Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 14, Issue 5

- How to manage alcohol-related liver disease: A case-based review

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1530-5328 James B Maurice 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5140-517X Samuel Tribich 2 ,

- Ava Zamani 3 ,

- Jennifer Ryan 4

- 1 Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Southmead Hospital , North Bristol NHS Trust , Bristol , UK

- 2 Department of Hepatology, Royal London Hospital , Barts Health NHS Trust , London , UK

- 3 Hammersmith Hospital , Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust , London , UK

- 4 Department of Hepatology and Liver Transplantation, Royal Free Hospital , Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr James B Maurice, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Southmead Hospital, North Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol BS10 5NB, UK; james.maurice{at}nbt.nhs.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/flgastro-2022-102270

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- alcoholic liver disease

- chronic liver disease

What is already known on this topic

Alcohol-related liver disease (ArLD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality.

What this study adds

We present a typical case to illustrate current evidence-based investigation and management of a patient with ArLD.

This case-based review aims to concisely support the day-to-day decision making of clinicians looking after patients with ArLD, from risk stratification and fibrosis assessment in the community through to managing decompensated disease, escalation care to critical care and assessment for liver transplantation.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy

We summarise the evolving evidence for the benefit of liver transplantation in alcoholic hepatitis, and ongoing controversies shaping future research in this area.

ArLD is fundamentally a public health problem, and further efforts are required to implement effective policies to reduce consumption and prevent disease.

Introduction

Alcohol is the leading risk factor for premature death in young adults, of which alcohol-related liver disease (ArLD) is a major contributor. 1 The management of ArLD often requires complex decision-making, raising challenges for the clinician and wider multidisciplinary team. This case-based review follows the typical journey of a patient through the progressive stages of the disease process, from early diagnosis and risk stratification in the outpatient clinic through to alcoholic hepatitis and referral for liver transplantation. At each stage, we discuss a practical approach to clinical management and summarise the underlying evidence base.

Case part 1

A 47-year-old man is referred to the general hepatology clinic from his General Practitioner with abnormal liver function tests, ordered in the community following several episodes of non-specific abdominal pain which subsequently resolved. He is now asymptomatic. The referral states that he drinks one bottle of wine each weekday night and more at the weekends. He is on no regular medication, has no other significant medical history and works in construction. On clinical examination, there are a few spider naevi on the chest wall but no other stigmata of liver disease, and his body mass index is 26 kg/m 2 . The blood results show alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 65 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 92 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 100 IU/L, gamma-GT (GGT) 350 IU/L, bilirubin 15 µmol/L, albumin 45 g/L, platelets 256×10 9 /L, internation normalised ratio (INR) 1.0 and creatinine 50 µmol/L. Abdominal ultrasound reveals a mildly enlarged, hyperechoic liver but normal spleen and no ascites.

How can we risk-stratify patients with ArLD in the outpatient clinic?

Early diagnosis and risk stratification of patients enables appropriate selection of patients for follow-up in secondary care, while also providing an opportunity for preventative interventions in those with mild disease. Emergency admissions for hepatic decompensation, where up to 75% of patients present for the first time, represent a late stage of the disease process when 1-year mortality is very high. 2 It is therefore vital to make an early diagnosis of liver disease.

Hepatic fibrosis has been traditionally staged by liver biopsy; however, non-invasive methods of fibrosis staging have an emerging role in ArLD. Transient elastography (TE) has been validated against liver biopsy to accurately stage both advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, 3–6 and current NICE guidance recommends TE for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in patients with ArLD.

Serological markers of fibrosis such as FIB-4 and AST-Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) have generally not performed well in ArLD, although the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) test, measuring direct markers of fibrosis in blood, has an Area Under the Receiver Operator Curve (AUROC) of 0.92 in diagnosing advanced fibrosis using a cut-off value of 10.5. 7

How can we screen for alcohol use disorder and ArLD?

The primary screening tools for alcohol use disorders are the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or abbreviated AUDIT-C questionnaires. 8 Although clear documentation of the amount of alcohol consumed is important, a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder is more nuanced than volume of alcohol alone, hence the improved sensitivity through use of validated questionnaires. Identifying increasing risk (AUDIT 8–15), higher risk (AUDIT 16–19) or possible dependence (AUDIT≥20) 8 provides an opportunity for targeted brief interventions in those who would most benefit and is a cost-effective method for reducing alcohol intake. 9 Typically only comprising a 5–20 min single interaction, brief interventions offer personalised advice using a motivational and empathetic style of interview ( Box 1 ). If delivered to all new patients registered in primary care, this could save 2500 alcohol-related deaths over 20 years. 10 Patients identified to have alcohol dependence through screening should be referred for specialist treatment.

Typical features of brief interventions

Feedback on the person’s alcohol use and any related harm.

Clarification as to what constitutes low-risk consumption.

Information on the harms associated with risky alcohol use.

Benefits of reducing intake.

Motivational enhancement to support change.

Analysis of high-risk situations for drinking.

Coping strategies and the development of a personal plan to reduce consumption.

Adapted from Public Health England Review: the public health burden of alcohol and the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies. An evidence review. 45

Although routine blood tests may be helpful in supporting a diagnosis of ArLD (eg, AST>ALT, increased GGT, macrocytosis), they are of limited value in determining the severity of liver disease before established cirrhosis has developed with impaired liver synthetic function (low albumin, high INR and bilirubin). Individuals drinking at harmful levels should be screened for liver fibrosis with TE. Hepatology referral should be considered in patients with TE 8–16 kPa, particularly in those who continue to drink at harmful levels. Patients with TE≥16 kPa are at high risk of developing complications of cirrhosis, therefore should be followed up in a specialist hepatology clinic and be screened for hepatocellular carcinoma and oesophageal varices. Screening endoscopy for varices should be offered when TE≥20 kPa or platelets≤150×10 9 /L. 11 In the primary care setting, fibrosis screening of individuals drinking at harmful levels may alternatively be done with the ELF test, although this is not uniformly available ( figure 1 ). 12

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Screening for cirrhosis in individuals drinking at hazardous and harmful levels. ARFI, Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; AUDIT-C, abbreviated Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; ELF, enhanced liver fibrosis; GGT, Gamma-GT; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NICE, The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Reproduced with permission from Newsome et al . 46

A high-risk population that should be considered for ArLD screening are the patients admitted to hospital acutely with alcohol-related physical harm, such as acute alcohol withdrawal or alcohol-related trauma. These patients should all be referred to alcohol care teams, and in addition to their expertise in delivering brief interventions, tailored detoxification regimens and vital links to local alcohol support services in the community, some hospitals have trained to perform TE and screen for liver fibrosis. This has provided an opportunity to streamline at risk patients into the hepatology services.

Case part 2

The same patient presents on the acute medical take 1 year later with a 2-week history of jaundice and abdominal swelling. Unfortunately, he has continued drinking alcohol. On examination, he is jaundiced with moderate ascites, tender hepatomegaly and subtle asterixis. He is sarcopenic with arm muscle wasting. He has the following blood results: haemoglobin 100 g/L, mean cell volume 107 fL, white cell count 12×10 9 /L, platelets 135×10 9 /L, INR 2.3, sodium 132 mmol/L, potassium 3.0 mmol/L, creatinine 55 µmol/L, urea 2.0 µmol/L, bilirubin 250 µmol/L, ALT 25 IU/L, AST 60 IU/L, ALP 95 IU/L, GGT 200 IU/L, albumin 35 g/L, c-reative protein (CRP) 45 mg/L. A diagnostic paracentesis reveals an ascitic albumin 16 g/L, white cells 90/mm 3 (80% lymphocytes). An X-ray of the chest is normal. Ultrasound liver demonstrates hepatomegaly 17 cm, splenomegaly 15 cm, moderate ascites and a patent portal vein. A clinical diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is made.

What is the role of liver biopsy in the diagnosis of AH?

AH is a clinical syndrome characterised by jaundice and coagulopathy in the context of recent and prolonged heavy alcohol use. Rapid development of jaundice is accompanied by a systemic inflammatory response with constitutional symptoms and low-grade fever, with or without other features of decompensation.

The diagnosis of AH can be made using a standard consensus definition based on clinical and biochemical parameters ( table 1 ), originally established to allow inclusion in clinical trials without the need for a liver biopsy but now generalised to clinical practice. 13 Neither European Association for the Study of Liver Disease (EASL) nor American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines recommend liver biopsy in patients meeting the criteria for probable AH, 9 10 and these recommendations have been supported by more recent data, showing that liver biopsy rarely changes the diagnosis when clinical criteria are met for AH. 12 However, if diagnostic uncertainty remains, such as atypical biochemical markers, uncertain alcohol use or a suspected alternative cause of liver injury, a liver biopsy should be undertaken to confirm the diagnosis, particularly if planning to administer AH-directed medical therapies. 14

- View inline

Consensus definition for ‘probable’ alcohol hepatitis 13

In those patients in whom a biopsy is undertaken, specific histological features such as degree of neutrophil infiltration, fibrosis stage and presence of megamitochondria can be useful for prognostication using the Alcoholic Hepatitis Histologic Score, which is independently predictive of 90-day mortality. 15 However, the utility of this is significantly limited by interobserver variability between reporting pathologists. 16

Should this patient be treated with steroids?

Once a diagnosis of AH is established, patients should be risk stratified using a validated scoring system. The modified Maddrey’s discriminant function (mDF) is a commonly used score, which defines a cut-off of ≥32 as severe AH; however, this is very sensitive and risks over-treating patients with mild disease. 17 The Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS) and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) are better predictors of 28-day and 90-day mortality than mDF 18 19 and are also now included in EASL and ACG guidelines, with severe AH defined as GAHS≥9 or MELD≥21. 20 , 14

The STeroids Or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH) study is the largest randomised controlled trial to investigate the efficacy of corticosteroids in the treatment of AH. It included 1103 participants with severe AH and the group that received prednisolone only had a small non-significant improvement in 28-day survival (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.01, p=0.06), a benefit which was lost by 90 days and 1 year. In the multivariate analysis adjusting for baseline variables, prednisolone was associated with improved 28-day survival compared with placebo (OR 0.61, p=0.015), although not at 90 days or 1 year. 21 Further meta-analyses of pooled data have replicated these findings. 22

The EASL and ACG guidelines advise to take steroid treatment with prednisolone 40 mg per day in patients with severe AH, as defined by either the mDF, GAHS or MELD Score. Steroid responsiveness should be assessed using the Lille Score, typically on day 7, although there is data to support earlier application on day 4, 23 with steroids stopped in non-responders (Lille Score≥0.45); responders should complete a 28-day course. It may be possible to predict Lille response using a baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), with an NLR of 5–8 predictive of a significant reduction in 90-day mortality with corticosteroid treatment, compared with no reduction when NLR is less than 5 or more than 8. 24 Emerging data is further delineating which patients may derive the greatest benefit from corticosteroids 25 ; however, this remains an area of ongoing research.

Infection is a frequent complication of severe AH, contributing significantly to the high mortality rate and associated in particular with an increased 90-day mortality. 26 Corticosteroids are associated with an increased incidence of infection post-treatment compared with placebo (10% vs 6%), 21 and significantly worse 90-day mortality if patients develop infection within the first week of starting steroids. 26 Therefore, particular caution is required prior to starting prednisolone in patients with active sepsis, bearing in mind that patients with cirrhosis may not mount a classic immune response to infection. 26 Biomarkers to predict risk of incident infection on steroids are an area of research interest; baseline NLR of >8 is also associated with increased infection at day 7 of corticosteroid treatment (OR 2.60, p=0.006), but requires further validation. 24

In clinical practice, the commencement of steroids is delayed until infection is excluded, including negative cultures of blood, urine and ascitic fluid. This period also allows for the assessment of the bilirubin trend which, along with risk stratification scoring, helps to inform the decision to start corticosteroids. 27

What are the considerations in managing alcohol withdrawal in patients with advanced liver disease?

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) should be assessed using the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for AlcoholScore, with a symptom-based regimen rather than fixed dosing in order to reduce drug accumulation. 28 Benzodiazepines reduce withdrawal symptoms and the risk of both seizures and delirium tremens and are considered the gold standard for treatment of AWS. Long-acting benzodiazepines such as chlordiazepoxide and diazepam should only be used with caution in patients with cirrhosis and impaired synthetic function due to their unpredictable half-life and significant accumulation in the presence of hepatic dysfunction, where the use of shorter-acting lorazepam or oxazepam may be preferable if available. In addition, benzodiazepines can both precipitate and worsen hepatic encephalopathy and so should be used with care.

Abstinence from alcohol remains the only independent predictor of long-term survival in patients presenting with severe AH 29 and early intervention from an alcohol liaison service during the hospital admission is of fundamental importance.

What is the role of nutrition in the management of AH?

Patients with both AH and cirrhosis are characterised by an almost universal state of malnutrition, sarcopenia and B vitamin deficiency, alongside increased resting energy expenditure and impaired metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids and proteins. 30 Early involvement of the dietetic team is vital to ensure patients with AH meet their nutritional requirements.

Increased caloric intake has been associated with a reduced incidence of infection, improved liver function and quicker resolution of hepatic encephalopathy in multiple randomised trials. 30 A recent large trial reported lower rates of infections and improved 1-month and 6-month mortality in patients with severe AH treated with corticosteroids who received a calorie intake of ≥21.5 kcal/kg/day compared with those who received<21.5 kcal/kg/day, regardless of Lille response or of the mode by which the calories were delivered. 31

EASL and European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines recommend an aim of 35–45 kcal/kg/day and a daily protein intake of 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day, with the oral route as first line and nasogastric feeding advised if oral intake is inadequate. 30 Intravenous thiamine replacement should be given to all patients with a history of alcohol use to reduce the risk of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Several clinical trials have failed to demonstrate evidence for the use of various specialised dietary formulas and ESPEN recommend using standard nutritional supplements or feed with a high energy density, with a late evening supplement to reduce overnight starvation duration. 30

Case part 3

A full septic screen including blood cultures did not reveal any evidence of sepsis. The patient is managed with nutritional supplements, lactulose 20 mL three times a day and prednisolone 40 mg once daily. At day 7, his blood results are bilirubin 355, INR 3.0, PT 27, Cr 90, albumin 29. Lille Score is 0.60 (>0.45) indicating a poor prognosis, so prednisolone is stopped. Overall 90-day mortality in patients with AH is approximately 30%, increasing to around 45% in patients with a Lille Score>0.45 after 7 days of corticosteroids. 19

Is liver transplantation an option in severe AH?

In Europe, ArLD is the leading indication for liver transplant (LT), but the timing and selection of patients for liver transplantation with ArLD is controversial. A period of abstinence is vital to understand the extent of hepatic recompensation that can occur without the need to undergo LT and to ensure the patient is engaged with the process. However, although pretransplant abstinence is one important predictor of post-LT sobriety, it is not the only factor, and there is data that the risk of relapse is no higher in carefully selected patients transplanted with severe alcoholic hepatitis (SAH) compared with those with alcohol-related cirrhosis under standard selection criteria. 32

Challenging the traditional exclusion of patients with SAH from consideration for LT, a multicentre cohort study in France offered LT to patients with SAH who met specific stringent selection criteria, including non-response to steroid therapy, a first presentation of liver decompensation and a robust social support network. 33 This study showed significantly improved survival in the group offered LT at 2 years (71% vs 23%), a benefit almost entirely gained in the first 6 months. Long-term follow-up data was recently presented, showing overall survival at 1, 5 and 10 years of 83%, 70% and 56%, respectively. Severe alcohol relapse was evident in 10%, similar to other cohorts transplanted for ArLD using standard selection criteria. 34

The largest study in the USA on LT in SAH is a retrospective review of United Network for Organ Sharing data. In 147 patients transplanted with SAH between 2006 and 2017, with no previous decompensation and abstinence of less than 6 months, 1-year and 3-year survival was 94% and 84%, while return to sustained drinking occurred in 10% at 1 year and 17% at 3 years. 35 Interestingly, in a smaller retrospective case-controlled study comparing patients transplanted with SAH with<6 months abstinence (n=46) with a group transplanted for standard ArLD criteria and>6 months abstinence (n=34), the two groups had comparable 1-year survival (97% vs 100%, p=1) and return to harmful drinking after median follow-up of 532 days (17% vs 12%, p=0.5). 32

The only prospective trial of early liver transplantation in SAH was a non-randomised, non-inferiority, controlled trial recently published by the group in France. Over 2 years of follow-up, patients with SAH offered early liver transplant (n=68) had a small but non-significant increased risk of alcohol relapse compared with those transplanted for alcohol-related cirrhosis after ≥6 months of abstinence (n=93, relative risk 1.45, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.60), but also a greater risk of high levels of alcohol intake (RR 4.10, 95% CI 1.56 to 10.75). The 2-year post-transplantation survival was similar between these groups (89.7% and 88.2% respectively, HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.26), whereas the overall 2-year survival of patients with SAH who were not transplanted (n=47) was significantly reduced compared with those who were (28.3% vs 70.6%, HR 0.27, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.47). 36

The landscape of public and medical opinion on offering transplantation for SAH is changing in light of this data. However, concerns remain that predictive models are suboptimal and over 50% of patients with an unfavourable prognosis based on the Lille Score will survive without LT. 37 As such, the UK pilot on LT in SAH failed to recruit any patients over a 3-year period and was closed. 38 The current UK position recommends that if liver insufficiency persists after 3 months of documented alcohol abstinence in individuals with an index presentation of severe AH, consideration should be given to referral for liver transplantation if their psychosocial risk profile is favourable. 37

Case part 4

The patient’s clinical condition deteriorates over the following week. He becomes febrile, an ascitic tap confirms spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (white cells 700 cells/mL, neutrophils>90%) and he develops an oliguric acute kidney injury with haemodynamic instability requiring regular fluid boluses. His liver function remains poor (UK Model for End Stage Liver Disease (UKELD) 68). You call the intensive care unit (ITU) to review the patient, but questions are raised about his suitability for level 3 care.

Should this patient be escalated to critical care?

This patient now requires organ support with inotropes and likely renal replacement therapy. Historically, patients with ArLD have experienced barriers to timely escalation to ITU due to a perceived poor prognosis. Data in the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death report in 2013 confirmed this practice, showing that 31% of patients deemed to require and be appropriate for escalation of care on independent review of the case notes did not receive such treatment. 39

In the same report, a review by the treating clinicians identified only 7% of cases who were appropriate for escalation but did not receive it. Subjective judgements detrimentally influenced these decisions and led the report to conclude that failure to escalate was due to clinicians having a prior view that it was not appropriate to escalate care in patients with ArLD.’ 39

Over the last 20 years, there has been a significant improvement in survival of patients admitted to ITU with organ failure complicating decompensated chronic liver disease, with mortality falling from 41.0% to 32.5% over this period, despite comparable scores for severity of illness at presentation. Although ArLD was associated with worse survival, improvements were also reported in this group over the same period (50.9% mortality to 41.9%, mean (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II Score 20 vs 19), such that the majority admitted to ITU will survive. 40

However, mortality rates for patients with ArLD and acute-on-chronic liver failure admitted to the ITU remain high, and escalation decisions require careful discussion and shared decision-making between the medical and critical care teams, alongside patients and their families as required. One of the first questions posed by the ITU team may be whether they are a transplant candidate. This is not a straightforward question to answer and may not be the most pertinent issue at this point in the patient’s care: in his case, the immediate answer would be ‘no’ in the UK, for reasons discussed above. But if he survives this admission, maintains abstinence but continues to have a qualifying UKELD Score he may be considered for a transplant assessment in 3 months.

In this instance, the patient’s age and the fact this is a first presentation with hepatic decompensation strongly support escalation at this stage, but the CLIF-ACLF prognostic scoring system can be helpful to add objective data to discussions between the managing team and ICU. While not including some increasingly recognised prognostic factors such as the presence of sarcopenia, the European Foundation for the Study of Chronic Liver Failure Acute-on-chronic Liver Failure (CLIF-C ACLF) Score has nevertheless been validated in a large dataset of patients with decompensated chronic liver disease and organ failure. 41 Days 3–7 on the ITU may be the optimal time to calculate this score, when an accurate assessment on the trajectory and likely outcome can be made. 42 Applying it in this way can support decision-making between the patient’s primary team and the ITU and provide timescales and goals with which to assess the benefits of level 3 care when there is disagreement or uncertainty.

However, even in the setting of treatment escalation it is important to remember that his overall prognosis is poor at this stage and, therefore, early involvement of the palliative care (PC) team should be considered. This can be done in parallel with full active medical care; it is important to bear in mind that PC is not synonymous with ‘end-of-life care’ and they are excellently equipped to optimise symptom control and begin to address wider holistic issues in the care of a patient at high risk of death. As such, early involvement of PC has been shown to improve symptom control and quality of life. 43

Case part 5

After 2 weeks in the ITU and a prolonged inpatient stay, the patient makes sufficient recovery to be discharged home. He continues to have moderate ascites managed with spironolactone and significant liver synthetic dysfunction (UKELD 60). He begins to attend his local alcohol support group and his partner has removed all alcohol from the house to support his abstinence.

When should you refer for transplant assessment?

Although he has made significant progress, this patient remains very unwell and at high risk of further deterioration. His ‘window of opportunity’ for transplant assessment is small. There is no fixed rule on this, but recent guidelines suggest that referral should be considered after 3 months of abstinence, or even sooner if the patient is actively engaged in alcohol cessation support, if there are issues that may complicate the workup assessment, or if the risk of death within 3 months is high. 44 In parallel to referral, every effort should be made to optimise his physical fitness, including dietician input and a graded exercise plan.

The patient maintains abstinence, is referred and successfully receives a life-saving liver transplant. A multidisciplinary team approach is required for patients admitted with decompensated ArLD, in which a dedicated alcohol care team is vital, but preventative measures on a population (eg, minimum unit pricing) and individual (eg, brief interventions and fibrosis stratification) level early in the disease course will have the greatest impact.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

- Griswold MG ,

- Fullman N ,

- Williams R ,

- Aspinall R ,

- Bellis M , et al

- Kettaneh A ,

- Tengher-Barna I , et al

- Pavlov CS ,

- Casazza G ,

- Nikolova D , et al

- Detlefsen S ,

- Sevelsted Møller L , et al

- Lackner C ,

- Bataller R ,

- Burt A , et al

- Madsen BS ,

- Hansen JF , et al

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- Anderson P ,

- Chisholm D ,

- Gillespie D ,

- Ally A , et al

- de Franchis R , Baveno VI Faculty

- Forrest E ,

- Chalasani NP , et al

- Altamirano J ,

- Katoonizadeh A , et al

- Horvath B ,

- Allende D ,

- Xie H , et al

- Forrest EH ,

- Atkinson SR ,

- Richardson P , et al

- Singal AK ,

- Ahn J , et al

- Thursz MR ,

- Richardson P ,

- Allison M , et al

- Chandar AK , et al

- Garcia-Saenz-de-Sicilia M ,

- Altamirano J , et al

- Sinha R , et al

- Baeza N , et al

- Knapp S , et al

- Cabezas J ,

- Mirijello A ,

- D’Angelo C ,

- Ferrulli A , et al

- Labreuche J ,

- Artru F , et al

- Bischoff SC ,

- Dasarathy S , et al

- Deltenre P ,

- Senterre C , et al

- McCaul ME , et al

- Mathurin P ,

- Samuel D , et al

- Dharancy S ,

- Dumortier J , et al

- Platt L , et al

- Moreno C , et al

- Aldersley H ,

- Leithead JA , et al

- Juniper M ,

- Kelly K , et al

- McPhail MJW ,

- Parrott F ,

- Wendon JA , et al

- Pavesi M , et al

- Fernandez J ,

- Garcia E , et al

- Woodland H ,

- Forbes K , et al

- Millson C ,

- Considine A ,

- Cramp ME , et al

- Newsome PN ,

- Davison SM , et al

Twitter @jamesbmaurice

Contributors JBM conceptualised the original article and the case. JBM, ST and AZ drafted the initial version of the manuscript. JBM and ST contributed further editing of various sections. JR provided senior critical review and edited the manuscript. All authors agreed upon the final version.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Linked Articles

- Highlights from this issue UpFront R Mark Beattie Frontline Gastroenterology 2023; 14 357-358 Published Online First: 07 Aug 2023. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2023-102519

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Cirrhosis Case Study (45 min)

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Study tools.

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

Mr. Garcia is a 43-year-old male who presented to the ED complaining of nausea and vomiting x 3 days. The nurse notes a large, distended abdomen and yellowing of the patient’s skin and eyes. The patient reports a history of alcoholic cirrhosis.

What initial nursing assessments should be performed?

- Full abdominal assessment, including assessing for ascites

- Heart and lung sounds

- Skin assessment – color, turgor, etc.

- Full set of vital signs

- Neurological assessment

What diagnostic testing do you anticipate for Mr. Garcia?

- LFT’s, CBC, BMP

Mr. Garcia’s vitals are stable, BP 100/58, bowel sounds are active but distant, and the nurse notes a positive fluid wave test on his abdomen. The patient denies itching but is constantly scratching at his chest. He is oriented to person only and his brother at the bedside reports he hasn’t been himself today. He keeps trying to get out of bed

Which finding is most concerning and needs to be reported to the provider? Why?

- Confusion, disorientation – this could indicate hepatic encephalopathy, which could lead to seizures and death if left untreated

What further diagnostic and lab tests should be ordered to determine Mr. Garcia’s priority problems?

- Abdominal X-ray and/or Abdominal ultrasound to visualize liver and whether the distended abdomen is related to ascites or other sources

- Ammonia level to determine if hepatic encephalopathy is the source of Mr. Garcia’s altered mental status.

The provider places orders for the following:

Keep SpO 2 > 92%

Keep HOB > 30 degrees

Insert 2 large bore PIV’s

500 mL NS IV bolus STAT

100 mL/hr NS IV continuous infusion

Hydrocodone/Acetaminophen 5-500 mg 1-2 tabs q4h PRN moderate to severe pain

Diphenhydramine 25 mg PO q8h PRN itching

Ondansetron 4 mg IV q6h PRN nausea

Lactulose 20 mg PO q6h

Mr. Garcia’s LFT’s and Ammonia level are elevated. He is extremely confused and agitated and appears somewhat short of breath. The patient’s current vital signs are as follows:

HR 82 RR 22

BP 94/56 SpO 2 93%

Temp 98.9°F

Which order should be implemented first? Why?

- Insert two large-bore IV’s. The patient requires IV fluids and has other IV meds ordered and will likely need labs drawn. This needs to be a priority.

- You could also say elevate the HOB to 30 degrees or higher, if there was indication that he was lying flat

- His SpO2 is >92%, so no intervention is required there.

- Lactulose should be the next priority intervention – to get the ammonia levels down – but it may take a bit for pharmacy to profile it, send it to the unit, etc.

Which order should be questioned? Why?

- Hydrocodone/Acetaminophen – Acetaminophen can be toxic for patients with liver disease. The way this order is written, this patient could receive anywhere from 3 g – 6 g of Acetaminophen in a 24-hour period. The max for a healthy person is 4 g, but for liver patients, it is 2 g max.

- Either the dose and frequency should be lowered significantly, or the medication should be changed altogether

The order is changed to Fentanyl 25 mcg IV q4h PRN moderate to severe pain. The provider notes somewhat shallow breathing and severe ascites and requests for you to set up for paracentesis. At this time, you express your concern that the patient is extremely confused and agitated and trying to get out of bed. You do not feel that he will be still enough for the procedure. The provider agrees and plans to postpone the paracentesis for now, but orders for you to report any signs of respiratory depression or hypoxia.

Why is Mr. Garcia so confused and agitated?

- His ammonia levels are elevated due to his liver failure – this causes hepatic encephalopathy – damage to the brain cells

- This causes altered mental status, agitation, confusion, and can eventually lead to seizures and death if left untreated

What is the rationale for performing a paracentesis for Mr. Garcia?

- The excess fluid in Mr. Garcia’s belly is compressing his thoracic cavity, causing him to feel short of breath and to only take shallow breaths. Draining this fluid will not only relieve some discomfort, but it can also help improve Mr. Garcia’s breathing

After 6 doses of lactulose, Mr. Garcia is much more calm and cooperative. He is oriented times 2-3 most times. The provider performs the paracentesis and is able to remove 1.5 L of fluid. The patient’s shortness of breath is relieved, and his breathing is less shallow. Ultrasound of the liver showed severe scarring on the liver. Mr. Garcia’s condition continues to improve, and the plan is to discharge him home tomorrow.

What discharge teaching should be included for Mr. Garcia, including nutrition?

- Mr. Garcia should not be eating a high protein diet as this can contribute to the increased ammonia levels and development of hepatic encephalopathy.

- Mr. Garcia should avoid drinking alcohol at all times

- Medication instructions for any new or changed medications

- Especially the importance of taking Lactulose regularly as ordered

- Signs to report to the provider of exacerbation or encephalopathy

View the FULL Outline

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

Nursing Case Studies

This nursing case study course is designed to help nursing students build critical thinking. Each case study was written by experienced nurses with first hand knowledge of the “real-world” disease process. To help you increase your nursing clinical judgement (critical thinking), each unfolding nursing case study includes answers laid out by Blooms Taxonomy to help you see that you are progressing to clinical analysis.We encourage you to read the case study and really through the “critical thinking checks” as this is where the real learning occurs. If you get tripped up by a specific question, no worries, just dig into an associated lesson on the topic and reinforce your understanding. In the end, that is what nursing case studies are all about – growing in your clinical judgement.

Nursing Case Studies Introduction

Cardiac nursing case studies.

- 6 Questions

- 7 Questions

- 5 Questions

- 4 Questions

GI/GU Nursing Case Studies

- 2 Questions

- 8 Questions

Obstetrics Nursing Case Studies

Respiratory nursing case studies.

- 10 Questions

Pediatrics Nursing Case Studies

- 3 Questions

- 12 Questions

Neuro Nursing Case Studies

Mental health nursing case studies.

- 9 Questions

Metabolic/Endocrine Nursing Case Studies

Other nursing case studies.

Liver Cirrhosis Case Study

56 year old Caucasian male with end-stage liver cirrhosis in hospice care, came in for stem cell therapy to help prolong his life. Patient had a history of chronic Hepatitis C, hypertension and diabetes, and did not qualify for liver transplant. Patient had declined steadily over the past year, and over the last month, he had an unintentional weight loss of 30 lbs. He had been struggling with fatigue, weakness, and occasional fever and chills, and also reported of shortness of breath, wheezing, and edema of lower extremities. At the time of treatment, patient presented with an distended abdomen (ascites), with very little energy to even speak.

Pin It on Pinterest

Citation, DOI, disclosures and case data

At the time the case was submitted for publication Abhijit Chikhlikar had no recorded disclosures.

Presentation

Swelling and fullness of the abdomen.

Patient Data

Ultrasound study shows a full spectrum of cirrhosis: small liver, nodular margins of the liver, dilated portal vein, ascites, splenomegaly and hepatofugal flow on portal vein. Incidental findings of a left ovarian cyst.

Case Discussion

Cirrhosis is the common endpoint of a wide variety of chronic disease processes which cause hepatocellular necrosis.

11 public playlists include this case

- LIVER US by Federico Giovanni Galbiati

- ecoografie by Popovici Alexandra

- R1 US by Bennett Battle

- abdomen by MD IRFAN ALAM

- Liver by Oleksii Burian

- UCD Medical Students 2018 by Danielle Byrne

- bizzarre by Federico Giovanni Galbiati

- QUIZ studenci by Adam

- liver by nour

- GK - Abdo - Liver by GLK

- GIT-Liver 2 by Mohamed shweel

Related Radiopaedia articles

- Hepatofugal

- Portal vein

- Splenomegaly

Promoted articles (advertising)

How to use cases.

You can use Radiopaedia cases in a variety of ways to help you learn and teach.

- Add cases to playlists

- Share cases with the diagnosis hidden

- Use images in presentations

- Use them in multiple choice question

Creating your own cases is easy.

- Case creation learning pathway

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

By Section:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Feature Sponsor

- Expert advisers

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

A, Cumulative recurrence ( P = .001; log-rank). B, Disease-specific survival ( P = .04; log-rank).

A, Number of recurrences in entire matched cohort (median [interquartile range]: solitary recurrence, 18.3 [14.7-64.4]; 2-3 recurrences, 9.6 [4.3-47.3]; and ≥4 recurrences, 5.8 [3.3-7.0]). B, Recurrences by site in entire matched cohort (median [interquartile range]: near, 12.8 [6.1-26.5]; distant, 19.8 [9.1-41.0]; and extrahepatic, 7.6 [4.7-12.6]). C, Number of recurrences in patients with normal liver (median [interquartile range]: solitary recurrence, 29.0 [15.4-56.0]; 2-3 recurrences, 4.7 [4.6-40.8]; and ≥4 recurrences, 5.8 [4.4-6.7]). D, Recurrences by site in patients with normal liver (median [interquartile range]: near, 8.9 [6.1-34.7]; distant, 22.8 [4.4-41.6]; and extrahepatic, 7.0 [4.4-14.0]). E, Number of recurrences in patients with liver cirrhosis (median [interquartile range]: solitary recurrence, 18.3 [9.4-36.4]; 2-3 recurrences, 9.7 [7.2-22.5]; and ≥4 recurrences, 8.1 [3.4-12.8]). F, Recurrences by site in patients with liver cirrhosis (median [interquartile range]: near, 13.5 [9.8-20.4]; distant, 19.8 [9.6-39.6]; and extrahepatic, 8.2 [6.5-8.7]).

A, Number of recurrences in entire matched cohort. B, Number of recurrences in patients with a normal liver. C, Number of recurrences in patients with liver cirrhosis. D, Recurrences by site in entire matched cohort. E, Recurrences by site in patients with a normal liver. F, Recurrences by site in patients with liver cirrhosis.

A, Estimated annual recurrence rate over time after hepatectomy. B, Cumulative hazard of recurrence.

eTable 1. Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

eTable 2. Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics in Matched Cohort

- Hepatectomy for Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma JAMA Surgery Invited Commentary March 15, 2017 Roberto Hernandez-Alejandro, MD; Mark A. Levstik, MD; David C. Linehan, MD

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Sasaki K , Shindoh J , Margonis GA, et al. Effect of Background Liver Cirrhosis on Outcomes of Hepatectomy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):e165059. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5059

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Effect of Background Liver Cirrhosis on Outcomes of Hepatectomy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- 1 Division of Surgical Oncology, Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland

- 2 Hepatobiliary Surgery Division, Department of Digestive Surgery, Toranomon Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

- 3 Okinaka Memorial Institute for Medical Research, Toranomon Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

- Invited Commentary Hepatectomy for Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma Roberto Hernandez-Alejandro, MD; Mark A. Levstik, MD; David C. Linehan, MD JAMA Surgery

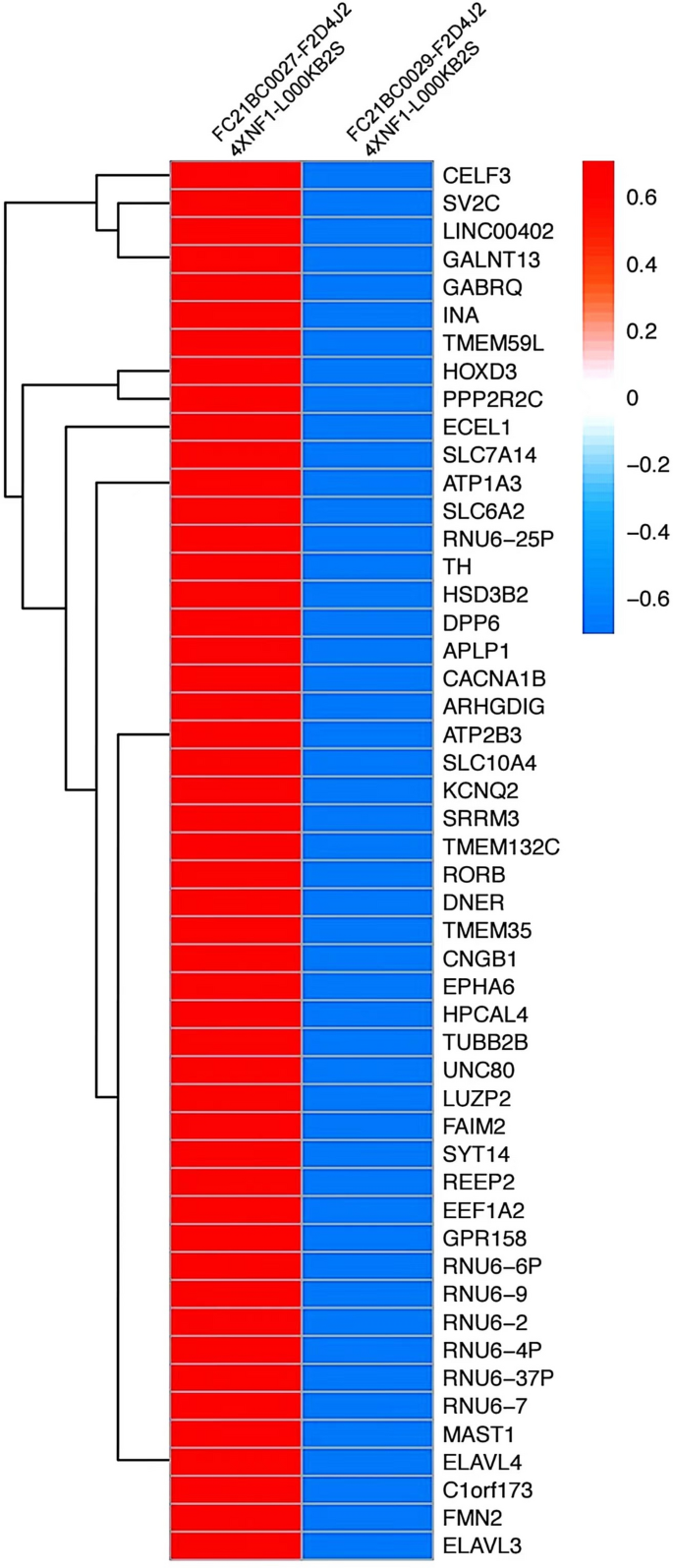

Question What is the pattern and recurrence rate of de novo hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with liver cirrhosis and normal liver after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma?

Findings The median annual incidence of postoperative recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma within 5 years after surgery was lower in the group with normal liver (5.9%) compared with the group with liver cirrhosis (12.7%). Multiple recurrences near the resection margin or at extrahepatic sites were more frequent in the group with normal liver (50.0% vs 15.4%), whereas solitary recurrence at a distant site was more common in the group with liver cirrhosis (53.8% vs 5.6%).

Meaning Comparison of the patterns and annual incidence of recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma demonstrated that the poorer prognosis in the group with liver cirrhosis was likely owing to a higher hepatocarcinogenic potential among patients with cirrhosis.

Importance Background hepatocarcinogenesis is considered a major cause of postoperative recurrence of de novo hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with liver cirrhosis (LC). The degree of underlying liver injury has reportedly correlated with surgical outcomes of HCC. However, the pattern and annual rate of recurrence of postoperative de novo HCC are still unclear.

Objective To clarify the pattern and rate of recurrence of de novo HCC in patients with LC.

Design, Setting, and Participants Data from 799 patients who underwent curative hepatectomy for HCC at Toranomon Hospital and The Johns Hopkins Hospital between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2014, were retrospectively collected and analyzed. Of the patients who underwent curative hepatectomy for HCC, 424 met inclusion criteria: 73 with normal liver (NL) and 351 with LC. Sixty-four patients who had histologically proven NL parenchyma were matched with an equal number of patients who had established LC, and postoperative outcomes were compared.

Interventions Hepatectomy in patients with HCC.

Main Outcomes and Measures Patterns of recurrence of HCC and chronological changes in recurrence rates.

Results Among 128 matched patients in the study (mean [SD] age, 64.0 [12.7] years; 93 men and 35 women) 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative recurrence was 17.2%, 23.0%, and 37.5%, respectively, in the NL group vs 25.0%, 55.5%, and 72.1%, respectively, in the LC group ( P = .001). The 3- and 5-year disease-specific survival was 85.7% and 75.4%, respectively, in the NL group vs 74.9% and 59.1%, respectively, in the LC group ( P = .04). The median annual incidence of postoperative recurrence of HCC within 5 years after surgery was lower in the NL group (5.9%) compared with the LC group (12.7%) ( P = .003). Assessment of recurrence patterns revealed that multiple recurrences near the resection margin or at extrahepatic sites were more frequent in the NL group (9 [50.0%] vs 6 [15.4%]; P = .01), whereas solitary recurrence at a distant site was more common in the LC group (21 [53.8%] vs 1 [5.6%]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance Comparison of the patterns and annual incidence of recurrence of HCC demonstrated that the poorer prognosis in the LC group was likely owing to a higher hepatocarcinogenic potential among patients with cirrhosis. Annual recurrence rates in the 2 groups indicate that de novo recurrence may continuously occur from the early postoperative period until the late period after resection of HCC.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer in men, and seventh among women, with more than half a million new cases diagnosed annually worldwide. In most cases, the etiologic factors of HCC are attributable to underlying liver injury due to chronic hepatitis or liver cirrhosis (LC). 1 , 2 Although hepatic resection is one of the most effective treatment options for patients with HCC and preserved hepatic functional reserve, the cumulative risk of recurrence during the first 5 years after surgery ranges from 70% to 100%. 3 - 5 As such, local tumor control remains a major issue in the clinical management of HCC. The high risk of recurrence after curative-intent hepatectomy is attributable to 2 unique patterns: recurrence derived from residual micrometastases and de novo recurrence owing to carcinogenic potential in the underlying liver. 6 , 7 Oncologic outcomes after resection of HCC have reportedly correlated with the degree of underlying liver injury, especially among patients with LC. 1 , 2 Given that the annual incidence of HCC arising from established LC has been reported to range between 2.5% and 6.6%, 8 - 10 it is estimated that the cumulative incidence of recurrence owing to de novo carcinogenesis would result in significant differences in long-term outcomes among patients with LC vs patients who have an undamaged liver.

Previous studies examining the influence of de novo recurrence of HCC attempted to distinguish the type of recurrence by using a time frame (early recurrence, occurring within 2 years after surgery, and late recurrence, occurring more than 2 years after surgery). 6 , 7 , 11 , 12 However, it is difficult to clearly distinguish the causes of recurrence of HCC, and the actual prognostic effect of de novo recurrence remains unclear. To address this issue, our study sought to determine the prognostic difference associated with the carcinogenic potential between patients with LC and those with a normal liver (NL) in a case-matched population adjusted for other oncologic factors.

A total of 799 adult patients without a history of previous HCC treatment who underwent curative-intent surgery for HCC between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2014, at Toranomon Hospital in Tokyo, Japan, and at The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, were identified from a multi-institutional database. Only patients with HCC who had either histologically proven LC or NL were included in this study, which was approved by the Toranomon Hospital Human Ethics Review Committee and The Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board. No additional informed patient consent specific to this study was required given its retrospective nature.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection was defined by seropositivity for HBV surface antigen and/or HBV DNA; hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was defined as patients who were seropositive for HCV antibody and/or HCV-RNA. Alcohol abuse was defined as chronic liver injury resulting from alcohol consumption of 60 g/d or more without another clear etiologic factor and was confirmed by pathologic examination of the specimen. 13 The serum HBV-DNA level was investigated in patients with HCC without definitive etiologic factors to detect occult HBV infection. 14 Conditions such as autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, Wilson disease, and hemochromatosis were included in the category of other etiologies. Types 1 and 2 diabetes were diagnosed based on the 2003 criteria of the American Diabetes Association. 15

Histopathologic variables were defined according to the pathologic classification system of the World Health Organization. 16 Specimens were fixed in 10% formalin and stained with hematoxylin-eosin, Masson trichrome, silver impregnation, and periodic acid–Schiff after diastase digestion. Only the area of noncancerous liver parenchyma that was distant from the tumor was evaluated to avoid influence from the tumor. Fibrosis and status of inflammation were evaluated using the METAVIR score. 17 Patients with no background liver damage, as evidenced by a liver that had had no fibrosis, moderate to severe inflammation, or severe steatosis (>30% of the total liver parenchyma) were assigned to the NL group. Patients with established cirrhosis (stage F4) were assigned to the LC group.

To control for the possibility of recurrence of HCC from residual micrometastases between the 2 groups, 1-to-1 individual paired case matching was performed for clinical factors other than underlying liver injury using R statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) with the optmatch package, which uses the optimal matching method with no caliper ( https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/optmatch/optmatch.pdf ). Distance was calculated using Mahalanobis distance. These factors used for matching included sex, age, type of surgery, surgical margin status, tumor size, tumor differentiation, microvascular invasion, and preoperative serum α-fetoprotein level. After matching, the cumulative rate of recurrence, overall rate of survival, patterns of recurrence, and chronological changes in rates of recurrence were analyzed and compared.

Data were analyzed with SPSS software, version 19 (IBM SPSS), and EZR. 18 Continuous variables were expressed as median and range or interquartile range. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables between the 2 groups. The χ 2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables between the 2 groups as appropriate. Cumulative recurrence and disease-specific survival were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences between curves were assessed by the log-rank test. P < .05 (2-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Among 799 adult patients who underwent primary curative-intent hepatectomy for HCC during the study period, 424 patients (285 men and 139 women) met the inclusion criteria. Of these patients, 73 had histologically proven NL parenchyma and 351 had LC. The baseline characteristics of the NL and LC groups are summarized in eTable 1 in the Supplement . Chronic hepatitis infection, including HBV and HCV, was the major cause of LC (HBV, 114 [32.5%] and HCV, 206 [58.7%]). The prevalence of diabetes in the NL group was higher than in the LC group, although the difference was marginal (NL, 17 [23.3%] and LC, 59 [16.8%]; P = .18). Data from baseline liver function tests, including aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferanse levels, total bilirubin level, platelet count, and Child-Pugh grade, were different between the NL and LC groups. The preoperative median serum α-fetoprotein level was also different between the 2 groups (NL, 5.0 ng/mL; LC, 20.7 ng/mL; P < .001) (to convert to micrograms per liter, multiply by 1.0).

With regard to treatment-associated factors, 36 patients (49.2%) in the NL group underwent anatomical liver resection, whereas 70 patients (19.9%) in the LC group underwent an anatomical resection ( P < .001). The proportion of resections with an R1 surgical margin was comparable between the groups (NL, 4 [5.5%] and LC, 32 [9.1%]; P = .49). With respect to tumor-associated characteristics, the proportion of multiple tumors was similar between the 2 groups (NL, 9 [15.5%] and LC, 41 [13.4%]; P = .84). The median maximum tumor diameter in the NL and LC groups was 40.5 mm (range, 20.0-250.0) and 20.0 mm (range, 2.0-150.0 mm), respectively ( P < .001). Tumors with poor histologic differentiation were more commonly found in the NL group (20 [27.4%]) than in the LC group (57 [16.2%]) ( P = .03). The presence of microvascular invasion tended to be more common in the NL group (20 [27.4%]) than in the LC group (69 [19.7%]) ( P = .16). Mild steatosis in the resected liver was noted in 30 patients (41.1%) in the NL group.

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the case-matched cohort are summarized in eTable 2 in the Supplement . Sixty-four patients who had histologically proven NL parenchyma were matched with an equal number of patients who had established LC. Matching variables included age, sex, operative factors, and tumor-associated factors. The proportion of patients with diabetes was similar between the 2 groups (NL, 18 [28.1%] and LC, 16 [25.0%]; P = .84). Despite matching, background liver function, including alanine aminotransferase level and platelet count, remained different between the 2 groups.

The median follow-up time of the matched cohort was 40.2 months (interquartile range, 21.5-62.6 months). The median follow-up period of the NL group was 39.4 months (interquartile range, 19.8-59. months), which was comparable with follow-up time for the LC group (median, 40.8 months; interquartile range, 24.2-67.5 months) ( P = .64). Recurrence was observed in 18 patients (28.1%) in the NL group and 39 patients (60.9%) in the LC group ( P < .001). Overall, 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative recurrence was 17.2%, 23.0%, and 37.5%, respectively, in the NL group vs 25.0%, 55.5%, and 72.1%, respectively, in the LC group ( P = .001; log-rank test) ( Figure 1 A). The 3- and 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 85.7% and 75.4%, respectively, in the NL group vs 74.9% and 59.1%, respectively, in the LC group ( P = .04; log-rank test) ( Figure 1 B). Of 64 patients in the NL group, no patients died of causes associated with liver disease other than recurrence of HCC; of 64 patients in the LC group, 3 patients died of liver failure and 1 patient died of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

When comparing patterns of recurrence in the matched cohort, both the number of recurring lesions (NL, 18 [28.1%] and LC, 39 [60.9%]; P < .001) and site of recurrence (NL: near resection site, 7 [38.9%], distant from resection site, 4 [22.2%], and extrahepatic, 7 [38.9%]; LC: near resection site, 13 [33.3%], distant from resection site, 23 [59.0%], and extrahepatic, 3 [7.7%]; P = .005) were significantly different between the 2 groups ( Table ). In the NL group, most patients (12 of 18 [66.7%]) experienced multiple recurrences, whereas most patients in the LC group (31 of 39 [79.5%]) experienced a solitary recurrence ( P = .001). Moreover, recurrence with 4 or more lesions was seen more frequently in the NL group than in the LC group (7 of 18 [38.9%] vs 4 of 39 [10.3%]; P = .03). In total, either multiple recurrences near the resection site and/or extrahepatic recurrence was the most frequent pattern of recurrence in the NL group than in the LC group (9 of 18 [50.0%] vs 6 of 39 [15.4%]; P = .01), whereas intrahepatic solitary recurrence distant from the resection site was the most frequent recurrence pattern in the LC group (NL, 1 of 18 [5.6%] and LC, 21 of 39 [53.8%]; P < .001)

The correlation between time to recurrence and patterns of recurrence is shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3 . In the matched cohort, the median time to recurrence among patients with a solitary recurrence was longer than that among patients who experienced multiple recurrences (18.3 vs 6.1 months; P = .001). The difference in median time to recurrence for patients with single vs multiple recurrences persisted in both the NL and LC groups (NL: 29.0 vs 5.7 months; P = .007; LC: 18.3 vs 9.7 months; P = .04). Recurrence at a site distant from the resection tended to develop later after resection compared with other sites of recurrence (median, 19.8 vs 10.0 months; P = .06), a finding that was similar in both NL and LC groups (NL: median, 22.8 vs 7.8 months; P = .92; and LC: median, 19.8 vs 11.2 months; P = .07). Recurrences distant from the resection site were consistently seen from the early period to the late period after resection. Differences in overall patterns of recurrence between the NL and LC groups persisted over time ( Figure 3 B).

The estimated annual rates of postoperative recurrence for both groups are shown in Figure 4 A. The median estimated annual rates of postoperative recurrence during the 5 years following resection were 5.9% in the NL group and 12.7% in the LC group ( P = .003). Although the risk of recurrence was bimodal for both the NL and LC groups, patients in the NL group tended to develop recurrences earlier than did patients in the LC group.

Our study aimed to characterize postoperative de novo recurrence of HCC among patients with LC using a case-matched analysis comparing patients with LC and those with NL who had oncologically equivalent tumors. Despite genetic analysis being the criterion standard to establish that recurrent disease is de novo HCC, few studies have used this approach. 19 - 21 Rather, most previous studies that have investigated postoperative recurrence of de novo HCC were based on the timing of recurrence. Previous investigators assumed that de novo recurrences developed exclusively in the late postoperative period and therefore classified such recurrences as de novo disease. 6 , 7 , 11 , 12 The carcinogenic potential in the liver remnant is, however, theoretically stable; as such, subsequent de novo recurrence can develop at any time, even in the early period after surgery. To mitigate the limitations associated with the assumption that postoperative recurrences of de novo HCC were based on the timing of recurrence, we conducted a case-matched analysis to define differences in postoperative recurrence of HCC among patients with NL and LC. Histologically proven NL parenchyma has a very low carcinogenic potential. Therefore, we hypothesize that the prognostic difference observed between the patients with a NL and those with LC could be attributed to the difference in carcinogenic potential between the 2 groups. We found that there was a marked difference in the patterns of recurrence between patients with NL and those with LC who underwent resection of an index HCC. Specifically, the main difference in the pattern of recurrence between the 2 groups was observed in the incidence of recurrent disease located distant from the resected portion of the liver. The recurrence rate among patients in the LC group remained consistently 6% to 15% higher than that in the NL group 1 to 4 years after resection.

In examining specific patterns of recurrence, the NL group more often had multiple recurrences near the resection site or at an extrahepatic site, mostly during the early period after resection. In contrast, the LC group tended to develop solitary recurrences located at a distance from the resected part of the liver; this pattern of recurrence among patients with LC was consistent from the early period after surgery to the late follow-up period. The differences in patterns of recurrence were also correlated with differences in postoperative recurrence. The reason for the different patterns of recurrence between the NL and LC groups was undoubtedly multifactorial. Theoretically, recurrence derived from residual micrometastases can develop in the relatively early period after surgery at or near the resection site (ie, intrahepatic micrometastases within a tumor-bearing portal territory) or at an extrahepatic site (ie, distant metastases through systemic circulation). 22 Moreover, time to recurrence was shorter for patients with multiple recurrences than for those with a single recurrence. Explanations of early multiple recurrences might be dissemination of the resected tumor or growth of multiple tumors at the initial surgery site, with microscopic nodules in the remaining liver being missed by imaging only to become apparent later. Conversely, an intrahepatic recurrence distant from the primary resection site may be considered a typical pattern of de novo recurrence. 23 , 24 In other words, the observed difference in patterns of recurrence are consistent with the hypothesis that postoperative recurrences in the NL group can be attributed largely to recurrence from residual cancer, whereas those of patients with LC are owing to both recurrence derived from micrometastases and de novo recurrence associated with the higher carcinogenic potential in the underlying liver.

Chronological changes in the annual incidence of recurrence demonstrated that recurrence in the LC group was about 6% to 15% higher per year than the risk of recurrence in the NL group ( Figure 4 A). Furthermore, after the first postoperative year, the cumulative hazards of recurrence continuously diverged over time ( Figure 4 B). These findings indicate that de novo recurrence may occur continuously from the early postoperative period until the late period. The annual incidence of primary HCC in patients with LC without a history of HCC is estimated to be 2.5% to 6.6%. 8 - 10 However, in patients with a history of HCC, a several-fold increase in the risk of developing a second primary HCC has been reported. 11 , 12 The difference in the annual rates of recurrence observed between the LC and NL groups is compatible with reported results in other patient populations. 7 , 10 , 11 , 25 , 26 The high annual incidence of de novo recurrence after resection persisted from the early to the late postoperative period.

The timing and bimodal nature of the rate of recurrence was roughly comparable between the NL and LC groups, although recurrence tended to be slightly earlier in the NL group ( Figure 4 ). The first peak of recurrence consisted of both recurrences owing to dissemination of resected tumor and small lesions that were not detected by imaging at the time of surgery. Considering that solitary recurrence at a distal site is much higher in the LC group, the first peak among the LC group would contain more undetected lesion at the time of surgery ( Figure 3 ). Imamura et al 11 reported a similar recurrence pattern in patients with LC and attributed the late peak to de novo recurrence of HCC owing to background LC. In our study, however, there was a late recurrence peak also seen in the NL group. Other investigators have similarly reported late recurrences arising among patients with NL. 25 - 28 These late recurrences might be attributed to unknown background liver carcinogenesis present in patients with NL and an index HCC. Given the low chance of carcinogenesis in histologically proven NL, late recurrences in a patient with NL may derive from slowly growing recurrences of the resected index tumor. To this end, a previous study that included 15 944 patients with nonviral hepatitis without a history of significant alcohol intake or fatty liver revealed that only 2 patients (0.01%) developed HCC during the 1-year follow-up period. 29 Although presence of fatty liver and diabetes are known risk factors of hepatocarcinogenesis, Kawamura et al 29 reported that the annual incidence of HCC among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease was only 0.04%, while the reported hazard ratio of patients with diabetes compared with patients who do not have diabetes is about 2.2 to 3.5. 30 , 31 Even though patients with a history of HCC have a several-fold increase in hepatocarcinogenesis compared with patients without a previous HCC, the rate of carcinogenesis is still negligibly low compared with the risk among patients who have established LC. In the future, genetic investigations comparing primary and recurrent lesions in patients with NL are required to provide more compelling evidence regarding the origin of late recurrences.

Our study had some limitations, including the retrospective study design. Individual paired matching was performed using a large population of patients with LC to generate the matched pairs. Despite the attempt at matching, it is possible that some residual differences in the 2 groups persisted. 32 Although the biology of HCC may differ according to background etiologic factors, most traditional factors associated with aggressiveness of the disease were comparable between the 2 groups. However, residual differences of aggressiveness of the disease that arise in healthy vs cirrhotic livers may not have been fully accounted for. Furthermore, the different etiologic factors associated with the underlying LC were not taken into account. However, the incidence of HCC is fairly similar among patients who develop LC owing to different causes. 33 Although some differences may exist in the activity and modes of cancer promotion among patients with HBV infection, HCV infection, and alcohol abuse, the etiologic factors of background HCC were not associated with recurrence. Given the retrospective nature of the study, we also could not assess the presence or absence of a lead time bias or difference in screening protocol between the NL and LC groups.

Our study demonstrated different oncologic outcomes among patients with HCC and an underlying NL compared with patients who had LC. Specifically, patients with LC had a 6% to 15% higher annual risk of de novo recurrence compared with patients who had HCC resected from NL. Given the constant higher risk of de novo recurrence starting in the early postoperative period for patients with LC, preemptive treatment of viral hepatitis and close follow-up are important to decrease the risk of recurrence and detect early recurrent disease.

Accepted for Publication: October 28, 2016.

Corresponding Author: Timothy M. Pawlik, MD, MPH, PhD, Division of Surgical Oncology, Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, 600 N Wolfe St, Blalock 688, Baltimore, MD 21287 ( [email protected] ).

Published Online: January 4, 2017. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5059

Author Contributions: Dr Pawlik had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Sasaki, Shindoh, Margonis, Nishioka, Andreatos, Sekine, Pawlik.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Sasaki, Shindoh, Margonis, Nishioka, Andreatos, Sekine, Pawlik.

Statistical analysis: Sasaki, Shindoh, Nishioka, Andreatos, Sekine, Pawlik.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Hashimoto, Pawlik.

Study supervision: Shindoh, Margonis, Pawlik.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Nutrition counsellor

- Food Allergy

- gastroenterology

- Heptologist In Delhi

- Liver transplant

- Alcoholic Liver Cirrhosis

Alcoholic liver cirrhosis is a late stage of fibrosis of the liver caused by many forms of liver diseases and conditions, such as chronic alcoholism. A person diagnosed with an alcoholic liver case may start from having fatty liver disease, then alcoholic hepatitis, and ultimately develop alcoholic cirrhosis. Hence, alcoholic liver cirrhosis stages in three levels. The diagnosed liver cirrhosis can be of two types :

- Compensated cirrhosis – when symptoms are not noticeable

- Uncompensated cirrhosis- when the symptoms can be noticed

The most common alcoholic liver causes are:

- Chronic alcohol consumption

- Chronic hepatitis

- Fatty liver disease

- Iron buildup in the body or hemochromatosis

- Copper accumulated in the liver (Wilson’s disease)

- Cystic fibrosis

- Biliary Atresia

- Inherited sugar metabolism or digestive disorders

- Infection like syphilis

Many other factors like the destruction of bile ducts(Primary Biliary Cirrhosis) or leaky gut also called, increased intestinal permeability are cofactors for the development of alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

Now, let us have a look at alcoholic liver cirrhosis symptoms:

- Food pipe problems

- Portal hypertension

- Swelling in legs (oedema) and abdomen (ascites)

- Bleeding in mouth

- Confusion, poor memory, loss of appetite

- Patchy red skin on palms (erythema)

Food pipe problem is also known as esophageal varices. Kidney failure and hypersplenism are other complications that happen due to this medical condition. If the symptoms are not taken seriously, then this deficient liver may arise a life-threatening situation. Hence, a person needs to keep a track of these indicators as if these signs are caught early and treated, it may slow down the progression of the disease.

How to treat alcoholic liver cirrhosis:

The first and foremost step in treatments is to help the patient to cease alcohol consumption. Medications like corticosteroids, calcium channel blockers, insulin can also be prescribed by the doctor as per the alcoholic liver care plan. Hepatologists may advise the patient to follow an alcoholic liver disease diet inclusive of fiber and protein. If the condition of the patient gets worsened, then the hepatologist may have to suggest a liver transplant surgery.

Dr. Nivedita Pandey is one of the best liver specialist doctors in Patna, Bihar. She is a well-renowned liver specialist doctor in Delhi, the best stomach doctor in Patna, the best gastroenterologist in Jammu, and a notable stomach doctor in Faridabad. Now, you can sway off all your gastroenterological worries online by booking an online gastroenterologist consultation with one of the best hepatologists in India. She is a liver specialist in Delhi NCR, one of the finest gastroenterologists in Jhansi and Jammu, and an acidity specialist doctor in Patna. Dr. Pandey’s gastroenterologist live chat has also helped people in several ways.

Case Review

This alcoholic liver case study presents a patient with liver cirrhosis. A 43-year-old man was brought into the hospital with a complaints of loss of appetite, abdominal distention, and arrhythmia. He also experienced itchy skin and blood in the stool. The patient’s family rushed him into the hospital, and he was in a half-conscious state. The patient was taken to the emergency room for evaluation. As told by the family, he had a past medical history and was a heavy alcohol consumer. This alcoholic liver case history consisted of various medical ailments like fatty liver, asthma, tuberculosis, malnutrition, hypertension, and hepatitis C. The patient had a heart attack three years back and stented for the same. Due to his health conditions, he was on several medications. In the emergency room, when the patient was under observation by a stomach specialist doctor in Patna and her team, they were able to diagnose from his symptoms that it was alcoholic liver cirrhosis. The patient went for a few scans including, a liver function test, liver ultrasound, and endoscopy along with CT, blood test, and urine tests.

Case Discussion