Clinical Presentation of COVID19 in Dementia Patients

Affiliation.

- 1 Angelo Bianchetti, MD. Department Medicine and Rehabilitation, Istituto Clinico S.Anna Hospital, via del Franzone 31, 25122 Brescia, Italy; e-mail: [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2914-0627, phone: +390303197409 - fax: +390303198687.

- PMID: 32510106

- PMCID: PMC7227170

- DOI: 10.1007/s12603-020-1389-1

Objective: No studies analyzing the role of dementia as a risk factor for mortality in patients affected by COVID-19. We assessed the prevalence, clinical presentation and outcomes of dementia among subjects hospitalized for COVID19 infection.

Design: Retrospective study.

Setting: COVID wards in Acute Hospital in Brescia province, Northern Italy.

Participants: We used data from 627 subjects admitted to Acute Medical wards with COVID 19 pneumonia.

Measurements: Clinical records of each patients admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of COVID19 infection were retrospectively analyzed. Diagnosis of dementia, modalities of onset of the COVID-19 infection, symptoms of presentation at the hospital and outcomes were recorded.

Results: Dementia was diagnosed in 82 patients (13.1%). The mortality rate was 62.2% (51/82) among patients affected by dementia compared to 26.2% (143/545) in subjects without dementia (p<0.001, Chi-Squared test). In a logistic regression model age, and the diagnosis of dementia resulted independently associated with a higher mortality, and patients diagnosed with dementia presented an OR of 1.84 (95% CI: 1.09-3.13, p<0.05). Among patients diagnosed with dementia the most frequent symptoms of onset were delirium, especially in the hypoactive form, and worsening of the functional status.

Conclusion: The diagnosis of dementia, especially in the most advanced stages, represents an important risk factor for mortality in COVID-19 patients. The clinical presentation of COVID-19 in subjects with dementia is atypical, reducing early recognition of symptoms and hospitalization.

Keywords: COVID19 infection; dementia; mortality risk.

- Aged, 80 and over

- Betacoronavirus*

- Coronavirus Infections / complications*

- Dementia / complications*

- Dementia / epidemiology

- Italy / epidemiology

- Logistic Models

- Middle Aged

- Pneumonia, Viral / complications*

- Retrospective Studies

- Risk Factors

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Year in Review

- Published: 06 January 2021

NEUROLOGY AND COVID-19 IN 2020

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia

- Katya Numbers 1 &

- Henry Brodaty ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9487-6617 1 , 2

Nature Reviews Neurology volume 17 , pages 69–70 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

26k Accesses

124 Citations

122 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Alzheimer's disease

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unique risks to people with Alzheimer disease and dementia. Research from 2020 has shown that these people have a relatively high risk of contracting severe COVID-19, and are also at risk of neuropsychiatric disturbances as a result of lockdown measures and social isolation.

Key advances

People with dementia are at high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection because cognitive symptoms cause difficulty with following safeguarding procedures and living arrangements in care homes facilitate viral spread 1 .

Once infected, older adults with dementia are more likely to experience severe virus-related outcomes, including death, than are people without dementia 4 .

A homozygous APOE ε4 genotype is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for COVID-19 (ref. 8 ), possibly owing to exacerbated inflammation and cytokine production that leads to a cytokine storm.

Older adults with dementia, especially those in care homes, are at high risk of worsening psychiatric symptoms and severe behavioural disturbances as a result of social isolation during the pandemic 3 .

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a unique impact on people with Alzheimer disease (AD) and other dementias. As research into this impact has accumulated throughout 2020, a clear picture has emerged that this population is particularly susceptible not just to SARS-CoV-2 infection and its effects, but also to the negative effects of the measures taken worldwide to control the spread of the virus.

Large-scale clinical data suggest that, even when old age and medical comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes are taken into account, people with dementia are more likely to contract COVID-19 than people without dementia. Several reasons underlie the increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in people with dementia, which are described in an important overview published in August 1 . First, cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric symptoms make it challenging for individuals with dementia to understand and comply with safeguarding procedures, such as wearing masks and maintaining appropriate physical distancing 1 . Ignoring or forgetting warnings and an inability to follow self-quarantine measures increase the risk of infection.

people with dementia are more likely to contract COVID-19 than people without dementia

In addition, most people who live in institutional settings (nursing or care homes), where rates of infection are disproportionately high worldwide 2 , have dementia. Such living arrangements facilitate rapid transmission of the virus as residents and staff congregate and live within close proximity. Physical distancing is not feasible for residents who are dependent on staff to assist with basic activities of daily living (for example, toileting, bathing and eating). Furthermore, dementia-associated neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as agitation, intrusiveness or wandering, can also undermine safety protocols and increase the risk of infection among staff and other residents 1 . Accordingly, nursing and care homes have implemented increasingly severe lockdown measures, which further exacerbate pre-existing neuropsychiatric symptoms among residents with dementia 3 .

As well as being at increased risk of contracting COVID-19, older adults with dementia are also more likely to have more severe disease consequences than those without dementia 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 . A large community cohort study conducted in the UK has shown that the risk of serious COVID-19 (defined as a requirement for hospitalization) was threefold higher for individuals with a diagnosis of dementia than for those without dementia 4 . The risk factors for dementia — age, obesity, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and diabetes mellitus — are also risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection 6 and for severe COVID-19. However, some evidence suggests that more specific mechanistic aspects of dementia and pre-existing brain pathology can increase the risk of neurological complications from COVID-19 (ref. 8 ). In particular, a study of the UK Biobank cohort showed that the risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization was more than twofold higher among individuals who were homozygous for APOE ε4 than among individuals with the most common APOE ε3/ε3 genotype 8 .

One possible mechanistic explanation for this association is that increased blood–brain barrier permeability associated with APOE ε4 leads to more extensive CNS inflammation in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection — in line with this hypothesis, APOE ε4 is known to exacerbate microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and subsequent neurodegeneration 9 . In addition, APOE ε4 is associated with increased cytokine production in response to inflammatory stimuli, which could intensify the already aggressive inflammatory response associated with COVID-19, resulting in a so-called cytokine storm 10 . The cytokine storm has been directly associated with lung injury, multi-organ failure and severe COVID-19 outcomes, including death 10 .

The restrictions that have been implemented in many countries to control the pandemic have also had important neuropsychiatric consequences for patients with dementia. In the population as a whole, forced social isolation has led to an increase in reported psychiatric symptoms (for example, stress, anxiety and depression) for all individuals; this relationship seems to be moderated by the loneliness associated with prolonged periods of lockdown 1 , 3 , 9 . In nursing and care homes, older adults are likely to experience additional distress owing to the absence of relatives who would normally visit them, as well as strict limitations on social activities and interactions with fellow residents. Data collected during the first half of 2020 show that such social isolation during the pandemic is associated with manifestation and/or exacerbation of neuropsychiatric symptoms even in cognitively healthy older adults 1 , 9 .

Several studies — summarized in a review published in October 3 — have shown that, in older adults with dementia, psychiatric symptoms caused by social isolation are linked to more severe neuropsychiatric and behavioural disturbances 3 . Social isolation combined with confusion in care home residents with dementia might result in even greater agitation, boredom and loneliness than in residents without dementia, thereby leading to more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms. These neuropsychiatric symptoms seem to arise directly from social restrictions, as longer lockdown periods result in more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms 3 . Furthermore, some experts have suggested that behavioural complications that result from prolonged periods of lockdown in older adults with dementia could become chronic 3 . Some consequences of neuropsychiatric disturbances, such as increased aggression and agitation, can be particularly challenging for carers and care home staff to manage.

longer lockdown periods result in more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms

In summary, the evidence to date indicates that older adults with dementia have a high risk of contracting COVID-19 and, once infected, have a high risk of disease-related morbidity and mortality. This population is often the first to go into, and the last to come out of, strict and prolonged periods of isolation to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection, yet is at extremely high risk of worsening neuropsychiatric symptoms and severe behavioural disturbance as a direct result. Therefore, during and after the pandemic, implementation of caregiver support and the presence of skilled nursing home staff are essential to maintain social interaction and to provide extra support to older adults with dementia.

Mok, V. C. et al. Tackling challenges in care of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias amid the COVID-19 pandemic, now and in the future. Alzheimers Dement. 16 , 1571–1581 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Comas-Herrera, A. et al. Mortality associated with COVID-19 outbreaks in care homes: early international evidence. LTCCOVID https://ltccovid.org/2020/04/12/mortality-associated-with-covid-19-outbreaks-in-care-homes-early-international-evidence/ (2020).

Manca, R., De Marco, M. & Venneri, A. The impact of COVID-19 infection and enforced prolonged social isolation on neuropsychiatric symptoms in older adults with and without dementia: a review. Front. Psychiatry 11 , 1086 (2020).

Atkins, J. L. et al. Preexisting comorbidities predicting severe COVID-19 in older adults in the UK Biobank community cohort. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75 , 2224–2230 (2020).

Onder, G., Rezza, G. & Brusaferro, S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 323 , 1775–1776 (2020).

CAS Google Scholar

Williamson, E. J. et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584 , 430–436 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Zhou, F. et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395 , 1054–1062 (2020).

Kuo, C.-L. et al. APOE e4 genotype predicts severe COVID-19 in the UK Biobank community cohort. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75 , 2231–2232 (2020).

Brown, E. E., Kumar, S., Rajji, T. K., Pollock, B. G. & Mulsant, B. H. Anticipating and Mitigating the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28 , 712–721 (2020).

Ragab, D., Salah Eldin, H., Taeimah, M., Khattab, R. & Salem, R. The COVID-19 cytokine storm; what we know so far. Front. Immunol. 11 , 1446 (2020).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

CHeBA (Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing), School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Katya Numbers & Henry Brodaty

Dementia Centre for Research Collaboration, School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Henry Brodaty

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Henry Brodaty .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Numbers, K., Brodaty, H. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 17 , 69–70 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-020-00450-z

Download citation

Published : 06 January 2021

Issue Date : February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-020-00450-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on mortality and loss to follow-up among patients with dementia receiving anti-dementia medications.

- Hyuk Sung Kwon

- Wonjae Sung

Scientific Reports (2024)

The Impact of the Pandemic on Health and Quality of Life of Informal Caregivers of Older People: Results from a Cross-National European Survey in an Age-Related Perspective

- Marco Socci

- Mirko Di Rosa

- Sara Santini

Applied Research in Quality of Life (2024)

Impact of COVID-19 on the Residential Aged Care Workforce, and Workers From Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds: A Rapid Literature Review

- Samantha Battams

- Angelita Martini

Ageing International (2024)

Factors influencing mobility in community-dwelling older adults during the early COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study

BMC Public Health (2023)

Emotions, action strategies and expectations of health professionals and people with dementia regarding COVID-19 in different care settings in Switzerland: a mixed methods study

- Steffen Heinrich

- Inga Weissenfels

- Adelheid Zeller

BMC Geriatrics (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Clinical Presentation of COVID19 in Dementia Patients

- Published: 15 May 2020

- Volume 24 , pages 560–562, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Angelo Bianchetti 1 , 4 na1 ,

- R. Rozzini 2 , 4 na1 ,

- F. Guerini 1 , 4 na1 ,

- S. Boffelli 2 , 4 na1 ,

- P. Ranieri 1 , 4 na1 ,

- G. Minelli 1 , 4 na1 ,

- L. Bianchetti 3 , 4 na1 &

- M. Trabucchi 4 na1

15k Accesses

214 Citations

149 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

No studies analyzing the role of dementia as a risk factor for mortality in patients affected by COVID-19. We assessed the prevalence, clinical presentation and outcomes of dementia among subjects hospitalized for COVID19 infection.

Retrospective study.

COVID wards in Acute Hospital in Brescia province, Northern Italy.

Participants

We used data from 627 subjects admitted to Acute Medical wards with COVID 19 pneumonia.

Measurements

Clinical records of each patients admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of COVID19 infection were retrospectively analyzed. Diagnosis of dementia, modalities of onset of the COVID-19 infection, symptoms of presentation at the hospital and outcomes were recorded.

Dementia was diagnosed in 82 patients (13.1%). The mortality rate was 62.2% (51/82) among patients affected by dementia compared to 26.2% (143/545) in subjects without dementia (p<0.001, Chi-Squared test). In a logistic regression model age, and the diagnosis of dementia resulted independently associated with a higher mortality, and patients diagnosed with dementia presented an OR of 1.84 (95% CI: 1.09–3.13, p<0.05). Among patients diagnosed with dementia the most frequent symptoms of onset were delirium, especially in the hypoactive form, and worsening of the functional status.

The diagnosis of dementia, especially in the most advanced stages, represents an important risk factor for mortality in COVID-19 patients. The clinical presentation of COVID-19 in subjects with dementia is atypical, reducing early recognition of symptoms and hospitalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

COVID-19 in adults with dementia: clinical features and risk factors of mortality—a clinical cohort study on 125 patients

Delirium in covid-19: epidemiology and clinical correlations in a large group of patients admitted to an academic hospital.

COVID-19 mortality risk factors in older people in a long-term care center

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Italy, SARS-CoV-2 outbreak was catastrophic with 135,586 confirmed cases and 17,127 deaths at April, 8th ( 1 ). In clinical series of patients who died of COVID-19 comorbidities (especially hypertension, cardiac ischemic disease, diabetes and obesity) were identified as significant risk factors for mortality, while dementia was described as a comorbid condition in only 6.8% of COVID-19 patients ( 2 ).

Although dementia is known to be an important mortality risk factor among older people, so far there are no studies analyzing the role of dementia as a risk factor for mortality in patients affected by COVID-19 ( 3 , 4 ).

In the Province of Brescia, an administrative district in eastern Lombardy home to 1.2 million people, between February 22nd and April 8th, 9,900 cases of Covid-19 have been diagnosed and 1,800 deaths have been reported. About 53% (2265 out of 4200) of hospital beds have been dedicated to treat patients affected by Covid-19 pneumonia. Specific units were created to cater to these patients: acute medical units, named COVID Wards, and intensive care units, with the last accounting fort the 8.5% of all the beds dedicated to COVID-19 patients.

Methods and study population

During this period, 627 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 pneumonia were admitted to our hospitals. All patients admitted to COVID Wards were positive to RT-PCR for SARS-Cov-2 conducted on a nasopharyngeal specimen and presented respiratory failure. Each patient underwent a thorough medical evaluation and, if over 65, a geriatric multi-dimensional assessment, comprehensive of evaluation of cognitive and functional status and presence of delirium.

Dementia was diagosed according to clinical history and results of the cognitive assessment. The modalities of onset of the COVID-19 infection, the symptoms of presentation at the hospital emergency department and the outcomes were recorded.

Dementia was diagnosed in 82 patients (13.1%). The mean age of patients diagnosed with dementia was 82.6 (SD 5.3; IQR 80–86), versus 68.9 (SD 12.7; IQR 60–68) in patients not affected by dementia (p<0.001; Student’s t test). Females were 47 (57.3%) among patients with dementia and 288 (52.8%) among patients not diagnosed with dementia, respectively.

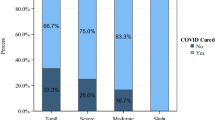

The mortality rate was 62.2% (51/82) among patients affected by dementia compared to 26.2% (143/545) in subjects without dementia (p<0.001, Chi-Squared test). (Table 1 )

The Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) ( 5 ) was used to determine the severity of dementia: 36 patients (43.4%) were classified in stage 1, 15 (18.3%) in stage 2 and 31 (37.8%) in stage 3. The Mortality rates were, respectively, 41.7%, 66.7%, and 83.9% (p<0.001, one-way ANOVA). (table 2 )

To assess if the diagnosis of dementia was associated with a worse outcome regardless of age and sex, we built a logistic regression model. According to this model age, and the diagnosis of dementia resulted independently associated with a higher mortality. For every increased year of age, the Odds Ratio (OR) for mortality was 1.09 (95% CI: 1.07–1.12, p<0.001), and patients diagnosed with dementia presented an OR of 1.84 (95% CI: 1.09–3.13, p<0.05). According to this model sex was not associated with a change in mortality risk. (Table 3 )

As shown in table 4 , among patients diagnosed with dementia the most frequent symptoms of onset were delirium (67%, especially in the hypoactive form, 50%) and worsening of the functional status. The classic symptoms of COVID-19 infection were less frequent: only 47% of patients had fever, 44% dyspnea and 14% cough.

Conclusions

Caring for patients with dementia during the current pandemic is a complex task, involving the management of patients in different settings. Some patients need to be treated at home, often with caregivers burdened by isolation due to lockdown measures and by limitation of home services. Other patients are cared in nursing homes, which often lack adequate and trained staffs and access to personal protective equipment. Hospital patient’s management has been difficult due to the scarce collaboration offered by the patient and difficulties in communication, immobility, and limited availability of trained staff members ( 6 ). There are also ethical concerns regarding hospitalization of patients with dementia due to resource constraints during the current pandemic ( 7 ).

To our knowledge, the proportion of subjects with dementia among patients admitted to an acute hospital for COVID-19 has never been evaluated. The prevalence of demented patient found in the present study (13.1%) is lower than the previous estimates of the prevalence of dementia in hospital, which vary from 15% to 42% ( 7 ). According to our data, the diagnosis of dementia, especially in the most advanced stages, represents an important risk factor for mortality in COVID-19 patients. The clinical presentation of COVID-19 in subjects with dementia is atypical, reducing early recognition of symptoms and hospitalization. We suggest that the onset of hypoactive delirium and worsening functional status in people with dementia may be considered a sign of possible COVID-19 infection during this epidemic. Early recognition of COVID-19 in demented people can help provide timely treatment and adequate isolation. Hospitals should develop integrated care models, create Special Care Geriatric COVID units and promote guidelines to ensure the better possible treatment for frail older persons.

Word Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report - 79. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200408-sitrep-79-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=4796bl43_4

Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. Published online March 23, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4683

Morandi A, Di Santo SG, Zambón A et al , Italian Study Group on Delirium (ISGoD). Delirium, Dementia, and In-Hospital Mortality: The Results From the Italian Delirium Day 2016, A National Multicenter Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci;2019;74:910–916.

Article Google Scholar

D’Adamo H, Yoshikawa T, Ouslander JG. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Geriatrics and Long-term Care: The ABCDs of COVID-19. JAGS 2020;doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16445

Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. The British Journal of Psychiatry; 1982;140, 566–572.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Wang H, Li T, Barbarino P, Gauthier S, Brodaty H, Molinuevo JL, Xie H, Sun Y, Yu E, Tang Y, Weidner W, Yu X. Dementia care during COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1190–1191. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30755-8 . Epub 2020 Mar 30.

Aprahamian I, Cesari M. Geriatric Syndromes and SARS-COV-2: More than Just Being Old [published online ahead of print,]. J Frailty Aging. 2020;1–3. doi: https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2020.17

Jackson TA, Gladman JR, Harwood RH et al. Challenges and opportunities in understanding dementia and delirium in the acute hospital. PLoS Med:e 2017;1002247.

Download references

Acknowledgement

Anita Chizzoli, MD; Marzia Cristo, MD; Silvia Comini, MD; Assunta Di Stasio, MD and Antonella Ricci, MD for the support in clinical evaluation of patients.

Funding: No funding.

Author information

All the authors contributed equally to the drafting of this manuscript.

Authors and Affiliations

Department Medicine and Rehabilitation, Istituto Clinico S.Anna Hospital, via del Franzone 31, 25122, Brescia, Italy

Angelo Bianchetti, F. Guerini, P. Ranieri & G. Minelli

Geriatric Department, Fondazione Poliambulanza Istituto Ospedaliero Hospital, Brescia, Italy

R. Rozzini & S. Boffelli

Geriatric Reahabilitation Unit, Anni Azzurri, Rezzato, Brescia, Italy

L. Bianchetti

Italian Association of Psychogeriatrics, Rome, Italy

Angelo Bianchetti, R. Rozzini, F. Guerini, S. Boffelli, P. Ranieri, G. Minelli, L. Bianchetti & M. Trabucchi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Angelo Bianchetti .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval: This is a review study; the protocol was approved by the institutional committee.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Bianchetti, A., Rozzini, R., Guerini, F. et al. Clinical Presentation of COVID19 in Dementia Patients. J Nutr Health Aging 24 , 560–562 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1389-1

Download citation

Received : 25 April 2020

Accepted : 11 May 2020

Published : 15 May 2020

Issue Date : June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1389-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- COVID19 infection

- mortality risk

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Covid-19 and lack of...

Impact of COVID-19 on people living with dementia: emerging international evidence

Rapid response to:

Covid-19 and lack of linked datasets for care homes

Read our latest coverage of the coronavirus pandemic.

- Related content

- Article metrics

- Rapid responses

Rapid Response:

Dear Editor,

High rates of COVID-19 related deaths in people living with dementia have been reported since the pandemic started. This is likely associated with the fact that many COVID-19 deaths correspond to care home residents, most of whom have dementia. People with dementia may be at increased risk of developing more severe COVID-19 infection (1) and die from it (2) according to studies conducted on hospital cohorts. Furthermore, carriers of ApoEε4/ε4 genotype, the strongest genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, are more likely to develop complications from COVID-19 (3). Although it remains unclear whether dementia is directly associated with the severity of COVID-19 or influenced by other factors (e.g. older age and associated comorbidity), growing evidence indicates that this population is extremely vulnerable to the effects of the virus. Not only that, but up to 5.7% of patients with severe presentation of COVID-19 have stroke, which can precipitate cognitive decline in people already living with progressive cognitive difficulties (4). To prevent infection, people with dementia have gone through confinement and isolation, both in the community and in care homes. These measures, also involving the removal of essential sources of support, care and meaningful contact with family members (including spouses and main partners in care), may have long-lasting deleterious effects. A survey conducted among patients attending an Italian memory clinic showed that up to 31% of people with dementia had experienced significant cognitive deterioration during the first month of lockdown and 54% a worsening of agitation, apathy and depression (5).

Mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on people with dementia should be a public health priority. The measures required include ensuring access to enough PPE and training on infection prevention and control for care workers, comprehensive testing policies, access to quarantine and step-down facilities, and implementation of guidance on compassionate isolation and person-centred care to lessen the psychological and cognitive detrimental effect of confinement. In many parts of the world, the rates of infection are beginning to decrease. We now have the opportunity to learn from these first experiences with COVID-19 and be better prepared so that, in future waves, people living with dementia are not left behind.

1. Atkins JL, Masoli JAH, Delgado J, et al. Preexisting comorbidities predicting severe COVID-19 in older adults in the UK Biobank community cohort. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.20092700 2. Bianchetti A, Rozzini R, Guerini F., et al. Clinical presentation of COVID-19 in dementia patients. J Nutr Health Aging 24, 560-562 doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1389-1 3. Kuo CL, Pilling LC, Atkin JL, et al. APOE e4 Genotype predicts severe COVID-19 in the UK Biobank community cohort. The journals of Gerontology: series A, glaa131: https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa131 4. Mao L, Huijuna J, Wang M et al., Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683-690. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127 5. Canevelli m, Valleta M, Toccaceli M., et al. Facing dementia during the covid-19 outbreak. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Jun 9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16644.

Funding: ASG is supported by the ESRC/NIHR Dementia Research Initiative (ES/S010467/1). ACH is supported by the UK Research and Innovation’s Global Challenges Research Fund (ES/P010938/1).

Competing interests: GL and ACH report no competing interests. ASG reports fees from MedAvante Pro-Phase. All reported financial activities are unrelated to this correspondence.

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (44,074,510 articles, preprints and more)

- Free full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

Clinical Presentation of COVID19 in Dementia Patients.

Author information, affiliations.

- Bianchetti A 1

ORCIDs linked to this article

- BIANCHETTI A | 0000-0002-2914-0627

The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging , 01 Jan 2020 , 24(6): 560-562 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1389-1 PMID: 32510106 PMCID: PMC7227170

Abstract

Participants, measurements, free full text .

Clinical Presentation of COVID19 in Dementia Patients

Angelo bianchetti.

1 Department Medicine and Rehabilitation, Istituto Clinico S.Anna Hospital, via del Franzone 31, 25122 Brescia, Italy

4 Italian Association of Psychogeriatrics, Rome, Italy

2 Geriatric Department, Fondazione Poliambulanza Istituto Ospedaliero Hospital, Brescia, Italy

S. Boffelli

L. bianchetti.

3 Geriatric Reahabilitation Unit, Anni Azzurri, Rezzato, Brescia, Italy

M. Trabucchi

No studies analyzing the role of dementia as a risk factor for mortality in patients affected by COVID-19. We assessed the prevalence, clinical presentation and outcomes of dementia among subjects hospitalized for COVID19 infection.

Retrospective study.

COVID wards in Acute Hospital in Brescia province, Northern Italy.

We used data from 627 subjects admitted to Acute Medical wards with COVID 19 pneumonia.

Clinical records of each patients admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of COVID19 infection were retrospectively analyzed. Diagnosis of dementia, modalities of onset of the COVID-19 infection, symptoms of presentation at the hospital and outcomes were recorded.

Dementia was diagnosed in 82 patients (13.1%). The mortality rate was 62.2% (51/82) among patients affected by dementia compared to 26.2% (143/545) in subjects without dementia (p<0.001, Chi-Squared test). In a logistic regression model age, and the diagnosis of dementia resulted independently associated with a higher mortality, and patients diagnosed with dementia presented an OR of 1.84 (95% CI: 1.09–3.13, p<0.05). Among patients diagnosed with dementia the most frequent symptoms of onset were delirium, especially in the hypoactive form, and worsening of the functional status.

The diagnosis of dementia, especially in the most advanced stages, represents an important risk factor for mortality in COVID-19 patients. The clinical presentation of COVID-19 in subjects with dementia is atypical, reducing early recognition of symptoms and hospitalization.

Introduction

In Italy, SARS-CoV-2 outbreak was catastrophic with 135,586 confirmed cases and 17,127 deaths at April, 8th ( 1 ). In clinical series of patients who died of COVID-19 comorbidities (especially hypertension, cardiac ischemic disease, diabetes and obesity) were identified as significant risk factors for mortality, while dementia was described as a comorbid condition in only 6.8% of COVID-19 patients ( 2 ).

Although dementia is known to be an important mortality risk factor among older people, so far there are no studies analyzing the role of dementia as a risk factor for mortality in patients affected by COVID-19 ( 3 , 4 ).

In the Province of Brescia, an administrative district in eastern Lombardy home to 1.2 million people, between February 22nd and April 8th, 9,900 cases of Covid-19 have been diagnosed and 1,800 deaths have been reported. About 53% (2265 out of 4200) of hospital beds have been dedicated to treat patients affected by Covid-19 pneumonia. Specific units were created to cater to these patients: acute medical units, named COVID Wards, and intensive care units, with the last accounting fort the 8.5% of all the beds dedicated to COVID-19 patients.

Methods and study population

During this period, 627 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 pneumonia were admitted to our hospitals. All patients admitted to COVID Wards were positive to RT-PCR for SARS-Cov-2 conducted on a nasopharyngeal specimen and presented respiratory failure. Each patient underwent a thorough medical evaluation and, if over 65, a geriatric multi-dimensional assessment, comprehensive of evaluation of cognitive and functional status and presence of delirium.

Dementia was diagosed according to clinical history and results of the cognitive assessment. The modalities of onset of the COVID-19 infection, the symptoms of presentation at the hospital emergency department and the outcomes were recorded.

Dementia was diagnosed in 82 patients (13.1%). The mean age of patients diagnosed with dementia was 82.6 (SD 5.3; IQR 80–86), versus 68.9 (SD 12.7; IQR 60–68) in patients not affected by dementia (p<0.001; Student’s t test). Females were 47 (57.3%) among patients with dementia and 288 (52.8%) among patients not diagnosed with dementia, respectively.

The mortality rate was 62.2% (51/82) among patients affected by dementia compared to 26.2% (143/545) in subjects without dementia (p<0.001, Chi-Squared test). (Table (Table1 1 )

Characteristics of 627 patients consecutively hospitalized for COVID19 pneumonia in two Italian hospitals according to the diagnosis of dementia

* Pearson’s chi-squared test; ** Student’s t-test

The Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) ( 5 ) was used to determine the severity of dementia: 36 patients (43.4%) were classified in stage 1, 15 (18.3%) in stage 2 and 31 (37.8%) in stage 3. The Mortality rates were, respectively, 41.7%, 66.7%, and 83.9% (p<0.001, one-way ANOVA). (table (table2 2 )

Characteristics of 627 patients consecutively hospitalized for COVID19 pneumonia in two Italian hospitals according to CDR classification

* one-way ANOVA

To assess if the diagnosis of dementia was associated with a worse outcome regardless of age and sex, we built a logistic regression model. According to this model age, and the diagnosis of dementia resulted independently associated with a higher mortality. For every increased year of age, the Odds Ratio (OR) for mortality was 1.09 (95% CI: 1.07–1.12, p<0.001), and patients diagnosed with dementia presented an OR of 1.84 (95% CI: 1.09–3.13, p<0.05). According to this model sex was not associated with a change in mortality risk. (Table (Table3 3 )

Binary Logistic Regression Model for mortality by Age, Sex and Dementia

* Wald Test for Analysis of Variance

As shown in table table4, 4 , among patients diagnosed with dementia the most frequent symptoms of onset were delirium (67%, especially in the hypoactive form, 50%) and worsening of the functional status. The classic symptoms of COVID-19 infection were less frequent: only 47% of patients had fever, 44% dyspnea and 14% cough.

Symptoms at ER admission among 82 dementia patients consecutively hospitalized for COVID19 pneumonia in two Italian hospitals

Conclusions

Caring for patients with dementia during the current pandemic is a complex task, involving the management of patients in different settings. Some patients need to be treated at home, often with caregivers burdened by isolation due to lockdown measures and by limitation of home services. Other patients are cared in nursing homes, which often lack adequate and trained staffs and access to personal protective equipment. Hospital patient’s management has been difficult due to the scarce collaboration offered by the patient and difficulties in communication, immobility, and limited availability of trained staff members ( 6 ). There are also ethical concerns regarding hospitalization of patients with dementia due to resource constraints during the current pandemic ( 7 ).

To our knowledge, the proportion of subjects with dementia among patients admitted to an acute hospital for COVID-19 has never been evaluated. The prevalence of demented patient found in the present study (13.1%) is lower than the previous estimates of the prevalence of dementia in hospital, which vary from 15% to 42% ( 7 ). According to our data, the diagnosis of dementia, especially in the most advanced stages, represents an important risk factor for mortality in COVID-19 patients. The clinical presentation of COVID-19 in subjects with dementia is atypical, reducing early recognition of symptoms and hospitalization. We suggest that the onset of hypoactive delirium and worsening functional status in people with dementia may be considered a sign of possible COVID-19 infection during this epidemic. Early recognition of COVID-19 in demented people can help provide timely treatment and adequate isolation. Hospitals should develop integrated care models, create Special Care Geriatric COVID units and promote guidelines to ensure the better possible treatment for frail older persons.

Acknowledgement

Anita Chizzoli, MD; Marzia Cristo, MD; Silvia Comini, MD; Assunta Di Stasio, MD and Antonella Ricci, MD for the support in clinical evaluation of patients.

Funding: No funding.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval: This is a review study; the protocol was approved by the institutional committee.

All the authors contributed equally to the drafting of this manuscript.

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1389-1

Citations & impact

Impact metrics, citations of article over time, smart citations by scite.ai smart citations by scite.ai include citation statements extracted from the full text of the citing article. the number of the statements may be higher than the number of citations provided by europepmc if one paper cites another multiple times or lower if scite has not yet processed some of the citing articles. explore citation contexts and check if this article has been supported or disputed. https://scite.ai/reports/10.1007/s12603-020-1389-1, article citations, a longitudinal cohort study on the use of health and care services by older adults living at home with/without dementia before and during the covid-19 pandemic: the hunt study..

Ibsen TL , Strand BH , Bergh S , Livingston G , Lurås H , Mamelund SE , Voshaar RO , Rokstad AMM , Thingstad P , Gerritsen D , Selbæk G

BMC Health Serv Res , 24(1):485, 19 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38641570 | PMCID: PMC11027287

COVID-19 and Comorbidities: What Has Been Unveiled by Metabolomics?

Camelo ALM , Zamora Obando HR , Rocha I , Dias AC , Mesquita AS , Simionato AVC

Metabolites , 14(4):195, 30 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38668323 | PMCID: PMC11051775

COVID-19 and Alzheimer's disease: Impact of lockdown and other restrictive measures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nawaz AD , Haider MZ , Akhtar S

Biomol Biomed , 24(2):219-229, 11 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38078809 | PMCID: PMC10950341

New score to predict COVID-19 progression in vaccine and early treatment era: the COVID-19 Sardinian Progression Score (CSPS).

De Vito A , Saderi L , Colpani A , Puci MV , Zauli B , Fiore V , Fois M , Meloni MC , Bitti A , Moi G , Maida I , Babudieri S , Sotgiu G , Madeddu G

Eur J Med Res , 29(1):123, 15 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38360688 | PMCID: PMC10868088

Investigating the Potential Shared Molecular Mechanisms between COVID-19 and Alzheimer's Disease via Transcriptomic Analysis.

Fan Y , Liu X , Guan F , Hang X , He X , Jin J

Viruses , 16(1):100, 09 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38257800 | PMCID: PMC10821526

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

- http://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/studies/S-EPMC7227170?xr=true

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Delirium in COVID-19: epidemiology and clinical correlations in a large group of patients admitted to an academic hospital.

Ticinesi A , Cerundolo N , Parise A , Nouvenne A , Prati B , Guerra A , Lauretani F , Maggio M , Meschi T

Aging Clin Exp Res , 32(10):2159-2166, 18 Sep 2020

Cited by: 56 articles | PMID: 32946031 | PMCID: PMC7498987

Effectiveness of Streptococcus Pneumoniae Urinary Antigen Testing in Decreasing Mortality of COVID-19 Co-Infected Patients: A Clinical Investigation.

Desai A , Santonocito OG , Caltagirone G , Kogan M , Ghetti F , Donadoni I , Porro F , Savevski V , Poretti D , Ciccarelli M , Martinelli Boneschi F , Voza A

Medicina (Kaunas) , 56(11):E572, 29 Oct 2020

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 33138045 | PMCID: PMC7693839

Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and cardiac disease in Northern Italy.

Inciardi RM , Adamo M , Lupi L , Cani DS , Di Pasquale M , Tomasoni D , Italia L , Zaccone G , Tedino C , Fabbricatore D , Curnis A , Faggiano P , Gorga E , Lombardi CM , Milesi G , Vizzardi E , Volpini M , Nodari S , Specchia C , [...] Metra M

Eur Heart J , 41(19):1821-1829, 01 May 2020

Cited by: 300 articles | PMID: 32383763 | PMCID: PMC7239204

Delirium Assessment in Critically Ill Older Adults: Considerations During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Duggan MC , Van J , Ely EW

Crit Care Clin , 37(1):175-190, 14 Aug 2020

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 33190768 | PMCID: PMC7427547

Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia with hyperinflammatory syndrome and acute respiratory failure: A single center study of 100 patients in Brescia, Italy.

Toniati P , Piva S , Cattalini M , Garrafa E , Regola F , Castelli F , Franceschini F , Airò P , Bazzani C , Beindorf EA , Berlendis M , Bezzi M , Bossini N , Castellano M , Cattaneo S , Cavazzana I , Contessi GB , Crippa M , Delbarba A , [...] Latronico N

Autoimmun Rev , 19(7):102568, 03 May 2020

Cited by: 476 articles | PMID: 32376398 | PMCID: PMC7252115

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

Hospital Medicine Virtual Journal Club

Clinical Presentation of COVID19 in Dementia Patients.

Link to article at PubMed

J Nutr Health Aging. 2020 May 15;:1-3

Authors: Bianchetti A, Rozzini R, Guerini F, Boffelli S, Ranieri P, Minelli G, Bianchetti L, Trabucchi M

Abstract Objective: No studies analyzing the role of dementia as a risk factor for mortality in patients affected by COVID-19. We assessed the prevalence, clinical presentation and outcomes of dementia among subjects hospitalized for COVID19 infection. Design: Retrospective study. Setting: COVID wards in Acute Hospital in Brescia province, Northern Italy. Participants: We used data from 627 subjects admitted to Acute Medical wards with COVID 19 pneumonia. Measurements: Clinical records of each patients admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of COVID19 infection were retrospectively analyzed. Diagnosis of dementia, modalities of onset of the COVID-19 infection, symptoms of presentation at the hospital and outcomes were recorded. Results: Dementia was diagnosed in 82 patients (13.1%). The mortality rate was 62.2% (51/82) among patients affected by dementia compared to 26.2% (143/545) in subjects without dementia (p<0.001, Chi-Squared test). In a logistic regression model age, and the diagnosis of dementia resulted independently associated with a higher mortality, and patients diagnosed with dementia presented an OR of 1.84 (95% CI: 1.09-3.13, p<0.05). Among patients diagnosed with dementia the most frequent symptoms of onset were delirium, especially in the hypoactive form, and worsening of the functional status. Conclusion: The diagnosis of dementia, especially in the most advanced stages, represents an important risk factor for mortality in COVID-19 patients. The clinical presentation of COVID-19 in subjects with dementia is atypical, reducing early recognition of symptoms and hospitalization.

PMID: 32425646 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher]

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Mastodon (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of new posts by email.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Delirium: clinical presentation and outcomes in older covid-19 patients.

- 1 Geriatric Department, Fondazione Poliambulanza Istituto Ospedaliero, Brescia, Italy

- 2 Associazione Italiana di Psicogeriatria, Brescia, Italy

- 3 Medicine and Rehabilitation Department, Istituto Clinico S. Anna Hospital, Brescia, Italy

- 4 Geriatric Rehabilitation Unit, Anni Azzurri, Brescia, Italy

The aim of the study is to describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of a series of older patients consecutively admitted into a non-ICU ward due to SARS-CoV-2 infection (14, males 11), developing delirium. Hypokinetic delirium with lethargy and confusion was observed in 43% of cases (6/14 patients). A total of eight patients exhibited hyperkinetic delirium and 50% of these patients (4/8) died. The overall mortality rate was 71% (10/14 patients). Among the four survivors we observed two different clinical patterns: two patients exhibited dementia and no ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome), while the remaining two patients exhibited ARDS and no dementia. The observed different clinical patterns of delirium (hypokinetic delirium; hyperkinetic delirium with or without dementia; hyperkinetic delirium with or without ARDS) identified patients with different prognosis: we believe these observations may have an impact on the management of older subjects with delirium due to COVID-19.

Introduction

Although the most frequent and life-threatening complications of coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) are respiratory, there are increasing reports of neurological and psychiatric involvement ( 1 ).

It is known that delirium can be the symptom of the presentation of many diseases, particularly in frail and older patients, and is recognized as an independent risk factor for mortality ( 2 ). The overall prevalence of delirium in the hospital setting is about 14–24%; its prevalence is higher, about 30%, in emergency, surgical, or medical wards ( 3 , 4 ). To date, the clinical presentation of delirium in older patients with COVID-19 infection have rarely been described; in fact, although some studies focus on epidemiological data and outcome, few studies analyze the clinical aspects of delirium in COVID-19 ( 5 – 8 ). The aim of this study is to describe clinical characteristics and outcomes of a series of elderly patients presenting delirium as the main symptom of COVID-19.

Materials and Methods

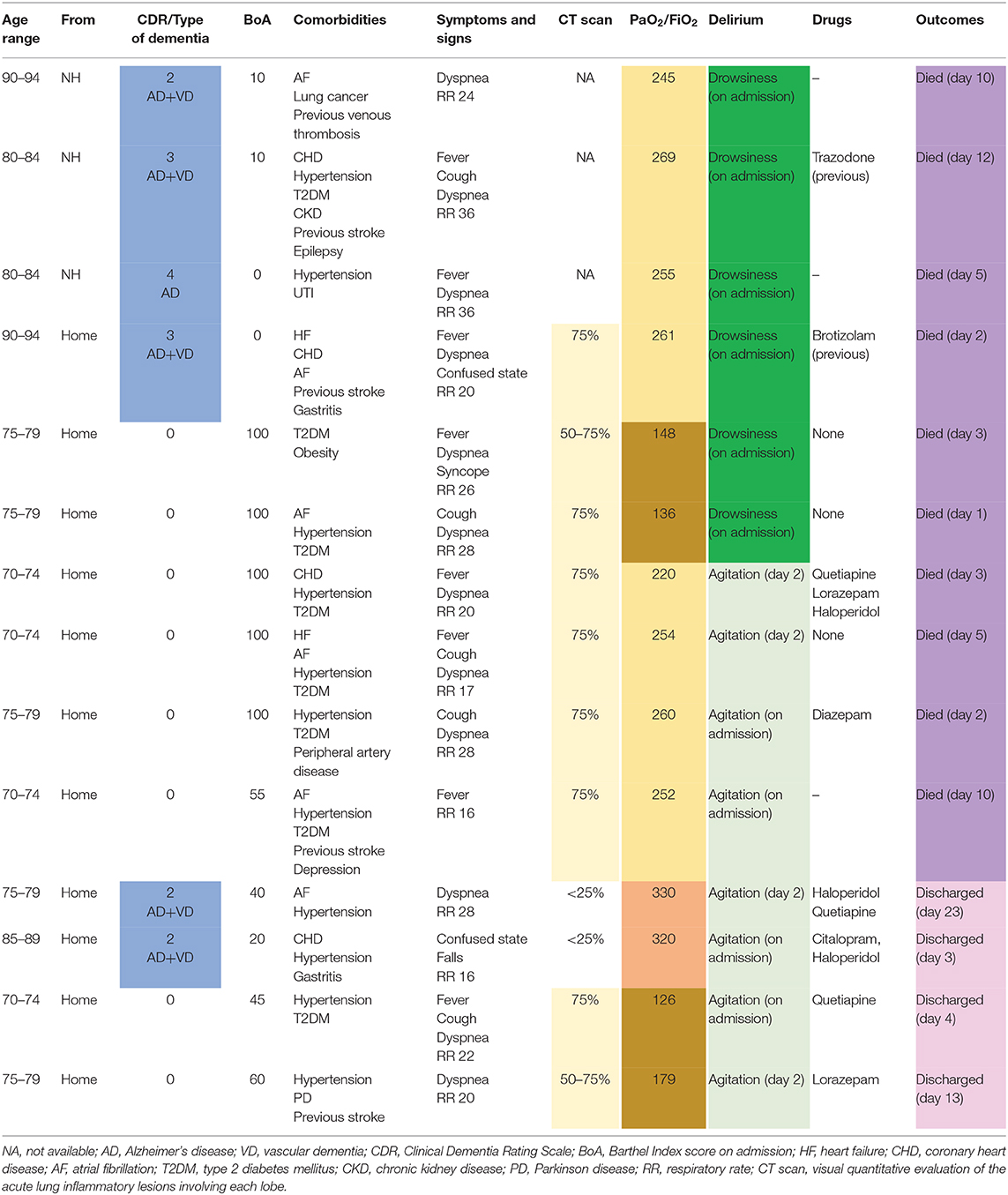

The study was carried out in the COVID ward in an Acute Care Hospital located in Brescia, one of the hardest hit cities by SARS-CoV-2 infection in northern Italy ( 9 ). We collected the characteristics of 14 older patients (age range 70–90, mean age 78.2; 11 males) consecutively admitted developing prevalent or incident delirium (respectively 10 and 4 cases). All the patients were admitted with a diagnosis of COVID-19, confirmed by a real-time reverse-transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR); three patients came from nursing homes, the remainder from home.

Medical information collected were age, sex, PaO 2 /FiO 2 , chest x-ray or CT, comorbidities [ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, diabetes, malignancies, neurodegenerative diseases], blood tests [hemoglobin, platelets count, neutrophils, lymphocytes, C-reactive protein (CRP), urea, and creatinine], and oxygen therapy (i.e., from nasal cannula to high flow cannula oxygen therapy to non-invasive ventilation). To assess the severity of COVID-19 pneumonia the SIAARTI criteria were followed, i.e., mild ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome): PaO 2 /FiO ratio 201–300; moderate ARDS : 101–200, and s evere ARDS : ≤ 100 ( 10 ). The diagnosis of dementia was made on the basis of the data collected from clinical records, while the severity of dementia was assessed by CDR ( 11 ) and functional status by the Barthel Index ( 12 ). CDR was estimated based on information collected from family members and the records of patients. Delirium was detected through 4At (assessment test for delirium and cognitive impairment) ( 13 ).

Clinical criteria were used to characterize delirium subtypes: hypoactive or hyperactive. The presence of a disturbance of consciousness was retrospectively defined by altered arousal.

Hyperactive delirium with aggression and agitation was observed in eight patients, while the remaining six patients exhibited hypoactive delirium with lethargy and confusion.

Moreover, dementia was diagnosed in six out of 14 patients; among these, four developed hypokinetic delirium, while the remaining two developed hyperkinetic delirium. Patients without dementia were younger, with a mean age of 74.1 years (see Table 1 ).

Table 1 . Characteristics and outcomes of 14 older patients with confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and delirium.

The drugs used to treat patients with hyperkinetic delirium were: lorazepam (2 cases), diazepam (1 cases), quetiapine (3 cases), and haloperidol (3 cases). Two patients with hypokinetic prevalent delirium were treated before hospitalization with brotizolam (1 case) and trazodone (1 case).

Two of the patients were hospitalized for stage III pneumonia (PaO 2 /FiO 2 ratio >300), eight patients were hospitalized for stage IV pneumonia-mild ARDS (200<PaO 2 /FiO 2 <3008), and four patients were hospitalized with stage IV pneumonia-moderate ARDS (100<PaO 2 /FiO 2 <200).

Upon admission, the patients presented the following symptoms: fever (7 cases), dyspnea (12 cases), cough (4 cases), fall and syncope (one case).

Almost all the patients (12/14) had a respiratory rate greater than 19.

The overall mortality rate was 71% (10/14 patients). All 6 of the patients exhibiting hypokinetic delirium and the 50% of patients (4/8) with hyperkinetic delirium died. Patients with hypokinetic delirium exhibited dementia and mild ARDS in four cases and no dementia and moderate ARDS in two cases.

Among the four survivors we observed two different clinical patterns: two patients exhibited dementia and no ARDS, while the remaining two patients exhibited ARDS and no dementia.

All patients living in a nursing home developed hypokinetic delirium and died.

A chest CT scan was taken for 11 of the patients: in two cases the lung involvement was less than 25%, in two cases it was from 50 to 75%, and in seven cases it was greater than 75%. The two cases with lower lung involvement survived; one patient with intermediate (50–75%) and one with greater involvement (>75%) also survived.

Each patient showed a high number of comorbidities: nine patients were affected by cardiovascular diseases (mainly coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure), 12 by hypertension, and eight by diabetes. In particular, only four patients had no more than two comorbid conditions. In detail: survivors with hyperkinetic delirium had two or three comorbidities; deceased patients with hyperkinetic delirium had three or more comorbidities; deceased patients with hypokinetic delirium had two comorbidities in two cases and three or more in four cases.

With increasing frequency, delirium is reported as a symptom of the presentation of COVID-19 in older patients, although clinical aspects are rarely characterized ( 14 ). In a French series of elderly patients with COVID-19, delirium was present in 26.7% of patients, in two thirds of the cases in the hypokinetic form ( 15 ). In a series of hospitalized older patients with COVID-19 in the UK, delirium was observed in 25.2% of the sample ( 16 ). In older patients with dementia, delirium was a clinical manifestation of COVID-19 in 67% of cases, in 75% of these cases in the hypokinetic form ( 17 ). Mortality rates in these case series related to COVID-19 disease are still inconclusive and so comparison with other literature is uncertain.

In our patients with delirium, mortality was higher (71%) than previously reported for cases of hospitalized older people with delirium (ranging from 9 to 25%) ( 4 ). All subjects who developed hypokinetic delirium died. According to the literature, this form of delirium is associated with worse outcomes, particularly among patients affected by dementia ( 18 ). Multimorbidity is a condition associated with higher mortality, especially among patients who developed hypokinetic delirium: thus, hypokinetic delirium needs to be considered a marker of poor prognosis even in previously fit patients ( 3 ).

The onset of delirium is due to a complex interaction between the baseline vulnerability of the patient or predisposing factors and noxious insults or precipitating factors; recent observations lead us to believe that frailty and immunosenescence constitute factors that explain the excess mortality in elderly subjects with COVID-19 ( 19 ).

In our study, hyperkinetic delirium in cognitively unimpaired patients with mild ARDS had a better prognostic value than hypokinetic delirium in those with the same lung impairment. Hyperkinetic delirium in patients with dementia was observed in non-ARDS pneumonia (PaO 2 /FiO 2 > 300). Patients with hyperkinetic delirium who died had a higher noxious insult (i.e., 200 < PaO 2 /FiO 2 < 300) or dementia, and high level of comorbidities.

The high mortality rate of subjects developing delirium as an onset symptom of COVID-19, particularly in its hypokinetic form, could suggest brain involvement rather than the worsening effect of a pre-existing condition of frailty. Taking cognizance of the emergency due to the outbreak of COVID-19 and the consequent necessity of brief and easy-to-use tools and the involvement of non-expert doctors and nurses in COVID wards, to diagnose delirium we decided to use the 4AT test, a reliable tool designed for delirium detection in clinical practice ( 13 ).

Based on our observations, we hypothesize that delirium subtypes may be markers of biological severity of precipitating disease in COVID-19 patients. Specifically, patients suffering from a higher involvement of brain function and thus manifesting hypokinetic delirium, have a worse prognosis, while those who develop hyperkinetic delirium with a lower degree of dysregulation induced by the disease have a better chance of survival. Data on the ARDS stage confirm this interpretation since deceased patients with hypokinetic delirium and dementia were the most biologically compromised (with the most severe form of ARDS).

These different clinical patterns (hypokinetic delirium; hyperkinetic delirium with or without dementia; hyperkinetic delirium with or without ARDS) identify patients with different prognosis. Although the data were collected in a relatively limited number of cases, these observations may have an impact on the management of older subjects with delirium due to COVID-19.

In conclusion, our study indicates that delirium, particularly in the hypokinetic form, is related to a high risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19, especially in the presence of dementia. Therefore, a systematic recognition of this syndrome in COVID-19 patients is crucial for establishing a reliable prognosis.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Comitato Etico di Brescia. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

RR, FM, and GC contribute to evaluation of cases, data management and discussion. AB, LB, and MT reviewed and discussed the manuscript. AB and RR wrote the first draft. All authors carefully reviewed, discussed and contributed to various draft of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Leonardi M, Padovani A, McArthur JC. Neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19: a review and a call for action. J Neurol. (2020) 267:1573–6. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09896-z

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Persico I, Cesari M, Morandi A, Haas J, Mazzola P, Zambon A, et al. Frailty and delirium in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2018) 66:2022–30. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15503

3. Bellelli G, Morandi A, Di Santo SG, Mazzone A, Cherubini A, Mossello E, et al. “Delirium Day”: a nationwide point prevalence study of delirium in older hospitalized patients using an easy standardized diagnostic tool. BMC Med. (2016) 14:106. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0649-8

4. Morandi A, Di Santo SG, Zambon A, Mazzone A, Cherubini A, Mossello E, et al. Delirium, dementia, and in-hospital mortality: the results from the italian delirium day 2016, A National Multicenter Study. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2019) 74:910–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly154

5. Tay HS, Harwood R. Atypical presentation of COVID-19 in a frail older person. Age Ageing. (2020) 49:523–4. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa068

6. Alkeridy WA, Almaghlouth I, Alrashed R, Alayed K, Binkhamis K, Alsharidi A, et al. A Unique presentation of delirium in a patient with otherwise asymptomatic COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2020) 68:1382–4. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16536

7. Kotfis K, Williams Roberson S, Wilson JE, Dabrowski W, Pun BT, Ely EW. COVID-19: ICU delirium management during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Crit Care. (2020) 24:176. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02882-x

8. Marengoni A, Zucchelli A, Grande G, Fratiglioni L, Rizzuto D. The impact of delirium on outcomes for older adults hospitalised with COVID-19. Age Ageing . (2020) 49:923–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa189

9. Rozzini R, Bianchetti A. COVID Towers: low- and medium-intensity care for patients not in the ICU. CMAJ . (2020) 192:E463–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.75334

10. SIAARTI. Percorso Assistenziale per il Paziente Affetto da COVID-19 . Sezione 1 - Procedure area critica - versione 02 (2020).

Google Scholar

11. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. (1982) 140:566–72.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

12. Mahoney F, Barthel D. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md Med J . (1995) 14:61–5.

13. Bellelli G, Morandi A, Davis DH, Mazzola P, Turco R, Gentile S, et al. Validation of the 4AT, a new instrument for rapid delirium screening: a study in 234 hospitalised older people. Age Ageing. (2014) 43:496–502. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu021

14. Bianchetti A, Rozzini R, Guerini F, Boffelli S, Ranieri P, Minelli G, et al. Clinical presentation of COVID19 in dementia patients. J Nutr. Health Aging. (2020) 24:560–2. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1389-1

15. Annweiler C, Sacco G, Salles N, Aquino JP, Gautier J, Berrut G, et al. National French survey of COVID-19 symptoms in people aged 70 and over. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) ciaa792. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa792

16. Zazzara MB, Penfold RS, Roberts AL, Lee K, Dooley H, Sudre CH, et al. Delirium is a presenting symptom of COVID-19 in frail, older adults: a cohort study of 322 hospitalised and 535 community-based older adults. medRxiv . (2020) 2020.06.15.20131722. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.15.20131722

17. Bianchetti A, Bellelli G, Guerini F, Marengoni A, Padovani A, Rozzini R, et al. Improving the care of older patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2020) 32:1883–8. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01641-w

18. Rosgen BK, Krewulak KD, Stelfox HT, Ely EW, Davidson JE, Fiest KM. The association of delirium severity with patient and health system outcomes in hospitalised patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. (2020) 49:549–57. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa053

19. Knopp P, Miles A, Webb TE, Mcloughlin BC, Mannan I, Raja N, et al. Presenting features of COVID-19 in older people: relationships with frailty, inflammation and mortality. medRxiv . (2020) 2020.06.07.20120527. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.07.20120527

Keywords: COVID 19, delirium, elderly, frailty, mortality

Citation: Rozzini R, Bianchetti A, Mazzeo F, Cesaroni G, Bianchetti L and Trabucchi M (2020) Delirium: Clinical Presentation and Outcomes in Older COVID-19 Patients. Front. Psychiatry 11:586686. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586686

Received: 23 July 2020; Accepted: 22 September 2020; Published: 12 November 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Rozzini, Bianchetti, Mazzeo, Cesaroni, Bianchetti and Trabucchi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Renzo Rozzini, renzo.rozzini@poliambulanza.it

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

A and B, Histologic findings in an adult man with severe cardiac magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities 67 days after COVID-19 diagnosis. High-sensitivity troponin T level on the day of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was 16.7 pg/mL. The patient recovered at home from COVID-19 illness with minimal symptoms, which included loss of smell and taste and only mildly increased temperature lasting 2 days. There were no known previous conditions or regular medication use. Histology revealed intracellular edema as enlarged cardiomyocytes with no evidence of interstitial or replacement fibrosis. Panels A and B show immunohistochemical staining, which revealed acute lymphocytic infiltration (lymphocyte function–associated antigen 1 and activated lymphocyte T antigen CD45R0) as well as activated intercellular adhesion molecule 1. C to F, Representative cardiac magnetic resonance images of an adult woman with COVID-19–related perimyocarditis. Panels C and D show significantly raised native T1 and native T2 in myocardial mapping acquisitions. Panels E and F show pericardial effusion and enhancement (yellow arrowheads) and epicardial and intramyocardial enhancement (white arrowheads) in late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) acquisition.

There was a small but significant difference between patients who recovered at home vs in the hospital for native T1 (median [interquartile range], 1119 [1092-1150] ms vs 1141 [1121-1175] ms; P = .008) and high-sensitivity troponin T (4.2 [3.0-5.9] pg/dL vs 6.3 [3.4-7.9] pg/dL; P = .002) but not for native T2 or N-terminal pro–b-type natriuretic peptide. For the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) home recovery group, dark circles indicate symptomatic illness and light circles indicate asymptomatic illness. Boxes indicate overlays of box-whisker plots, midlines indicate medians, and whiskers indicate the farthest data point not regarded as an outlier (ie, within 1.5-fold the interquartile range).

There was no significant correlation with duration between the positive test for COVID-19 and the measures (native T1: r = 0.07; P = .47; native T2: r = 0.14; P = .15; high-sensitivity troponin T: r = −0.07; P = .50). The trend line indicates the linear regression trend, and the shaded area indicates 95% CIs of the mean.

eFigure. STROBE diagram

- Younger Adults Cautioned to Take COVID-19 Seriously as Demographics Shift JAMA Medical News & Perspectives December 1, 2020 This Medical News article discusses the health implications of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection among young and middle-aged adults. Jennifer Abbasi

- JAMA Network Articles of the Year 2020 JAMA Medical News & Perspectives December 15, 2020 This Medical News article discusses the top-viewed research articles published across the JAMA Network in the past year. Jennifer Abbasi

- Researchers Investigate What COVID-19 Does to the Heart JAMA Medical News & Perspectives March 2, 2021 This Medical News article discusses reports of myocardial injury and myocarditis among patients with COVID-19. Jennifer Abbasi

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the Heart JAMA Cardiology Editorial November 1, 2020 Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MSc; Gregg C. Fonarow, MD

- Errors in Statistical Numbers and Data in Study of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From COVID-19 JAMA Cardiology Comment & Response November 1, 2020 Eike Nagel, MD; Valentina O. Puntmann, MD, PhD

- Errors in Statistical Numbers and Data JAMA Cardiology Correction November 1, 2020

- Cardiac Involvement After Recovering From COVID-19 JAMA Cardiology Comment & Response February 1, 2021 Łukasz A. Małek, MD, PhD

- Cardiac Involvement After Recovering From COVID-19 JAMA Cardiology Comment & Response February 1, 2021 Laura Filippetti, MD; Nathalie Pace, MD; Pierre-Yves Marie, MD, PhD

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Puntmann VO , Carerj ML , Wieters I, et al. Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(11):1265–1273. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- 1 Institute for Experimental and Translational Cardiovascular Imaging, DZHK Centre for Cardiovascular Imaging, University Hospital Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences and Morphological and Functional Imaging, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

- 3 Department of Infectious Diseases, University Hospital Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- 4 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, University Hospital Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- 5 Department of Cardiology, Goethe University Hospital Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- 6 Department of Hospital Therapy No. 1, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Moscow, Russia

- 7 Institute for Cardiac Diagnostic and Therapy, Berlin, Germany

- Editorial Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the Heart Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MSc; Gregg C. Fonarow, MD JAMA Cardiology

- Medical News & Perspectives Younger Adults Cautioned to Take COVID-19 Seriously as Demographics Shift Jennifer Abbasi JAMA

- Medical News & Perspectives JAMA Network Articles of the Year 2020 Jennifer Abbasi JAMA

- Medical News & Perspectives Researchers Investigate What COVID-19 Does to the Heart Jennifer Abbasi JAMA

- Comment & Response Errors in Statistical Numbers and Data in Study of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From COVID-19 Eike Nagel, MD; Valentina O. Puntmann, MD, PhD JAMA Cardiology

- Correction Errors in Statistical Numbers and Data JAMA Cardiology

- Comment & Response Cardiac Involvement After Recovering From COVID-19 Łukasz A. Małek, MD, PhD JAMA Cardiology

- Comment & Response Cardiac Involvement After Recovering From COVID-19 Laura Filippetti, MD; Nathalie Pace, MD; Pierre-Yves Marie, MD, PhD JAMA Cardiology

Question What are the cardiovascular effects in unselected patients with recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)?

Findings In this cohort study including 100 patients recently recovered from COVID-19 identified from a COVID-19 test center, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging revealed cardiac involvement in 78 patients (78%) and ongoing myocardial inflammation in 60 patients (60%), which was independent of preexisting conditions, severity and overall course of the acute illness, and the time from the original diagnosis.

Meaning These findings indicate the need for ongoing investigation of the long-term cardiovascular consequences of COVID-19.

Importance Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) continues to cause considerable morbidity and mortality worldwide. Case reports of hospitalized patients suggest that COVID-19 prominently affects the cardiovascular system, but the overall impact remains unknown.

Objective To evaluate the presence of myocardial injury in unselected patients recently recovered from COVID-19 illness.

Design, Setting, and Participants In this prospective observational cohort study, 100 patients recently recovered from COVID-19 illness were identified from the University Hospital Frankfurt COVID-19 Registry between April and June 2020.

Exposure Recent recovery from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection, as determined by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction on swab test of the upper respiratory tract.

Main Outcomes and Measures Demographic characteristics, cardiac blood markers, and cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging were obtained. Comparisons were made with age-matched and sex-matched control groups of healthy volunteers (n = 50) and risk factor–matched patients (n = 57).