- FIND SOURCES

- Articles, Books, & More

- Database List

- Course Reserves

- Government Publications

- Special Collections

- My Library Accounts

- Beyond Armacost

- Borrowing Policies

- Get Research Help From a Librarian

- Research Guides

- Information Literacy & Library Instruction

- Open Educational Resources (OER)

- Copyright & Fair Use

- Information Literacy & Library Engagement

- InSPIRe@Redlands

- Armacost Library Undergraduate Research Award (ALURA)

- Honors Paper, Thesis, & Dissertation Submissions

- Call, Chat, & Email

- Cite My Sources

- INFORMATION FOR

- College of Arts & Sciences Students

- School of Business & Society Students

- School of Education Students

- School of Continuing Studies Students

- Staff & Administrators

- Visitors & Alumni

- Patrons with Accommodation Needs

- Staff Directory

- Map of the Library

- Internships

University of Redlands

- Armacost Library

- CREATIVE WRITING

- How to Cite Your Sources

CREATIVE WRITING: How to Cite Your Sources

- Introduction

- Understanding Research

- Search Armacost Library

- Browse in the Library

- Literary Magazines

- Disciplinary Databases

- Finding News Articles

This page will help you...

- Understand why you need to cite your sources

- Find online and physical library citation style guides

- Access a free, open source citation management tool

Citing Sources

- It's Required. But Why?

- Fairfield University MLA Guide

- MLA Style Center

- How do I cite generative AI in MLA style?

What Citations Reveal & How They Impact Us

"When you cite a source, you show how your voice enters into an intellectual conversation and you demonstrate your link to the community within which you work. Working with sources can inspire your own ideas and enrich them, and your citation of these sources is the visible trace of that debt." ( Yale College Writing Center )

When you cite a source you also reveal whose voices and thoughts are included in these intellectual conversations. Thus, who you read and what you cite can help strengthen diversity and equity in scholarship.

We are a collective of Black women of first-generation, queer, working class and poor, immigrant, and disabled experience and we formed out of the necessity to cite, (re)claim, and honor Black women's work. #CiteBlackWomen — Cite Black Women. (@citeblackwomen) September 9, 2020

To Connect Ideas | To Acknowledge a Community of Contributors | To Read & Cite Inclusively

Featured style guide

Additional online citation guides.

When citing scores, images, recordings and other less-traditional sources, start with the style recommended by your professor. Determine what rules pertain to your situation and adapt them as necessary. If the information provider has specified how they want their source cited, try to follow those instructions. These online guides to citing specific information formats may help:

- Citing American FactFinder Tables and Maps

- Citing Audio from the University of Cincinnati

- Citing Data and Statistics from Michigan State

Recommended citation helper

Zotero is a free, open source citation management program maintained by the nonprofit Corporation for Digital Scholarship .

Designed for students and scholars, Zotero makes collecting, managing and citing sources easier.

The software consists of three parts:

- A browser plugin that you click to collect citations from a library catalog, database or website

- A database to store and manage your citations

- Icons in your word processor that you click to insert a citation or works cited list.

Like any citation management program, Zotero is not perfect. It knows enough about citation styles to give you a good first draft of your citatoin sand works cited list. However, it relies on information found in databases and websites which are not always accurate.

I recommend that you double-check citations and works cited lists created with Zotero against the official style guide. Make sure you know the type of source you are trying to cite and check the capitalization and punctuation carefully.

Armacost Library has created this guide to help you learn to use Zotero:

- Zotero: A Guide on Getting Started by Emily Croft Last Updated Sep 18, 2020 76 views this year

- Citing sources lets you indicate whose ideas your own work draws upon, and give those individuals credit for their contributions.

- The MLA style guide is only available in the physical library. If you're not able to access it, try an online guide to MLA style.

- Zotero is a free, open source tool you can use to manage your citations.

See the "Using information ethically" chapter in the Introduction to Library Research in the Arts to learn more about ethical research practices, including inclusive citing practices and bibliodiversity.

- << Previous: Finding News Articles

- Next: Feedback >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 11:24 AM

- URL: https://library.redlands.edu/crwr

- My Redlands

- A-Z Directory

Tel: (909) 793-2121

Fax: (909) 793-2029

- ©2016 University of Redlands. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Policy

Creative Writing: Referencing

- Referencing

- Web Resources

- Literary magazines

Why reference?

It is important to learn the scholarly practice of citing other people’s research, and referencing the material you have used.

Referencing:

Enables your reader to find the material you have referred to

Demonstrates your breadth of reading about the subject

Supports and/or develops your argument

Avoids plagiarism: using somebody else’s work without acknowledging the fact is plagiarism. It is important to always reference when quoting or paraphrasing another person’s work

What is Referencing?

Referencing is the academic practice of acknowledging the sources you have used in your work. Sources may be other people's words and ideas.

Plagiarism is the use of another person's work without proper acknowledgment. Most plagiarism is unintentional and the result of poor academic practice. It's is important to reference when directly quoting or paraphrasing another person's work.

Referencing styles are sets of rules governing referencing practice. They prescribe the type, order and format of information in a reference. There are 3 main types of referencing style: in-text, footnote and endnote. Always check what referencing style is required by your department or assessment, as there may be local interpretations.

Referencing ebooks

Cite Them Right

The complete guide to referencing and avoiding plagiarism

Your Department Style : MLA

Mla referencing style.

The Warwick Writing Programme requires most students to use the MLA referencing style (currently in its 9th edition). The following resources will help you:

OWL Purdue MLA Formatting and Style Guide

A clear, easy to follow web guide to the MLA style, covering all main reference types.

MLA Style Center

Guidance and resources for the MLA style and a good place to look for answers to more obscure referencing questions!

MLA H andbook

The definitive guide to the MLA style, available in print through the Library.

Your Department Style : MHRA

Mhra referencing style.

Many joint degree students will use the MHRA referencing style in your home departments and this style is also acceptable to the English department. (You may just want to mention to your tutors that you are using this style). The following resources will help you:

The MHRA have a comprehensive PDF guide, covering all main reference types (referencing is in chapter 11).

MHRA Style Guide PDF

MHRA style guide : a handbook for authors, editors, and writers of theses (available in print in the Library)

Referencing Moodle

Introduction to referencing..

Learn what referencing is, why it is important and when you need to use it.

Note that this course uses examples in the Harvard referencing style, not your departmental style.

Avoiding Plagiarism

This course will help you understand how plagiarism is defined, identified and its potential consequences. It will also provide you with clear tips on how to avoid plagiarism and build good academic practice.

Referencing Software

Referencing software allows you to manage references, insert citations and create a bibliography, in your referencing style. It is particularly useful for students writing dissertations and theses.

EndNote is referencing software from Clarivate. EndNote Desktop supports the OSCOLA legal referencing style. EndNote is available from Warwick IT Services, and is supported by Warwick Library. Please see the EndNote LibGuide for further information.

- << Previous: Databases

- Next: Web Resources >>

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2023 2:15 PM

- URL: https://warwick.libguides.com/creative-writing

- University of Warwick Library Gibbet Hill Road Coventry CV4 7AL

- Telephone: +44 (0)24 76 522026

- Email: library at warwick dot ac dot uk

- More contact details

About the Library

Quick links.

- Get Started

- E-resources

- Endnote Online

- Get it For Me

- Course Extracts

What Is a Citation in Writing?

Written by Rebecca Turley

Samuel Adams perhaps said it best: “Give credit where credit is due” (although the quote was taken from his original “give credit to whom credit is due”). Though Adams wrote this adage way back in 1777, it holds true today. Writers have a moral (and often legal) obligation to give credit when using another person’s words.

A citation informs a reader that some of your information came from another source. Citations in writing allow writers to give credit to other writers or speakers. The term “citing a work” means to disclose the source of the information through a properly formatted and structured citation.

Citations are Important to Writers, Editors, and Readers

Citations are far more than just torture for a writer. Taking the time to cite a source and provide a properly formatted citation may be a bothersome step in the writing process, but it’s an important one.

Citations lend credibility to your writing because they back up/support your claims or ideas. Citing other works strengthens your work and shows the reader that you have written a solid, well-researched piece. In some cases, it can even pass the buck off to another source when a theory, idea, or claim doesn’t hold water.

Citations also serve as a valuable resource for readers who want to read other materials written on the subject.

Plus, if the tables were turned, wouldn’t you want another writer to cite your work?

Avoiding the Big P – As in Plagiarism

At its worse, failing to properly cite another person’s work is dishonest and unethical. Get slapped with plagiarism (passing off someone else’s work as your own) and your work immediately becomes null and void, and you become an untrustworthy author of information – a veritable Scarlet Letter in the world of writing (or in your field or industry).

Plagiarism is illegal because original works of authorship (includes literary, dramatic, and musical works) are protected under copyright law. Therefore, failing to property cite sources opens the door to another author taking legal action against you.

All About the Citation in Writing: When to Use It, What It Looks Like

If you’re using someone else’s words or ideas from a magazine, book, newspaper, journal, interview, TV show, lecture, speech, website, blog, song, advertisement, or letter, you’ll need to use a citation.

You’ll always use a citation when:

- Quoting what a person said or wrote

- Paraphrasing what a person said or wrote

- Quoting or paraphrasing what a person said or wrote in an interview or when conversing with another person

- Writing about an idea, theory, or method that someone else has already expressed

- Using facts and figures (numbers, percentages, etc.) from an exclusive source

- Specifically referencing the work of another person

- Reprinting an image, graph, chart, illustration, etc.

- Reposting any digital media

- Copying exact words or unique phrases

If you use someone else’s work or ideas as inspiration, you’ll also likely want to cite your source.

The general rule of thumb regarding citation is: When in Doubt, Cite.

But there are some instances where you can feel comfortable not using a citation:

- Common knowledge – Common knowledge is something that has been written about widely and includes facts that can be found in multiple credible sources. Think factual beyond dispute when considering if something is common knowledge.

- George Washington was the first U.S. President.

- Japan’s surrender marked the end of WWII.

- The Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776.

- Generally acknowledged facts – If you include facts that are generally acknowledged to be true, you won’t have to cite them.

- Most teenagers use cell phones.

- Soda is a source of empty calories.

- Walking is good for your health.

- Folklore, myths, and urban legends

- George Washington chopped down the cherry tree.

- A penny dropped from the Empire State Building could kill someone.

- Lightning never strikes twice.

- When writing about your own observations, insights, or thoughts

- When writing about the results obtained by conducting your own experiment or study

- When using your own artwork, image, video, audio, etc.

Types of Citations – MLA, APA, Chicago

A citation in writing is a two-step process.

First , you’ll cite the source in the body of your work by using standardized citation methods according to one of the three standard style guides – MLA, Chicago, APA:

- Superscripts numbers

- Parentheticals

When using MLA or APA styles, your in-text citations are formatted in parentheticals that are inserted at the end of a sentence or paragraph. MLA parenthetical notes include the author’s name and the page number. For example, (McGinnis, p. 12). APA parenthetical notes also include the year of the publication. For example, (McGinnis, 2008, p. 12).

The superscript numerals are associated with full citations that are listed at the bottom of the page (footnotes), at the end of a chapter (endnotes), or as a list of cited references at the end of the paper. The superscript numbers are found chronologically and match the footnote, endnote, or cited reference page numbers for easy referencing.

Then , you’ll provide all the necessary citation details on a dedicated citation page that’s found at the end of your work. (Note: the citation page is referred to as a Works Cited page in MLA style, References page in APA, and Bibliography in Chicago)

A proper citation includes key information:

- Title of the work

- Publishing information (title, date, volume, issue, pages, etc.)

- URL (for online sources)

Each style has its own citation formatting:

MLA : Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Periodical, volume, issue, year, pages.

APA : Last name, First initial. (Year). Title of article. Title of periodical, volume number (issue number), pages.

Chicago : Author full name, Book Title: Subtitle, edition. (Place of publication: Publisher, Year), page numbers.

When to Quote, When to Paraphrase

Paraphrasing or summarizing someone else’s work is used when you want to convey the message or idea in your own words. It’s also helpful when condensing information (i.e., you can get the point across in fewer words).

While there’s no written rule, a blend of quotes and paraphrases often works best, although it’s best to paraphrase when you can because the work, after all, should be in your voice. According to MLA style, quotes should be used “selectively.”

It may also be effective to blend paraphrasing with direct quotes. Such as:

Direct quote: “We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Paraphrase with direct quote: In the Preamble to the United States Constitution, it states that the people of the United States will “secure the blessings of liberty.”

- Teesside University Student & Library Services

- Subject LibGuides

English and Creative Writing

- How to Reference

- Finding Books

- Finding Journal Articles

- Finding Digital Media, Newspapers and Primary Sources

- Resources for finding Open Access content

- Writing Assignments

- Reading Lists Online

- Teesside Advance Recommended Book Bundles

Why do I need to reference?

You need to reference to:.

- acknowledge the work of other writers.

- demonstrate the body of knowledge upon which your research is based.

- show you have widely researched the topic and on what authority you based your arguments and conclusions.

- enable all those who have read your work to locate your sources easily.

- avoid being accused of plagiarism - that is passing off someone else's work as your own.

There are two parts to referencing:

- Citation: the acknowledgement in your text, giving brief details of the work. The reader should be able to identify or locate the work from these details in your reference list or bibliography.

- Reference list: the list of references at the end of your work. These should include the full information for your citations so that readers can easily identify and locate each piece of work that you have used. It is important that these are consistent, correct and complete.

MHRA style of referencing

The School now uses the MHRA referencing .

If you have previously used Chicago in past years of your course you may continue to use the Chicago style (see the box below for advice).

Click on the links below to access the MHRA referencing guidelines for English and Creative Writing .

- English studies and creative writing guide to referencing

- MHRA English studies and creative writing guide to the presentation of written work

- Word version of MHRA presentation

Chicago style of referencing

Please note the MHRA style of referencing is being used by the School.

Continuing students may still use Chicago.

- Chicago referencing guidelines

- University of York Chicago style further examples of citations and references

To login to RefWorks click on the RefWorks image below:

RefWorks allows you to create and manage your own personal database of useful references. You can then use these to quickly compile a reference list or bibliography for your assignments.

Click on the link below for more information, and help on using Refworks.

- Refworks Guide

- << Previous: Resources for finding Open Access content

- Next: Writing Assignments >>

- Last Updated: May 1, 2024 5:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.tees.ac.uk/english_and_creative_writing

Citation guides

All you need to know about citations

How to cite “Creative Writing” by Casey Clabough

Apa citation.

Formatted according to the APA Publication Manual 7 th edition. Simply copy it to the References page as is.

If you need more information on APA citations check out our APA citation guide or start citing with the BibguruAPA citation generator .

Clabough, C. (2014). Creative Writing . Alpha.

Chicago style citation

Formatted according to the Chicago Manual of Style 17 th edition. Simply copy it to the References page as is.

If you need more information on Chicago style citations check out our Chicago style citation guide or start citing with the BibGuru Chicago style citation generator .

Clabough, Casey. 2014. Creative Writing . London, England: Alpha.

MLA citation

Formatted according to the MLA handbook 9 th edition. Simply copy it to the Works Cited page as is.

If you need more information on MLA citations check out our MLA citation guide or start citing with the BibGuru MLA citation generator .

Clabough, Casey. Creative Writing . Alpha, 2014.

Other citation styles (Harvard, Turabian, Vancouver, ...)

BibGuru offers more than 8,000 citation styles including popular styles such as AMA, ASA, APSA, CSE, IEEE, Harvard, Turabian, and Vancouver, as well as journal and university specific styles. Give it a try now: Cite Creative Writing now!

Publication details

This is not the edition you are looking for? Check out our BibGuru citation generator for additional editions.

Creative Writing: MLA Citation

- Theses & Dissertations

- Professional Associations

- Local Literary Community

- Low Residency MFA Student Info

- Online Resources for Writers

- MLA Citation

- Primary Sources This link opens in a new window

- Library DIY This link opens in a new window

MLA Citation Style

The Modern Language Association (MLA) citation style is used for academic papers written primarily in the humanities. Please note that citation styles encompass not only how sources are cited but also how the paper is formatted.

Want more help with updated MLA citation style? Stop by the Reference Desk!

MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers

The NEW 8th edition of the MLA Handbook is available for 2 hour loan at the Circulation Desk!

Questions? Ask a JKM Librarian!

Mla citation style guides.

- PurdueOWL: MLA Formatting and Style Guide Use the navigation on the left to find citation by types of sources, sample papers, and more.

- MLA Overview & Workshop An overview of MLA Style with links explaining formatting and elements

MLA Citation Creators

Please note that while citation creators can be helpful and time-saving, they are nevertheless unreliable: Check your citations for correct formatting with one of the MLA citation guides listed above

- Zotero In addition to creating citations, Zotero also provides storage for articles and other information.

- Mendeley In addition to creating citations, this tool provides you a place to store all your research articles and other information.

- ZoteroBib a free service that helps you build a bibliography or make citations instantly from any computer or device, without creating an account or installing any software.

- << Previous: Online Resources for Writers

- Next: Primary Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 11, 2024 12:00 PM

- URL: https://library.chatham.edu/creativewriting

University of Pittsburgh Library System

- Collections

Course & Subject Guides

Citation styles: apa, mla, chicago, turabian, ieee.

- APA 7th Edition

- Turabian 9th

- Writing & Citing Help

- Understanding Plagiarism

Quick Links

Listed below are a few quick links to resources that will aid you in citing sources.

- Sign up for a Mendeley, EndNote, or Zotero training class.

- APA 7th Edition Published in October 2019. Visit this page for links to resources and examples.

- MLA Need help with citing MLA style? Find information here along with links to books in PittCat and free online resources.

- Chicago/Turabian Need help with citing Chicago/Turabian style? Find examples here along with links to the online style manual and free online resources.

Getting Started: How to use this guide

This LibGuide was designed to provide you with assistance in citing your sources when writing an academic paper.

There are different styles which format the information differently. In each tab, you will find descriptions of each citation style featured in this guide along with links to online resources for citing and a few examples.

What is a citation and citation style?

A citation is a way of giving credit to individuals for their creative and intellectual works that you utilized to support your research. It can also be used to locate particular sources and combat plagiarism. Typically, a citation can include the author's name, date, location of the publishing company, journal title, or DOI (Digital Object Identifier).

A citation style dictates the information necessary for a citation and how the information is ordered, as well as punctuation and other formatting.

How to do I choose a citation style?

There are many different ways of citing resources from your research. The citation style sometimes depends on the academic discipline involved. For example:

- APA (American Psychological Association) is used by Education, Psychology, and Sciences

- MLA (Modern Language Association) style is used by the Humanities

- Chicago/Turabian style is generally used by Business, History, and the Fine Arts

*You will need to consult with your professor to determine what is required in your specific course.

Click the links below to find descriptions of each style along with a sample of major in-text and bibliographic citations, links to books in PittCat, online citation manuals, and other free online resources.

- APA Citation Style

- MLA Citation Style

- Chicago/Turabian Citation Style

- Tools for creating bibliographies (CItation Managers)

Writing Centers

Need someone to review your paper? Visit the Writing Center or Academic Success Center on your campus.

- Oakland Campus

- Greensburg Campus

- Johnstown Campus

- Titusville Campus

- Bradford Campus

- Next: APA 7th Edition >>

- Last Updated: May 20, 2024 9:46 AM

- URL: https://pitt.libguides.com/citationhelp

- Libraries Home

APA Citation Guide (APA 7th Edition)

- Creative Commons Licensed Works

- Introduction

- Advertisements

- Audio Materials

- Books, eBooks, Course Packs, Lab Manuals & Pamphlets

- Class Notes, Class Lectures and Presentations

What is Creative Commons?

- Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

- Government Documents

- Journal Articles

- Magazine Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Personal Communications (interviews, emails, etc.)

- Religious & Classical (e.g., Ancient Greek, Roman) Works

- Social Media

- When Information Is Missing

- Works Quoted in Another Source (Indirect Sources)

- In-Text Citation

- Citation & Writing Help

Creative Commons (CC) is a way for creators to make ordinarily copyrighted work (books, images, etc.) available to others.

How do I know if something has a CC license?

What does the license allow me to do with the work (book, image, etc.)?

You can usually find the CC license on the page where you found the work. When you click on the CC image license it will indicate what you are allowed to do. Common license terms are that you are allowed to share and adapt/modify the work, as long as you provide attribution (i.e. cite).

Do I still need to cite something that has a CC license?

Yes, you always need to credit other people's work.

In most cases, the CC license will specify that you need to "provide attribution" (aka cite), but even when the CC license does not specify that you must provide attribution, Seneca Libraries recommends that you still do so.

Citation Rules:

Note to Students: Seek clarification from your instructor on how they would like you to cite and which rules to follow.

When creating a digital assignment , the Creative Commons formatting rules (on this page under Attributing Sources) may be all that is required by your instructor.

When writing an APA or MLA essay, your instructor may want you to follow APA or MLA guidelines for citing the CC licensed work, with the added Creative Commons license information.

Note that there are no current APA or MLA instructions for citing CC licensed works. Please check with your instructor for guidance.

Ideal attribution

Here is a photo. Following it is an ideal example of how people might attribute it.

This is an ideal attribution

Above ideal attribution example, "Best Practices for Attribution" by CC is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- << Previous: Class Notes, Class Lectures and Presentations

- Next: Encyclopedias & Dictionaries >>

- Last Updated: Dec 20, 2023 11:38 AM

- URL: https://guides.stlcc.edu/apa

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

MLA In-Text Citations: The Basics

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Guidelines for referring to the works of others in your text using MLA style are covered throughout the MLA Handbook and in chapter 7 of the MLA Style Manual . Both books provide extensive examples, so it's a good idea to consult them if you want to become even more familiar with MLA guidelines or if you have a particular reference question.

Basic in-text citation rules

In MLA Style, referring to the works of others in your text is done using parenthetical citations . This method involves providing relevant source information in parentheses whenever a sentence uses a quotation or paraphrase. Usually, the simplest way to do this is to put all of the source information in parentheses at the end of the sentence (i.e., just before the period). However, as the examples below will illustrate, there are situations where it makes sense to put the parenthetical elsewhere in the sentence, or even to leave information out.

General Guidelines

- The source information required in a parenthetical citation depends (1) upon the source medium (e.g. print, web, DVD) and (2) upon the source’s entry on the Works Cited page.

- Any source information that you provide in-text must correspond to the source information on the Works Cited page. More specifically, whatever signal word or phrase you provide to your readers in the text must be the first thing that appears on the left-hand margin of the corresponding entry on the Works Cited page.

In-text citations: Author-page style

MLA format follows the author-page method of in-text citation. This means that the author's last name and the page number(s) from which the quotation or paraphrase is taken must appear in the text, and a complete reference should appear on your Works Cited page. The author's name may appear either in the sentence itself or in parentheses following the quotation or paraphrase, but the page number(s) should always appear in the parentheses, not in the text of your sentence. For example:

Both citations in the examples above, (263) and (Wordsworth 263), tell readers that the information in the sentence can be located on page 263 of a work by an author named Wordsworth. If readers want more information about this source, they can turn to the Works Cited page, where, under the name of Wordsworth, they would find the following information:

Wordsworth, William. Lyrical Ballads . Oxford UP, 1967.

In-text citations for print sources with known author

For print sources like books, magazines, scholarly journal articles, and newspapers, provide a signal word or phrase (usually the author’s last name) and a page number. If you provide the signal word/phrase in the sentence, you do not need to include it in the parenthetical citation.

These examples must correspond to an entry that begins with Burke, which will be the first thing that appears on the left-hand margin of an entry on the Works Cited page:

Burke, Kenneth. Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method . University of California Press, 1966.

In-text citations for print sources by a corporate author

When a source has a corporate author, it is acceptable to use the name of the corporation followed by the page number for the in-text citation. You should also use abbreviations (e.g., nat'l for national) where appropriate, so as to avoid interrupting the flow of reading with overly long parenthetical citations.

In-text citations for sources with non-standard labeling systems

If a source uses a labeling or numbering system other than page numbers, such as a script or poetry, precede the citation with said label. When citing a poem, for instance, the parenthetical would begin with the word “line”, and then the line number or range. For example, the examination of William Blake’s poem “The Tyger” would be cited as such:

The speaker makes an ardent call for the exploration of the connection between the violence of nature and the divinity of creation. “In what distant deeps or skies. / Burnt the fire of thine eyes," they ask in reference to the tiger as they attempt to reconcile their intimidation with their relationship to creationism (lines 5-6).

Longer labels, such as chapters (ch.) and scenes (sc.), should be abbreviated.

In-text citations for print sources with no known author

When a source has no known author, use a shortened title of the work instead of an author name, following these guidelines.

Place the title in quotation marks if it's a short work (such as an article) or italicize it if it's a longer work (e.g. plays, books, television shows, entire Web sites) and provide a page number if it is available.

Titles longer than a standard noun phrase should be shortened into a noun phrase by excluding articles. For example, To the Lighthouse would be shortened to Lighthouse .

If the title cannot be easily shortened into a noun phrase, the title should be cut after the first clause, phrase, or punctuation:

In this example, since the reader does not know the author of the article, an abbreviated title appears in the parenthetical citation, and the full title of the article appears first at the left-hand margin of its respective entry on the Works Cited page. Thus, the writer includes the title in quotation marks as the signal phrase in the parenthetical citation in order to lead the reader directly to the source on the Works Cited page. The Works Cited entry appears as follows:

"The Impact of Global Warming in North America." Global Warming: Early Signs . 1999. www.climatehotmap.org/. Accessed 23 Mar. 2009.

If the title of the work begins with a quotation mark, such as a title that refers to another work, that quote or quoted title can be used as the shortened title. The single quotation marks must be included in the parenthetical, rather than the double quotation.

Parenthetical citations and Works Cited pages, used in conjunction, allow readers to know which sources you consulted in writing your essay, so that they can either verify your interpretation of the sources or use them in their own scholarly work.

Author-page citation for classic and literary works with multiple editions

Page numbers are always required, but additional citation information can help literary scholars, who may have a different edition of a classic work, like Marx and Engels's The Communist Manifesto . In such cases, give the page number of your edition (making sure the edition is listed in your Works Cited page, of course) followed by a semicolon, and then the appropriate abbreviations for volume (vol.), book (bk.), part (pt.), chapter (ch.), section (sec.), or paragraph (par.). For example:

Author-page citation for works in an anthology, periodical, or collection

When you cite a work that appears inside a larger source (for instance, an article in a periodical or an essay in a collection), cite the author of the internal source (i.e., the article or essay). For example, to cite Albert Einstein's article "A Brief Outline of the Theory of Relativity," which was published in Nature in 1921, you might write something like this:

See also our page on documenting periodicals in the Works Cited .

Citing authors with same last names

Sometimes more information is necessary to identify the source from which a quotation is taken. For instance, if two or more authors have the same last name, provide both authors' first initials (or even the authors' full name if different authors share initials) in your citation. For example:

Citing a work by multiple authors

For a source with two authors, list the authors’ last names in the text or in the parenthetical citation:

Corresponding Works Cited entry:

Best, David, and Sharon Marcus. “Surface Reading: An Introduction.” Representations , vol. 108, no. 1, Fall 2009, pp. 1-21. JSTOR, doi:10.1525/rep.2009.108.1.1

For a source with three or more authors, list only the first author’s last name, and replace the additional names with et al.

Franck, Caroline, et al. “Agricultural Subsidies and the American Obesity Epidemic.” American Journal of Preventative Medicine , vol. 45, no. 3, Sept. 2013, pp. 327-333.

Citing multiple works by the same author

If you cite more than one work by an author, include a shortened title for the particular work from which you are quoting to distinguish it from the others. Put short titles of books in italics and short titles of articles in quotation marks.

Citing two articles by the same author :

Citing two books by the same author :

Additionally, if the author's name is not mentioned in the sentence, format your citation with the author's name followed by a comma, followed by a shortened title of the work, and, when appropriate, the page number(s):

Citing multivolume works

If you cite from different volumes of a multivolume work, always include the volume number followed by a colon. Put a space after the colon, then provide the page number(s). (If you only cite from one volume, provide only the page number in parentheses.)

Citing the Bible

In your first parenthetical citation, you want to make clear which Bible you're using (and underline or italicize the title), as each version varies in its translation, followed by book (do not italicize or underline), chapter, and verse. For example:

If future references employ the same edition of the Bible you’re using, list only the book, chapter, and verse in the parenthetical citation:

John of Patmos echoes this passage when describing his vision (Rev. 4.6-8).

Citing indirect sources

Sometimes you may have to use an indirect source. An indirect source is a source cited within another source. For such indirect quotations, use "qtd. in" to indicate the source you actually consulted. For example:

Note that, in most cases, a responsible researcher will attempt to find the original source, rather than citing an indirect source.

Citing transcripts, plays, or screenplays

Sources that take the form of a dialogue involving two or more participants have special guidelines for their quotation and citation. Each line of dialogue should begin with the speaker's name written in all capitals and indented half an inch. A period follows the name (e.g., JAMES.) . After the period, write the dialogue. Each successive line after the first should receive an additional indentation. When another person begins speaking, start a new line with that person's name indented only half an inch. Repeat this pattern each time the speaker changes. You can include stage directions in the quote if they appear in the original source.

Conclude with a parenthetical that explains where to find the excerpt in the source. Usually, the author and title of the source can be given in a signal phrase before quoting the excerpt, so the concluding parenthetical will often just contain location information like page numbers or act/scene indicators.

Here is an example from O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh.

WILLIE. (Pleadingly) Give me a drink, Rocky. Harry said it was all right. God, I need a drink.

ROCKY. Den grab it. It's right under your nose.

WILLIE. (Avidly) Thanks. (He takes the bottle with both twitching hands and tilts it to his lips and gulps down the whiskey in big swallows.) (1.1)

Citing non-print or sources from the Internet

With more and more scholarly work published on the Internet, you may have to cite sources you found in digital environments. While many sources on the Internet should not be used for scholarly work (reference the OWL's Evaluating Sources of Information resource), some Web sources are perfectly acceptable for research. When creating in-text citations for electronic, film, or Internet sources, remember that your citation must reference the source on your Works Cited page.

Sometimes writers are confused with how to craft parenthetical citations for electronic sources because of the absence of page numbers. However, these sorts of entries often do not require a page number in the parenthetical citation. For electronic and Internet sources, follow the following guidelines:

- Include in the text the first item that appears in the Work Cited entry that corresponds to the citation (e.g. author name, article name, website name, film name).

- Do not provide paragraph numbers or page numbers based on your Web browser’s print preview function.

- Unless you must list the Web site name in the signal phrase in order to get the reader to the appropriate entry, do not include URLs in-text. Only provide partial URLs such as when the name of the site includes, for example, a domain name, like CNN.com or Forbes.com, as opposed to writing out http://www.cnn.com or http://www.forbes.com.

Miscellaneous non-print sources

Two types of non-print sources you may encounter are films and lectures/presentations:

In the two examples above “Herzog” (a film’s director) and “Yates” (a presentor) lead the reader to the first item in each citation’s respective entry on the Works Cited page:

Herzog, Werner, dir. Fitzcarraldo . Perf. Klaus Kinski. Filmverlag der Autoren, 1982.

Yates, Jane. "Invention in Rhetoric and Composition." Gaps Addressed: Future Work in Rhetoric and Composition, CCCC, Palmer House Hilton, 2002. Address.

Electronic sources

Electronic sources may include web pages and online news or magazine articles:

In the first example (an online magazine article), the writer has chosen not to include the author name in-text; however, two entries from the same author appear in the Works Cited. Thus, the writer includes both the author’s last name and the article title in the parenthetical citation in order to lead the reader to the appropriate entry on the Works Cited page (see below).

In the second example (a web page), a parenthetical citation is not necessary because the page does not list an author, and the title of the article, “MLA Formatting and Style Guide,” is used as a signal phrase within the sentence. If the title of the article was not named in the sentence, an abbreviated version would appear in a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence. Both corresponding Works Cited entries are as follows:

Taylor, Rumsey. "Fitzcarraldo." Slant , 13 Jun. 2003, www.slantmagazine.com/film/review/fitzcarraldo/. Accessed 29 Sep. 2009.

"MLA Formatting and Style Guide." The Purdue OWL , 2 Aug. 2016, owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/747/01/. Accessed 2 April 2018.

Multiple citations

To cite multiple sources in the same parenthetical reference, separate the citations by a semi-colon:

Time-based media sources

When creating in-text citations for media that has a runtime, such as a movie or podcast, include the range of hours, minutes and seconds you plan to reference. For example: (00:02:15-00:02:35).

When a citation is not needed

Common sense and ethics should determine your need for documenting sources. You do not need to give sources for familiar proverbs, well-known quotations, or common knowledge (For example, it is expected that U.S. citizens know that George Washington was the first President.). Remember that citing sources is a rhetorical task, and, as such, can vary based on your audience. If you’re writing for an expert audience of a scholarly journal, for example, you may need to deal with expectations of what constitutes “common knowledge” that differ from common norms.

Other Sources

The MLA Handbook describes how to cite many different kinds of authors and content creators. However, you may occasionally encounter a source or author category that the handbook does not describe, making the best way to proceed can be unclear.

In these cases, it's typically acceptable to apply the general principles of MLA citation to the new kind of source in a way that's consistent and sensible. A good way to do this is to simply use the standard MLA directions for a type of source that resembles the source you want to cite.

You may also want to investigate whether a third-party organization has provided directions for how to cite this kind of source. For example, Norquest College provides guidelines for citing Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers —an author category that does not appear in the MLA Handbook . In cases like this, however, it's a good idea to ask your instructor or supervisor whether using third-party citation guidelines might present problems.

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, citation conventions – what is the role of citation in academic & professional writing.

Explore the role of citation in academic and professional writing . Understand how citations establish trust, establish a professional tone, validate the authenticity of claims, and uphold ethical standards.

What is the Role of Citation in Academic & Professional Writing?

Citation serves as a method for humankind to keep track of scholarly conversation and the evolution of human knowledge

Human knowledge is shaped by conversation . To make meaning — to develop new ideas and test old ideas — we engage in self talk and in conversation with others. We learn from co-authorships , teamwork, and hours of hours of dialog. We evolve by engaging in conversations , both spoken and written. This is evident in the academic writing and professional writing where the development of ideas is intrinsically tied to engagement with the ideas and works of others.

For writers and speakers,

- citations provide a way to acknowledge the original authors or creators of a work

- Writers may use tools like Google Scholar to trace the evolution of an idea over time. This helps scholars situate a particular work in an intellectual or historical tradition. By reading widely and deeply into a subject, writers are better able to understand how writers develop ideas in response to other writers, researchers and theorists–and social or technological milieus.

- citations bolster arguments . They enable writers and speakers to draw from the findings of researchers, theorists, and practitioners to provide evidence for their claims and observations

- Students in academic and professionals in workplace settings may analyze citations to develop new hypotheses, theses , and research questions . Writers often develop their best ideas by studying the works of others — and then by debating their observations, speculations, theories and research findings.

- When scholars and scientists engage in problem solving, they invariably check the status of knowledge on a particular matter . They do this by tracing citations. Through tools like Google Scholar, writers can measure the impact of a particular work on the scholarly conversations.

For readers and listeners,

- citations provide the bibliographical information readers need to locate the original sources of information . This enables audiences to learn more about a topic –to learn who the current and past thought leaders are.

- citations stand as indicators of authority . Through them, readers can affirm that summarizes , paraphrases , or quotes are rooted in published literature — ideally peer-reviewed theory, research, and scholarship. This gives the reader confidence in the content’s place in the broader conversation of humankind.

- citations offer a window into the thoroughness of a writer’s or speaker’s work, showcasing the extent and depth of their inquiry. Correct citation, beyond its procedural importance, signifies respect for the originality and effort of others. Correct citation signifies professionalism and respect for copyright , academic integrity, and intellectual property rights . Correct citation enhances the credibility and authority of a document. It enhances the author’s ethos .

By engaging with citations, readers and listeners not only discern the integrity of the work but are also ushered into the grand dialogue of human thought and discovery.

Various academic disciplines adopt specific citation styles, such as APA , MLA , or Chicago. Though these styles differ in presentation, their primary aim remains steadfast: to honor academic integrity, copyright, and provide the audience with the information they need to locate the sources referenced in a text .

Related Concepts: Academic Dishonesty ; Archive ; Authority in Academic Writing ; Canon ; Copyright ; Discourse ; Hermeneutics ; Information Has Value ; Intellectual Property ; Paraphrase ; Plagiarism ; Quotation ; Scholarship as a Conversation ; Summary

Citation Enables Speakers & Writers to Appeal to Authority

Citations are not mere annotations in the margins of academic and professional writing . Beyond their role in acknowledging intellectual contributions, they possess an intrinsic rhetorical power: evoking authority .

Every discipline is marked by seminal works and figures that lay the bedrock, setting the foundational conversations which define the field. These are the authoritative figures and texts that anyone wishing to engage deeply with the discipline must grapple with. However, being educated isn’t just about acknowledging these giants. It’s about discerning the nuances of evolving conversations—understanding which debates are grounded in the discipline’s bedrock and which ones signal innovative shifts in understanding, opening doors to fresh insights about a topic.

Mastering the art of citation involves more than rote adherence to style guidelines. It’s an initiation into a discipline’s unique “way of seeing”—and also its inherent limitations. To cite effectively is to navigate and participate in these ongoing discourses, recognizing both their historical roots and their forward-looking trajectories.

Consider, for instance, the following luminaries who have not just added to but also significantly shaped their respective disciplines:

- Albert Einstein didn’t just add to physics; his theory of relativity transformed our perceptions of time, space, and the universe.

- Marie Curie’s research on radioactivity wasn’t a mere addition to medical science; it opened up entirely new avenues of exploration and treatment.

- Shakespeare’s influence isn’t limited to the plays and poems he authored; he reshaped the English language and set a benchmark in Western literary traditions.

- Sigmund Freud introduced concepts that forced the field to rethink its understanding of the human psyche, pushing psychology into new terrains of inquiry.

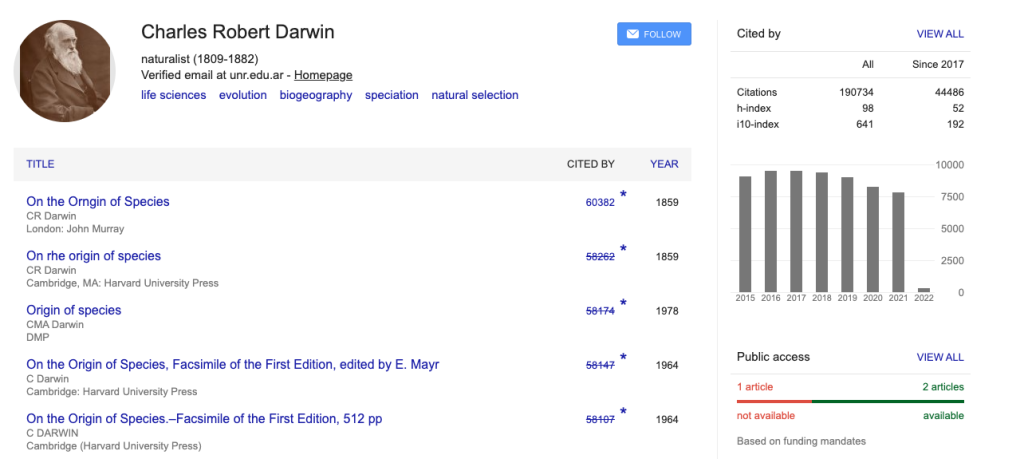

- Charles Darwin’s work isn’t just a theory among others; it’s a cornerstone of modern biology, redefining our comprehension of life’s diversity.

- Rosa Parks didn’t merely contribute to the civil rights movement; her acts of defiance ignited transformative episodes in the fight against racial segregation in the U.S.

When writers invoke these figures and their works, they’re not merely dropping names. They’re situating their arguments within a lineage of thought, anchoring their insights to established authority , while also potentially opening dialogues that push the boundaries of current knowledge.

Citing Well Signals Professionalism

Writers may be judged by their citations. Adhering to meticulous citation practices and judiciously referencing recognized experts conveys credibility , thoroughness, and professionalism . A correctly cited piece is a testament to an author’s commitment to rigorous research and an acknowledgment of the contributions that have paved the way for their own insights.

For readers, citations serve as markers of trust. They underline a writer’s professionalism and a reverence for the bedrock principles of academia: intellectual integrity, transparency, and the collaborative pursuit of knowledge . When an author cites properly, readers can more confidently engage with the content, assured of its roots in a larger, well-regarded body of scholarship.

On the flip side, a cavalier approach to citations can be detrimental. Misusing or omitting citations, exaggerating the implications of published research, or demonstrating confusion about the kind of truth claims a particular methodology allows can erode trust. Readers are adept at recognizing these missteps. They’ll likely scrutinize the validity, currency, relevance, authority, and overall purpose of a source, especially when citations are questionable. In such instances, a writer’s expertise and integrity come under scrutiny, undermining the impact and credibility of their work.

Citation Is Foundational to the Conversation of Humankind

At the heart of scholarship lies a vibrant, ever-evolving dialogue. Scholars continually engage in this discourse, drawing upon the wisdom of those before them while pushing boundaries with new insights. This conversation isn’t just an exchange of facts but a deep, transformative process of understanding, both dialectical in its nature and hermeneutical in its approach.

“We inherit not merely an ever-growing collection of facts but a perpetual dialogue, both within society and ourselves. This dialogue shapes every dimension of human effort.” (Oakeshott, 1962).

From the perspective of the scholarly conversation of humankind, citations function as signposts and records. They illuminate the path trodden by thinkers of the past and present the guidelines for future explorers. By engaging with citations, writers immerse themselves in the intellectual currents – the scholarly conversations — of their time. They discern which conversations are anchored in the bedrock of a discipline, defining its very essence, and which dialogues herald fresh insights and novel perspectives.

Today’s technological advancements, like Google Scholar, magnify the significance of citations. These platforms quantify the reverberations a publication has made in the scholarly community. For instance, as of January 2023, Charles Darwin’s work has been referenced by over 60,000 writers on Google Scholar.

Citation Functions as a Form of Social Capital

In textual research , basic research, and applied research , citations functions as a kind of “score keeping.” Scholars and researchers aim to contribute insights that will leave a lasting imprint on discussions within their domain. They seek to advance knowledge on a topic . Over time, consistently cited works can achieve a “canonical” status , signaling their enduring importance.

For academics and investigators in for-profit research labs, being the author of influential works or being frequently cited is not just an intellectual achievement: it serves as a form of social capital. Scholars who find their works frequently cited during their lifetimes see an expansion in their professional networks, leading to potentially greater opportunities. In many contexts, this recognition can translate into tangible benefits. Scholars who are recognized for their impactful contributions often find doors opening to grants, speaking engagements, and even financial opportunities like book royalties. Thus, citations not only validate research quality but can also elevate a scholar’s influence and value within their discipline.

Why Is Citation So Important to the Advancement of Scholarship & Human Knowledge?

In life, ideas matter. Texts matter. They are a form of property — of intellectual, social, and financial capital .

In turn, citation systems are instrumental in cataloging this wealth of knowledge, allowing scholars from past to present to acknowledge the intellectual contributions of others, while also facilitating the adherence to copyright or licensing protocols when necessary. They essentially serve as a method for society to measure intellectual contributions, affirming the rights and intellectual property of authors and inventors .

At its essence, citation celebrates the dialogic character of language, embodying the collaborative spirit inherent in research and scholarship . It grants writers and speakers the latitude to quote, paraphrase, or summarize the ideas and works of others, fostering a rich exchange of thoughts. The bibliographical details encapsulated in citations—such as the name of the author, title, publisher, and date—act as conduits, linking writers to a broader scholarly dialogue – to the conversation of humankind . This connection transcends temporal bounds, bridging discussions between past, present, and anticipatory contributions. thus facilitating a continuum of knowledge that is pivotal for academic and intellectual progression.

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

- Free Tools for Students

- Harvard Referencing Generator

Free Harvard Referencing Generator

Generate accurate Harvard reference lists quickly and for FREE, with MyBib!

🤔 What is a Harvard Referencing Generator?

A Harvard Referencing Generator is a tool that automatically generates formatted academic references in the Harvard style.

It takes in relevant details about a source -- usually critical information like author names, article titles, publish dates, and URLs -- and adds the correct punctuation and formatting required by the Harvard referencing style.

The generated references can be copied into a reference list or bibliography, and then collectively appended to the end of an academic assignment. This is the standard way to give credit to sources used in the main body of an assignment.

👩🎓 Who uses a Harvard Referencing Generator?

Harvard is the main referencing style at colleges and universities in the United Kingdom and Australia. It is also very popular in other English-speaking countries such as South Africa, Hong Kong, and New Zealand. University-level students in these countries are most likely to use a Harvard generator to aid them with their undergraduate assignments (and often post-graduate too).

🙌 Why should I use a Harvard Referencing Generator?

A Harvard Referencing Generator solves two problems:

- It provides a way to organise and keep track of the sources referenced in the content of an academic paper.

- It ensures that references are formatted correctly -- inline with the Harvard referencing style -- and it does so considerably faster than writing them out manually.

A well-formatted and broad bibliography can account for up to 20% of the total grade for an undergraduate-level project, and using a generator tool can contribute significantly towards earning them.

⚙️ How do I use MyBib's Harvard Referencing Generator?

Here's how to use our reference generator:

- If citing a book, website, journal, or video: enter the URL or title into the search bar at the top of the page and press the search button.

- Choose the most relevant results from the list of search results.

- Our generator will automatically locate the source details and format them in the correct Harvard format. You can make further changes if required.

- Then either copy the formatted reference directly into your reference list by clicking the 'copy' button, or save it to your MyBib account for later.

MyBib supports the following for Harvard style:

🍏 What other versions of Harvard referencing exist?

There isn't "one true way" to do Harvard referencing, and many universities have their own slightly different guidelines for the style. Our generator can adapt to handle the following list of different Harvard styles:

- Cite Them Right

- Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU)

- University of the West of England (UWE)

Daniel is a qualified librarian, former teacher, and citation expert. He has been contributing to MyBib since 2018.

Creative Writing Program Marks Three Decades of Growth, Diversity

By Luisa A. Igloria

2024: a milestone year which marks the 30 th anniversary of Old Dominion University’s MFA Creative Writing Program. Its origins can be said to go back to April 1978, when the English Department’s (now Professor Emeritus, retired) Phil Raisor organized the first “Poetry Jam,” in collaboration with Pulitzer prize-winning poet W.D. Snodgrass (then a visiting poet at ODU). Raisor describes this period as “ a heady time .” Not many realize that from 1978 to 1994, ODU was also the home of AWP (the Association of Writers and Writing Programs) until it moved to George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia.

The two-day celebration that was “Poetry Jam” has evolved into the annual ODU Literary Festival, a week-long affair at the beginning of October bringing writers of local, national, and international reputation to campus. The ODU Literary Festival is among the longest continuously running literary festivals nationwide. It has featured Rita Dove, Maxine Hong Kingston, Susan Sontag, Edward Albee, John McPhee, Tim O’Brien, Joy Harjo, Dorothy Allison, Billy Collins, Naomi Shihab Nye, Sabina Murray, Jane Hirshfield, Brian Turner, S.A. Cosby, Nicole Sealey, Franny Choi, Ross Gay, Adrian Matejka, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Ilya Kaminsky, Marcelo Hernandez Castillo, Jose Olivarez, and Ocean Vuong, among a roster of other luminaries. MFA alumni who have gone on to publish books have also regularly been invited to read.

From an initial cohort of 12 students and three creative writing professors, ODU’s MFA Creative Writing Program has grown to anywhere between 25 to 33 talented students per year. Currently they work with a five-member core faculty (Kent Wascom, John McManus, and Jane Alberdeston in fiction; and Luisa A. Igloria and Marianne L. Chan in poetry). Award-winning writers who made up part of original teaching faculty along with Raisor (but are now also either retired or relocated) are legends in their own right—Toi Derricotte, Tony Ardizzone, Janet Peery, Scott Cairns, Sheri Reynolds, Tim Seibles, and Michael Pearson. Other faculty that ODU’s MFA Creative Writing Program was privileged to briefly have in its ranks include Molly McCully Brown and Benjamín Naka-Hasebe Kingsley.

"What we’ve also found to be consistently true is how collegial this program is — with a lively and supportive cohort, and friendships that last beyond time spent here." — Luisa A. Igloria, Louis I. Jaffe Endowed Professor & University Professor of English and Creative Writing at Old Dominion University

Our student body is diverse — from all over the country as well as from closer by. Over the last ten years, we’ve also seen an increase in the number of international students who are drawn to what our program has to offer: an exciting three-year curriculum of workshops, literature, literary publishing, and critical studies; as well as opportunities to teach in the classroom, tutor in the University’s Writing Center, coordinate the student reading series and the Writers in Community outreach program, and produce the student-led literary journal Barely South Review . The third year gives our students more time to immerse themselves in the completion of a book-ready creative thesis. And our students’ successes have been nothing but amazing. They’ve published with some of the best (many while still in the program), won important prizes, moved into tenured academic positions, and been published in global languages. What we’ve also found to be consistently true is how collegial this program is — with a lively and supportive cohort, and friendships that last beyond time spent here.

Our themed studio workshops are now offered as hybrid/cross genre experiences. My colleagues teach workshops in horror, speculative and experimental fiction, poetry of place, poetry and the archive — these give our students so many more options for honing their skills. And we continue to explore ways to collaborate with other programs and units of the university. One of my cornerstone projects during my term as 20 th Poet Laureate of the Commonwealth was the creation of a Virginia Poets Database, which is not only supported by the University through the Perry Library’s Digital Commons, but also by the MFA Program in the form of an assistantship for one of our students. With the awareness of ODU’s new integration with Eastern Virginia Medical School (EVMS) and its impact on other programs, I was inspired to design and pilot a new 700-level seminar on “Writing the Body Fantastic: Exploring Metaphors of Human Corporeality.” In the fall of 2024, I look forward to a themed graduate workshop on “Writing (in) the Anthropocene,” where my students and I will explore the subject of climate precarity and how we can respond in our own work.

Even as the University and wider community go through shifts and change through time, the MFA program has grown with resilience and grace. Once, during the six years (2009-15) that I directed the MFA Program, a State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) university-wide review amended the guidelines for what kind of graduate student would be allowed to teach classes (only those who had already earned 18 or more graduate credits). Thus, two of our first-year MFA students at that time had to be given another assignment for their Teaching Assistantships. I thought of AWP’s hallmarks of an effective MFA program , which lists the provision of editorial and publishing experience to its students through an affiliated magazine or press — and immediately sought department and upper administration support for creating a literary journal. This is what led to the creation of our biannual Barely South Review in 2009.

In 2010, HuffPost and Poets & Writers listed us among “ The Top 25 Underrated Creative Writing MFA Programs ” (better underrated than overrated, right?) — and while our MFA Creative Writing Program might be smaller than others, we do grow good writers here. When I joined the faculty in 1998, I was excited by the high caliber of both faculty and students. Twenty-five years later, I remain just as if not more excited, and look forward to all the that awaits us in our continued growth.

This essay was originally published in the Spring 2024 edition of Barely South Review , ODU’s student-led literary journal. The University’s growing MFA in Creative Writing program connects students with a seven-member creative writing faculty in fiction, poetry, and nonfiction.

Enhance your college career by gaining relevant experience with the skills and knowledge needed for your future career. Discover our experiential learning opportunities.

Picture yourself in the classroom, speak with professors in your major, and meet current students.

From sports games to concerts and lectures, join the ODU community at a variety of campus events.

Kindlepreneur

Book Marketing for Self-Publishing Authors

Home / Book Writing / Author vs Writer: What’s the Difference?

Author vs Writer: What’s the Difference?

People often mix up the terms “author” and “writer”, but there is a difference. A writer is someone who wrote, but an author is someone who wrote books. There were many types of writers, and here, you’ll learn about what makes an author different from a writer, and how you can become one.

With this knowledge, you'll be able to better understand authorship and determine if your path is that of a writer or an author.

- What is the difference between a writer and an author.

- Who originates the ideas and owns the writing

- Whether your work is published under your name

- Whether you should be a writer or an author

- How to become an author

What is a Writer?

A writer is someone who engages in the act and process of writing. This is a broad definition that encompasses many types of writing. Essentially, if you spend time writing creatively, whether it's fiction, nonfiction, prose, poetry, scripts, blogs, or journaling, you can consider yourself a writer.

The key criteria is that you are actively involved in writing as an ongoing pursuit or hobby. You don't necessarily have to be published or make money from your writing to be called a writer.

Types of Writers

There are many different types of writers that fall under the broad definition above. Some of the most common include:

- Fiction writers – Writers who focus on fictional stories, novels, or other creative works. This includes genres like romance, sci-fi, fantasy, horror, historical fiction, and more.

- Nonfiction writers – Writers who create factual, informational, or journalistic works like biographies, memoirs, self-help books, news articles, and blogs.

- Freelance writers – Also known as commercial writers, freelancers are hired by companies, publishers, or individuals to create specific written content, like website copy, marketing materials, technical documentation, research reports, scripts, and more.

- Journalists – Writers who report on factual events and news for newspapers, magazines, websites, TV, or radio.

- Bloggers – Writers who create regular blog content focusing on a specific topic or niche.

- Screenwriters – Writers who create scripts and screenplays for television, movies, and digital productions.

- Content writers – Similar to freelance writers, content writers create written web content for businesses and websites.

- Academic writers – Writers who create scholarly books, papers, articles, and other content, usually within a specific academic discipline.

- Technical writers – Writers who create instruction guides, manuals, how-to guides, and other technical documentation.

- Copywriters – Writers who create advertising and marketing materials like brochures, websites, digital ads, commercials, and more.

So basically, a ‘writer’ is anyone who writes, no matter the genre, format, or industry.

Formatting Has Never Been Easier

Write and format professional books with ease. Never before has creating formatted books been easier.

What is an Author?

An author is a writer who originates ideas and content for a book or other literary work that is formally published. In other words, authors are published writers. Simply writing a manuscript does not make someone an author – it requires actual publication and distribution of the work.

Some key criteria that distinguish authors from general writers include:

- They compose original ideas, stories, and information for publication in book format or other literary formats.

- Their full work is published formally under their name, as the originator of the content.

- They typically own the copyright and intellectual property of the published work.

- There is an element of authority or expertise lent to being the named author of a published book or major literary work.

- For full-length book publications, most authors partner with a publisher who prints, markets, distributes, and sells the book.

So an author is someone who comes up with the ideas for a book, and it is published under their name, giving them the rights to the content.

What’s the Difference?

While there is overlap between writers and authors, and all authors consider themselves writers, there are some key differences that distinguish the two titles:

Who Originates the Ideas

- Writers may write up other people's ideas, rewrite content, or work from an assigned topic. For example, freelance writers are hired to write content for clients on various subjects.

- Authors are the original creators and originators of the ideas, content, and stories covered in their literary works. Their books come from their own minds and perspectives.

Who Owns the Writing?

- Writers usually write content that is owned or copyrighted by an employer or client. For example, freelancers who write website copy for a marketing firm don't own or have rights to that content.

- Authors own the full rights and copyrights to their published books and works, since they are the sole creator. There are some exceptions if rights are sold or transferred to a publisher.

Is Your Work Published Under Your Name?

- Writers may never see their name published or receive credit for written works. For example, ghostwriters or staff writers for companies.

- Authors are published under their own name and are publicly credited for their books and other literary creations. Their named authorship is key to their title.

When it comes to publication, authors have two main options: traditional publishing or self-publishing.

Traditional publishing involves submitting book proposals to publishing houses, who then contract and publish approved manuscripts. The publisher handles editing, distribution, marketing, and sales. The author receives an advance and royalties.

Self-publishing allows the author to publish their book independently by paying for editing, design, printing, and distribution themselves. The author retains full creative control and rights over their work. Popular self-publishing platforms include Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing, IngramSpark, and Draft2Digital.

Basically, an author credit is given to anyone who publishes a full literary work under their own name. The ideas and content have to be theirs in order for them to be considered the author of the book.

Should You Be an Author or a Writer?

So, how do you know which path is right for you? Here are a few tips:

Consider your motivation – Do you want to write for the joy of writing, or do you feel called to author and publish your own book? Writings fulfill the act itself while authors want to complete and distribute a major work.

Does originating ideas appeal to you? – Authors thrive on creating their own stories, worldviews, characters, and topics. If this suits you, authoring a book may be appealing.

Evaluate your commitment – Writing can be casual while authoring a book takes immense commitment. Are you excited by a major project and willing to spend months or years completing an entire manuscript?