching Problem Solving (researchgate.net)

- Hayes, J.R. (1989). The Complete Problem Solver. 2nd Edition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Woods, D.R., Wright, J.D., Hoffman, T.W., Swartman, R.K., Doig, I.D. (1975). Teaching Problem solving Skills.

- Engineering Education. Vol 1, No. 1. p. 238. Washington, DC: The American Society for Engineering Education.

Catalog search

Teaching tip categories.

- Assessment and feedback

- Blended Learning and Educational Technologies

- Career Development

- Course Design

- Course Implementation

- Inclusive Teaching and Learning

- Learning activities

- Support for Student Learning

- Support for TAs

- Learning activities ,

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

- Problem Solving in STEM

Solving problems is a key component of many science, math, and engineering classes. If a goal of a class is for students to emerge with the ability to solve new kinds of problems or to use new problem-solving techniques, then students need numerous opportunities to develop the skills necessary to approach and answer different types of problems. Problem solving during section or class allows students to develop their confidence in these skills under your guidance, better preparing them to succeed on their homework and exams. This page offers advice about strategies for facilitating problem solving during class.

How do I decide which problems to cover in section or class?

In-class problem solving should reinforce the major concepts from the class and provide the opportunity for theoretical concepts to become more concrete. If students have a problem set for homework, then in-class problem solving should prepare students for the types of problems that they will see on their homework. You may wish to include some simpler problems both in the interest of time and to help students gain confidence, but it is ideal if the complexity of at least some of the in-class problems mirrors the level of difficulty of the homework. You may also want to ask your students ahead of time which skills or concepts they find confusing, and include some problems that are directly targeted to their concerns.

You have given your students a problem to solve in class. What are some strategies to work through it?

- Try to give your students a chance to grapple with the problems as much as possible. Offering them the chance to do the problem themselves allows them to learn from their mistakes in the presence of your expertise as their teacher. (If time is limited, they may not be able to get all the way through multi-step problems, in which case it can help to prioritize giving them a chance to tackle the most challenging steps.)

- When you do want to teach by solving the problem yourself at the board, talk through the logic of how you choose to apply certain approaches to solve certain problems. This way you can externalize the type of thinking you hope your students internalize when they solve similar problems themselves.

- Start by setting up the problem on the board (e.g you might write down key variables and equations; draw a figure illustrating the question). Ask students to start solving the problem, either independently or in small groups. As they are working on the problem, walk around to hear what they are saying and see what they are writing down. If several students seem stuck, it might be a good to collect the whole class again to clarify any confusion. After students have made progress, bring the everyone back together and have students guide you as to what to write on the board.

- It can help to first ask students to work on the problem by themselves for a minute, and then get into small groups to work on the problem collaboratively.

- If you have ample board space, have students work in small groups at the board while solving the problem. That way you can monitor their progress by standing back and watching what they put up on the board.

- If you have several problems you would like to have the students practice, but not enough time for everyone to do all of them, you can assign different groups of students to work on different – but related - problems.

When do you want students to work in groups to solve problems?

- Don’t ask students to work in groups for straightforward problems that most students could solve independently in a short amount of time.

- Do have students work in groups for thought-provoking problems, where students will benefit from meaningful collaboration.

- Even in cases where you plan to have students work in groups, it can be useful to give students some time to work on their own before collaborating with others. This ensures that every student engages with the problem and is ready to contribute to a discussion.

What are some benefits of having students work in groups?

- Students bring different strengths, different knowledge, and different ideas for how to solve a problem; collaboration can help students work through problems that are more challenging than they might be able to tackle on their own.

- In working in a group, students might consider multiple ways to approach a problem, thus enriching their repertoire of strategies.

- Students who think they understand the material will gain a deeper understanding by explaining concepts to their peers.

What are some strategies for helping students to form groups?

- Instruct students to work with the person (or people) sitting next to them.

- Count off. (e.g. 1, 2, 3, 4; all the 1’s find each other and form a group, etc)

- Hand out playing cards; students need to find the person with the same number card. (There are many variants to this. For example, you can print pictures of images that go together [rain and umbrella]; each person gets a card and needs to find their partner[s].)

- Based on what you know about the students, assign groups in advance. List the groups on the board.

- Note: Always have students take the time to introduce themselves to each other in a new group.

What should you do while your students are working on problems?

- Walk around and talk to students. Observing their work gives you a sense of what people understand and what they are struggling with. Answer students’ questions, and ask them questions that lead in a productive direction if they are stuck.

- If you discover that many people have the same question—or that someone has a misunderstanding that others might have—you might stop everyone and discuss a key idea with the entire class.

After students work on a problem during class, what are strategies to have them share their answers and their thinking?

- Ask for volunteers to share answers. Depending on the nature of the problem, student might provide answers verbally or by writing on the board. As a variant, for questions where a variety of answers are relevant, ask for at least three volunteers before anyone shares their ideas.

- Use online polling software for students to respond to a multiple-choice question anonymously.

- If students are working in groups, assign reporters ahead of time. For example, the person with the next birthday could be responsible for sharing their group’s work with the class.

- Cold call. To reduce student anxiety about cold calling, it can help to identify students who seem to have the correct answer as you were walking around the class and checking in on their progress solving the assigned problem. You may even want to warn the student ahead of time: "This is a great answer! Do you mind if I call on you when we come back together as a class?"

- Have students write an answer on a notecard that they turn in to you. If your goal is to understand whether students in general solved a problem correctly, the notecards could be submitted anonymously; if you wish to assess individual students’ work, you would want to ask students to put their names on their notecard.

- Use a jigsaw strategy, where you rearrange groups such that each new group is comprised of people who came from different initial groups and had solved different problems. Students now are responsible for teaching the other students in their new group how to solve their problem.

- Have a representative from each group explain their problem to the class.

- Have a representative from each group draw or write the answer on the board.

What happens if a student gives a wrong answer?

- Ask for their reasoning so that you can understand where they went wrong.

- Ask if anyone else has other ideas. You can also ask this sometimes when an answer is right.

- Cultivate an environment where it’s okay to be wrong. Emphasize that you are all learning together, and that you learn through making mistakes.

- Do make sure that you clarify what the correct answer is before moving on.

- Once the correct answer is given, go through some answer-checking techniques that can distinguish between correct and incorrect answers. This can help prepare students to verify their future work.

How can you make your classroom inclusive?

- The goal is that everyone is thinking, talking, and sharing their ideas, and that everyone feels valued and respected. Use a variety of teaching strategies (independent work and group work; allow students to talk to each other before they talk to the class). Create an environment where it is normal to struggle and make mistakes.

- See Kimberly Tanner’s article on strategies to promoste student engagement and cultivate classroom equity.

A few final notes…

- Make sure that you have worked all of the problems and also thought about alternative approaches to solving them.

- Board work matters. You should have a plan beforehand of what you will write on the board, where, when, what needs to be added, and what can be erased when. If students are going to write their answers on the board, you need to also have a plan for making sure that everyone gets to the correct answer. Students will copy what is on the board and use it as their notes for later study, so correct and logical information must be written there.

For more information...

Tipsheet: Problem Solving in STEM Sections

Tanner, K. D. (2013). Structure matters: twenty-one teaching strategies to promote student engagement and cultivate classroom equity . CBE-Life Sciences Education, 12(3), 322-331.

- Designing Your Course

- A Teaching Timeline: From Pre-Term Planning to the Final Exam

- The First Day of Class

- Group Agreements

- Classroom Debate

- Flipped Classrooms

- Leading Discussions

- Polling & Clickers

- Teaching with Cases

- Engaged Scholarship

- Devices in the Classroom

- Beyond the Classroom

- On Professionalism

- Getting Feedback

- Equitable & Inclusive Teaching

- Advising and Mentoring

- Teaching and Your Career

- Teaching Remotely

- Tools and Platforms

- The Science of Learning

- Bok Publications

- Other Resources Around Campus

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2023

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature

- Enwei Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6424-8169 1 ,

- Wei Wang 1 &

- Qingxia Wang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 16 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

15 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely embraced in the classroom instruction of critical thinking, which is regarded as the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education as well as a key competence for learners in the 21st century. However, the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking remains uncertain. This current research presents the major findings of a meta-analysis of 36 pieces of the literature revealed in worldwide educational periodicals during the 21st century to identify the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and to determine, based on evidence, whether and to what extent collaborative problem solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. The findings show that (1) collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster students’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]); (2) in respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem solving can significantly and successfully enhance students’ attitudinal tendencies (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.58, 0.82]); and (3) the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have an impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. On the basis of these results, recommendations are made for further study and instruction to better support students’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of artificial intelligence on human loss in decision making, laziness and safety in education

Interviews in the social sciences

Principal component analysis

Introduction.

Although critical thinking has a long history in research, the concept of critical thinking, which is regarded as an essential competence for learners in the 21st century, has recently attracted more attention from researchers and teaching practitioners (National Research Council, 2012 ). Critical thinking should be the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education (Peng and Deng, 2017 ) because students with critical thinking can not only understand the meaning of knowledge but also effectively solve practical problems in real life even after knowledge is forgotten (Kek and Huijser, 2011 ). The definition of critical thinking is not universal (Ennis, 1989 ; Castle, 2009 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). In general, the definition of critical thinking is a self-aware and self-regulated thought process (Facione, 1990 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). It refers to the cognitive skills needed to interpret, analyze, synthesize, reason, and evaluate information as well as the attitudinal tendency to apply these abilities (Halpern, 2001 ). The view that critical thinking can be taught and learned through curriculum teaching has been widely supported by many researchers (e.g., Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), leading to educators’ efforts to foster it among students. In the field of teaching practice, there are three types of courses for teaching critical thinking (Ennis, 1989 ). The first is an independent curriculum in which critical thinking is taught and cultivated without involving the knowledge of specific disciplines; the second is an integrated curriculum in which critical thinking is integrated into the teaching of other disciplines as a clear teaching goal; and the third is a mixed curriculum in which critical thinking is taught in parallel to the teaching of other disciplines for mixed teaching training. Furthermore, numerous measuring tools have been developed by researchers and educators to measure critical thinking in the context of teaching practice. These include standardized measurement tools, such as WGCTA, CCTST, CCTT, and CCTDI, which have been verified by repeated experiments and are considered effective and reliable by international scholars (Facione and Facione, 1992 ). In short, descriptions of critical thinking, including its two dimensions of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, different types of teaching courses, and standardized measurement tools provide a complex normative framework for understanding, teaching, and evaluating critical thinking.

Cultivating critical thinking in curriculum teaching can start with a problem, and one of the most popular critical thinking instructional approaches is problem-based learning (Liu et al., 2020 ). Duch et al. ( 2001 ) noted that problem-based learning in group collaboration is progressive active learning, which can improve students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Collaborative problem-solving is the organic integration of collaborative learning and problem-based learning, which takes learners as the center of the learning process and uses problems with poor structure in real-world situations as the starting point for the learning process (Liang et al., 2017 ). Students learn the knowledge needed to solve problems in a collaborative group, reach a consensus on problems in the field, and form solutions through social cooperation methods, such as dialogue, interpretation, questioning, debate, negotiation, and reflection, thus promoting the development of learners’ domain knowledge and critical thinking (Cindy, 2004 ; Liang et al., 2017 ).

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely used in the teaching practice of critical thinking, and several studies have attempted to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature on critical thinking from various perspectives. However, little attention has been paid to the impact of collaborative problem-solving on critical thinking. Therefore, the best approach for developing and enhancing critical thinking throughout collaborative problem-solving is to examine how to implement critical thinking instruction; however, this issue is still unexplored, which means that many teachers are incapable of better instructing critical thinking (Leng and Lu, 2020 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). For example, Huber ( 2016 ) provided the meta-analysis findings of 71 publications on gaining critical thinking over various time frames in college with the aim of determining whether critical thinking was truly teachable. These authors found that learners significantly improve their critical thinking while in college and that critical thinking differs with factors such as teaching strategies, intervention duration, subject area, and teaching type. The usefulness of collaborative problem-solving in fostering students’ critical thinking, however, was not determined by this study, nor did it reveal whether there existed significant variations among the different elements. A meta-analysis of 31 pieces of educational literature was conducted by Liu et al. ( 2020 ) to assess the impact of problem-solving on college students’ critical thinking. These authors found that problem-solving could promote the development of critical thinking among college students and proposed establishing a reasonable group structure for problem-solving in a follow-up study to improve students’ critical thinking. Additionally, previous empirical studies have reached inconclusive and even contradictory conclusions about whether and to what extent collaborative problem-solving increases or decreases critical thinking levels. As an illustration, Yang et al. ( 2008 ) carried out an experiment on the integrated curriculum teaching of college students based on a web bulletin board with the goal of fostering participants’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These authors’ research revealed that through sharing, debating, examining, and reflecting on various experiences and ideas, collaborative problem-solving can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking in real-life problem situations. In contrast, collaborative problem-solving had a positive impact on learners’ interaction and could improve learning interest and motivation but could not significantly improve students’ critical thinking when compared to traditional classroom teaching, according to research by Naber and Wyatt ( 2014 ) and Sendag and Odabasi ( 2009 ) on undergraduate and high school students, respectively.

The above studies show that there is inconsistency regarding the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a thorough and trustworthy review to detect and decide whether and to what degree collaborative problem-solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. Meta-analysis is a quantitative analysis approach that is utilized to examine quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. This approach characterizes the effectiveness of its impact by averaging the effect sizes of numerous qualitative studies in an effort to reduce the uncertainty brought on by independent research and produce more conclusive findings (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ).

This paper used a meta-analytic approach and carried out a meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking in order to make a contribution to both research and practice. The following research questions were addressed by this meta-analysis:

What is the overall effect size of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills)?

How are the disparities between the study conclusions impacted by various moderating variables if the impacts of various experimental designs in the included studies are heterogeneous?

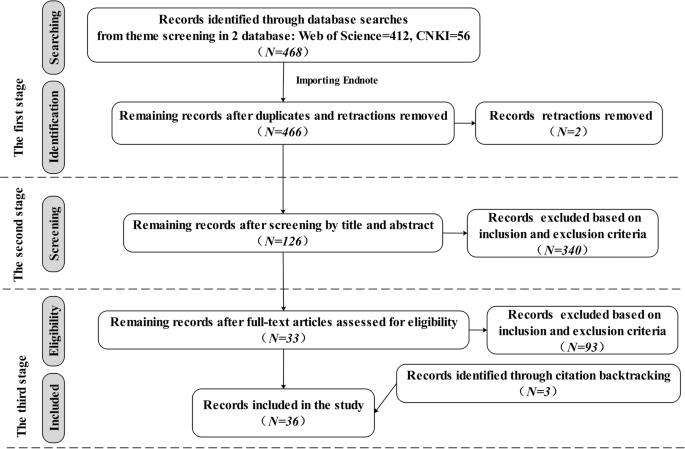

This research followed the strict procedures (e.g., database searching, identification, screening, eligibility, merging, duplicate removal, and analysis of included studies) of Cooper’s ( 2010 ) proposed meta-analysis approach for examining quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. The relevant empirical research that appeared in worldwide educational periodicals within the 21st century was subjected to this meta-analysis using Rev-Man 5.4. The consistency of the data extracted separately by two researchers was tested using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, and a publication bias test and a heterogeneity test were run on the sample data to ascertain the quality of this meta-analysis.

Data sources and search strategies

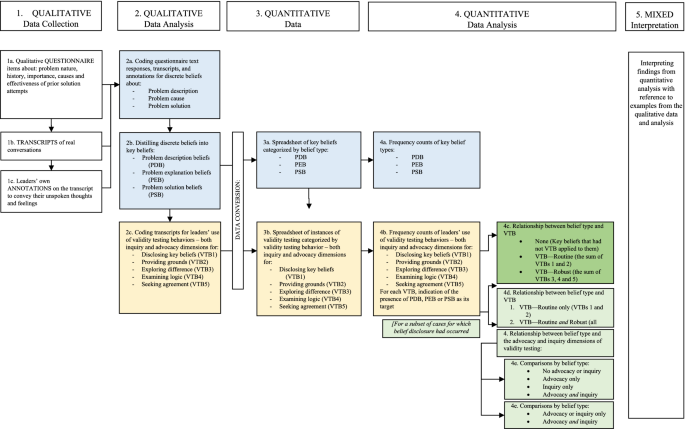

There were three stages to the data collection process for this meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 1 , which shows the number of articles included and eliminated during the selection process based on the statement and study eligibility criteria.

This flowchart shows the number of records identified, included and excluded in the article.

First, the databases used to systematically search for relevant articles were the journal papers of the Web of Science Core Collection and the Chinese Core source journal, as well as the Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI) source journal papers included in CNKI. These databases were selected because they are credible platforms that are sources of scholarly and peer-reviewed information with advanced search tools and contain literature relevant to the subject of our topic from reliable researchers and experts. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the Web of Science was “TS = (((“critical thinking” or “ct” and “pretest” or “posttest”) or (“critical thinking” or “ct” and “control group” or “quasi experiment” or “experiment”)) and (“collaboration” or “collaborative learning” or “CSCL”) and (“problem solving” or “problem-based learning” or “PBL”))”. The research area was “Education Educational Research”, and the search period was “January 1, 2000, to December 30, 2021”. A total of 412 papers were obtained. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the CNKI was “SU = (‘critical thinking’*‘collaboration’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘collaborative learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘CSCL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem solving’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem-based learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘PBL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem oriented’) AND FT = (‘experiment’ + ‘quasi experiment’ + ‘pretest’ + ‘posttest’ + ‘empirical study’)” (translated into Chinese when searching). A total of 56 studies were found throughout the search period of “January 2000 to December 2021”. From the databases, all duplicates and retractions were eliminated before exporting the references into Endnote, a program for managing bibliographic references. In all, 466 studies were found.

Second, the studies that matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were chosen by two researchers after they had reviewed the abstracts and titles of the gathered articles, yielding a total of 126 studies.

Third, two researchers thoroughly reviewed each included article’s whole text in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, a snowball search was performed using the references and citations of the included articles to ensure complete coverage of the articles. Ultimately, 36 articles were kept.

Two researchers worked together to carry out this entire process, and a consensus rate of almost 94.7% was reached after discussion and negotiation to clarify any emerging differences.

Eligibility criteria

Since not all the retrieved studies matched the criteria for this meta-analysis, eligibility criteria for both inclusion and exclusion were developed as follows:

The publication language of the included studies was limited to English and Chinese, and the full text could be obtained. Articles that did not meet the publication language and articles not published between 2000 and 2021 were excluded.

The research design of the included studies must be empirical and quantitative studies that can assess the effect of collaborative problem-solving on the development of critical thinking. Articles that could not identify the causal mechanisms by which collaborative problem-solving affects critical thinking, such as review articles and theoretical articles, were excluded.

The research method of the included studies must feature a randomized control experiment or a quasi-experiment, or a natural experiment, which have a higher degree of internal validity with strong experimental designs and can all plausibly provide evidence that critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving are causally related. Articles with non-experimental research methods, such as purely correlational or observational studies, were excluded.

The participants of the included studies were only students in school, including K-12 students and college students. Articles in which the participants were non-school students, such as social workers or adult learners, were excluded.

The research results of the included studies must mention definite signs that may be utilized to gauge critical thinking’s impact (e.g., sample size, mean value, or standard deviation). Articles that lacked specific measurement indicators for critical thinking and could not calculate the effect size were excluded.

Data coding design

In order to perform a meta-analysis, it is necessary to collect the most important information from the articles, codify that information’s properties, and convert descriptive data into quantitative data. Therefore, this study designed a data coding template (see Table 1 ). Ultimately, 16 coding fields were retained.

The designed data-coding template consisted of three pieces of information. Basic information about the papers was included in the descriptive information: the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper.

The variable information for the experimental design had three variables: the independent variable (instruction method), the dependent variable (critical thinking), and the moderating variable (learning stage, teaching type, intervention duration, learning scaffold, group size, measuring tool, and subject area). Depending on the topic of this study, the intervention strategy, as the independent variable, was coded into collaborative and non-collaborative problem-solving. The dependent variable, critical thinking, was coded as a cognitive skill and an attitudinal tendency. And seven moderating variables were created by grouping and combining the experimental design variables discovered within the 36 studies (see Table 1 ), where learning stages were encoded as higher education, high school, middle school, and primary school or lower; teaching types were encoded as mixed courses, integrated courses, and independent courses; intervention durations were encoded as 0–1 weeks, 1–4 weeks, 4–12 weeks, and more than 12 weeks; group sizes were encoded as 2–3 persons, 4–6 persons, 7–10 persons, and more than 10 persons; learning scaffolds were encoded as teacher-supported learning scaffold, technique-supported learning scaffold, and resource-supported learning scaffold; measuring tools were encoded as standardized measurement tools (e.g., WGCTA, CCTT, CCTST, and CCTDI) and self-adapting measurement tools (e.g., modified or made by researchers); and subject areas were encoded according to the specific subjects used in the 36 included studies.

The data information contained three metrics for measuring critical thinking: sample size, average value, and standard deviation. It is vital to remember that studies with various experimental designs frequently adopt various formulas to determine the effect size. And this paper used Morris’ proposed standardized mean difference (SMD) calculation formula ( 2008 , p. 369; see Supplementary Table S3 ).

Procedure for extracting and coding data

According to the data coding template (see Table 1 ), the 36 papers’ information was retrieved by two researchers, who then entered them into Excel (see Supplementary Table S1 ). The results of each study were extracted separately in the data extraction procedure if an article contained numerous studies on critical thinking, or if a study assessed different critical thinking dimensions. For instance, Tiwari et al. ( 2010 ) used four time points, which were viewed as numerous different studies, to examine the outcomes of critical thinking, and Chen ( 2013 ) included the two outcome variables of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, which were regarded as two studies. After discussion and negotiation during data extraction, the two researchers’ consistency test coefficients were roughly 93.27%. Supplementary Table S2 details the key characteristics of the 36 included articles with 79 effect quantities, including descriptive information (e.g., the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper), variable information (e.g., independent variables, dependent variables, and moderating variables), and data information (e.g., mean values, standard deviations, and sample size). Following that, testing for publication bias and heterogeneity was done on the sample data using the Rev-Man 5.4 software, and then the test results were used to conduct a meta-analysis.

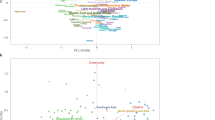

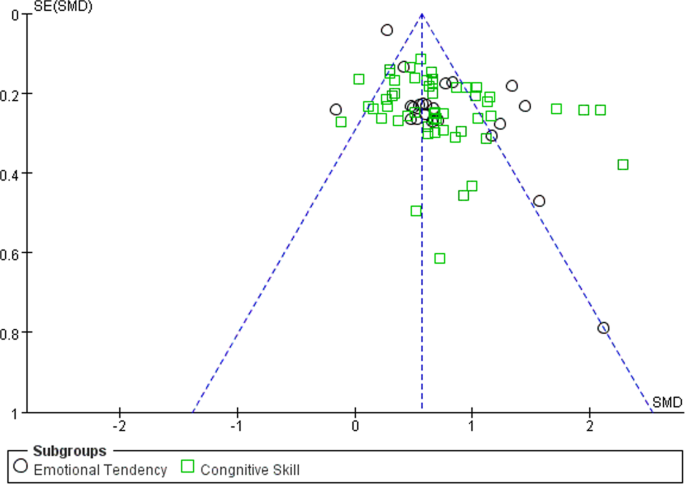

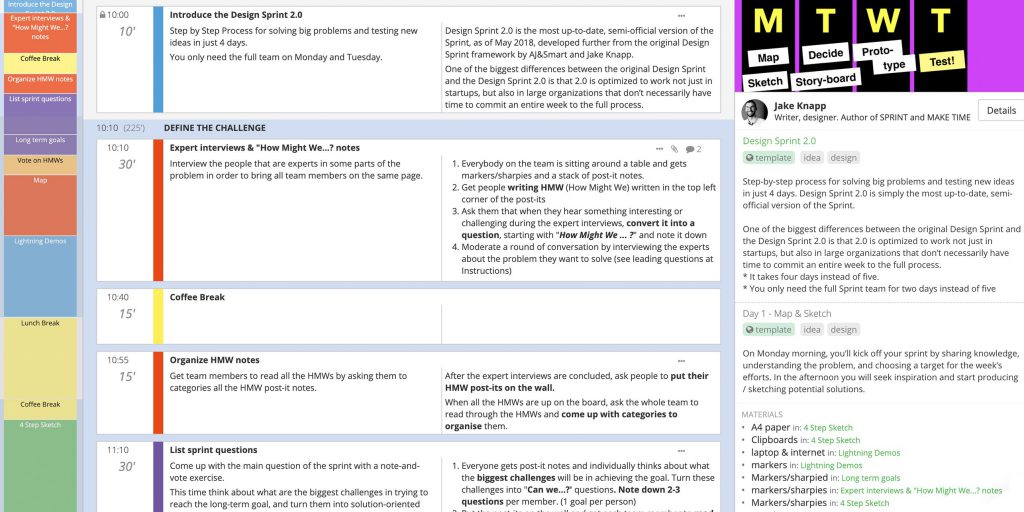

Publication bias test

When the sample of studies included in a meta-analysis does not accurately reflect the general status of research on the relevant subject, publication bias is said to be exhibited in this research. The reliability and accuracy of the meta-analysis may be impacted by publication bias. Due to this, the meta-analysis needs to check the sample data for publication bias (Stewart et al., 2006 ). A popular method to check for publication bias is the funnel plot; and it is unlikely that there will be publishing bias when the data are equally dispersed on either side of the average effect size and targeted within the higher region. The data are equally dispersed within the higher portion of the efficient zone, consistent with the funnel plot connected with this analysis (see Fig. 2 ), indicating that publication bias is unlikely in this situation.

This funnel plot shows the result of publication bias of 79 effect quantities across 36 studies.

Heterogeneity test

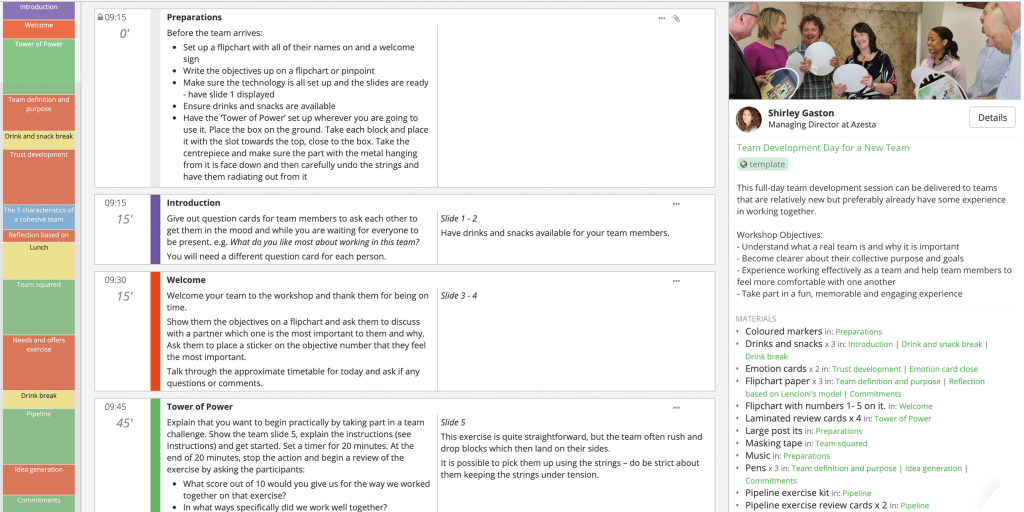

To select the appropriate effect models for the meta-analysis, one might use the results of a heterogeneity test on the data effect sizes. In a meta-analysis, it is common practice to gauge the degree of data heterogeneity using the I 2 value, and I 2 ≥ 50% is typically understood to denote medium-high heterogeneity, which calls for the adoption of a random effect model; if not, a fixed effect model ought to be applied (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ). The findings of the heterogeneity test in this paper (see Table 2 ) revealed that I 2 was 86% and displayed significant heterogeneity ( P < 0.01). To ensure accuracy and reliability, the overall effect size ought to be calculated utilizing the random effect model.

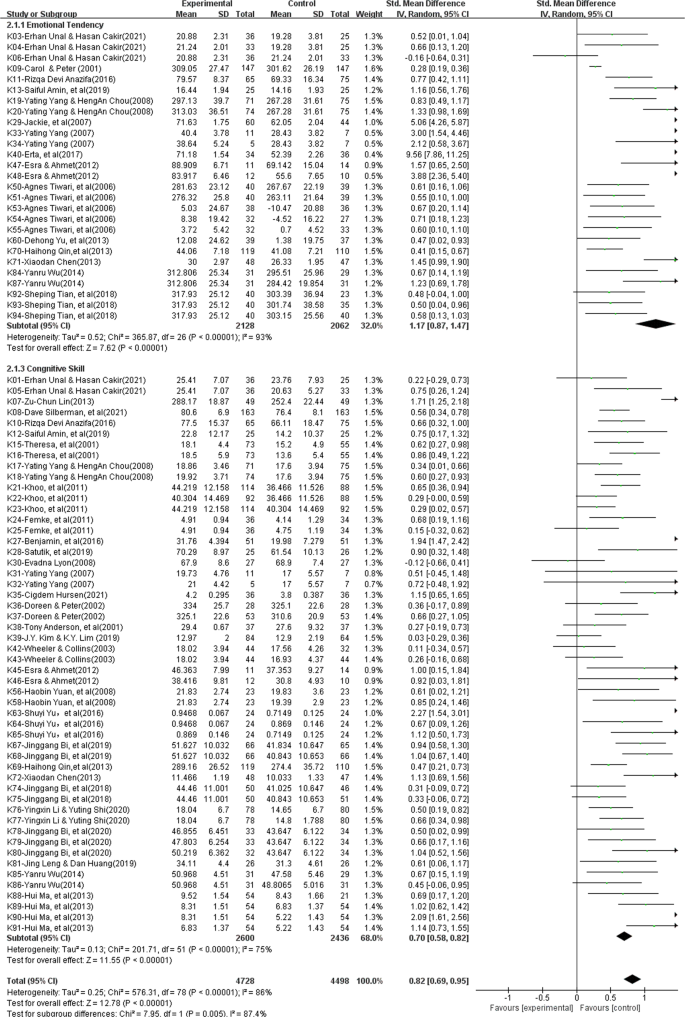

The analysis of the overall effect size

This meta-analysis utilized a random effect model to examine 79 effect quantities from 36 studies after eliminating heterogeneity. In accordance with Cohen’s criterion (Cohen, 1992 ), it is abundantly clear from the analysis results, which are shown in the forest plot of the overall effect (see Fig. 3 ), that the cumulative impact size of cooperative problem-solving is 0.82, which is statistically significant ( z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]), and can encourage learners to practice critical thinking.

This forest plot shows the analysis result of the overall effect size across 36 studies.

In addition, this study examined two distinct dimensions of critical thinking to better understand the precise contributions that collaborative problem-solving makes to the growth of critical thinking. The findings (see Table 3 ) indicate that collaborative problem-solving improves cognitive skills (ES = 0.70) and attitudinal tendency (ES = 1.17), with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.95, P < 0.01). Although collaborative problem-solving improves both dimensions of critical thinking, it is essential to point out that the improvements in students’ attitudinal tendency are much more pronounced and have a significant comprehensive effect (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]), whereas gains in learners’ cognitive skill are slightly improved and are just above average. (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

The analysis of moderator effect size

The whole forest plot’s 79 effect quantities underwent a two-tailed test, which revealed significant heterogeneity ( I 2 = 86%, z = 12.78, P < 0.01), indicating differences between various effect sizes that may have been influenced by moderating factors other than sampling error. Therefore, exploring possible moderating factors that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis, such as the learning stage, learning scaffold, teaching type, group size, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, in order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking. The findings (see Table 4 ) indicate that various moderating factors have advantageous effects on critical thinking. In this situation, the subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01), and teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05) are all significant moderators that can be applied to support the cultivation of critical thinking. However, since the learning stage and the measuring tools did not significantly differ among intergroup (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05, and chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05), we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These are the precise outcomes, as follows:

Various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively, without significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05). High school was first on the list of effect sizes (ES = 1.36, P < 0.01), then higher education (ES = 0.78, P < 0.01), and middle school (ES = 0.73, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the learning stage’s beneficial influence on cultivating learners’ critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is essential for cultivating critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Different teaching types had varying degrees of positive impact on critical thinking, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05). The effect size was ranked as follows: mixed courses (ES = 1.34, P < 0.01), integrated courses (ES = 0.81, P < 0.01), and independent courses (ES = 0.27, P < 0.01). These results indicate that the most effective approach to cultivate critical thinking utilizing collaborative problem solving is through the teaching type of mixed courses.

Various intervention durations significantly improved critical thinking, and there were significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01). The effect sizes related to this variable showed a tendency to increase with longer intervention durations. The improvement in critical thinking reached a significant level (ES = 0.85, P < 0.01) after more than 12 weeks of training. These findings indicate that the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated, with a longer intervention duration having a greater effect.

Different learning scaffolds influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01). The resource-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.69, P < 0.01) acquired a medium-to-higher level of impact, the technique-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.63, P < 0.01) also attained a medium-to-higher level of impact, and the teacher-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.92, P < 0.01) displayed a high level of significant impact. These results show that the learning scaffold with teacher support has the greatest impact on cultivating critical thinking.

Various group sizes influenced critical thinking positively, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05). Critical thinking showed a general declining trend with increasing group size. The overall effect size of 2–3 people in this situation was the biggest (ES = 0.99, P < 0.01), and when the group size was greater than 7 people, the improvement in critical thinking was at the lower-middle level (ES < 0.5, P < 0.01). These results show that the impact on critical thinking is positively connected with group size, and as group size grows, so does the overall impact.

Various measuring tools influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05). In this situation, the self-adapting measurement tools obtained an upper-medium level of effect (ES = 0.78), whereas the complete effect size of the standardized measurement tools was the largest, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 0.84, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the beneficial influence of the measuring tool on cultivating critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Different subject areas had a greater impact on critical thinking, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05). Mathematics had the greatest overall impact, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 1.68, P < 0.01), followed by science (ES = 1.25, P < 0.01) and medical science (ES = 0.87, P < 0.01), both of which also achieved a significant level of effect. Programming technology was the least effective (ES = 0.39, P < 0.01), only having a medium-low degree of effect compared to education (ES = 0.72, P < 0.01) and other fields (such as language, art, and social sciences) (ES = 0.58, P < 0.01). These results suggest that scientific fields (e.g., mathematics, science) may be the most effective subject areas for cultivating critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

According to this meta-analysis, using collaborative problem-solving as an intervention strategy in critical thinking teaching has a considerable amount of impact on cultivating learners’ critical thinking as a whole and has a favorable promotional effect on the two dimensions of critical thinking. According to certain studies, collaborative problem solving, the most frequently used critical thinking teaching strategy in curriculum instruction can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking (e.g., Liang et al., 2017 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Cindy, 2004 ). This meta-analysis provides convergent data support for the above research views. Thus, the findings of this meta-analysis not only effectively address the first research query regarding the overall effect of cultivating critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills) utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving, but also enhance our confidence in cultivating critical thinking by using collaborative problem-solving intervention approach in the context of classroom teaching.