University Library

Guides to Sources on Russian History and Historiography

- Collections

- Slavic Reference Service

- Research Resources

- Visiting Scholars

- Events and News

All of the general bibliographic guides for Russia and those for the Slavic world in general will be important for historical research. If you have not consulted them, it is wise to examine them before looking at the guides for specific disciplines.

Guides for historical materials are varied in scope and focus. Many will include information on archives, particularly on guides to the historiographic literature. Others will contain lists of history periodicals and their indexes. Biographical and genealogical sources are frequently included in historical bibliographies, as are sources on heraldry and archives. Other sources for historical research include chronologies, historical atlases, dictionaries of terminology, and subject encyclopedias. Biographies of historians are also to be found in a variety of specialized resources many of which are listed in the section below on Russian historical biography . Emigre resources are treated in a separate section as are the materials for Russian literature . Both of these are areas of great importance for historians. Those seeking material specific to the fine arts will find them in the section on Russian arts .

This list will provide examples of all of these sources but will emphasize the bibliographic materials, as these are still basic to all historical research. Frequently, the other sources mentioned above can be identified using a good bibliographic source. The purpose of this section is not to list every historical resource available; the list is by no means comprehensive. Rather, the goal is to list sources that can act as finding aids for historical research and to make the scholar aware of the range of sources available. Frequently, older published sources will be included. This is because they contain the best annotations and clearest listings of historical resources. When possible, online sources are included. Those electronic resources that are included will act as “portals” to other resources on specific historical topics.

Bibliography of Bibliographies and Historiographical Bibliographies

Bibliografiia russkoi bibliografii po istorii sssr. annotirovannyi perechen bibliograficheskikh ukazateli izdannykh do 1917..

Moskva: Izd-vo. Vsesoiuznoi knizhnoi knizhnoi palaty, 1957. 197p. U of I Library Call Number: Russian Reference 016.947M85b

This is a superbly annotated guide to bibliographies on Russian history published up to 1917. This project was a joint effort of the State Historical Library (Moscow) and the Russian National Library (Petersburg ): State Historical Library (Moscow) compiled the section on the history of the SSSR; the Russian National Library (Petersburg) wrote the sections on general history. Along with historical bibliographies, this bibliography includes bibliographies of publications of societies and organizations, indices of historical journals, and lists of works by Russian historians. Individual entries for historians often include biographical materials as well as bibliography. The volume concludes with an author/title and a general name index. This guide is the best place to start a search for bibliographies on any historical subject before 1917.

Istoriia SSSR. Annotirovannyi perechen russkikh bibliografii izdannykh do 1965 g

Moskva: Izd-vo. ‘Kniga,’ 1966. 427p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) and Main Stacks 016.947M85B 1966

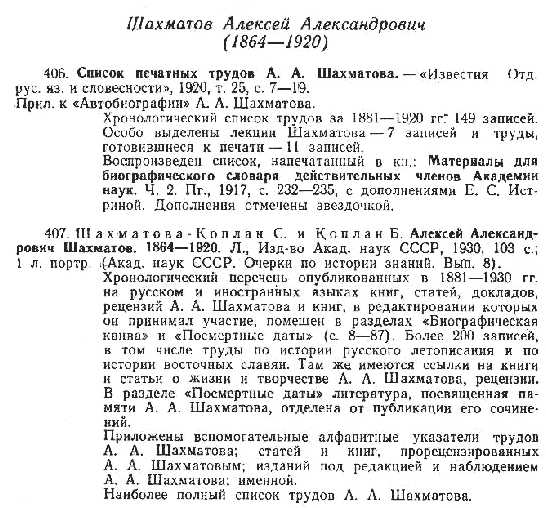

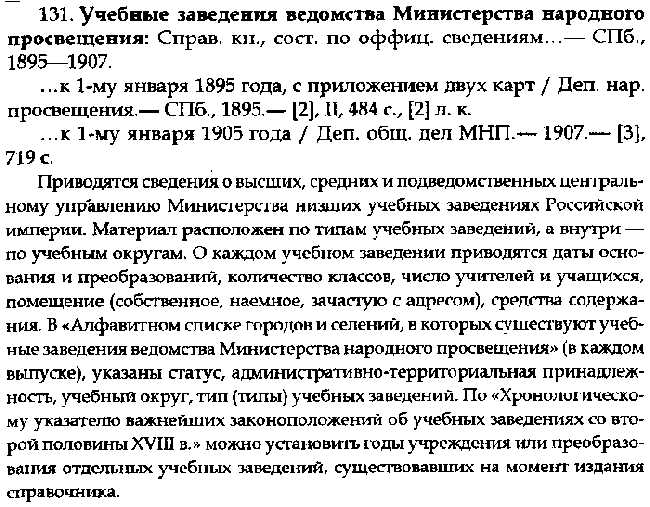

This is a continuation of the work listed above, compiled in a joint effort by the Russian State Library (Moscow) and the State Historical Library (Moscow) . Each item is described in detailed annotations. Materials included are monographs, articles in books and periodicals, and journal indexes, and are divided into four sections: I. General Works; II. Bibliographies on the history of the USSR up to 1861; III. History of the USSR from 1861-1917; IV History of the USSR during the socialist period and the construction of communism. The volume includes bibliographies of historiography, of memoir literature, of individuals, and of histories of various republics of the USSR (Ukraine, Central Asia, etc.) The lengthy section devoted to biobibliographical works perhaps deserves special attention as it lists bibliographies of works by Russian/Soviet historians and works about them. Since entries are well annotated, the scholar will have a clear picture of the scope of each work cited as can be seen in the entries below reproduced from p. 164 of the bibliography.

The work does not include bibliographies of dissertations or manuscript materials. The volume is by subject in general, but an index of authors and titles and a general name index make it easy to find specific bibliographies. This is an excellent place to begin historical research, particularly on the early Soviet period.

Guide to Russian Reference Books. Vol. II: History, Auxiliary Historical Sciences, Ethnography, and Geography.

Maichel, Karel. Edited by J.S.G. Simmons. Stanford: Hoover Institution, 1964. 297p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic), History, Philosophy, & Newspaper, Main Stacks, and Oak Street Facility 016.9147 M24g V. 2

The purpose of this work is to bring together in one annotated volume all of the “substantial” bibliographic and reference tools relating to Russian history. Maichel compiled this list based on the major Slavic collections in the U.S., so that scholars would know that such sources exist outside of Russia. Sections include Russian history, World history, Auxiliary historical sciences, Ethnography and Geography. The editor has included works published through 1963.By and large Maichel has selected bibliographies for this volume, but biographical and terminological dictionaries, encyclopedias, gazetteers, chronologies, atlases, and handbooks can also be found here. Sources are, for the most part, in Russian, English, French and German. A cumulative author, title, and subject index rounds out the book.

Istoriia istoricheskoi nauki v SSSR. Dooktiabrskii period. Bibliografiia.

Moskva: Nauka, 1965. 703p. U of I Library Call Number: Main Stacks and Oak Street Facility 016.947 M85IST

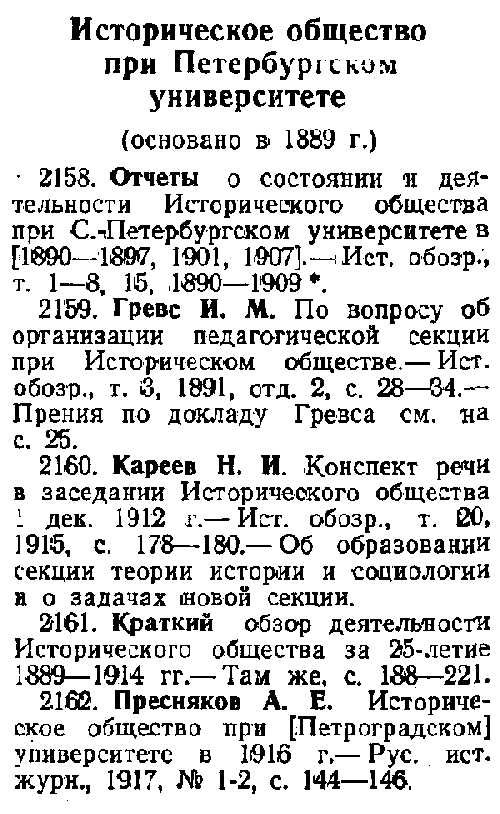

This bibliography covers the historiography of Russia up to 1917. Citations are to books, articles in journals, sborniki , newspapers, and dissertations published up to 1963. All kinds of historical study are included, although Church history is covered very selectively. The bibliography itself is divided into three parts: General works, Literature on the work of historical societies and groups, and Literature on individual historians.

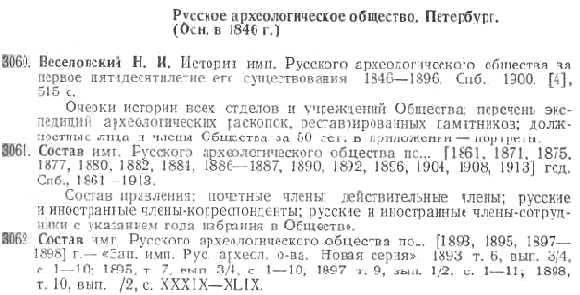

Entries provide full bibliographic information but are not annotated. However, the compilers frequently supply information on the topic, society or individual that is the subject of the section. So, for example, in the section on the Russkoe arkheologichesko obshchestvo there is basic information on the founding of the society.

The bibliography covers historians who emigrated, but works published in emigration are not included. The compilers used numerous collections for their citations, including GPIB, the Lenin Library, and the Saltykov-Shchedrin Library. Other citations were taken from the massive bibliographies of Mezhov and Lambin . Entries are not annotated, but the contents for some sborniki and multi-volume works are listed. The work concludes with a cumulative name/title index.

Istoriia istoricheskoi nauki v SSSR. Sovetskii period. Oktiabr’ 1917-1967. Bibliografiia.

Moskva: Nauka, 1980.733 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 016.9470072 IS769

This is a continuation of the bibliography listed above, covering historiography from 1917 to 1967. It was compiled by GPIB in cooperation with the various institutes of history of the Academy of Sciences and regional affiliates. An enormous number of sources were consulted for the compilation of this bibliography, including the collections of the GPIB, the Lenin Library, and the Saltykov-Shchedrin Library, as well as bibliographic publications such as the INION historical bulletins. Most of the items cited are in Russian, but some citations are to works in languages of the other republics of the USSR.

The volume is divided into two parts. Part one covers general topics. Each chapter of the bibliography is devoted to some area of historiography, from the historiography of world history to the historiography of the history of feudal Russia. The second part is devoted to the activities of scholarly organizations and historical societies. Here can be found information on the publications and history of individual institutions.

An index of authors, editors, compilers, and titles of sborniki and periodicals provides easy access to individual works.

Bibliografiia bibliografii na sovremennom etape. Sbornik statei i bibliograficheskikh materialov.

Sankt-Peterburg, Rossiiskaia natsionalnaia biblioteka, 1995. 146 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 011.00947 B471

This book contains a series of bibliographical essays on the history of bibliography in Russia. The most useful section for historians is the chapter, “Novye ukazateli, issledovaniia i obzory bibliographicheskikh posobii i spravochnykh izdanii, opublikovanye v 1987-1993 gg.” Many of these bibliographies are historical in nature, and this publication currently serves to cover the most recent years of Russian bibliographies. While the volume has a brief table of contents, there are no indices.

Historical Bibliographies, Catalogs, and Guides to Research

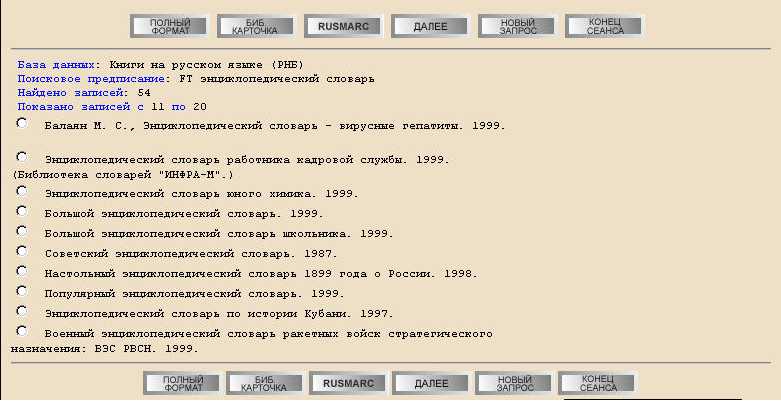

General’nyi alfavitnyi katalog knig na russkom iazyke (1725-1998).

URL: http://nlr.ru/e-case3/sc2.php/web_gak

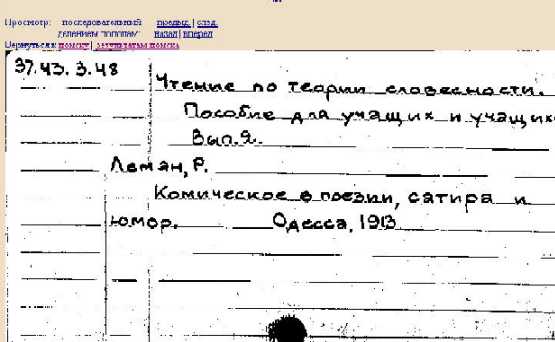

This scanned copy of the card catalog of the Russian National Library is an invaluable tool for anyone planning a trip to St. Petersburg or trying to verify a specific title. It does require a bit of patience. As with the scanned catalogs of the Jagiellonian University Library or the Czech National Library , access is by “main entry,” i.e. cards are filed by author or corporate author. There is no subject access. In order to search this catalog , the user will enter a term on the search screen. The result returned will be a list of possible entry points for the catalog, rather like the tabs on index cards. Selecting one of these will position the user in a range of cards. The user must select the cards, by number and essentially “browse” the cards. Below is a sample entry from the catalog.

The catalog includes citations to periodicals, dissertations, and maps as well as monographic works. The precise holdings for periodicals are not included in this version of the catalog. However, the microfiche edition contains a supplement of periodical titles and holdings for the Russian National Library.

Russkaia kniga grazhdanskoi pechati XVIII v. v fondakh bibliotek RF (1708-1800)

URL: http://www.nlr.ru/rlin/ruslbr_v2.php?database=RLINXVIII

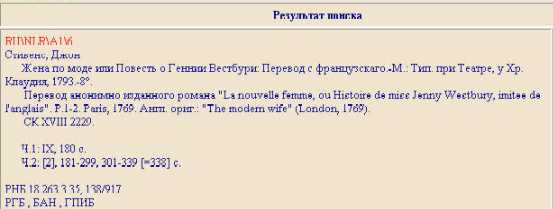

This catalog lists the holdings of eighteenth century Russian books in the libraries of the Russian Federation, specifically the State Historical Library (GPIB), the Russian National Library, the Russian State Library, the library of the Academy of Sciences (BAN) and the library at Moscow State University. The records are fully searchable. It is possible to search not only by title or name, but also by organization, years of publication, place of publication, country of publication and language. The latter seems somewhat peculiar given that this is a database of Russian language publications. This search allows you to identify those items that have been translated.

As can be seen from this example, holdings at several institutions are listed, as is full bibliographic information. This is a particularly valuable resource for those planning to travel to Russia.

Spravochniki po istorii dorevoliutsionnoi Rossii. Bibliograficheskii ukazatel’

Zaionchkovskii, P.A. . 2 nd ed. Moskva: Kniga, 1978. 640 p. U of I Library Call Number: Russian Reference 016.947 Sp76 1978

This excellent bibliography covers historical material on the history of Russia from the 15 th century to February 1917 and is an excellent source of information on government publications of all kinds: laws, censuses, ministry publications, statistical data, etc.. The first section covers general reference works such as encyclopedias, dictionaries, atlases, necrologies, and archival guides. The rest of the guide is divided into broad subject areas and then subdivided into specific topics that are outlined in the table of contents. The broad subject headings are Social and Economic Affairs, Political Affairs, Military Affairs, Sociopolitical Movements in the 19 th and 20 th c., Science and Education, and Regional Administrative Affairs. Most entries are annotated. Zaionchkovskii used the collections of several libraries, including GPIB , the Ermitazh library , and the catalog of the Tsentralnyi gosudarstvennyi arkhiv drevnikh aktov for material before the 18 th c. Works on archaeology and ethnography are not included, nor are works related to the history of literature, art, museum studies, or bibliography. However, publications with the activities and membership of societies devoted to these subjects are listed.

This entry gives a good idea of the kind of information one can expect to find in Zaionchkovskii. For those looking for information on the membership of a certain organization, academic institution, military unit or government agency, Zaionchkovskii will provide the most complete list of resources. The types of sources are quite different from those you will find on the same topic in a source like Istoriia SSSR.

A general index of subjects, governmental bodies, organizations, and institutions concludes the book and aids in locating materials on very specific topics.

Dorevoliutsionnye izdaniia po istorii SSSR v inostrannom fonde Gos. Publichnoi Biblioteki im. M. E. Saltykova-Shchedrina. Vyp. 1- .

St.Peterburg:Izdatel’stvo Rossiiskoi natsional’noi biblioteki, 1964- U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 016.947 G699d v.3-5

Each volume of this bibliography focuses on a different topic or time period in Russian history, as viewed by Western historians. The first volume, published in 1964 is devoted to general works on Russian history up to the 18th century. The second volume was devoted to works on education in the early Russian empire. Volume three is a compilation of foreign works on the Russian nobility. Volume four focuses on the Napoleonic wars and volume five, published in 2001 is devoted to the reign of Alexander I. All titles included here were published before the revolution. All items cited are in the Russian National Library and provide a view of how the West viewed Russia. The most recent volumes are well indexed including an author and title index.

Istochniki po istorii naselennykh punktov dorevoliutsionnoi Rossii.

Vypusk 1. Pechatnye istochniki perioda Rossiiskoi Imperii (1721-1917 gg.) Sbornik bibliograficheskikh materialov. Sankt-Peterburg: Rossiiskaia Natsional’naia Biblioteka , 1996- U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 016.30770947 IS7 V.1-

This is an unusual resource on the populated places of prerevolutionary Russia. The book contains four bibliographic essays. The first, entitled “ Pechatnye istochniki po istorii naselennykh punktov Rossiiskoi imperii (1721-1917 gg.), ” lists all the sources that will be described in detail in the succeeding essays. It is primarily a list of 139 sources that are used throughout the rest of the volume. Many of these titles were multivolume sets that until this publication were very difficult to use. The compilers of this volume have analyzed the contents of these sets and organized them in the context of their relation to each inhabited place in Russia in the 19th century. So, for example, the basic publication information on the set Gorodskoe poseleniia v Rossiiskoi Imperii is listed in the first essay under the title. In second essay there is a listing of every town that appears in that volume, with a volume and page reference to the entry.

The second essay is entitled “ Alfavitnyi ukazatel naselennykh punktov, opisannykh v izdaniiakh: ‘Gorodskie poseleniia v Rossiiskoi imperii,’ ‘Voenno-statisticheskoe obozrenie Rossiiskoi imperii’ i ‘Materialy dlia geografii i statistiki Rossii, sobrannye ofitserami General’nogo shtaba. ‘” This is followed by “ Vidy gorodov i drugikh naselennykh punktov i izdanii ‘Zhivopisnaia Rossiia’. (Ukazatel illiustratsii). ” The volume closes with “ Kartograficheskie istochniki po istorii otdel’nykh mestnostei i naselennykh punktov Rossiiskoi imperii.”

As can be seen from the chapter titles, this is more than an index of a few titles on population or simply a bibliography of publications on that subject. This is a volume that can be used to locate regional maps or illustrations as well as statistical data. The first section includes a subject index for the main list of entries. Each section also includes an introduction by the compiler.

Svodnyi katalog Russkoi nelegal’noi i zapreshchennoi pechati XIX veka . V.1-9.

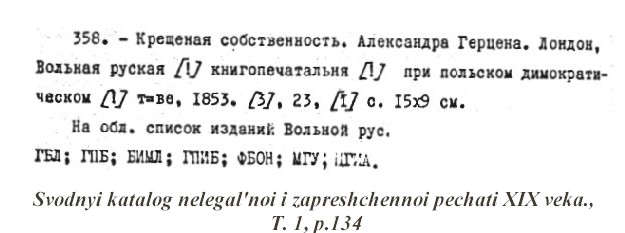

U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference 015.47 Sv512 V.1-9

This unique bibliography provides a detailed record of all illegal publications of the 19th century. The first six volumes are arranged alphabetically by main entry, usually the author. Where no author is listed the works are listed by title. Volume seven is a chronological index. Volume eight includes an index of organizations, intellectual circles, illegal publishers and a name index. Each entry is very thorough providing complete citation information.One of the features of the citations is the inclusion of location information. Most citations also include reference to published references to the work. A list of all the references and a supplement to the other volumes make up the content of volume nine.

Ekaterina II: Annotirovannaia bibliografiia publikatsii.

Babich, I. V., Moskva: “Rossiiskaia politicheskaia entsiklopediia” (ROSSPEN), 2004. 928 pp. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 947.06 C28Wba

This extensive work lists the Russian publications of Catherine the Great issued through 1998. Each entry in annotated in detail and divided into several parts that indicate the chronological period of the publication, its content, supplementary materials.

Russkaia istoricheskaia bibliografiia: Ukazatel’ knig i statei po russkoi i vseobshchei istorii i vspomogatel’nym naukam za 1800-1854 .

Mezhov, V.I. St. Peterburg, 1892-93. 3 vols. vol. 1: xvi +373p., vol. 2: vii + 377 p. vol. 3: x +514 p. U of I Library Call Number: Russian Reference 016.947 M57ru 1974 HathiTrust full-text link: vol. 1 http://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433033574066 vol. 2 http://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433033574074 vol. 3 http://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433033574058

This bibliography contains references to books, book reviews, articles in journals, newspapers, gubernskiia vedomosti , sborniki , almanakhi, and kalendari on history and related subjects that were published in Russian from 1850-1854. The compilation was based on the collection of the Russian National Library , where Mezhov worked, and it was originally intended to be six volumes, but only three were published because of Mezhov’s death. The citations created for the final three volumes are on cards currently housed in Pushkinskii Dom, the Institut Russkoi Literatury of the Russkiia Akademiia Nauk in Petersburg. Unfortunately, there are no indexes, but the table of contents of each volume is extensive and arranged by subject. The section on biographical sources in the second volume is arranged by the name of the subject, not the author of the work.

Russkaia istoricheskaia bibliografiia. God 1855-1864 .

Lambin, P.P., and B. P. Lambin ., St. Petersburg: Imperatorskaia akademiia nauk, 1861-1864. 10 vols. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) and Oak Street Facility 016.947 L17R. History, Philosophy, & Newspaper FILM 016.947 L17R HathiTrust full-text links: vols. 1-4 http://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433033567789 vols. 5-7 http://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433033567797 vols. 8-9 http://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433033567805

This annual bibliography provides very broad coverage of all historical works published in Russian for each year, including books, periodical publications, articles and reviews in books and newspapers, and maps. Each volume is divided into broad sections: Russian history, General history, and Articles in periodical publications. History here, and in Mezhov’s 10 volume work, is defined in its broadest sense to include the history of education, literature, religion and other topics. It often seems that the compiler included material judged to have historical significance, as well as those writings that would be called strictly historical in nature. The bibliographies were compiled on the basis of the collection of the library of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. Each volume has a name index and a geographic/subject index. An index of periodical publications appears with the 1856 volume.

Russkaia istoricheskaia bibliografiia za 1865-1876.

Mezhov, V. I. S-Petersburg, Tip. Imp. Akademiia Nauk, 1882-1890. 8 vols. U of I Library Call Number: Russian Reference 016.947 M57R 1974 HathiTrust full text: vols. 1-2 http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3452315 vols. 3-4 http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3452316 vols. 5-6 http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3452317 vols. 7-8 http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3452318

This 8 volume compilation was created to continue the work of the Lambins . The bibliographical citations make up the first six volumes and cover books, book reviews, journal and newspaper articles on Russian and general history in Russian and Russian history in west European languages. Mezhov used the collection of what is now the Russian National Library as well as bibliographies of new books in Knizhnyi vestnik , Knizhnye novosti and the newspaper Pravitel’stvennyi vestnik . Brief annotations are given for some works, and multivolume works or sborniki are listed with their tables of contents. Volumes 1-5 cover Russian historical and auxiliary sciences such as geography, ethnography, statistics, and law. Volume 6 covers general world history in Russian. Volumes 7 and 8 are the indexes to the first six volumes: a mammoth combined index of authors and subjects, including both personal names and geographic names as subjects. A separate index of books and articles in foreign languages is included, as is an index to the tables of contents of all six volumes.

Obzor zapisok, dnevnikov, vospominanii, pisem i puteshestvii, otnosiashchikhsia k istorii Rossii i napechatanykh na russkom iazyke. Vyp. 1-5.

Mintslov, S. P. Novgorod: Guber. Tipografiia, 1911-1912. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 016.947 M66O HathiTrust full-text link: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015034585722

Mintslov’s annotated index of Russian and foreign sources published in Russia and abroad in books, journals and newspapers has a somewhat unusual arrangement. Items chronologically span the period of the eighteenth century through 1887 (articles) and 1907 (books). The sections cover three chronological periods: Ancient times to Paul I; The Time of Alexander I and Nicholas I; The time of Alexander II and Nicholas II. Each chronological section has an index of author and subject names. This was one of the first comprehensive compilations of memoir and travel literature. Entries often include reviews and literature about the authors. Thus, while the number of items listed in the bibliography is 4,791, it includes references to a far greater number of publications.

This bibliography was continued serially in 1915. The June, July and August 1915 issues of Russkaia Starina (IU call number: Main Stax 947.005 RUSK) include what was to be Mintslov’s final installment of the bibliography. These articles covered materials published after 1907.

Katalog: Russkie ofitsialnye i vedomstvennye izdaniia XIX – nachala XX. T.I-.

Sankt-Peterburg: Blits. 1995- U of I Library Call Number : International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) and Oak Street Facility 025.3434 K155 V.1-6

This is a catalog of the official and departmental publications held in the reference library of the Russian State Historical Archive . The catalog is organized by governmental body. Thus the first volume includes references to the publications of the Duma, the State Senate and the Holy Synod. Entries are brief, but provide full bibliographical information for each title. The next seven projected volumes will include the publications of government ministries. The remaining volumes will focus on “extra-ministerial” publications. This is a valuable new source for anyone doing research on Imperial Russia and planning research in the Russian Federation. The publications of specific bodies can be easily identified and tracked. This multi-volume bibliography is projected to be 10 volumes when complete. Already 5 of those volumes are available. Some of the later volumes may be the most interesting as they are to include the publications of all “extra-ministerial, social, scientific, cultural and popular institutions” (p.12). The only difficulty in using this set is that they do not have individual indexes.

Istoriia SSSR. Materialy dlia bibliografii inostrannoi bibliografii (1699-1991 gg.)

Mamontov, M. A. and V. V. Antonov. St. Peterburg: Rossiiskaia natsionalnaia biblioteka, 1997. 392 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) and Oak Street Facility 016.947 M311i

Over 3,000 works are included in this source tracing the history of Russia as it was written in other courntries. It is a very thorough compilation of bibliographical materials listing some Western sources that date from the 18th century. As with many of its Russian counterparts, this guide includes indexes of journals and biographical materials on Western historians. It also includes references to some archival sources, such as Grimsted’s invaluable guides on the subject. The entries provide full bibliographic information, but rarely are annotated. Some include the contents of the publication.

While this is an excellent source to research Western studies on Russia, it does have some peculiar gaps. For example, The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History (MERSH) is not included here. On the other hand, one of the more useful inclusions in this source is the list of indexes of history periodicals. There are several indexes: a name index, heading index, and a series index. The volume includes two supplements. The first lists publications on the history of Russian property in America. The second lists publications on the history of the Bialystok area.

This guide also brings many of the earlier publications up to date. It lists in one source the published Western bibliographical resources on Russian history issued up to 1991. This fact alone makes this a valuable resource for the student of Russian history.

Istoriia SSSR. Ukazatel knig i statei, vyshedshikh v 1872-1917 gg.

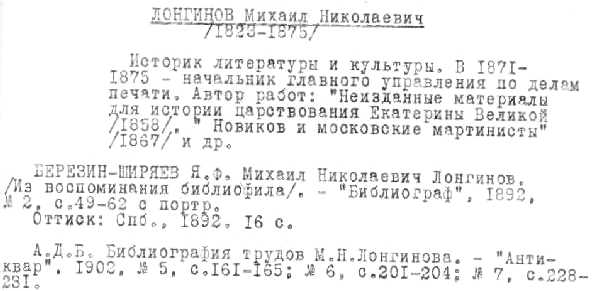

Moskva: GPIB, 1957. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) and Main Stacks Q. 016.947 M85IS

This volume was the first in a series of bibliographies planned to cover historical scholarship for the years prior to 1917 that were not covered by Mezhov and Lambin. It covers scholarship on historians and historiography written during the period 1872-1917. It is divided into two main sections: first, general works on historiography; then a larger section of literature on individual historians. The latter section is divided further into chronological periods. Historians are listed alphabetically within time periods.

Some entries are annotated, and brief biographical information is given for many historians. This guide concludes with a useful chapter on biographical and biobibliographical dictionaries that lists the persons covered within each book. A general name index is provided as well.

Pervaia Mirovaia Voina. Ukazatel’ literatury 1914-1993 gg.

Moskva: Rossiiskaia Akademiia Nauk, 1994. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 016.940347 P435

This slim volume lists the holdings of the Social Sciences Library of the Academy of Sciences on World War I. The citations are arranged chronologically and include books and pamphlets on the topic. The volume has an author index. It is included here as it is one of the few bibliographies on the subject of World War I. Its arrangement provides the scholar with a view of the development of the study of this period both before and after the Revolution.

Historical Encyclopedias

There are numerous single-volume encyclopedias that are of interest to scholars. Many are highly specialized. New publications can best be identified by checking an online library catalog, or by searching such sources as ABSEES or the Russian National or State Library catalogs . There are several online sites of interest to those seeking historical information. One that combines the resources of historical encyclopedias and dictionaries is www.rubricon.com (see below).

General historical encyclopedias:

Otechestvennaia istoriia. istoriia rossii s drevneishikh vremen do 1917 goda..

Moskva: “Bol’shaia Rossiiskaia Entsiklopediia, 1994- . Tom 1- . U of I Library Call Number: Main Stacks 037.1 Ot2 v.1-3

This new historical encyclopedia reflects the changes in the study of Russian history since the downfall of the Soviet government. Many emigre figures who would never have been included in a Soviet publication can be found here, discussed in detail. All of the entries are substantial, are signed and include bibliographies. (For an example from the encyclopedia, click on the picture of the Dmitrii “The Pretender” on the left). History is defined broadly here and there are entries on topics of interest to those researching the history of education, art, law and many other subjects. There are many illustrations in the volume.

The compilers note that they hav consulted archival materials and standard sources in the production of this source. Anyone seeking historical information on religion, economics, culture, diplomacy, military history or biography will find this a rich source.

Follow the link for an entry from Otechestvennaia istoriia.

Sovetskaia istoricheskaia entsiklopediia.

Moskva: Izdatel’stvo “Sovetskaia Entsiklopediia”, 1961-1976. U of I Library Call Number: Main Stacks and Oak Street Facility 903 So89 v.1-16

This encyclopedia covers historical topics on all areas of the world. It is, of course, told from the Soviet point of view. If the reader is aware of how this will affect the interpretation in the encyclopedia, it is still a valuable resource. There are numerous historical and ethnographic maps. All articles include a bibliography and are signed.

The articles are scholarly and intended for the serious student of history. The arrangement is standard alphabetical, with each volume adding a list of abbreviations and maps. It is a useful biographical source, again with the scholar always keeping in mind the restrictions imposed by censorship that affect the content and choice of entries.

Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History.

Gulf Breeze, FL:Academic International Press. 19 U of I Library Call Number : International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 947.003 M72 v.1-61, Supplement v.1-

This encyclopedia is suited to a broad audience with its English language entries and extensive bibliographies. The volumes cover a wide range of historical topics from culture to government to the press. All articles are signed. This is an invaluable resource for the student, with information on thousands of topics. It is also a helpful tool for the scholar, providing basic information and bibliography on so many subjects. The volumes are arranged alphabetically. There are indexes of entries by authors and by time periods. It has many uses, not least of which is as a biographical source. The entries all include general information on the topic, placing it in historical context. All entries are signed. This gives the student the opportunity to pursue other materials by the author. is also an online index of each volume available at the publisher’s site . Supplementary volumes have begun to appear. The supplement has, so far, only reached the letter “A.”

Top of Page

Rubricon.ru

URL: www.rubricon.com

There are a number of sites on the world wide web that combine the resources of many encyclopedias, making several resources searchable at the same time. This site attempts to accomplish this for a number of encyclopedias and encyclopedic dictionaries. Among the sources that are searched are Dal’s Tol’kovyi Slovar’ , the Bol’shaia Sovetskaia Entsiklopediia, the Brokgauz and Efron encyclopedia, an historical dictionary Istoriia Otechestva , and the encyclopedias of Moscow and St. Petersburg. Clearly, this is a very useful source for ready reference. The searches will retrieve all articles in which the search term appears.

The one flaw in the material here is the lack of any illustrative materials in many of the sources. Tables and illustrations are completely absent from the Brokgauz Encyclopedia . The Illiustrirovannyi Slovar’ contained illustrations and there were maps and some charts for the Istoriia Otechestva . However, in general, there were very few graphic materials in this database. Nevertheless, the ability to search so many sources in one place, by entering one term is very useful.

Information on each of the sources is supplied at the site. If the user clicks on the name of the encyclopedia, supporting information on the source will appear.

Subject historical encyclopedias:

Putevoditel’ po nauchnym obshchestvam rossii..

Komarova, I. I. New York: Norman Ross Publishing, 2000. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) Q.067 P982

The brief citation above hardly does justice to this wonderful reference tool. This source lists some 530 societies of the prerevolutionary period. The guide is the result of twenty five years of research. It not only lists the societies and basic information about them, it serves as an index to the contents of their publications. Each entry includes the name of the society, its charge, activities, and publications, and cites literature about it. In those cases where the contents of the publications of a society are listed in a separate publication, the compiler has indicated where the contents can be found. So, for example, Komarova cites the Sbornik Istoriko-filologicheskogo obshchestva pri Kharkovskom universitete, and rather than listing the contents, she notes that they are listed in Sistematicheskii ukazatel’ k periodicheskim izdaniam istoriko-filologicheskogo obshchestva pri Kharkovskom universitete (1953).

The volume is arranged alphabetically by the name of each society. There are a number of useful indexes including a chronological index of societies, a geographical index, an index of names, and an alphabetical index of periodical publications. The compiler has included references to publications that did not survive the turbulent years of the Revolution using other indexes to identify this information. The disadvantage of not having examined the works de visu is outweighed by the historical importance of presenting a complete picture of the history of Russia’s learned societies.

An ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires.

Olsen, James, S. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1994. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 305.800947 Et38

Politicheskie partii Rossii konets XIX – pervaia tret’ XX veka. entsiklopediia.

Moskva: “Rosspen,” 1996. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference 324.24703 P759

This is an excellent source for anyone interested in the political movements in Russian in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There are entries on political parties, their publications, and major figures in political movements. The entries are extensive with bibliographies and archival references. The volume includes eight supplements: a list of all political parties, the leaders of “Russkii narod”; the members of the “Soiuz” in 1917; members of the central committee of the “Partiia Progressistov”; members of the central committee of the “Konstitutsionno-demokraticheskaia Partiia”; members of the central committee of the “Partiia Sotsialistov-Revoliutsionerov” party; the governing body of the “Sotsial-Demokratia”party; and a list of all periodical publications of the political parties in Russia in 1917.

Entries are quite extensive providing a brief history of each of the parties, its development and liquidation. The biographical entries are also quite lengthy. The volume includes numerous photographs of major political figures of the period.

Grazhdanskaia voina i voennaia interventsiia v SSSR. Entsiklopediia.

Moskva: “Sovetskaia Entsiklopediia,” 1983. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 947.0841 G7952 1983

This source can serve as an introduction to the events of World War I in Russia. The articles are brief and do not include bibliographies. However, there are some useful features. For example, the entries on various divisions of the army end with a list of the commanding officers. The bibliographic sources listed at the end of the volume are also useful. The encyclopedia fully reflects a Soviet view of the war.

The Blackwell encyclopedia of the Russian Revolution.

Shukman, Harold. New York: Blackwell Ltd., 1988. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) and Main Stacks 947.0841 B568

“The purpose of this Encyclopedia is to describe and analyze the events of 1917 in Russia, as well as their background and origin, and to show how they affected the political, economic, social and ethnic structures of the old empire and gave rise to the new order.”(p. vii). This reference source limits itself to just those structures and events that played a role in the Revolution. The arrangement is somewhat unusual. The compiler has arranged the entries in chronological order to limit the amount of duplication that would exist in a more traditionally ordered encyclopedia. The articles are listed in a detailed table of contents and the volume includes an equally detailed index. While most entries are intended to be self-contained, cross-referencing has been indicated with small capitals in the text. A special biographical section makes up the last 100 pages of the volume. Bibliographic references are in Russian and English.

Regional Encyclopedias

Sankt-peterburg, petrograd, leningrad: entsiklopedicheskii spravochnik..

Moskva: Nauchnoe izdatel’stvo “Bol’shaia Rossiiskaia Entsiklopediia”, 1992. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 947.453003 Sa 58

While this encyclopedia is directed at the general reader, it contains an enormous amount of historical and statistical data on one of Russia’s most important cities. Included in its pages are articles on many of the cities most important historical figures, publications, literary circles, archives, places and events. Most articles include bibliographies of the major works on a topic. There are numerous illustrations and maps, many quite specialized. It is possible to find a map of the the art and historical museums of the city and one of the armed camps of the Petrograd uprising of 1917. Basic architectural information is also readily available in this volume. The encyclopedia begins with a lengthy overview of the city’s history and natural environment, artistic and literary history and a separate bibliography on each topic.

Moskva: Entsiklopediia.

Shmidt, S. O. (ed.). Moskva:”Bol’shaia Rossiiskaia Entsiklopediia”, 1997. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 914.73103 M8532

Like Sankt-Peterburg, Petrograd, Leningrad , this volume is directed at a wide group of readers. It does contain a great deal of general information, but also an equal amount of more specialized detail about the city’s history and art. Beginning with a general essay on the city, the volume shares a similar structure with the Petersburg volume. However, it includes an index of topics covered in the volume and a list of scientific institutes in the city. Article are all signed and include basic bibliography. A very broad range of subjects are covered. Anyone seeking information on the history of a street, building or a biography of a major figure in the city’s history will find this volume valuable. Journals, newspapers, educational institutions, churches, historical events are all included here. Statistical data on the population of the city is available in the introductory essay.

Tri Veka Sankt-Peterburga Entsiklopediia v Trekh Tomakh. Os’mnadtsatoe Stoletie. Tom1, Kn.1-2.

Sankt-Peterburg: Filologicheskii fakul’tet Sankt-Peterburgskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta, 2001.

Tri Veka Sankt-Peterburga Entsiklopediia v Trekh Tomakh. Deviatnadtsatyi Vek. Tom 2, Kn 1- .

U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 914.721003 T73 V.1:1-2:6

The editors of this source have set themselves the task of tracing the history of culture in one of Russia’s greatest cultural centers. The first two books cover the eighteenth century. More than 200 authors have contributed articles to these volumes on the scholarly institutions, libraries, and museums of St. Petersburg and its suburbs. The formal criteria for the articles included exact dates of birth and death for essays on individuals, dates given in old style for Russian figures. Articles were to include an essay, works, primary sources, and secondary literature on the subject. The inclusion of references to primary source material make this a valuable aid in identifying archival locations for materials. The entry shown at the left is taken from Volume I, Book II, p. 550 and is a very brief entry on an individual. Most of the entries are quite substantial. The entry does exemplify the type of biographical data that are supplied and the archival information available within the pages of this source. There are also entries in these volumes on all that was relevant to the history and development of the city: the stock market, typographers, cartography, classicism, etc.

The first volume includes some excellent color maps. The second volume has a section of color plates with excellent reproductions of early city plans that provide an interesting view of the city’s development through the century. There are many black and white illustrations throughout the volume. There is also s lengthy section of supplementary material with tables listing the city officials, a chronological hsitory of the Winter Palace from 1708-1730, a table on the icnography of the tsars, the hydrography of St. Petersburg, meteogology of St. Petersburg, to name but a few of the titles of the nineteen supplements. The first volume on the nineteenth century has only recently appeared and should be an invaluable resource for scholars interested in St.Peterburg’s history.

Volume II is devoted to the nineteenth century and is structured like Volume I. The entries have the same wealth of information and bibliographic detail as the previous volumes. Like the earlier volumes, a section of color reproductions of city maps and illustrations is included. Archival references are also included in many of the entries.

Ural’skaia istoricheskaia entsiklopediia.

Ekaterinburg: UrO RAN, 1998. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) Q. 947.43003 Ur11

This volume like those on Petersburg and Moscow, provides a wealth of information for anyone interested in the Urals. It’s arrangement is somewhat different from the other volumes, as there is no overview of the region and no index. Nevertheless, for anyone with a specific question or name to investigate that relates to the region, this is a very useful source. All articles are signed and most have bibliographic information. Finding information in this source can be somewhat difficult as topics such as “Naselenie” do not have separate entries but are covered withing articles on specific areas, e.g. “Permskaia Oblast'” or “Ural’skaia Oblast.'” There are lengthy entries on art and archaeology. It is a source that requires some creativity on the part of the user due the fact that there is no index and little cross-referencing.

Historical Dictionaries and Chronologies:

There are many historical chronologies and a variety of single volume historical dictionaries. Many of the older sources can be identified in the guides listed above and will not be repeated here. The researcher will also find it useful to consult the Russian State and the Russian National Library Catalogs. In the latter a search in Russian for the the term “historical dictionary” brought up several references.

This is an efficient way to keep abreast of new sources that may be of interest for your research and often fills a gap in the printed resources.

Khronologiia rossiiskoi istorii. Entsiklopedicheskii spravochnik.

Moskva: “Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniia”, 1994. U of I Library Call Number : International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 947.03 K528:R

A very detailed chronology of the events in Russian history, this volume includes a set of historical maps, numerous statistical charts and an index of names. The chronology covers the years from 944 to 1991. For the student beginning in Russian studies this is a very useful source. Events are organized into categories within time periods. So, for example, the benchmarks in foreign policy that marked the years of Brezhnev’s rule are grouped into one category. Each time period begins with page long essay summarizing the events and characteristics of that time. Each section concludes with a brief biographical note on the most influential person of the period.

Atlas istorii kul’tury Rossii. Konets XVII-nachalo XX vv.

Rogov, E. N. Moskva: “Krug,” 1993. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 947 R635a

This is an extremely unusual chronology. The compiler tries to show the events of Russian history in the context of world events using time lines and comparative charts. The volume is divided into sections by discipline. These sections begin with an overview of the development of that discipline in Russia. This discussion is followed by a standard chronology, which is summarized in a “map” as shown in the example below, taken from p.29.

This chart or map appears in the first section of the atlas which examines the evolution of the study of history in Russia. The time lines here compare a variety of events the compiler hoped would reveal the development of the discipline. The volume includes sections on philosophy, literature, fine arts, music, theater, biology, geography, astronomy, mathematics, physics, chemistry, and technology. Following each map is a list of important figures in the field with brief biographies for each. While the volume does not cover the obscure or less well known figures, it is an unusual approach to the compilation of historical chronology. The compiler has included a list of the sources consulted.

La vie culturelle de l’emigration Russe en France. Chronique (1920-1930).

Beyssac, Michele. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1971. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 325.247 B46v

Drawing on the emigre press of Paris in the 1920s, Beyssac has compiled a sort of chronology of the intellectual and cultural life of the Russian emigre community in that city. The compiler consulted the major papers Vozrozhdenie and Poslednie Novosti in particular. From these he has drawn announcements of the activities of the cultural and intellectual societies concerning all their activities and presented this in a chronological arrangement. He has also provided access through a name and organization index. What emerges is a picture of the rich cultural life of the emigre community in Paris. It is a very valuable source in following the development of particular figures in the emigre community or in the study of the history of particular organizations.

Istoricheskaia nauka Rossiiskoi emigratsii 20-30-x gg. XX veka (Khronika).

Aleksandrov, S. A. Moskva: “Airo-XX”, 1998. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 016.947 Al27i

Like the French work by Beyssac this work follows the activities of the Russian emigre community. However, it does not limit its view to Paris but attempts to look at the emigre community in all of Europe. It does focus on a particular segment of Russian emigre society, those active in the study of history. The chronology lists the dates, authors, lecture titles or topics, place and the source of the information for thousands of events from 1921 to 1940. The compilers have drawn on the major emigre publications of the time: Posledne novosti; Rul’; Golos Rossii; Vozrozhdenie; Rossiia i Slavianstvo; Zapiski russkogo istoricheskogo obshchestva v Prage; Zapiski russkogo Nauchnogo Instituta v Belgrade; Sbornik russkogo istoricheskogo obshchestva v Prage.

Historical Dictionary of Russia.

Raymond, Boris and Duffy, Paul. London: Scarecrow Press, 1998. U of I Library Call Number : Main Stacks Reference 947.003 R214h

This volume is one in the series of European Historical Dictionaries. As with the other volumes there is a chronology of major events followed by an introduction that places Russian history in the context of European history in general. All entries in the volume are arranged alphabetically. Entries in the dictionary are brief and do not include any bibliography. However, there is an extensive bibliography at the end of the volume (approximately 40 pages long) which is organized by topic. There is a great deal of cross referencing within the entries. This volume could be extremely useful for the student beginning research in the field. This dictionary serves a different function than Pushkarev’s dictionary (see below) which focused on defining Russian language terms found in Russian historical sources. In this volume the compilers were attempting to gather all the major events and people for the beginning student and non-specialist.

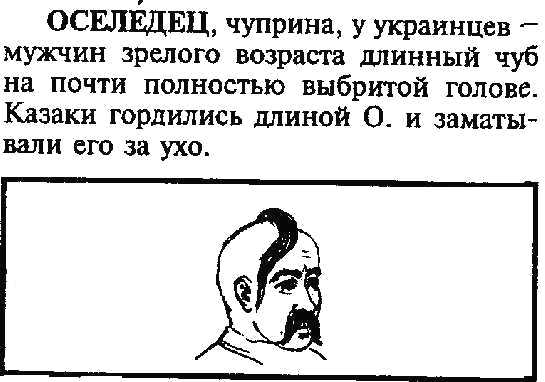

Dictionary of Russian Historical Terms from the Eleventh Century to 1917.

Pushkarev, Sergei G. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970.

U of I Library Call Number : International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) and Main Stacks 947.003 P97d

One of the most daunting problems for the student new to Russian history is the enormous number of specialized Russian historical terms. It is often difficult to find useful definitions for these terms in a standard Russian-English dictionary. Pushkarev’s dictionary solves this problem, supplying the student or scholar with a dictionary of those terms they are likely to encounter in historical studies. The dictionary includes civil, military and ecclesiastical ranks, political and judicial terms and economic and financial terms. Many of these terms have extensive descriptions with historical sketches elaborating their meaning. All terms are transliterated and the volume ends with a bibliography of all sources consulted. The above example gives an idea of the type of information in the briefer entries (p.184).

Rossiiskii istoriko-bytovoi slovar’.

Belovinskii, L. V. Moskva: “Rossiiskii Arkhiv,” 1999. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 947.003 B4188r

The Russian historico-civic dictionary includes some 4,000 words common in Russian society from the eighteenth to the beginning of the twentieth centuries. The dictionary contains many half-forgotten terms and many whose meaning have changed over the years. Unfortunately, the compiler has failed to provide any information on the source of his information. It is a source that would require some supporting information at the very least. Having said this, it does provide the experienced scholar with some leads on the meaning of obscure terminology. The example below is taken from the volume, p. 305.

Subject Web Sites

Russian history home page by john slatter.

URL: http://www.dur.ac.uk/a.k.harrington/Russhist.HTML

This is a collection of e-texts in English. The range of material is very interesting, including everything from excerpts of a translation of the Domostroi to a translation of the Program of the Socialist Revolutionary Party.

The beginning student of Russian history will find this a very useful site when seeking primary texts. Most have full attribution although there is no information on the source of the translation of the Domostroi . It is one of the sources that reminds the researcher how much electronic resources have changed in the last few years. Only a few years ago it would have been impossible to find retrospective materials of this kind available in full text on the internet.

Resursy WWW po istorii

URL: http://www.history.ru/hist.htm

Istoricheskie istochniki

URL: http://www.hist.msu.ru/ER/Etext/index.html

Rukopisnye Pamiatniki Drevnei Rusi

URL: http://www.lrc-lib.ru

This web site was created in collaboration with the Russian Language Institute of the Academy of Sciences. Its creators aimed at collecting the fullest possible online archive of old Russian manuscripts that are kept in museums and libraries both in Russia and abroad. The contents of the web site are separated into three parts: birch bark documents collection (located at the website http://gramoty.ru ), Russian chronicles, and Russian manuscripts. All the documents are available in full text versions either as PDF files or as GIF images.

Periodical Indexes

Indexes for historical periodicals are available in many formats. There are a number of online indexes such a Historical Abstracts that index major periodicals in the field. There are also digitization projects that have made a number of titles available. Project Muse and services like EBSCO are excellent resources for Western publications on Russia. For a general discussion, review the sources in the general Russian periodical section.

Ukazatel’ k russkim povremennym izdaniiam i sbornikam za 1703-1802 gg i k istoricheskomu rozyskaniiu o nikh .

Neustroev, A. N. St. Peterburg, 1898. xvi, 807 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 016.057 N39u 1963 HathiTrust full-text link: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433033580865

While this is not a historical bibliography or guide specifically, it is an important guide for research in 18 th century Russia because it indexes Russian periodical publications for this time period. Neustroev lists the periodicals indexed in the front of the volume, both chronologically and alphabetically. The second section is the index itself, which is arranged alphabetically by subject terms. Many articles are cross listed under multiple subjects; other subject terms have see also references. Citations are in abbreviated form: the abbreviations are given in the alphabetical listing of periodicals in the front of the book. Works both by and about persons are listed under the person’s name: for example, the entry for Catherine II lists both her works published in periodicals as well as works about her. This index is a part of the two volumes Neustroev issued that list the contents of the journals published in the 18th century. The entries for each title are extensive and will be very important for anyone researching this period.

Novaia literatura po sotsialnym i gumanitarnym naukam. Istoriia, arkheologiia, etnografiia. Bibliograficheskii ukazatel’.

Moskva: Institut nauchnoi informatsii po obshchestvennym naukam. Rossiiskaia Akademiia Nauk, 1947- . U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference Q.016.905 NO11(last 2 years) Main Stacks Q.016.905 NO11

This monthly publication is one of the best sources for current publications, articles and monographs on Russian history. If you are trying to keep up with current trends in Russian historiography, you will need to use this bibliography in its paper form or in one of its online versions. INION has made its records available through IntegrumWorld, which has the largest retrospective collection of INION databases, with records going back to the 1980s. Their is also a CD version being sold by INION with retrospective depth generally to the mid 1980s.

The bibliography, published monthly since 1947, includes a range of publications: monographs, collections of articles, dissertations, reviews, bibliographic works and deposited monographs. All are indexed in a detailed subject index in each issue. There is also an author index. Each issue is arranged by subject and includes a list of all indexed journals. Individual entries include full bibliographic information and often have short annotations on the publication. Bio-bibliographical entries on historians, archaeologists and ethnographers each have separate sections.

This is an excellent resource for anyone that is trying to keep up with currently published materials. The retrospective depth is excellent and it compliments Letopis’ zhurnal’nykh statei well as it serves as an index for titles not listed in that publication.

Biographical Resources

This section includes mostly biographical dictionaries or sets that are not covered in the Russian biographical archive . Those few that are both in the RBA and included here are of particular signifance and are noted as such. Resources for Russian biography are extremely rich and the Biographical Archive doesn’t even scratch the surface, so be sure to use this set as a starting point only.

Istoriki Rossii. Kto est’ kto v izuchenii otechestvennoi istorii: Biobibliograficheskii slovar’.

A.A. Chernobaev. Saratov: Izd. “Letopis,” 1997. 438 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference 947.0072 C423i

With biographies of almost 800 contemporary Russian historians and archaeologists, this source presents its material very clearly. Each entry gives basic biographical data including educational and career history as well as a bibliography of works by the individual and, if they exist, about the individual. Each entry also contains the historian’s particular fields of interest. The entries are arranged alphabetically by surname. Follow the link for the entry on Boris Sergeevich Abalikhin .

Kto byl kto v Velikoi Otechestvennoi voine. Liudi. Sobytiia. Fakty. Kratkii spravochnik.

O.A. Rzheshevskii, ed. Moskva: Respublika, 1995. 415 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 940.53470922 K949

Kto rukovodil NKVD 1934-1941. Spravochnik.

N.V. Petrov, K.V. Skorkin. Moskva: Zven’ia, 1999. 502 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 363.2830947 P4494

A fascinating reference book to be sure. This dictionary contains biographies and photos of the upper echelon of employees of the notorious secret police organization, the NKVD, and its regional organs, which perpetrated actions of mass terror against the Soviet populace. Many of the employees included in this volume were themselves arrested and/or shot at some point. The beginning of the book provides a history of the NKVD, a chart of its various departments and a list of the leaders of those departments. The body of the book comprises the biographical dictionary with entries in alphabetical order by surname. Besides basic biographical information, the entries include career data with very specific dates for service in the various sections of the secret police organization, ranks, medals, dates of death, and if applicable, dates of arrest, execution and rehabilitation. See the entry on Solomon Arkad’evich Bak.

Russian America: A biographical dictionary.

Pierce, Richard A. Kingston, Ontario: Limestone Press, 1990. 555 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 979.8020922 P611r

This English-language dictionary contains short biographical entries for 675 individuals, Russians, Americans, Native Americans, and others, who were involved in the development of Alaska before 1867. The entries for very famous figures such as Catherine the Great give basic historical significance and then focus on that figure’s relevance for the development of Alaska. Traders, merchants, royalty, politicians, Aleuts, and sailors are only some of the kinds of people featured in this source. Some portraits are included, but unfortunately no bibliographical references. See the entry below for Osip Larionov.

Portrety istorikov. Vremia i sud’by.

Moskva-Ierusalim: Universitetskaia kniga, 2000. 2 vols. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 947.00922 P838 v.1-2

This two volume set has long articles on the life and work of Russian historians. Historians from the Russian Academy of Sciences and various Russian universities and institutes collaborated to produce the entries which typically are 10 pages in length with a portrait and bibliographical references for works by and about the historian. The first volume covers Russian historians who specialized in the study of Russian history and the second volume covers those who studied world history. There is an index of names to enhance access to the texts.

Istoriki i kraevedy Moskvy. Nekropol’. Biobibliograficheskii spravochnik.

Ivanova, L.V. Moskva: Mosgorarkhiv, 1996. 220 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 907.202 Is7

Scholars who specialized in the study of Moscow or “ moskvovedy ” are the subject of this biographical dictionary. The articles provide biographical sketches of 191 moskvovedy who lived from the eighteenth century to the end of the twentieth. Entries, usually one page in length, are arranged alphabetically by surname and include birth and death dates if known, educational information, career highlights and bibliographic references. Several indexes enhance the text: one for names and one for burial places of the 191 individuals. See the entry on the left for the church historian A.I. Pshenichnikov.

Istoriki-Slavisty SSSR. Biobibliograficheskii slovar’-spravochnik.

Moskva: Nauka, 1981. 203 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies General Slavic Reference (Slavic) 016.94007202 Is7

This biographical dictionary contains brief articles about Soviet scholars who specialize in the post-1917 history of non-Russian Slavs. It also includes non-Soviet scholars who were active in the Soviet Union in the 1920’s through the 1940’s. Entries are arranged alphabetically by surname and contain brief educational and career data for each scholar as well as citations for the scholar’s major works. There are indexes of names and institutions. For scholars who specialize in pre-revolutionary Slavic history see Slavianovedenie v dorevoliutsionnoi Rossii. Biobibliograficheskii slovar’ . See the sample entry to the right on B. T. Gorianov.

Istoricheskii slovar’ rossiiskikh masonov XXVIII-XX vekov.

Platonov, O.A. Moskva: ARINA, 1996. 126 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 016.36610947 P697i

Based on archival documents that were unavailable to researchers until 1991, this dictionary offers unique coverage of members of the secretive masonic organization. The book is divided into 3 parts: 18th century up to the reign of Nicholas II, the reign of Nicholas II up to World War II, and 1945-1996. Within each section the entries are arranged alphabetically by surname. Entries are brief with full name, career designation and information about the each individual’s masonic membership. Use the abbreviation keys to clarify the masonic terms and sources. See the entry to the left for engineer and Duma member, Nikolai Nekrasov.

Gosudarstvennye deiateli Rossiiskoi Imperii. Glavy vysshikh i tsentral’nykh uchrezhdenii 1802-1917. Biobibliograficheskii spravochnik.

Shilov, D.N. Sankt-Peterburg: Dmitrii Bulanin, 2001. 830 p. + 2nd ed. 2002. 936 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 947.0099 Sh62g + 947.0099 Sh62g2002

Based on materials located in 9 different Russian archives, this biographical dictionary has 281 entries for pre-revolutionary government officials. Entries are typically several pages in length and include biographical data, a section on a figure’s service career, a section for honors, a statement of the figure’s cultural and societal activity, a list of works by the person, and a bibliography of printed and archival materials. The bibliographical and archival references are extensive. The references are divided into several sections such as memoir sources, encyclopedic sources, genealogical materials, etc. Much of the material in this volume has never been published before. Appendices include a chronological listing of all the directors of the various ministries from 1802-1917, a genealogical index showing family relationships of the officials included, and a bibliography.

Biograficheskii spravochnik vysshikh chinov Dobrovol’cheskoi armii i Vooruzhennykh Sil Iuga Rossii. (Materialy k istorii Belogo dvizheniia).

Rutych, N. Moskva: Regnum-Rossiiskii arkhiv, 1997. 295 p. U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 947.08410092 R939b

Compiled by a noted Russian emigre historian who used a variety of archival sources, this recent biographical dictionary aims to acquaint the user with Russian military officers who fought against the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War. Many of the men whose biographies are included in this source perished during the war or died in emigration. A typical entry includes full name, dates of birth and death, rank, as well as a brief biographical sketch which highlights the career and, in particular, the individual’s participation in the White movement. Often the place of death and burial is also provided. Some of the entries have bibliographical references. See the entry below for Vasilii Petrovich Petrov.

NdR, la Noblesse de Russie; éléments pour servir à la reconstitution des registres généalogiques de la noblesse, d’après les actes et documents disponibles complétés grâce au concours dévoué des nobles russes.

Ikonnikov, Nicolas F. Paris: Bibliothèque slave, 1957-1966. 2nd edition. 26 vols. U of I Library Call Number: Main Stacks 929.77 Ik7n 1957 v.1-26

Although this source is not that easy to use, it nevertheless offers a wealth of biographical and genealogical information about the Russian nobility from the earliest times to the twentieth century. The first twenty volumes present the families in alphabetical order with volume 21 as an index with additions and corrections. The next five volumes present additional families, but the entire alphabet is covered in each volume. On the title page of each volume are listed the families covered in that volume. At the beginning of some family sections Ikonnikov provides a brief overview of the family’s history. At the end of each family section is an index of first names for the family with numerical indications for the entries in which the names appear. The members of the families are listed chronologically with the earliest ancestors coming first. Each generation/filiation is designated by a Roman numeral with each person assigned an Arabic numeral. Different branches of the family are presented after the main branch and are indicated by capitol letters A, B, C, etc. Be prepared to read French for the descriptions of the family members and to recognize French transliteration of Russian names such as Pouchkine for Pushkin and Youri for Iurii. The entries usually give the dates of life for the person, any titles or military ranks, and sometimes more information if the person was a notable figure. Bibliographic sources for the information appears in abbreviated form in parentheses in each entry with the list of sources printed at the beginning of the first volume and in volume 21. Spouses who married into a particular family are listed below their spouse and indented a little. References to spouses’ families that also have warranted their own genealogies in Ikonnikov are indicated with the following notation: for a member of the Khroustchov family (NdR K ° C.13). NdR stands for Noblesse de Russie, K means in the volume with surnames beginning in K, family branch C, personal entry 13. See the entry below for the founding fathers of the Meshcherskii family. Note the column on the right that shows the father’s entry number.

Why Study Russian History?

E. Thomas Ewing and Virginia Tech Students enrolled in HIST 3604: Russia to Peter the Great | Mar 13, 2017

Last fall, Virginia Tech students taking History 3604: Russia to Peter the Great engaged in a sustained discussion on “why study history?” In the class, we often took examples from current news or recent history and established connections to the historical period covered by the readings, lecture, and assignments (here’s a link to the syllabus ). Each week, a group of two or three students wrote a short statement explaining how the readings illustrated the value of studying history, which we then discussed in class. Finally, at the end of the semester, the entire class collaborated on this essay, which synthesizes those weekly contributions into a reflection on why studying the history of Russia to Peter the Great is intrinsically and instrumentally valuable.

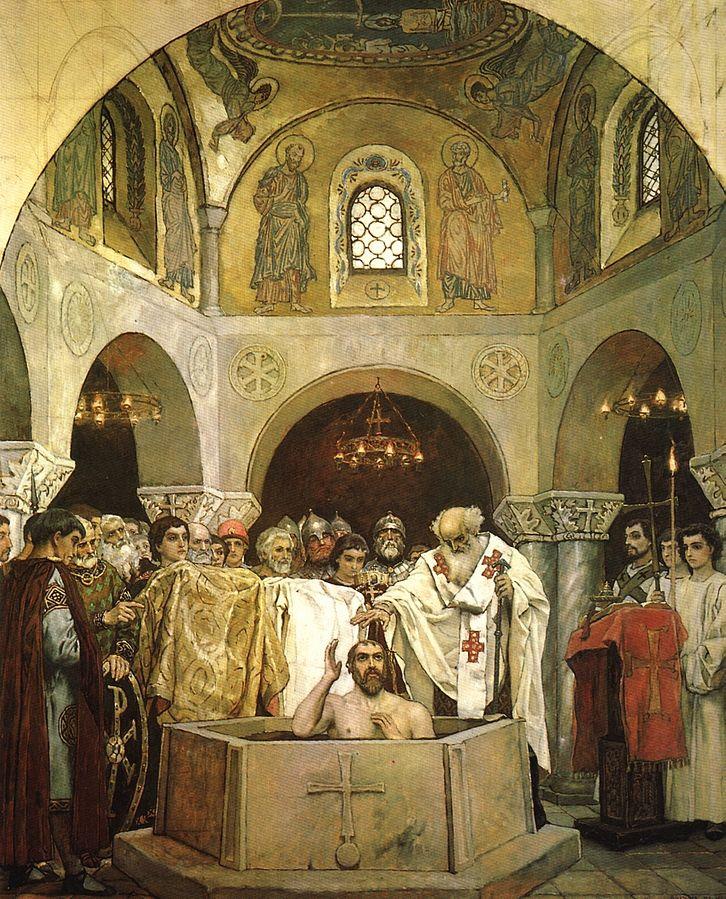

Illustration 1: Baptism of Russia, painted by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1890. Wikimedia Commons

Studying Russian history from its founding in the ninth century until the beginning of the era of Peter the Great in the late 17th century illustrates how this emerging nation-state navigated complex processes such as building a national political order, sustaining an evolving cultural identity, and legitimizing power through personality, rituals, and institutions. Studying these processes in a historical context—distant in terms of both time and location—provides insights into similar patterns in the more recent past, the present, and into the future, thus demonstrating why history matters.

This course on early Russian history, for example, helped students appreciate the complex relationships that exist between cultures that share the same geographical space. Russia was created in the ninth century when indigenous Slavic communities gradually integrated with the Scandinavian ruling elite. Since then, Russian history has been characterized by tensions between internal cohesion and external threats. This is most obvious during the 14th and the 15th centuries, when Mongol rule threatened the very existence of the Russian political system. At the same time, this era witnessed the consolidation of power by Moscow’s princes, political collaboration between church and state, and creation of a foundation for the steady expansion of boundaries under the Russian autocratic state of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Illustration 2: Church Schism, painted by Vasilii Surokov, 1886. Wikimedia Commons

The course also allowed students to acquire insights into the formation of Russian national identity. Geographical location enabled, and indeed compelled, Russians to interact with neighboring states, peoples, and cultures on all sides in ways that shaped formal customs, influenced spiritual values, and guided cultural practices. Over the centuries, for example, the Orthodox Church contributed to a growing sense of cultural identity among the Russian population while also defining boundaries with adjoining cultures, peoples, and states. In the 17th century, the church’s role in fostering national unity during the Time of Troubles, when Russia was invaded by foreign armies, was followed by a schism that divided the nation, communities, and even families (illustration 2).

Illustration 3: Ivan IV and the oprichniki, by Nikolai Nevrev, painted in the 1870s. Wikimedia Commons

The evolving role of political leaders from the founding of the Russian state through the Mongol era and into the early modern period also provides evidence of the legitimization of power through personality, rituals, and institutions. The conversion of Russia to Christianity under Vladimir (ruled 980–1015) (illustration 1), the legal codes introduced by Iaroslav (ruled 1019–54), the military campaigns of Vladimir Monomak (ruled 1113–25), and the national reconciliation under Mikhail (ruled 1613–45) are examples of political leadership that undermine simplistic claims of immutable or inevitable autocracy in Russia. The reign of Ivan the Terrible—a central topic of this course—provides a clear example of how a nuanced approach to history matters. Ivan IV (ruled 1547–84) successfully expanded Russia’s borders, consolidated personal power, and strengthened the state (illustration 3). At the same time, his capricious actions, arbitrary methods, and personal ambitions caused numerous deaths, contributed to economic collapse, and put the survival of Russia in jeopardy. Exploring the actual exercise of power within changing contexts provided students with skills for examining the dynamics of political action and reaction in more recent contexts, including the most obvious current example, the presidency of Vladimir Putin. Throughout the semester, the class discussed how Putin’s use of political symbolism, his reliance on a network of loyalists, and his efforts to position Russia between Europe and Asia were connected to specific themes from earlier periods of Russian history.

Studying history is not just about collecting facts—instead, it is a process of acquiring, mastering, and analyzing layered and nuanced information on many subjects. The value of history thus lies in the ability to identify, process, and synthesize potentially overlooked details to explain a broader idea, culture, or event. Teaching history in reference to current examples is also a powerful reminder of how an unexpected historical turn can change perceptions. On September 6, when the topic was the role of warrior princes in the first centuries of Russian history, the class began with a discussion of several well-known images of Putin engaged in traditionally masculine activities such as hunting, fishing , and horseback riding . In the following class, September 8, this question of images of political strength was further illustrated with a widely circulated photograph of President Obama and President Putin engaged in what appeared to be a tense exchange at the G20 meeting in China. It was only three months later that we learned that this exchange was the moment when Obama confronted Putin with accusations about hacking the Democratic National Committee. For historians, even the most recent past is subject to revision, as new knowledge is disclosed in ways that change interpretations of historical events. This willingness to think critically and creatively about the past is the most valuable lesson that students can learn from repeatedly asking the question: why does history matter?

This post first appeared on AHA Today .

E Thomas Ewing is professor history and associate dean of graduate studies and research in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences at Virginia Tech. This essay was co-authored by his students enrolled in HIST 3604: Russia to Peter the Great.

Tags: AHA Today Asia/Pacific Europe Global History

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities , and in letters to the editor . Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

In This Section

Russian History & Culture

About this guide, library catalog search.

- Tsarist Russia

- Soviet Russia

- Post-Soviet Russia

- Religion in Russia

- Russian language and literature

- Russian ballet and music

Senior Lecturer, Archives and Special Collections

This guide provides a brief overview of Russian history and culture. In the timeline feature below, suggested research topics are bolded. On each subsequent page, relevant books from the CWU library catalog are also suggested, as are some external resources.

When you are ready to move on from this guide, even if you only stopped by briefly, please take the one-question poll at the bottom on the page on whether it was useful or interesting to you.

- Kievan Rus & Muscovy (c. 900-1689)

- Imperial Russia (1689-1917)

- Soviet Russia (1917-1991)

- Post-Soviet Russia (1991 - present)

800s: The Rus , traditionally a people of Scandinavian origin, establish a presence in parts of modern-day Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine.

Late 900s: Rise of Kievan Rus , a confederation of city-states headed by the grand prince of Kiev.

c. 980-1015: Reign of Prince (St.) Vladimir I. He introduces Christianity to the region.

1230s: The Mongols ( Tatars ) invade the region, subjugating the fragments of Kievan Rus. Kiev declines in importance, while Moscow, Tver, and other cities rise. The regional successor state to the Mongol empire is later known as the Golden Horde .

1313-41: The Golden Horde reaches the height of its power under Khan Öz Beg.

1395-96: The Turco-Mongol warlord Timur ( Tamerlane ) destroys the Golden Horde's principal cities of Sarai, Azov, and Kaffa. The Golden Horde's dominion over the Russian princes subsequently becomes nominal.

1462-1505: Reign of Ivan III the Great of Moscow. He annexes the rival city-states of Novgorod and Tver and other territories.