More U.S. Hospitals Offering Gender-Affirming Surgeries

A boon is underway at medical institutions from coast to coast, aimed at helping transgender Americans who suffer gender dysphoria because of the mismatch between their bodies and their gender identity.

Gender-transition services and surgeries are becoming more widely available across the nation, and more insurance companies are adding coverage to help the more than one million Americans who identify as transgender.

“Access to these treatments is lifesaving for many transgender people,” said Kate Kendell, executive director at the National Center for Lesbian Rights, one of the nation’s strongest legal advocates for LGBTQ Americans. “The recent sea change among insurers and state Medicaid programs is long overdue, and we must be vigilant about protecting and expanding these protections.”

“Half of the respondents to the 2011 National Transgender Discrimination Survey said they had to educate their health care providers on how to treat them appropriately,” Mara Keisling, executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE), told NBC OUT. “Too few providers are sufficiently trained in how to treat transgender patients, and even fewer have the expertise to offer critical transition-related services. It is heartening that an increasing number of medical institutions and providers are learning about the importance of competency around transgender issues and transition-related procedures.”

The Cleveland Clinic, Boston Medical Center, Oregon Health and Science University in Portland and Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City are among the latest medical centers to provide gender-affirming procedures.

“At Mount Sinai, we are offering the full array of services for transgender people regardless of whether they have already accomplished their transition,” Zil Goldstein, a nurse practitioner and program director at Mount Sinai’s Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery , told NBC OUT. “We want people to know that these treatments are available, and also that our staff are prepared to serve and care for the transgender community with sensitivity.”

This month an institution with a controversial history regarding transgender health care added its name to the list: Johns Hopkins Medicine. Johns Hopkins made history in 1965 as the first academic institution to offer gender-affirming surgeries, but it stopped in 1979 and never resumed. However, in a letter posted earlier this month , it reaffirmed its "commitment to the LGBT community” and announced it will resume gender-reassignment surgeries in 2017.

“We have committed to and will soon begin providing gender-affirming surgery as another important element of our overall care program, reflecting careful consideration over the past year of best practices and the appropriate provision of care for transgender individuals," the letter stated.

Even though not every transgender individual seeks or qualifies for surgery -- because of personal reasons, their health or insurance coverage -- demand is high. The increase in services has ramped-up since 2014, when the U.S. government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services started covering transgender-related procedures, which have been indelicately called “sex change operations.” A more common name is sex reassignment surgery, or SRS, and a more popular name within the trans community is gender confirmation surgery, or GCS.

"Despite the recent improvements in institutions offering these lifesaving transgender health services, there is still an unmet need for compassionate and comprehensive care,” Goldstein told NBC News.

“This is life-affirming and, in many cases, lifesaving treatment that is recognized as medically necessary by the medical profession,” Jillian Weiss, executive director of the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund , said. “It is crucial that we have a cadre of medical professionals across the county and around the world who have the training and experience to provide health care to the millions of transgender people who require it."

Right now, 12 states and the District of Columbia offer Medicaid programs covering transition-related care, according to the NCTE. But that leaves 38 states with none.

“No one should be denied medically necessary care because of who they are, and yet, that has been the reality for most transgender people for decades,” Kendell of NCLR told NBC OUT. “These positive changes are long overdue, and they are already under attack by anti-LGBT groups. We must be vigilant about defending and protecting them.”

Dawn Ennis is an award-winning journalist who was the first to transition in a network TV newsroom. She is now a freelance writer, producer and editor, as well as a widow, a single parent of three children, and the subject of an award-winning documentary, Before Dawn/After Don . Ennis is also on YouTube , on Twitter and blogging at lifeafterdawn.com

Follow NBC OUT on Twitter , Facebook and Instagram .

The Go-To Guide to Gender Surgeons

Find a qualified surgeon for gender-affirming care.

Start Your Search

Find a Surgeon

Search by U.S. State, Procedure and Insurance Search by Country and Procedure Browse the Global Surgeon Maps

The Go-To Guide To Gender Surgeons

- Quick Links

- Make An Appointment

- Our Services

- Price Estimate

- Price Transparency

- Pay Your Bill

- Patient Experience

- Careers at UH

Schedule an appointment today

Gender Affirmation Surgery and Compassionate Care for Individuals with Gender Dysphoria

Gender dysphoria is a medical term used to describe a condition in which a person’s gender identity – an internal and innate sense of oneself as being male or female – is incompatible with the external sexual characteristics present at birth. For example, a person born with female genitals who feels essentially male in every other way and identifies with that gender; or a person born with male genitals, yet feels essentially female in every other way and identifies with that gender. Both may be said to have gender dysphoria – a state of mind that can lead to depression, social anxiety, social isolation and a general state of emotional distress.

In recent years, recognition and acceptance of gender dysphoria as a legitimate diagnosis has spurred efforts in the medical community to offer compassionate support along with medical and surgical options to help people reconcile their outward appearance and sexual functioning with their internal self-perceptions.

A diagnosis of gender dysphoria is made by a healthcare provider after a thorough and careful evaluation has been done by a team of medical and psychological professionals. The next steps will depend on the individual’s goals and expectations.

What Is Gender Affirmation Surgery?

Any surgical procedure designed to align a person’s internal sense of self with their external physical and sexual characteristics is known as gender affirmation surgery. This is sometimes called gender confirmation surgery as well. Older terms such as gender reassignment or sex reassignment surgery have fallen out of favor.

While some may opt for hormone therapy only, for some transgender, transsexual or gender non-conforming patients it is medically and psychologically necessary to change their physical body to reduce gender dysphoria and improve their quality of life.

Some individuals may choose to undergo “top surgery” to alter their anatomy to be more in-line with their gender identity – male to female transgender individuals (transfemales or transwomen) may take female hormones to promote breast development with or without breast implants. Furthermore, some transwomen undergo facial feminization, Adam’s Apple reduction, or vocal cord surgery as well. Female to male transgender individuals (transmen or transmales) may have their breasts surgically removed (bilateral mastectomy) in addition to taking male hormones to increase muscle mass, lower their tone of voice and promote the growth of body and facial hair.

Genital Gender Affirmation Surgeries

Some people will choose to complete their transition with genital gender affirmation surgery or “bottom surgery” – a surgical procedure (or procedures) by which the genital organs are altered to physically resemble and function like those that are associated with their identified gender. Prior to genital gender affirmation surgery, patients must have been on hormones for at least a year while living consistently as the gender to which they are transitioning.

UH reconstructive urologist, Shubham Gupta, MD, FACS offers male to female and female to male genital reconstruction surgeries, including:

- Vaginoplasty (male to female)

- Phalloplasty and metoidioplasty (female to male)

Eligibility Requirements for Gender Affirmation Surgery

All gender transition surgeries result in permanent, physical transformation so patients must meet certain eligibility requirements before proceeding. To be eligible, patients must:

- Be of legal age (age 18 in the United States)

- Complete 12 months of continuous hormone therapy (HT)

- Successfully complete 12 months of living full-time as the gender with which they identify

- Undergo a mental health assessment and participate in psychotherapy

- Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the surgeries (including cost), potential complications, recovery and rehabilitation.

The Region’s Only Comprehensive Program

Gender transition surgeries require the expertise of multiple specialists, including reconstructive urologists, plastic surgeons and otolaryngologists (ENT) to achieve optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes. The surgeons at University Hospitals work as a team to offer patients a wide variety of procedures to help them complete their gender transition journey.

University Hospitals is the only health system in the region to offer these complex and highly specialized gender affirmation surgeries that are not widely available in the United States. As a result, thousands of individuals now have access to these life-changing services that have the potential to improve their quality of life and decrease depression and social anxiety.

- ACS Foundation

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- ACS Archives

- Careers at ACS

- Federal Legislation

- State Legislation

- Regulatory Issues

- Get Involved

- SurgeonsPAC

- About ACS Quality Programs

- Accreditation & Verification Programs

- Data & Registries

- Standards & Staging

- Membership & Community

- Practice Management

- Professional Growth

- News & Publications

- Information for Patients and Family

- Preparing for Your Surgery

- Recovering from Your Surgery

- Jobs for Surgeons

- Become a Member

- Media Center

Our top priority is providing value to members. Your Member Services team is here to ensure you maximize your ACS member benefits, participate in College activities, and engage with your ACS colleagues. It's all here.

- Membership Benefits

- Find a Surgeon

- Find a Hospital or Facility

- Quality Programs

- Education Programs

- Member Benefits

- The rise and fall of gende...

The rise and fall of gender identity clinics in the 1960s and 1970s

Editor’s note: this article is based on the second-place poster in the american college of surgeons history of surgery poster contest at the virtual clinical congress 2020. the authors note that as the field of medicine and society have evolved to better understand the experiences of transgender individuals, terminology has changed significantly. the authors have […].

Melanie Fritz, Nat Mulkey

April 1, 2021

Editor’s note: This article is based on the second-place poster in the American College of Surgeons History of Surgery poster contest at the virtual Clinical Congress 2020. The authors note that as the field of medicine and society have evolved to better understand the experiences of transgender individuals, terminology has changed significantly. The authors have kept the original wording of direct quotes, but elsewhere in the article terminology is used that is consistent with present-day standards; that is, “transgender” or “transgender and gender nonbinary.”

HIGHLIGHTS Summarizes early pioneering work in the GAS field in the U.S. and Europe Describes the effects of clinic closures in the 1970s Outlines the resurgence of multidisciplinary clinics for TGNB patients at academic centers and in private practice Identifies ongoing barriers related to GAS, including financial concerns and access to reliable information

Transgender and gender nonbinary (TGNB) individuals have existed for thousands of years and in cultures throughout the world. In Western medicine, however, the modern era of gender-affirming surgery (GAS) began at the Institute of Sexual Research in Berlin, Germany, under the leadership of Magnus Hirschfeld, MD. Surgeons at the institute performed the earliest vaginal constructions in the 1930s. Early patients included an employee of the facility, known by the last name of Dorchen, and the Danish painter Lili Elbe, whose story was depicted in the 2015 film The Danish Girl . 1

Around the same time that Dr. Hirschfeld’s institute began performing vaginoplasties, the father of plastic surgery, Sir Harold Gillies, OBE, FRCS, had been refining techniques for genital construction in Britain. He did so primarily by operating on British men who had sustained genital injuries during wartime and subsequently presented to him for assistance. In the 1940s, he performed the first known phalloplasty for a transgender patient on Michael Dillon, MD, a British physician. Dr. Gillies later performed a vaginoplasty on patient Roberta Cowell, who gained some renown in Britain. 2

In the 1950s, Georges Burou, MD, began performing vaginoplasty operations in Casablanca, Morocco, and is widely credited with inventing the anteriorly pedicled penile skin flap inversion vaginoplasty. 3

Increased awareness in the U.S.

One of the earliest known GAS procedures performed in the U.S. was for patient Alan Hart, MD, a transgender man and physician, who underwent a hysterectomy in 1910. 1

The field of GAS subsequently remained dormant in the U.S. until the 1950s, when pioneers like Elmer Belt, MD, University of California Los Angeles, and Milton Edgerton, MD, Johns Hopkins University (JHU) began performing GAS. 4,5

The work of sexologist and endocrinologist Harry Benjamin, MD, in the 1950s and 1960s provided additional momentum to the field within the medical community. At the time, many psychiatrists and physicians believed that the correct approach to treating transgender patients was exclusively through psychoanalytic therapy aimed at altering the desire to live as a different gender. Dr. Benjamin is attributed with being one of the first physicians to challenge this notion.

In 1966, he published The Transsexual Phenomenon , which detailed the era’s approach to GAS. 4 Notably, this text includes far more detail about male-to-female (MTF) surgical operations, such as vaginoplasty, than female-to-male (FTM) operations, such as phalloplasty or metoidioplasty. At the time, transgender men were incorrectly believed to be less common than transgender women, and surgeons were reluctant to perform FTM GAS procedures. Based on writings from the era, some of this reluctance stemmed from uncertainty as to whether surgical techniques were capable of constructing a neophallus that would be satisfactory to the patient. 6

A boom of awareness of GAS within both the field of medicine and the larger U.S. public can primarily be attributed to one individual: Christine Jorgensen. Ms. Jorgensen was a transgender woman who captured the attention and interest of the general public after undergoing a series of operations for GAS in Denmark from 1951 to 1952. 4 Her coming out story and transition were covered extensively in popular media, appearing in the New York Daily News under the eye-catching headline “Ex-GI Becomes Blonde Beauty.” 7

Wave of clinics providing GAS

Publication of Dr. Benjamin’s book coincided with the public announcement of JHU Gender Identity Clinic in November 1966. 8 While several major academic centers had internally discussed the formation of research institutes to study the treatment of transgender patients since the early 1960s, the opening of the JHU clinic marked a transition from quiet deliberation to public recruitment for research on GAS. Initiatives quickly sprung up at many major universities and hospitals, marked by interdisciplinary collaboration between psychiatrists, urologists, plastic surgeons, gynecologists, and social workers. While estimates vary, the increase in U.S. patients who underwent GAS was dramatic, growing to more than 1,000 by the end of the 1970s from approximately 100 patients in 1969. 5,9

Producing positive results in a stigmatized field

Whereas GAS was a new endeavor for U.S. physicians, these clinics primarily operated as research programs. As a new field of practice, the physicians involved in the clinics faced significant skepticism from colleagues, such as psychiatrist Joost Meerloo, MD, who outlined his concerns in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 1967. Dr. Meerloo wrote, “Unwittingly, many a physician does not treat the disease as such but treats, rather, the fantasy a patient develops about his disease…I believe the surgical treatment of transsexual yearnings easily falls into this trap…. What about our medical responsibility and ethics? Do we have to collaborate with the sexual delusions of our patients?” 10

Understandably, physicians involved in these gender identity clinics described feeling pressure to demonstrate successful postoperative outcomes in order to justify their work. In the introduction to a published case series on GAS, Norman Fisk, MD, a psychiatrist at Stanford University, CA, wrote, “In our efforts we were preoccupied with obtaining good results. This preoccupation, we believed, would enable us to continue our work in an area where many professional colleagues had, and retain, serious doubts as to the validity of gender reorientation.” 11

In an attempt to obtain good results, these clinics often maintained rigorous selection criteria that excluded a number of patients. The evaluation process required that patients undergo hormone treatment and live for a set period of time as the gender to which they intended to transition. This period of time could extend up to five years depending on the clinic, imposing a significant burden on patients. As one patient, transgender man Mario Martino, stated, “One talks of a period of two to five years. I agree that people should be tested. I think that they should be tested in every way possible before being accepted as a candidate for treatment. However, one of the problems that people tend to forget is that a female with a 48-inch bust cannot pass as a male for one day, much less for one year or five years, no matter how much he tries.” 12

Individuals who were considered traditionally attractive and were expected to be easily perceived as a member of the other sex, as well as individuals who were heterosexual per their gender identity, were considered better surgical candidates. To demonstrate the scale of this selectivity, out of 2,000 applications sent to JHU within two years of opening, only 24 patients underwent an operation. 5,11,13

Though early studies were small, many did, in fact, demonstrate successful psychiatric outcomes. A report from Edgerton and colleagues in 1970 found that at one to two years postoperatively, of nine patients who underwent GAS, all were glad to have undergone surgery, had greater self-confidence, and held “a brighter outlook for their future.” 5 When considering the competing demands of producing positive outcomes and providing GAS to patients in need, it’s clear how physicians working in these clinics were confronted with challenges in their roles. They were advocates for a marginalized population, and yet they also functioned as gatekeepers for thousands of transgender patients desperate for surgery and who faced reinforced gender-based stereotypes as described earlier in the eligibility criteria.

Timeline and clinic closure

Toward the end of the 1970s, many centers closed their doors to new patients. These closures often were kept out of the public eye, making it difficult to discern precise timing or causes. There were, however, two notable exceptions to the pattern of patient enrollment quietly declining and ceasing.

At JHU, a new chair of psychiatry, Paul McHugh, MD, was hired in 1975. Dr. McHugh disapproved of offering GAS to transgender patients and acknowledged that from the moment he was hired, he intended to stop this practice at the clinic. Under his leadership, JHU psychiatrist Jon Meyer, MD, published a study of 50 surgical patients from the JHU clinic, which concluded that GAS offered “no objective benefit” for transgender people. Although this claim directly contradicted a growing body of evidence that found significant benefit for transgender patients, the publication sparked the rapid closure of the JHU clinic in 1979. 14

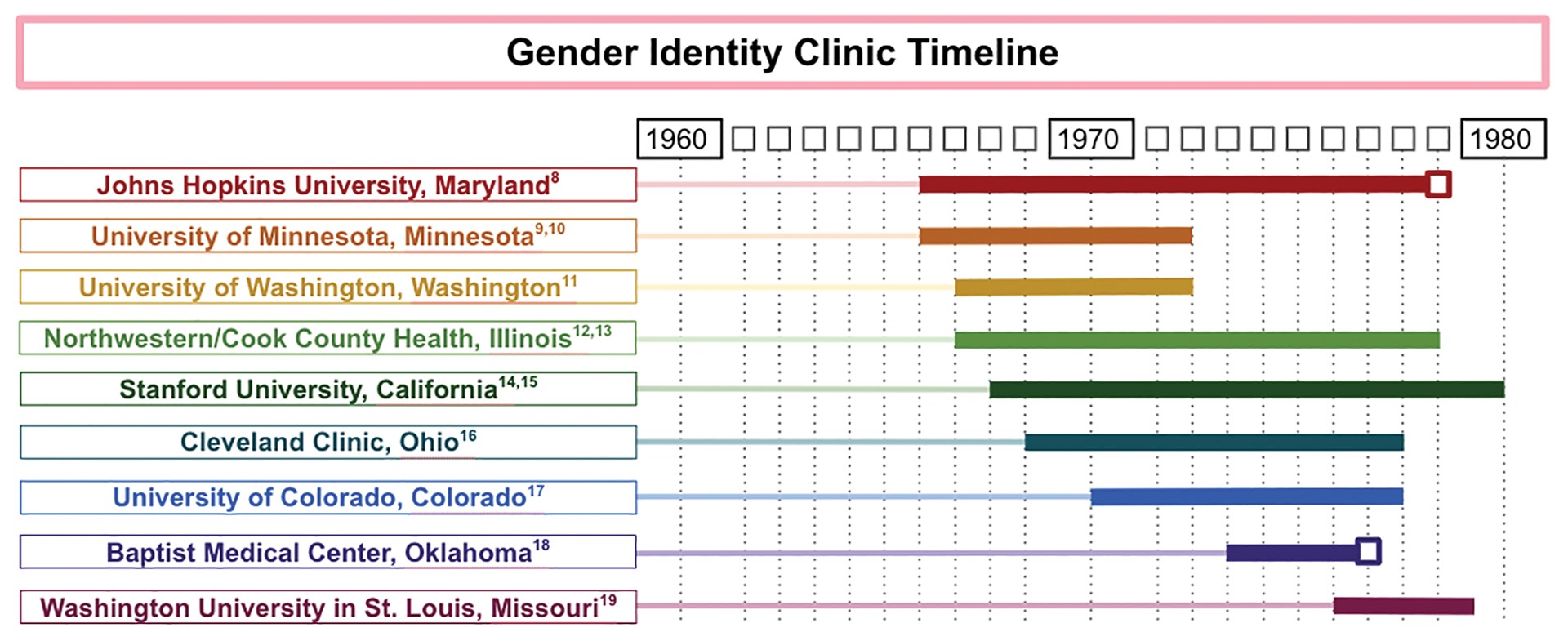

FIGURE 1. GENDER IDENTITY CLINIC TIMELINE

Another gender identity clinic where operations were abruptly terminated was the Baptist Medical Center in Oklahoma City. The Gender Identity Foundation at the center had offered a variety of services for transgender patients, including GAS, since 1973, under the radar of local religious leaders. In 1977, however, the issue of GAS was brought to the attention of the board of directors of the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma. The physicians involved fervently advocated to be allowed to continue their practice, including surgeons Charles L. Reynolds, Jr., MD, FACS, and David W. Foerster, MD, FACS, who issued a joint statement that said, “[I]f Jesus Christ were alive today, undoubtedly he would render help and comfort to the transsexual.” Despite these appeals, the board of directors voted 54–2 to ban GAS at the Baptist Medical Center. 15

Given the known timing of when these two clinics closed, they are marked with a box in a timeline constructed by the authors (see Figure 1). The remaining end dates are estimates derived from the latest reported operations in the medical literature and news articles, which likely underestimate the length of time the clinics were in operation. The reasons for closure of the remaining clinics appear to be multifactorial.

The publicity around the Meyer paper that led to JHU’s clinic closure may have played a role in the decision to close other clinics. 16 In addition, some clinics described financial challenges during this time, as patients often were unable to afford the expensive operations, and insurance companies refused to cover them. For example, at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, clinic, the first two dozen operations were funded by a research grant at the expense of the state, but a news article from 1972 suggests that funding difficulties were exacerbated when the state no longer wanted to fund the project. 9 Institutional pushback, such as that experienced at JHU, and the retirement of leading surgeons also may have played a role in the closure of gender identity clinics across the nation.

Even though many clinics’ GAS-related research was winding down in the late 1970s, the last 15 years of academic interest motivated the 1979 establishment of the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association. This organization, formed with the goal of organizing professionals who were “interested in the study and care of transexualism and gender dysphoria,” has since been renamed the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and has grown into an international interdisciplinary organization. 17 WPATH has established internationally accepted guidelines for treating individuals with gender dysphoria, which are periodically updated. The most recent of these guidelines is the Standards of Care Version 7 (SOC7). 18 Today, insurance companies, national payors, and treatment teams in both the U.S. and Europe use the WPATH SOC7 guidelines for establishing surgical eligibility.

Present day significance

The contemporaneous evolution of the first wave of gender identity clinics generated a rich field for refinement of surgical technique, as well as the assessment of postoperative outcomes, and produced a foundation of scientific literature demonstrating successful psychiatric outcomes for transgender people undergoing GAS. These milestones foreshadowed a resurgence of multidisciplinary clinics for TGNB individuals in academic centers and paved the way for private practitioners to specialize in GAS. For example, Stanley Biber, MD, a private practice surgeon in Colorado, performed more than 5,000 GAS operations during his 35 years in practice. 19

Many centers for transgender medicine and surgery now exist across the U.S., and the number of GAS operations being performed in the U.S. has increased substantially, along with expanded insurance coverage. In 2015, the U.S. Transgender Survey found that 25 percent of TGNB individuals had one or more gender-affirming operations. 20 Similar to the earlier wave of clinics, present-day clinics still are frequently composed of an interdisciplinary team of primary care, surgical, and mental health professionals.

Although the number of GAS continues to increase, the current discourse echoes earlier concerns about how to limit barriers for this marginalized population while prioritizing positive surgical outcomes. The WPATH standards of care often function as guides to assist health care centers in creating TGNB health programs. 21 The WPATH SOCs have evolved since their establishment and presently tend to include fewer preoperative requirements for TGNB patients than in the 1970s and 1980s.

However, TGNB patients continue to face significant barriers to accessing GAS. A 2018 survey of TGNB patients found that the most commonly cited barriers to gender-affirming care are financial concerns, access to physicians who are knowledgeable about GAS, and access to reliable information. 22 These financial concerns can be exacerbated by the cost of obtaining the mental health evaluations recommended by WPATH SOC7, and challenges associated with insurance coverage. 23 To address these barriers, institutions are considering preoperative models besides the WPATH SOC7 to potentially reduce challenges.

Moreover, general medical education initiatives are under way to increase provider knowledge about this population. 24,25 As the field of GAS continues to evolve in the present day, we look forward to seeing how the surgical and medical community partners with patients to minimize these barriers and promote access to these essential surgical treatments.

- Denny D. Gender reassignment surgeries in the XXth century. Workshop at 9th Transgender Lives: The Intersection of Health and Law Conference, Farmington, CT. May 10, 2015. Available at: http://dallasdenny.com/Writing/2015/05/10/gender-reassignment-surgeries-in-the-xxth-century-2015/ . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- Kennedy P. The First Man-Made Man: The Story of Two Sex Changes, One Love Affair, and a Twentieth-Century Medical Revolution . New York: Bloomsbury USA; 2007.

- Hage JJ, Kareem RB, Laub DR. On the origin of pedicled skin inversion vaginoplasty: Life and work of Dr. Georges Burou of Casablanca. Ann Plast Surg . 2007;59(6):723-729.

- Benjamin H. The Transsexual Phenomenon . New York, New York: Warner Books Incorporated; 1966.

- Edgerton MT, Knorr NJ, Callison JR. The surgical treatment of transsexual patients. Limitations and indications. Plast Reconstr Surg . 1970;45(1):38-46.

- Williams G. An approach to transsexual surgery. Nurs Times . 1973;69(25):787.

- Ex-GI becomes blonde beauty: Operations transform Bronx youth. New York Daily News . December 1, 1952:75. Available at: www.newspapers.com/clip/25375703/ex-gi-becomes-blonde-beauty/ . Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Buckley T. A changing of sex by surgery begun at Johns Hopkins. The New York Times . November 21, 1966. Available at: www.nytimes.com/1966/11/21/archives/a-changing-of-sex-by-surgery-begun-at-johns-hopkins-johns-hopkins.html . Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Brody J. 500 in the U.S. change sex in six years with surgery. The New York Times . Nov 20, 1972. Available at: www.nytimes.com/1972/11/20/archives/500-in-the-u-s-change-sex-in-six-years-with-surgery-500-change-sex.html . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- Meerloo JA. Change of sex and collaboration with the psychosis. Am J Psychiatry . 1967;124(2):263-264.

- Fisk NM. Five spectacular results. Arch Sex Behav . 1978;7(4):351-369.

- Money J. Transsexualism: Open forum. Arch Sex Behav . 1978;7(4):387-415.

- Hastings D, Markland C. Post-surgical adjustment of 25 transsexuals at University of Minnesota. Arch Sex Behav . 1978;7(4):327-336.

- Siotos C, Neira PM, Lau BD, et al. Origins of gender affirmation surgery: The history of the first gender identity clinic in the United States at Johns Hopkins. Ann Plast Surg . 2019;83(2):132-136.

- Baptists vote to ban sex change operations. Sarasota Herald-Tribune . October 15, 1977.

- Nutt AE. Long shadow cast by psychiatrist on transgender issues finally recedes at Johns Hopkins. Washington Post . April 5, 2017. Available at: www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/long-shadow-cast-by-psychiatrist-on-transgender-issues-finally-recedes-at-johns-hopkins/2017/04/05/e851e56e-0d85-11e7-ab07-07d9f521f6b5_story.html . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- Walker PA. The University of Texas Medical Branch. Memo to persons interested in the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association. April 17, 1979. Available at: www.wpath.org/media/cms/Documents/History/Harry%20Benjamin/First%20HBIGDA%20Membership%20Request%20Letter%201979.pdf . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend . 2012;13(4):165-232.

- Arrillaga P. Onetime coal mining town bolstered by changing economy. Los Angeles Times . June 4, 2000. Available at: www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2000-jun-04-me-37512-story.html . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Healthcare Equality, 2016. Available at: www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- National LGBT Health Education Center. Creating a transgender health program at your health center: Planning to implementation. September 2018. Available at: www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Creating-a-Transgender-Health-Program.pdf . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- El-Hadi H, Stone J, Temple-Oberle C, Harrop AR. Gender-affirming surgery for transgender individuals: Perceived satisfaction and barriers to care. Plast Surg . 2018;26(4):263-268.

- Puckett JA, Cleary P, Rossman K, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Barriers to gender-affirming care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Sex Res Social Policy . 2018;15(1):48-59.

- Lichtenstein M, Stein L, Connolly E, et al. The Mount Sinai patient-centered preoperative criteria meant to optimize outcomes are less of a barrier to care than WPATH SOC 7 criteria before transgender-specific surgery. Transgend Health . 2020;5(3):166-172.

- Streed CG, Davis JA. Improving clinical education and training on sexual and gender minority health. Curr Sex Health Rep . 2018;10:273-280.

Popular Services

- Patient & Visitor Guide

Committed to improving health and wellness in our Ohio communities.

Health equity, healthy community, classes and events, the world is changing. medicine is changing. we're leading the way., featured initiatives, helpful resources.

- Refer a Patient

Gender-Affirming Surgeries

What is gender-affirming surgery?

Gender-affirming surgeries change the look and function of your assigned sex to more closely match the gender you identify with. Having a gender-affirming surgery may be part of your journey to becoming more of your true self.

Surgical options for gender-affirmation include facial surgery, voice surgery, and top and bottom surgeries. Patients whose assigned sex and gender identity are different may experience gender dysphoria. Gender-affirming surgery is an important part of the management of patients with gender dysphoria.

Top surgery includes procedures to create or remove breasts. Feminizing bottom surgery includes procedures to remove the penis and testicles and create a new vagina, labia and clitoris. Learn more about feminizing bottom surgery .

Masculinizing bottom surgery includes procedures to remove the uterus or add a penis for intercourse and urinating or a small penis to urinate standing up. Learn more about masculinizing bottom surgery .

We follow the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s standards when performing gender-affirming surgeries. These guidelines are set for safe, effective physical and mental health care for transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Requirements for each procedure will vary.

Why choose Ohio State for gender-affirming surgery?

The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center is one of only a few academic health centers in the country to offer bottom gender-affirming surgery. We have a dedicated team of medical experts in every field, and through close collaboration aim to serve the LGBTQ population of Columbus and beyond.

Surgical options for gender-affirmation

- Facial surgery options

- Feminization surgery

- Masculinization surgery

- Meet our gender-affirming care surgical team Meet your surgical team

Helpful Links

- LGBTQ+ Employee Resource Group HealthBeat HUB Channel (Internal Access Only)

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Services

- Transgender Primary Care Clinic

- Ear, Nose and Throat Services

- Urology Services

Subscribe. Get just the right amount of health and wellness in your inbox.

- Credit cards

- View all credit cards

- Banking guide

- Loans guide

- Insurance guide

- Personal finance

- View all personal finance

- Small business

- Small business guide

- View all taxes

You’re our first priority. Every time.

We believe everyone should be able to make financial decisions with confidence. And while our site doesn’t feature every company or financial product available on the market, we’re proud that the guidance we offer, the information we provide and the tools we create are objective, independent, straightforward — and free.

So how do we make money? Our partners compensate us. This may influence which products we review and write about (and where those products appear on the site), but it in no way affects our recommendations or advice, which are grounded in thousands of hours of research. Our partners cannot pay us to guarantee favorable reviews of their products or services. Here is a list of our partners .

How Much Does Gender-Affirming Surgery Cost?

Many or all of the products featured here are from our partners who compensate us. This influences which products we write about and where and how the product appears on a page. However, this does not influence our evaluations. Our opinions are our own. Here is a list of our partners and here's how we make money .

Gender-affirming care encompasses a broad range of psychological, behavioral and medical treatments for transgender, nonbinary and gender-nonconforming people.

The care is designed to “support and affirm an individual’s gender identity” when it is at odds with the sex they were assigned at birth, as defined by the World Health Organization.

What is gender-affirming surgery?

Gender-affirming surgery refers to the surgical and cosmetic procedures that give transgender and nonbinary people “the physical appearance and functional abilities of the gender they know themselves to be,” according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. It is sometimes called gender reassignment surgery.

There are three main types of gender-affirming surgeries, per the Cleveland Clinic:

Top surgery , in which a surgeon either removes a person’s breast tissue for a more traditionally masculine appearance or shapes a person’s breast tissue for a more traditionally feminine appearance.

Bottom surgery , or the reconstruction of the genitals to better align with a person’s gender identity.

Facial feminization or masculinization surgery , in which the bones and soft tissue of a person’s face are transformed for either a more traditionally masculine or feminine appearance.

Some people who undergo gender-affirming surgeries also use specific hormone therapies. A trans woman or nonbinary person on feminizing hormone therapy, for example, takes estrogen that’s paired with a substance that blocks testosterone. And a trans man or nonbinary person on masculinizing hormone therapy takes testosterone.

Gender-affirming surgeries and treatments are the recommended course of treatment for gender dysphoria by the American Medical Association. Gender dysphoria is defined as “clinically significant distress or impairment related to gender incongruence, which may include desire to change primary and/or secondary sex characteristics,” according to the American Psychiatric Association.

Some LGBTQ+ advocates and medical professionals feel that gender dysphoria shouldn't be treated as a mental disorder, and worry that gender dysphoria’s inclusion in the DSM-5 — the authoritative source on recognized mental health disorders for the psychiatric industry — stigmatizes trans and nonbinary people.

How much does gender-affirming surgery cost?

Gender-affirming surgery can cost between $6,900 and $63,400 depending on the precise procedure, according to a 2022 study published in The Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics.

Out-of-pocket costs can vary dramatically, though, depending on whether you have insurance and whether your insurance company covers gender-affirming surgeries.

There are also costs associated with the surgery that may not be represented in these estimates. Additional costs may include:

Surgeons fees

Hospital fees

Consultation fees

Insurance copays

The cost of psychiatric care or therapy, as most insurance companies and surgeons require at least one referral letter prior to the surgery. An hour of therapy can cost between $65 and $250, according to Good Therapy, an online platform for therapists and counselors.

Time off work. After bottom surgery, you can expect to miss six weeks of work while recovering. Most people miss around two weeks of work after top surgery.

Miscellaneous goods that’ll help you recover. For example, after bottom surgery, you might need to invest in a shower stool, waterproof bed sheets, cheap underwear and sanitary towels. Top surgery patients may need, depending on the procedure, a mastectomy pillow, chest binder and baggy clothes.

Is gender-affirming surgery covered by insurance?

It’s illegal for any federally funded health insurance program to deny coverage on the basis of gender identity, sexual orientation or sexual characteristics, per Section 1557, a section of the Affordable Care Act. Section 1557 doesn’t apply to private insurance companies, though, and several U.S. states have passed laws banning gender-affirming care.

The following states have banned gender-affirming surgery for people under 18 years old, according to the Human Rights Campaign: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia. In four of these states — Alabama, Arkansas, Florida and Indiana — court injunctions are currently ensuring access to care.

And these states have either passed laws — or have governors who issued executive orders — protecting access to gender-affirming surgery, according to the Movement Advancement Project, a public policy nonprofit: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Vermont and Washington, D.C.

But even if your state has enshrined protections for gender-affirming care, some private insurance companies may consider surgeries “cosmetic” and therefore “not medically necessary,” according to the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund. If you have private insurance or are insured through your employer, contact your insurance company and see if they cover gender-affirming care. Also, ask about any documentation the insurance company requires for coverage.

The Williams Institute estimates that 14% of trans Americans currently enrolled in Medicaid live in states where such coverage is banned, while another 27% of trans Americans live in states where coverage is “uncertain,” because their state laws are “silent or unclear on coverage for gender-affirming care.”

Because of Section 1557, Medicaid is federally banned from denying coverage on the basis of sex or gender; among the roughly 1.3 million transgender Americans, around 276,000 have Medicaid coverage, according to a 2022 report from the Williams Institute.

How to pay for gender-affirming surgery

If your private insurance company won’t cover gender-affirming care, and you’re unable to obtain coverage through the federal marketplace, consider these sources:

Online personal loan.

Credit union personal loan.

Credit card.

CareCredit.

Home equity line of credit.

Family loan.

There are also several nonprofits that offer financial assistance for gender-affirmation surgeries. Those organizations include:

Point of Pride , which offers grants and scholarships to trans and nonbinary people seeking gender-affirming surgery and care.

The Jim Collins Foundation , which raises money to fund gender-affirming surgeries.

Genderbands , which offers grants for gender-affirming surgeries and care.

Black Transmen Inc. , which funds gender-affirming surgeries for Black trans men.

On a similar note...

Advancing and Transforming Health

- See us on instagram

- See us on twitter

Transgender Surgery

Stanford Medicine is proud to be a leader in providing gender-affirming surgery, including vaginoplasty and orchiectomy. Our team is specially trained to offer surgical and post-operative care for penile-inversion vaginoplasty and postoperative conditions including vaginal stenosis, pelvic floor disorders, and vaginal dilation issues.

Click here to learn more about vaginoplasty →

Click here to learn more about orchiectomy →

We work hand-in-hand with healthcare providers at the Stanford LGBTQ+ Health Program as well as a team of experts in pelvic floor physical therapy. We are committed to providing specialized and personalized care, and to research in these important areas.

We routinely collaborate with other specialists including coordination of other surgeries.

For a new appointment, please contact the LGBTQ+ Health Program to see Dr. Kavita Mishra at (650) 724-8844.

Our surgical and postoperative care team includes Dr. Kavita Mishra , a nurse practitioner, a registered nurse, 3 pelvic floor physical therapists, and a surgical coordinator. We work closely with your primary care and mental health providers before, during, and after surgery. We believe in multidisciplinary and supportive care to provide you with the best postoperative outcome.

Dr. Kavita Mishra is a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgeon who was the first graduate of Cleveland Clinic’s Transgender Surgery & Medicine fellowship program, training with Dr. Cecile Ferrando. Dr. Mishra attended Brown University for her undergraduate studies and the University of California, San Francisco, for medical school. She completed a four-year residency in obstetrics and gynecology at Brown University/Women & Infants Hospital. She then completed a three-year fellowship in Urogynecology (Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery) at Brown University, specializing in minimally invasive surgery and pelvic floor disorders. She practiced at the University of California, San Francisco, before joining the department at Stanford. Dr. Mishra is enthusiastic about connecting with her patients, supporting them in their journey, and educating the next generation of physician leaders.

Why Choose Stanford for Gender Affirming Surgery?

Our team believes that you and only you get to decide how your identity is expressed. We are experts in helping people meet their goals and specialize in care ranging from routine medical visits to the physical transition process. We have spent the last few years actively expanding surgical services at Stanford.

World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Guidelines

Our team follows the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) guidelines to ensure patients are appropriate surgical candidates. We require patients live full time as their self-affirmed gender for more than one year, that they have undergone cross-sex hormone therapy for at least one year (if appropriate), that they have letters of support for surgical transition from two mental health professionals who are well-versed in transgender patient care. Patients who have met these criteria are deemed appropriate surgical candidates. They cannot be smokers or be excessively overweight, and they must be medically optimized for surgery if they have medical comorbidities.

Click here to read additional information about WPATH guidelines.

Daniel A. Medalie, M.D.

Board certified plastic and cosmetic surgeon.

Transgender

Welcome! You have made the right choice in choosing Dr. Medalie for your Gender Confirming Surgery. If you would like to schedule an evaluation of your chest to determine what type of operation may be necessary, please e-mail front and side photos to Valerie at [email protected] . Before you contact her please download the history form , and send it along with the photos. She can also answer most of your logistical questions. Typical fees for “top surgery” are $7500-8500 (this includes anesthesia and facility fees and all post operative care).

All correspondence, forms and pictures should be scanned and e-mailed to Valerie at

[email protected]

Gender Reassignments

Gender reassignment surgery.

Please note that Dr. Bram Kaufman does not currently provide genital reassignment surgery. Bodily surgeries, including facial feminization surgery, are available. Please see our surgical gender reassignment surgeries below.

Gender reassignment procedure aims to alter the physiological appearance of the patient in accordance with the gender they identify with. This procedure may be performed on individuals who are either male, but have been identified as female, or female, who have been identified as male.

Gender reassignment surgery can help patients who may have less developed or fully developed breasts. It allows for a change of breasts from one gender to another, depending on the patient’s actual sexual orientation. Following a diagnosis, the patient will have to undergo a three stage treatment program, involving hormone therapy, real life test, and sex reassignment surgery.

Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy will involve androgen hormone delivery for biological females changing to male, and delivery of estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone blocking hormones for biological males changing to female. The therapy may continue for about 12 months, and is usually accompanied by a Real Life Test.

Patients may choose to receive cosmetic surgeries such as buttock and thigh lift, liposuction, and abdominoplasty.

Our practice is currently in the process of the developing a team to perform the “bottom” surgeries which will require collaboration between multiple departments such as gynecology, urology, plastic surgery and others. Cosmetic procedures we currently perform include breast augmentatio n, liposuction , rhinoplasty , facial bone construction, cheek implants, brow lift , lip augmentation , chin recontouring, jaw recontouring, and eyelid surgery .

Vocal cord surgery or voice training may also be a part of the elective procedures to accomplish an adequate gender transformation.

Impact of Hormone Therapy

With gender reassignment hormone therapy, biological males can expect breast growth, reduction of body hair and fat redistribution in certain areas. Biological females can expect an increase in body and facial hair, weight gain, heightened sexual appetite, and a heavier voice.

To learn more about cosmetic treatment and procedures or to schedule a consultation by Cleveland Ohio area plastic surgeon, Dr. Bram Kaufman , please contact us at 1-216-778-2245 or click here .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Research consistently shows that people who choose gender affirmation surgery experience reduced gender incongruence and improved quality of life. Depending on the procedure, 94% to 100% of people report satisfaction with their surgery results. Gender-affirming surgery provides long-term mental health benefits, too.

The Cleveland Clinic Transgender Surgery Program has also partnered with several community mental health practices and program in our area and our coordinator will be happy to provide you with a provider or practice referral should you need one outside of Cleveland Clinic. Location. Cleveland Clinic Main Campus 9500 Euclid Ave. Cleveland, Ohio ...

Gender-Affirming Surgery. Request an Appointment. Ohio: 216.445.6308 Florida: 877.463.2010. Why Choose Us Our Doctors Consultations Requirements Appointments Locations. Not everyone undergoing gender transition wants surgery, but if you do, finding the right care team is an important first step. Gender-affirming surgery can be life-changing ...

216.445.6308. Request an Appointment. See before and after photos of patients who have undergone gender-affirming surgeries at Cleveland Clinic, including breast augmentations, facial feminizations, mastectomies and vaginoplasty.

Clinical leaders: Gender reassignment surgeries require a high level of expertise. Cleveland Clinic Florida was the first academic medical center in Broward County to offer these complex procedures. You can rest assured that you're receiving the most up-to-date treatment from a team that trains new doctors in the latest approaches.

At Cleveland Clinic we offer routine medical care, tailored specifically to patients' needs, as well as transition-specific services, including mental health support and treatment, gender affirming hormone therapy and surveillance, as well as gender affirmation surgery. Our volume of patients increases each month, and with this growth, we ...

Cleveland Clinic's Center for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBTQ+) Care offers healthcare services at the Lakewood Family Health Center, 216.237.5500. Embedded in a primary care practice, the center provides care for all patients in a safe and welcoming environment. It includes providers who understand the health needs of LGBT ...

Andres Mascaro Pankova, MD, a surgeon in the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Cleveland Clinic Florida, ... While the new data did not significantly change the understanding of the success of gender reassignment vaginoplasty procedures, it will be important to continue to track results in order to better serve this patient ...

Perioperative Management of the Transgender Patient. Program helps meet a growing need. By Cecile Unger, MD, MPH. Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy. In 2016, eight genital surgeries for transgender women ...

Case Report: Robot-Assisted Revision Surgery for a Transgender Woman. Post-op dilation regimen can be a challenge for long-term success. A 54-year-old transgender woman presented at Cleveland Clinic with vaginal stenosis. She was seeking surgical revision after complications from gender affirmation surgeries performed at other care centers ...

The Cleveland Clinic, ... A more common name is sex reassignment surgery, or SRS, and a more popular name within the trans community is gender confirmation surgery, or GCS.

He is the Medical Director of the Gender Affirmation Surgery Program at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. Dr. Schechter has been performing gender-affirming surgeries for more than 20 years. Since 2013, he has performed approximately 100-150 gender-affirming procedures every year. He offers the full spectrum of gender-affirming procedures.

This is sometimes called gender confirmation surgery as well. Older terms such as gender reassignment or sex reassignment surgery have fallen out of favor. While some may opt for hormone therapy only, for some transgender, transsexual or gender non-conforming patients it is medically and psychologically necessary to change their physical body ...

Arch Sex Behav. 1978;7(4):387-415. Hastings D, Markland C. Post-surgical adjustment of 25 transsexuals at University of Minnesota. Arch Sex Behav. 1978;7(4):327-336. Siotos C, Neira PM, Lau BD, et al. Origins of gender affirmation surgery: The history of the first gender identity clinic in the United States at Johns Hopkins.

Tag: gender reassignment. November 29, ... Hormone Therapy and Contraceptive Surgery in Transgender Men. Know the myths and pitfalls before prescribing. Back Page 1 of 1 Next. Advertisement. Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. ... Cleveland Clinic

Transgender men may choose to initiate testosterone therapy to help make their physical appearance concordant with their gender identity. However, they are often mistaken about the contraceptive properties of testosterone. "Some transgender men have male partners and engage in penile-vaginal intercourse. They may believe that testosterone is ...

Yes. Anyone who has a prostate, including transgender women and nonbinary people assigned male at birth, can get prostate cancer. Even if you've had some type of gender-affirming genital surgery ...

Gender-affirming surgery is an important part of the management of patients with gender dysphoria. Top surgery includes procedures to create or remove breasts. Feminizing bottom surgery includes procedures to remove the penis and testicles and create a new vagina, labia and clitoris. Learn more about feminizing bottom surgery .

Gender-affirming surgery can cost between $6,900 and $63,400 depending on the precise procedure, according to a 2022 study published in The Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. Out-of-pocket costs ...

Dr. Kavita Mishra is a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgeon who was the first graduate of Cleveland Clinic's Transgender Surgery & Medicine fellowship program, training with Dr. Cecile Ferrando. Dr. Mishra attended Brown University for her undergraduate studies and the University of California, San Francisco, for medical school.

Typical fees for "top surgery" are $7500-8500 (this includes anesthesia and facility fees and all post operative care). All correspondence, forms and pictures should be scanned and e-mailed to Valerie at. [email protected]. Transgender Surgery Cleveland OH - Daniel A. Medalie, M.D. specializes in Transgender Surgery.

CLEVELAND -- The Cleveland VA Medical Center opened the country's first VA clinic, specifically designed to the healthcare needs of transgender veterans. Known as the "GIVE Clinic" for Gender ...

Gender Reassignment Surgery. Please note that Dr. Bram Kaufman does not currently provide genital reassignment surgery. Bodily surgeries, including facial feminization surgery, are available. ... Cleveland, OH 44109 Cedar Brainard Building 29001 Cedar Road #518 Lyndhurst, Ohio 44124 3609 Park East Drive North Building #206 ...