- Python Basics

- Interview Questions

- Python Quiz

- Popular Packages

- Python Projects

- Practice Python

- AI With Python

- Learn Python3

- Python Automation

- Python Web Dev

- DSA with Python

- Python OOPs

- Dictionaries

Different Forms of Assignment Statements in Python

- Statement, Indentation and Comment in Python

- Conditional Statements in Python

- Assignment Operators in Python

- Loops and Control Statements (continue, break and pass) in Python

- Different Ways of Using Inline if in Python

- Difference between "__eq__" VS "is" VS "==" in Python

- Augmented Assignment Operators in Python

- Nested-if statement in Python

- How to write memory efficient classes in Python?

- Difference Between List and Tuple in Python

- A += B Assignment Riddle in Python

- Difference between List VS Set VS Tuple in Python

- Assign Function to a Variable in Python

- Python pass Statement

- Python If Else Statements - Conditional Statements

- Data Classes in Python | Set 5 (post-init)

- Assigning multiple variables in one line in Python

- Assignment Operators in Programming

- What is the difference between = (Assignment) and == (Equal to) operators

We use Python assignment statements to assign objects to names. The target of an assignment statement is written on the left side of the equal sign (=), and the object on the right can be an arbitrary expression that computes an object.

There are some important properties of assignment in Python :-

- Assignment creates object references instead of copying the objects.

- Python creates a variable name the first time when they are assigned a value.

- Names must be assigned before being referenced.

- There are some operations that perform assignments implicitly.

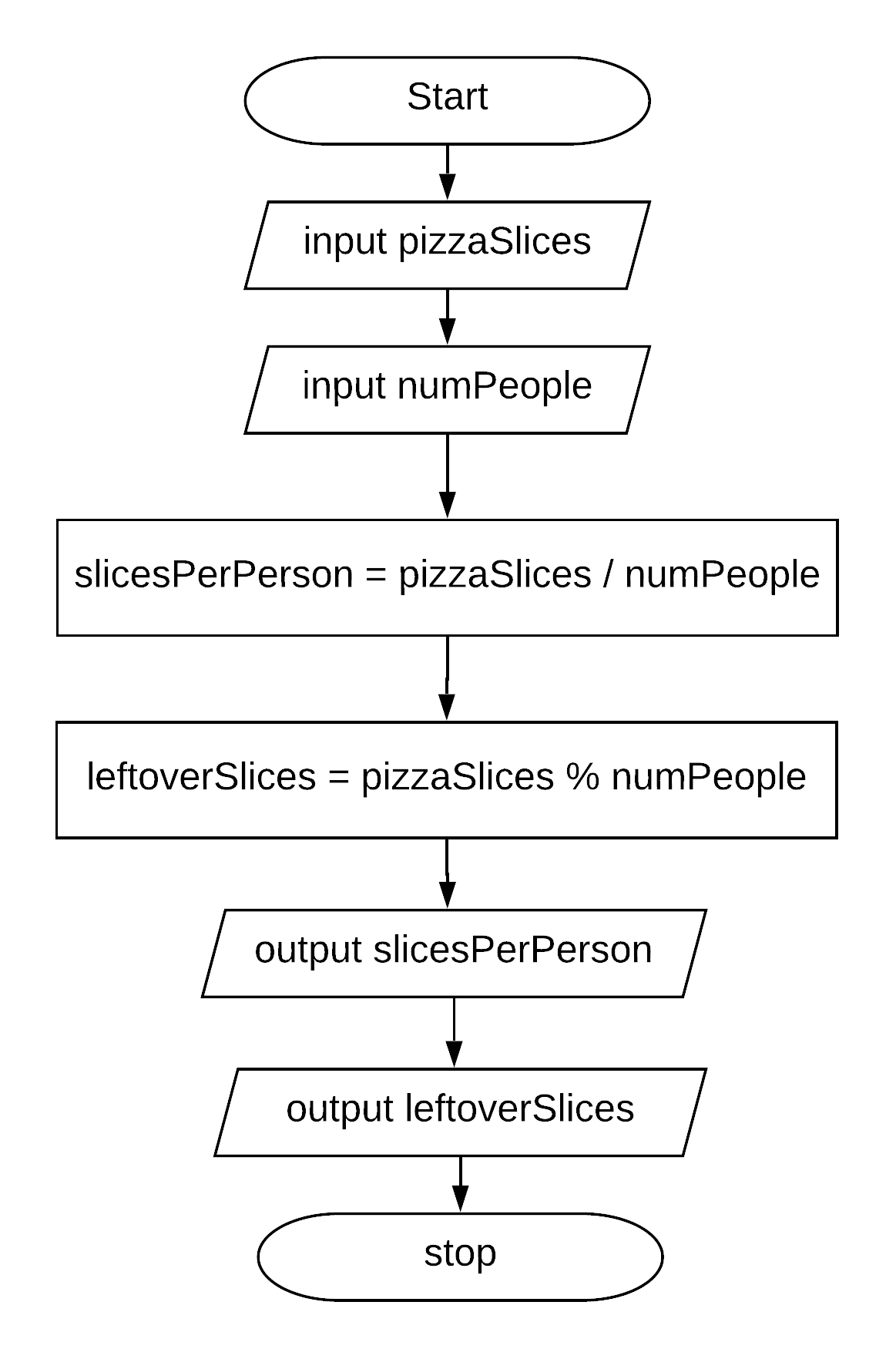

Assignment statement forms :-

1. Basic form:

This form is the most common form.

2. Tuple assignment:

When we code a tuple on the left side of the =, Python pairs objects on the right side with targets on the left by position and assigns them from left to right. Therefore, the values of x and y are 50 and 100 respectively.

3. List assignment:

This works in the same way as the tuple assignment.

4. Sequence assignment:

In recent version of Python, tuple and list assignment have been generalized into instances of what we now call sequence assignment – any sequence of names can be assigned to any sequence of values, and Python assigns the items one at a time by position.

5. Extended Sequence unpacking:

It allows us to be more flexible in how we select portions of a sequence to assign.

Here, p is matched with the first character in the string on the right and q with the rest. The starred name (*q) is assigned a list, which collects all items in the sequence not assigned to other names.

This is especially handy for a common coding pattern such as splitting a sequence and accessing its front and rest part.

6. Multiple- target assignment:

In this form, Python assigns a reference to the same object (the object which is rightmost) to all the target on the left.

7. Augmented assignment :

The augmented assignment is a shorthand assignment that combines an expression and an assignment.

There are several other augmented assignment forms:

Please Login to comment...

Similar reads.

- python-basics

- Python Programs

Improve your Coding Skills with Practice

What kind of Experience do you want to share?

- Python »

- 3.12.3 Documentation »

- The Python Language Reference »

- 7. Simple statements

- Theme Auto Light Dark |

7. Simple statements ¶

A simple statement is comprised within a single logical line. Several simple statements may occur on a single line separated by semicolons. The syntax for simple statements is:

7.1. Expression statements ¶

Expression statements are used (mostly interactively) to compute and write a value, or (usually) to call a procedure (a function that returns no meaningful result; in Python, procedures return the value None ). Other uses of expression statements are allowed and occasionally useful. The syntax for an expression statement is:

An expression statement evaluates the expression list (which may be a single expression).

In interactive mode, if the value is not None , it is converted to a string using the built-in repr() function and the resulting string is written to standard output on a line by itself (except if the result is None , so that procedure calls do not cause any output.)

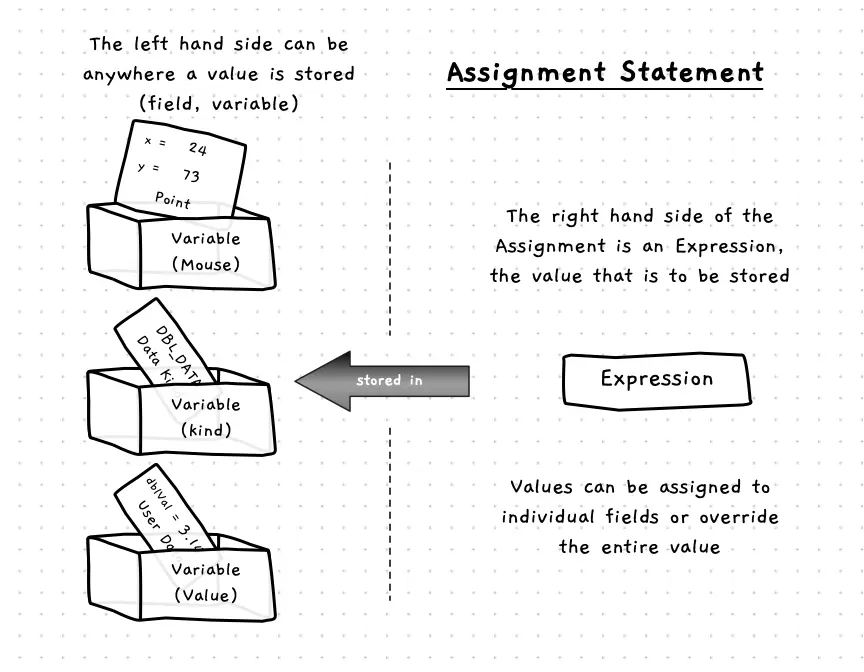

7.2. Assignment statements ¶

Assignment statements are used to (re)bind names to values and to modify attributes or items of mutable objects:

(See section Primaries for the syntax definitions for attributeref , subscription , and slicing .)

An assignment statement evaluates the expression list (remember that this can be a single expression or a comma-separated list, the latter yielding a tuple) and assigns the single resulting object to each of the target lists, from left to right.

Assignment is defined recursively depending on the form of the target (list). When a target is part of a mutable object (an attribute reference, subscription or slicing), the mutable object must ultimately perform the assignment and decide about its validity, and may raise an exception if the assignment is unacceptable. The rules observed by various types and the exceptions raised are given with the definition of the object types (see section The standard type hierarchy ).

Assignment of an object to a target list, optionally enclosed in parentheses or square brackets, is recursively defined as follows.

If the target list is a single target with no trailing comma, optionally in parentheses, the object is assigned to that target.

If the target list contains one target prefixed with an asterisk, called a “starred” target: The object must be an iterable with at least as many items as there are targets in the target list, minus one. The first items of the iterable are assigned, from left to right, to the targets before the starred target. The final items of the iterable are assigned to the targets after the starred target. A list of the remaining items in the iterable is then assigned to the starred target (the list can be empty).

Else: The object must be an iterable with the same number of items as there are targets in the target list, and the items are assigned, from left to right, to the corresponding targets.

Assignment of an object to a single target is recursively defined as follows.

If the target is an identifier (name):

If the name does not occur in a global or nonlocal statement in the current code block: the name is bound to the object in the current local namespace.

Otherwise: the name is bound to the object in the global namespace or the outer namespace determined by nonlocal , respectively.

The name is rebound if it was already bound. This may cause the reference count for the object previously bound to the name to reach zero, causing the object to be deallocated and its destructor (if it has one) to be called.

If the target is an attribute reference: The primary expression in the reference is evaluated. It should yield an object with assignable attributes; if this is not the case, TypeError is raised. That object is then asked to assign the assigned object to the given attribute; if it cannot perform the assignment, it raises an exception (usually but not necessarily AttributeError ).

Note: If the object is a class instance and the attribute reference occurs on both sides of the assignment operator, the right-hand side expression, a.x can access either an instance attribute or (if no instance attribute exists) a class attribute. The left-hand side target a.x is always set as an instance attribute, creating it if necessary. Thus, the two occurrences of a.x do not necessarily refer to the same attribute: if the right-hand side expression refers to a class attribute, the left-hand side creates a new instance attribute as the target of the assignment:

This description does not necessarily apply to descriptor attributes, such as properties created with property() .

If the target is a subscription: The primary expression in the reference is evaluated. It should yield either a mutable sequence object (such as a list) or a mapping object (such as a dictionary). Next, the subscript expression is evaluated.

If the primary is a mutable sequence object (such as a list), the subscript must yield an integer. If it is negative, the sequence’s length is added to it. The resulting value must be a nonnegative integer less than the sequence’s length, and the sequence is asked to assign the assigned object to its item with that index. If the index is out of range, IndexError is raised (assignment to a subscripted sequence cannot add new items to a list).

If the primary is a mapping object (such as a dictionary), the subscript must have a type compatible with the mapping’s key type, and the mapping is then asked to create a key/value pair which maps the subscript to the assigned object. This can either replace an existing key/value pair with the same key value, or insert a new key/value pair (if no key with the same value existed).

For user-defined objects, the __setitem__() method is called with appropriate arguments.

If the target is a slicing: The primary expression in the reference is evaluated. It should yield a mutable sequence object (such as a list). The assigned object should be a sequence object of the same type. Next, the lower and upper bound expressions are evaluated, insofar they are present; defaults are zero and the sequence’s length. The bounds should evaluate to integers. If either bound is negative, the sequence’s length is added to it. The resulting bounds are clipped to lie between zero and the sequence’s length, inclusive. Finally, the sequence object is asked to replace the slice with the items of the assigned sequence. The length of the slice may be different from the length of the assigned sequence, thus changing the length of the target sequence, if the target sequence allows it.

CPython implementation detail: In the current implementation, the syntax for targets is taken to be the same as for expressions, and invalid syntax is rejected during the code generation phase, causing less detailed error messages.

Although the definition of assignment implies that overlaps between the left-hand side and the right-hand side are ‘simultaneous’ (for example a, b = b, a swaps two variables), overlaps within the collection of assigned-to variables occur left-to-right, sometimes resulting in confusion. For instance, the following program prints [0, 2] :

The specification for the *target feature.

7.2.1. Augmented assignment statements ¶

Augmented assignment is the combination, in a single statement, of a binary operation and an assignment statement:

(See section Primaries for the syntax definitions of the last three symbols.)

An augmented assignment evaluates the target (which, unlike normal assignment statements, cannot be an unpacking) and the expression list, performs the binary operation specific to the type of assignment on the two operands, and assigns the result to the original target. The target is only evaluated once.

An augmented assignment expression like x += 1 can be rewritten as x = x + 1 to achieve a similar, but not exactly equal effect. In the augmented version, x is only evaluated once. Also, when possible, the actual operation is performed in-place , meaning that rather than creating a new object and assigning that to the target, the old object is modified instead.

Unlike normal assignments, augmented assignments evaluate the left-hand side before evaluating the right-hand side. For example, a[i] += f(x) first looks-up a[i] , then it evaluates f(x) and performs the addition, and lastly, it writes the result back to a[i] .

With the exception of assigning to tuples and multiple targets in a single statement, the assignment done by augmented assignment statements is handled the same way as normal assignments. Similarly, with the exception of the possible in-place behavior, the binary operation performed by augmented assignment is the same as the normal binary operations.

For targets which are attribute references, the same caveat about class and instance attributes applies as for regular assignments.

7.2.2. Annotated assignment statements ¶

Annotation assignment is the combination, in a single statement, of a variable or attribute annotation and an optional assignment statement:

The difference from normal Assignment statements is that only a single target is allowed.

For simple names as assignment targets, if in class or module scope, the annotations are evaluated and stored in a special class or module attribute __annotations__ that is a dictionary mapping from variable names (mangled if private) to evaluated annotations. This attribute is writable and is automatically created at the start of class or module body execution, if annotations are found statically.

For expressions as assignment targets, the annotations are evaluated if in class or module scope, but not stored.

If a name is annotated in a function scope, then this name is local for that scope. Annotations are never evaluated and stored in function scopes.

If the right hand side is present, an annotated assignment performs the actual assignment before evaluating annotations (where applicable). If the right hand side is not present for an expression target, then the interpreter evaluates the target except for the last __setitem__() or __setattr__() call.

The proposal that added syntax for annotating the types of variables (including class variables and instance variables), instead of expressing them through comments.

The proposal that added the typing module to provide a standard syntax for type annotations that can be used in static analysis tools and IDEs.

Changed in version 3.8: Now annotated assignments allow the same expressions in the right hand side as regular assignments. Previously, some expressions (like un-parenthesized tuple expressions) caused a syntax error.

7.3. The assert statement ¶

Assert statements are a convenient way to insert debugging assertions into a program:

The simple form, assert expression , is equivalent to

The extended form, assert expression1, expression2 , is equivalent to

These equivalences assume that __debug__ and AssertionError refer to the built-in variables with those names. In the current implementation, the built-in variable __debug__ is True under normal circumstances, False when optimization is requested (command line option -O ). The current code generator emits no code for an assert statement when optimization is requested at compile time. Note that it is unnecessary to include the source code for the expression that failed in the error message; it will be displayed as part of the stack trace.

Assignments to __debug__ are illegal. The value for the built-in variable is determined when the interpreter starts.

7.4. The pass statement ¶

pass is a null operation — when it is executed, nothing happens. It is useful as a placeholder when a statement is required syntactically, but no code needs to be executed, for example:

7.5. The del statement ¶

Deletion is recursively defined very similar to the way assignment is defined. Rather than spelling it out in full details, here are some hints.

Deletion of a target list recursively deletes each target, from left to right.

Deletion of a name removes the binding of that name from the local or global namespace, depending on whether the name occurs in a global statement in the same code block. If the name is unbound, a NameError exception will be raised.

Deletion of attribute references, subscriptions and slicings is passed to the primary object involved; deletion of a slicing is in general equivalent to assignment of an empty slice of the right type (but even this is determined by the sliced object).

Changed in version 3.2: Previously it was illegal to delete a name from the local namespace if it occurs as a free variable in a nested block.

7.6. The return statement ¶

return may only occur syntactically nested in a function definition, not within a nested class definition.

If an expression list is present, it is evaluated, else None is substituted.

return leaves the current function call with the expression list (or None ) as return value.

When return passes control out of a try statement with a finally clause, that finally clause is executed before really leaving the function.

In a generator function, the return statement indicates that the generator is done and will cause StopIteration to be raised. The returned value (if any) is used as an argument to construct StopIteration and becomes the StopIteration.value attribute.

In an asynchronous generator function, an empty return statement indicates that the asynchronous generator is done and will cause StopAsyncIteration to be raised. A non-empty return statement is a syntax error in an asynchronous generator function.

7.7. The yield statement ¶

A yield statement is semantically equivalent to a yield expression . The yield statement can be used to omit the parentheses that would otherwise be required in the equivalent yield expression statement. For example, the yield statements

are equivalent to the yield expression statements

Yield expressions and statements are only used when defining a generator function, and are only used in the body of the generator function. Using yield in a function definition is sufficient to cause that definition to create a generator function instead of a normal function.

For full details of yield semantics, refer to the Yield expressions section.

7.8. The raise statement ¶

If no expressions are present, raise re-raises the exception that is currently being handled, which is also known as the active exception . If there isn’t currently an active exception, a RuntimeError exception is raised indicating that this is an error.

Otherwise, raise evaluates the first expression as the exception object. It must be either a subclass or an instance of BaseException . If it is a class, the exception instance will be obtained when needed by instantiating the class with no arguments.

The type of the exception is the exception instance’s class, the value is the instance itself.

A traceback object is normally created automatically when an exception is raised and attached to it as the __traceback__ attribute. You can create an exception and set your own traceback in one step using the with_traceback() exception method (which returns the same exception instance, with its traceback set to its argument), like so:

The from clause is used for exception chaining: if given, the second expression must be another exception class or instance. If the second expression is an exception instance, it will be attached to the raised exception as the __cause__ attribute (which is writable). If the expression is an exception class, the class will be instantiated and the resulting exception instance will be attached to the raised exception as the __cause__ attribute. If the raised exception is not handled, both exceptions will be printed:

A similar mechanism works implicitly if a new exception is raised when an exception is already being handled. An exception may be handled when an except or finally clause, or a with statement, is used. The previous exception is then attached as the new exception’s __context__ attribute:

Exception chaining can be explicitly suppressed by specifying None in the from clause:

Additional information on exceptions can be found in section Exceptions , and information about handling exceptions is in section The try statement .

Changed in version 3.3: None is now permitted as Y in raise X from Y .

Added the __suppress_context__ attribute to suppress automatic display of the exception context.

Changed in version 3.11: If the traceback of the active exception is modified in an except clause, a subsequent raise statement re-raises the exception with the modified traceback. Previously, the exception was re-raised with the traceback it had when it was caught.

7.9. The break statement ¶

break may only occur syntactically nested in a for or while loop, but not nested in a function or class definition within that loop.

It terminates the nearest enclosing loop, skipping the optional else clause if the loop has one.

If a for loop is terminated by break , the loop control target keeps its current value.

When break passes control out of a try statement with a finally clause, that finally clause is executed before really leaving the loop.

7.10. The continue statement ¶

continue may only occur syntactically nested in a for or while loop, but not nested in a function or class definition within that loop. It continues with the next cycle of the nearest enclosing loop.

When continue passes control out of a try statement with a finally clause, that finally clause is executed before really starting the next loop cycle.

7.11. The import statement ¶

The basic import statement (no from clause) is executed in two steps:

find a module, loading and initializing it if necessary

define a name or names in the local namespace for the scope where the import statement occurs.

When the statement contains multiple clauses (separated by commas) the two steps are carried out separately for each clause, just as though the clauses had been separated out into individual import statements.

The details of the first step, finding and loading modules, are described in greater detail in the section on the import system , which also describes the various types of packages and modules that can be imported, as well as all the hooks that can be used to customize the import system. Note that failures in this step may indicate either that the module could not be located, or that an error occurred while initializing the module, which includes execution of the module’s code.

If the requested module is retrieved successfully, it will be made available in the local namespace in one of three ways:

If the module name is followed by as , then the name following as is bound directly to the imported module.

If no other name is specified, and the module being imported is a top level module, the module’s name is bound in the local namespace as a reference to the imported module

If the module being imported is not a top level module, then the name of the top level package that contains the module is bound in the local namespace as a reference to the top level package. The imported module must be accessed using its full qualified name rather than directly

The from form uses a slightly more complex process:

find the module specified in the from clause, loading and initializing it if necessary;

for each of the identifiers specified in the import clauses:

check if the imported module has an attribute by that name

if not, attempt to import a submodule with that name and then check the imported module again for that attribute

if the attribute is not found, ImportError is raised.

otherwise, a reference to that value is stored in the local namespace, using the name in the as clause if it is present, otherwise using the attribute name

If the list of identifiers is replaced by a star ( '*' ), all public names defined in the module are bound in the local namespace for the scope where the import statement occurs.

The public names defined by a module are determined by checking the module’s namespace for a variable named __all__ ; if defined, it must be a sequence of strings which are names defined or imported by that module. The names given in __all__ are all considered public and are required to exist. If __all__ is not defined, the set of public names includes all names found in the module’s namespace which do not begin with an underscore character ( '_' ). __all__ should contain the entire public API. It is intended to avoid accidentally exporting items that are not part of the API (such as library modules which were imported and used within the module).

The wild card form of import — from module import * — is only allowed at the module level. Attempting to use it in class or function definitions will raise a SyntaxError .

When specifying what module to import you do not have to specify the absolute name of the module. When a module or package is contained within another package it is possible to make a relative import within the same top package without having to mention the package name. By using leading dots in the specified module or package after from you can specify how high to traverse up the current package hierarchy without specifying exact names. One leading dot means the current package where the module making the import exists. Two dots means up one package level. Three dots is up two levels, etc. So if you execute from . import mod from a module in the pkg package then you will end up importing pkg.mod . If you execute from ..subpkg2 import mod from within pkg.subpkg1 you will import pkg.subpkg2.mod . The specification for relative imports is contained in the Package Relative Imports section.

importlib.import_module() is provided to support applications that determine dynamically the modules to be loaded.

Raises an auditing event import with arguments module , filename , sys.path , sys.meta_path , sys.path_hooks .

7.11.1. Future statements ¶

A future statement is a directive to the compiler that a particular module should be compiled using syntax or semantics that will be available in a specified future release of Python where the feature becomes standard.

The future statement is intended to ease migration to future versions of Python that introduce incompatible changes to the language. It allows use of the new features on a per-module basis before the release in which the feature becomes standard.

A future statement must appear near the top of the module. The only lines that can appear before a future statement are:

the module docstring (if any),

blank lines, and

other future statements.

The only feature that requires using the future statement is annotations (see PEP 563 ).

All historical features enabled by the future statement are still recognized by Python 3. The list includes absolute_import , division , generators , generator_stop , unicode_literals , print_function , nested_scopes and with_statement . They are all redundant because they are always enabled, and only kept for backwards compatibility.

A future statement is recognized and treated specially at compile time: Changes to the semantics of core constructs are often implemented by generating different code. It may even be the case that a new feature introduces new incompatible syntax (such as a new reserved word), in which case the compiler may need to parse the module differently. Such decisions cannot be pushed off until runtime.

For any given release, the compiler knows which feature names have been defined, and raises a compile-time error if a future statement contains a feature not known to it.

The direct runtime semantics are the same as for any import statement: there is a standard module __future__ , described later, and it will be imported in the usual way at the time the future statement is executed.

The interesting runtime semantics depend on the specific feature enabled by the future statement.

Note that there is nothing special about the statement:

That is not a future statement; it’s an ordinary import statement with no special semantics or syntax restrictions.

Code compiled by calls to the built-in functions exec() and compile() that occur in a module M containing a future statement will, by default, use the new syntax or semantics associated with the future statement. This can be controlled by optional arguments to compile() — see the documentation of that function for details.

A future statement typed at an interactive interpreter prompt will take effect for the rest of the interpreter session. If an interpreter is started with the -i option, is passed a script name to execute, and the script includes a future statement, it will be in effect in the interactive session started after the script is executed.

The original proposal for the __future__ mechanism.

7.12. The global statement ¶

The global statement is a declaration which holds for the entire current code block. It means that the listed identifiers are to be interpreted as globals. It would be impossible to assign to a global variable without global , although free variables may refer to globals without being declared global.

Names listed in a global statement must not be used in the same code block textually preceding that global statement.

Names listed in a global statement must not be defined as formal parameters, or as targets in with statements or except clauses, or in a for target list, class definition, function definition, import statement, or variable annotation.

CPython implementation detail: The current implementation does not enforce some of these restrictions, but programs should not abuse this freedom, as future implementations may enforce them or silently change the meaning of the program.

Programmer’s note: global is a directive to the parser. It applies only to code parsed at the same time as the global statement. In particular, a global statement contained in a string or code object supplied to the built-in exec() function does not affect the code block containing the function call, and code contained in such a string is unaffected by global statements in the code containing the function call. The same applies to the eval() and compile() functions.

7.13. The nonlocal statement ¶

When the definition of a function or class is nested (enclosed) within the definitions of other functions, its nonlocal scopes are the local scopes of the enclosing functions. The nonlocal statement causes the listed identifiers to refer to names previously bound in nonlocal scopes. It allows encapsulated code to rebind such nonlocal identifiers. If a name is bound in more than one nonlocal scope, the nearest binding is used. If a name is not bound in any nonlocal scope, or if there is no nonlocal scope, a SyntaxError is raised.

The nonlocal statement applies to the entire scope of a function or class body. A SyntaxError is raised if a variable is used or assigned to prior to its nonlocal declaration in the scope.

The specification for the nonlocal statement.

Programmer’s note: nonlocal is a directive to the parser and applies only to code parsed along with it. See the note for the global statement.

7.14. The type statement ¶

The type statement declares a type alias, which is an instance of typing.TypeAliasType .

For example, the following statement creates a type alias:

This code is roughly equivalent to:

annotation-def indicates an annotation scope , which behaves mostly like a function, but with several small differences.

The value of the type alias is evaluated in the annotation scope. It is not evaluated when the type alias is created, but only when the value is accessed through the type alias’s __value__ attribute (see Lazy evaluation ). This allows the type alias to refer to names that are not yet defined.

Type aliases may be made generic by adding a type parameter list after the name. See Generic type aliases for more.

type is a soft keyword .

Added in version 3.12.

Introduced the type statement and syntax for generic classes and functions.

Table of Contents

- 7.1. Expression statements

- 7.2.1. Augmented assignment statements

- 7.2.2. Annotated assignment statements

- 7.3. The assert statement

- 7.4. The pass statement

- 7.5. The del statement

- 7.6. The return statement

- 7.7. The yield statement

- 7.8. The raise statement

- 7.9. The break statement

- 7.10. The continue statement

- 7.11.1. Future statements

- 7.12. The global statement

- 7.13. The nonlocal statement

- 7.14. The type statement

Previous topic

6. Expressions

8. Compound statements

- Report a Bug

- Show Source

Python Enhancement Proposals

- Python »

- PEP Index »

PEP 572 – Assignment Expressions

The importance of real code, exceptional cases, scope of the target, relative precedence of :=, change to evaluation order, differences between assignment expressions and assignment statements, specification changes during implementation, _pydecimal.py, datetime.py, sysconfig.py, simplifying list comprehensions, capturing condition values, changing the scope rules for comprehensions, alternative spellings, special-casing conditional statements, special-casing comprehensions, lowering operator precedence, allowing commas to the right, always requiring parentheses, why not just turn existing assignment into an expression, with assignment expressions, why bother with assignment statements, why not use a sublocal scope and prevent namespace pollution, style guide recommendations, acknowledgements, a numeric example, appendix b: rough code translations for comprehensions, appendix c: no changes to scope semantics.

This is a proposal for creating a way to assign to variables within an expression using the notation NAME := expr .

As part of this change, there is also an update to dictionary comprehension evaluation order to ensure key expressions are executed before value expressions (allowing the key to be bound to a name and then re-used as part of calculating the corresponding value).

During discussion of this PEP, the operator became informally known as “the walrus operator”. The construct’s formal name is “Assignment Expressions” (as per the PEP title), but they may also be referred to as “Named Expressions” (e.g. the CPython reference implementation uses that name internally).

Naming the result of an expression is an important part of programming, allowing a descriptive name to be used in place of a longer expression, and permitting reuse. Currently, this feature is available only in statement form, making it unavailable in list comprehensions and other expression contexts.

Additionally, naming sub-parts of a large expression can assist an interactive debugger, providing useful display hooks and partial results. Without a way to capture sub-expressions inline, this would require refactoring of the original code; with assignment expressions, this merely requires the insertion of a few name := markers. Removing the need to refactor reduces the likelihood that the code be inadvertently changed as part of debugging (a common cause of Heisenbugs), and is easier to dictate to another programmer.

During the development of this PEP many people (supporters and critics both) have had a tendency to focus on toy examples on the one hand, and on overly complex examples on the other.

The danger of toy examples is twofold: they are often too abstract to make anyone go “ooh, that’s compelling”, and they are easily refuted with “I would never write it that way anyway”.

The danger of overly complex examples is that they provide a convenient strawman for critics of the proposal to shoot down (“that’s obfuscated”).

Yet there is some use for both extremely simple and extremely complex examples: they are helpful to clarify the intended semantics. Therefore, there will be some of each below.

However, in order to be compelling , examples should be rooted in real code, i.e. code that was written without any thought of this PEP, as part of a useful application, however large or small. Tim Peters has been extremely helpful by going over his own personal code repository and picking examples of code he had written that (in his view) would have been clearer if rewritten with (sparing) use of assignment expressions. His conclusion: the current proposal would have allowed a modest but clear improvement in quite a few bits of code.

Another use of real code is to observe indirectly how much value programmers place on compactness. Guido van Rossum searched through a Dropbox code base and discovered some evidence that programmers value writing fewer lines over shorter lines.

Case in point: Guido found several examples where a programmer repeated a subexpression, slowing down the program, in order to save one line of code, e.g. instead of writing:

they would write:

Another example illustrates that programmers sometimes do more work to save an extra level of indentation:

This code tries to match pattern2 even if pattern1 has a match (in which case the match on pattern2 is never used). The more efficient rewrite would have been:

Syntax and semantics

In most contexts where arbitrary Python expressions can be used, a named expression can appear. This is of the form NAME := expr where expr is any valid Python expression other than an unparenthesized tuple, and NAME is an identifier.

The value of such a named expression is the same as the incorporated expression, with the additional side-effect that the target is assigned that value:

There are a few places where assignment expressions are not allowed, in order to avoid ambiguities or user confusion:

This rule is included to simplify the choice for the user between an assignment statement and an assignment expression – there is no syntactic position where both are valid.

Again, this rule is included to avoid two visually similar ways of saying the same thing.

This rule is included to disallow excessively confusing code, and because parsing keyword arguments is complex enough already.

This rule is included to discourage side effects in a position whose exact semantics are already confusing to many users (cf. the common style recommendation against mutable default values), and also to echo the similar prohibition in calls (the previous bullet).

The reasoning here is similar to the two previous cases; this ungrouped assortment of symbols and operators composed of : and = is hard to read correctly.

This allows lambda to always bind less tightly than := ; having a name binding at the top level inside a lambda function is unlikely to be of value, as there is no way to make use of it. In cases where the name will be used more than once, the expression is likely to need parenthesizing anyway, so this prohibition will rarely affect code.

This shows that what looks like an assignment operator in an f-string is not always an assignment operator. The f-string parser uses : to indicate formatting options. To preserve backwards compatibility, assignment operator usage inside of f-strings must be parenthesized. As noted above, this usage of the assignment operator is not recommended.

An assignment expression does not introduce a new scope. In most cases the scope in which the target will be bound is self-explanatory: it is the current scope. If this scope contains a nonlocal or global declaration for the target, the assignment expression honors that. A lambda (being an explicit, if anonymous, function definition) counts as a scope for this purpose.

There is one special case: an assignment expression occurring in a list, set or dict comprehension or in a generator expression (below collectively referred to as “comprehensions”) binds the target in the containing scope, honoring a nonlocal or global declaration for the target in that scope, if one exists. For the purpose of this rule the containing scope of a nested comprehension is the scope that contains the outermost comprehension. A lambda counts as a containing scope.

The motivation for this special case is twofold. First, it allows us to conveniently capture a “witness” for an any() expression, or a counterexample for all() , for example:

Second, it allows a compact way of updating mutable state from a comprehension, for example:

However, an assignment expression target name cannot be the same as a for -target name appearing in any comprehension containing the assignment expression. The latter names are local to the comprehension in which they appear, so it would be contradictory for a contained use of the same name to refer to the scope containing the outermost comprehension instead.

For example, [i := i+1 for i in range(5)] is invalid: the for i part establishes that i is local to the comprehension, but the i := part insists that i is not local to the comprehension. The same reason makes these examples invalid too:

While it’s technically possible to assign consistent semantics to these cases, it’s difficult to determine whether those semantics actually make sense in the absence of real use cases. Accordingly, the reference implementation [1] will ensure that such cases raise SyntaxError , rather than executing with implementation defined behaviour.

This restriction applies even if the assignment expression is never executed:

For the comprehension body (the part before the first “for” keyword) and the filter expression (the part after “if” and before any nested “for”), this restriction applies solely to target names that are also used as iteration variables in the comprehension. Lambda expressions appearing in these positions introduce a new explicit function scope, and hence may use assignment expressions with no additional restrictions.

Due to design constraints in the reference implementation (the symbol table analyser cannot easily detect when names are re-used between the leftmost comprehension iterable expression and the rest of the comprehension), named expressions are disallowed entirely as part of comprehension iterable expressions (the part after each “in”, and before any subsequent “if” or “for” keyword):

A further exception applies when an assignment expression occurs in a comprehension whose containing scope is a class scope. If the rules above were to result in the target being assigned in that class’s scope, the assignment expression is expressly invalid. This case also raises SyntaxError :

(The reason for the latter exception is the implicit function scope created for comprehensions – there is currently no runtime mechanism for a function to refer to a variable in the containing class scope, and we do not want to add such a mechanism. If this issue ever gets resolved this special case may be removed from the specification of assignment expressions. Note that the problem already exists for using a variable defined in the class scope from a comprehension.)

See Appendix B for some examples of how the rules for targets in comprehensions translate to equivalent code.

The := operator groups more tightly than a comma in all syntactic positions where it is legal, but less tightly than all other operators, including or , and , not , and conditional expressions ( A if C else B ). As follows from section “Exceptional cases” above, it is never allowed at the same level as = . In case a different grouping is desired, parentheses should be used.

The := operator may be used directly in a positional function call argument; however it is invalid directly in a keyword argument.

Some examples to clarify what’s technically valid or invalid:

Most of the “valid” examples above are not recommended, since human readers of Python source code who are quickly glancing at some code may miss the distinction. But simple cases are not objectionable:

This PEP recommends always putting spaces around := , similar to PEP 8 ’s recommendation for = when used for assignment, whereas the latter disallows spaces around = used for keyword arguments.)

In order to have precisely defined semantics, the proposal requires evaluation order to be well-defined. This is technically not a new requirement, as function calls may already have side effects. Python already has a rule that subexpressions are generally evaluated from left to right. However, assignment expressions make these side effects more visible, and we propose a single change to the current evaluation order:

- In a dict comprehension {X: Y for ...} , Y is currently evaluated before X . We propose to change this so that X is evaluated before Y . (In a dict display like {X: Y} this is already the case, and also in dict((X, Y) for ...) which should clearly be equivalent to the dict comprehension.)

Most importantly, since := is an expression, it can be used in contexts where statements are illegal, including lambda functions and comprehensions.

Conversely, assignment expressions don’t support the advanced features found in assignment statements:

- Multiple targets are not directly supported: x = y = z = 0 # Equivalent: (z := (y := (x := 0)))

- Single assignment targets other than a single NAME are not supported: # No equivalent a [ i ] = x self . rest = []

- Priority around commas is different: x = 1 , 2 # Sets x to (1, 2) ( x := 1 , 2 ) # Sets x to 1

- Iterable packing and unpacking (both regular or extended forms) are not supported: # Equivalent needs extra parentheses loc = x , y # Use (loc := (x, y)) info = name , phone , * rest # Use (info := (name, phone, *rest)) # No equivalent px , py , pz = position name , phone , email , * other_info = contact

- Inline type annotations are not supported: # Closest equivalent is "p: Optional[int]" as a separate declaration p : Optional [ int ] = None

- Augmented assignment is not supported: total += tax # Equivalent: (total := total + tax)

The following changes have been made based on implementation experience and additional review after the PEP was first accepted and before Python 3.8 was released:

- for consistency with other similar exceptions, and to avoid locking in an exception name that is not necessarily going to improve clarity for end users, the originally proposed TargetScopeError subclass of SyntaxError was dropped in favour of just raising SyntaxError directly. [3]

- due to a limitation in CPython’s symbol table analysis process, the reference implementation raises SyntaxError for all uses of named expressions inside comprehension iterable expressions, rather than only raising them when the named expression target conflicts with one of the iteration variables in the comprehension. This could be revisited given sufficiently compelling examples, but the extra complexity needed to implement the more selective restriction doesn’t seem worthwhile for purely hypothetical use cases.

Examples from the Python standard library

env_base is only used on these lines, putting its assignment on the if moves it as the “header” of the block.

- Current: env_base = os . environ . get ( "PYTHONUSERBASE" , None ) if env_base : return env_base

- Improved: if env_base := os . environ . get ( "PYTHONUSERBASE" , None ): return env_base

Avoid nested if and remove one indentation level.

- Current: if self . _is_special : ans = self . _check_nans ( context = context ) if ans : return ans

- Improved: if self . _is_special and ( ans := self . _check_nans ( context = context )): return ans

Code looks more regular and avoid multiple nested if. (See Appendix A for the origin of this example.)

- Current: reductor = dispatch_table . get ( cls ) if reductor : rv = reductor ( x ) else : reductor = getattr ( x , "__reduce_ex__" , None ) if reductor : rv = reductor ( 4 ) else : reductor = getattr ( x , "__reduce__" , None ) if reductor : rv = reductor () else : raise Error ( "un(deep)copyable object of type %s " % cls )

- Improved: if reductor := dispatch_table . get ( cls ): rv = reductor ( x ) elif reductor := getattr ( x , "__reduce_ex__" , None ): rv = reductor ( 4 ) elif reductor := getattr ( x , "__reduce__" , None ): rv = reductor () else : raise Error ( "un(deep)copyable object of type %s " % cls )

tz is only used for s += tz , moving its assignment inside the if helps to show its scope.

- Current: s = _format_time ( self . _hour , self . _minute , self . _second , self . _microsecond , timespec ) tz = self . _tzstr () if tz : s += tz return s

- Improved: s = _format_time ( self . _hour , self . _minute , self . _second , self . _microsecond , timespec ) if tz := self . _tzstr (): s += tz return s

Calling fp.readline() in the while condition and calling .match() on the if lines make the code more compact without making it harder to understand.

- Current: while True : line = fp . readline () if not line : break m = define_rx . match ( line ) if m : n , v = m . group ( 1 , 2 ) try : v = int ( v ) except ValueError : pass vars [ n ] = v else : m = undef_rx . match ( line ) if m : vars [ m . group ( 1 )] = 0

- Improved: while line := fp . readline (): if m := define_rx . match ( line ): n , v = m . group ( 1 , 2 ) try : v = int ( v ) except ValueError : pass vars [ n ] = v elif m := undef_rx . match ( line ): vars [ m . group ( 1 )] = 0

A list comprehension can map and filter efficiently by capturing the condition:

Similarly, a subexpression can be reused within the main expression, by giving it a name on first use:

Note that in both cases the variable y is bound in the containing scope (i.e. at the same level as results or stuff ).

Assignment expressions can be used to good effect in the header of an if or while statement:

Particularly with the while loop, this can remove the need to have an infinite loop, an assignment, and a condition. It also creates a smooth parallel between a loop which simply uses a function call as its condition, and one which uses that as its condition but also uses the actual value.

An example from the low-level UNIX world:

Rejected alternative proposals

Proposals broadly similar to this one have come up frequently on python-ideas. Below are a number of alternative syntaxes, some of them specific to comprehensions, which have been rejected in favour of the one given above.

A previous version of this PEP proposed subtle changes to the scope rules for comprehensions, to make them more usable in class scope and to unify the scope of the “outermost iterable” and the rest of the comprehension. However, this part of the proposal would have caused backwards incompatibilities, and has been withdrawn so the PEP can focus on assignment expressions.

Broadly the same semantics as the current proposal, but spelled differently.

Since EXPR as NAME already has meaning in import , except and with statements (with different semantics), this would create unnecessary confusion or require special-casing (e.g. to forbid assignment within the headers of these statements).

(Note that with EXPR as VAR does not simply assign the value of EXPR to VAR – it calls EXPR.__enter__() and assigns the result of that to VAR .)

Additional reasons to prefer := over this spelling include:

- In if f(x) as y the assignment target doesn’t jump out at you – it just reads like if f x blah blah and it is too similar visually to if f(x) and y .

- import foo as bar

- except Exc as var

- with ctxmgr() as var

To the contrary, the assignment expression does not belong to the if or while that starts the line, and we intentionally allow assignment expressions in other contexts as well.

- NAME = EXPR

- if NAME := EXPR

reinforces the visual recognition of assignment expressions.

This syntax is inspired by languages such as R and Haskell, and some programmable calculators. (Note that a left-facing arrow y <- f(x) is not possible in Python, as it would be interpreted as less-than and unary minus.) This syntax has a slight advantage over ‘as’ in that it does not conflict with with , except and import , but otherwise is equivalent. But it is entirely unrelated to Python’s other use of -> (function return type annotations), and compared to := (which dates back to Algol-58) it has a much weaker tradition.

This has the advantage that leaked usage can be readily detected, removing some forms of syntactic ambiguity. However, this would be the only place in Python where a variable’s scope is encoded into its name, making refactoring harder.

Execution order is inverted (the indented body is performed first, followed by the “header”). This requires a new keyword, unless an existing keyword is repurposed (most likely with: ). See PEP 3150 for prior discussion on this subject (with the proposed keyword being given: ).

This syntax has fewer conflicts than as does (conflicting only with the raise Exc from Exc notation), but is otherwise comparable to it. Instead of paralleling with expr as target: (which can be useful but can also be confusing), this has no parallels, but is evocative.

One of the most popular use-cases is if and while statements. Instead of a more general solution, this proposal enhances the syntax of these two statements to add a means of capturing the compared value:

This works beautifully if and ONLY if the desired condition is based on the truthiness of the captured value. It is thus effective for specific use-cases (regex matches, socket reads that return '' when done), and completely useless in more complicated cases (e.g. where the condition is f(x) < 0 and you want to capture the value of f(x) ). It also has no benefit to list comprehensions.

Advantages: No syntactic ambiguities. Disadvantages: Answers only a fraction of possible use-cases, even in if / while statements.

Another common use-case is comprehensions (list/set/dict, and genexps). As above, proposals have been made for comprehension-specific solutions.

This brings the subexpression to a location in between the ‘for’ loop and the expression. It introduces an additional language keyword, which creates conflicts. Of the three, where reads the most cleanly, but also has the greatest potential for conflict (e.g. SQLAlchemy and numpy have where methods, as does tkinter.dnd.Icon in the standard library).

As above, but reusing the with keyword. Doesn’t read too badly, and needs no additional language keyword. Is restricted to comprehensions, though, and cannot as easily be transformed into “longhand” for-loop syntax. Has the C problem that an equals sign in an expression can now create a name binding, rather than performing a comparison. Would raise the question of why “with NAME = EXPR:” cannot be used as a statement on its own.

As per option 2, but using as rather than an equals sign. Aligns syntactically with other uses of as for name binding, but a simple transformation to for-loop longhand would create drastically different semantics; the meaning of with inside a comprehension would be completely different from the meaning as a stand-alone statement, while retaining identical syntax.

Regardless of the spelling chosen, this introduces a stark difference between comprehensions and the equivalent unrolled long-hand form of the loop. It is no longer possible to unwrap the loop into statement form without reworking any name bindings. The only keyword that can be repurposed to this task is with , thus giving it sneakily different semantics in a comprehension than in a statement; alternatively, a new keyword is needed, with all the costs therein.

There are two logical precedences for the := operator. Either it should bind as loosely as possible, as does statement-assignment; or it should bind more tightly than comparison operators. Placing its precedence between the comparison and arithmetic operators (to be precise: just lower than bitwise OR) allows most uses inside while and if conditions to be spelled without parentheses, as it is most likely that you wish to capture the value of something, then perform a comparison on it:

Once find() returns -1, the loop terminates. If := binds as loosely as = does, this would capture the result of the comparison (generally either True or False ), which is less useful.

While this behaviour would be convenient in many situations, it is also harder to explain than “the := operator behaves just like the assignment statement”, and as such, the precedence for := has been made as close as possible to that of = (with the exception that it binds tighter than comma).

Some critics have claimed that the assignment expressions should allow unparenthesized tuples on the right, so that these two would be equivalent:

(With the current version of the proposal, the latter would be equivalent to ((point := x), y) .)

However, adopting this stance would logically lead to the conclusion that when used in a function call, assignment expressions also bind less tight than comma, so we’d have the following confusing equivalence:

The less confusing option is to make := bind more tightly than comma.

It’s been proposed to just always require parentheses around an assignment expression. This would resolve many ambiguities, and indeed parentheses will frequently be needed to extract the desired subexpression. But in the following cases the extra parentheses feel redundant:

Frequently Raised Objections

C and its derivatives define the = operator as an expression, rather than a statement as is Python’s way. This allows assignments in more contexts, including contexts where comparisons are more common. The syntactic similarity between if (x == y) and if (x = y) belies their drastically different semantics. Thus this proposal uses := to clarify the distinction.

The two forms have different flexibilities. The := operator can be used inside a larger expression; the = statement can be augmented to += and its friends, can be chained, and can assign to attributes and subscripts.

Previous revisions of this proposal involved sublocal scope (restricted to a single statement), preventing name leakage and namespace pollution. While a definite advantage in a number of situations, this increases complexity in many others, and the costs are not justified by the benefits. In the interests of language simplicity, the name bindings created here are exactly equivalent to any other name bindings, including that usage at class or module scope will create externally-visible names. This is no different from for loops or other constructs, and can be solved the same way: del the name once it is no longer needed, or prefix it with an underscore.

(The author wishes to thank Guido van Rossum and Christoph Groth for their suggestions to move the proposal in this direction. [2] )

As expression assignments can sometimes be used equivalently to statement assignments, the question of which should be preferred will arise. For the benefit of style guides such as PEP 8 , two recommendations are suggested.

- If either assignment statements or assignment expressions can be used, prefer statements; they are a clear declaration of intent.

- If using assignment expressions would lead to ambiguity about execution order, restructure it to use statements instead.

The authors wish to thank Alyssa Coghlan and Steven D’Aprano for their considerable contributions to this proposal, and members of the core-mentorship mailing list for assistance with implementation.

Appendix A: Tim Peters’s findings

Here’s a brief essay Tim Peters wrote on the topic.

I dislike “busy” lines of code, and also dislike putting conceptually unrelated logic on a single line. So, for example, instead of:

instead. So I suspected I’d find few places I’d want to use assignment expressions. I didn’t even consider them for lines already stretching halfway across the screen. In other cases, “unrelated” ruled:

is a vast improvement over the briefer:

The original two statements are doing entirely different conceptual things, and slamming them together is conceptually insane.

In other cases, combining related logic made it harder to understand, such as rewriting:

as the briefer:

The while test there is too subtle, crucially relying on strict left-to-right evaluation in a non-short-circuiting or method-chaining context. My brain isn’t wired that way.

But cases like that were rare. Name binding is very frequent, and “sparse is better than dense” does not mean “almost empty is better than sparse”. For example, I have many functions that return None or 0 to communicate “I have nothing useful to return in this case, but since that’s expected often I’m not going to annoy you with an exception”. This is essentially the same as regular expression search functions returning None when there is no match. So there was lots of code of the form:

I find that clearer, and certainly a bit less typing and pattern-matching reading, as:

It’s also nice to trade away a small amount of horizontal whitespace to get another _line_ of surrounding code on screen. I didn’t give much weight to this at first, but it was so very frequent it added up, and I soon enough became annoyed that I couldn’t actually run the briefer code. That surprised me!

There are other cases where assignment expressions really shine. Rather than pick another from my code, Kirill Balunov gave a lovely example from the standard library’s copy() function in copy.py :

The ever-increasing indentation is semantically misleading: the logic is conceptually flat, “the first test that succeeds wins”:

Using easy assignment expressions allows the visual structure of the code to emphasize the conceptual flatness of the logic; ever-increasing indentation obscured it.

A smaller example from my code delighted me, both allowing to put inherently related logic in a single line, and allowing to remove an annoying “artificial” indentation level:

That if is about as long as I want my lines to get, but remains easy to follow.

So, in all, in most lines binding a name, I wouldn’t use assignment expressions, but because that construct is so very frequent, that leaves many places I would. In most of the latter, I found a small win that adds up due to how often it occurs, and in the rest I found a moderate to major win. I’d certainly use it more often than ternary if , but significantly less often than augmented assignment.

I have another example that quite impressed me at the time.

Where all variables are positive integers, and a is at least as large as the n’th root of x, this algorithm returns the floor of the n’th root of x (and roughly doubling the number of accurate bits per iteration):

It’s not obvious why that works, but is no more obvious in the “loop and a half” form. It’s hard to prove correctness without building on the right insight (the “arithmetic mean - geometric mean inequality”), and knowing some non-trivial things about how nested floor functions behave. That is, the challenges are in the math, not really in the coding.

If you do know all that, then the assignment-expression form is easily read as “while the current guess is too large, get a smaller guess”, where the “too large?” test and the new guess share an expensive sub-expression.

To my eyes, the original form is harder to understand:

This appendix attempts to clarify (though not specify) the rules when a target occurs in a comprehension or in a generator expression. For a number of illustrative examples we show the original code, containing a comprehension, and the translation, where the comprehension has been replaced by an equivalent generator function plus some scaffolding.

Since [x for ...] is equivalent to list(x for ...) these examples all use list comprehensions without loss of generality. And since these examples are meant to clarify edge cases of the rules, they aren’t trying to look like real code.

Note: comprehensions are already implemented via synthesizing nested generator functions like those in this appendix. The new part is adding appropriate declarations to establish the intended scope of assignment expression targets (the same scope they resolve to as if the assignment were performed in the block containing the outermost comprehension). For type inference purposes, these illustrative expansions do not imply that assignment expression targets are always Optional (but they do indicate the target binding scope).

Let’s start with a reminder of what code is generated for a generator expression without assignment expression.

- Original code (EXPR usually references VAR): def f (): a = [ EXPR for VAR in ITERABLE ]

- Translation (let’s not worry about name conflicts): def f (): def genexpr ( iterator ): for VAR in iterator : yield EXPR a = list ( genexpr ( iter ( ITERABLE )))

Let’s add a simple assignment expression.

- Original code: def f (): a = [ TARGET := EXPR for VAR in ITERABLE ]

- Translation: def f (): if False : TARGET = None # Dead code to ensure TARGET is a local variable def genexpr ( iterator ): nonlocal TARGET for VAR in iterator : TARGET = EXPR yield TARGET a = list ( genexpr ( iter ( ITERABLE )))

Let’s add a global TARGET declaration in f() .

- Original code: def f (): global TARGET a = [ TARGET := EXPR for VAR in ITERABLE ]

- Translation: def f (): global TARGET def genexpr ( iterator ): global TARGET for VAR in iterator : TARGET = EXPR yield TARGET a = list ( genexpr ( iter ( ITERABLE )))

Or instead let’s add a nonlocal TARGET declaration in f() .

- Original code: def g (): TARGET = ... def f (): nonlocal TARGET a = [ TARGET := EXPR for VAR in ITERABLE ]

- Translation: def g (): TARGET = ... def f (): nonlocal TARGET def genexpr ( iterator ): nonlocal TARGET for VAR in iterator : TARGET = EXPR yield TARGET a = list ( genexpr ( iter ( ITERABLE )))

Finally, let’s nest two comprehensions.

- Original code: def f (): a = [[ TARGET := i for i in range ( 3 )] for j in range ( 2 )] # I.e., a = [[0, 1, 2], [0, 1, 2]] print ( TARGET ) # prints 2

- Translation: def f (): if False : TARGET = None def outer_genexpr ( outer_iterator ): nonlocal TARGET def inner_generator ( inner_iterator ): nonlocal TARGET for i in inner_iterator : TARGET = i yield i for j in outer_iterator : yield list ( inner_generator ( range ( 3 ))) a = list ( outer_genexpr ( range ( 2 ))) print ( TARGET )

Because it has been a point of confusion, note that nothing about Python’s scoping semantics is changed. Function-local scopes continue to be resolved at compile time, and to have indefinite temporal extent at run time (“full closures”). Example:

This document has been placed in the public domain.

Source: https://github.com/python/peps/blob/main/peps/pep-0572.rst

Last modified: 2023-10-11 12:05:51 GMT

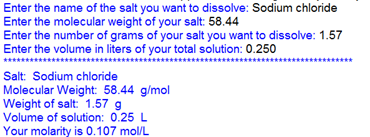

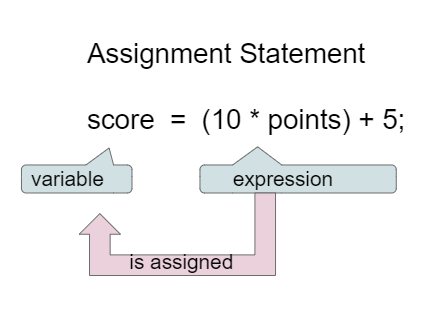

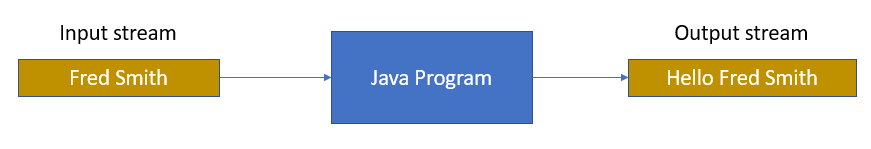

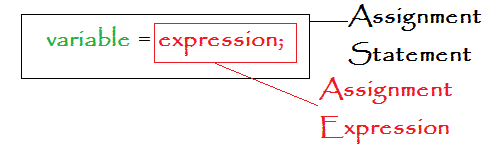

Assignment Statements

The last thing we discussed in the previous unit were variables. We use variables to store values of an evaluated expression. To store this value, we use an assignment statement . A simple assignment statement consists of a variable name, an equal sign ( assignment operator ) and the value to be stored.

a in the above expression is assigned the value 7.

Here we see that the variable a has 2 added to it's previous value. The resulting number is 9, the addition of 7 and 2.

To break it down into easy steps:

- a = 7 -> Variable is initialized when we store a value in it

- a = a + 2 -> Variable is assigned a new value and forgets the old value

This is called overwriting the variable. a 's value was overwritten in the process. The expression on the right of the = operator is evaluated down to a single value before it is assigned to the variable on the left. During the evaluation stage, a still carries the number 7 , this is added by 2 which results in 9 . 9 is then assigned to the variable a and overwrites the previous value.

Another example:

Hence, when a new value is assigned to a variable, the old one is forgotten.

Variable Names

There are three rules for variable names:

- It can be only one word, no spaces are allowed.

- It can use only letters, numbers, and the underscore (_) character.

- It can’t begin with a number.

Note: Variable names are case-sensitive. This means that hello, Hello, hellO are three different variables. The python convention is to start a variable name with lowercase characters. Tip: A good variable name describes the data it contains. Imagine you have a cat namely Kitty. You could say cat = 'Kitty' .

What would this output: 'name' + 'namename' ? a. 'name' b. 'namenamename' c. 'namename' d. namenamename

What would this output: 'name' * 3 a. 'name' b. 'namenamename' c. 'namename' d. namenamename

results matching " "

No results matching " ".

Learning Python by doing

- suggest edit

Variables, Expressions, and Assignments

Variables, expressions, and assignments 1 #, introduction #.

In this chapter, we introduce some of the main building blocks needed to create programs–that is, variables, expressions, and assignments. Programming related variables can be intepret in the same way that we interpret mathematical variables, as elements that store values that can later be changed. Usually, variables and values are used within the so-called expressions. Once again, just as in mathematics, an expression is a construct of values and variables connected with operators that result in a new value. Lastly, an assignment is a language construct know as an statement that assign a value (either as a constant or expression) to a variable. The rest of this notebook will dive into the main concepts that we need to fully understand these three language constructs.

Values and Types #

A value is the basic unit used in a program. It may be, for instance, a number respresenting temperature. It may be a string representing a word. Some values are 42, 42.0, and ‘Hello, Data Scientists!’.

Each value has its own type : 42 is an integer ( int in Python), 42.0 is a floating-point number ( float in Python), and ‘Hello, Data Scientists!’ is a string ( str in Python).

The Python interpreter can tell you the type of a value: the function type takes a value as argument and returns its corresponding type.

Observe the difference between type(42) and type('42') !

Expressions and Statements #

On the one hand, an expression is a combination of values, variables, and operators.

A value all by itself is considered an expression, and so is a variable.

When you type an expression at the prompt, the interpreter evaluates it, which means that it calculates the value of the expression and displays it.

In boxes above, m has the value 27 and m + 25 has the value 52 . m + 25 is said to be an expression.

On the other hand, a statement is an instruction that has an effect, like creating a variable or displaying a value.

The first statement initializes the variable n with the value 17 , this is a so-called assignment statement .

The second statement is a print statement that prints the value of the variable n .

The effect is not always visible. Assigning a value to a variable is not visible, but printing the value of a variable is.

Assignment Statements #

We have already seen that Python allows you to evaluate expressions, for instance 40 + 2 . It is very convenient if we are able to store the calculated value in some variable for future use. The latter can be done via an assignment statement. An assignment statement creates a new variable with a given name and assigns it a value.

The example in the previous code contains three assignments. The first one assigns the value of the expression 40 + 2 to a new variable called magicnumber ; the second one assigns the value of π to the variable pi , and; the last assignment assigns the string value 'Data is eatig the world' to the variable message .

Programmers generally choose names for their variables that are meaningful. In this way, they document what the variable is used for.

Do It Yourself!

Let’s compute the volume of a cube with side \(s = 5\) . Remember that the volume of a cube is defined as \(v = s^3\) . Assign the value to a variable called volume .

Well done! Now, why don’t you print the result in a message? It can say something like “The volume of the cube with side 5 is \(volume\) ”.

Beware that there is no checking of types ( type checking ) in Python, so a variable to which you have assigned an integer may be re-used as a float, even if we provide type-hints .

Names and Keywords #

Names of variable and other language constructs such as functions (we will cover this topic later), should be meaningful and reflect the purpose of the construct.

In general, Python names should adhere to the following rules:

It should start with a letter or underscore.

It cannot start with a number.

It must only contain alpha-numeric (i.e., letters a-z A-Z and digits 0-9) characters and underscores.

They cannot share the name of a Python keyword.

If you use illegal variable names you will get a syntax error.

By choosing the right variables names you make the code self-documenting, what is better the variable v or velocity ?

The following are examples of invalid variable names.

These basic development principles are sometimes called architectural rules . By defining and agreeing upon architectural rules you make it easier for you and your fellow developers to understand and modify your code.

If you want to read more on this, please have a look at Code complete a book by Steven McConnell [ McC04 ] .

Every programming language has a collection of reserved keywords . They are used in predefined language constructs, such as loops and conditionals . These language concepts and their usage will be explained later.

The interpreter uses keywords to recognize these language constructs in a program. Python 3 has the following keywords:

False class finally is return

None continue for lambda try

True def from nonlocal while

and del global not with

as elif if or yield

assert else import pass break

except in raise

Reassignments #

It is allowed to assign a new value to an existing variable. This process is called reassignment . As soon as you assign a value to a variable, the old value is lost.

The assignment of a variable to another variable, for instance b = a does not imply that if a is reassigned then b changes as well.

You have a variable salary that shows the weekly salary of an employee. However, you want to compute the monthly salary. Can you reassign the value to the salary variable according to the instruction?

Updating Variables #

A frequently used reassignment is for updating puposes: the value of a variable depends on the previous value of the variable.

This statement expresses “get the current value of x , add one, and then update x with the new value.”

Beware, that the variable should be initialized first, usually with a simple assignment.

Do you remember the salary excercise of the previous section (cf. 13. Reassignments)? Well, if you have not done it yet, update the salary variable by using its previous value.

Updating a variable by adding 1 is called an increment ; subtracting 1 is called a decrement . A shorthand way of doing is using += and -= , which stands for x = x + ... and x = x - ... respectively.

Order of Operations #

Expressions may contain multiple operators. The order of evaluation depends on the priorities of the operators also known as rules of precedence .

For mathematical operators, Python follows mathematical convention. The acronym PEMDAS is a useful way to remember the rules:

Parentheses have the highest precedence and can be used to force an expression to evaluate in the order you want. Since expressions in parentheses are evaluated first, 2 * (3 - 1) is 4 , and (1 + 1)**(5 - 2) is 8 . You can also use parentheses to make an expression easier to read, even if it does not change the result.

Exponentiation has the next highest precedence, so 1 + 2**3 is 9 , not 27 , and 2 * 3**2 is 18 , not 36 .

Multiplication and division have higher precedence than addition and subtraction . So 2 * 3 - 1 is 5 , not 4 , and 6 + 4 / 2 is 8 , not 5 .

Operators with the same precedence are evaluated from left to right (except exponentiation). So in the expression degrees / 2 * pi , the division happens first and the result is multiplied by pi . To divide by 2π, you can use parentheses or write: degrees / 2 / pi .

In case of doubt, use parentheses!

Let’s see what happens when we evaluate the following expressions. Just run the cell to check the resulting value.

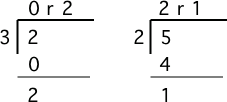

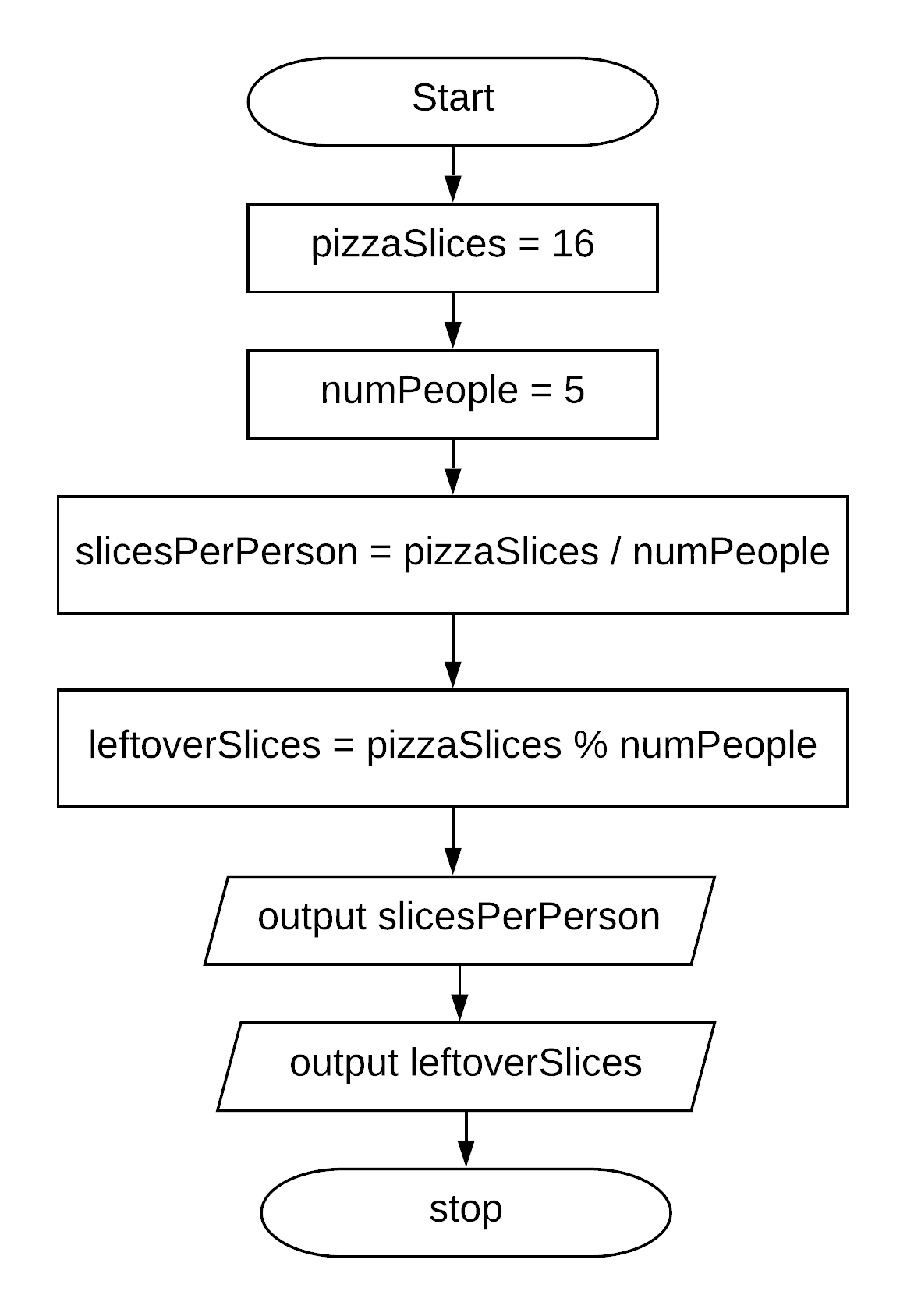

Floor Division and Modulus Operators #

The floor division operator // divides two numbers and rounds down to an integer.

For example, suppose that driving to the south of France takes 555 minutes. You might want to know how long that is in hours.

Conventional division returns a floating-point number.

Hours are normally not represented with decimal points. Floor division returns the integer number of hours, dropping the fraction part.

You spend around 225 minutes every week on programming activities. You want to know around how many hours you invest to this activity during a month. Use the \(//\) operator to give the answer.

The modulus operator % works on integer values. It computes the remainder when dividing the first integer by the second one.

The modulus operator is more useful than it seems.

For example, you can check whether one number is divisible by another—if x % y is zero, then x is divisible by y .

String Operations #

In general, you cannot perform mathematical operations on strings, even if the strings look like numbers, so the following operations are illegal: '2'-'1' 'eggs'/'easy' 'third'*'a charm'

But there are two exceptions, + and * .

The + operator performs string concatenation, which means it joins the strings by linking them end-to-end.

The * operator also works on strings; it performs repetition.

Speedy Gonzales is a cartoon known to be the fastest mouse in all Mexico . He is also famous for saying “Arriba Arriba Andale Arriba Arriba Yepa”. Can you use the following variables, namely arriba , andale and yepa to print the mentioned expression? Don’t forget to use the string operators.

Asking the User for Input #

The programs we have written so far accept no input from the user.