- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

James Lovelock (b. 1919) English scientist

sulphur cycle

biogeochemical cycle

Thomas A. Sebeok (1920—2001)

See all related overviews in Oxford Reference »

More Like This

Show all results sharing these subjects:

- Environmental Science

Gaia hypothesis

Quick reference.

The theory, based on an idea put forward by the British scientist James Ephraim Lovelock (1919– ), that the whole earth, including both its biotic (living) and abiotic (nonliving) components, functions as a single self-regulating system. Named after the Greek earth goddess, it proposes that the responses of living organisms to environmental conditions ultimately bring about changes that make the earth better adapted to support life; the system would rid itself of any species that adversely affects the environment. The theory has found favour with many conservationists.

From: Gaia hypothesis in A Dictionary of Biology »

Subjects: Science and technology — Environmental Science

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries, gaia hypothesis.

View all reference entries »

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'Gaia hypothesis' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 18 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.180.204]

- 81.177.180.204

Character limit 500 /500

Scientists finally have an explanation for the ‘Gaia puzzle’

Associate Professor of Sustainability Science, University of Southampton

Director, Global Systems Institute, University of Exeter

Disclosure statement

Tim Lenton works for the University of Exeter and receives funding from the Royal Society (Wolfson Research Merit Award) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NE/P013651/1).

James Dyke does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Southampton and University of Exeter provide funding as members of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

We will likely never know how life on Earth started. Perhaps in a shallow sunlit pool. Or in the crushing ocean depths miles beneath the surface near fissures in the Earth’s crust that spewed out hot mineral-rich soup. While there is good evidence for life at least 3.7 billion years ago , we don’t know precisely when it started.

But these passing aeons have produced something perhaps even more remarkable: life has persisted. Despite massive asteroid impacts, cataclysmic volcano activity and extreme climate change, life has managed to not just cling on to our rocky world but to thrive.

How did this happen? Research we recently published with colleagues in Trends in Ecology and Evolution offers an important part of the answer, providing a new explanation for the Gaia hypothesis.

Developed by scientist and inventor James Lovelock , and microbiologist Lynn Margulis , the Gaia hypothesis originally proposed that life, through its interactions with the Earth’s crust, oceans, and atmosphere, produced a stabilising effect on conditions on the surface of the planet – in particular the composition of the atmosphere and the climate. With such a self-regulating process in place, life has been able to survive under conditions which would have wiped it out on non-regulating planets.

Lovelock formulated the Gaia hypothesis while working for NASA in the 1960s. He recognised that life has not been a passive passenger on Earth. Rather it has profoundly remodelled the planet, creating new rocks such as limestone, affecting the atmosphere by producing oxygen, and driving the cycles of elements such as nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon. Human-produced climate change, which is largely a consequence of us burning fossil fuels and so releasing carbon dioxide, is just the latest way life affects the Earth system.

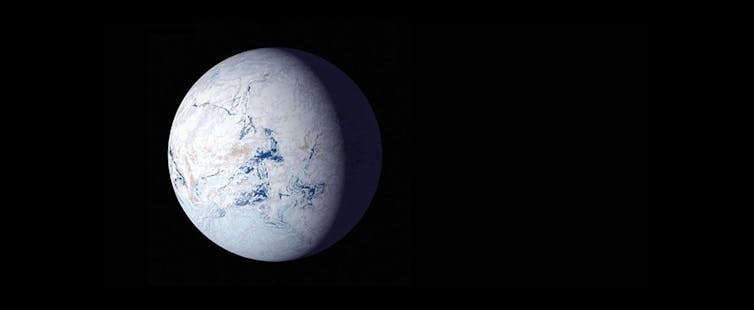

While it is now accepted that life is a powerful force on the planet, the Gaia hypothesis remains controversial. Despite evidence that surface temperatures have, bar a few notable exceptions, remained within the range required for widespread liquid water, many scientists attribute this simply to good luck. If the Earth had descended completely into an ice house or hot house (think Mars or Venus) then life would have become extinct and we would not be here to wonder about how it had persisted for so long. This is a form of anthropic selection argument that says there is nothing to explain.

Clearly, life on Earth has been lucky. In the first instance, the Earth is within the habitable zone – it orbits the sun at a distance that produces surface temperatures required for liquid water. There are alternative and perhaps more exotic forms of life in the universe, but life as we know it requires water. Life has also been lucky to avoid very large asteroid impacts. A lump of rock significantly larger than the one that lead to the demise of the dinosaurs some 66m years ago could have completely sterilised the Earth.

But what if life had been able to push down on one side of the scales of fortune? What if life in some sense made its own luck by reducing the impacts of planetary-scale disturbances? This leads to the central outstanding issue in the Gaia hypothesis: how is planetary self-regulation meant to work?

While natural selection is a powerful explanatory mechanism that can account for much of the change we observe in species over time, we have been lacking a theory that could explain how the living and non-living elements of a planet produce self-regulation. Consequently the Gaia hypothesis has typically been considered as interesting but speculative – and not grounded in any testable theory .

Selecting for stability

We think there is finally an explanation for the Gaia hypothesis. The mechanism is based on “ sequential selection ”, a concept first suggested by climate scientist Richard Betts in the early 2000s. In principle it’s very simple. As life emerges on a planet it begins to affect environmental conditions, and this can organise into stabilising states which act like a thermostat and tend to persist, or destabilising runaway states such as the snowball Earth events that nearly extinguished the beginnings of complex life more than 600m years ago.

If it stabilises then the scene is set for further biological evolution that will in time reconfigure the set of interactions between life and planet. A famous example is the origin of oxygen-producing photosynthesis around 3 billion years ago, in a world previously devoid of oxygen. If these newer interactions are stabilising, then the planetary-system continues to self-regulate. But new interactions can also produce disruptions and runaway feedbacks. In the case of photosynthesis it led to an abrupt rise in atmospheric oxygen levels in the “ Great Oxidation Event ” around 2.3 billion years ago. This was one of the rare periods in Earth’s history where the change was so pronounced it probably wiped out much of the incumbent biosphere, effectively rebooting the system.

The chances of life and environment spontaneously organising into self-regulating states may be much higher than you would expect. If fact, given sufficient biodiversity, it may be extremely likely . But there is a limit to this stability. Push the system too far and it may go beyond a tipping point and rapidly collapse to a new and potentially very different state.

This isn’t a purely theoretical exercise, as we think we may able to test the theory in a number of different ways. At the smallest scale that would involve experiments with diverse bacterial colonies. On a much larger scale it would involve searching for other biospheres around other stars which we could use to estimate the total number of biospheres in the universe – and so not only how likely it is for life to emerge, but also to persist.

The relevance of our findings to current concerns over climate change has not escaped us. Whatever humans do life will carry on in one way or another. But if we continue to emit greenhouse gasses and so change the atmosphere, then we risk producing dangerous and potentially runaway climate change. This could eventually stop human civilisation affecting the atmosphere, if only because there will not be any human civilisation left.

Gaian self-regulation may be very effective. But there is no evidence that it prefers one form of life over another. Countless species have emerged and then disappeared from the Earth over the past 3.7 billion years. We have no reason to think that Homo sapiens are any different in that respect.

This article was updated on July 10 to add the reference to Richard Betts.

- Gaia theory

- Complex systems

Case Management Specialist

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

The Gaia Hypothesis: Fact, Theory, and Wishful Thinking

- Published: March 2002

- Volume 52 , pages 391–408, ( 2002 )

Cite this article

- James W. Kirchner 1

5149 Accesses

72 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Organisms can greatly affect their environments, and the feedback coupling between organisms and their environments can shape the evolution of both. Beyond these generally accepted facts, the Gaia hypothesis advances three central propositions: (1) that biologically mediated feedbacks contribute to environmental homeostasis, (2) that they make the environment more suitable for life, and (3) that such feedbacks should arise by Darwinian natural selection. These three propositions do not fare well under close scrutiny. (1) Biologically mediated feedbacks are not intrinsically homeostatic. Many of the biological mechanisms that affect global climate are destabilizing, and it is likely that the net effect of biological feedbacks will be to amplify, not dampen, global warming. (2) Nor do biologically mediated feedbacks necessarily enhance the environment, although it will often appear as if this were the case, simply because natural selection will favor organisms that do well in their environments – which means doing wellunder the conditions that they and their co-occurring species have created. (3) Finally, Gaian feedbacks can evolve by natural selection, but so can anti-Gaian feedbacks. Daisyworld models evolve Gaian feedback because they assume that any trait that improves the environment will also give a reproductive advantage to its carriers (over other organisms that share the same environment). In the real world, by contrast, natural selection favors any trait that gives its carriers a reproductive advantage over its non-carriers, whether it improves or degrades the environment (and thereby benefits or hinders its carriers and non-carriers alike). Thus Gaian and anti-Gaian feedbacks are both likely to evolve.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Origin’s Chapter III: The Two Faces of Natural Selection

The development of darwin’s theory: from natural theology to natural selection.

A universal ethology challenge to the free energy principle: species of inference and good regulators

Charlson, R. J., Lovelock, J. E., Andreae, M. O., and Warren, S. G.: 1987, ‘Oceanic Phytoplankton, Atmospheric Sulphur, Cloud Albedo and Climate’, Nature 326 , 655–661.

Google Scholar

Ciais, P., Tans, P. P., Trolier, M., White, J. W. C., and Francey, R. J.: 1995, ‘A Large Northern Hemisphere Terrestrial CO 2 Sink Indicated by the 13C/12C ratio of atmospheric CO 2 ’, Science 269 , 1098–1102.

Falkowski, P., Scholes, R. J., Boyle, E., Canadell, J., Canfield, D., Elser, J., Gruber, N., Hibbard, K., Hogberg, P., Linder, S., Mackenzie, F. T., Moore, B., Pedersen, T., Rosenthal, Y., Seitzinger, S., Smetacek, V., and Steffen, W.: 2000, ‘The Global Carbon Cycle: A Test of Our Knowledge of Earth as a System’, Science 290 , 291–296.

Gillon, J.: 2000, ‘Feedback on Gaia’, Nature 406 , 685–686.

Hamilton, W. D.: 1995, ‘Ecology in the Large: Gaia and Ghengis Khan’, J. Appl. Ecol. 32 , 451–453.

Harvey, H. W.: 1957, The Chemistry and Fertility of Sea Waters , Cambridge University Press, New York.

Henderson, L. J.: 1913, The Fitness of the Environment , MacMillan, New York.

Holland, H. D.: 1964, ‘The Chemical Evolution of the Terrestrial and Cytherian Atmospheres’, in Brancazio, P. J. and Cameron, A. G. W. (eds.), The Origin and Evolution of Atmospheres and Oceans , Wiley, New York.

Holland, H. D.: 1984, The Chemical Evolution of the Atmosphere and Oceans , Princeton University Press, Princeton, N. J.

Hutchinson, G. E.: 1954, ‘The Biogeochemistry of the Terrestrial Atmosphere’, in Kuiper, G. P. (ed.), The Earth as a Planet , University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 371–433.

Huxley, T. H.: 1877, Physiography , MacMillan and Co., London.

Keeling, C. D., Chin, J. F. S., and Whorf, T. P.: 1996a, ‘Increased Activity of Northern Vegetation Inferred from Atmospheric CO2 Measurements’, Nature 382 , 146–149.

Keeling, R. F., Piper, S. C., and Heimann, M.: 1996b, ‘Global and Hemispheric CO2 Sinks Deduced from Changes in Atmospheric O2 Concentration’, Nature 381 , 218–221.

Kerr, R. A.: 1988, ‘No Longer Willful, Gaia Becomes Respectable’, Science 240 , 393–395.

Kirchner, J. W.: 1989, ‘The Gaia Hypothesis: Can It Be Tested?’, Rev. Geophys. 27 , 223–235.

Kirchner, J. W.: 1990, ‘Gaia Metaphor Unfalsifiable’, Nature 345 , 470.

Kirchner, J. W.: 1991, ‘The Gaia Hypotheses: Are They Testable? Are They Useful?’, in Schneider, S. H. and Boston, P. J. (ed.), Scientists on Gaia , MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp. 38–46.

Kirchner, J.W. and Roy, B. A.: 1999, ‘The Evolutionary Advantages of Dying Young: Epidemiological Implications of Longevity in Metapopulations’, Amer. Naturalist 154 , 140–159.

Kleidon, A.: 2002, ‘Testing the Effect of Life on Earth's Functioning: How Gaian Is the Earth System?’, Clim. Change , this issue.

Lashof, D. A.: 1989, ‘The Dynamic Greenhouse: Feedback Processes That May Influence Future Concentrations of Atmospheric Trace Gases in Climatic Change’, Clim. Change 14 , 213–242.

Lashof, D. A., DeAngelo, B. J., Saleska, S. R., and Harte, J.: 1997, ‘Terrestrial Ecosystem Feedbacks to Global Climate Change’, Ann. Rev. Energy Environ. 22 , 75–118.

Legrand, M., Feniet-Saigne, C., Saltzman, E. S., Germain, C., Barkov, N. I., and Petrov, V. N.: 1991, ‘Ice-Core Record of Oceanic Emissions of Dimethylsulphide during the Last Climate Cycle’, Nature 350 , 144–146.

Legrand, M. R., Delmas, R. J., and Charlson, R. J.: 1988, ‘Climate Forcing Implications from Vostok Ice-Core Sulphate Data’, Nature 334 , 418–420.

Lenton, T. M.: 1998, ‘Gaia and Natural Selection’, Nature 394 , 439–447.

Lovelock, J. E.: 1986, ‘Geophysiology: A New Look at Earth Science’, in Dickinson, R. E. (ed.), The Geophysiology of Amazonia: Vegetation and Climate Interactions , Wiley, New York, pp. 11–23.

Lovelock, J. E. and Kump, L. R.: 1994, ‘Failure of Climate Regulation in a Geophysiological Model’, Nature 369 , 732–734.

Lovelock, J. E. and Margulis, L.: 1974a, ‘Homeostatic Tendencies of the Earth's Atmosphere’, Origins Life 5 , 93–103.

Lovelock, J. E. and Margulis, L.: 1974b, ‘Atmospheric Homeostasis by and for the Biosphere: The Gaia Hypothesis’, Tellus 26 , 2–9.

Myneni, R. B., Keeling, C. D., Tucker, C. J., Asrar, G., and Nemani, R. R.: 1997, ‘Increased Plant Growth in the Northern High Latitudes from 1981 to 1991’, Nature 386 , 698–702.

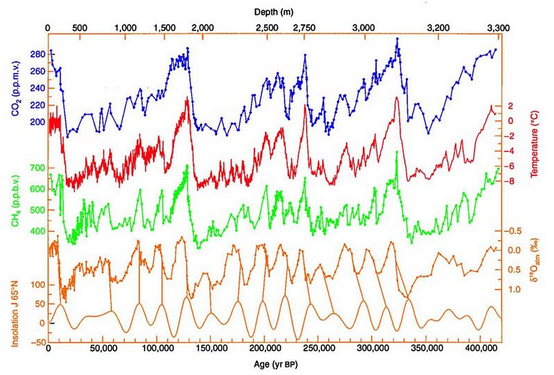

Petit, J. R., Jouzel, J., Raynaud, D., Barkov, N. I., Barnola, J.-M., Basile, I., Bender, M., Chappellaz, J., Davisk, M., Delaygue, G., Delmotte, M., Kotlyakov, V. M., Legrand, M., Lipenkov, V. Y., Lorius, C., Pepin, L., Ritz, C., Saltzmank, E., and Stievenard, M.: 1999, ‘Climate and Atmospheric History of the Past 420,000 Years from the Vostok Ice Core, Antarctica’, Nature 399 , 429–436.

Redfield, A. C.: 1958, ‘The Biological Control of Chemical Factors in the Environment’, Amer. J. Sci. 46 , 205–221.

Saleska, S. R., Harte, J., and Torn, M. S.: 1999, ‘The Effect of Experimental Ecosystem Warming on CO 2 Fluxes in a Montane Meadow’, Global Change Biol. 5 , 125–141.

Schneider, S. H.: 2001, ‘A Goddess of Earth or the Imagination of a Man?’, Science 291 , 1906–1907.

Schneider, S. H. and Londer, R.: 1984, The Coevolution of Climate and Life , San Francisco, Sierra Club Books.

Schwartzmann, D. W. and Volk, T.: 1989, ‘Biotic Enhancement of Weathering and the Habitability of Earth’, Nature 340 , 457–460.

Sillen, L. G.: 1966, ‘Regulation of O 2 , N 2 , and CO 2 in the Atmosphere; Thoughts of a Laboratory Chemist’, Tellus 18 , 198–206.

Spencer, H.: 1844, ‘Remarks upon the Theory of Reciprocal Dependence in the Animal and Vegetable Creations, as Regards its Bearing upon Paleontology’, London Edinburgh Dublin Phil. Magazine and J. Science 24 , 90–94.

Tans, P. P., Fung, I. Y., and Takahashi, T.: 1990, ‘Observational Constraints on the Global Atmospheric CO 2 Budget’, Science 247 , 1431–1438.

Volk, T.: 1998, Gaia's Body: Toward a Physiology of Earth , Copernicus, New York.

Watson, A. J., Bakker, D. C. E., Ridgwell, A. J., Boyd, P. W., and Law, C. S.: 2000, ‘Effect of Iron Supply on Southern Ocean CO2 Uptake and Implications for Glacial Atmospheric CO 2 ’, Nature 407 , 730–733.

Watson, A. J. and Liss, P. S.: 1998, ‘Marine Biological Controls on Climate via the Carbon and Sulphur Geochemical Cycles’, Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London, Series B 353 , 41–51.

Watson, A. J. and Lovelock, J. E.: 1983, ‘Biological Homeostasis of the Global Environment: The Parable of Daisyworld’, Tellus, Series B: Chem. Phys. Meterol. 35 , 284–289.

Woodward, F. I., Lomas, M. R., and Betts, R. A.: 1998, ‘Vegetation-Climate Feedbacks in a Greenhouse World’, Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London, Series B 353 , 29–39.

Woodwell, G. M., Mackenzie, F. T., Houghton, R. A., Apps, M., Gorham, E., and Davidson, E.: 1998, ‘Biotic Feedbacks in the Warming of the Earth’, Clim. Change 40 , 495–518. (Received 16 May 2001; in revised form 9 July 2001)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Earth and Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA, 94720-4767, U.S.A.

James W. Kirchner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Kirchner, J.W. The Gaia Hypothesis: Fact, Theory, and Wishful Thinking. Climatic Change 52 , 391–408 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014237331082

Download citation

Issue Date : March 2002

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014237331082

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Natural Selection

- Global Warming

- Global Climate

- Biological Mechanism

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Garden Planning

- Garden Tools

- Gardening Techniques

- Ornamentals

- Pest Control

- Raising Cattle

- Raising Pigs

- Raising Rabbits

- Raising Sheep And Goats

- Raising Chickens

- Raising Ducks And Geese

- Raising Turkeys

- Power Equipment

- Self Reliance

- Sustainable Farming

- Food Policy

- Food Preservation

- Homemade Bread

- Homemade Cheese

- Seasonal Recipes

- Garden And Yard

- Herbal Remedies

- Energy Policy

- Other Renewables

- Solar Power

- Wood Heaters

- Green Cleaning

- Green Home Design

- Natural Building

- Environmental Policy

- Sustainable Communities

- Biofuel & Biodiesel

- Fuel Efficiency

- Green Vehicles

- Energy Efficiency

- Home Organization

- Natural Home

- Free Guides

- Give A Gift

- Gardening Tools

- Raising Ducks and Geese

- Garden and Yard

- Other Home Renewables

- Fuel Efficiency News, Blog, & Articles

- Green Vehicles News, Blog, & Articles

- Energy Efficiency News, Blog, & Articles

- Home Organization News, Blog, & Articles

- Give a Gift

- Land For Sale

- Diversity Commitment

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

The Gaia Hypothesis: Is the Earth Alive?

More than one astronaut looking back at our planet has been awed into concluding that this blue and green globe is, in fact, a living being. Of course, many native peoples the world over have always believed (and functioned on the premise) that the earth is alive.

And now contemporary scientists are talking more and more about the Gaia hypothesis: the proposition that, in some ways, the planet does behave like a living system. (Gaia pronounced “Guy-uh” — was the Greek goddess of the earth.)

“What’s that?” you say. “Scientists are saying the earth is alive?” Well, the honest answer to that is “No, but . . .” And the “but” becomes quite fascinating.

British scientist James Lovelock, the person most responsible for the Gaia hypothesis, was working for NASA when he first reached his living system insight questioning is the earth alive? Surprisingly, though, at the time he was creating tests to detect life on Mars!

Lovelock had taken the approach that, rather than have satellites take minute soil tests on the red planet (using what he described as “glorified flea detectors”), scientists should look at Mars’ atmosphere to see if it has any concentrations of gases that could exist only if they were maintained by living organisms. To test that idea, Lovelock looked at the atmosphere of our own planet. Sure enough, earth’s air contains large quantities of highly reactive gases — such as oxygen and methane — that naturally break down into other compounds. “If chemical thermodynamics alone mattered,” he wrote, “almost all the oxygen and most of the nitrogen in the atmosphere ought to have ended up in the sea combined as nitrate ion.”

This simple discovery later developed into one of Lovelock’s original arguments for Gaia: Something is maintaining numerous reactive gases in our atmosphere in an equilibrium steady state. (Mars, by the way, flunked the “active atmosphere” test.)

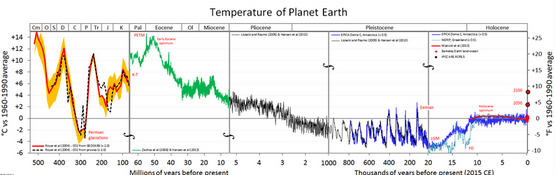

The second, and even more compelling, argument was that over the millenia the earth has somehow regulated its own temperature. When life began on our planet four billion years ago, the sun was 30% cooler than it is today. Yet, from then until now, the temperature of the earth’s surface has remained within the critical life-supporting range of 15 degrees to 30 degrees Celsiu. The level of CO, has dropped a hundred fold in those four billion years, reducing the “greenhouse” heat-holding effect of the atmosphere even while the sun was radiating more heat. The result? The earth has kept itself at a constant temperature . . . just as our own bodies do!

Temperature and a reactive atmosphere are just two of the factors kept in balance by the earth. One must also notice that if — as Lovelock states — “humidity or salinity or acidity or any one of a number of other variables had strayed outside a narrow range of values for any length of time, life would have been annihilated.”

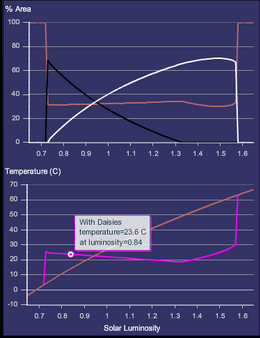

The interactive mechanisms that accomplish this self — regulation are too complex for current science to quantify, so Lovelock often uses a simplified model of an imaginary “Daisy World” to suggest how the system might work. Suppose there was a planet that supported only two plant species, white daisies and black daisies. Since the white ones reflect more heat than black ones, they would fare better when the planet was unusually hot. The reverse would also be true: Black daisies, being better heat absorbers, could survive better during cool periods.

But what would happen if Daisy World was cool for an extended time? Black daisies would take over more and more of the land surface, increasing the absorption capacity of the planet and thereby warming it up. In time, the temperature would rise to the best range for white daisies. Those would spread, and the black ones would largely die back. But that event would increase the heat reflectiveness of the planet, thus eventually cooling its surface.

By such means, the black and white daisies would balance each other and keep the planet’s temperature from ever getting too hot or too cold to support plant life. On a much more complex level, the organisms on our own planet must work together to stabilize the earth.

In sum (again quoting Lovelock), “The Gaia hypothesis sees the earth as a self-regulating system able to maintain the climate, the atmosphere, the soil, and the ocean composition at a fixed state that’s favorable for life. It’s often taken that the capacity for self regulation in the face of perturbation, change, disasters, and so on is a very strong characteristic of living things and, in that sense, the earth is a living thing.”

But Really, is the Earth Alive?

Lovelock is saying that the evolution of life and the evolution of the planet have not been separate phenomena but one single, tightly coupled process. Life does not simply adapt to its environment but, through various feedback loops, coevolves with it. This unifying, whole systems view is beginning to gain ground with scientists. And the fascinating search for Gaia’s mechanisms is already leading to new areas of exploration. Biologist Lynn Margulis, who worked closely with Lovelock on the original hypothesis, now studies the roles that hardy microorganisms may play in regulating the atmosphere. She’s found 200 or so mostly dormant microorganisms in tiny culture samples, each ready under the right conditions — to perform its function and give off its particular gaseous emission, depending on surrounding conditions. Atmospheric scientist Pat Zimmerman examined the intestinal bacteria of termites as a source of atmospheric methane and learned that since there are about 1,500 pounds of termites per human being on earth, and since the wood nibblers go through the equivalent of one-third of the new plant carbon created every year, they may produce half of the methane in the atmosphere!

But Lovelock’s words have at times suggested that the planet’s totality of life is deliberately working to better its condition and increase itself. Adding such an aspect of purposefulness (even consciousness) to Gaia grates on most otherwise sympathetic scientists. Any hints that the whole system may indeed be alive are taboo to them — that’s talking religion. And as Stanford Research Institute senior policy analyst Don Michael puts it, “Science and spirit are different realms. They are not in conflict, but there’s no interface between the two.” Lovelock himself now seems to back away from such implications: “There’s no foresight or planning involved on the part of life in regulating the planet. It’s just a kind of automatic process.”

That hasn’t stopped many non-scientists from drawing their own conclusions about the implications of the Gaia hypothesis. Like several other environmentalists, Nancy Todd, co-founder of the New Alchemy Institute, sees Gaia as a means of helping humans be better planetary stewards. “Gaia,” she states, “is the only metaphor scientific and mythologic enough to see us through our present crisis and lead to a resacralization of the world.”

Indigenous peoples who have always felt themselves in communication with a living planet feel that interest in Gaia is a sign that technological cultures are beginning to agree with them. Prem Das, a shaman — healer in Tepic, Mexico, tells outsiders that of course the planet is alive: “The Earth is speaking all the time. But it doesn’t speak English. It speaks Earthese. We just need to learn how to listen.”

Psychologist Jim Swan-producer of a national symposium called “Is the Earth a Living Organism?” — feels the Gaia hypothesis may herald a paradigmatic shift that would affect almost all areas of thought and be greatly beneficial to society. He says, “You can’t prove earth is alive scientifically, because living is a property beyond the very limited structure of current science. But you can know it for yourself through direct experience — through vision quests in sacred places, for example. And such knowledge has incredible practical utility. Science based on it would help bind us to each other, not blow each other up. Experience of the living earth can also have great benefits for mental and physical health — especially in our society, which rejects feeling, intuitive modes of being. The experience can also change your life priorities. Almost all our country’s great environmentalists — including Burroughs, Thoreau, Carson, and Muir — have felt a oneness with the planet and had that as a motivation for their actions.”

Earthly Thoughts in the Meantime

While Gaian scientists stay clear of such thoughts, the hypothesis is beginning to motivate their actions, as well. Dr. Stephen Schneider of the National Center for Atmospheric Research points out that although Gaia’s regulatory mechanisms may help assure the long-term existence of life on the planet, they may not assure the short-term survival of our own individual species — a species that may be making the planet too hot for its own good. “And I’m a chauvinist for human beings,” he confesses.

Even Lovelock, for all his British aplomb, agrees: “The clearing of the tropical forests and the addition of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere by fossil fuel burning act both in the same way to stress a system which is already near the limit of its capacity to regulate. And the effect of this perturbation might cause us to jump to a new stable state in the very near future. I imagine if the system does flip to a different stable state, there will be a sudden and enormous change in speciation, just as there was when the dinosaurs vanished. There will be a new biota that will be fit for the new environment. But I doubt it will be very comfortable for us.”

So, if widely understood, the Gaia hypothesis could help us avoid such a catastrophe. Whether the idea is adopted as a new spiritual credo or an automatic mechanism, it may be a notion whose time has come . . . not a moment too soon.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Lovelock’s book Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth is available for $6.95 postpaid from Oxford University Press, NJ.

- Published on May 1, 1986

Subscribe Today to Mother Earth News!

50 years of money-saving tips.

- Spend less cash on groceries by growing and preserving your own food

- Shave off your energy bill and reduce your reliance on the grid with DIY hacks anyone can achieve

- Explore small-scale animal husbandry for provisions, profit, and land management

Canadian Subscribers • International Subscribers

Canadian subscriptions: 1 year (includes postage & GST)

Membership Subtotal

Total savings

Shipping and taxes calculated at checkout.

Clear cart or Continue Shopping →

- Scholarly Community Encyclopedia

- Log in/Sign up

Video Upload Options

- MDPI and ACS Style

- Chicago Style

The Gaia hypothesis (/ˈɡaɪ.ə/), also known as the Gaia theory, Gaia paradigm, or the Gaia principle, proposes that living organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings on Earth to form a synergistic and self-regulating, complex system that helps to maintain and perpetuate the conditions for life on the planet. The hypothesis was formulated by the chemist James Lovelock and co-developed by the microbiologist Lynn Margulis in the 1970s. Lovelock named the idea after Gaia, the primordial goddess who personified the Earth in Greek mythology. The suggestion that the theory should be called "the Gaia hypothesis" came from Lovelock's neighbour, William Golding. In 2006, the Geological Society of London awarded Lovelock the Wollaston Medal in part for his work on the Gaia hypothesis. Topics related to the hypothesis include how the biosphere and the evolution of organisms affect the stability of global temperature, salinity of seawater, atmospheric oxygen levels, the maintenance of a hydrosphere of liquid water and other environmental variables that affect the habitability of Earth. The Gaia hypothesis was initially criticized for being teleological and against the principles of natural selection, but later refinements aligned the Gaia hypothesis with ideas from fields such as Earth system science, biogeochemistry and systems ecology. Even so, the Gaia hypothesis continues to attract criticism, and today many scientists consider it to be only weakly supported by, or at odds with, the available evidence.

1. Overview

Gaian hypotheses suggest that organisms co-evolve with their environment: that is, they "influence their abiotic environment, and that environment in turn influences the biota by Darwinian process". Lovelock (1995) gave evidence of this in his second book, Ages of Gaia , showing the evolution from the world of the early thermo-acido-philic and methanogenic bacteria towards the oxygen-enriched atmosphere today that supports more complex life.

A reduced version of the hypothesis has been called "influential Gaia" [ 1 ] in "Directed Evolution of the Biosphere: Biogeochemical Selection or Gaia?" by Andrei G. Lapenis, which states the biota influence certain aspects of the abiotic world, e.g. temperature and atmosphere. This is not the work of an individual but a collective of Russian scientific research that was combined into this peer reviewed publication. It states the coevolution of life and the environment through "micro-forces" [ 1 ] and biogeochemical processes. An example is how the activity of photosynthetic bacteria during Precambrian times completely modified the Earth atmosphere to turn it aerobic, and thus supports the evolution of life (in particular eukaryotic life).

Since barriers existed throughout the twentieth century between Russia and the rest of the world, it is only relatively recently that the early Russian scientists who introduced concepts overlapping the Gaia paradigm have become better known to the Western scientific community. [ 1 ] These scientists include Piotr Alekseevich Kropotkin (1842–1921) (although he spent much of his professional life outside Russia), Rafail Vasil’evich Rizpolozhensky (1862 – c. 1922), Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky (1863–1945), and Vladimir Alexandrovich Kostitzin (1886–1963).

Biologists and Earth scientists usually view the factors that stabilize the characteristics of a period as an undirected emergent property or entelechy of the system; as each individual species pursues its own self-interest, for example, their combined actions may have counterbalancing effects on environmental change. Opponents of this view sometimes reference examples of events that resulted in dramatic change rather than stable equilibrium, such as the conversion of the Earth's atmosphere from a reducing environment to an oxygen-rich one at the end of the Archaean and the beginning of the Proterozoic periods.

Less accepted versions of the hypothesis claim that changes in the biosphere are brought about through the coordination of living organisms and maintain those conditions through homeostasis. In some versions of Gaia philosophy, all lifeforms are considered part of one single living planetary being called Gaia . In this view, the atmosphere, the seas and the terrestrial crust would be results of interventions carried out by Gaia through the coevolving diversity of living organisms.

The Gaia paradigm was an influence on the deep ecology movement. [ 2 ]

The Gaia hypothesis posits that the Earth is a self-regulating complex system involving the biosphere, the atmosphere, the hydrospheres and the pedosphere, tightly coupled as an evolving system. The hypothesis contends that this system as a whole, called Gaia, seeks a physical and chemical environment optimal for contemporary life. [ 3 ]

Gaia evolves through a cybernetic feedback system operated unconsciously by the biota, leading to broad stabilization of the conditions of habitability in a full homeostasis. Many processes in the Earth's surface, essential for the conditions of life, depend on the interaction of living forms, especially microorganisms, with inorganic elements. These processes establish a global control system that regulates Earth's surface temperature, atmosphere composition and ocean salinity, powered by the global thermodynamic disequilibrium state of the Earth system. [ 4 ]

The existence of a planetary homeostasis influenced by living forms had been observed previously in the field of biogeochemistry, and it is being investigated also in other fields like Earth system science. The originality of the Gaia hypothesis relies on the assessment that such homeostatic balance is actively pursued with the goal of keeping the optimal conditions for life, even when terrestrial or external events menace them. [ 5 ]

2.1. Regulation of Global Surface Temperature

Since life started on Earth, the energy provided by the Sun has increased by 25% to 30%; [ 6 ] however, the surface temperature of the planet has remained within the levels of habitability, reaching quite regular low and high margins. Lovelock has also hypothesised that methanogens produced elevated levels of methane in the early atmosphere, giving a view similar to that found in petrochemical smog, similar in some respects to the atmosphere on Titan. [ 7 ] This, he suggests tended to screen out ultraviolet until the formation of the ozone screen, maintaining a degree of homeostasis. However, the Snowball Earth [ 8 ] research has suggested that "oxygen shocks" and reduced methane levels led, during the Huronian, Sturtian and Marinoan/Varanger Ice Ages, to a world that very nearly became a solid "snowball". These epochs are evidence against the ability of the pre Phanerozoic biosphere to fully self-regulate.

Processing of the greenhouse gas CO 2 , explained below, plays a critical role in the maintenance of the Earth temperature within the limits of habitability.

The CLAW hypothesis, inspired by the Gaia hypothesis, proposes a feedback loop that operates between ocean ecosystems and the Earth's climate. [ 9 ] The hypothesis specifically proposes that particular phytoplankton that produce dimethyl sulfide are responsive to variations in climate forcing, and that these responses lead to a negative feedback loop that acts to stabilise the temperature of the Earth's atmosphere.

Currently the increase in human population and the environmental impact of their activities, such as the multiplication of greenhouse gases may cause negative feedbacks in the environment to become positive feedback. Lovelock has stated that this could bring an extremely accelerated global warming, [ 10 ] but he has since stated the effects will likely occur more slowly. [ 11 ]

Daisyworld simulations

In response to the criticism that the Gaia hypothesis seemingly required unrealistic group selection and cooperation between organisms, James Lovelock and Andrew Watson developed a mathematical model, Daisyworld, in which ecological competition underpinned planetary temperature regulation. [ 12 ]

Daisyworld examines the energy budget of a planet populated by two different types of plants, black daisies and white daisies, which are assumed to occupy a significant portion of the surface. The colour of the daisies influences the albedo of the planet such that black daisies absorb more light and warm the planet, while white daisies reflect more light and cool the planet. The black daisies are assumed to grow and reproduce best at a lower temperature, while the white daisies are assumed to thrive best at a higher temperature. As the temperature rises closer to the value the white daisies like, the white daisies outreproduce the black daisies, leading to a larger percentage of white surface, and more sunlight is reflected, reducing the heat input and eventually cooling the planet. Conversely, as the temperature falls, the black daisies outreproduce the white daisies, absorbing more sunlight and warming the planet. The temperature will thus converge to the value at which the reproductive rates of the plants are equal.

Lovelock and Watson showed that, over a limited range of conditions, this negative feedback due to competition can stabilize the planet's temperature at a value which supports life, if the energy output of the Sun changes, while a planet without life would show wide temperature changes. The percentage of white and black daisies will continually change to keep the temperature at the value at which the plants' reproductive rates are equal, allowing both life forms to thrive.

It has been suggested that the results were predictable because Lovelock and Watson selected examples that produced the responses they desired. [ 13 ]

2.2. Regulation of Oceanic Salinity

Ocean salinity has been constant at about 3.5% for a very long time. [ 14 ] Salinity stability in oceanic environments is important as most cells require a rather constant salinity and do not generally tolerate values above 5%. The constant ocean salinity was a long-standing mystery, because no process counterbalancing the salt influx from rivers was known. Recently it was suggested [ 15 ] that salinity may also be strongly influenced by seawater circulation through hot basaltic rocks, and emerging as hot water vents on mid-ocean ridges. However, the composition of seawater is far from equilibrium, and it is difficult to explain this fact without the influence of organic processes. One suggested explanation lies in the formation of salt plains throughout Earth's history. It is hypothesized that these are created by bacterial colonies that fix ions and heavy metals during their life processes. [ 14 ]

In the biogeochemical processes of Earth, sources and sinks are the movement of elements. The composition of salt ions within our oceans and seas is: sodium (Na + ), chlorine (Cl − ), sulfate (SO 4 2− ), magnesium (Mg 2+ ), calcium (Ca 2+ ) and potassium (K + ). The elements that comprise salinity do not readily change and are a conservative property of seawater. [ 14 ] There are many mechanisms that change salinity from a particulate form to a dissolved form and back. Considering the metallic composition of iron sources across a multifaceted grid of thermomagnetic design, not only would the movement of elements hypothetically help restructure the movement of ions, electrons, and the like, but would also potentially and inexplicably assist in balancing the magnetic bodies of the Earth's geomagnetic field. The known sources of sodium i.e. salts are when weathering, erosion, and dissolution of rocks are transported into rivers and deposited into the oceans.

The Mediterranean Sea as being Gaia's kidney is found (here) by Kenneth J. Hsue, a correspondence author in 2001. Hsue suggests the "desiccation" of the Mediterranean is evidence of a functioning Gaia "kidney". In this and earlier suggested cases, it is plate movements and physics, not biology, which performs the regulation. Earlier "kidney functions" were performed during the "deposition of the Cretaceous (South Atlantic), Jurassic (Gulf of Mexico), Permo-Triassic (Europe), Devonian ( Canada ), and Cambrian/Precambrian (Gondwana) saline giants." [ 16 ]

2.3. Regulation of Oxygen in the Atmosphere

The Gaia theorem states that the Earth's atmospheric composition is kept at a dynamically steady state by the presence of life. [ 17 ] The atmospheric composition provides the conditions that contemporary life has adapted to. All the atmospheric gases other than noble gases present in the atmosphere are either made by organisms or processed by them.

The stability of the atmosphere in Earth is not a consequence of chemical equilibrium. Oxygen is a reactive compound, and should eventually combine with gases and minerals of the Earth's atmosphere and crust. Oxygen only began to persist in the atmosphere in small quantities about 50 million years before the start of the Great Oxygenation Event. [ 18 ] Since the start of the Cambrian period, atmospheric oxygen concentrations have fluctuated between 15% and 35% of atmospheric volume. Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag Carbon precipitation, solution and fixation are influenced by the bacteria and plant roots in soils, where they improve gaseous circulation, or in coral reefs, where calcium carbonate is deposited as a solid on the sea floor. Calcium carbonate is used by living organisms to manufacture carbonaceous tests and shells. Once dead, the living organisms' shells fall. Some arrive at the bottom of the oceans where plate tectonics and heat and/or pressure eventually convert them to deposits of chalk and limestone. Much of the falling dead shells, however, re-dissolve into the ocean below the carbon compensation depth.

One of these organisms is Emiliania huxleyi , an abundant coccolithophore algae which may have a role in the formation of clouds. [ 19 ] CO 2 excess is compensated by an increase of coccolithophorid life, increasing the amount of CO 2 locked in the ocean floor. Coccolithophorids, if the CLAW Hypothesis turns out to be supported (see "Regulation of Global Surface Temperature" above), could help increase the cloud cover, hence control the surface temperature, help cool the whole planet and favor precipitation necessary for terrestrial plants. Lately the atmospheric CO 2 concentration has increased and there is some evidence that concentrations of ocean algal blooms are also increasing. [ 20 ]

Lichen and other organisms accelerate the weathering of rocks in the surface, while the decomposition of rocks also happens faster in the soil, thanks to the activity of roots, fungi, bacteria and subterranean animals. The flow of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to the soil is therefore regulated with the help of living beings. When CO 2 levels rise in the atmosphere the temperature increases and plants grow. This growth brings higher consumption of CO 2 by the plants, who process it into the soil, removing it from the atmosphere.

3.1. Precedents

The idea of the Earth as an integrated whole, a living being, has a long tradition. The mythical Gaia was the primal Greek goddess personifying the Earth, the Greek version of "Mother Nature" (from Ge = Earth, and Aia = PIE grandmother), or the Earth Mother. James Lovelock gave this name to his hypothesis after a suggestion from the novelist William Golding, who was living in the same village as Lovelock at the time (Bowerchalke, Wiltshire, UK). Golding's advice was based on Gea, an alternative spelling for the name of the Greek goddess, which is used as prefix in geology, geophysics and geochemistry. [ 21 ] Golding later made reference to Gaia in his Nobel prize acceptance speech.

In the eighteenth century, as geology consolidated as a modern science, James Hutton maintained that geological and biological processes are interlinked. [ 22 ] Later, the naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt recognized the coevolution of living organisms, climate, and Earth's crust. [ 22 ] In the twentieth century, Vladimir Vernadsky formulated a theory of Earth's development that is now one of the foundations of ecology. Vernadsky was a Ukrainian geochemist and was one of the first scientists to recognize that the oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere result from biological processes. During the 1920s he published works arguing that living organisms could reshape the planet as surely as any physical force. Vernadsky was a pioneer of the scientific bases for the environmental sciences. [ 23 ] His visionary pronouncements were not widely accepted in the West, and some decades later the Gaia hypothesis received the same type of initial resistance from the scientific community.

Also in the turn to the 20th century Aldo Leopold, pioneer in the development of modern environmental ethics and in the movement for wilderness conservation, suggested a living Earth in his biocentric or holistic ethics regarding land.

Another influence for the Gaia hypothesis and the environmental movement in general came as a side effect of the Space Race between the Soviet Union and the United States of America. During the 1960s, the first humans in space could see how the Earth looked as a whole. The photograph Earthrise taken by astronaut William Anders in 1968 during the Apollo 8 mission became, through the Overview Effect an early symbol for the global ecology movement. [ 24 ]

3.2. Formulation of the Hypothesis

Lovelock started defining the idea of a self-regulating Earth controlled by the community of living organisms in September 1965, while working at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California on methods of detecting life on Mars. [ 25 ] [ 26 ] The first paper to mention it was Planetary Atmospheres: Compositional and other Changes Associated with the Presence of Life , co-authored with C.E. Giffin. [ 27 ] A main concept was that life could be detected in a planetary scale by the chemical composition of the atmosphere. According to the data gathered by the Pic du Midi observatory, planets like Mars or Venus had atmospheres in chemical equilibrium. This difference with the Earth atmosphere was considered to be a proof that there was no life in these planets.

Lovelock formulated the Gaia Hypothesis in journal articles in 1972 [ 28 ] and 1974, [ 29 ] followed by a popularizing 1979 book Gaia: A new look at life on Earth . An article in the New Scientist of February 6, 1975, [ 30 ] and a popular book length version of the hypothesis, published in 1979 as The Quest for Gaia , began to attract scientific and critical attention.

Lovelock called it first the Earth feedback hypothesis, [ 31 ] and it was a way to explain the fact that combinations of chemicals including oxygen and methane persist in stable concentrations in the atmosphere of the Earth. Lovelock suggested detecting such combinations in other planets' atmospheres as a relatively reliable and cheap way to detect life.

Later, other relationships such as sea creatures producing sulfur and iodine in approximately the same quantities as required by land creatures emerged and helped bolster the hypothesis. [ 32 ]

In 1971 microbiologist Dr. Lynn Margulis joined Lovelock in the effort of fleshing out the initial hypothesis into scientifically proven concepts, contributing her knowledge about how microbes affect the atmosphere and the different layers in the surface of the planet. [ 33 ] The American biologist had also awakened criticism from the scientific community with her advocacy of the theory on the origin of eukaryotic organelles and her contributions to the endosymbiotic theory, nowadays accepted. Margulis dedicated the last of eight chapters in her book, The Symbiotic Planet , to Gaia. However, she objected to the widespread personification of Gaia and stressed that Gaia is "not an organism", but "an emergent property of interaction among organisms". She defined Gaia as "the series of interacting ecosystems that compose a single huge ecosystem at the Earth's surface. Period". The book's most memorable "slogan" was actually quipped by a student of Margulis'.

James Lovelock called his first proposal the Gaia hypothesis but has also used the term Gaia theory . Lovelock states that the initial formulation was based on observation, but still lacked a scientific explanation. The Gaia hypothesis has since been supported by a number of scientific experiments [ 34 ] and provided a number of useful predictions. [ 35 ]

3.3. First Gaia Conference

In 1985, the first public symposium on the Gaia hypothesis, Is The Earth A Living Organism? was held at University of Massachusetts Amherst, August 1–6. [ 36 ] The principal sponsor was the National Audubon Society. Speakers included James Lovelock, George Wald, Mary Catherine Bateson, Lewis Thomas, John Todd, Donald Michael, Christopher Bird, Thomas Berry, David Abram, Michael Cohen, and William Fields. Some 500 people attended. [ 37 ]

3.4. Second Gaia Conference

In 1988, climatologist Stephen Schneider organised a conference of the American Geophysical Union. The first Chapman Conference on Gaia, [ 38 ] was held in San Diego, California on March 7, 1988.

During the "philosophical foundations" session of the conference, David Abram spoke on the influence of metaphor in science, and of the Gaia hypothesis as offering a new and potentially game-changing metaphorics, while James Kirchner criticised the Gaia hypothesis for its imprecision. Kirchner claimed that Lovelock and Margulis had not presented one Gaia hypothesis, but four:

- CoEvolutionary Gaia: that life and the environment had evolved in a coupled way. Kirchner claimed that this was already accepted scientifically and was not new.

- Homeostatic Gaia: that life maintained the stability of the natural environment, and that this stability enabled life to continue to exist.

- Geophysical Gaia: that the Gaia hypothesis generated interest in geophysical cycles and therefore led to interesting new research in terrestrial geophysical dynamics.

- Optimising Gaia: that Gaia shaped the planet in a way that made it an optimal environment for life as a whole. Kirchner claimed that this was not testable and therefore was not scientific.

Of Homeostatic Gaia, Kirchner recognised two alternatives. "Weak Gaia" asserted that life tends to make the environment stable for the flourishing of all life. "Strong Gaia" according to Kirchner, asserted that life tends to make the environment stable, to enable the flourishing of all life. Strong Gaia, Kirchner claimed, was untestable and therefore not scientific. [ 39 ]

Lovelock and other Gaia-supporting scientists, however, did attempt to disprove the claim that the hypothesis is not scientific because it is impossible to test it by controlled experiment. For example, against the charge that Gaia was teleological, Lovelock and Andrew Watson offered the Daisyworld Model (and its modifications, above) as evidence against most of these criticisms. [ 12 ] Lovelock said that the Daisyworld model "demonstrates that self-regulation of the global environment can emerge from competition amongst types of life altering their local environment in different ways". [ 40 ]

Lovelock was careful to present a version of the Gaia hypothesis that had no claim that Gaia intentionally or consciously maintained the complex balance in her environment that life needed to survive. It would appear that the claim that Gaia acts "intentionally" was a statement in his popular initial book and was not meant to be taken literally. This new statement of the Gaia hypothesis was more acceptable to the scientific community. Most accusations of teleologism ceased, following this conference.

3.5. Third Gaia Conference

By the time of the 2nd Chapman Conference on the Gaia Hypothesis, held at Valencia, Spain, on 23 June 2000, [ 41 ] the situation had changed significantly. Rather than a discussion of the Gaian teleological views, or "types" of Gaia hypotheses, the focus was upon the specific mechanisms by which basic short term homeostasis was maintained within a framework of significant evolutionary long term structural change.

The major questions were: [ 42 ]

- "How has the global biogeochemical/climate system called Gaia changed in time? What is its history? Can Gaia maintain stability of the system at one time scale but still undergo vectorial change at longer time scales? How can the geologic record be used to examine these questions?"

- "What is the structure of Gaia? Are the feedbacks sufficiently strong to influence the evolution of climate? Are there parts of the system determined pragmatically by whatever disciplinary study is being undertaken at any given time or are there a set of parts that should be taken as most true for understanding Gaia as containing evolving organisms over time? What are the feedbacks among these different parts of the Gaian system, and what does the near closure of matter mean for the structure of Gaia as a global ecosystem and for the productivity of life?"

- "How do models of Gaian processes and phenomena relate to reality and how do they help address and understand Gaia? How do results from Daisyworld transfer to the real world? What are the main candidates for "daisies"? Does it matter for Gaia theory whether we find daisies or not? How should we be searching for daisies, and should we intensify the search? How can Gaian mechanisms be collaborated with using process models or global models of the climate system that include the biota and allow for chemical cycling?"

In 1997, Tyler Volk argued that a Gaian system is almost inevitably produced as a result of an evolution towards far-from-equilibrium homeostatic states that maximise entropy production, and Kleidon (2004) agreed stating: "...homeostatic behavior can emerge from a state of MEP associated with the planetary albedo"; "...the resulting behavior of a symbiotic Earth at a state of MEP may well lead to near-homeostatic behavior of the Earth system on long time scales, as stated by the Gaia hypothesis". Staley (2002) has similarly proposed "...an alternative form of Gaia theory based on more traditional Darwinian principles... In [this] new approach, environmental regulation is a consequence of population dynamics. The role of selection is to favor organisms that are best adapted to prevailing environmental conditions. However, the environment is not a static backdrop for evolution, but is heavily influenced by the presence of living and vibration-based beings and organisms. The resulting co-evolving dynamical process eventually leads to the convergence of equilibrium and optimal conditions", but would also require progress of truth and understanding in a lens that could be argued was put on hiatus while the species was proliferating the needs of Economic manipulation and environmental degradation while losing sight of the maturing nature of the needs of many. (12:22 10.29.2020)

3.6. Fourth Gaia Conference

A fourth international conference on the Gaia hypothesis, sponsored by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority and others, was held in October 2006 at the Arlington, VA campus of George Mason University. [ 43 ]

Martin Ogle, Chief Naturalist, for NVRPA, and long-time Gaia hypothesis proponent, organized the event. Lynn Margulis, Distinguished University Professor in the Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, and long-time advocate of the Gaia hypothesis, was a keynote speaker. Among many other speakers: Tyler Volk, co-director of the Program in Earth and Environmental Science at New York University; Dr. Donald Aitken, Principal of Donald Aitken Associates; Dr. Thomas Lovejoy, President of the Heinz Center for Science, Economics and the Environment; Robert Correll, Senior Fellow, Atmospheric Policy Program, American Meteorological Society and noted environmental ethicist, J. Baird Callicott.

4. Criticism

After initially receiving little attention from scientists (from 1969 until 1977), thereafter for a period the initial Gaia hypothesis was criticized by a number of scientists, including Ford Doolittle, [ 44 ] Richard Dawkins [ 45 ] and Stephen Jay Gould. [ 38 ] Lovelock has said that because his hypothesis is named after a Greek goddess, and championed by many non-scientists, [ 31 ] the Gaia hypothesis was interpreted as a neo-Pagan religion. Many scientists in particular also criticized the approach taken in his popular book Gaia, a New Look at Life on Earth for being teleological—a belief that things are purposeful and aimed towards a goal. Responding to this critique in 1990, Lovelock stated, "Nowhere in our writings do we express the idea that planetary self-regulation is purposeful, or involves foresight or planning by the biota".

Stephen Jay Gould criticized Gaia as being "a metaphor, not a mechanism." [ 46 ] He wanted to know the actual mechanisms by which self-regulating homeostasis was achieved. In his defense of Gaia, David Abram argues that Gould overlooked the fact that "mechanism", itself, is a metaphor — albeit an exceedingly common and often unrecognized metaphor — one which leads us to consider natural and living systems as though they were machines organized and built from outside (rather than as autopoietic or self-organizing phenomena). Mechanical metaphors, according to Abram, lead us to overlook the active or agent quality of living entities, while the organismic metaphors of the Gaia hypothesis accentuate the active agency of both the biota and the biosphere as a whole. [ 47 ] [ 48 ] With regard to causality in Gaia, Lovelock argues that no single mechanism is responsible, that the connections between the various known mechanisms may never be known, that this is accepted in other fields of biology and ecology as a matter of course, and that specific hostility is reserved for his own hypothesis for other reasons. [ 49 ]

Aside from clarifying his language and understanding of what is meant by a life form, Lovelock himself ascribes most of the criticism to a lack of understanding of non-linear mathematics by his critics, and a linearizing form of greedy reductionism in which all events have to be immediately ascribed to specific causes before the fact. He also states that most of his critics are biologists but that his hypothesis includes experiments in fields outside biology, and that some self-regulating phenomena may not be mathematically explainable. [ 49 ]

4.1. Natural Selection and Evolution

Lovelock has suggested that global biological feedback mechanisms could evolve by natural selection, stating that organisms that improve their environment for their survival do better than those that damage their environment. However, in the early 1980s, W. Ford Doolittle and Richard Dawkins separately argued against this aspect of Gaia. Doolittle argued that nothing in the genome of individual organisms could provide the feedback mechanisms proposed by Lovelock, and therefore the Gaia hypothesis proposed no plausible mechanism and was unscientific. [ 44 ] Dawkins meanwhile stated that for organisms to act in concert would require foresight and planning, which is contrary to the current scientific understanding of evolution. [ 45 ] Like Doolittle, he also rejected the possibility that feedback loops could stabilize the system.

Lynn Margulis, a microbiologist who collaborated with Lovelock in supporting the Gaia hypothesis, argued in 1999 that "Darwin's grand vision was not wrong, only incomplete. In accentuating the direct competition between individuals for resources as the primary selection mechanism, Darwin (and especially his followers) created the impression that the environment was simply a static arena". She wrote that the composition of the Earth's atmosphere, hydrosphere, and lithosphere are regulated around "set points" as in homeostasis, but those set points change with time. [ 50 ]

Evolutionary biologist W. D. Hamilton called the concept of Gaia Copernican, adding that it would take another Newton to explain how Gaian self-regulation takes place through Darwinian natural selection. [ 21 ] More recently Ford Doolittle building on his and Inkpen's ITSNTS (It's The Song Not The Singer) proposal [ 51 ] proposed that differential persistence can play a similar role to differential reproduction in evolution by natural selections, thereby providing a possible reconciliation between the theory of natural selection and the Gaia hypothesis. [ 52 ]

4.2. Criticism in the 21st Century

The Gaia hypothesis continues to be broadly skeptically received by the scientific community. For instance, arguments both for and against it were laid out in the journal Climatic Change in 2002 and 2003. A significant argument raised against it are the many examples where life has had a detrimental or destabilising effect on the environment rather than acting to regulate it. [ 53 ] [ 54 ] Several recent books have criticised the Gaia hypothesis, expressing views ranging from "... the Gaia hypothesis lacks unambiguous observational support and has significant theoretical difficulties" [ 55 ] to "Suspended uncomfortably between tainted metaphor, fact, and false science, I prefer to leave Gaia firmly in the background" [ 56 ] to "The Gaia hypothesis is supported neither by evolutionary theory nor by the empirical evidence of the geological record". [ 57 ] The CLAW hypothesis, [ 9 ] initially suggested as a potential example of direct Gaian feedback, has subsequently been found to be less credible as understanding of cloud condensation nuclei has improved. [ 58 ] In 2009 the Medea hypothesis was proposed: that life has highly detrimental (biocidal) impacts on planetary conditions, in direct opposition to the Gaia hypothesis. [ 59 ]

In a 2013 book-length evaluation of the Gaia hypothesis considering modern evidence from across the various relevant disciplines, Toby Tyrrell concluded that: "I believe Gaia is a dead end*. Its study has, however, generated many new and thought provoking questions. While rejecting Gaia, we can at the same time appreciate Lovelock's originality and breadth of vision, and recognize that his audacious concept has helped to stimulate many new ideas about the Earth, and to champion a holistic approach to studying it". [ 60 ] Elsewhere he presents his conclusion "The Gaia hypothesis is not an accurate picture of how our world works". [ 61 ] This statement needs to be understood as referring to the "strong" and "moderate" forms of Gaia—that the biota obeys a principle that works to make Earth optimal (strength 5) or favourable for life (strength 4) or that it works as a homeostatic mechanism (strength 3). The latter is the "weakest" form of Gaia that Lovelock has advocated. Tyrrell rejects it. However, he finds that the two weaker forms of Gaia—Coeveolutionary Gaia and Influential Gaia, which assert that there are close links between the evolution of life and the environment and that biology affects the physical and chemical environment—are both credible, but that it is not useful to use the term "Gaia" in this sense and that those two forms were already accepted and explained by the processes of natural selection and adaptation. [ 62 ]

- Lapenis, Andrei G. (2002). "Directed Evolution of the Biosphere: Biogeochemical Selection or Gaia?". The Professional Geographer 54 (3): 379–391. doi:10.1111/0033-0124.00337. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2F0033-0124.00337

- David Landis Barnhill, Roger S. Gottlieb(eds.), Deep Ecology and World Religions: New Essays on Sacred Ground, SUNY Press, 2010, p. 32.

- Lovelock, James. The Vanishing Face of Gaia. Basic Books, 2009, p. 255. ISBN:978-0-465-01549-8

- Kleidon, Axel. How does the earth system generate and maintain thermodynamic disequilibrium and what does it imply for the future of the planet?. Article submitted to the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society on Thu, 10 Mar 2011

- Lovelock, James. The Vanishing Face of Gaia. Basic Books, 2009, p. 179. ISBN:978-0-465-01549-8

- Owen, T.; Cess, R.D.; Ramanathan, V. (1979). "Earth: An enhanced carbon dioxide greenhouse to compensate for reduced solar luminosity". Nature 277 (5698): 640–2. doi:10.1038/277640a0. Bibcode: 1979Natur.277..640O. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F277640a0

- Lovelock, James, (1995) "The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth" (W.W.Norton & Co)

- Hoffman, P.F. 2001. Snowball Earth theory http://www.snowballearth.org

- Charlson, R. J., Lovelock, J. E, Andreae, M. O. and Warren, S. G. (1987). "Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate". Nature 326 (6114): 655–661. doi:10.1038/326655a0. Bibcode: 1987Natur.326..655C. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F326655a0

- Lovelock, James. The Vanishing Face of Gaia. Basic Books, 2009, ISBN:978-0-465-01549-8

- Lovelock J., NBC News. Link Published 23 April 2012, accessed 22 August 2012. http://worldnews.nbcnews.com/_news/2012/04/23/11144098-gaia-scientist-james-lovelock-i-was-alarmist-about-climate-change?lite

- Watson, A.J.; Lovelock, J.E (1983). "Biological homeostasis of the global environment: the parable of Daisyworld". Tellus 35B (4): 286–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0889.1983.tb00031.x. Bibcode: 1983TellB..35..284W. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1600-0889.1983.tb00031.x

- Kirchner, James W. (2003). "The Gaia Hypothesis: Conjectures and Refutations". Climatic Change 58 (1–2): 21–45. doi:10.1023/A:1023494111532. https://dx.doi.org/10.1023%2FA%3A1023494111532

- Segar, Douglas (2012). The Introduction to Ocean Sciences. Library of Congress. pp. Chapter 5 3rd Edition. ISBN 978-0-9857859-0-1. http://www.reefimages.com/oceans/SegarOcean3Chap05.pdf.

- Gorham, Eville (1 January 1991). "Biogeochemistry: its origins and development". Biogeochemistry (Kluwer Academic) 13 (3): 199–239. doi:10.1007/BF00002942. ISSN 1573-515X. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2FBF00002942

- "Scientia Marina: List of Issues" (in en). http://scimar.icm.csic.es/scimar/index.php/secId/6/IdArt/209/.

- Lovelock, James. The Vanishing Face of Gaia. Basic Books, 2009, p. 163. ISBN:978-0-465-01549-8

- Anbar, A.; Duan, Y.; Lyons, T.; Arnold, G.; Kendall, B.; Creaser, R.; Kaufman, A.; Gordon, G. et al. (2007). "A whiff of oxygen before the great oxidation event?". Science 317 (5846): 1903–1906. doi:10.1126/science.1140325. PMID 17901330. Bibcode: 2007Sci...317.1903A. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.1140325

- Harding, Stephan (2006). Animate Earth. Chelsea Green Publishing. pp. 65. ISBN 978-1-933392-29-5.

- "Interagency Report Says Harmful Algal Blooms Increasing". 12 September 2007. http://www.publicaffairs.noaa.gov/releases2007/sep07/noaa07-r435.html.

- Lovelock, James. The Vanishing Face of Gaia. Basic Books, 2009, pp. 195-197. ISBN:978-0-465-01549-8

- Capra, Fritjof (1996). The web of life: a new scientific understanding of living systems. Garden City, N.Y: Anchor Books. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-385-47675-1. https://archive.org/details/weboflifenewscie00capr/page/23.

- S.R. Weart, 2003, The Discovery of Global Warming, Cambridge, Harvard Press

- 100 Photographs that Changed the World by Life - The Digital Journalist http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0309/lm11.html

- Lovelock, J.E. (1965). "A physical basis for life detection experiments". Nature 207 (7): 568–570. doi:10.1038/207568a0. PMID 5883628. Bibcode: 1965Natur.207..568L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F207568a0

- "Geophysiology". http://www.jameslovelock.org/page4.html.

- Lovelock, J.E.; Giffin, C.E. (1969). "Planetary Atmospheres: Compositional and other changes associated with the presence of Life". Advances in the Astronautical Sciences 25: 179–193. ISBN 978-0-87703-028-7.

- J. E. Lovelock (1972). "Gaia as seen through the atmosphere". Atmospheric Environment 6 (8): 579–580. doi:10.1016/0004-6981(72)90076-5. Bibcode: 1972AtmEn...6..579L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2F0004-6981%2872%2990076-5

- Lovelock, J.E.; Margulis, L. (1974). "Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: the Gaia hypothesis". Tellus. Series A (Stockholm: International Meteorological Institute) 26 (1–2): 2–10. doi:10.1111/j.2153-3490.1974.tb01946.x. ISSN 1600-0870. Bibcode: 1974Tell...26....2L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.2153-3490.1974.tb01946.x

- Lovelock, John and Sidney Epton, (February 8, 1975). "The quest for Gaia". New Scientist, p. 304. https://books.google.com/books?id=pnV6UYEkU4YC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Lovelock, James 2001

- Hamilton, W.D.; Lenton, T.M. (1998). "Spora and Gaia: how microbes fly with their clouds" (PDF). Ethology Ecology & Evolution 10 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/08927014.1998.9522867. http://ejour-fup.unifi.it/index.php/eee/article/viewFile/787/733.

- Turney, Jon (2003). Lovelock and Gaia: Signs of Life. UK: Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-458-0. https://archive.org/details/lovelockgaiasign0000turn.

- J. E. Lovelock (1990). "Hands up for the Gaia hypothesis". Nature 344 (6262): 100–2. doi:10.1038/344100a0. Bibcode: 1990Natur.344..100L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F344100a0

- Volk, Tyler (2003). Gaia's Body: Toward a Physiology of Earth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-72042-7.

- Joseph, Lawrence E. (November 23, 1986). "Britain's Whole Earth Guru". The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/11/23/magazine/britain-s-whole-earth-guru.html.

- Bunyard, Peter (1996), "Gaia in Action: Science of the Living Earth" (Floris Books)

- Turney, Jon. "Lovelock and Gaia: Signs of Life" (Revolutions in Science)

- Kirchner, James W. (1989). "The Gaia hypothesis: Can it be tested?". Reviews of Geophysics 27 (2): 223. doi:10.1029/RG027i002p00223. Bibcode: 1989RvGeo..27..223K. https://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2FRG027i002p00223

- Lenton, TM; Lovelock, JE (2000). "Daisyworld is Darwinian: Constraints on adaptation are important for planetary self-regulation". Journal of Theoretical Biology 206 (1): 109–14. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2000.2105. PMID 10968941. Bibcode: 2000JThBi.206..109L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1006%2Fjtbi.2000.2105

- Simón, Federico (21 June 2000). "GEOLOGÍA Enfoque multidisciplinar La hipótesis Gaia madura en Valencia con los últimos avances científicos" (in es). El País. http://elpais.com/diario/2000/06/21/futuro/961538404_850215.html.

- American Geophysical Union. "General Information Chapman Conference on the Gaia Hypothesis University of Valencia Valencia, Spain June 19-23, 2000 (Monday through Friday)". AGU Meetings. http://www.agu.org/meetings/chapman/chapman_archive/cc00bcall.html.

- Official Site of Arlington County Virginia. "Gaia Theory Conference at George Mason University Law School". http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/Communications/PressReleases/page7530.aspx.

- Doolittle, W. F. (1981). "Is Nature Really Motherly". The Coevolution Quarterly Spring: 58–63.

- Dawkins, Richard (1982). The Extended Phenotype: the Long Reach of the Gene. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286088-0.

- Gould S.J. (June 1997). "Kropotkin was no crackpot". Natural History 106: 12–21. http://libcom.org/library/kropotkin-was-no-crackpot.

- Abram, D. (1988) "The Mechanical and the Organic: On the Impact of Metaphor in Science" in Scientists on Gaia, edited by Stephen Schneider and Penelope Boston, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1991

- "The Mechanical and the Organic". http://www.wildethics.org/essays/the_mechanical_and_the_organic.html.

- Lovelock, James (2001), Homage to Gaia: The Life of an Independent Scientist (Oxford University Press)

- Margulis, Lynn. Symbiotic Planet: A New Look At Evolution. Houston: Basic Book 1999

- Doolittle WF, Inkpen SA. Processes and patterns of interaction as units of selection: An introduction to ITSNTS thinking. PNAS April 17, 2018 115 (16) 4006-4014 https://www.pnas.org/content/115/16/4006

- Doolittle, W. Ford (2017). "Darwinizing Gaia". Journal of Theoretical Biology 434: 11–19. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.02.015. PMID 28237396. Bibcode: 2017JThBi.434...11D. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.02.015.

- Kirchner, James W. (2002), "Toward a future for Gaia theory", Climatic Change 52 (4): 391–408, doi:10.1023/a:1014237331082 https://dx.doi.org/10.1023%2Fa%3A1014237331082

- Volk, Tyler (2002), "The Gaia hypothesis: fact, theory, and wishful thinking", Climatic Change 52 (4): 423–430, doi:10.1023/a:1014218227825 https://dx.doi.org/10.1023%2Fa%3A1014218227825

- Waltham, David (2014). Lucky Planet: Why Earth is Exceptional – and What that Means for Life in the Universe. Icon Books. ISBN 9781848316560. https://archive.org/details/luckyplanetwhyea0000walt.

- Beerling, David (2007). The Emerald Planet: How plants changed Earth's history. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280602-4. http://ukcatalogue.oup.com/product/9780192806024.do.

- Cockell, Charles; Corfield, Richard; Dise, Nancy; Edwards, Neil; Harris, Nigel (2008). An Introduction to the Earth-Life System. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521729536. http://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/subjects/earth-and-environmental-science/palaeontology-and-life-history/introduction-earth-life-system.

- Quinn, P.K.; Bates, T.S. (2011), "The case against climate regulation via oceanic phytoplankton sulphur emissions", Nature 480 (7375): 51–56, doi:10.1038/nature10580, PMID 22129724, Bibcode: 2011Natur.480...51Q, https://zenodo.org/record/1233319

- Peter Ward (2009), The Medea Hypothesis: Is Life on Earth Ultimately Self-Destruction?, ISBN:0-691-13075-2

- Tyrrell, Toby (2013), On Gaia: A Critical Investigation of the Relationship between Life and Earth, Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 209, ISBN 9780691121581, http://press.princeton.edu/titles/9959.html

- Tyrrell, Toby (26 October 2013), "Gaia: the verdict is…", New Scientist 220 (2940): 30–31, doi:10.1016/s0262-4079(13)62532-4 https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fs0262-4079%2813%2962532-4