Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Topic collections

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 13, Issue 2

- Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Sarah Peters

- Correspondence to : Dr Sarah Peters, School of Psychological Sciences, The University of Manchester, Coupland Building 1, Oxford Road M13 9PL, UK; sarah.peters{at}manchester.ac.uk

As the evidence base for the study of mental health problems develops, there is a need for increasingly rigorous and systematic research methodologies. Complex questions require complex methodological approaches. Recognising this, the MRC guidelines for developing and testing complex interventions place qualitative methods as integral to each stage of intervention development and implementation. However, mental health research has lagged behind many other healthcare specialities in using qualitative methods within its evidence base. Rigour in qualitative research raises many similar issues to quantitative research and also some additional challenges. This article examines the role of qualitative methods within mental heath research, describes key methodological and analytical approaches and offers guidance on how to differentiate between poor and good quality qualitative research.

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmh.13.2.35

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

The trajectory of qualitative methods in mental health research

Qualitative methodologies have a clear home within the study of mental health research. Early and, arguably, seminal work into the study of mental illnesses and their management was based on detailed observation, moving towards theory using inductive reasoning. Case studies have been long established in psychiatry to present detailed analysis of unusual cases or novel treatments. Participant observation was the principle method used in Goffman's seminal study of psychiatric patients in asylums that informed his ideas about the institutionalising and medicalising of mental illness by medical practice. 1 However, the 20th century saw the ‘behaviourist revolution’, a movement where quantification and experimentation dominated. Researchers sought to identify cause and effects, and reasoning became more deductive – seeking to use data to confirm theory. The study of health and illness was determined by contemporary thinking about disease, taking a biomedical stance. Psychologists and clinical health researchers exploited natural science methodologies, attempting to measure phenomenon in their smallest entities and do so as objectively as possible. This reductionist and positivist philosophy shaped advances in research methods and meant that qualitative exploration failed to develop as a credible scientific approach. Indeed, ‘objectivity’ and the ‘discovery of truth’ have become synonymous with ‘scientific enquiry’ and qualitative methods are easily dismissed as ‘anecdotal’. The underlying epistemology of this approach chimes well with medical practice for which training is predominately in laboratory and basic sciences (such as physics and chemistry) within which the discourse of natural laws dominate. To this end, research in psychiatry still remains overwhelmingly quantitative. 2

Underlying all research paradigms are assumptions. However, most traditional researchers remain unaware of these until they start to use alternative paradigms. Key assumptions of quantitative research are that facts exist that can be quantified and measured and that these should be examined, as far as possible, objectively, partialling out or controlling for the context within which they exist. There are research questions within mental health where this approach can hold: where phenomenon of interest can be reliably and meaningfully quantified and measured, it is feasible to use data to test predictions and examine change. However, for many questions these assumptions prove unsatisfying. It is often not possible or desirable to try and create laboratory conditions for the research; indeed it would be ecologically invalid to do so. For example, to understand the experience of an individual who has been newly diagnosed with schizophrenia, it is clearly important to consider the context within which they live, their family, social grouping and media messages they are exposed to. Table 1 depicts the key differences between the two methodological approaches and core underlying assumptions for each.

- View inline

Comparison of underlying assumptions of quantitative and qualitative research approaches

It should be cautioned that it is easy to fall into the trap of categorising studies as either quantitative or qualitative. The two traditions are often positioned within the literature as opposing and in conflict. This division is unhelpful and likely to impede methodological advancement. Though, undeniably, there are differences in the two approaches to research, there are also many exceptions that expose this dichotomy to be simplistic: some qualitative studies seek to test a priori hypotheses, and some quantitative studies are atheoretical and exploratory. 3 Hence it is more useful to consider research methodologies as lying along a spectrum and that researchers should be familiar with the full range of methodologies, so that a method is chosen according to the research question rather than the researcher's ability.

Rationale for qualitative methods in current mental health research

There are a number of scientific, practical and ethical reasons why mental health is an area that can particularly benefit from qualitative enquiry. Mental health research is complex. Health problems are multifactorial in their aetiology and the consequences they have on the individual, families and societies. Management can involve self-help, pharmacological, educative, social and psychotherapeutic approaches. Services involved are often multidisciplinary and require liaison between a number of individuals including professionals, service-users and relatives. Many problems are exacerbated by poor treatment compliance and lack of access to, or engagement with, appropriate services. 4

Engagement with mental health research can also be challenging. Topics may be highly sensitive or private. Individuals may have impaired capacity or be at high risk. During the research process there may be revelations of suicidal ideation or criminal activity. Hence mental health research can raise additional ethical issues. In other cases scepticism of services makes for reluctant research participants. However, if we accept the case that meaningful research can be based in subjective enquiry then qualitative methods provide a way of giving voice to participants. Qualitative methods offer an effective way of involving service-users in developing interventions for mental health problems 5 ensuring that the questions asked are meaningful to individuals. This may be particularly beneficial if participants are stakeholders, for example potential users of a new service.

Qualitative methods are valuable for individuals who have limited literacy skills who struggle with pencil and paper measures. For example qualitative research has proved fruitful in understanding children's concepts of mental illness and associated services. 6

How qualitative enquiry is used within mental health research

There are a range of types of research question where qualitative methods prove useful – from the development and testing of theory, to the piloting and establishing efficacy of treatment approaches, to understanding issues around translation and implementation into routine practice. Each is discussed in turn.

Development and testing of theory

Qualitative methods are important in exploratory work and in generating understanding of a phenomenon, stimulating new ideas or building new theory. For example, stigma is a concept that is recognised as a barrier to accessing services and also an added burden to mental health. A focus-group study sought to understand the meaning of stigma from the perspectives of individuals with schizophrenia, their relatives and health professionals. 7 From this they developed a four-dimensional theory which has subsequently informed interventions to reduce stigma and discrimination that target not only engagement with psychiatric services but also interactions with the public and work. 7

Development of tools and measures

Qualitative methods access personal accounts, capturing how individuals talk about a lived experience. This can be invaluable for designing new research tools. For example, Mavaddat and colleagues used focus groups with 56 patients with severe or common mental health problems to explore their experiences of primary care management. 8 Nine focus groups were conducted and analysis identified key themes. From these, items were generated to form a Patient Experience Questionnaire, of which the psychometric properties were subsequently examined quantitatively in a larger sample. Not only can dimensions be identified, the rich qualitative data provide terminology that is meaningful to service users that can then be incorporated into question items.

Development and testing of interventions

As we have seen, qualitative methods can inform the development of new interventions. The gold-standard methodology for investigating treatment effectiveness is the randomised controlled trial (RCT), with the principle output being an effect size or demonstration that the primary outcome was significantly improved for participants in the intervention arm compared with those in the control/comparison arm. Nevertheless, what will be familiar for researchers and clinicians involved in trials is that immense research and clinical learning arises from these substantial, often lengthy and expensive research endeavours. Qualitative methods provide a means to empirically capture these lessons, whether they are about recruitment, therapy training/supervision, treatment delivery or content. These data are essential to improve the feasibility and acceptability of further trials and developing the intervention. Conducting qualitative work prior to embarking on an RCT can inform the design, delivery and recruitment, as well as engage relevant stakeholders early in the process; all of these can prevent costly errors. Qualitative research can also be used during a trial to identify reasons for poor recruitment: in one RCT, implementing findings from this type of investigation led to an increased randomisation rate from 40% to 70%. 9

Nesting qualitative research within a trial can be viewed as taking out an insurance policy as data are generated which can later help explain negative or surprising findings. A recent trial of reattribution training for GPs to manage medically unexplained symptoms demonstrated substantial improvements in GP consultation behaviour. 10 However, effects on clinical outcomes were counterintuitive. A series of nested qualitative studies helped shed light as to why this was the case: patients' illness models were complex, and they resisted engaging with GPs (who they perceived as having more simplistic and dualistic understanding) because they were anxious it would lead to non-identification or misdiagnosis of any potential future disease 11 , an issue that can be addressed in future interventions. Even if the insights are unsurprising to those involved in the research, the data collected have been generated systematically and can be subjected to peer review and disseminated. For this reason, there is an increasing expectation from funding bodies that qualitative methodologies are integral to psychosocial intervention research.

Translation and implementation into clinical practice

Trials provide limited information about how treatments can be implemented into clinical practice or applied to another context. Psychological interventions are more effective when delivered within trial settings by experts involved in their development than when they are delivered within clinical settings. 12 Qualitative methods can help us understand how to implement research findings into routine practice. 13

Understanding what stakeholders value about a service and what barriers exist to its uptake is another evidence base to inform clinicians' practice. Relapse prevention is an effective psychoeducation approach that helps individuals with bipolar disorder extend time to relapse. Qualitative methodologies identified which aspects of the intervention service-users and care-coordinators value, and hence, are likely to utilise in routine care. 14 The intervention facilitated better understanding of bipolar disorder (by both parties), demonstrating, in turn, a rationale for medication. Patients discovered new, empowering and less socially isolated ways of managing their symptoms, which had important impacts on interactions with healthcare staff and family members. Furthermore, care-coordinators' reported how they used elements of the intervention when working with clients with other diagnoses. The research also provided insights as to where difficulties may occur when implementing a particular intervention into routine care. For example, for care-coordinators this proved a novel way of working with clients that was more emotionally demanding, thus highlighting the need for supervision and managerial support. 14

Beginners guide to qualitative approaches: one size doesn't fit all

Just as there is a range of quantitative research designs and statistical analyses to choose from, so there are many types of qualitative methods. Choosing a method can be daunting to an inexperienced or beginner-level qualitative researcher, for it requires engaging with new terms and ways of thinking about knowledge. The following summary sets out analytic and data-generation approaches that are used commonly in mental health research. It is not intended to be comprehensive and is provided only as a point of access/familiarisation to researchers less familiar with the literature.

Data generation

Qualitative data are generated in several ways. Most commonly, researchers seek a sample and conduct a series of individual in-depth interviews, seeking participants' views on topics of interest. Typically these last upwards of 45 min and are organised on the basis of a schedule of topics identified from the literature or pilot work. This does not act as a questionnaire, however; rather, it acts as a flexible framework for exploring areas of interest. The researcher combines open questions to elicit free responses, with focused questions for probing and prompting participants to provide effective responses. Usually interviews are audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for subsequent analysis.

As interviews are held in privately, and on one-to-one basis, they provide scope to develop a trusting relationship so that participants are comfortable disclosing socially undesirable views. For example, in a study of practice nurses views of chronic fatigue syndrome, some nurses described patients as lazy or illegitimate – a view that challenges the stereotype of a nursing professional as a sympathetic and caring person. 15 This gives important information about the education and supervision required to enable or train general nurses to ensure that they are capable of delivering psychological interventions for these types of problems.

Alternatively, groups of participants are brought together for a focus group, which usually lasts for 2 hours. Although it is tempting to consider focus groups as an efficient way of acquiring data from several participants simultaneously, there are disadvantages. They are difficult to organise for geographically dispersed or busy participants, and there are compromises to confidentiality, particularly within ‘captive’ populations (eg, within an organisation individuals may be unwilling to criticise). Group dynamics must be considered; the presence of a dominant or self-professed expert can inhibit the group and, therefore, prevent useful data generation. When the subject mater is sensitive, individuals may be unwilling to discuss experiences in a group, although it often promotes a shared experience that can be empowering. Most of these problems are avoided by careful planning of the group composition and ensuring the group is conducted by a highly skilled facilitator. Lester and colleagues 16 used focus-group sessions with patients and health professionals to understand the experience of dealing with serious mental illness. Though initially participants were observed via focus-group sessions that used patient-only and health professional only groups, subsequently on combined focus groups were used that contained both patients and health professionals. 16 The primary advantage of focus groups is that they enable generation of data about how individuals discuss and interact about a phenomenon; thus, a well-conducted focus group can be an extremely rich source of data.

A different type of data are naturally occurring dialogue and behaviours. These may be recorded through observation and detailed field notes (see ethnography in Table 2 ) or analysed from audio/ video-recordings. Other data sources include texts, for example, diaries, clinical notes, Internet blogs and so on. Qualitative data can even be generated through postal surveys. We thematically analysed responses to an open-ended question set within a survey about medical educators' views of behavioural and social sciences (BSS). 17 From this, key barriers to integrating BSS within medical training were identified, which included an entrenched biomedical mindset. The themes were analysed in relation to existing literature and revealed that despite radical changes in medical training, the power of the hidden curriculum persists. 17

Key features of a range of analytical approaches used within mental health research

Analysing qualitative data

Researchers bring a wide range of analytical approaches to the data. A comprehensive and detailed discussion of the philosophy underlying different methods is beyond the scope of this paper; however, a summary of the key analytical approaches used in mental health research are provided in Table 2 . An illustrative example is provided for each approach to offer some insight into the commonalities and differences between methodologies. The procedure for analysis for all methods involves successive stages of data familiarisation/immersion, followed by seeking and reviewing patterns within the data, which may then be defined and categorized as specific themes. Researchers move back and forth between data generation and analysis, confirming or disconfirming emerging ideas. The relationship of the analysis to theory-testing or theory-building depends on the methodology used.

Some approaches are more common in healthcare than others. Interpretative phenomenological (lPA) analysis and thematic analysis have proved particularly popular. In contrast, ethnographic research requires a high level of researcher investment and reflexivity and can prove challenging for NHS ethic committees. Consequently, it remains under used in healthcare research.

Recruitment and sampling

Quantitative research is interested in identifying the typical, or average. By contrast, qualitative research aims to discover and examine the breadth of views held within a community. This includes extreme or deviant views and views that are absent. Consequently, qualitative researchers do not necessarily (though in some circumstances they may) seek to identify a representative sample. Instead, the aim may be to sample across the range of views. Hence, qualitative research can comment on what views exist and what this means, but it is not possible to infer the proportions of people from the wider population that hold a particular view.

However, sampling for a qualitative study is not any less systematic or considered. In a quantitative study one would take a statistical approach to sampling, for example, selecting a random sample or recruiting consecutive referrals, or every 10th out-patient attendee. Qualitative studies, instead, often elect to use theoretical means to identify a sample. This is often purposive; that is, the researcher uses theoretical principles to choose the attributes of included participants. Healey and colleagues conducted a study to understand the reasons for individuals with bipolar disorder misusing substances. 18 They sought to include participants who were current users of each substance group, and the recruitment strategy evolved to actively target specific cases.

Qualitative studies typically use far smaller samples than quantitative studies. The number varies depending on the richness of the data yielded and the type of analytic approach that can range from a single case to more than 100 participants. As with all research, it is unethical to recruit more participants than needed to address the question at hand; a qualitative sample should be sufficient for thematic saturation to be achieved from the data.

Ensuring that findings are valid and generalisable

A common question from individuals new to qualitative research is how can findings from a study of few participants be generalised to the wider population? In some circumstances, findings from an individual study (quantitative or qualitative) may have limited generalisability; therefore, more studies may need to be conducted, in order to build local knowledge that can then be tested or explored across similar groups. 4 However, all qualitative studies should create new insights that have theoretical or clinical relevance which enables the study to extend understanding beyond the individual participants and to the wider population. In some cases, this can lead to generation of new theory (see grounded theory in Table 2 ).

Reliability and validity are two important ways of ascertaining rigor in quantitative research. Qualitative research seeks to understand individual construction and, by definition, is subjective. It is unlikely, therefore, that a study could ever be repeated with exactly the same circumstances. Instead, qualitative research is concerned with the question of whether the findings are trustworthy; that is, if the same circumstances were to prevail, would the same conclusions would be drawn?

There are a number of ways to maximise trustworthiness. One is triangulation, of which there are three subtypes. Data triangulation involves using data from several sources (eg, interviews, documentation, observation). A research team may include members from different backgrounds (eg, psychology, psychiatry, sociology), enabling a range of perspectives to be used within the discussion and interpretation of the data. This is termed researcher triangulation . The final subtype, theoretical triangulation, requires using more than one theory to examine the research question. Another technique to establish the trustworthiness of the findings is to use respondent validation. Here, the final or interim analysis is presented to members of the population of interest to ascertain whether interpretations made are valid.

An important aspect of all qualitative studies is researcher reflexivity. Here researchers consider their role and how their experience and knowledge might influence the generation, analysis and interpretation of the data. As with all well-conducted research, a clear record of progress should be kept – to enable scrutiny of recruitment, data generation and development of analysis. However, transparency is particularly important in qualitative research as the concepts and views evolve and are refined during the process.

Judging quality in qualitative research

Within all fields of research there are better and worse ways of conducting a study, and range of quality in mental health qualitative research is variable. Many of the principles for judging quality in qualitative research are the same for judging quality in any other type of research. However, several guidelines have been developed to help readers, reviewers and editors who lack methodological expertise to feel more confident in appraising qualitative studies. Guidelines are a prerequisite for the relatively recent advance of methodologies for systematic reviewing of qualitative literature (see meta-synthesis in Table 2 ). Box 1 provides some key questions that should be considered while studying a qualitative report.

Box 1 Guidelines for authors and reviewers of qualitative research (adapted from Malterud 35 )

▶ Is the research question relevant and clearly stated?

Reflexivity

▶ Are the researcher's motives and background presented?

Method, sampling and data collection

▶ Is a qualitative method appropriate and justified?

▶ Is the sampling strategy clearly described and justified?

▶ Is the method for data generation fully described

▶ Are the characteristics of the sample sufficiently described?

Theoretical framework

▶ Was a theoretical framework used and stated?

▶ Are the principles and procedures for data organisation and analysis described and justified?

▶ Are strategies used to test the trustworthiness of the findings?

▶ Are the findings relevant to the aim of the study?

▶ Are data (e.g. quotes) used to support and enrich the findings?

▶ Are the conclusions directly linked to the study? Are you convinced?

▶ Do the findings have clinical or theoretical value?

▶ Are findings compared to appropriate theoretical and empirical literature?

▶ Are questions about the internal and external validity and reflexivity discussed?

▶ Are shortcomings of the design, and the implications these have on findings, examined?

▶ Are clinical/theoretical implications of the findings made?

Presentation

▶ Is the report understandable and clearly contextualised?

▶ Is it possible to distinguish between the voices of informants and researchers?

▶ Are sources from the field used and appropriately referenced?

Conclusions and future directions

Qualitative research has enormous potential within the field of mental health research, yet researchers are only beginning to exploit the range of methods they use at each stage of enquiry. Strengths of qualitative research primarily lie in developing theory and increasing understanding about effective implementation of treatments and how best to support clinicians and service users in managing mental health problems. An important development in the field is how to integrate methodological approaches to address questions. This raises a number of challenges, such as how to integrate textual and numerical data and how to reconcile different epistemologies. A distinction can be made between mixed- method design (eg, quantitative and qualitative data are gathered and findings combined within a single or series of studies) and mixed- model study, a pragmatist approach, whereby aspects of qualitative and quantitative research are combined at different stages during a research process. 19 Qualitative research is still often viewed as only a support function or as secondary to quantitative research; however, this situation is likely to evolve as more researchers gain a broader skill set.

Though it is undeniable that there has been a marked increase in the volume and quality of qualitative research published within the past two decades, mental health research has been surprisingly slow to develop, compared to other disciplines e.g. general practice and nursing, with relatively fewer qualitative research findings reaching mainstream psychiatric journals. 2 This does not appear to reflect overall editorial policy; however, it may be partly due to the lack of confidence on the part of editors and reviewers while identifying rigorous qualitative research data for further publication. 20 However, the skilled researcher should no longer find him or herself forced into a position of defending a single-methodology camp (quantitative vs qualitative), but should be equipped with the necessary methodological and analytical skills to study and interpret data and to appraise and interpret others' findings from a full range of methodological techniques.

- Crawford MJ ,

- Cordingley L

- Dowrick C ,

- Edwards S ,

- ↵ MRC Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions 2008

- Nelson ML ,

- Quintana SM

- Schulze B ,

- Angermeyer MC

- Mavaddat N ,

- Lester HE ,

- Donovan J ,

- Morriss R ,

- Barkham M ,

- Stiles WB ,

- Connell J ,

- Chew-Graham C ,

- England E ,

- Kinderman P ,

- Tashakkoria A ,

- Ritchie J ,

- Ssebunnya J ,

- Chilvers R ,

- Glasman D ,

- Finlay WM ,

- Strauss A ,

- Hodges BD ,

- Dobransky K

- Dixon-Woods M ,

- Fitzpatrick R ,

- Espíndola CR ,

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Qualitative Research in Mental Health and Mental Illness

Cite this chapter.

- Rebecca Gewurtz Ph.D. O.T. Reg. (Ont.) 6 ,

- Sandra Moll Ph.D. O.T. Reg. (Ont.) 6 ,

- Jennifer M. Poole M.S.W., Ph.D. 7 &

- Karen Rebeiro Gruhl Ph.D., M.Sc. O.T. OT. Reg. (Ont) 8

Part of the book series: Handbooks in Health, Work, and Disability ((SHHDW,volume 4))

4491 Accesses

5 Citations

In this chapter we present an overview of qualitative research in the mental health field. We provide an historical account of the vital role that qualitative methods have played in the development of theoretical and practice approaches of psychiatry, and their current use in contemporary mental health practice. We consider how different approaches to qualitative research are used to advance knowledge and understanding of mental health, mental illness, and related services and systems, as well as the contributions of qualitative research to the mental health field. We then provide a synthesis of evidence derived from qualitative research within the mental health sector, spanning four key areas: (1) recovery, (2) stigma, (3) employment, and (4) housing. We conclude this chapter with a review of the ongoing challenges facing qualitative researchers in this area.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

By Mad we are referring to a term now used by many individuals to self-identify their experiences with diagnosis, treatment and mental health services. As outlined in the new Canadian Mad Studies reader, Mad Matters (LeFrancois et al. 2013 ), Mad may refer to a movement, an identity, a stance, an act of resistance, a theoretical approach and a burgeoning field of study. There are many ways to take up a Mad analysis, and they may be informed by multiple ideas from Anti-oppressive social work practice (AOP), Intersectionality, Queer Studies, and the Social model of disability for instance.

Abberley, P. (2004). A critique of professional support and intervention. In J. Swain, S. French, C. Barnes, & C. Thomas (Eds.), Disabling barriers - - Enabling environments (2nd ed., pp. 239–244). London: Sage.

Google Scholar

Abbey, S. E., De Luca, E., Mauthner, O. E., McKeever, P., Shildrick, M., Poole, J. M., et al. (2011). Qualitative interviews vs standardized self-report questionnaires in assessing quality of life in heart transplant recipients. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, 30 (8), 963–966.

PubMed Google Scholar

Alverson, M., Becker, D., & Drake, R. (1995). An ethnographic study of coping strategies used by people with severe mental illness participating in supported employment. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 18 (4), 115–128.

Article Google Scholar

Auerbach, E. S., & Richardson, P. (2005). The long-term work experiences of persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 28 , 267. doi: 10.2975/28.2005.267.273 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Baarnhielm, S., & Ekblad, S. (2002). Qualitative research, culture and ethics: A case discussion. Transcultural Psychiatry, 39 (4), 469–483.

Baines, D. (Ed.). (2007). Doing anti-oppressive practice: Building transformative, politicized social work . Halifax, NS: Fernwood.

Bassett, H., Lampe, J., & Lloyd, C. (1999). Parenting: Experiences and feelings of parents with a mental illness. Journal of Mental Health, 8 , 597. doi: 10.1080/09638239917067 .

Beresford, P., & Wallcraft, J. (1997). Psychiatric system survivors and emancipatory research: Issues, overlaps and differences. In C. Barnes & G. Mercer (Eds.), Doing disability research (pp. 66–87). Leeds: Disability Press.

Bertilsson, M., Petersson, E.-L., Ostlund, G., Waern, M., & Hensing, G. (2013). Capacity to work while depressed and anxious – A phenomenological study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35 , 1705. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.751135 .

Blumer, H. (1986). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Borg, M., & Davidson, L. (2008). The nature of recovery as lived in everyday experience. Journal of Mental Health, 17 , 129. doi: 10.1080/09638230701498382 .

Bourdieu, P. (1990). In other words: Essays towards a reflexive sociology . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bracken, P., Thomas, P., Timimi, S., Asen, E., Behr, G., Beuster, C., et al. (2012). Psychiatry beyond the current paradigm. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 201 , 430. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.109447 .

Campbell, M., & Gregor, F. (2008). Mapping social relations: A primer in doing institutional ethnography . Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Chamberlin, J. (1990). The ex-patients’ movement: Where we’ve been and where we’re going. Journal of Mind and Behaviour, 11 (3), 323–336.

Chamberlin, J. (2005). User/consumer involvement in mental health service delivery. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 14 (1), 10–14.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

Cheek, J. (2011). The politics and practices of funding qualitative inquiry: Messages about messages about messages.... In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), THe SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 251–268). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications, Inc.

Church, K. (1995). Forbidden narratives: Critical autobiography as social science . Amsterdam: International Publishers Distributors. Reprinted by Routledge, London.

Church, K. (1997). Because of where we’ve been: The business behind the business of psychiatric survivor economic development . Toronto, ON: Ontario Council of Alternative Businesses.

Church, K., & Reville, D. (2001). “First we take Manhattan”: Evaluation report on a community connections grant OCAB Regional Council Development . Toronto, ON: Ontario Council of Alternative Businesses.

Cohen, O. (2005). How do we recover? An analysis of psychiatric survivor oral histories. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 45 (3), 333–354.

Costa, L., Voronka, J., Landry, D., Reid, J., McFarlane, B., Reville, D., et al. (2012). Recovering our stories: A small act of resistance. Studies in Social Justice, 6 (1), 85–101.

Crawford, M. J., Ghosh, P., & Keen, R. (2003). Use of qualitative research methods in general medicine and psychiatry: Publication trends in medical journals 1990–2000. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 49 , 308. doi: 10.1177/0020764003494007 .

Cunningham, K., Wolbert, R., & Brockmeier, M. B. (2000). Moving beyond the illness: Factors contributing to gaining and maintaining employment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28 , 481. doi: 10.1023/A:1005136531079 .

Dalgin, R. S., & Gilbride, D. (2003). Perspectives of people with psychiatric disabilities on employment disclosure. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 26 (3), 306–310.

Davidson, L., Ridgway, P., Kidd, S., Topor, A., & Borg, M. (2008). Using qualitative research to inform mental health policy. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 53 (3), 137–144.

Davidson, L., & Strauss, J. (1992). Sense of self in recovery from severe mental illness. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 65 (2), 131–145.

De Haene, L., Grietens, H., & Verschueren, K. (2010). Holding harm: Narrative methods in mental health research on refugee trauma. Qualitative Health Research, 20 , 1664. doi: 10.1177/1049732310376521 .

Deegan, P. E. (1988). Recovery: The lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 11 (4), 11–19.

Deegan, P. E. (2005). The importance of personal medicine: A qualitative study of resilience in people with psychiatric disabilities. Scandinavian Journal Public Health Supplement, 66 , 29. doi: 10.1080/14034950510033345 .

Deegan, P. E. (2007). The lived experience of using psychiatric medicine in the recovery process and a shared decision making program to support it. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31 (1), 62–69.

Devlin, R., & Pothier, D. (2006). Introduction: Toward a critical theory of dis-citizenship. In D. Pothier & R. Devlin (Eds.), Dis-ability. Critical disability theory: Essays in philosophy, politics, policy and law (1st ed., pp. 1–22). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Dougherty, S., Campana, K., Kontos, R., Flores, M., Lockhart, R., & Shaw, D. (1996). Supported education: A qualitative study of the student experience. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 19 (3), 59–70.

Fabris, E. (2011). Tranquil prisons: Chemical incarceration under community treatment orders . Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Forrester-Jones, R., & Barnes, A. (2008). On being a girlfriend not a patient: The quest for an acceptable identity amongst people diagnosed with a severe mental illness. Journal of Mental Health, 17 , 153. doi: 10.1080/09638230701498341 .

Fossey, E. M., & Harvey, C. A. (2010). Finding and sustaining employment: A qualitative meta-synthesis of mental health consumer views. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 77 , 303. doi:10.2182/cjot.2010.77.5.6.

Foster-Fishman, P., & Nowell, B. (2005). Using methods that matter: The impact of reflection, dialogue and voice. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36 , 275. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8626-y .

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge- selected interviews and other writings 1972-1977 . New York: Pantheon Books.

Frances, A. (2013). Saving normal . New York: Harper Collins.

Gardner, P. J., & Poole, J. M. (2009). One story at a time narrative therapy, older adults, and addictions. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28 (5), 600–620.

Georgaca, E. (2013). Discourse analytic research on mental distress: A critical overview. Journal of Mental Health, 23 , 55. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2012.734648 .

Gewurtz, R. E., Cott, C., Rush, B., & Kirsh, B. (2012). The shift to rapid job placement for people living with mental illness: An analysis of consequences. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35 , 428. doi: 10.1037/h0094575 .

Gewurtz, R., Kirsh, B., Jacobson, N., & Rappolt, S. (2006). The influence of mental illnesses on work potential and career development. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 25 (2), 207–220.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Goering, P., Boydell, K. M., & Pignatiello, A. (2008). The relevance of qualitative research for clinical programs in psychiatry. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 53 (3), 145–151.

Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates . New York: Doubleday.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Gold, E. (2007). From narrative wreckage to islands of clarity: Stories of recovery from psychosis. Canadian Family Physician, 53 (8), 1271–1275.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gould, A., DeSouza, S., & Rebeiro Gruhl, K. (2005). And then I lost that life: A shared narrative of young men with schizophrenia. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68 (10), 467–473.

Hall, J. M. (2011). Narrative methods in a study of trauma recovery. Qualitative Health Research, 21 , 3. doi: 10.1177/1049732310377181 .

Haw, K., & Hadfield, M. (2011). Video in social science research: Function and forms . New York: Routledge.

Henry, A., & Lucca, A. (2004). Facilitators and barriers to employment: The perspectives of people with psychiatric disabilities and employment service providers. Work, 22 (3), 169–182.

Holmes, D., Murray, S., Perron, A., & Rail, G. (2006). Deconstructing the evidence-based discourse in health sciences: Truth, power and fascism. International Journal of Evidence Based Healthcare, 4 , 180. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-6988.2006.00041.x .

Honey, A. (2004). Benefits and drawbacks of employment: Perspectives of people with mental illness. Qualitative Health Research, 14 , 381. doi: 10.1177/1049732303261867 .

Israel, B. A., Eng, E., Schulz, A. J., & Parker, E. A. (Eds.). (2005). Methods in community-based participatory research for health . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Jacobson, N. (2001). Experiencing recovery: A dimensional analysis of recovery narratives. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 24 (3), 248–256.

Jacobson, N., Farah, D., & The Toronto and Cultural Diversity Community of Practice. (2010). Recovery through the lens of cultural diversity . Toronto, ON: The Wellesley Institute, Community Resources Connections of Toronto and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Johnson, M. (1998). Being mentally ill: A phenomenological inquiry. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 12 (4), 195–201.

Joseph, S., Beer, C., Forman, A., Pikersgill, M., Swift, J., Taylor, J., et al. (2009). Qualitative research into mental health: Reflections on epistemology. Mental Health Review Journal, 14 (1), 36–42.

Karnieli-Miller, O., Perlick, D. A., Nelson, A., Mattias, K., Corrigan, P., & Roe, D. (2013). Family members’ of persons living with a serious mental illness: Experiences and efforts to cope with stigma. Journal of Mental Health, 22 , 254. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2013.779368 .

Kartalova-O’Doherty, Y., Stevenson, C., & Higgins, A. (2012). Reconnecting with life: A grounded theory study of mental health recovery in Ireland. Journal of Mental Health, 21 , 135. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.621467 .

Kennedy-Jones, M., Cooper, J., & Fossey, E. (2005). Developing a worker role: Stories of four people with mental illness. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 52 , 116. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2005.00475.x .

Killeen, M. B., & O’Day, B. L. (2004). Challenging expectations: How individuals with psychiatric disabilities find and keep work. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 28 , 157. doi: 10.2975/28.2004.157.163 .

Kirsh, B. (1996). Influences on the process of work integration: The consumer perspective. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 15 (1), 21–31.

Kirsh, B. (2000). Work, workers, and workplaces: A qualitative analysis of narratives of mental health consumers. Journal of Rehabilitation, 66 (4), 24–30.

Kirsh, B., Gewurtz, R., & Bakewell, R. A. (2011). Critical characteristics of supported housing: Resident and service provider perspectives. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 30 (1), 15–30.

Kirsh, B., Krupa, T., Cockburn, L., & Gewurtz, R. (2010). A Canadian model of work integration for persons with mental illnesses. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32 , 1833. doi: 10.3109/09638281003734391 .

Knight, M., Wykes, T., & Hayward, P. (2003). ‘People don’t understand’: An investigation of stigma in schizophrenia using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). Journal of Mental Health, 12 , 209. doi: 10.1080/0963823031000118203 .

Krupa, T. (2004). Employment, recovery and schizophrenia: Integrating health and disorder at work. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 28 , 8. doi: 10.2975/28.2004.8.1 .

Krupa, T. (2008). Muriel Driver Memorial Lecture 2008: Part of the solution…or part of the problem? Addressing the stigma of mental illness in our midst. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75 (4), 198–205.

Krupa, T., Kirsh, B., Cockburn, L., & Gewurtz, R. (2009). Understanding the stigma of mental illness in employment. Work, 33 , 413. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2009-0890 .

Krupa, T., Kirsh, B., Gewurtz, R., & Cockburn, L. (2005). Improving the employment prospects of people with serious mental illness: Five challenges for a national mental health strategy. Canadian Public Policy, 31 (s1), 59–64.

Lane, A. M. (2011). Placement of older adults from hospital mental health units into nursing homes: Exploration of the process, system issues and implications. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 37 , 49. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20100730-07 .

Lather, P. (2004). Scientific research in education: A critical perspective. British Educational Research Journal, 30 (6), 759–772.

LeFrancois, B., Menzies, R., & Reaume, G. (Eds.). (2013). Mad matters: A critical reader in Canadian Mad Studies . Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars Press.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27 , 363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363 .

Lord, J., Schnarr, A., & Hutchison, P. (1987). The voice of the people: Qualitative research and the needs of consumers. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 6 (2), 25–36.

Lurie, S., Kirsh, B., & Hodge, S. (2007). Can ACT lead to more work? The Ontario experience. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 26 (1), 161–171.

Mancini, M. (2007). A qualitative analysis of turning points in the recovery process. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 10 (3), 223–244.

Mental health recovery study working group. (2009). Mental health ‘recovery’: Users and refusers . Toronto, ON: The Wellesley Institute.

Michalak, E., Livingston, J., Hole, R., Suto, M., Hale, S., & Haddock, C. (2011). ‘It’s something that I manage but it is not who I am’: Reflections on internalized stigma in individuals with bipolar disorder. Chronic Illness, 7 , 209. doi: 10.1177/1742395310395959 .

Moll, S. (2012). Navigating political minefields: Partnerships in organizational case study research. Work: A Journal of Prevention, Treatment and Rehabilitation, 43 , 5. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-1442 .

Moll, S., Dick, R., Sherman, D., & Dahan, R. (2006). Photovoice: Transforming marginalized communities through photography. Presentation at the Making Gains in Mental Health and Addictions Conference. Toronto, ON, Canada.

Moll, S., Eakin, J. M., Franche, R. L., & Strike, C. (2013). When health care workers experience mental ill health: Institutional practices of silence. Qualitative Health Research, 23 , 167. doi: 10.1177/1049732312466296 .

Moran, G. S., Russinova, Z., Gidugu, V., Yim, J., & Sprague, C. (2012). Benefits and mechanisms of recovery among peer providers with psychiatric illnesses. Qualitative Health Research, 22 , 304. doi: 10.1177/1049732311420578 .

Morrow, M. (2013). Recovery: Progressive paradigm or neoliberal smokescreen? In B. LeFrancois, R. Menzies, & G. Reaume (Eds.), Mad matters: A critical reader in Canadian Mad Studies (pp. 323–333). Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Morse, J. M. (2009). Mixing qualitative methods. Qualitative Health Research, 19 , 1523. doi: 10.1177/1049732309349360 .

Morse, J.M. (2003). The adjudication of qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 739–742.

Moss, P. A., Phillips, D. C., Erickson, F. D., Floden, R. E., Lather, P. A., & Schneider, B. L. (2009). Learning from our differences: A dialogue across perspectives on quality in education research. Educational Research, 38 (7), 501–507.

Nelson, G., Clarke, J., Febbraro, A., & Hatzipantelis, M. (2005). A narrative approach to the evaluation of supportive housing: Stories of homeless people who have experienced serious mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29 (2), 98–104.

Noordik, E., Nieuwenhuijsen, K., Varekamp, I., van der Klink, J. J., & van Dijk, F. J. (2011). Exploring the return-to-work process for workers partially returned to work and partially on long-term sick leave due to common mental disorders: A qualitative study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33 (17-18), 1625–1635.

Ochocka, J., Nelson, G., & Janzen, R. (2005). Moving forward: Negotiating self and external circumstances in recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 28 (4), 315–322.

Oliver, M. (2006). Social policy and disability: Some theoretical issues. In L. Barton (Ed.), Overcoming disabling barriers: 18 years of disability and society (pp. 7–20). Oxford: Routledge.

Pease, B. (2002). Rethinking empowerment: A postmodern reappraisal for emancipatory practice. British Journal of Social Work, 32 (2), 135–147.

Perlin, M. L. (1992). On sanism. SMULaw Review, 46 , 373.

Perry, B., Taylor, D., & Shaw, S. (2007). “You’ve got to have a positive state of mind”: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of hope and first episode psychosis. Journal of Mental Health, 16 , 781. doi: 10.1080/09638230701496360 .

Pescosolido, B. A., Martin, J. K., Lang, A., & Olafsdottir, S. (2008). Rethinking theoretical approaches to stigma: A Framework Integrating Normative Influences on Stigma (FINIS). Social Science and Medicine, 67 , 431. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.018 .

Peters, S. (2010). Qualitative research methods in mental health. Evidence Based Mental Health, 13 , 35. doi: 10.1136/ebmh.13.2.35 .

Phillips, N., & Hardy, C. (2002). Discourse analysis . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Piat, M., & Lal, S. (2012). Service providers’ experiences and perspectives on recovery-oriented mental health system reform. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35 (4), 289–296.

Pickens, J. (1999). Living with serious mental illness: The desire for normalcy. Nursing Science Quarterly, 12 (3), 233–239.

Pink, S. (2006). Doing visual ethnography . London: Sage Press.

Polvere, L., Macnaughton, E., & Piat, M. (2013). Participant perspectives on housing first and recovery: Early findings from the at home/chez soi project. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 36 , 110. doi: 10.1037/h0094979 .

Poole, J. (2011). Behind the rhetoric: Mental health recovery in Ontario . Halifax, NS: Fernwood.

Poole, J. M., Jivraj, T., Arslanian, A., Bellows, K., Chiasson, S., Hakimy, H., et al. (2012). Sanism, ‘mental health’, and social work/education: A review and call to action. Intersectionalities: A Global Journal of Social Work Analysis, Research, Polity, and Practice, 1 (1), 20–36.

Poole, J. M., Shildrick, M., De Luca, E., Abbey, S. E., Mauthner, O. E., McKeever, P. D., et al. (2011). The obligation to say ‘Thank You’: Heart transplant recipients’ experience of writing to the donor family. American Journal of Transplantation, 11 (3), 619–622.

Poole, J., & Ward, J. (2013). ‘Breaking open the bone’: Storying, sanism and mad grief. In B. LeFrancois, R. Menzies, & G. Reaume (Eds.), Mad matters: A critical reader in Canadian Mad Studies (pp. 94–104). Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Rebeiro, K. (1999). The labyrinth of community mental health: In search of meaningful occupation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 23 (2), 143–152.

Rebeiro Gruhl, K. L. (2011). An exploratory study of the influence of place on access to employment for persons with serious mental illness residing in northeastern Ontario . (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). School of Rural and Northern Health, Laurentian University, Sudbury, ON.

Rebeiro Gruhl, K. L., Kauppi, C., Montgomery, P., & James, S. (2012a). “Stuck in the mud”: Limited employment success of persons with serious mental illness in northeastern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 31 (2), 67–81.

Rebeiro Gruhl, K. L., Kauppi, C., Montgomery, P., & James, S. (2012b). Consideration of the influence of place on access to employment for persons with serious mental illness in northeastern Ontario. Rural and Remote Health, Spring/Summer, 36 (1), 11–17.

Rebeiro, K. L., Day, D. G., Semeniuk, B., O’Brien, M. C., & Wilson, B. (2001). NISA: An occupation-based, mental health program. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55 (5), 493–500.

Ridgway, P. (2001). ReStorying psychiatric disability: Learning from first person recovery narratives. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 24 (4), 335–343.

Rioux, M., & Valentine, F. (2006). Does theory matter? Exploring the nexus between disability, human rights and public policy. In D. Pothier & R. Devlin (Eds.), Dis ability. Critical disability theory: Essays in philosophy, politics, policy and law (1st ed., pp. 47–69). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Rose, L. (1998). Gaining control: Family members relate to persons with severe mental illness. Research in Nursing & Health, 21 (4), 363–373.

Ross, H., Abbey, S., De Luca, E., Mauthner, O., McKeever, P., Shildrick, M., et al. (2010). What they say versus what we see: “Hidden” distress and impaired quality of life in heart transplant recipients. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, 29 (10), 1142–1149.

Rothgeb, C. L. (1971). Abstracts of the standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud . Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

Book Google Scholar

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Focus on research methods: Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and data analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Research in Nursing & Health, 23 (3), 246–255.

Schulze, B. (2008). Qualitative research methods in psychiatric science. European Psychiatry, 23 , S48. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.01.174 .

Schulze, B., & Angermeyer, M. (2003). Subjective experiences of stigma. A focus group study of schizophrenic patients, their relatives and mental health professionals. Social Science & Medicine, 56 (2), 299–312.

Secker, J., Armstrong, C., & Hill, M. (1999). Young people’s understanding of mental illness. Health Education Research, 14 , 729–739. doi: 10.1093/her/14.6.729 .

Shankar, J. (2005). Improving job tenure for people with psychiatric disabilities through ongoing employment. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 4 (1), 1–11. Retrieved from www.ausienet.com/journal/vol4iss1/shankar.pdf

Smith, D. (2006). Institutional ethnography: A sociology for the people . Oxford: AltaMira.

Stapleton, J. (2010). “Zero Dollar Linda”: A mediation on Malcolm Gladwell’s “Million D ollar Murray,” the Linda Chamberlain Rule, and the Auditor General of Ontario. The Metcalf Foundation. Available at http://www.openpolicyontario.com/ZeroDollarLindaf.pdf

Strauss, J. S. (1989). Subjective experiences of schizophrenia: Towards a new dynamic psychiatry – II. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 15 (2), 179–187.

Streiner, D. L. (2008). Qualitative research in psychiatry. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 53 (3), 135–136.

Sutton, D. J., Hocking, C. S., & Smythe, L. A. (2012). A phenomenological study of occupational engagement in recovery from mental illness. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79 , 142. doi: 10.2182/cjot.2012.79.3.3 .

Sveinbjarnardottir, E., & de Casterle, B. (1997). Mental illness in the family: An emotional experience. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 18 (1), 45–56.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.). (2003). Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

The Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. (2006). Out of the shadows at last: Transforming mental health, mental illness and addiction services in Canada . Available at http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/SEN/Committee/391/soci/rep/rep02may06-e.htm

Townsend, E. (1998). Good intentions over-ruled: A critique of empowerment in the routine organization of mental health services . Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Twohig, P. L. (2007). Written on the landscape: Health and region in Canada. Journal of Canadian Studies, 41 (3), 5–17.

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24 , 369. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400 .

Wang, C., Cash, J. L., & Powers, L. S. (2000). Who knows the streets as well as the homeless? Promoting personal and community action through photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 1 , 81. doi: 10.1177/152483990000100113 .

Weiner, E. (1999). The meaning of education for university students with a psychiatric disability: A grounded theory analysis. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 22 (4), 403–409.

Whitley, R., Harris, M., & Drake, R. (2008). Safety and security in small-scale recovery housing for people with severe mental illness: An inner-city case study. Psychiatric Services, 59 (2), 165–169.

Wiersma, E. C. (2011). Using Photovoice with people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease: A discussion of methodology. Dementia, 10 , 203. doi: 10.1177/1471301211398990 .

Young, S., & Ensing, D. (1999). Exploring recovery from the perspective of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 22 (3), 219–231.

Young, N. L., Wabano, M. J., Burke, T. A., Ritchie, S. D., Mishibinijima, D., & Corbiere, R. G. (2013). A process for creating the Aboriginal Children’s Health and Well-being Measure (ACHWM). Canadian Journal of Public Health, 104 (2), 136–141.

Zolnierek, C. D. (2011). Exploring lived experiences of persons with severe mental illness: A review of the literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32 , 46. doi:10.3109/01612840.2010.522755.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, IAHS Bldg, 4th Floor, 1400 Main St. W., Hamilton, ON, Canada, L8S 1C7

Rebecca Gewurtz Ph.D. O.T. Reg. (Ont.) & Sandra Moll Ph.D. O.T. Reg. (Ont.)

School of Social Work, Faculty of Community Services, Ryerson University, 350 Victoria Street, Toronto, ON, Canada, M5B 2K3

Jennifer M. Poole M.S.W., Ph.D.

Community Mental Health and Addictions Program, Health Sciences North, 127 Cedar Street, Sudbury, ON, Canada, P3E 1B1

Karen Rebeiro Gruhl Ph.D., M.Sc. O.T. OT. Reg. (Ont)

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rebecca Gewurtz Ph.D. O.T. Reg. (Ont.) .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Karin Olson

Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology, and Special Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Richard A. Young

Izabela Z. Schultz

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Gewurtz, R., Moll, S., Poole, J.M., Gruhl, K.R. (2016). Qualitative Research in Mental Health and Mental Illness. In: Olson, K., Young, R., Schultz, I. (eds) Handbook of Qualitative Health Research for Evidence-Based Practice. Handbooks in Health, Work, and Disability, vol 4. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2920-7_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2920-7_13

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4939-2919-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-4939-2920-7

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 13 October 2023

A qualitative exploration of young people’s mental health needs in rural and regional Australia: engagement, empowerment and integration

- Christiane Klinner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9313-6799 1 ,

- Nick Glozier 1 , 2 ,

- Margaret Yeung 1 ,

- Katrina Conn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0476-9146 1 , 3 &

- Alyssa Milton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4326-0123 1 , 2

BMC Psychiatry volume 23 , Article number: 745 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2967 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

Australian rural and regional communities are marked by geographic isolation and increasingly frequent and severe natural disasters such as drought, bushfires and floods. These circumstances strain the mental health of their inhabitants and jeopardise the healthy mental and emotional development of their adolescent populations. Professional mental health care in these communities is often inconsistent and un-coordinated. While substantial research has examined the barriers of young people’s mental health and help-seeking behaviours in these communities, there is a lack of research exploring what adolescents in rural and regional areas view as facilitators to their mental health and to seeking help when it is needed. This study aims to establish an in-depth understanding of those young people’s experiences and needs regarding mental health, what facilitates their help-seeking, and what kind of mental health education and support they want and find useful.

We conducted a qualitative study in 11 drought-affected rural and regional communities of New South Wales, Australia. Seventeen semi-structured (14 group; 3 individual) interviews were held with 42 year 9 and 10 high school students, 14 high school staff, and 2 parents, exploring participants’ experiences of how geographical isolation and natural disasters impacted their mental health. We further examined participants’ understandings and needs regarding locally available mental health support resources and their views and experiences regarding mental illness, stigma and help-seeking.

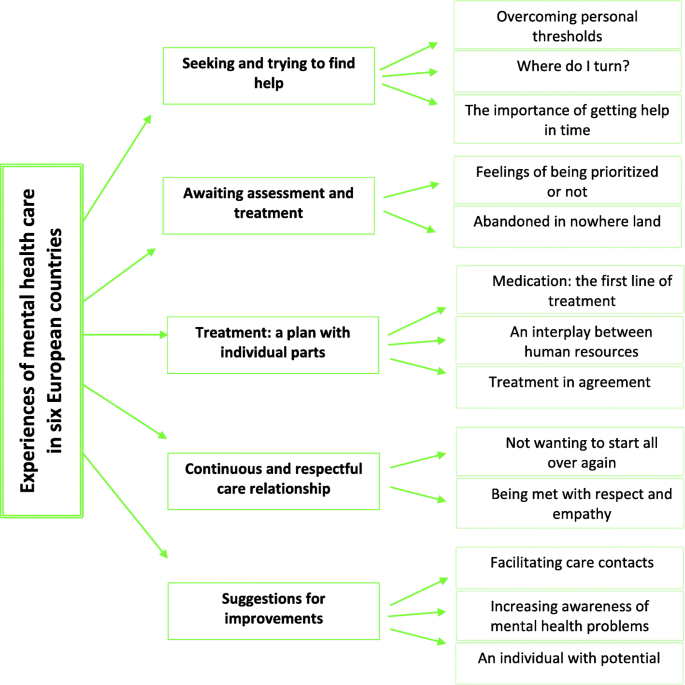

Thematic analysis highlighted that, through the lens of participants, young people’s mental health and help-seeking needs would best be enabled by a well-coordinated multi-pronged community approach consisting of mental health education and support services that are locally available, free of charge, engaging, and empowering. Participants also highlighted the need to integrate young people’s existing mental health supporters such as teachers, parents and school counselling services into such a community approach, recognising their strengths, limitations and own education and support needs.

Conclusions

We propose a three-dimensional Engagement, Empowerment, Integration model to strengthen young people’s mental health development which comprises: 1) maximising young people’s emotional investment (engagement); 2) developing young people’s mental health self-management skills (empowerment); and, 3) integrating mental health education and support programs into existing community and school structures and resources (integration).

Peer Review reports

Mental health service use is considerably lower in rural and regional communities than in urban areas in both Australia [ 1 , 2 ] and internationally [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Young people (YP) in particular have been reluctant to seek formal mental health support, which has been attributed to stigma and negative beliefs towards mental health services and professionals [ 6 , 7 ]. Such reluctance is particularly pronounced in rural and regional communities where mental health stigma rapidly spreads through social networks and “sticks” to the individual [ 3 ]. This phenomenon has been associated with higher levels of socio-economic disadvantage [ 8 ], social conservatism [ 9 ] and social visibility in these communities resulting in reduced privacy [ 10 , 11 ], with lack of confidentiality cited as a major concern of YP when considering accessing mental health services [ 8 ]. Professional mental health care in rural and regional areas is often inconsistent and un-coordinated [ 3 , 12 ], with help-seekers being required to travel large distances [ 13 ] and experiencing lengthy service waitlist [ 14 ]. The wellbeing of these communities is also more affected by increasingly severe and prevalent natural disasters. Prolonged drought, for example, coupled with feelings of isolation has been shown to impact YP’s mental health, making them feel overwhelmed and worry about their families, friends, money and their futures [ 15 , 16 ].

While there is substantial research examining the barriers of YP’s mental health help-seeking behaviour in drought-affected rural and regional areas, less is known about what types of supports, programs and education facilitates their help-seeking [ 17 ]. In a recent systematic review on the barriers, facilitators and interventions for mental health help-seeking behaviours in adolescents, only 19 of 56 studies identified help-seeking facilitators [ 6 ]. These included previous positive experience with health services and higher levels of mental health literacy. Most research examining enablers of YP’s help-seeking is from the perspective of adults, parents and teachers (e.g., [ 14 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]). There is a lack of research examining what YP in rural and regional areas view as facilitators to seeking help when it is needed. The few studies that have examined help-seeking facilitators report that confidentiality and accessibility of mental health services [ 23 ], for the availability of more school counselling services [ 24 ], and YP desire to develop mental health self-management skills [ 15 ] to support the mental health help-seeking process.

This research program had 2 overarching aims. The first aim, which is reported in this article, was to establish a more in-depth understanding of YP’s experiences and needs regarding their mental health help-seeking, and explore mental health education, support and programs in rural and regional communities, complemented by the views of their teachers and parents. The second aim, which is reported elsewhere [ 25 ], was to evaluate the batyr@school program which was to be delivered at the participating schools within the year. The schools were selected to participate in the program by the New South Wales Department of Education as they were identified as communities which had, at the time of establishing the research, been experiencing severe drought — a recurring natural event in Australia that has been linked to adverse mental health outcomes in the affected communities [ 26 , 27 ]. The primary research question for the research reported in this article was: What are the attitudes and needs of young people, their teachers and parents regarding mental health and help-seeking in drought affected r ural and regional areas of Australia?

Study design

This study used qualitative pre- and post-intervention data from an evaluation of the batyr@school intervention [ 28 ] delivered to YP, teachers and parents in drought affected communities in Australia [ 25 ]. Semi-structured interviews (group and individual) were conducted to enable an in-depth exploration of participants’ views, experiences and needs about this sensitive topic [ 29 , 30 ]. While acknowledging its limitations [ 31 ], we used the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research checklist (COREQ checklist [ 32 ], See Supplementary File ).

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol number 2020/607). Subsequent approval was provided via the NSW State Education Research Applications Process (SERAP Number 2020373).

Setting, participants and recruitment

The participants comprised three stakeholder groups: high school students aged 14–15 years (grade 9 and 10 in Australia; n = 42; 24 females, 18 males), high school staff (primarily teachers but also administrators and Wellbeing Officers) ( n = 14; 10 females, 4 males) and two parents of high school students ( n = 2; females). Detailed participant demographics and inclusion criteria are available as a Supplementary File . Participants were recruited through 11 participating high schools who were willing to take part in the qualitative research component of the wider batyr@school evaluation. In total, 26 rural and regional school communities from drought-affected areas of New South Wales were invited to participate in focus groups or individual interviews. Focus groups were selected as the main form of data collection as this reduced the administrative burden on schools in supporting the research. Individual interviews were also offered depending on the needs of the participant (eg. time constraints, unable to attend a focus group, personal preference, accessibility issues). Of these schools, 20 participated in the mixed methods evaluation, and 11 consented to conducting the qualitative research component. Of the six schools that did not participate, 5 cited that they were under too much administrative burden to take part, and one school had experienced a recent mental health trauma so felt the timing was not appropriate.

Participants for the focus groups and interviews were recruited through a combination of passive recruitment (via distribution of info sheets through the participating schools’ communication channels to staff, parents and students) [ 33 ] and snowball sampling [ 34 ]. The intention was to minimise perceived pressure to participate whilst utilising the schools’ social networks [ 35 ]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

From June 2021 to June 2022, the chief investigator (a qualitative researcher and psychologist), supported by a postgraduate student, conducted 14 group and three individual interviews with a total of 57 participants. The group interview size ranged from 2 to 5 participants. Of the 11 student interviews, three included the active participation of a teacher. Some schools considered the presence of a teacher necessary because the student interviews were conducted during school hours. Sixteen interviews were held via Zoom, and one parent interview via telephone. The sessions lasted between 20 and 115 min (mean duration 50 min). All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, de-identified and checked for accuracy. One teacher who was unable to participate in an interview provided a one-page written feedback on the interview questions, which was included in the data set.

Two of the research team members, both with extensive experience in qualitative research, reviewed the transcripts alongside data gathering and adapted the interview guide for further interviews as initial themes evolved and the need for more data in particular topic areas emerged [ 36 ]. This reflexive iteration between data gathering and analysis also served to refine focus and understanding of the data, and to determine when theme saturation was achieved [ 37 ]. The interviews explored 4 questions: 1) participants’ views on how drought impacted their local community from a mental health perspective, 2) participants’ understanding of locally available mental health support resources, 3) YP’s help-seeking experiences including what participants would do if a(nother) YP reached out to them for mental health support, and 4) participants’ views on their communities’ attitudes and beliefs about mental ill health, stigma and help-seeking. Participants were also asked for improvement suggestions in all 4 focus areas. The final interview guide is available as a Supplementary File .

In the process of reviewing the interview transcripts and listening to the audio files, one qualitative researcher developed an extensive analytical memo. This memo initially contained rich descriptions of preliminary themes identified inductively as important relative to the research question, interspersed reflexive comments on their potential meaning and relationships to each other [ 38 ]. This expansive phase of memo-writing followed a process of structuring and abstraction of the data in which themes and sub-themes were consolidated in team discussions, using a critical realist approach [ 39 ]. As a result of this process, the analytic memo had transformed into a framework that was used to report the results. The authors (who had a diverse mix of backgrounds including: qualitative researchers, mental health professionals, a teacher, a university student and an expert by experience; two of the research team were young people themselves (i.e. aged under 25 years [ 40 ]) and one was residing in a regional community) collaboratively refined the written results in several rounds of discussion and editing. The findings were also triangulated with the initial qualitative findings of an internal batyr @school baseline evaluation report [ 25 ], which had previously been analysed, interpreted and iteratively refined by the same team excluding one qualitative researcher who led this study’s analysis. This collaborative approach to analysis encourages high levels of reflexivity based on comparisons between the multiple personal and professional perspectives of all involved.

Terminology

This study was set in a high school environment. Therefore, the term ‘student’ is used when referring to the YP who participated in this study and the term ‘young person/people (YP)’ in reference to adolescents generally. The term ‘participants’ is used when referring to all three study participant groups. Otherwise, the participant group is specified; for example, ‘Students said…’.

In the following results section YP’s perspectives, experiences and needs regarding mental health help-seeking, stigma, and education and support services in drought-affected rural and regional communities are described. This is complemented by the views of their teachers and parents. The participants’ descriptions of the barriers to each of these above areas relating to their community, family, school, peers and individuals are provided. Importantly, these barriers are followed by their suggested solutions and facilitators to help-seeking and support. The most salient participant quotes are included in the text and ancillary quotes illustrating the findings further are presented in a Supplementary File .

Barriers to mental wellbeing and coping mechanisms

Community level.

Students vividly described their communities’ existential stressors caused by drought and other recurring natural events such as floods, bushfires and mice plagues, all straining the community’s mental wellbeing (See Supplementary File , Quote 1). In some communities these stressors coincided with high levels of social disadvantage, substance abuse and domestic violence (Quote 2). Participants described how these existential and economic stressors affected YPs’ mental health (Quote 3). Long distances to the nearest healthcare services (GPs, specialists, hospitals), long wait times to obtain an appointment and a lack of local youth mental health services made it difficult for YP and their families to access professional help when they needed it (Quote 4a-4b). Both students and teachers summarised the, at times, complete absence of accessible mental health services and contrasted them to those perceived to be available in urban areas (Quote 5 and below):

In [capital city], there was a lot of resources; and when I come here, there's nothing […] There's a whole lot of issues with suicide and attempted suicide. I think there's a headspace, but I don't know where that is. I think it might be in [nearest city, two hours’ drive away]. Which is nowhere near here. We're in the middle of nowhere. It seems to me like there's a really high, a lot higher incidence of sexual assault and suicidal ideation here. I mean, it's really hard to compare these two populations, but it does seem that way to me. And there's no services. [Teacher_B4]

Mental health services that were provided as one-off visits to rural and regional schools were seen as lacking coordination and continuity, impacting their effectiveness (Quote 6). Students also emphasised the absence of suitable places outside of home and school where they could socialise and informally support each other’s mental health. Community events that provided social opportunities were limited, and youth and community centres were perceived as lacking essential infrastructure and personnel (Quote 7–8), and were not viewed as desirable for 14–15-year-olds to attend – being more suited to pre-adolescent children (Quotes 7–8).

Family level

With limited access to professional mental health and youth support services in the community, good relationships with parents were pivotal to students’ mental wellbeing (Quote 9). Some students valued talking with their parents about mental health, and felt understood and supported when a parent with lived experience of mental ill health shared their experience with them (Quote 10). However, participants described parents, especially fathers, often as time-poor, absent from home, and/or struggling with their own mental health in the face of the rural challenges (Quotes 11–13). Students (and one parent) highlighted that as parents were often lacking mental health literacy and skills, they tended to ignore or dismiss their children’s mental health concerns (Quote 14–16). This lack of knowledge was attributed to stigma, open conversations about mental health being a relatively new phenomenon, fear of appearing weak, stress, or hoping the issue would just go away (Quote 14–16). Students also reported how, at times, mental health issues entrusted to their parents leaked into the community (Quote 17). Others described how parents acted out their mental health struggles via physical aggression, which was viewed as role-modelling unhelpful behaviours to their children: