Self-Paced Courses : Explore American history with top historians at your own time and pace!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

Historical Context: The Global Effect of World War I

By steven mintz.

A recent list of the hundred most important news stories of the twentieth century ranked the onset of World War I eighth. This is a great error. Just about everything that happened in the remainder of the century was in one way or another a result of World War I, including the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, World War II, the Holocaust, and the development of the atomic bomb. The Great Depression, the Cold War, and the collapse of European colonialism can also be traced, at least indirectly, to the First World War.

World War I killed more people--more than 9 million soldiers, sailors, and flyers and another 5 million civilians--involved more countries--28--and cost more money--$186 billion in direct costs and another $151 billion in indirect costs--than any previous war in history. It was the first war to use airplanes, tanks, long range artillery, submarines, and poison gas. It left at least 7 million men permanently disabled.

World War I probably had more far-reaching consequences than any other proceeding war. Politically, it resulted in the downfall of four monarchies--in Russia in 1917, in Austria-Hungary and Germany in 1918, and in Turkey in 1922. It contributed to the Bolshevik rise to power in Russia in 1917 and the triumph of fascism in Italy in 1922. It ignited colonial revolts in the Middle East and in Southeast Asia.

Economically, the war severely disrupted the European economies and allowed the United States to become the world's leading creditor and industrial power. The war also brought vast social consequences, including the mass murder of Armenians in Turkey and an influenza epidemic that killed over 25 million people worldwide.

Few events better reveal the utter unpredictability of the future. At the dawn of the 20th century, most Europeans looked forward to a future of peace and prosperity. Europe had not fought a major war for 100 years. But a belief in human progress was shattered by World War I, a war few wanted or expected. At any point during the five weeks leading up to the outbreak of fighting the conflict might have been averted. World War I was a product of miscalculation, misunderstanding, and miscommunication.

No one expected a war of the magnitude or duration of World War I. At first the armies relied on outdated methods of communication, such as carrier pigeons. The great powers mobilized more than a million horses. But by the time the conflict was over, tanks, submarines, airplane-dropped bombs, machine guns, and poison gas had transformed the nature of modern warfare. In 1918, the Germans fired shells containing both tear gas and lethal chlorine. The tear gas forced the British to remove their gas masks; the chlorine then scarred their faces and killed them.

In a single day at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, 100,000 British troops plodded across no man's land into steady machine-gun fire from German trenches a few yards away. Some 60,000 were killed or wounded. At the end of the battle, 419,654 British men were killed, missing, or wounded.Four years of war killed a million troops from the British Empire, 1.5 million troops from the Hapsburg Empire, 1.7 million French troops, 1.7 million Russians, and 2 million German troops. The war left a legacy of bitterness that contributed to World War II twenty-one years later.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

The Consequences of World War I

Political and Social Effects of the War to End All Wars

Imperial War Museum/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

A New Great Power

Socialism rises to the world stage, the collapse of central and eastern european empires, nationalism transforms and complicates europe, the myths of victory and failure.

- The Largest Loss: A 'Lost Generation'

- M.A., Medieval Studies, Sheffield University

- B.A., Medieval Studies, Sheffield University

World War I was fought on battlefields throughout Europe between 1914 and 1918 . It involved human slaughter on a previously unprecedented scale—and its consequences were enormous. The human and structural devastation left Europe and the world greatly changed in almost all facets of life, setting the stage for political convulsions throughout the remainder of the century.

Before its entry into World War I, the United States of America was a nation of untapped military potential and growing economic might. But the war changed the United States in two important ways: the country's military was turned into a large-scale fighting force with the intense experience of modern war, a force that was clearly equal to that of the old Great Powers; and the balance of economic power began to shift from the drained nations of Europe to America.

However, the dreadful toll taken by the war led U.S. politicians to retreat from the world and return to a policy of isolationism. That isolation initially limited the impact of America's growth, which would only truly come to fruition in the aftermath of World War II. This retreat also undermined the League of Nations and the emerging new political order.

The collapse of Russia under the pressure of total warfare allowed socialist revolutionaries to seize power and turn communism, one of the world’s growing ideologies, into a major European force. While the global socialist revolution that Vladimir Lenin believed was coming never happened, the presence of a huge and potentially powerful communist nation in Europe and Asia changed the balance of world politics.

Germany's politics initially tottered toward joining Russia, but eventually pulled back from experiencing a full Leninist change and formed a new social democracy. This would come under great pressure and fail from the challenge of Germany's right, whereas Russia's authoritarian regime after the tsarists lasted for decades.

The German, Russian, Turkish, and Austro-Hungarian Empires all fought in World War I, and all were swept away by defeat and revolution, although not necessarily in that order. The fall of Turkey in 1922 from a revolution stemming directly from the war, as well as that of Austria-Hungary, was probably not that much of a surprise: Turkey had long been regarded as the sick man of Europe, and vultures had circled its territory for decades. Austria-Hungary appeared close behind.

But the fall of the young, powerful, and growing German Empire, after the people revolted and the Kaiser was forced to abdicate, came as a great shock. In their place came a rapidly changing series of new governments, ranging in structure from democratic republics to socialist dictatorships.

Nationalism had been growing in Europe for decades before World War I began, but the war's aftermath saw a major rise in new nations and independence movements. Part of this was a result of Woodrow Wilson’s isolationist commitment to what he called "self-determination." But part of it was also a response to the destabilization of old empires, which nationalists viewed as an opportunity to declare new nations.

The key region for European nationalism was Eastern Europe and the Balkans, where Poland, the three Baltic States, Czechoslovakia, the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes , and others emerged. But nationalism conflicted hugely with the ethnic makeup of this region of Europe, where many different nationalities and ethnicities sometimes lived in tension with one another. Eventually, internal conflicts stemming from new self-determination by national majorities arose from disaffected minorities who preferred the rule of neighbors.

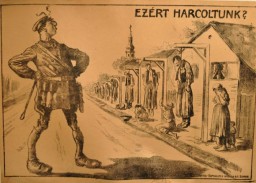

German commander Erich Ludendorff suffered a mental collapse before he called for an armistice to end the war, and when he recovered and discovered the terms he had signed onto, he insisted Germany refuse them, claiming the army could fight on. But the new civilian government overruled him, as once peace had been established there was no way to keep the army fighting. The civilian leaders who overruled Ludendorff became scapegoats for both the army and Ludendorff himself.

Thus began, at the very close of the war, the myth of the undefeated German army being "stabbed in the back" by liberals, socialists, and Jews who had damaged the Weimar Republic and fueled the rise of Hitler. That myth came directly from Ludendorff setting up the civilians for the fall. Italy didn’t receive as much land as it had been promised in secret agreements, and Italian right-wingers exploited this to complain of a "mutilated peace."

In contrast, in Britain, the successes of 1918 which had been won partly by their soldiers were increasingly ignored, in favor of viewing the war and all war as a bloody catastrophe. This affected their response to international events in the 1920s and 1930s; arguably, the policy of appeasement was born from the ashes of World War I.

The Largest Loss: A 'Lost Generation'

While it is not strictly true that a whole generation was lost—and some historians have complained about the term—eight million people died during World War I, which was perhaps one in eight of the combatants. In most of the Great Powers, it was hard to find anyone who had not lost someone to the war. Many other people had been wounded or shell-shocked so badly they killed themselves, and these casualties are not reflected in the figures.

- 5 Key Causes of World War I

- World War I Timeline From 1914 to 1919

- Causes of World War I and the Rise of Germany

- The Major Alliances of World War I

- The Causes and War Aims of World War One

- World War I Introduction and Overview

- The Fourteen Points of Woodrow Wilson's Plan for Peace

- The Countries Involved in World War I

- Key Historical Figures of World War I

- World War I: A Battle to the Death

- The German Revolution of 1918 – 19

- The US Economy in World War I

- World War I's Mitteleuropa

- World War I: Opening Campaigns

- How the Treaty of Versailles Contributed to Hitler's Rise

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

World War I Changed America and Transformed Its Role in International Relations

So why don't we pay more attention to it.

—Library of Congress

The entry of the United States into World War I changed the course of the war, and the war, in turn, changed America. Yet World War I receives short shrift in the American consciousness.

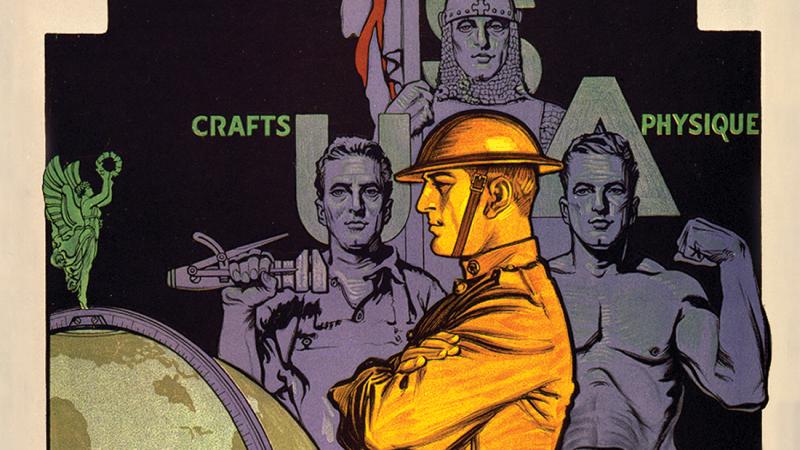

Recruiting poster for the U.S. Army by Herbert Paus.

Detail of a recruiting poster for YWCA by Ernest Hamlin Baker.

The American Expeditionary Forces arrived in Europe in 1917 and helped turn the tide in favor of Britain and France, leading to an Allied victory over Germany and Austria in November 1918. By the time of the armistice, more than four million Americans had served in the armed forces and 116,708 had lost their lives. The war shaped the writings of Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos. It helped forge the military careers of Dwight D. Eisenhower, George S. Patton, and George C. Marshall. On the home front, millions of women went to work, replacing the men who had shipped off to war, while others knitted socks and made bandages. For African-American soldiers, the war opened up a world not bound by America’s formal and informal racial codes.

And we are still grappling with one of the major legacies of World War I: the debate over America’s role in the world. For three years, the United States walked the tightrope of neutrality as President Woodrow Wilson opted to keep the country out of the bloodbath consuming Europe. Even as Germany’s campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic put American sailors and ships in jeopardy, the United States remained aloof. But after the Zimmermann telegram revealed Germany’s plans to recruit Mexico to attack the United States if it did not remain neutral, Americans were ready to fight.

In April 1917, President Wilson stood before Congress and said, “The world must be made safe for democracy.” With those words, he asked for a declaration of war, which Congress gave with gusto. For the first time in its history, the United States joined a coalition to fight a war not on its own soil or of its own making, setting a precedent that would be invoked repeatedly over the next century.

“For most Americans, going to war in 1917 was about removing the German threat to the U.S. homeland,” says Michael S. Neiberg, professor of history at the U.S. Army War College. “But after the war, Wilson developed a much more expansive vision to redeem the sin of war through the founding of a new world order, which created controversy and bitterness in the United States.”

The burden of sending men off to die weighed on Wilson’s conscience. It was one reason why he proposed the creation of the League of Nations, an international body based on collective security. But joining the League required the United States to sacrifice a measure of sovereignty. When judged against the butcher’s bill of this war, Wilson thought it was a small price to pay. Others, like Wilson’s longtime nemesis Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, believed that the United States should be free to pursue its own interests and not be beholden to an international body. America hadn’t fought a war only to relinquish its newfound stature as a military power.

As soldiers returned home and the victory parades faded, the fight over the League of Nations turned bitter. The sense of accomplishment quickly evaporated. “Then came the Depression (a direct result of the war) and another global crisis,” says Neiberg. “All of that made memory of World War I a difficult thing for Americans to engage with after about 1930.”

Even as the world has changed, the positions staked out by Wilson and Lodge have not evolved much over the past one hundred years. When new storm clouds gathered in Europe during the 1930s, Lodge’s argument was repurposed by isolationists as “America First,” a phrase that has come back into vogue as yet another example of the war’s enduring influence. “The war touched everything around the globe. Our entire world was shaped by it, even if we do not always make the connections,” Neiberg says.

Historian and writer A. Scott Berg emphatically agrees. “I think World War I is the most underrecognized significant event of the last several centuries. The stories from this global drama—and its larger-than-life characters—are truly the stuff of Greek tragedy and are of Biblical proportion; and modern America’s very identity was forged during this war.”

A biographer of Wilson and Charles Lindbergh, Berg has now cast his eye as an editor across the rich corpus of contemporaneous writing to produce World War I and America , a nearly one-thousand-page book of letters, speeches, diary entries, newspaper reports, and personal accounts. This new volume from Library of America starts with the New York Times story of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in July 1914 and concludes with an excerpt from John Dos Passos’s novel 1919 . In between, the voices of soldiers, politicians, nurses, diplomats, journalists, suffragettes, and intellectuals ask questions that are still with us.

“What is America’s role in the world? Are our claims to moral leadership abroad undercut by racial injustice at home? What do we owe those who serve in our wars?” asks Max Rudin, Library of America’s publisher. With 2017 marking the one-hundredth anniversary of America's entry into the war, the moment seemed ripe to revisit a conflict whose ghosts still haunt the nation. “It offered an opportunity to raise awareness about a generation of American writers that cries out to be better known,” says Rudin.

The volume shows off familiar names in surprising places. Nellie Bly and Edith Wharton report from the front lines. Henry Morgenthau Sr., the ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, files increasingly terrifying reports on the Armenian genocide. As Teddy Roosevelt leads the fight for American intervention, Jane Addams and Emma Goldman question the aims of the war. Writing from Italy, Ernest Hemingway complains to his family about being wounded. While Wilson and Lodge fight over American sovereignty, Ezra Pound expresses his disillusionment and grief in verse.

We also meet Floyd Gibbons, a Chicago Tribune crime reporter. Before the war he covered plenty of shootings, but “I could never learn from the victims what the precise feeling was as the piece of lead struck.” He found out in June 1918 at Belleau Wood when a German bullet found him—“the lighted end of a cigarette touched me in the fleshy part of my upper left arm.” A second bullet also found his shoulder, spawning a large burning sensation. “And then the third one struck me. . . . It sounded to me like some one had dropped a glass bottle into a porcelain bathtub. A barrel of whitewash tipped over and it seemed that everything in the world turned white.” The third bullet had found his left eye.

Stepping into an operating theater with Mary Borden, the Chicago heiress who established hospitals in France and Belgium, the smell of blood and death almost leaps off the page. “We send our men up the broken road between bushes of barbed wire and they come back to us, one by one, two by two in ambulances, lying on stretchers. They lie on their backs on the stretchers and are pulled out of the ambulances as loaves of bread are pulled out of the oven.” As a wounded soldier is laid out, “we conspire against his right to die. We experiment with his bones, his muscles, his sinews, his blood. We dig into the yawning mouths of his wounds. Helpless openings, they let us into the secret places of his body.”

When the American Expeditionary Forces shipped off to Europe, so too did approximately 16,500 women. They worked as clerks, telephone operators, and nurses; they also ran canteens that served meals to soldiers and offered a respite from battle. “These women often had complex motivations, such as a desire for adventure or professional advancement, and often witnessed more carnage than male soldiers, creating unacknowledged problems with PTSD when they returned home,” says Jennifer Keene, professor of history at Chapman University.

Of course, most women experienced the war stateside, where they tended victory gardens and worked to produce healthy meals from meager rations. They volunteered for the Red Cross and participated in Liberty Loan drives. As Willa Cather learned when she decamped from New York to Red Cloud, Nebraska, in the summer of 1918, the war could be consuming. “In New York the war was one of many subjects people talked about; but in Omaha, Lincoln, in my own town, and the other towns along the Republican Valley, and over in the north of Kansas, there was nothing but the war.”

In the Library of America volume, W. E. B. Du Bois, who, in the wake of Booker T. Washington’s death, assumed the mantle of spokesman for the black community, provides another take. From the beginning, Du Bois saw the war as grounded in the colonial rivalries and aspirations of the European belligerents.

Chad Williams, associate professor of African and Afro-American Studies at Brandeis University, says Du Bois was ahead of his time. “His writings also vividly illuminated the tensions between the professed democratic aims of the Allies—and the United States in particular—and the harsh realities of white supremacy, domestically and globally, for black people. Du Bois hoped that by supporting the American war effort and encouraging African-American patriotism, this tension could be reconciled. He was ultimately—and tragically—wrong.”

Along with Du Bois’s commentary, there are reports on the race riots in East St. Louis and Houston in 1917. Such incidents prompted James Weldon Johnson to cast aside sentimentality and answer the question, “Why should a Negro fight?”

“America is the American Negro’s country,” he wrote. “He has been here three hundred years; that is, about two hundred years longer than most of the white people.”

The U.S. Army shunted African-American soldiers into segregated units and issued them shovels more often than rifles. Some, however, fought alongside the French as equals, prompting questions about their treatment by their own country. African-American soldiers came home as citizens of the world with questions about their place in American society. “Understanding how the war impacted black people and the importance of this legacy is endlessly fascinating and, given our current times, extremely relevant,” says Williams.

To accompany its World War I volume, Library of America has launched a nationwide program, featuring scholars, to foster discussion about the war and its legacy. One hundred twenty organizations, from libraries to historical societies, are hosting events that involve veterans, their families, and their communities.

“There are veterans of recent conflicts in every community in America for whom the experiences and issues raised by World War I are very immediate,” says Rudin. “We all have something to learn from that.”

“Every war is distinct, and yet every war has almost eerie commonalities with wars past,” says Phil Klay, author of Redeployment , a collection of short stories about his service in Iraq that won the National Book Award. “I don’t think veterans have a unique authority in these discussions, but our personal experiences do inevitably infuse our reading. In my case, I find myself relentlessly drawn to pull lessons for the future from these readings, as the moral stakes of war have a visceral feel for me.”

For community programs, Library of America developed a slimmer version of its volume, World War I and America, while adding introductory essays and discussion questions. Keene, Neiberg, and Williams, along with Edward Lengel, served as editors. “There is truly not one part of the nation that was untouched by the war,” says Williams. “This project has the potential to remind people of its far-reaching significance and perhaps uncover new stories about the American experience in the war that we have not yet heard.”

Berg echoes the sentiment. “I hope audiences will appreciate the presence of World War I in our lives today—whether it is our economy, race relations, women’s rights, xenophobia, free speech, or the foundation of American foreign policy for the last one hundred years: They all have their roots in World War I.”

Meredith Hindley is a senior writer for Humanities .

Funding information

Library of America received $500,000 from NEH for nationwide library programs, a traveling exhibition, a website, and a publication of an anthology exploring how World War I reshaped American lives. For more information about the project, visit ww1america.org

SUBSCRIBE FOR HUMANITIES MAGAZINE PRINT EDITION Browse all issues Sign up for HUMANITIES Magazine newsletter

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português do Brasil

Featured Content

Find topics of interest and explore encyclopedia content related to those topics

Find articles, photos, maps, films, and more listed alphabetically

For Teachers

Recommended resources and topics if you have limited time to teach about the Holocaust

Explore the ID Cards to learn more about personal experiences during the Holocaust

Timeline of Events

Explore a timeline of events that occurred before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Introduction to the Holocaust

- Antisemitism

- How Many People did the Nazis Murder?

- Book Burning

- German Invasion of Western Europe, May 1940

- Voyage of the St. Louis

- Genocide of European Roma (Gypsies), 1939–1945

- The Holocaust and World War II: Key Dates

- Liberation of Nazi Camps

World War I: Aftermath

World war i, treaty of versailles.

- Weimar Germany

- Great Depression

- Nazi rise to power

This content is available in the following languages

The undermining of democracy in germany.

In the years following World War I , there was spiraling hyperinflation of the German currency (Reichsmark) by 1923. The causes included the burdensome reparations imposed after World War I, coupled with a general inflationary period in Europe in the 1920s (another direct result of a materially catastrophic war). This hyperinflationary period combined with the effects of the Great Depression (beginning in 1929) to seriously undermine the stability of the German economy, wiping out the personal savings of the middle class and spurring massive unemployment.

Economic chaos increased social unrest and destabilized the fragile Weimar Republic. "Weimar Republic" is the name given to the German government between the end of the Imperial period (1918) and the beginning of Nazi Germany (1933).

View Aftermath of World War I and the Rise of Nazism, 1918–1933 .

Efforts of the western European powers to marginalize Germany undermined and isolated its democratic leaders. Many Germans felt that Germany's prestige should be regained through remilitarization and expansion.

The social and economic upheaval that followed World War I gave rise to many radical right wing parties in Weimar Germany . The harsh provisions of the Treaty of Versailles led many in the general population to believe that Germany had been "stabbed in the back" by the "November criminals." By "November Criminals" they meant those who had helped to form the new Weimar government and broker the peace which Germans had so desperately wanted, but which had ended so disastrously in the Versailles Treaty.

Many Germans forgot that they had applauded the fall of the emperor (the Kaiser), had initially welcomed parliamentary democratic reform, and had rejoiced at the armistice. They recalled only that the German Left—Socialists, Communists, and Jews, in common imagination—had surrendered German honor to a disgraceful peace when no foreign armies had even set foot on German soil. This Dolchstosslegende (stab-in-the-back legend) was initiated and fanned by retired German wartime military leaders, who, well aware in 1918 that Germany could no longer wage war, had advised the Kaiser to sue for peace. It helped to further discredit German socialist and liberal circles who felt most committed to maintain Germany's fragile democratic experiment.

Vernunftsrepublikaner ("republicans by reason"), individuals like the historian Friedrich Meinecke and Nobel prize-winning author Thomas Mann, had at first resisted democratic reform. They now felt compelled to support the Weimar Republic as the least worst alternative. They tried to steer their compatriots away from polarization to the radical Left and Right. The German nationalist Right promised to revise the Versailles Treaty through force if necessary, and such promises gained traction in respectable circles. Meanwhile, there was fear of an imminent Communist threat following the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and short-lived Communist revolutions or coups in Hungary (Bela Kun) and in Germany itself (e.g., the Sparticist Uprising). This fear shifted German political sentiment decidedly toward right-wing causes.

Agitators from the political left served heavy prison sentences for inspiring political unrest. On the other hand, radical rightwing activists like Adolf Hitler , whose Nazi Party had attempted to depose the government of Bavaria and commence a "national revolution" in the November 1923 Beer Hall Putsch , served only nine months of a five year prison sentence for treason—which was a capital offense. During the prison sentence he wrote his political manifesto, Mein Kampf (My Struggle).

The difficulties imposed by social and economic unrest following World War I and its severe peace terms, along with the raw fear of the potential for a Communist takeover in the German middle classes, worked to undermine pluralistic democratic solutions in Weimar Germany. These fears and challenges also increased public longing for more authoritarian direction, a kind of leadership which German voters ultimately and unfortunately found in Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist Party. Similar conditions benefited rightwing authoritarian and totalitarian systems in eastern Europe as well, beginning with the losers of World War I, and eventually raised levels of tolerance for and acquiescence in violent antisemitism and discrimination against national minorities throughout the region.

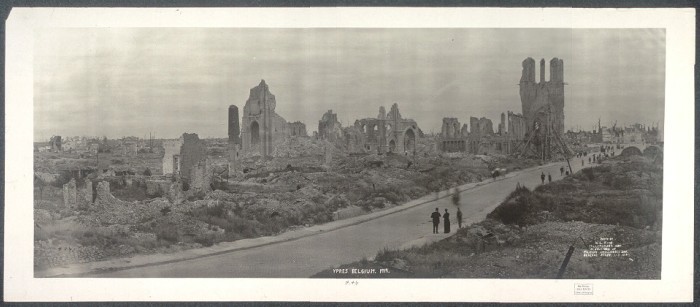

Cultural Despair

Finally, the destruction and catastrophic loss of life during World War I led to what can best be described as a cultural despair in many former combatant nations. Disillusionment with international and national politics and a sense of distrust in political leaders and government officials spread throughout the consciousness of a public which had witnessed the ravages of a devastating four-year conflict. Most European countries had lost virtually a generation of their young men.

While some writers like German author Ernst Jünger glorified the violence of war and the conflict's national context in his 1920 work Storm of Steel (Stahlgewittern), it was the vivid and realistic account of trench warfare portrayed in Erich Maria Remarque 's 1929 masterpiece All Quiet on the Western Front (Im Westen nichts Neues) which captured the experience of frontline troops and expressed the alienation of the "lost generation" who returned from war and found themselves unable to adapt to peacetime and tragically misunderstood by a home front population who had not seen the horrors of war firsthand.

In some circles this detachment and disillusionment with politics and conflict fostered an increase in pacifist sentiment. In the United States public opinion favored a return to isolationism ; such popular sentiment was at the root of the US Senate's refusal to ratify the Versailles Treaty and approve US membership in President Wilson's own proposed League of Nations. For a generation of Germans, this social alienation and political disillusionment was captured in German author Hans Fallada's Little Man, What Now? (Kleiner Mann, was nun?), the story of a German "everyman," caught up in the turmoil of economic crisis and unemployment, and equally vulnerable to the calls of the radical political Left and Right. Fallada's 1932 novel accurately portrayed the Germany of his time: a country immersed in economic and social unrest and polarized at the opposite ends of its political spectrum.

Many of the causes of this disorder had their roots in World War I and its aftermath. The path which Germany took would lead to a still more destructive war in the years to come.

Series: World War I

World War I: Treaties and Reparations

World War I and its Aftermath: Key Dates

Adolf Hitler and World War I: 1913–1919

Antisemitism in History: World War I

World War I and the Armenian Genocide

Series: the weimar republic.

The Weimar Republic

Paul von Hindenburg

Beer Hall Putsch (Munich Putsch)

Nazi Party Platform

Adolf Hitler

The Police in the Weimar Republic

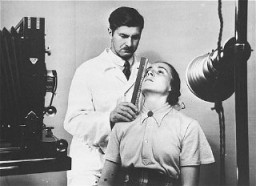

Science as Salvation: Weimar Eugenics, 1919–1933

What conditions, ideologies, and ideas made the Holocaust possible?

Switch series, critical thinking questions.

What difficulties does the government of a defeated nation face? At the conclusion of hostilities, what arrangements or support should be provided for the defeated nation?

What obligations do the victors and the world community have to the defeated enemy, if any?

Compare and contrast the treatment of Germany after WWI and after WWII, as well as the nation of Japan after WWII.

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies and the Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

World War I

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 10, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

World War I, also known as the Great War, started in 1914 after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria. His murder catapulted into a war across Europe that lasted until 1918. During the four-year conflict, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire (the Central Powers) fought against Great Britain, France, Russia, Italy, Romania, Canada, Japan and the United States (the Allied Powers). Thanks to new military technologies and the horrors of trench warfare, World War I saw unprecedented levels of carnage and destruction. By the time the war was over and the Allied Powers had won, more than 16 million people—soldiers and civilians alike—were dead.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Tensions had been brewing throughout Europe—especially in the troubled Balkan region of southeast Europe—for years before World War I actually broke out.

A number of alliances involving European powers, the Ottoman Empire , Russia and other parties had existed for years, but political instability in the Balkans (particularly Bosnia, Serbia and Herzegovina) threatened to destroy these agreements.

The spark that ignited World War I was struck in Sarajevo, Bosnia, where Archduke Franz Ferdinand —heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire—was shot to death along with his wife, Sophie, by the Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip on June 28, 1914. Princip and other nationalists were struggling to end Austro-Hungarian rule over Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Great War

The two-night event The Great War begins Monday, May 27 at 8/7c and streams the next day.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand set off a rapidly escalating chain of events: Austria-Hungary , like many countries around the world, blamed the Serbian government for the attack and hoped to use the incident as justification for settling the question of Serbian nationalism once and for all.

Kaiser Wilhelm II

Because mighty Russia supported Serbia, Austria-Hungary waited to declare war until its leaders received assurance from German leader Kaiser Wilhelm II that Germany would support their cause. Austro-Hungarian leaders feared that a Russian intervention would involve Russia’s ally, France, and possibly Great Britain as well.

On July 5, Kaiser Wilhelm secretly pledged his support, giving Austria-Hungary a so-called carte blanche, or “blank check” assurance of Germany’s backing in the case of war. The Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary then sent an ultimatum to Serbia, with such harsh terms as to make it almost impossible to accept.

World War I Begins

Convinced that Austria-Hungary was readying for war, the Serbian government ordered the Serbian army to mobilize and appealed to Russia for assistance. On July 28, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and the tenuous peace between Europe’s great powers quickly collapsed.

Within a week, Russia, Belgium, France, Great Britain and Serbia had lined up against Austria-Hungary and Germany, and World War I had begun.

The Western Front

According to an aggressive military strategy known as the Schlieffen Plan (named for its mastermind, German Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen ), Germany began fighting World War I on two fronts, invading France through neutral Belgium in the west and confronting Russia in the east.

On August 4, 1914, German troops crossed the border into Belgium. In the first battle of World War I, the Germans assaulted the heavily fortified city of Liege , using the most powerful weapons in their arsenal—enormous siege cannons—to capture the city by August 15. The Germans left death and destruction in their wake as they advanced through Belgium toward France, shooting civilians and executing a Belgian priest they had accused of inciting civilian resistance.

First Battle of the Marne

In the First Battle of the Marne , fought from September 6-9, 1914, French and British forces confronted the invading German army, which had by then penetrated deep into northeastern France, within 30 miles of Paris. The Allied troops checked the German advance and mounted a successful counterattack, driving the Germans back to the north of the Aisne River.

The defeat meant the end of German plans for a quick victory in France. Both sides dug into trenches , and the Western Front was the setting for a hellish war of attrition that would last more than three years.

Particularly long and costly battles in this campaign were fought at Verdun (February-December 1916) and the Battle of the Somme (July-November 1916). German and French troops suffered close to a million casualties in the Battle of Verdun alone.

HISTORY Vault: World War I Documentaries

Stream World War I videos commercial-free in HISTORY Vault.

World War I Books and Art

The bloodshed on the battlefields of the Western Front, and the difficulties its soldiers had for years after the fighting had ended, inspired such works of art as “ All Quiet on the Western Front ” by Erich Maria Remarque and “ In Flanders Fields ” by Canadian doctor Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae . In the latter poem, McCrae writes from the perspective of the fallen soldiers:

Published in 1915, the poem inspired the use of the poppy as a symbol of remembrance.

Visual artists like Otto Dix of Germany and British painters Wyndham Lewis, Paul Nash and David Bomberg used their firsthand experience as soldiers in World War I to create their art, capturing the anguish of trench warfare and exploring the themes of technology, violence and landscapes decimated by war.

The Eastern Front

On the Eastern Front of World War I, Russian forces invaded the German-held regions of East Prussia and Poland but were stopped short by German and Austrian forces at the Battle of Tannenberg in late August 1914.

Despite that victory, Russia’s assault forced Germany to move two corps from the Western Front to the Eastern, contributing to the German loss in the Battle of the Marne.

Combined with the fierce Allied resistance in France, the ability of Russia’s huge war machine to mobilize relatively quickly in the east ensured a longer, more grueling conflict instead of the quick victory Germany had hoped to win under the Schlieffen Plan .

Russian Revolution

From 1914 to 1916, Russia’s army mounted several offensives on World War I’s Eastern Front but was unable to break through German lines.

Defeat on the battlefield, combined with economic instability and the scarcity of food and other essentials, led to mounting discontent among the bulk of Russia’s population, especially the poverty-stricken workers and peasants. This increased hostility was directed toward the imperial regime of Czar Nicholas II and his unpopular German-born wife, Alexandra.

Russia’s simmering instability exploded in the Russian Revolution of 1917, spearheaded by Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks , which ended czarist rule and brought a halt to Russian participation in World War I.

Russia reached an armistice with the Central Powers in early December 1917, freeing German troops to face the remaining Allies on the Western Front.

America Enters World War I

At the outbreak of fighting in 1914, the United States remained on the sidelines of World War I, adopting the policy of neutrality favored by President Woodrow Wilson while continuing to engage in commerce and shipping with European countries on both sides of the conflict.

Neutrality, however, it was increasingly difficult to maintain in the face of Germany’s unchecked submarine aggression against neutral ships, including those carrying passengers. In 1915, Germany declared the waters surrounding the British Isles to be a war zone, and German U-boats sunk several commercial and passenger vessels, including some U.S. ships.

Widespread protest over the sinking by U-boat of the British ocean liner Lusitania —traveling from New York to Liverpool, England with hundreds of American passengers onboard—in May 1915 helped turn the tide of American public opinion against Germany. In February 1917, Congress passed a $250 million arms appropriations bill intended to make the United States ready for war.

Germany sunk four more U.S. merchant ships the following month, and on April 2 Woodrow Wilson appeared before Congress and called for a declaration of war against Germany.

Gallipoli Campaign

With World War I having effectively settled into a stalemate in Europe, the Allies attempted to score a victory against the Ottoman Empire, which entered the conflict on the side of the Central Powers in late 1914.

After a failed attack on the Dardanelles (the strait linking the Sea of Marmara with the Aegean Sea), Allied forces led by Britain launched a large-scale land invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula in April 1915. The invasion also proved a dismal failure, and in January 1916 Allied forces staged a full retreat from the shores of the peninsula after suffering 250,000 casualties.

Did you know? The young Winston Churchill, then first lord of the British Admiralty, resigned his command after the failed Gallipoli campaign in 1916, accepting a commission with an infantry battalion in France.

British-led forces also combated the Ottoman Turks in Egypt and Mesopotamia , while in northern Italy, Austrian and Italian troops faced off in a series of 12 battles along the Isonzo River, located at the border between the two nations.

Battle of the Isonzo

The First Battle of the Isonzo took place in the late spring of 1915, soon after Italy’s entrance into the war on the Allied side. In the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, also known as the Battle of Caporetto (October 1917), German reinforcements helped Austria-Hungary win a decisive victory.

After Caporetto, Italy’s allies jumped in to offer increased assistance. British and French—and later, American—troops arrived in the region, and the Allies began to take back the Italian Front.

World War I at Sea

In the years before World War I, the superiority of Britain’s Royal Navy was unchallenged by any other nation’s fleet, but the Imperial German Navy had made substantial strides in closing the gap between the two naval powers. Germany’s strength on the high seas was also aided by its lethal fleet of U-boat submarines.

After the Battle of Dogger Bank in January 1915, in which the British mounted a surprise attack on German ships in the North Sea, the German navy chose not to confront Britain’s mighty Royal Navy in a major battle for more than a year, preferring to rest the bulk of its naval strategy on its U-boats.

The biggest naval engagement of World War I, the Battle of Jutland (May 1916) left British naval superiority on the North Sea intact, and Germany would make no further attempts to break an Allied naval blockade for the remainder of the war.

World War I Planes

World War I was the first major conflict to harness the power of planes. Though not as impactful as the British Royal Navy or Germany’s U-boats, the use of planes in World War I presaged their later, pivotal role in military conflicts around the globe.

At the dawn of World War I, aviation was a relatively new field; the Wright brothers took their first sustained flight just eleven years before, in 1903. Aircraft were initially used primarily for reconnaissance missions. During the First Battle of the Marne, information passed from pilots allowed the allies to exploit weak spots in the German lines, helping the Allies to push Germany out of France.

The first machine guns were successfully mounted on planes in June of 1912 in the United States, but were imperfect; if timed incorrectly, a bullet could easily destroy the propeller of the plane it came from. The Morane-Saulnier L, a French plane, provided a solution: The propeller was armored with deflector wedges that prevented bullets from hitting it. The Morane-Saulnier Type L was used by the French, the British Royal Flying Corps (part of the Army), the British Royal Navy Air Service and the Imperial Russian Air Service. The British Bristol Type 22 was another popular model used for both reconnaissance work and as a fighter plane.

Dutch inventor Anthony Fokker improved upon the French deflector system in 1915. His “interrupter” synchronized the firing of the guns with the plane’s propeller to avoid collisions. Though his most popular plane during WWI was the single-seat Fokker Eindecker, Fokker created over 40 kinds of airplanes for the Germans.

The Allies debuted the Handley-Page HP O/400, the first two-engine bomber, in 1915. As aerial technology progressed, long-range heavy bombers like Germany’s Gotha G.V. (first introduced in 1917) were used to strike cities like London. Their speed and maneuverability proved to be far deadlier than Germany’s earlier Zeppelin raids.

By the war’s end, the Allies were producing five times more aircraft than the Germans. On April 1, 1918, the British created the Royal Air Force, or RAF, the first air force to be a separate military branch independent from the navy or army.

Second Battle of the Marne

With Germany able to build up its strength on the Western Front after the armistice with Russia, Allied troops struggled to hold off another German offensive until promised reinforcements from the United States were able to arrive.

On July 15, 1918, German troops launched what would become the last German offensive of the war, attacking French forces (joined by 85,000 American troops as well as some of the British Expeditionary Force) in the Second Battle of the Marne . The Allies successfully pushed back the German offensive and launched their own counteroffensive just three days later.

After suffering massive casualties, Germany was forced to call off a planned offensive further north, in the Flanders region stretching between France and Belgium, which was envisioned as Germany’s best hope of victory.

The Second Battle of the Marne turned the tide of war decisively towards the Allies, who were able to regain much of France and Belgium in the months that followed.

The Harlem Hellfighters and Other All-Black Regiments

By the time World War I began, there were four all-Black regiments in the U.S. military: the 24th and 25th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry. All four regiments comprised of celebrated soldiers who fought in the Spanish-American War and American-Indian Wars , and served in the American territories. But they were not deployed for overseas combat in World War I.

Blacks serving alongside white soldiers on the front lines in Europe was inconceivable to the U.S. military. Instead, the first African American troops sent overseas served in segregated labor battalions, restricted to menial roles in the Army and Navy, and shutout of the Marines, entirely. Their duties mostly included unloading ships, transporting materials from train depots, bases and ports, digging trenches, cooking and maintenance, removing barbed wire and inoperable equipment, and burying soldiers.

Facing criticism from the Black community and civil rights organizations for its quotas and treatment of African American soldiers in the war effort, the military formed two Black combat units in 1917, the 92nd and 93rd Divisions . Trained separately and inadequately in the United States, the divisions fared differently in the war. The 92nd faced criticism for their performance in the Meuse-Argonne campaign in September 1918. The 93rd Division, however, had more success.

With dwindling armies, France asked America for reinforcements, and General John Pershing , commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, sent regiments in the 93 Division to over, since France had experience fighting alongside Black soldiers from their Senegalese French Colonial army. The 93 Division’s 369 regiment, nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters , fought so gallantly, with a total of 191 days on the front lines, longer than any AEF regiment, that France awarded them the Croix de Guerre for their heroism. More than 350,000 African American soldiers would serve in World War I in various capacities.

Toward Armistice

By the fall of 1918, the Central Powers were unraveling on all fronts.

Despite the Turkish victory at Gallipoli, later defeats by invading forces and an Arab revolt that destroyed the Ottoman economy and devastated its land, and the Turks signed a treaty with the Allies in late October 1918.

Austria-Hungary, dissolving from within due to growing nationalist movements among its diverse population, reached an armistice on November 4. Facing dwindling resources on the battlefield, discontent on the homefront and the surrender of its allies, Germany was finally forced to seek an armistice on November 11, 1918, ending World War I.

Treaty of Versailles

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Allied leaders stated their desire to build a post-war world that would safeguard itself against future conflicts of such a devastating scale.

Some hopeful participants had even begun calling World War I “the War to End All Wars.” But the Treaty of Versailles , signed on June 28, 1919, would not achieve that lofty goal.

Saddled with war guilt, heavy reparations and denied entrance into the League of Nations , Germany felt tricked into signing the treaty, having believed any peace would be a “peace without victory,” as put forward by President Wilson in his famous Fourteen Points speech of January 1918.

As the years passed, hatred of the Versailles treaty and its authors settled into a smoldering resentment in Germany that would, two decades later, be counted among the causes of World War II .

World War I Casualties

World War I took the lives of more than 9 million soldiers; 21 million more were wounded. Civilian casualties numbered close to 10 million. The two nations most affected were Germany and France, each of which sent some 80 percent of their male populations between the ages of 15 and 49 into battle.

The political disruption surrounding World War I also contributed to the fall of four venerable imperial dynasties: Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia and Turkey.

Legacy of World War I

World War I brought about massive social upheaval, as millions of women entered the workforce to replace men who went to war and those who never came back. The first global war also helped to spread one of the world’s deadliest global pandemics, the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918, which killed an estimated 20 to 50 million people.

World War I has also been referred to as “the first modern war.” Many of the technologies now associated with military conflict—machine guns, tanks , aerial combat and radio communications—were introduced on a massive scale during World War I.

The severe effects that chemical weapons such as mustard gas and phosgene had on soldiers and civilians during World War I galvanized public and military attitudes against their continued use. The Geneva Convention agreements, signed in 1925, restricted the use of chemical and biological agents in warfare and remain in effect today.

Photo Galleries

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- LibGuides

- A-Z List

- Help

World War I: The Great War

- Culture and Society

European History Journals

- 1914-1918 Online Over the course of three years, the international joint research project "1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War” is developing an English-language virtual reference work on the First World War. Planned to be released in 2014, the centenary of the outbreak of World War I, the online encyclopedia will be the result of an international collaborative project to make available a multi-perspective, public-access knowledge base on the First World War.

- The Great War Primary Documents Archive This archive of primary documents from the Great War period is international in focus. The intention is to present in one location both primary and relevant secondary documents between 1890-1930.

- Imperial War Museums (WWI) IWM is a family of five museums: IWM London; IWM North in Trafford, Greater Manchester; IWM Duxford near Cambridge; the Churchill War Rooms in Whitehall, London; and the historic ship HMS Belfast, moored in the Pool of London on the River Thames. The information on this website tells you about the permanent displays, the archives, special exhibitions, forthcoming events, education programmes, corporate hospitality and shopping facilities.

- Progressive Era and WWI Compilation of essays by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

- World War I Centenary: Continuations and Beginnings World War I Centenary: Continuations and Beginnings is building a substantial collection of learning resources available for global reuse. A rich variety of materials, including expert articles, audio and video lectures, downloadable images, interactive maps and ebooks are available under a set of cross-disciplinary themes that seek to reappraise the War in its cultural, social, geographical and historical contexts. Many of these resources have been specially created by the University of Oxford and partner academics for this website.

- World War I Records Records from the US National Archives collections.

- WSJ World War I Centenary The Wall Street Journal has selected 100 legacies from World War I that continue to shape our lives today.

In this page, you will find resources that analyze the end of WWI and the immediate impact of the conflict and peace treaties.

Footage of the Aftermath

- Remembrance A few key films of Armistice Day / Remembrance Day / Remembrance Sunday and the use of poppies.

Source: British Pathe, WWI - The Definitive Collection

Political Climate

- Treaties and Reparations Source: The US Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

- Treaty of Saint-Germain

- Treaty of Versailles

Best Books to Start

Article Databases

- America: History & Life Indexes 2,000+ scholarly journals in history covering the United States and Canada.

- Historical Abstracts Indexes 2,000+ scholarly journals in history from 1450 to the present. Excludes the United States and Canada.

- History Compass Peer-reviewed surveys of the most important research and current thinking in history.

- << Previous: Culture and Society

- Next: Citation >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2023 2:10 PM

- URL: https://library.fiu.edu/wwi

Information

Fiu libraries floorplans, green library, modesto a. maidique campus, hubert library, biscayne bay campus.

Directions: Green Library, MMC

Directions: Hubert Library, BBC

Aftermath of World War I and the Rise of Nazism, 1918–1933

In the aftermath of World War I, Germans struggled to understand their country’s uncertain future. Citizens faced poor economic conditions, skyrocketing unemployment, political instability, and profound social change. While downplaying more extreme goals, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party offered simple solutions to Germany’s problems, exploiting people’s fears, frustrations, and hopes to win broad support.

NARRATOR: Paris, 1900. More than fifty million people from around the world visited the Universal Exposition—a world’s fair intended to promote greater understanding and tolerance among nations, and to celebrate the new century, new inventions, exciting progress. The 20th century began much like our own—with hope that education, science and technology could create a better, more peaceful world. What followed soon after were two devastating wars.

TEXT ON SCREEN: The Path to Nazi Genocide

NARRATOR: The first “world war,” from 1914 to 1918, was fought throughout Europe and beyond. It became known as “the war to end all wars.” It cast an immense shadow on tens of millions of people. “This is not war,” one wounded soldier wrote home.

“It is the ending of the world.” Half of all Frenchmen aged 20 to 32 at war’s outbreak were dead when it was over. More than one third of all German men aged 19 to 22 were killed. Millions of veterans were crippled in body and in spirit. Advances in the technology of killing included the use of poison gas. Under the pressure of unending carnage, governments toppled and great empires dissolved. It was a cataclysm that darkened the world’s view of humanity and its future. Winston Churchill said the war left “a crippled, broken world.”

TEXT ON SCREEN: Aftermath of World War I and the Rise of Nazism, 1918-1933

NARRATOR: The humiliation of Germany’s defeat and the peace settlement that followed in 1919 would play an important role in the rise of Nazism and the coming of a second “world war” just 20 years later.

What shocked so many in Germany about the treaty signed near Paris, at the Palace of Versailles, was that the victors dictated a future in which Germany was deprived of any significant military power. Germany’s territory was reduced by 13%. Germany was forced to accept full responsibility for starting the war and to pay heavy reparations.

To many, including 30-year old former army corporal Adolf Hitler, it seemed the country had been “stabbed in the back”—betrayed by subversives at home and by the government who accepted the armistice. In fact, the German military had quietly sought an end to the war it could no longer win in 1918. “It cannot be that two million Germans should have fallen in vain,” Adolf Hitler later wrote. “We demand vengeance!”

Many veterans and other citizens struggled to understand Germany’s defeat and the uncertain future. Troops left the bloody battlefields and returned to a bewildering society. A new and unfamiliar democratic form of government—the Weimar Republic—replaced the authoritarian empire and immediately faced daunting challenges.

Thousands of Germans waited in lines for work and food in the early 1920s. Middle class savings were wiped out as severe inflation left the currency worthless. Some burned it for fuel. Economic conditions stabilized for a few years, then the worldwide depression hit in 1929. The German banking system collapsed, and by 1930 unemployment skyrocketed to 22%.

In a country plagued by joblessness, embittered by loss of territory, and demoralized by ineffective government, political demonstrations frequently turned violent. Many political parties had their own paramilitary units to attack opponents and intimidate voters. In 1932, ninety-nine people were killed in the streets in one month.

Right–wing propaganda and demonstrations played on fears of a Communist revolution spreading from the Soviet Union.

New social problems emerged from the impact of rapid industrialization and the growth of cities. Standards of behavior were changing. Crime was on the rise. Sexual norms were in flux. For the first time, women were working outside the home in large numbers, and the new constitution gave women the right to vote. Germany’s fledgling democracy was profoundly tested by the crumbling of old values and fears of what might come next.

Adolf Hitler had been undisputed leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party—known as Nazis—since 1921. In 1923, he was imprisoned for trying to overthrow the government. His trial brought him fame and followers. He used the jail time to dictate his political ideas in a book, Mein Kampf—My Struggle.

Hitler’s ideological goals included territorial expansion, consolidation of a racially pure state, and elimination of the European Jews and other perceived enemies of Germany. He served only a short jail sentence, and after the ban was lifted on his National Socialist Party, Hitler and his followers rejoined the battle in the streets and in the countryside.

The Nazi Party recruited, organized, and produced a newspaper to spread its message. While downplaying more extreme Nazi goals, they offered simple solutions to Germany’s problems, exploiting people’s fears, frustrations, and hopes. In the early 1930s, the frequency of elections was dizzying. So was the number of parties and splinter groups vying for votes. Hitler proved to be a charismatic campaigner and used the latest technology to reach people. The Nazi Party gained broad support, including many in the middle class—intellectuals, civil servants, students, professionals, shopkeepers and clerks ruined by the Depression. But the Nazis never received more than 38% of the vote in a free national election. No party was able to win a clear majority, and without political consensus, successive governments could not effectively govern the nation.

Adolf Hitler was not elected to office and he did not have to seize power. He was offered a deal just as the Nazis started to lose votes. In January 1933, when the old war hero, President Paul von Hindenburg, invited Hitler to serve as Chancellor in a coalition government, the Nazis could hardly believe their luck. The Nazis were revolutionaries who wanted to radically transform Germany. The conservative politicians in the new Cabinet didn’t like or trust Hitler, but they liked democracy even less, and they saw the leftist parties as a bigger threat. They reached out to the Nazis to help build a majority in Parliament. They were confident they could control Hitler.

One month later, when arson gutted the German parliament building, Hitler and his nationalist coalition partners seized their chance. Exploiting widespread fears of a communist uprising, they blamed Communists for the fire, and declared emergency rule. President Hindenburg signed a decree that suspended all basic civil rights and constitutional protections, providing the basis for arbitrary police actions.The new government’s first targets were political opponents. Under the emergency decree, they could be terrorized, beaten and held indefinitely. Leaders of trade unions and opposition parties were arrested. German authorities sent thousands, including leftist members of Parliament, to newly established concentration camps.

Despite Nazi terror and brutal suppression of their opponents, many German citizens willingly accepted or actively supported these extreme measures in favor of order and security. Many Germans felt a new hope and confidence in the future of their country with the prospect of a bold, young charismatic leader. Nazi propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels planned to win over those who were still unconvinced.

GOEBBELS [speaking German]: One must govern well, and for good government one must also practice good propaganda. They work together. A good government without propaganda is not more possible than good propaganda without a good government.

NARRATOR: Hitler spoke to the SA, his army of storm troopers.

HITLER [speaking German]: Germany has awakened! We have won power in Germany. Now we must win the German people.

Discussion Question

How did conditions in Germany and Europe at the end of World War I contribute to the rise and triumph of Nazism in Germany?

- The Impact of World War One on the Israel-Palestine Conflict

Arguably, the most intractable conflict of the past 100 years has been between Israel and Palestine . Therefore, it is necessary to understand this conflict in its totality for there to be any chance of a resolution. Many events in the 20th and 21st centuries have fundamentally shaped Israel-Palestine. However, perhaps none were more important than the First World War .

World War One began on June 28th, 1914 , when Gavrilo Principe, a Serbian nationalist, assassinated Archduke of Austria-Hungary Franz Ferdinand. This event set off a chain reaction in which the major alliances of Europe all went to war, with France , the United Kingdom (UK), and Russia on one side and Germany , Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire on the other side. After over four years of fighting, which was characterized by trench warfare in which young men and boys were massacred trying to advance mere hundreds of meters, the war ended on November 11th, 1918, when Germany and the Allies signed an armistice. The deadliest conflict in world history up to that point, about 20 million people died, and an additional 21 million were injured.

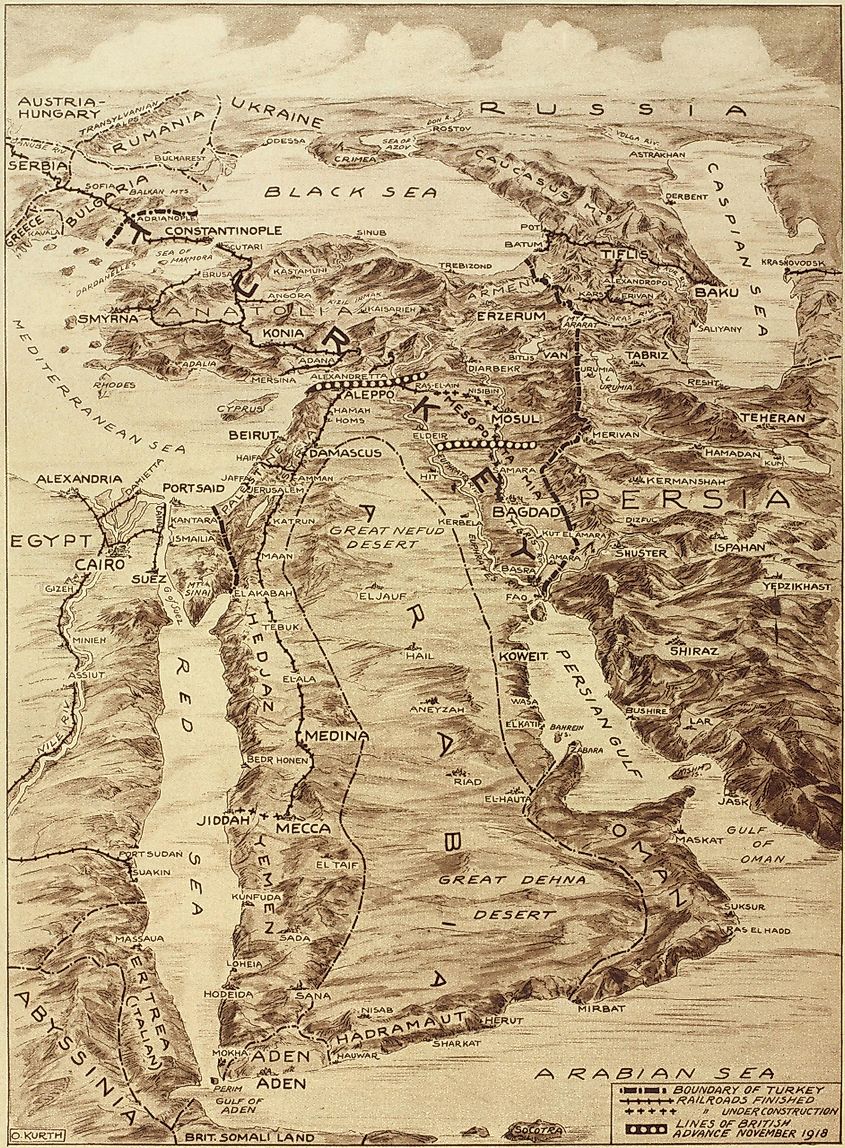

The Middle East in World War One

The Middle-Eastern front in World War One consisted of four distinct fronts, with the Ottomans fighting the Allies in southern Mesopotamia, southern Palestine, the Caucasus , and Gallipoli . Ottoman troops fought well in these regions, even beating back the Allies in Gallipoli and southern Mesopotamia in early 1915 and April 1916, respectively. Nonetheless, the British managed to traverse the Sinai Peninsula before taking southern Palestine, followed by Jerusalem in December 1917. Thereafter, they quickly moved up the coast, with the Ottoman Empire eventually being defeated by October 1918. To achieve this victory, the British government made several promises to different groups, all of which involved Palestine. These promises were contradictory and mutually exclusive, paving the way for seemingly inevitable conflict.

British Promises

The mcmahon-hussein correspondence.

The first set of promises was made by the British government to Sharif Hussein, the leader of the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during World War I. These promises were formally articulated in a letter from British diplomat Henry McMahon to Hussein on October 24th, 1915.

In it, McMahon promised that the British would help Hussein establish an independent Arab kingdom if he revolted against the Ottomans. But, crucially, the letter said that "the districts of Mersina and Alexandretta, and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus , Homs, Hama, and Aleppo , cannot be said to be purely Arab, and must on that account be excepted from the proposed limits and boundaries." Due to this sentence, the British believed that they had not promised Palestine to the Arabs , with Palestine supposedly being west of these "districts." McMahon further confirmed this interpretation, as he did not explicitly mention Palestine as part of Hussein's future kingdom.

However, in the Ottoman Empire, district meant vilayet (the rough equivalent of a state or a province), and while there were vilayets in Damascus and Aleppo, there were no such equivalents for Homs and Hama. Furthermore, even if there were vilayets with these names, the portions of Syria left of these regions were part of Lebanon , not Palestine. In other words, the British, through either sloppy or deceitful language, had, by omission, effectively promised Palestine as part of this new Arab Kingdom.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement

These "accidental" promises to the Arabs conflicted with other guarantees. For instance, the Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916) was a treaty between the UK and France concerning control of former Ottoman territories after the war. According to the agreement, the French were to receive Lebanon and Syria, whereas the British were to control southern Iraq and Jordan . It was also agreed that Palestine would come under international control but with some French influence. This, therefore, conflicted with the implicit promises of the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence. Moreover, it directly contradicted the forthcoming Balfour Declaration.

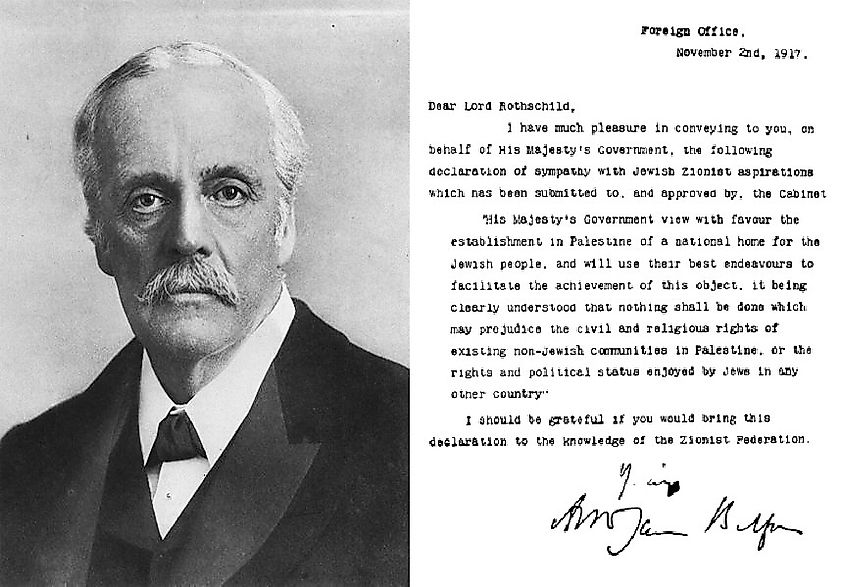

The Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was issued by the British government in November 1917. It conveyed the UK's intention to help "(establish) in Palestine...a national home for the Jewish people". The British did this for several reasons. First, they hoped it would rally Jewish support for the Allies. There were also some romantic ideas, rooted in Christianity, about Jews returning to the Holy Land. Antisemitism was also a motivating factor, with some British politicians believing that promising a national home to Jews would help remove their presence from the UK.

Finally, the Balfour Declaration offered a reason for the British to renege on the promise to give the French influence in the region. However, the specific wording of the Balfour Declaration was crucial. The British never promised a Jewish state in Palestine, only a "national home." What this meant was incredibly vague. Moreover, what it meant to "facilitate the establishment" of this national home was also conspicuously unclear. When combined with all the other guarantees the British had made, this vague language was a recipe for confusion and anger.

As World War I ended, American President Woodrow Wilson's 14 points, which preached the value of self-determination, were rising in popularity. However, these notions were built on assumptions about which nations were "ready" for independence- most of which were European. For non-European nations, the mandate system was created, in which European powers helped "guide" these soon-to-be states towards independence.

Thus, as the Ottoman Empire collapsed, the non-Anatolian regions of the former empire came under the control of France and the UK. France received Syria and Lebanon, whereas the British received Iraq, Jordan, and Palestine. This meant that the British were now legally required to fulfill the promises of the Balfour Declaration. The subsequent mandate period was full of tumult and unrest, and when combined with lingering anger from the other promises of World War One, which were now broken, set the stage for decades of conflict in the region.

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, World War I fundamentally shaped Israel-Palestine. Indeed, as the British desperately tried to win the war, they promised Palestine to several different groups. When the war ended, they were tasked with governing Palestine while also dealing with the ramifications of these promises, many of which were now broken. This provided a fertile ground for a seemingly intractable conflict to emerge.

More in History

What Romans Saw When They Reached New Parts Of The World

Longest Wars In Human History

Early Zionism, the Ottoman Empire, and Israel-Palestine

Battle of Kursk

What Weapon Killed the Most People in World War 2?

What is Genocide?

The Greatest Heist in History: The Hijacking of Alexander the Great's Body

Russian Civil War

The Construction and History of Alcatraz

This essay is about the construction and history of Alcatraz Island. Initially designated as a military reservation in 1850, Alcatraz’s first significant structure was a lighthouse completed in 1854. Over the years, it transformed into a military fortress equipped with cannons during the Civil War. By the late 19th century, it became a military prison, and in 1933, it was converted into a federal penitentiary. Alcatraz housed notorious criminals like Al Capone and George “Machine Gun” Kelly until its closure in 1963. Today, Alcatraz is a popular tourist destination managed by the National Park Service, preserving its historical significance.

How it works

Alcatraz Island, situated amidst the waters of San Francisco Bay, is synonymous with the notorious federal penitentiary that once harbored some of America’s most infamous transgressors. Nevertheless, the chronicle of Alcatraz extends far beyond its epoch as a correctional facility. Deciphering the genesis of Alcatraz entails an exploration of its inception as a bastion of military fortifications and its progression across the annals of time.

The saga of Alcatraz commenced in the mid-19th century, antecedent to its notoriety as a federal penitentiary.

In 1850, President Millard Fillmore designated the island as a military enclave. Its strategic position rendered it an optimal locale for the construction of a military stronghold aimed at safeguarding San Francisco Bay against potential incursions amidst the tumultuous aftermath of the Mexican-American War. The erection of military fortifications on Alcatraz commenced in the early 1850s, with the foremost edifice being a beacon, finalized in 1854. This beacon, the inaugural of its kind on the Western Seaboard, symbolized the island’s initial function in facilitating maritime navigation and furnishing a martial presence.

The metamorphosis of Alcatraz into a more impregnable military bastion transpired in subsequent decades. In the latter part of the 1850s, the U.S. Army initiated the construction of a fortress outfitted with an arsenal exceeding 100 cannons. By 1861, amidst the eruption of the Civil War, Alcatraz was fully equipped to safeguard the bay. The fortifications encompassed a citadel atop the island’s zenith, serving as a terminal bulwark and barracks for soldiers. Although Alcatraz never confronted a direct martial threat, its deterrent presence was not inconsequential.

By the conclusion of the 19th century, the role of Alcatraz began to shift from a military bastion to a military detention facility. In 1868, it was formally designated as a long-term detention center for military convicts. The isolation of the island rendered it an optimal venue for incarcerating inmates deemed flight risks or exhibiting recalcitrant behavior. Over time, the infrastructure on Alcatraz was expanded and reconfigured to accommodate its novel role. The citadel was repurposed to accommodate inmates, and supplementary cell blocks were erected.

The most transformative epoch in Alcatraz’s annals materialized in the early 20th century. In 1933, the island was transferred from the War Department to the Department of Justice, heralding its transition from a military prison to a federal penitentiary. This transition constituted a facet of a broader endeavor to counter the escalating crime rates during the Prohibition epoch and the throes of the Great Depression. The federal administration sought a supermax prison capable of detaining the most incorrigible felons, and Alcatraz’s isolation rendered it the quintessential candidate.

The erection of the novel federal penitentiary entailed substantial refurbishments and enhancements to extant structures. By 1934, Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary was inaugurated, architected to be impervious to escape attempts and equipped to detain high-profile inmates. Over the ensuing three decades, it accommodated some of America’s most notorious felons, encompassing Al Capone, George “Machine Gun” Kelly, and Robert Stroud, the “Birdman of Alcatraz.” The rigorous conditions and regimented regime at Alcatraz were intended to deter criminality and forestall escapes, and notwithstanding sporadic attempts, none eventuated in definitive success.

Despite its formidable repute, the operational overheads of sustaining Alcatraz were prohibitive, and by the 1960s, it became manifest that the penitentiary was no longer economically viable. In 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy decreed the closure of Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary. The remaining inmates were transferred to alternate facilities, and the island languished in desolation for several years.