Learning Goals

- ISTE6: Students communicate clearly and express themselves creatively for a variety of purposes using the platforms, tools, styles, formats and digital media appropriate to their goals.

Persuasive Techniques & Rhetoric (Logos, Ethos, Pathos)

Persuasive techniques & rhetoric (logos, ethos, pathos)title and description.

Persuasive Techniques & Rhetoric (Logos, Ethos, Pathos) was developed by Jen Kastanek as part of the Nebraska ESUCC Special Project for BlendEd Best Practices.

Content Area Skill:

English 9-10

Digital Age Skill(s):

Creative Communicator

Duration of Unit:

15 +/- days

Overview of Unit:

In this unit, students will …

1. Define, identify, analyze, and effectively use four persuasive techniques.

2. Define, identify, analyze, and effectively use persuasive rhetoric.

3. Effectively use the writing process to create a persuasive essay and persuade the reader of their position on an established topic.

4. Extend their knowledge of persuasive techniques and rhetoric to create a real-world multimedia product using or teaching persuasion.

Empower Learners:

Empower learner activity:, detailed description:.

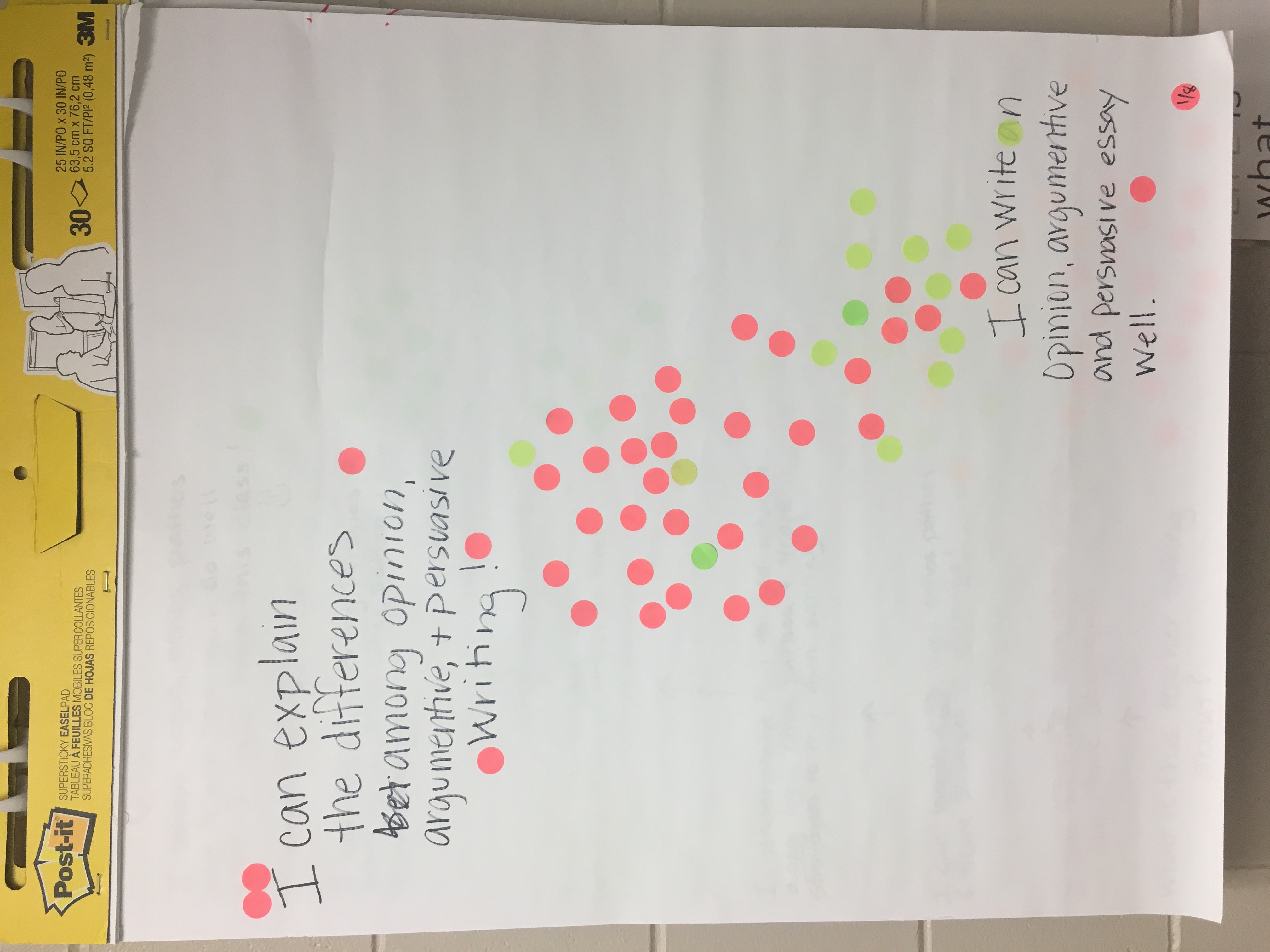

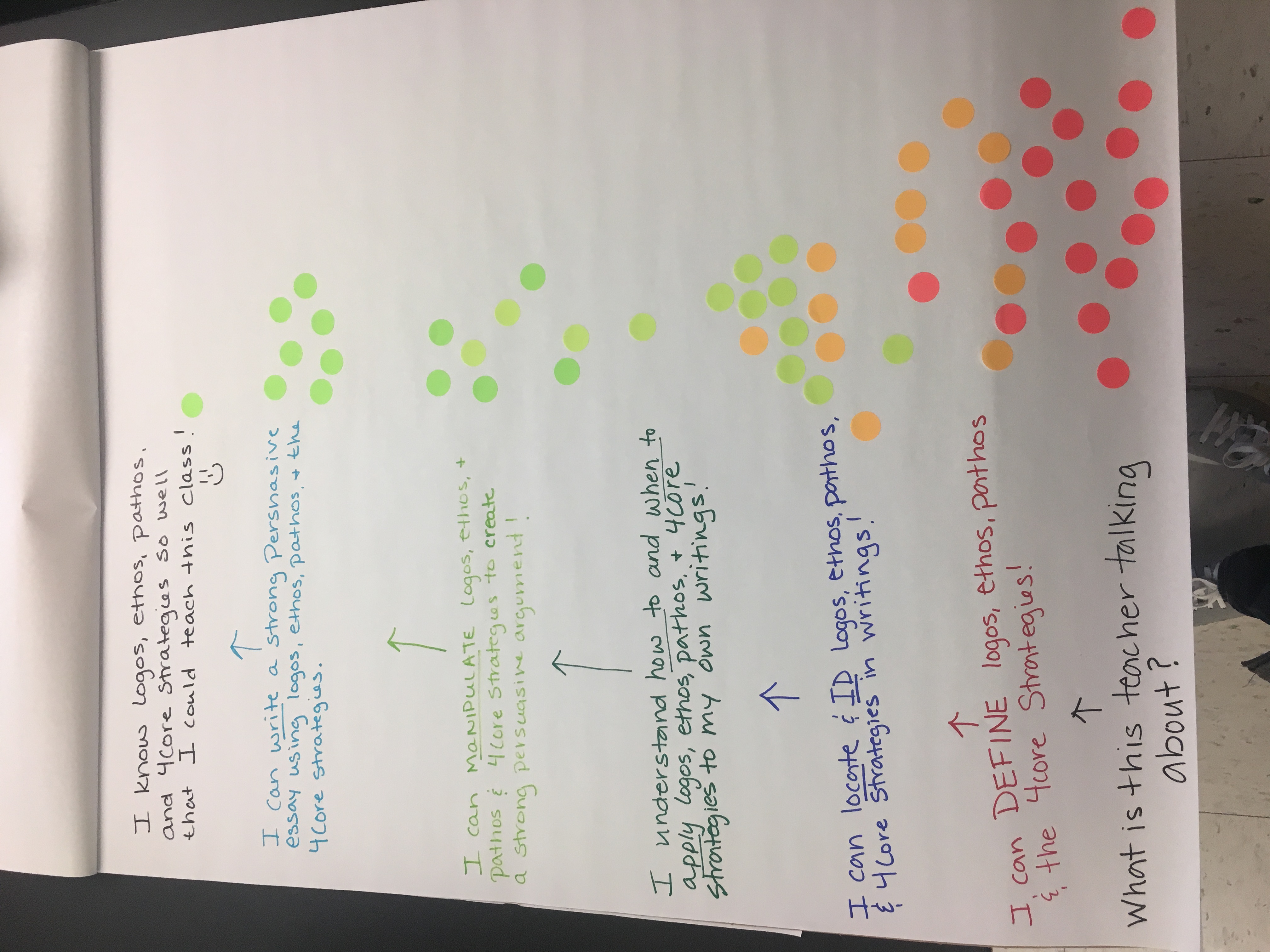

Stickers on the Wall: Objective options are listed on a large sticky pad on the wall. Students place their sticker at the appropriate level they feel describes them. This is repeated after every learning step. ( Image1 Image2 of the finished chart here).

Proficiency - Student Scale

Proficiency Detailed - Student Rate

Knowledge Application:

Artifact Profile:

Student made video or YouTube advertisement

Student(s) will create a video/flipped lesson/PowToon demonstrating understanding of persuasive techniques and persuasive rhetoric.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1G35uwZQ-5QEialcN6iw47BmpTba90xt_O30-Rxu13iI/edit?usp=sharing

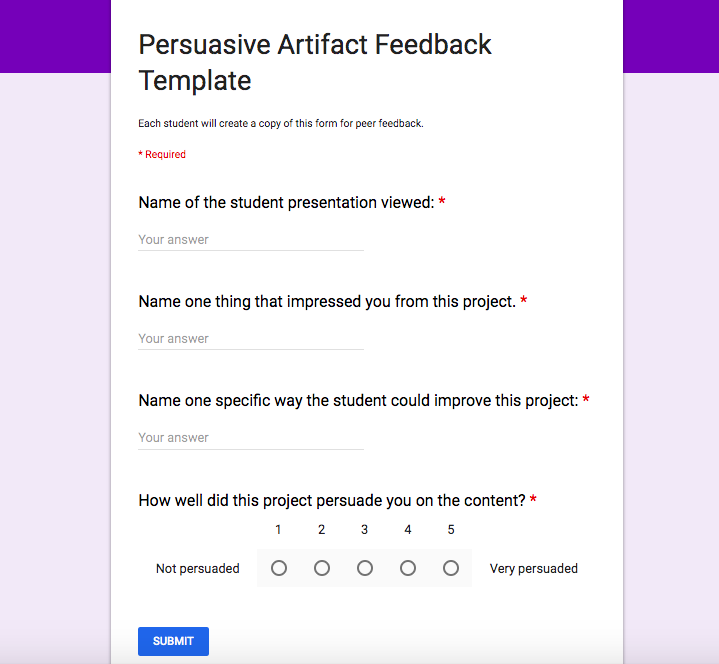

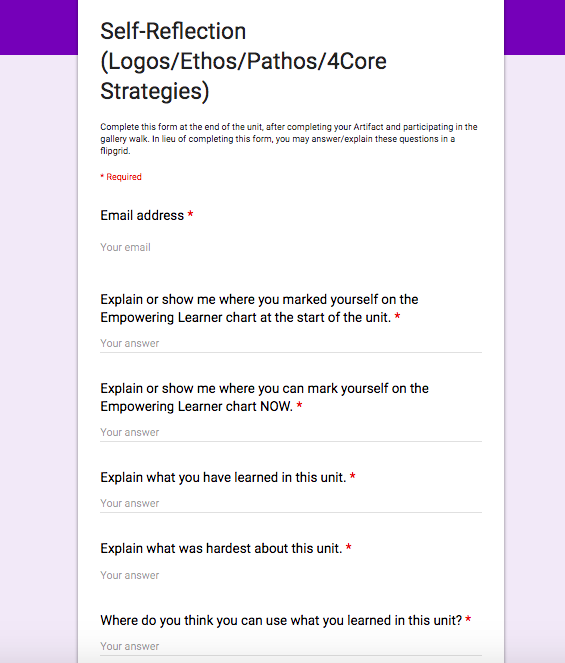

Students create an 8x10 poster/graphic with a QR code linked to their final artifact. Posters will be displayed and students will have the opportunity for a gallery walk to present their work. Observers can fill out a feedback form for three projects and a self-reflection form or Flipgrid.

Persuasive Artifact Feedback Template

Self-Reflection (Logos/Ethos/Pathos/4 Core Strategies)

Content Area Skills Addressed:

10.1.5, 10.1.6, 10.2.2, 10.3.3

Digital Age Skills

Link to rubric.

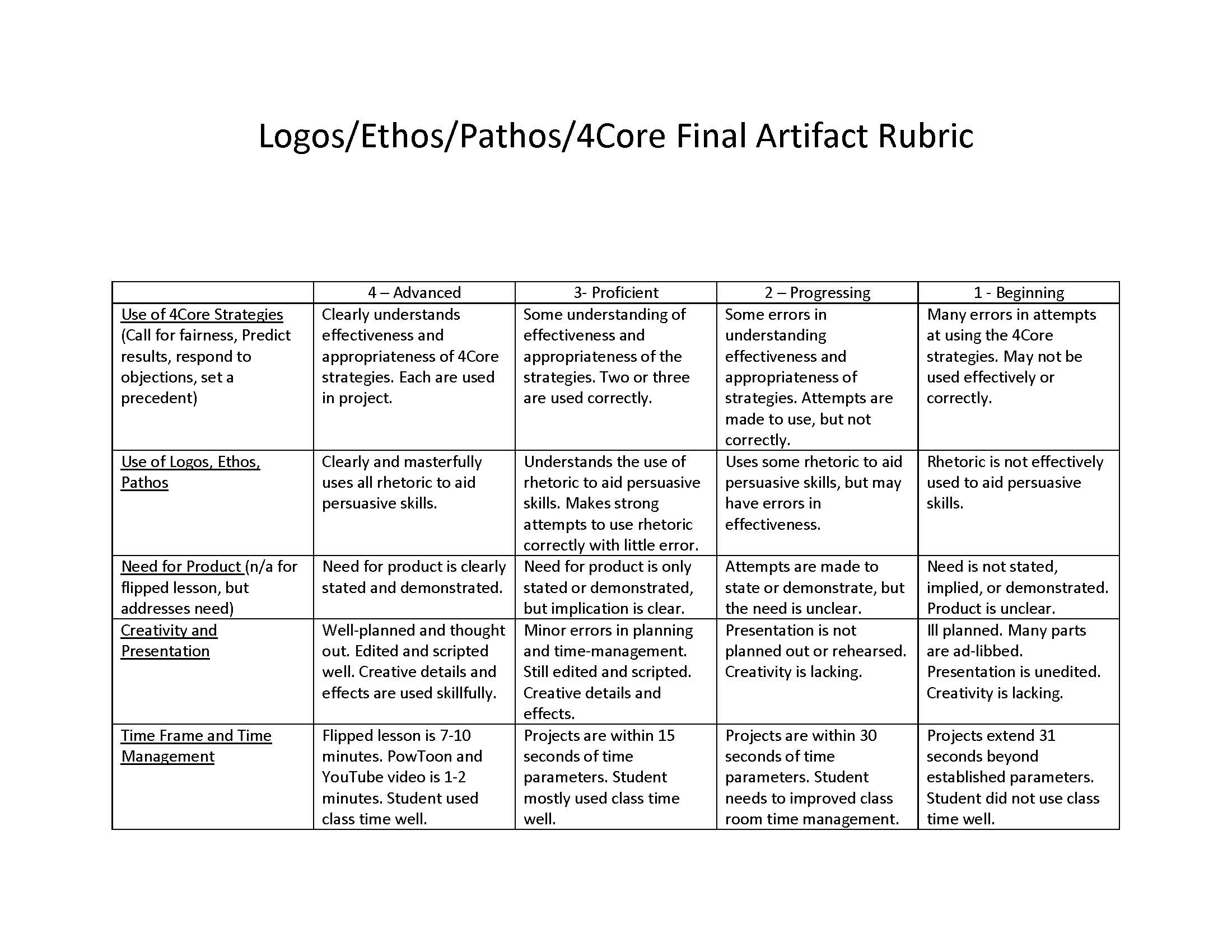

Artifact Rubric

Knowledge Deepening:

Task 1: identifying logos/ethos/pathos in tv commercials\print media (station rotation & whole group instruction).

Students view various television commercials and ID what rhetoric is being utilized in the commercial. Can be done as combination whole class or station rotation with each rotation viewing a link to a particular video (see Learning Path day 3-4 for details). Students can discuss various questions concerning the effectiveness of the commercials in small groups. Last station would be whole group to check understanding and provide self-reflection. (I do, we do, you do method) Tasks

Task 2: ID Logos, Ethos, Pathos in Speeches

Students use the playlist to practice annotating, identifying and analyzing the effectiveness of Logos, Ethos, and Pathos in speeches.

Task 3: ID 4Core Strategies in editorials

Introduce 4Core persuasive strategies.

Direct Instruction:

Learning path:, nebraska's college and career ready standards for english language arts.

Learning Domain: Reading

Standard: Analyze the function and critique the effects of the author‘s use of literary devices (e.g., simile, metaphor, personification, idiom, oxymoron, hyperbole, alliteration, onomatopoeia, analogy, dialect, tone, mood).

Degree of Alignment: Not Rated (0 users)

Standard: Interpret and evaluate information from print and digital text features to support comprehension.

Standard: Construct and/or answer literal, inferential, critical, and interpretive questions, analyzing and synthesizing evidence from the text and additional sources to support answers.

Standard: Select text for a particular purpose (e.g., answer a question, solve problems, enjoy, form an opinion, understand a specific viewpoint, predict outcomes, discover models for own writing, accomplish a task), citing evidence to support analysis, reflection, or research.

Learning Domain: Writing

Standard: Use multiple writing strategies recursively to investigate and generate ideas, organize information, guide writing, answer questions, and synthesize information.

Standard: Communicate information and ideas effectively in analytic, argumentative, descriptive, informative, narrative, poetic, persuasive, and reflective modes to multiple audiences using a variety of media and formats.

Cite this work

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.4: Persuasive Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 107782

- Kathryn Crowther et al.

- Georgia Perimeter College via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

Writing a Persuasive Essay

Choose a topic that you feel passionate about. If your instructor requires you to write about a specific topic, approach the subject from an angle that interests you. Begin your essay with an engaging introduction. Your thesis should typically appear somewhere in your introduction. Be sure to have a clear thesis that states your position and previews the main points your essay will address.

Start by acknowledging and explaining points of view that may conflict with your own to build credibility and trust with your audience. Also state the limits of your argument. This too helps you sound more reasonable and honest to those who may naturally be inclined to disagree with your view. By respectfully acknowledging opposing arguments and conceding limitations to your own view, you set a measured and responsible tone for the essay.

Make your appeals in support of your thesis by using sound, credible evidence. Use a balance of facts and opinions from a wide range of sources, such as scientific studies, expert testimony, statistics, and personal anecdotes. Each piece of evidence should be fully explained and clearly stated. Make sure that your style and tone are appropriate for your subject and audience. Tailor your language and word choice to these two factors, while still being true to your own voice.

Finally, write a conclusion that effectively summarizes the main argument and reinforces your thesis. See the sample persuasive essay at the end of this section, “The Value of Technical High Schools in Georgia’s Business Marketplace,” by student Elizabeth Lamoureux. Please note that this essay uses the MLA style of documentation, for which you can find guidelines at Purdue University’s Online Writing Lab (OWL) website: http://owl.english.purdue.edu .

Sample Persuasive Essay

In this student paper, the student makes a persuasive case for the value of technical high schools in Georgia. As you read, pay attention to the different persuasive devices the writer uses to convince us of her position. Also note how the outline gives a structure to the paper that helps lead the reader step-by-step through the components of the argument.

Student Outline

Elizabeth Lamoureux

English 1101 Honors

April 25, 2013

Thesis : Technical high schools should be established in every county in Georgia because they can provide the technical training that companies need, can get young people into the workforce earlier, and can reduce the number of drop outs.

- Education can focus on these specific technical fields.

- Education can work with business to fill these positions.

- Apprenticeship programs can be a vital part of a student’s education.

- Apprenticeship programs are integral to Germany’s educational program, providing a realistic model for technical high schools in Georgia.

- Students train during their high school years for their chosen profession.

- Students begin to work in a profession or trade where there is a need.

- Students will become independent and self-supporting at the age of eighteen when many of their peers are still dependent upon their parents.

- Students can make more money over the course of their lifetimes.

- Students are more motivated to take courses in which they have an interest.

- Students will find both core and specialized classes more interesting and valuable when they can see the practical application of the subjects.

- Students would be able to earn a living wage while still taking classes that would eventually lead to full-time employment.

- Students would learn financial skills through experience with money management.

Student Essay

The Value of Technical High Schools in Georgia’s Business Marketplace

Businesses need specialized workers; young people need jobs. It seems like this would be an easy problem to solve. However, business and education are not communicating with each other. To add to this dilemma, emphasis is still put on a college education for everyone. Samuel Halperin, study director of the Commission on Work, Family, and Citizenship for the W. T. Grant Foundation, co-authored two reports: “The Forgotten Half: Non-College Youth in America” and “The Forgotten Half: Pathways to Success for America’s Youth and Young Families.” Halperin states: “While the attention of the nation was focused on kids going to college . . . the truth is that 70 percent of our adults never earn a college degree” (qtd. in Rogers). According to an article in Issues in Science and Technology, the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that there will be more need for skills obtained through “community colleges, occupational training, and work experience” (Lerman). As Anne C. Lewis points out, although the poor job situation is recognized as detrimental to American youth, President Bush tried to get rid of career and technical education (CTE) and “promote strictly academic programs.” Luckily, Congress did not support it (Lewis 5). The figure for U.S. teen joblessness in October 2009 was 27.6 percent, the highest since World War II (Karaim). According to Thomas E. Persing, Americans are “disregarding the 50 percent who enter college and fail to graduate. . . .” Since everyone does not want or need to go to college, young people need an alternative choice, namely, technical high schools. Technical high schools should be established in every county in Georgia because they can provide the technical training that companies need, can get young people into the work force earlier, and can reduce the number of drop outs.

Technical high schools provide students with the technical training that companies need. By getting input from businesses on exactly what their specialized needs are, school systems could adapt their curricula to accommodate the needs of businesses. According to an article in Issues in Science and Technology, “employers report difficulty in recruiting workers with adequate skills.” The article goes on to say that “the shortage of available skills is affecting their ability to serve customers, and 84% of the firms say that the K-12 school system is not doing a good job preparing students for the workplace” (Lerman). Education can work with businesses to provide them with the workforce they need, and students can learn the skills they need through apprenticeship programs.

Business can be further involved by providing these apprenticeship programs, which can be a vital part of a student’s education. Currently, Robert Reich, economist and former Secretary of Labor, and Richard Riley, Secretary of Education, have spoken up for apprenticeship programs (Persing). In these programs, not only do students learn job-specific skills, but they also learn other skills for success in the work place, such as “communication, responsibility, teamwork, allocating resources, problem-solving, and finding information” (Lerman). Businesses complain that the current educational system is failing in this regard and that students enter the workforce without these skills.

The United States could learn from other countries. Apprenticeship programs are integral to Germany’s educational program, for example. Because such large numbers of students in a wide array of fields take advantage of these programs, the stigma of not attending college is reduced. Timothy Taylor, the Conversable Economist, explains that most German students complete this program and still have the option to pursue a postsecondary degree. Many occupations are represented in this program, including engineering, nursing, and teaching. Apprenticeship programs can last from one to six years and provide students with a wage for learning. This allows both business and student to compete in the market place. According to Julie Rawe, “under Germany’s earn-while-you-learn system, companies are paying 1.6 million young adults to train for about 350 types of jobs. . . .”

A second important reason technical high schools should be promoted in Georgia is that they prepare students to enter the work force earlier. Students not interested in college enter the work force upon high school graduation or sooner if they have participated in an apprenticeship or other cooperative program with a business. Students train during their high school years for their chosen profession and often work for the company where they trained. This ensures that students begin to work in a profession or trade where there is a need.

Another positive factor is that jobs allow students to earn a living upon graduation or before. Even though students are considered adults at eighteen, many cannot support themselves. The jobs available to young people are primarily minimum wage jobs which do not provide them with enough resources to live independently. One recent study indicates that the income gap is widening for young people, and “In March 1997, more than one-fourth of out-ofschool young adults who were working full-time were earning less than the poverty line income standard of just over $16,000 annually for a family of four” (“The Forgotten Half Revisited”). Conversely, by entering the work force earlier with the skills businesses need, young people make more money over their lifetimes. Robert I. Lerman considers the advantages:

Studies generally find that education programs with close links to the world of work improve earnings. The earnings gains are especially solid for students unlikely to attend or complete college. Cooperative education, school enterprises, and internship or apprenticeship increased employment and lowered the share of young men who are idle after high school.

Young people can obviously profit from entering the work force earlier.

One of the major benefits of promoting technical high schools in Georgia is that they reduce the number of dropouts. According to an article in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the figure for dropouts for the Atlanta metro area is about thirty-four percent (McCaffrey and Badertscher A16). The statistic for Germany’s dropout rate is less than nine percent (Rawe). As Rawe maintains, students stay in school because they cannot get the job if they do not have the diploma. Beyond the strong incentive of a job, students are more motivated to take courses in which they have an interest. In addition to the specialized career classes, students are still required to take core classes required by traditional high schools. However, practical application of these subjects makes them more interesting and more valuable to the students.

Another reason students drop out is to support their families. By participating in a program in which they are paid a wage and then entering that job full time, they no longer need to drop out for this reason. It is necessary for many students to contribute financially to the family: by getting a job earlier, they can do this. Joining the work force early also provides students with financial skills gained through experience with money management.

The belief of most Americans that everyone needs to have a college education is outdated. The United States needs skilled employees at all levels, from the highly technical to the practical day to day services society needs to sustain its current standard of living. Germany is doing this through its apprenticeship programs which have proven to be economically successful for both businesses and workers. If the State of Georgia put technical high schools in every county, businesses would get employees with the skills they need; young people would get into good paying jobs earlier, and schools would have fewer dropouts.

Works Cited

“The Forgotten Half Revisited: American Youth and Young Families, 1988-2008.” American Youth Policy Forum . N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Apr. 2012.

Karaim, Reed. “Youth Unemployment.” CQ Global Researcher 6 Mar. 2012: 105-28. Web. 21 Apr. 2012.

Lerman, Robert I. “Building a Wider Skills Net for Workers: A Range of Skills Beyond Conventional Schooling Are Critical to Success in the Job Market, and New Educational Approaches Should Reflect These Noncognitive Skills and Occupational Qualifications.” Issues in Science and Technology 24.4 (2008): 65+. Gale Opposing Viewpoints in Context . Web. 21 Apr. 2012.

Lewis, Anne C. “Support for CTE.” Tech Directions 65.3 (2005): 5-6. Academic Search Complete. Web. 11 Apr. 2012.

McCaffrey, Shannon, and Nancy Badertscher. “Painful Truth in Grad Rates.” Atlanta Journal-Constitution 15 Apr. 2012: A1+. Print.

Persing, Thomas E. “The Role of Apprenticeship Programs.” On Common Ground . Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute, Fall 1994. Web. 16 Apr. 2012.

Rawe, Julie. “How Germany Keeps Kids From Dropping Out.” Time Magazine U.S. Time Magazine, 11 Apr. 2006. Web. 16 Apr. 2012.

Rogers, Betsy. “Remembering the ‘Forgotten Half.’” Washington University in St. Louis Magazine Spring 2005. Web. 21 Apr. 2012.

Taylor, Timothy. “Apprenticeships for the U.S. Economy.” Conversableeconomist.blogspot.com. Conversable Economist , 18 Oct. 2011. Web. 16 Apr. 2012.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.1.6: Changing Attitudes Through Persuasion

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 131581

Learning Objectives

- Outline how persuasion is determined by the choice of effective communicators and effective messages.

- Review the conditions under which attitudes are best changed using spontaneous versus thoughtful strategies.

- Summarize the variables that make us more or less resistant to persuasive appeals.

Every day we are bombarded by advertisements of every sort. The goal of these ads is to sell us cars, computers, video games, clothes, and even political candidates. The ads appear on billboards, website popup ads, TV infomercials, and…well, you name it! It’s been estimated that the average American child views over 40,000 TV commercials every year and that over $400 billion is spent annually on advertising worldwide (Strasburger, 2001).

There is substantial evidence that advertising is effective in changing attitudes. After the R. J. Reynolds Company started airing its Joe Camel ads for cigarettes on TV in the 1980s, Camel cigarettes’ share of sales among children increased dramatically. But persuasion can also have more positive outcomes. Persuasion is used to encourage people to donate to charitable causes, to volunteer to give blood, and to engage in healthy behaviors. The dramatic decrease in cigarette smoking (from about half of the U.S. population who smoked in 1970 to only about a quarter who smoke today) is due in large part to effective advertising campaigns.

Section 3.2 considers how we can change people’s attitudes. If you are interested in learning how to persuade others, you may well get some ideas in this regard. If you think that advertisers and marketers have too much influence, then this section will help you understand how to resist such attempts at persuasion. Following the approach used by some of the earliest social psychologists and that still forms the basis of thinking about the power of communication, we will consider which communicators can deliver the most effective messages to which types of message recipients (Hovland, Lumsdaine, & Sheffield (1949).

Choosing Effective Communicators

In order to be effective persuaders, we must first get people’s attention, then send an effective message to them, and then ensure that they process the message in the way we would like them to. Furthermore, to accomplish these goals, persuaders must take into consideration the cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects of their methods. Persuaders also must understand how the communication they are presenting relates to the message recipient—his or her motivations, desires, and goals.

Research has demonstrated that the same message will be more effective if is delivered by a more persuasive communicator. In general we can say that communicators are more effective when they help their recipients feel good about themselves—that is, by appealing to self-concern. For instance, attractive communicators are frequently more effective persuaders than are unattractive communicators. Attractive communicators create a positive association with the product they are trying to sell and put us in a good mood, which makes us more likely to accept their messages. And as the many marketers who include free gifts, such as mailing labels or small toys, in their requests for charitable donations well know, we are more likely to respond to communicators who offer us something personally beneficial.

We’re also more persuaded by people who are similar to us in terms of opinions and values than by those whom we perceive as being different. This is of course why advertisements targeted at teenagers frequently use teenagers to present the message, and why advertisements targeted at the elderly use older communicators.

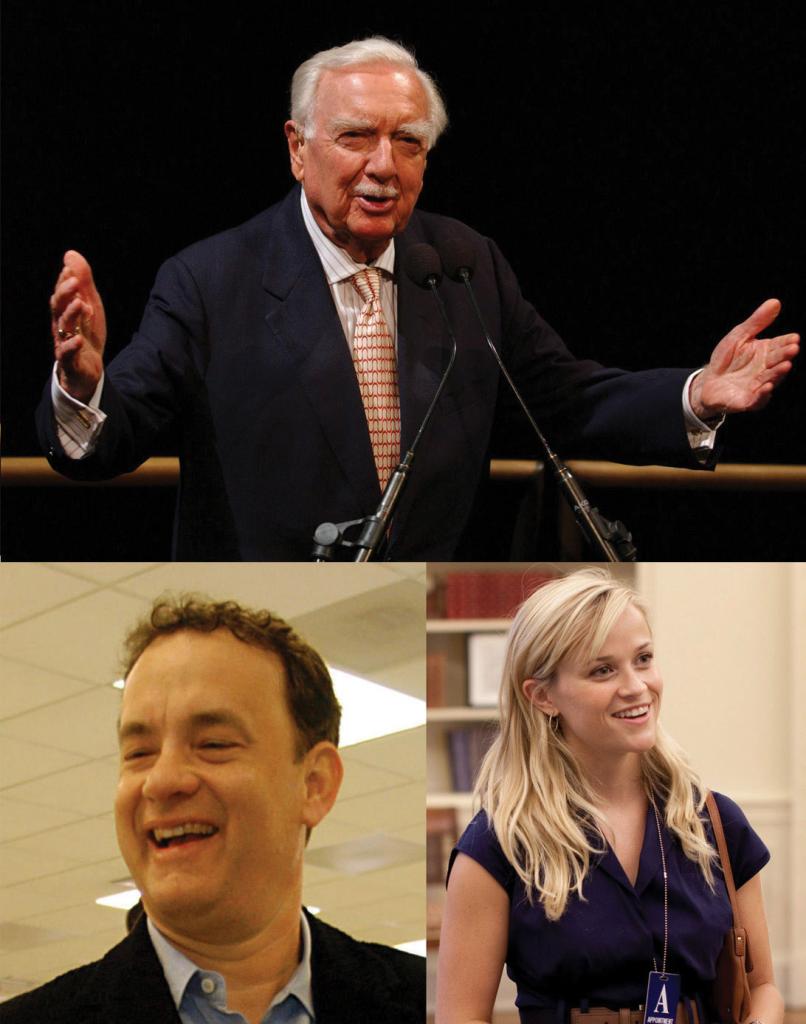

When communicators are perceived as attractive and similar to us, we tend to like them. And we also tend to trust the people that we like. The success of Tupperware parties, in which friends get together to buy products from other friends, may be due more to the fact that people like the “salesperson” than to the nature of the product. People such as the newscaster Walter Cronkite and the film stars Tom Hanks and Reese Witherspoon have been used as communicators for products in part because we see them as trustworthy and thus likely to present an unbiased message. Trustworthy communicators are effective because they allow us to feel good about ourselves when we accept their message, often without critically evaluating its content (Priester & Petty, 2003).

People such as the newscaster Walter Cronkite and the film stars Tom Hanks and Reese Witherspoon have been used as communicators for products in part because we see them as trustworthy and thus likely to present an unbiased message. Wikimedia Commons – public domain; Wikimedia Commons – public domain; Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Expert communicators may sometimes be perceived as trustworthy because they know a lot about the product they are selling. When a doctor recommends that we take a particular drug, we are likely to be influenced because we know that he or she has expertise about the effectiveness of drugs. It is no surprise that advertisers use race car drivers to sell cars and basketball players to sell athletic shoes.

Although expertise comes in part from having knowledge, it can also be communicated by how one presents a message. Communicators who speak confidently, quickly, and in a straightforward way are seen as more expert than those who speak in a more hesitating and slower manner. Taking regular speech and speeding it up by deleting very small segments of it, so that it sounds the same but actually goes faster, makes the same communication more persuasive (MacLachlan & Siegel, 1980; Moore, Hausknecht, & Thamodaran, 1986). This is probably in part because faster speech makes the communicator seem more like an expert but also because faster speech reduces the listener’s ability to come up with counterarguments as he or she listens to the message (Megehee, Dobie, & Grant, 2003). Effective speakers frequently use this technique, and some of the best persuaders are those who speak quickly.

Although expert communicators are expected to know a lot about the product they are endorsing, they may not be seen as trustworthy if their statements seem to be influenced by external causes. People who are seen to be arguing in their own self-interest (for instance, an expert witness who is paid by the lawyers in a case or a celebrity who is paid for her endorsement of a product) may be ineffective because we may discount their communications (Eagly, Wood, & Chaiken, 1978; Wood & Eagly, 1981). On the other hand, when a person presents a message that goes against external causes, for instance by arguing in favor of an opinion to a person who is known to disagree with it, we see the internal states (that the individual really believes in the message he or she is expressing) as even more powerful.

Communicators also may be seen as biased if they present only one side of an issue while completely ignoring the potential problems or counterarguments to the message. In these cases people who are informed about both sides of the topic may see the communicator as attempting to unfairly influence them.

Although we are generally very aware of the potential that communicators may deliver messages that are inaccurate or designed to influence us, and we are able to discount messages that come from sources that we do not view as trustworthy, there is one interesting situation in which we may be fooled by communicators. This occurs when a message is presented by someone that we perceive as untrustworthy. When we first hear that person’s communication we appropriately discount it and it therefore has little influence on our opinions. However, over time there is a tendency to remember the content of a communication to a greater extent than we remember the source of the communication. As a result, we may forget over time to discount the remembered message. This attitude change that occurs over time is known as the sleeper effect (Kumkale & Albarracín, 2004).

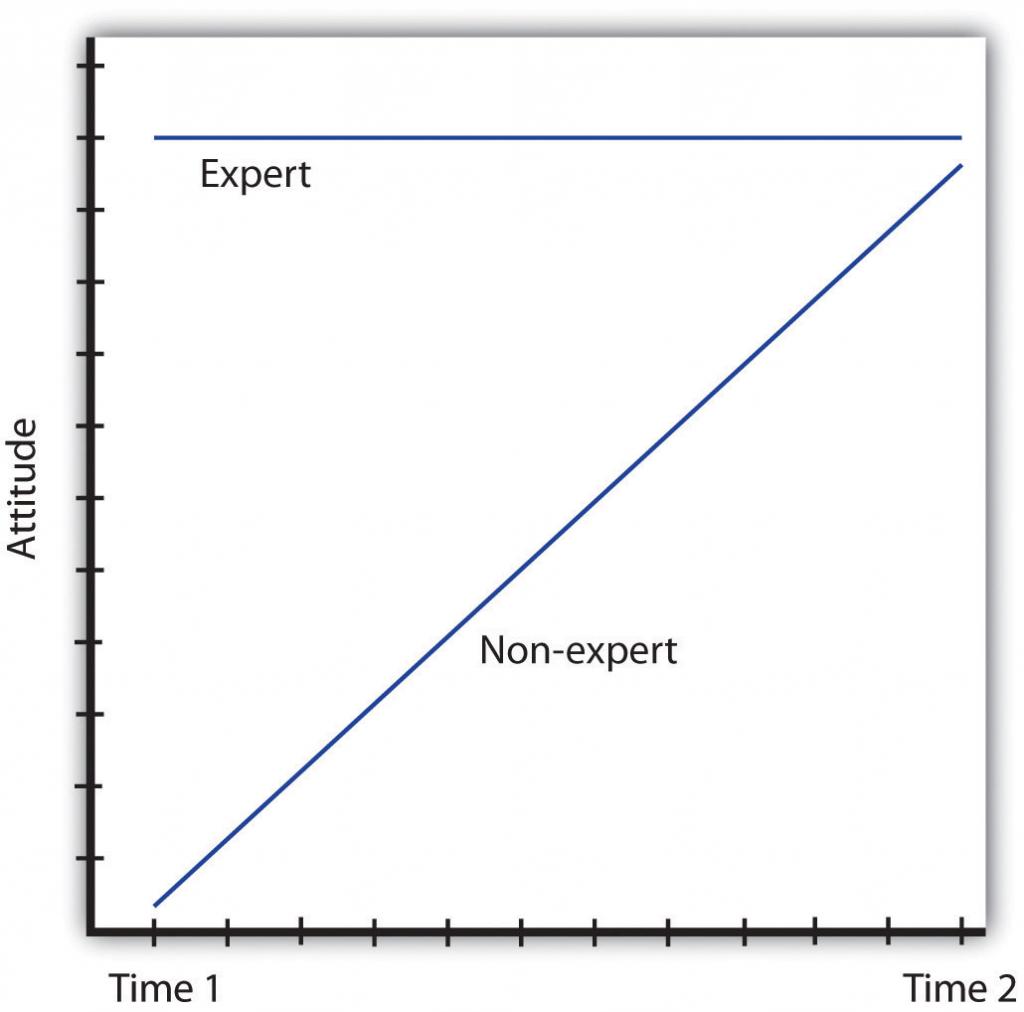

The sleeper effect occurs when we initially discount the message given by an untrustworthy or nonexpert communicator but, over time, we remember the content of the message and forget its source. The result is attitude change in the direction of the initially discounted message.

Perhaps you’ve experienced the sleeper effect. Once, I told my friends a story that I had read about one of my favorite movie stars. Only later did I remember that I had read the story while I was waiting in the supermarket checkout line, and that I had read it in the National Enquirer ! I knew that the story was probably false because the newspaper is considered unreliable, but I had initially forgotten to discount that fact because I did not remember the source of the information. The sleeper effect is diagrammed in Figure 5.2.

Creating Effective Communications

Once we have chosen a communicator, the next step is to determine what type of message we should have him or her deliver. Neither social psychologists nor advertisers are so naïve as to think that simply presenting a strong message is sufficient. No matter how good the message is, it will not be effective unless people pay attention to it, understand it, accept it, and incorporate it into their self-concept. This is why we attempt to choose good communicators to present our ads in the first place, and why we tailor our communications to get people to process them the way we want them to.

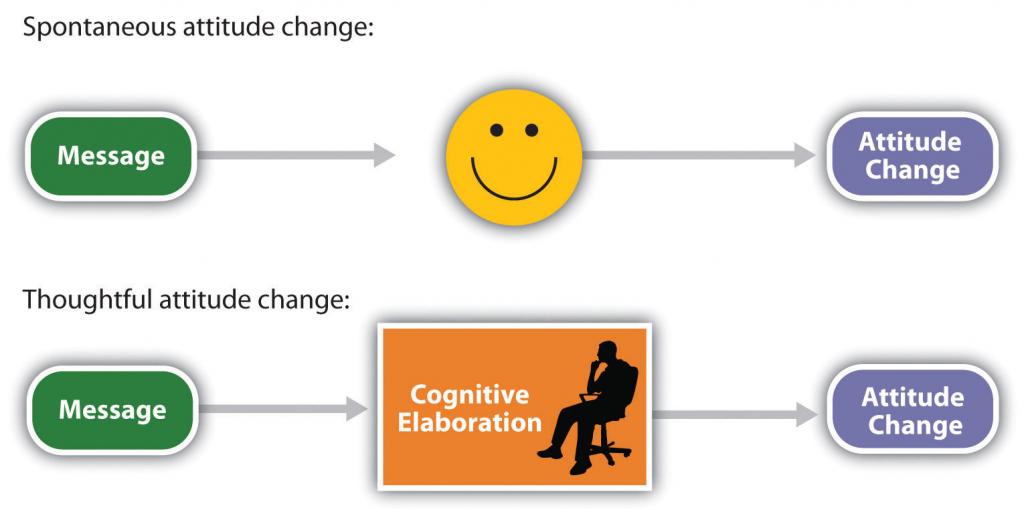

Spontaneous attitude change occurs as a direct or affective response to the message, whereas thoughtful attitude change is based on our cognitive elaboration of the message.

The messages that we deliver may be processed either spontaneously (other terms for this include peripherally or heuristically —Chen & Chaiken, 1999; Petty & Wegener, 1999) or thoughtfully (other terms for this include centrally or systematically ). Spontaneous processing is direct, quick, and often involves affective responses to the message. Thoughtful processing, on the other hand, is more controlled and involves a more careful cognitive elaboration of the meaning of the message (Figure 5.3). The route that we take when we process a communication is important in determining whether or not a particular message changes attitudes.

Spontaneous Message Processing

Because we are bombarded with so many persuasive messages—and because we do not have the time, resources, or interest to process every message fully—we frequently process messages spontaneously. In these cases, if we are influenced by the communication at all, it is likely that it is the relatively unimportant characteristics of the advertisement, such as the likeability or attractiveness of the communicator or the music playing in the ad, that will influence us.

If we find the communicator cute, if the music in the ad puts us in a good mood, or if it appears that other people around us like the ad, then we may simply accept the message without thinking about it very much (Giner-Sorolla & Chaiken, 1997). In these cases, we engage in spontaneous message processing , in which we accept a persuasion attempt because we focus on whatever is most obvious or enjoyable, without much attention to the message itself . Shelley Chaiken (1980) found that students who were not highly involved in a topic, because it did not affect them personally, were more persuaded by a likeable communicator than by an unlikeable one, regardless of whether the communicator presented a good argument for the topic or a poor one. On the other hand, students who were more involved in the decision were more persuaded by the better than by the poorer message, regardless of whether the communicator was likeable or not—they were not fooled by the likeability of the communicator.

You might be able to think of some advertisements that are likely to be successful because they create spontaneous processing of the message by basing their persuasive attempts around creating emotional responses in the listeners. In these cases the advertisers use associational learning to associate the positive features of the ad with the product. Television commercials are often humorous, and automobile ads frequently feature beautiful people having fun driving beautiful cars. The slogans “The joy of cola!” “Coke adds life!” and “Be a Pepper!” are good ads in part because they successfully create positive affect in the listener.

In some cases emotional ads may be effective because they lead us to watch or listen to the ad rather than simply change the channel or doing something else. The clever and funny TV ads that are shown during the Super Bowl broadcast every year are likely to be effective because we watch them, remember them, and talk about them with others. In this case the positive affect makes the ads more salient, causing them to grab our attention. But emotional ads also take advantage of the role of affect in information processing. We tend to like things more when we are in good moods, and—because positive affect indicates that things are OK—we process information less carefully when we are in good moods. Thus the spontaneous approach to persuasion is particularly effective when people are happy (Sinclair, Mark, & Clore, 1994), and advertisers try to take advantage of this fact.

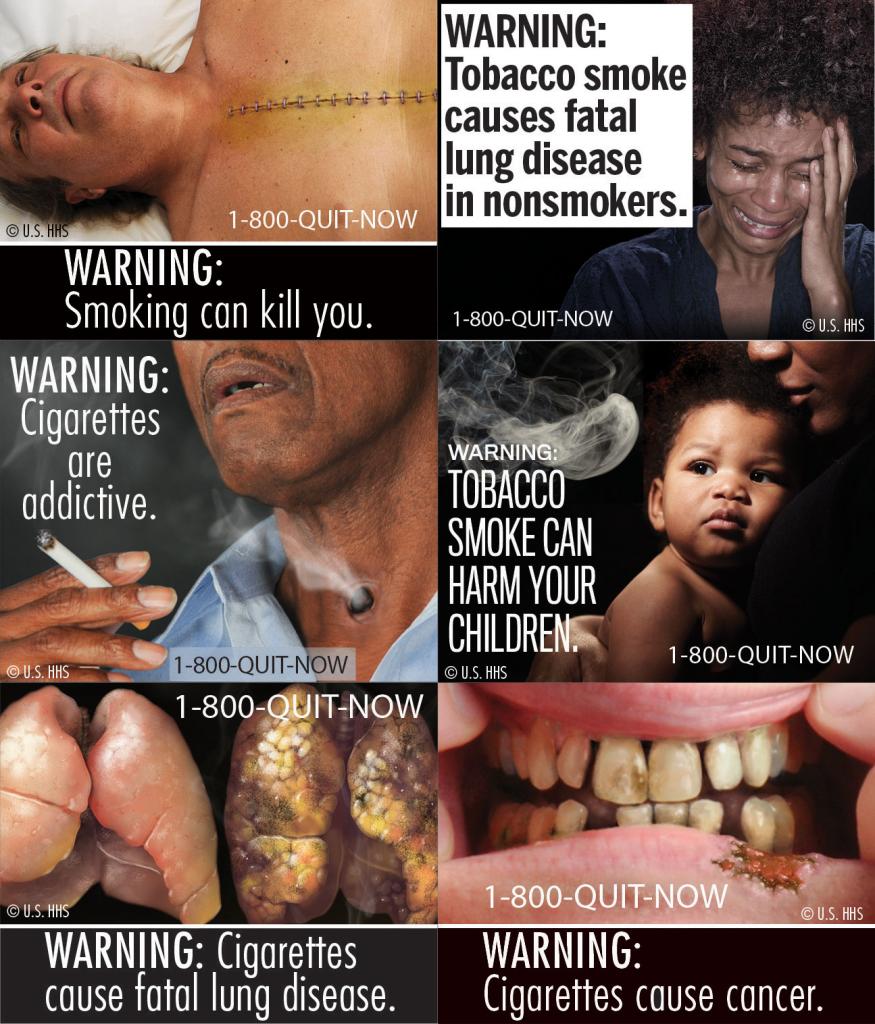

Another type of ad that is based on emotional responses is the one that uses fear appeals, such as ads that show pictures of deadly automobile accidents to encourage seatbelt use or images of lung cancer surgery to decrease smoking. By and large, fearful messages are persuasive (Das, de Wit, & Stroebe, 2003; Perloff, 2003; Witte & Allen, 2000). Again, this is due in part to the fact that the emotional aspects of the ads make them salient and lead us to attend to and remember them. And fearful ads may also be framed in a way that leads us to focus on the salient negative outcomes that have occurred for one particular individual. When we see an image of a person who is jailed for drug use, we may be able to empathize with that person and imagine how we would feel if it happened to us. Thus this ad may be more effective than more “statistical” ads stating the base rates of the number of people who are jailed for drug use every year.

Fearful ads also focus on self-concern, and advertisements that are framed in a way that suggests that a behavior will harm the self are more effective than the same messages that are framed more positively. Banks, Salovey, Greener, and Rothman (1995) found that a message that emphasized the negative aspects of not getting a breast cancer screening mammogram (“not getting a mammogram can cost you your life”) was more effective than a similar message that emphasized the positive aspects (“getting a mammogram can save your life”) in getting women to have a mammogram over the next year. These findings are consistent with the general idea that the brain responds more strongly to negative affect than it does to positive affect (Ito, Larsen, Smith, & Cacioppo, 1998).

Although laboratory studies generally find that fearful messages are effective in persuasion, they have some problems that may make them less useful in real-world advertising campaigns (Hastings, Stead, & webb, 2004). Fearful messages may create a lot of anxiety and therefore turn people off to the message (Shehryar & Hunt, 2005). For instance, people who know that smoking cigarettes is dangerous but who cannot seem to quit may experience particular anxiety about their smoking behaviors. Fear messages are more effective when people feel that they know how to rectify the problem, have the ability to actually do so, and take responsibility for the change. Without some feelings of self-efficacy, people do not know how to respond to the fear (Aspinwall, Kemeny, Taylor, & Schneider, 1991). Thus if you want to scare people into changing their behavior, it may be helpful if you also give them some ideas about how to do so, so that they feel like they have the ability to take action to make the changes (Passyn & Sujan, 2006).

Source: www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/ucm259214.htm#High_Resolution_Image_Formats

Thoughtful Message Processing

When we process messages only spontaneously, our feelings are more likely to be important, but when we process messages thoughtfully, cognition prevails. When we care about the topic, find it relevant, and have plenty of time to spend thinking about the communication, we are likely to process the message more deliberatively, carefully, and thoughtfully (Petty & Briñol, 2008). In this case we elaborate on the communication by considering the pros and cons of the message and questioning the validity of the communicator and the message. Thoughtful message processing occurs when we think about how the message relates to our own beliefs and goals and involves our careful consideration of whether the persuasion attempt is valid or invalid.

When an advertiser presents a message that he or she hopes will be processed thoughtfully, the goal is to create positive cognitions about the attitude object in the listener. The communicator mentions positive features and characteristics of the product and at the same time attempts to downplay the negative characteristics. When people are asked to list their thoughts about a product while they are listening to, or right after they hear, a message, those who list more positive thoughts also express more positive attitudes toward the product than do those who list more negative thoughts (Petty & Briñol, 2008). Because the thoughtful processing of the message bolsters the attitude, thoughtful processing helps us develop strong attitudes, which are therefore resistant to counterpersuasion (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981).

Which Route Do We Take: Thoughtful or Spontaneous?

Both thoughtful and spontaneous messages can be effective, but it is important to know which is likely to be better in which situation and for which people. When we can motivate people to process our message carefully and thoughtfully, then we are going to be able to present our strong and persuasive arguments with the expectation that our audience will attend to them. If we can get the listener to process these strong arguments thoughtfully, then the attitude change will likely be strong and long lasting. On the other hand, when we expect our listeners to process only spontaneously—for instance, if they don’t care too much about our message or if they are busy doing other things—then we do not need to worry so much about the content of the message itself; even a weak (but interesting) message can be effective in this case. Successful advertisers tailor their messages to fit the expected characteristics of their audiences.

In addition to being motivated to process the message, we must also have the ability to do so. If the message is too complex to understand, we may rely on spontaneous cues, such as the perceived trustworthiness or expertise of the communicator (Hafer, Reynolds, & Obertynski, 1996), and ignore the content of the message. When experts are used to attempt to persuade people—for instance, in complex jury trials—the messages that these experts give may be very difficult to understand. In these cases the jury members may rely on the perceived expertise of the communicator rather than his or her message, being persuaded in a relatively spontaneous way. In other cases we may not be able to process the information thoughtfully because we are distracted or tired—in these cases even weak messages can be effective, again because we process them spontaneously (Petty, Wells & Brock, 1976).

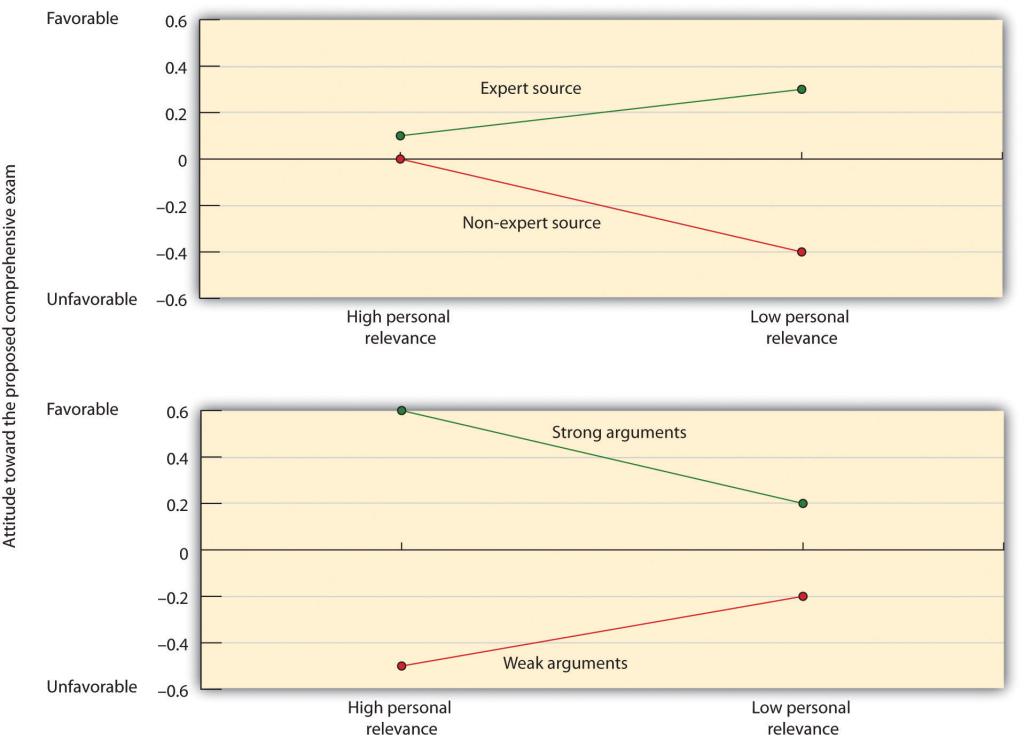

Petty, Cacioppo, and Goldman (1981) showed how different motivations may lead to either spontaneous or thoughtful processing. In their research, college students heard a message suggesting that the administration at their college was proposing to institute a new comprehensive exam that all students would need to pass in order to graduate and then rated the degree to which they were favorable toward the idea. The researchers manipulated three independent variables:

- Message strength. The message contained either strong arguments (persuasive data and statistics about the positive effects of the exams at other universities) or weak arguments (relying only on individual quotations and personal opinions).

- Source expertise. The message was supposedly prepared either by an expert source (the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, which was chaired by a professor of education at Princeton University) or by a nonexpert source (a class at a local high school).

- Personal relevance. The students were told either that the new exam would begin before they graduated ( high personal relevance ) or that it would not begin until after they had already graduated ( low personal relevance ).

As you can see in Figure 5.4, Petty and his colleagues found two interaction effects. The top panel of the figure shows that the students in the high personal relevance condition (left side) were not particularly influenced by the expertise of the source, whereas the students in the low personal relevance condition (right side) were. On the other hand, as you can see in the bottom panel, the students who were in the high personal relevance condition (left side) were strongly influenced by the quality of the argument, but the low personal involvement students (right side) were not.

These findings fit with the idea that when the issue was important, the students engaged in thoughtful processing of the message itself. When the message was largely irrelevant, they simply used the expertise of the source without bothering to think about the message.

Petty, Cacioppo, and Goldman (1981) found that students for whom an argument was not personally relevant based their judgments on the expertise of the source (spontaneous processing), whereas students for whom the decision was more relevant were more influenced by the quality of the message (thoughtful processing).

Because both thoughtful and spontaneous approaches can be successful, advertising campaigns, such as those used by the Obama presidential campaign, carefully make use of both spontaneous and thoughtful messages. In some cases, the messages showed Obama smiling, shaking hands with people around him, and kissing babies; in other ads Obama was shown presenting his plans for energy efficiency and climate change in more detail.

Preventing Persuasion

To this point we have focused on techniques designed to change attitudes. But it is also useful to develop techniques that prevent attitude change. If you are hoping that Magritte will never puff that first cigarette, then you might be interested in knowing what her parents might be able to do to prevent it from happening.

One approach to improving an individual’s ability to resist persuasion is to help the person create a strong attitude. Strong attitudes are more difficult to change than are weak attitudes, and we are more likely to act on our strong attitudes. This suggests that Magritte’s parents might want help Magritte consider all the reasons that she should not smoke and develop strong negative affect about smoking. As Magritte’s negative thoughts and feelings about smoking become more well-defined and more integrated into the self-concept, they should have a bigger influence on her behavior.

One method of increasing attitude strength involves forewarning : giving people a chance to develop a resistance to persuasion by reminding them that they might someday receive a persuasive message, and allowing them to practice how they will respond to influence attempts (Sagarin & Wood, 2007). Magritte’s parents might want to try the forewarning approach. After the forewarning, when Magritte hears the smoking message from her peers, she may be less influenced by it because she was aware ahead of time that the persuasion would likely occur and had already considered how to resist it.

Forewarning seems to be particularly effective when the message that is expected to follow attacks an attitude that we care a lot about. In these cases the forewarning prepares us for action—we bring up our defenses to maintain our existing beliefs. When we don’t care much about the topic, on the other hand, we may simply change our belief before the appeal actually comes (Wood & Quinn, 2003).

Forewarning can be effective in helping people respond to persuasive messages that they will receive later.

A similar approach is to help build up the cognitive component of the attitude by presenting a weak attack on the existing attitude with the goal of helping the person create counterarguments about a persuasion attempt that is expected to come in the future. Just as an inoculation against the flu gives us a small dose of the influenza virus that helps prevent a bigger attack later, giving Magritte a weak argument to persuade her to smoke cigarettes can help her develop ways to resist the real attempts when they come in the future. This procedure—known as inoculation — involves building up defenses against persuasion by mildly attacking the attitude position (Compton & Pfau, 2005; McGuire, 1961). We would begin by telling Magritte the reasons that her friends might think that she should smoke (for instance, because everyone is doing it and it makes people look “cool”), therefore allowing her to create some new defenses against persuasion. Thinking about the potential arguments that she might receive and preparing the corresponding counterarguments will make the attitude stronger and more resistant to subsequent change attempts.

One difficulty with forewarning and inoculation attempts is that they may boomerang. If we feel that another person—for instance, a person who holds power over us—is attempting to take away our freedom to make our own decisions, we may respond with strong emotion, completely ignore the persuasion attempt, and perhaps even engage in the opposite behavior. Perhaps you can remember a time when you felt like your parents or someone else who had some power over you put too much pressure on you, and you rebelled against them.

The strong emotional response that we experience when we feel that our freedom of choice is being taken away when we expect that we should have choice is known as psychological reactance (Brehm, 1966; Miron & Brehm, 2006). If Magritte’s parents are too directive in their admonitions about not smoking, she may feel that they do not trust her to make her own decisions and are attempting to make them for her. In this case she may experience reactance and become more likely to start smoking. Erceg-Hurn and Steed (2011) found that the graphic warning images that are placed on cigarette packs could create reactance in people who viewed them, potentially reducing the warnings’ effectiveness in convincing people to stop smoking.

Given the extent to which our judgments and behaviors are frequently determined by processes that occur outside of our conscious awareness, you might wonder whether it is possible to persuade people to change their attitudes or to get people to buy products or engage in other behaviors using subliminal advertising. Subliminal advertising occurs when a message, such as an advertisement or another image of a brand, is presented to the consumer without the person being aware that a message has been presented—for instance, by flashing messages quickly in a TV show, an advertisement, or a movie (Theus, 1994).

Does Subliminal Advertising Work?

If it were effective, subliminal advertising would have some major advantages for advertisers because it would allow them to promote their product without directly interrupting the consumer’s activity and without the consumer knowing that he or she is being persuaded (Trappey, 1996). People cannot counterargue with, or attempt to avoid being influenced by, messages that they do not know they have received and this may make subliminal advertising particularly effective. Due to fears that people may be influenced to buy products out of their awareness, subliminal advertising has been legally banned in many countries, including Australia, Great Britain, and the United States.

Some research has suggested that subliminal advertising may be effective. Karremans, Stroebe, and Claus (2006) had Dutch college students view a series of computer trials in which a string of letters such as BBBBBBBBB or BBBbBBBBB was presented on the screen and the students were asked to pay attention to whether or not the strings contained a small b . However, immediately before each of the letter strings, the researchers presented either the name of a drink that is popular in Holland (“Lipton Ice”) or a control string containing the same letters as Lipton Ice (“Npeic Tol”). The priming words were presented so quickly (for only about 1/50th of a second) that the participants could not see them.

Then the students were asked to indicate their intention to drink Lipton Ice by answering questions such as “If you would sit on a terrace now, how likely is it that you would order Lipton Ice?” and also to indicate how thirsty they were at this moment. The researchers found that the students who had been exposed to the Lipton Ice primes were significantly more likely to say that they would drink Lipton Ice than were those who had been exposed to the control words, but that this was only true for the participants who said that they were currently thirsty.

On the other hand, other research has not supported the effectiveness of subliminal advertising. Charles Trappey (1996) conducted a meta-analysis in which he combined 23 research studies that had tested the influence of subliminal advertising on consumer choice. The results of his meta-analysis showed that subliminal advertising had a “negligible effect on consumer choice.” Saegert (1987) concluded that “marketing should quit giving subliminal advertising the benefit of the doubt” (p. 107), arguing that the influences of subliminal stimuli are usually so weak that they are normally overshadowed by the person’s own decision making about the behavior.

Even if a subliminal or subtle advertisement is perceived, previous experience with the product or similar products—or even unrelated, more salient stimuli at the moment—may easily overshadow any effect the subliminal message would have had (Moore, 1988). That is, even if we do perceive the “hidden” message, our prior attitudes or our current situation will likely have a stronger influence on our choices, potentially nullifying any effect the subliminal message would have had.

Taken together, the evidence for the effectiveness of subliminal advertising is weak and its effects may be limited to only some people and only some conditions. You probably don’t have to worry too much about being subliminally persuaded in your everyday life even if subliminal ads are allowed in your country. Of course, although subliminal advertising is not that effective, there are plenty of other indirect advertising techniques that are. Many ads for automobiles and alcoholic beverages have sexual connotations, which indirectly (even if not subliminally) associate these positive features with their products. And there are the ever more frequent “product placement” techniques, where images of brands (cars, sodas, electronics, and so forth) are placed on websites and in popular TV shows and movies.

Key Takeaways

- Advertising is effective in changing attitudes, and principles of social psychology can help us understand when and how advertising works.

- Social psychologists study which communicators can deliver the most effective messages to which types of message recipients.

- Communicators are more effective when they help their recipients feel good about themselves. Attractive, similar, trustworthy, and expert communicators are examples of effective communicators.

- Attitude change that occurs over time, particularly when we no longer discount the impact of a low-credibility communicator, is known as the sleeper effect.

- The messages that we deliver may be processed either spontaneously or thoughtfully. When we are processing messages only spontaneously, our feelings are more likely to be important, but when we process the message thoughtfully, cognition prevails.

- Both thoughtful and spontaneous messages can be effective, in different situations and for different people.

- One approach to improving an individual’s ability to resist persuasion is to help the person create a strong attitude. Procedures such as forewarning and inoculation can help increase attitude strength and thus reduce subsequent persuasion.

- Taken together, the evidence for the effectiveness of subliminal advertising is weak, and its effects may be limited to only some people and only some conditions.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Reconsider the effectiveness of the Obama presidential campaign in terms of the principles of persuasion that we have discussed.

- Find and discuss examples of web or TV ads that make use of the principles discussed in this section.

- Visit the Joe Chemo site ( http://www.joechemo.org/about.htm ), designed to highlight and counterargue the negative effects of the Joe Camel cigarette ads. Create a presentation that summarizes the influence of cigarette ads on children.

- Based on our discussion of resistance to persuasion, what techniques would you use to help a child resist the pressure to start smoking or using recreational drugs?

Aspinwall, L. G., Kemeny, M. E., Taylor, S. E., & Schneider, S. G. (1991). Psychosocial predictors of gay men’s AIDS risk-reduction behavior. Health Psychology, 10 (6), 432–444.

Banks, S. M., Salovey, P., Greener, S., & Rothman, A. J. (1995). The effects of message framing on mammography utilization. Health Psychology, 14 (2), 178–184.

Brehm, J. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance . New York, NY: Academic Press.

Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39 (5), 752–766.

Chen, S., & Chaiken, S. (1999). The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. In Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 73–96). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Compton, J. A., & Pfau, M. (2005). Inoculation theory of resistance to influence at maturity: Recent progress in theory development and application and suggestions for future research. Communication Yearbook, 29 , 97–145.

Das, E. H. H. J., de Wit, J. B. F., & Stroebe, W. (2003). Fear appeals motivate acceptance of action recommendations: Evidence for a positive bias in the processing of persuasive messages. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29 (5), 650–664.

Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., & Chaiken, S. (1978). Causal inferences about communicators and their effect on opinion change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36 (4), 424–435.

Erceg-Hurn, D. M., & Steed, L. G. (2011). Does exposure to cigarette health warnings elicit psychological reactance in smokers? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41 (1), 219–237.

Giner-Sorolla, R., & Chaiken, S. (1997). Selective use of heuristic and systematic processing under defense motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23 (1), 84–97.

Hafer, C. L., Reynolds, K. L., & Obertynski, M. A. (1996). Message comprehensibility and persuasion: Effects of complex language in counterattitudinal appeals to laypeople. Social Cognition, 14 , 317–337.

Hastings, G., Stead, M., & webb, J. (2004). Fear appeals in social marketing: Strategic and ethical reasons for concern. Psychology and Marketing, 21 (11), 961–986. doi: 10.1002/mar.20043.

Hovland, C. I., Lumsdaine, A. A., & Sheffield, F. D. (1949). Experiments on mass communication . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ito, T. A., Larsen, J. T., Smith, N. K., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1998). Negative information weighs more heavily on the brain: The negativity bias in evaluative categorizations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75 (4), 887–900.

Karremans, J. C., Stroebe, W., & Claus, J. (2006). Beyond Vicary’s fantasies: The impact of subliminal priming and brand choice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42 (6), 792–798.

Kumkale, G. T., & Albarracín, D. (2004). The sleeper effect in persuasion: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 130 (1), 143–172. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.143.

MacLachlan, J. H., & Siegel, M. H. (1980). Reducing the costs of TV commercials by use of time compressions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17 (1), 52–57.

McGuire, W. J. (1961). The effectiveness of supportive and refutational defenses in immunizing defenses. Sociometry, 24 , 184–197.

Megehee, C. M., Dobie, K., & Grant, J. (2003). Time versus pause manipulation in communications directed to the young adult population: Does it matter? Journal of Advertising Research, 43 (3), 281–292.

Miron, A. M., & Brehm, J. W. (2006). Reaktanz theorie—40 Jahre spärer. Zeitschrift fur Sozialpsychologie, 37 (1), 9–18. doi: 10.1024/0044-3514.37.1.9.

Moore, D. L., Hausknecht, D., & Thamodaran, K. (1986). Time compression, response opportunity, and persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (1), 85–99.

Moore, T. E. (1988). The case against subliminal manipulation. Psychology and Marketing, 5 (4), 297–316.

Passyn, K., & Sujan, M. (2006). Self-accountability emotions and fear appeals: Motivating behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 32 (4), 583–589. doi: 10.1086/500488.

Perloff, R. M. (2003). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Petty, R. E., & Briñol, P. (2008). Persuasion: From single to multiple to metacognitive processes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3 (2), 137–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00071.x.

Petty, R. E., & Wegener, D. T. (1999). The elaboration likelihood model: Current status and controversies. In Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 37–72). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Goldman, R. (1981). Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41 (5), 847–855.

Petty, R. E., Wells, G. L., & Brock, T. C. (1976). Distraction can enhance or reduce yielding to propaganda: Thought disruption versus effort justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34 (5), 874–884.

Priester, J. R., & Petty, R. E. (2003). The influence of spokesperson trustworthiness on message elaboration, attitude strength, and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13 (4), 408–421.

Saegert, J. (1987). Why marketing should quit giving subliminal advertising the benefit of the doubt. Psychology and Marketing, 4 (2), 107–121.

Sagarin, B. J., & Wood, S. E. (2007). Resistance to influence. In A. R. Pratkanis (Ed.), The science of social influence: Advances and future progress (pp. 321–340). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Shehryar, O., & Hunt, D. M. (2005). A terror management perspective on the persuasiveness of fear appeals. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15 (4), 275–287. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1504_2.

Sinclair, R. C., Mark, M. M., & Clore, G. L. (1994). Mood-related persuasion depends on (mis)attributions. Social Cognition, 12 (4), 309–326.

Strasburger, V. C. (2001). Children and TV advertising: Nowhere to run, nowhere to hide. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 22 (3), 185–187.

Theus, K. T. (1994). Subliminal advertising and the psychology of processing unconscious stimuli: A review of research. Psychology and Marketing, 11 (3), 271–291.

Trappey, C. (1996). A meta-analysis of consumer choice and subliminal advertising. Psychology and Marketing, 13 (5), 517–531.

Witte, K., & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior, 27 (5), 591–615.

Wood, W., & Eagly, A. (1981). Stages in the analysis of persuasive messages: The role of causal attributions and message comprehension. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40 (2), 246–259.

Wood, W., & Quinn, J. M. (2003). Forewarned and forearmed? Two meta-analysis syntheses of forewarnings of influence appeals. Psychological Bulletin, 129 (1), 119–138.

17.5 Writing Process: Thinking Critically and Writing Persuasively About Images

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Develop a writing project through multiple drafts.

- Employ a variety of drafting strategies to complete an analysis of images.

- Apply aspects of visual rhetoric to a writing project.

- Participate in the collaborative and social aspects of writing processes.

- Give and act effectively on productive feedback.

In this section, you will combine what you learned earlier about reflecting on and analyzing images with another way of writing about images: writing persuasively, or persuading. Like reflecting and analyzing, writing persuasively requires clear, vivid descriptions of the technical aspects of an artwork, such as point of view, arrangement, color, and symbolism, as explained in Glance at Genre: Relationship Between Image and Rhetoric . Remember that reflecting on an image helps you make sense of both the image and your experience from different perspectives. Reading other people’s reflections expands your universe of experience. Analyzing images improves your critical thinking skills by synthesizing description, reflection, and logical thinking to determine what an image’s design elements mean. You write persuasively about images when you determine that an image’s meaning has or does not have a value (that you define) for its viewers. For example, Leo Davis, in his analysis of Dancing Sailors in Annotated Student Sample , determines the homoerotic message in the image and the painter’s tone or attitude toward his subject. You can also extend the scope of persuasion to make a recommendation about the status or merit of the work, as you will do in this assignment.

Writing Persuasively about Images

Like reflection, persuasion starts with context and description and can include personal reflections. The difference is primarily in the purpose and often the tone, or attitude toward the subject and audience. The purpose generally falls into one of three categories:

- What is the image’s value? In the art world, these discussions are commonplace. Major publications such as the New Yorker or Harper’s Magazine publish reviews of artists, galleries, and exhibitions. Critics and scholars argue that such discussions serve to establish a society’s values and to benchmark the limits of what a society will and will not tolerate. Certainly, 2020 witnessed an explosion of such conversations. Protestors created images meant for display on public property, many of which were identified as graffiti or acts of vandalism; streets and other locations were renamed to reflect a growing awareness of the role that Black excellence has played in America’s history; and monuments and memorials relating to injustice were reevaluated, vandalized, and removed.

- What happened? Forensic arguments often relate to legal situations, in which lawyers, judges, and juries try to determine what happened and how to respond. In the case of images, these techniques are applied to assess the circumstances of an image’s creation as well as its critical and modern reception.

- What should happen? In the public sector, officials decide whether to fund artistic works. In the private sector, companies decide on images that faithfully represent their brands and values.

In persuasive writing, the purpose is usually revealed in a thesis statement , a single sentence, sometimes two, that defines the author’s position and gives one or more reasons for it. The thesis usually appears at the end of the introduction, although it can occur at the start of either the introduction or the conclusion.

Look again at Figure 17.3 , in which a woman wears a mask that reads, “I can’t breathe.” Table 17.1 below outlines a thesis statement based on that image that might apply to each of the three persuasive writing purposes.

The tone of a persuasive piece can range from educational to impassioned and is largely based on the audience to which it is directed. Most writing about images is done in the neutral tone typically adopted in academic writing, although you may find reviews or essays that are informal and others that are scholarly.

Taking a Side

In ‘Reading’ Images , you read a description of and some reflections on Figure 17.3 , an image of woman wearing a mask reading, “I Can’t Breathe.” You also read a brief analysis of the figure, combining description, historical context, and the visual design element of juxtaposition. Now, in Table 17.2 , look at what two sides of a persuasive discussion of Figure 17.3 might look like.

Summary of Assignment: Writing Persuasively about an Image

Public works projects such as stadiums or convention centers, private developments such as condominiums and shopping centers, and online spaces such as websites and social media platforms all commission artists to create exclusive works for display. These works are intended to reflect the vision of the artist as well as to promote the brand or mission of the space. Imagine that you have been asked to analyze an artist’s work to determine whether the artist should contribute to the development of a local space that you select. Select the work of an artist, either Sara Ludy or another artist whose work is familiar to you or whose work you would like to learn more about. See Further Resources at the end of this chapter for suggested museums to visit in person or online. You can choose from historical figures or living artists. You can even choose an artist who illustrated a graphic novel you have read. Once you have chosen an artist and an image created by that artist, identify the aspects of the work you wish to assess, and support your analysis with technical descriptions of the image. Then, explain why you reached your decision about the artist’s contribution to the selected space.

The parts in this section will take you through the development of a sample essay, using the example of American sculptor James Earle Fraser ’s (1876–1953) Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt . As you follow along in this process, consider how it applies to your topic. Think of the process as divided into these six steps:

- Identify the rhetorical situation.

- Outline the elements you intend to analyze.

- Write an introduction in which you frame the image and the context in which you intend to discuss it.

- As you draft, or before you draft the body of the essay, write topic sentences to identify the focus of each paragraph on a specific technical or contextual aspect of the image.

- Build your paragraphs by describing the relevant elements.

- Conclude by suggesting directions to consider in the future.

Another Lens 1. Visit Sara Ludy’s website and select an image, a rendering, or an animation that speaks to you in some way, and identify the technical aspects you wish to assess. Support your analysis with descriptions of the image, using the vocabulary introduced in “Reading” Images and Glance at Genre: Relationship Between Image and Rhetoric . Then, as an option, consider whether or not you would advise an individual to purchase the work or how you would advise an organization to use it (or not use it) as a representative image—for example, as part of a logo or cover for a publication.

Another Lens 2. Another option for assessing an artist’s work is to compare and contrast this work with another piece, either by Sara Ludy or by a different artist. In doing so, you may consider ways in which the artist and their work have changed over time, or you may consider the influence one artist has on another. Finally, you may consider the images in different contexts through the lens of the artists’ experiences, places in history, personal identities, and artistic practices.

Another Lens 3. Consider a work from a multimodal perspective. If you are interested in the connections of art and culture, consider choosing a piece of historic or contemporary Native American art. You can find information and view images at the websites for the National Museum of the American Indian and the Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Create an infographic or a short video assessing the chosen artwork. An infographic incorporates multiple images and texts into a single image that can be read and understood quickly. A short video could work in a similar way, but the images would be presented sequentially with narration, either spoken or written. Your multimodal work should consider the elements of visual rhetoric discussed throughout this chapter and combine reflection with analysis and persuasion. See Multimodal and Online Writing: Creative Interaction between Text and Image for more information on creating a multimodal work.

Quick Launch: Identify Rhetorical Context

In this writing example, the statue of former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) ( Figure 17.16 ) is analyzed as part of the museum’s decision to keep it or remove it. To begin, the author of this paper (a college student, U.S. citizen, and nursing major) defines the rhetorical situation: purpose, audience, genre, stance, context, and culture. Complete the first step in the assignment as this author has done by consulting the writer’s triangle to sketch out these elements. The writer’s triangle ( Figure 17.17 ) includes audience, genre, and stance and is surrounded by the circle of context/culture. The image allows you to “shorthand” your ideas about these elements during the brainstorming phase, as the author has done beneath the figure.

- Purpose: To analyze the Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt

- Audience: Instructor, fellow students, and U.S. residents

- Genre: Print or digital newsletter or magazine article

- Stance: To support the American Museum of Natural History’s decision to remove the statue of Theodore Roosevelt

- Context: Roosevelt’s presidency and what he accomplished, the relationship between him and the American Museum of Natural History, and the elements of the statue warranting its inclusion or exclusion

- Culture: Critics have said that the statue depicts Black people and Native Americans as conquered and culturally substandard.

Note: Do not confuse context with your rhetorical situation, which, in this case, is a writing assignment for a college course, part of a portfolio and a learning technique in which you practice a type of civil discourse. Meanwhile, context in this case refers to the image—the circumstances of its creation, its technical elements, and how its meaning may change over time.

Sometimes the elements of your rhetorical situation are not made explicit. Signs that you need clarification include the following:

- Trouble getting started

- Difficulty understanding how much background information to provide

- Not knowing which terms are too technical or which need to be defined

For clarity about purpose, audience, genre, or culture, talk to your peers and instructor using the questions in Table 17.3 as a guide.

Regarding context, you may need to do some research on the image:

- Who is the image’s author?

- When was it created?

- For what purpose was it created?

- Has the image been featured in reviews or the news?

- Does the image include important symbols or references?

After you have defined your rhetorical situation, write a working thesis for your paper. Consider using one or a combination of these frames. You may change the phrasing as needed to make your point.

- The artist’s choice of ________ shapes the viewer’s understanding of ________.

- The artist incorporates ________ to symbolize ________.

- The image’s point of view reveals that ________.

- The artist’s style, including ________, suggests that ________.

- The image evokes feelings of ________.

Drafting: The Visual to the Textual

After you have a working thesis, move on to the next major step: outlining the visual elements you intend to analyze. Review the material in “Reading” Images and Glance at Genre: Relationship Between Image and Rhetoric . In the case of the Roosevelt statue, the author has thought about which technical elements of the statue to analyze. The author also has considered the important aspects of the historical context shaping Theodore Roosevelt’s life, presidency, and legacy; the museum and the cultural events in the year the statue was erected; and the cultural events in the year the decision is being made about whether to remove the statue. Remember that you may need to do some additional research to supplement your understanding of the context.

Analyze the Image

With a larger understanding of your subject’s social, political, and cultural context, you can now begin to analyze the image. Limit your descriptions to what you can see and what your observations imply. Consider the following examples:

- Pattern. Identify the repetition of the figures, but note the differences in the ways each is depicted. Identify any lines or other elements that are repeated with variation.

- Point of view. The statue is tall and on a pedestal, requiring viewers to look up or see it from a distance.

- Arrangement. Three figures are arranged in a triangle, suggesting an apex with two supporting angles. Among the figures, the president is tallest, always visible, whereas the two accompanying figures can be seen fully only from either the front or the back. From the side, one or the other is always obscured.

- Symbolism. Each man is dressed in the clothing representative of his homeland. The two to the side are clearly allegorical, whereas the one on top is given individuality and freedom of expression.

- Conclusion. Outline criteria that could be used in the future to determine how symbols of or memorials to historical figures should be assessed.

Write an Introduction

In your introduction, name the artist, the image, and the context in which you intend to discuss it. See the suggestions above for research you may need to do regarding context. If you do research, remember to cite the sources you use because this information did not originate with you. The context may consist of one or two paragraphs, depending on how much information your audience needs to understand your analysis. (This is one reason to have a good understanding of your audience.) This type of introduction appears frequently in visual analyses and persuasive papers.

The two keys to writing a strong context are (1) being selective about what you include and (2) framing your own analysis. For example, Theodore Roosevelt is an important historical figure, and many books have been written about him. Even two paragraphs are insufficient to summarize every relevant detail about him. Likewise, the American Museum of Natural History plays a significant role in documenting mammalian life and has a vital, if at times controversial, role in American scientific history. In the two paragraphs below, the author selects details about the president, the museum, and the statue that both highlight the reasons they are admired and touch on their potential failings. These details are not all-inclusive; they are carefully culled from all of the available information to lead up to the subsequent analysis, which focuses on the reasons to remove the statue. The last sentence in the second paragraph is the thesis, in which the author states her agreement with the museum’s decision.

Contextual Introduction

student sample text Theodore Roosevelt cultivated a hearty outdoor lifestyle, exploring the Dakota Territory in the 1890s, serving as a Rough Rider during the Spanish-American War (1898), and advocating for the conservation of America’s natural resources. Despite criticism for the way in which he acquired the land and rights to construct the Panama Canal, he was widely respected both at home and abroad, being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize (1906) for helping negotiate a peace treaty between Japan and Russia. After his presidency, he traveled extensively throughout Africa and South America, where he killed many animals and returned them to serve as specimens in America’s natural history museums. He was himself shot while campaigning, but as the bullet did not penetrate his lung, he gave his speech regardless, earning him the reputation of a bull moose. end student sample text student sample text A statue commemorating Roosevelt was presented to the public in 1940, two decades after his death, and placed in front of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where Roosevelt served as governor from 1899 to 1900. On one side of Roosevelt, depicted on horseback at the center of the sculpture, walks an African person, and on the other an Indigenous person. All three figures have a straight, proud posture and look directly ahead of them, toward the future. Given its placement, the statue is likely intended as an allegory, depicting the men of two continents—Africa and North America, including its Indigenous people—on a voyage of discovery and learning. Over time, however, and given the hierarchical framing of the image, with the White man clothed in a suit and atop a horse, central to the image, the statue’s meaning has changed, leading to the praiseworthy and long-awaited decision to remove it in 2020. end student sample text

Create Topic Sentences

Use the models below to create your own topic sentences to focus each paragraph on a specific technical or contextual aspect of the image.

- Pattern. The sculpture unites the three figures—four, including the horse—primarily through the repetition of musculature, armor, weapons, and costumes.

- Point of view. Because the sculpture is large, tall, and set on a pedestal, it requires viewers either to look up at it or to regard it from a distance—both postures requiring a certain degree of reverence.

- Arrangement. The sculpture’s three human figures are arranged in a triangle, suggesting an apex with two supporting angles.

- Symbolism. Each man is dressed in the clothing of his homeland, giving each allegorical significance as racial, rather than individual, representations.

Build Body Paragraphs

Support each topic sentence by describing in detail the elements you have chosen to assess. When describing the image, avoid overuse of adjectives and adverbs. Use concrete rather than abstract nouns. Abstract nouns name ideas, such as perspective or theme ; concrete nouns refer to specific, tangible elements, such as triangle , line , or granite . Incorporate strong verbs as well as the necessary forms of to be ( is , are , was , were ). Think about what the features in the image are doing— the ways they interact with one another, the space around them, and the viewer’s relationship to them. Finally, avoid speculation while going beyond description. Keep the discussion rooted in the evidence, and show readers what the evidence points to, what it means.

Sample Body Paragraph: Arrangement