- Open access

- Published: 18 October 2022

A systematic review of strategies used for controlling consumer moral hazard in health systems

- Zohreh Koohi Rostamkalaee 1 ,

- Mehdi Jafari 1 &

- Hasan Abolghasem Gorji 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 22 , Article number: 1260 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

7865 Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Consumer moral hazard refers to an increase in demand for health services or a decrease in preventive care due to insurance coverage. This phenomenon as one of the most evident forms of moral hazard must be reduced and prevented because of its important role in increasing health costs. This study aimed to determine and analyze the strategies used to control consumer moral hazards in health systems.

In this systematic review. Web of Sciences, PubMed, Scopus, Embase, ProQuest, Iranian databases(Magiran and SID), and Google Scholar engine were searched using search terms related to moral hazard and healthcare utilization without time limitation. Eligible English and Persian studies on consumer moral hazard in health were included, and papers outside the health and in other languages were excluded. Thematic content analysis was used for data analysis.

Content analysis of 68 studies included in the study was presented in the form of two group, six themes, and 11 categories. Two group included “changing behavior at the time of receiving health services” and “changing behavior before needing health services.” The first group included four themes: demand-side cost sharing, health savings accounts, drug price regulation, and rationing of health services. The second approach consisted of two themes Development of incentive insurance programs and community empowerment.

Strategies to control consumer moral hazards focus on changing consumer consumptive and health-related behaviors, which are designed according to the structure of health and financing systems. Since “changing consumptive behavior” strategies are the most commonly used strategies; therefore, it is necessary to strengthen strategies to control health-related behaviors and develop new strategies in future studies. In addition, in the application of existing strategies, the adaptation to the structure of the health and financing system, and the pattern of consumption of health services in society should be considered.

Peer Review reports

Maximizing the health of people and populations is one of the main goals of any health system which leads to improving personal, social, and economic well-being [ 1 ]. The efficient function of the health system depends on providing improved health services at a minimum cost [ 2 ]. Evidence shows that health spending is growing faster than economic growth [ 1 , 3 ]. On average, health spending in OECD countries was equivalent to 9% of GDP in 2018 [ 1 ]. The United States spent 18% of its GDP on health care in 2015 [ 4 ]. Moral hazard is one of the most important reasons for increasing health costs [ 5 , 6 ]. Moral hazard is the change in health behavior and consumption of health services because of insurance coverage [ 7 ]. According to the theory of moral hazard, health insurance and third-party payers, by lowering the price of care, encourage the consumer to consume more care than when they consume at the market price [ 8 ]. Insurance coverage leads to the consumption of health services above an efficient level [ 9 ].

This phenomenon is classified in different ways: ex-ante moral hazard and ex-post moral hazard, hidden information and hidden action moral hazard, provider moral hazard, and consumer moral hazard [ 10 , 11 ]. Ex-ante moral hazard occurs before illness and increases a person’s unhealthy behavior; in contrast, ex-post moral hazard occurs after the onset of illness and will increase costs by increasing demand and consuming unnecessary services. In the hidden information, the insurer cannot observe the real condition and severity of the disease to pay the cost according to the real need. In hidden action individuals’ precautionary measures are not visible, and the insured person does not take the necessary precautions to prevent the disease. Provider moral hazard occurs when a provider provides more services to increase its revenue. The provider moral hazard is also known as the provider’s induced demand. Consumer moral hazard means insured people demand more care than uninsured people [ 11 , 12 ]. Additionally, consumer moral hazard deals with the reduction in preventive healthcare behaviors resulting from insurance coverage[ 13 ].

Moral hazard is known as one of the main causes of market failure [ 14 ] that has many adverse consequences, such as the impact on demand elasticity, reduction of welfare, inefficiency in using resources, reduction in technical and allocation efficiency, reduction of benefits of risk pooling, and price increase [ 11 , 15 ]. Moral hazard, as a concern in the health insurance market, requires the application of appropriate policies and interventions to be controlled. In this regard, consumer moral hazard as the most obvious form of moral hazard [ 16 ] has been one of the topics of concern for policymakers and economic experts in recent years [ 8 ]. The aim of this study was to determine and analyze strategies used to control consumer moral hazards in health systems. The results of this study can be used for health insurance planning, health system financing, and health cost reduction.

This study was written as part of a Ph.D thesis entitled “Developing a model to control consumer moral hazard in Iran’s health system” which was designed and performed based on its proposal and was approved by the local ethics committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.IUMS.REC.1399.1103).

Research questions.

What strategies or interventions are used to control consumers’ moral hazards?

What is the approach of identifying strategies to control moral hazards?

Databases and search strategies

For this systematic review, Web of Sciences, PubMed, Scopus, Embase, ProQuest (Dissertations database), and Iranian databases Magiran (the largest Iranian database in various scientific and specialized fields) and SID (open access database to Iranian Persian and English studies) were searched without time limitation, until the seventh of February 2021. In addition, to complete the search and ensure access to all related articles, the Google Scholar search engine was also searched. On July 21, 2022, the mentioned databases were researched to Identify new publications between February 2021and July 2022. During the new search five studies were added.

Search terms were used for the titles or abstracts of the records included “moral hazard”, “unnecessary use”, “unnecessary utilization”, “non-essential use”, “non-essential utilization”, “overutilization”, “health”, “health system”, “health insurance”, “health care”, “health service”, “health services”, “healthcare”, “medical care”, and “medical service”. In Web of Sciences, Scopus, and ProQuest due to their defined search strategy, in addition to the titles and abstracts, keywords were also searched. Search in any of the databases was performed using the defined search strategy of each database. The complete search strategy is shown in Additional file 1 .

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Papers in English and Persian languages in the field of reducing and controlling consumer moral hazard in the health system, conducted in a quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods design with theoretical and empirical approaches, that were of moderate and high quality based on Dixon Wood et al. ‘s checklist [ 17 ] were included. Abstracts, letters to the editors, conference, and seminar presentations were excluded.

Methods of screening and selection criteria

All found articles were imported into Endnote software (version X9 (and duplicate articles were removed. Two researchers who were experts in the research topic and systematic review process independently screened the titles and abstracts of the articles (ZKR and MJ). In the final screening step, the full texts of the remaining articles were independently assessed by two researchers. Disagreements between the two researchers were resolved based on the opinion of a third researcher. Finally, the references of the retrieved articles were reviewed to find related articles that were not found in the first search. The screening process of retrieved papers is presented in Figure 1 . Data extraction was conducted based on author’s name, title, year of publication, country, study design, strategies used to control consumer moral hazards, outcome variables, main results and quality assessment status. The main characteristics of the included study is shown in Additional file 2 .

Literature selection and retrieval flow diagram.

Quality appraisal

In the first stage, the quality of the articles was assessed by two members of the research team who were familiar with the issue of moral hazard (ZKR and MJ), and the consensus was reached regarding the quality of the selected articles. The most important criteria for selecting high-quality articles were their relevance and role in the development of the study concept. Disagreements were resolved by a third author. The next step in the quality appraisal was based on Dixon-Woods et al. ‘s checklist [ 17 ], which included five questions regarding the clarity of the study objective(s), suitability of the study design to the objective(s), presentation of a clear report of the process of generating findings, use of sufficient data to support the interpretations, and use of appropriate analysis methods. The quality of the articles was determined based on 10 scores: 9–10 (high quality), 6–8 (moderate quality), and ≤ 5 (low quality). Articles with a score ≥ 6 were included in the study.

Data analysis

A content analysis approach was used to summarize the findings of this qualitative systematic reviews. In this way, to achieve a general understanding, each article was read and re-read, and then each text was broken into small units called code; then, the codes were classified into categories based on their similarities and differences. After interpreting the categories, based on the purpose of the study, the main themes were identified. The process of coding and classifying the codes were done by two coders) ZKR and MJ).

In the search of databases and other sources, 7488 articles were retrieved, and after removing duplicate sources and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 68 eligible articles were selected (Fig. 1 ). General description of the selected studies is shown in Table 1 . As Table 1 shows, out of 68 included papers, the majority of studies were conducted in a period from 2016 to 2021(n = 29), in a quantitative approach (n = 46). And, health service demand and utilization was the most common outcome investigated in these studies. (n = 38).

The content analysis of 68 studies included in the study are presented in the form of two group, six themes, and 11 categories.

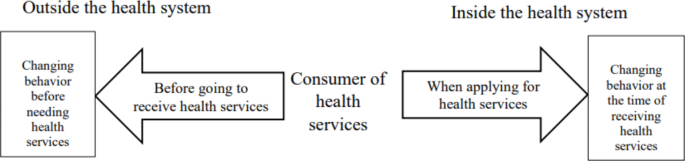

Since, based on the moral hazard theory, this phenomenon is defined as a change in consumer behavior because of insurance coverage, focusing on changing behavior and modifying it is the main goal of the controlling strategies. Therefore, the results of this study were summarized in the two groups: “Changing behavior at the time of receiving health services” (Table 2 ) and “Changing behavior before needing health services” (Table 3 ). The first group includes four themes: demand-side cost-sharing or consumer cost-sharing, health savings accounts, drug price regulation, and rationing for health services. The second group includes two themes: development of incentive insurance programs and community empowerment.

The relationship between these two groups is drawn in the form of a diagram (Fig. 2 .)

In reviewing the findings of the review studies, the results of four primary studies [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ] were repeated in one review study [ 22 ] and the results of one primary study [ 23 ] were repeated in another review study [ 24 ]. Since in the qualitative analysis, the criteria for analyzing the findings are different from the quantitative results, repeated findings were not excluded in the qualitative analysis, but in the narrative report of the findings of quantitative studies, only the findings of the primary studies were presented.

Relationship of strategies of “Changing behavior before needing health services” with strategies of “Changing behavior at the time of receiving health services”

Strategies for changing behavior at the time of receiving health services

The themes (strategies) in this group, which are used when consumers refer to the health system and receive health services by increasing awareness of services costs and other indirect financial consequences (waiting), attempt to increase their responsibility to reduce the consumption of unnecessary health services. The themes of this group consider the changing consumptive behavior of health service consumers. This group includes four themes: demand-side cost-sharing or consumer cost-sharing, health savings accounts, drug price regulation, and rationing for health services.

Demand side cost sharing

Demand side cost sharing is a financial tool [ 25 ] and a kind of out-of-pocket payment [ 26 ] that is used to decrease the demand for health services or improve the utility of useful services [ 27 ], these strategies provide incentives to reduce unnecessary demands by paying part of the service cost by consumers [ 11 ]. Deductibles (The amount of health costs that a person must pay before the insurance begins to pay), copayment (paying a fixed amount of the cost of each health service unit), coinsurance (paying a percentage of the cost of each health service unit) [ 28 ], and capping (applying a cap on out-of-pocket payments or insurance claims) are different forms of cost sharing [ 15 ] that their design methods are diverse in insurance systems [ 29 ]. Cost sharing is often used in countries with social health insurance systems [ 30 ]. In the United States, it is also used in private insurance and Medicare and Medicaid systems [ 29 ].

The results of the study showed that “demand side cost sharing“ or “consumer cost sharing” were the main strategies used for controlling consumer moral hazard as addressed by 56 studies [ 5 , 6 , 9 , 10 , 13 , 15 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 ].

In our analysis, demand-side cost-sharing was divided into two categories: uniform cost-sharing and differential cost-sharing, which were classified based on the fixed or different rates of out-of-pocket payments in the form of deductible, copayment, and coinsurance.

Uniform cost-sharing

The uniform cost-sharing strategy are also known as traditional cost sharing methods includes strategies (codes) in which the rate of patients’ out-of-pocket payments (deductible, copayment, and coinsurance) is fixed or flat to use each unit of health services for different consumers.

Differential cost-sharing

In differential cost-sharing, deductibles, copayment, and coinsurance are adjusted based on criteria such as income level; health status; consumer choice, and the type, value, price, and elasticity of the health product or service. Differential cost - sharing have been proposed in response to the high sensitivity of low-income people [ 45 , 49 , 60 , 64 , 69 ] and inefficiency [ 64 ] of fixed and low cost - sharing strategies,

Strategies related to this category include income-based cost sharing, variable deductible plans (Shift deductible, variable deductible, different size of deductible. optional deductible, voluntary deductible (VD), high-deductible health plans (HDHPs), higher insurance deductibles), tier cost sharing (higher copay or coinsurance for services with higher price of the product or service(, value-based cost sharing (lower copay or coinsurance for services with higher costs benefits or lower elasticity), differential cost sharing based on disease status and Cost sharing with discount.

The studies included in this theme investigated consequences such as the utilization of health services, health costs, health related behavior, the choice of insurance plan, and the opinion and acceptance of consumers using quantitative, qualitative, review, and theoretical approaches (model-based), the results of quantitative studies are reported in narrative form as follows: modest to high reduction in health services and medications utilization [ 9 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 33 , 38 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 49 , 51 , 55 , 56 , 64 , 69 , 71 ], reduction in health cost [ 21 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 53 , 65 , 68 ], low or no significant effect on health services utilization [ 6 , 34 , 35 , 40 , 62 , 63 , 65 ], low or no significant effect on health costs [ 5 ], increasing cost contaminate incentive (CCI) [ 57 ], significant correlation with higher preventive behavior [ 13 , 50 ] modest efficiency gain [ 18 ], increasing medication adherence [ 48 ], increasing demand for low price drug [ 61 ], optimal insurance [ 54 ].

The reported negative consequences are as follows: Decreasing the utilization of both necessary and unnecessary care [ 44 , 55 , 71 ], substitution effect from cares with cost-sharing to free care or with lower cost sharing [ 18 , 70 ], and vulnerability of low-income groups [ 49 , 60 , 68 ].

Despite the focus of differential strategies on eliminating the shortcomings of uniform strategies, some studies indicate the ineffectiveness of these strategies in response to the problem of reduced consumption of non-essential services [ 44 ], delayed treatment, and medical debt in the vulnerable group [ 68 ]. Also, the low level of unhealthy behavior in members of HDHP may be due to the individual characteristics of the people who chose the plan not the impact of the plan [ 50 ].

Health savings accounts (HSAs)

HSAs are considered as alternative tools for financing and dealing with future demographic challenges [ 72 ]. This financing theme under the title of health savings accounts [ 73 , 74 ] or medical savings accounts [ 72 , 75 , 76 ], are currently used to decrease moral hazard and cost in four countries around the world [ 72 , 75 ]. In this mechanism, owners of savings accounts should save a certain percentage of their income in these accounts for future health expenses. Funds of these accounts are used to pay for health expenses. Saving accounts increase people’s motivation to take responsibility by providing tax benefits and informed participation in health care decisions based on cost awareness and monitoring of physicians’ decisions [ 73 ].

In the United States and South Africa, they are used in combination with private insurance and is voluntarily. In Singapore and China, health saving accounts are governmental and compulsory which are implemented in combination with social health insurance and social risk-pooling system, respectively [ 72 , 75 ]. This strategy in private health insurance and combination with high deductible health plans (HDHPs) is known as consumer directed health plans or consumer-driven health plans (CDHPs) [ 59 ].

In our study, health savings accounts were divided into two categories: voluntary health savings accounts (HSAs) and compulsory health savings accounts (HSAs), which were classified according to the mandatory and optional nature of the plan and the type of financing system in each country.

Voluntary health savings accounts

In this category, health savings accounts are optional, and in combination with private insurance and high deductible health plans (HDHPs)that is known as consumer directed health plans or consumer-driven health plans (CDHPs)[ 59 ]. In the United States and South Africa, this strategy are used [ 75 ].

Compulsory health savings accounts

Compulsory health savings accounts are governmental and compulsory which are implemented in combination with social health insurance and social risk-pooling system. Medisave (Medical savings accounts) (MSAs) in combination with social health insurance, Tongdao (MSA) in combination social risk-pooling (SRP) and Bankuai: (MSA) separately to finance outpatient services, are related to this category [ 75 ].

Findings related to health savings accounts were extracted from seven studies [ 55 , 59 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 ]. In studies related to this theme, the outcome such as health services utilization, health costs, and health promotion behaviors was assess using quantitative, review, and model-based theoretical approaches. The narrative reports of these outcomes in the quantitative studies are as follows: reduction in health services utilization and cost [ 75 ], useful for future savings [ 75 ] No or less effective in controlling healthcare costs [ 74 , 76 ].

Some experts regard the usefulness of precautionary savings as positive point of these strategies [ 72 ]. In a study that assessed the effect of these strategies for prevention efforts and precautionary savings, it is stated that consumers do not take these two measures at the same time; in case of precautionary savings, preventive action is reduced, and vice versa [ 73 ]. Adverse selection, consequences of inflation, reduction of equity, and restraint of essential consumption are other negative consequences of this strategy [ 74 ].

Drug price regulation

Drug pricing is an influential component of drug access and rational use of drugs. In addition to improving access, consumption management should be considered [ 77 ]. Drug price regulation is the third theme of this group, with three categories, uniform pricing, discriminatory pricing and two part pricing, which are based on drug pricing policies and the fix or different prices for each drug unit. As the findings of this theme were extracted from only one study, the categories related to this theme included one code that could not be combined and summarized further due to dissimilarity.

Uniform pricing

Uniform pricing refers to strategies in which a product is offered at the same price for all market segment regardless of the characteristics of each segments and its ability to pay [ 78 ]. It is one of the traditional methods of pricing in the pharmaceutical industry [ 79 ]. This pricing method, despite the ease of administration, is not able to satisfy all market segments. From the perspective of high-level customers, the suggested price may be low and indicate low desirability, whereas low-income customers may consider the price high and avoid buying it [ 80 ]. Results related to this category were extracted from a study [ 81 ].

Discriminatory pricing

Discriminatory pricing offers different prices for the same drug in different markets or groups [ 78 ]. Price discrimination is caused by the inability of developing countries to provide the medicines they need. Discriminatory pricing involves a segmented market that charges different prices based on each country’s ability to pay [ 77 ]. This category includes different types; however, in this study, only third degree price discrimination was introduced as an intervention to control moral hazard [ 81 ].

Two part pricing

Two-part pricing, another name for two-part tariffs, determines the price of medicine from the combination of uniform price and lump-sum payments [ 81 ] which has recently been proposed instead of uniform pricing for drugs [ 79 ].

Results related to the “drug pricing” theme were extracted from a study [ 81 ]. In this study, three types of pricing mechanisms, including uniform pricing, two-part tariffs and third degree price discrimination were compared in order to control the consumer’s moral hazard, the results showed two-part tariffs were considered a better strategy to address consumer moral hazard [ 81 ].

Rationing of health services

Rationing of health services based on the waiting list (number) and waiting time (period) is one of the demand management strategies for non-emergency and elective health services [ 82 ]. Rationing of health services is the last theme that has one category named “rationing by waiting” which refers to strategies that control the consumer moral hazard by considering the cost of lost time. This strategy is one of the ways to reduce health costs that replaces user payments in countries without this system (national health system) to control costs and reduces unnecessary demand by imposing costs through the queue [ 30 ]. Findings related to the “ Rationing of health services ” were extracted from three studies [ 10 , 30 , 83 ]. These three studies investigated this mechanism using review and model-based theoretical approaches. The results of the theoretical analysis of these strategies regarding optimality [ 30 ] and well-being [ 83 ] outcomes were not associated with positive results.These strategies are not very popular and people tend to pay instead of waiting [ 83 ].

Strategies for changing behavior before needing health services

The themes in this group deal with the strategies that are applied outside the health system, before the need for healthcare services, and through the consciousness of health and positive financial incentives, increase healthy behavior or prevent unhealthy behavior. Changing individual behaviors to reduce high-risk behaviors and improve health-promoting behaviors is the approach of this group. This group includes two themes: development of incentive insurance programs and community empowerment.

Development of incentive insurance programs

The themes of this group focus on the measures of insurance companies and purchasers. This theme refers to strategies aimed at reducing the risk of disease and the need for health services or unhealthy behaviors and consists of two categories: extending preventive care insurance and developing bonus-oriented insurance. Findings related to this theme were extracted from11 studies [ 10 , 15 , 25 , 37 , 43 , 46 , 58 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 ].

Extending preventive care insurance

Expanding preventive care insurance refers to strategies that, by developing various types of preventive insurance, sensitize consumers to their health and reduce the need for more health services in the future by preventing the deterioration of their health status. Additionally, these strategies prevent the demand for specialized and expensive services by providing medium insurance plans [ 37 , 84 ]. This category includes the following strategies (code): proposing insurance coverage for preventive care [ 37 ], separating insurance coverage for prevention and treatment [ 37 ], to encourage insureds to use more secondary preventive care [ 84 ] and improving perception of health status through secondary preventive care [ 84 ].

Developing bonus-oriented insurance

These strategies reduce unnecessary consumption by providing incentives to avoid inefficient service. In these strategies, insurance attempts to control consumers’ moral hazard by applying positive financial incentives in the form of premium discounts [ 10 ], or more coverage [ 86 ] in the following year’s contract, in the case of less service consumption or applying preventive effort Bonuses for non-consumption or limited consumption are often used in risk adjustment schemes [ 58 ].

Health service utilization, health costs, risk-reducing behaviors, and choice of expensive health services were among the variables investigated in studies of this them in quantitative, qualitative, and theoretical approaches. The results of these studies can be summarized as follows: more feasibility to incentivize consumers to purchase more secondary preventive care [ 84 ] higher reduction in moral hazard in the copayment with a premium reduction frame than copayment reduction frame [ 46 ] moral hazard reduction in voluntary deductible is expected to be larger in a system with risk-rated premiums than in a system with community-rated premiums [ 85 ].

Community empowerment

Community empowerment is the second and last theme in this group with one category called Community education.The theme of ”community empowerment”, mentioned by only one study [ 33 ].

Community education

This category refers to the development of health-promoting behaviors through community education and increasing people’s awareness of the function of insurance and the consequences of the unnecessary use of health services by using the capacity of civil society [ 33 ]. Despite the fact that only one study had dealt with this issue marginally, due to the importance of the subject, the research team decided to set this code as an independent theme.

The sources from which each code is extracted are provided in Additional file 3 .

Risk of bias consideration

The risk of bias assessment in this study consisted of the following: To reduce publication bias, unpublished papers were searched in the Dissertations database of ProQuest for grey literature, but no related papers were found. In this regard, there is a possibility of language bias due to the limitation of non-English articles in publishing or indexing the results and the focus of this study on Persian and English articles, which is mentioned as a limitation in the limitations section.

The aim of this study was to determine and analyze strategies used to control consumer moral hazards in health systems. A wide range of goals, approaches, and various research designs have been investigated and reported.

Controlling strategies for consumer moral hazard are known as demand-side strategies whose goal are to motivate consumers to reduce unnecessary demand or consumption. In this study, the strategies to control the consumer moral hazard were divided into two groups.The first group aims to control consumer consumptive behavior when receiving health services. The second group focuses on reducing the need for health services by controlling health-related behaviors before needing health services. This classification of controlling strategies was taken from the approach of dividing moral hazards into ex-post and ex-ante moral hazard. Ex-post moral hazard means an increase in demand for health services due to price reduction, which indicates consumer price sensitivity [ 85 ]. Ex-ante moral hazard refers to a reduction in preventive behaviors and an increase in risky behaviors due to insurance coverage [ 88 , 89 ].

The results of this study show a greater frequency of studies related to the strategies of the first group and control of consumptive behavior, In contrast, strategies used for changing health-related behavior are limited which indicates that researchers pay more attention to ex-post moral hazard. Ex-post moral hazard has been widely studied, but evidence of ex-ante moral hazard is very limited [ 88 , 90 ]. The reason for less attention paid to the ex-ante moral hazard modeled by Ehrlich and Becker in 1972 may be criticized as follows: cost is not the only consequence of illness that, if paid by someone else, makes people indifferent to their healthcare [ 90 , 91 ].

Another noteworthy point of this study’s findings is the financial nature of most strategies, including demand-side cost sharing as one of the most effective methods, health savings accounts, and drug pricing. Imposing a cost through the waiting list can also be considered a financial tool. Access restrictions caused by the negative financial incentives is one of the adverse effects of these strategies. A recent study on cost sharing showed a significant relationship between cost sharing and adult mortality in poor countries. The authors believe that this issue should be considered when analyzing the social welfare consequences of cost-sharing [ 92 ]. Also, during the analysis, Michaela et al. stated that medical savings accounts cause inequality and provide little financial protection [ 93 ].

Although bonus insurance is a positive incentive financial tool because the individual receives a reward in the form of a premium discount or more coverage in exchange for reduced or non-consumption, the results of a qualitative study in insured individuals proved these strategies to be less optimistic and justified compared to demand-side cost sharing strategies [ 25 ]. In addition, the community empowerment strategy, despite being a non-financial tool, needs further investigation in future studies due to the limitations of effective studies.

The outcomes analyzed in the included studies are other points of debate in this review. The majority of the outcomes analyzed included demand and utilization of health services [ 5 , 15 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 30 , 33 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 55 , 56 , 58 , 60 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 75 , 84 , 86 ] and health services costs and expenditures, optimality and efficiency of strategies [ 5 , 15 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 53 , 54 , 57 , 59 , 68 , 70 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 83 , 85 , 87 , 94 ]. Limited studies have addressed other important aspects such as access to low-income people [ 49 , 60 , 68 ], reduction in the consumption of both essential (such as preventive and diagnostic services) and non-essential services [ 24 , 44 , 58 ], and people’s attitudes and acceptance [ 25 , 34 , 52 , 67 ].

The impact of strategies on outcomes such as the utilization of health services and health costs has been different, which seems normal due to the different implementation and management methods and whether the programs are mandatory or optional. However, in this context, the point to consider is to pay attention to the negative consequences, including the higher sensitivity of low-income groups and the shifting financial burden to insureds and an increase in total costs of health costs due to the substitution effect especially in cost-sharing methods. Thesee consequences challenge the achievement of equity in the access and efficiency of the health system. Since moral hazard is one of the factors of the inefficiency of the health system [ 95 ] therefore, in its control, improving efficiency should be the most important goal.

In this regard, the results of this research showed that controlling strategies need further investigation in future study. Due to the focus of most studies on the controlling strategies of consumptive behavior at the point of receiving the service, therefore, the suggestions are as follows. Reviewing existing strategies, especially strategies with negative financial incentives to minimize adverse consequences, paying more attention to current strategies from the perspective of preventing the need for health services and the introduction of new strategies with preferably non-financial approaches that do not limit access. Obviously, in the design of new interventions and revision of existing interventions, important consequences such as access, financial protection, equality, and quality of services provided along with service utilization and service costs should be taken into consideration.

On the other hand, considering that each of these strategies is used in different health systems with different financing mechanisms, so managers in each health system need to adjust strategy to the characteristics of their health system. In addition, considering the nature of behavioral change of strategies, knowing the characteristics of consumers, the pattern and culture of health service consumption and their health-related behaviors is the first step to choosing the most appropriate strategy and adapting it to each Society’s conditions.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The first, is the restriction of studies in Persian and English languages. No clear boundary between the consumer and provider moral hazard in some articles is another limitation. The researchers separated these two issues by studying the full text of the articles, focusing on the type and setting of service delivery and the role of physicians in providing services. The last limitation was the methodological diversity and heterogeneity of the quantitative studies, which did not allow for quantitative analysis and reporting the effectiveness of the strategies.

Data availability

All data are within the manuscript and additional files.

Abbreviations

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Gross Domestic Product.

Value Based Insurance Design.

High Deductible Health Plans.

Consumer-Directed Health Plans or Consumer-Driven Health Plans.

Medical Savings Accounts.

Health Savings Accounts.

Health Reimbursement Accounts.

social risk-pooling.

social insurance pool.

OECD. Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1787/4dd50c09-en .

Book Google Scholar

Lam HY, Zarsuelo MAM, Rey KLR, Silva MEC, Mendoza MAF, Padilla CD. Policy analysis on identifying copayment services for the shift in financing scheme of health care services. Acta Med Philippina. 2021;54(6):701–9.

Google Scholar

Global spending on. health: a world in transition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. (WHO/HIS/HGF/HFWorkingPaper/19.4). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Guo A, Zhang J. What to expect when you are expecting: Are health care consumers forward-looking? J Health Econ. 2019;67:102216.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Schubert S. Reducing public health insurance expenditure: a numerical analysis for Germany. Appl Econ. 2014;46(19):2228–41.

Article Google Scholar

Schreyögg J, Grabka MM. Copayments for ambulatory care in Germany: a natural experiment using a difference-in-difference approach. Eur J Health Econ. 2010;11(3):331–41.

Zweifel P, Manning WG. Moral hazard and consumer incentives in health care. Handbook of health economics. 1: Elsevier; 2000. pp.409–59.

Doran E, Robertson J. Australia’s pharmaceutical cost sharing policy: reducing waste or affordability? Aust Health Rev. 2009;33(2):231–40.

Trottmann M, Zweifel P, Beck K. Supply-side and demand-side cost sharing in deregulated social health insurance: which is more effective? J Health Econ. 2012;31(1):231–42.

Barati M, Azami F, Nagdi B, Foladi M, Hajimaghsoudi M, Asadi SA. Moral Hazards in Providing Health Services: A Review of Studies. Evid Based Health Policy Manage Econ. 2018;2(1):61–9.

Bazyar M, Soofi M, Rashidian A. Ways to control moral hazard in health system: demand-side and supply-side interventions. Tolooebehdasht. 2012;11(1):110–22.

Soofi M, Bazyar M, Rashidian A. Types of moral hazards and its effects on insurance marketing and health system. Hospital 2012;11(3):73–80.

Courbage C, Nicolas CJJoR. On the Association between Insurance Deductibles and Prevention Behaviour: Evidence from the Swiss Health System. J Risk Financial Manag. 2021;14(4):1–15.

Wong IO, Lindner MJ, Cowling BJ, Lau EH, Lo SV, Leung GM. Measuring moral hazard and adverse selection by propensity scoring in the mixed health care economy of Hong Kong. Health Policy. 2010;95(1):24–35.

Mirian I, Kabir MJ, Barati O, Keshavarz K, Bastani P. Deductibles in Health Insurance, Beneficial or Detrimental: A Review Article. Iran J public health. 2020;49(5):851–9.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Taghizadeh SM, Goudarzi R, Amiresmaili MR, Malekpoor Z. The Effect of Moral Hazards in the Health Insurance Industry in Iran in 2008–2010. Health and Development Journal. 2018;6(3):216–27.

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1):1–13.

Cockx B, Brasseur C. The demand for physician services: Evidence from a natural experiment. J Health Econ. 2003;22(6):881–913.

Kim J, Ko S, Yang B. The effects of patient cost sharing on ambulatory utilization in South Korea. Health Policy. 2005;72(3):293–300.

Winkelmann R. Co-payments for prescription drugs and the demand for doctor visits - Evidence from a natural experiment. Health Econ. 2004;13(11):1081–9.

Fiorio CV, Siciliani L. Co-payments and the demand for pharmaceuticals: Evidence from Italy. Econ Model. 2010;27(4):835–41.

Kiil A, Houlberg K. How does copayment for health care services affect demand, health and redistribution? A systematic review of the empirical evidence from 1990 to 2011. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(8):813–28.

Reddy SR, Ross-Degnan D, Zaslavsky AM, Soumerai SB, Wharam JF. Impact of a high-deductible health plan on outpatient visits and associated diagnostic tests. Med Care. 2014;52(1):86.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Agarwal R, Mazurenko O, Menachemi N. High-deductible health plans reduce health care cost and utilization, including use of needed preventive services. Health Aff. 2017;36(10):1762–8.

Ullrich CG. Managing the behavior of the medically insured in Germany: the acceptance of cost-sharing and risk premiums by members of the statutory health insurance. J health social policy. 2002;15(1):31–43.

Adrion ER, Ryan AM, Seltzer AC, Chen LM, Ayanian JZ, Nallamothu BK. Out-of-pocket spending for hospitalizations among nonelderly adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1325–32.

Hossein Z, Gerard A. Trends in cost sharing among selected high income countries—2000–2010. Health Policy. 2013;112(1–2):35–44.

Barua B, Moir M. Understanding Universal Health Care Reform Options: Cost-Sharing for Patients. 2022.

Qingyue M, Liying J, Beibei Y. Cost-sharing mechanisms in health insurance schemes: A systematic review. The Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO. 2011:pp.1–76.

Felder S. To wait or to pay for medical treatment? Restraining ex-post moral hazard in health insurance. J Health Econ. 2008;27(6):1418–22.

Chernew ME, Encinosa WE, Hirth RA. Optimal health insurance: the case of observable, severe illness. J Health Econ. 2000;19(5):585–609.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bardey D, Lesur R. Optimal health insurance contract: Is a deductible useful? Econ Lett. 2005;87(3):313–7.

Law CK, Yip PS. Acute care service utilisation and the possible impacts of a user-fee policy in Hong Kong. Hong Kong medical journal = Xianggang yi xue za zhi. 2002;8(5):348–53.

Reichmann G, Sommersguter-Reichmann M. Co-payments in the Austrian social health insurance system - Analysing patient behaviour and patients’ views on the effects of co-payments. Health Policy. 2004;67(1):75–91.

Schellhorn M. The effect of variable health insurance deductibles on the demand for physician visits. Health Econ. 2001;10(5):441–56.

Pauly MV, Blavin FE. Moral hazard in insurance, value-based cost sharing, and the benefits of blissful ignorance. J Health Econ. 2008;27(6):1407–17.

Ellis RP, Manning WG. Optimal health insurance for prevention and treatment. J Health Econ. 2007;26(6):1128–50.

Gerfin M, Schellhorn M. Nonparametric bounds on the effect of deductibles in health care insurance on doctor visits - Swiss evidence. Health Econ. 2006;15(9):1011–20.

Kan M, Suzuki W. Effects of cost sharing on the demand for physician services in Japan: Evidence from a natural experiment. Jpn World Econ. 2010;22(1):1–12.

Mortensen K. Copayments did not reduce Medicaid enrollees’ nonemergency use of emergency departments. Health Aff. 2010;29(9):1643–50.

Pütz C, Hagist C. Optional deductibles in social health insurance systems: findings from Germany. Eur J health economics: HEPAC : health Econ Prev care. 2006;7(4):225–30.

van Kleef RC, van de Ven W, van Vliet R. Shifted deductibles for high risks: More effective in reducing moral hazard than traditional deductibles. J Health Econ. 2009;28(1):198–209.

Bakx P, Chernichovsky D, Paolucci F, Schokkaert E, Trottmann M, Wasem J, et al. Demand-side strategies to deal with moral hazard in public insurance for long-term care. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;20(3):170–6.

Buntin MB, Haviland AM, McDevitt R, Sood N. Healthcare Spending and Preventive Care in High-Deductible and Consumer-Directed Health Plans. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(3):222–30.

Choi Y, Jae-Hyun K, Yoo K-B, Cho KH, Jae-Woo C, Lee TH, et al. The effect of cost-sharing in private health insurance on the utilization of health care services between private insurance purchasers and non-purchasers: a study of the Korean health panel survey (2008–2012). BMC health services research. 2015;15.

Drevs F, Tscheulin DK. The effect of framing on the choice of co-payment policies, reducing moral hazard and post-choice-evaluation. J Bus Econ. 2013;83(3):213–33.

Ebrahimnia M, Khezri J, Teymourzadeh E, Meskarpour AM, Farzaneh A. Impact of deductibles on insured moral hazard in the armed forces health services: A case study in Tehran. J Mil Med. 2014;16(2):93–8.

Frank MB, Fendrick AM, He Y, Zbrozek A, Holtz N, Leung S, et al. The effect of a large regional health plan’s value-based insurance design program on statin use. Med Care. 2012;50(11):934–9.

Huber CA, Ruesch P, Mielck A, Bocken J, Rosemann T, Meyer PC. Effects of cost sharing on seeking outpatient care: a propensity-matched study in Germany and Switzerland. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(4):781–7.

Kullgren JT, Volpp KG, Polsky D. Are the healthy behaviors of US high-deductible health plan enrollees driven by people who chose these plans? Smoking as a case study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56154.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Petrou P. An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis to Assess Impact of Introduction of Co-Payment on Emergency Room Visits in Cyprus. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2015;13(5):515–23.

Sinnott SJ, Guinane M, Whelton H, Byrne S. Is 50 cent the price of the optimal copayment? - a qualitative study of patient opinions and attitudes in response to a 50 cent charge on prescription drugs in a publicly funded health system in Ireland. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:16.

van Winssen KP, van Kleef RC, van de Ven WP. How profitable is a voluntary deductible in health insurance for the consumer? Health policy (Amsterdam. Netherlands). 2015;119(5):688–95.

Koc C. Disease-Specific Moral Hazard and Optimal Health Insurance Design for Physician Services. J Risk Insur. 2011;78(2):413–46.

Abdus S. The role of plan choice in health care utilization of high-deductible plan enrollees. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(1):119–27.

Alessie RJM, Angelini V, Mierau JO, Viluma L. Moral hazard and selection for voluntary deductibles. Health Econ. 2020;29(10):1251–69.

Cattel D, van Kleef RC, van Vliet R. A method to simulate incentives for cost containment under various cost sharing designs: an application to a first-euro deductible and a doughnut hole. Eur J health economics: HEPAC : health Econ Prev care. 2017;18(8):987–1000.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fels M. Incentivizing efficient utilization without reducing access: The case against cost-sharing in insurance. Health Econ. 2020;29(7):827–40.

Ferguson W, White BS, McNair J, Miller C, Wang B, Coustasse A. Potential savings from consumer-driven health plans. Int J Healthc Manage. 2020.

Hafner P, Mahlich JC. Determinants of physician’s office visits and potential effects of co-payments: evidence from Austria. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2016;31(3):e192–203.

Herr A, Suppliet M. Tiered co-payments, pricing, and demand in reference price markets for pharmaceuticals. J Health Econ. 2017;56:19–29.

Jakobsson N, Svensson M. Copayments and physicians visits: A panel data study of Swedish regions 2003–2012. Health policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2016;120(9):1095–9.

Jakobsson N, Svensson M. The effect of copayments on primary care utilization: results from a quasi-experiment. Appl Econ. 2016;48(39):3752–62.

Landsem MM, Magnussen J. The effect of copayments on the utilization of the GP service in Norway. Soc Sci Med. 2018;205:99–106.

Law MR, Cheng L, Worthington H, Mamdani M, McGrail KM, Chan FK, et al. Impact of income-based deductibles on drug use and health care utilization among older adults. CMAJ: Can Med Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. 2017;189(19):E690-E6.

Lin H, Sacks DW. Intertemporal substitution in health care demand: Evidence from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. J Public Econ. 2019;175:29–43.

O’Brien GL, Sinnott SJ, Walshe BOF, Mulcahy V, Byrne M. S. Out of pocket or out of control: A qualitative analysis of healthcare professional stakeholder involvement in pharmaceutical policy change in Ireland. Health Policy. 2020;124(4):411–8.

Rabin DL, Jetty A, Petterson S, Froehlich A. Under the ACA Higher Deductibles and Medical Debt Cause Those Most Vulnerable to Defer Needed Care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(1):424–40.

Sabik LM, Gandhi SO. Copayments and emergency department use among adult Medicaid enrollees. Health Econ. 2016;25(5):529–42.

Yoo KB, Ahn HU, Park EC, Kim TH, Kim SJ, Kwon JA, et al. Impact of co-payment for outpatient utilization among Medical Aid beneficiaries in Korea: A 5-year time series study. Health policy). 2016;120(8):960–6.

Serna N. Cost sharing and the demand for health services in a regulated market. Health Econ. 2021;30(6):1259–75.

Schreyögg J. Demographic development and moral hazard: Health insurance with medical savings accounts. Geneva Pap on Risk Insur Issues Pract. 2004;29(4):689–704.

Steinorth P. Impact of health savings accounts on precautionary savings, demand for health insurance and prevention effort. J Health Econ. 2011;30(2):458–65.

Chen T. Can Health Savings Accounts Reduce Health Spending? Evidence from China. Front Econ China. 2021;16(1):105–23.

Zhang H, Yuen PP. Medical Savings Account balance and outpatient utilization: Evidence from Guangzhou, China. Soc Sci Med. 2016;151:1–10.

Fan MY, Lei Z, Liu G. Discounting of medical savings accounts. Am J Health Econ. 2016;2(2):161–83.

Bastani PLF, Rezapoor A. Pharmaceutiacl pricing in health care. 1th ed.: Tehran. Ebadifar; 2015. [in persian].

Bergemann D, Castro F, Weintraub GJG, Behavior E. Third-degree price discrimination versus uniform pricing. Games Econ Behav. 2022;131:275–91.

Brekke KR, Dalen DM, Straume ORJJoHE. Paying for pharmaceuticals: uniform pricing versus two-part tariffs. J Health Economic. 2022;83:102613.

Roy E. Which pricing strategy is the best fit for your international marketing plan?. trade ready. 2015 [Cited 1 september 2022]. Available from: https://www.tradeready.ca/2015/fittskills-refresher/pricing-strategy-best-fit-international-marketing-plan .

Felder S. Drug price regulation under consumer moral hazard. Two-part tariffs, uniform price or third-degree price discrimination? Eur J health economics: HEPAC : health Econ Prev care. 2004;5(4):324–9.

Lee M, Martin-Carroll M, von Mollendorff W, Condon C, Kavanagh M, Thomas SJHP. Common patterns in the public reporting of waiting time and waiting list information: Findings from a sample of OECD jurisdictions. Health Policy. 2021;125(8):1002–12.

Gravelle H, Siciliani L. Optimal quality, waits and charges in health insurance. J Health Econ. 2008;27(3):663–74.

Mehta N, Ni J, Srinivasan K, Sun BH. A Dynamic Model of Health Insurance Choices and Healthcare Consumption Decisions. Mark Sci. 2017;36(3):338–60.

Antonini M, van Kleef RC, Henriquez J, Paolucci F. Can risk rating increase the ability of voluntary deductibles to reduce moral hazard? The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance - Issues and Practice. 2021.

Benjiang M, Zhang Y, Qin Y, Bashir MFJESwA. Optimal insurance contract design with “No-claim Bonus and Coverage Upper Bound”. under moral hazard. 2021;178:115050.

Wu Y, Bardey D, Chen Y, Li SJHE. Health care insurance policies When the provider and patient may collude. Health Econ. 2021;30(3):525–43.

Corso D. Drawbacks and aftermath of the Affordable Care Act: ex-ante moral hazard and inequalities in health care access. J Public Health Res. 2021;10(4):2135.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Anggraini N, Nurrohmah S, Sari S, editors. Premium calculation on health insurance implementing deductible. Journal of Physics Conference Series; 2021.

Einav L, Finkelstein A. Moral Hazard in Health Insurance: What We Know and How We Know It. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2018;16(4):957–82.

Grignon M, Hurley J, Feeny D, Guindon E, Hackett CJŒH, Methodology. Philosophy. Moral hazard in health insurance. Œconomia History, Methodology, Philosophy. 2018(8 – 3):367–405.

Buitrago G, Miller G, Vera-Hernández, MJm. Cost-Sharing in Medical Care Can Increase Adult Mortality Risk in Lower-Income Countries. Adult Mortality Risk in Lower-Income Countries. 2021.

Michaeli DT, Boch T, Michaeli TJE, Equity PF Medical Savings Accounts: Implications on Healthcare Expenditure, Efficiency, Equity, and Financial Protection. Efficiency, Equity, and Financial Protection. 2022.

Martinon P, Picard P, Raj A. On the design of optimal health insurance contracts under ex post moral hazard. GENEVA Risk Insur Rev. 2018;43(2):137–85.

Thönnes S. Ex-post moral hazard in the health insurance market: empirical evidence from German data. Eur J health economics: HEPAC : health Econ Prev care. 2019;20(9):1317–33.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was part of a PhD thesis in health services management supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences; Grant No. IUMS/SHMIS-1399-3-37-19512, the authors would like to thank all the staff involved in the School of Health Management and Information Sciences and research department of Iran University of medical sciences.

This study was funded and supported by Iran university of medical sciences (IUMS); Grant No. IUMS/SHMIS-1399-3-37-19512. The funding body had no role in the study design, analysis, and interpretation or in the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Services Management, School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Zohreh Koohi Rostamkalaee & Mehdi Jafari

Health Management Research Institute, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Hasan Abolghasem Gorji

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ZKR and MJ contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study, Interpretation and analysis of data. ZKR wrote the manuscript. HAG overviewed the study designs and drafted tables of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mehdi Jafari .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate‘.

Consent to participate is not applicable for this systematic review study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Research department of Iran University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.IUMS.REC.1399.1103).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, supplementary material 3, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Koohi Rostamkalaee, Z., Jafari, M. & Gorji, H.A. A systematic review of strategies used for controlling consumer moral hazard in health systems. BMC Health Serv Res 22 , 1260 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08613-y

Download citation

Received : 10 September 2021

Accepted : 28 September 2022

Published : 18 October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08613-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Consumer Moral hazard

- Health system

- Systematic review

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Moral Hazard in Healthcare Insurance

Concept of moral hazard, implication on public health, justification for the detrimental effects of moral hazard.

Health care insurance is an important facet in one’s life because it increases one’s access to health care. However, individuals tend to take advantage of this fact by seeking services even if it is not necessary, all because it is being catered for by an insurance company: Moral Hazard . This behavior results in increased healthcare costs and strained healthcare services. In order to ensure a balance between the costs and services individuals receive, insurance companies have resorted to imposing copayments and deductibles. This paper gives insight into Moral Hazard and its implication on public health.

Moral hazard in health insurance refers to the additional medical care that an individual gets on the basis of higher insurance coverage. Usually, this prevails among individuals with a health insurance cover only; otherwise, these individuals would not pursue this additional care if they did not have an insurance cover. For example, just because one is insured, he or she does not mind spending more or undergoing unnecessary procedures, which he or she would not have undergone without the cover.

In his explanation, Thoma (2013) indicates that moral hazard on its own, without limitations proposed above by the various health economists, would be detrimental to public health because it would promote irresponsibility and unnecessary costs that would overwhelm the insurance companies as well as the healthcare providers. On the contrary, scholars like Nyman (2007) have remained adamant that the current high incidences and prevalence rates of various health conditions and associated high rates of mortality are attributed to the misconception of the term moral hazard . Hence, the concern for increased health costs warrants better and complete models that will aid in accurate estimates of healthcare utilization. Whereas the rationale behind moral hazard is to increase access to healthcare, the general implication of this concept without some form of limitation is detrimental to public health.

Initially, Nyman (2004) presented a two-sided debate on the impact of moral hazard on public health. He presented the typical argument by health economists using the conventional theory that this additional care is not economically valuable because it is worth less in comparison to its costs of production. Whereas this may be true in reference to utilization of healthcare services on the basis of insurance cover, Geyman (2007) advocates for a consumer-driven healthcare characterized by more co-payments and deductibles while imposing some restrictions. A survey by Einav, Finkelstein, Ryan, Schrimpf, and Cullen (2013) using employee-level data indicates that moral hazard has implications on public health due to increased healthcare costs. Einav et al. (2013) seconds Geyman (2007) on the use of high-deductible plans to reduce spending in healthcare. Aron-Dine, Einav, Finkelstein, and Cullen (2015) indicate that moral hazard has great implications on the nonlinear nature of health insurance as individuals respond to the dynamic incentives contained herein. The development of dynamic incentives in healthcare using the concept of cost sharing has led to remarkable declines in healthcare costs because low coinsurance rates are linked to lower expenditure, and the converse is also true.

In agreement with Pauly (2008), moral hazard escalates disparity in healthcare provision. Regardless of the heated debate and need for high deductibles, these are largely imposed on an individual because employer-provided insurance benefits pose a challenge to the implementation of such plans. Dave and Kaestner (2009) mention, moral hazard is associated with avoidance of preventive practice; instead, individuals take up more of the unhealthy behaviors that tend to overwhelm the health care system. Dave and Kaestner (2009) are seconded by Stanciole (2008), who shows a similar behavioral pattern associated with moral hazard. Despite the fact that such effects are realized based on empirical and opinion facts, feasible frameworks to ensure responsible behavior in preventive care and medical utilization are paramount.

Aron-Dine, A., Einav, L., Finkelstein, A., & Cullen, M. (2015). Moral hazard in health insurance: Do dynamic incentives matter? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 97 (4), 725-741.

Dave, D., & Kaestner, R. (2009). Health insurance and ex ante moral hazard: Evidence from Medicare. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics, 9 (4), 367.

Einav, L., Finkelstein, A., Ryan, S. P., Schrimpf, P., & Cullen, M. R. (2013). Selection on moral hazard in health insurance. American Economic Review, 103 (1), 178-219.

Geyman, J. P. (2007). Moral hazard and consumer-driven health care: a fundamentally flawed concept. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, administration, evaluation, 37 (2), 333-351.

Nyman, J. A. (2004). Is ‘Moral Hazard’ inefficient? The policy implications of a new theory. Health Affairs, 23 (5), 194-199.

Nyman, J. A. (2007). American health policy: Cracks in the foundation. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law, 32 (5), 759-783.

Pauly, M. V. (2008). Adverse selection and moral hazard: Implications for health insurance markets. In F. A. Sloan & H. Kasper (Eds.) , Incentives and Choice in Health Care (pp. 103-130). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stanciole, A. E. (2008). Health insurance and lifestyle choices: Identifying Ex ante moral hazard in the US market. The Geneva Papers, 33, 627-644.

Thoma, M. (2013). Explainer: What is “moral hazard”? Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, May 4). Moral Hazard in Healthcare Insurance. https://studycorgi.com/moral-hazard-in-healthcare-insurance/

"Moral Hazard in Healthcare Insurance." StudyCorgi , 4 May 2022, studycorgi.com/moral-hazard-in-healthcare-insurance/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'Moral Hazard in Healthcare Insurance'. 4 May.

1. StudyCorgi . "Moral Hazard in Healthcare Insurance." May 4, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/moral-hazard-in-healthcare-insurance/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Moral Hazard in Healthcare Insurance." May 4, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/moral-hazard-in-healthcare-insurance/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "Moral Hazard in Healthcare Insurance." May 4, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/moral-hazard-in-healthcare-insurance/.

This paper, “Moral Hazard in Healthcare Insurance”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: August 27, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

Moral Hazard in Health Insurance: What We Know and How We Know It

- Author & abstract

- Download & other version

- 29 References

- 56 Citations

- Most related

- Related works & more

Corrections

- Liran Einav

- Amy Finkelstein

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher, other versions of this item:, references listed on ideas.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Moral-Hazard Myth

By Malcolm Gladwell

Tooth decay begins, typically, when debris becomes trapped between the teeth and along the ridges and in the grooves of the molars. The food rots. It becomes colonized with bacteria. The bacteria feeds off sugars in the mouth and forms an acid that begins to eat away at the enamel of the teeth. Slowly, the bacteria works its way through to the dentin, the inner structure, and from there the cavity begins to blossom three-dimensionally, spreading inward and sideways. When the decay reaches the pulp tissue, the blood vessels, and the nerves that serve the tooth, the pain starts—an insistent throbbing. The tooth turns brown. It begins to lose its hard structure, to the point where a dentist can reach into a cavity with a hand instrument and scoop out the decay. At the base of the tooth, the bacteria mineralizes into tartar, which begins to irritate the gums. They become puffy and bright red and start to recede, leaving more and more of the tooth’s root exposed. When the infection works its way down to the bone, the structure holding the tooth in begins to collapse altogether.

Several years ago, two Harvard researchers, Susan Starr Sered and Rushika Fernandopulle, set out to interview people without health-care coverage for a book they were writing, “Uninsured in America.” They talked to as many kinds of people as they could find, collecting stories of untreated depression and struggling single mothers and chronically injured laborers—and the most common complaint they heard was about teeth. Gina, a hairdresser in Idaho, whose husband worked as a freight manager at a chain store, had “a peculiar mannerism of keeping her mouth closed even when speaking.” It turned out that she hadn’t been able to afford dental care for three years, and one of her front teeth was rotting. Daniel, a construction worker, pulled out his bad teeth with pliers. Then, there was Loretta, who worked nights at a university research center in Mississippi, and was missing most of her teeth. “They’ll break off after a while, and then you just grab a hold of them, and they work their way out,” she explained to Sered and Fernandopulle. “It hurts so bad, because the tooth aches. Then it’s a relief just to get it out of there. The hole closes up itself anyway. So it’s so much better.”

People without health insurance have bad teeth because, if you’re paying for everything out of your own pocket, going to the dentist for a checkup seems like a luxury. It isn’t, of course. The loss of teeth makes eating fresh fruits and vegetables difficult, and a diet heavy in soft, processed foods exacerbates more serious health problems, like diabetes. The pain of tooth decay leads many people to use alcohol as a salve. And those struggling to get ahead in the job market quickly find that the unsightliness of bad teeth, and the self-consciousness that results, can become a major barrier. If your teeth are bad, you’re not going to get a job as a receptionist, say, or a cashier. You’re going to be put in the back somewhere, far from the public eye. What Loretta, Gina, and Daniel understand, the two authors tell us, is that bad teeth have come to be seen as a marker of “poor parenting, low educational achievement and slow or faulty intellectual development.” They are an outward marker of caste. “Almost every time we asked interviewees what their first priority would be if the president established universal health coverage tomorrow,” Sered and Fernandopulle write, “the immediate answer was ‘my teeth.’ ”

The U. S. health-care system, according to “Uninsured in America,” has created a group of people who increasingly look different from others and suffer in ways that others do not. The leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States is unpaid medical bills. Half of the uninsured owe money to hospitals, and a third are being pursued by collection agencies. Children without health insurance are less likely to receive medical attention for serious injuries, for recurrent ear infections, or for asthma. Lung-cancer patients without insurance are less likely to receive surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation treatment. Heart-attack victims without health insurance are less likely to receive angioplasty. People with pneumonia who don’t have health insurance are less likely to receive X rays or consultations. The death rate in any given year for someone without health insurance is twenty-five per cent higher than for someone with insur-ance. Because the uninsured are sicker than the rest of us, they can’t get better jobs, and because they can’t get better jobs they can’t afford health insurance, and because they can’t afford health insurance they get even sicker. John, the manager of a bar in Idaho, tells Sered and Fernandopulle that as a result of various workplace injuries over the years he takes eight ibuprofen, waits two hours, then takes eight more—and tries to cadge as much prescription pain medication as he can from friends. “There are times when I should’ve gone to the doctor, but I couldn’t afford to go because I don’t have insurance,” he says. “Like when my back messed up, I should’ve gone. If I had insurance, I would’ve went, because I know I could get treatment, but when you can’t afford it you don’t go. Because the harder the hole you get into in terms of bills, then you’ll never get out. So you just say, ‘I can deal with the pain.’ ”

One of the great mysteries of political life in the United States is why Americans are so devoted to their health-care system. Six times in the past century—during the First World War, during the Depression, during the Truman and Johnson Administrations, in the Senate in the nineteen-seventies, and during the Clinton years—efforts have been made to introduce some kind of universal health insurance, and each time the efforts have been rejected. Instead, the United States has opted for a makeshift system of increasing complexity and dysfunction. Americans spend $5,267 per capita on health care every year, almost two and half times the industrialized world’s median of $2,193; the extra spending comes to hundreds of billions of dollars a year. What does that extra spending buy us? Americans have fewer doctors per capita than most Western countries. We go to the doctor less than people in other Western countries. We get admitted to the hospital less frequently than people in other Western countries. We are less satisfied with our health care than our counterparts in other countries. American life expectancy is lower than the Western average. Childhood-immunization rates in the United States are lower than average. Infant-mortality rates are in the nineteenth percentile of industrialized nations. Doctors here perform more high-end medical procedures, such as coronary angioplasties, than in other countries, but most of the wealthier Western countries have more CT scanners than the United States does, and Switzerland, Japan, Austria, and Finland all have more MRI machines per capita. Nor is our system more efficient. The United States spends more than a thousand dollars per capita per year—or close to four hundred billion dollars—on health-care-related paperwork and administration, whereas Canada, for example, spends only about three hundred dollars per capita. And, of course, every other country in the industrialized world insures all its citizens; despite those extra hundreds of billions of dollars we spend each year, we leave forty-five million people without any insurance. A country that displays an almost ruthless commitment to efficiency and performance in every aspect of its economy—a country that switched to Japanese cars the moment they were more reliable, and to Chinese T-shirts the moment they were five cents cheaper—has loyally stuck with a health-care system that leaves its citizenry pulling out their teeth with pliers.

America’s health-care mess is, in part, simply an accident of history. The fact that there have been six attempts at universal health coverage in the last century suggests that there has long been support for the idea. But politics has always got in the way. In both Europe and the United States, for example, the push for health insurance was led, in large part, by organized labor. But in Europe the unions worked through the political system, fighting for coverage for all citizens. From the start, health insurance in Europe was public and universal, and that created powerful political support for any attempt to expand benefits. In the United States, by contrast, the unions worked through the collective-bargaining system and, as a result, could win health benefits only for their own members. Health insurance here has always been private and selective, and every attempt to expand benefits has resulted in a paralyzing political battle over who would be added to insurance rolls and who ought to pay for those additions.

Policy is driven by more than politics, however. It is equally driven by ideas, and in the past few decades a particular idea has taken hold among prominent American economists which has also been a powerful impediment to the expansion of health insurance. The idea is known as “moral hazard.” Health economists in other Western nations do not share this obsession. Nor do most Americans. But moral hazard has profoundly shaped the way think tanks formulate policy and the way experts argue and the way health insurers structure their plans and the way legislation and regulations have been written. The health-care mess isn’t merely the unintentional result of political dysfunction, in other words. It is also the deliberate consequence of the way in which American policymakers have come to think about insurance.

“Moral hazard” is the term economists use to describe the fact that insurance can change the behavior of the person being insured. If your office gives you and your co-workers all the free Pepsi you want—if your employer, in effect, offers universal Pepsi insurance—you’ll drink more Pepsi than you would have otherwise. If you have a no-deductible fire-insurance policy, you may be a little less diligent in clearing the brush away from your house. The savings-and-loan crisis of the nineteen-eighties was created, in large part, by the fact that the federal government insured savings deposits of up to a hundred thousand dollars, and so the newly deregulated S. & L.s made far riskier investments than they would have otherwise. Insurance can have the paradoxical effect of producing risky and wasteful behavior. Economists spend a great deal of time thinking about such moral hazard for good reason. Insurance is an attempt to make human life safer and more secure. But, if those efforts can backfire and produce riskier behavior, providing insurance becomes a much more complicated and problematic endeavor.

In 1968, the economist Mark Pauly argued that moral hazard played an enormous role in medicine, and, as John Nyman writes in his book “The Theory of the Demand for Health Insurance,” Pauly’s paper has become the “single most influential article in the health economics literature.” Nyman, an economist at the University of Minnesota, says that the fear of moral hazard lies behind the thicket of co-payments and deductibles and utilization reviews which characterizes the American health-insurance system. Fear of moral hazard, Nyman writes, also explains “the general lack of enthusiasm by U.S. health economists for the expansion of health insurance coverage (for example, national health insurance or expanded Medicare benefits) in the U.S.”