Document Analysis - How to Analyze Text Data for Research

Introduction

What is document analysis, where is document analysis used, how to perform document analysis, what is text analysis, atlas.ti as text analysis software.

In qualitative research , you can collect primary data through surveys , observations , or interviews , to name a few examples. In addition, you can rely on document analysis when the data already exists in secondary sources like books, public reports, or other archival records that are relevant to your research inquiry.

In this article, we will look at the role of document analysis, the relationship between document analysis and text analysis, and how text analysis software like ATLAS.ti can help you conduct qualitative research.

Document analysis is a systematic procedure used in qualitative research to review and interpret the information embedded in written materials. These materials, often referred to as “documents,” can encompass a wide range of physical and digital sources, such as newspapers, diaries, letters, policy documents, contracts, reports, transcripts, and many others.

At its core, document analysis involves critically examining these sources to gather insightful data and understand the context in which they were created. Research can perform sentiment analysis , text mining, and text categorization, to name a few methods. The goal is not just to derive facts from the documents, but also to understand the underlying nuances, motivations, and perspectives that they represent. For instance, a historical researcher may examine old letters not just to get a chronological account of events, but also to understand the emotions, beliefs, and values of people during that era.

Benefits of document analysis

There are several advantages to using document analysis in research:

- Authenticity : Since documents are typically created for purposes other than research, they can offer an unobtrusive and genuine insight into the topic at hand, without the potential biases introduced by direct observation or interviews.

- Availability : Documents, especially those in the public domain, are widely accessible, making it easier for researchers to source information.

- Cost-effectiveness : As these documents already exist, researchers can save time and resources compared to other data collection methods.

However, document analysis is not without challenges. One must ensure the documents are authentic and reliable. Furthermore, the researcher must be adept at discerning between objective facts and subjective interpretations present in the document.

Document analysis is a versatile method in qualitative research that offers a lens into the intricate layers of meaning, context, and perspective found within textual materials. Through careful and systematic examination, it unveils the richness and depth of the information housed in documents, providing a unique dimension to research findings.

Document analysis is employed in a myriad of sectors, serving various purposes to generate actionable insights. Whether it's understanding customer sentiments or gleaning insights from historical records, this method offers valuable information. Here are some examples of how document analysis is applied.

Analyzing surveys and their responses

A common use of document analysis in the business world revolves around customer surveys . These surveys are designed to collect data on the customer experience, seeking to understand how products or services meet or fall short of customer expectations.

By analyzing customer survey responses , companies can identify areas of improvement, gauge satisfaction levels, and make informed decisions to enhance the customer experience. Even if customer service teams designed a survey for a specific purpose, text analytics of the responses can focus on different angles to gather insights for new research questions.

Examining customer feedback through social media posts

In today's digital age, social media is a goldmine of customer feedback. Customers frequently share their experiences, both positive and negative, on platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Through document analysis of social media posts, companies can get a real-time pulse of their customer sentiments. This not only helps in immediate issue resolution but also in shaping product or service strategies to align with customer preferences.

Interpreting customer support tickets

Another rich source of data is customer support tickets. These tickets often contain detailed descriptions of issues faced by customers, their frustrations, or sometimes their appreciation for assistance received.

By employing document analysis on these tickets, businesses can detect patterns, identify recurring issues, and work towards streamlining their support processes. This ensures a smoother and more satisfying customer experience.

Historical research and social studies

Beyond the world of business, document analysis plays a pivotal role in historical and social research. Scholars analyze old manuscripts, letters, and other archival materials to construct a narrative of past events, cultures, and civilizations.

As a result, document analysis is an ideal method for historical research since generating new data is less feasible than turning to existing sources for analysis. Researchers can not only examine historical narratives but also how those narratives were constructed in their own time.

Turn to ATLAS.ti for your data analysis needs

Try out our powerful data analysis tools with a free trial to make the most out of your data today.

Performing document analysis is a structured process that ensures researchers can derive meaningful, qualitative insights by organizing source material into structured data . Here's a brief outline of the process:

- Define the research question

- Choose relevant documents

- Prepare and organize the documents

- Begin initial review and coding

- Analyze and interpret the data

- Present findings and draw conclusions

The process in detail

Before diving into the documents, it's crucial to have a clear research question or objective. This serves as the foundation for the entire analysis and guides the selection and review of documents. A well-defined question will focus the research, ensuring that the document analysis is targeted and relevant.

The next step is to identify and select documents that align with the research question. It's vital to ensure that these documents are credible, reliable, and pertinent to the research inquiry. The chosen materials can vary from official reports, personal diaries, to digital resources like social media data , depending on the nature of the research.

Once the documents are selected, they need to be organized in a manner that facilitates smooth analysis. This could mean categorizing documents by themes, chronology, or source types. Digital tools and data analysis software , such as ATLAS.ti, can assist in this phase, making the organization more efficient and helping researchers locate specific data when needed.

With everything in place, the researcher starts an initial review of the documents. During this phase, the emphasis is on identifying patterns, themes, or specific information relevant to the research question.

Coding involves assigning labels or tags to sections of the text to categorize the information. This step is iterative, and codes can be refined as the researcher delves deeper.

After coding, interesting patterns across codes can be analyzed. Here, researchers seek to draw meaningful connections between codes, identify overarching themes, and interpret the data in the context of the research question .

This is where the hidden insights and deeper understanding emerge, as researchers juxtapose various pieces of information and infer meaning from them.

Finally, after the intensive process of document analysis, the researcher consolidates their findings, crafting a narrative or report that presents the results. This might also involve visual representations like charts or graphs, especially when demonstrating patterns or trends.

Drawing conclusions involves synthesizing the insights gained from the analysis and offering answers or perspectives in relation to the original research question.

Ultimately, document analysis is a meticulous and iterative procedure. But with a clear plan and systematic approach, it becomes a potent tool in the researcher's arsenal, allowing them to uncover profound insights from textual data.

Text analysis, often referenced alongside document analysis, is a method that focuses on extracting meaningful information from textual data. While document analysis revolves around reviewing and interpreting data from various sources, text analysis hones in on the intricate details within these documents, enabling a deeper understanding. Both these methods are vital in fields such as linguistics, literature, social sciences, and business analytics.

In the context of document analysis, text analysis emerges as a nuanced exploration of the textual content. After documents have been sourced, be it from books, articles, social networks, or any other medium, they undergo a preprocessing phase. Here, irrelevant information is eliminated, errors are rectified, and the text may be translated or converted to ensure uniformity.

This cleaned text is then tokenized into smaller units like words or phrases, facilitating a granular review. Techniques specific to text analysis, such as topic modeling to determine discussed subjects or pattern recognition to identify trends, are applied.

The derived insights can be visualized using tools like graphs or charts, offering a clearer understanding of the content's depth. Interpretation follows, allowing researchers to draw actionable insights or theoretical conclusions based on both the broader document context and the specific text analysis.

Merging text analysis with document analysis presents unique challenges. With the proliferation of digital content, managing vast data sets becomes a significant hurdle. The inherent variability of language, laden with cultural nuances, idioms, and sometimes sarcasm, can make precise interpretation elusive.

Many text analysis tools exist that can facilitate the analytical process. ATLAS.ti offers a well-rounded, useful solution as a text analytics software . In this section, we'll highlight some of the tools that can help you conduct document analysis.

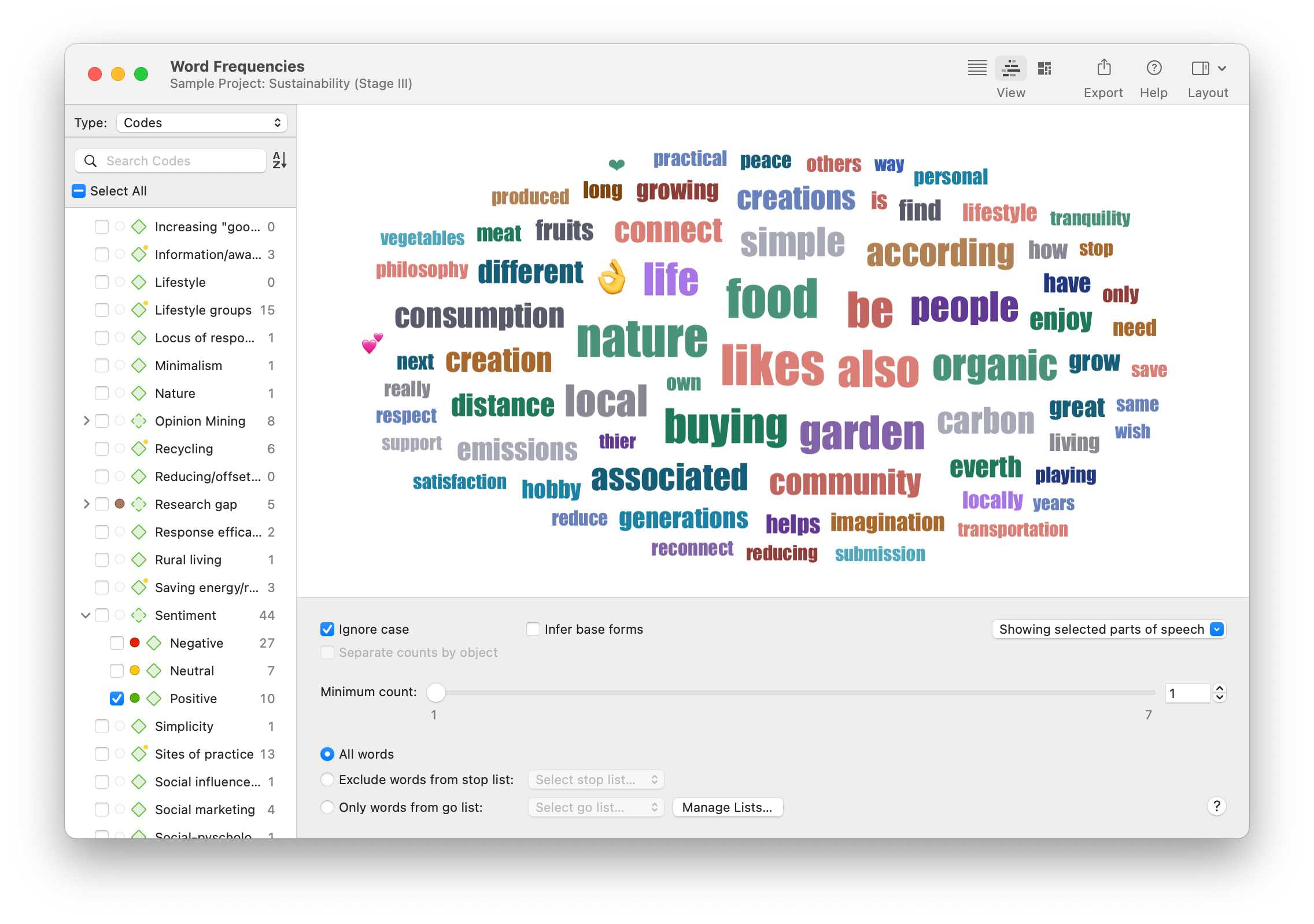

Word Frequencies

A word cloud can be a powerful text analytics tool to understand the nature of human language as it pertains to a particular context. Researchers can perform text mining on their unstructured text data to get a sense of what is being discussed. The Word Frequencies tool can also parse out specific parts of speech, facilitating more granular text extraction.

Sentiment Analysis

The Sentiment Analysis tool employs natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning to analyze text based on sentiment and facilitate natural language understanding. This is important for tasks such as, for example, analyzing customer reviews and assessing customer satisfaction, because you can quickly categorize large numbers of customer data records by their positive or negative sentiment.

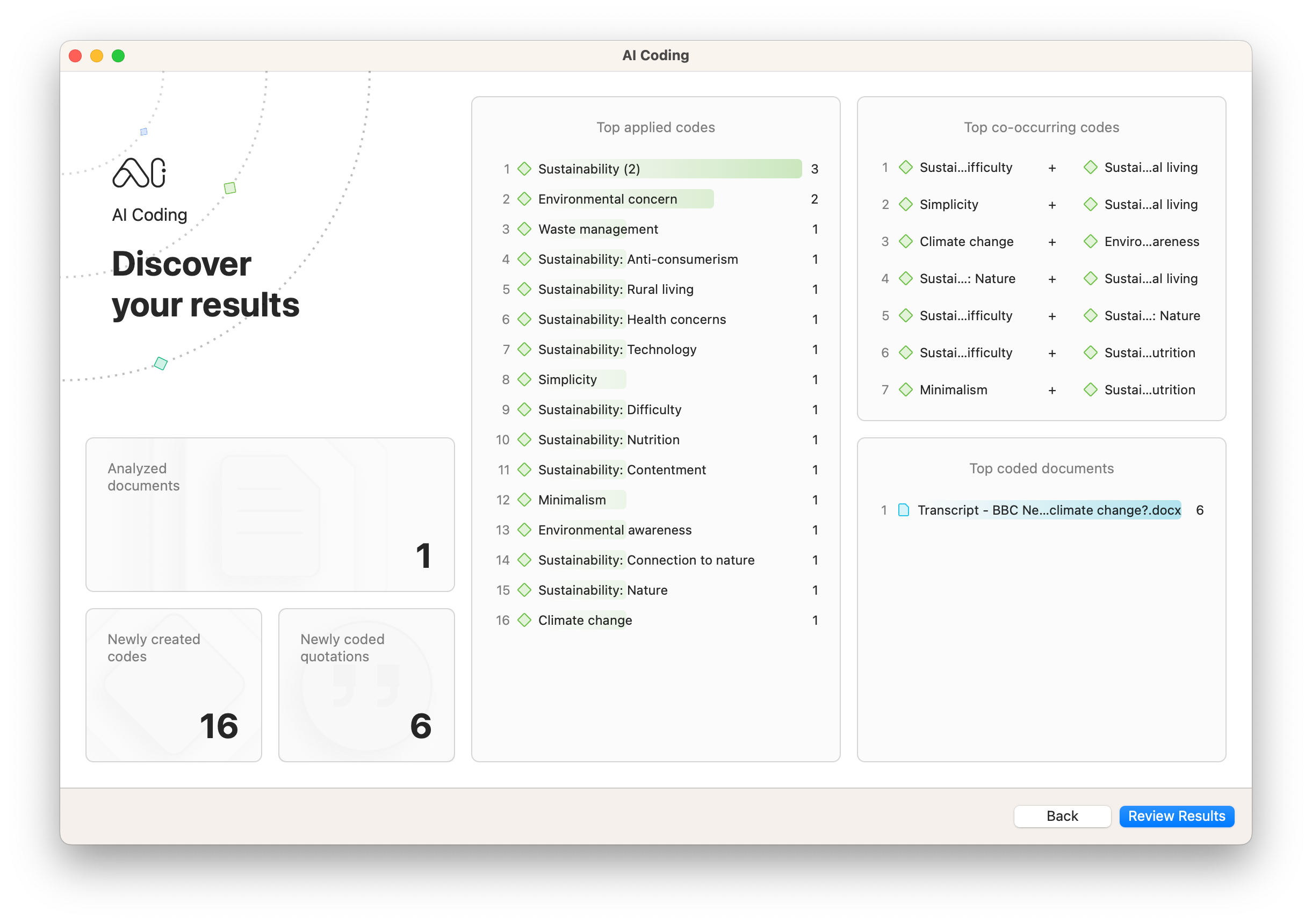

AI Coding relies on massive amounts of training data to interpret text and automatically code large amounts of qualitative data. Rather than read each and every document line by line, you can turn to AI Coding to process your data and devote time to the more essential tasks of analysis such as critical reflection and interpretation.

These text analytics tools can be a powerful complement to research. When you're conducting document analysis to understand the meaning of text, AI Coding can help with providing a code structure or organization of data that helps to identify deeper insights.

AI Summaries

Dealing with large numbers of discrete documents can be a daunting task if done manually, especially if each document in your data set is lengthy and complicated. Simplifying the meaning of documents down to their essential insights can help researchers identify patterns in the data.

AI Summaries fills this role by using natural language processing algorithms to simplify data to its salient points. Text generated by AI Summaries are stored in memos attached to documents to illustrate pathways to coding and analysis or to highlight how the data conveys meaning.

Take advantage of ATLAS.ti's analysis tools with a free trial

Let our powerful data analysis interface make the most out of your data. Download a free trial today.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Documentary Analysis – Methods, Applications and Examples

Documentary Analysis – Methods, Applications and Examples

Table of Contents

Documentary Analysis

Definition:

Documentary analysis, also referred to as document analysis , is a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents. This method involves a detailed review of the documents to extract themes or patterns relevant to the research topic .

Documents used in this type of analysis can include a wide variety of materials such as text (words) and images that have been recorded without a researcher’s intervention. The domain of document analysis, therefore, includes all kinds of texts – books, newspapers, letters, study reports, diaries, and more, as well as images like maps, photographs, and films.

Documentary analysis provides valuable insight and a unique perspective on the past, contextualizing the present and providing a baseline for future studies. It is also an essential tool in case studies and when direct observation or participant observation is not possible.

The process usually involves several steps:

- Sourcing : This involves identifying the document or source, its origin, and the context in which it was created.

- Contextualizing : This involves understanding the social, economic, political, and cultural circumstances during the time the document was created.

- Interrogating : This involves asking a series of questions to help understand the document better. For example, who is the author? What is the purpose of the document? Who is the intended audience?

- Making inferences : This involves understanding what the document says (either directly or indirectly) about the topic under study.

- Checking for reliability and validity : Just like other research methods, documentary analysis also involves checking for the validity and reliability of the documents being analyzed.

Documentary Analysis Methods

Documentary analysis as a qualitative research method involves a systematic process. Here are the main steps you would generally follow:

Defining the Research Question

Before you start any research , you need a clear and focused research question . This will guide your decision on what documents you need to analyze and what you’re looking for within them.

Selecting the Documents

Once you know what you’re looking for, you can start to select the relevant documents. These can be a wide range of materials – books, newspapers, letters, official reports, diaries, transcripts of speeches, archival materials, websites, social media posts, and more. They can be primary sources (directly from the time/place/person you are studying) or secondary sources (analyses created by others).

Reading and Interpreting the Documents

You need to closely read the selected documents to identify the themes and patterns that relate to your research question. This might involve content analysis (looking at what is explicitly stated) and discourse analysis (looking at what is implicitly stated or implied). You need to understand the context in which the document was created, the author’s purpose, and the audience’s perspective.

Coding and Categorizing the Data

After the initial reading, the data (text) can be broken down into smaller parts or “codes.” These codes can then be categorized based on their similarities and differences. This process of coding helps in organizing the data and identifying patterns or themes.

Analyzing the Data

Once the data is organized, it can be analyzed to make sense of it. This can involve comparing the data with existing theories, examining relationships between categories, or explaining the data in relation to the research question.

Validating the Findings

The researcher needs to ensure that the findings are accurate and credible. This might involve triangulating the data (comparing it with other sources or types of data), considering alternative explanations, or seeking feedback from others.

Reporting the Findings

The final step is to report the findings in a clear, structured way. This should include a description of the methods used, the findings, and the researcher’s interpretations and conclusions.

Applications of Documentary Analysis

Documentary analysis is widely used across a variety of fields and disciplines due to its flexible and comprehensive nature. Here are some specific applications:

Historical Research

Documentary analysis is a fundamental method in historical research. Historians use documents to reconstruct past events, understand historical contexts, and interpret the motivations and actions of historical figures. Documents analyzed may include personal letters, diaries, official records, newspaper articles, photographs, and more.

Social Science Research

Sociologists, anthropologists, and political scientists use documentary analysis to understand social phenomena, cultural practices, political events, and more. This might involve analyzing government policies, organizational records, media reports, social media posts, and other documents.

Legal Research

In law, documentary analysis is used in case analysis and statutory interpretation. Legal practitioners and scholars analyze court decisions, statutes, regulations, and other legal documents.

Business and Market Research

Companies often analyze documents to gather business intelligence, understand market trends, and make strategic decisions. This might involve analyzing competitor reports, industry news, market research studies, and more.

Media and Communication Studies

Scholars in these fields might analyze media content (e.g., news reports, advertisements, social media posts) to understand media narratives, public opinion, and communication practices.

Literary and Film Studies

In these fields, the “documents” might be novels, poems, films, or scripts. Scholars analyze these texts to interpret their meaning, understand their cultural context, and critique their form and content.

Educational Research

Educational researchers may analyze curricula, textbooks, lesson plans, and other educational documents to understand educational practices and policies.

Health Research

Health researchers may analyze medical records, health policies, clinical guidelines, and other documents to study health behaviors, healthcare delivery, and health outcomes.

Examples of Documentary Analysis

Some Examples of Documentary Analysis might be:

- Example 1 : A historian studying the causes of World War I might analyze diplomatic correspondence, government records, newspaper articles, and personal diaries from the period leading up to the war.

- Example 2 : A policy analyst trying to understand the impact of a new public health policy might analyze the policy document itself, as well as related government reports, statements from public health officials, and news media coverage of the policy.

- Example 3 : A market researcher studying consumer trends might analyze social media posts, customer reviews, industry reports, and news articles related to the market they’re studying.

- Example 4 : An education researcher might analyze curriculum documents, textbooks, and lesson plans to understand how a particular subject is being taught in schools. They might also analyze policy documents to understand the broader educational policy context.

- Example 5 : A criminologist studying hate crimes might analyze police reports, court records, news reports, and social media posts to understand patterns in hate crimes, as well as societal and institutional responses to them.

- Example 6 : A journalist writing a feature article on homelessness might analyze government reports on homelessness, policy documents related to housing and social services, news articles on homelessness, and social media posts from people experiencing homelessness.

- Example 7 : A literary critic studying a particular author might analyze their novels, letters, interviews, and reviews of their work to gain insight into their themes, writing style, influences, and reception.

When to use Documentary Analysis

Documentary analysis can be used in a variety of research contexts, including but not limited to:

- When direct access to research subjects is limited : If you are unable to conduct interviews or observations due to geographical, logistical, or ethical constraints, documentary analysis can provide an alternative source of data.

- When studying the past : Documents can provide a valuable window into historical events, cultures, and perspectives. This is particularly useful when the people involved in these events are no longer available for interviews or when physical evidence is lacking.

- When corroborating other sources of data : If you have collected data through interviews, surveys, or observations, analyzing documents can provide additional evidence to support or challenge your findings. This process of triangulation can enhance the validity of your research.

- When seeking to understand the context : Documents can provide background information that helps situate your research within a broader social, cultural, historical, or institutional context. This can be important for interpreting your other data and for making your research relevant to a wider audience.

- When the documents are the focus of the research : In some cases, the documents themselves might be the subject of your research. For example, you might be studying how a particular topic is represented in the media, how an author’s work has evolved over time, or how a government policy was developed.

- When resources are limited : Compared to methods like experiments or large-scale surveys, documentary analysis can often be conducted with relatively limited resources. It can be a particularly useful method for students, independent researchers, and others who are working with tight budgets.

- When providing an audit trail for future researchers : Documents provide a record of events, decisions, or conditions at specific points in time. They can serve as an audit trail for future researchers who want to understand the circumstances surrounding a particular event or period.

Purpose of Documentary Analysis

The purpose of documentary analysis in research can be multifold. Here are some key reasons why a researcher might choose to use this method:

- Understanding Context : Documents can provide rich contextual information about the period, environment, or culture under investigation. This can be especially useful for historical research, where the context is often key to understanding the events or trends being studied.

- Direct Source of Data : Documents can serve as primary sources of data. For instance, a letter from a historical figure can give unique insights into their thoughts, feelings, and motivations. A company’s annual report can offer firsthand information about its performance and strategy.

- Corroboration and Verification : Documentary analysis can be used to validate and cross-verify findings derived from other research methods. For example, if interviews suggest a particular outcome, relevant documents can be reviewed to confirm the accuracy of this finding.

- Substituting for Other Methods : When access to the field or subjects is not possible due to various constraints (geographical, logistical, or ethical), documentary analysis can serve as an alternative to methods like observation or interviews.

- Unobtrusive Method : Unlike some other research methods, documentary analysis doesn’t require interaction with subjects, and therefore doesn’t risk altering the behavior of those subjects.

- Longitudinal Analysis : Documents can be used to study change over time. For example, a researcher might analyze census data from multiple decades to study demographic changes.

- Providing Rich, Qualitative Data : Documents often provide qualitative data that can help researchers understand complex issues in depth. For example, a policy document might reveal not just the details of the policy, but also the underlying beliefs and attitudes that shaped it.

Advantages of Documentary Analysis

Documentary analysis offers several advantages as a research method:

- Unobtrusive : As a non-reactive method, documentary analysis does not require direct interaction with human subjects, which means that the research doesn’t affect or influence the subjects’ behavior.

- Rich Historical and Contextual Data : Documents can provide a wealth of historical and contextual information. They allow researchers to examine events and perspectives from the past, even from periods long before modern research methods were established.

- Efficiency and Accessibility : Many documents are readily accessible, especially with the proliferation of digital archives and databases. This accessibility can often make documentary analysis a more efficient method than others that require data collection from human subjects.

- Cost-Effective : Compared to other methods, documentary analysis can be relatively inexpensive. It generally requires fewer resources than conducting experiments, surveys, or fieldwork.

- Permanent Record : Documents provide a permanent record that can be reviewed multiple times. This allows for repeated analysis and verification of the data.

- Versatility : A wide variety of documents can be analyzed, from historical texts to contemporary digital content, providing flexibility and applicability to a broad range of research questions and fields.

- Ability to Cross-Verify (Triangulate) Data : Documentary analysis can be used alongside other methods as a means of triangulating data, thus adding validity and reliability to the research.

Limitations of Documentary Analysis

While documentary analysis offers several benefits as a research method, it also has its limitations. It’s important to keep these in mind when deciding to use documentary analysis and when interpreting your findings:

- Authenticity : Not all documents are genuine, and sometimes it can be challenging to verify the authenticity of a document, particularly for historical research.

- Bias and Subjectivity : All documents are products of their time and their authors. They may reflect personal, cultural, political, or institutional biases, and these biases can affect the information they contain and how it is presented.

- Incomplete or Missing Information : Documents may not provide all the information you need for your research. There may be gaps in the record, or crucial information may have been omitted, intentionally or unintentionally.

- Access and Availability : Not all documents are readily available for analysis. Some may be restricted due to privacy, confidentiality, or security considerations. Others may be difficult to locate or access, particularly historical documents that haven’t been digitized.

- Interpretation : Interpreting documents, particularly historical ones, can be challenging. You need to understand the context in which the document was created, including the social, cultural, political, and personal factors that might have influenced its content.

- Time-Consuming : While documentary analysis can be cost-effective, it can also be time-consuming, especially if you have a large number of documents to analyze or if the documents are lengthy or complex.

- Lack of Control Over Data : Unlike methods where the researcher collects the data themselves (e.g., through experiments or surveys), with documentary analysis, you have no control over what data is available. You are reliant on what others have chosen to record and preserve.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Narrative Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Multidimensional Scaling – Types, Formulas and...

Descriptive Statistics – Types, Methods and...

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Uniform Histogram – Purpose, Examples and Guide

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, document analysis as a qualitative research method.

Qualitative Research Journal

ISSN : 1443-9883

Article publication date: 3 August 2009

This article examines the function of documents as a data source in qualitative research and discusses document analysis procedure in the context of actual research experiences. Targeted to research novices, the article takes a nuts‐and‐bolts approach to document analysis. It describes the nature and forms of documents, outlines the advantages and limitations of document analysis, and offers specific examples of the use of documents in the research process. The application of document analysis to a grounded theory study is illustrated.

- Content analysis

- Grounded theory

- Thematic analysis

- Triangulation

Bowen, G.A. (2009), "Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method", Qualitative Research Journal , Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 27-40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2009, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

No products in the cart.

The Basics of Document Analysis

Document analysis is the process of reviewing or evaluating documents both printed and electronic in a methodical manner. The document analysis method, like many other qualitative research methods, involves examining and interpreting data to uncover meaning, gain understanding, and come to a conclusion.

What is Meant by Document Analysis?

Document analysis pertains to the process of interpreting documents for an assessment topic by the researcher as a means of giving voice and meaning. In Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method by Glenn A. Bowen , document analysis is described as, “... a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents—both printed and electronic (computer-based and Internet-transmitted) material. Like other analytical methods in qualitative research, document analysis requires that data be examined and interpreted in order to elicit meaning, gain understanding, and develop empirical knowledge.”

During the analysis of documents, the content is categorized into distinct themes, similar to the way transcripts from interviews or focus groups are analyzed. The documents may also be graded or scored using a rubric.

Document analysis is a social research method of great value, and it plays a crucial role in most triangulation methods, combining various methods to study a particular phenomenon.

>> View Webinar: How-To’s for Data Analysis

Documents fall into three main categories:

- Personal Documents: A personal account of an individual's beliefs, actions, and experiences. The following are examples: e-mails, calendars, scrapbooks, Facebook posts, incident reports, blogs, duty logs, newspapers, and reflections or journals.

- Public Records: Records of an organization's activities that are maintained continuously over time. These include mission statements, student transcripts, annual reports, student handbooks, policy manuals, syllabus, and strategic plans.

- Physical Evidence: Artifacts or items found within a study setting, also referred to as artifacts. Among these are posters, flyers, agendas, training materials, and handbooks.

The qualitative researcher generally makes use of two or more resources, each using a different data source and methodology, to achieve convergence and corroboration. An important purpose of triangulating evidence is to establish credibility through a convergence of evidence. Corroboration of findings across data sets reduces the possibility of bias, by examining data gathered in different ways.

It is important to note that document analysis differs from content analysis as content analysis refers to more than documents. As part of their definition for content analysis, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health states that, “Sources of data could be from interviews, open-ended questions, field research notes, conversations, or literally any occurrence of communicative language (such as books, essays, discussions, newspaper headlines, speeches, media, historical documents).

How Do You Do Document Analysis?

In order for a researcher to obtain reliable results from document analysis, a detailed planning process must be undertaken. The following is an outline of an eight-step planning process that should be employed in all textual analysis including document analysis techniques.

- Identify the texts you want to analyze such as samples, population, participants, and respondents.

- You should consider how texts will be accessed, paying attention to any cultural or linguistic barriers.

- Acknowledge and resolve biases.

- Acquire appropriate research skills.

- Strategize for ensuring credibility.

- Identify the data that is being sought.

- Take into account ethical issues.

- Keep a backup plan handy.

Researchers can use a wide variety of texts as part of their research, but the most common source is likely to be written material. Researchers often ask how many documents they should collect. There is an opinion that a wide selection of documents is preferable, but the issue should probably revolve more around the quality of the document than its quantity.

Why is Document Analysis Useful?

Different types of documents serve different purposes. They provide background information, indicate potential interview questions, serve as a mechanism for monitoring progress and tracking changes within a project, and allow for verification of any claims or progress made.

You can triangulate your claims about the phenomenon being studied using document analysis by using multiple sources and other research gathering methods.

Below are the advantages and disadvantages of document analysis

- Document analysis may assist researchers in determining what questions to ask your interviewees, as well as provide insight into what to watch out for during your participant observation.

- It is particularly useful to researchers who wish to focus on specific case studies

- It is inexpensive and quick in cases where data is easily obtainable.

- Documents provide specific and reliable data, unaffected by researchers' presence unlike with other research methods like participant observation.

Disadvantages

- It is likely that the documents researchers obtain are not complete or written objectively, requiring researchers to adopt a critical approach and not assume their contents are reliable or unbiased.

- There may be a risk of information overload due to the number of documents involved. Researchers often have difficulties determining what parts of each document are relevant to the topic being studied.

- It may be necessary to anonymize documents and compare them with other documents.

How NVivo Can Help with Document Analysis

Analyzing copious amounts of data and information can be a daunting and time-consuming prospect. Luckily, qualitative data analysis tools like NVivo can help!

NVivo’s AI-powered autocoding text analysis tool can help you efficiently analyze data and perform thematic analysis . By automatically detecting, grouping, and tagging noun phrases, you can quickly identify key themes throughout your documents – aiding in your evaluation.

Additionally, once you start coding part of your data, NVivo’s smart coding can take care of the rest for you by using machine learning to match your coding style. After your initial coding, you can run queries and create visualizations to expand on initial findings and gain deeper insights.

These features allow you to conduct data analysis on large amounts of documents – improving the efficiency of this qualitative research method. Learn more about these features in the webinar, NVivo 14: Thematic Analysis Using NVivo.

>> Watch Webinar NVivo 14: Thematic Analysis Using NVivo

Learn More About Document Analysis

Watch Twenty-Five Qualitative Researchers Share How-To's for Data Analysis

Recent Articles

Document analysis in health policy research: the READ approach

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, 615 N. Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA.

- 2 Institute for Global Health, University College London, Institute for Global Health 3rd floor, 30 Guilford Street, London WC1N 1EH, UK.

- 3 School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Information Technology University, Arfa Software Technology Park, Ferozepur Road, Lahore 54000, Pakistan.

- 4 Heidelberg Institute of Global Health, Medical Faculty and University Hospital, University of Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 130/3, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany.

- PMID: 33175972

- PMCID: PMC7886435

- DOI: 10.1093/heapol/czaa064

Document analysis is one of the most commonly used and powerful methods in health policy research. While existing qualitative research manuals offer direction for conducting document analysis, there has been little specific discussion about how to use this method to understand and analyse health policy. Drawing on guidance from other disciplines and our own research experience, we present a systematic approach for document analysis in health policy research called the READ approach: (1) ready your materials, (2) extract data, (3) analyse data and (4) distil your findings. We provide practical advice on each step, with consideration of epistemological and theoretical issues such as the socially constructed nature of documents and their role in modern bureaucracies. We provide examples of document analysis from two case studies from our work in Pakistan and Niger in which documents provided critical insight and advanced empirical and theoretical understanding of a health policy issue. Coding tools for each case study are included as Supplementary Files to inspire and guide future research. These case studies illustrate the value of rigorous document analysis to understand policy content and processes and discourse around policy, in ways that are either not possible using other methods, or greatly enrich other methods such as in-depth interviews and observation. Given the central nature of documents to health policy research and importance of reading them critically, the READ approach provides practical guidance on gaining the most out of documents and ensuring rigour in document analysis.

Keywords: Health policy; health systems research; interdisciplinary; methods; policy; policy analysis; policy research; qualitative; research methods; social sciences.

© The Author(s) 2020. Published by Oxford University Press in association with The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- Health Policy*

- Policy Making

- Qualitative Research

Monday, January 20, 2020

A QDA recipe? A ten-step approach for qualitative document analysis using MAXQDA

Guest post by Professional MAXQDA Trainer Dr. Daniel Rasch .

Introduction

Qualitative text or document analysis has evolved into one of the most used qualitative methods across several disciplines ( Kuckartz, 2014 & Mayring, 2010). Its straightforward structure and procedure enable the researcher to adapt the method to his or her special case – nearly to every need.

This article proposes a recipe of ten simple steps for conducting qualitative document analyses (QDA) using MAXQDA (see table 1 for an overview).

Table 1: Overview of the “QDA recipe”

The ten steps for conducting qualitative document analyses using MAXQDA

Step 1: the research question(s).

As always, research begins with the question(s). Three aspects should be covered when dealing with the research question(s):

- What do you want to find out exactly,

- what relevance does your research on this exact question have, and

- what contribution is your research going to make to your discipline?

Highlight these questions in your introduction and make your research stand out.

Step 2: Data collection and data sampling

After you have decided on the questions, you should think about how to answer them. What kind of qualitative data will best answer your question? Interviews – how many and with whom? Documents – which ones and where to collect them from?

At this point, you can already start thinking about validity: are you going to use a representative or a biased sample? Check the different options for sampling and its effects on validity ( Krippendorff, 2019 ).

Step 3: Select and prepare the data

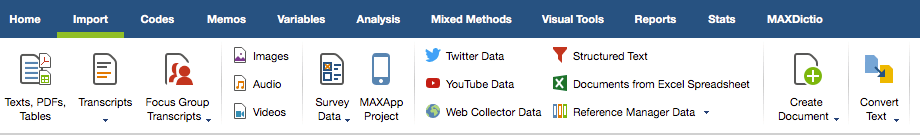

For this step, MAXQDA 2020 is an excellent tool to help you prepare the selected data for any further steps . Whatever type of qualitative data you choose, you can import it into MAXQDA and then you can have MAXQDA assist in transcribing it. In the end, qualitative document analysis is all about written forms of communication (Kuckartz, 2014).

Figure 1: Import the data you have chosen or selected

Step 4: Codebook development

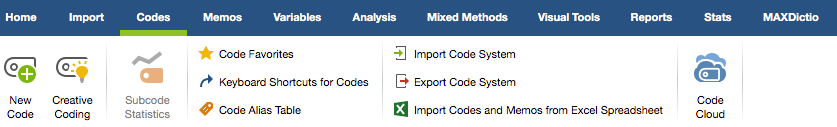

It takes time to develop a solid codebook. Working deductively, the process is a little easier with codes deriving from the theoretical considerations in the context of your research. Inductively, there are various steps you can use, ranging from creative coding to in-vivo-codes.

Content-wise, you can apply all sorts of codes, such as themes or evaluations, two of the most commonly used styles of content analysis (see thematic and evaluative content analysis in Kuckartz, 2014).

Figure 2: coding options in MAXQDA

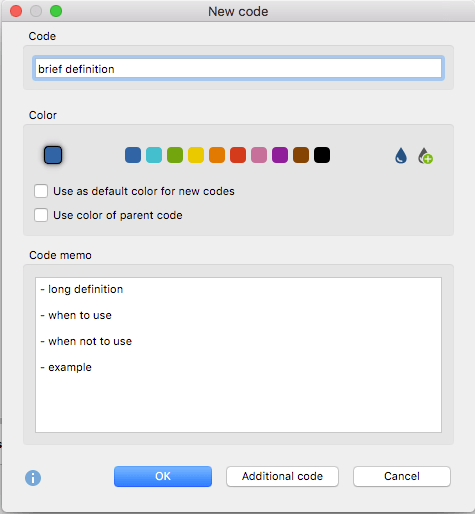

- a brief definition,

- a long definition,

- criteria for when to use the code,

- criteria for when not to use the code, and

- an example.

Using MAXQDA’s code memos simplify the process of creating and maintaining a good codebook . First, you can always go back to the codes and view and review your codebook within your project, and second, you can simply export the codebook as an attachment or appendix for publication purposes (use: Reports > Codebook ).

Figure 3: Creating a new code with code memo

Step 5: Unitizing and coding instructions

Before the process of coding starts, it is necessary to decide on the units of, as well as the rules for, coding. It is especially important to decide on your unit of coding (sentences, paragraphs, quasi-sentences, etc.). Coding rules help to keep this choice consistent and support you to stick to your research question(s) because every passage you code and every memo you write should be done in order to answer your research question(s). Decision rules should be added: what are you going to do if a passage does not fit in your subcodes but should be coded because it is important for your research question?

Step 6: Trial, training, reliability

Trial runs are of major importance. Not only do they show you, which codes work and which do not, but they also help you to rethink your choices in terms of the unit of coding, the content of the codebook, and reliability. Since there are different options for the latter, stick to what works best for you: either a qualitative comparison of what you have coded or quantitative indicators like Krippendorff’s alpha if need be .

You can test yourself or a team you work with and there might even be some situations, where a reliability test is not helpful or needed. When testing the codebook, be sure to test the variability of your collected documents and be sure that the entire codebook is tested.

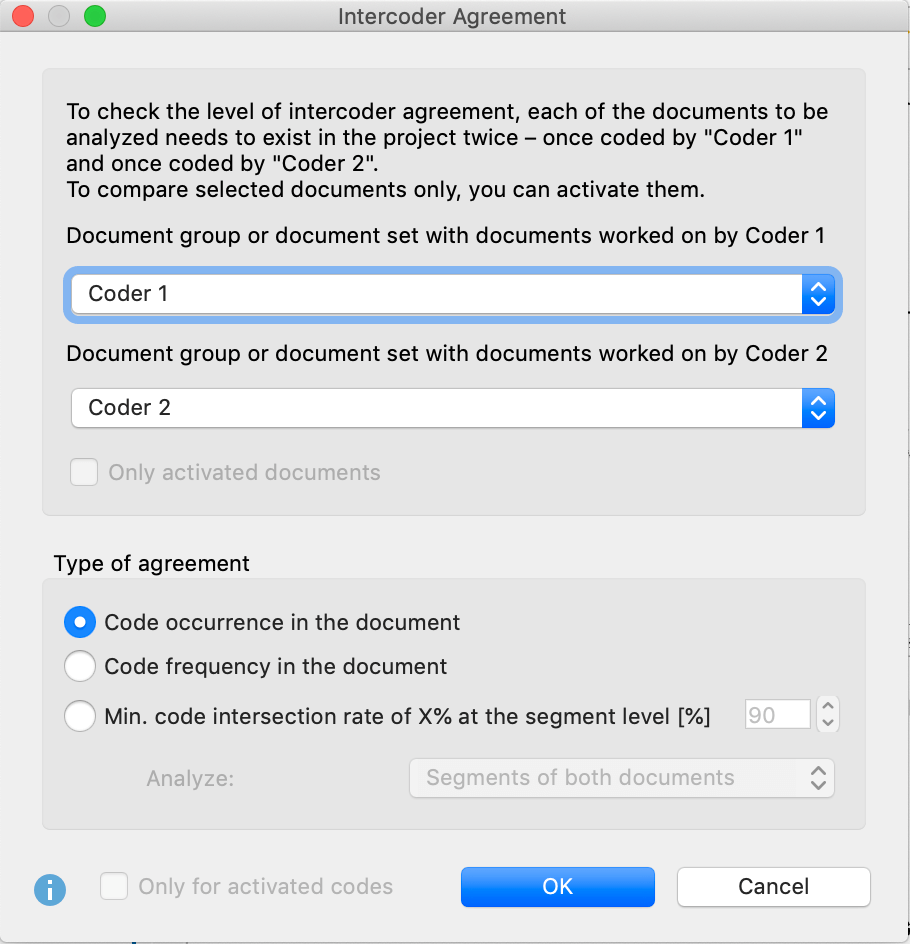

MAXQDA helps you compare different forms of agreement for more an unlimited number of texts, divided into two different document groups (one document group coded by coder 1, a second document group coded by coder 2 – be aware, that you can also test yourself and be coder 2 yourself).

Figure 4: Intercoder agreement

Step 7: Revision and modification

After checking, which codes work and which do not, you can revise the codebook and modify it. As Schreier puts it: “No coding frame (codebook – DR) is perfect” (Schreier, 2012: 147).

Step 8: Coding

There are many different coding strategies, but one thing is for sure: qualitative work needs time and reading, as well as working with the material over and over again.

One coding strategy might be to first make yourself comfortable with the documents and start coding after second or third reading only. Another strategy is to concentrate on some of your codes first and do a second round of coding with the other codes later.

Step 9: Analyze and compare

Analyze and compare – these two words are the essence of the qualitative analysis at this step. At the core of each qualitative document analysis is the description of the content and the comparison of these contents between the documents you analyze.

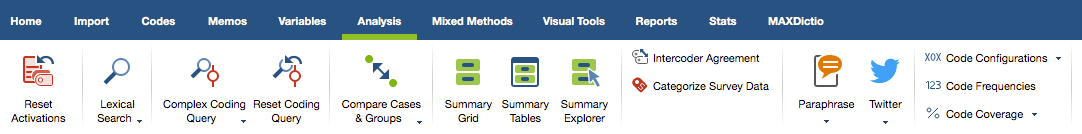

After everything has been coded, you can make use of different analysis strategies: paraphrase, write summaries, look for intersections of codes, patterns of likeliness between the documents using simple or complex queries.

Figure 5: different analysis strategies in MAXQDA

Step 10: Interpretation and presentation

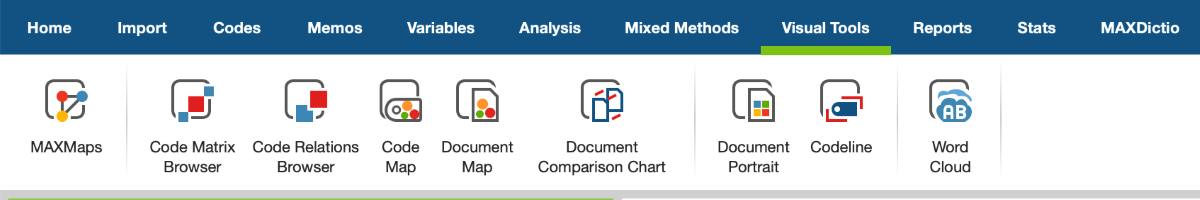

Reporting and summarizing qualitative findings is difficult. Most often, we find simple descriptions of the content with the use of quotations, paraphrases or other references to the text. However, MAXQDA makes it fast and easier with many options to choose from . The easiest way is to generate a table to sum up your findings – if your data or the findings allow for this.

MAXQDA offers several options: either map relations of codes, documents or memos with the MAXMaps , create matrices between codes and documents ( Code Matrix Browser ) or codes and codes ( Code Relations Browser ) to display the distribution of codes inside your data or even using different colors to map the distribution of codes or single documents.

Figure 6: Visual Tools for presentation

The Code Matrix Browser also enables you to quantify the qualitative data using two clicks. You can export these numbers for further analysis with statistical packages, to run causal relation and effect calculations, such as regressions or correlations ( Rasch, 2018 ).

Summary and adoption

Qualitative document analysis is one of the most popular techniques and adaptable to nearly every field. MAXQDA is a software tool that offers many options to make your analysis and therefore your research easier .

The recipe works best for theory-driven, deductive coding. However, it can be also used for inductive, explorative work by switching some of these steps around: for example, your codebook development might be one step to do during or after the trial and testing, since codes are developed inductively during the coding process. Still, it is important to define these codes properly.

The above-mentioned recipe has been used as a basis for several publications by the author. Starting with simple comparison of qualitative and quantitative text analysis ( Boräng et al., 2014 ), to the usage of the qualitative data as a basis for regression models ( Eising et al., 2015 ; Eising et al., 2017 ) to a book using mixed methods and therefore both qualitative and quantitative data analysis ( Rasch, 2018 ).

About the author

Daniel Rasch is a post-doctoral researcher in political science at the German University of Administrative Sciences, Speyer. He received his Ph.D. with a mixed methods analysis of lobbyists‘ success in the European Union. He focuses on the quantification of qualitative data. He is an experienced MAXQDA lecturer and has been a Professional MAXQDA Trainer since 2012.

MAXQDA Newsletter

Our research and analysis tips, straight to your inbox.

Similar Articles

- #ResearchforChange Grants (46)

- Conferences & Events (32)

- Field Work Diary (39)

- Learning MAXQDA (110)

- Research Projects (132)

- Tip of the Month (57)

- Uncategorized (9)

- Updates (65)

- VERBI News (71)

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Open Access Articles

- Research Collections

- Review Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Health Policy and Planning

- About the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- HPP at a glance

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, what is document analysis, the read approach, supplementary data, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Document analysis in health policy research: the READ approach

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

Sarah L Dalglish, Hina Khalid, Shannon A McMahon, Document analysis in health policy research: the READ approach, Health Policy and Planning , Volume 35, Issue 10, December 2020, Pages 1424–1431, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa064

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Document analysis is one of the most commonly used and powerful methods in health policy research. While existing qualitative research manuals offer direction for conducting document analysis, there has been little specific discussion about how to use this method to understand and analyse health policy. Drawing on guidance from other disciplines and our own research experience, we present a systematic approach for document analysis in health policy research called the READ approach: (1) ready your materials, (2) extract data, (3) analyse data and (4) distil your findings. We provide practical advice on each step, with consideration of epistemological and theoretical issues such as the socially constructed nature of documents and their role in modern bureaucracies. We provide examples of document analysis from two case studies from our work in Pakistan and Niger in which documents provided critical insight and advanced empirical and theoretical understanding of a health policy issue. Coding tools for each case study are included as Supplementary Files to inspire and guide future research. These case studies illustrate the value of rigorous document analysis to understand policy content and processes and discourse around policy, in ways that are either not possible using other methods, or greatly enrich other methods such as in-depth interviews and observation. Given the central nature of documents to health policy research and importance of reading them critically, the READ approach provides practical guidance on gaining the most out of documents and ensuring rigour in document analysis.

Rigour in qualitative research is judged partly by the use of deliberate, systematic procedures; however, little specific guidance is available for analysing documents, a nonetheless common method in health policy research.

Document analysis is useful for understanding policy content across time and geographies, documenting processes, triangulating with interviews and other sources of data, understanding how information and ideas are presented formally, and understanding issue framing, among other purposes.

The READ (Ready materials, Extract data, Analyse data, Distil) approach provides a step-by-step guide to conducting document analysis for qualitative policy research.

The READ approach can be adapted to different purposes and types of research, two examples of which are presented in this article, with sample tools in the Supplementary Materials .

Document analysis (also called document review) is one of the most commonly used methods in health policy research; it is nearly impossible to conduct policy research without it. Writing in early 20th century, Weber (2015) identified the importance of formal, written documents as a key characteristic of the bureaucracies by which modern societies function, including in public health. Accordingly, critical social research has a long tradition of documentary review: Marx analysed official reports, laws, statues, census reports and newspapers and periodicals over a nearly 50-year period to come to his world-altering conclusions ( Harvey, 1990 ). Yet in much of social science research, ‘documents are placed at the margins of consideration,’ with privilege given to the spoken word via methods such as interviews, possibly due to the fact that many qualitative methods were developed in the anthropological tradition to study mainly pre-literate societies ( Prior, 2003 ). To date, little specific guidance is available to help health policy researchers make the most of these wells of information.

The term ‘documents’ is defined here broadly, following Prior, as physical or virtual artefacts designed by creators, for users, to function within a particular setting ( Prior, 2003 ). Documents exist not as standalone objects of study but must be understood in the social web of meaning within which they are produced and consumed. For example, some analysts distinguish between public documents (produced in the context of public sector activities), private documents (from business and civil society) and personal documents (created by or for individuals, and generally not meant for public consumption) ( Mogalakwe, 2009 ). Documents can be used in a number of ways throughout the research process ( Bowen, 2009 ). In the planning or study design phase, they can be used to gather background information and help refine the research question. Documents can also be used to spark ideas for disseminating research once it is complete, by observing the ways those who will use the research speak to and communicate ideas with one another.

Documents can also be used during data collection and analysis to help answer research questions. Recent health policy research shows that this can be done in at least four ways. Frequently, policy documents are reviewed to describe the content or categorize the approaches to specific health problems in existing policies, as in reviews of the composition of drowning prevention resources in the United States or policy responses to foetal alcohol spectrum disorder in South Africa ( Katchmarchi et al. , 2018 ; Adebiyi et al. , 2019 ). In other cases, non-policy documents are used to examine the implementation of health policies in real-world settings, as in a review of web sources and newspapers analysing the functioning of community health councils in New Zealand ( Gurung et al. , 2020 ). Perhaps less frequently, document analysis is used to analyse policy processes, as in an assessment of multi-sectoral planning process for nutrition in Burkina Faso ( Ouedraogo et al. , 2020 ). Finally, and most broadly, document analysis can be used to inform new policies, as in one study that assessed cigarette sticks as communication and branding ‘documents,’ to suggest avenues for further regulation and tobacco control activities ( Smith et al. , 2017 ).

This practice paper provides an overarching method for conducting document analysis, which can be adapted to a multitude of research questions and topics. Document analysis is used in most or all policy studies; the aim of this article is to provide a systematized method that will enhance procedural rigour. We provide an overview of document analysis, drawing on guidance from disciplines adjacent to public health, introduce the ‘READ’ approach to document analysis and provide two short case studies demonstrating how document analysis can be applied.

Document analysis is a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents, which can be used to provide context, generate questions, supplement other types of research data, track change over time and corroborate other sources ( Bowen, 2009 ). In one commonly cited approach in social research, Bowen recommends first skimming the documents to get an overview, then reading to identify relevant categories of analysis for the overall set of documents and finally interpreting the body of documents ( Bowen, 2009 ). Document analysis can include both quantitative and qualitative components: the approach presented here can be used with either set of methods, but we emphasize qualitative ones, which are more adapted to the socially constructed meaning-making inherent to collaborative exercises such as policymaking.

The study of documents as a research method is common to a number of social science disciplines—yet in many of these fields, including sociology ( Mogalakwe, 2009 ), anthropology ( Prior, 2003 ) and political science ( Wesley, 2010 ), document-based research is described as ill-considered and underutilized. Unsurprisingly, textual analysis is perhaps most developed in fields such as media studies, cultural studies and literary theory, all disciplines that recognize documents as ‘social facts’ that are created, consumed, shared and utilized in socially organized ways ( Atkinson and Coffey, 1997 ). Documents exist within social ‘fields of action,’ a term used to designate the environments within which individuals and groups interact. Documents are therefore not mere records of social life, but integral parts of it—and indeed can become agents in their own right ( Prior, 2003 ). Powerful entities also manipulate the nature and content of knowledge; therefore, gaps in available information must be understood as reflecting and potentially reinforcing societal power relations ( Bryman and Burgess, 1994 ).

Document analysis, like any research method, can be subject to concerns regarding validity, reliability, authenticity, motivated authorship, lack of representativity and so on. However, these can be mitigated or avoided using standard techniques to enhance qualitative rigour, such as triangulation (within documents and across methods and theoretical perspectives), ensuring adequate sample size or ‘engagement’ with the documents, member checking, peer debriefing and so on ( Maxwell, 2005 ).

Document analysis can be used as a standalone method, e.g. to analyse the contents of specific types of policy as they evolve over time and differ across geographies, but document analysis can also be powerfully combined with other types of methods to cross-validate (i.e. triangulate) and deepen the value of concurrent methods. As one guide to public policy research puts it, ‘almost all likely sources of information, data, and ideas fall into two general types: documents and people’ ( Bardach and Patashnik, 2015 ). Thus, researchers can ask interviewees to address questions that arise from policy documents and point the way to useful new documents. Bardach and Patashnik suggest alternating between documents and interviews as sources as information, as one tends to lead to the other, such as by scanning interviewees’ bookshelves and papers for titles and author names ( Bardach and Patashnik, 2015 ). Depending on your research questions, document analysis can be used in combination with different types of interviews ( Berner-Rodoreda et al. , 2018 ), observation ( Harvey, 2018 ), and quantitative analyses, among other common methods in policy research.

The READ approach to document analysis is a systematic procedure for collecting documents and gaining information from them in the context of health policy studies at any level (global, national, local, etc.). The steps consist of: (1) ready your materials, (2) extract data, (3) analyse data and (4) distil your findings. We describe each of these steps in turn.

Step 1. Ready your materials

At the outset, researchers must set parameters in terms of the nature and number (approximately) of documents they plan to analyse, based on the research question. How much time will you allocate to the document analysis, and what is the scope of your research question? Depending on the answers to these questions, criteria should be established around (1) the topic (a particular policy, programme, or health issue, narrowly defined according to the research question); (2) dates of inclusion (whether taking the long view of several decades, or zooming in on a specific event or period in time); and (3) an indicative list of places to search for documents (possibilities include databases such as Ministry archives; LexisNexis or other databases; online searches; and particularly interview subjects). For difficult-to-obtain working documents or otherwise non-public items, bringing a flash drive to interviews is one of the best ways to gain access to valuable documents.

For research focusing on a single policy or programme, you may review only a handful of documents. However, if you are looking at multiple policies, health issues, or contexts, or reviewing shorter documents (such as newspaper articles), you may look at hundreds, or even thousands of documents. When considering the number of documents you will analyse, you should make notes on the type of information you plan to extract from documents—i.e. what it is you hope to learn, and how this will help answer your research question(s). The initial criteria—and the data you seek to extract from documents—will likely evolve over the course of the research, as it becomes clear whether they will yield too few documents and information (a rare outcome), far too many documents and too much information (a much more common outcome) or documents that fail to address the research question; however, it is important to have a starting point to guide the search. If you find that the documents you need are unavailable, you may need to reassess your research questions or consider other methods of inquiry. If you have too many documents, you can either analyse a subset of these ( Panel 1 ) or adopt more stringent inclusion criteria.

Exploring the framing of diseases in Pakistani media

In Table 1 , we present a non-exhaustive list of the types of documents that can be included in document analyses of health policy issues. In most cases, this will mean written sources (policies, reports, articles). The types of documents to be analysed will vary by study and according to the research question, although in many cases, it will be useful to consult a mix of formal documents (such as official policies, laws or strategies), ‘gray literature’ (organizational materials such as reports, evaluations and white papers produced outside formal publication channels) and, whenever possible, informal or working documents (such as meeting notes, PowerPoint presentations and memoranda). These latter in particular can provide rich veins of insight into how policy actors are thinking through the issues under study, particularly for the lucky researcher who obtains working documents with ‘Track Changes.’ How you prioritize documents will depend on your research question: you may prioritize official policy documents if you are studying policy content, or you may prioritize informal documents if you are studying policy process.

Types of documents that can be consulted in studies of health policy

During this initial preparatory phase, we also recommend devising a file-naming system for your documents (e.g. Author.Date.Topic.Institution.PDF), so that documents can be easily retrieved throughout the research process. After extracting data and processing your documents the first time around, you will likely have additional ‘questions’ to ask your documents and need to consult them again. For this reason, it is important to clearly name source files and link filenames to the data that you are extracting (see sample naming conventions in the Supplementary Materials ).

Step 2. Extract data

Data can be extracted in a number of ways, and the method you select for doing so will depend on your research question and the nature of your documents. One simple way is to use an Excel spreadsheet where each row is a document and each column is a category of information you are seeking to extract, from more basic data such as the document title, author and date, to theoretical or conceptual categories deriving from your research question, operating theory or analytical framework (Panel 2). Documents can also be imported into thematic coding software such as Atlas.ti or NVivo, and data extracted that way. Alternatively, if the research question focuses on process, documents can be used to compile a timeline of events, to trace processes across time. Ask yourself, how can I organize these data in the most coherent manner? What are my priority categories? We have included two different examples of data extraction tools in the Supplementary Materials to this article to spark ideas.

Case study Documents tell part of the story in Niger

Document analyses are first and foremost exercises in close reading: documents should be read thoroughly, from start to finish, including annexes, which may seem tedious but which sometimes produce golden nuggets of information. Read for overall meaning as you extract specific data related to your research question. As you go along, you will begin to have ideas or build working theories about what you are learning and observing in the data. We suggest capturing these emerging theories in extended notes or ‘memos,’ as used in Grounded Theory methodology ( Charmaz, 2006 ); these can be useful analytical units in themselves and can also provide a basis for later report and article writing.

As you read more documents, you may find that your data extraction tool needs to be modified to capture all the relevant information (or to avoid wasting time capturing irrelevant information). This may require you to go back and seek information in documents you have already read and processed, which will be greatly facilitated by a coherent file-naming system. It is also useful to keep notes on other documents that are mentioned that should be tracked down (sometimes you can write the author for help). As a general rule, we suggest being parsimonious when selecting initial categories to extract from data. Simply reading the documents takes significant time in and of itself—make sure you think about how, exactly, the specific data you are extracting will be used and how it goes towards answering your research questions.

Step 3. Analyse data

As in all types of qualitative research, data collection and analysis are iterative and characterized by emergent design, meaning that developing findings continually inform whether and how to obtain and interpret data ( Creswell, 2013 ). In practice, this means that during the data extraction phase, the researcher is already analysing data and forming initial theories—as well as potentially modifying document selection criteria. However, only when data extraction is complete can one see the full picture. For example, are there any documents that you would have expected to find, but did not? Why do you think they might be missing? Are there temporal trends (i.e. similarities, differences or evolutions that stand out when documents are ordered chronologically)? What else do you notice? We provide a list of overarching questions you should think about when viewing your body of document as a whole ( Table 2 ).

Questions to ask your overall body of documents

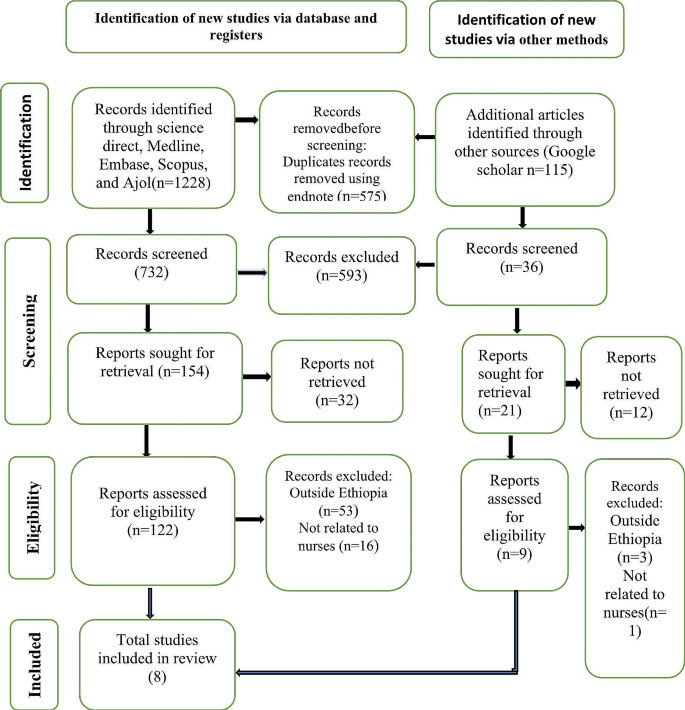

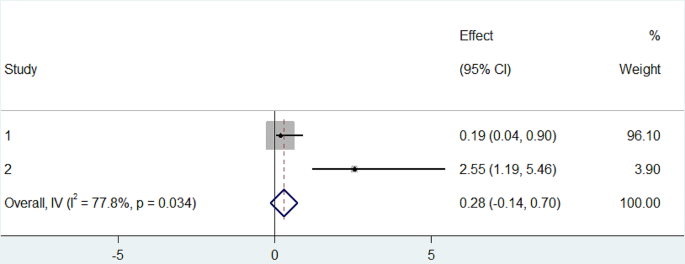

HIV and viral hepatitis articles by main frames (%). Note: The percentage of articles is calculated by dividing the number of articles appearing in each frame for viral hepatitis and HIV by the respectivenumber of sampled articles for each disease (N = 137 for HIV; N = 117 for hepatitis). Time frame: 1 January 2006 to 30 September 2016

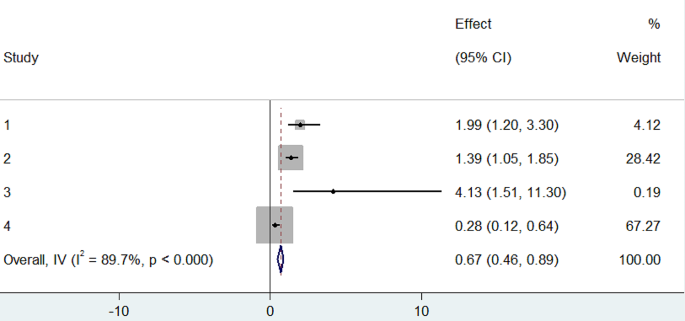

Representations of progress toward Millennium Development Goal 4 in Nigerien policy documents. Sources: clockwise from upper left: ( WHO 2006 ); ( Institut National de la Statistique 2010 ); ( Ministè re de la Santé Publique 2010 ); ( Unicef 2010 )

In addition to the meaning-making processes you are already engaged in during the data extraction process, in most cases, it will be useful to apply specific analysis methodologies to the overall corpus of your documents, such as policy analysis ( Buse et al. , 2005 ). An array of analysis methodologies can be used, both quantitative and qualitative, including case study methodology, thematic content analysis, discourse analysis, framework analysis and process tracing, which may require differing levels of familiarity and skills to apply (we highlight a few of these in the case studies below). Analysis can also be structured according to theoretical approaches. When it comes to analysing policies, process tracing can be particularly useful to combine multiple sources of information, establish a chronicle of events and reveal political and social processes, so as to create a narrative of the policy cycle ( Yin, 1994 ; Shiffman et al. , 2004 ). Practically, you will also want to take a holistic view of the documents’ ‘answers’ to the questions or analysis categories you applied during the data extraction phase. Overall, what did the documents ‘say’ about these thematic categories? What variation did you find within and between documents, and along which axes? Answers to these questions are best recorded by developing notes or memos, which again will come in handy as you write up your results.

As with all qualitative research, you will want to consider your own positionality towards the documents (and their sources and authors); it may be helpful to keep a ‘reflexivity’ memo documenting how your personal characteristics or pre-standing views might influence your analysis ( Watt, 2007 ).

Step 4. Distil your findings

You will know when you have completed your document review when one of the three things happens: (1) completeness (you feel satisfied you have obtained every document fitting your criteria—this is rare), (2) out of time (this means you should have used more specific criteria), and (3) saturation (you fully or sufficiently understand the phenomenon you are studying). In all cases, you should strive to make the third situation the reason for ending your document review, though this will not always mean you will have read and analysed every document fitting your criteria—just enough documents to feel confident you have found good answers to your research questions.

Now it is time to refine your findings. During the extraction phase, you did the equivalent of walking along the beach, noticing the beautiful shells, driftwood and sea glass, and picking them up along the way. During the analysis phase, you started sorting these items into different buckets (your analysis categories) and building increasingly detailed collections. Now you have returned home from the beach, and it is time to clean your objects, rinse them of sand and preserve only the best specimens for presentation. To do this, you can return to your memos, refine them, illustrate them with graphics and quotes and fill in any incomplete areas. It can also be illuminating to look across different strands of work: e.g. how did the content, style, authorship, or tone of arguments evolve over time? Can you illustrate which words, concepts or phrases were used by authors or author groups?

Results will often first be grouped by theoretical or analytic category, or presented as a policy narrative, interweaving strands from other methods you may have used (interviews, observation, etc.). It can also be helpful to create conceptual charts and graphs, especially as this corresponds to your analytical framework (Panels 1 and 2). If you have been keeping a timeline of events, you can seek out any missing information from other sources. Finally, ask yourself how the validity of your findings checks against what you have learned using other methods. The final products of the distillation process will vary by research study, but they will invariably allow you to state your findings relative to your research questions and to draw policy-relevant conclusions.

Document analysis is an essential component of health policy research—it is also relatively convenient and can be low cost. Using an organized system of analysis enhances the document analysis’s procedural rigour, allows for a fuller understanding of policy process and content and enhances the effectiveness of other methods such as interviews and non-participant observation. We propose the READ approach as a systematic method for interrogating documents and extracting study-relevant data that is flexible enough to accommodate many types of research questions. We hope that this article encourages discussion about how to make best use of data from documents when researching health policy questions.

Supplementary data are available at Health Policy and Planning online.

The data extraction tool in the Supplementary Materials for the iCCM case study (Panel 2) was conceived of by the research team for the multi-country study ‘Policy Analysis of Community Case Management for Childhood and Newborn Illnesses’. The authors thank Sara Bennett and Daniela Rodriguez for granting permission to publish this tool. S.M. was supported by The Olympia-Morata-Programme of Heidelberg University. The funders had no role in the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of any funder.

Conflict of interest statement . None declared.

Ethical approval. No ethical approval was required for this study.

Abdelmutti N , Hoffman-Goetz L. 2009 . Risk messages about HPV, cervical cancer, and the HPV vaccine Gardasil: a content analysis of Canadian and U.S. national newspaper articles . Women & Health 49 : 422 – 40 .

Google Scholar

Adebiyi BO , Mukumbang FC , Beytell A-M. 2019 . To what extent is fetal alcohol spectrum disorder considered in policy-related documents in South Africa? A document review . Health Research Policy and Systems 17 :

Atkinson PA , Coffey A. 1997 . Analysing documentary realities. In: Silverman D (ed). Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice . London : SAGE .

Google Preview

Bardach E , Patashnik EM. 2015 . Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving . Los Angeles : SAGE .

Bennett S , Dalglish SL , Juma PA , Rodríguez DC. 2015 . Altogether now… understanding the role of international organizations in iCCM policy transfer . Health Policy and Planning 30 : ii26 – 35 .

Berner-Rodoreda A , Bärnighausen T , Kennedy C et al. 2018 . From doxastic to epistemic: a typology and critique of qualitative interview styles . Qualitative Inquiry 26 : 291 – 305 . 1077800418810724.

Bowen GA. 2009 . Document analysis as a qualitative research method . Qualitative Research Journal 9 : 27 – 40 .

Bryman A. 1994 . Analyzing Qualitative Data .

Buse K , Mays N , Walt G. 2005 . Making Health Policy . New York : Open University Press .

Charmaz K. 2006 . Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis . London : SAGE .

Claassen L , Smid T , Woudenberg F , Timmermans DRM. 2012 . Media coverage on electromagnetic fields and health: content analysis of Dutch newspaper articles and websites . Health, Risk & Society 14 : 681 – 96 .

Creswell JW. 2013 . Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design . Thousand Oaks, CA : SAGE .

Dalglish SL , Rodríguez DC , Harouna A , Surkan PJ. 2017 . Knowledge and power in policy-making for child survival in Niger . Social Science & Medicine 177 : 150 – 7 .

Dalglish SL , Surkan PJ , Diarra A , Harouna A , Bennett S. 2015 . Power and pro-poor policies: the case of iCCM in Niger . Health Policy and Planning 30 : ii84 – 94 .

Entman RM. 1993 . Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm . Journal of Communication 43 : 51 – 8 .

Fournier G , Djermakoye IA. 1975 . Village health teams in Niger (Maradi Department). In: Newell KW (ed). Health by the People . Geneva : WHO .

Gurung G , Derrett S , Gauld R. 2020 . The role and functions of community health councils in New Zealand’s health system: a document analysis . The New Zealand Medical Journal 133 : 70 – 82 .

Harvey L. 1990 . Critical Social Research . London : Unwin Hyman .

Harvey SA. 2018 . Observe before you leap: why observation provides critical insights for formative research and intervention design that you’ll never get from focus groups, interviews, or KAP surveys . Global Health: Science and Practice 6 : 299 – 316 .

Institut National de la Statistique. 2010. Rapport National sur les Progrès vers l'atteinte des Objectifs du Millénaire pour le Développement. Niamey, Niger: INS.

Kamarulzaman A. 2013 . Fighting the HIV epidemic in the Islamic world . Lancet 381 : 2058 – 60 .

Katchmarchi AB , Taliaferro AR , Kipfer HJ. 2018 . A document analysis of drowning prevention education resources in the United States . International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion 25 : 78 – 84 .

Krippendorff K. 2004 . Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology . SAGE .

Marten R. 2019 . How states exerted power to create the Millennium Development Goals and how this shaped the global health agenda: lessons for the sustainable development goals and the future of global health . Global Public Health 14 : 584 – 99 .

Maxwell JA. 2005 . Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach , 2 nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage Publications .