- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, social media influence on politicians' and citizens' relationship through the moderating effect of political slogans.

- School of Management and Economics, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China

The digitalization of communication means has revolutionized the way people observe and react to the social and political developments in their surroundings. The rapidly growing influence of social media prompted this exploratory research article on the use of social networking sites by politicians to build a cordial and strong relationship with the common citizens. This article focuses on investigating social media's influence on the relationship between politicians and citizens through the moderating effect of political slogans. Social media not only enables the politicians to directly communicate with the citizens but also encourages political participation of citizens in the form of feedback via comments on social networking sites. Political slogans play a significant role in the image building of a particular political force in the eyes of citizens. A quantitative analysis approach is utilized in this study. Data are collected via a survey questionnaire from a variety of social media users with a cross-sectional time horizon. In total, 300 people submitted their responses via the questionnaire, which was circulated in the first 2 months of this year (i.e., January and February 2022). The convenience sampling method was utilized for data collection across two cities in Pakistan. Smart PLS 3 has been used for hypothesis testing. The effect of the Moderator, i.e., political slogans of the basic four political parties of Pakistan are measured individually. Results show that the impact of social networking sites and politics on politicians' and citizens' relationships is positive and significant. This study can be a stepping stone for further related research to enable the politicians to make positive relationships with the citizens by effectively utilizing the social media platform.

Introduction

Social media (SM) is rapidly turning into a key commodity in establishing links with various individuals, cultures, and businesses. Golbeck et al. (2010 , p. 1613) portrayed social media as a platform that possesses the capabilities to facilitate interpersonal and group interaction. It also provides news and unique opportunities for community leaders, elected officials, and government service providers to inform and be informed by, the citizenry. Social media is at the forefront of the marketing strategies devised by many leading industries and businesses to connect with existing and future consumers. The collaboration of various social media platforms also plays a crucial role in identifying and resolving various complications related to marketing and advertising strategies ( Tsimonis and Dimitriadis, 2014 , p. 329–330).

Today's world has been converted into a “global village” thanks to the spectacular rise of social media. It means that everyone around the world can communicate with each other freely and with ease. Consumers and businesses both get a lot of benefits out of social media. Consumers generally rely on social media to accumulate all the related knowledge of products or services desired by them ( Song and Yoo, 2016 , p. 85–86). Organizations should adopt social media to promote their products as it is the most direct and easily accessible means of communication to influence public perception. It is widely seen as a tool to eloquently express opinions and beliefs.

Social media encompasses “highly interactive platforms” designed to share information, facilitate different types of discussion, and develop relationships with other users; the interactive platforms are created through different technologies ( Kietzmann et al., 2011 , p. 241). A framework is developed in the literature where social media is thoroughly explained with the help of seven building blocks. The seven building blocks are as follows: identity, conversations, presence, relationships, reputation, sharing, and groups. The brief descriptions of these building blocks are provided below:

• Identity: the personal information provided by the user.

• Conversations: communication between the users on social media.

• Sharing: the amount of content shared by the users.

• Presence: social media can give information about the users whether they are online or not.

• Relationships: the level of association between the users.

• Reputation: depicts how aware are the users of their status and that of others in a social media setting.

• Groups: a building block that describes the capability of users to form communities and sub-communities.

The reason for proposing this framework is to explain social media clearly but the organizations are not able to extract desirable results from utilizing social media as they are unaware of the range of services available on the social networking sites. A large number of social media users are provided with one-of-a-kind experiences related to the political subject matter. The randomly chosen posts shared by these users and highlighted by the algorithms working behind the scenes of such social networking sites play a critical role in information sharing ( Marwick and Boyd, 2011 , p. 142–143; Gillespie and Boczkowski, 2014 , 188; Vraga, 2016 , 601). Consequently, according to a similar study ( Bode, 2016 , p. 44), social media offers a better and more vibrant platform for such diverse political subject matter in comparison to some live forums or sessions attended by people in person.

There are a number of leading social media platforms that have attracted large numbers of users worldwide. Some of these social media giants which are analyzed in this study are described briefly in the coming paragraphs.

Facebook is one of the leading social media networks operated worldwide. Facebook declared almost 2.8 billion active users monthly ( Facebook Reports First Quarter 2022 Results , 2022 ) in 2020 and was listed as the fourth most used global internet service. Also, it was touted as the most downloaded mobile app in the last decade. Facebook can be simultaneously accessed from multiple internet-connected devices. The first step for Facebook users is the registration of an account that can then be set up with some personal information. The personal profile page of every user stores the content shared by the user and is known as the “Timeline” since 2011 ( Gayomali, 2011 ; Panzarino, 2011 ; Schulman, 2011 ; Knibbs, 2015 ). It allows users to post pictures, videos, and text to be shared either with people added as friends or publicly to people all over the world. Facebook users can interact privately as well through instant messaging and also have the option to join groups and follow pages according to their interests. It played a revolutionary role in interconnecting individuals all over the world and provided a platform to share personal views, opinions, and data with the audience of their choice. It was as early as 2008 that public figures including politicians started exploring this new avenue for information sharing and narrative building ( Carlisle and Patton, 2013 , p. 883–884; Skogerbø and Krumsvik, 2015 , p. 354–355). With time, political communication and marketing have become a new normal globally as Facebook provided a state-of-the-art advertisement platform with a wide audience range ( Bossetta, 2018 , p. 472).

Twitter is among the most popular social media platforms utilized by large corporations, common users, and politicians alike all over the world. Even heads of state actively use this platform for communicating their policy statements on various critical issues. Twitter was launched in 2006 but flourished rapidly in the last decade. It was reported that 340 million daily tweets were posted by around 100 million Twitter users by 2012 ( Twitter, 2012 ). In addition to that, around 1.6 billion searches were handled by the social media platform ( The Engineering Behind Twitter's New Search Engine, 2011 ; Lunden, 2012 ). It is mentioned ( Molina, 2017 ) that the number of active Twitter users surged to 330 million by the start of 2019. It has become a key tool of communication in today's digital world.

Blogs/forums

A weblog or online forum is also referred to as a digital diary where a person can share information globally in the form of posts and initiate a discussion with others as well ( Blood, 2000 ). The posts shared by the users are arranged from the newest to the oldest. Before the last decade, blogs were limited to individuals sharing information concentrated only on a specific topic. However, in the last decade, multiple individuals have been able to collaborate on a wide variety of topics. This has significantly enhanced the internet traffic for blogs and online discussion forums. Universities, think tanks, activists, and even government entities have established these weblogs and discussion forums for disseminating information. Almost all the topics related to general life are discussed here ranging from sports, arts, religion, science to politics, and philosophy. A simple weblog is a combination of text, images, and links to other similar pages on the internet. The interaction of people via public comments is another important part of the blog and online forums. With every passing day, the popularity and number of such blogs are increasing rapidly. Politicians and political organizations have also established dedicated weblogs and online forums to enhance political participation from the general public.

YouTube is a social media platform for sharing video content, and it was launched at the beginning of 2005. It is regarded as the second most searched website after Google Search. It has been estimated that around 2.5 billion monthly users ( Most Used Social Media 2021 , 2022 , p. 2022) on average watch videos for almost one billion hours every day ( Goodrow, 2017 ). Another study estimated in 2019 pointed out that more than 500 h of video content/min is uploaded on YouTube ( Hale, 2019 ; Neufeld, 2021 ). It is claimed to be at the heart of multiple cultural and social trends in today's society. In the field of political communication, YouTube has brought the politicians and common public much closer. A classic example of this is the collaboration of YouTube and CNN for US presidential debates where the common public was able to ask questions directly. Social experts touted that YouTube has altogether altered the political environment ( YouTube News: A New Kind of Visual News, 2012 ). A famous example of utilizing social media for political communication in the past decade is the Arab Spring. One of the leading activists in the Arab Spring pointed out that they utilized Facebook for protest planning, and this was managed through Twitter and shown worldwide through YouTube ( Seelye, 2007 ).

Social media can generate interest in many types of brands, events, products, or services. Andrew Peter, the regional director of The Pacific West Communications, can be taken as an example. He used Facebook for Singapore Tattoo Show to promote and advertise it. He instantly connected with the prospective visitors to that event. Initially, there were 5,000 expected visitors for that event; in the end, around three times the intended audience joined the show, and it turned out to be a huge success ( Scott, 2009 , p. 40–41). This example depicts that social media can be a constructive tool that can facilitate individuals and corporations to spread awareness among common citizens about their products or services.

Social media is an up-and-coming field that is being developed day by day and has been influencing almost every aspect of our lives. The number of instances where social media influenced the political subject matter is already visible in numerous parts of the world. Howard Dean, a Democrat representative endorsed as the pioneer of utilizing social media/internet for promoting political subject matter, performed his duty as the Governor of Vermont (1991–2003) and later ran for president in the 2004 election. Similarly, Barack Obama utilized his Twitter account in the lead-up to the US presidential elections of 2008 for promoting his political viewpoint. Those elections were the first major political event that included the social media impact in forming public opinion on various issues of political subject matter.

Another such example is the Berlin state election of 2011 where the Pirate party astoundingly won 15 seats out of 23. Their success was believed to be largely based on accessing voters via social media. The party is believed to collect its 120,000 votes from a number of different sources like young people voting for the first time, Social Democrats, the silent voters of the past, the Greens, and the Christian Democrats. Young Voters (18–34 years old) voted for the Pirate party in large numbers (one in every five votes). In the same year, the True Finns won the Parliamentary elections of Finland by putting to use social media to influence public opinion on the political subject matter. It was instrumental for them in engaging their believers and also expanding their voter base.

A few years back, the Turkish military wanted to shut down government affairs. This situation was controlled via social media in which messages were sent to the citizens to come out of their homes in support of the government. Donald Trump, then President of the United States, also used social media in the recent US elections and succeeded in influencing citizens. Similarly, Pakistan and India are also trying to influence the world to lean toward their respective points of view through the effective utilization of social media communication channels. Even elections have been carried out in some countries around the globe by utilizing social media platforms ( Lies and Fuß, 2019 , p. 138).

This study focused particularly on the rising influence of social media on the political participation of the common public in Pakistan. The leading political party of Pakistan, namely Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (2021) (PTI), is the most active and popular political force on social media in Pakistan. They utilized it effectively to win the general elections in 2018 and formed the government as well. Let us take a look at some of the factors that attracted the attention of authors for carrying out this research in Pakistan.

Social media politics in Pakistan

It is worth mentioning here that Pakistan possesses the second highest percentage of youth population worldwide and this fact has revamped the political landscape of Pakistan ( Ittefaq and Iqbal, 2018 , p. 4). Among the social media platforms, Facebook is the most widely used platform for political communication, although globally Twitter is the most widely used for political communication. The influence of social media on the political landscape of Pakistan started growing rapidly in 2008 ( Eijaz, 2013 , p. 117). Internet penetration is relatively low in Pakistan as compared to other regional countries. However, the situation is gradually improving. One of the recent surveys in Pakistan showed that only 19% of people have internet access. The situation is rapidly changing with the increased utilization of technology (particularly social media) in various critical areas like health, politics, and education. This prompts increased research content on dissecting the influence of social media use ( Ittefaq and Iqbal, 2018 , p. 3–4).

Social media platforms have turned out to be a much-needed social space for the average citizen to express their opinions and engage in meaningful debate on a number of complex, social, and political issues in Pakistan. This has in turn improved the turnout of the general elections considerably ( Ahmad and Sheikh, 2013 , p. 353–354). Similarly, another study ( Zaheer, 2016 , p. 281–282) focused on university students and analyzed the impact of social media on the political participation and perception of students in Pakistan. It revealed that online activism had a great impact on encouraging the student's involvement in political debates and activities. The study was carried out in one of the biggest cities in Pakistan.

According to one of the recent surveys, 44.61 million people in Pakistan are internet users and 37 million people of these are active on social media platforms. The survey further analyzed the usage of popular social media platforms and reported 36 million Facebook users, 6.30 million Instagram users, 2.15 million Snapchat users, and 1.26 million Twitter users. It also pointed out that 77% of the total active social media users are 18–34 years old. This confirms that mostly young people in Pakistan are actively utilizing social media (We Are Social, n.d.). Another similar survey carried out in 2018 found that 22% of the total Pakistani population are internet users. Out of this 22% users, the social media users are 18%. This survey also confirmed that the majority of social media users are the youth of Pakistan.

Due to the large youth population of Pakistan, politicians make an effort to encourage them to vote for them. The popularity of social media among the youth has made it the most attractive platform for political communication in election campaigns. Large and popular social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are used to target political communication campaigns ( Kugelman, 2012 ). The utilization of social media for political marketing is now a very common practice globally. All the major political parties maintain their active presence on social media platforms to effectively communicate their policies and opinions. Michaelsen (2011 , p. 37–39) also discussed the impact of technological revolution and in particular, social media on political involvement all over the world. It asserted that predominantly young people of Pakistan have adopted social media as the most common mode of communication and interaction. The advent of social media has opened up new avenues of information for the common public and there is an increased probability that anyone could gain access to the required information to a larger extent ( Kugelman, 2012 ).

Significance and contributions

Social media has played an instrumental role in creating more political sense and social awareness among the citizens and have encouraged them to share their opinions. The policies supposedly created for the benefit of citizens should take into account their requirements, needs, and wishes. The novelty of this research idea is in the promotion of social media as a platform for the politicians to build their narrative in front of the citizens while simultaneously allowing them to give their feedback, enabling a trusting bond between them. This study emphasizes developing a trustworthy bond between politicians and citizens. It is necessary that politicians remain accountable to the public because the citizens elect them for the betterment of themselves and their country. The end goal of this research study is to get answers which can enable politicians to improve their relationships with the common citizens via social media. They can also utilize the social media platform to make people more cognizant of their agendas, thoughtfulness, and future plans.

In going through the related literature, a research gap was identified in “Brand strategies in social media, Georgios Tsimonis and Sergios Dimitriadis Department of Marketing and Communication, Athens University of Economics and Business, Athens, Greece” ( Tsimonis and Dimitriadis, 2014 , p. 328–344). This research study analyzed the brand strategies promoted through social media channels for the virtual benefit of customers. It recommended dissecting social media's influence on the relationship between government/politicians and citizens. In our view, there are no such particular research articles focused primarily on this topic. Hence, the authors performed a simple analysis of politicians' and citizens' relationships previously ( Fatema et al., 2020 , p. 110) without considering the moderating effect (which is included in the research model for this study). The major objectives of this research article are listed below:

• Study the influence of social media on politicians' and citizens' relationships.

• Analyze the impact of political slogans of four main Pakistani political parties on politicians' and citizens' relationships.

• Examine the moderating effect of political slogans on politicians' & citizens' relationships.

This stated research can contribute to the overall study of this topic in a number of ways:

• It can open up a new path in the research arena as very few studies in the past have addressed the relationship between politicians and citizens in quantitative, cross-sectional research design.

• Also, this study adds a new dimension to the research arena as it intends to investigate the moderating effect of political slogans as a moderator.

• This research study also introduces use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis for social media studies.

• Last but not least, this study helps politicians a lot in their promotion and crafting of their positive image in front of the citizens through social media.

Literature review

The word “social” means “connection with the society,” the interaction with the people, and the word “media” means “the medium by which information is conveyed to the world.” The combined term “social media” means the medium by which people share information about different things or scenarios ( Auvinen, 2008 , p. 8). It has become necessary for people to get information about anything via different online sources. The terms “social” and “media” are very much interrelated but not perfectly synonymous, and they are used in different ways.

Social media is heralded as an interactive platform, intended to enhance communication among individuals and corporations via the exchange of ideas, photos, and videos. They have become an integral part of modern marketing plans for any corporation or individual and may as well replace the older and traditional marketing tactics completely ( Vera and Trujillo, 2017 , p. 603–605).

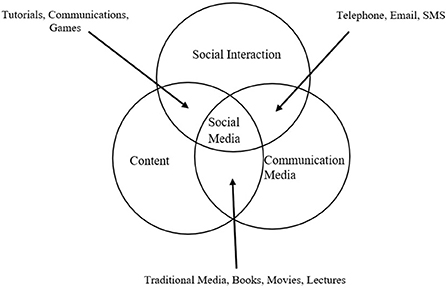

The three rudimentary and interconnected fragments of social media are social interaction, content, and communication media ( Dann and Dann, 2011 , p. 345–346). Figure 1 illustrates how social media is constructed through the interconnection of these three fragments. These three rudimentary fragments should be available in time so that the basic requirements can be completed properly. Social interaction is the link between social media users and others via social media services. Content is defined as the data that is available on social media and can attract social media users. Lastly, communications media is described as the platform that facilitates sharing of subject matter and communication between the users. Several research studies concluded that social media users intend to satisfy their specific wants and targets via social media use that they are unable to fulfill otherwise ( Raacke and Bonds-Raacke, 2008 , p. 170; Macafee, 2013 , p. 2767–2768). People naturally need social media in this global era of technology, as communication is a basic necessity. Every individual can approach the openly shared information. These acts have local as well as global impacts. Social media can create and elevate the concept of “brand awareness” ( Fanion, 2011 , p. 76–77).

Figure 1 . Social media components.

There are incalculable advantages to social media. Social media has altered people's thoughts and thinking processes. It has changed the way people communicate. It has provided a better platform for people to communicate and share their feelings and thoughts. The advantages given by social media are discussed below. The eight key changes that are provided by social media are described here briefly.

• The first change is the secrecy of its users, which means that those who comment mostly use nicknames or assumed names.

• The second change is the variety of information social media presents.

• The third change is omnipresence. It means that there are no longer any places to hide. Through social media, our life becomes a public space.

• The fourth change is rapidity and speed. Presently, a day's worth of information is dissemminated in minutes. In the past, it was very difficult to spread any information fast.

• The fifth change is the relationships made by social media.

• The sixth change is the shift from the objective to the subjective.

• The seventh change is that recorded information is transformed. Through social media, pictures and videos are not only shared but can also be transformed into a combined format.

• The eighth change is how though a government can limit or restrict the information on social media, customary censorship cannot keep up with altering web pages.

Almost every person utilizes social media in one way or the other. It has become a necessary part of everyday lifestyle. It is very helpful and informative as well. Social media networks are structures linked with individuals and corporations with interlinked emotional or fiscal values. In other words, it is a conduit for numerous kinds of people who exhibit a distinct set of behaviors ( Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2011 , p. 587; Alnsour and Al Faour, 2020 , p. 81); this study examines the result of informational motivations for social networking sites. Safko (2010 , p. 24) described social media as a collaborative communication platform where corporations can focus on customers' needs and expectations.

Cao and Havranek (2013 , p. 7−8) concluded that people are at the heart of social networking sites' operations rather than the commodity. Social media can help corporations understand consumer behavior better, which can in turn lead to improved commodity performance ( Keegan and Rowley, 2017 , p. 19). According to Evans (2008 , p. 263), social networking sites provide insight into real people with shared interests and incorporate individual experiences as well. Brand awareness is largely due to social media and it has been increasing with every passing day ( Fanion, 2011 , 76). Gummerus et al. (2012 , p. 859) ascertained that social media is not solely for work but also forms the basis for good associations and entertainment benefits.

Social media and politics

Previous studies have shown that traditional media plays a key role in shaping pictures of the privileged (sometimes over the top) with the imagery used in many cinemas around the world ( Fiske, 1994 , p. 189–198; Callaghan and Schnell, 2005 , p. 180). The political scenario is “medialized”, which leads to political figures following media trends ( Schultz, 2004 , p. 225; Strömbäck and Esser, 2009 , p. 208). In contrast, social media eliminates the typical journalist or media role, and one is in charge of one's own self image in the public eye ( Salgado and Strömbäck, 2012 , p. 144–161). Social media provides political figures to construct their image in their own way by themselves.

Some researchers have equated internet presence to political activity ( Tolbert and Mcneal, 2003 , p. 176–177; Polat, 2005 , p. 437–438; Scholl, 2009 , p. 478). Kruikemeier et al. (2013 , p. 54–55) established that social media interaction by politicians can impact the participation of the citizen in the political subject matter. Kobayashi and Ichifuji (2015 , p. 575–577) have also concluded in their study that repeated interaction through Twitter has a positive impact on the political behavior of users.

Marketing professionals have focused their energies on increasing the number of social media users ( Mohan and Sequeira, 2016 , p. 15). Social media giants like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, MySpace, and Wikipedia are widely known communication websites. They are also known as “Web 2.0” tools. Web 2.0 is a specific term that describes the 21st century Internet as a place where the users can yield and share ideas, share any piece of information with others, co-operate and help each other, etc. ( Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010 , p. 60–61).

Previous research states that politicians use social media for promoting themselves (as individuals as well as the political party office bearer) using ideas and policies they want to put into practice ( Enli and Skogerbø, 2013 , p. 760). Thorough studies have also disclosed how the use of social media by politicians affects the citizens as their potential voters. They found that the citizens' reaction to politicians who use Twitter in a more personalized way was more positive compared to others as it shows the humane and normal prospects of their lives which are otherwise unknown to the citizens. This shows that politicians who are more active and interactive on social media are more popular and likable in the eyes of the citizens. Results from the study of Parmelee and Bichard (2011 , p. 164) on Twitter in American politics state that followers get frustrated when any politician uses Twitter or any other social networking site for one-way communication instead of two-way.

Digital marketing and personal branding

A brand is an older generic term that generally points to the organizations and their products that are available to the users. Personal branding, on the other hand, is a newly invented terminology that has not been widely accepted as an academic term, but with the growing influence of social media in this modern age, personal branding has taken the shape of a handy product. Building or creating a brand is a topic that has a divided opinion across both literature and history. Kapferer (2008 , p. 13) is a staunch believer of this concept but at the same time ( Grönroos and Helle, 2010 , p. 566) has emphatically stated that it is not a pre-requisite in this discussion. Kapferer (2008 , p. 182) further defines branding as an impalpable asset and a basic tool for creating value in this modern age.

According to Hughes et al. (2008 , p. 1–2), a personal brand can be identified as a branch of brand theory and can be defined in the terms of a person's name, emblem, character, or design or their combination which in turn targets the facilities of a seller or a network of sellers helping them in differentiating among the chief competitors. Another major authority in this field is known as “The American Marketing Association”. It has defined the terms brand and branding as follows: “A brand is a customer's experience represented by a collection of images and ideas; often, it refers to a symbol such as a name, logo, slogan, and design scheme.” Brand image and brand identity are seen many times and are a common occurrence in the related literature ( Kapferer, 2008 , p. 173–174; Grönroos and Helle, 2010 , p. 568).

Millions of people are interconnected through this common medium of communication known as social media or digital media. Brand awareness is created when the firms advertise and promote their brand names on different social media websites and the huge number of people who use those websites get acquainted with those brand names and become potential consumers ( Alford and O'flynn, 2012 , p. 34–35). In a nutshell, social media nowadays acts as a platform to construct one's brand with the help of various tools. As described by Schawbel (2008 , p. 22), “In the digital age, your name is the only currency”.

A large number of research studies focused on the terms of digital marketing and brand strategy. Social networking sites have revolutionized the interaction of brands with their respective consumers. One of the key advantages of these platforms is the ability to understand consumer behavior and ability through feedback ( Radpour and Honarvar, 2018 , p. 54). The under-discussion research topic is linked with both branding and digital marketing. A politician who wants to establish a good relationship with the public is considered a “Brand” in this case: “Branding is a marketing strategy which involves creating a differentiated name and image in order to establish a presence in the customer's mind, attract customers and keep them loyal to the brand”. In this research study, the politician wants to promote themself via social media, which includes Facebook, Twitter, etc. This type of promotion comes under the umbrella of “digital marketing”. The term is described as the selective, quantifiable, and collaborative marketing of any commodity/amenities by utilizing digital technologies to enhance the number of customers and keep hold of them too.

The connection and relationship between politicians and citizens are studied under the banner of public relations (PR) strategies. Social media includes social networking sites (SNS) that act as a major platform to achieve or establish such a kind of connection. SNS, such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, etc., have quickly established themselves as one of the most effective means of influencing the relationship or connection between the citizens and their elected representatives (politicians). The relationship established through SNS can serve various purposes like influencing a campaign for the election of a candidate, promoting political ideology, accomplishing an objective, or incrementing a quota of funds. It has become one of the most powerful weapons to achieve any selected goals in this modern era of this digitalized world.

Political communication

Increased utilization of social media among the public has enhanced their receptivity to political communication. Almost all the political forces have reformed the traditional communication channels through the integration of digital communication methods. It involves creating specific blogs and websites to communicate their political opinions directly and more effectively to the common public in addition to their active presence on social media platforms ( Serrano et al., 2018 , p. 7–8; Papakyriakopoulos et al., 2018 , p. 2). The ability of the public to interact directly with the political forces by commenting has altered the traditional political communication channels. The interaction between the public and political forces on social media platforms is in stark contrast to the traditional communication channels ( Mccombs and Shaw, 1972 , p. 185–187). The role of a field journalist is reduced marginally due to the ability of political forces to interact directly with the common public via social media platforms. The social media platforms put into use certain recommendation procedures to distribute political content to like-minded common public users ( Bakshy et al., 2015 , p. 1131–1132). Political communication is either accessed directly via interpretation or indirectly through various related social media posts by the public ( Choi, 2015 , p. 697–700; Hilbert et al., 2017 , p. 445–446). Social media users can react to political communication in two ways. The first option is to react via social and political activity and the other option is to react publicly by commenting on the shared political communication. The direct interaction of the common public has the dual impact of influencing the passive users of the social media platforms and pressurizing the political forces to act in a certain manner. This modern political interaction has completely altered political communication. The amalgam of publicly commenting on the political content and publicly discussing the political content with other common public users has made social media a place of combative diversity. Social media platforms act as a place for sharing opinions and receiving feedback, which forms the basis of political communication. Online political discussions protected under democratic principles lead to “conflictual consensus” ( Doucet, 2002 , p. 143), which further extends to social choices. Therefore, it would not be an exaggeration to hold social media platforms responsible for enhanced political participation by the common public.

The direct exposure to political forces through social media platforms with concerted political opinions and demographic features has forced the public to adapt accordingly ( Nielsen and Vaccari, 2013 , p. 2336–2338; Schoen et al., 2013 , p. 532–533; Diaz et al., 2016 , p. 2–5; Jungherr et al., 2016 , p. 52–53; Hoffmann and Suphan, 2017 , p. 552–553). Hence, the political forces keep all these aspects in mind to tailor political communication to platforms like Twitter.

Politics and citizens

Political trust is defined in terms of the performance of politicians and government entities in ralation to public expectations ( Miller and Listhaug, 1990 , p. 358). Rigorous studies have revealed a deeper connection among informed users and indicate that their political opinions are formed more in line with the socially active politicians than the uninformed users who do not follow any political discussions online ( Moy et al., 2005 , p. 572; Shah et al., 2001 , p. 154; Wellman et al., 2001 , p. 448–450).

Most businesses have focused on social networking sites based on the user's motivations and features ( Boyd, 2004 , p. 1; Sweetser and Lariscy, 2008 , p. 179–180; Papacharissi, 2011 , p. 304–318). Little to no attention has been given to how social networking sites influence the political participation of citizens who are users of those platforms and how that can lead to the increase or decrease of their confidence in their respective governments. Online or digital communication can be the catalyst for engaging younger people in political subject matters ( Lupia and Philpot, 2005 , p. 1125). Similar views were echoed by Lee (2006 , p. 419–421) who deduced that active online participation in politically active forums or groups leads to higher political participation of individuals.

The repeated appearance of content related to the political subject matter on SNS encourages users to express their political opinions more freely without it being taken as offensive or too sensitive a topic to be discussed openly ( Vitak et al., 2011 , p. 109–111; Halpern and Gibbs, 2013 , p. 1161). Social media or SNS gives everyone a platform where they are free to build their persona in any way they prefer while allowing them the luxury to control how many real-life details they are willing to share publicly ( Enli and Thumim, 2012 , p. 10; Enli and Skogerbø, 2013 , p. 763). Increasingly intimate communication through SNS, such as Twitter and Facebook, further emboldens this image among the followers who act in a positive way toward politicians ( Kruikemeier et al., 2013 , p. 60).

The political work of a slogan

The political scientist, Murray Edelman theorized about politics and its actors as a “constructed spectacle” ( Burnier et al., 1994 , 242–244). Edelman pointed out that politicians' portrayal of themselves aims at legitimizing their own being and doing. For Edelman, analysis of politics and politicians is done by watching what they do, how they present themselves, and also by examining their language. The symbolism of various kinds is an important key for use in both language and gestures for actors in politics.

Political slogans are the basis of any political campaign and are formed to serve particular political gains. They are among the most prominent and regularly employed symbols of a politician. They target a particular social or economic issue and present their position in the form of slogans as they are seen to be more effective. Space limits can be placed on a campaign poster or an ad banner, and time limits can affect what can be said in a television advertisement or a message aired on the evening news. However, a sharp and concise slogan can overcome these restrictions by giving a louder and clearer message ( Hodges, 2014 , p. 349).

Historical review of political parties

The four major political parties under discussion took part in the general elections of Pakistan (2018) in which PTI emerged as the most successful party. It bagged a total of 16, 903, 702 votes in the national assembly securing 156 seats out of 342. The second most successful party in terms of bagging the second highest number of votes was Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz [PML (N)] which got 12, 934, 589 votes and took 85 seats in the national assembly. Pakistan's People's Party (PPP) appears the third highest vote getting party taking 6, 924, 356 votes and securing 64 seats in the national assembly of Pakistan. Several Islamic parties also took part in these general elections with different names and got 2, 573, 939 votes in total, bagging 16 seats in the national assembly ( Election Commission of Pakistan, 2020 ). Let us have a brief look at each of the four main political forces in Pakistan.

Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz

Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz is a faction of the All-Pakistan Muslim League that played a primary role in the creation of Pakistan. General Zia dissolved the government in 1987 and elected the National Assembly. This is the era when PML was divided into a number of factions. In 1993, Muhammad Nawaz Shareef laid the foundation for PML (N). After going through a lot of purging, the Pakistan Muslim League (Quaid-e-Azam) PML (Q) and PML (N) remain the survivors so far. The political slogans change with time, and currently, the main slogan is, “Vote ko izzat do (Respect the vote)” ( Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz, 2021 ).

Pakistan Tehreek-E-Insaf

This political party was established in 1992 by Imran Khan. It is devoted to combating injustice in our daily lives and establishing a society based on the principles of equality, justice, and fair play for every citizen of Pakistan. They have called for a change in the name of establishing a Naya Pakistan. Their social media campaign is hailed as a gamechanger in the politics of Pakistan and effectively played the key role behind their ascendance to power in 2018. Their political slogan is to end corruption to ensure justice and accountability for all.

Pakistan's people's party

The inaugural session of the PPP was held in Lahore from 30 November to 12 December 1967. At the same meeting, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was elected the president. The party pledged to eliminate the feudal system by the established principles of socialism and to protect and improve the interests of farmers ( Pakistan Peoples Party, 2021 ). The PPP actively participated in politics with the slogan of “Roti, Kapra Aur Makan” (bread, clothes, and shelter) and “all Power to the people” ( Pakistan Peoples Party, 2021 ).

Religious parties

Religion has always played an important role in the history of Pakistan and has been an active part of the politics of Pakistan. Pakistan's people believe that politics or religion is an inter-related thing and cannot be separated. They form an important part of the political history of Pakistan. Their political slogan is to implement and practice the Islamic governance system ( Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan, 2020 ).

Base theory and framework

The base theory for this research is the “Theory of self-presentation and self-disclosure” or “Impression Management Theory” ( Goffman, 1959 , p. 141; Schau and Gilly, 2003 , p. 387). Although some similar theories suggested earlier focused on the performance of a person, this is the first theory that is peculiarly focused on the self-presentation topic. The basic idea behind this theory explains that individuals are more open to promoting information that is aligned with their own opinions, and hence, they strongly believe that it will cause a positive impact on the people.

The impression management theory is among the most cited theories in research matters linked with self-presentation or identity presentation. The author of this theory argued that an individual's actions are based on the people surrounding him. The image portrayed through those actions (in line with the audience's preferences) is carefully thought off beforehand by the individual. The impression management theory not only focuses on the mask an individual put on in connivance with the audience's preferences but also sheds light on the thought process behind it.

The basic ideology behind this impression management theory, as quoted by the authors, is to control one's image in front of the surrounding people and build a persona. To influence and mold the opinions and actions of the surrounding people, one can portray specific impressions linked to one's capabilities, personality, ideas, emotive state, and other related traits. The creation of one's image in the eyes of the surrounding people can play a critical and constructive role in achieving preset goals and ambitions.

Research methods

There are two main types of research methods, quantitative research and qualitative research ( Ghauri and Gronhaug, 2005 , p. 109). To solve a particular problem, the research is done using one of the above-mentioned research methods. They are briefly described below.

Qualitative method

Qualitative research is utilized when the research article employs descriptive data based on conceptualization as endorsed in previous research articles ( Ghosh and Chopra, 2002 ; Ghauri and Gronhaug, 2005 , p. 110). When the concerning variables that are responsible for generating an outcome are not obvious, or when the number of participants or results under research is insufficient for statistical analysis, the qualitative research method is utilized. Participants of the research might range in magnitude from a single person to vast groups, and the topic of research can range from a specific demeanor to the operation of a large and multifaceted organization. Researchers are most interested in analyzing people's convictions, enthusiasm, and behavior, as well as those of organizations. Designed or unrestrained interviews, observation via participation or exterior observation, and scrutiny of inscribed information are all common examples of research approaches. When contextual forces are vague, overwhelming, or sensitive to external stimuli, qualitative methods are the most suited research method.

Quantitative method

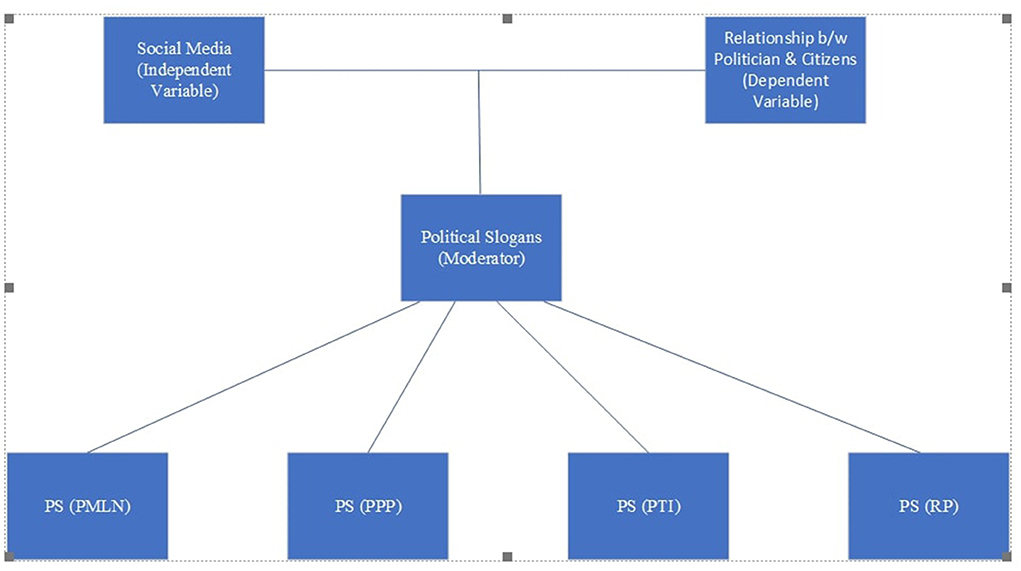

Quantitative research is used when the research article intends to calculate and analyze the numerical data results ( Saunders et al., 2009 , p. 161). The basic ideology behind this research method is to critically analyze the impact of peculiar conditions known as independent variables on the consequence of interest also known as dependent variables in a numerical manner. Under these circumstances, observers usually draw interpretations from direct observation methods like real experiments. Another possibility is to draw interpretations through affiliations formed as a result of performing a statistical analysis technique. These interpretations are most accurate in cases where the contributing factors are tightly managed and are free from any unobserved interference. In these specific situations, the predicted results are deemed more reliable and effective. Based on this literature review, the following theoretical framework for this research study is proposed in Figure 2 given below.

Figure 2 . Theoretical framework.

Hypothesis formulation

Based on this literature review, a set of nine alternative hypotheses are proposed in this research article to achieve the objectives highlighted in the aforementioned sections. They are presented here as follows:

H1: Social Networking sites and politics have a significant and positive impact on politicians' and citizens' relationships.

H2: The political slogan of PML (N) has a significant and positive impact on politicians' and citizens' relationships.

H3: The political slogan of PPP has a significant and positive impact on politicians' and citizens' relationships.

H4: The political slogan of PTI has a significant & positive impact on politicians' & citizens' relationships.

H5: The political slogan of religious parties (RPs) has a significant and positive impact on politicians' and citizens' relationships.

H6: The moderating effect of the political Slogan of PML (N) positively moderates the relationship between politicians and citizens.

H7: The moderating effect of the political slogan of PPP positively moderates the relationship between politicians and citizens.

H8: The moderating effect of the political slogan of PTI positively moderates the relationship between politicians and citizens.

H9: The moderating effect of the political slogan of RP positively moderates the relationship between politicians and citizens.

Research methodology

Sekaran and Bougie (2016 , p. 87) recommend that if the research article intends to carry out hypothesis testing, the quantitative research method is the more suitable option. The deductive approach is put into use for hypothesis formulation in this study. Brink and Wood (2012 , p. 49) explain that in the quantitative method, the data related to hypotheses is collected and then fed into the software for testing purposes. These tests will provide the true fundamentals and figures, which will play a central role in explaining the research hypothesis precisely. In this study, quantitative data was obtained via questionnaires. There is no limitation of demographic elements like gender etc., imposed while conducting this research through the questionnaire. A few open-ended questions were included in this questionnaire as well to encourage the participants to express their views and opinions. The Likert scale technique was use for the questionnaire.

Sampling design

This study approaches the people who use social media for a variety of purposes. The survey is aimed at evaluating the influence of social media on citizens and their opinions regarding the particular political subject matter. A convenience sampling technique is used. The sample size is 300 individuals in this cross-sectional study. The data are collected only once through the questionnaire in January and February of 2022 for hypotheses testing ( Sekaran and Bougie, 2016 , p. 88). The questionnaire was adapted and modified to gathering responses from social media users (respondents in this research). The two major variables of this research article are as follows:

• Social media and politics

• Relationship between politicians and citizens.

All the items for these two variables are adapted ( Lee, 2013 , p. 62).

Validity and reliability

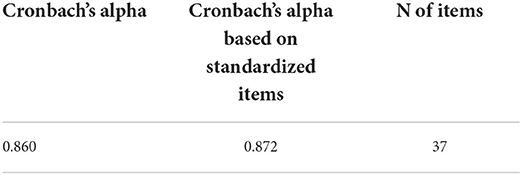

To ensure the validity and reliability of the data collected through the questionnaire, it is first pilot tested. This helps to avoid any issues the respondents might encounter while filling it. Hence, the questionnaire is pilot tested and checked properly. This study specifically investigated the numerical analysis of the data collected via questionnaires to verify the data. In the literature on reliability analysis, Cronbach's alpha is very important. It is the basic measure of reliability ( Cronbach, 1951 , p. 15). The Cronbach's alpha is 0.860 (calculated in SPSS) for the dependent variable (politicians' and citizens' relationship). As the value shown in Table 1 is larger than 0.5 (typical benchmark), it implies that the instrument (questionnaire) is reliable.

Table 1 . Reliability statistics.

Measurement technique

The software applied for this research is Smart PLS for data analysis. The PLS has the ability to do multiple analyses and also saves time in recent high-ranked journals ( Baraghani, 2008 ). The name “path-modeling technique,” has been given to this technique due to its ability to run numerous compound analyses simultaneously. Researchers use PLS more in recent publications as well for statistical analysis ( Hair et al., 2011 , p. 148). Moreover, the most advanced form of regression analysis is structural equation modeling (SEM) ( Wong, 2013 , p. 2). The researchers can get different results at the same time by using this method. Hence, the SEM analysis is carried out in smart PLS software for this study.

Data analysis

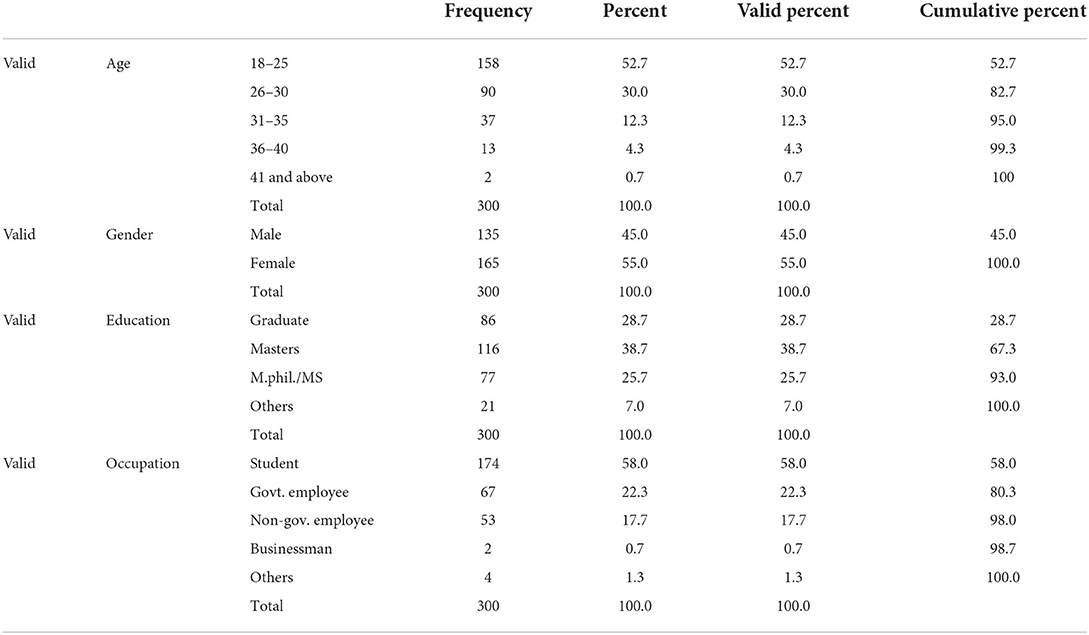

Descriptive statistics (demographic).

Descriptive statistics provides the demographic dynamics of the data collected by the individuals. Morgan and Hunt (1994 , p. 32) state that demographic statistics evaluate the gender-based difference. Table 2 shows that the percentage of respondents aged 18–25 years is greater than others at 52.7%. Further, it explains that 55% of respondents are men, and the other 45% of respondents are women. The total sample size is 300 individuals of which 135 respondents are women while 165 respondents are men. In the next part, it explains that the main proportion of the respondents has a master's education qualification. In the last part, it illustrates that 58% of the respondents are students while the others have less percentage.

Table 2 . Descriptive statics (demographic).

Social media (general background)

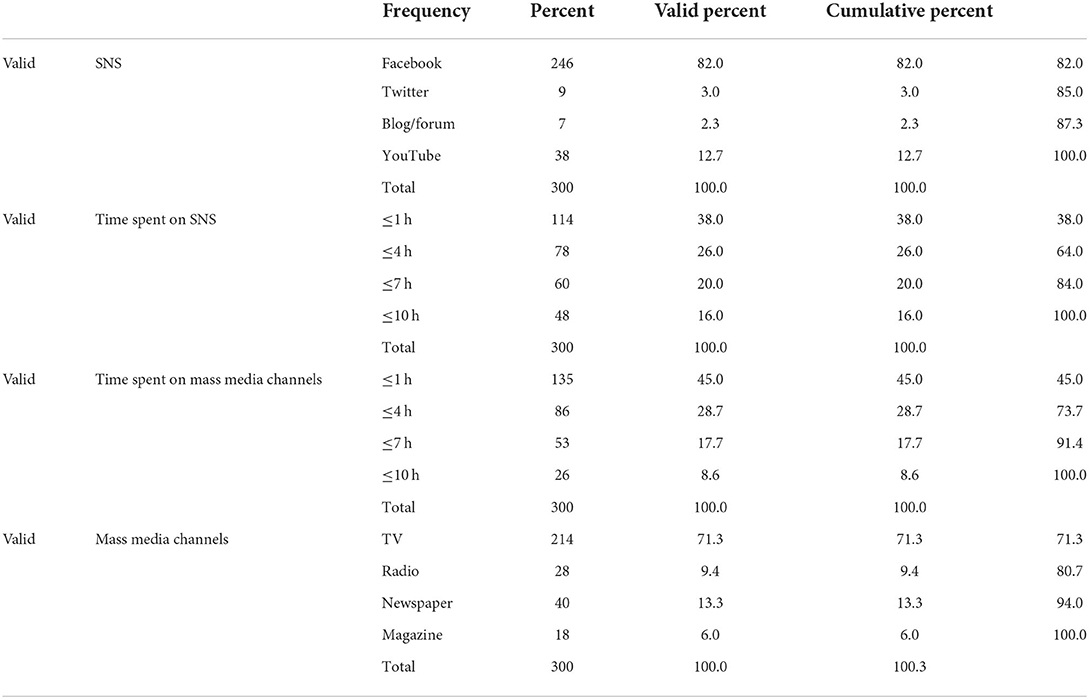

Table 3 given below shows that the percentage of Facebook users is greater than other social media site users (82%). This table shows that out of 300 individuals, 246 users use Facebook more than other sites. In the next section, it explains that 38% of people use social media sites for 1 h per week. Similarly, it further shows that 45% of people prefer to use Mass Media channels for 1 h per week. Others use mass media channels for more than 1 h a week. At last, the table explains that 71.3% of the mass media channel users prefer to use a TV for the purpose of getting information while the others use magazines, radio, and newspapers.

Table 3 . Descriptive analysis (social media).

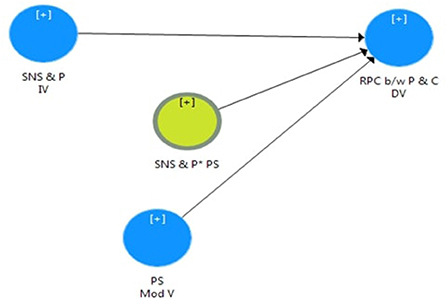

Figure 3 shows the basic model of this study. In this figure, SNS and politics are independent variables and the relationship between politicians and citizens is a dependent variable. In this model, political slogans are the moderator variable. Further, this moderator variable has four dimensions i.e., political slogans of basic four Pakistani political parties. The four basic parties which represent most of the population of Pakistan are PML (N), PPP, PTI, and RPs. Their political slogans are as follows:

Figure 3 . PLS basic model.

PMLN: Vote ko Izzat dau (respect the vote)

PPP: Roti, Kapra aur Makan (bread, clothing, and housing)

PTI: End corruption, Justice for all.

Religious Parties: Implement fully the Islamic system of governance.

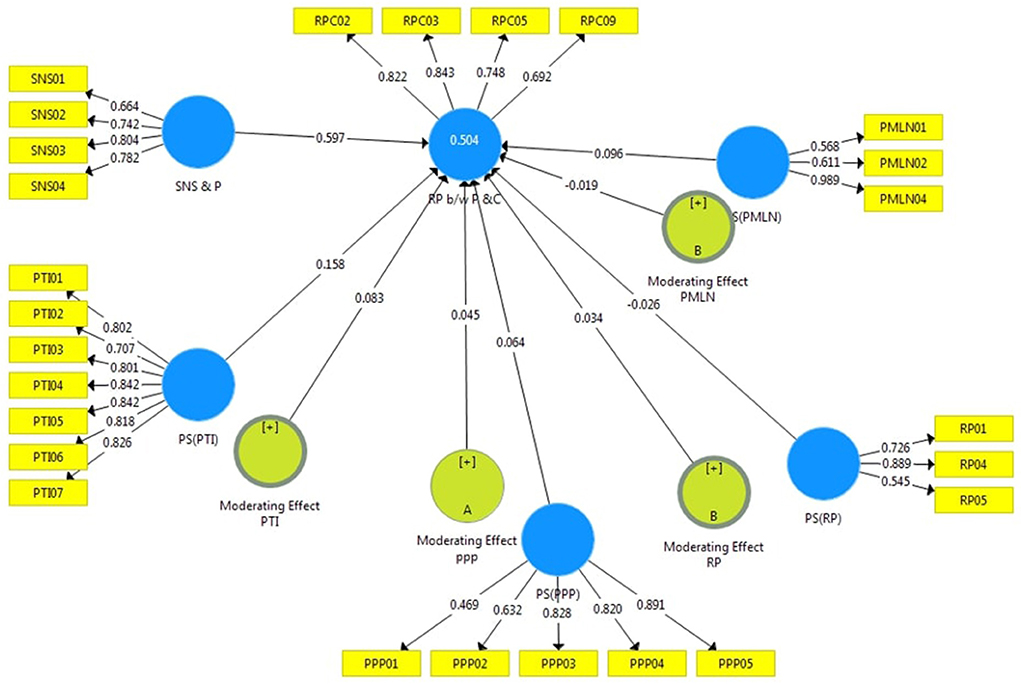

The PLS-Algorithm and Bootstrapping are calculated in Figure 4 because the basic purpose of this study was to compute the results of the political slogans of four parties individually. Hypotheses are created based on Figure 3 . The results are discussed in the coming sections on the based selected parameters.

Figure 4 . PLS-SEM model.

Reliability

Wong (2013 , p. 2–4) showed that the PLS-SEM model should be evaluated in a study of the manuscript covering the eight basic things. These eight things include reliability indicators and internal consistency, loading external models, endogenous variables, convergence and difference validity, path coefficients, and structural path differences. These eight things have been followed by the minimum thresholds required.

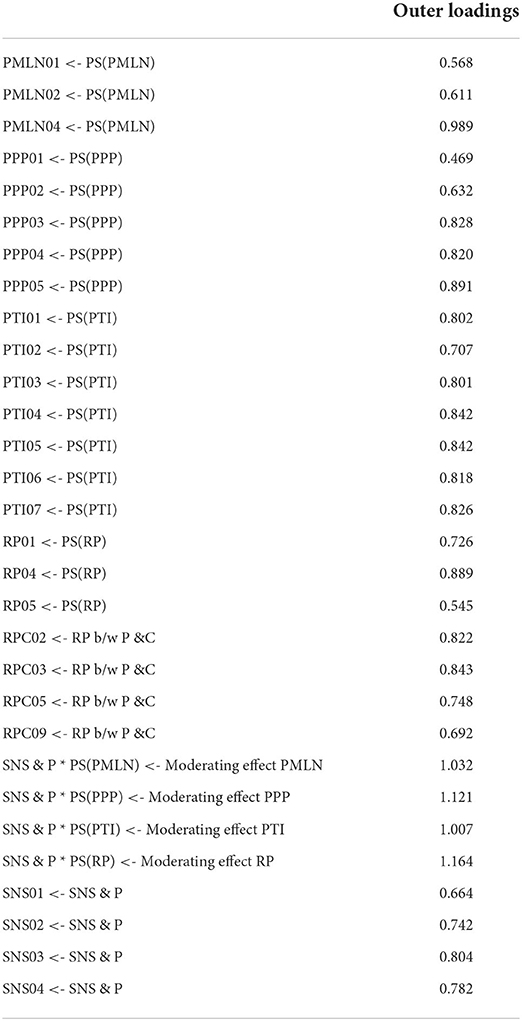

Outer loadings reflect the correlation between the item and its corresponding latent variable. The outer loadings of all the items forming a part of the model have a value greater than the minimum acceptable value of 0.7 because before bootstrapping, the items having outer loadings <0.7 were removed ( Wong, 2013 , p. 8).

In addition, the indicator reliability has the minimum acceptable value of 0.4, preferably 0.7. Table 4 given below shows that each item considered in the model has a value >0.4 indicator reliability.

Table 4 . Item's reliability and loading.

Composite reliability

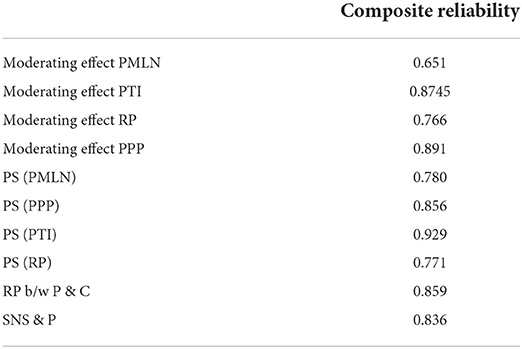

The minimum acceptable value for the internal consistency reliability of each latent variable model must be >0.7. Table 5 shows that each latent variable has a composite reliability value more than the minimum acceptable value of 0.7 in the model.

Table 5 . Composite reliability of latent variables.

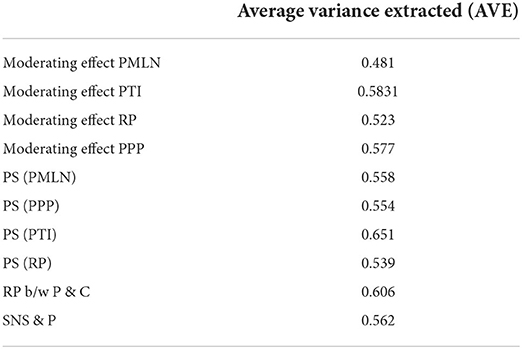

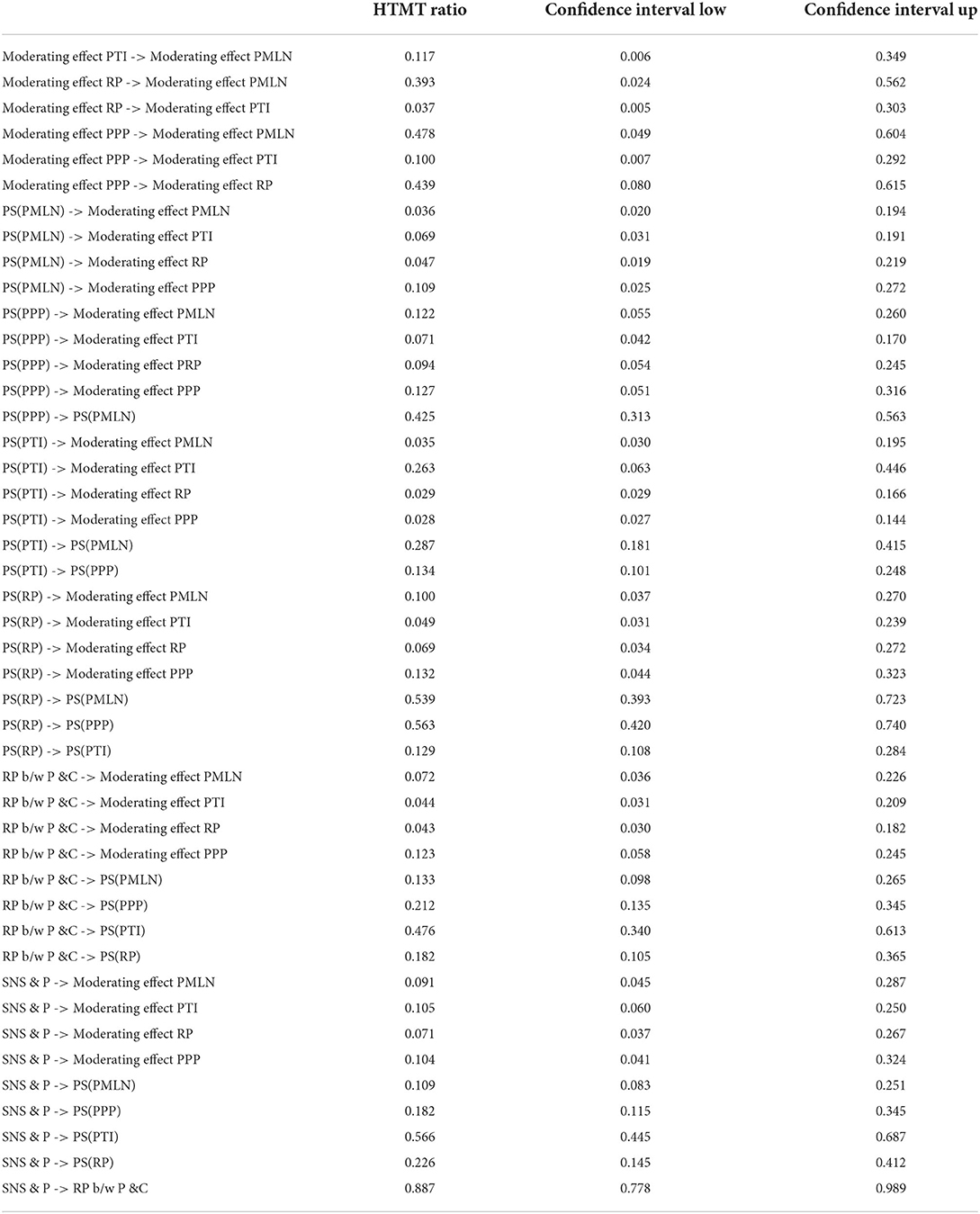

The convergence validity of the data is evaluated by the AVE (mean-variance) in the PLS evaluation. All the data values are above 0.5 as shown in Table 6 (lower limit for data validity). Wong (2013 , p. 6) recommended that the off-diagonal values in the latent variable correlation must be lower than the diagonal ones in case of discriminate validity. The heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) value should be lower than 0.9 with a confidence interval lower than 1 ( Henseler et al., 2015 , p. 123). Table 7 shows that both the HTMT value and confidence interval are <0.9 and 1, respectively. Therefore, the related variables bear the convergent validity in the model.

Table 6 . Convergent validity.

Table 7 . Discriminant validity.

R 2 for the research model

For the dependent variable (relationship between politicians and citizens), the coefficient of determination is 0.504. This means that the independent variable (SNS and politics) explains 50.4% variance in the dependent variable. It demonstrates that the adopted research model has the robust quality to explain the phenomenon.

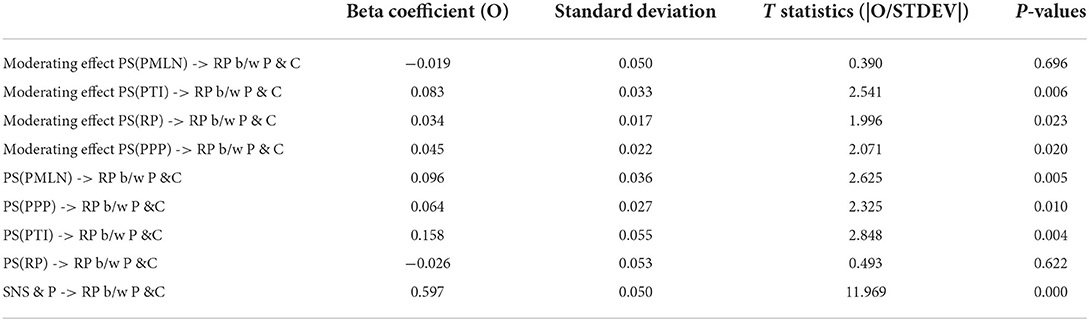

Path coefficient for the research model

Path coefficient of this research model shown in Table 8 depicts that SNS and politics have the most dominant effect on RP between politicians and citizens (0.597) as compared to other moderator variables, such as PS-PTI (0.158), PS-PPP (0.064), PS-RP (−0.026), and PS-PML (N) (0.096). The path relationship between independent and dependent variables is significant. The path relationship between the four dimensions of the moderator and the dependent variable is not significant as their values are <0.1 ( Hair et al., 2012 , p. 332) except for one dimension, i.e., PS-PTI (0.158), because its value is greater than (0.1). Therefore, it can predict that PS (PPP), PS (RP), and PS [(PML (N)] are not strong moderators (dimensions) in the relationship between politicians and citizens.

Table 8 . Path coefficients.

Moderation impact

Two-stage PLS ( Henseler and Chin, 2010 , p. 86) is applied in this research study for analyzing the moderate effect of Political Slogans on the relationship between politicians and citizens. Table 8 shows that the path co-efficient of the interaction terms has positive values except for the relationship between the moderating effect of the political slogan of PML (N) on the relationship between politicians and citizens. This study is conducted to investigate the effect of moderation that weather it is positive or negative. The β and p -values indicate that the moderation is positive in the case of political slogans of PPP, PTI, and RP. The most significant of all the interaction terms is the moderating effect of PS(PTI), which has values of β = 0.08 and p = 0.05 because the β value should be equal to 1 and the p -value should be <0.5. The path model is modified and turned into a single indicator in this research model ( Henseler and Chin, 2010 , p. 84) as depicted in Figure 4 .

Assessment of the hypothesis

H1: Social Networking sites and politics have a significant and positive impact on the relationship between politicians and citizens.

It is positive and significant as β is 0.597 and the p -value is 0.000. The value of the T -statistic is 11.969 which is larger than 1.96. Also, the p -value is lower than 0.05 so, the impact of SNS and politics on the relationship between politicians and citizens is positive and significant. Therefore, the hypothesis is accepted.

It is positive and significant as β is 0.096 and the p -value is 0.005. P -value is lower than 0.05 so, the impact of the political slogan of PML (N) on politicians and citizens is positive and significant. Therefore, this hypothesis is also accepted.

The value of β is 0.064 and the value of p is 0.010; this shows that the impact of the political slogan of PPP is significant and positive on politicians' and citizens' relationships. Results state that this hypothesis is also accepted.

H4: The political slogan of PTI has a significant and positive impact on the politicians' and citizens' relationships.

It is also accepted because the values of β and p are 0.158 and 0.004, respectively. It means that the relationship between the political slogan of PTI and the relationship between politicians and citizens is positive and significant.

H5: The political slogan of RP has a significant and positive impact on politicians' and citizens' relationships.

The value of β is −0.026 and the value of p is 0.622; this shows that the impact of the political slogan of PPP is not positive and significant on politicians' and citizens' relationships because the p -value is >0.5. This hypothesis is rejected.

H6: The moderating effect of the political slogan of PML (N) positively moderates the relationship between politicians and citizens.

The results state that this hypothesis should be rejected as β is −0.019.

H7: The moderating effect of the political slogan of PPP positively moderates the relationship between politicians & citizens. It is positive as the value of β is 0.045. This hypothesis is accepted as the value of β is positive.

H8: The moderating effect of the political slogan of PTI positively moderates the relationship between politicians and citizens. Similar to that of H7, this is also positive because the value of β is 0.083. So, this hypothesis is accepted.

H9: The moderating effect of the political slogan of RP positively moderates the relationship between politicians and citizens. This hypothesis is accepted because the value of β is 0.034.

The circle of the dependent variable in Figure 4 illustrates that the influence of variance in the dependent variable is explicated by the independent variable. The values on the arrows illustrate the extent of influence of one variable on the other ( Wong, 2013 ).

Social Media is the most persuasive form of promotion. The data for the current study has been gathered from active social media users. As the results indicate with the values β = 0.597 and p = 0.000, SNS had a significant and positive impact on politicians' and citizens' relationships. Also, the value of T-statistics is quite high (11.969) than the threshold value reiterating the basic research objective of this article that political communication through social networking sites has attracted more citizens to publicly express their opinions and discuss important political matters. SNS remains an easily accessible and popular medium of communication to the political parties and individual politicians to convey their political opinion and ideology in an effective manner. Therefore, H1 is accepted. A number of previous research studies analyzed and studied the role of social media in the modern-day political scenario. Among those, the study by Halpern and Gibbs (2013 , p. 1159–1168) deduced that SNS are directly and indirectly involved in enhancing political debate and participation. The results from this study also coincide with the findings mentioned above.

The moderator in this research study is a political slogan and its impact on the relationship between politicians and citizens is analyzed. Political slogans are deemed as one of the key pillars of political communication, and different political slogans have a different impact on the respective political parties. In this research study, political slogans have four further dimensions i.e., the basic four political parties of Pakistan. The results mentioned in the previous section with the value of β as 0.096, 0.064, 0.158, and p as 0.005, 0.010, and 0.004 indicate that the political slogan of PML (N), PPP, and PTI has a significant and positive impact on the relationship between politicians and citizens. Therefore, H2, H3, and H4 are accepted. The highest value of β is recorded regarding the impact of the political slogan of PTI on the relationship between politicians and citizens. It was mentioned in the background and literature review sections that PTI is the leading political party in Pakistan for effectively utilizing the SNS as a tool for political communication and these results reaffirm that. But the political slogan of RP is found to be insignificant with values of β and p as −0.026 and 0.622, respectively. Therefore, H5 is not accepted. This highlights the fact that the more conservative RPs are lagging behind in the evolving political environment which is seriously harming their ability to connect with the youth of Pakistan. this in turn means the decreasing influence of these RPs in the political scenario of Pakistan.

The moderating impact of Political Slogans of these four fundamental parties was found to be different from the direct impact on the relationship between politicians and citizens. The results depict that political slogans when used on social media moderate the relationship between politicians and citizens. But when the results of these dimensions were measured individually, the outcome was different from the direct impact of the four dimensions. Political slogans of PPP, PTI, and RP were found to have a positive moderating impact with the value of β as 0.045, 0.083, and 0.034. Consequently, H7, H8, and H9 are accepted. It shows that when these three political parties prominently used their respective political slogans on social media, citizens responded more enthusiastically and showed enhanced interest. The most significant moderating impact was noted for PTI. It proves that citizens more actively believe in their political slogan of ending corruption to ensure justice and accountability for all. However, the only political party for which the moderating effect of the political slogan has been found negative is PML (N) ( β = −0.026). Therefore, H6 is not accepted. The reason behind this shift in results is most probably the previous record of the PML (N) as they kept changing their political slogan from time to time. The overwhelming success of PTI's social media campaign and the increasing popularity of its political slogan also played a huge role in this aspect. However, it is pertinent to mention here that PML (N) is still the second largest political party in Pakistan. It is because of the fact that mostly, youth are active on SNS and hence, get affected by the political communication campaigns launched by the political parties. The older generation, which is not actively using the SNS and still relies on traditional communication sources constitute a large portion of their vote bank. Similar studies ( Ahmad et al., 2019 , 1–9; Tareen and Adnan, 2021 , p. 130–138) regarding political communication via social media have been carried out in Pakistan. However, the authors of this study were not able to find any similar study which specifically investigated the moderating impact of political slogans of major political parties in Pakistan.

To achieve research objectives and answer the research questions regarding the impact of social media on politicians' and citizens' relationships through the moderating effect of political slogans, the hypotheses are tested through PLS (SEM). Data for the test of hypotheses was taken from social media users from two cities in Pakistan. The results of this study demonstrate the positive and significant relationship between politicians' and citizens' relationships and the relationship between politics and social media. The results also emphasized the importance of political slogans in establishing a bond with the citizens and encouraging their political participation. H1 regarding the impact of social media on the relationship between politicians and citizens is accepted. Furthermore, H2, H3, and H4 regarding the impact of political slogans of PML (N), PPP, and PTI on the relationship between politicians and citizens, respectively, are accepted, but H5 regarding the impact of the slogan of RP is rejected. Also, H7, H8, and H9 related to the moderating effects of political slogans of PPP, PTI, and RP, respectively were accepted while H6 linked with the moderating effect of the slogan of PML (N) was rejected in light of the results.

The purpose behind carrying out this research is achieved, and it has the ability to add a new research dimension. The use of SNS for election campaigning and political communication is becoming increasingly common worldwide and Pakistan is no different. The rising number of internet users and the large youth population are the factors that reinforce the importance of SNS in future political scenarios in Pakistan. The political parties and politicians who are more active and organized on SNS have better chances of reaching out to citizens in an effective manner. In Pakistan, these types of research should be done because our country needs development in every field. It is essential that politicians do not merely communicate with citizens but also build better relationships with them via trust-building actions. The results further show that trust builds trustworthiness.

Future recommendations

The present research can be further improved and enhanced to give even better results by following these recommendations:

• This research is based on the data collected from two cities. The data collection for future studies can be expanded to more cities or countries for enhancing the understanding of the model.

• The sample size can be increased in the future to obtain more precise results.

• Future studies must also cover data collection from the people who work on social media for the promotion of political activities. It will add a new dimension to this research and can be really helpful in obtaining more realistic results.

• This research has generally covered only the youth; future research must also cover more experienced or seasoned people who have more knowledge about political situations.

• Smart PLS does not work on dimensions; in the future, different software can be used to further improve the results.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SF: conceptualization, writing—original draft, and methodology. SF and DF: data acquisition and formal analysis. LY: supervision. SF, LY, and DF: writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ahmad, K., and Sheikh, K. S. (2013). Social media and youth participatory politics: a study of university students. J. South Asian Stud. 28, 353–360.

Google Scholar

Ahmad, T., Alvi, A., and Ittefaq, M. (2019). The use of social media on political participation among university students: An analysis of survey results from rural pakistan. SAGE Open. 9, 215824401986448. doi: 10.1177/2158244019864484

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alford, J., and O'flynn, J. (2012). Rethinking Public Service Delivery: Managing With External Providers . Macmillan International Higher Education.

Alnsour, M., and Al Faour, H. R. (2020). The influence of customers social media brand community engagement on restaurants visit intentions. J. Int. Food Agribus. Market. 32, 79–95. doi: 10.1080/08974438.2019.1599751

Auvinen, A. M. (2008). “Social media-the new power of political influence,” in Factors Influencing the Adoption of Internet Banking , eds Toivo, S., and Baraghani, S. (Brussels: Center for European Studies).

Bakshy, E., Messing, S., and Adamic, L. A. (2015). Political science. Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science 348, 1130–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1160

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baraghani, S. N. (2008). Factors Influencing the Adoption of Internet Banking .

PubMed Abstract

Blood, R. (2000). Weblogs: A History And Perspective . Available online at: http://www.rebeccablood.net/essays/weblog_history.html (accessed September 07, 2020).

Bode, L. (2016). Political news in the news feed: Learning politics from social media. Mass Commun. Soc. 19, 24–48. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2015.1045149

Bossetta, M. (2018). The digital architectures of social media: Comparing political campaigning on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 U.s. election. J. Mass Commun. Q. 95, 471–496. doi: 10.1177/1077699018763307

Boyd, D. M. (2004). “Friendster and publicly articulated social networking,” in Extended Abstracts of the 2004 Conference on Human Factors and Computing Systems - CHI '04 (New York, NY: ACM Press).

Brink, P. J., and Wood, M. J. (2012). Advanced Design in Nursing Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Burnier, D., Edelman, M., Freeman, J., Hinckley, B., Linenthal, E. T., Neuman, W. R. et al. (1994). Constructing Political Reality: Language, Symbols, and Meaning in Politics. Polit Res Q. 47, 239. doi: 10.2307/448911

Callaghan, K., and Schnell, F. (2005). Framing American Politics . Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Cao, Y., and Havranek, G. (2013). Marketing in Social Media , Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Carlisle, J. E., and Patton, R. C. (2013). Is social media changing how we understand political engagement? An analysis of facebook and the 2008 presidential election. Polit. Res. Q. 66, 883–895. doi: 10.1177/1065912913482758

Choi, S. (2015). The two-step flow of communication in twitter-based public forums. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 33, 696–711. doi: 10.1177/0894439314556599

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16, 297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555

Dann, S., and Dann, S. (2011). E-marketing: theory and application. Macmillan Int. High. Educ . 1–474. doi: 10.1007/978-0-230-36473-8

CrossRef Full Text

Diaz, F., Gamon, M., Hofman, J. M., Kiciman, E., and Rothschild, D. (2016). Online and social media data as an imperfect continuous panel survey. PLoS ONE 11, e0145406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145406

Doucet, M. G. (2002). The Democratic Paradox de Chantal Mouffe, Londres, Verso. Polit. Soc. 21, 140. doi: 10.7202/040311ar

Eijaz, A. (2013). Impact of new media on dynamics of Pakistan politics. J. Polit. Stud. 20, 113–130.

Election Commission of Pakistan (2020). Available online at: http://www.ecp.gov.pk/ (accessed June 5, 2020).

Enli, G. S., and Skogerbø, E. (2013). Personalized campaigns in party-centred politics: twitter and facebook as arenas for political communication. Inf. Commun. Soc. 16, 757–774. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.782330

Enli, G. S., and Thumim, N. (2012). Socializing and self-representation online: exploring facebook. Observatorio . 6:87–105. Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/1646-5954/ERC123483/2012

Evans, J. S. B. T. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59, 255–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629

Facebook Reports First Quarter 2022 Results (2022). Aavailable online at: https://investor.fb.com/investor-news/press-release-details/2022/Meta-Reports-First-Quarter-2022-Results/default.aspx (accessed June 25, 2022).

Fanion, R. (2011). Social media brings benefits to top companies. Central Penn Bus. J. 27, 76–77. doi:10.1108.MIP-04-2013-0056

Fatema, S., Yanbin, L., and Fugui, D. (2020). “Impact of social media on politician/citizens relationship,” in 2020 The 11Th International Conference On E-Business . Beijing.

Fiske, J. (1994). Audiencing: Cultural Practice and Cultural Studies. Handbook of Qualitative Research (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 189–198.

Gayomali, C. (2011). Facebook Introduces ‘Timeline’: The ‘Story’ of Your Life”. Time . Available online at: https://techland.time.com/2011/09/22/facebook-introduces-timeline-the-story-of-your-life/ (accessed June 14, 2022).

Ghauri, P., and Gronhaug, K. (2005). Research Methods in Business Studies .

Ghosh, B. N., and Chopra, P. K. (2002). A Dictionary of Research Methods . Leeds: Wisdom House UK.

Gil de Zúñiga, H., Lewis, S. C., Willard, A., Valenzuela, S., Lee, J. K., and Baresch, B., et al. (2011). Blogging as a journalistic practice: a model linking perception, motivation, and behavior. Journalism 12, 586–606. doi: 10.1177/1464884910388230

Gillespie, T., and Boczkowski, P. J. (2014). Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Goffman, E. (1959). The moral career of the mental patient. Psychiatry 22, 123–142. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1959.11023166

Golbeck, J., Grimes, J. M., and Rogers, A. (2010). Twitter use by the U.s. congress. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol . 61, 1612–1621. doi: 10.1002/asi.21344

Goodrow, C. (2017). You Know What's Cool? A Billion Hours . YouTube. Available online at: https://blog.youtube/news-and-events/you-know-whats-cool-billion-hours/ (accessed June 19, 2022).

Grönroos, C., and Helle, P. (2010). Adopting a service logic in manufacturing: conceptual foundation and metrics for mutual value creation. J. Serv. Manag . 21, 564–590. doi: 10.1108/09564231011079057

Gummerus, J., Liljander, V., Weman, E., and Pihlström, M. (2012). Customer engagement in a Facebook brand community. Manag. Res. Rev. 35, 857–877. doi: 10.1108/01409171211256578

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Market. Theory Pract. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Pieper, T. M., and Ringle, C. M., et al. (2012). The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in strategic management research: a review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long Range Plann. 45, 320–340. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2012.09.008

Hale, J. (2019). More than 500 Hours of Content Are Now Being Uploaded to YouTube Every Minute.” Tubefilter. Available online at: https://www.tubefilter.com/2019/05/07/number-hours-video-uploaded-to-youtube-per-minute/ (accessed June 17, 2022).

Halpern, D., and Gibbs, J. (2013). Social media as a catalyst for online deliberation? Exploring the affordances of Facebook and YouTube for political expression. Comp. Hum. Behav. 29, 1159–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.008