298 Disaster Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples

Are you looking for a good idea for your presentation, thesis project, dissertation, or other assignment? StudyCorgi has prepared a list of emergency management research topics and essay titles about various disaster-related issues. Below, you’ll also find free A+ essay examples. Read on to get inspired!

🌋 TOP 7 Disaster Management Topics for Presentation

🏆 best natural disaster essay topics, 💡 simple disaster management research topics, 👍 good disaster research topics & essay examples, 📌 easy disaster essay topics, 🔥 hot disaster management topics to write about, ❓ essay questions about natural disasters, 🎓 most interesting disaster research titles, ✍️ disaster essay topics for college, 📝 disaster argumentative essay topics.

- Earthquakes’ Impacts on Society

- 2004 Indian Ocean Earthquake and Tsunami

- Chernobyl Disaster and Engineering Ethics

- Forest Fires as a Global Environmental Hazard

- Disaster Management in Nursing Practice

- A Natural Disaster Preparation Plan

- Flooding and Ways to Survive in It

- Floods: Stages, Types, Effects, and Prevention Flood is the most regularly occurring and the most destructive natural disaster. The most flood-prone area in the world is Asia, but the US has its own share of floods.

- Earthquakes: Effects on People’s Health Earthquakes are one of the global environmental health issues that hugely impact people’s lives in certain geographical areas and communities.

- Decision-Making in the 1989 Hillsborough Disaster The decision-makers in the case of the Hillsborough Disaster were the event organizers, road engineers, and policemen handling the crowd.

- Strategies Applicable to the Hurricane Katrina The Mississippi Crisis Plan many focuses on public information in order to ensure more communities and populations are aware of possible disasters.

- Community Health: Disaster Recovery Plan Healthy People 2020 is a government initiative aimed at improving health for all groups. Its objectives are raising length and quality of life, achieving health equity.

- Disaster Planning and Health Information Management This paper discusses promising measures and practices to help the organization to avoid situations with loosing all health information in case of future disastrous events.

- Natural Disasters: Rebuilding and Recovery Using the case of Hurricane Sandy, this paper explores some of the best approaches that can be used to address social justice and multicultural issues related to rebuilding and recovery.

- Natural Disasters and Disaster Management in Katmandu This paper identifies the major disasters in the Kathmandu valley, suggested strategies to mitigate them, and the government’s move toward disaster management.

- The Tohoku Earthquake: Tsunami Entry The paper discusses the Tohoku earthquake. The tsunami evacuation can be described as one that was preceded by warning, preparation, and knowledge.

- Stop Disasters Game: Learning, Entertainment, or Both? It is worth mentioning that the game seems to be informative in helping the player understand how to get prepared for natural calamities.

- Earthquake Resistant Building Technology & Ethics Foreign engineers aimed to replace Japanese architecture with a more solid one with masonry houses, new railroads, iron bridges and other European technological advances.

- Nurse’s Role in Disaster Planning and Preparedness Public health officials play an important role in disaster planning and emergency preparedness. Nurses are involved in disaster planning, preparedness, response and recovery.

- Human Factors In Aviation: Tenerife Air Disaster The probability of mistake linked to the issue estimates around 30%, which is too high for aviation. For this reason, there is a need for an enhanced understanding of the problem.

- Dell Technologies Company’s Disaster Recovery Plan The goals of Dell Technologies include not only succeeding in its target market and attracting new customers but also demonstrating that its technology can be safer.

- Valero Refinery Disaster and Confined Space Entry On November 5, 2010, a disaster occurred at the Valero Delaware City, Delaware. Two workers succumbed to suffocation within a process vessel.

- Natural Disasters and Their Effects on Supply Chains This paper identifies emerging global supply chains and uses the cases of Thailand and Japan to explain the impacts of natural disasters on global supply chains.

- Hurricane Katrina: Government Ethical Dilemmas Hurricane Katrina is a prime example of government failure. That`s why the leadership and decision-making Issues are very important at every level: local, state and federal.

- Emergency Operations Plan During Earthquake Timeliness and quality of response to environmental challenges are the primary factors that can save the lives of thousands of people.

- A Report on Earthquakes Using Scientific Terms The current essay is a report on earthquakes using scientific terms from the course. Moment magnitude or moment magnitude scale refers to the relative size of an earthquake.

- Comparison of the Loma Prieta California Earthquake and Armenia An earthquake is a tremor in the earth’s crust that results to seismic waves as a result of the sudden energy realized from the earths bowels.

- Geology: Iquique Earthquake in Chile This paper describes the Iquique earthquake that took place on 1 April, 2014 in Chile and explains why living near an active faultline is better than on an active volcano.

- Consequences of Northridge Earthquake The paper discusses Northridge Earthquake. A blind thrust fault provoked an earthquake of a magnitude of 6.7, which is high for such a natural phenomenon.

- Earthquake: Definition, Stages, and Monitoring An earthquake is a term used to describe the tremors and vibrations of the Earth’s surface; they are the result of sudden natural displacements and ruptures in the Earth’s crust.

- Drought as an Extremely Dangerous Natural Disaster On our planet, especially in places with an arid climate, drought itself, like the dry winds that cause it, are not uncommon.

- India’s, Indonesia’s, Haiti’s, Japan’s Earthquakes In 2001, the major tremor hit the Indian state Gujarat. It was reported as the most significant earthquake in the region in the last several decades.

- Disaster Triage and Nursing Utilitarian Ethics Utilitarian moral principles are applicable to a wide range of extreme situations. One of the most relatable ethical issues in this context would be disaster triage.

- Disasters and Emergency Response in the Community The onset of a disaster prompts the nation, region, or community affected to depend on the emergency response team.

- Hurricane Katrina: Improvised Communication Plan This article seeks to highlight improvised communication plans adopted by the victims in the shelter at the Houston Astrodome.

- Links Between Natural Disasters, Humanitarian Assistance, and Disaster Risk Reduction: A Critical Perspective

- Global Warming: The Overlooked Man-Made Disaster Assignment

- Natural Disaster, Comparing Huadong and Spence Views

- Natural Disaster, Policy Action, and Mental Well-Being: The Case of Fukushima

- Natural Disaster Equals Economic Turmoil – Trade Deficit

- Disaster and Political Trust: The Japan Tsunami and Earthquake of 2011

- Minamata Mercury Pollution Disaster

- Natural Disaster Damages and Their Link to Coping Strategy Choices: Field Survey Findings From Post‐Earthquake Nepal

- Flood Forecasting: Disaster Risk Management

- Disaster Relief for People and Their Pets

- Man-Made Natural Disaster: Acid Rain

- What Spiritual Issues Surrounding a Disaster Can Arise for Individuals, Communities, and Health Care Providers

- Natural Disaster Management Strategy for Common People

- Flood Disaster Management With the Use of Association for Healthcare Philanthropy

- Disaster Relief and the United Nation’s Style of Leadership

- India’s 1984 Bhopal Disaster Analysis

- The National Disaster Management Authority

- Natural Disaster Insurance and the Equity-Efficiency Trade-off

- What the Puerto Rican Hurricanes Make Visible: Chronicle of a Public Health Disaster Foretold

- Disaster, Aid, and Preferences: The Long-Run Impact of the Tsunami on Giving in Sri Lanka

- Natural Disaster Early Warning Systems

- Disaster Preparedness for Travis County Texas

- Establishing Disaster Resilience Indicators for Tan-SUI River Basin in Taiwan

- Natural Disaster Death and Socio-Economic Factors in Selected Asian Countries

- Managing the Arsenic Disaster in Water Supply: Risk Measurement, Costs of Illness and Policy Choices for Bangladesh

- Large-Scale Natural Disaster Risk Scenario Analysis: A Case Study of Wenzhou City, China

- Hurricane Katrina: Natural Disaster or Human Error

- Disaster Relief and the American Red Cross

- Extreme Natural Events Mitigation: An Analysis of the National Disaster Funds in Latin America

- The Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster and Its Effects on the World

- The Review of the Challenger Disaster This essay aims to discuss the Challenger Disaster and consider the details of the mission. It examines the reasons why the mission was conducted despite the warnings of engineers.

- William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster The 1928 St. Francis dam disaster in Los Angeles, California is one of the most devastating man-made failures in the history of the United States.

- Disaster Recovery Plan At Vila Health At Vila Health, the use of inadequate protocols caused confusion, staff overload, and excessive use of resources, so an improved Disaster Recovery plan is needed.

- Teaching Experience in Disaster Management Among Teenage Students The significance of the role that a nurse plays in disaster management (DM) is often overlooked yet is crucial to the safety and security of community members.

- Mississippi’ Disaster: Hurricane Katrina Crisis Strategy The primary strength of the crisis plan adopted by the authorities in Mississippi is the commitment of the authorities respond faster than they did during Hurricane Katrina.

- Mining as a Cause of Environmental Disaster Mining does great damage to the environment and biological diversity of the planet. The negative consequences of mining indicates the gravity of the present ecological situation.

- Earthquakes: History and Studies Earthquakes are sudden movements of the earth’s surface caused by the abrupt release of energy into the earth’s crust. The earliest earthquake took place in China in 1411 BC.

- Disaster Preparedness and Recovery The paper analyzes the characteristics of public and private partners concerning disaster, their advantages and disadvantages, and the government’s role in disaster control.

- Bhopal Disaster: Analytical Evaluation The Bhopal accident occurred in India almost 40 years ago, on December 2, 1984. This disaster claimed the lives of 3800 people.

- Disaster Recovery Plan in Overcoming Disparities Health services are a social determinant and barrier that affects community health, safety, and recovery efforts.

- Ethics of the Flixborough Chemical Plant Disaster The Flixborough chemical plant disaster exposed some problematic ethical issues found in the engineering industry.

- Earthquake Mitigation Measures for Oregon Oregon could prepare for the earthquake by using earthquake-proof construction technologies and training people.

- Galveston Hurricane of 1900 The paper discusses Galveston, the 1900 hurricane. It remains the deadliest in terms of natural disasters ever witnessed in the history of America.

- The Flood in Genesis and Lessons Learnt The story of the Flood in Genesis is fascinating because it is illustrative of the new beginning and a chance to achieve a different result for humanity.

- Disaster Preparedness Experience It is essential to conduct such training for water damage, which can come from floods or even a small leak that goes undetected for some time.

- Prevention of Nuclear Disasters The paper reports on the mechanical and engineering failures that sparked a nuclear meltdown in the Three Mile power plant, its effects and the ways to improve safety.

- Destructive Force: Earthquake in Aquila, Italy A high magnitude earthquake shook Central Italy and the worst hit was the city of Aquila, the pain and sorrow were palpable but it did not take long before the people decided to move on.

- Historical Perspective and Disasters as a Process Natural disaster should be analyzed on the social level, because disasters are socially constructed and experienced in different ways by individuals or groups of individuals.

- Disaster Management and Training for Emergency A national emergency management training center’s existence ensures a higher level of cooperation, experience exchange, and knowledge accumulation.

- Nonprofit Organizations’ Disaster Management This research paper is performing an in-depth analysis of the nonprofit sector and its implications for the field of disaster management.

- Hurricane Maria and Community Response to Hazard Hurricane Maria, which took place in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Dominica on September 20, 2017, is believed to be one of the most devastating natural disasters.

- Flood Environmental Issues in the Netherlands With the current constantly rising sea levels, the Netherlands is at constant risk of floods, and those calamities were harsh incentives for the country’s development.

- Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster: Causes of the Tragedy and the Measures to Be Taken On January 28, 1986, the Challenger was launched to explode 73 seconds after its lift-off. The tragedy is commonly called “the worst disaster in the history of the space program”.

- Effect of Flooding on Cultures in Egypt and Mesopotamia The effects of Tigris and Euphrates river largely impacted on the Mesopotamian culture more so with regard to its frequent and destructive floods.

- Causes of the Haiti Earthquake This paper defines what an earthquake is, then discusses and reviews the causes of the Haiti Earthquake and the possibility of another Earthquake.

- Hurricane Katrina as One of the Worst National Disasters in the USA This paper illustrates the reasons why american levees failed to control the flooding problems during the Katrina hurricane what attributed to engineering ethics and the precaution.

- Vulnerable Population: Disaster Management’ Improvement This paper helps understand that addressing an array of needs and demands of the vulnerable population remains one of the major issues in the sphere of disaster and emergency management.

- Fukushima and Chernobyl’ Nuclear Disasters Comparison The aim of this paper is to compare and contrast Fukushima and Chernobyl nuclear disasters, access its effects and discuss some of the measures that have been undertaken.

- Tornado and Hurricane Comparison Both a tornado and a hurricane are fraught with terrible consequences, both in terms of material damage and the possible injuries. Hurricanes causes impressively lesser damage.

- The Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster The space shuttle is known to be one of the most ambitious projects of the modern age. The idea to create a spaceship seemed fantastic and even ridiculous.

- Nuclear Disasters: Fukushima and Chernobyl Both Fukushima and Chernobyl disasters were nuclear crises that occurred accidentally in Japan and Ukraine respectively.

- A Hurricane Threat: A Risk Communication Plan The paper discusses a risk communication plan for the residents of New Orleans about a hurricane threat. It addresses disaster scenarios and introduces the risk communication plan.

- Why the Hurricane Katrina Response Failed Hurricane Katrina was the most destructive hurricane in US history, hit in late August 2005. The most severe damage from Hurricane Katrina was caused to New Orleans in Louisiana.

- The US Disaster Recovery System’s Analysis The US disaster recovery system is operating below its potential, hence there is a need to review performance in past disaster incidents.

- Chornobyl Disaster: Exploring Radiation Measurement After Fukushima The event is the Chornobyl disaster. A flawed reactor design caused it (Westmore, 2020). It resulted in the discharge of radioactive particles.

- Concrete Homes Your Fortress in a Natural Disaster

- II-the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster the Year

- Hurricane Katrin Human-Made Disaster

- Hurricane Sandy: Lessons Learned From the Natural Disaster

- Thomas Drabek and Crisis and Disaster Management

- Disaster Management: The Cases of Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Rita, and Hurricane Ike

- Natural Disaster, Environmental Concerns, Well-Being and Policy Action

- Improving the American Red Cross Disaster Relief

- Union Carbide Disaster: Bhopal, India

- Managing Risk the Disaster Plan That You Will Need

- Disasters: Disaster Management Cycle and Major Disasters in India in the Year 2017

- Ready for the Storm: Education for Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation

- Fire Prevention and Basic Disaster Management

- Japan Tsunami Disaster March 2011 Present the Earthquake-Tsunami Hit Japan

- Indian Ocean Tsunami: Disaster, Generosity, and Recovery

- Gauley Bridge Disaster and Bhopal Disaster

- Natural Disaster Shocks and Macroeconomic Growth in Asia: Evidence for Typhoons and Droughts

- Disaster Recovery Toms River After Sandy

- The History About the Bhopal Disaster Construction

- The Black Death Was the Largest Disaster of European History

- Middle Tennessee Disaster Analysis

- Living With the Merapi Volcano: Risks and Disaster Microinsurance

- Natural Disaster Risk Management in the Philippines: Reducing Vulnerability

- Korea’s Neoliberal Restructuring: Miracle or Disaster

- The Indian Ocean Tsunami: Economic Impact, Disaster Management, and Lessons

- Modeling the Regional Impact of Natural Disaster and Recovery

- Knowledge Management Systems and Disaster Management in Malaysia

- Disaster Planning and Emergency Response

- Disaster Vulnerability and Evacuation Readiness: Coastal Mobile Home Residents in Florida

- Hurricane Katrin Disaster Response and Recovery System

- Earthquake’s Intensity and Magnitude Intensity measures earthquakes’ strength and indicates how much the ground shook. An earthquake’s magnitude quantifies its size.

- Lake Oroville Disaster: Analysis Water released from the lake through the spillway was halted to assess the damage, which caused the quick rise of Lake Oroville water levels.

- Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Recovery in the US PDD-39 and HSPD-5 are very similar safety directives, united by the provisions concerning terrorism as a world problem and the attitude of the United States towards it.

- An Agent-Based Model of Flood Risk and Insurance This paper provides all essential information concerning the nature of property and liability insurance along with its core principles.

- Henderson Flood Hazard and Risk Assessment A proper understanding of the disasters capable of disorienting the lives of the people of Henderson can guide different agencies to formulate interventions.

- Discussion of Managing Disasters in the USA People in the United States of America are constantly in danger of natural disasters, such as storms and tornadoes.

- FEMA Assistance to Man-Made and Natural Disasters The Federal Emergency Management Agency can provide financial assistance to individuals and families who, as a result of natural disasters, have incurred expenses.

- Hurricane Response Plan: Analysis The City of Baton Rouge Emergency Services has developed a five-step detailed response plan in the event of a major hurricane to reduce risks to civilians and city infrastructure.

- The Hurricane Katrina: Consequences Hurricane Katrina is one of the unprecedented disasters that led to deaths and the destruction of economic resources.

- MAP-IT Framework for Disaster Recovery Plan for the Vila Health Community This Vila Health Disaster Recovery Plan will address the potential threat of the Monkeypox (MPX) outbreak in the Charlotte, North Carolina, area.

- The Possibility of Agroterrorism: Disaster Management Efforts The U.S. needs to prepare for the possibility of agroterrorism. Local administrators are responsible for disaster management efforts.

- Earthquakes Preventions in USA and Japan The article clarifies the issue of earthquakes in the United States, investigate the weaknesses of the American system, and explore the benefits of the Japanese technique.

- Aspects of Hurricane Irma: Analysis The paper examines Hurricane Irma and the responses of the country, state, and Monroe County to the disaster. Irma was one of the most powerful hurricanes.

- Earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand The earthquake is considered one of the costliest natural disasters in history. Thousands of buildings, cars, and other property were damaged or destroyed completely.

- Researching of Record-Breaking Floods Floods are natural disasters, usually caused by excessive precipitation, leading to severe consequences. The most significant flood in the world occurred in 1931 in China

- Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans Hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans, on the United States Gulf Coast, on August 29, 2005, leaving a path of devastation and flooding in her wake.

- “Emergency Management”: Building Disaster-Resilient Communities “Emergency Management” exemplifies the opportunities available currently in regard to building disaster-resilient communities to strengthen emergency management in the US.

- Space Shuttle Columbia Disaster: Results After the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster, NASA identified the management failure elements that led to the disaster and substituted them with sustainable alternatives.

- Hurricane Vince: The Tropical Cyclone Hurricane Vince is a tropical cyclone that formed and developed in the eastern region of the Atlantic Ocean in 2005, near the Iberian Peninsula.

- Humanitarian Assistance After 2010 Haiti Earthquake This paper aims to discuss how the people of Haiti experienced the earthquake, as well as how humanitarian aid from various organizations helped make a difference for Haitians.

- Disasters Influenced by Technology Depending on the natural environment of a community, social and building systems could either be strong or weak and vulnerable to a disaster.

- Disaster: Typhoon in Philipines Developing countries struggle to receive equal access to the same options. States like the Philippines do not have enough resources to invest in resilience and prevention measures.

- Destructive Atlantic Hurricane Season in 2017 The deadly and destructive 2017 Atlantic Hurricane Season affected many people in society as it made people lose over 200 billion dollars.

- Earthquakes: Determination of the Risk There is a need to create awareness and knowledge about earthquake disasters and how to mitigate and respond to such disasters.

- Disaster Management and Analysis of Information The assessment and analysis of a disaster help understand the main problem, causes, and effects on human safety and security.

- Disasters and Actions of Rapid Response Services The collaborative work of rapid response services in emergencies is crucial for the rapid and effective elimination of their consequences and for saving people’s lives.

- Earthquake Threats in Bakersfield Earthquakes and dam failures are the most severe threats to Bakersfield, both of which can result in gas leaks and power disruptions.

- The Mississippi Floods of 2020, Its Impact and the Requisite Solution for the Future For numerous years, the Mississippi River has been prone to flooding incidents proved quite inconvenient for the local communities.

- Hurricane Katrina: Military and Civilian Response One of the three most dramatic catastrophes of the millennium, hurricane Katrina highlighted weak points of government and military forces.

- The Haiti Quake and Disaster Aid The experience of Haiti with earthquakes supports the opinion of researchers that there are factors that might prevent entities from assisting the populations.

- Disaster Recovery Plan for the Vila Health Community The Vila Health community has significant limitations as it has many elderly patients with complex health conditions, with shelters for the homeless running at capacity.

- Hurricane Katrina and Failures of Emergency Management Operations Hurricane Katrina came from the coast of Louisiana on August 29, 2005, immediately resulting in a Category 3 storm as winds reached the speed of over 120 miles per hour.

- Incident Command System and Disaster Response The significance of successfully deploying the Incident Command System to any type or scale of emergency response situation cannot be overestimated.

- Communities and Disaster Preparedness: Limiting the Spread of COVID-19 This paper focuses on communicating the necessary rules children must follow to limit the spread of COVID-19 as much as possible.

- Preventing Forest Fires in California with Forestry Changes From the beginning of the 21st century, California has been experiencing an increase in forest fires, destroying citizens’ lives and property.

- How Can We Prevent Natural Disasters?

- What Is the Relationship Between Disaster Risk and Climate Change?

- How Does Disaster Affect Our Lives?

- Where Do Natural Disasters Happen?

- What Natural Disasters Are Caused by Climate Change?

- How Can We Communicate Without a Phone or Internet in a Disaster?

- What Is the Difference Between Crisis Management and Disaster Recovery?

- Can Natural Disasters Be Prevented?

- How Can We Reduce Disaster Risk?

- Are Natural Disaster Situations a Formidable Obstacle to Economic Growth?

- Why Is Communication Important in Disaster Management?

- How Do Natural Disasters Help the Earth?

- What Are the Principles of Disaster Management?

- Are There Any Aspects of BP’s Ethical Culture That Could Have Contributed to the Gulf Coast Oil Spill Disaster?

- Why Is Governance Important in Disaster Management?

- How Does Weak Governance Affect Disaster Risk?

- What Are the 5 Important Elements of Disaster Preparedness?

- How Can Climate Change Affect Natural Disasters?

- What Is Alternative Communication System During Disaster?

- How to Cope With the Stress of Natural Disasters?

- Does Economic Growth Really Reduce Disaster Damages?

- Who Is Responsible for Disaster Management?

- What Is the Importance of Disaster Risk Assessment?

- How Important Is Disaster Awareness and Preparedness?

- Does Natural Disaster Only Harm Humankind?

- Preparedness Planning in Case of Flooding According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, a preparedness plan for floods is divided into multiple steps that meet a national preparedness goal.

- Earthquakes as the Natural Disaster Posing the Greatest Danger to Societies The scope of irreparable damage, human losses, and paralyzed infrastructure due to earthquakes causes high economic costs for rescuing, preventing, reconstructing, rehabilitating.

- Disaster Planning for Public Health: Darby Township Case The present paper is devoted to flood preparedness and planning in Darby Township (DT) located in Delaware County, Pennsylvania.

- Disasters Caused by Climate Change This paper focuses on several recent natural disasters caused by climate change – simultaneous fires in Russia and floods in Pakistan.

- Hurricane: How Human Actions Affect It To prevent the frequent occurrence of hurricanes, it is necessary to understand the process of their occurrence and how human actions affect it.

- “Measuring Inequality in Community Resilience to Natural Disasters” by Hong et al. This paper analyzes the scientific study “Measuring inequality in community resilience to natural disasters using large-scale mobility data” and the content of the article.

- Natural Disaster Preparedness in Texas: Nursing Response Southeast Texas is the territory largely affected by hurricanes. In addition to property damage, hurricanes pose threats to public and individual health in different ways.

- Overpopulation’s and Environmental Disasters’ Connection This essay focuses on evaluating overpopulation as one of the greatest environmental threats, the relationship between the problem of overpopulation and harm to harmony in nature.

- Nursing and Natural Disasters: An Emergency Planning Project The purpose of this paper is to describe the role of the nurse in an emergency situation (an earthquake) by listing priorities, resources, describing the nursing process.

- The Importance of Disaster Recovery The paper aims at providing a Disaster Recovery Plan for the Vila Health community and presenting evidence-based strategies to enhance the recovery effort.

- Hurricane Katrina: Hazards Management This paper explores the events of Hurricane Katrina in regard to the arguments for and against rebuilding along the shorelines.

- Noah’s Floods: Development of the Grand Canyon Rocks The paper discusses Noah’s floods. Developing a distinction between the sole causes for the development of the Grand Canyon rocks is still a daunting task.

- Disaster, PTSD, and Psychological First Aid Psychological first aid should be consistent and evidence-based, practically applicable in the field, appropriate, and culturally flexible.

- IT Disaster Recovery Plan Information technology disaster recovery management procedures remain an important element of the overall corporate strategy.

- Adopting Smart Grid to Mitigate the Blackout Disaster The author proposes the creation of a smart grid for effective blackout monitoring and mitigation the blackout disasters.

- Spiritual Considerations in the Context of a Disaster The purpose of this essay is to discuss the spiritual considerations arising after disasters and a nurse’s role in this scenario

- The Role of Nurses in Disaster Management Taking action in the event of adversities and helping out communities in recuperation is a central part of public health nurses.

- Loss Prevention and How It Was Affected by Hurricane Katrina The most damaging flood in United States’ history, is known as the 2005 Great New Orleans Flood or Katrina. It is estimated that the damages were incurred in 2005.

- Nuclear Disaster Prevention and Related Challenges The article addresses the role of transparency in monitoring nuclear arsenals as well as the varied approaches for identifying challenges.

- Chernobyl and Fukushima Disasters: Their Impact on the Ecology The fallout’s impact poses a danger to animal and plant life because of the half-life of the released isotopes. Longer exposure to radiation may lead to the burning of the skin.

- Information Technology Disaster Recovery Planning Disaster recovery planning is the procedure and policies set aside by a given organization to ensure their continuity and recovery from a natural or human-caused disaster.

- Disaster Responses: Improving the State of Affairs Despite technological improvements and increased knowledge, humanity is still struggling against disasters because they cannot either predict them or respond to them appropriately.

- Disaster Preparedness: Miami, Florida The development of a disaster preparedness plan is a priority for all states, and Miami, Florida, is no exception to the rule.

- Emergency and Disaster Preparedness in Healthcare The impromptu nature of emergency and disaster occurrence makes it almost impossible to prepare for emergencies and other challenges.

- Galveston Hurricane of 1900 and Hurricane Harvey The coast of the United States in general and Texas in particular experiences tropical storms on a regular basis. Hurricanes hit the Texas coastline, often causing property damage.

- Lazarus Island: Disaster Systems Analysis and Design This paper aims to develop a web-based emergency management system for the government of Lazarus Island. This system will be used at the response stage of disaster management.

- “Manual Dosage and Infusion Rate Calculations During Disasters” by Wilmes The article “Manual dosage and infusion rate calculations during disasters” written by Wilmes, highlights the importance of manual calculation skills in nurses.

- Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery Data loss is the center of focus of business continuity and disaster recovery (BC/DR), as this is the lifeblood of business operations today.

- Fire Disaster Plan For a Skilled Nursing Facility The purpose of this fire disaster plan is to provide guidance to the skilled nursing facility on fire emergency procedures to protect the lives and property of staff, residents.

- Southern Europe Flash Floods: Disaster Overview Southern Europe flash floods are the most recent significant event. People need to learn about the cause and effects of flooding and apply the knowledge to protect themselves.

- The Atlantic Hurricane Season Explained The Atlantic hurricane occurs from June 1 to November 30. It peaks sharply from late August to September; in most cases, the season is at the highest point around September 10.

- Community Disaster Preparedness in Nassau County, New York The objective of disaster management is to design a realistic and executable coordinated planning that minimizes duplication of functions and optimizes the overall effectiveness.

- Article Review: “The Impact of Hurricane Katrina on Trust in Government” The research applies trust concept to and measured in dwellers of several counties within Mississippi and Louisiana.

- International and South Africa’s Disaster Management When South Africa gained self-governance status in 1931, one of the issues that its government focused on was the management of major disasters.

- Disaster and People Behavior Changes Some of the behavioral changes that occur due to the presence of a disaster relying from research from sources across the world on the countries affected by the disasters.

- Organizational Behavior and Motivation in Hurricane Response

- All-Hazards Disaster Preparedness: The Role of the Nurse

- Hurricane Katrina’s Mental Health Impact on Populations

- Disaster, Crisis, Trauma: Interview with a Victim

- Effects of Earthquakes: Differences in the Magnitude of Damage Caused by Earthquakes

- How Natural Disasters Impact Systems at Various Levels?

- Disasters’ Benefits to People Who Experience Them

- Chernobyl Disaster’s Socio-Economic and Environmental Impact

- Environmental Disaster Education: Incorporation Into the University Curriculum

- Was the BP Oil Spill Disaster in the Gulf Avoidable

- The 1900 Galveston Hurricane: Disaster Management Failure

- Managing Change, the Challenger and Columbia Shuttle Disasters

- Ethical and Legal Issues During Catastrophes or Disasters

- Has the Media Changed the Response to Natural Disasters?

- Managing Emergencies and Disasters

- Energy Safety and Earthquake Hazards Program

- Recovery Efforts During 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina

- Hurricane Katrina and the USA’s South

- International Studies: Global Disasters

- Hurricane Katrina: Determining Management Approach

- Scientific Responsibility for Earthquakes in Japan

- Disaster Recovery. Automated Management System

- Media Coverage of the China 2008 Earthquake

- Vulnerability of Hazardville to Flooding Disasters

- Natural Sciences. 1996 Mount Everest Disaster

- The Climate Tragedy and Adaptation to Disasters

- Potential Disasters’ Impact on Nursing Community

- National Guidance During Hurricane Katrina

- Disaster Operations and Decision Making

- Psychological Issues After a Crisis or Disaster

- Hurricane Katrina and Public Administration Action

- Emergency Planner’s Role in Disaster Preparedness

- Disaster Recovery Plan: Business Impact Analysis

- Riverbend City’s Flood Disaster Communication

- The “New Normal” Concept After Disaster

- Disaster Management: Evacuations from Gulf Coast Hurricanes

- American and European Disaster Relief Agencies

- Flooding in Houston and New Life After It

- Deepwater Horizon Disaster and Prevention Plan

- Hurricane Hanna, Aftermath and Community Recovery

- Emergency and Disaster Management Legal Framework

- Disaster Support by Miami and Federal Emergency Management Agency

- 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina in Psychological Aspect

- Disaster Plan Activation and Healthcare Staff

- Hurricane Katrina and Emergency Planning Lessons

- Family Self-Care and Disaster Management Plan

- How Can the Negative Effects of Disasters Be Avoided?

- The Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster Factors

- Disaster Management: Terrorism and Emergency Situations

- Defence Against Coastal Flooding in Florida

- Evaluation as Part of a Disaster Management Plan

- World Trade Center Disaster and Anti-Terrorism

- Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Post-Disaster Fraud

- Structural Violence and Hurricane Matthew in Haiti

- Risk Management Model and Disaster Recovery Plan

- Kendall Regional Medical Center’s Disaster Plan

- Houston’s Revitalization After Harvey Hurricane

- Disaster Recovery Team and Disaster Recovery Strategy

- Hurricane Katrina: Facts, Impacts and Prognosis

- Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Response

- Hurricane Katrina, Its Economic and Social Impact

- Philadelphia Winter Snow Disaster and Its Impact

- Natural Disasters Effects on the Supply Chain

- Natural Disasters: The Budalangi Flood

- Homeland Security: Fast Response to Disasters and Terrorism

- Hurricane Katrina’ Meaning: Mental, Economic, and Geographical Impact

- Preparing for Terrorism and Disasters in the New Age of Health Care

- Healthcare Facilities Standards and Disaster Management

- Hurricane Katrina Emergency Management

- Planning Disaster Management in the Urban Context

- Environmental Studies: The Chernobyl Disaster

- Strategic Preparedness for Disasters

- Hurricane Katrina and the US Emergency Management

Cite this post

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, September 9). 298 Disaster Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/disaster-essay-topics/

"298 Disaster Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples." StudyCorgi , 9 Sept. 2021, studycorgi.com/ideas/disaster-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) '298 Disaster Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples'. 9 September.

1. StudyCorgi . "298 Disaster Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples." September 9, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/disaster-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "298 Disaster Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples." September 9, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/disaster-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "298 Disaster Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples." September 9, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/disaster-essay-topics/.

These essay examples and topics on Disaster were carefully selected by the StudyCorgi editorial team. They meet our highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, and fact accuracy. Please ensure you properly reference the materials if you’re using them to write your assignment.

This essay topic collection was updated on January 22, 2024 .

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Natural disaster preparedness in a multi-hazard environment: Characterizing the sociodemographic profile of those better (worse) prepared

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Engineering Sciences Department, Universidad Andres Bello, Santiago, Chile, National Research Center for Integrated Natural Disaster Management CONICYT/FONDAP/15110017, Santiago, Chile

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations National Research Center for Integrated Natural Disaster Management CONICYT/FONDAP/15110017, Santiago, Chile, Industrial and Systems Engineering Department, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations National Research Center for Integrated Natural Disaster Management CONICYT/FONDAP/15110017, Santiago, Chile, Department of Psychology, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Roles Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

- Nicolás C. Bronfman,

- Pamela C. Cisternas,

- Paula B. Repetto,

- Javiera V. Castañeda

- Published: April 24, 2019

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214249

- Reader Comments

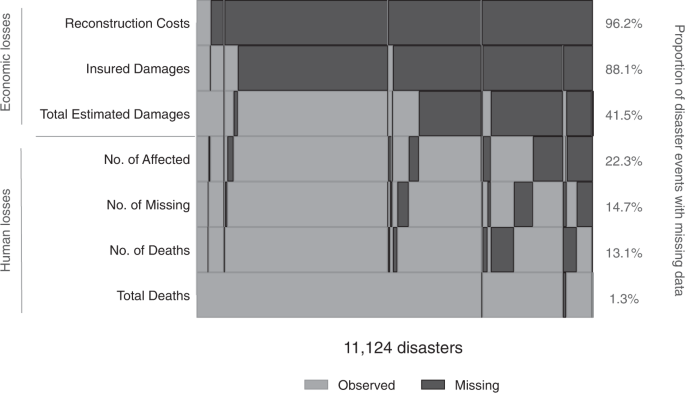

The growing multi-hazard environment to which millions of people in the world are exposed highlights the importance of making sure that populations are increasingly better prepared. The objective of this study was to report the levels of preparedness of a community exposed to two natural hazards and identify the primary sociodemographic characteristics of groups with different preparedness levels. A survey was conducted on 476 participants from two localities of the Atacama Region in the north of Chile during the spring of 2015. Their level of preparedness at home and work was assessed to face two types of natural hazards: earthquakes and floods.The findings show that participants are significantly better prepared to face earthquakes than floods, which sends a serious warning to local authorities, given that floods have caused the greatest human and material losses in the region’s recent history of natural disasters. Men claimed to be more prepared than women to face floods, something that the authors attribute to the particular characteristics of the main employment sectors for men and women in the region. The potential contribution of large companies on preparedness levels of communities in the areas in which they operate is discussed. The sociodemographic profile of individuals with the highest levels of preparedness in an environment with multiple natural hazards are people between 30 and 59 years of age, living with their partner and school-age children. The implications of the results pertaining to institutions responsible for developing disaster risk reduction plans, policies and programs in a multi-hazard environment are discussed.

Citation: Bronfman NC, Cisternas PC, Repetto PB, Castañeda JV (2019) Natural disaster preparedness in a multi-hazard environment: Characterizing the sociodemographic profile of those better (worse) prepared. PLoS ONE 14(4): e0214249. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214249

Editor: Florian Fischer, Bielefeld University, GERMANY

Received: November 15, 2018; Accepted: March 8, 2019; Published: April 24, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Bronfman et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: This research was partially funded by Chile’s National Science and Technology Commission (Conicyt) through the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Research (Fondecyt, Grant 1130864; NCB - Grant 1180996; NCB) and by the National Research Center for Integrated Natural Disaster Management CONICYT/ FONDAP/15110017; NCB, PBR, PCC. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

A World Bank report that assessed the main natural disaster hotspots in the world [ 1 ] found that approximately 3.8 million km 2 and 790 million individuals are exposed to at least two natural hazards, while 0.5 million km 2 and 105 million individuals are exposed to three or more natural hazards. An increase in the magnitude, frequency and geographic distribution of natural disasters has been recently demonstrated, particularly for those related to climate change [ 2 ]. Records show that between 1994 and 2013, floods were the most frequent event (43% of all events registered), affecting approximately 2.5 billion people [ 3 ] and caused the greatest material costs and losses. In the same period, earthquakes and tsunamis caused the highest number of fatalities, estimated at around 750,000, with tsunamis being twenty times more lethal than earthquakes [ 3 ]. These statistics demonstrate the critical multi-hazard environment to which the global population is exposed.

The combination of human and economic losses, together with reconstruction costs, makes natural disasters both a humanitarian and an economic problem [ 1 ]. Between 1994 and 2013, natural disasters produced economic losses of more than USD 2.6 trillion [ 3 ]. More recently, in 2017, USD 314 billion were spent globally on damage related to natural disasters [ 4 ]. There is currently an unresolved debate regarding whether natural disasters hinder a country’s economic growth, given that the empirical evidence is somewhat heterogeneous [ 5 ]. However, high expenditure associated with natural disasters may reduce investment in other priority areas for a country, such as education, health, transport and security [ 5 ].

There are no countries or communities that are currently immune to the impact of natural disasters. It is, however, possible to reduce the effects of these events through management strategies focused on risk reduction [ 6 ]. Citizen preparedness strategies play a key role in reducing the effects of hazards that cannot be mitigated [ 6 – 8 ], as such strategies seek to improve the ability of individuals and communities to respond in the event of a natural disaster [ 7 ].

Chile, located in the Pacific Ring of Fire, is one of the countries that is most exposed to earthquakes/tsunamis and volcanic eruptions on the planet. Among the OECD member countries, Chile is the most exposed to natural hazards, where 54% of its population and 12.9% of its total surface area are exposed to three or more hazards [ 1 ]. Between 2008 and 2018, Chile was affected by ten natural disasters (earthquakes, tsunamis, wildfires, floods and volcanic eruptions), which translated into more than four million affected individuals and close to 800 fatalities [ 9 ]. The 2010 earthquake and tsunami alone caused the death of 562 people, and gave rise to more than USD 30 billion in material losses [ 10 ]. As such, the multi-hazard environment to which the population is exposed, and the high expenditure associated with natural disasters in Chile, emphasize the importance of adopting a multi-hazard approach to progress in the design of preparedness strategies. In order to move forward in this direction, the main objective of this study is to understand the current levels of preparedness of a community exposed to multiple natural hazards and identify the primary sociodemographic characteristics of groups that show different levels of preparedness. The results of this study are expected to contribute to the development of disaster risk reduction strategies and programs in multi-hazard environments.

Preparedness in a multi-hazard environment

The complexity of territories and social structures expose communities to various hazards, both natural and man-made. Against this backdrop, the leading institutions responsible for disaster risk reduction worldwide indicate the importance of nations being able to assess, recognize and integrate the various hazards in their territories in their planning, in order to prepare the population to effectively mitigate the damages associated with these multiple hazards [ 11 ].

Although addressing a multi-hazard environment requires significant economic and political efforts, several studies have indicated that the multi-hazard approach has major benefits for the design of effective disaster risk reduction policies [ 12 , 13 ]. A multi-hazard assessment permits not only more reliable territorial planning for a country’s inhabitants but also lets stakeholders show that focusing mitigation measures on a single hazard may increase vulnerability to others [ 12 ].

The main recommendations for multi-hazard environments include strengthening risk assessment within territories, informing the population of these risks to raise awareness, and establishing multi-disciplinary and multi-sectoral efforts to develop integrated public policies [ 14 ].

Natural hazard preparedness

In recent decades, numerous studies have been focused on assessing individuals’ levels of preparedness for natural hazards, and the factors that promote the adoption of preparedness measures [ 15 – 17 ]. In the literature, there are different theoretical frameworks to conceptualize the adoption of preparedness measures to face natural hazards, where the Protective Action Decision Model [ 16 , 18 ] and the Social-Cognitive Model [ 19 , 20 ] are the most cited models. The first model recognizes that preparation is a behavior dependent on risk perception, previous experience and some demographic characteristics, among other variables. The social cognitive model focuses on the role of motivational factors on the decision to adopt preparedness actions, including awareness of the threat, anxiety, self-efficacy, and sense of community among others. Both models can help describe and understand the preparedness, however, for the purposes of the present study we incorporate elements of the Protective Action Decision Model, mainly in aspects related to the relation between sociodemographic factors and preparedness levels. This model also recognizes the role of experience that is relevant for this particular study considering that the communities that were studied had experienced both events.

One of the most common ways to study natural disaster preparedness levels is by characterizing these measures within the places where individuals spend most of their time, such as their homes (with their families) and their workplaces [ 21 – 23 ]. These areas are representative not only of the types of preparedness measures adopted by the population [ 22 ], but also the areas that people recognize as sources of common and relevant information for taking preparedness measures [ 24 ]. Preparedness actions involve developing plans, stockpiling of supplies and performing exercises and drills, all aimed to reduce the impact of the disaster [ 25 ]. These actions have been translated into recommendations, checklists and actions that organizations provide to households, communities and workplace in order to be prepared in case of a disaster. Response organizations recommend to frequently assess and evaluate whether these actions have been implemented.

Researchers have proposed several models to explain the decision to take action and implement preparedness actions, with a particular emphasis on the role that social cognitive processes [ 26 ]. Traditionally these models have emphasized the role of risk perception and have also shown that previous experience may be relevant, but with mixed results in relation with preparedness [ 18 ]. For the purposes of this study we focused on a community that had experienced different hazards in the past years, so we could examine also whether they appeared to be prepared to respond to different hazards.

Household preparedness.

Researchers have mostly focused on understanding family preparedness when characterizing the preparedness levels of the population [ 23 , 27 ]. Family preparedness has been researched and measured through different types of activities, such as survival measures, mitigation measures and planning measures [ 21 , 23 , 28 – 30 ]. Family planning measures in the face of natural hazards are those which are adopted least frequently, but whose importance is highly recognized among individuals [ 23 , 30 ]. Family preparedness is recognized as the base from which other preparation actions take place [ 27 ].

Workplace preparedness.

Despite the fact that research on natural disaster preparedness has primarily focused on family preparedness, the study of workplace preparedness is emerging as a relevant focus for research, given the role that organizations play in local economies, the lives of the people they employ and even recovery following natural disasters [ 31 , 32 ].

As in the case of family preparedness, workplace preparedness involves planning activities, such as speaking with employees about the impact and importance of preparing the company for natural hazards, having an emergency plan in place, alternative energy supplies for the company’s operation following a natural disaster, insurance for this type of events, and the presence of an emergency kit in the company, among many others [ 21 , 23 , 27 , 31 , 33 ].

One factor that is most closely related to workplace preparedness is company size [ 27 , 31 , 33 ]. This is because companies with a larger number of employees have formalized risk reduction processes, and greater resources to implement them [ 31 ].

Sociodemographic variables and preparedness level

Several of the studies that link gender to the adoption of preparedness measures conclude that women prepare more than men [ 29 , 34 ], especially when it comes to measures related to creating a family emergency plan, the safety of household members, and the use of preparedness messages [ 35 ]. Similarly, it has been reported that married people or those who live with their partner show higher levels of preparedness than those who do not [ 23 , 36 , 37 ].

The age of subjects is also a predictor for the adoption of preparedness measures. While some studies conclude that older people adopt more preparedness measures, with one of the main reasons being previous exposure to and/or experience with natural disasters [ 29 , 38 ]. In other studies researchers suggest that age is not significantly related to the adoption of preparedness measures [ 36 , 39 ].

The presence of children under 18 years of age in the household is associated to higher levels of preparedness [ 37 , 40 , 41 ]. In a study conducted on a random sample of 1,158 households in Memphis, Tennessee, Edwards [ 39 ] suggests that parents feel responsible for the safety of children, and also because children receive more information (from their school environment) about how to prepare for natural hazards, motivating parents to implement these types of measures. Similarly, Pfefferbaum & North [ 42 ] indicate that parents are more concerned about what their children will experience during a natural disaster, which may prompt a desire to anticipate its consequences and to prepare in advance to mitigate any possible negative effects.

Methodology

The research focused on the inhabitants of Copiapó and Tierra Amarilla municipalities (see Fig 1 ) in the Atacama Region in the north of Chile, since they are at risk of multiple natural hazards, particularly earthquakes and floods.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

The maps in the top left show the earthquakes that affected the Atacama Region. The map on the right shows the Copiapó and Tierra Amarilla municipalities, the flooded area of the 2015 event and the location of the households surveyed.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214249.g001

Geographic characteristics.

The Atacama Region, Chile, has a surface area of 75,176 km 2 , equivalent to 9.94% of the country’s total (see Fig 1 ). Copiapó and Tierra Amarilla municipalities account for the 37% of the Region’s surface area. The climate of Copiapó and Tierra Amarilla is semi-arid, with scarce and light rainfall during the winter months. A phenomenon known as the “Altiplanic winter” takes place here, which triggers rainfall between the summer months of December and March [ 43 ]. The “Altiplanic winter” is the name given to the phenomenon of rainfall between December and March in the north of the country, as a result of moisture originating from the Atlantic Ocean [ 43 ]. However, rainfall has occurred during winter produced by the “Altiplanic winter” phenomenon that may intensify and produce extreme hydrometeorological events, due to the presence of weather patterns known as El Niño and La Niña [ 44 ].

Population.

Copiapó and Tierra Amarilla municipalities (see Fig 1 ) are home to more than 60% of the Atacama Region’s population. The proportion of women in these municipalities is 48.6% and 42.4%, respectively [ 45 ]. Regarding age, the region’s population can be classified as follows: 19.3% are between 18 and 29 years of age, 21.0% are between 30 and 44 years of age, 19.3% are between 45 and 59 years of age, and 13.2% are above 60 years of age. A similar trend occurs for the populations of the Copiapó and Tierra Amarilla municipalities.

On December 2017, the unemployment rate in these localities reached 6.7%, slightly above the national average, which was 6.4% [ 46 ]. Mining is the sector which has the greatest influence on the country’s economic development, accounting for 10% of national GDP, generating 8.4% of national income, and representing at least half of total exports (55%) as of 2017 [ 47 ]. Currently, Chile is the largest copper producer in the world. As with other regions in the north of Chile, the main economic activity of Copiapó and Tierra Amarilla is mining (copper and other minerals), which accounts for 28% of the region’s GDP and is one of the main factors affecting employment rates. As of 2017, 15% of all workers in the region were employed in the mining sector, of which 92% were men [ 45 ].

Natural disasters in the study area.

The localities of the Atacama Region have an extensive history of natural disasters, particularly extreme hydrometeorological events causing significant floods, with the events that took place in 1997 and 2015 considered the most catastrophic. In April 1997, intense rainfall caused rivers in the Atacama Region to overflow, producing floods that affected mostly to Copiapó (see Fig 1 ). A total of 22 people died, and material losses were estimated at USD 180 million [ 9 ]. Almost two decades later, in March 2015, there was a hydrometeorological event considered the largest in its history. More than 45mm of rain fell in approximately 48 hours [ 48 ]. The effects were devastating, mainly for the towns of Copiapó, Paipote, and Tierra Amarilla. A total of 31 people died, 16 were declared missing, 30,000 were displaced, and more than 164,000 people were affected by the event [ 49 ]. The material damages were estimated at more than USD 1.5 billion.

The Atacama Region’s localities are not only vulnerable to the occurrence of major floods but also, like the rest of the country, to severe geophysical events. Chile’s location in the Pacific Ring of Fire makes it one of the countries with the highest levels of seismic and volcanic activity on the planet. The largest earthquake recorded in the study area occurred in 1877, with a magnitude of 8.8 Mw on the Richter scale [ 50 ]. The second largest earthquake in the area occurred in 1922, with a magnitude of 8.5 Mw on the Richter scale [ 51 ]. The consequences of this event were devastating: 40% of houses were reduced to ruins, a further 45% requiring demolition, and the rest in dire need of repair [ 52 ]. The most recent earthquake in the area occurred in 2014 and is considered the third most destructive to hit the region. It had a magnitude of 8.2 Mw on the Richter scale, affected 13,000 homes, and caused the death of six people. Economic losses were estimated at more than USD 100 million. Despite these events, the scientific community has demonstrated that there are still subduction zones that have not been activated for more than 150 years, and as such the probability of another event with similar characteristics occurring in the near future is very high [ 53 ].

The survey was separated into three sections, in which two types of natural hazard that affect the region were studied: earthquakes and floods. The first section contained questions about the level of preparedness for these two hazards. The second section assessed the participants’ prior experience of floods, and their evacuation experience in the latest event of 2015. Finally, the third section included questions about the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. As this survey forms part of a larger study, only the measures that were used in this study are described below.

Preparedness . The earthquake and flood preparation scale was structured into two sub-scales; one to measure household preparedness (2 items) and another to measure workplace preparedness (3 items). The items on both sub-scales were adapted from previous studies [ 21 , 23 , 28 , 29 ]. The participants were required to answer the questions associated with each sub-scale on each hazard (earthquake and flood) using a dichotomous scale (1) Yes, (0) No, as shown in Table 1 . The set of preparedness actions of the questionnaire considered the main actions suggested by International Agencies as minimum elements of preparation of individuals. The yes/no answers to these questions would be indicative of participants' perception of preparedness rather than an objective measure of the actions they actually perform.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214249.t001

Sociodemographic characteristics . The participants were asked about various sociodemographic characteristics, including their age, gender, marital status, work activity, and whether children under 18 years of age live in their household.

Procedure and participants

The understanding of the questionnaire was assessed and validated through a focus group directed by the research team. The sample was designed through simple random sampling, based on population forecasts for the Atacama Region developed by the National Statistics Institute of Chile in 2015. The first stage considered the random selection of geographic clusters (housing blocks) by block code. Then, households were selected using the Kish table and systematic sampling. Finally, people were selected on the basis of a quota system (to allow variability of gender and age). The survey took place between November and December 2015 with a statistically representative sample in the Copiapó and Tierra Amarilla municipalities. A group of interviewers contacted voluntary participants, who had to complete a paper questionnaire face to face at their homes (receiving no compensation of any form). Finally, a total of 476 people successfully completed the survey. The average age of the sample was 49 years (SD = 17.6 years, with a range of 18–94 years of age), and 66.9% of the participants were women. All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Andres Bello.

Regarding participants’ work activity, 37.2% declared that they were employed, 35.5% were homemakers, 4.6% were studying, and 11.8% were retired. Of the total number of participants who declared that they were employed (179 participants), 45% were women. While the main employment sectors for women were services (social, personal and community) and commerce, for men, the main sectors were large and medium-scale mining, transport (mainly related to mining) and construction.

Data analysis

First, a descriptive analysis of the data was carried out to assess the existence of coding errors and lost data. Then, an internal consistency analysis was performed on the full sample ( n = 476 ). The internal consistency of each sub-scale was assessed through two measures: Cronbach's alpha and corrected item-total correlation. For the first measure, values above 0.7 suggest highly consistent scales [ 54 ]. For the second measure, values above 0.3 are suggested [ 55 ]. Item-total correlation values lower than the cutoff level imply that the item is not correlated with the sub-scale, and as such it should be omitted.

To characterize the profile of participants with higher (or lower) levels of preparedness, difference in means analyses (using post-hoc Tukey tests) and a Factorial ANOVA were carried out.

Internal consistency

The internal consistency of the preparedness sub-scales was analyzed through alpha-Cronbach and corrected item-total correlation. For each participant, the preparedness sub-scales were calculated as the sum of the items that compose each one (see Table 1 ). For both hazards considered, the values of household preparedness range from 0 to 2, and for workplace preparedness range from 0 to 3. The sub-scales complied with all of the predefined requirements, and as such no items were eliminated. The α -Cronbach values for the household and workplace preparedness sub-scales for earthquakes and floods were above 0.8, and can be considered to be highly consistent (see Table 1 ).

Earthquake vs. flood preparedness

Table 1 shows the descriptive analysis of the participants’ responses to earthquake and flood preparedness questions. Significant differences are observed when comparing the participants’ degree of household preparedness and workplace preparedness to face both hazards. While the majority of participants said that they were prepared for an earthquake both at work and at home (see Table 1A ), a significantly lower proportion claimed to be prepared at work and at home for a flood (see Table 1B ).

Household preparedness

Table 2 shows the average values associated with household preparedness for earthquakes and floods, broken down by the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. It can be observed that the participants stated that they were significantly more prepared at home for an earthquake than a flood ( p < 0.001), regardless of their age, gender, marital status, and work activity. This result is an important warning sign for local and regulatory authorities, given that the recent history of natural disasters in the region reveals that floods have caused the greatest human and material losses.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214249.t002

Similarly, for both earthquakes and floods, it can be observed that the level of household preparedness by marital status and age group showed statistically significant differences ( p < 0.1). In the former case, participants who were married or living with their partner declared higher levels of household preparedness than single, separated or widowed participants. In the latter case, subjects 60 years of age and above declared the lowest levels of household preparedness among the different age groups. In general, subjects between 30 and 59 years of age declared the highest levels of household preparedness to face both earthquakes and floods.

In the case of household preparedness for floods , women declared a lower level of preparedness compared to men.

To characterize the sociodemographic profile of subjects with higher (or lower) levels of declared household preparedness , a factorial ANOVA was carried out using sociodemographic characteristics as independent variables, and household preparedness as the dependent variable. The first columns in Table 3 show the results of the model for household preparedness for earthquakes ( F = 204.292, p = 0.000), which explained 23.2% of the variance. The results suggest that the groups defined for the Work Activity variable have significantly different levels of household preparedness ( p < 0.10). Similarly, the effects of two-way interactions (AgeGroup x MaritalStatus) and (WorkActivity x MaritalStatus) also showed significantly different levels of household preparedness for earthquakes . Three-way interactions (AgeGroup x MaritalStatus x Gender) and (WorkActivity x MaritalStatus x ChildrenAge) were statistically significant for household preparedness for earthquakes .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214249.t003

Fig 2A . shows the groups associated with the two-way interaction between (AgeGroup x MaritalStatus) and (WorkActivity x MaritalStatus). Based on Table 2 and Fig 2A ., it can be concluded that the profile of subjects with the highest level of household preparedness for earthquakes are between 30 and 59 years of age, married or living with their partner, and working or studying. On the other hand, the subjects with the lowest levels of household preparedness for earthquakes are those below 30 years old or above 60 years old, retired and single, separated or widowed. With regard to the three-way interactions, no clear trends were observed that enable to infer an evident profile.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214249.g002

The columns on the right-hand side of Table 3 show the results of the model for household preparedness for floods ( F = 39.125, p = 0.000), which explained 19.6% of the variance. The only groups which show significantly different levels of household preparedness for floods were those defined by the Gender variable. Meanwhile, the three-way interactions (ChildrenAge x MaritalStatus x WorkActivity) and (ChildrenAge x AgeGroup x WorkActivity) were statistically significant for household preparedness for floods .

Based on the results shown in Table 2 and Table 3 , we can conclude that men aged between 45 and 59 years of age who live with their partner declared the highest level of household preparedness for floods . On the other hand, the subjects who declared the lowest level of preparedness are women above 60 years of age who are single, separated, divorced or widowed. About the three-way interactions, no clear trends that suggest an evident profile may be inferred.

Workplace preparedness

Table 4 shows the average values associated with workplace preparedness for earthquakes and floods, according to the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample ( n = 179 participants who declared that they were employed). The results indicate that participants are significantly better prepared at work to face an earthquake than a flood ( p < 0.001), regardless of their age, gender, and marital status.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214249.t004

Both for earthquakes and floods, the MaritalStatus variable showed statistically significant differences ( p < 0.10); that is, participants who are married or living with their partner declared higher levels of workplace preparedness .

In the case of workplace preparedness for earthquakes , participants who declared that they live with children under 18 years of age in their household showed higher levels of preparedness. Similar to the situation that occurred for household preparedness , women declared a lower level of workplace preparedness for floods compared to men.

The first columns of Table 5 show the results of the factorial ANOVA model using sociodemographic characteristics as independent variables and workplace preparedness for earthquakes as the dependent variable. The model explained 23.9% of the variance ( F = 171.612, p = 0.000). The results indicate that the effects of the two-way interactions between the AgeGroup and Children variables show significantly different levels of workplace preparedness for earthquakes .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214249.t005

Fig 2B . shows the two-way interaction between the AgeGroup and Children variables. Based on the results shown in Table 5 and Fig 2B ., it can be concluded that the profile of subjects who have the highest level of workplace preparedness for earthquakes are married or living with their partners, between 45 and 59 years of age, and have school-age children in their household. On the other hand, the participants with the lowest levels of workplace preparedness for earthquakes are those who are single (separated, divorced or widowed), above 60 years of age, and do not have school-age children living in the household.

The columns on the right-hand side of Table 5 show the results of the model using workplace preparedness for floods as the dependent variable. This model explained 17.7% of the variance ( F = 32.020, p = 0.000). The results show that the groups defined by the Gender and MaritalStatus variables have significantly different levels of workplace preparedness ( p < 0.10). Likewise, the two-way interaction effects of the Gender and MaritalStatus variables show significantly different levels of workplace preparedness for floods . Fig 2C . shows the two-way interaction between the Gender and MaritalStatus variables. Based on the results shown in Table 4 and Fig 2C ., it may be concluded that while the profile of subjects with the highest declared level of workplace preparedness for floods is men who are married or living with their partner, the profile of those with the lowest level is women who are single, separated, divorced or widowed.

The objective of this study was to assess the level of household and workplace preparedness of people living in an area exposed to multiple natural hazards and identify those groups of people with different preparedness levels.

Household and workplace preparedness

We conclude that significant differences exist in the preparedness levels declared by participants depending on the type of hazard analyzed. In fact, participants declared that they were significantly more prepared (both at home and at work) to face an earthquake than a flood, regardless of their age, gender, marital status and work activity. These results are an important warning sign for regulators and authorities, given that the recent history of natural disasters in the study area reveals that floods have caused the greatest human and material losses. Additionally, the influence of climate change is expected to produce an increase in weather phenomena, which would increase the frequency of extreme hydrometeorological events in the northern of Chile.

Among the reasons that may explain the above results is the fact that, historically, the country and the study area have placed greater emphasis on preparedness measures for earthquakes than for floods. In recent years, Chile has been affected by major earthquakes, with one of the most destructive one taking place on February 27, 2010 in the south of the country. This event caused great alarm and concern among citizens and government authorities, not only due to the destructive effects of the event, but also the shortcomings uncovered regarding the level of preparedness and coordination of government institutions responsible for disaster risk reduction. This situation received widespread media coverage, and was the subject of intense political debate which lasted for several years [ 56 , 57 ].

In addition to the above, the scientific community has indicated that the recent earthquakes that have occurred in the north of the country provide evidence that there are still subduction zones which have not been activated in almost 150 years [ 53 ]. As such, the scientific community and authorities still expect a mega-earthquake to affect the study area. This situation has led to the implementation of many communication and community preparedness plans and programs to face a potential mega-earthquake in the region in recent decades. Awareness from communities about the likelihood of an earthquake is high and motivate them to be prepared for a future event.

Our results also show high levels of declared workplace preparedness for earthquakes , which could have its roots in the presence of large mining companies in the region. In fact, the mining industry has for decades constituted the main source of development in the region, in which large mining companies have played an important role in local economies. The presence of large mining companies represents one of the greatest opportunities for the development and implementation of preparedness programs in the face of hazards, given that, as they have large numbers of employees, their emergency risk reduction and response processes are more formalized.

Although the history of earthquakes in Chile have led both public and private-sector organizations to develop increasingly effective citizen and institutional preparedness strategies, the floods that occurred in 2015 demonstrated that the Atacama Region also reveal the need to improve preparedness strategies, programs and plans to face extreme hydrometeorological events. It is therefore recommended that institutions responsible for disaster risk reduction in the region design preparedness plans and programs that recognize and integrate the different hazards present in the region, given that the prioritization of preparedness strategies for one hazard may increase vulnerability to others.

A sociodemographic profile of preparedness

Regarding the sociodemographic variables which are related to the family and workplace preparedness and in line with previous studies [ 29 , 38 ], it is concluded that the subject’s age is significantly related to their declared levels of preparedness: in general, subjects of 30 to 59 years of age declared the highest levels of preparedness. Some authors posit that this could be explained because adults in this stage of life acquire greater care responsibilities (either for others or their own assets), which may give rise to increased interest in involving themselves in preparedness measures [ 41 ]. On the other hand, the low levels of preparedness declared by young people may be explained by the fact that, in general, they have a lower perception of natural disaster risk, which translates into lower willingness to adopt preparedness measures [ 58 ].