- Systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 15 July 2019

Use of health economic evaluation in the implementation and improvement science fields—a systematic literature review

- Sarah Louise Elin Roberts ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6807-9830 1 ,

- Andy Healey 1 , 2 &

- Nick Sevdalis 2

Implementation Science volume 14 , Article number: 72 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

71 Citations

50 Altmetric

Metrics details

Economic evaluation can inform whether strategies designed to improve the quality of health care delivery and the uptake of evidence-based practices represent a cost-effective use of limited resources. We report a systematic review and critical appraisal of the application of health economic methods in improvement/implementation research.

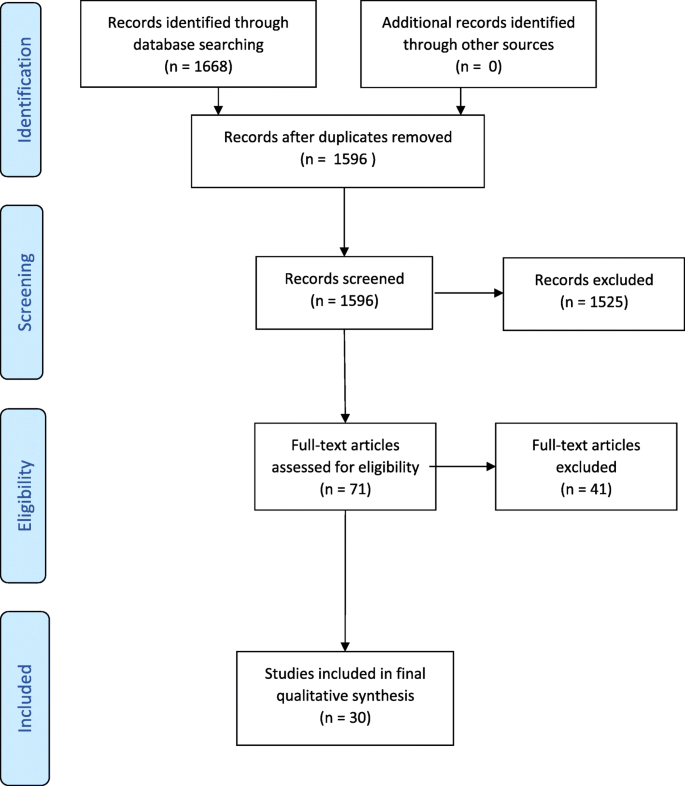

A systematic literature search identified 1668 papers across the Agris, Embase, Global Health, HMIC, PsycINFO, Social Policy and Practice, MEDLINE and EconLit databases between 2004 and 2016. Abstracts were screened in Rayyan database, and key data extracted into Microsoft Excel. Evidence was critically appraised using the Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) framework.

Thirty studies were included—all health economic studies that included implementation or improvement as a part of the evaluation. Studies were conducted mostly in Europe (62%) or North America (23%) and were largely hospital-based (70%). The field was split between improvement ( N = 16) and implementation ( N = 14) studies. The most common intervention evaluated (43%) was staffing reconfiguration, specifically changing from physician-led to nurse-led care delivery. Most studies ( N = 19) were ex-post economic evaluations carried out empirically—of those, 17 were cost effectiveness analyses. We found four cost utility analyses that used economic modelling rather than empirical methods. Two cost-consequence analyses were also found. Specific implementation costs considered included costs associated with staff training in new care delivery pathways, the impacts of new processes on patient and carer costs and the costs of developing new care processes/pathways. Over half (55%) of the included studies were rated ‘good’ on QHES. Study quality was boosted through inclusion of appropriate comparators and reporting of incremental analysis (where relevant); and diminished through use of post-hoc subgroup analysis, limited reporting of the handling of uncertainty and justification for choice of discount rates.

Conclusions

The quantity of published economic evaluations applied to the field of improvement and implementation research remains modest; however, quality is overall good. Implementation and improvement scientists should work closely with health economists to consider costs associated with improvement interventions and their associated implementation strategies. We offer a set of concrete recommendations to facilitate this endeavour.

Peer Review reports

Both improving health care and implementation of evidence-based practices are receiving increasing attention within the wider applied health research field. A recent editorial in Implementation Science [ 1 ] discussed the importance implementation science places on the robustness and validity of health economic evaluations and the benefits gained by properly evaluating both implementation and improvement interventions. We define improvement science as the scientific approach to achieving better patient experience and outcomes through changing provider behaviour and organisation, using systematic change methods and strategies [ 2 ]. We define implementation science as the scientific study of methods to promote the uptake of research findings into routine health care practice or policy [ 2 ].

This paper presents a review of the application of economic evaluation to evaluative studies of service improvement initiatives and interventions focused on facilitating the implementation of evidence into practice. The aim of economic evaluation is to present evidence on the costs and consequences (in terms of patient outcomes) of quality improvement strategies and methods for increasing the uptake of evidence-based practices compared to the ‘status quo’. In doing so, it informs whether specific initiatives are (or have been) a worthwhile (or ‘cost-effective’) use of the limited resources of health systems.

Depending on the service and population context, the methods used in economic evaluations can vary depending on the perspective taken. This can range from a narrow assessment of patient outcomes alongside immediate health care provider cost impacts through to the quantification of costs and consequences affecting other (non-health related) sectors, organisations and wider society. In health programme evaluation, economic evaluations are most frequently carried out ‘ex-post’ or ‘after the fact’, using empirical methods applied to cost and outcome data extracted from trials or other research designs used to evaluate initiatives being tested in specific populations and settings. Economic evaluations can also be applied ‘ex-ante’—to inform option appraisal and pre-implementation decision making using available evidence and modelling to simulate the costs and outcomes of alternatives, e.g. in relation to population scale up or geographical spread of strategies and methods for improvement and evidence uptake.

While economic evaluation has become an integral part of health technology assessment, its application within improvement and implementation evaluative research remains relatively limited [ 1 ]. In two earlier reviews (Hoomans et al. in 2007 [ 3 ] and earlier Grimshaw et al. in 2004 [ 4 ]), the use of economic methods in evaluating the implementation of evidence-based guidelines was examined, and the authors found evidence of limited quality and scope for understanding the cost-effectiveness of implementation strategies. It is now over a decade since these reviews were published, hence a fresh evidence review, synthesis and appraisal is required.

The aim of this study was to examine what advances have been made in the use of economic analysis within implementation and improvement science research, specifically in relation to the quantity and quality of published economic evidence in this field; and to what extent economic evaluations have considered implementation and improvement as part of a holistic approach to evaluating interventions or programmes within the applied health arena.

Search strategy

A systematic review methodology was undertaken. A search strategy was developed to capture evidence published after 2003 (the date of most recent evidence review) and the last searches were performed on 16th March 2016. The searches were performed on the following databases: Agris, Embase, Global Health, HMIC, PsycINFO, Social Policy and Practice, MEDLINE and EconLit. These databases were chosen to attempt to capture the widest range of health improvement, social scientific and health economic studies.

The search strategy (Table 1 ) was designed to capture studies that had a quantitative economic element (i.e. costs and outcomes based on randomised trial data, observational study data or synthesis of the wider empirical evidence base to support economic modelling). The search was conducted to be inclusive of studies whereby behavioural interventions for quality improvement and implementation of evidence into practice were evaluated as well as initiatives around re-design or adjustment to care pathways or reconfiguration of staffing inputs for the purpose of quality improvement.

We searched across a wide range of clinical settings, including primary, secondary and tertiary care and public health.

The completed search results were downloaded into Endnote X6 for citation management and deduplication. Screening was done in Rayyan, a web-based literature screening program [ 6 ]. Rayyan allows for easy abstract and full text screening of studies, custom inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as custom tags or labels that can be added to each entry. Studies were initially screened using the inclusion/exclusion criteria outlined in the next section, on title and abstract only (by SLER); studies that were borderline for inclusion were more thoroughly screened by examining their full text. The reference lists of the studies were checked for any related studies that were not picked up by the search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they:

Were published in the English language

Reported on a completed study

Study protocols, methodological papers or conference abstracts were excluded (after additional searches had been performed to ensure that full papers had not been subsequently published).

Were published after 2003 and before 16th March 2016

Were conducted in public health, primary, secondary or tertiary care

Further, studies were included if they covered aspects of:

Implementation

Quality/service improvement

Health or clinical service delivery

Staff behaviour change

Patient behaviour change

And they also:

Had patient focused outcomes or outcomes as overall service improvement that would improve patient outcomes or care, expressed as quantifiable outcomes

Had economic elements, expressed as quantifiable outcomes

Reported one of the following health economic methodologies:

Cost effectiveness analysis

Cost-utility analysis

Cost-benefit analysis

Cost-consequence analysis

Burden of disease

The following study designs were included:

Randomised controlled trials

Hybrid effectiveness-implementation trials

Comparative controlled trials without random assignment

Before and after studies

Systematic reviews

Time series study design

Studies or papers that did not fall within the above criteria were excluded. No geographical exclusions were applied. Cost-only studies were not included as the aim of this review was to establish the extent that both costs and benefits were being considered as part of a holistic approach to evaluation of implementation and improvement interventions.

To mitigate for potential selection bias after screening, keyword searching was done in Rayyan for the main keywords within the excluded categories (primarily, those that were deemed to be topic-relevant but not containing economic methods). These were then re-screened by the first author. Studies that included only minimal discussion of costs or costing with no evidence of application of appropriate, standard costing methods (as per the criteria above) were excluded.

Data extraction

Screened studies were downloaded from Rayyan and transferred into a template developed in Microsoft Excel 2016 for detailed data extraction. During screening, each included study was tagged in Rayyan with the reasons for inclusion, type of economic evaluation (see Table 2 ), which economic modelling method used (if applicable), whether improvement or implementation study, the health condition covered, the focus of the reported intervention and health care setting. These were cross-checked for accuracy during the data extraction stage. The next stage of the extraction added the country of the study, perspective of the study (healthcare only or ‘societal’), and more detailed information about the economic methods. The latter included whether the evaluation included appropriate comparators (e.g. status quo/the standard care practice), patient outcome measures used, whether costs and outcomes were analysed and reported in the form of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) for cost-effectiveness or cost-utility analyses, how uncertainty was handled and what conclusions were made regarding the cost-effectiveness of the interventions under evaluation.

Quality appraisal

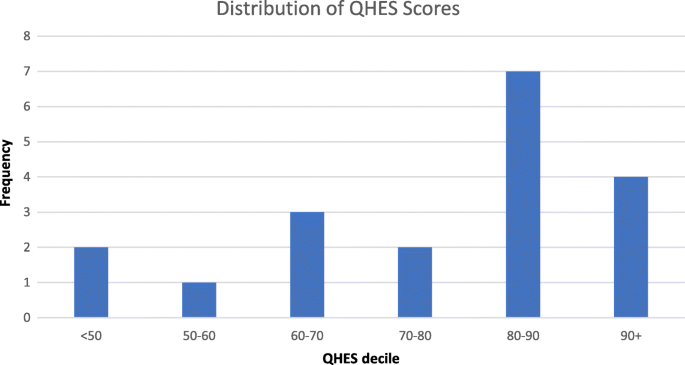

Each paper’s methodological quality was assessed using the Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) standardised framework [ 4 ]. The QHES instrument was designed to more easily tell the difference between high-quality and low-quality studies [ 5 ]. Each study was scored out of 100 based on 16 criteria, with points allocated for full and partial assessments against each item (see Appendix in Table 7 for the framework and scoring system). As per standard practice using this framework, the studies were deemed to be of good quality if they attained a score of 75/100 or higher [ 5 ].

Studies included

Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the screening stages of the systematic review.

Consort diagram

In total, the initial search strategy identified 1668 articles, of which 1566 were excluded, 1525 during the initial screen and 41 following full text screening. Reasons for exclusion were as follows: the study did not include implementation or quality improvement research aspects (575); it did not include economic aspects (447); was not within a health care/public health setting (437); it was in a language other than English (22); it was incomplete (19); or it was not a full refereed publication (e.g. conference abstracts, doctoral theses) (37).

Thirty studies were included in the final evidence review and synthesis.

Descriptive analysis of the evidence base

Table 3 provides a descriptive overview of the evidence base reported in the 30 reviewed studies. Seventeen of the studies (62%) were European-based (mostly from the UK—12 studies), six studies (23%) were based in either the USA or Canada, four from Australia and one each from Ethiopia, a subset of African countries (Uganda, Kenya and South Africa) and Malaysia. In terms of health care settings, 21 studies were hospital-based, approximately half in inpatient wards and departments, including cardiology, oncology, rheumatology, gastroenterology, geriatrics, endocrinology, orthopaedics and respiratory medicine, or specifically concerning ward management or discharge protocols.

Sixteen of the included studies were identified as ‘improvement’ studies (see Table 3 , panel 1a) and 14 were identified as ‘implementation’ studies (see Table 3 , panel 1b). The definitions from Batalden and Davidoff (2007) that are cited in the introduction were used to stratify the studies. The most common focus of the reviewed improvement studies was staff reconfigurations within a clinical area from medical to nursing staff; for implementation studies, the most common focus was on implementation strategies of new care pathways or novel services.

Table 4 summarises the types of intervention evaluated. The most common intervention type, evaluated in 13 (43%) of the included studies, was staffing reconfiguration for service quality improvement, specifically changing from physician-led to nurse-led delivery of interventions to patients. More broadly, interventions involving general service reorganisation or changes to existing systems of care were the primary focus in ten (33%) of studies reviewed.

Nineteen studies were ex-post economic evaluations of which 17 were CEAs with one CUA [ 7 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 17 ] [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 33 ]. All these evaluations compared a new intervention against current practice. There were also four further CUAs that used economic modelling rather than empirical methods [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 34 ], and two cost-consequence analyses [ 16 , 35 ]. Three of the included studies were literature reviews [ 11 , 13 , 36 ].

Specific implementation costs, such as those associated with training staff in new care delivery pathways, the impacts of new processes on patient and carer costs and the costs of developing the new processes were considered by six of the reviewed studies. Scenario analysis for rollout or scaling up was included in three of the studies, and potential funding sources were considered by one study.

Twenty-two of the papers were included in the QHES economic quality appraisal: as the quality scale is designed to evaluate cost-minimisation, cost-effectiveness and cost-utility studies [ 5 ], the literature reviews, meta-analyses or commentaries were excluded for this component. Of the excluded papers, four were systematic reviews and four were papers that did not report on specific studies. The QHES instrument contains 16 dimensions and an outline of the dimensions, the average score and the percentage of the papers reaching the perfect score for each dimension can be found in Table 5 . While most of the papers in this study reached the threshold of being ‘good’ studies, the scores are gained mostly in the same areas in each paper. The average quality score was 76 out of a possible 100 (Fig. 2 ). Thirteen of the studies (62%) attained a ‘good’ score of over 75. Only one study [ 33 ] obtained a ‘perfect’ score of 100 points. Improvement studies performed overall better than implementation studies on the QHES.

Quality appraisal of economic evidence—distribution of QHES instrument scores

The best performing QHES dimensions were the methodological dimensions. Incremental analysis with a relevant comparator (dimension 6) was used in all but one study, and in 81% of studies the data sources for the analysis were from randomised controlled trials, the highest scoring type of evidence in the QHES instrument (Table 6 ). The costing element, covered by dimension 9, performed poorly overall. While three quarters of studies gave details of what methodology was used to quantify service inputs (such as use of self-report service use schedules) and the sources and methods used for estimating unit costs, only two gave justification for why they chose that method. By comparison, there was justification for the use of effectiveness measures and study outcomes given in two-thirds of studies.

Discount rates were correctly applied and stated when adjusting for timing of costs and benefits in all cases where measured costs and outcomes extended beyond 1 year.

A little over a quarter of the included studies declared the perspective of their analysis and gave a justification for the perspective used. Only a third gave details of how parameter uncertainty was addressed in relation to the study conclusions. Justification for chosen discount rates was not provided in around half the studies that used them. Where subgroup analysis was carried out, this was done post-hoc rather than being pre-planned with a clear a priori justification for the use of the chosen subgroups.

Reflections on the evidence

The aim of this review was to critically evaluate the application of economic analysis within implementation and service improvement evaluative research in recent years. The results of evaluating the 30 included papers paint a picture of an area of research that is still developing. The reviewed studies were generally of good quality. However, we found that there were aspects of improvement and implementation that were not adequately covered in many studies. These reflect particularly project costs relating to managerial and clinical time allocated to preparatory work and training and education as well as ongoing costs linked to monitoring care quality and outcomes—all of which are known strategies for successful implementation [ 37 ]. Only six out of 30 studies included an explicit assessment of these type of ‘hidden’ costs of improvement and implementation strategies. This risks underestimating the cost impacts of change and could represent a missed opportunity to develop evidence about the likely comparative magnitude and importance of fixed and recurrent costs that are integral to the scale up and spread of improvement- and implementation-focussed initiatives.

A further reflection: many of the economic studies picked up in our review were linked to wider studies built around more traditional evaluative research designs, specifically randomised controlled trials. There was no evidence that economic methods have as yet been integrated into more advanced evaluative designs within the fields of improvement and implementation design, particularly ‘hybrid’ designs [ 38 , 39 ] that aim to jointly test clinical effectiveness of the evaluated health intervention on patient outcomes and, simultaneously, effectiveness of implementation strategies in embedding the clinical intervention within an organisation or service. This may reflect the fact that hybrid designs are a more recent methodological development, which requires further integration into traditional health care evaluations.

Furthermore, and in relation to the wider role of health economic evaluations within the improvement and implementation science arena, we found that all of the studies included in our review were empirical and ex-post in nature. The studies evaluated costs and outcomes retrospectively using data over a period of time following the introduction of a specific improvement or implementation initiative. This is certainly valuable information for decision makers in making decisions about already applied interventions and in building up an economic evidence base around these interventions. However, it also suggests that economic analysis, and particularly economic modelling, currently at least appears to have a less important role in informing decisions over which options to pursue at earlier stages of implementing change, and in the appraisal of spread and scale up within wider populations. Such earlier phase economic analyses were simply not found in our review. We reflect that either this type of economic analysis is not happening—hence there is a significant gap in the application of economic considerations in improvement and implementation policy decisions; or that such analyses may indeed be undertaken but being less likely to be reported in academic publications and thus under-represented in our review. We cannot rule out either possibility based on this review. Our collective experience suggests that more nuanced economic analyses than simply consideration of ‘costs’ should be carried out in early phases of implementation and improvement programme planning; prospective economic modelling offers a way forward for health care improvers and policy makers planning scale up of evidence interventions.

Quality of the evidence

Comparison between economic studies identified in a previous review carried out by Hoomans et al. (covering the immediately preceding period 1998 to 2004) with those identified in this review (2004 to 2016) shows evidence of a general improvement in quality over the past two decades, with the caveat that the two reviews used different quality appraisal frameworks. For example, only 42% of studies reviewed by Hoomans et al. included evaluation of costs and outcomes against ‘standard practice/status quo’ comparators, compared to 95% of studies in our review. Likewise, costing methodology was only deemed adequate in 11% of cases included in the Hoomans et al. review, compared to 76% of the studies in this review. Justification for the outcome measures used was not reported in any of the studies included in Hoomans et al. but reported in 68% of studies included here. This is a welcome improvement of applied economics within health care implementation and improvement research. We attribute it at least partly to improvements in reporting economic analyses over time, which would appear to have made an impact on the studies we captured. Additionally, the expanding application of health economic evaluations within the improvement and implementation sphere where high-quality study reporting has been a major recent focus has also plausibly contributed to improved reporting. Future evidence reviews will confirm whether this pattern is sustained over time.

Strengths and limitations

This review offers an updated synthesis of an emerging field of economics evaluations of health care intervention evaluations covering both implementation and improvement science studies. The strict inclusion criteria mean that the reviewed evidence is cohesive. The systematic appraisal we carried out also allows us a longitudinal critique of the quality of economic studies in this field. Despite not being able to directly compare the quality assessment from the previous reviews, we would argue that the QHES used here is based on Drummond’s guidelines (used in prior reviews) and is designed to cover the same topics, but offers a simpler, quantifiable format that is easier to apply. [ 32 ]

This review has some limitations. First, while our search strategy was quite broad, our inclusion criteria were strict, which may have limited the number of studies that we identified and synthesised. We aimed to clearly demarcate the economic analyses carried out within healthcare implementation and improvement interventions research—and to explicitly include papers that included both costs and benefits, and so did not include cost-only studies. We also only considered papers reported in English. Taken together, these criteria are stricter than those applied to prior reviews, which were more inclusive of qualitative outcomes and costing studies.

Implications for implementation and improvement research and future directions

Our review demonstrates an increasing number of health economic evaluations nested within implementation and improvement research studies, which further appear to be improving in methodological quality in recent years. Based on our review, we offer the following recommendations and areas for improvement in the continued application of health economic methods to improvement and implementation science evaluative research:

Utilise published guidance on conducting economic evaluation in implementation research and quality improvement projects. Existing implementation frameworks [ 40 ] make reference to the need to consider costs as part of an evaluative research strategy, but do not specify how this is to be done. The relationship between implementation outcomes, service outcomes and patient outcomes is central to understanding the benefits and costs and overall cost-effectiveness of an intervention.

Include detailed consideration of the measurement of the resource implications and ‘hidden’ costs relating to wider support activities required to initiate service improvement or to implement evidence into practice (e.g. costs of manualising an intervention; costs of developing and delivering train-the-trainers interventions as implementation strategies and so on).

Ensure that economic methods become fully integrated into the application of more recent methodological advancements in the evaluative design of improvement and implementation strategies, including ‘hybrid’ designs that seek to jointly test impact on implementation and patient outcomes. This would also provide an opportunity to explore the inter-linkages and relationships between implementation outcomes and economic measures of impact and the cost-effectiveness of improvement and implementation strategies.

While most of the economic studies included in this review were both ex-post and empirical, we would also highlight the value of ex-ante economic evaluation in policy-making contexts. This could be informative either at the early phase of an improvement or implementation project, to guide choices over which options are most likely to yield a cost-effective use of resources (and to rule out those that are likely to be excessively costly compared to expected benefits), or for quantifying the benefits and costs of spread of best practice and delivery at scale.

Finally, we would strongly recommend use of published guidelines and quality assurance frameworks to guide both the design and reporting of economic evaluations. Examples include the QHES framework (used here), the Consolidated Health Economic Reporting Standards (CHEERS) guidance [ 32 ] or the Drummond criteria [ 31 ].

Economic evaluation can inform choices over whether and how resources should be allocated to improve services and for implementing evidence into health care practice. Our systematic review of the recent literature has shown that the quality of economic evidence in the field of improvement and implementation science has improved over time, though there remains scope for continued improvement in key areas and for increased collaboration between health economics and implementation science.

Hoomans T, Severens JL. Economic evaluation of implementation strategies in health care. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):168.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):2.

Hoomans T, Evers SMAA, Ament AJHA, Hübben MWA, Van Der Weijden T, Grimshaw JM, et al. The methodological quality of economic evaluations of guideline implementation into clinical practice: a systematic review of empiric studies. Value Health. 2007;10(4):305–16.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(1):149.

Article Google Scholar

Ofman JJ, Sullivan SD, Neumann PJ, Chiou C-F, Henning JM, Wade SW, et al. Examining the value and quality of health economic analyses: implications of utilizing the QHES. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9(1):53–61.

PubMed Google Scholar

Elmagarmid A, Fedorowicz Z, Hammady H, Ilyas I, Khabsa M, Ouzzani M. Rayyan: a systematic reviews web app for exploring and filtering searches for eligible studies for Cochrane reviews. In: Evidence-informed public health: opportunities and challenges. Abstracts of the 22nd Cochrane colloquium. Hyderabad: Wiley; 2014. p. 21–6.

Google Scholar

Latour CHM, Bosmans JE, van Tulder MW, de Vos R, Huyse FJ, de Jonge P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a nurse-led case management intervention in general medical outpatients compared with usual care: an economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(3):363–70.

Burr JM, Mowatt G, Hernández R, Siddiqui MA, Cook J, Lourenco T, Ramsay C, Vale L, Fraser C, Azuara-Blanco A, Deeks J. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening for open angle glaucoma: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess (Winch. Eng.). 2007;11(41):1–90.

Burr JM, Botello-Pinzon P, Takwoingi Y, Hernández R, Vazquez-Montes M, Elders A, Asaoka R, Banister K, van der Schoot J, Fraser C, King A, Lemij H, Sanders R, Vernon S, Tuulonen A, Kotecha A, Glasziou P, Garway-Heath D, Crabb D, Vale L, Azuara-Blanco A, Perera R, Ryan M, Deeks J, Cook J. Surveillance for ocular hypertension : an evidence synthesis and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(29):1–272.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Robertson C, Arcot Ragupathy SK, Boachie C, Dixon JM, Fraser C, Hernández R, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different surveillance mammography regimens after the treatment for primary breast cancer: systematic reviews registry database analyses and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess (Winch. Eng.). 2011;15(34):v–322.

CAS Google Scholar

Umscheid CA, Williams K, Brennan PJ. Hospital-based comparative effectiveness centers: translating research into practice to improve the quality, safety and value of patient care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1352–5.

Albers-Heitner CP, Joore MA, Winkens RA, Lagro-Janssen AL, Severens JL, Berghmans LC. Cost-effectiveness of involving nurse specialists for adult patients with urinary incontinence in primary care compared to care-as-usual: an economic evaluation alongside a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31(4):526–34.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Faulkner A, Mills N, Bainton D, Baxter K, Kinnersley P, Peters TJ. Sharp D. a systematic review of the effect of primary care-based service innovations on quality and patterns of referral to specialist secondary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(496):878–84.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bauer JC. Nurse practitioners as an underutilized resource for health reform: evidence-based demonstrations of cost-effectiveness. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2010;22(4):228–31.

Brunenberg DE, van Steyn MJ, Sluimer JC, Bekebrede LL, Bulstra SK, Joore MA. Joint recovery programme versus usual care: an economic evaluation of a clinical pathway for joint replacement surgery. Med Care. 2005:1018–26.

Dawes HA, Docherty T, Traynor I, Gilmore DH, Jardine AG, Knill-Jones R. Specialist nurse supported discharge in gynaecology: a randomised comparison and economic evaluation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;130(2):262–70.

Furze G, Cox H, Morton V, Chuang LH, Lewin RJ, Nelson P, Carty R, Norris H, Patel N, Elton P. Randomized controlled trial of a lay-facilitated angina management programme. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(10):2267–79.

Judd WR, Stephens DM, Kennedy CA. Clinical and economic impact of a quality improvement initiative to enhance early recognition and treatment of sepsis. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(10):1269–75.

Kifle YA, Nigatu TH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of clinical specialist outreach as compared to referral system in Ethiopia: an economic evaluation. Cost Eff Resource Allocation. 2010;8(1):13.

Kilpatrick K, Kaasalainen S, Donald F, Reid K, Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, Martin-Misener R, Harbman P, Marshall DA, Charbonneau-Smith R, DiCenso A. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of clinical nurse specialists in outpatient roles: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(6):1106–23.

Maloney S, Haas R, Keating JL, Molloy E, Jolly B, Sims J, Morgan P, Haines T. Breakeven, cost benefit, cost effectiveness, and willingness to pay for web-based versus face-to-face education delivery for health professionals. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e47.

Mortimer D, French SD, McKenzie JE, Denise AO, Green SE. Economic evaluation of active implementation versus guideline dissemination for evidence-based care of acute low-back pain in a general practice setting. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75647.

Purshouse RC, Brennan A, Rafia R, Latimer NR, Archer RJ, Angus CR, Preston LR, Meier PS. Modelling the cost-effectiveness of alcohol screening and brief interventions in primary care in England. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;48(2):180–8.

Rachev BT. The economics of health service transformation: a business model for care coordination for chronic condition patients in the UK and US. Clin Gov An Int J. 2015;20(3):113–22.

Tappenden P, Campbell F, Rawdin A, Wong R, Kalita N. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home-based, nurse-led health promotion for older people: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess (Winch. Eng.). 2012;16(20):1.

Tappenden P, Chilcott J, Brennan A, Squires H, Glynne-Jones R, Tappenden J. Using whole disease modeling to inform resource allocation decisions: economic evaluation of a clinical guideline for colorectal cancer using a single model. Value Health. 2013;16(4):542–53.

Vestergaard AS, Ehlers LH. A health economic evaluation of stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: guideline adherence versus the observed treatment strategy prior to 2012 in Denmark. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(9):967–79.

Williams KS, Assassa RP, Cooper NJ, Turner DA, Shaw C, Abrams KR, Mayne C, Jagger C, Matthews R, Clarke M, McGrother CW. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of a new nurse-led continence service: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(518):696–703.

Williams J, Russell I, Durai D, Cheung WY, Farrin A, Bloor K, Coulton S, Richardson G. What are the clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness of endoscopy undertaken by nurses when compared with doctors? A multi-institution nurse endoscopy trial (MINuET). Health Technol Assess. 2006;10(40):1–93.

Yarbrough PM, Kukhareva PV, Spivak ES, Hopkins C, Kawamoto K. Evidence-based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(12):780–6.

Drummond MF, Jefferson TO. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. BMJ. 1996;313(7052):275–83.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs AH, Mauskopf J, Loder E. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Cost Eff Resource Allocation. 2013;11(1):6.

Afzali HH, Gray J, Beilby J, Holton C, Karnon J. A model-based economic evaluation of improved primary care management of patients with type 2 diabetes in Australia. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(6):661–70.

Hernández RA, Jenkinson D, Vale L, Cuthbertson BH. Economic evaluation of nurse-led intensive care follow-up programmes compared with standard care: the PRaCTICaL trial. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(3):243–52.

Karnon J, Partington A, Horsfall M, Chew D. Variation in clinical practice: a priority setting approach to the staged funding of quality improvement. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2016;14(1):21–7.

Mdege ND, Chindove S, Ali S. The effectiveness and cost implications of task-shifting in the delivery of antiretroviral therapy to HIV-infected patients: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2012;28(3):223–36.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JE. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21.

Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217.

Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Wells KB, Jones L, Collins LM, Duan N, Mittman BS, Wallace A, Tabak RG. An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:1–22.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This research is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The authors are members of King’s Improvement Science, which is part of the NIHR CLAHRC South London and comprises a specialist team of improvement scientists and senior researchers based at King’s College London. Its work is funded by King’s Health Partners (Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, King’s College London and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust), Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity, the Maudsley Charity and the Health Foundation. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

King’s Health Economics, Health Service and Population Research Department, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, David Goldberg Centre, De Crespigny Park, London, SE5 8AF, UK

Sarah Louise Elin Roberts & Andy Healey

Centre for Implementation Science, King’s College London, London, UK

Andy Healey & Nick Sevdalis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SLER, AH and NS conceptualised the literature review. SLER performed literature searches, screening and analysis. SLER, AH and NS contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sarah Louise Elin Roberts .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not required.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

Sevdalis is the Director of London Safety and Training Solutions Ltd., which provides quality and safety training and advisory services on a consultancy basis to healthcare organisation globally. The other authors have no interests to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Roberts, S.L.E., Healey, A. & Sevdalis, N. Use of health economic evaluation in the implementation and improvement science fields—a systematic literature review. Implementation Sci 14 , 72 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0901-7

Download citation

Received : 29 August 2018

Accepted : 29 April 2019

Published : 15 July 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0901-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Implementation Science

ISSN: 1748-5908

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

At a glance: The STEP trials

A round-up of the STEP phase 3 clinical trials evaluating semaglutide for weight loss in people with overweight or obesity.

Springer Medicine

Health economics review, latest issues, health economics review 1/2024, health economics review 1/2023, health economics review 1/2022, health economics review 1/2021, health economics review 1/2020, health economics review 1/2019, health economics review 1/2018, health economics review 1/2017, health economics review 1/2016, health economics review 1/2015.

scroll for more

use your arrow keys for more

scroll or use arrow keys for more

About this journal

Health Economics Review is an open-access journal covering all aspects of health economics, from a micro- to macro-scale. We welcome a broad range of theoretical contributions, empirical studies and analyses of health policy with a health economic focus, including the growing importance of health care in developing countries. Research topics include health care finance, health insurance and reimbursement, economics-focused policy analysis and health care management. Our research and authors come from a range of high- middle- and low-income countries.

- Medical Journals

- Webcasts & Webinars

- CME & eLearning

- Newsletters

- ESMO Congress 2023

- 2023 ERS Congress

- ESC Congress 2023

- Advances in Alzheimer’s

- About Springer Medicine

- Diabetology

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology

- Geriatrics and Gerontology

- Gynecology and Obstetrics

- Infectious Disease

- Internal Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Open access

- Published: 02 December 2017

Systematic reviews of health economic evaluations: a protocol for a systematic review of characteristics and methods applied

- Miriam Luhnen 1 , 2 ,

- Barbara Prediger 3 ,

- Edmund A. M. Neugebauer 4 , 5 &

- Tim Mathes 3

Systematic Reviews volume 6 , Article number: 238 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

6151 Accesses

9 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

The number of systematic reviews of economic evaluations is steadily increasing. This is probably related to the continuing pressure on health budgets worldwide which makes an efficient resource allocation increasingly crucial. In particular in recent years, the introduction of several high-cost interventions presents enormous challenges regarding universal accessibility and sustainability of health care systems. An increasing number of health authorities, inter alia, feel the need for analyzing economic evidence.

Economic evidence might effectively be generated by means of systematic reviews. Nevertheless, no standard methods seem to exist for their preparation so far.

The objective of this study was to analyze the methods applied for systematic reviews of health economic evaluations (SR-HE) with a focus on the identification of common challenges.

Methods/design

The planned study is a systematic review of the characteristics and methods actually applied in SR-HE. We will combine validated search filters developed for the retrieval of economic evaluations and systematic reviews to identify relevant studies in MEDLINE (via Ovid, 2015-present). To be eligible for inclusion, studies have to conduct a systematic review of full economic evaluations. Articles focusing exclusively on methodological aspects and secondary publications of health technology assessment (HTA) reports will be excluded. Two reviewers will independently assess titles and abstracts and then full-texts of studies for eligibility. Methodological features will be extracted in a standardized, beforehand piloted data extraction form. Data will be summarized with descriptive statistical measures and systematically analyzed focusing on differences/similarities and methodological weaknesses.

The systematic review will provide a detailed overview of characteristics of SR-HE and the applied methods. Differences and methodological shortcomings will be detected and their implications will be discussed. The findings of our study can improve the recommendations on the preparation of SR-HE. This can increase the acceptance and usefulness of systematic reviews in health economics for researchers and medical decision makers.

Systematic review registration

The review will not be registered with PROSPERO as it does not meet the eligibility criterion of dealing with clinical outcomes.

Peer Review reports

Continuing pressure on health budgets worldwide makes an efficient resource allocation increasingly crucial. In recent years, the introduction of several high-cost interventions presents enormous challenges regarding accessibility and sustainability of health care systems [ 1 , 2 ]. This makes economic considerations more important for health authorities and their decision-making process regarding pricing and reimbursement especially of new interventions.

Systematic reviews of health economic evaluations (SR-HE) can provide evidence about the cost-effectiveness of an intervention within a limited time frame. They are valuable (1) to inform the development of an own economic model, (2) to identify the most relevant studies for a particular decision, and (3) to identify the implicated economic trade-offs [ 3 ]. Moreover, provided that high-quality economic evaluations that exist are sufficiently transferable and demonstrate similar results regarding cost-effectiveness, SR-HE might indicate the most cost-effective intervention.

Jefferson et al. [ 4 ] found that SR-HE show fundamental methodological flaws, especially regarding their search strategy and the application of an appropriate quality assessment tool. Nevertheless, little research has been performed to further develop the methods for SR-HE in the meantime. Standards for the preparation of SR-HE do not seem to exist so far: More recent studies focusing on the available methodological guidelines found that the recommendations still vary widely and are partly imprecise [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. It is therefore to be expected that the conduct of SR-HE still varies widely and still shows methodological shortcomings. The aim of this paper is

To provide a detailed overview of the characteristics and applied methods in recently published SR-HE

To identify similarities and differences between the characteristics and methods of SR-HE

To identify common challenges

Methods/Design

We used the PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) 2015 checklist to develop the methods for this systematic review protocol [ 9 ] (please see Additional file 1 ).

Should protocol amendments be necessary, these will be documented including details of the date, changes made, and the rationale for changes.

Literature search

A systematic search in Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily, and Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present will be performed. We will limit the publication date of our search to the period 2015/01/01 to present. A validated search filter for economic evaluations (Emory University [Grady] [ 10 ]) will be combined with a validated filter for the retrieval of systematic reviews (Lee [ 11 ]), as presented in Table 1 . This strategy was chosen as it provides an optimal balance between sensitivity and precision. Search results will be downloaded to EndNote version X7 where duplicates will be identified and removed.

Inclusion criteria

We will include articles available as full-text and written in English, German, French, or Spanish if they fulfill all of the following criteria:

Systematic literature search in at least one electronic database and transparent description of study selection. We will exclude articles applying abbreviated review methods (e.g., scoping reviews and short reviews) as judged by the authors of the SR-HE.

Inclusion of full economic evaluations (i.e., cost-effectiveness/cost-utility/cost-benefit-analyses [ 12 ]) and/or the cost-effectiveness of an intervention was reviewed. Articles reviewing solely partial economic evaluations (like cost-of-illness studies or budget impact analyses) will be excluded.

Objective to answer a cost-effectiveness research question, i.e., we will exclude articles focusing exclusively on methodological aspects (e.g., analysis of methods applied in health economic modeling studies).

Full-text journal article. Protocols, commentaries, editorials, and conference proceedings will be excluded. Likewise, secondary publications of HTA reports will be excluded as the focus of our study will be on the scientific literature instead of documents stemming from regulatory processes within a certain jurisdiction in a health care system.

Study selection

Two reviewers will independently assess the titles and abstracts retrieved in the electronic literature search against the inclusion criteria. Possible eligible full-text articles will be retrieved and screened by two reviewers to reach a final decision about inclusion. Any disagreements will be resolved through discussion or involvement of a third reviewer.

We will prepare a PRISMA flowchart to illustrate the selection process.

Data abstraction

Methodological features will be extracted in a standardized, beforehand piloted data extraction form (Table 2 ). We developed an electronical extraction form in Microsoft Excel 2010 for a previous study (not published yet) in which we analyzed HTA reports of international HTA organizations for the methods applied for SR-HE and adapted it for the purpose of the present study. This approach for data abstraction and data presentation was inspired by the publication of Page et al. [ 13 ] which provides an overview of epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews of biomedical research. Data items presented in the included articles will be classified according to the categories depicted in Table 3 . Data will be extracted each by a single reviewer. After extraction of the first articles, a 10% random sample will be verified for accuracy and correctness of data entries by a second reviewer. Discrepancies will be resolved through discussion or third party, if necessary. In case of frequent and/or substantial disagreements, a verification of 100% is intended.

Data analysis and presentation

We will analyze all data using Microsoft Excel 2010. Results for each data item extracted will be presented in tables. For nominal data, we will provide numbers and percentages. We will provide median and ranges for ordinal data.

In order to allow an estimation of the number of SR-HE published per year and to analyze possible changes over time, we will present the number of hits resulting from our search strategy for the years 2015 to 2017.

Since no tool for the critical appraisal of SR-HE exists (comparable e.g., to AMSTAR [A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews] [ 14 ]), we will not critically appraise included articles by means of a certain tool but focus on similarities, differences, and methodological shortcomings.

As far as possible, the results of our study will be reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [ 15 ].

Abbreviations

A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Patient, intervention, comparison, outcome, setting

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis

Prospective Register of Systematic reviews

Systematic reviews of health economic evaluations

European Commission. Inception impact assessment—strengthening of the EU cooperation on. Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/roadmaps/docs/2016_sante_144_health_technology_assessments_en.pdf . Accessed April 19, 2017

OECD. Fiscal sustainability of health systems: bridging health and finance perspectives. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2015.

Google Scholar

Anderson R. Systematic reviews of economic evaluations: utility or futility? Health Econ. 2010 Mar;19(3):350–64.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Jefferson T, Demicheli V, Vale L. Quality of systematic reviews of economic evaluations in health care. JAMA. 2002 Jun 5;287(21):2809–12.

Mathes T, Walgenbach M, Antoine SL, et al. Methods for systematic reviews of health economic evaluations: a systematic review, comparison, and synthesis of method literature. Med Decis Mak. 2014 Oct;34(7):826–40.

Article Google Scholar

Thielen FW, Van Mastrigt G, Burgers LT, et al. How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for clinical practice guidelines: database selection and search strategy development (part 2/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016 Dec;16(6):705–21.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

van Mastrigt GA, Hiligsmann M, Arts JJ, et al. How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions: a five-step approach (part 1/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016 Dec;16(6):689–704.

Wijnen B, Van Mastrigt G, Redekop WK, et al. How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions: data extraction, risk of bias, and transferability (part 3/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016 Dec;16(6):723–32.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015 Jan 02;349:g7647.

Glanville J, Fleetwood K, Yellowlees A, et al. Development and testing of search filters to identify economic evaluations in MEDLINE and EMBASE. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2009.

Lee E, Dobbins M, Decorby K, et al. An optimal search filter for retrieving systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012 Apr 18;12:51.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Page MJ, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews of biomedical research: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2016 May;13(5):e1002028.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007 Feb 15;7:10.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. w64

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

No funding will be received for the proposed study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department Health Care and Health Economics, Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), Im Mediapark 8, 50670, Cologne, Germany

Miriam Luhnen

Faculty of Health, Department of Medicine, Witten/Herdecke University, Ostmerheimer Str. 200, Haus 38, 51109, Cologne, Germany

Institute for Research in Operative Medicine, Witten/Herdecke University, Ostmerheimer Str. 200, Haus 38, 51109, Cologne, Germany

Barbara Prediger & Tim Mathes

Faculty of Health, Brandenburg Medical School – Theodor Fontane, Campus Neuruppin, Fehrbelliner Str. 38, 16816, Neuruppin, Germany

Edmund A. M. Neugebauer

Interdisciplinary Centre for Health Services Research, Witten/Herdecke University, Alfred-Herrhausen-Straße 50, 58448, Witten, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ML and TM developed and piloted the data extraction form. ML developed the search strategy for the proposed systematic review and drafted the manuscript. TM and BP commented on the manuscript. EAMN supported the conceptualization of the systematic review. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tim Mathes .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 checklist: recommended items to address in a systematic review protocol. (DOCX 36 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Luhnen, M., Prediger, B., Neugebauer, E.A.M. et al. Systematic reviews of health economic evaluations: a protocol for a systematic review of characteristics and methods applied. Syst Rev 6 , 238 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0639-8

Download citation

Received : 05 May 2017

Accepted : 23 November 2017

Published : 02 December 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0639-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Systematic review

- Economic evaluation

- Reimbursement

- Medical decision making

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Systematic reviews of health economic evaluations: a protocol for a systematic review of characteristics and methods applied

Affiliations.

- 1 Department Health Care and Health Economics, Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), Im Mediapark 8, 50670, Cologne, Germany.

- 2 Faculty of Health, Department of Medicine, Witten/Herdecke University, Ostmerheimer Str. 200, Haus 38, 51109, Cologne, Germany.

- 3 Institute for Research in Operative Medicine, Witten/Herdecke University, Ostmerheimer Str. 200, Haus 38, 51109, Cologne, Germany.

- 4 Faculty of Health, Brandenburg Medical School - Theodor Fontane, Campus Neuruppin, Fehrbelliner Str. 38, 16816, Neuruppin, Germany.

- 5 Interdisciplinary Centre for Health Services Research, Witten/Herdecke University, Alfred-Herrhausen-Straße 50, 58448, Witten, Germany.

- 6 Institute for Research in Operative Medicine, Witten/Herdecke University, Ostmerheimer Str. 200, Haus 38, 51109, Cologne, Germany. [email protected].

- PMID: 29197411

- PMCID: PMC5712099

- DOI: 10.1186/s13643-017-0639-8

Background: The number of systematic reviews of economic evaluations is steadily increasing. This is probably related to the continuing pressure on health budgets worldwide which makes an efficient resource allocation increasingly crucial. In particular in recent years, the introduction of several high-cost interventions presents enormous challenges regarding universal accessibility and sustainability of health care systems. An increasing number of health authorities, inter alia, feel the need for analyzing economic evidence. Economic evidence might effectively be generated by means of systematic reviews. Nevertheless, no standard methods seem to exist for their preparation so far. The objective of this study was to analyze the methods applied for systematic reviews of health economic evaluations (SR-HE) with a focus on the identification of common challenges.

Methods/design: The planned study is a systematic review of the characteristics and methods actually applied in SR-HE. We will combine validated search filters developed for the retrieval of economic evaluations and systematic reviews to identify relevant studies in MEDLINE (via Ovid, 2015-present). To be eligible for inclusion, studies have to conduct a systematic review of full economic evaluations. Articles focusing exclusively on methodological aspects and secondary publications of health technology assessment (HTA) reports will be excluded. Two reviewers will independently assess titles and abstracts and then full-texts of studies for eligibility. Methodological features will be extracted in a standardized, beforehand piloted data extraction form. Data will be summarized with descriptive statistical measures and systematically analyzed focusing on differences/similarities and methodological weaknesses.

Discussion: The systematic review will provide a detailed overview of characteristics of SR-HE and the applied methods. Differences and methodological shortcomings will be detected and their implications will be discussed. The findings of our study can improve the recommendations on the preparation of SR-HE. This can increase the acceptance and usefulness of systematic reviews in health economics for researchers and medical decision makers.

Systematic review registration: The review will not be registered with PROSPERO as it does not meet the eligibility criterion of dealing with clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Economic evaluation; Medical decision making; Reimbursement; Systematic review.

- Cost-Benefit Analysis*

- Delivery of Health Care

- Economics, Medical*

- Review Literature as Topic*

- Systematic Reviews as Topic

- Technology Assessment, Biomedical

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 24 October 2013

Public health economics: a systematic review of guidance for the economic evaluation of public health interventions and discussion of key methodological issues

- Rhiannon Tudor Edwards 1 ,

- Joanna Mary Charles 1 &

- Huw Lloyd-Williams 1

BMC Public Health volume 13 , Article number: 1001 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

37k Accesses

83 Citations

31 Altmetric

Metrics details

If Public Health is the science and art of how society collectively aims to improve health, and reduce inequalities in health, then Public Health Economics is the science and art of supporting decision making as to how society can use its available resources to best meet these objectives and minimise opportunity cost. A systematic review of published guidance for the economic evaluation of public health interventions within this broad public policy paradigm was conducted.

Electronic databases and organisation websites were searched using a 22 year time horizon (1990–2012). References of papers were hand searched for additional papers for inclusion. Government reports or peer-reviewed published papers were included if they; referred to the methods of economic evaluation of public health interventions, identified key challenges of conducting economic evaluations of public health interventions or made recommendations for conducting economic evaluations of public health interventions. Guidance was divided into three categories UK guidance, international guidance and observations or guidance provided by individual commentators in the field of public health economics. An assessment of the theoretical frameworks underpinning the guidance was made and served as a rationale for categorising the papers.

We identified 5 international guidance documents, 7 UK guidance documents and 4 documents by individual commentators. The papers reviewed identify the main methodological challenges that face analysts when conducting such evaluations. There is a consensus within the guidance that wider social and environmental costs and benefits should be looked at due to the complex nature of public health. This was reflected in the theoretical underpinning as the majority of guidance was categorised as extra-welfarist.

Conclusions

In this novel review we argue that health economics may have come full circle from its roots in broad public policy economics. We may find it useful to think in this broader paradigm with respect to public health economics. We offer a 12 point checklist to support government, NHS commissioners and individual health economists in their consideration of economic evaluation methodology with respect to the additional challenges of applying health economics to public health.

Peer Review reports

We live in an unequal world and know that inequalities in health and lifetime opportunity are fundamentally linked to inequalities in income. A paradox is emerging–in order to affect health gain in those groups of society that face most socioeconomic challenges, we must trade off our more familiar, if implicit, Western goal of health gain maximisation. In the UK the principle of health gain maximisation underpins the technical appraisal approach taken by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE), [ 1 ]. NICE updated its “Guide to the methods of technology appraisal” in 2013 [ 2 ]. The updated version does not appropriate directly to public health; however, the guide maintains its position from the previous version with regards to economic evaluations. The use of cost-effectiveness, especially cost-utility analysis is preferred [ 2 ]. Cost per Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) estimates are favoured and appraised in accordance with the £20,000-30,000 threshold [ 2 ]. This is justified by the institute’s focus on maximising health gains [ 2 ]. In health economics, three papers have begun to shape thinking about public health economics. Kelly et al. [ 3 ] set out additional challenges of applying tools of economic evaluation to public health interventions as compared with the evaluation of clinical interventions. These challenges span multiple versus single outcomes, the effect of individual behaviour change upon the successful uptake of interventions, the difficulty in establishing cause and effect due to the multi-faceted nature of public health interventions and the high level of social variation involved in public health interventions. Weatherly et al. [ 4 ] offered additional considerations that health economists should build into their evaluations of public health interventions. These considerations being the need for other approaches due to the limited availability of randomised controlled trials, measurement of a range of outcomes beyond Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs), consideration of inter-sectoral costs and consequences which may include wider benefits and spill over effects, and a focus on equity. Payne et al. [ 5 ], introduced the idea of some public health interventions having the characteristics of “complex” interventions, and the subsequent need to measure a much broader range of outcomes than focus on QALYs, suggesting that capability theory may offer one way forward as a means for better capturing such wider benefits [ 6 ]. These three papers focus on, and critique, the traditional toolbox of methods of economic evaluation applied to the evaluation of Public Health interventions [ 7 ]. Looking back, in the UK, Derek Wanless challenged health economists to apply their methods of economic evaluation in a public health setting [ 8 ]. More recently, the NICE Centre for Public Health Excellence has called for health economists to think more broadly about how economics as a parent discipline in its widest sense, can help support those responsible for resource allocation decisions in Public Health. This was taken forward in a Medical Research Council (MRC) Population Health Sciences Research Network (PHSRN) funded workshop on population health economics in Glasgow, May 2012. Though consensus seems to be from the authors above, that the QALY is inadequate in a public health setting; Owen et al. [ 9 ] provide a powerful message that many public health interventions are indeed cost-effective, well below the NICE threshold of £20,000-30,000 per QALY. We observe a growing interest and expectation that public health interventions should be “cost saving” [ 10 ], hence an interest by government, local government and the NHS in return on investment analysis as an alternative to cost-effectiveness analysis [ 11 ].

However, economic evaluations of public health economics are not without challenges; therefore, there is a need of guidance in this field. To examine what guidance currently exists in the field of economic evaluations of public health economics we conducted a systematic review of UK guidance, international guidance and searched for papers offering observations from key commentators of the economic evaluation of public health interventions.

Literature search

We followed a PRISMA [ 12 ] approach to reporting the findings of the systematic review of published guidance for the economic evaluation of public health interventions.

PubMed, MedLine, CRD database, EconLit were searched between September and October 2012 for published guidance of economic evaluation methods for public health interventions. In addition, The Medical Research Council, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, World Health Organisation and World Bank websites were also searched for relevant guidance and reference lists of published reviews were scrutinized (e.g. Owen et al. [ 9 ]).

Databases were searched for literature for the period 1990–2012. It was deemed appropriate to narrow the search to this time period as we wanted to include the more recent contributions and the studies found did not generally refer to articles before 1990. We restricted our search to papers published in the English language. Searches were conducted in October 2012.

The search terms used were: public health, public health economics, guidance for economic/econometric evaluation of public health interventions, challenges of public health economics, methods of public health economics, world health organisation, and health economics [see Additional file 1 ].

Study selection

The following exclusion and inclusion criteria were employed during the searches.

Papers were included if:

The paper had a reference in the title and/or abstract to the methods of economic evaluation of public health interventions.

The paper identified key challenges of conducting economic evaluations of public health interventions.

The paper made recommendations for conducting economic evaluations of public health interventions.

The paper was from a national source (e.g. Government or Advisory Group policy documents and reports) or published in a peer-review journal.

Papers were excluded if;

They were not specifically related to the economic evaluation of public health interventions.

They did not provide guidance on the economic evaluation of public health interventions.

They were published in a language other than English.

Papers identified by the searches were screened by reading the abstracts. Articles that matched the inclusion criteria above were obtained and read by RTE, JMC and HLW. It was also necessary to search literature by hand e.g., lists of references of guidance meeting the inclusion criteria. Information was extracted from each paper on the challenges and recommendations of methods to employ when conducting economic evaluations of public health interventions. We wanted to look as widely as possible at relevant health economics specific and public policy guidance on the evaluation of public health interventions.

Data collection process

We developed a summary of guidance and key observations, providing the following information; author, publication date, source of published guidance (e.g., UK or International) and key points. As this review was undertaken in a public policy context with reports the more prominent type of published guidance the authors were unable to adhere to PICO guidelines, instead we provided a summary.

Results will be presented as a narrative review as the search strategy aims to identify UK and international guidance and observations from key commentators. Therefore, results are likely to contain a high level of heterogeneity, which may not permit meta-analysis.

Assessment of theoretical underpinning

To strengthen the narrative review an assessment will be made of the theoretical underpinning of the included guidance. The theoretical paradigms will be categorised based upon whether they related to a macro/micro [ 13 ], welfarist/extra welfarist [ 14 ], capabilities [ 15 ] or behavioural economics approach [ 16 ]. These theoretical underpinnings will serve as a rationale or framework for categorising the papers. It must be noted however that no specific mention was made in the guidance as to its theoretical basis, but rather it is a judgment that we the authors have made. The first paradigm delineates between macro and micro economics. It is suggested that if a set of guidance relates to the evaluation of individual programmes then it belongs in a micro framework [ 13 ]. Otherwise if the guidance looks at outcomes on a population, whole economy level then a macro framework would apply [ 13 ]. Research on macroeconomic modelling uses information fed into general equilibrium models which connect health expenditure growth to its impact on the overall economy [ 17 ]. Health impact assessments conducted by the World Bank can be said to have a strong macro basis. Further a differentiation is made based on whether the theoretical underpinnings of the guidance relates to welfarist or extra-welfarist theory. Welfarism relates to the assumption that it is a measure of utility that’s important when measuring health, that is the utility received from the consumption of healthcare goods and services relative to other goods and services [ 14 ]. It is based on individualism and consequentialism [ 18 ]. Cost-benefit analysis is a good example of a welfarist perspective [ 19 ]. Extra-welfarism on the other hand goes beyond the study of utility and takes health itself and other non-utility measures as the unit of outcome [ 14 ]. Extra-welfarism is based on the underlying idea that rational choice and utility maximising behaviour, the underpinnings of welfarist theory are irrelevant to health behaviours [ 18 ]. Health is the maxim and not welfare. The EQ-5D [ 20 ] and concurrent measurement of QALYs provide a good example of extra-welfarist thinking). The third type of theoretical basis for guidance is the capability approach. Capabilities, according to Sen [ 15 ], are concerned with the ability to achieve functionings such as attachment, role, enjoyment, security and control. Ill health does not reduce quality of life on its own but insofar as it reduces the ability to achieve, for example, independence [ 21 ]. We assess the guidance based upon whether or not it promotes the capability approach [ 15 ] in a robust way, as an alternative to the QALY approach [ 5 ]. Finally, an underlying theory based on behavioural economics studies the behavioural aspects of economic agents and how this affects their decision making [ 16 ]. Behavioural economics does not suggest a rejection of the neoclassical approach to economics, but does advocate the psychological underpinnings of economic analysis. In this way it is argued that the assumptions that underlie theory are adapted to reflect a more realistic view of the world. Here we assess whether or not the guidance is based in behavioural economic theory.

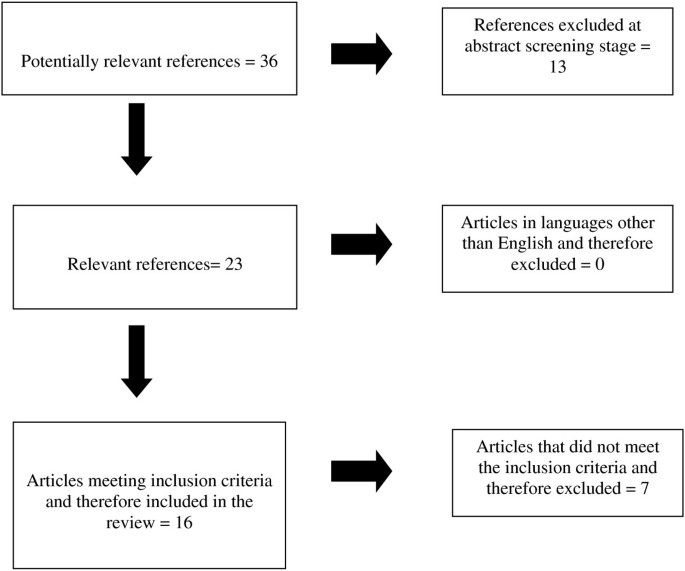

The initial database search provided a total of 36 citations. 36 remained after removing duplicates. Of these, 13 were excluded based upon their executive summary or abstract as they did not meet the criteria. Of the remaining 23, a total of 16 papers met the inclusion criteria (See Figure 1 ).

Flowchart outlining paper selection process for the systematic review.