Find Study Materials for

- Explanations

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

- Flashcards Create and find the best flashcards.

- Notes Create notes faster than ever before.

- Study Sets Everything you need for your studies in one place.

- Study Plans Stop procrastinating with our smart planner features.

- Nike Sweatshop Scandal

Nike is one of the largest athletic footwear and clothing companies in the world, but its labour practices have not always been ethical. Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the company was accused of using sweatshops to make activewear and shoes. Despite an initial slow response, the company eventually took measures to improve the working conditions of employees in its factories. This has allowed it to regain public trust and become a leading brand in the sportswear sector. Let's take a closer look at Nike's Sweatshop Scandal and how it has been resolved.

Create learning materials about Nike Sweatshop Scandal with our free learning app!

- Instand access to millions of learning materials

- Flashcards, notes, mock-exams and more

- Everything you need to ace your exams

- Business Case Studies

- Amazon Global Business Strategy

- Apple Change Management

- Apple Ethical Issues

- Apple Global Strategy

- Apple Marketing Strategy

- Ben and Jerrys CSR

- Bill And Melinda Gates Foundation

- Bill Gates Leadership Style

- Coca-Cola Business Strategy

- Disney Pixar Merger Case Study

- Enron Scandal

- Franchise Model McDonalds

- Google Organisational Culture

- Ikea Foundation

- Ikea Transnational Strategy

- Jeff Bezos Leadership Style

- Kraft Cadbury Takeover

- Mary Barra Leadership Style

- McDonalds Organisational Structure

- Netflix Innovation Strategy

- Nike Marketing Strategy

- Nivea Market Segmentation

- Nokia Change Management

- Organisation Design Case Study

- Oyo Franchise Model

- Porters Five Forces Apple

- Porters Five Forces Starbucks

- Porters Five Forces Walmart

- Pricing Strategy of Nestle Company

- Ryanair Strategic Position

- SWOT analysis of Cadbury

- Starbucks Ethical Issues

- Starbucks International Strategy

- Starbucks Marketing Strategy

- Susan Wojcicki Leadership Style

- Swot Analysis of Apple

- Tesco Organisational Structure

- Tesco SWOT Analysis

- Unilever Outsourcing

- Virgin Media O2 Merger

- Walt Disney CSR Programs

- Warren Buffett Leadership Style

- Zara Franchise Model

- Business Development

- Business Operations

- Change Management

- Corporate Finance

- Financial Performance

- Human Resources

- Influences On Business

- Intermediate Accounting

- Introduction to Business

- Managerial Economics

- Nature of Business

- Operational Management

- Organizational Behavior

- Organizational Communication

- Strategic Analysis

- Strategic Direction

Nike and sweatshop labour

Like other multinational companies, Nike outsources the production of sportswear and sneakers to developing economies to save costs, taking advantage of a cheap workforce. This has given birth to sweatshops - factories where workers are forced to work long hours at very low wages under abysmal working conditions.

Nike's sweatshops first appeared in Japan, then moved to cheaper labour countries such as South Korea, China, and Taiwan. As the economies of these countries developed, Nike switched to lower-cost suppliers in China, Indonesia, and Vietnam .

Nike's use of sweatshop dates back to the 1970s but wasn't brought to public attention until 1991 when Jeff Ballinger published a report detailing the appalling working conditions of garment workers at Nike's factories in Indonesia.

The report described the meagre wages that the factory workers received, only 14 cents per hour, barely enough to cover basic living costs. The disclosure aroused public anger, resulting in mass protests at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992. Despite this, Nike continued making its plans to expand Niketowns - fa cilities displaying a wide range of Nike-based services and experiences - which fuelled more resentment within consumers.

For more insight into how a company's external economic environment can impact its internal operations, take a look at our explanation on the Economic Environment .

Nike child labour

In addition to the sweatshop problem, Nike also got caught in the child labour scandal. In 1996, Life Magazine published an article featuring a photo of a young boy named Tariq from Pakistan, who was reportedly sewing Nike footballs for 60 cents a day .

From 2001 on, Nike started to audit its factories and prepared a report in which it concluded that it could not guarantee that its products would not be produced by children .

Nike's initial response

Nike initially denied its association with the practices, stating it had little control over the contracted factories and who they hired.

After the protests in 1992, the company took more concrete action by setting up a department to improve factory conditions. However, this didn't do much to resolve the problem. Disputes continued. Many Nike sweatshops still operated.

In 1997-1998, Nike faced more public backlash, causing the sportswear brand to lay off many workers.

How did Nike recover?

A major shift happened when CEO Phil Knight delivered a speech in May 1998. He admitted the existence of unfair labour practices in Nike's production facilities and promised to improve the situation by raising the minimum wage, and ensuring all factories had clean air.

In 1999, Nike's Fair Labor Association was established to protect workers' rights and monitor the Code of Conduct in Nike factories. Between 2002 and 2004, more than 600 factories were audited for occupational health and safety . In 2005, the company published a complete list of its factories along with a report detailing the working conditions and wages of workers at Nike's facilities. Ever since, Nike has been publishing annual reports about labour practices, showing transparency and sincere efforts to redeem past mistakes.

While the sweatshop issue is far from over, critics and activists have praised Nike. At least the company does not turn a blind eye to the problem anymore. Nike's efforts finally paid off as it slowly won back public trust and once again dominated the market.

It is important to note that these actions have had minimal effect on workers' conditions working for Nike. In the 2019 report by Tailored Wages, Nike cannot prove that minimum living wage is being paid to any workers. 6

Protection of workers' human rights

Nike's sweatshops undoubtedly violated human rights. Workers survive on a low minimum wage and are forced to work in an unsafe environment for long periods of time. However, since the Nike Sweatshop Scandal, many non-profit organisations have been set up to protect the rights of garment workers.

One example is Team Sweat, an organisation tracking and protesting Nike's illegal labour practices. It was founded in 2000 by Jim Keady with the goal of ending these injustices.

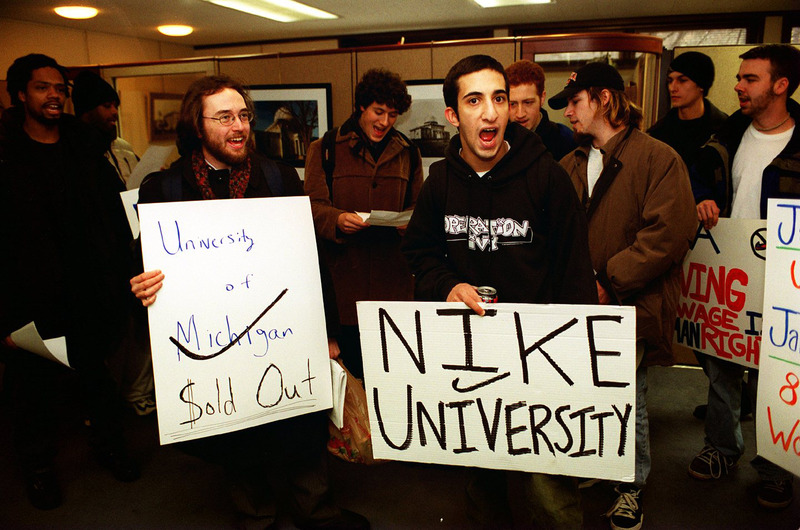

USAS is another US-based group formed by students to challenge oppressive practices. The organisation has started many projects to protect workers' rights, one of which is the Sweat-Free Campus Campaign . The campaign required all brands that make university names or logos. This was a major success, gathering enormous public support and causing Nike financial loss. To recover, the company had no choice but to improve the factory conditions and labour rights.

Nike's Corporate Social Responsibility

Since 2005, the company has been producing corporate social responsibility reports as part of its commitment to transparency.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a set of practices a business undertakes in order to contribute to society in a positive way .

Nike's CSR reports revealed the brand's continuous efforts to improve labour working conditions.

For example, FY20 Nike Impact Report, Nike made crucial points on how it protects workers' human rights. The solutions include:

Forbid underage employment and forced labour

Allow freedom of association (Forming of workers' union)

Prevent discrimination of all kind

Provide workers with fair compensation

Eliminate excessive overtime

In addition to labour rights, Nike aims to make a positive difference in the world through a wide range of sustainable practices:

Source materials for apparel and footwear from sustainable sources

Reduce carbon footprint and reach 100% renewable energy

Increase recycling and cut down on overall waste

Adopt new technology to decrease water use in the supply chain

Slowly, the company is distancing itself from the 'labour abuse' image and making a positive impact on the world. It aims to become both a profitable and an ethical company.

Nike sweatshop scandal timeline

1991 - Activist Jeff Ballinger publishes a report exposing low wages and poor working conditions among Indonesian Nike factories. Nike responds by instating its first factory codes of conduct.

1992 - In his article, Jeff Ballinger details an Indonesian worker who was abused by a Nike subcontractor, who paid the worker 14 cents an hour. He also documented other forms of exploitation towards workers at the company.

1996 - In response to the controversy around the use of child labour in its products, Nike created a department that focussed on improving the lives of factory workers.

1997 - Media outlets challenge the company's spokespersons. Andrew Young, an activist and diplomat, gets hired by Nike to investigate its labour practices abroad. His critics say that his report was soft on the company, despite his favourable conclusions.

1998 - Nike faces unrelenting criticism and weak demand. It had to start shedding workers and developing a new strategy. In response to widespread protests, CEO Phil Knight said that the company's products became synonymous with slavery and abusive labour conditions. Knight said:

"I truly believe the American consumer doesn't want to buy products made under abusive conditions"

Nike raised the minimum age of its workers and increased monitoring of overseas factories.

1999 - Nike launches the Fair Labor Association, a not-for-profit group that combines company and human rights representatives to establish a code of conduct and monitor labour conditions.

2002 - Between 2002 and 2004, the company carried out around 600 factory audits. These were mainly focused on problematic factories.

2004 - Human rights groups acknowledge that efforts to improve the working conditions of workers have been made, but many of the issues remain . Watchdog groups also noted that some of the worst abuses still occur.

2005 - Nike becomes the first major brand to publish a list of the factories it contracts to manufacture shoes and clothes. Nike's annual report details the conditions. It also acknowledges widespread issues in its south Asian factories.

2006 - T he company continues to publish its social responsibility reports and its commitments to its customers.

For many years, Nike's brand image has been associated with sweatshops. However, since the sweatshop scandal of the 1990s, the company has made a concerted efforts to reverse this negative image. It does so by being more transparent about labour practices while making a positive change in the world through Corporate Social Responsibility strategies. Nike's CSR strategies not only focus on labour but also other social and environmental aspects.

Nike Sweatshop Scandal - Key takeaways

Nike has been criticised for using sweatshops in emerging economies as a source of labour .

The Nike Sweatshop Scandal began in 1991 when Jeff Ballinger published a report detailing the appalling working conditions of garment workers at Nike's factory in Indonesia.

- Nike's initial response was to deny its association with unethical practices. However, under the influence of public pressure, the company was forced to take action to resolve cases of its unethical working practices.

- From 1999 to 2005, Nike performed factory audits and took many measures to improve labour practices.

- Since 2005, the company also published annual reports to be transparent about its labour working conditions.

- Nike continues to reinforce its ethical image through Corporate Social Responsibility strategies.

- Simon Birch, Sweat and Tears, The Guardian, 2000.

- Lara Robertson, How Ethical Is Nike, Good On You, 2020.

- Ashley Lutz, How Nike shed its sweatshop image to dominate the shoe industry, Business insider, 2015.

- Jack Meyer, History of Nike: Timeline and Facts, The Street, 2019.

- A History of Nike’s Changing Attitude to Sweatshops, Glass Clothing, 2018.

- Tailored Wages Report 2019, https://archive.cleanclothes.org/livingwage/tailoredwages

Flashcards inNike Sweatshop Scandal 30

what year was Nike founded?

What was the nike sweatshop scandal about?

Nike has been criticized for using sweatshops in Asia as a source of labour. The company was accused of engaging in abusive and verbal behaviour toward its workers.

Does nike sweatshop scandal involve human rights violations?

Yes. A report by the Washington Post in 2020 stated that Nike doesn't have evidence of a living wage for its workers. The same year, it was revealed that the company uses forced labor in factories.

What is the main reason Nike is considered unethical?

Nike has been criticized for using sweatshops in Asia as a source of labor. The company was accused of abusing its employees. In addition, some of the factories reportedly imposed conditions that severely affected their workers' restroom and water usage.

Was Nike involved in child labour?

In what year did Nike created the Fair Labour Association, which was created to oversee the company's 600 factories?

Learn with 30 Nike Sweatshop Scandal flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Nike Sweatshop Scandal

What was the Nike sweatshop scandal about?

Nike has been criticised for using sweatshops in emerging economies as a cheap source of labour that violated the human rights of the workers.

When was the Nike sweatshop scandal?

The Nike Sweatshop Scandal began in 1991 when Jeff Ballinger published a report detailing the appalling working conditions of garment workers at Nike's factory in Indonesia.

Does the Nike sweatshop scandal involve human rights violations?

Yes, the Nike sweatshop scandal involved human rights violations. Workers survive on a low minimum wage and are forced to work in an unsafe environment for long periods of time.

What is the main reason Nike is considered unethical?

The main reason Nike was considered unethical is Human rights violations of workers in its offshore factories.

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

StudySmarter Editorial Team

Team Nike Sweatshop Scandal Teachers

- 9 minutes reading time

- Checked by StudySmarter Editorial Team

Study anywhere. Anytime.Across all devices.

Create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our StudySmarter App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

SustainCase – Sustainability Magazine

- trending News

- Climate News

- Collections

- case studies

Case study: How Nike solved its sweatshop problem

With this article, we present actions Nike has taken through the years to solve its sweatshop problem, using information published in its GRI Standards-based CSR/ ESG/ Sustainability reports.

See what action Nike has taken through the years to solve its sweatshop problem

Subscribe for free and read the rest of this article

Please subscribe to the SustainCase Newsletter to keep up to date with the latest sustainability news and gain access to over 2000 case studies. These case studies demonstrate how companies are dealing responsibly with their most important impacts, building trust with their stakeholders (Identify > Measure > Manage > Change).

Already Subscribed? Type your email below and click submit

Nike is continuously tackling its most important environmental, economic and social impacts with the use of the GRI Standards for CSR/ ESG/ sustainability reporting: an all-round, complete, structured, and methodical approach used by 80% of the world’s 250 largest companies.

- Promoting worker-management dialogue: Nike took action to facilitate worker-management dialogue in contract factories through permanent ESH (Environment, Safety and Health ) committees, training both workers and management to engage in constructive dialogue.

- Directly intervening to protect workers’ rights: When workers’ rights are not adequately protected by others and Nike believes it can influence the outcome, it may directly intervene, often seeking advice from external stakeholders with expertise on a topic.

- Supporting transparency: Nike became the first company in its industry to publish online the names and addresses of all contract factories manufacturing Nike-brand products, constantly updating this list.

- Monitoring Nike and contract factories: In addition to regular management audits in factories, Nike carries out deeper studies called Management Audit Verifications (MAV), which are both an audit and verification in one tool. The MAV tool is focused on four core areas: hours of work, wages and benefits, labour relations and grievance systems.

- Compliance with legally-mandated work hours

- Use of overtime only when employees are fully compensated according to local law

- Informing employees at hiring if compulsory overtime is a condition of employment

- Regularly providing one full day off in every seven and requiring no more than 60 hours of work per week

- Setting industry-leading compliance standards: Contract factories in Nike’s supply chain are subject to strict compliance requirements, starting with risk analysis of the host country and Nike’s Code of Conduct. Additionally, Nike’s internal team of more than 150 trained experts monitors, amends and provides improvement tools to the factories. Nike regularly audits contract factories, with assessments taking the form of audit visits, both announced and unannounced, by internal and external parties, and works with accredited third parties, such as the Fair Labor Association (FLA), to carry out independent monitoring.

- Helping contract factories protect workers’ health and safety: Nike helps its contract factories put in place comprehensive HSE (Health, Safety and Environment) management systems which focus on the prevention, identification and elimination of hazards and risks to workers, expecting its contract factories to perform better than industry averages in injuries and lost-time accidents.

- Forbidding the use of child labour: Nike specifically and directly forbids the use of child labour in facilities contracted to manufacture its products. Nike’s Code of Conduct requires that workers must be at least 16 years old or past the national legal age of compulsory schooling and minimum working age, whichever is higher. In addition, Nike’s Code Leadership Standards include specific requirements on how suppliers should verify workers’ age prior to starting employment and actions a facility must take if a supplier violates Nike’s standards.

- Promoting workers’ freedom of association: Nike’s Code Leadership Standards contain detailed requirements on how suppliers must respect workers’ rights to freely associate, including prohibitions on interference with workers seeking to organise or carry out union activities.

How Nike conducts stakeholder engagement

Nike benefits from constructive guidance from a number of external stakeholders, including civil society organisations, industry, government, investors, consumers and others. To identify and better understand emerging sustainability issues Nike works with Ceres (a sustainability nonprofit organisation), convening an external stakeholder panel and carrying out multiple dialogues that guide the development of its approach to reporting and communication.

How Nike solved its sweatshop problem

It was only 20 years ago that Nike was facing child labour and sweatshop allegations, with consumers protesting outside Niketown stores. All this is hard to believe, given the steady stream of corporate social responsibility (CSR) accolades in the last 10 years.

In 1998, then-CEO Phil Knight promised change. The company struggled to put new policies in place and enforce them. In 2005, Nike published its first version of a CSR/ ESG/ Sustainability report – in which it detailed pay scales and working conditions in its factories and admitted continued problems – and took the dramatic step of publicly disclosing the names and addresses of contract factories producing Nike products – the first company in its industry to do so.

More recently, Nike made this information available on an Interactive Global Manufacturing Map ; there, you can click on a factory to see its name, number of workers, percentage of female and migrant workers and what’s made there. A major change from the days when Nike faced accusations of labour rights in its supply chain, it takes transparency to a whole new level.

Nike recognised its issues, demonstrated transparency and worked toward change – and, today, it is counted among CSR/ ESG/ Sustainability leaders.

Which Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been addressed?

The SDGs addressed in this case are:

- Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 : Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages

- Business theme: Occupational health and safety

- Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 : Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

- Business theme: Workplace violence and harassment

- Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 : Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

- Business theme: Occupational health and safety, Freedom of association and collective bargaining, Abolition of child labor, Elimination of forced or compulsory labor, Labor practices in the supply chain

- Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16 : Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels

- Business theme: Abolition of child labor, Labor practices in the supply chain

78% of the world’s 250 largest companies report in accordance with the GRI Standards

SustainCase was primarily created to demonstrate, through case studies, the importance of dealing with a company’s most important impacts in a structured way, with use of the GRI Standards. To show how today’s best-run companies are achieving economic, social and environmental success – and how you can too.

Research by well-recognised institutions is clearly proving that responsible companies can look to the future with optimism .

7 GRI sustainability disclosures get you started

Any size business can start taking sustainability action

GRI, IEMA, CPD Certified Sustainability courses (2-5 days): Live Online or Classroom (venue: London School of Economics)

- Exclusive FBRH template to begin reporting from day one

- Identify your most important impacts on the Environment, Economy and People

- Formulate in group exercises your plan for action. Begin taking solid, focused, all-round sustainability action ASAP.

- Benchmarking methodology to set you on a path of continuous improvement

See upcoming training dates.

References:

This article was compiled using an article from the links below. For the sake of readability, we did not use brackets or ellipses but made sure that the extra or missing words did not change the article’s meaning. If you would like to quote these written sources from the original please revert to the links below:

http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/jan/02/billion-dollar-companies-sustainability-green-giants-tesla-chipotle-ikea-nike-toyota-whole-foods

http://www.businessinsider.com/how-nike-solved-its-sweatshop-problem-2013-5

http://www.triplepundit.com/special/roi-of-sustainability/how-nike-embraced-csr-and-went-from-villain-to-hero/

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

Nike Sustainability and Labor Practices 2008-2013

The case discusses Nike’s sustainability and labor practices from 1998 to 2013, focusing on the successful steps Nike took up and down the supply chain and in its headquarters to make its products and processes more environmentally friendly, and the challenges and complexities it was still facing in its efforts to improve labor conditions. Nike’s labor practices were the subject of high profile public protests in the 1990s, and CEO Mark Parker said the company still had a lot of work to do in that area. The case also details how making sustainability a key part of the design process led Nike to develop more innovative and high-performing products, such as a breakthrough running shoe called the Flyknit, which was widely worn at the 2012 Olympics. Following protests in the late 1990s over unsafe working conditions, low wage rates, excessive overtime, restrictions on employee organizing, and negative environmental impacts, Nike began shifting from a reactive to a proactive mode. During the 15 years covered in this case, Nike made significant changes in its sustainability practices, including moving its Corporate Responsibility team much further upstream in the organization, where it could have a greater impact on decisions by providing input early in the process. The company also developed multiple indexes that measured its sustainability practices and those of its independent contract manufacturers. The indexes had metrics for measuring the relevant impacts of product waste, water, chemistry, labor, and energy. Nike’s critics said many labor issues had not been resolved, but Nike made progress in that area through collaboration with governments, NGOs and labor unions, and through management compliance trainings. If a contract factory did not score high enough on the company’s sustainability and labor ratings scales, Nike would impose sanctions on the factory or even drop it from the supply chain. These actions took Nike off the top of most activists’ target lists.

Learning Objective

The learning objective of the case is for students to understand how a large, high-profile global company is navigating the complexities of becoming more sustainable and improving labor practices.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2024 Awardees

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Just (Don't) Do It: Nike Case Study

Nike was not the only university supplier with labor issues, nor was it the only one to vocally oppose the university’s anti-sweatshop policies. However, due to its impressive role in American pop culture and a number of widely publicized factory scandals, Nike became a national symbol for the dangers of the sweatshop labor. On campus, Nike’s massive contract with Michigan athletics, one of the largest of any college in the country, made it an easy target for SOLE and others. Students made the company a focal point in many of their demonstrations.

Nike's relationship with the university was rocky at best. Starting with the University of Michigan adopting a strong code of conduct in 1999, Nike began years of negotiations to weaken anti-sweatshop protections and to mitigate the impact of the university's regulations on their business. The last straw was Michigan joining the WRC, and Nike decided to would rather end its contract than comply with a set of guidelines it considered unreasonable. While the university and Nike signed a new contract in 2001 with new protections for they company's workers, Nike continued to be a target for activists.

Michigan in the World features exhibitions of research conducted by undergraduate students about the history of the University of Michigan and its relationships beyond its borders.

Drag image here or click to upload

Nike and Sweatshop Labour

Nike child labour.

Nike's Initial Response

How Did Nike Recover?

Protection of Workers' Human Rights

Nike's Corporate Social Responsibility

Nike Sweatshop Scandal Timeline

What is nike sweatshop scandal: timeline & key issues.

Nike ranks among the top athletic footwear and apparel companies globally, though its labor practices have not always upheld ethical standards. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the company faced allegations of utilizing sweatshops in the production of activewear and footwear.

Following a delayed response initially, Nike implemented measures to enhance the working conditions for its factory workers. Consequently, the company managed to rebuild public confidence and establish itself as a prominent brand within the sports apparel industry. Let's delve into Nike's handling of the Sweatshop Scandal and its resolution.

Nike, similar to numerous other multinational corporations, delegates the manufacturing of athletic apparel and sneakers to developing economies to cut costs through utilizing an inexpensive labor force. Consequently, this strategy has resulted in the establishment of sweatshops - facilities where laborers are compelled to toil extended hours for meager pay amidst deplorable working conditions.

Nike initially established sweatshops in Japan, later relocating to countries with more affordable labor like South Korea, China, and Taiwan. As these nations' economies progressed, Nike transitioned to cheaper suppliers in China, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

While Nike has been utilizing sweatshops since the 1970s, public awareness heightened in 1991 after Jeff Ballinger revealed the harsh working conditions of Nike factory workers in Indonesia.

The report highlighted the meager wages of only 14 cents per hour, which were barely enough to cover basic living costs. This disclosure sparked public outrage, leading to mass protests at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992. Despite the backlash, Nike continued with its plans to expand Niketowns - facilities that showcase a wide range of Nike-based services and experiences - further fueling resentment among consumers.

Nike not only faced the sweatshop issue but also became entangled in the child labor controversy. Life Magazine disclosed in 1996 a story showcasing an image of a young boy named Tariq from Pakistan, who was said to be stitching Nike footballs for a daily wage of 60 cents.

From 2001 on, Nike started to audit its factories and prepared a report in which it concluded that it could not guarantee that its products would not be produced by children.

Nike's Initial Response

Nike initially disclaimed any connection to the practices, asserting it had limited control over the contracted factories and their hiring decisions.

Following the demonstrations in 1992, the establishment of a department aimed at enhancing factory conditions was the company's more tangible response. Nevertheless, this proved insufficient in addressing the issue as disputes persisted, with numerous Nike sweatshops remaining in operation.

Nike laid off many workers due to increased public backlash in 1997-1998.

CEO Phil Knight acknowledged the presence of unjust labor practices in Nike's production sites during his speech in May 1998. He pledged to enhance the circumstances by increasing the minimum wage and guaranteeing clean air in all factories.

In 1999, Nike's Fair Labor Association was established to protect workers' rights and monitor the Code of Conduct in Nike factories. From 2002 to 2004, over 600 factories underwent audits regarding occupational health and safety. In 2005, a comprehensive list of its factories was released by the company, accompanied by a report outlining the working conditions and wages of employees at Nike's facilities.

Since then, Nike has released yearly reports on labor practices, demonstrating transparency and genuine efforts to rectify previous errors.

Nike has been lauded by critics and activists for not ignoring the ongoing sweatshop issue. Its persistent efforts have led to the gradual regain of public trust and the reassertion of its market dominance.

It is important to note that these actions have had minimal effect on workers' conditions working for Nike. Nike is unable to demonstrate in the 2019 Tailored Wages report that the minimum living wage is being paid to any workers.

Protection of Workers' Human Rights

Nike's factories clearly infringed on human rights, as employees were paid poorly and subjected to extended hours in hazardous environments. Following the Nike Sweatshop Scandal, numerous non-profit groups have arisen to defend the rights of manufacturing workers.

Established in 2000 by Jim Keady, Team Sweat is a group that monitors and rallies against Nike's illegal labor practices, with the goal of stopping these wrongdoings.

USAS, a US student-formed group, aims to combat oppressive practices. They have initiated several initiatives advocating for workers' rights, such as the Sweat-Free Campus Campaign. This campaign mandated university-associated brands to adhere to specific guidelines. The initiative garnered significant public backing and impacted Nike's finances. In response, Nike had to boost factory conditions and labor rights to recuperate from the setback.

Nike's Corporate Social Responsibility

Since 2005, the company has been producing corporate social responsibility reports as part of its commitment to transparency.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a set of practices a business undertakes in order to contribute to society in a positive way.

Nike's CSR reports indicated the brand's ongoing endeavors to enhance labor working conditions.

For example, FY20 Nike Impact Report, Nike made crucial points on how it protects workers' human rights. The solutions include:

- Forbid underage employment and forced labour

- Allow freedom of association (Forming of workers' union)

- Prevent discrimination of all kind

- Provide workers with fair compensation

- Eliminate excessive overtime

In addition to labour rights, Nike aims to make a positive difference in the world through a wide range of sustainable practices:

- Source materials for apparel and footwear from sustainable sources

- Reduce carbon footprint and reach 100% renewable energy

- Increase recycling and cut down on overall waste

- Adopt new technology to decrease water use in the supply chain

The company is gradually shedding its reputation for 'labour abuse' and striving to create a beneficial global influence. Its goal is to be a profitable and ethical organization.

1991 - Jeff Ballinger, an activist, releases a report revealing low pay and unfavorable working conditions in Indonesian Nike factories. As a result, Nike puts into effect its initial factory code of conduct.

1992 - Jeff Ballinger's article recounts the mistreatment of an Indonesian worker by a Nike subcontractor, paying the worker a mere 14 cents per hour. Ballinger also chronicled additional instances of worker exploitation within the company.

1996 - In response to the controversy around the use of child labour in its products, Nike created a department that focused on improving the lives of factory workers.

1997 - Media organizations question the company's representatives. Nike recruits activist and diplomat Andrew Young to examine its overseas labor practices. Despite his positive findings, some detractors contend that his assessment of the company was too lenient.

1998 - Nike faces unrelenting criticism and weak demand. It had to start shedding workers and developing a new strategy. In light of extensive protests, CEO Phil Knight remarked that the company's products had become linked with slavery and exploitative labor practices.

"I truly believe the American consumer doesn't want to buy products made under abusive conditions"

Nike raised the minimum age of its workers and increased monitoring of overseas factories.

1999 - Nike launches the Fair Labor Association, a not-for-profit group that combines company and human rights representatives to establish a code of conduct and monitor labour conditions.

2002 - Between 2002 and 2004, the company carried out around 600 factory audits. These were mainly focused on problematic factories.

2004 - Human rights organizations recognize that while there have been attempts to enhance the working conditions of workers, many issues persist. Monitoring groups have also observed that some of the most severe abuses continue to take place.

2005 - Nike is the initial prominent brand to reveal a roster of the factories it employs to produce footwear and apparel. The company's yearly report outlines the circumstances, recognizing prevalent problems in its south Asian factories.

2006 - The company continues to publish its social responsibility reports and its commitments to its customers.

Nike's brand was long linked with sweatshops, but since the 1990s scandal, the company has worked hard to change this perception. By increasing transparency in labor practices and implementing Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives, Nike aims to improve its image and make a difference in the world. In addition to labor practices, Nike's CSR efforts also address social and environmental concerns.

Related Posts

What is lanugage acquisition device: characteristics & examples.

Explore the concept of Chomsky's Language Acquisition Device (LAD) at GeniusTutor. Understand its role, mechanism, and importance in language learning.

What Is Possibilism in Human Geography?

Explore the concept of possibilism in human geography with GeniusTutor. Discover how humans navigate and adapt to environmental constraints through possibilism.

Understanding Traditional Economies

Traditional economies are systems where economic decisions are deeply rooted in cultural traditions and heritage. Learn more about traditional economics with GeniusTutor.

What Is Hoyt Sector Model?

A comprehensive look at the Hoyt Sector Model developed during the 1930s, its foundational role in urban planning, and the collaborative efforts that shaped modern cities.

Find Study Materials for

- Explanations

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Textbook Solutions

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

- Flashcards Create and find the best flashcards.

- Notes Create notes faster than ever before.

- Study Sets Everything you need for your studies in one place.

- Study Plans Stop procrastinating with our smart planner features.

- Nike Sweatshop Scandal

Nike is one of the largest athletic footwear and clothing companies in the world, but its labour practices have not always been ethical. Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the company was accused of using sweatshops to make activewear and shoes. Despite an initial slow response, the company eventually took measures to improve the working conditions of employees in its factories. This has allowed it to regain public trust and become a leading brand in the sportswear sector. Let's take a closer look at Nike's Sweatshop Scandal and how it has been resolved.

Create learning materials about Nike Sweatshop Scandal with our free learning app!

- Instand access to millions of learning materials

- Flashcards, notes, mock-exams and more

- Everything you need to ace your exams

- Business Case Studies

- Amazon Global Business Strategy

- Apple Change Management

- Apple Ethical Issues

- Apple Global Strategy

- Apple Marketing Strategy

- Ben and Jerrys CSR

- Bill And Melinda Gates Foundation

- Bill Gates Leadership Style

- Coca-Cola Business Strategy

- Disney Pixar Merger Case Study

- Enron Scandal

- Franchise Model McDonalds

- Google Organisational Culture

- Ikea Foundation

- Ikea Transnational Strategy

- Jeff Bezos Leadership Style

- Kraft Cadbury Takeover

- Mary Barra Leadership Style

- McDonalds Organisational Structure

- Netflix Innovation Strategy

- Nike Marketing Strategy

- Nivea Market Segmentation

- Nokia Change Management

- Organisation Design Case Study

- Oyo Franchise Model

- Porters Five Forces Apple

- Porters Five Forces Starbucks

- Porters Five Forces Walmart

- Pricing Strategy of Nestle Company

- Ryanair Strategic Position

- SWOT analysis of Cadbury

- Starbucks Ethical Issues

- Starbucks International Strategy

- Starbucks Marketing Strategy

- Susan Wojcicki Leadership Style

- Swot Analysis of Apple

- Tesco Organisational Structure

- Tesco SWOT Analysis

- Unilever Outsourcing

- Virgin Media O2 Merger

- Walt Disney CSR Programs

- Warren Buffett Leadership Style

- Zara Franchise Model

- Business Development

- Business Operations

- Change Management

- Corporate Finance

- Financial Performance

- Human Resources

- Influences On Business

- Intermediate Accounting

- Introduction to Business

- Managerial Economics

- Nature of Business

- Operational Management

- Organizational Behavior

- Organizational Communication

- Strategic Analysis

- Strategic Direction

Nike and sweatshop labour

Like other multinational companies, Nike outsources the production of sportswear and sneakers to developing economies to save costs, taking advantage of a cheap workforce. This has given birth to sweatshops - factories where workers are forced to work long hours at very low wages under abysmal working conditions.

Nike's sweatshops first appeared in Japan, then moved to cheaper labour countries such as South Korea, China, and Taiwan. As the economies of these countries developed, Nike switched to lower-cost suppliers in China, Indonesia, and Vietnam .

Nike's use of sweatshop dates back to the 1970s but wasn't brought to public attention until 1991 when Jeff Ballinger published a report detailing the appalling working conditions of garment workers at Nike's factories in Indonesia.

The report described the meagre wages that the factory workers received, only 14 cents per hour, barely enough to cover basic living costs. The disclosure aroused public anger, resulting in mass protests at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992. Despite this, Nike continued making its plans to expand Niketowns - fa cilities displaying a wide range of Nike-based services and experiences - which fuelled more resentment within consumers.

For more insight into how a company's external economic environment can impact its internal operations, take a look at our explanation on the Economic Environment .

Nike child labour

In addition to the sweatshop problem, Nike also got caught in the child labour scandal. In 1996, Life Magazine published an article featuring a photo of a young boy named Tariq from Pakistan, who was reportedly sewing Nike footballs for 60 cents a day .

From 2001 on, Nike started to audit its factories and prepared a report in which it concluded that it could not guarantee that its products would not be produced by children .

Nike's initial response

Nike initially denied its association with the practices, stating it had little control over the contracted factories and who they hired.

After the protests in 1992, the company took more concrete action by setting up a department to improve factory conditions. However, this didn't do much to resolve the problem. Disputes continued. Many Nike sweatshops still operated.

In 1997-1998, Nike faced more public backlash, causing the sportswear brand to lay off many workers.

How did Nike recover?

A major shift happened when CEO Phil Knight delivered a speech in May 1998. He admitted the existence of unfair labour practices in Nike's production facilities and promised to improve the situation by raising the minimum wage, and ensuring all factories had clean air.

In 1999, Nike's Fair Labor Association was established to protect workers' rights and monitor the Code of Conduct in Nike factories. Between 2002 and 2004, more than 600 factories were audited for occupational health and safety . In 2005, the company published a complete list of its factories along with a report detailing the working conditions and wages of workers at Nike's facilities. Ever since, Nike has been publishing annual reports about labour practices, showing transparency and sincere efforts to redeem past mistakes.

While the sweatshop issue is far from over, critics and activists have praised Nike. At least the company does not turn a blind eye to the problem anymore. Nike's efforts finally paid off as it slowly won back public trust and once again dominated the market.

It is important to note that these actions have had minimal effect on workers' conditions working for Nike. In the 2019 report by Tailored Wages, Nike cannot prove that minimum living wage is being paid to any workers. 6

Protection of workers' human rights

Nike's sweatshops undoubtedly violated human rights. Workers survive on a low minimum wage and are forced to work in an unsafe environment for long periods of time. However, since the Nike Sweatshop Scandal, many non-profit organisations have been set up to protect the rights of garment workers.

One example is Team Sweat, an organisation tracking and protesting Nike's illegal labour practices. It was founded in 2000 by Jim Keady with the goal of ending these injustices.

USAS is another US-based group formed by students to challenge oppressive practices. The organisation has started many projects to protect workers' rights, one of which is the Sweat-Free Campus Campaign . The campaign required all brands that make university names or logos. This was a major success, gathering enormous public support and causing Nike financial loss. To recover, the company had no choice but to improve the factory conditions and labour rights.

Nike's Corporate Social Responsibility

Since 2005, the company has been producing corporate social responsibility reports as part of its commitment to transparency.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a set of practices a business undertakes in order to contribute to society in a positive way .

Nike's CSR reports revealed the brand's continuous efforts to improve labour working conditions.

For example, FY20 Nike Impact Report, Nike made crucial points on how it protects workers' human rights. The solutions include:

Forbid underage employment and forced labour

Allow freedom of association (Forming of workers' union)

Prevent discrimination of all kind

Provide workers with fair compensation

Eliminate excessive overtime

In addition to labour rights, Nike aims to make a positive difference in the world through a wide range of sustainable practices:

Source materials for apparel and footwear from sustainable sources

Reduce carbon footprint and reach 100% renewable energy

Increase recycling and cut down on overall waste

Adopt new technology to decrease water use in the supply chain

Slowly, the company is distancing itself from the 'labour abuse' image and making a positive impact on the world. It aims to become both a profitable and an ethical company.

Nike sweatshop scandal timeline

1991 - Activist Jeff Ballinger publishes a report exposing low wages and poor working conditions among Indonesian Nike factories. Nike responds by instating its first factory codes of conduct.

1992 - In his article, Jeff Ballinger details an Indonesian worker who was abused by a Nike subcontractor, who paid the worker 14 cents an hour. He also documented other forms of exploitation towards workers at the company.

1996 - In response to the controversy around the use of child labour in its products, Nike created a department that focussed on improving the lives of factory workers.

1997 - Media outlets challenge the company's spokespersons. Andrew Young, an activist and diplomat, gets hired by Nike to investigate its labour practices abroad. His critics say that his report was soft on the company, despite his favourable conclusions.

1998 - Nike faces unrelenting criticism and weak demand. It had to start shedding workers and developing a new strategy. In response to widespread protests, CEO Phil Knight said that the company's products became synonymous with slavery and abusive labour conditions. Knight said:

"I truly believe the American consumer doesn't want to buy products made under abusive conditions"

Nike raised the minimum age of its workers and increased monitoring of overseas factories.

1999 - Nike launches the Fair Labor Association, a not-for-profit group that combines company and human rights representatives to establish a code of conduct and monitor labour conditions.

2002 - Between 2002 and 2004, the company carried out around 600 factory audits. These were mainly focused on problematic factories.

2004 - Human rights groups acknowledge that efforts to improve the working conditions of workers have been made, but many of the issues remain . Watchdog groups also noted that some of the worst abuses still occur.

2005 - Nike becomes the first major brand to publish a list of the factories it contracts to manufacture shoes and clothes. Nike's annual report details the conditions. It also acknowledges widespread issues in its south Asian factories.

2006 - T he company continues to publish its social responsibility reports and its commitments to its customers.

For many years, Nike's brand image has been associated with sweatshops. However, since the sweatshop scandal of the 1990s, the company has made a concerted efforts to reverse this negative image. It does so by being more transparent about labour practices while making a positive change in the world through Corporate Social Responsibility strategies. Nike's CSR strategies not only focus on labour but also other social and environmental aspects.

Nike Sweatshop Scandal - Key takeaways

Nike has been criticised for using sweatshops in emerging economies as a source of labour .

The Nike Sweatshop Scandal began in 1991 when Jeff Ballinger published a report detailing the appalling working conditions of garment workers at Nike's factory in Indonesia.

- Nike's initial response was to deny its association with unethical practices. However, under the influence of public pressure, the company was forced to take action to resolve cases of its unethical working practices.

- From 1999 to 2005, Nike performed factory audits and took many measures to improve labour practices.

- Since 2005, the company also published annual reports to be transparent about its labour working conditions.

- Nike continues to reinforce its ethical image through Corporate Social Responsibility strategies.

- Simon Birch, Sweat and Tears, The Guardian, 2000.

- Lara Robertson, How Ethical Is Nike, Good On You, 2020.

- Ashley Lutz, How Nike shed its sweatshop image to dominate the shoe industry, Business insider, 2015.

- Jack Meyer, History of Nike: Timeline and Facts, The Street, 2019.

- A History of Nike’s Changing Attitude to Sweatshops, Glass Clothing, 2018.

- Tailored Wages Report 2019, https://archive.cleanclothes.org/livingwage/tailoredwages

Flashcards inNike Sweatshop Scandal 30

what year was Nike founded?

What was the nike sweatshop scandal about?

Nike has been criticized for using sweatshops in Asia as a source of labour. The company was accused of engaging in abusive and verbal behaviour toward its workers.

Does nike sweatshop scandal involve human rights violations?

Yes. A report by the Washington Post in 2020 stated that Nike doesn't have evidence of a living wage for its workers. The same year, it was revealed that the company uses forced labor in factories.

What is the main reason Nike is considered unethical?

Nike has been criticized for using sweatshops in Asia as a source of labor. The company was accused of abusing its employees. In addition, some of the factories reportedly imposed conditions that severely affected their workers' restroom and water usage.

Was Nike involved in child labour?

In what year did Nike created the Fair Labour Association, which was created to oversee the company's 600 factories?

Learn with 30 Nike Sweatshop Scandal flashcards in the free Vaia app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Nike Sweatshop Scandal

What was the Nike sweatshop scandal about?

Nike has been criticised for using sweatshops in emerging economies as a cheap source of labour that violated the human rights of the workers.

When was the Nike sweatshop scandal?

The Nike Sweatshop Scandal began in 1991 when Jeff Ballinger published a report detailing the appalling working conditions of garment workers at Nike's factory in Indonesia.

Does the Nike sweatshop scandal involve human rights violations?

Yes, the Nike sweatshop scandal involved human rights violations. Workers survive on a low minimum wage and are forced to work in an unsafe environment for long periods of time.

What is the main reason Nike is considered unethical?

The main reason Nike was considered unethical is Human rights violations of workers in its offshore factories.

Vaia is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

Vaia Editorial Team

Team Nike Sweatshop Scandal Teachers

- 9 minutes reading time

- Checked by Vaia Editorial Team

Study anywhere. Anytime.Across all devices.

Create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of Vaia.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our Vaia App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

Privacy Overview

- Resources +

- Daily Links

- Subscriptions

- Mission & Values

- Editor-in-Chief

Image: Nike

Sweatshops Almost Killed Nike in the 1990s, Now There are Modern Slavery Laws

One of the biggest threats to a retailer’s reputation is an allegation of involvement in slavery, human trafficking, or child labor. ask nike. in the 1990s, the portland-based sportswear giant was plagued with damning reports that its global supply chain was being ....

September 27, 2019 - By TFL

Case Documentation

One of the biggest threats to a retailer’s reputation is an allegation of involvement in slavery, human trafficking, or child labor. Ask Nike. In the 1990s, the Portland-based sportswear giant was plagued with damning reports that its global supply chain was being supported by child labor in places like Cambodia and Pakistan, with minors stitching soccer balls and other products as many as seven days a week for up to 16 hours a day. All the while, sweatshop conditions were running rampant in factories Nike maintained contracts with, and minimum wage and overtime laws were being flouted with regularity.

The backlash against Nike was so striking that it served to tarnish the then-30 year old company’s image and negatively affect its bottom line. “Sales were dropping and Nike was being portrayed in the media as a company that was willing to exploit workers and deprive them of the basic wage needed to sustain themselves in an effort to expand profits,” according to Stanford University research.

That was not the case according to Nike’s chairman and chief executive at the time Phil Knight, who told the New York Times in 1998 that he “truthfully [did not] think that there has been a material impact on Nike sales by the human rights attacks,” and pointed instead, to “the financial crisis in Asia, where the company had been expanding sales aggressively, and its failure to recognize a shifting consumer preference for hiking shoes.”

Yet, the company was, nonetheless, forced to spend the next decade cleaning up its act in order to hold on to – and in some cases, win back – consumers, from overhauling its supply chain oversight efforts to include independent monitoring and audits to releasing public-facing vows to “root out underage workers and require overseas manufacturers of its wares to meet strict United States health and safety standards.”

It is critical to note that Nike took hits for its nefarious labor practices long before consumers were readily learning about and connecting with brands on social media, and during a time when retailers’ supply chains were generally less expansive than they are today. Fast forward to 2019 and with the rise of digital media and social media, and the larger trend towards cause-oriented consumerism, paired with the increasingly complicated and multi-national nature of corporate entities’ supply chains, the stakes are significantly higher than they were in the 1990s.

The demands and the level of risk at play is exacerbated by the fact that shoppers, particularly of the millennial type, are actively calling on fashion brands and retailers to be transparent in terms of how and where their products are made. But even more than consumer-driven calls for clarity and principled activity, in many jurisdictions, the law requires it. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the Modern Slavery Act of 2015 requires commercial entities that have a global turnover above £36 million ($43.5 million) to publicly file an annual slavery and trafficking statement, highlighting what steps – if any – they are taking to combat trafficking and slavery in their operations and supply chains.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., California passed the Transparency in Supply Chains Act in January 2012, thereby requiring retailers and manufacturers with global revenues that exceed $100 million and which do business in California (a low bar given the sheer size of California’s economy and the sweeping business ties that come about as a result of e-commerce operations) to publicly disclose the degree to which they are addressing forced labor and human trafficking in their global manufacturing networks.

Two years later, the Federal Business Supply Chain Transparency on Trafficking and Slavery Bill was introduced to the House of Representatives. The bill proposed required all companies with worldwide annual sales exceeding $100 million, and which are currently required to file annual reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission, are to disclose what measures, if any, they have taken to identify and address conditions of forced labor, slavery, human trafficking and child labor within their supply chains, either in the U.S. or abroad.