The Unlikeliest Pandemic Success Story

How did a tiny, poor nation manage to suffer only one death from the coronavirus?

O n January 7 , a 34-year-old man who had been admitted to a hospital in Bhutan’s capital, Thimphu, with preexisting liver and kidney problems died of COVID-19. His was the country’s first death from the coronavirus. Not the first death that day, that week, or that month: the very first coronavirus death since the pandemic began.

How is this possible? Since the novel coronavirus was first identified more than a year ago, health systems in rich and poor countries have approached collapse, economies worldwide have been devastated, millions of lives have been lost. How has Bhutan—a tiny, poor nation best known for its guiding policy of Gross National Happiness, which balances economic development with environmental conservation and cultural values—managed such a feat? And what can we in the United States, which has so tragically mismanaged the crisis, learn from its success?

In fact, what can the U.S. and other wealthy countries learn from the array of resource-starved counterparts that have better weathered the coronavirus pandemic, even if those nations haven’t achieved Bhutan’s impressive statistics? Countries such as Vietnam, which has so far logged only 35 deaths, Rwanda, with 226, Senegal, with 700, and plenty of others have negotiated the crisis far more smoothly than have Europe and North America.

These nations offer plenty of lessons, from the importance of attentive leadership, the need to ensure that people have enough provisions and financial means to follow public-health guidance, and the shared understanding that individuals and communities must sacrifice to protect the well-being of all: elements that have been sorely lacking in the U.S.

America has “the world’s best medical-rescue system—we have unbelievable ICUs,” Asaf Bitton, executive director of Ariadne Labs, a Boston-based center for health-systems innovation, told me. But, he said, we have neglected a public-health focus on prevention, which socially cohesive low- and middle-income countries have no choice but to adopt, because a runaway epidemic would quickly overwhelm them.

“People say the COVID disaster in America has been about a denial of science. But what we couldn’t agree on is the social compact we would need to make painful choices together in unity, for the collective good,” Bitton added. “I don’t know whether, right now in the U.S., we can have easy or effective conversations about a common good. But we need to start.”

O ver the course of three reporting trips to Bhutan since 2012, a word I heard innumerable times was resilience . It alluded to the fact that Bhutan has never been colonized, and to its people’s ability to bear hardships and make sacrifices. Resilience, I came to learn, is core to the national identity.

That mattered when the coronavirus began spreading early last year. At the time, Bhutan looked like a ripe target. It had only 337 physicians for a population of around 760,000—less than half the World Health Organization’s recommended ratio of doctors to people—and only one of these physicians had advanced training in critical care. It had barely 3,000 health workers, and one PCR machine to test viral samples. It was on the United Nations’ list of least developed countries, with a per capita GDP of $3,412. And while its northern frontier with China had been closed for decades, it shared a porous 435-mile border with India, which now has the world’s second-highest number of recorded cases and fourth-highest number of reported deaths.

Yet from the first note of alarm, Bhutan moved swiftly and astutely, its actions firmly rooted in the latest science.

On December 31, 2019, China first reported to the WHO a pneumonia outbreak of unknown cause. By January 11, Bhutan had started drafting its National Preparedness and Response Plan, and on January 15 , it began screening for symptoms of respiratory ailments and was using infrared fever scanning at its international airport and other points of entry.

Around midnight on March 6, Bhutan confirmed its first case of COVID-19: a 76-year-old American tourist. Six hours and 18 minutes later, some 300 possible contacts, and contacts of contacts, had been traced and quarantined. “It must have been a record,” Minister of Health Dechen Wangmo—a plain-spoken Yale-educated epidemiologist— told the national newspaper Kuensel , with evident pride. Airlifted to the U.S., the patient was expected to die, but survived. According to an account in The Washington Post , his doctors in Maryland told him, “Whatever they tried in Bhutan probably saved your life.”

Read: Joe Biden’s ‘America first’ vaccine strategy

In March, the Bhutanese government also started issuing clear, concise daily updates and sharing helpline numbers. It barred tourists, closed schools and public institutions, shut gyms and movie theaters, began flexible working hours, and relentlessly called for face masks, hand hygiene, and physical distancing. On March 11, the WHO tardily deemed COVID-19 a pandemic. Five days later, Bhutan instituted mandatory quarantine for all Bhutanese with possible exposure to the virus—including the thousands of expatriates who boarded chartered planes back to their homeland—and underwrote every aspect, such as free accommodation and meals in tourist-level hotels. It isolated all positive cases, even those who were asymptomatic, in medical facilities, so early symptoms could be treated immediately, and provided psychological counseling for those in quarantine and isolation.

Bhutan then went further. At the end of March, health officials extended the mandatory quarantine from 14 to 21 days—a full week longer than what the WHO was (and still is) recommending. The rationale: A 14-day quarantine leaves about an 11 percent chance that, after being released, a person could still be incubating the infection and eventually become contagious. Bhutan’s extensive testing regimen for people in quarantine, Wangmo added at a press conference , was “a gold standard.”

While President Donald Trump was railing against coronavirus surveillance, Bhutan launched a huge testing and tracing program, and created a contact-tracing app. Last fall, the health ministry rolled out a prevention initiative called “ Our Gyenkhu ”—“Our Responsibility”—featuring influencers such as actors, visual artists, bloggers, and sports personalities. When, in August, a 27-year-old woman became the first Bhutanese in the country to test positive for COVID-19 outside of quarantine, a three-week national lockdown followed, with the government ramping up testing and tracing even more, and delivering food, medicine, and other essentials to every household in the land. In December, when a flu clinic in Thimphu turned up the first case of community transmission since the summer, the nation again entered strict lockdown—and again, a full-throttle campaign prevailed against the virus, which has been all but snuffed out for the time being.

In tandem with this rigorous public-health response came swells of civic compassion from every level of society. In April, King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck launched a relief fund that has so far handed out $19 million in financial assistance to more than 34,000 Bhutanese whose livelihoods have been hurt by the pandemic, a program extended until at least the end of March. The government created a country-wide registry for vulnerable citizens, and has sent care packages containing hand sanitizer, vitamins, and other items to more than 51,000 Bhutanese over the age of 60. The Queen Mother gave a frank address to the nation, calling on the authorities to ensure services for sexual and reproductive health, maternal, newborn, and child health care, and services for gender-based violence, which she deemed “essential.” Thousands of people signed up to leave their homes and families for extended periods of time to join the national corps of orange-uniformed volunteers known as DeSuung . Bhutan’s monastic community—highly influential in a Buddhist and still largely traditional culture—not only pointedly reinforced public-health messaging but also prayed daily for the well-being of all people during the crisis, not just the Bhutanese.

Read: The mutated virus is a ticking time bomb

Government officials modeled the same altruism. During the country’s summer lockdown, Wangmo, the health minister, slept in ministry facilities for weeks, away from her young son. Prime Minister Lotay Tshering, a highly respected physician who continued to perform surgeries on Saturdays during most of the crisis, slept every night during the lockdown on a window seat in his office— a photo in the newspaper The Bhutanese showed his makeshift bed’s rumpled blankets and an ironing board standing nearby. Members of Parliament gave up a month’s salary for the response effort; hoteliers offered their properties as free quarantine facilities; farmers donated crops. When lights in the Ministry of Health’s offices burned all night, locals brought hot milk tea and homemade ema datshi —scorching chilies and cheese, the national dish.

“I have complained about ‘small-society syndrome’ and how suffocating it can get. But I believe it is this very closeness that has kept us together,” Namgay Zam, a prominent journalist in Bhutan, told me. “I don’t think any other country can say that leaders and ordinary people enjoy such mutual trust. This is the main reason for Bhutan’s success.”

W hile Bhutan might be culturally unique, its experience offers several lessons for affluent nations.

First, hope that you are lucky and your country’s leaders are thoroughly engaged. Bhutan had trusted, smart, and hands-on direction from its king, whose moral authority carries great weight. He explicitly told government leaders that even one death from COVID-19 would be too much for a small nation that regards itself as a family, pressed officials for detailed plans covering every possible pandemic scenario, and made multiple trips to the front lines, encouraging health workers, volunteers, and others. His crucial role also sidetracked any political gamesmanship; in Bhutan, the opposition in Parliament joined forces with the ruling party.

Second, invest in preparedness. Bhutan set up a health emergency operations center and a WHO emergency operations center in 2018, and had also invested in medical camp kit tents, initially thinking they would be deployed in disaster-relief zones; the tents were repurposed to screen and treat patients with respiratory symptoms. In 2019, the country upgraded its Royal Centre for Disease Control lab, equipping it to handle not only new and deadly influenza viruses on the horizon, but also SARS-CoV-2. Most presciently, in November 2019, the WHO and Bhutan’s health ministry staged a simulation at the country’s international airport . The scenario: a passenger arriving from abroad with a suspected infection caused by a new strain of coronavirus. All these measures reflect what Bitton sees as a dynamic, system-wide self-awareness. “You could call it humility; you could call it curiosity,” he said. “It’s this idea of, wow, we have a lot to learn.”

Third, act fast and buy time. “The countries that responded early and before the virus got entrenched—in particular, before it got to the vulnerable populations—seem to all have done better,” Jennifer Nuzzo, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security , told me. Bhutan’s system of community-based primary care had sowed the concept of prevention, and its free universal health care and testing meant that logistics and supply chains were already in place.

Fourth, draw on existing strengths. When Bhutan added five more PCR machines to its testing stock, up from just one, it needed people to collect samples from the field and operate the devices. So it shifted technicians from livestock-health and food-safety programs, and trained university students. When it became clear that one ICU physician was not enough, it instructed other doctors and nurses in clinical management of respiratory infections and WHO protocols. “This is the lesson from Bhutan,” Rui Paulo de Jesus, its WHO country representative, told me. “Utilize the resources you have.”

Finally, make it possible for people to actually follow public-health guidance by providing economic and social support to those who need to quarantine or isolate. Nuzzo calls these “wraparound services.” But Tenzing Lamsang, an investigative journalist and editor of The Bhutanese , believes the term doesn’t do justice to Bhutan’s deeper policy impulses. “Bhutan’s approach as a Buddhist country, a country that values Gross National Happiness, is different from a typical technocratic approach,” he told me, noting that its pandemic plan covered “all aspects of well-being.”

Read: Where year two of the pandemic will take us

Other countries illustrate many of these approaches. Senegal acted early, barring international arrivals and imposing regional travel restrictions, enforcing curfews and business closures, and launching an economic and social resilience program to make up for lost income among the poor; after barely skirting the 2014–16 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, it also bolstered staffing for an emergency operations center and conducted mock drills. Rwanda blanketed the country with random testing and contact tracing, relying on the same lab technologies used for tracking HIV cases. Vietnam declared an epidemic on February 1, 2020, and deployed its provincial governments to swiftly detect infections, close nonessential businesses, enforce social distancing, and monitor border crossings.

T here are certainly plenty of caveats around the idea of trying to replicate Bhutan’s values or transplant its strategies. As Nuzzo pointed out, political systems vary significantly, and one nation’s assumptions might not thrive on alien terrain. Moreover, coronavirus transmission can take wild turns. And until Bhutanese are vaccinated, the kingdom will need to play a flawless game of containment. “As Buddhists,” a Kuensel editorial in September reflected, “we learn that this reality changes every moment.”

Recommended Reading

A Single Day With Fewer Than 100,000 Cases of COVID-19

Why America Resists Learning From Other Countries

Where the Pandemic Is Only Getting Worse

For now, though, Bhutan has helped define pandemic resilience. “What I learned from Bhutan is that the health sector alone cannot do much to protect people’s health,” de Jesus told me. Lamsang agreed. Pandemic resilience, he said, came from “things that we don’t count normally, like your social capital and the willingness of society to come together for the common good.”

It is tempting to dismiss Bhutan or other small, communitarian countries as irrelevant models for the United States. To be sure, Bhutan is no paradise. It has its share of quarantine dodgers and anti-vaxxers , “maskholes” and “covidiots,” all duly called out on social media. And like every other nation, when this crisis is over, it will have to reckon with long-standing problems—issues including youth unemployment and the effects of climate change.

But its victory, at least so far, in staving off the worst of the pandemic might give Bhutan the confidence and drive it needs to tackle these other challenges—and on its own terms. After all, that’s another aspect of resilience: moving forward when the crisis has passed.

What the world can learn from Bhutan’s rapid COVID vaccine rollout

Senior Lecturer in Supply Chain Management, Liverpool John Moores University

Senior Lecturer in Business and Management, Edge Hill University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Liverpool John Moores University and Edge Hill University provide funding as members of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Nearly half the world’s population has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. But figures vary widely between countries. Many low and middle-income countries have barely started their vaccination campaigns.

But the tiny Himalayan nation of Bhutan isn’t one of them. By the end of July, it had fully vaccinated 90% of its adults. Despite having few doctors and nurses, across just three weeks in the summer it delivered a second vaccine dose to nearly every adult in the country. This is a remarkable success story for one of the least developed countries in the world.

Health minister Dechen Wangmo credits solidarity, Bhutan’s small size and its science-based policymaking for its success. Its achievement highlights how logistical challenges and vaccine hesitancy can be overcome.

Donations are crucial

Bhutan’s success wouldn’t have been possible without international cooperation. Its first vaccines were donated by India . By March 2021, India had sent 450,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, enough to give all eligible adults in Bhutan their first dose in the spring.

But getting hold of second doses was a challenge. India’s second wave soon arrived, causing it to prioritise domestic immunisations and ban vaccine exports . Bhutan’s immediate source of doses had dried up, while India’s mounting caseload over the border posed a rapidly increasing infection risk.

After a tense wait, 500,000 doses of the Moderna vaccine came from the US through Covax , the vaccine-sharing initiative. An additional 250,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine came from Denmark, followed by supplies of AstraZeneca, Pfizer and Sinopharm vaccines from Bulgaria, Croatia, China and other countries.

Planning makes the logistics work

Distribution was another big part of the puzzle. Bhutan is remote. Land access is only possible on a few roads from India. The Covax vaccines arrived by air at Paro International Airport. One of the most challenging landings in the world, Paro sits in a deep valley. The surrounding peaks are as high as 5,500 metres.

Domestic transport is also challenging. Bhutan’s population of almost 750,000 is scattered over an area roughly the size of Switzerland. Not all of the mountainous country is accessible by road.

Because of this, the health ministry had to plan in detail how to get all adults their first and second doses as quickly as possible. This involved extensive field visits to remote districts, to map where people were and identify possible vaccination sites. The visits also established ways of supplying these sites – by road, air or even on foot for the most inaccessible areas.

Schools, monasteries and other public buildings were used as vaccination centres. Keeping vaccines sufficiently cold at smaller locations could be challenging, so district hubs were created across the country to store vaccines and coordinate distribution to smaller sites as doses were needed. Domestic flights and a helicopter shuttle service were used to move doses around the country.

And a digital platform – the Bhutan Vaccination System – helped speed up the rollout of second doses. It allowed people to pre-register online before receiving their jab and so not waste time filling in personal details at the vaccine centre.

User research was also central to Bhutan’s planning phase . The health ministry ran online conferences with healthcare workers and authorities at district and village level to highlight expected challenges. Simultaneously, the ministry mobilised and trained healthcare workers to vaccinate and monitor patients.

But with only 376 doctors in the country, the planning phase soon identified a shortage of medical personnel. So 50 registered doctors known to be studying overseas were recalled .

Nurses and healthcare workers were supported by the “ Guardians of the Peace ” – a part volunteering, part national service programme that has been run in Bhutan for the last decade and has 4,500 members. These guardians encouraged people to get vaccinated and helped manage vaccine centres.

Set a good example

Good leadership has also been a hallmark of Bhutan’s vaccine rollout. There are high levels of trust in the country’s political leaders. This has been helped during the pandemic by the government having two doctors and two public health experts in its 11-member cabinet . The prime minister and the health minister have spent substantial time on the national response to COVID-19.

The role of King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck should also not be underestimated. While Bhutan became a constitutional monarchy in 2008, transitioning to having a democratically elected government, the king is still much revered. His presence has been felt throughout the country, as he has travelled to remote settlements to oversee protection measures.

One such journey was a five-day trek to meet and thank healthcare workers. Leading by example, he quarantines in a hotel whenever he returns to the capital.

Bhutan’s politicians also engaged with the public to overcome vaccine hesitancy. A survey studied the public’s concerns, with the government’s response focusing on communicating the science behind the vaccine. Uptake was promoted by social media influencers and television and film personalities.

Cultural sensitivity was also crucial to ensuring public support. For example, Buddhist monks determined when to roll the vaccines out and picked the most auspicious time (the majority of the population is Buddhist). Monks also determined that the first dose should be administered by a women and given to a women born in the Year of the Monkey.

Not every country can achieve what Bhutan has. Having a small population and high trust in authorities facilitated this rollout. But Bhutan demonstrates that a fast and equitable vaccine rollout is possible in low and middle-income countries.

What’s clear is that the international community has to work together on the provision of vaccines. Support may also be needed to manage distribution, as getting doses to remote parts of the world’s least developed countries is a huge challenge. Bhutan, though, should offer encouragement that meeting it is possible.

- Coronavirus

- Coronavirus insights

- COVID-19 vaccine rollout

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Program Development Officer - Business Processes

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

How Bhutan has kept COVID-19 at bay

Bhutan, a tiny and poor nation in South Asia, has had only one COVID-19 death since the pandemic began. Experts say the country has succeeded in keeping the disease at bay through attentive leadership; the provision of enough economic and social support so that citizens are able to follow public-health guidance; and a sense of shared responsibility that permeates Bhutanese culture.

In a February 10, 2021, article in The Atlantic, Asaf Bitton , executive director of Ariadne Labs , offered thoughts on why Bhutan has handled the pandemic much better than the U.S., a nation with far more resources. He noted that while the U.S. has “the world’s best medical-rescue system,” the nation has neglected a public-health focus on prevention—which Bhutan and some other socially cohesive low- and middle-income countries have adopted to avoid being overwhelmed by epidemics.

“People say the COVID disaster in America has been about a denial of science. But what we couldn’t agree on is the social compact we would need to make painful choices together in unity, for the collective good,” Bitton said.

The article was written by Madeline Drexler , visiting scientist at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and former editor of Harvard Public Health magazine.

Read the Atlantic article: The Unlikeliest Pandemic Success Story

Bhutan: Coronavirus Pandemic Country Profile

Research and data: Edouard Mathieu, Hannah Ritchie, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Cameron Appel, Daniel Gavrilov, Charlie Giattino, Joe Hasell, Bobbie Macdonald, Saloni Dattani, Diana Beltekian, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, and Max Roser

- Coronavirus

- Data explorer

- Hospitalizations

Vaccinations

- Mortality risk

- Excess mortality

- Policy responses

Build on top of our work freely

- All our code is open-source

- All our research and visualizations are free for everyone to use for all purposes

Select countries to show in all charts

Confirmed cases.

- What is the daily number of confirmed cases?

- Daily confirmed cases: how do they compare to other countries?

- What is the cumulative number of confirmed cases?

- Cumulative confirmed cases: how do they compare to other countries?

- Biweekly cases : where are confirmed cases increasing or falling?

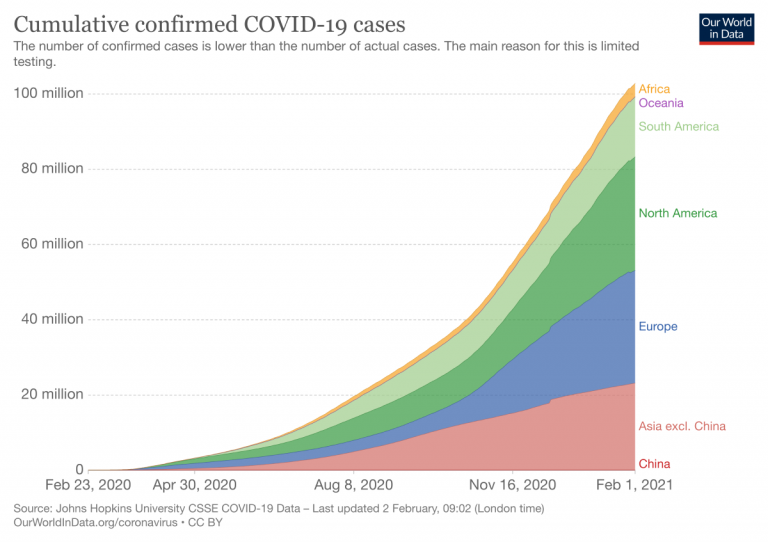

- Global cases in comparison: how are cases changing across the world?

Bhutan: What is the daily number of confirmed cases?

Related charts:.

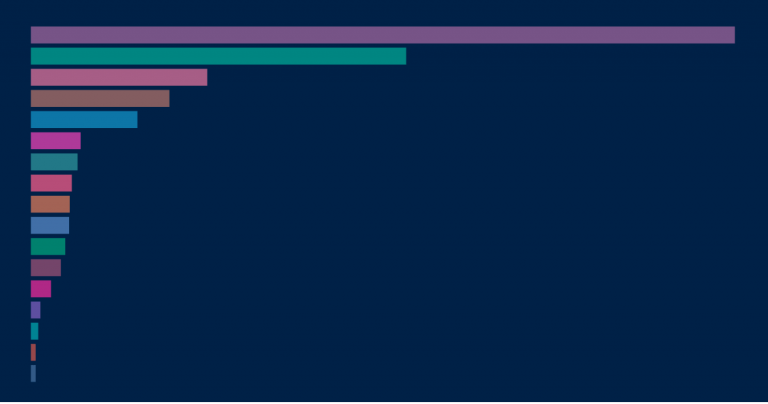

Which world regions have the most daily confirmed cases?

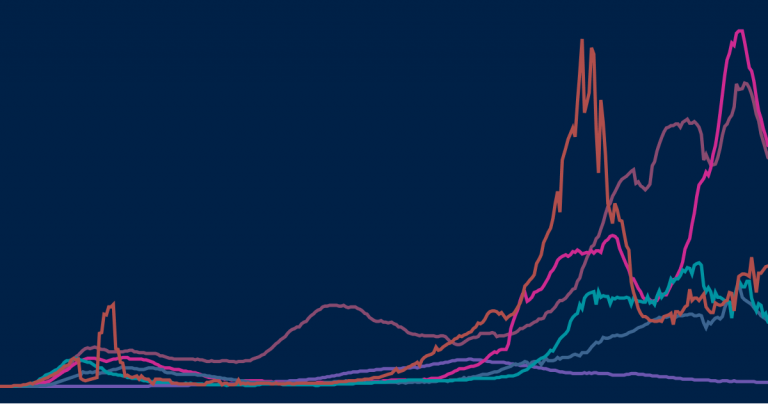

This chart shows the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases per day . This is shown as the seven-day rolling average.

What is important to note about these case figures?

- The reported case figures on a given date do not necessarily show the number of new cases on that day – this is due to delays in reporting.

- The number of confirmed cases is lower than the true number of infections – this is due to limited testing. In a separate post we discuss how models of COVID-19 help us estimate the true number of infections .

→ We provide more detail on these points in our page on Cases of COVID-19 .

Five quick reminders on how to interact with this chart

- By clicking on Edit countries and regions you can show and compare the data for any country in the world you are interested in.

- If you click on the title of the chart, the chart will open in a new tab. You can then copy-paste the URL and share it.

- You can switch the chart to a logarithmic axis by clicking on ‘LOG’.

- If you move both ends of the time-slider to a single point you will see a bar chart for that point in time.

- Map view: switch to a global map of confirmed cases using the ‘MAP’ tab at the bottom of the chart.

Bhutan: Daily confirmed cases: how do they compare to other countries?

Differences in the population size between different countries are often large. To compare countries, it is insightful to look at the number of confirmed cases per million people – this is what the chart shows.

Keep in mind that in countries that do very little testing the actual number of cases can be much higher than the number of confirmed cases shown here.

Three tips on how to interact with this map

- By clicking on any country on the map you see the change over time in this country.

- By moving the time slider (below the map) you can see how the global situation has changed over time.

- You can focus on a particular world region using the dropdown menu to the top-right of the map.

Bhutan: What is the cumulative number of confirmed cases?

Which world regions have the most cumulative confirmed cases?

How do the number of tests compare to the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases?

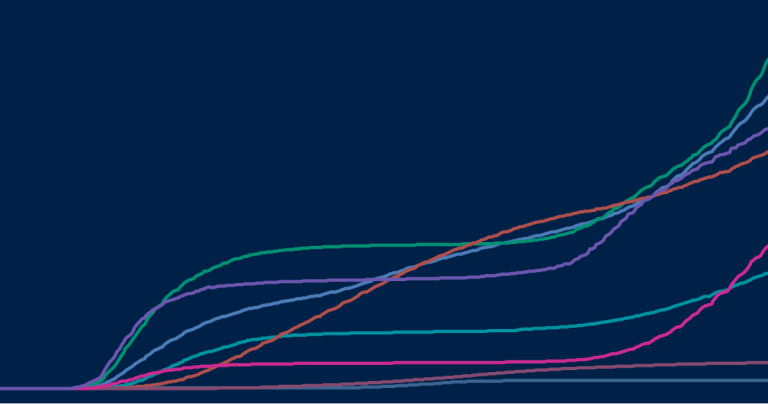

The previous charts looked at the number of confirmed cases per day – this chart shows the cumulative number of confirmed cases since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In all our charts you can download the data

We want everyone to build on top of our work and therefore we always make all our data available for download. Click on the ‘Download’-tab at the bottom of the chart to download the shown data for all countries in a .csv file.

Bhutan: Cumulative confirmed cases: how do they compare to other countries?

This chart shows the cumulative number of confirmed cases per million people.

Bhutan: Biweekly cases : where are confirmed cases increasing or falling?

Why is it useful to look at biweekly changes in confirmed cases.

For all global data sources on the pandemic, daily data does not necessarily refer to the number of new confirmed cases on that day – but to the cases reported on that day.

Since reporting can vary significantly from day to day – irrespectively of any actual variation of cases – it is helpful to look at a longer time span that is less affected by the daily variation in reporting. This provides a clearer picture of where the pandemic is accelerating, staying the same, or reducing.

The first map here provides figures on the number of confirmed cases in the last two weeks. To enable comparisons across countries it is expressed per million people of the population.

And the second map shows the percentage change (growth rate) over this period: blue are all those countries in which the case count in the last two weeks was lower than in the two weeks before. In red countries the case count has increased.

What is the weekly number of confirmed cases?

What is the weekly change (growth rate) in confirmed cases?

Bhutan: Global cases in comparison: how are cases changing across the world?

In our page on COVID-19 cases , we provide charts and maps on how the number and change in cases compare across the world.

Confirmed deaths

- What is the daily number of confirmed deaths?

- Daily confirmed deaths: how do they compare to other countries?

- What is the cumulative number of confirmed deaths?

- Cumulative confirmed deaths: how do they compare to other countries?

- Biweekly deaths : where are confirmed deaths increasing or falling?

- Global deaths in comparison: how are deaths changing across the world?

Bhutan: What is the daily number of confirmed deaths?

Which world regions have the most daily confirmed deaths?

This chart shows t he number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths per day .

Three points on confirmed death figures to keep in mind

All three points are true for all currently available international data sources on COVID-19 deaths:

- The actual death toll from COVID-19 is likely to be higher than the number of confirmed deaths – this is due to limited testing and challenges in the attribution of the cause of death. The difference between confirmed deaths and actual deaths varies by country.

- How COVID-19 deaths are determined and recorded may differ between countries.

- The death figures on a given date do not necessarily show the number of new deaths on that day, but the deaths reported on that day. Since reporting can vary significantly from day to day – irrespectively of any actual variation of deaths – it is helpful to view the seven-day rolling average of the daily figures as we do in the chart here.

→ We provide more detail on these three points in our page on Deaths from COVID-19 .

Bhutan: Daily confirmed deaths: how do they compare to other countries?

This chart shows the daily confirmed deaths per million people of a country’s population.

Why adjust for the size of the population?

Differences in the population size between countries are often large, and the COVID-19 death count in more populous countries tends to be higher . Because of this it can be insightful to know how the number of confirmed deaths in a country compares to the number of people who live there, especially when comparing across countries.

For instance, if 1,000 people died in Iceland, out of a population of about 340,000, that would have a far bigger impact than the same number dying in the United States, with its population of 331 million. 1 This difference in impact is clear when comparing deaths per million people of each country’s population – in this example it would be roughly 3 deaths/million people in the US compared to a staggering 2,941 deaths/million people in Iceland.

Bhutan: What is the cumulative number of confirmed deaths?

Which world regions have the most cumulative confirmed deaths?

The previous charts looked at the number of confirmed deaths per day – this chart shows the cumulative number of confirmed deaths since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bhutan: Cumulative confirmed deaths: how do they compare to other countries?

This chart shows the cumulative number of confirmed deaths per million people.

Bhutan: Biweekly deaths : where are confirmed deaths increasing or falling?

Why is it useful to look at biweekly changes in deaths.

For all global data sources on the pandemic, daily data does not necessarily refer to deaths on that day – but to the deaths reported on that day.

Since reporting can vary significantly from day to day – irrespectively of any actual variation of deaths – it is helpful to look at a longer time span that is less affected by the daily variation in reporting. This provides a clearer picture of where the pandemic is accelerating, staying the same, or reducing.

The first map here provides figures on the number of confirmed deaths in the last two weeks. To enable comparisons across countries it is expressed per million people of the population.

And the second map shows the percentage change (growth rate) over this period: blue are all those countries in which the death count in the last two weeks was lower than in the two weeks before. In red countries the death count has increased.

What is the weekly number of confirmed deaths?

What is the weekly change (growth rate) in confirmed deaths?

Bhutan: Global deaths in comparison: how are deaths changing across the world?

In our page on COVID-19 deaths , we provide charts and maps on how the number and change in deaths compare across the world.

- How many COVID-19 vaccine doses are administered daily ?

- How many COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered in total ?

- What share of the population has received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine?

- What share of the population has completed the initial vaccination protocol ?

- Global vaccinations in comparison: which countries are vaccinating most rapidly?

Bhutan: How many COVID-19 vaccine doses are administered daily ?

How many vaccine doses are administered each day (not population adjusted)?

This chart shows the daily number of COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people in a given population . This is shown as the rolling seven-day average. Note that this is counted as a single dose, and may not equal the total number of people vaccinated, depending on the specific dose regime (e.g., people receive multiple doses).

Bhutan: How many COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered in total ?

How many vaccine doses have been administered in total (not population adjusted)?

This chart shows the total number of COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people within a given population. Note that this is counted as a single dose, and may not equal the total number of people vaccinated, depending on the specific dose regime as several available COVID vaccines require multiple doses.

Bhutan: What share of the population has received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine?

How many people have received at least one vaccine dose?

This chart shows the share of the total population that has received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. This may not equal the share with a complete initial protocol if the vaccine requires two doses. If a person receives the first dose of a 2-dose vaccine, this metric goes up by 1. If they receive the second dose, the metric stays the same.

Bhutan: What share of the population has completed the initial vaccination protocol ?

How many people have completed the initial vaccination protocol?

The following chart shows the share of the total population that has completed the initial vaccination protocol. If a person receives the first dose of a 2-dose vaccine, this metric stays the same. If they receive the second dose, the metric goes up by 1.

This data is only available for countries which report the breakdown of doses administered by first and second doses.

Bhutan: Global vaccinations in comparison: which countries are vaccinating most rapidly?

In our page on COVID-19 vaccinations, we provide maps and charts on how the number of people vaccinated compares across the world.

Testing for COVID-19

- The positive rate

- The scale of testing compared to the scale of the outbreak

- How many tests are performed each day ?

- Global testing in comparison: how is testing changing across the world?

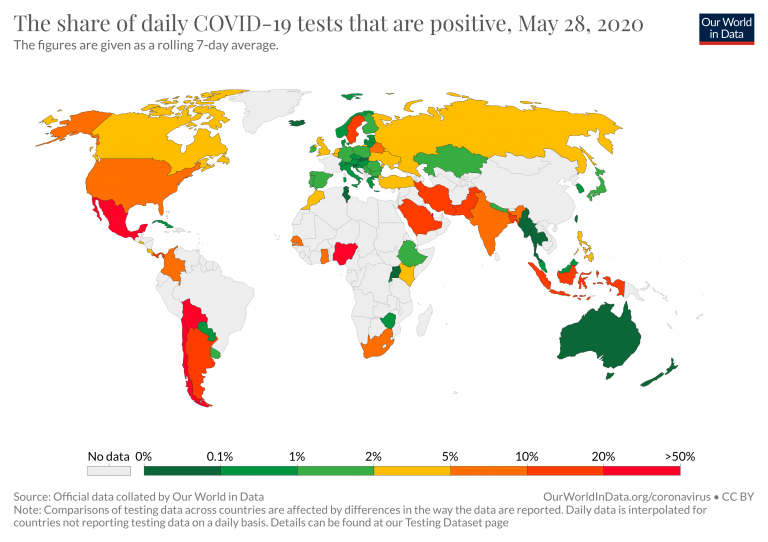

Bhutan: The positive rate

Here we show the share of reported tests returning a positive result – known as the positive rate.

The positive rate can be a good metric for how adequately countries are testing because it can indicate the level of testing relative to the size of the outbreak. To be able to properly monitor and control the spread of the virus, countries with more widespread outbreaks need to do more testing.

It can also be helpful to think of the positive rate the other way around:

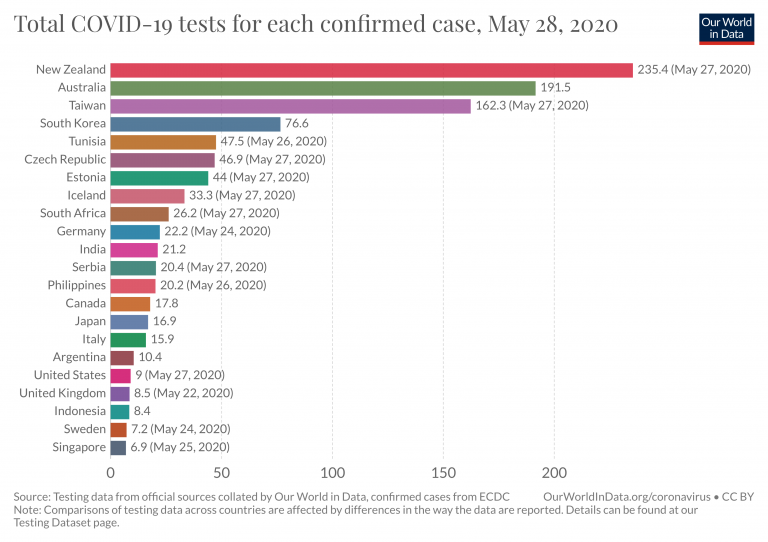

How many tests have countries done for each confirmed case in total across the outbreak?

Bhutan: The scale of testing compared to the scale of the outbreak

How do daily tests and daily new confirmed cases compare when not adjusted for population ?

This scatter chart provides another way of seeing the extent of testing relative to the scale of the outbreak in different countries.

The chart shows the daily number of tests (vertical axis) against the daily number of new confirmed cases (horizontal axis), both per million people.

Bhutan: How many tests are performed each day ?

This chart shows the number of daily tests per thousand people. Because the number of tests is often volatile from day to day, we show the figures as a seven-day rolling average.

What is counted as a test?

The number of tests does not refer to the same thing in each country – one difference is that some countries report the number of people tested, while others report the number of tests (which can be higher if the same person is tested more than once). And other countries report their testing data in a way that leaves it unclear what the test count refers to exactly.

We indicate the differences in the chart and explain them in detail in our accompanying source descriptions .

Bhutan: Global testing in comparison: how is testing changing across the world?

In our page on COVID-19 testing , we provide charts and maps on how the number and change in tests compare across the world.

Case fatality rate

- What does the data on deaths and cases tell us about the mortality risk of COVID-19?

- The case fatality rate

- Learn in more detail about the mortality risk of COVID-19

Bhutan: What does the data on deaths and cases tell us about the mortality risk of COVID-19?

To understand the risks and respond appropriately we would also want to know the mortality risk of COVID-19 – the likelihood that someone who is infected with the disease will die from it.

We look into this question in more detail on our page about the mortality risk of COVID-19 , where we explain that this requires us to know – or estimate – the number of total cases and the final number of deaths for a given infected population.

Because these are not known , we discuss what the current data on confirmed deaths and cases can and can not tell us about the risk of death. This chart shows both those metrics.

Bhutan: The case fatality rate

Related chart:.

How do the cumulative number of confirmed deaths and cases compare?

The case fatality rate is simply the ratio of the two metrics shown in the chart above.

The case fatality rate is the number of confirmed deaths divided by the number of confirmed cases.

This chart here plots the CFR calculated in just that way.

During an outbreak – and especially when the total number of cases is not known – one has to be very careful in interpreting the CFR . We wrote a detailed explainer on what can and can not be said based on current CFR figures.

Bhutan: Learn in more detail about the mortality risk of COVID-19

Learn what we know about the mortality risk of COVID-19 and explore the data used to calculate it.

Government Responses

- Government Stringency Index

To understand how governments have responded to the pandemic, we rely on data from the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT), which is published and managed by researchers at the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford.

This tracker collects publicly available information on 17 indicators of government responses, spanning containment and closure policies (such as school closures and restrictions in movement); economic policies; and health system policies (such as testing regimes).

How have countries responded to the pandemic?

Travel bans, stay-at-home restrictions, school closures – how have countries responded to the pandemic? Explore the data on all policy measures.

Bhutan: Government Stringency Index

The chart here shows how governmental response has changed over time. It shows the Government Stringency Index – a composite measure of the strictness of policy responses.

The index on any given day is calculated as the mean score of nine policy measures, each taking a value between 0 and 100. See the authors’ full description of how this index is calculated.

A higher score indicates a stricter government response (i.e. 100 = strictest response).

The OxCGRT project calculates this index using nine specific measures, including:

- school and workplace closures;

- restrictions on public gatherings;

- transport restrictions;

- and stay-at-home requirements.

You can see all of these separately on our page on policy responses . There you can also compare these responses in countries across the world.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

Bhutan and the Covid-19 pandemic

The first confirmed case of Covid-19 in Bhutan was detected on 6 March 2020. Since then, under the enlightened leadership and personal guidance of His Majesty The King, the government has taken many steps to mitigate risks and prevent the transmission and spread of the disease in the country. In fact, His Majesty The King was already aware of the risks and challenges that Covid-19 could pose to the people and country even before the detection of the first confirmed case and was pro-actively preparing response plans and strategies.

Bhutan’s preparedness, response strategies and efforts have been lauded as many steps were taken in a proactive manner despite the fact that there was no local transmission in the country. Till date, all cases are imported cases of Bhutanese returning from abroad and these are being meticulously managed in quarantine and isolation facilities by healthcare professionals.

The whole community approach as reflected in the spontaneous outpouring of support in cash, kind and volunteerism by the people of Bhutan from all walks of life is a matter of great pride. It bears testimony to our deep-rooted values and principles of compassion, unity and service to the nation in times of need. This is our strength as a nation and people. Indeed, Covid-19 has brought the country together to combat and overcome one of the greatest challenges of our times. All this has been possible due to the outstanding leadership and steadfast resolve of His Majesty The King who continues to remain at the forefront of all endeavours in these difficult times.

The swift and deliberate manner with which Bhutan acted to prepare and respond while countries in the region and beyond were overwhelmed by the pandemic is noteworthy, particularly given our constraints and limited resources. Today, His Majesty remains at the helm of all efforts and regularly travels the length and breadth of the country to take stock of our preparedness and response mechanisms and to institute new measures in keeping with the rapidly evolving situation. Among others, His Majesty has repeatedly emphasized the imperative to remain vigilant at all times and not become complacent and to be prepared for the worst-case scenario.

His Majesty’s primary concern is to protect the well-being and welfare of the people and country and towards this end, His Majesty has been actively engaged in spearheading relief measures. A National Resilience Fund has been established on Royal Command to provide relief to those who lost their livelihoods or sources of income and to help businesses affected by the pandemic to sustain their operations. Among others, people who are unemployed and have lost their source of income have been provided monthly subsistence allowances as kidu .

Similarly, deferment of loan and waiver of interest pursuant to Royal Command has come as a huge relief for the people of Bhutan. Interests on loans were initially waived for three months from April-June 2020. In addition, the waiver of interest has been extended for another three months till September 2020. This will be followed by a partial interest waiver (50%) for six additional months from October 2020 to March 2021. Vitamin pills and face masks have been distributed on Royal Command as a preventive measure to senior citizens and people with underlying conditions who are more vulnerable. Such kind of care, compassion and support from the highest level is unprecedented and we are all truly blessed and fortunate.

The people of Bhutan owe a huge debt of gratitude to His Majesty The King for his selfless service and for being the beacon of hope in these very difficult and uncertain times. Whatever we have achieved thus far in preventing the spread of the disease in Bhutan is due to the wise counsel and leadership of His Majesty The King.

Likewise, the Zhung Dratshang led by His Holiness The Je Khenpo is engaged in performing special prayers and kurims and invoking Sangaymenlha and other protecting deities to prevent spread of pandemic and keep our country safe. We also remain immensely grateful to His Holiness The Je Khenpo and the Zhung Dratshang.

The government under the leadership of the Prime Minister also deserves our deep appreciation and gratitude. In particular, we specially acknowledge the hard work being done by Health Ministry and healthcare professionals, frontline workers, armed forces, De-Suups, volunteers and all other agencies including the Covid-19 Task Force to prevent the importation and spread of Covid-19.

Going forward, what is important and imperative is for each and every citizen to be responsible by supporting the efforts of the Royal Government to prevent local/community transmission. We must diligently comply with all Notifications and Advisories issued by the government without fail and take all precautions.

As a senior citizen, I urge and appeal to all Bhutanese to be responsible and comply with health advisories such as wearing face masks, washing hands frequently and physical distancing. The Druk Trace App is an extremely important tool for contact tracing and must be used whenever visiting any public place. As the development of a vaccine remains uncertain, the age-old adage, “prevention and better than cure” must be the order of the day.

We all have a solemn responsibility, individually and collectively, to prevent the transmission and spread of Covid-19 in Bhutan. As we adapt to the “new normal” we cannot afford to become complacent, irresponsible or reckless. We must continue to work together with steadfast resolve and unity of purpose to protect our communities and our nation and to fulfill the vision of our beloved King of a strong, secure and happy nation. I am confident that we will be able to overcome this challenge by working together as members of one family.

Pelden Drukpa Gyalo!

Contributed by,

Chenkyab Dorji

Read More Stories

The state of the media.

May 4th, 2024

The annual World Press Freedom Index published by Reporters...

Protecting consumers

May 2nd, 2024

A rice importer was penalised by authorities for cheating....

Water water, not everywhere

May 1st, 2024

The recent notice from the Thimphu Thromde on the...

Contingent fees for lawyers are a gamble on justice

With the increasing complexities of legal disputes and the...

The Thrimzhung Chhenmo (The Supreme Law)

The Thrimzhung Chhenmo enshrined comprehensive substantive provisions relating to...

Are we throttling press freedom

April 27th, 2024

Third of May is observed as World Press Freedom...

Bhutan’s boxing hope dashed in debut tournament

Bhutan’s aspiration for a medal at the ongoing Asian...

2024 Bhutan Grand Prix records low turn-out

The Bhutan Archery Federation (BAF) has opened online registration...

Transport United faces Tsirang FC in inaugural 2024 BPL clash

April 30th, 2024

The highly anticipated Bhutan Premier League (BPL) 2024 is...

Bhutan’s economy to rebound to 4.9 percent in FY 2023-24: WB

The World Bank (WB) predicts that Bhutan’s economy will...

Finance ministry projects 5.68 percent growth this year

April 9th, 2024

Thukten Zangpo The finance ministry projected Bhutan’s economy to...

Non-hydro debt set to reach threshold with Nu 35 billion borrowing in FY 2024-25

April 6th, 2024

The government can borrow an extra Nu 35.88 billion...

Advertisement

- LATEST INFORMATION

- High contrast

- Work with us

- Press centre

Search UNICEF

We must all keep on protecting bhutan’s success against covid-19, unicef and who flag the risks of not following covid-19 safety measures..

From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to the successful double-dose vaccination of almost all its eligible population, Bhutan’s response to the pandemic remains exemplary. Despite being surrounded by countries that are seeing an increasing number of new cases, Bhutan’s high vaccination coverage and continued emphasis on public health safety measures makes the country one of the safest places to live in.

Yet, even as the country shifts gear to recover from the impacts of the pandemic and prepares to relax some of the restrictions, the surge in new cases and appearance of new variants spiraling around our borders is a chilling reminder that the threat of this capricious virus, which continues to upend lives in the region and across the world, is not yet over. Even after vaccination.

Being vaccinated protects one from falling seriously ill and being hospitalized for COVID-19 infection. It gives us the freedom and protection to go about our daily lives. However, there is still the risk of a vaccinated person getting infected with COVID-19 and transmitting it to another.

With the virus still evolving and with many countries struggling to vaccinate their population amid rising cases, the risks of importation and mass transmission still remain high. When complacency creeps in towards safety protocols such as wearing masks, handwashing with soap and avoiding crowds, Bhutan, despite vaccination, will remain susceptible to reinfection and worse, mass transmission. Such a situation would overwhelm our health system and our already overburdened health workers. The socio-economic impacts of mass transmission would be devastating.

Given the efforts that have gone into protecting the health of its people, the service of our front liners and health workers, the leadership of His Majesty The King and the Royal Government of Bhutan, the support of development partners and the solidarity of the people, the stakes are too high for Bhutan to let its guard down.

In the face of the current surge sweeping across the region and a third wave that is likely to hit the region, it has become more important than ever that we all continue to follow COVID-19 safety guidance and protocols. For besides the leadership of His Majesty and the efforts of the Government, it was the people’s adherence to safety protocols that contributed in keeping all of us safe.

South Asia is home to almost 2 billion people, and the continued and uncontrolled surge brings significant regional and global risks, with the potential to reverse hard-earned gains against the pandemic if the virus continues to spread and mutate unchecked. We are now in a situation where fragile health-systems, already pushed to breaking point by COVID-19, could topple across the region leading to more tragic loss of life.

As COVID-19 cases have increased, the direct impact on children in contracting the virus has also increased. More children are falling ill with COVID-19 than ever before. Fortunately, most cases in children are mild and very few serious cases required hospitalization. But with countries continuing to respond to the pandemic and as resources get diverted and services become saturated, the essential health services that children and mothers rely on, could become compromised, if not shuttered entirely. UNICEF estimates that in 2020, a quarter of a million children died due to disruptions to essential healthcare services in South Asia. We cannot let this happen again and certainly not in Bhutan.

While all countries in the region have ramped up vaccination rates over the last few weeks with increased supply of vaccines, vaccine coverage remains inadequate to halt the spread of transmission and potential virus mutations. Which is why, it has become more urgent than ever for Bhutan to ensure that its COVID-19 recovery efforts, which can be a slippery process, are as collective as its response efforts.

UNICEF, WHO and other UN agencies in Bhutan are humbled to have supported the Royal Government of Bhutan in its COVID-19 response efforts and congratulate Bhutan for achieving high vaccination coverage. We remain as committed to support the country’s recovery efforts and join the Royal Government of Bhutan’s call to the people to continue practicing the safety measures. Now more than ever, we must strive to preserve the success Bhutan has achieved against COVID-19.

We are vaccinated but we are still not safe.

By Dr Will Parks, Representative, UNICEF Bhutan & Dr Rui Paulo de Jesus, Representative, WHO Bhutan

Media contacts

About unicef.

UNICEF promotes the rights and wellbeing of every child, in everything we do. Together with our partners, we work in 190 countries and territories to translate that commitment into practical action, focusing special effort on reaching the most vulnerable and excluded children, to the benefit of all children, everywhere.

For more information about UNICEF and its work for children, visit www.unicef.org.

Follow UNICEF Bhutan on Twitter and Facebook

Related topics

More to explore.

European Union and UNICEF partner to support Digitalisation in Education, in Bhutan

From Water to the World, UNICEF celebrates 50 years of partnership with Bhutan

Protecting children from the impacts of climate change

How UNICEF’s WASH responses are mitigating the impacts of climate change on children in monastic schools.

Gelephu opens its first model inclusive ECCD centre

Challenges and Response to the Second Major Local Outbreak of COVID-19 in Bhutan

Affiliations.

- 1 Central Regional Referral Hospital, Gelephu, Bhutan.

- 2 Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital, Thimphu, Bhutan.

- 3 Kidu Mobile Medical Unit, His Majesty's People's Project, Thimphu, Bhutan.

- PMID: 33829879

- DOI: 10.1177/10105395211007607

Keywords: epidemiology; health equity; health services evaluation; health systems; inequalities in health; population health.

- Bhutan / epidemiology

- Disease Outbreaks

Bhutan's Economy Maintains Robust Growth Despite Challenges

THIMPHU, May 3, 2024 —Bhutan’s economy continues its strong recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, according to two new World Bank reports launched today.

The April 2024 Bhutan Development Update indicates that economy is showing signs of a strong recovery with an expected 4.6 percent real GDP growth in FY22/23, driven by higher growth in tourism activity, following economic contraction over two consecutive years due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Growth is expected to accelerate to 4.9 percent in FY23/24.

“ To maintain a strong and inclusive growth, Bhutan can do more to enable the business environment to attract Foreign Direct Investments and promote the private sector to create more jobs that appeal to the aspirations of its citizens”, said Abdoulaye Seck, World Bank Country Director for Bangladesh and Bhutan . “ Further, it will equally be important for the government to timely address the increasing stress on services delivery because of human resources challenges.”

Despite the relatively robust growth in recent years, downside risks to the economy persist. The fiscal deficit is expected to widen in FY23/24 to 5 percent of GDP as expenditure outpaces revenue, due to significant salary increases for public sector employees. Over the last year, there has been a significant decline in international reserves, but they have begun to stabilize as the current account deficit showed signs of narrowing in the first quarter of FY23/24, following a significant expansion in FY22/23. Risks include delayed fiscal consolidation, vulnerabilities in the financial sector, volatile international commodity prices and delays in hydropower projects.

The report includes a special section on labor market and jobs. Bhutan’s labor remains predominantly employed in the low productivity sectors. Workers face many challenges, including limited inclusion of women in meaningful employment and persistence of low-productivity agricultural employment. Employment quality outside of the public sector remains weak, leading to public sector queuing, rising unemployment among urban workers, and a record number of Bhutanese migrating abroad.

The 2023 Public Expenditure Review for Bhutan emphasizes the critical importance of efficient public spending and enhanced domestic resource mobilization to help achieve Bhutan’s long-term development goals.

Bhutan’s revenue collection remains largely driven by the hydropower sector, which contributes significantly to both tax and non-tax revenue collection. However, the contribution from the direct taxes without the hydropower sector remained stagnant. Bhutan’s capital expenditure as a share of GDP is among the highest globally, and expenditures on salary and allowances consume a significant portion of the current expenditure. While Bhutan's commitment to education and healthcare remains robust, there are opportunities to improve spending efficiency.

“ Greater contribution from direct taxes beyond the hydropower sector, coupled with a more effective tax administration system, could bolster Bhutan's ability to generate increased revenues essential for its development ,” said Hoon Sahib Soh, World Bank Practice Manager for Macroeconomics, Trade & Investment for South Asia Region.

State enterprises in Bhutan contribute significantly to budget revenues and create jobs but suffer from profitability and performance challenges. Although Bhutan has enhanced its legal and regulatory framework for state enterprise management, key policy gaps persist, including ownership and dividend policies.

“Further improvements in managing investments, corporate governance and financial reporting, can help improve performance of state enterprises and reduce fiscal risks”, said Adama Coulibaly, World Bank Resident Representative for Bhutan .

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Bhutan is known for being a happy country, but mental health is a hidden problem

Bhutan is known for being one of the happiest countries in the world, but mental health professionals say its people are suffering in silence due to cultural stigma and societal expectations of positivity.

Dr Chencho Dorji is the country's first qualified psychiatrist, and works at the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital — the only hospital in Bhutan that specialises in psychiatry.

He is also a Professor of Psychiatry at Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan.

He said even now, only six psychiatric doctors were catering for a population of over 750,000.

Although mental health care has improved since Dr Dorji first started practising in Bhutan in 1999, he said there was still a long way to go.

According to the latest Gross National Happiness report published in May 2023, 93.6 per cent of the Bhutanese population considered themselves happy.

However, Dr Dorji said limited ways to express emotion in the local dialect further compounded the issues around mental health awareness.

Cultural stigma

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr Dorji said mental health awareness increased by leaps and bounds, as the population collectively went through a distressing time.

But cultural norms and societal expectations kept a lid on open conversations and reinforced mental health as a taboo topic in many communities.

Dr Dorji said there were broad cultural beliefs that feared mental illnesses such as epilepsy were contagious, further fuelling the stigma.

"These are misconceived ideas, which we are really trying to dispel, but it's difficult, you know, something stays in the culture for generations," he said.

"A lot of the rural communities are still by and large, very superstitious — they believe in supernatural causes of illnesses, especially in mental health."

Many Bhutanese people live in mountainous areas and therefore prioritise physical health.

"Physical needs are given more importance over emotional needs of people say a lot of people would not even dare express emotions because they're not taking as as understandable," Dr Dorji said.

Societal pressure to be happy

Deki Choden, a Bhutanese counsellor studying in Western Australia, said many people were suffering due to the pressure of constant happiness.

"Mental health is very new in Bhutan, most people do not understand what depression or anxiety is," she said.

"We never realised that mental health needed this attention, because it's a very calm and peaceful country."

Ms Choden began counselling in 2016 and has since seen many more choose the career path as Bhutan works to improve awareness.

The ability to set boundaries is another major cultural difference Ms Choden found between Australia and Bhutan.

"In Bhutan, I think compassion has been so rooted in us … after coming [to Australia], I realised that I can say no, it's okay," she said.

"I'll take care of myself so that I can take care of others."

Having spent time in Australia to hone her abilities, Ms Choden said she felt inspired to apply her new-found knowledge to the Bhutanese system.

Becoming Bhutan's first psychiatrist

With no psychiatry school accessible at the time in Bhutan, Dr Dorji gained his credentials from universities in Sri Lanka, India and Australia.

He was inspired to study in the field from personal experience caring for his family.

"I had two of my siblings who had schizophrenia … so we were doing all sorts of the traditional treatments at home, but those were not working for them," he said.

"I became a doctor first in Bhutan, and then I realised that I have to take up psychiatry, at least for my own brothers' sake, because nobody else is able to treat them.

"So I became a psychiatrist, and fortunately for me, both my siblings responded to treatment to modern anti-psychotic drugs, and both of them have a relatively reasonably good life."

His exposure to other mental health care systems overseas has allowed him to set clear objectives for Bhutan's system.

Dr Dorji hopes to train more psychiatric doctors and build the number of mental health support workers in Bhutan.

Eventually, he wants to see at least one psychiatrist working at every hospital in the country.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

'it feels so empty': the forbidden kingdom of bhutan is turning into a ghost town.

- Human Interest

- Mental Health

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 04 May 2024

Clinical Studies

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on breast cancer patient pathways and outcomes in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland – a scoping review

- Lynne Lohfeld ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4711-7305 1 na1 ,

- Meenakshi Sharma 1 na1 ,

- Damien Bennett 2 ,

- Anna Gavin 1 , 2 ,

- Sinéad T. Hawkins ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3340-2917 1 , 2 ,

- Gareth Irwin 3 ,

- Helen Mitchell 2 ,

- Siobhan O’Neill 3 &

- Charlene M. McShane 1

British Journal of Cancer ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Breast cancer

- Health services

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unplanned service disruption for breast cancer diagnostic, treatment and support services. This scoping review describes these changes and their impact in the UK and the Republic of Ireland based on studies published between January 2020 and August 2023. Thirty-four of 569 papers were included. Data were extracted and results thematically organized. Findings include fewer new cases; stage shift (fewer early- and more late-stage disease); and changes to healthcare organization, breast screening and treatment. Examples are accepting fewer referrals, applying stricter referral criteria and relying more on virtual consultations and multi-disciplinary meetings. Screening service programs paused during the pandemic before enacting risk-based phased restarts with longer appointment times to accommodate reduced staffing numbers and enhanced infection-control regimes. Treatments shifted from predominantly conventional to hypofractionated radiotherapy, fewer surgical procedures and increased use of bridging endocrine therapy. The long-term impact of such changes are unknown so definitive guidelines for future emergencies are not yet available. Cancer registries, with their large sample sizes and population coverage, are well placed to monitor changes to stage and survival despite difficulties obtaining definitive staging during diagnosis because surgery and pathological assessments are delayed. Multisite longitudinal studies can also provide guidance for future disaster preparedness.

Introduction

Approximately 60,000 people are diagnosed with breast cancer annually in the United Kingdom (UK) and the Republic of Ireland (RoI) [ 1 , 2 ]. Services for screening, diagnosing, treating and follow up of patients provided through national health care services varied by country. During both the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and throughout subsequent peaks in transmission, various restrictions were implemented that limited and/or changed how breast cancer was diagnosed, treated and managed in much of the world [ 3 ], including the UK and RoI. Given the importance of early detection and treatment of cancer, there is concern over how COVID- related service delays may affect cancer patients now and in the future regarding stage at diagnosis, prognosis and mortality [ 4 ]. Because potentially life-changing decisions about cancer patients’ care have been made rapidly without the benefit of prior experience, there has been a sudden increase in studies examining possible pandemic impacts on breast cancer services and patients. To better understand the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on breast cancer diagnosis, treatment and patient outcomes in the UK and RoI, we conducted a scoping review that would examine findings from several studies conducted in these countries.

Scoping reviews aim to rapidly map key concepts in a research area that have not been studied comprehensively and identify research gaps in the existing literature [ 5 ].

The present scoping review used Arksey and O’Malley’s [ 6 ] framework, minus the last step of expert validation of findings due to resource constraints. Generally, this type of review does not include a critical appraisal of the constituent material. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was used to report the review findings [ 7 ].

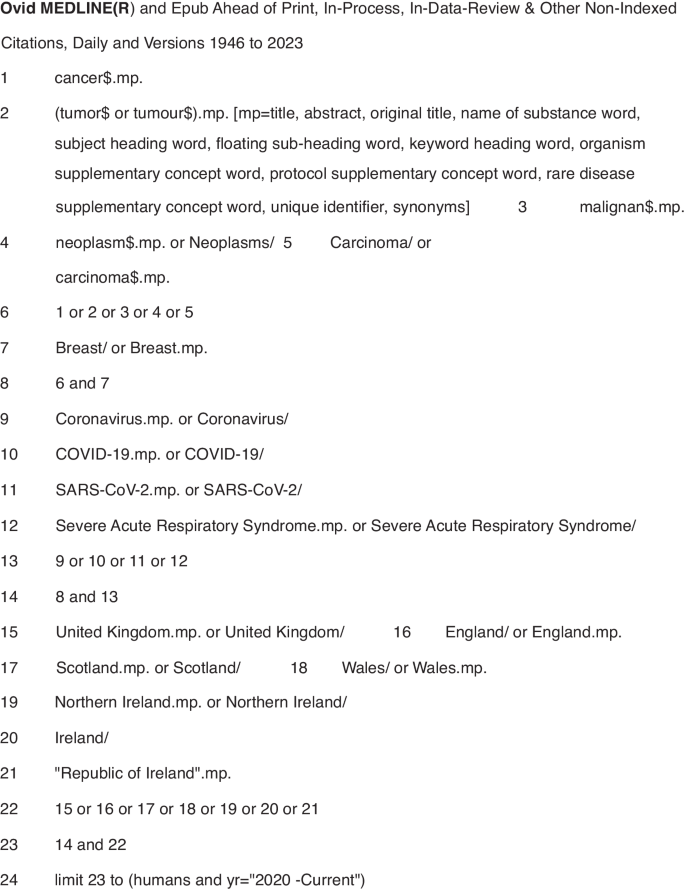

A systematic search was conducted on five electronic databases -- PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, Embase and PyschInfo -- using key words and MeSH headings for breast cancer services and outcomes in the countries of interest (Fig. 1 ). Inclusion criteria were publication in English in a peer-reviewed journal between 1 January 2020 and 31 August 2023, and reporting on primary data collected in the UK or RoI. Papers excluded from this report either did not meet the inclusion criteria or: described an intervention other than healthcare system changes or patient outcomes directly related to breast cancer; provided data from multiple locations without separately identifying results from the UK and/or the RoI; or were systematic reviews, conference abstracts, or proceedings, or unpublished (grey) literature. A hand search of the reference lists of each included paper was done.

Symbols: $ is a wildcard to expand the search term and find both British and American spellings of the same word. .mp. means multi-purpose for an Advanced search without specifying a particular field. / means the term preceding it is from the MeSH headings in MEDLINE.

Results from each electronic database were imported into the Covidence systematic review software [ 8 ], an online tool to support doing systematic reviews that automatically removes duplicate entries. Title and abstract screening was done independently by three reviewers (CM, LL, MS) who discussed differences of opinion about papers’ eligibility until reaching consensus. After removing ineligible studies, the remaining papers were downloaded and independently screened by the reviewers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any differences of opinion were resolved through discussion. The reviewers included a cancer epidemiologist, a public health professional and a medical anthropologist.

Data were extracted from the selected papers and entered into an Excel spreadsheet containing information on the bibliography (authors, title, journal, publication date), study aims and design, geographic location, and key findings (Table 1 , Supplementary Material). Results were then organised thematically to describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the organisation of breast cancer services, referrals/diagnosis and number of cases, and treatment.

A study protocol was not written and registered. The scoping review is part of a larger study on the impact of COVID-19 on breast cancer services in Northern Ireland.

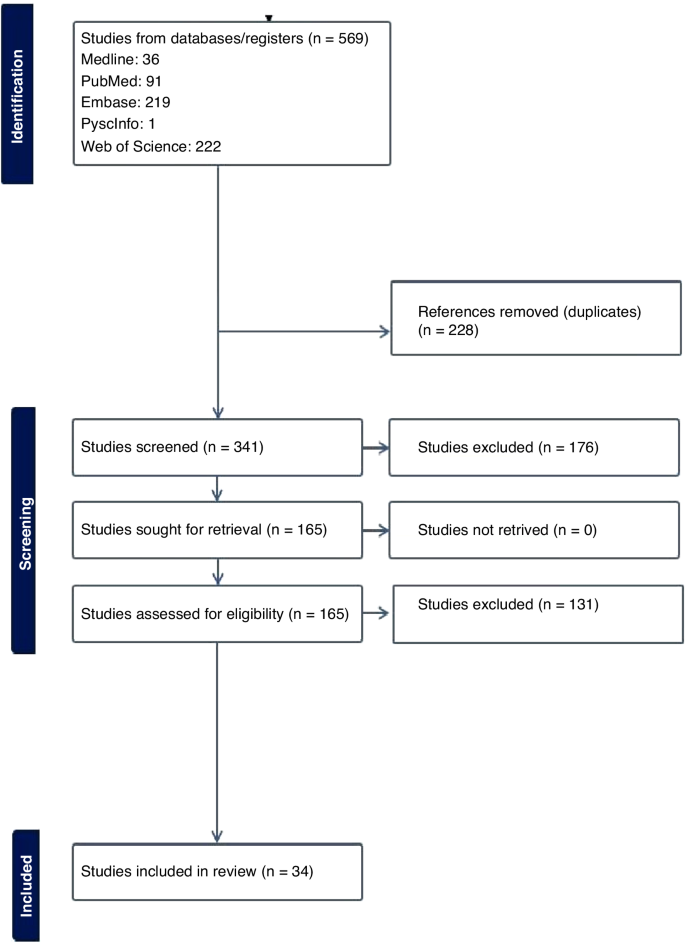

The electronic database search returned 569 studies. Following duplicate removal ( n = 228), over half (176/341, 51.6%) of the screened studies were deemed irrelevant, leaving 165 studies for full-text review. Of these studies, 129 were excluded, primarily because they were published as a conference abstract. The remaining 34 papers used in the review included 16 studies conducted in England [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ], four in Scotland [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ], three in [ 29 , 30 , 31 ] Wales, one in Northern Ireland [ 32 ], three in the UK [ 33 , 34 , 35 ], one in Ireland [ 36 ] and six that used data from multiple countries which included at least one site in the UK and/or [ 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ] RoI. No additional studies of interest were identified in the hand search of reference lists (Fig. 2 ).

Prisma flowchart.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the organisation of breast cancer services

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (March–April 2020), population-based breast cancer screening programs were paused in many jurisdictions, including the UK and RoI. There were also major changes in how members of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) met to develop treatment plans for breast cancer patients [ 11 , 37 ]. One study in an English hospital tested the acceptability of video-conferencing MDT meetings with participants attending in person or from a remote location. After overcoming minor technical difficulties (e.g. uninterrupted access to online meetings, ensuring participants had the necessary equipment to attend meetings remotely) all the participants indicated that online meetings were acceptable or their preferred mode of communication [ 11 ]. Another study surveyed breast pathologists in the UK and RoI who reported their MDTs often met in small virtual meetings [ 37 ]. Although nearly three-quarters of them indicated their workload and productivity decreased during the pandemic, 36% reported improved efficiency [ 37 ]. No study reported on the optimal balance between virtual and in-person meetings.

Three studies examined changes made to referral pathways to breast clinics or units in response to the COVID-19 pandemic [ 14 , 19 , 23 ]. One study, using data from England’s National Health Service, reported a 28% decline in referrals for suspected breast cancer during the first six months of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019 [ 14 ]. Another research group reported an even greater decline (−35%) in the number of women attending a one-stop rapid breast clinic in England during the initial lockdown (March-April 2020) compared to June-July that year [ 23 ].

A study reported on rapid adaptations made by a London-based breast cancer service in line with The Royal College of Surgeons guidelines to reduce the risk of COVID-19 [ 19 ]. Examples include providing space to maintain the recommended two metre distance between people; fewer appointments plus longer time between them to allow for thorough cleaning of surfaces; following stricter criteria for urgent referrals; and conducting routine follow-up appointments over the phone. In addition, although diagnostic imaging with ultrasound and mammogram continued to be available, all routine surveillance imaging was deferred for three months. Operations were conducted by small teams of specialists who travelled to a “cold” (free of COVID-19 cases) private hospital [ 19 ]. Virtual appointments quickly became the norm for many patients. However, as noted by one research team [ 14 ] this increased the potential for greater inequality of access to care by the elderly or people of lower socioeconomic status.

Several studies observed smaller-than-expected numbers of attendees at breast cancer screening and treatment centres [ 9 , 23 , 26 , 41 ]. This was noteworthy given the association between early detection through screening and the potential to reduce treatment needed potential to reduce treatment needed with better patient outcomes. Reasons for the downtrend in attendance ranged from centres issuing fewer invitations to ensure adequate time between appointments for cleaning equipment [ 26 ], to women declining invitations to be screened due to fears of being exposed to SARS-CoV-2 when in a healthcare facility [ 9 ].

Other investigators focused on how to effectively restart breast screening programs [ 18 , 26 ]. A Scottish study described the benefits of using a phased approach for this, giving priority to high-risk women, followed by recalling program participants, issuing new invitations to women of screening (age 50–70 years or older) or those who had missed or cancelled earlier appointments [ 26 ]. In another study [ 18 ], researchers in London investigated whether switching from sending women invitations to attend a specific appointment (“timed appointments”) to having them book their sessions (“open appointments”) would reduce the backlog of unscreened eligible women. Both invitation types were used between September 2020 and March 2021, allowing researchers to conduct a natural experiment to examine which approach had the greatest response [ 18 ]. The authors found significantly fewer women responded to the open than to the timed invitation (−7.5%) and estimated that if timed invitations were exclusively used approximately 12,000 more women would have attended screening and about 100 more women with breast cancer would have been detected [ 18 ].

The Impact of COVID-19 on referrals, diagnoses and numbers of patients with breast cancer

A major concern regarding COVID-19 is the possible effect that delaying or modifying diagnosis and treatment would have on patients, including those with symptomatic disease, and the potential for excess breast cancer deaths. An English study used national data to estimate the impact of curtailing screening during the first lockdown on predicted breast cancer deaths from 2020 to 2029. The authors estimated up to 687 additional deaths in that 10-year period [ 13 ]. Routinely collected NHS England data were used to compare referral patterns and time to first treatment for breast cancer during the pandemic (first half of 2020) compared to the same period in 2019 [ 14 ]. Results showed a 28% decrease in diagnostic services and 16% of patients receiving their first treatment. They also noted that hormonal therapy, administered in tablet form, had become a frequent alternative to surgery – the mainstay treatment for breast cancer before the pandemic [ 14 ].