Aims and scope

The proliferation of derivative assets during the past two decades is unprecedented. With this growth in derivatives comes the need for financial institutions, institutional investors, and corporations to use sophisticated quantitative techniques to take full advantage of the spectrum of these new financial instruments. Academic research has significantly contributed to our understanding of derivative assets and markets. The growth of derivative asset markets has been accompanied by a commensurate growth in the volume of scientific research. The Review of Derivatives Research provides an international forum for researchers involved in the general areas of derivative assets. The Review publishes high-quality articles dealing with the pricing and hedging of derivative assets on any underlying asset (commodity, interest rate, currency, equity, real estate, traded or non-traded, etc.).

Specific topics include but are not limited to:

econometric analyses of derivative markets (efficiency, anomalies, performance, etc.) analysis of swap markets market microstructure and volatility issues regulatory and taxation issues credit risk new areas of applications such as corporate finance (capital budgeting, debt innovations), international trade (tariffs and quotas), banking and insurance (embedded options, asset-liability management) risk-sharing issues and the design of optimal derivative securities risk management, management and control valuation and analysis of the options embedded in capital projects valuation and hedging of exotic options new areas for further development (i.e. natural resources, environmental economics.

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Help & FAQ

Introduction to Financial Derivatives: modeling, pricing and hedging

Research output : Book/Report › Book › Professional

- Derivatives

- stock exchanges

Access to Document

- 10.26116/openpresstiu-schumacher-04-2020 Licence: CC BY-NC-ND

- INTRODUCTION_TO_FINANCIAL_DERIVATIVES Final published version, 5.31 MB Licence: CC BY-NC-ND

Fingerprint

- financial derivatives Social Sciences 100%

- pricing Social Sciences 56%

- finance Social Sciences 48%

- interest rate Social Sciences 38%

- insurance Social Sciences 27%

- credit Social Sciences 24%

- textbook Social Sciences 24%

- mathematics Social Sciences 19%

T1 - Introduction to Financial Derivatives

T2 - modeling, pricing and hedging

AU - Schumacher, J.M.

N2 - Financial derivatives are widely used as instruments to modify exposures to various types of financial risk. Examples include call options on a stock index, interest rate derivatives such as swaptions, and credit derivatives. The theory of financial derivatives, as it has been developed in recent decades, is based on a mix of economic ideas and concepts from mathematics.The material in this Open Press textbook originates from notes for a course that the author has taught at Tilburg University for more than ten years, as part of the MSc program in Quantitative Finance and Actuarial Science. The text aims to provide students with an introduction to continuous-time models that are used to analyze derivative contracts in finance and insurance. Users are expected to have a solid background in standard calculus, linear algebra, and probability; prior experience with stochastic calculus, however, is not a prerequisite.

AB - Financial derivatives are widely used as instruments to modify exposures to various types of financial risk. Examples include call options on a stock index, interest rate derivatives such as swaptions, and credit derivatives. The theory of financial derivatives, as it has been developed in recent decades, is based on a mix of economic ideas and concepts from mathematics.The material in this Open Press textbook originates from notes for a course that the author has taught at Tilburg University for more than ten years, as part of the MSc program in Quantitative Finance and Actuarial Science. The text aims to provide students with an introduction to continuous-time models that are used to analyze derivative contracts in finance and insurance. Users are expected to have a solid background in standard calculus, linear algebra, and probability; prior experience with stochastic calculus, however, is not a prerequisite.

KW - Derivatives

KW - finance

KW - economy

KW - markets

KW - stock exchanges

U2 - 10.26116/openpresstiu-schumacher-04-2020

DO - 10.26116/openpresstiu-schumacher-04-2020

SN - 978-94-6240-612-4

BT - Introduction to Financial Derivatives

PB - Open Press TiU

- Previous Chapter

- Next Chapter

Financial derivatives are commonly used for managing various financial risk exposures, including price, foreign exchange, interest rate, and credit risks. By allowing investors to unbundle and transfer these risks, derivatives contribute to a more efficient allocation of capital, facilitate cross-border capital flows, and create more opportunities for portfolio diversification. Thus, financial derivatives are essential for the development of efficient capital markets. However, just like any other complex financial instrument, derivatives may and, in fact, have at times been used by market players to take on excessive risk, avoid prudential safeguards, and manipulate accounting rules. For example, in the absence of adequate internal risk control and prudential supervision, derivative instruments may allow a company to take on excessive leverage by shifting certain exposures off balance sheets. Although the problem of misuse of derivatives is perceived to be more acute in emerging market countries where prudential regulation, credit information infrastructure, and risk management practices are not fully developed, it is certainly not limited to these countries. In a world of constantly evolving financial instruments, the design of prudential regulations that create incentives for market participants to use derivatives appropriately remains one of the biggest challenges for regulators in both mature and emerging markets.

This chapter provides an overview of local derivatives markets in emerging economies and focuses on two issues: how the use of derivatives facilitated capital flows to emerging economies and what was the role of derivatives in past emerging market crises.

Overview of Derivatives Markets in Emerging Economies

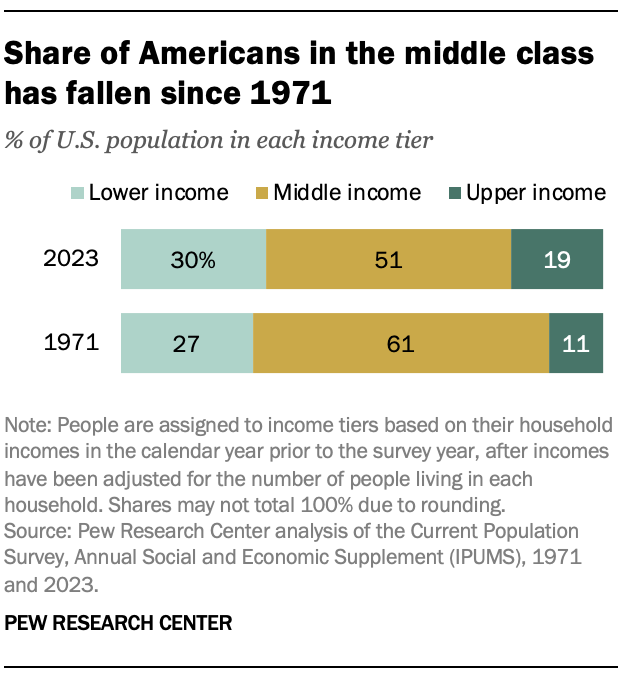

Despite rapid growth over the past several years, emerging market derivatives account for only 1 percent of the total outstanding notionals in global derivatives markets. Local derivatives markets in emerging economies differ greatly in their sizes, both in absolute terms and relative to cash markets. Compared with mature markets, the ratio of outstanding notional value of derivatives to market capitalization of the underlying asset markets is fairly small in most emerging economies (see Table 9 ). The most common problems that constrain the development of local derivatives markets are (1) relatively underdeveloped markets for underlying instruments; (2) weak/inadequate legal and market infrastructure, and (3) restrictions on the use of derivatives by local and foreign entities.

Notional Amounts Outstanding of the Over-The-Counter and Exchange-Traded Derivatives

(In billions of U.S. dollars; end-June, 2001)

- Currency Derivatives

Most of the currency derivatives trading around the world takes place in the over-the-counter (OTC) markets, with foreign exchange swaps accounting for more than two-thirds of the turnover. The turnover in global currency markets followed a declining trend from 1998 and up until early 2001 due to the introduction of the euro, expansion of E-broking, and banking sector consolidation. By contrast, during the same period, the turnover in the emerging foreign exchange spot and derivatives markets increased, with the share of emerging market currencies (including the Hong Kong SAR and Singapore dollars) in the global foreign exchange spot market turnover rising to 8.6 percent in April 2001 from 5.5 percent in April 1998 (see Table 10 ). The declining trend in global currency markets was reversed during 2001–02, as the volume of euro/dollar contracts, which replaced the European legacy currency contracts, gradually increased and the volatility of G-3 currency pairs rose sharply in the first half of 2002. As a result, the total notional value of outstanding contracts in global OTC foreign exchange derivatives markets reached $18.5 trillion as of end-2002, approaching the mid-1998 level ($18.7 trillion). 63 Of note is the fact that the share of swaps in the total notional value of foreign exchange derivatives rose to 24 percent at the end of 2002 from 10 percent in mid-1998, which was generally attributed to a pickup in global syndicated loan and securities issuance.

Average Daily Turnover in the Over-The-Counter Derivatives Markets

(In billions of U.S. dollars)

In emerging markets, the most liquid OTC currency derivatives markets are in Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, and South Africa, where average daily turnover significantly exceeds the spot market turnover (see Table 10 ). Foreign exchange swaps and forwards are used by both foreign and domestic players for managing or gaining exposure to the exchange rate risk, with the trading volumes typically increasing during the times of large exchange rate movements. The buoyancy of these markets tends to be affected by the stringency of local currency regulation and by the degree of foreign investor participation. In Singapore, a notable pickup in crosscurrency swaps activity occurred after 1998, when the government allowed foreign entities to issue Singapore dollar bonds and to swap the proceeds into foreign currency for use outside the country. Furthermore, in 2002, the government removed the restriction that did not allow foreigners to engage in cross currency swap transactions unless there was an underlying economic activity. In Korea, up until 1999, the development of the onshore currency derivatives market was constrained by a legal requirement that any forward transaction had to be certified as a hedge against future current account flow (the so-called “real demand principle”) and therefore, most of the won/dollar forward trades look place offshore. In South Africa, the turnover in foreign exchange swaps caught up with the spot market turnover around the time of the Asian crisis and significantly surpassed the latter in subsequent years (see Figure 15 ). However, the swaps market liquidity has deteriorated notably since late 2001, when the central bank stepped up the enforcement of currency regulation requiring market participants to provide evidence of an underlying trade flow for every forward or swap transaction, and, as a result, many foreigners pulled out of the South African foreign exchange market (see Figure 16 ). 64

Average Daily Turnover in the South African Foreign-Exchange Market by Type of Transaction

- Download Figure

- Download figure as PowerPoint slide

Average Daily Turnover in the South African Foreign-Exchange Swap Market

By contrast with Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, and South Africa, a significant share of currency derivatives trading in Brazil takes place at the organized exchange—Bolsa de Mercadorias & Futuros of Sao Paulo (BM&F). Besides certain features of the country’s legal framework that had hampered the development of the OTC market, the BM&F itself was actively trying to absorb part of the OTC business (see Box 7 ). 65 The expansion of currency derivatives in Brazil was stimulated by the flotation of the real in early 1999 and regulatory authorization for OTC derivatives on foreign exchange, interest rates, and price indexes. The change in the exchange rate regime coincided with sharply higher volatility in both the real/dollar rate and Brazilian interest rates, contributing to the creation of a “hedge culture.” Most of the derivatives contracts are “nondeliverable” because historically, the BM&F did not want local derivatives markets to be limited either by less than free convertibility of the real or by the size of the spot market, with the latter also being susceptible to short squeezes. In contrast to the rapid growth of derivatives markets in Brazil, the development of exchange-traded derivatives in Mexico has been slower, primarily because the exchanges in Chicago (which are in the same time zone) have launched numerous derivative products based on Mexican underlying assets.

The “nondeliverable” forward (NDF) contracts tend to be the principal instruments in the offshore derivatives markets for many emerging market currencies and are often preferred by foreign investors who have restricted access to onshore markets and want to either avoid potential costs of delivering local currencies or reduce their counterparty credit risk exposure. In most cases, NDF markets trade at a premium to local markets because offshore financial institutions have limited access to local funding. In Taiwan Province of China, for example, the average implied one-year NDF yields were around 150 basis points higher than onshore rates during 2001–02. In Korea, the existence of the “real demand principle” spurred the development of a liquid offshore NDF market in the Korean won. However, after this restriction was lifted in 1999, a lot of activity moved onshore, leading to the convergence of the offshore and onshore prices. In some cases, however, offshore markets continue to perform functions that are not performed by onshore markets. For example, while both onshore and offshore forward markets in Korea are most liquid in maturities of up to one year, the NDFs and swaps can be structured in tenors of up to 10 years in the off-shore market.

The Bolsa de Mercadorias & Futuros of Sao Paulo

The Bolsa de Mercadorias & Futuros (BM&F) of Sao Paulo, Brazil, which started operations in January 1986, ranks among the largest exchange-traded derivatives markets in the world in terms of the number of contracts transacted annually. In 2001, almost 98 million contracts were traded with a total open interest of 74 million contracts. These figures were surpassed in 2002: by the end of 2002 the cumulative number of contracts traded was 105.8 million. According to International Financial Services, London, the BM&F ranked ninth in terms of the number of contracts traded by the end of 2001, being surpassed among emerging markets only by the Korean Stock Exchange.

Trading at the BM&F takes place through the auction market system, which comprises both the exchange floor and the electronic trading system. Most contracts are traded in the auction market system, which accounted for 94 percent of all contracts traded and 97 percent of financial volume in 2001, while the over-the-counter (OTC) system accounted for the remaining transactions. The performance of all contracts traded through the auction system is guaranteed by the BM&F Derivatives Clearinghouse, which uses a safeguard structure based on intraday risk limits, market concentration limits, and collateral requirements imposed on clearing members, brokerage houses, and customers. The safeguard structure is complemented with three clearinghouse funds that provide additional levels of protection against counterparty risk. Other transactions in the OTC market system must be registered either with the BM&F or the Central of Custody and Financial Settlement (CETIP) if at least one of the counterparties is a financial institution. The settlement of OTC contracts registered with the BM&F can be guaranteed by the exchange upon request of the contractual parties provided the contract is written according to the BM&F specifications, which ensures a certain level of standardization. In practice, most of the OTC contracts are guaranteed by the BM&F.

The BM&F offers end users of the exchange a substantial number of contracts, allowing them to hedge risks or acquire market exposure. Futures contracts are available on a number of commodities, including gold, on the Sao Paulo Exchange Stock Index (Ibovespa); on foreign currencies, including the U.S. dollar and the euro; and on interest rates, including short and long interbank deposit rates, and the local U.S. dollar interest rate (Cupom Cambial). Option contracts are available on gold, interbank deposit rates, the Ibovespa, and the U.S. dollar. However, liquidity in the BM&F is heavily concentrated in a few contracts, including the one-day interbank deposit futures contracts or DI Futures, U.S. Dollar Futures, especially for those with maturities of one year or less, Ibovespa Index Futures, and Cupom Cambial futures. Some of these contracts are described next.

DI Futures . This contract allows end users to hedge or take positions on local interest rate risk. The contract size is 1 million reals and the underlying asset is the capitalized daily interbank deposit rate, as measured by the Certificate of Deposit rate, verified on the period between the trading day and the business day preceding the expiration date of the contract, which is the first business day of the contract month. All contracts are settled on a cash basis. Contracts months include the first four months subsequent to the month during which a trade is made, and months that initiate a quarter (January, April, July, and October). DI Futures with maturities less than two years enjoy good liquidity, with an average daily turnover in the range of $5 billion to $10 billion.

Foreign exchange derivatives . The two- and three-month U.S. Dollar Futures, with contract sizes of $50,000, are the most traded and liquid contracts, with an average daily trading volume of around $3 billion. Contract months include every month of the year and should be settled on a cash basis the next business day following the last business day of the previous month. Hedging and speculation in the foreign exchange market can also be accomplished via U.S. Dollar European and American Options in the auction and OTC market systems, respectively. The average daily trading volume in this market is only around $250 million, a fraction of the volume traded in the futures market. In terms of open interest, though, U.S. Dollar Options accounted for 30 percent of total exchange-traded foreign currency instruments by the end of July 2002.

Ibovespa Index Futures , Local investors can engage in index arbitrage and hedge positions on the main Brazilian stock market index, Ibovespa, through Ibovespa Index Futures. The contract size in Brazilian reals is equal to three times the level of the index. These contracts mature every two months and are settled on a cash basis on the next business day following the Wednesday closest to the 15th calendar day, which is the last trading day. Trading in the Ibovespa index futures comprises 86 percent of total trading in stock index instruments, as measured by number of traded contracts.

Cupom Cambial Futures . The Cupom Cambial for a given maturity is the spread basis points higher than onshore rates during 2001–02. In Korea, the existence of the “real demand principle” spurred the development of a liquid offshore NDF market in the Korean won. However, after this restriction was lifted in 1999, a lot of activity moved onshore, leading to the convergence of the offshore and onshore prices. In some cases, however, offshore markets continue to perform functions that are not performed by onshore markets. For example, while both onshore and offshore forward markets in Korea are most liquid in maturities of up to one year, the NDFs and swaps can be structured between the local interest rate, as measured by the interest rate on interbank deposits, and the exchange rate variation during the life of the contract. From this definition, it is clear that the Cupom Cambial is equivalent to the onshore U.S. dollar interest rate and, hence, its level is affected by corporate demand for foreign currency hedging. The Cupom Cambial Futures allow local market participants—mostly nonfinancial companies, banks, and mutual funds—to position themselves in the local U.S. dollar interest rate market. Contract size is $50,000 and contract months and expiration dates are established by the BM&F. Contracts are settled in cash.

The BM&F follows state-of-the-art risk management procedures to deal with market risk, liquidity risk, and counterparty risk. These procedures have helped the BM&F to withstand several episodes of market turbulence, including the January 1999 crisis, the Argentina crisis by the end of 2001, and the current volatility associated to the recent presidential elections. Despite this impressive track record, the BM&F remains highly exposed to sovereign risk, as close to 90 percent of the exchange’s collateral is comprised by Federal Government Bonds.

Compared with other emerging markets, the liquidity in the Central European onshore derivatives markets remains limited due to the lack of effective infrastructure and also to some extent existing regulatory constraints on the use of hedging instruments by local corporates and pension funds. Hungary has seen a strong pickup in currency derivatives trading since the move to greater exchange rate flexibility and removal of capital controls; but, compared with Poland, liquidity is still low (see Tables 9 and 10 ). Many of the derivatives linked to the Central European currencies are reportedly traded offshore, mainly out of London. More recently, both Poland and Hungary have made significant progress in improving legal and documentation infrastructure for derivatives trading. The Polish government adopted new provisions on netting and credit support, while in Hungary, the close-out netting provisions came into effect in January 2002. Legal certainty regarding enforceability of close-out netting reduces credit risk arising from OTC derivatives transactions by allowing market participants to calculate their net obligation vis-à-vis an insolvent party.

- Fixed-Income Derivatives

In contrast to recent trends in global currency derivatives market, the global fixed-income derivatives market continued to expand steadily over the past few years, with interest rate swaps (IRS) being the largest and the fastest growing market segment. From end-1998 to end-2002, the notional value of all outstanding interest rate contracts in the global OTC market doubled, reaching $102 trillion (see BIS, 2002b ). The rapid expansion of the IRS activity was triggered by the liquidity crunch in the spot and exchange-traded derivatives markets during the Russia/LTCM crisis and the reduction in the U.S. government bond market liquidity due to the planned debt repayments. These were generally seen as the main factors that forced market participants to look for alternative hedging and benchmark instruments and encouraged the shift into the OTC swap market (see IMF, 2001 ). Following the collapse of the telecommunications, media, and technology (TMT) bubble, an increased equity price volatility and a continued decline in interest rates forced many investors, including those in emerging markets, to shift from stocks to bonds, turning to the bond futures and IRS markets either in search of yield or to hedge their bond exposures. The structure of the global fixed-income derivatives market is similar to that of currency derivatives—that is, the OTC segment is significantly larger (when measured in terms of notional values) than the exchange segment, although the average daily turnover in the latter is higher, possibly due to shorter maturity of the exchange-traded instruments.

In emerging market countries, the most liquid fixed-income derivatives markets are in Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa (see Tables 9 - 11 ). In Latin America and Singapore, most of the fixed-income derivatives trading takes place at the organized exchanges, but in Korea and South Africa it is mainly concentrated in the OTC market (see Table 9 ). Those markets that were deregulated more extensively (most notably in Korea) experienced the fastest growth. In terms of notional values, the Singapore Exchange (SGX) is still far ahead of other emerging markets, with most traded fixed-income derivative contracts including Euroyen LIBOR, Euroyen TIBOR, and Eurodollar futures and options. The rapid pickup in the fixed-income derivatives activity in Mexico was due to an increased government bond issuance, easier access to derivatives trading for local banks and brokers (because of a relaxation of certain administrative restrictions), and the introduction of new products by the Mexican Derivatives Exchange (MexDer) (see Figure 17 ). In contrast to Mexico, the fixed-income derivatives activity in Brazil has contracted, largely reflecting the weakness of the underlying bond market.

Exchange-Traded Options and Futures Contract Trading Volume, 2002

Mexican Bond Issuance and Interest Rate Futures

Falling interest rates and increased local bond issuance were the main factors that spurred the expansion of the local currency IRS markets. In addition, the proliferation of structured products in Hong Kong SAR, Korea, and, more recently, Taiwan Province of China created additional demand for instruments, such as interest rate swaps, which are used to hedge these exposures. In some countries, most notably in Brazil and Hong Kong SAR, the IRS market has become more liquid than the underlying cash market and as a result performs functions that are typically provided by bond markets, such as price discovery and provision of benchmarks. For example, in Brazil, the local swap curve is the benchmark yield curve for maturities beyond one year. In Hong Kong SAR, given the relatively small size of Exchange Fund bond issues, the swap market is more liquid and therefore drives the pricing of local bonds. By contrast, the South African government bond yield curve remains the benchmark curve, despite the fact that the outstanding notional value of local currency interest rate swaps significantly exceeds the local bond market capitalization. This is largely due to the fact that the South African government’s debt management policy was specifically aimed at maintaining and improving the liquidity of the benchmark bond issues.

In some countries, the presence of sophisticated institutional investors and the relaxation of restrictions on their participation in local derivatives markets contributed to the rapid expansion of the fixed-income derivatives activity. For instance, one of the key drivers behind the growth of the IRS market in Korea was the entry of the investment trust companies that were allowed to hedge up to 5 percent of total assets using local derivatives. In Singapore, insurance companies, which form the core of the local institutional investor base, increased their participation in the longer-dated interest rate derivatives market as well. Similarly, in Taiwan Province of China, pension and insurance companies became more active users of debt-related derivatives, following their shift toward fixed-income investments and away from equity and real estate. In South Africa, unit trusts are less involved in the swap market because of a number of restrictions. However, other institutional investors are very active in the IRS market, with local banks concentrating on the one- to five-year maturity segment and pension funds—on the 5+ year spectrum. In Mexico, the regulatory authorities have recently issued guidelines for pension funds limiting their use of derivative products only by a certain level of the Value-at-Risk measure. Because in many countries regulation allows local institutional investors to use only standardized exchange-traded products, the introduction or, in some cases, widening of the range of such instruments may be a necessary condition for further expansion of the derivatives activity. 66

In contrast to the IRS markets, the government bond futures markets in emerging economies tend to be less active. Since bond futures are primarily used for hedging the underlying bond exposures, the liquidity in bond futures is very sensitive to the spot market activity. For instance, the average trading volume of the three-year Korean government bond future contract has closely mirrored the performance of the underlying bond since the introduction of the derivative contract in September 1999 (see Figure 18 ). Thus, countries with less developed government bond markets are generally less successful in developing bond futures markets, especially when there are alternative hedging instruments that are sufficiently liquid. One example is the future contract on the five-year Singapore government bond, which was launched in June 2001 but never look off in earnest, with the average daily volume falling from 878 contracts in July 2001 to only about 10 contracts at the end of 2002. This was partly due to the weak activity in the underlying instrument, but also to the fact that local banks, which were the main holders of government bonds, could hedge their bond positions more efficiently by using swaps. South Africa is another interesting case, where the bond market is very liquid and there are several benchmark bond futures listed on the exchange; however, most of them are rarely traded. The illiquidity of bond futures in South Africa is explained by the existence of a very liquid domestic bond repo market (the so-called “carry market”).

Korean Government Bond Futures

- Equity Derivatives

Compared to currency and fixed-income derivatives, the equity-based derivative products represent a much smaller part of the global market, with the bulk of activity concentrated at the organized exchanges. This reflects in part the diminishing role of local equity markets as a source of funding for local entities. Nonetheless, the volume of exchange-traded equity futures and options in most major markets rose steadily over the past few years, as the increased volatility in global equity markets, as well as the introduction of retail-oriented and sector-based products, led more market participants to use equity derivatives.

While most exchanges in emerging Asia experienced steady expansion in equity derivative products over recent years, the stock index derivatives’ growth in Korea was spectacular (see Figure 19 ). The average daily trading volume in KOSPI 200 options and futures, which are the most liquid derivative contracts traded on the Korean Stock Exchange (KSE), rose to 4.7 million contracts at the end of 2002 from 0.9 million contracts at the end of 2000. 67 As a result, Korea now accounts for about 30 percent of global turnover in stock index derivatives. 68 The average daily volume of index futures and options traded on Taiwan Futures Exchange (Taifex) doubled between the end of 2000 and the end of 2002. Outside Asia, South Africa has the most developed equity derivatives market in the emerging markets universe. In fact, the outstanding notional of equity derivative products traded on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) and the South African Futures Exchange (SAFEX) exceeded that of the KSE in mid-2001 (see Table 9 ). However, the derivatives trading volumes on JSE/SAFEX declined during the past few years, reflecting the trends in the underlying equity market, the ongoing consolidation in the banking sector and asset management industry, and the retrenchment of some foreign liquidity providers. In Latin America, the average daily trading volume of stock index derivatives at the Brazilian Bovespa is the highest in the region and is roughly similar to that of South Africa and most markets in emerging Asia (excluding Korea).

Average Daily Trading Volumes in Equity Index Derivatives in Asia

(In thousands of contracts)

The individual stock options traded in emerging markets are typically significantly less liquid than benchmark index futures and options. Although the cross-country comparisons of the outstanding notional values of single equity derivatives in emerging markets are hampered by data availability, based on the number of contracts traded, Bovespa appears to be by far the most active market for single equity derivatives in the emerging markets universe (see Table 11 ). In South Africa, single stock options exist for about 40 corporate names, but are significantly less liquid than index options. These instruments are typically launched in the OTC market and subsequently listed on the exchange.

Local equity derivatives in emerging markets are used by a wide range of market participants. Local corporates are the main users of single stock options. Asset managers, who are typically bench-marked against various indices, are the main users of stock index futures and options, while pension funds often prefer equity-linked notes. Market data for Korea indicates that domestic individual investors tend to be the most active users of stock index futures traded on local exchanges (see Figure 20 ). Similarly, around 90 percent of the futures market in Taiwan is reportedly represented by retail investors. In South Africa, both residents and nonresidents participate in the market, with foreigners at times accounting for half of the trading volume. However, in contrast with Asian markets, the retail investor base for equity derivatives in South Africa is fairly small.

KOSPI 200 Index Futures: Cumulative Net Purchases

(In millions of U.S. dollars)

Over the past two years, many derivatives exchanges around the world took measures to increase individual investor participation. Both the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKE) and the Taiwan Futures Exchange (Taifex) introduced new products targeting individual investors, such as small-sized equity index futures and also the so-called equity-linked principal protected products. 69 According to market sources, the equity-linked principal protected products market in Hong Kong SAR reached more than $1.5 billion in late 2002. Similar instruments are expected to rapidly gain popularity in Korea, where the retail investor base is larger than in Hong Kong SAR. However, more recently, some KSE officials began to voice concerns over excessively high individual investor participation in the futures market, saying that retail investors could exacerbate volatility by following the investment patterns of the better-informed foreign institutional investors. Outside Asia, many emerging market exchanges took steps to increase individual investor participation as well. For example, the Brazilian Bovespa launched the small-sized equity index contracts in September 2001.

- Credit Derivatives

Although the credit derivatives market is still a small part of the global derivatives market, it remains one of the fastest-growing segments notwithstanding several major credit events that occurred during the past few years (Russia, Argentina, and Enron). The data collected as part of the BIS Triennial Survey showed that positions in the global credit derivatives market rose to $693 billion at the end of June 2001 from $118 billion at the end of June 1998. Separately, according to the British Bankers’ Association (BBA) Credit Derivatives Report 2001/2002 (see Deutsche Bank, 2003 ), the total notional value of all credit derivatives products referencing both mature and emerging market names stood at $1,189 billion as of end-2001.

The emerging credit derivatives market mainly consists of credit protection instruments on external sovereign bonds that are traded offshore. The estimates of the size of this market range from $40 billion for the outstanding notional as of mid-2001, according to a Risk survey , to $300 billion suggested by Deutsche Bank. 70 Nonetheless, this means that the share of emerging market instruments in the global credit derivatives market is much larger than their share in other global derivatives markets. The most commonly used credit derivatives in emerging markets are credit default swaps (CDSs), credit-linked notes (CLNs), and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). 71 The sovereign CDSs are the most liquid instruments in the emerging credit derivatives market, accounting for around 85 percent of the total outstanding notional. The most actively traded contracts reference the external sovereign bonds issued by Korea, Mexico, Brazil, Russia, and Singapore. 72 A relatively few top-tier corporate credits (in Latin America, these include mainly Mexican names, such as Telmex and Cemex) are also traded in the CDS market, but these instruments are considerably less liquid and reportedly account For less than 5 percent of the emerging CDS market /ex-Asia. Compared with other regions, the CDS activity in emerging Asia has been limited by the relatively small size of the external sovereign bond market. However, the CDSs are rapidly gaining popularity, as they often provide higher market liquidity, higher returns, and longer yield curves than the U.S. dollar-denominated sovereign bonds. According to market sources, the average daily trading volume in the Asian CDS market rose to $200 million in 2002 from $100–150 million in 2001. Also, several investment banks have recently launched credit derivative index (CDI) products that allow investors to gain exposure to portfolios of credit-default swaps referencing sovereign or corporate names in emerging markets. 73

Market participants use credit default swaps for hedging against (or gaining exposure to) changes in credit spreads and default risk. Compared with bonds, the CDSs have several advantages: (1) credit default swaps allow positions in maturities for which the cash instruments are illiquid or unavailable; (2) there is typically no collateral or up-front cash payment; and (3) the credit default swaps provide investors with an opportunity to take a short position vis-à-vis a particular credit for a longer term than in the repo market, in which positions typically have to be rolled over every one-to-three months. 74 In fact, emerging market credit default swaps are often used to take exposure to sovereigns for maturities shorter than those corresponding to outstanding bonds and to express views on sovereign (default risk and on cross-country relative values (see Box 8 ).

Some emerging markets over the past few years experienced a pickup in local credit derivatives activity. In Brazil, the government has made the first steps toward developing the onshore credit derivatives markets by allowing local banks to trade credit risk. Also, the Brazilian Central Bank issued a circular outlining the accounting procedures for credit derivatives in 2001, and the Brazilian payment and settlement system for OTC markets (CETIP) launched a registration system for credit default swaps in early 2004. In Korea, there has been a notable pickup in local currency credit-linked notes referencing Korean corporate, sovereign, and quasi-sovereign credits. According to the Bank of Korea, the volume of CLNs rose to $1.2 billion in 2002 from $0.7 billion in 2001. The main attractions of CLNs for Korean investors are higher yield and longer duration compared with those offered by government and corporate bonds. In South Africa, credit derivatives activity picked up in 2000–01 amid low interest rates on government bonds, but stalled after the central bank hiked the rates. According to market sources, the credit default swaps of up to one-year maturity currently exist for only a few South African corporates. In general, the expansion of credit derivatives in emerging markets is constrained by the relatively small size and illiquidity of the local corporate bond markets as well as by the lack of standardized documentation and regulatory uncertainties regarding the treatment of credit derivatives for accounting and tax purposes. 75 Nevertheless, local banks manage to get around these problems by offering CLNs, which reference corporate bonds and promissory notes that are unlisted but traded over-the-counter. Going forward, many market analysts foresee the local credit derivatives market providing price discovery for the spot market and, thus, encouraging securitization.

Credit Default Swap Spreads in Emerging Markets

The credit default swap curve, a plot of credit default swap spreads for different maturities, conveys useful information about market views on a sovereign’s ability to honor its external debt, as well as the recovery value bond investors can obtain in case of debt default. The credit default swap curve is normally upward sloping because credit deterioration is more likely in the medium and long term than in the short term. If the sovereign is able to meet its debt repayments in the short term, changes in market perception about debt sustainability would likely result into parallel or steepening movements of the credit default swap curve. In contrast, problems associated to short-term financing needs would lead to a flattening of the credit default swap curve, as short-term spreads widen to compensate protection sellers for the increase in short-term risk. During periods of market stress, the credit default swap curve can become inverted, as in the case of Argentina during the second half of 2001, and more recently, of Brazil since June 2002.

Further information on default probabilities for a sovereign for different time horizons can be extracted using standard credit default swap valuation models. The Figure shows the evolution of one-year and two-year default probabilities for Argentina between January 1990 and December 2001. 1 The approval of an IMF package for Argentina at the end of 2000 contributed to soothe investors’ sentiment and reversed a sharp spike in default probabilities experienced in November 2000. However, increased concerns about the ability of Argentina to meet its debt payments amid continued deterioration of the country’s fiscal position, together with an uncertain political climate, caused default probabilities to creep upwards during 2001. By the end of the second half of 2001, default probabilities reached levels not observed ever before. As it became clear that no further external aid was forthcoming and that the government would refrain from implementing significant fiscal measures, default probabilities increased significantly at the end of the third quarter of 2001. By mid-December 2001, trading on Argentina default swaps stopped completely as no participant was willing to take a long position on Argentina credit risk, a position validated by Argentina’s default in January 2002.

Sovereign Credit Default Probability and EMBI+ Spread for Argentina

Credit default swaps are not the only financial instruments that contain useful information about sovereign risk, as sovereign bond spreads are also useful indicators of sovereign debt solvency. Indeed, the Figure shows the high correlation between the default probabilities implied by credit default swaps and the EMBI+ spread for Argentina. 2 However, liquidity in the cash market is more likely to dry out during periods of stress than in the credit default swap markets. In fact, there is anecdotal evidence that following the serious disruptions in the cash market clearing mechanisms in the aftermath of the events of September 11, 2001, price discovery migrated from the cash market to the credit derivatives market.

Local Derivatives Markets and Capital Flows to Emerging Economies

There is a broad consensus that the rapid expansion of derivatives products during the past 10 to 15 years was one of the key factors that facilitated the rise of global cross-border capital flows (see, for example, Garber, 1998 ; and Dodd, 2001 ). Various traditional cross-border investment vehicles, such as loans, bonds, equities, and FDI, can potentially expose both lenders and borrowers to foreign exchange risk, interest rate, market, credit, and refinancing (liquidity) risks. By allowing market participants to unbundle and redistribute these risks to those who are in a better position to manage them, derivatives make cross-border investments more attractive, thereby increasing net flows and creating more opportunities for portfolio diversification. There are many ways in which the use of derivatives by local and foreign market participants can facilitate cross-border capital flows. Here are a few examples.

Currency derivatives can be used to change the currency of denomination of asset holdings and, therefore, to hedge investments against unexpected changes in exchange rates by both foreign and local investors. Foreign investors typically use currency derivatives to hedge their long local currency exposure in emerging markets, while local entities often use the same instruments to manage foreign exchange risk associated with external financing, typically in G-3 currencies. Thus, the level of external fund-raising by local entities is directly related to the availability of the currency hedging instruments.

Another example is the basic single-currency interest-rate swap, which can allow the borrower with a floating interest rate loan/bond to hedge the interest rate risk by swapping floating rate payments for fixed-rate payments. Because interest rate swaps give borrowers an opportunity to exploit their comparative advantages for borrowing at fixed versus floating rates in different markets, they may encourage corporates or banks to seek external financing at more favorable terms instead of borrowing locally. Thus, the use of single-currency swaps can generate gross cross-border flows. In some emerging markets, most notably in Brazil, where the local corporate treasurers’ benchmark is a floating local currency interest rate, whereas funds raised internationally are typically at a fixed U.S. dollar rate, interest rate swaps have become central to the ability of local entities to manage the risks associated with foreign borrowing.

Finally, credit derivatives represent another class of instruments that can potentially increase net flows into emerging markets. An attractive feature of credit derivatives is that they allow investors/lenders to manage the default/bankruptcy risks without having to buy or sell the underlying securities. For example, a foreign bank can reduce its credit exposure to a particular client without physically removing assets from its balance sheet and thus effectively separate relationship management from risk management Some market analysts argue that if international banks could use onshore credit derivatives in emerging markets, they would be more willing to maintain or increase their exposure to local corporate clients.

- Local Participation

Local entities with foreign exchange exposures are typically among the most active users of derivatives in emerging markets. Given that domestic Financial markets in many emerging economies are not deep enough for large local corporates to borrow long term and in large size, domestic companies often have to rely on international bond or syndicated loan markets for this type of funding. Thus, when the local corporate sector has a positive net external financing requirement, the development of the onshore derivatives markets becomes a critical factor in facilitating external fund-raising. Of course, in the case when emerging market companies with the internationally diversified production (for example, the South African mining companies) limit their foreign currency borrowing strictly to financing those operations that earn income in the same currency, there may not be much need for foreign currency hedging. However, this financing decision may not necessarily be optimal, given the relative costs of funds (domestic versus external), and may be due to either the unavailability or the high cost of hedging instruments. The latter should be improving as the emerging derivatives markets become more mature.

The relative importance of derivatives for local entities’ fund-raising in international markets varies across emerging economies. In Emerging Europe and Asia, this link is not as strong as in Latin America. Following the Asian crisis, many countries in emerging Asia shifted toward relying more on local currency financing. In addition, many of these countries are running current account surpluses and thus do not have positive net external financing requirements. In emerging Europe, local entities are still constrained by regulatory restrictions on the use of derivatives. By contrast, in Brazil, the link between fund-raising in international markets and derivatives activity has been particularly strong (see Figure 21 ). Virtually all local companies that have access to international financial markets raise U.S. dollar-denominated funds and then turn to the local derivatives market to swap the external financing obligations into reals with an interest rate indexed to the overnight (GDI) rate. Historically, the cost of U.S. dollar hedges in Brazil was fairly high due to the shortage of hedging instruments, as most domestic institutional investors did not have foreign currency positions (in contrast to the Chilean pension funds) and many exporters with the U.S. dollar receivables typically had overall net short U.S. dollar positions. As a result, Brazilian corporates tended to invest part of their cash reserves in U.S. dollar-denominated securities in order to provide at least partial protection against an adverse exchange rate move. In 1999, the Brazilian Central Bank (BCB) stepped in as the main provider of currency hedge to the market through the issuance of U.S. dollar linked securities. Furthermore, in March 2002, the BCB decided to split the exchange rate linked instruments into real -denominated bonds and foreign exchange swaps in order to lower its debt rollover costs and also to reduce the cost of currency hedging for local entities. 76

International Bond and Loan Issuance and Derivatives Trading Volume in Brazil

The development of the domestic credit derivatives markets in emerging economies can facilitate a more accurate pricing of corporate credit risk and help to attract foreign capital flows going forward. Many analysts believe that since local market participants are more familiar with local credit risk and less concerned about market liquidity than foreign investors, they are “natural” sellers of credit protection on emerging market corporate risk. At the same time, the domestic financial institutions that already have exposure to local corporate credit risk (in the form of bonds, loans, and receivables) are in a better position to structure products that match local investors’ preferences for credit risk than foreign banks. Thus, local market participants can play a key role in the development of the domestic market for corporate credit risk protection. Of note is the fact that local institutional investors, particularly pension funds and insurance companies, have been gradually increasing their use of CLNs and structured products.

- Foreign Participation

Foreign investors in emerging markets generally include banks, corporates, “real money” accounts (both dedicated and cross-over investment funds), and speculative money accounts (hedge funds and proprietary trading desks of investment and commercial banks). Compared with local entities, the foreign investors’ participation in the emerging derivatives markets is fairly limited. Mexico, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic have seen a considerable demand by international investors for long-term interest rate and local currency exposures that was driven in part by the so-called “convergence trades,” with exposures established in both cash and derivatives markets. 77 As far as the OTC markets are concerned, the extent of foreign investor participation (both as final users of the derivative products as well as intermediaries) varies. In some countries, such as Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, and South Africa, foreign dealers account for the bulk of the turnover in the OTC markets, while in other countries, most of the trading goes through domestic dealers.

Both anecdotal evidence and industry surveys suggest that “real money” funds hedge relatively little of their risk exposures in emerging markets, either because of internal restrictions on leveraged positions or because these risk exposures are desirable. A survey of derivatives usage by U.S. institutional investors conducted by the NYC Stern School of Business in 1998 ( Hayt and Levich, 1999 ) showed that only 46 percent of respondents were permitted to use derivatives by their investment mandate, and only 27 percent of respondents had open derivatives positions at the time of the survey. Because many emerging market countries maintain various restrictions on foreign participation in local derivatives markets, one would expect that the percentage of the emerging market funds using local derivatives to hedge various risk exposures is even lower.

Even when there are no restrictions on foreign participation in emerging derivatives markets, foreign investors (equity investors, in particular) often prefer to take outright foreign currency exposure. Thus, one would not expect to find a strong link between foreign inflows and derivatives activity even in those emerging markets, where foreign participation is significant. Indeed, our analysis of foreign institutional investors’ purchases of stocks in Brazil, Korea, Taiwan Province of China, and South Africa and the trading volumes in the onshore currency and equity derivatives markets suggests that there is no statistically significant relationship between foreign purchases of shares and derivatives’ trading volumes in these countries. 78 It should be noted that in some emerging markets, local equities are a “natural hedge” against the foreign exchange risk (for example, in South Africa, the share prices of mining companies with dollar receivables are often referred to as “rand hedges”). Unlike equity investors, bond investors sometimes do hedge their long local-currency bond exposures in emerging markets. Also, in those emerging markets where bond repo markets are sufficiently liquid, foreign investors often prefer to repo bonds instead of purchasing bonds outright and simultaneously hedging the foreign exchange risk with derivatives.

In contrast with the “real money” accounts, speculative investors can use derivatives freely for hedging risks associated with their cash market positions or for gaining leveraged returns or for exploiting relative value opportunities between the cash and derivatives markets. However, according to Credit Suisse First Boston/Tremont, the leading provider of the hedge fund indices, the hedge funds that invest in emerging markets often employ a long-only strategy because “many emerging markets do not allow short selling, nor offer viable futures or other derivative products with which to hedge.” 79 In contrast to many other emerging markets, foreigners were the dominant players in the South African foreign exchange and interest rate swap markets until late 2001 (see Figure 16 ), using derivatives either to bet on their currency and interest rate views or to proxy-hedge the emerging market risk (with the latter due to the rand being one of the most liquid currencies in the emerging markets universe).

Both leveraged investors and dedicated emerging market debt funds are active participants in the credit derivatives markets for emerging market U.S. dollar-denominated bonds. The main protection sellers in credit derivatives markets are the major internationally active banks. Hedge funds have been active users of emerging market credit derivatives, mainly focusing on trading the basis between default swaps and bonds amid increased volatility in emerging debt markets. 80 The “convertible arbitrage” funds have also been among the active buyers of credit protection, using credit default swaps to strip the credit component from the equity option of convertible bonds. The main features of credit derivatives that make them particularly attractive for hedge funds are: they provide an efficient way to short a credit with a relatively low risk of a short squeeze, and they are better instruments for structuring any relative value trading strategies than bonds because they allow better alignment between maturities of different credit exposures. However, for “real money” accounts, CLNs represent a more viable investment alternative than CDSs, since these funds are typically allowed to invest only in cash instruments. 81 Since the ability of foreign investors to manage the emerging market corporate default risk remains limited due to the relatively underdeveloped state of the corporate credit default markets), many emerging market borrowers are forced to issue bonds with various credit enhancements, particularly when the perceived credit risk is high (see Chapter V of IMF, 2002a ).

The Role of Derivatives in Emerging Market Crises

While derivatives do play a positive role by reallocating risks and facilitating growth of capital flows to emerging markets, they can also allow market participants to take on excessive leverage, avoid prudential regulations, and manipulate accounting rules when financial supervision and internal risk management systems are weak or inadequate. In particular, the use (or rather misuse) of derivatives can potentially allow financial institutions to move certain exposures off balance sheets, thereby magnifying their balance sheet mismatches in ways that may not be easily detected by prudential supervisors and, as a result, may lead to a gradual buildup of financial system fragilities. Also, due to their very nature (i.e., the fact that they allow market participants to establish leveraged positions), derivative instruments tend to amplify volatility in asset markets. Thus, a negative shock to a country with already weak economic fundamentals, which typically triggers a sell-off in local asset markets, can also lead to an unpredictable and rapid unwinding of derivatives positions that can in turn accelerate capital outflows and deepen the crisis.

This section will discuss the role of derivatives in several emerging market crises focusing mainly on two issues: the types or financial derivatives used by market participants before the onset of a crisis and how the use of these instruments affected the stability of the domestic financial system; and the impact of the unwinding of derivatives positions on the crisis dynamics after the onset of a crisis. While the Mexican and Asian crises highlighted the role of structured notes and swaps in magnifying balance sheet mismatches and the associated volatility in foreign exchange markets, the Russian and Argentine crises demonstrated the importance of counterparty risk and spillovers through credit markets. It should be pointed out that deteriorating fundamentals—mostly fiscal, but also financial in the case of Asia—were the main causes of the recent emerging market crises, but derivatives amplified the impact of these crises on financial systems of emerging market economies. It should also be noted that the analysis of the role of derivatives in emerging market crisis is seriously hampered by data availability, since the OTC derivatives transactions are not reported systematically. Thus, in many cases, anecdotal evidence and reported (ex post) losses on derivatives positions by major investment banks of the industrial countries are the main sources of information.

- The Mexican Crisis, 1994

In the early 1990s, the recently privatized Mexican banks engaged in an aggressive building up of their on- and off-balance sheet positions, which led to an increase of their credit and market risk exposures well beyond prudential limits. In particular, they used various derivatives to achieve leveraged returns. One of the popular instruments that allowed local banks to leverage their holdings of the exchange rate linked treasury bills (the Tesobonos) was a tesobono swap ( Garber, 1998 ). In a tesobono swap, a Mexican bank received the tesobono yield and paid U.S. dollar LIBOR plus X basis points to an offshore counterparty, which in turn hedged its swap position by purchasing tesobonos in the spot market. The only transactions that were recorded in the balance of payments were; an outflow of bank deposits related to the payment of collateral by the Mexican bank, and a U.S. dollar inflow related to the purchase of tesobonos by the foreign investor. Thus, traditional balance of payments accounting provided a misguided representation of capital flows and associated risks—that is, although it appeared that the foreign investor had a long position in government bonds, it was in fact the local bank that bore the tesobono risk, while the foreign investor was effectively providing a short-term dollar loan. Tesobono swaps were not the only instruments that allowed local banks to establish leveraged positions financed by short-term U.S. dollar loans from their offshore counterparties; other instruments included various structured notes and equity swaps. 82

At the onset of the crisis and in the face of rising political uncertainty and weakening fundamentals that ultimately forced the authorities to float the peso, the tesobono yields jumped from 8 percent to 24 percent. As a result, the U.S. dollar value of the collateral fell, triggering margin calls on Mexican banks. Quoting market sources, Garber (1998) suggested that the total of margin calls on tesobono and total return swaps was about $4 billion, adding to the pressure on the Mexican peso foreign exchange market. 83

- The Asian Crises, 1997–98

As in the Mexican crisis, unhedged currency and interest rate exposures were key determinants of the severity and scope of the Asian crises (see IMF, 1998a ). Banks and non-financial corporations in Asia left their exposures unhedged because (1) domestic interest rates were higher than foreign interest rates, (2) the pegged exchange rates were generally perceived as stable, and (3) domestic hedging products were underdeveloped, while offshore hedges were expensive. Because of these factors, foreign banks were eager to lend to East Asian banks that tried to capture carry profits on the interest rate differentials. However, local prudential regulations, such as restrictions on the net open foreign exchange exposures and risk-to-capital ratios, limited the amount of profitable arbitrage trade. Therefore, Asian financial institutions turned to derivatives “to avoid prudential regulations by taking their carry positions off balance sheet” ( Dodd, 2001 , p. 10).

According to market sources, the majority of losses reported by both U.S. and European banks on their Asian lending were listed as due to swap contracts, with the latter presumably including both total return swaps and currency swaps ( Kregel, 1998 ). In a total return swap, one counterparty pays the other the cash flows (both capital appreciation and interest payments computed on a mark-to-market basis) generated by some underlying asset (equity, bond, or loan) in exchange for dollar LIBOR plus X basis points. Thus, the flows between Asian financial institutions and foreign counterparties were similar to those in the tesobono swap described above. As in the case of tesobono swaps, offshore counterparties were buying the underlying assets to hedge their swap positions, while local banks were left with short U.S. dollar positions. After weakening fundamentals led to a collapse of the exchange rate peg and domestic interest rates rose, both counterparties had incentives to either unwind the swaps or hedge their foreign exchange exposures, which exacerbated the sell-off in Asian assets and currencies. 84

- Russia’s Default and Devaluation, 1998

Although the poor state of Russia’s fiscal accounts was well known by mid-1998, the announcement of a 90-day moratorium on external debt payments on August 17, 1998 caught most market participants by surprise. At the time of the default and devaluation, the estimates of the outstanding notionals of the U.S. dollar-ruble NDF contracts ranged from $10 billion to $100 billion, and the total foreign exposure to the domestic bond market (GKO/OFZs) was around $20 billion. According to market sources, the U.S. dollar-ruble foreign exchange forwards with Russian firms as counterparties were the largest source of credit losses by major swap dealers during 1997–98, exceeding the losses made on their Asian lending. The events in Russia highlighted the presence of convertibility risk even when local currency positions in emerging markets were hedged, and raised the issue of the NDF valuation when an official rate was not available. In addition, Russia’s default sent shock waves through the credit derivatives markets, with the cost of protection increasing in all sectors, including the investment-grade segment. Ambiguous and often misleading definitions of reference obligations, credit events, and settlement mechanics made it difficult for protection buyers to enforce the contracts. According to dealers, there was initially some confusion about which event had to trigger the credit default swap contracts—the declaration of the moratorium on debt payments or the actual default on obligations. In addition, it was unclear whether the CDS contracts that did not explicitly include cross-default clauses with the already restructured Soviet-era debt obligations (PRINs and IANs) had to be triggered by a default on these bonds. In order to address the legal issues highlighted during the Russian crisis, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) issued new credit derivative documentation guidelines in 1999. 85

- Argentina’s Default and Devaluation, 2001

In contrast with the Russian crisis, the Argentine default and devaluation in December 2001 were widely anticipated and occurred at a time when the credit derivatives market was relatively more mature. The protracted recession and gradual deterioration of the sovereign’s credit quality gave market participants sufficient time to exit the bond and credit protection markets and also allowed the main sellers of credit protection on Argentine sovereign bonds (broker-dealers) to hedge their books in the repo market. The liquidity in the Argentine CDS market dried up in August-September 2001, following a bout of volatility in July. The announcement of the moratorium on all debt payments on December 23, 2001 was unanimously accepted as a “repudiation/moratorium” credit event consistent with the ISDA definitions. There were, reportedly, some disputes as to which bonds could be considered as “deliverable,” but they have been resolved fairly quickly. According to market sources, 95 percent of all credit default swaps were settled by mid-February 2002 and there were no reported failures to deliver, with the total notional amount of credit protection outstanding at the end of November 2001 estimated at $10–15 billion (see Deutsche Bank, 2003 ). 86

- Concluding Remarks

Local derivatives markets in emerging economies have grown rapidly over the past few years, especially in countries that have removed capital controls and have developed their underlying securities markets. The growing use of derivative products by emerging market participants has also supported capital inflows and has helped investors to price and manage the risks associated with investing in emerging markets more efficiently. However, the use of derivatives has also made crisis dynamics in some recent episodes more unpredictable by accelerating capital outflows, amplifying volatility, and, in some cases, increasing the correlation between asset and currency markets. In many of these episodes, the negative impact of derivatives on crisis dynamics was either clue to the immaturity of local derivatives markets or due to weak prudential supervision, which allowed some financial institutions to build up leveraged positions before the onset of a crisis. The policy implications of the trends described in this chapter were discussed in a broader context of the development of local securities markets in Chapter I .

Within Same Series

- CHAPTER IV OVER-THE-COUNTER DERIVATIVES MARKETS

- II Developments, Trends, and Issues in the Mature Financial Markets

- CHAPTER I LOCAL SECURITIES AND DERIVATIVES MARKETS IN EMERGING MARKETS: SELECTED POLICY ISSUES

- Annex I Major Capital Markets: Trends and Recent Developments

- CHAPTER II DEVELOPMENTS AND TRENDS IN MATURE CAPITAL MARKETS

- IV Developments and Trends in Mature Financial Markets

- II The Asian Crisis: Capital Markets Dynamics and Spillover

- CHAPTER III EMERGING MARKET FINANCING

- II Developments and Trends in the Mature Markets

- III Emerging Markets: The Contraction in External Financing and Its Impact on Financial Systems

Other IMF Content

- CHAPTER IV SELECTED TOPIC: THE ROLE OF FINANCIAL DERIVATIVES IN EMERGING MARKETS

- Mexico: Financial Sector Assessment Program Update: Technical Note: Derivatives Market: Overview and Potential Vulnerabilities

- III OTC Derivatives Markets: Size, Structure, and Business Practices

- United States: Publication of Financial Sector Assessment Program Documentation: Technical Note on Regulatory Reform: OTC Derivatives

- CHAPTER IV INSTITUTIONAL INVESTORS IN EMERGING MARKETS

- Chapter IV: Local Securities and Derivatives Markets in Emerging Markets: Selected Policy Issues

- The Derivatives Market in South Africa: Lessons for Sub-Saharan African Countries

- V Key Features of OTC Derivatives Activities

- Derivative Market Competition: OTC Versus Organized Derivative Exchanges

- CHAPTER II GLOBAL FINANCIAL MARKET DEVELOPMENTS

Other Publishers Content

Asian development bank.

- The Influence of US Dollar Funding Conditions on Asian Financial Markets

- Developing a Local Currency Government Bond Market in an Emerging Economy after COVID-19: Case for the Lao People's Democratic Republic

- How Does Inflation in Advanced Economies Affect Emerging Market Bond Yields? Empirical Evidence from Two Channels

- Asia Bond Monitor: March 2023

- Exchange Rates and Insulation in Emerging Markets

- Update on Financial Market Infrastructures in ASEAN+3

- Fed Tightening and Capital Flow Reversals in Emerging Markets: What Do We Know?

- Asia Bond Monitor - September 2023

- The Impact of Nonperforming Loans on Cross-Border Bank Lending: Implications for Emerging Market Economies

- The Role of Central Bank Digital Currencies in Financial Inclusion: Asia-Pacific Financial Inclusion Forum 2022

Inter-American Development Bank

- Financial Risk Management: A Practical Approach for Emerging Markets

- Maturity Mismatch and Financial Crises: Evidence from Emerging Market Corporations

- The Determinants of Corporate Risk in Emerging Markets: An Option-Adjusted Spread Analysis

- Institutional Investors, Pension Reform and Emerging Securities Markets

- A Proposed Fuel Price Stabilization Mechanism through the Use of Financial Derivatives

- Signaling Creditworthiness in Peruvian Microfinance Markets: The Role of Information Sharing

- Global Factors and Emerging Market Spreads

- The Politics of Financial Development: The Role of Interest Groups and Government Capabilities

- Monetary Policy Challenges in Emerging Markets: Sudden Stop, Liability Dollarization, and Lender of Last Resort

- Credit Frictions and "Sudden Stop" in Small Open Economies: An Equilibrium Business Cycle Framework for Emerging Markets Crises

The World Bank

- The structure of derivatives exchanges: lessons from developed and emerging markets

- The Growing Role of the Euro in Emerging Market Finance

- What Determines Entrepreneurial Outcomes in Emerging Markets?: The Role of Initial Conditions

- The Effects of Derivatives Regulation on Infrastructure Finance: Some Evidence from Emerging Markets

- Firm Innovation in Emerging Markets: The Roles of Governance and Finance

- The Role of Major Emerging Markets in Global Commodity Demand

- An introduction to the microstructure of emerging markets

- Mortgage securities in emerging markets

- Why Banks in Emerging Markets Are Increasingly Providing Non-financial Services to Small and Medium Enterprises

- Financial Stability Issues in Emerging Market and Developing Economies

Table of Contents

- Front Matter

- CHAPTER II EMERGING LOCAL BOND MARKETS

- CHAPTER III EMERGING EQUITY MARKETS

- CHAPTER IV THE ROLE OF FINANCIAL DERIVATIVES IN EMERGING MARKETS

- Back Matter

- View raw image

- Download Powerpoint Slide

Allen , Franklin , and Douglas Gale , 2000 , Comparing financial Systems ( Cambridge, Mass .; MIT Press ).

- Search Google Scholar

- Export Citation

Bank for International Settlements , 2002a , The Development, of Bond Markets in Emerging Economies , BIS Papers No. 11 ( Basel ; BIS ).

Bank for International Settlements , 2002b , Triennial Central Bank Survey: Foreign Exchange and Derivatives Market Activity in 2001 , March .

Bank for International Settlements , 2002c , Quarterly Review , June .

Barham , John , 2001 , “A Compromise Solution,” Latin Finance ( October ), pp. 40 – 43 .

Beck , Thorsten , and Ross Levine , 2001 , “Stock Markets, Banks and Growth; Correlation or Causality?” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2760 ( Washington : World Bank , September ).

Brooks , Robin , and Luis Catao , 2001 , “The New Economy and Global Stock Returns,” IMF Working Paper No. 00/216 ( Washington : International Monetary Fund ).

Bubula , Andrea , and Inci Ötker-Robe , 2002 , “The Evolution of Exchange Rate Regimes Since 1990: Evidence from De Facto Policies,” IMF Working Paper No. 02/155 ( Washington : International Monetary Fund ).

Buniside , Craig , Martin Eichenbaum , and Sergio Rebelo , 2001 , “Hedging and Financial Fragility in Fixed Exchange Rate Regimes , European Economic Review , Vol. 45 ( June ), pp. 1151 – 93 .

Caballero , Ricardo , 2002 , “Coping with Chile’s External Vulnerability: A Financial Problem,” in Economic Growth: Sources, Trends, and Cycles , ed. by Norman Loayza and Raimundo Soto ( Santiago, Chile : Central Bank of Chile ).

Norman Loayza and Raimundo Soto , and Arvind Krishnarmurthy , 2003 , “Excessive Dollar Debt: Financial Development and Underinsurance,” Journal of Finance , Vol. 58 ( April ), pp. 867 – 93 .

Calvo , Guillermo A. , 1998 , “Capital Flows and Capital Market Crises: The Simple Economics of Sudden Stops,” Journal of Applied Economics , Vol. 1 ( November ), pp. 35 – 54 .

Calvo , Guillermo A. , 1999 , “Contagion in Emerging Markets: When Wall Street Is the Carrier,” Available on the Internet at http://www.bsos.umd.edu/econ/ciecalvo.htm .

Calvo , Guillermo A. , 2000 , “Capital Markets and the Exchange Rate; With Special Reference to the Dollarization Debate in Latin America,” ( unpublished : Center for International Economics , University of Maryland ).

Calvo , Guillermo A. , and Carmen M. Reinhart , 2000 , “When Capital Inflows Suddenly Stop: Consequences and Policy Options,” in Reforming the International Monetary and Financial System , ed. by Peter B. Kenen and Alexander K. Swoboda ( Washington : International Monetary Fund ).

Campbell , John Y , and Robert Shiller , 1996 , “A Scoreeard for Indexed Government Debt,” in NBER Macroeconomics Annual ( Cambridge : MIT Press ).

Cervera , Alonso , and Audra Quedry , 2003 , “Polling Mexico’s Pension Funds,” Credit Suisse First Boston (CSFB) Emerging Market Economics .

Cha , Hyeon-Jin , 2002 , “Analysis of the Sluggish Development of the Secondary Market for Korean Government Bonds, and Some Proposals” ( unpublished ; Seoul : The Bank of Korea, Financial Markets Department , May ).

Chan-Lau , Jorge , and Amadou Sy , forthcoming , “A Comparative Study of Sovereign Risk Measures , IMF Working Paper ( Washington : International Monetary Fund ).

Choe , Hyuk , Bong-Chan Kho , and Rene M. Stulz , 1999 , “Do Foreign Investors Destabilize Stock Markets? The Korean Experience in 1997.” Journal of Financial Economics , Vol. 54 ( October ), pp. 227 – 64 .

Cifuentes , Rodrigo , Jorge Desormeaux , and Claudio Gonzalez , 2002 , “Capital Markets in Chile: from Financial Repression to Financial Deepening,” in BIS Papers No. 11 , ( Basel : BIS ).

Claessens , Stijn , Simeon Djankov , and Larry H.P. Lang , 1998 , “Who Controls East Asian Corporations?” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2054 ( Washington ; World Bank ).

Claessens , Stijn , Daniela Klingebiel , and Sergio L. Schmukler , 2002 , “Explaining the Migration of Stocks from Exchanges in Emerging Economies to International Centers,” World Institute for Development Economic Research (WIDER) Discussion Paper No. WOP 2002/94 . ( Helsinki : United Nations University—WIDER ).

Clement , Douglas , 2001 , “The Vanishing Equity Premium,” The Region , Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis ( June ).

Constantinides , George , John B. Donaldson , Rajnish Mehra , 2002 , “Junior Can’t Borrow: A New Perspective of the Equity Premium Puzzle,” Quarterly Journal of Economics , Vol. 117 , ( February ), pp. 269 – 96 .

Credit Suisse First Boston/Tremont website: http://www.tremont.com .

Davies , Ben , 2002 , “Equity Research—In Crisis?” Asia Money ( November ).

Deutsche Bank , 2000 , “CE-3 Domestic Bond Markets,” Global Markets Research .

Deutsche Bank , 2001a , “Emerging Market Credit Derivatives,” Global Markets Research .

Deutsche Bank , 2001b , “The Malaysian Bond Market,” Global Markets Research .

Deutsche Bank , 2003 , “Emerging Markets Credit Derivatives” ( May ).

Dodd , Randall , 2001 , “The Role of Derivatives in the East Asian Financial Crisis,” Economic Strategy Institute , The Derivatives Study Center , http://www.econstrat.org .

Dooley , Michael , 1996 , “A Survey of the Literature on Controls over International Capital Transactions,” IMP Staff Papers , International Monetary Fund . Vol. 43 , ( December ), pp. 639 – 87 .

Dooley , Michael , 2000 , “A Model of Crises in Emerging Markets,” The Economic Journal , Vol. 110 ( January ), pp. 256 – 72 .

Duffie , Darrell , 1999 , “Credit Swap Valuation,” Financial Analyst Journal , Vol. 55 ( January/February ), pp. 73 – 87 .

Eichengreen , Barry , and Ricardo Hausmann , 1999 , “Exchange Rates and Financial Fragility,” NBER Working Paper No. 7418 ( Cambridge, Mass. : National Bureau of Economic Research ).

Eichengreen , Barry , and Ricardo Hausmann , and Ugo Panizza , 2002 , “Original Sin: The Pain, the Mystery, and the Road to Redemption” paper presented at the IDB Conference, “Currency and Maturity Matchmaking: Redeeming Debt from Original Sin ( November ).

Emerging Markets Investor , 2001 , “Thinking Global, Buying Local.” Vol. 8 ( September ), Issue 8 .

Euroweek , 2001 , “Converging Europe and Domestic Bond Markets” ( September ) Supplement .