Research articles

Tislelizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy as first line treatment for advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma, epidural analgesia during labour and severe maternal morbidity, exposure to antibiotics during pregnancy or early infancy and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders, clinical and healthcare use outcomes after cessation of long term opioid treatment due to prescriber workforce exit, effect of the hpv vaccination programme on incidence of cervical cancer by socioeconomic deprivation in england, long acting progestogens vs combined oral contraceptive pill for preventing recurrence of endometriosis related pain, ultra-processed food consumption and all cause and cause specific mortality, comparative effectiveness of second line oral antidiabetic treatments among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus, efficacy of psilocybin for treating symptoms of depression, reverse total shoulder replacement versus anatomical total shoulder replacement for osteoarthritis, effect of combination treatment with glp-1 receptor agonists and sglt-2 inhibitors on incidence of cardiovascular and serious renal events, prenatal opioid exposure and risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in children, temporal trends in lifetime risks of atrial fibrillation and its complications, antipsychotic use in people with dementia, predicting the risks of kidney failure and death in adults with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease, impact of large scale, multicomponent intervention to reduce proton pump inhibitor overuse, esketamine after childbirth for mothers with prenatal depression, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist use and risk of thyroid cancer, use of progestogens and the risk of intracranial meningioma, delirium and incident dementia in hospital patients, derivation and external validation of a simple risk score for predicting severe acute kidney injury after intravenous cisplatin, quality and safety of artificial intelligence generated health information, large language models and the generation of health disinformation, 25 year trends in cancer incidence and mortality among adults in the uk, cervical pessary versus vaginal progesterone in women with a singleton pregnancy, comparison of prior authorization across insurers, diagnostic accuracy of magnetically guided capsule endoscopy with a detachable string for detecting oesophagogastric varices in adults with cirrhosis, ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes, added benefit and revenues of oncology drugs approved by the ema, exposure to air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular diseases, short term exposure to low level ambient fine particulate matter and natural cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory morbidity, optimal timing of influenza vaccination in young children, effect of exercise for depression, association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with cardiovascular disease and all cause death in patients with type 2 diabetes, duration of cpr and outcomes for adults with in-hospital cardiac arrest, clinical effectiveness of an online physical and mental health rehabilitation programme for post-covid-19 condition, atypia detected during breast screening and subsequent development of cancer, publishers’ and journals’ instructions to authors on use of generative ai in academic and scientific publishing, effectiveness of glp-1 receptor agonists on glycaemic control, body weight, and lipid profile for type 2 diabetes, neurological development in children born moderately or late preterm, invasive breast cancer and breast cancer death after non-screen detected ductal carcinoma in situ, all cause and cause specific mortality in obsessive-compulsive disorder, acute rehabilitation following traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation, perinatal depression and risk of mortality, undisclosed financial conflicts of interest in dsm-5-tr, effect of risk mitigation guidance opioid and stimulant dispensations on mortality and acute care visits, update to living systematic review on sars-cov-2 positivity in offspring and timing of mother-to-child transmission, perinatal depression and its health impact, christmas 2023: common healthcare related instruments subjected to magnetic attraction study, using autoregressive integrated moving average models for time series analysis of observational data, demand for morning after pill following new year holiday, christmas 2023: christmas recipes from the great british bake off, effect of a doctor working during the festive period on population health: experiment using doctor who episodes, christmas 2023: analysis of barbie medical and science career dolls, christmas 2023: effect of chair placement on physicians’ behavior and patients’ satisfaction, management of chronic pain secondary to temporomandibular disorders, christmas 2023: projecting complete redaction of clinical trial protocols, christmas 2023: a drug target for erectile dysfunction to help improve fertility, sexual activity, and wellbeing, christmas 2023: efficacy of cola ingestion for oesophageal food bolus impaction, conservative management versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in adults with gallstone disease, social media use and health risk behaviours in young people, untreated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and cervical cancer, air pollution deaths attributable to fossil fuels, implementation of a high sensitivity cardiac troponin i assay and risk of myocardial infarction or death at five years, covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against post-covid-19 condition, association between patient-surgeon gender concordance and mortality after surgery, intravascular imaging guided versus coronary angiography guided percutaneous coronary intervention, treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in men in primary care using a conservative intervention, autism intervention meta-analysis of early childhood studies, effectiveness of the live zoster vaccine during the 10 years following vaccination, effects of a multimodal intervention in primary care to reduce second line antibiotic prescriptions for urinary tract infections in women, pyrotinib versus placebo in combination with trastuzumab and docetaxel in patients with her2 positive metastatic breast cancer, association of dcis size and margin status with risk of developing breast cancer post-treatment, racial differences in low value care among older patients in the us, pharmaceutical industry payments and delivery of low value cancer drugs, rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin in adults with coronary artery disease, clinical effectiveness of septoplasty versus medical management for nasal airways obstruction, ultrasound guided lavage with corticosteroid injection versus sham lavage with and without corticosteroid injection for calcific tendinopathy of shoulder, early versus delayed antihypertensive treatment in patients with acute ischaemic stroke, mortality risks associated with floods in 761 communities worldwide, interactive effects of ambient fine particulate matter and ozone on daily mortality in 372 cities, association between changes in carbohydrate intake and long term weight changes, future-case control crossover analysis for adjusting bias in case crossover studies, association between recently raised anticholinergic burden and risk of acute cardiovascular events, suboptimal gestational weight gain and neonatal outcomes in low and middle income countries: individual participant data meta-analysis, efficacy and safety of an inactivated virus-particle vaccine for sars-cov-2, effect of invitation letter in language of origin on screening attendance: randomised controlled trial in breastscreen norway, visits by nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the usa, non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and oesophageal adenocarcinoma, venous thromboembolism with use of hormonal contraception and nsaids, food additive emulsifiers and risk of cardiovascular disease, balancing risks and benefits of cannabis use, promoting activity, independence, and stability in early dementia and mild cognitive impairment, effect of home cook interventions for salt reduction in china, cancer mortality after low dose exposure to ionising radiation, effect of a smartphone intervention among university students with unhealthy alcohol use, long term risk of death and readmission after hospital admission with covid-19 among older adults, mortality rates among patients successfully treated for hepatitis c, association between antenatal corticosteroids and risk of serious infection in children, follow us on, content links.

- Collections

- Health in South Asia

- Women’s, children’s & adolescents’ health

- News and views

- BMJ Opinion

- Rapid responses

- Editorial staff

- BMJ in the USA

- BMJ in South Asia

- Submit your paper

- BMA members

- Subscribers

- Advertisers and sponsors

Explore BMJ

- Our company

- BMJ Careers

- BMJ Learning

- BMJ Masterclasses

- BMJ Journals

- BMJ Student

- Academic edition of The BMJ

- BMJ Best Practice

- The BMJ Awards

- Email alerts

- Activate subscription

Information

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Transforming Clinical Research to Meet Health Challenges

- 1 Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

The COVID-19 pandemic made “clinical trials” a household phrase, highlighting the critical value of clinical research in creating vaccines and treatments and demonstrating the need for large-scale, well-designed, and rapidly deployed clinical trials to address the public health emergency. As the largest public funder of clinical trials, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) launched a high-level effort to absorb the lessons of the pandemic and to assess and build on ongoing initiatives to improve efficiency, accountability, and transparency in clinical research.

Read More About

Wolinetz CD , Tabak LA. Transforming Clinical Research to Meet Health Challenges. JAMA. 2023;329(20):1740–1741. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.3964

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Research shows GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs are effective but come with complex concerns

Drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro have been around for years, but they’ve recently been making headlines due to a rise in popularity as weight loss agents. They all belong to a class of drugs known as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), which mimic a hormone (GLP-1) in the body that helps control insulin and blood glucose levels and promotes feelings of satiety.

These drugs are extremely effective for blood glucose control and weight management, which, combined with their relatively limited side effect profile, makes them very appealing for diabetes treatment — the purpose for which they originally received FDA approval.

However, off-label use fueled by celebrities and social media is a growing concern. And even when physicians are prescribing GLP-1RAs for their intended uses, it’s not a magic formula — there are complex considerations such as dosages, costs, side effects and comparisons between specific drugs.

“The current fervor for GLP-1RAs in the capital markets as well as in the general public, especially in terms of weight reduction, is probably going to result in overuse,” said Chun-Su Yuan, MD, PhD , the Cyrus Tang Professor of Anesthesia and Critical Care at the University of Chicago. “This should raise a red flag.”

Living up to the hype

While experts caution against overusing GLP-1RAs or viewing them as a universal cure-all for obesity, physicians and researchers agree that the drugs are highly effective for weight management and Type 2 diabetes treatment.

“Some other treatments for Type 2 diabetes can actually cause weight gain, whereas GLP-1RA drugs effectively control blood glucose levels while also reducing body weight,” Yuan said.

Yuan and a group of other researchers recently published a paper comparing the effectiveness of different GLP-1RAs. Different drugs performed better in different areas, but all 15 GLP-1RAs they analyzed were very successful in lowering blood glucose and achieving weight loss. They also identified some secondary benefits, such as lowering cholesterol.

Similarly, Eric Polley, PhD , a UChicago data science and public health expert, recently led a study published in Nature Cardiovascular Research that used statistical modeling to simulate a clinical trial comparing the effects of four different classes of diabetes medication in patients with moderate cardiovascular risk. GLP-1RA drugs came out on top, not only controlling blood glucose and weight but also reducing the risk of major heart-related events and the risk of death overall.

Not a silver bullet: making nuanced decisions for each patient

However, GLP-1RAs are not universally effective for all patients, and Yuan said that even after deciding to prescribe this drug class, physicians should consider multiple factors when selecting a specific drug and dosage. For example, co-morbid conditions like hyperlipidemia could tip the scale and make one drug more suitable for a specific patient.

Polley pointed out that even patients with similar clinical profiles might prioritize different aspects of their health or quality of life.

“If cardiovascular health is what you think is important for deciding between these drug classes, I think our most recent study provides some strong evidence. But if there are other outcomes that your patient is concerned about, then you have to consider the effect size for those other outcomes,” Polley said. He and other experts are working on subsequent research examining the effects of different diabetes treatments on other health outcomes and concerns, including a patient’s risk of cancer, blindness or amputation.

Another key consideration is side effects, which can vary significantly from patient to patient. While Yuan’s recent study confirmed the efficacy of GLP-1RAs, the researchers also found that some patients did experience adverse side effects, especially related to gastrointestinal issues like nausea and vomiting. They highlighted the need to consider potential tradeoffs between efficacy and side effects, finding that higher doses can have stronger efficacy but also induce more severe side effects.

“It’s also important to note that the long-term side effects of these drugs are not yet well-studied,” Yuan said. “If large swathes of the general public start taking them off-label for weight loss and then we find out years later that there are bad side effects, it could be a real issue.”

Rethinking long-term weight management strategies to overcome cost barriers

Yet another dimension affecting the use of GLP-1RAs is cost. The drugs are expensive, and experts say the recent spike in popularity has already led to shortages and increased hesitancy among insurance providers to cover these drugs.

“We know these drugs represent a massive breakthrough in our long fight against obesity-related clinical conditions, but their high cost has been the subject of substantial debate,” said David Kim, PhD , a UChicago health economist. “It presents a key barrier to equitable access to this great innovation.”

In pursuit of more equitable and cost-effective approaches to leveraging GLP-1RAs, Kim and a group of other researchers analyzed the potential impact of alternative weight loss programs. Specifically, they proposed an approach in which GLP-1RAs could be prescribed for an initial period of weight loss before patients transitioned to cheaper alternative interventions for weight maintenance such as lower-cost medications, behavioral health programs and support from nutritionists.

“We wanted to challenge the assumption that once you’re on a GLP-1RA drug, you have to keep taking it forever,” Kim said. “That’s where some of the affordability concerns are coming from: large populations are potentially eligible to take these drugs, and we can’t pay for a lifetime supply for everyone.”

The researchers’ model suggested that even though the alternative weight-maintenance programs might be slightly less effective than long-term, full-dosage GLP-1RA use, the clinical benefits would only decrease slightly, while lifetime healthcare spending would decrease substantially.

“We argue that this alternative framework is a viable solution that provides greater flexibility for managing a limited drug supply and giving healthcare payers financial headroom to support more patients accessing effective weight management treatment,” Kim said.

“ Comparative effectiveness of GLP-1 receptor agonists on glycaemic control, body weight, and lipid profile for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis ” was published in The BMJ in January 2024. Authors included Haiqiang Yao, Anqi Zhang, Delong Li, Yuqi Wu, Chong-Zhi Wang, Jin-Yi Wan and Chun-Su Yuan.

“ Effectiveness of glucose-lowering medications on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes at moderate cardiovascular risk ” was published in Nature Cardiovascular Research in April 2024. Authors included Rozalina G. McCoy, Jeph Herrin, Kavya Sindhu Swarna, Yihong Deng, David M. Kent, Joseph S. Ross, Guillermo E. Umpierrez, Rodolfo J. Galindo, William H. Crown, Bijan J. Borah, Victor M. Montori, Juan P. Brito, Joshua J. Neumiller, Mindy M. Mickelson and Eric C. Polley.

“ Balancing Innovation and Affordability in Anti-Obesity Medications: The Role of Alternative Weight Maintenance Program ” was published in Health Affairs Scholar in May 2024. Authors included David D. Kim, Jennifer H. Hwang and A. Mark Fendrick.

Leading Change in Cancer Clinical Research, Because Our Patients Can’t Wait

May 31, 2024 , by W. Kimryn Rathmell, M.D., Ph.D., and Shaalan Beg, M.D.

Greater use of technologies that can increase participation in cancer clinical trials is just one of the innovations that can help overcome some of the bottlenecks holding up progress in clinical research.

Thanks to advances in technology, data science, and infrastructure, the pace of discovery and innovation in cancer research has accelerated, producing an impressive range of potential new treatments and other interventions that are being tested in clinical studies . The extent of the innovative ideas that might help people live longer, improve our ability to detect cancer early, or otherwise transform care is staggering.

Our understanding of tumor biology is also evolving, and those gains in knowledge are being translated into the continued discovery of targets for potential interventions and the development of novel types of treatments. Some of these therapies are producing unprecedented clinical responses in studies, including in traditionally difficult-to-treat cancers.

These advances have contributed to a record number of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals in recent years with, arguably, the most notable approvals being those for drugs that can be used for any cancer, regardless of where it is in the body .

In some instances, the activity of new agents has been so profound that clinical investigators are having to rethink their criteria for implementation in patient care and their definitions of treatment response.

For example, although HER2 has been a known therapeutic target in breast cancer for many decades, the new antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) that target HER2 have proven to be vastly more effective than the original HER2-targeted therapies. This has forced researchers to rethink fundamental questions about how these ADCs are used in patient care: Can they be effective in people whose tumors have lower expression of HER2 than we previously thought was needed ? And, if so, do we need to redefine how we classify HER2-positive cancer?

As more innovative therapies like ADCs hit the clinic at a far more rapid cadence than ever before, the research community is being inundated with such fundamentally important questions.

However, the remarkable progress we're experiencing with novel new therapies is tempered by a critical bottleneck: the clinical research infrastructure can’t be expected to keep pace in this new landscape.

Currently, many studies struggle to enroll enough participants. At the same time, there are patients who don’t have ready access to studies from which they might benefit. Furthermore, ideas researchers have today for studies of innovative new interventions might not come to fruition for 2 or 3 years, or even longer—years that people with cancer don’t have.

The key to overcoming this bottleneck is to invite innovation to help reshape our clinical trials infrastructure. And here’s how we plan to accomplish that.

Testing Innovation in Cancer Clinical Trials

A transformation in cancer clinical research is already underway. That transformation has been led in part by the success of novel precision oncology approaches, such as those tested in the NCI-MATCH trial .

This innovative study ushered in novel ways of recruiting participants and involving oncologists at centers big and small. And NCI-MATCH has spawned several successor studies that are incorporating and building on its innovations and achievements.

An innovation that emerged from the COVID pandemic was the increase of remote work, even in the clinical trials domain. Indeed, staffing shortages have caused participation in NCI-funded trials to decline. In response, NCI is piloting a Virtual Clinical Trials Office to offer remote support staff to participating study sites. This support staff includes research nurses, clinical research associates, and data specialists, all of whom will help NCI-Designated Cancer Centers and community practices engaged in clinical research activities.

Such technology-enabled services can allow us to reimagine how clinical trials are designed and run. This includes developing technologies and processes for remotely identifying clinical trial participants, shipping medications to participants at home, having imaging performed in the health care settings where our patients live, and empowering local physicians to participate in clinical trials.

We also need mechanisms to test and implement innovations in designing and conducting clinical studies.

For example, NCI recently established the Clinical Trials Innovation Unit (CTIU) to pressure test a variety of innovations. One of the first trials to emerge from the CTIU’s initial efforts was the Pragmatica-Lung Cancer Treatment Trial , a phase 3 study designed to be easy to launch, enroll, and interpret its results.

The CTIU, which includes leadership from FDA and NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network , is already working on future innovations, including those that will streamline data collection and apply innovative approaches for other cancers, all with the goal of making cancer clinical studies less burdensome to run and easier for patients to participate.

Data-Driven Solutions

The era of data-driven health care is here, providing still more opportunities to transform cancer clinical research.

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) solutions, large language models, and informatics brings real potential for wholesale changes in how we match patients to clinical studies, assess side effects, and monitor events like disease progression.

Recognizing this potential, NCI is offering funding opportunities and other resources that will fuel the development of AI tools for clinical research, allow us to carefully test their usefulness, and ultimately deploy them across the oncology community.

Creating Partnerships and Expanding Health Equity

To be sure, none of this will be, or can be, done by NCI alone. All these innovations require partnerships. We will increase our engagement with partners in the public- and private-sectors, including other government agencies and nonprofits.

That includes high-level engagement with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), with input from FDA, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. W. Kimryn Rathmell, M.D., Ph.D.

NCI Director

One example of such a partnership is the USCDI+ Cancer program . Conducted under the auspices of the ONC, this program will further the aims of the White House's reignited Cancer Moonshot SM by encouraging the adoption and utilization of interoperable cancer health IT standards, providing resources to support cancer-specific use cases, and promoting alignment between federal partners.

And just as importantly, the new partnerships we create must include those with patients, advocates, and communities in ways we have never considered before.

A central feature of this community engagement must involve intentional efforts to expand health equity, to create study designs that are inclusive and culturally appropriate. Far too many marginalized communities and populations today are further harmed by studies that fail to provide findings that apply to their unique situations and needs.

Very importantly, the future will require educating our next generation of clinical investigators and empowering them with the tools that enable new ways of managing clinical studies. By supporting initiatives spearheaded by FDA and professional groups like the American Society of Clinical Oncology, NCI is making it easier for community oncologists to participate in clinical trials and helping clarify previously misunderstood regulatory requirements.

These efforts must also ensure that we have a clinical research workforce that is representative of the people it is intended to serve. Far too many structural barriers have prevented this from taking place in the past, and it’s time for that to change.

Expanding our capacity doesn’t mean doing more of the same, it means challenging ourselves to work differently. This will let us move forward to a new state, one in which clinical research is integrated in everyday practice. It is only with more strategic partnerships and increased inclusivity that we can open the doors to seeing clinical investigation in new ways, with new standards for success.

A Collaborative Effort

Shaalan Beg, M.D.

Senior Advisor for Clinical Research

To make the kind of progress we all desire, we have to recognize that our clinical studies system needs to evolve.

There was a time when taking years to design, launch, and complete a clinical trial was acceptable. It isn’t acceptable anymore. We are in an era where we have the tools and the research talent to make far more rapid progress than we have in the past.

And we can do that by engaging with many different communities and stakeholders in unique and dynamic ways—making them partners in our effort to end cancer as we know it.

Together, our task is to capitalize on this work so we can move faster and enable cutting-edge research that benefits as many people as possible.

We also know that there are more good ideas in this space, and part of this transformation includes grass roots efforts to drive systemic change. So, we encourage you to share your ideas on how we can transform clinical research. Because achieving this goal can’t be done by any one group alone. We are all in this together.

Featured Posts

March 27, 2024, by Edward Winstead

March 21, 2024, by Elia Ben-Ari

March 5, 2024, by Carmen Phillips

- Biology of Cancer

- Cancer Risk

- Childhood Cancer

- Clinical Trial Results

- Disparities

- FDA Approvals

- Global Health

- Leadership & Expert Views

- Screening & Early Detection

- Survivorship & Supportive Care

- February (6)

- January (6)

- December (7)

- November (6)

- October (7)

- September (7)

- February (7)

- November (7)

- October (5)

- September (6)

- November (4)

- September (9)

- February (5)

- October (8)

- January (7)

- December (6)

- September (8)

- February (9)

- December (9)

- November (9)

- October (9)

- September (11)

- February (11)

- January (10)

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Factors influencing the participation of pregnant and lactating women in clinical trials: A mixed-methods systematic review

Contributed equally to this work with: Mridula Shankar, Alya Hazfiarini

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Gender and Women’s Health Unit, Nossal Institute for Global Health, School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, Carlton, Victoria, Australia

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Program, Burnet Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Roles Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation University Library, University of Melbourne, Carlton, Victoria, Australia

Affiliation Women’s and Children’s Health Research Unit, KLE Academy of Higher Education and Research, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Belagavi, Karnataka, India

Affiliation Concept Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland/Bangkok, Thailand

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Mridula Shankar,

- Alya Hazfiarini,

- Rana Islamiah Zahroh,

- Joshua P. Vogel,

- Annie R. A. McDougall,

- Patrick Condron,

- Shivaprasad S. Goudar,

- Yeshita V. Pujar,

- Manjunath S. Somannavar,

- Published: May 30, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004405

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Poor representation of pregnant and lactating women and people in clinical trials has marginalised their health concerns and denied the maternal–fetal/infant dyad benefits of innovation in therapeutic research and development. This mixed-methods systematic review synthesised factors affecting the participation of pregnant and lactating women in clinical trials, across all levels of the research ecosystem.

Methods and findings

We searched 8 databases from inception to 14 February 2024 to identify qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies that described factors affecting participation of pregnant and lactating women in vaccine and therapeutic clinical trials in any setting. We used thematic synthesis to analyse the qualitative literature and assessed confidence in each qualitative review finding using the GRADE-CERQual approach. We compared quantitative data against the thematic synthesis findings to assess areas of convergence or divergence. We mapped review findings to the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation Model of Behaviour (COM-B) to inform future development of behaviour change strategies.

We included 60 papers from 27 countries. We grouped 24 review findings under 5 overarching themes: (a) interplay between perceived risks and benefits of participation in women’s decision-making; (b) engagement between women and the medical and research ecosystems; (c) gender norms and decision-making autonomy; (d) factors affecting clinical trial recruitment; and (e) upstream factors in the research ecosystem. Women’s willingness to participate in trials was affected by: perceived risk of the health condition weighed against an intervention’s risks and benefits, therapeutic optimism, intervention acceptability, expectations of receiving higher quality care in a trial, altruistic motivations, intimate relationship dynamics, and power and trust in medicine and research. Health workers supported women’s participation in trials when they perceived clinical equipoise, had hope for novel therapeutic applications, and were convinced an intervention was safe. For research staff, developing reciprocal relationships with health workers, having access to resources for trial implementation, ensuring the trial was visible to potential participants and health workers, implementing a woman-centred approach when communicating with potential participants, and emotional orientations towards the trial were factors perceived to affect recruitment. For study investigators and ethics committees, the complexities and subjectivities in risk assessments and trial design, and limited funding of such trials contributed to their reluctance in leading and approving such trials. All included studies focused on factors affecting participation of cisgender pregnant women in clinical trials; future research should consider other pregnancy-capable populations, including transgender and nonbinary people.

Conclusions

This systematic review highlights diverse factors across multiple levels and stakeholders affecting the participation of pregnant and lactating women in clinical trials. By linking identified factors to frameworks of behaviour change, we have developed theoretically informed strategies that can help optimise pregnant and lactating women’s engagement, participation, and trust in such trials.

Author summary

Why was this study done.

- Pregnant and lactating women and people are routinely excluded from participating in drug and vaccine clinical trials, resulting in limited options for prevention and treatment of medical conditions.

- Challenges to including pregnant and lactating women and people in clinical research have been identified at multiple levels of the research and health systems, but the full range of barriers and facilitators to participation are not well known.

What did the researchers do and find?

- We conducted a mixed-methods systematic review and identified 60 research articles from 27 countries on the views and experiences of pregnant and lactating women’s participation in clinical research, from the perspectives of cisgender women, family and community members, health workers, and people involved in the conduct of clinical research.

- Using a thematic synthesis approach, we identified barriers affecting participation including women having a limited appetite for risk during pregnancy and lactation, concerns about women’s bodily autonomy during pregnancy, and challenges in obtaining ethical approval for clinical research with pregnant women.

- We also identified facilitators of participation including the potential for personal health benefits, expectations of higher quality care, trust in the medical and research systems, and strong teamwork between researchers and health workers.

What do these findings mean?

- Our findings demonstrate the need for multipronged strategies to address barriers and reinforce facilitators across the various levels of the research and health systems.

- The actions that are needed to overcome these barriers and reinforce facilitators must be discussed, prioritised, and adapted to specific contexts.

- All included studies focused on factors affecting participation of cisgender pregnant women in clinical trials; future research should consider other pregnancy-capable populations, including transgender and nonbinary people.

Citation: Shankar M, Hazfiarini A, Zahroh RI, Vogel JP, McDougall ARA, Condron P, et al. (2024) Factors influencing the participation of pregnant and lactating women in clinical trials: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med 21(5): e1004405. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004405

Received: December 20, 2023; Accepted: April 19, 2024; Published: May 30, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Shankar et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The research in this publication was supported by funding from MSD (grant MFM-22-159697 to Concept Foundation), through its MSD for Mothers initiative ( https://www.msdformothers.com/ ) and is the sole responsibility of the authors. MSD for Mothers is an initiative of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, U.S.A. MAB’s time is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE200100264) and a Dame Kate Campbell Fellowship (University of Melbourne Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences). JPV is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator grant (GNT1194248). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations: BCW, Behaviour Change Wheel; COM-B, Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation Model of Behaviour; MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework

Introduction

Clinical trials are the foundation for knowledge on the efficacy and safety of biomedical interventions to protect health and treat illness. The fundamental questions of who participates and whose data contributes to trials have implications for understanding the risks and benefits of interventions, and the societal value of such interventions to specific populations. Pregnant and lactating women and people have long been underrepresented or excluded entirely from participating in therapeutic and vaccine clinical trials [ 1 ]. Notwithstanding valid concerns regarding fetal and infant safety, an outright exclusionary response to this complex issue has denied the maternal–fetal/infant dyad the health benefits of biomedical innovation, despite demonstrated public health need [ 2 , 3 ]. As a recent example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, pregnant women and people were excluded from early therapeutic and vaccine trials despite greater severity of infection-related illness [ 4 – 9 ].

Including pregnant and lactating women and people as research participants is vital: pregnancy is a unique physiological state where the body undergoes adaptations that can lead to pregnancy-specific disorders or worsen preexisting conditions [ 10 ]. These changes can influence how effective a drug is, whether and how the body responds to the drug, and the dosages at which the drug is optimally effective and minimally harmful. Most pregnant women take at least 1 medication during pregnancy [ 11 ], yet many of these medications are provided with limited information on efficacy, appropriate dosing, and safety in these populations [ 1 ]. Pregnant and lactating women with preexisting illnesses may also be advised to discontinue medications to minimise potential harms, without full appreciation of the possible consequences of unmedicated disease progression [ 12 ].

The current state of maternal health and the limited therapeutic options available for pregnant and lactating populations illustrates the consequences of these evidence gaps. Each year, complications of pregnancy and childbirth result in approximately 287,000 maternal deaths [ 13 ], 1.9 million stillbirths [ 14 ], and 2.3 million neonatal deaths [ 15 ]. Most of these deaths occur from preventable or treatable obstetric causes (e.g., postpartum haemorrhage, preeclampsia/eclampsia, sepsis) that are generally treated using repurposed medications that were originally developed and approved for use in other non-obstetric conditions [ 16 ]. Over the past 3 decades, only 2 drugs have been registered to specifically treat pregnancy-related complications: Atosiban—a tocolytic to prevent preterm birth, and Carbetocin—an oxytocin analogue for managing postpartum haemorrhage [ 17 ]. Pregnancy-specific medicines rarely progress through the research and development pipeline due to a multitude of factors, including the absence of public stewardship, chronic underinvestment, and regulatory and market barriers [ 18 , 19 ]. Maternal mortality rates have largely remained static in the Sustainable Development Goal era: progress has halted or reversed in 150 countries [ 13 ]. Without significant investments in pharmaceutical development, the 2030 target of a global maternal mortality ratio less than 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births [ 20 ] is unlikely to be achieved.

Poor representation of pregnant and lactating women and people in clinical research, and the absence of a pregnancy-focused research and development agenda violates fundamental ethical principles of justice and equity [ 12 , 21 ]. Challenges to equitable inclusion operate across all research stages: “upstream” barriers include a lack of appropriate animal models, pharmaceutical industry risk aversion, and clinical trials and liability insurance challenges [ 12 , 18 , 22 , 23 ]. “Downstream” barriers include perceptions that pregnant and lactating women do not want to take part in clinical trials, or that their inclusion makes research activities too risky or onerous [ 23 ]. Overall, there is a lack of a comprehensive understanding of the full range of these factors from the perspectives of key stakeholder groups. This mixed-methods systematic review seeks to address this gap by synthesising current research evidence on factors (i.e., barriers and facilitators) affecting the participation of pregnant and lactating women in vaccine and therapeutic clinical trials. We use behavioural [ 24 , 25 ] frameworks to provide a theory-informed basis for the development and implementation of appropriate behaviour change intervention strategies to promote their meaningful inclusion.

This review is reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines ( S1 Appendix ), Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement ( S2 Appendix ), and based on guidance from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care group [ 26 ]. The protocol has been registered (PROSPERO: CRD42023462449).

Types of studies

We included primary qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies. There were no limitations on publication date, language, or country.

We excluded publications that were not primary research, including conceptual scholarship on the ethics of inclusion/exclusion, case reports, reviews, commentaries, short communications, editorials, news articles, letters to the editor, conference abstracts, workshop summaries, theses or dissertations, book chapters, book reviews, and regulatory or committee guidance or decisions.

Topic of interest

This review focuses on systematically identifying the factors, including barriers and facilitators, influencing the participation of pregnant and lactating women in drug or vaccine trials (i.e., therapeutic or prophylactic trials). We recognise that people who are capable of pregnancy have diverse gender identities. We use the terminology “pregnant and lactating women,” acknowledging that empirical literature on this topic has been focused on the experiences of cisgender women. Extrapolating these data to apply to people with other gender identities may lead to inaccurate or incomplete conclusions.

We included studies that described the attitudes, perspectives, and experiences of multiple stakeholders: women who participated and declined participation in clinical trials during pregnancy and lactation, partners or husbands, family members, community leaders, health workers, research staff, study investigators, ethics committee members, regulators, funders, pharmaceutical representatives, policy makers, and other relevant stakeholders.

We excluded the following types of interventions from this review: (a) lifestyle or behavioural interventions; (b) trials of diagnostics or medical devices; (b) workforce interventions to improve clinical care outcomes; (c) alternative or complementary medicine; (d) trials evaluating health policies or clinical protocols; (e) fetal tissue research, bio-banking, and genetic testing; (f) facilitators and barriers to engaging pregnant women in observational research; (g) supports to clinicians or pregnant or lactating women regarding decision-making on medication; and (h) research solely focused on substance use prevention and treatment, due to the particularly distinct barriers and facilitators given overlapping vulnerabilities among substance-using pregnant women, and unique considerations in relation to fetal health such as in utero exposure to alcohol and other substances. We also excluded clinical trial protocols and publications of randomised controlled trials that did not contain data related to facilitators or barriers to trial participation.

Search methods for identification of relevant studies

We searched 8 databases from inception to 14 February 2024: MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL Complete, Family & Society Studies Worldwide, SocINDEX, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, Embase (Ovid), and Global Health (Ovid). PC, an Information Specialist developed the final search strategy ( S3 Appendix ), using a combination of terms relevant to pregnant and lactating women, and perspectives and experiences of stakeholders regarding their inclusion/exclusion and participation in drug or vaccine clinical trials. No restrictions were placed on publication year, language, or geographical setting.

Selection of studies

We imported the search results into Covidence [ 27 ] and removed duplicates. Five review authors (MS, AH, MAB, AM, and AA) independently screened titles and abstracts. Titles and abstracts of non-English publications were screened with the assistance of Google Translate. Three reviewers (MS, AH, and AM) independently reviewed full texts. One French publication that met the inclusion criteria was translated to English using ChatGPT [ 28 ], and translation accuracy was subsequently verified with a native French speaker in our research network. At each screening stage, differences in decisions regarding record inclusion were resolved through discussion and final decisions were made through consensus with a third review author (MAB).

Data extraction and assessing methodological limitations

Two review authors (MS and AH) extracted relevant data, including study aims, methodological characteristics, geographical settings, population of interest (pregnant women, lactating women, or both), intervention type (therapy or vaccine), specific areas of research, and study findings (author-generated themes, supporting explanations, participant quotes, survey results, and relevant tables and figures). We developed a data extraction form and refined it by extracting data from a subset of 6 studies. All extracted data was cross-checked for accuracy and completeness, and differences resolved via consensus.

Two reviewers (MS and AH) independently assessed the methodological limitations of each study using an adapted Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [ 29 ]. For qualitative studies, evaluative criteria included alignment of methodology and data collection with research aims, rigour in data analysis and reporting of study findings, ethical considerations, and researcher reflexivity. We assessed quantitative studies based on the suitability of sampling strategy, reporting on sample representativeness, use of appropriate measures, level of nonresponse bias, ethical considerations, and relevance of statistical analyses conducted. In addition to the aforementioned criteria, we assessed mixed-methods studies to determine whether authors demonstrated sufficient rationale for the use of a mixed-methods approach, effectiveness of integration of study components and outputs, and discussion of data triangulation. All differences in assessments between the 2 review authors were resolved through discussion. The assessment of methodological limitations did not affect the inclusion or exclusion of studies but rather served as a mechanism for determining confidence in the evidence.

Data analysis and synthesis

We used a thematic synthesis approach to analyse qualitative data [ 30 ]. After selecting 6 data-rich studies, 2 reviewers (MS and AH) independently applied line-by-line coding to the textual data to create summative codes. Codes were discussed for consistency in meaning and refined if necessary. The remaining studies were each coded by one of the 2 reviewers, and new codes were added as necessary. Through discussion, we subsumed codes of similar meaning under broader categories, gradually developing “summary layers” in a hierarchical grouping structure. We applied the gender domains of the gender analysis matrix [ 31 ] as a lens to our findings to understand how our data on factors influencing participation were shaped by aspects such as distribution of labour and roles, gender norms and beliefs, access to resources, decision-making power, and institutional policies. We consolidated our results into a set of 5 overarching themes and 24 review findings through an iterative process of identifying, comparing, and discussing conceptual boundaries between and among thematic data outputs.

Two review authors (MS and AH) used the GRADE-CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) approach [ 32 , 33 ] to assess our confidence in each of the 24 qualitative review findings. GRADE-CERQual assesses confidence in the evidence, based on the following 4 key components [ 26 ]:

- methodological limitations of included studies [ 34 ];

- coherence of the review finding [ 35 ];

- adequacy of the data contributing to the review finding [ 36 ]; and

- relevance of the included studies to the review question [ 37 ].

After assessing each component, we made a judgement via consensus about the overall confidence—rated as high, moderate, low, or very low—in the evidence supporting the review finding [ 32 ]. Detailed descriptions of the GRADE-CERQual assessments are in S4 Appendix .

We then mapped data from the quantitative studies onto the findings of the qualitative evidence synthesis, and determined areas of convergence or divergence, and whether any additional factors arose that had previously not been discussed. We regarded the quantitative data as (a) “supporting” of a qualitative evidence synthesis finding if the information synthesised from the contributory quantitative studies were similar to the finding; (b) “extending” if the data offered additional details in line with a review finding; and (c) “contradictory” if the data conflicted with a review finding. Summaries of the quantitative findings are presented in S5 Appendix .

Finally, we mapped our review findings to the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [ 24 ] and the Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation (COM-B) [ 25 ] models of behavioural determinants and the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) to identify and provide a rational basis for the development and implementation of appropriate behaviour change strategies.

Review team and reflexivity

The review author team has diverse personal backgrounds, including gender, personal experiences of pregnancy, countries of origin and residence, and linguistic traditions. Our professional and academic backgrounds and experiences are varied, and include the social, behavioural, and biomedical sciences, medicine, clinical epidemiology, and public health. Some review authors have led and implemented trials in maternal and perinatal health. As an interdisciplinary team with diverse social and professional backgrounds, we maintained a reflexive stance through all stages of the review process by engaging in multiple reflective dialogues to interrogate and interpret the data and findings. Through this process, we named and critiqued assumptions that underpinned the analysis and challenged disciplinary biases. In doing so, we aimed to develop review findings that were inclusive of different disciplinary lenses.

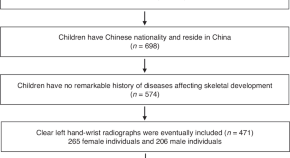

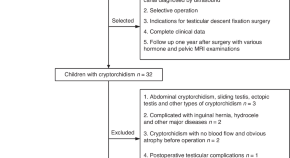

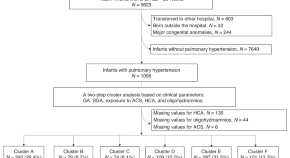

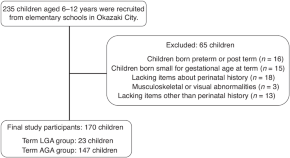

Sixty papers from 53 studies met the inclusion criteria [ 38 – 97 ]. Fig 1 presents the PRISMA flowchart. Table 1 reports the summary characteristics of included papers and S6 Appendix includes more detailed individual characteristics of the included papers.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004405.g001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004405.t001

Description of papers

Thirty-nine papers used qualitative methodologies [ 39 , 40 , 42 – 48 , 53 , 54 , 56 – 66 , 69 , 70 , 72 – 74 , 78 , 81 , 82 , 84 – 87 , 89 – 92 , 96 ], 18 papers used quantitative methodologies [ 38 , 41 , 50 – 52 , 67 , 68 , 71 , 75 – 77 , 79 , 80 , 88 , 93 – 95 , 97 ], and 3 papers used mixed-methods study designs [ 49 , 55 , 83 ].

The 60 papers present data from 27 countries and 4 geographic regions: 13 countries in Africa [ 44 – 47 , 65 , 73 , 78 , 84 , 85 ], 8 countries in Europe [ 38 , 39 , 41 , 48 – 50 , 53 – 56 , 58 , 59 , 61 , 62 , 64 , 67 – 69 , 72 , 74 , 80 – 83 , 86 , 89 , 90 , 92 , 94 , 96 ], 3 countries in the Americas [ 42 , 43 , 51 , 52 , 57 , 60 , 63 , 66 , 70 , 71 , 75 , 77 , 79 , 85 , 88 , 91 , 93 , 95 ], and 3 countries in the Western Pacific [ 40 , 76 , 87 , 97 ].

Fifty-one papers focused on pregnant women only [ 38 – 41 , 44 , 47 – 50 , 52 , 53 , 55 – 70 , 72 – 94 , 97 ], 2 papers focused on lactating women only [ 46 , 96 ], and 7 papers focused on pregnant and lactating women [ 42 , 43 , 45 , 51 , 54 , 71 , 95 ]. Thirty-seven papers addressed a therapeutic drug-related intervention [ 38 , 40 , 41 , 44 – 49 , 53 , 56 , 59 – 62 , 66 , 69 , 70 , 72 , 73 , 77 , 79 – 90 , 92 , 93 , 96 , 97 ], 11 papers focused on a vaccine-related intervention [ 50 , 51 , 55 , 57 , 58 , 63 , 64 , 67 , 68 , 78 , 94 ], and 12 papers were about pregnant and/or lactating women’s participation in interventional clinical trials generally [ 39 , 42 , 43 , 52 , 54 , 65 , 71 , 74 – 76 , 91 , 95 ].

Twenty-five papers included perspectives of pregnant women [ 38 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 51 , 57 , 58 , 60 , 61 , 64 , 65 , 67 , 71 – 75 , 77 , 85 , 89 – 91 , 94 , 95 , 97 ], 28 papers included perspectives of postpartum women [ 39 – 41 , 44 – 46 , 49 , 51 , 56 , 57 , 59 , 62 , 63 , 69 – 71 , 74 , 79 – 87 , 92 , 95 ], and 14 papers included health workers’ perspectives [ 44 , 47 , 50 , 52 – 54 , 61 , 64 , 65 , 67 , 87 , 88 , 91 , 94 ]. For other stakeholder groups, please refer to Table 1 .

Methodological limitations of included studies

Assessments of methodological limitations of the included studies are available in S7 Appendix . Across qualitative studies, the most common methodological limitations concerned recruitment approaches and strategies, descriptions of analytical methods, ethical considerations, specifically steps or precautions taken to protect from loss of privacy and confidentiality, data security and integrity, and most studies did not include a reflexivity statement. Across quantitative studies, authors rarely reported on indicators of sample representativeness of the target population, most did not report on or were judged at high risk of nonresponse bias, and ethical considerations pertaining to data security and integrity were frequently missing. For the 3 mixed-methods studies, limitations were identified at the level of integrating methodological approaches at the methods, interpretation, and reporting levels.

Themes and findings from the qualitative and quantitative evidence synthesis

We developed 5 overarching themes and 24 review findings in the qualitative evidence synthesis ( Table 2 ):

- interplay between perceived risks and benefits of participation in women’s decision-making (9 review findings);

- engagement between women and the medical and research ecosystems (2 review findings);

- gender norms and decision-making autonomy (3 review findings);

- factors affecting clinical trial recruitment (7 review findings); and

- upstream factors in the research ecosystem (3 review findings).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004405.t002

We graded 6 review findings as high confidence, 11 as moderate confidence, and 7 as low confidence. An explanation for each GRADE-CERQual assessment is presented in the evidence profile ( S4 Appendix ).

Interplay between perceived risks and benefits of participation in women’s decision-making

Findings 1 to 9 are categorised under this theme with 48 studies exploring women’s perspectives on clinical trial participation and factors influencing their decision-making. These factors include balancing risks and benefits, experiences and expectations of high quality care, understanding of study design features, acceptability and stigma associated with the intervention, altruistic motivations and financial incentives.

Finding 1 : Women have a limited appetite and higher perception of risk during pregnancy or lactation . Perception of risks influenced pregnant and lactating women’s willingness to participate in trials, which varied based on their individual levels of risk tolerance, previous trial experiences, observations of others’ experiences, stage of pregnancy or lactation, existing health conditions, and a sense of responsibility for their health and that of the fetus/infant. Women were more likely to decline participation if the experimental intervention was previously untested and were more confident to participate when convinced of no harm (high confidence) [ 39 , 40 , 47 , 48 , 57 , 58 , 60 , 63 – 65 , 69 , 72 , 74 , 83 , 84 , 87 , 89 , 91 , 92 , 96 ].

The most salient factors affecting perceptions of risk were concerns of potential harm to the fetus or baby, including in the longer term, and fears of side-effects [ 39 , 48 , 57 , 58 , 60 , 63 , 69 , 72 , 74 , 83 , 84 , 87 , 89 , 91 , 92 , 96 ]. The uncertainty of these negative outcomes contributed to women’s reluctance to take medications [ 48 , 64 , 69 , 72 ] or participate in experimental interventions, with some likening the experience to being treated as “guinea pigs” [ 39 , 56 , 58 , 69 , 90 ]. Women willing to consider participation wanted proof of safety from previous research evidence [ 57 , 58 , 84 ], online resources [ 96 ], discussions with research staff and health workers [ 96 ], and knowing the experiences of others who had taken the intervention [ 47 , 96 ].

Quantitative evidence supported the qualitative findings that women were apprehensive about taking an experimental product during pregnancy or lactation [ 79 ] primarily due to concerns of fetal or infant harm [ 38 , 51 , 67 , 71 , 75 , 83 , 94 , 95 ], side-effects [ 77 , 80 ], and the possibility of unknown longer-term negative sequelae [ 67 , 75 , 77 ]. Prior knowledge of the health condition [ 68 ], information about drug safety in pregnant and nonpregnant populations [ 51 ], and information that large numbers of pregnant women had already enrolled in the trial [ 67 ] were factors that increased willingness to participate.

Finding 2 : Making trade-offs between risk and severity of the condition and risk-benefit ratio of intervention . Before participating, women weighed the risk of their medical condition and its impact, especially on the baby, against the risks of an intervention and its potential benefits. Women were less likely to participate if they felt healthy or perceived themselves at low risk of experiencing or being negatively affected by the condition, believed they had nothing to gain from participating, or felt concerned that the intervention risks were too high (moderate confidence) [ 39 , 48 , 57 – 60 , 63 , 64 , 69 , 72 , 74 , 87 , 91 , 96 ].

Women were more willing to participate when they had concerns about their risk factors [ 70 ], had previously experienced the condition [ 48 , 70 ], or personally knew someone who had [ 48 ], were anxious about the baby suffering health problems [ 57 – 60 ], or perceived the intervention to be helpful based on past use [ 87 ], or the only course of action to avoid (further) ill-health [ 57 – 59 , 63 , 91 ]. For some women with preconceived notions that research entailed significant risks, their perceptions did not change in the presence of information, including about intervention safety [ 48 ].

Quantitative evidence supported the qualitative findings that, when coupled with risks that were considered minimal or manageable [ 83 ], women with greater knowledge about [ 83 ] or direct exposure to the condition [ 94 ] were more likely to participate in a vaccine or therapeutic trial. However, prior exposure to the medical condition did not consistently lead to higher participation in trials [ 51 ].

Finding 3 : Benefits to health arising from participation . A key motivating factor for pregnant and lactating women to participate in trials was the expectation of personal health benefits, such as improved knowledge about how the condition affected them, protecting their fetus or infant from harm, and reducing mother-to-child disease transmission. When women saw the potential for these benefits, deciding not to participate was viewed as potentially putting the baby’s life at risk (high confidence) [ 40 , 47 , 55 , 60 , 61 , 63 , 64 , 70 , 73 , 83 , 84 , 87 , 90 – 92 , 96 ].

Quantitative evidence supported this finding that women were more willing to participate in a trial when they were convinced about the potential short and longer-term benefits of the intervention for the health of the fetus [ 38 , 51 , 75 , 77 , 80 ], and their own health [ 38 , 41 , 51 , 75 , 80 , 95 ] and education [ 41 , 95 ].

Finding 4 : Experiences and expectations of high-quality care motivate participation . Pregnant and lactating women were motivated to participate as a token of appreciation to health workers who provided good quality care. Additionally, women were more likely to participate when they perceived that it would result in higher quality clinical care or access to vaccines or therapeutic products that had previously been denied or were otherwise not accessible outside the context of a trial (high confidence) [ 39 , 48 , 49 , 60 , 63 , 70 , 72 , 83 , 84 , 86 , 87 , 92 , 96 ].

In addition to free medications and vaccines, women’s perceptions of higher quality care were linked to greater frequency of diagnostic and monitoring tests [ 72 , 83 , 84 , 92 ], detailed information regarding care provided [ 63 ], and closer and continuous clinical observation [ 49 , 63 , 70 , 92 ]. Occasionally, women perceived care associated with a trial as lower quality due to the “experimental” nature of the intervention [ 39 ].

Quantitative evidence supported the qualitative finding that women expected trial participation to engender more and better quality care through enhanced monitoring [ 38 , 41 , 67 , 68 , 80 ], more tests [ 67 ], better therapeutic treatment [ 38 , 49 ], and the general feeling of being provided a high standard of medical care [ 51 , 75 , 80 ].

Finding 5 : Knowledge of the rationale for study design features . The rationale behind certain trial design features such as randomisation, blinding or inclusion of a placebo arm could be a source of confusion, concern, or reassurance for potential participants, impacting their decisions to participate. These features could be viewed as preferential treatment of one group over another, adding burden with little opportunity for personal benefit, a mechanism to reduce bias or conversely for researchers to avoid accountability for an adverse outcome (moderate confidence) [ 39 , 40 , 45 , 59 , 62 , 63 , 69 , 72 , 74 , 87 , 91 , 92 ].

Quantitative evidence extended understanding of women’s views about participation in placebo-controlled trials. Some women expressed reluctance to participate due to the possibility of being assigned to the control or placebo group [ 67 , 77 , 79 , 83 ]. However, others expressed that the uncertainty of assignment would not affect their decision, and for a minority, the possibility of assignment to the control condition motivated their participation as it could minimise risk but still provide ancillary benefits [ 67 ]. Women were keen to be unblinded regarding the arm to which they were assigned, once the trial was complete [ 80 ].

Finding 6 : Acceptability of the intervention is key to pregnant and lactating women’s willingness to participate in a trial and for research staff to recruit for a trial . Interventions that were most acceptable to women and research staff were those that simplified intervention delivery, were less onerous or painful than usual care, had negligible risk, were noninvasive, placed limited demands on time, did not involve invasive procedures, and where prior knowledge about the condition intersected with positive attitudes towards the therapeutic product (high confidence) [ 40 , 45 , 48 , 53 , 54 , 61 , 64 , 65 , 72 , 73 , 81 , 83 , 86 , 87 , 90 – 92 , 96 ].

For health workers involved in recruitment and trial operations, acceptability of the intervention was closely linked to their perceptions of the safety of the experimental therapy, derived from previous positive experiences administering the drug in a different clinical setting [ 53 ].

Quantitative evidence supported this qualitative finding that some women might be more willing to participate in a trial when they were less likely to be inconvenienced by or experience discomfort from trial procedures, additional and lengthy study visits [ 38 , 41 , 80 ]. Decliners cited blood tests, additional scans, and availability of suitable noninvasive alternatives as reasons for nonparticipation [ 51 , 83 ]. In the case of vaccine trials, quantitative data extended this qualitative finding by suggesting that women indicated greater acceptability of inactivated virus vaccines compared to live-attenuated virus vaccines [ 51 ].

Finding 7 : Fears around data sharing and use . Some women feared that trial participation, including provision of blood samples, could expose them to stigmatisation and judgement due to unwanted diagnoses and disclosure of disease status, data sharing regarding sensitive behaviours, and the threat of their data being used in ways that would compromise confidentiality and safety (low confidence) [ 65 , 85 , 86 ]. In the context of HIV trials, some women discussed concerns that an HIV diagnosis would lead to abandonment by their husbands [ 85 ].

No quantitative evidence was identified in this domain.

Finding 8 : Altruistic motivations . Pregnant women expressed willingness to participate in trials for the purpose of contributing to societal benefits of research, including the potential to improve health and healthcare for pregnant women in the future. Altruistic motivations could act as a stand-alone stimulus, secondary to or alongside beliefs around personal benefit, or conditional on no additional risk for participation (moderate confidence) [ 39 , 40 , 47 , 48 , 55 – 61 , 63 , 64 , 70 , 72 – 74 , 83 , 86 , 87 , 89 , 91 , 92 ].

In addition to helping other women, altruistic sentiments were linked to perceptions that the research effort was worthy [ 48 , 59 , 61 ], well-intentioned [ 61 ], filled an important scientific gap [ 58 , 70 , 72 ], and addressed a pressing need [ 48 , 63 , 73 , 91 ].

Quantitative evidence supported the qualitative finding that altruistic motivations influenced willingness to participate in trials, alongside personal benefits [ 38 , 41 , 49 , 51 , 67 , 77 , 80 , 95 ]. Women expressed having a sense of fulfilment that participation would have a positive impact on women’s health in the future.

Finding 9 : Financial incentives . Pregnant and lactating women had mixed attitudes to financial incentives for research participation. Some viewed financial incentives as acceptable, with higher remuneration as an appropriate strategy to encourage participation, whereas others viewed financial incentives as potentially coercive, especially in the context of poverty. Some women felt that financial reimbursements did not play a substantial role in women’s decision-making (low confidence) [ 39 , 55 , 65 , 83 , 96 ].

Negative views on renumeration arose from concerns that financial incentives would entice women to enrol multiple times [ 65 ], or make it challenging for them to withdraw from the study [ 39 ].

Quantitative evidence extended this qualitative finding by suggesting that attitudes to financial compensation differed based on levels of education attainment [ 97 ]. In one study, less than 1 in 10 women discussed that financial incentives would increase their likelihood of participation in medication or vaccine-based research [ 75 ], whereas in another, 4 in 10 women agreed that they volunteered to participate due to financial compensation [ 41 ].

Engagement between women and the medical and research ecosystems

Findings 10 and 11 are categorised under this theme, with 34 contributing studies examining factors operating at the intersection of women and the medical and research ecosystems. The factors include women’s reliance on health workers’ clinical opinions to assist decision-making, and the role of therapeutic hope and optimism in women’s decisions to participate and health worker and research staffs’ motivations to administer trials.

Finding 10 : Roles of trust and power in the medical and research ecosystem . Pregnant and lactating women’s willingness to participate in trials was driven by trust, confidence, and faith in medicine and research, and women relied on the opinions of the health workers that they consulted with regarding the efficacy and safety of the intervention. Simultaneously, power imbalances between women and health workers, coupled with women’s therapeutic misconceptions, could lead to coercion in participation. This ethical dilemma was recognised by study investigators, ethics committee members, and women, especially in the context of the dual roles of clinician-researchers; however, power and credibility when combined with good rapport and clear communication generated trust to participate or comfort to decline. While rare, some women had larger concerns about the vested interests of pharmaceutical companies (high confidence) [ 39 , 40 , 42 – 45 , 47 – 49 , 56 – 61 , 65 , 69 , 70 , 72 – 74 , 81 , 82 , 86 , 87 , 89 , 91 , 92 ].

Quantitative data supported the qualitative finding that trust (or lack thereof) in health workers, research teams, and pharmaceutical companies affected participation [ 38 , 51 , 75 , 95 ]. Some women felt pressured to participate by health workers and were disappointed by the lack of an individualised approach to recruitment [ 80 ]. Among decliners of a vaccine trial, some noted that recommendations from a health worker could motivate a change of mind [ 51 ].

Finding 11 : The role of therapeutic hope and optimism . Therapeutic hope and optimism played a critical role for health workers and research staff to administer trials, and for pregnant and lactating women to participate in trials. Prior knowledge about and experience with using the intervention, observation of potential beneficial effects, and trust in health workers shaped feelings of therapeutic hope and optimism. However, for some women, a lack of understanding of the differences between research and clinical care when combined with therapeutic hope led to therapeutic misconceptions and unmet expectations about the personal benefits arising from trial participation (moderate confidence) [ 42 , 45 , 47 , 53 , 65 , 70 , 74 , 81 , 82 , 87 ].

Health workers expressed the importance of women and themselves comprehending the differences between research and clinical care to minimise participation arising from therapeutic misconceptions [ 47 ].

Gender norms and decision-making autonomy

Findings 12 to 14 are categorised under this theme with 24 contributing studies discussing women’s roles as mothers and caregivers, mixed perceptions of women’s autonomous decision-making, and intimate male partner involvement in decision-making.

Finding 12 : Expectations of women’s roles as mothers and caregivers . Pregnant and lactating women’s decisions to participate in clinical trials were often influenced by their strong sense of responsibility towards the health and care of their fetus or infant, themselves, and their families. This sense of responsibility was endorsed and reinforced by familial and societal expectations of what it means to be a good mother (low confidence) [ 60 , 61 , 64 , 91 , 96 ].

For some women, this responsibility to protect their baby translated to not engaging in any actions that might risk jeopardising the baby’s health [ 91 ].

Finding 13 : Role of bodily autonomy in decision-making . Some women, health workers, ethics committee members, and regulators perceived that pregnant women might not be able to make decisions by themselves about trial participation due to fetal involvement, inability to make rational choices during pregnancy, hormones, the stressful context of hospitalisation and financial inducements. However, research staff and some women believed in the right to bodily autonomy to make decisions by themselves despite having discussions with partners, family members, support persons, or health workers. Women viewed other people making decisions regarding their participation as a violation of this right, though some women declined participation due to pressure from family members (moderate confidence) [ 39 , 40 , 43 , 47 , 54 , 56 , 72 , 74 , 81 , 82 , 85 , 87 , 90 , 92 ].

Women also believed that research could be an avenue through which women demanded their rights in the healthcare [ 65 ].

Quantitative evidence supported qualitative findings that women believed in their capability to make decisions regarding trial participation, with some doing so autonomously and others receiving support from family members [ 38 , 83 ].