What is Theme? A Look at 20 Common Themes in Literature

Sean Glatch | May 7, 2024 | 18 Comments

When someone asks you “What is this book about?” , there are a few ways you can answer. There’s “ plot ,” which refers to the literal events in the book, and there’s “character,” which refers to the people in the book and the struggles they overcome. Finally, there are themes in literature that correspond with the work’s topic and message. But what is theme in literature?

The theme of a story or poem refers to the deeper meaning of that story or poem. All works of literature contend with certain complex ideas, and theme is how a story or poem approaches these ideas.

There are countless ways to approach the theme of a story or poem, so let’s take a look at some theme examples and a list of themes in literature. We’ll discuss the differences between theme and other devices, like theme vs moral and theme vs topic. Finally, we’ll examine why theme is so essential to any work of literature, including to your own writing.

But first, what is theme? Let’s explore what theme is—and what theme isn’t.

Common Themes in Literature: Contents

- Theme Definition

20 Common Themes in Literature

- Theme Examples

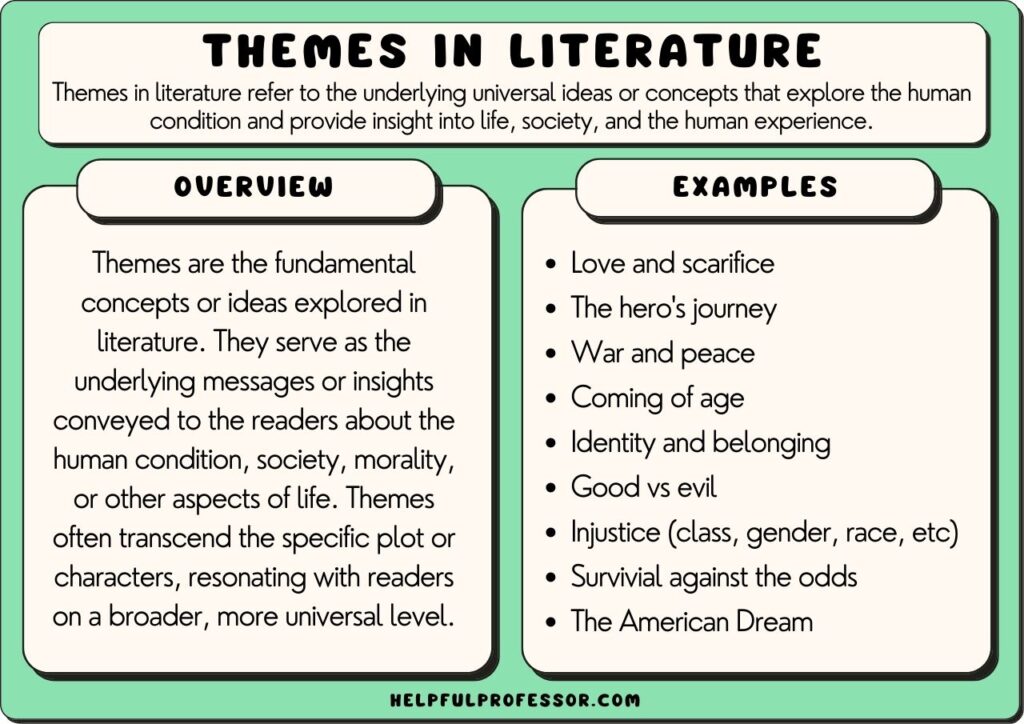

Themes in Literature: A Hierarchy of Ideas

Why themes in literature matter.

- Should I Decide the Themes of a Story in Advance?

Theme Definition: What is Theme?

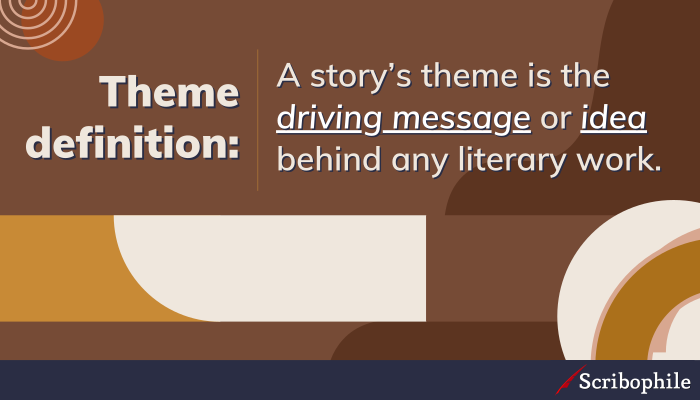

Theme describes the central idea(s) that a piece of writing explores. Rather than stating this theme directly, the author will look at theme using the set of literary tools at their disposal. The theme of a story or poem will be explored through elements like characters , plot, settings , conflict, and even word choice and literary devices .

Theme definition: the central idea(s) that a piece of writing explores.

That said, theme is more than just an idea. It is also the work’s specific vantage point on that idea. In other words, a theme is an idea plus an opinion: it is the author’s specific views regarding the central ideas of the work.

All works of literature have these central ideas and opinions, even if those ideas and opinions aren’t immediate to the reader.

Justice, for example, is a literary theme that shows up in a lot of classical works. To Kill a Mockingbird contends with racial justice, especially at a time when the U.S. justice system was exceedingly stacked against African Americans. How can a nation call itself just when justice is used as a weapon?

By contrast, the play Hamlet is about the son of a recently-executed king. Hamlet seeks justice for his father and vows to kill Claudius—his father’s killer—but routinely encounters the paradox of revenge. Can justice really be found through more bloodshed?

What is theme? An idea + an opinion.

Clearly, these two works contend with justice in unrelated ways. All themes in literature are broad and open-ended, allowing writers to explore their own ideas about these complex topics.

Let’s look at some common themes in literature. The ideas presented within this list of themes in literature show up in novels, memoirs, poems, and stories throughout history.

Theme Examples in Literature

Let’s take a closer look at how writers approach and execute theme. Themes in literature are conveyed throughout the work, so while you might not have read the books in the following theme examples, we’ve provided plot synopses and other relevant details where necessary. We analyze the following:

- Power and Corruption in the novel Animal Farm

- Loneliness in the short story “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”

- Love in the poem “How Do I Love Thee”

Theme Examples: Power and Corruption in the Novel Animal Farm

At its simplest, the novel Animal Farm by George Orwell is an allegory that represents the rise and moral decline of Communism in Russia. Specifically, the novel uncovers how power corrupts the leaders of populist uprisings, turning philosophical ideals into authoritarian regimes.

Most of the characters in Animal Farm represent key figures during and after the Russian Revolution. On an ailing farm that’s run by the negligent farmer Mr. Jones (Tsar Nicholas II), the livestock are ready to seize control of the land. The livestock’s discontent is ripened by Old Major (Karl Marx/Lenin), who advocates for the overthrow of the ruling elite and the seizure of private land for public benefit.

After Old Major dies, the pigs Napoleon (Joseph Stalin) and Snowball (Leon Trotsky) stage a revolt. Mr. Jones is chased off the land, which parallels the Russian Revolution in 1917. The pigs then instill “Animalism”—a system of government that advocates for the rights of the common animal. At the core of this philosophy is the idea that “all animals are equal”—an ideal that, briefly, every animal upholds.

Initially, the Animalist Revolution brings peace and prosperity to the farm. Every animal is well-fed, learns how to read, and works for the betterment of the community. However, when Snowball starts implementing a plan to build a windmill, Napoleon drives Snowball off of the farm, effectively assuming leadership over the whole farm. (In real life, Stalin forced Trotsky into exile, and Trotsky spent the rest of his life critiquing the Stalin regime until he was assassinated in 1940.)

Napoleon’s leadership quickly devolves into demagoguery, demonstrating the corrupting influence of power and the ways that ideology can breed authoritarianism. Napoleon uses Snowball as a scapegoat for whenever the farm has a setback, while using Squealer (Vyacheslav Molotov) as his private informant and public orator.

Eventually, Napoleon changes the tenets of Animalism, starts walking on two legs, and acquires other traits and characteristics of humans. At the end of the novel, and after several more conflicts , purges, and rule changes, the livestock can no longer tell the difference between the pigs and humans.

Themes in Literature: Power and Corruption in Animal Farm

So, how does Animal Farm explore the theme of “Power and Corruption”? Let’s analyze a few key elements of the novel.

Plot: The novel’s major plot points each relate to power struggles among the livestock. First, the livestock wrest control of the farm from Mr. Jones; then, Napoleon ostracizes Snowball and turns him into a scapegoat. By seizing leadership of the farm for himself, Napoleon grants himself massive power over the land, abusing this power for his own benefit. His leadership brings about purges, rule changes, and the return of inequality among the livestock, while Napoleon himself starts to look more and more like a human—in other words, he resembles the demagoguery of Mr. Jones and the abuse that preceded the Animalist revolution.

Thus, each plot point revolves around power and how power is wielded by corrupt leadership. At its center, the novel warns the reader of unchecked power, and how corrupt leaders will create echo chambers and private militaries in order to preserve that power.

Characters: The novel’s characters reinforce this message of power by resembling real life events. Most of these characters represent real life figures from the Russian Revolution, including the ideologies behind that revolution. By creating an allegory around Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, and the other leading figures of Communist Russia’s rise and fall, the novel reminds us that unchecked power foments disaster in the real world.

Literary Devices: There are a few key literary devices that support the theme of Power and Corruption. First, the novel itself is a “satirical allegory.” “ Satire ” means that the novel is ridiculing the behaviors of certain people—namely Stalin, who instilled far-more-dangerous laws and abuses that created further inequality in Russia/the U.S.S.R. While Lenin and Trotsky had admirable goals for the Russian nation, Stalin is, quite literally, a pig.

Meanwhile, “allegory” means that the story bears symbolic resemblance to real life, often to teach a moral. The characters and events in this story resemble the Russian Revolution and its aftermath, with the purpose of warning the reader about unchecked power.

Finally, an important literary device in Animal Farm is symbolism . When Napoleon (Stalin) begins to resemble a human, the novel suggests that he has become as evil and negligent as Mr. Jones (Tsar Nicholas II). Since the Russian Revolution was a rejection of the Russian monarchy, equating Stalin to the monarchy reinforces the corrupting influence of power, and the need to elect moral individuals to posts of national leadership.

Theme Examples: Loneliness in “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”

Ernest Hemingway’s short story “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” is concerned with the theme of loneliness. You can read this short story here . Content warning for mentions of suicide.

There are very few plot points in Hemingway’s story, so most of the story’s theme is expressed through dialogue and description. In the story, an old man stays up late drinking at a cafe. The old man has no wife—only a niece that stays with him—and he attempted suicide the previous week. Two waiters observe him: a younger waiter wants the old man to leave so they can close the cafe, while an older waiter sympathizes with the old man. None of these characters have names.

The younger waiter kicks out the old man and closes the cafe. The older waiter walks to a different cafe and ruminates on the importance of “a clean, well-lighted place” like the cafe he works at.

Themes in Literature: Loneliness in “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”

Hemingway doesn’t tell us what to think about the old man’s loneliness, but he does provide two opposing viewpoints through the dialogue of the waiters.

The younger waiter has the hallmarks of a happy life: youth, confidence, and a wife to come home to. While he acknowledges that the old man is unhappy, he also admits “I don’t want to look at him,” complaining that the old man has “no regard for those who must work.” The younger waiter “did not wish to be unjust,” he simply wanted to return home.

The older waiter doesn’t have the privilege of turning away: like the old man, he has a house but not a home to return to, and he knows that someone may need the comfort of “a clean and pleasant cafe.”

The older waiter, like Hemingway, empathizes with the plight of the old man. When your place of rest isn’t a home, the world can feel like a prison, so having access to a space that counteracts this feeling is crucial. What kind of a place is that? The older waiter surmises that “the light of course” matters, but the place must be “clean and pleasant” too. Additionally, the place should not have music or be a bar: it must let you preserve the quiet dignity of yourself.

Lastly, the older waiter’s musings about God clue the reader into his shared loneliness with the old man. In a stream of consciousness, the older waiter recites traditional Christian prayers with “nada” in place of “God,” “Father,” “Heaven,” and other symbols of divinity. A bartender describes the waiter as “otro locos mas” (translation: another crazy), and the waiter concludes that his plight must be insomnia.

This belies the irony of loneliness: only the lonely recognize it. The older waiter lacks confidence, youth, and belief in a greater good. He recognizes these traits in the old man, as they both share a need for a clean, well-lighted place long after most people fall asleep. Yet, the younger waiter and the bartender don’t recognize these traits as loneliness, just the ramblings and shortcomings of crazy people.

Does loneliness beget craziness? Perhaps. But to call the waiter and old man crazy would dismiss their feelings and experiences, further deepening their loneliness.

Loneliness is only mentioned once in the story, when the young waiter says “He’s [the old man] lonely. I’m not lonely. I have a wife waiting in bed for me.” Nonetheless, loneliness consumes this short story and its older characters, revealing a plight that, ironically, only the lonely understand.

Theme Examples: Love in the Poem “How Do I Love Thee”

Let’s turn towards brighter themes in literature: namely, love in poetry . Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem “ How Do I Love Thee ” is all about the theme of love.

Themes in Literature: Love in “How Do I Love Thee”

Browning’s poem is a sonnet , which is a 14-line poem that often centers around love and relationships. Sonnets have different requirements depending on their form, but between lines 6-8, they all have a volta —a surprising line that twists and expands the poem’s meaning.

Let’s analyze three things related to the poem’s theme: its word choice, its use of simile and metaphor , and its volta.

Word Choice: Take a look at the words used to describe love. What do those words mean? What are their connotations? Here’s a brief list: “soul,” “ideal grace,” “quiet need,” “sun and candle-light,” “strive for right,” “passion,” “childhood’s faith,” “the breath, smiles, tears, of all my life,” “God,” “love thee better after death.”

These words and phrases all bear positive connotations, and many of them evoke images of warmth, safety, and the hearth. Even phrases that are morose, such as “lost saints” and “death,” are used as contrasts to further highlight the speaker’s wholehearted rejoicing of love. This word choice suggests an endless, benevolent, holistic, all-consuming love.

Simile and Metaphor: Similes and metaphors are comparison statements, and the poem routinely compares love to different objects and ideas. Here’s a list of those comparisons:

The speaker loves thee:

- To the depths of her soul.

- By sun and candle light—by day and night.

- As men strive to do the right thing (freely).

- As men turn from praise (purely).

- With the passion of both grief and faith.

- With the breath, smiles, and tears of her entire life.

- Now in life, and perhaps even more after death.

The speaker’s love seems to have infinite reach, flooding every aspect of her life. It consumes her soul, her everyday activities, her every emotion, her sense of justice and humility, and perhaps her afterlife, too. For the speaker, this love is not just an emotion, an activity, or an ideology: it’s her existence.

Volta: The volta of a sonnet occurs in the poem’s center. In this case, the volta is the lines “I love thee freely, as men strive for right. / I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.”

What surprising, unexpected comparisons! To the speaker, love is freedom and the search for a greater good; it is also as pure as humility. By comparing love to other concepts, the speaker reinforces the fact that love isn’t just an ideology, it’s an ideal that she strives for in every word, thought, and action.

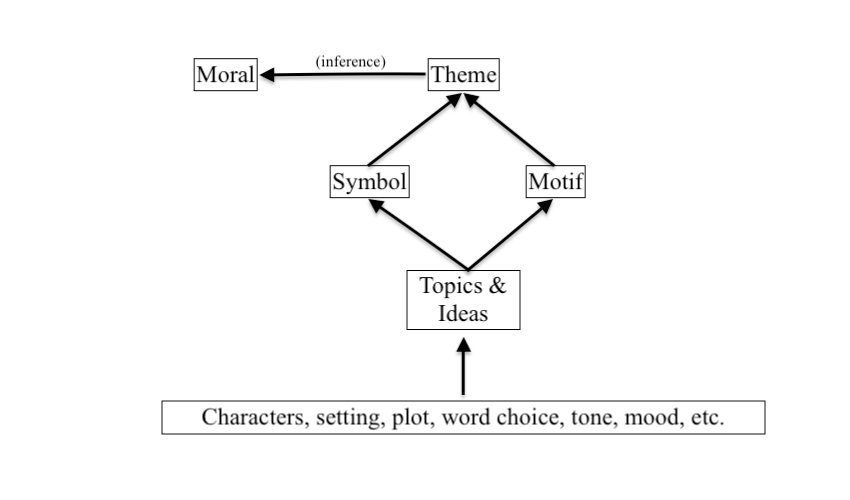

“Theme” is part of a broader hierarchy of ideas. While the theme of a story encompasses its central ideas, the writer also expresses these ideas through different devices.

You may have heard of some of these devices: motif, moral, topic, etc. What is motif vs theme? What is theme vs moral? These ideas interact with each other in different ways, which we’ve mapped out below.

Theme vs Topic

The “topic” of a piece of literature answers the question: What is this piece about? In other words, “topic” is what actually happens in the story or poem.

You’ll find a lot of overlap between topic and theme examples. Love, for instance, is both the topic and the theme of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem “How Do I Love Thee.”

The difference between theme vs topic is: topic describes the surface level content matter of the piece, whereas theme encompasses the work’s apparent argument about the topic.

Topic describes the surface level content matter of the piece, whereas theme encompasses the work’s apparent argument about the topic.

So, the topic of Browning’s poem is love, while the theme is the speaker’s belief that her love is endless, pure, and all-consuming.

Additionally, the topic of a piece of literature is definitive, whereas the theme of a story or poem is interpretive. Every reader can agree on the topic, but many readers will have different interpretations of the theme. If the theme weren’t open-ended, it would simply be a topic.

Theme vs Motif

A motif is an idea that occurs throughout a literary work. Think of the motif as a facet of the theme: it explains, expands, and contributes to themes in literature. Motif develops a central idea without being the central idea itself .

Motif develops a central idea without being the central idea itself.

In Animal Farm , for example, we encounter motif when Napoleon the pig starts walking like a human. This represents the corrupting force of power, because Napoleon has become as much of a despot as Mr. Jones, the previous owner of the farm. Napoleon’s anthropomorphization is not the only example of power and corruption, but it is a compelling motif about the dangers of unchecked power.

Theme vs Moral

The moral of a story refers to the story’s message or takeaway. What can we learn from thinking about a specific piece of literature?

The moral is interpreted from the theme of a story or poem. Like theme, there is no single correct interpretation of a story’s moral: the reader is left to decide how to interpret the story’s meaning and message.

For example, in Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place,” the theme is loneliness, but the moral isn’t quite so clear—that’s for the reader to decide. My interpretation is that we should be much more sympathetic towards the lonely, since loneliness is a quiet affliction that many lonely people cannot express.

Great literature does not tell us what to think, it gives us stories to think about.

However, my interpretation could be miles away from yours, and that’s wonderful! Great literature does not tell us what to think, it gives us stories to think about, and the more we discuss our thoughts and interpretations, the more we learn from each other.

The theme of a story affects everything else: the decisions that characters make, the mood that words and images build, the moral that readers interpret, etc. Recognizing how writers utilize various themes in literature will help you craft stronger, more nuanced works of prose and poetry .

“To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme.” —Herman Melville

Whether a writer consciously or unconsciously decides the themes of their work, theme in literature acts as an organizing principle for the work as a whole. For writers, theme is especially useful to think about in the process of revision: if some element of your poem or story doesn’t point towards a central idea, it’s a sign that the work is not yet finished.

Moreover, literary themes give the work stakes . They make the work stand for something. Remember that our theme definition is an idea plus an opinion. Without that opinion element, a work of literature simply won’t stand for anything, because it is presenting ideas in the abstract without giving you something to react to. The theme of a story or poem is never just “love” or “justice,” it’s the author’s particular spin and insight on those themes. This is what makes a work of literature compelling or evocative. Without theme, literature has no center of gravity, and all the words and characters and plot points are just floating in the ether.

Should I Decide the Theme of a Story or Poem in Advance?

You can, though of course it depends on the actual story you want to tell. Some writers certainly start with a theme. You might decide you want to write a story about themes like love, family, justice, gender roles, the environment, or the pursuit of revenge.

From there, you can build everything else: plot points, characters, conflicts, etc. Examining themes in literature can help you generate some strong story ideas !

Nonetheless, theme is not the only way to approach a creative writing project. Some writers start with plot, others with character, others with conflicts, and still others with just a vague notion of what the story might be about. You might not even realize the themes in your work until after you finish writing it.

You certainly want your work to have a message, but deciding what that message is in advance might actually hinder your writing process. Many writers use their poems and stories as opportunities to explore tough questions, or to arrive at a deeper insight on a topic. In other words, you can start your work with ideas, and even opinions on those ideas, but don’t try to shoehorn a story or poem into your literary themes. Let the work explore those themes. If you can surprise yourself or learn something new from the writing process, your readers will certainly be moved as well.

So, experiment with ideas and try different ways of writing. You don’t have think about the theme of a story right away—but definitely give it some thought when you start revising your work!

Develop Great Themes at Writers.com

As writers, it’s hard to know how our work will be viewed and interpreted. Writing in a community can help. Whether you join our Facebook group or enroll in one of our upcoming courses , we have the tools and resources to sharpen your writing.

Sean Glatch

18 comments.

Sean Glatch,Thank you very much for your discussion on themes. It was enlightening and brought clarity to an abstract and sometimes difficult concept to explain and illustrate. The sample stories and poem were appreciated too as they are familiar to me. High School Language Arts Teacher

Hi Stephanie, I’m so glad this was helpful! Happy teaching 🙂

Wow!!! This is the best resource on the subject of themes that I have ever encountered and read on the internet. I just bookmarked it and plan to use it as a resource for my teaching. Thank you very much for publishing this valuable resource.

Hi Marisol,

Thank you for the kind words! I’m glad to hear this article will be a useful resource. Happy teaching!

Warmest, Sean

builders beams bristol

What is Theme? A Look at 20 Common Themes in Literature | writers.com

Hello! This is a very informative resource. Thank you for sharing.

farrow and ball pigeon

This presentation is excellent and of great educational value. I will employ it already in my thesis research studies.

John Never before communicated with you!

Brilliant! Thank you.

[…] THE MOST COMMON THEMES IN LITERATURE […]

marvellous. thumbs up

Thank you. Very useful information.

found everything in themes. thanks. so much

In college I avoided writing classes and even quit a class that would focus on ‘Huck Finn’ for the entire semester. My idea of hell. However, I’ve been reading and learning from the writers.com articles, and I want to especially thank Sean Glatch who writes in a way that is useful to aspiring writers like myself.

You are very welcome, Anne! I’m glad that these resources have been useful on your writing journey.

Thank you very much for this clear and very easy to understand teaching resources.

Hello there. I have a particular question.

Can you describe the exact difference of theme, issue and subject?

I get confused about these.

I love how helpful this is i will tell my class about it!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

200 Common Themes in Literature

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is the theme of a story, common themes in literature, universal themes in literature, full list of themes in literature, theme examples in popular novels.

The theme of a novel is the main point of the story and what it’s really about. As a writer, it’s important to identify the theme of your story before you write it.

Themes are not unique to each novel because a theme addresses a common feeling or experience your readers can relate to. If you’re aware of what the common themes are, you’ll have a good idea of what your readers are expecting from your novel .

In this article, we’ll explain what a theme is, and we’ll explore common themes in literature.

The theme of a story is the underlying message or central idea the writer is trying to show through the actions of the main characters. A theme is usually something the reader can relate to, such as love, death, and power.

Your story can have more than one theme, as it might have core themes and minor themes that become more apparent later in the story. A romance novel can have the central theme of love, but the protagonist might have to overcome some self-esteem issues, which present the theme of identity.

Themes are great for adding conflict to your story because each theme presents different issues you could use to develop your characters. For example, a novel with the theme of survival will show the main character facing tough decisions about their own will to survive, potentially at the detriment of someone else they care about.

Sometimes a secondary character will represent the theme in the way they are characterized and the actions they take. Their role is to challenge the protagonist to learn what the story is trying to say about the theme. For example, in a novel about the fear of failure, the antagonist might be a rival in a competition who challenges the protagonist to overcome their fear so they can succeed against them.

It’s important to remember that a theme is not the same as a story’s moral message. A moral is a specific lesson you can teach your readers, whereas a story’s theme is an idea or concept your readers interpret in a way that relates to them.

Write like a bestselling author

Love writing? ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of your stories.

Common literary themes are concepts and central ideas that are relatable to most readers. Therefore, it’s a good idea to use a common theme if you want your novel to appeal to a wide range of readers.

Here’s our list of common themes in literature:

Love : the theme of love appears in novels within many genres, as it can discuss the love of people, pets, objects, and life. Love is a complex concept, so there are still unique takes on this theme being published every day.

Death/Grief : the theme of death can focus on the concept of mortality or how death affects people and how everyone processes grief in their own way.

Power : there are many books in the speculative fiction genres that focus on the theme of power. For example, a fantasy story could center on a ruling family and their internal problems and external pressures, which makes it difficult for them to stay in power.

Faith : the common theme of faith appears in stories where the events test a character’s resolve or beliefs. The character could be religious or the story could be about a character’s faith in their own ability to succeed.

Beauty : the theme of beauty is good for highlighting places where beauty is mostly overlooked by society, such as inner beauty or hard work that goes unnoticed. Some novels also use the theme of beauty to show how much we take beauty for granted.

Survival : we can see the theme of survival in many genres, such as horror, thriller, and dystopian, where the book is about characters who have to survive life-threatening situations.

Identity : there are so many novels that focus on the common theme of identity because it’s something that matters to a lot of readers. Everyone wants to know who they are and where they fit in the world.

Family : the theme of family is popular because families are ripe with opportunities for conflict. The theme of family affects everyone, whether they have one or not, so it’s a relatable theme to use in your story.

Universal themes are simply concepts and ideas that almost all cultures and countries can understand and interpret. Therefore, a universal theme is great for books that are published in several languages.

If you want to write a story you can export to readers all over the world, aim to use a universal theme. The common themes mentioned previously are all universal literary themes, but there are several more you could choose for your story.

Here are some more universal literary themes:

Human nature

Self-awareness

Coming of age

Not all themes are universal or common, but that shouldn’t put you off from using them. If you believe there is something to be said about a particular theme, your book could be the one to say it.

Your book could become popular if the theme of your book addresses a current issue. For example, a theme of art is not as common as love, but in a time when AI developments are making people talk about how AI affects art, it’s a theme people will probably appreciate.

Here’s a full list of themes you can use in your writing:

Abuse of power

American dream

Celebration

Change versus tradition

Chaos and order

Circle of life

Climate change

Colonialism

Common sense

Communication

Companionship

Conservation

Convention and rebellion

Darkness and light

Disappointment

Disillusionment

Displacement

Empowerment

Everlasting love

Forbidden love

Forgiveness

Fulfillment

Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender rights

Good vs evil

Imagination

Immortality

Imperialism

Impossibility

Individuality

Inspiration

Manipulation

Materialism

Nationalism

Not giving up

Opportunity

Peer pressure

Perseverance

Personal development

Relationship

Self-discipline

Self-reliance

Self-preservation

Subjectivity

Surveillance

Totalitarianism

Unconditional love

Unrequited love

Unselfishness

Winning and losing

Working class struggles

If you’ve decided on a literary theme but you’re not sure how to present it in your novel, it’s a good idea to check out how other writers have incorporated it into their novels. We’ve found some examples of themes within popular novels that could help you get started.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Great Gatsby is famous for the theme of the American dream, but it also includes themes of gender, race, social class, and identity. We experience the themes of the novel through the eyes of the narrator, Nick Carraway, who gradually loses his optimism for the American dream as the narrative progresses.

Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

It’s well known that Shakespeare was a connoisseur of the theme of tragedy in his plays, and Romeo and Juliet certainly features tragedy. However, forbidden love and family are the main themes.

Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White

Charlotte’s Web is a classic children’s book that features the themes of death and mortality. From the beginning of the book, the main characters have to come to terms with their own mortality. Charlotte, the spider, does what she can to prevent the slaughter of Wilbur, the pig.

Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

George Orwell’s novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four , focuses on themes of totalitarianism, repression, censorship, and surveillance. The novel is famous for introducing the concept of Big Brother, which has become synonymous with the themes of surveillance and abuse of power.

A Game of Thrones by George R. R. Martin

The fantasy novel, A Game of Thrones , is popular for its complex storylines that present themes of family, power, love, and death. The novel has multiple points of view, which give an insight into how each main character experiences the multiple themes of the story.

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

The Hunger Games is a popular teen novel that focuses on themes of poverty, rebellion, survival, friendship, power, and social class. The novel highlights the horrifying consequences of rebellion, as the teenage competitors have to survive the Hunger Games pageant.

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

Wolf Hall features themes of power, family, faith, and a sense of duty. It’s a historical novel about the life of Oliver Cromwell and how he became the most powerful minister in King Henry VIII’s council.

As you can see, the literary theme of a novel is one of the most important parts, as it gives the reader an instant understanding of what the story is about. Your readers will connect with your novel if you have a theme that is relatable to them.

Some themes are more popular than others, but some gain popularity based on events that are happening in the world. It’s important to consider how relevant your literary theme is to your readers at the time you intend to publish your book.

We hope this list of common themes in literature will help you with your novel writing.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

25 Themes Examples (In Literature)

In literature, a theme is a central topic, subject, or message that the author is presenting for us to ponder.

It represents the underlying meaning or main idea that the writer explores in the book.

In my last article, I explored the six types of conflict in literature , and these represent six key literary themes as well:

- Man vs Nature

- Man vs Society

- Man vs Technology

- Man vs Self

- Man vs Destiny

But, of course, we can tease out many more themes in literature.

Themes can be as simple as love, friendship, or survival, or they can be more complex, such as the critique of societal norms, exploration of human mortality, or the struggle between individual desires and societal expectations. They often provoke thought and offer insight into the human condition.

So, in this article, I want to present 25 of them to you (which include some of those listed above, of course). For each theme, I hope to present you with an example within literature that you’ll likely be familiar with.

Themes Examples

1. love and sacrifice.

Love, as one of the most intense of human emotions, also features as a core theme in not only literature, but also music, film, and theater.

This theme can go in a variety of directions, but often examines the extent to which we will go in order to experience and maintain love (often at great personal cost), the way love makes us irrational or conduct extraordinary deeds of both good and evil, and of course, the experience of heartbreak.

Examples in Literature

Notable examples include “Romeo and Juliet” by William Shakespeare, where the two main characters sacrifice their lives for their love, and “The Gift of the Magi” by O. Henry, where a couple each sacrifice their most prized possessions to buy a gift for the other.

2. The Individual versus Society

The individual vs society theme – one of the six key types of conflict in literature – occurs when one person grapples with and stands up against established social norms, mores, and powers-that-be.

It may be just one person or a group who stands up against society. An example of the former is Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games who starts off as a solo fighter against a dystopian government, when no one else is willing. An example of the later is the group of children in Tomorrow When the War Began who form a band of friends standing up as a guerilla group against an occupying army.

“To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee is a strong example, with Atticus Finch standing up against societal racism. He is an outcast lawyer who is the only man willing to represent a Black man who is framed for a crime in a deeply racist town.

3. The Hero’s Journey

This theme, derived from Joseph Campbell’s monomyth theory, features characters undertaking great journeys or quests.

According to the monomyth theory, there is a common motif throughout stories – both historical and fabricated – that gain currency in the social imagination. In these theories, the journey sets out on an adventure, faces challenges that lead to a dramatic personal transformation for the better, and returns home anew.

A quintessential example of the hero’s journey can be seen in “The Lord of the Rings” by J.R.R. Tolkien, where Frodo sets out a shy hobbit having never left his shire. He goes on a journey where he develops self-belief and gains the respect of powerful people, before returning home.

4. Coming of Age

This theme, also known as the Bildungsroman, focuses on the growth and maturation of a young protagonist, usually a teenager.

Over the course of the story, they confront and overcome personal or societal hurdles, ultimately leading to self-discovery and self-acceptance.

Oftentimes, such storylines explore the unique experience of teenagers as they are developing cognitively and emotionally. Indeed, as my wife often tells me when we watch this storyline on television: “only a teenager would ever do that!”

These storylines do also have important place in society because they offer young people empathetic and supportive stories that can help young people through the important coming-of-age period of life.

“The Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Salinger is a key example, where the main character, Holden Caulfield, goes on a journey on his own after being kicked out of school. The journey ends with him learning that he does truly value his education and family, leading him to professing he will attend school again in the Fall.

5. Power and Corruption

This theme explores how power can corrupt individuals and societies, and the destructive consequences that can result.

This theme generally tells an important story about how power operates in society, makes commentary about injustice, and the ways in which power can bring out the worst (and best) in people.

This theme is often seen in political or dystopian literature, such as “Animal Farm” and “1984” by George Orwell. Similarly, in Shakespeare’s “Macbeth”, the titular character’s quest for power leads to his tragic downfall.

6. Redemption and Forgiveness

Another common theme is the exploration of the human capacity for making mistakes and the subsequent need for redemption or forgiveness.

Characters may be haunted by their past actions, seeking atonement, or striving to make amends.

We see this, for example, in the trope of the ghost who is stuck in this life until they achieve some degree of inner peace and redeption.

It is also seen in Christian literature, where forgiveness following repentance is an important moral underpinning of the faith.

Similarly, as with in the man vs self conflict trope, the character is seeking self-forgiveness and self-atonement.

Khaled Hosseini’s “The Kite Runner” is a powerful exploration of this theme, where the protagonist, Amir, spends a significant portion of his life seeking to redeem himself for his past betrayal of his friend Hassan.

7. War and Peace

Literature that explores war and peace might depict the physical and psychological impact of war on individuals and societies, the politics of war, or the tireless pursuit of peace.

They may also explore the aftermath of war on people’s lives. It can follow people’s struggles to achieve inner peace after a conflict and the trouble of returning to civilian life.

Or, they may explore the deep brotherhood forged in battle, such as in the epic Band of Brothers storyline.

Of course, there are many directions we can take with this theme, but at the center is the extraordinariness of wartime, which opens the door for exploration of intense aspects of humanity.

“All Quiet on the Western Front” by Erich Maria Remarque provides a harrowing look at the physical and emotional trauma endured by soldiers in World War I. On the other hand, Leo Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” is an expansive work that explores war from various perspectives, including the experiences of soldiers, families, and politicians.

8. Death and Mortality

Literature is at its best when it grapples with the themes at the core of the human experience – and the inevitability of death is certainly one of these.

Some works might meditate on the grief and loss associated with death, while others might use the prospect of death as a device to reflect on the meaning of life, or to explore how people live knowing they will die.

Oftentimes, this theme overlaps with religiosity, or themes about seeking meaning in life.

“The Death of Ivan Ilyich” by Leo Tolstoy explores the protagonist’s confrontation with his own mortality, leading him to reflect on the life he has lived and the value of genuine human connection.

9. Nature and Environment

With the rising threat of climate change, this theme has seen renewed attention in recent decades.

Environmental themes often explore humanity’s relationship with the natural world (oftentimes, for example, showing how small and insignificant we are in comparison to nature).

At the same time, other themes examine the environmental consequences of human action during the age of the anthroposcene.

Themes that explore conflict between man and nature represent one of the key conflicts in literature, such as when a person is challenged by being stuck in the desert or isolated from civilization and nature becomes the main antagonist or challenge to overcome.

Some literature might emphasize the spiritual or therapeutic aspects of nature, as seen in “Walden” by Henry David Thoreau, where Thoreau embarks on a two-year retreat to a cabin in the woods to explore simple living and the natural world. Alternatively, environmental literature, like “The Lorax” by Dr. Seuss, uses storytelling to convey warnings about environmental destruction and the importance of conservation.

10. Identity and Belonging

This theme delves into the exploration of the protagonist’s place in society and their personal identity.

The earlier theme of coming of age overlaps significantly here, and so too does the hero’s journey, which commonly examines a hero’s developing sense of self.

Characters in this type of theme might struggle with societal expectations, personal self-discovery, or feelings of alienation, seeking a place or group where they feel they belong.

“Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison, for instance, explores the protagonist’s struggle to define his identity within a society that refuses to see him as an individual rather than a racial stereotype. Similarly, “The Joy Luck Club” by Amy Tan navigates the complexities of cultural identity and generational differences among a group of Chinese-American women and their immigrant mothers.

11. Good versus Evil

One of the most fundamental themes in literature, good vs evil features a clear conflict between forces of good and forces of evil.

This theme often pits heroes against villains in a struggle that often represents larger moral, philosophical, or societal issues.

One of my complaints about many contemporary ‘pop lit’ and blockbuster films is that they fail to adequately examine the subjectivity of this false dichotomy – good vs evil themes are at their best when ‘evil’ is an elusive concept, and where we even are able to empathize with the evil character while still seeing the wrongs in their views.

J.K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter” series is a prime example, with Harry Potter and his friends constantly fighting against the dark wizard Lord Voldemort and his followers. The struggle between good and evil also underlies C.S. Lewis’s “The Chronicles of Narnia.”

12. Freedom and Confinement

This theme highlights the dichotomy between the desire for freedom and the reality of confinement.

Confinement might be physical, such as imprisonment or slavery, or it could be psychological, stemming from societal expectations or personal fears.

The ‘freedom’ element might emerge as a wistful theme, as in many coming-of-age narratives about the young character wanting to escape their hometown confines and beat culture narratives of the 1950s; or it might emerge as a struggle with physical constraint, such as themes surrounding imprisoned POWs.

“The Shawshank Redemption” by Stephen King, for example, explores both the physical confinement of prison and the ways in which characters can find freedom despite their circumstances. Similarly, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” by Ken Kesey features characters confined in a mental institution, highlighting their struggle for autonomy against oppressive authority.

13. Rebellion and Conformity

This theme centers on the tension between individual freedom and societal norms.

Characters might challenge authority, resist societal expectations, or fight against oppressive systems. (Here, we’re looking at strong overlap with the man vs society conflict narrative).

The theme may also explore an individual’s rebellion against a cult or religious group which they wish to escape, rebellion against parents, or search for an extraordinary life in an ordinary world. Sometimes, characters return to their roots, embracing conformity, while others escape the orbit or their cultural norms , achieving freedom through rebellion.

In Ray Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451,” the protagonist, Guy Montag, rebels against a dystopian society that has outlawed books and free thought. Montag’s transformation from a conformist fireman who burns books to a rebel who seeks knowledge demonstrates the struggle between conformity and rebellion.

14. Innocence and Experience

The theme of innocence vs experience often demonstrates a transition from a naive idealism to wisdom earned through experience .

For example, this theme may also explore the transition from the naivety of childhood to the disillusionment of adulthood.

Characters often face harsh realities or undergo experiences that shatter their innocence and lead them towards a more complex understanding of the world.

In “Lord of the Flies” by William Golding, a group of boys stranded on an uninhabited island gradually lose their innocence as their attempts at creating a society descend into savagery.

15. Reality versus Illusion

This theme investigates the nature of reality and the power of illusion.

Characters might grapple with distinguishing between what is real and what is not. In these situations, the story may play with the reader, not even allowing the reader an objective vision of what’s true and what not (such as in the unreliable narrator trope).

Similarly, the theme might explore how characters intentionally choose illusion over reality to escape unpleasant circumstances.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” explores this theme through the character of Jay Gatsby, who constructs a grand illusion of wealth and social status to win the love of Daisy Buchanan. Similarly, in “A Streetcar Named Desire” by Tennessee Williams, Blanche DuBois often retreats into her fantasies, unable to cope with her harsh reality.

16. The Search for Self-Identity

The theme of self-identity revolves around the process of understanding oneself, and it often involves characters undergoing significant personal growth or change.

This theme often begins with characters experiencing a sense of unease or dissatisfaction with their present circumstances or sense of self.

This feeling of discomfort acts as a catalyst for the characters to embark on a quest for self-identity, an inner journey often mirrored by an outward physical journey or experience.

Example in Literature

In Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis”, Gregor Samsa wakes up one day to find himself transformed into a monstrous insect. This shocking transformation forces him to reassess his identity, no longer defined by his role as a family provider, and navigate the alienation from his family and society.

17. The Injustice of Social Class

This theme explores the division of society into different social classes and the resulting inequity and conflict.

One of my favorite American authors, John Steinbeck, explores this theme in much of his literature. He takes the perspective of working-class Americans, examining how corporate interests make their life hard, how fellow Americans discriminate against them, and how they persevere through the relationships they build with other people in their social class.

In “Pride and Prejudice” by Jane Austen, the theme of social class is prevalent, influencing characters’ attitudes, behavior, and prospects for marriage. The story continually highlights the injustices of a rigid class system , such as the Bennet sisters’ limited prospects due to their lower social status and lack of dowries.

18. Isolation and Loneliness

The theme of isolation involves characters experiencing physical or emotional separation from others.

This isolation can be self-wrought, caused by an individual’s actions or decisions, or externally imposed, such as societal exclusion, geographical displacement, or unforeseen circumstances.

This theme explores the various forms and impacts of isolation, offering a deep dive into the psychological and emotional ramifications it has on individuals.

I am often compelled by storylines that use physical isolation as a metaphor for the sense of loneliness and isolatedness within the hearts and minds of the protagonists.

In Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” the creature, despite his desire for companionship, is shunned and rejected by society because of his monstrous appearance. This isolation leads to profound loneliness and ultimately, a desire for revenge against his creator, Victor Frankenstein.

19. Survival

This theme is often explored in literature through characters facing extreme conditions or challenges that test their will to survive.

There is generally a conflict here, which could be man vs nature (surviving the elements), man vs man (surviving against a foe), or even man vs technology (fighting against rogue technology, such as in Terminator ).

Survival themes can be a window into exploration of the tenacity and resilience of the human spirit against the odds.

In “Life of Pi” by Yann Martel, the protagonist Pi Patel finds himself stranded in the Pacific Ocean on a lifeboat with a Bengal tiger. Pi must use his intelligence and faith to survive in this hostile environment, with the story exploring themes of resilience, faith, and the human will to live.

20. The Human Condition

This theme delves into the shared experiences of being human, exploring a wide range of emotions, relationships, and moral dilemmas .

This theme is an examination of the joys, sorrows, conflicts, and complexities that define the human experience.

This theme has been prevalent in literature across all ages and cultures, as it captures the universality of human experiences, making it timeless and deeply relatable.

The human condition looks at the constants in human life, such as birth, growth, emotionality, aspiration, conflict, mortality, and how these shape our individual and collective experiences.

Leo Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina” provides a complex and insightful exploration of the human condition. Through its diverse cast of characters, the novel delves into various facets of humanity, such as love, infidelity, societal pressure, and the search for meaning in life.

21. The American Dream (Illusory or Real?)

This theme critiques the idealized vision of the American Dream — the belief that anyone can achieve success and prosperity through hard work.

Some all-American storylines (Like the film Pursuit of Happyness featuring Will Smith) show how the American dream is a worthy ideal .

Similarly, in politics (and even real life, for American nationalists), the American dream is something people hold onto as an ever-present fundamental truth: if you work hard and dream big, you’ll make it in the end. It just takes hard work.

But there are many texts that challenge this idea, demonstrating how the pursuit of the American dream can sometimes be a fickle and pointless task. Below are just two examples.

In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby,” the protagonist Jay Gatsby’s pursuit of wealth and social status, driven by his love for Daisy, ultimately leads to his downfall. Similarly, in “Death of a Salesman” by Arthur Miller, Willy Loman’s obsession with success and social acceptance blinds him to his family’s love, leading to tragedy.

22. The Absurdity of Existence

This theme underpins most texts that emerge out of existentialism and absurdism.

At the core of this theme is the exploration of the idea that life really has no meaning behind it. This can create some engaging and post-modernist texts whose storylines tend to meander, cut back in on themselves, and leave us at the end thinking “what a wild ride!”

This theme will tend to bring to the fore the chaotic, irrational, and meaningless features of a storyline.

In “The Stranger” by Albert Camus, the protagonist Meursault’s indifferent reaction to his mother’s death, his senseless murder of an Arab, and his subsequent philosophical musings in prison all point to the absurdity and meaninglessness of life.

I explore 5 more examples of existential literature here.

23. The Power of Faith

This theme looks at the role of faith or belief systems in shaping our lives and experiences.

While generally based on religion, it could also more generally represent faith in oneself, the journey of life, or family and friends.

Commonly, the theme will explore how having faith – and releasing stress, anxiety, and discontent when faith underpins our worldview – can provide strength, and hope.

For example, we’ll commonly see this theme when exploring an unbelievably tough journey – either physically (e.g. crossing a desert) or psychologically (e.g. coming to terms with death).

A darker turn, however, may demonstrate how faiths can clash and cause conflict.

In “Life of Pi” by Yann Martel, the protagonist Pi maintains his religious belief despite his extraordinary circumstances. His faith provides him comfort, hope, and strength to survive his ordeal at sea.

24. The Struggle for Women’s Rights

This theme involves the fight for gender equality, focusing on the experiences, struggles, and triumphs of women in a patriarchal society.

This theme could fit into the category of “protagonist vs society”, or rather “woman vs society!” It generally attempts to reflect real social, cultural, and political circumstances to make a social commentary about current social inequalities and the underlying patriarchy.

It may explore a woman’s attempts to assert her place in society, her struggles with discrimination, or women’s solidarity in the face of an oppressive outside world.

There has been a resurgence of so-called “bonnet dramas” in recent years that explore this theme, harking back to times when the patriarchy was far more overt.

Nevertheless, it can still be used in contemporary literature because, of course, the patriarchy does still exist in many areas of society and women often feel this intensely.

In Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” a dystopian future is depicted where women are reduced to their reproductive functions, stripped of their rights, and segregated according to their societal roles. The protagonist Offred’s experiences and memories underscore the theme of women’s subjugation and their struggle for autonomy. In contrast, “Little Women” by Louisa May Alcott explores this theme through the everyday experiences of the March sisters as they navigate societal expectations and strive for their dreams in 19th century America.

25. Fear of the Unknown

This theme plays on the inherent human fear of the unfamiliar or unknowable and is most commonly employed in horror, drama, and murder mysteries.

The fear of unknown motif is very effective for authors who want to create suspense, dread, or anticipation. By prolonging the mystery of an unknown threat, the author can compel the reader to keep on reading until the suspense is overcome.

This fear could stem from various sources: the future, death, the supernatural, or anything beyond human comprehension. A good example in film is the ongoing narrative of the ‘monster’ in the woods in the hit television series, Lost .

H.P. Lovecraft’s body of work, often grouped as Lovecraftian horror, prominently features this theme. His stories frequently involve characters who encounter cosmic horrors or ancient, malevolent beings that defy human understanding, highlighting the insignificance and vulnerability of humankind in the face of the unknown.

Some Closing Thoughts

There are a few notes worthy of providing as we wrap up this exploration of examples of themes in literature.

First, a theme isn’t usually stated explicitly . Instead, it is revealed gradually through elements such as the actions of characters, their thoughts and dialogue, the setting, and the plot. These elements come together to express the theme or themes of the work. So, as consumers of texts, themes might be bubbling under the surface, ready to surprise us toward the end of our experience, making us finally realize the message our author is presenting us about society or humanity.

Secondly, one literary work can, and often does, contain multiple themes . For example, George Orwell’s “1984” explores themes of totalitarianism, censorship, the manipulation of information, and the loss of individuality and privacy.

So, enjoy playing with themes – whether as a consumer or producer of literary content – and always remember to reflect on how those themes can help us dig ever deeper into an empathetic understanding of the complexity of the human condition.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Animism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Magical Thinking Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Social-Emotional Learning (Definition, Examples, Pros & Cons)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is Educational Psychology?

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Theme Definition

What is theme? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A theme is a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature. One key characteristic of literary themes is their universality, which is to say that themes are ideas that not only apply to the specific characters and events of a book or play, but also express broader truths about human experience that readers can apply to their own lives. For instance, John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath (about a family of tenant farmers who are displaced from their land in Oklahoma) is a book whose themes might be said to include the inhumanity of capitalism, as well as the vitality and necessity of family and friendship.

Some additional key details about theme:

- All works of literature have themes. The same work can have multiple themes, and many different works explore the same or similar themes.

- Themes are sometimes divided into thematic concepts and thematic statements . A work's thematic concept is the broader topic it touches upon (love, forgiveness, pain, etc.) while its thematic statement is what the work says about that topic. For example, the thematic concept of a romance novel might be love, and, depending on what happens in the story, its thematic statement might be that "Love is blind," or that "You can't buy love . "

- Themes are almost never stated explicitly. Oftentimes you can identify a work's themes by looking for a repeating symbol , motif , or phrase that appears again and again throughout a story, since it often signals a recurring concept or idea.

Theme Pronunciation

Here's how to pronounce theme: theem

Identifying Themes

Every work of literature—whether it's an essay, a novel, a poem, or something else—has at least one theme. Therefore, when analyzing a given work, it's always possible to discuss what the work is "about" on two separate levels: the more concrete level of the plot (i.e., what literally happens in the work), as well as the more abstract level of the theme (i.e., the concepts that the work deals with). Understanding the themes of a work is vital to understanding the work's significance—which is why, for example, every LitCharts Literature Guide uses a specific set of themes to help analyze the text.

Although some writers set out to explore certain themes in their work before they've even begun writing, many writers begin to write without a preconceived idea of the themes they want to explore—they simply allow the themes to emerge naturally through the writing process. But even when writers do set out to investigate a particular theme, they usually don't identify that theme explicitly in the work itself. Instead, each reader must come to their own conclusions about what themes are at play in a given work, and each reader will likely come away with a unique thematic interpretation or understanding of the work.

Symbol, Motif, and Leitwortstil

Writers often use three literary devices in particular—known as symbol , motif , and leitwortstil —to emphasize or hint at a work's underlying themes. Spotting these elements at work in a text can help you know where to look for its main themes.

- Near the beginning of Romeo and Juliet , Benvolio promises to make Romeo feel better about Rosaline's rejection of him by introducing him to more beautiful women, saying "Compare [Rosaline's] face with some that I shall show….and I will make thee think thy swan a crow." Here, the swan is a symbol for how Rosaline appears to the adoring Romeo, while the crow is a symbol for how she will soon appear to him, after he has seen other, more beautiful women.

- Symbols might occur once or twice in a book or play to represent an emotion, and in that case aren't necessarily related to a theme. However, if you start to see clusters of similar symbols appearing in a story, this may mean that the symbols are part of an overarching motif, in which case they very likely are related to a theme.

- For example, Shakespeare uses the motif of "dark vs. light" in Romeo and Juliet to emphasize one of the play's main themes: the contradictory nature of love. To develop this theme, Shakespeare describes the experience of love by pairing contradictory, opposite symbols next to each other throughout the play: not only crows and swans, but also night and day, moon and sun. These paired symbols all fall into the overall pattern of "dark vs. light," and that overall pattern is called a motif.

- A famous example is Kurt Vonnegut's repetition of the phrase "So it goes" throughout his novel Slaughterhouse Five , a novel which centers around the events of World War II. Vonnegut's narrator repeats the phrase each time he recounts a tragic story from the war, an effective demonstration of how the horrors of war have become normalized for the narrator. The constant repetition of the phrase emphasizes the novel's primary themes: the death and destruction of war, and the futility of trying to prevent or escape such destruction, and both of those things coupled with the author's skepticism that any of the destruction is necessary and that war-time tragedies "can't be helped."

Symbol, motif and leitwortstil are simply techniques that authors use to emphasize themes, and should not be confused with the actual thematic content at which they hint. That said, spotting these tools and patterns can give you valuable clues as to what might be the underlying themes of a work.

Thematic Concepts vs. Thematic Statements

A work's thematic concept is the broader topic it touches upon—for instance:

- Forgiveness

while its thematic statement is the particular argument the writer makes about that topic through his or her work, such as:

- Human judgement is imperfect.

- Love cannot be bought.

- Getting revenge on someone else will not fix your problems.

- Learning to forgive is part of becoming an adult.

Should You Use Thematic Concepts or Thematic Statements?

Some people argue that when describing a theme in a work that simply writing a thematic concept is insufficient, and that instead the theme must be described in a full sentence as a thematic statement. Other people argue that a thematic statement, being a single sentence, usually creates an artificially simplistic description of a theme in a work and is therefore can actually be more misleading than helpful. There isn't really a right answer in this debate.

In our LitCharts literature study guides , we usually identify themes in headings as thematic concepts, and then explain the theme more fully in a few paragraphs. We find thematic statements limiting in fully exploring or explaining a the theme, and so we don't use them. Please note that this doesn't mean we only rely on thematic concepts—we spend paragraphs explaining a theme after we first identify a thematic concept. If you are asked to describe a theme in a text, you probably should usually try to at least develop a thematic statement about the text if you're not given the time or space to describe it more fully. For example, a statement that a book is about "the senselessness of violence" is a lot stronger and more compelling than just saying that the book is about "violence."

Identifying Thematic Statements

One way to try to to identify or describe the thematic statement within a particular work is to think through the following aspects of the text:

- Plot: What are the main plot elements in the work, including the arc of the story, setting, and characters. What are the most important moments in the story? How does it end? How is the central conflict resolved?

- Protagonist: Who is the main character, and what happens to him or her? How does he or she develop as a person over the course of the story?

- Prominent symbols and motifs: Are there any motifs or symbols that are featured prominently in the work—for example, in the title, or recurring at important moments in the story—that might mirror some of the main themes?

After you've thought through these different parts of the text, consider what their answers might tell you about the thematic statement the text might be trying to make about any given thematic concept. The checklist above shouldn't be thought of as a precise formula for theme-finding, but rather as a set of guidelines, which will help you ask the right questions and arrive at an interesting thematic interpretation.

Theme Examples

The following examples not only illustrate how themes develop over the course of a work of literature, but they also demonstrate how paying careful attention to detail as you read will enable you to come to more compelling conclusions about those themes.

Themes in F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby

Fitzgerald explores many themes in The Great Gatsby , among them the corruption of the American Dream .

- The story's narrator is Minnesota-born Nick Caraway, a New York bonds salesman. Nick befriends Jay Gatsby, the protagonist, who is a wealthy man who throws extravagant parties at his mansion.

- The central conflict of the novel is Gatsby's pursuit of Daisy, whom he met and fell in love with as a young man, but parted from during World War I.

- He makes a fortune illegally by bootlegging alcohol, to become the sort of wealthy man he believes Daisy is attracted to, then buys a house near her home, where she lives with her husband.

- While he does manage to re-enter Daisy's life, she ultimately abandons him and he dies as a result of her reckless, selfish behavior.

- Gatsby's house is on the water, and he stares longingly across the water at a green light that hangs at the edge of a dock at Daisy's house which sits across a the bay. The symbol of the light appears multiple times in the novel—during the early stages of Gatsby's longing for Daisy, during his pursuit of her, and after he dies without winning her love. It symbolizes both his longing for daisy and the distance between them (the distance of space and time) that he believes (incorrectly) that he can bridge.

- In addition to the green light, the color green appears regularly in the novel. This motif of green broadens and shapes the symbolism of the green light and also influences the novel's themes. While green always remains associated with Gatsby's yearning for Daisy and the past, and also his ambitious striving to regain Daisy, it also through the motif of repeated green becomes associated with money, hypocrisy, and destruction. Gatsby's yearning for Daisy, which is idealistic in some ways, also becomes clearly corrupt in others, which more generally impacts what the novel is saying about dreams more generally and the American Dream in particular.

Gatsby pursues the American Dream, driven by the idea that hard work can lead anyone from poverty to wealth, and he does so for a single reason: he's in love with Daisy. However, he pursues the dream dishonestly, making a fortune by illegal means, and ultimately fails to achieve his goal of winning Daisy's heart. Furthermore, when he actually gets close to winning Daisy's heart, she brings about his downfall. Through the story of Gatsby and Daisy, Fitzgerald expresses the point of view that the American Dream carries at its core an inherent corruption. You can read more about the theme of The American Dream in The Great Gatsby here .

Themes in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart

In Things Fall Apart , Chinua Achebe explores the theme of the dangers of rigidly following tradition .

- Okonkwo is obsessed with embodying the masculine ideals of traditional Igbo warrior culture.

- Okonkwo's dedication to his clan's traditions is so extreme that it even alienates members of his own family, one of whom joins the Christians.

- The central conflict: Okonkwo's community adapts to colonization in order to survive, becoming less warlike and allowing the minor injustices that the colonists inflict upon them to go unchallenged. Okonkwo, however, refuses to adapt.

- At the end of the novel, Okonkwo impulsively kills a Christian out of anger. Recognizing that his community does not support his crime, Okonkwo kills himself in despair.

- Clanswomen who give birth to twins abandon the babies in the forest to die, according to traditional beliefs that twins are evil.

- Okonkwo kills his beloved adopted son, a prisoner of war, according to the clan's traditions.

- Okonkwo sacrifices a goat in repentence, after severely beating his wife during the clan's holy week.

Through the tragic story of Okonkwo, Achebe is clearly dealing with the theme of tradition, but a close examination of the text reveals that he's also making a clear thematic statement that following traditions too rigidly leads people to the greatest sacrifice of all: that of personal agency . You can read more about this theme in Things Fall Apart here .

Themes in Robert Frost's The Road Not Taken

Poem's have themes just as plot-driven narratives do. One theme that Robert Frost explores in this famous poem, The Road Not Taken , is the illusory nature of free will .

- The poem's speaker stands at a fork in the road, in a "yellow wood."

- He (or she) looks down one path as far as possible, then takes the other, which seems less worn.

- The speaker then admits that the paths are about equally worn—there's really no way to tell the difference—and that a layer of leaves covers both of the paths, indicating that neither has been traveled recently.

- After taking the second path, the speaker finds comfort in the idea of taking the first path sometime in the future, but acknowledges that he or she is unlikely to ever return to that particular fork in the woods.

- The speaker imagines how, "with a sigh" she will tell someone in the future, "I took the road less travelled—and that has made all the difference."

- By wryly predicting his or her own need to romanticize, and retroactively justify, the chosen path, the speaker injects the poem with an unmistakeable hint of irony .

- The speaker's journey is a symbol for life, and the two paths symbolize different life paths, with the road "less-travelled" representing the path of an individualist or lone-wolf. The fork where the two roads diverge represents an important life choice. The road "not taken" represents the life path that the speaker would have pursued had he or she had made different choices.

Frost's speaker has reached a fork in the road, which—according to the symbolic language of the poem—means that he or she must make an important life decision. However, the speaker doesn't really know anything about the choice at hand: the paths appear to be the same from the speaker's vantage point, and there's no way he or she can know where the path will lead in the long term. By showing that the only truly informed choice the speaker makes is how he or she explains their decision after they have already made it , Frost suggests that although we pretend to make our own choices, our lives are actually governed by chance.

What's the Function of Theme in Literature?

Themes are a huge part of what readers ultimately take away from a work of literature when they're done reading it. They're the universal lessons and ideas that we draw from our experiences of works of art: in other words, they're part of the whole reason anyone would want to pick up a book in the first place!

It would be difficult to write any sort of narrative that did not include any kind of theme. The narrative itself would have to be almost completely incoherent in order to seem theme-less, and even then readers would discern a theme about incoherence and meaninglessness. So themes are in that sense an intrinsic part of nearly all writing. At the same time, the themes that a writer is interested in exploring will significantly impact nearly all aspects of how a writer chooses to write a text. Some writers might know the themes they want to explore from the beginning of their writing process, and proceed from there. Others might have only a glimmer of an idea, or have new ideas as they write, and so the themes they address might shift and change as they write. In either case, though, the writer's ideas about his or her themes will influence how they write.

One additional key detail about themes and how they work is that the process of identifying and interpreting them is often very personal and subjective. The subjective experience that readers bring to interpreting a work's themes is part of what makes literature so powerful: reading a book isn't simply a one-directional experience, in which the writer imparts their thoughts on life to the reader, already distilled into clear thematic statements. Rather, the process of reading and interpreting a work to discover its themes is an exchange in which readers parse the text to tease out the themes they find most relevant to their personal experience and interests.

Other Helpful Theme Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Theme: An in-depth explanation of theme that also breaks down the difference between thematic concepts and thematic statements.

- The Dictionary Definition of Theme: A basic definition and etymology of the term.

- In this instructional video , a teacher explains her process for helping students identify themes.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1929 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,694 quotes across 1929 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Dynamic Character

- Static Character

- Common Meter

- Extended Metaphor

- Falling Action

- Tragic Hero

- Anthropomorphism

- Understatement

- Climax (Figure of Speech)

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Use Themes

I. What is Theme?

One of the first questions to ask upon hearing someone has written a story is, “What’s it about?” or “What’s the point?” Short answers may range from love to betrayal or from the coming of age to the haziness of memory. The central idea, topic, or point of a story, essay, or narrative is its theme .

II. Examples of Theme

A man, fueled by an urge for power and control due to his own pride, builds a supercomputer. That supercomputer then takes over the world, causing chaos and struggle galore.

This sci-fi style story contains many common themes. A few of its themes include:

- Danger of excessive pride

- The risky relationship between humankind and developing technology

A boy and a girl fall in love. The boy is forced to join the army and fights to survive in a war-torn country as his beloved waits at home. When he returns from war, the two are united and married.

The love story also has many common themes in literature:

- The power of true love

- Fate, which sometimes tears lovers apart and then joins them together

As can be seen from these examples, themes can range widely from ideas, as large as love and war, to others as specific as the relationship between humankind and technology.

III. Types of Theme

Just as a life is not constantly immersed in love, the pursuit of knowledge, or the struggle of the individual versus society, themes are not always constantly present in a story or composition. Rather, they weave in and out, can disappear entirely, or appear surprisingly mid-read. This is because there are two types of themes: major and minor themes.

a. Major Themes