Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 25 January 2021

Online education in the post-COVID era

- Barbara B. Lockee 1

Nature Electronics volume 4 , pages 5–6 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

139k Accesses

210 Citations

337 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

The coronavirus pandemic has forced students and educators across all levels of education to rapidly adapt to online learning. The impact of this — and the developments required to make it work — could permanently change how education is delivered.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the world to engage in the ubiquitous use of virtual learning. And while online and distance learning has been used before to maintain continuity in education, such as in the aftermath of earthquakes 1 , the scale of the current crisis is unprecedented. Speculation has now also begun about what the lasting effects of this will be and what education may look like in the post-COVID era. For some, an immediate retreat to the traditions of the physical classroom is required. But for others, the forced shift to online education is a moment of change and a time to reimagine how education could be delivered 2 .

Looking back

Online education has traditionally been viewed as an alternative pathway, one that is particularly well suited to adult learners seeking higher education opportunities. However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has required educators and students across all levels of education to adapt quickly to virtual courses. (The term ‘emergency remote teaching’ was coined in the early stages of the pandemic to describe the temporary nature of this transition 3 .) In some cases, instruction shifted online, then returned to the physical classroom, and then shifted back online due to further surges in the rate of infection. In other cases, instruction was offered using a combination of remote delivery and face-to-face: that is, students can attend online or in person (referred to as the HyFlex model 4 ). In either case, instructors just had to figure out how to make it work, considering the affordances and constraints of the specific learning environment to create learning experiences that were feasible and effective.

The use of varied delivery modes does, in fact, have a long history in education. Mechanical (and then later electronic) teaching machines have provided individualized learning programmes since the 1950s and the work of B. F. Skinner 5 , who proposed using technology to walk individual learners through carefully designed sequences of instruction with immediate feedback indicating the accuracy of their response. Skinner’s notions formed the first formalized representations of programmed learning, or ‘designed’ learning experiences. Then, in the 1960s, Fred Keller developed a personalized system of instruction 6 , in which students first read assigned course materials on their own, followed by one-on-one assessment sessions with a tutor, gaining permission to move ahead only after demonstrating mastery of the instructional material. Occasional class meetings were held to discuss concepts, answer questions and provide opportunities for social interaction. A personalized system of instruction was designed on the premise that initial engagement with content could be done independently, then discussed and applied in the social context of a classroom.

These predecessors to contemporary online education leveraged key principles of instructional design — the systematic process of applying psychological principles of human learning to the creation of effective instructional solutions — to consider which methods (and their corresponding learning environments) would effectively engage students to attain the targeted learning outcomes. In other words, they considered what choices about the planning and implementation of the learning experience can lead to student success. Such early educational innovations laid the groundwork for contemporary virtual learning, which itself incorporates a variety of instructional approaches and combinations of delivery modes.

Online learning and the pandemic

Fast forward to 2020, and various further educational innovations have occurred to make the universal adoption of remote learning a possibility. One key challenge is access. Here, extensive problems remain, including the lack of Internet connectivity in some locations, especially rural ones, and the competing needs among family members for the use of home technology. However, creative solutions have emerged to provide students and families with the facilities and resources needed to engage in and successfully complete coursework 7 . For example, school buses have been used to provide mobile hotspots, and class packets have been sent by mail and instructional presentations aired on local public broadcasting stations. The year 2020 has also seen increased availability and adoption of electronic resources and activities that can now be integrated into online learning experiences. Synchronous online conferencing systems, such as Zoom and Google Meet, have allowed experts from anywhere in the world to join online classrooms 8 and have allowed presentations to be recorded for individual learners to watch at a time most convenient for them. Furthermore, the importance of hands-on, experiential learning has led to innovations such as virtual field trips and virtual labs 9 . A capacity to serve learners of all ages has thus now been effectively established, and the next generation of online education can move from an enterprise that largely serves adult learners and higher education to one that increasingly serves younger learners, in primary and secondary education and from ages 5 to 18.

The COVID-19 pandemic is also likely to have a lasting effect on lesson design. The constraints of the pandemic provided an opportunity for educators to consider new strategies to teach targeted concepts. Though rethinking of instructional approaches was forced and hurried, the experience has served as a rare chance to reconsider strategies that best facilitate learning within the affordances and constraints of the online context. In particular, greater variance in teaching and learning activities will continue to question the importance of ‘seat time’ as the standard on which educational credits are based 10 — lengthy Zoom sessions are seldom instructionally necessary and are not aligned with the psychological principles of how humans learn. Interaction is important for learning but forced interactions among students for the sake of interaction is neither motivating nor beneficial.

While the blurring of the lines between traditional and distance education has been noted for several decades 11 , the pandemic has quickly advanced the erasure of these boundaries. Less single mode, more multi-mode (and thus more educator choices) is becoming the norm due to enhanced infrastructure and developed skill sets that allow people to move across different delivery systems 12 . The well-established best practices of hybrid or blended teaching and learning 13 have served as a guide for new combinations of instructional delivery that have developed in response to the shift to virtual learning. The use of multiple delivery modes is likely to remain, and will be a feature employed with learners of all ages 14 , 15 . Future iterations of online education will no longer be bound to the traditions of single teaching modes, as educators can support pedagogical approaches from a menu of instructional delivery options, a mix that has been supported by previous generations of online educators 16 .

Also significant are the changes to how learning outcomes are determined in online settings. Many educators have altered the ways in which student achievement is measured, eliminating assignments and changing assessment strategies altogether 17 . Such alterations include determining learning through strategies that leverage the online delivery mode, such as interactive discussions, student-led teaching and the use of games to increase motivation and attention. Specific changes that are likely to continue include flexible or extended deadlines for assignment completion 18 , more student choice regarding measures of learning, and more authentic experiences that involve the meaningful application of newly learned skills and knowledge 19 , for example, team-based projects that involve multiple creative and social media tools in support of collaborative problem solving.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, technological and administrative systems for implementing online learning, and the infrastructure that supports its access and delivery, had to adapt quickly. While access remains a significant issue for many, extensive resources have been allocated and processes developed to connect learners with course activities and materials, to facilitate communication between instructors and students, and to manage the administration of online learning. Paths for greater access and opportunities to online education have now been forged, and there is a clear route for the next generation of adopters of online education.

Before the pandemic, the primary purpose of distance and online education was providing access to instruction for those otherwise unable to participate in a traditional, place-based academic programme. As its purpose has shifted to supporting continuity of instruction, its audience, as well as the wider learning ecosystem, has changed. It will be interesting to see which aspects of emergency remote teaching remain in the next generation of education, when the threat of COVID-19 is no longer a factor. But online education will undoubtedly find new audiences. And the flexibility and learning possibilities that have emerged from necessity are likely to shift the expectations of students and educators, diminishing further the line between classroom-based instruction and virtual learning.

Mackey, J., Gilmore, F., Dabner, N., Breeze, D. & Buckley, P. J. Online Learn. Teach. 8 , 35–48 (2012).

Google Scholar

Sands, T. & Shushok, F. The COVID-19 higher education shove. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/3o2vHbX (16 October 2020).

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. & Bond, M. A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/38084Lh (27 March 2020).

Beatty, B. J. (ed.) Hybrid-Flexible Course Design Ch. 1.4 https://go.nature.com/3o6Sjb2 (EdTech Books, 2019).

Skinner, B. F. Science 128 , 969–977 (1958).

Article Google Scholar

Keller, F. S. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1 , 79–89 (1968).

Darling-Hammond, L. et al. Restarting and Reinventing School: Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond (Learning Policy Institute, 2020).

Fulton, C. Information Learn. Sci . 121 , 579–585 (2020).

Pennisi, E. Science 369 , 239–240 (2020).

Silva, E. & White, T. Change The Magazine Higher Learn. 47 , 68–72 (2015).

McIsaac, M. S. & Gunawardena, C. N. in Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (ed. Jonassen, D. H.) Ch. 13 (Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1996).

Irvine, V. The landscape of merging modalities. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/2MjiBc9 (26 October 2020).

Stein, J. & Graham, C. Essentials for Blended Learning Ch. 1 (Routledge, 2020).

Maloy, R. W., Trust, T. & Edwards, S. A. Variety is the spice of remote learning. Medium https://go.nature.com/34Y1NxI (24 August 2020).

Lockee, B. J. Appl. Instructional Des . https://go.nature.com/3b0ddoC (2020).

Dunlap, J. & Lowenthal, P. Open Praxis 10 , 79–89 (2018).

Johnson, N., Veletsianos, G. & Seaman, J. Online Learn. 24 , 6–21 (2020).

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M. & Garrison, D. R. Assessment in Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of Inquiry (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2013).

Conrad, D. & Openo, J. Assessment Strategies for Online Learning: Engagement and Authenticity (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2018).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA

Barbara B. Lockee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Barbara B. Lockee .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lockee, B.B. Online education in the post-COVID era. Nat Electron 4 , 5–6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Download citation

Published : 25 January 2021

Issue Date : January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A comparative study on the effectiveness of online and in-class team-based learning on student performance and perceptions in virtual simulation experiments.

BMC Medical Education (2024)

Leveraging privacy profiles to empower users in the digital society

- Davide Di Ruscio

- Paola Inverardi

- Phuong T. Nguyen

Automated Software Engineering (2024)

Growth mindset and social comparison effects in a peer virtual learning environment

- Pamela Sheffler

- Cecilia S. Cheung

Social Psychology of Education (2024)

Nursing students’ learning flow, self-efficacy and satisfaction in virtual clinical simulation and clinical case seminar

- Sunghee H. Tak

BMC Nursing (2023)

Online learning for WHO priority diseases with pandemic potential: evidence from existing courses and preparing for Disease X

- Heini Utunen

- Corentin Piroux

Archives of Public Health (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Advertisement

Online learning in higher education: exploring advantages and disadvantages for engagement

- Published: 03 April 2018

- Volume 30 , pages 452–465, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Amber D. Dumford 1 &

- Angie L. Miller ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5828-235X 2

62k Accesses

415 Citations

32 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

As the popularity of online education continues to rise, many colleges and universities are interested in how to best deliver course content for online learners. This study explores the ways in which taking courses through an online medium impacts student engagement, utilizing data from the National Survey of Student Engagement. Data was analyzed using a series of ordinary least squares regression models, also controlling for relevant student and institutional characteristics. The results indicated numerous significant relationships between taking online courses and student engagement for both first-year students and seniors. Those students taking greater numbers of online courses were more likely to engage in quantitative reasoning. However, they were less likely to engage in collaborative learning, student-faculty interactions, and discussions with diverse others, compared to their more traditional classroom counterparts. The students with greater numbers of online courses also reported less exposure to effective teaching practices and lower quality of interactions. The relationship between these engagement indicators and the percentage of classes taken online suggests that an online environment might benefit certain types of engagement, but may also be somewhat of a deterrent to others. Institutions should consider these findings when designing online course content, and encourage faculty to contemplate ways of encouraging student engagement across a variety of delivery types.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Adoption of online mathematics learning in Ugandan government universities during the COVID-19 pandemic: pre-service teachers’ behavioural intention and challenges

The impact of artificial intelligence on learner–instructor interaction in online learning

Learning environments’ influence on students’ learning experience in an Australian Faculty of Business and Economics

Allen, E., & Seaman, J. (2013). Changing course: Ten years of tracking online education in the United States . Babson Park, MA: Babson Survey Research Group.

Google Scholar

Anaya, G. (1999). College impact on student learning: Comparing the use of self-reported gains, standardized test scores, and college grades. Research in Higher Education, 40, 499–526.

Article Google Scholar

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Baird, L. (2005). College environments and climates: Assessments and their theoretical assumptions. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, 10, 507–537.

Braten, I., & Streomso, H. I. (2006). Epistemological beliefs, interest, and gender as predictors of Internet-based learning activities. Computers in Human Behavior, 22 (6), 1027–1042.

Cabrera, A. F., Crissman, J. L., Bernal, E. M., Nora, A., Terenzini, P. T., & Pascarella, E. T. (2002). Collaborative learning: Its impact on college students’ development and diversity. Journal of College Student Development, 43 (1), 20–34.

Chen, P. D., Lambert, A. D., & Guidry, K. R. (2010). Engaging online learners: The impact of web-based learning technology on student engagement. Computers & Education, 54, 1222–1232.

Cohen, V. L. (2003). Distance learning instruction: A new model of assessment. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 14 (2), 98–120.

Dominguez, P. S., & Ridley, D. R. (2001). Assessing distance education courses and discipline differences in effectiveness. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 28 (1), 15–19.

Drysdale, J. S., Graham, C. R., Spring, K. J., & Halverson, L. R. (2013). An analysis of research trends in dissertations and theses studying blended learning. Internet and Higher Education, 17, 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.11.003 .

Evans, C. (2014). Twitter for teaching: Can social media be used to enhance the process of learning? British Journal of Educational Technology, 45 (5), 902–915.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Friedman, J. (2014). Online education by discipline: A graduate student’s guide . Retrieved from http://www.usnews.com/education/online-education/articles/2014/09/17/online-education-by-discipline-a-graduate-students-guide .

Han, I., & Shin, W. S. (2016). The use of a mobile learning management system and academic achievement of online students. Computers & Education, 102, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.07.003 .

Hayek, J. C., Carini, R. M., O’Day, P. T., & Kuh, G. D. (2002). Triumph or tragedy: Comparing student engagement levels of members of Greek-letter organizations and other students. Journal of College Student Development, 43 (5), 643–663.

Henrie, C. R., Halverson, L. R., & Graham, C. R. (2015). Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated learning: A review. Computers & Education, 90, 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.09.005 .

Hu, S., & Kuh, G. D. (2001). Computing experience and good practices in undergraduate education: Does the degree of campus ‘‘wiredness” matter? Education Policy Analysis Archives, 9 (49). http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v9n49.html .

Jacob, S., & Radhai, S. (2016). Trends in ICT e-learning: Challenges and expectations. International Journal of Innovative Research & Development, 5 (2), 196–201.

Junco, R. (2012). The relationship between frequency of Facebook use, participation in Facebook activities, and student engagement. Computers & Education, 58 (1), 162–171.

Junco, R., Elavsky, C. M., & Heiberger, G. (2013). Putting Twitter to the test: Assessing outcomes for student collaboration, engagement, and success. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44 (2), 273–287.

Junco, R., Heiberger, G., & Loken, E. (2010). The effect of Twitter on college student engagement and grades. Journal of Computer Assisted learning . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00387.x .

Kent, C., Laslo, E., & Rafaeli, S. (2016). Interactivity in online discussions and learning outcomes. Computers & Education, 97, 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.03.002 .

Kim, K. J., & Bonk, C. J. (2006). The future of online teaching and learning in higher education: The survey says…. Educause Quarterly, 4, 22–30.

Kuh, G. D. (2001). The National Survey of Student Engagement: Conceptual framework and overview of psychometric properties . Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, Center for Postsecondary Research.

Kuh, G. D., & Hu, S. (2001a). The effects of student-faculty interaction in the 1990s. Review of Higher Education, 24 (3), 309–332.

Kuh, G. D., & Hu, S. (2001b). The relationships between computer and information technology use, student learning, and other college experiences. Journal of College Student Development, 42, 217–232.

McMillan, J. H., & Schumacher, S. (2001). Research in education: A conceptual introduction . New York: Longman.

Miller, A. L. (2012). Investigating social desirability bias in student self-report surveys. Educational Research Quarterly, 36 (1), 30–47.

Miller, A. L., Sarraf, S. A., Dumford, A. D., & Rocconi, L. M. (2016). Construct validity of NSSE engagement indicators (NSSE psychometric portfolio report). Bloomington, IN: Center for Postsecondary Research, Indiana University, School of Education. http://nsse.indiana.edu/pdf/psychometric_portfolio/Validity_ConstructValidity_FactorAnalysis_2013.pdf .

Moore, M. G., & Kearsley, G. (2011). Distance education: A systems view of online learning . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Murayama, K., & Elliot, A. J. (2009). The joint influence of personal achievement goals and classroom goal structures on achievement-relevant outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101 (2), 432–447. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014221 .

National Survey of Student Engagement. (2015). NSSE 2015 overview . Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, Center for Postsecondary Research.

Nelson Laird, T. F., Shoup, R., & Kuh, G. D. (2005). Measuring deep approaches to learning using the National Survey of Student Engagement . Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Institutional Research, Chicago, IL. http://nsse.iub.edu/pdf/conference_presentations/2006/AIR2006DeepLearningFINAL.pdf .

Ormrod, J. E. (2011). Human learning (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Pace, C. R. (1980). Measuring the quality of student effort. Current issues in Higher Education, 2, 10–16.

Parsad, B., & Lewis, L. (2008). Distance education at degree-granting Postsecondary Institutions: 2006–2007 (NCES 2009–044). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences. Washington, DC: US Department of Education. http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2009/2009044.pdf .

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students: A third decade of research (Vol. 2). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Pike, G. R. (1995). The relationship between self-reports of college experiences and achievement test scores. Research in Higher Education, 36 (1), 1–22.

Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16 (4), 385–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-004-0006-x .

Pollack, P. H., & Wilson, B. M. (2002). Evaluating the impact of internet teaching: Preliminary evidence from American national government classes. PS. Political Science and Politics, 35 (3), 561–566.

Pukkaew, C. (2013). Assessment of the effectiveness of internet-based distance learning through the VClass e-Education platform. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 14 (4), 255–276.

Restauri, S. L., King, F. L., & Nelson, J. G. (2001). Assessment of students’ ratings for two methodologies of teaching via distance learning: An evaluative approach based on accreditation . ERIC document 460-148, reports-research (143).

Richardson, J. T. E., Morgan, A., & Woodley, A. (1999). Approaches to studying distance education. Higher Education, 37, 23–55.

Robinson, C. C., & Hullinger, H. (2008). New benchmarks in higher education: Student engagement in online learning. Journal of Education for Business, 84 (2), 101–108.

Serwatka, J. A. (2002). Improving student performance in distance learning courses. Technological Horizons in Education THE Journal, 29 (9), 48–51.

Shuey, S. (2002). Assessing online learning in higher education. Journal of Instruction Delivery Systems, 16, 13–18.

Stallings, D. (2002). Measuring success in the virtual university. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 28, 47–53.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Tess, P. A. (2013). The role of social media in higher education classes (real and virtual)—A literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (3), A60–A68.

Thurmond, V., & Wambach, K. (2004). Understanding interactions in distance education: A review of the literature. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning, 1 , 9–33. http://www.itdl.org/journal/Jan_04/article02.htm .

Tomei, L. A. (2006). The impact of online teaching on faculty load: Computing the ideal class size for online courses. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 14, 531–541.

Umbach, P. D. (2007). How effective are they? Exploring the impact of contingent faculty on undergraduate education. Review of Higher Education, 30 (2), 91–123. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2006.0080 .

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2016). Digest of education statistics, 2014 (NCES 2016-006), Table 311.15. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=80 .

Whitley, B. E. (2002). Principles of research in behavioral science (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routlegde.

Wijekumar, K., Ferguson, L., & Wagoner, D. (2006). Problems with assessment validity and reliability in wed-based distance learning environments and solutions. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 15 (2), 199–215.

Wojciechowski, A., & Palmer, L. B. (2005). Individual student characteristics: Can any be predictors of success in online classes? Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 8 (2), 13.

Wu, W., Wu, Y. J., Chen, C., Kao, H., & Lin, C. (2012). Review of trends from mobile learning studies: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 59, 817–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.03.016 .

Xu, D., & Smith Jaggars, S. (2013). Adaptability to online learning: Differences across types of students and academic subject areas (CCRC Working Paper). New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University. Retrieved from http://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/adaptability-to-online-learning.html .

Zhou, L., & Zhang, D. (2008). Web 2.0 impact on student learning process. In K. McFerrin et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of society for information technology and teacher education international conference (pp. 2880–2882). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of South Florida, 4202 E Fowler Ave, EDU 105, Tampa, FL, 33620, USA

Amber D. Dumford

Indiana University Bloomington, 1900 E. 10th St, Suite 419, Bloomington, IN, 47406, USA

Angie L. Miller

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Angie L. Miller .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dumford, A.D., Miller, A.L. Online learning in higher education: exploring advantages and disadvantages for engagement. J Comput High Educ 30 , 452–465 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-018-9179-z

Download citation

Published : 03 April 2018

Issue Date : December 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-018-9179-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Online education

- Higher education

- Student engagement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, faculty’s and students’ perceptions of online learning during covid-19.

- 1 Department of English Language and Translation, Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan

- 2 Department of Political Science, Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan

- 3 Department of Self-Development Skills, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia

COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted teaching in a vriety of institutions. It has tested the readiness of academic institutions to deal with such abrupt crisis. Online learning has become the main method of instruction during the pandemic in Jordan. After 4 months of online education, two online surveys were distributed to investigate faculty’s and Students’ perception of the learning process that took place over that period of time with no face to face education. In this regard, the study aimed to identify both faculty’s and students’ perceptions of online learning, utilizing two surveys one distributed to 50 faculty members and another 280 students were selected randomly to explore the effectiveness, challenges, and advantages of online education in Jordan. The analysis showed that the common online platforms in Jordan were Zoom, Microsoft Teams offering online interactive classes, and WhatsApp in communication with students outside the class. The study found that both faculty and students agreed that online education is useful during the current pandemic. At the same time, its efficacy is less effective than face-to-face learning and teaching. Faculty and students indicated that online learning challenges lie in adapting to online education, especially for deaf and hard of hearing students, lack of interaction and motivation, technical and Internet issues, data privacy, and security. They also agreed on the advantages of online learning. The benefits were mainly self-learning, low costs, convenience, and flexibility. Even though online learning works as a temporary alternative due to COVID-19, it could not substitute face-to-face learning. The study recommends that blended learning would help in providing a rigorous learning environment.

Introduction

COVID-19 was declared as a global pandemic in March 2020 ( WHO, 2020 ). It impacted all walks of life including education. It led to the closure of schools and universities. This closure put a considerable burden on the academic institution to cope with the unprecedented shift from traditional to online learning. The outbreak triggered new ways of teaching online. Most countries imposed restrictions, where the medium of education has shifted into either synchronous or asynchronous modes. The world has seen the most extensive educational systems disruption in history in more than 190 countries worldwide. The closure of the academic institutions has impacted up to 99% of the world the student population in the lower lower-middle-income ( The Economic Times, 2020 ). The outbreak of COVID-19 established partial or complete lockdown, where people are forced to stay home. The higher education institutions’ closure demands online learning, where the course material is taught. For instance, Jordan, an Arab country, has replaced face-to-face instruction with online learning platforms to control the outbreak’s spread. The government had imposed a national lockdown, which resulted in universities’ and schools’ closure.

Most global institutions opt to use synchronous and asynchronous online teaching methods: synchronous is where faculty and their students meet in a pre-scheduled time as a part of interactive learning classes, while the asynchronous method refers to the Faculty giving the course without interaction with the students. There is no interaction between the faculty and students. Asynchronous modes of online learning suit students to access online material whenever they like ( EasyLMS, 2021 ). Faculty are the role players in making learning enjoyable, shaping students’ attitudes and personalities, and helping students pass. COVID-19 spreads online learning culture across the culture ( Beteille et al., 2020 ). COVID-19 forced the shift to online learning, but some universities in underdeveloped countries are not adequately equipped to teach online efficiently. Moreover, the faculty’s training is different globally between high-income, middle, and lower income countries. Another major obstacle is the Internet connectivity for underprivileged students. It is a de facto that face-to-face instruction is more efficient than online and the complete shift to online during COVID-19 makes it necessary to investigate the perception of faculty and students on online learning to identify the advantages and disadvantages, and challenges of online learning.

While the whole world is facing much trouble in the last few months, it has been difficult for the world, and the impact of online learning has been significantly observed on faculty members and students in particular. Teaching and learning online has a wide range of advantages, yet poses some challenges. It makes the process of learning for students’ comfort due to time flexibility in attending classes. However, online learning acts as a barrier to the engagement of students in real class activities. Moreover, students lack the influence of peer learning. These challenges also leave an impact on student’s personalities and prevent them from taking their turns. Additionally, the faculty’s role is to teach, monitor, and provide advice for students on both academic and personal levels. The current crisis, COVID-19, highlights the role of the Internet and technology in all walks of life including education. The pandemic has shown the role of online education in coping with abrupt crises, and therefore it is significant to understand both faculty’s and student’s perceptions concerning online classes.

Online Learning

There is a considerable development in education, where the mode of instruction has been changed from teacher-centered education to student-centered education. In teacher-centered education, the teacher plays a role as the source of education, and students are recipients of his/her knowledge. In contrast, student-centered education emphasizes the role of students in knowledge production in the class. In a student-centered approach, the teachers’ role turns to “helper to students who establish and enforce their own rules. Teachers respond to student assignments and encourage them to provide alternative/additional responses. Student-centered instruction has currently benefited many new technologies by using the internet and other advanced technological tools to share, transfer, and extend knowledge” ( Hancock, 2002 ). Online learning has become a part of the 21st century as it makes use of online platforms. E-learning is defined as using online platform technologies and the Internet to enhance learning and provide users with access to online services and services ( Ehlers and Pawlowski, 2006 ).

Internet and education have integrated to provide users with the necessary skills in the future ( Haider and Al-Salman, 2020 ). A study by Stec et al., 2020 indicated that online teaching has three main approaches, namely, enhanced, blended learning, and online approach. Enhanced learning uses the intensive use of technology to ensure innovative and interactive instruction. Blended learning mixes both face-to-face and online education. The online approach indicates that the course content is delivered online. Online education is convenient for students, where they can access online materials for 24 h ( Stern, 2020 ). Online education turns education to be student-centered, where students take part in the learning process, and teachers work as supervisors and guides for students ( Al-Salman et al., 2021 ).

Online platforms have different tools to facilitate conducting online interactive classes to reduce students’ loss. Online education platforms are designed to share information and coordinate class activities ( Martín-Blas and Serrano-Fernández, 2009 ). There are most famous prominent interactive online tools: DingTalk (interactive online platform designed by Alibaba Group), Hangouts Meet (video calls tool), Teams (chat, interactive meetings, video, and audio calls), Skype (video and audio calls), WeChat Work (video sharing and calls designed for the Chinese), WhatsApp (video and audio calls, chat, and content share), and Zoom (video and audio calls, and collaboration features) ( UNESCO, 2020 ).

Online Learning Before COVID-19 in the Arab Region

Online learning works as an alternative for face-to-face education during COVID-19. It becomes the 21st efficient tool for online learning. The online learning experience is different globally. Some countries have the required resources to facilitate learning, while many others do not have the equipment available in high and middle-income countries. In the Arab region, some countries such as Jordan, KSA, Qatar, Emirates, Bahrain, and Kuwait are relatively developed compared to other Arab countries. During COVID-19, most Arab higher education institutions shifted to synchronous and asynchronous online learning methods. Jordan, an Arab country, initiated online learning in the Ministry of Education and Ministries of Planning and Information Technology in 2002 ( Dirani and Yoon, 2009 ). They worked to start the online experience by shifting instruction mode from traditional to virtual. In a similar vein, Talal Abu-Ghazaleh University launched the first online platform to facilitate recruiting and enrolling new students and conducting virtual classes in 2012.

Moreover, Jordan’s university established synchronous blended learning, where some theoretical courses are conducted online, while practical times are campus oriented. Jordan was one of the countries to respond to the crisis in creating an online platform, Darsak, to facilitate online learning for schools ( Audah et al., 2020 ). However, online learning was not considered as an education modality in Jordan before this crisis.

Online Learning During COVID-19

COVID-19 was classified by world health organization (WHO) as a pandemic disease on March 11, 2020. On March 19, emergency state was declared as a response to prevent the spread of COVID-19. It is followed by a curfew, which lasted for 2 months. The mode of education has turned online due to the closure of universities. The closure of universities brings the importance of having good infrastructure and the readiness to conduct online classes. Jordan is considered as one of the leading countries in Internet infrastructure and has a highly developed Middle East region ( Jordan Times, 2017 ). Online learning becomes a tool to prevent the outbreak and ensure social distancing. Online education has useful learning tools and grants 24/7 access to education platforms around the clock at their time preferences. It also offers flexibility, regardless of place and time. It also gives students questions, answers freely, and provides feedback on the assigned courses’ content ( Rosell, 2020 ).

Literature and Research Questions

The Author’s literature review has uncovered that the faculty and students shall verify online learning’s importance during COVID-19. Therefore, the present study aims to bridge the gap by scrutinizing faculty and students’ perceptions of online learning. To be specific, it raises the following questions:

1. What is the opinion and perceptions of the faculty in terms of;

a. Online platform used and teaching experience.

b. Attitudes of computer literacy and online class preparations.

c. Attitude of the effectiveness of online education.

2. What is the student’s opinion and perceptions on the Effectiveness of online teaching & learning during covid-19 pandemic?

3. What are the challenges of online teaching & learning during the covid-19 pandemic?

4. What are the advantages, challenges, and disadvantages of online learning?

Literature Review

Technology has a firm-established role in education experience in the last decade ( Almahasees and Jaccomard, 2020 ). Methods, techniques, and strategies of education have been revised to deal with dramatic changes in technology. The technological enterprises have designed several online platforms, which are driven by the integration of technology in all walks of life ( Al-Azawei et al., 2017 ; Englund et al., 2017 ; Santos et al., 2019 ). Technology has become part of our social, business, and educational life’. The use of the Internet has a vital role in disseminating knowledge via online classes ( Silva and Cartwright, 2017 ).

During COVID-19, education has been shifted into the techno-economic culture. The shift should associate with plans to reduce this shift’s impact on the normal learning process ( Gurukkal, 2020 ). The change to online in higher education entails reshaping our view regarding higher education, including institutions and students’ needs. For instance, theoretical courses can be taught online. In contrast, the practical courses should be conducted face to face to ensure best teaching practices in monitoring and guiding students. Therefore, technology can make larger classes flexible and suiting students’ needs ( Siripongdee et al., 2020 ).

Research on faculty members’ perceptions and attitudes toward online learning emphasized the role of instructors in facilitating communication and earning with students. Instructors acknowledged the content expertise and instructional design as the factors in the success of online learning. Similarly, the call for staff and student training is mandatory for online learning success ( Cheng and Chau, 2016 ).

The mode of education has turned into student-centered education, where students became independent learners. This is considered as an advantage as face-to-face instruction was teacher-centered education, where students receive their education from their instructors. Online learning initiated students’ role in using additional resources to discover their abilities as independent learners ( Roach and Lemasters, 2006 ). The comparison between students’ attitudes toward teaching the same interactive courses in online and face to face is similar. It is found that students performed equally at the same interactive courses in online and face-to-face instruction. Face-to-face instruction’s success depends on regular class attendance, while the interactive classes relied on completing interactive worksheets. Therefore, online and face-to-face success is based on curriculum structure, mode of delivery, and completion rate ( Nemetz et al., 2017 ). The COVID-19 outbreak shifts face-to-face education to online during the lockdown. This shift helps faculty integrate advanced technological skills in their teaching, which benefit students ( Isaeva et al., 2020 ).

Online learning has been considered a useful tool for learning, cost-effectiveness, flexibility, and the possibility of providing world-class education ( Jeffcoat Bartley and Golek, 2004 ; Gratton-Lavoie and Stanley, 2009 ; De La Varre et al., 2010 ). A study by Li and Lalani (2020) indicated that COVID-19 had brought change to the status of learning in the 21st century. The instruction mode has been changed at both schools and higher academic from face-to-face instruction to online instruction ( Strielkowski, 2020 ). However, this rapid change tests the capacity of institutions to cope with such crises. Many countries did not expect such a complete shift to be online, and therefore their working staff and students are not trained enough for this dramatic change.

Online learning works as a tool to overcome abrupt crises ( Ayebi-Arthur, 2017 ). Online learning is considered as an entertaining way to learn. It has a positive impact on both students and teachers alike. Both faculty and students have optimistic opinions about online classes ( Kulal and Nayak, 2020 ). Moreover, there is a positive correlation between students and faculty in their perception of teaching and learning ( Seok et al., 2010 ). Faculty and students of engineering specialties incurred that theoretical engineering subjects can be taught online, while teaching practical courses online are less effective and should be conducted at engineering labs ( Kinney et al., 2012 ). Similarly, students’ and faculty perceptions were marginalized differently in teaching laboratory courses online ( Beck and Blumer, 2016 ).

Faculty and students encountered challenges such as technology, workload, digital competence, and compatibility. They concluded that education would become hybrid, face-to-face, and online instructions ( Adedoyin and Soykan, 2020 ). A study to verify the usage of online learning platforms in teaching clinical medical courses was conducted. They found that the rate of student satisfaction is 26% ( Al-Balas et al., 2020 ). There is a slew of advantages and disadvantages of online learning. The benefits include efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and 24 h access, while the disadvantages are technical issues, lack of interaction, and training ( Gautam, 2020 ). Rayan, 2020 proposed ways to overcome the disadvantages of online learning by encouraging shy students to participate and provoke students’ online class attendance. Understanding such issues will help to deliver adequate online education. Online encourages shy students to participate and improve students’ attendance, while it also triggers a lack of social interaction that affects students.

Online learning has a vital role in learning during the crisis. Moreover, having properly maintained the technical infrastructure is required for its success at schools and universities ( Nikdel Teymori and Fardin, 2020 ). Dhawan, 2020 scrutinizes online learning’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT). He shows that crisis highlights the role of technology competency in dealing with the global crisis and facilitating learning. Therefore, schools should train students with the necessary IT skills. Another study was conducted on male and female students’ satisfaction in using E-learning portals in Malaysia. He found that there is a significant relationship between the user’s satisfaction and E-learning. The satisfaction rate by both participants depends on E-service quality and the information provided ( Shahzad et al., 2020 ). The advantages of online learning are as follows: flexibility, easy access, and interaction between learners and their professors ( Strayer University, 2020 ). The role and advantages of online learning have accentuated that online learning has challenges as data privacy. Students’ private information is at risk since they use their computers and mobile phones to access online portals. Universities should educate their staff and students about cybersecurity and data privacy ( Luxatia, 2020 ).

Methodology

Participants.

The population of the study was instructors and students at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Fifty faculty members and 280 students were selected randomly from this population, which is deemed significant to provide useful feedback on both faculty’s and students’ perceptions of online learning.

The study used two online surveys, which is delivered to participants in the period between September 15 and November 15 during the closure of universities in Jordan to control the spread of COVID-19. The online two surveys were created Google Forms and sent to the faculty and students through emails, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp messages, and LinkedIn to have social distancing. Thirty-four male and fifteen female members of Faculty participated in the survey.

Thirty-eight participants hold Ph.D. and 11 master’s degrees. The mean of faculty ranges from 31 to 50 years old with an standard deviation (SD) of 1.00224. 47 members of the Faculty teach at university, while three members of the Faculty teach at college. Seven of the participants were professors, 11 associate professors, 18 assistant professors, nine lecturers, and four teaching assistants.

A total of 280 were undergraduate students. Eighty-eight were males, and 192 were females. As for the major, 175 were studying theoretical majors and 105 were studying in practical disciplines, 237 of them live in urban areas, and 43 live in rural areas. Of these, 151 were using mobile to access online classes and 106 were using laptops, while 25 of the students were using a tablet. One-hundred and forty-nine of the study samples indicated that they had received training in using the online classes, while 131 had received no training.

Data Gathering Instruments

Two online surveys were created by Google Docs. The faculty survey consisted of three parts such as sociodemographic, online education training, and faculty’s perceptions of teaching online effectiveness. On the other hand, the students’ survey consisted of four parts, namely, sociodemographic, students’ perception of online learning’s effectiveness, advantages, and challenges of online learning. The survey was designed in a Likert Scale format for rating statements. Two professors reviewed the two surveys, and proper changes were made before disseminating the two surveys of the participants. Participation in the study was voluntary, and personal information was not gathered. Data were imported into Excel to facilitate SPSS analysis using 25 versions.

Validity and Reliability

Two experts examined the two surveys cross out to validate the survey’s design. Their comments are taken into account of omitting some items of the survey due to their irrelevance. As for reliability, Cronbach’s alpha was used as a measure of internal consistency to indicate how the items are closely related. The result of the test showed that the items of the two surveys are consistent. For the faculty survey, the alpha coefficient for the 26 items is 0.889 for the faculty’s survey and 0.896 for the students’ survey, suggesting that the items have relatively high internal consistency. A reliability coefficient of 0.70 or higher is considered “acceptable” in most social science research situations ( Mockovak, 2016 ).

The findings are structured according to sections of the surveys.

Faculty’s Survey

Online teaching experience.

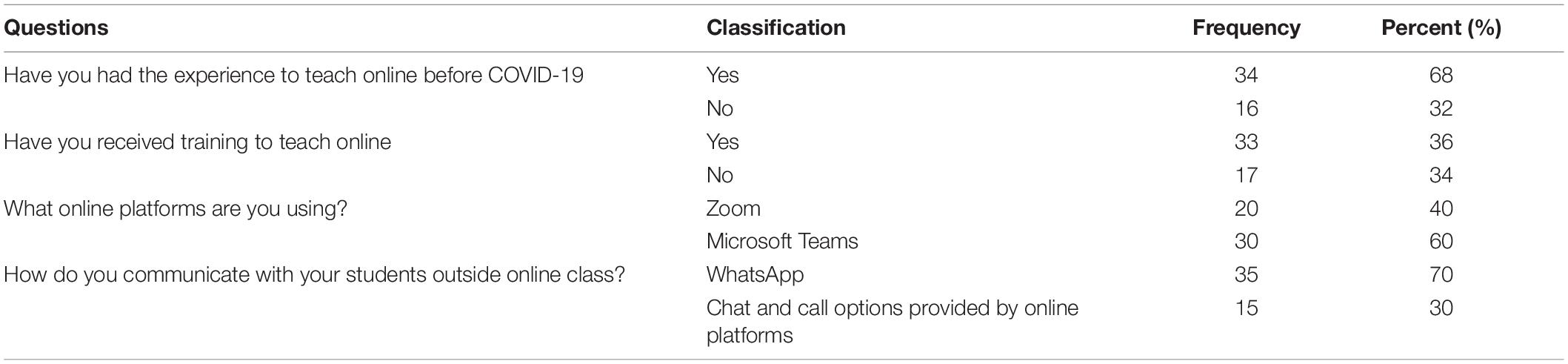

First, the current study scrutinizes the readiness of instructors to teach online. The analysis showed that most of the faculty had previous experience of teaching online before COVID-19, with a percentage of 60%. In contrast, 40% of the surveyed faculty did not have experience in teaching online before COVID-19. Those who had previous experience showed that they had received training to teach online with a percentage of 66%, while 34% did not have any activity to do online learning sessions.

The faculty showed that they used Zoom and Microsoft Teams in their online teaching with 60% for Microsoft Teams and 40% for Zoom. Finally, most participants uncovered that they used WhatsApp with 70% as a medium of communication between the tutor and his students outside the online class time. The second popular platform is Zoom and Microsoft Teams chat and text options with 28%. Moreover, Facebook pages occupied the third rank with 14%, while phone calls were used by 8% of the participants (see Table 1 ).

Table 1. Common online platforms and teaching experiences.

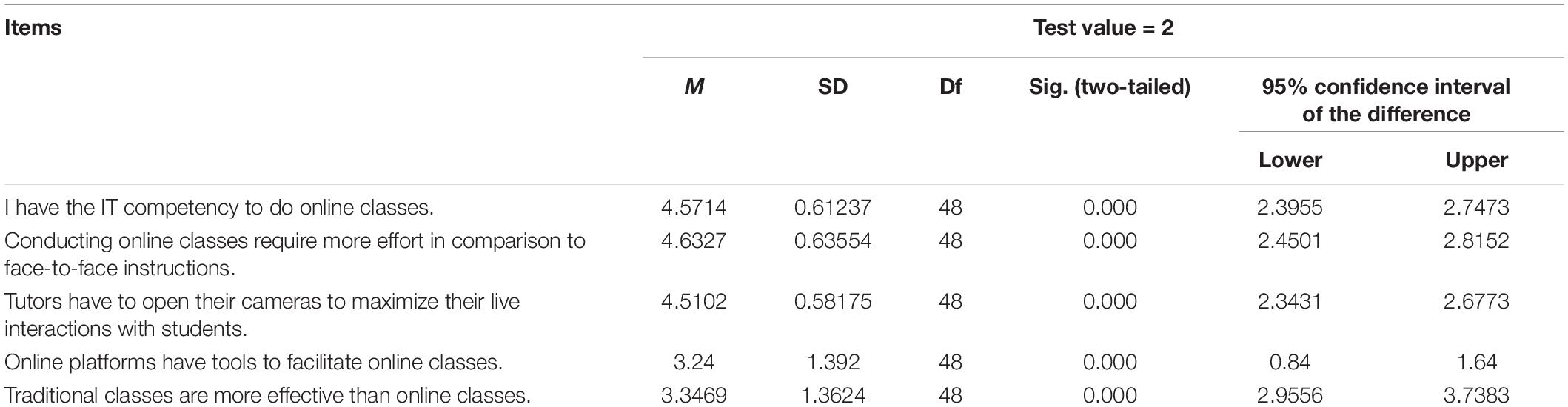

Faculty’s Attitudes of Computer Literacy and Online Class Preparations

The second division of the survey was to identify computer literacy and online class preparation to indicate computer and IT skills as shown in Table 2 . The majority of the respondents agreed that they have enough IT skills to conduct online classes. Moreover, online courses require more effort to do online courses in comparison to face-to-face instruction. Online learning becomes a tool to cope with all catalyst times such as COVID-19.

Table 2. Attitude of IT skills and online class preparations.

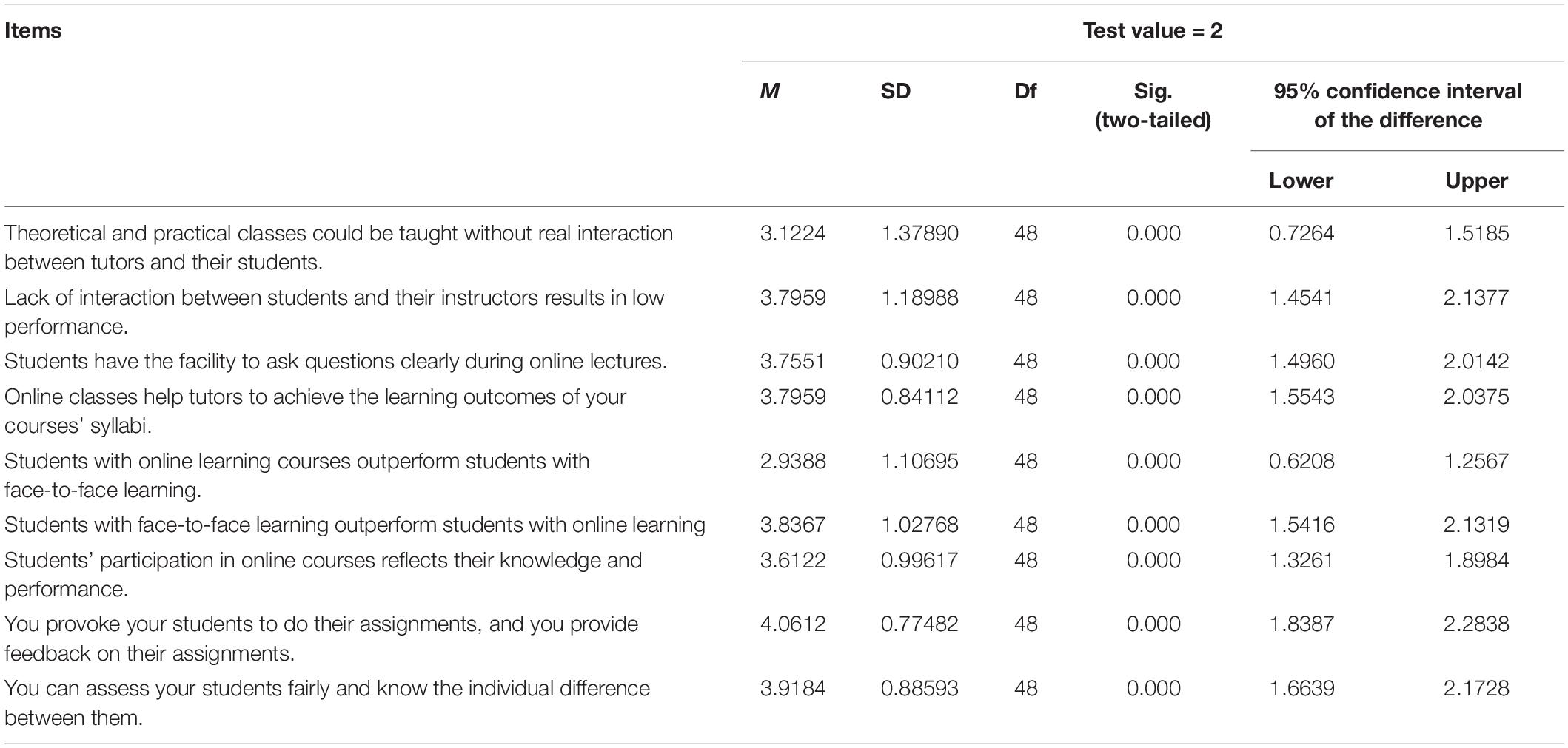

Faculty’s Attitude Toward the Effectiveness of Online Education

The third part of the survey was on the faculty’s attitude toward the effectiveness of online education. The faculty’s responses on the possibility of taking online courses without direct contact between the faculty and their students were centered on neutralism value, which was reflected in the mean scores of the instructors’ responses ( M = 3.1224, SD = 1.37890, p < 0.001). The faculty’s perception was also neutral in the second, third, fourth, and fifth items. The remaining items received agreement value except for the seventh item, which was between neutralism and agreement. These values were statistically significant after Bonferroni was corrected ( p < 0.001) (see Table 3 ).

Table 3. Faculty’s perception of the effectiveness of online teaching.

Students’ Survey

The effectveness of online teaching and learning during the covid-19 pandemic.

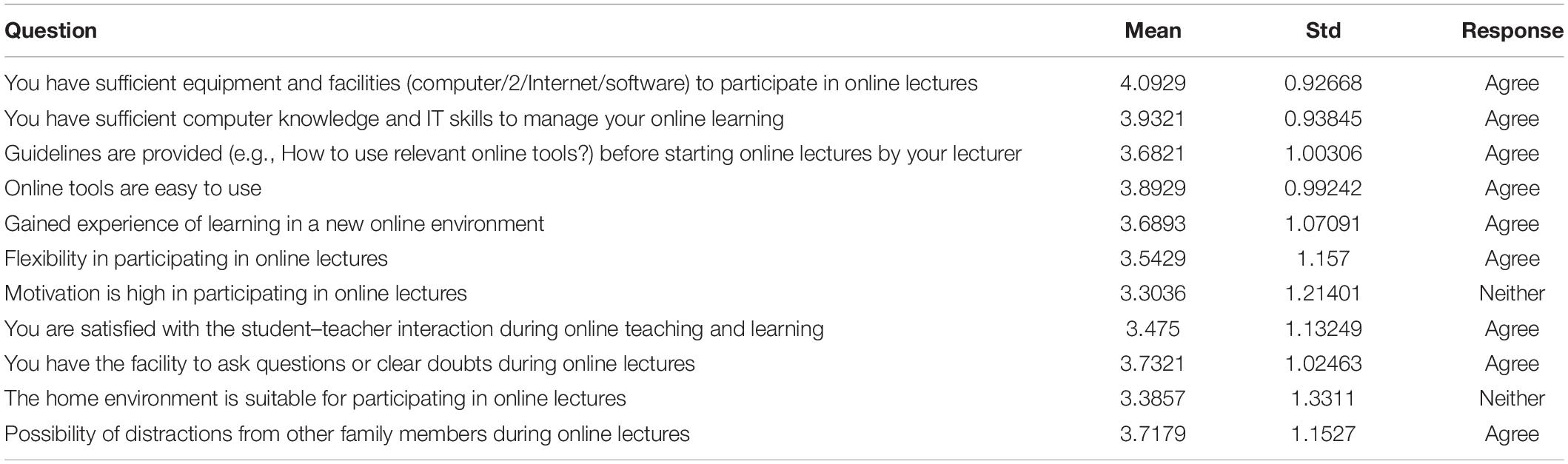

First, the study examined the effectiveness of online learning during COVID-19 (see Table 4 ). The effectiveness of online learning ranges in delivering online learning during the crisis with an SD of 0.67 and 3.548. This means the study participants found online learning useful due to the following reasons: first, students showed that they were provided with efficient online platforms by their institutions to attend lectures. The majority of the study’s respondents showed that they used Microsoft Teams in their online learning process. This is affirmed by Spataro (2020) that Microsoft Teams, as of the end of October 2020, has increased significantly to reach 115 million daily active users. Second, the study’s participants showed that they were trained and had the necessary technological skills to attend online learning. Trained students on online platforms could grasp the learning outcomes of online classes.

Table 4. The perception of online teaching & learning during the covid-19 pandemic.

Moreover, they also showed that they gained new experiences while attending online classes. Third, students emphasize that online learning platforms are easy to use. This means that students have got training to attend online classes, while the academic institutions may share guideline usage with their students. Furthermore, online learning allows flexible time to participate in courses whether they attend the classes synchronously (the exact time of the lecture) and asynchronously (recording the study). Fourth, students accentuated that they were satisfied with the student–teacher interaction during online teaching and learning.

Similarly, the participants showed their agreement on communications and asked questions to clear their doubts during online lectures. On the other hand, the study’s participants responded as neither agree nor disagree (NAND) to the question of whether students’ motivation is high in participating in online lectures. In the same vein, the study’s analysis indicated that they were not able to decide whether their home is suitable to attend online lectures. This means may the students may have got external distractions from their family members while attending online classes.

The research sample agrees on the effectiveness of learning using online classes with a mean of 3.548 (agree) and a standard deviation of 0.647. Most of these opportunities were: you have sufficient equipment and facilities with a mean of 4.09 and a standard deviation of 0.926, and you have adequate computer knowledge and IT skills to manage your online learning with a mean of 3.9321 and a standard deviation of 0.93845, and online tools are easy to use with a mean of 3.8929 and a standard deviation of 0.99242.

The Challenges of Online Teaching and Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The students emphasized that they faced a set of challenges through online learning due to the abrupt shift from face-to-face instruction to online instructions (see Table 5 ). Students’ responses showed that they faced the following challenges. First, students faced a challenge in adapting themselves to online learning. They could have such problems due to technical issues such as the lack of IT competency. Second, students faced a challenge in having proper access to the Internet for many reasons, such as the cost of having a fiber network, which is not affordable for some students. The students also reported that they faced challenges in managing their time and organizing their homework to submit their tasks. Moreover, some of the students have shown that the lack of interaction is also considered a challenge for students, reflecting on their progress and personalities.

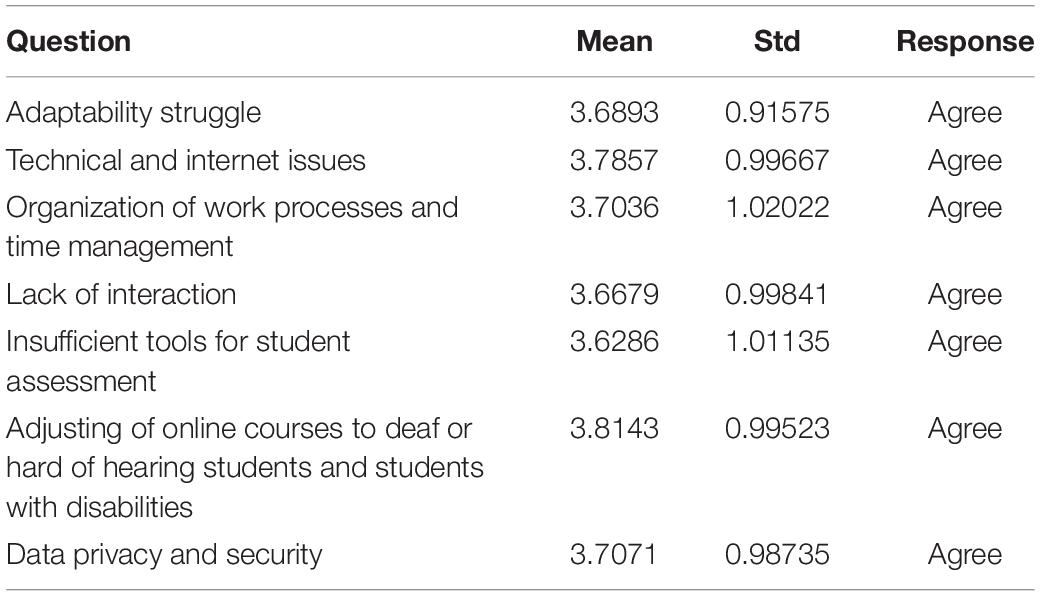

Table 5. The challenges of online teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Moreover, they added that adjusting online classes for students with special needs is a tremendous challenge for deaf, hard of hearing, or disabilities. Furthermore, the study’s respondents also indicated that online learning classes lack insufficient tools for student assessment. Moreover, online learning classes do not let instructors identify the individual differences between students quickly. More importantly, the study’s analysis showed that students were concerned about their data privacy since using their laptops or mobile phones at home, which exposes their data for breach.

It is obvious from Table 5 that the research sample agrees with the learning challenges using online classes with a mean of 3.704 (agree) and a standard deviation of 0.600. The most important of these challenges came for adjusting online courses to deaf or hard of hearing five students and students with disabilities with an average of 3.8143 and a standard deviation of 0.995. Moreover, technical and Internet issues occupied the second rank with a mean of 3.7857 and a standard deviation of 0.996, and the organization of work processes and time management with an average of 3.7036 and a standard deviation of 1.020.

The Advantages of Online Teaching and Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic

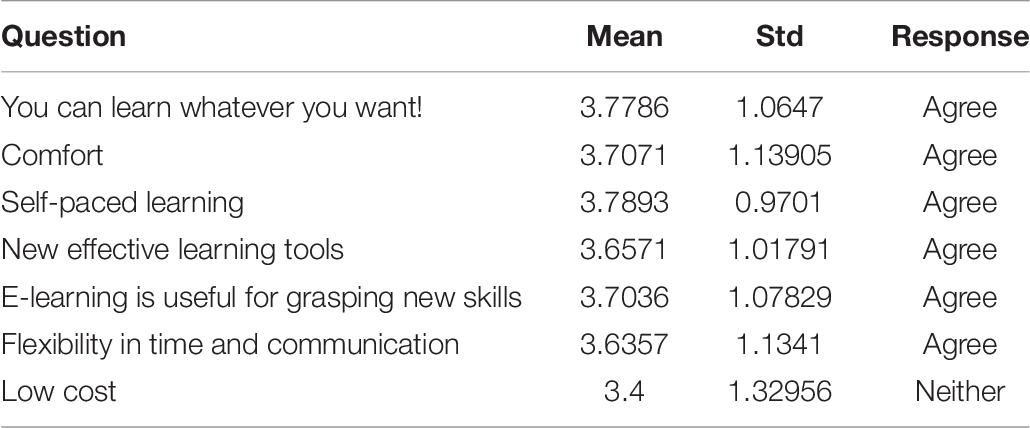

Students opined that online learning ensures that the students will have access to the learning materials based on their convenient time if online learning classes are asynchronously recorded at any time in a day. Moreover, online learning encourages students to take part in the learning process since the instruction mode shifted to focus on student learning (self-paced learning). Students also expressed that online learning helped them to acquire new experiences and skills. It also reduced the cost of traveling to universities and related expenses. Use of traveling resources and other charges as shown in Table 6 .

Table 6. The advantages of online teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 3 indicates that the research sample agrees on the advantages of learning using online classes with an average of 3.673 (agree) and a standard deviation of 0.858. The most important of these features were in (self-paced learning) with a mean of 3.789 and a standard deviation of 0.970, and you can learn whatever you want with a mean of 3.778 and a standard deviation of 1.064, and comfort advantage with a mean of 3.707 and a standard deviation of 1.139.

An analysis of the faculty’s and students’ responses showed their perception of online learning during COVID-19. Faculty were surveyed in terms of online teaching experience, computer literacy, class preparation, and online learning effectiveness. On the other hand, students were studied in terms of online energy, challenges, and advantages. The significant results were interpreted and discussed below.

The analysis showed that 68% of the faculty members had undergone training, while 32% did not have. Exercise is part of development programs provided by universities to equip their staff with the necessary skills. This criterion highlights Faculty Academic Development Centers’ role to have plans to deal with all abrupt crises such as COVID-19. Training programs should not be limited to faculty; they should also involve students. The study found that Zoom and Microsoft Teams were used by the surveyed faculty more than others in conducting virtual classes. Moreover, WhatsApp is the most popular platform for communication between faculty and their students outside classrooms. WhatsApp has been used by more than 2 billion users monthly as of October 2020 ( Statista, 2020 ).

Faculty’s Perception of Computer Literacy and Online Class Preparations

The majority of respondents revealed that they had computer competency before the emergence of COVID-19. This competency helped the faculty to do online classes since IT skills are mandatory for the technology learning environment, as indicated by Li and Lee (2016) . However, the study showed that faculty preferred traditional teaching, face to face, more than online. Face-to-face instruction allows the ability to discuss and have lively guidance for your students. It encourages students’ engagement and reflects positively on the level of students ( Cooke, 2020 ). Therefore, most of the faculty members indicated that online classes’ preparation entails more effort to ensure having interactive online courses.

Faculty’s Perception of the Effectiveness of Online Teaching

The study showed that faculty agreed on the point of online learning To be concise, faculty responses were debatable whether students at online classes can outperform students with face-to-face instruction, as reflected in the item’s mean score ( M = 2.9388). However, the fact is that face-to-face students need the education to excel in online learning results in scores of faculty responses ( M = 3.8367). Faculty also showed that the lack of interaction between students and their instructors might lead to low performance. The faculty were asked if they were able to assess students fairly. The study’s results showed that faculty knew the individual differences between students in online classes. Moreover, online courses helped them to achieve the learning outcomes of their academic syllabi.

Faculty’s Perception of Time and Assignment Management

The analysis revealed that the faculty agreed to make their online sessions short. This finding showed that online classes should not keep the students’ attention and ensure their understanding. If the online course is long, the students may get bored and distracted. As for online class preparation, the participants agreed that online classes require more time than traditional classes. Of course, preparation for online courses entails a longer time than regular classes.

Regarding assignments, the faculty agreed that students should do more assignments in online learning than in traditional classes. Remote teaching requires students to do more tasks than conventional courses to ensure students’ effective practice. Besides, students’ assignments may compensate the students for the lack of direct contact with the tutors.

Online Learning Effectiveness and Challenges During COVID-19

This study highlights undergraduate students’ perceptions, which showed online learning as a flexible and useful learning source during the crisis and some limitations. According to students, online learning is a relaxed and productive source of knowledge. Most of them agreed that online learning helps students 24 h to have access to learning materials asynchronously at any time in a day. This finding correlates with ( Adedoyin and Soykan, 2020 ; Gautam, 2020 ) that online learning offers learners the ability to access online materials around the clock. Moreover, it also encouraged self-learning, where the student plays a role in the process of learning. Online learning reduces the cost of education, where students stay at home and do not pay any charge for traveling and other expenses. More importantly, students learned new experiences through learning, such as time management and self-discipline.

Student Challenges During COVID-19

The analysis revealed that the students faced difficulties when attending online classes. Based on the findings, these challenges lie in students’ struggle to adapt to online courses, lack of direct contact with the faculty, lack of motivation to attend classes, and time management. This list of challenges should be considered by course coordinators and program chairs by offering solutions to these challenges. Students viewed the issue of adapting to the transference from face to face to online instructions as a challenge. This is a great challenge since most countries were not prepared enough to cope with abrupt crises that we did not have before. Students also highlighted that online platforms are not easily adjustable to deaf, hard of hearing, or special needs students. The government should help such students by offering courses provided by specialists of students with special needs. Students also complained about the lack of interaction, reflecting on students’ achievements and their personalities. Technical Internet connectivity issues also affect learning via learning modalities. This challenge can be overcome by improving the speed of the Internet packages provided to students. In this context, governments should offer Internet packages to students at low cost, and the telecommunication companies should help students. Similarly, students were concerned about their data privacy since their information was exposed to breach by external parties, they use their laptops and PCs available at their homes. This requires that universities should educate students about data privacy. They also have to provide students with free firewall programs to protect their data, as also suggested by Luxatia (2020) .

The study scrutinized the perception of the faculty and students on online learning. The study showed that online education is less effective than online classes. The students of online learning face several challenges due to the struggle to complete adaptation to online courses and the lack of interaction between students and their tutors. E-learning platforms motivate student-centered learning, and they are easily adjustable during abrupt crises, such as COVID-19. The universities in Jordan should take part in training students on how to protect their data. Moreover, the government should advise telecommunication companies to improve the students’ services at an affordable price. It is worth mentioning that students with special needs should have synchronous classes, where the special needs specialists should have a role to facilitate such students’ process.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

KM and MA made substantial contributions to the conception, research questions, or design work, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, drafted and revised the work, and proofread the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Adedoyin, O. B., and Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180 [Epub ahead of print].

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Al-Azawei, A., Parslow, P., and Lundqvist, K. (2017). Investigating the effect of learning styles in a blended e-learning system: An extension of the technology acceptance model (TAM). Austral. J. Educ. Technol. 33, 1–23. doi: 10.14742/ajet.2741

Al-Balas, M., Al-Balas, H. I., Jaber, H. M., Obeidat, K., Al-Balas, H., Aborajooh, E. A., et al. (2020). Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: Current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 20:341. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02257-4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Almahasees, Z., and Jaccomard, H. (2020). Facebook translation service (FTS) usage among jordanians during COVID-19 lockdown. Adv. Sci. Tech. Eng. Syst. 5, 514–519. doi: 10.25046/aj050661

Al-Salman, S., and Haider, A. S. (2021). Jordanian University Students’ views on emergency online learning during COVID-19. Online Learn. 25, 286–302. doi: 10.24059/olj.v25i1.2470

Audah, M., Capek, M., and Patil, A. (2020). COVID-19 and Digital Learning Preparedness in Jordan. Available online at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/arabvoices/covid-19-and-digital-learning-preparedness-jordan (accessed November 27, 2020).

Google Scholar

Ayebi-Arthur, K. (2017). E-learning, resilience and change in higher education: Helping a university cope after a natural disaster. E Learn. Digit. Med. 14, 259–274. doi: 10.1177/2042753017751712

Beck, C. W., and Blumer, L. S. (2016). Alternative realities: Faculty and student perceptions of instructional practices in laboratory courses. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 15:ar52. doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-03-0139

Beteille, T., Ding, E., Molina, E., Pushparatnam, A., and Wilichowski, T. (2020). Three Principles to Support Teacher Effectiveness During COVID-19. Three Principles to Support Teacher Effectiveness During COVID-19. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Cheng, G., and Chau, J. (2016). Exploring the relationships between learning styles, online participation, learning achievement and course satisfaction: An empirical study of a blended learning course. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 47, 257–278. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12243

Cooke, G. (2020). Online Learning vs Face to Face Learning | Elucidat. Available online at: https://www.elucidat.com/blog/online-learning-vs-face-to-face-learning/ (accessed January 17, 2021).

De La Varre, C., Keane, J., and Irvin, M. J. (2010). Enhancing online distance education in small rural US schools: A hybrid, learner-centred model. ALT J. Res. Learn. Technol. 18, 193–205. doi: 10.1080/09687769.2010.529109

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: a panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 49, 5–22. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018

Dirani, and Yoon (2009). View of Exploring Open Distance Learning at a Jordanian University: A Case Study | The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. Available online at: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/599/1215 (accessed January 9, 2021).

EasyLMS (2021). Difference Synchronous vs Asynchronous Learning | Easy LMS. Available online at: https://www.easy-lms.com/knowledge-center/lms-knowledge-center/synchronous-vs-asynchronous-learning/item10387 (accessed January 9, 2021).

Ehlers, U.-D., and Pawlowski, J. M. (2006). “Quality in European e-learning: an introduction,” in Handbook on Quality and Standardisation in E-Learning , eds U. D. Ehlers and J. M. Pawlowski (Berlin: Springer), 1–13. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32788-6_1

Englund, C., Olofsson, A. D., and Price, L. (2017). Teaching with technology in higher education: understanding conceptual change and development in practice. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 36, 73–87. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1171300

Gautam, P. (2020). Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Learning - eLearning Industry. Available online at: https://elearningindustry.com/advantages-and-disadvantages-online-learning (accessed December 1, 2020).

Gratton-Lavoie, C., and Stanley, D. (2009). Teaching and learning principles of microeconomics online: An empirical assessment. J. Econ. Educ. 40, 3–25. doi: 10.3200/JECE.40.1.003-025

Gurukkal, R. (2020). Will COVID 19 turn higher education into another mode? High. Educ. Future 7, 89–96. doi: 10.1177/2347631120931606

Haider, A. S., and Al-Salman, S. (2020). Dataset of Jordanian university students’ psychological health impacted by using E-learning tools during COVID-19. Data in Brief 32:106104. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106104

Hancock, R. (2002). Classroom Assistants in Primary Schools: Employment and Deployment. Available online at: https://www.academia.edu/26061509/Classroom_assistants_in_primary_schools_Employment_and_deployment (accessed November, 2020).

Isaeva, R., Eisenschmidt, E., Vanari, K., and Kumpas-Lenk, K. (2020). Students’ views on dialogue: improving student engagement in the quality assurance process. Qual. High. Educ. 26, 80–97. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2020.1729307

Jeffcoat Bartley, S., and Golek, J. H. (2004). Evaluating the cost effectiveness of online and face-to-face instruction. Educ. Technol. Soc. 7, 167–175.

Jordan Times (2017). ‘Jordan Leading in Internet Infrastructure in Region’ | Jordan Times. Available online at: http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/jordan-leading-internet-infrastructure-region ’ (accessed January 9, 2021).

Kinney, L., Liu, M., and Thornton, M. A. (2012). “Faculty and student perceptions of online learning in engineering education,” in Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference , (Washington, DC: American Society for Engineering Education).

Kulal, A., and Nayak, A. (2020). A study on perception of teachers and students toward online classes in Dakshina Kannada and Udupi District. Asian Assoc. Open Univ. J. 15, 285–296. doi: 10.1108/aaouj-07-2020-0047

Li, C., and Lalani, F. (2020). The Rise of Online Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic | World Economic Forum. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/ (accessed December 1, 2020).

Li, L.-Y., and Lee, L.-Y. (2016). Computer literacy and online learning attitude toward GSOE students in distance education programs. High. Educ. Stud. 6:147. doi: 10.5539/hes.v6n3p147

Luxatia (2020). The Importance Of Digital Learning Spaces During COVID-19 and Beyond | Luxatia International. Available online at: https://www.luxatiainternational.com/article/the-importance-of-digital-learning-spaces-during-covid-19-and-beyond (accessed December 9, 2020).

Martín-Blas, T., and Serrano-Fernández, A. (2009). The role of new technologies in the learning process: moodle as a teaching tool in physics. Comput. Educ. 52, 35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2008.06.005

Mockovak, W. (2016). “Assessing the reliability of conversational interviewing,” in Proceedings of the Joint Statistical Meetings , Washington, DC.

Nemetz, P. L., Eager, W. M., and Limpaphayom, W. (2017). Comparative effectiveness and student choice for online and face-to-face classwork. J. Educ. Bus. 92, 210–219. doi: 10.1080/08832323.2017.1331990

Nikdel Teymori, A., and Fardin, M. A. (2020). COVID-19 and educational challenges: a review of the benefits of online education. Ann. Milit. Health Sci. Res. 18:e105778. doi: 10.5812/amh.105778

Rayan, P. (2020). E-learning: The advantages and Challenges. Available online at: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/351860 (accessed December 1, 2020).

Roach, V., and Lemasters, L. (2006). Satisfaction with online learning: a comparative descriptive Study. J. Interact. Online Learn. 5, 317–332.

Rosell, C. (2020). COVID-19 Virus: Changes in Education | CAE. Available online at: https://www.cae.net/covid-19-virus-changes-in-education/ (accessed January 9, 2021).

Santos, J., Figueiredo, A. S., and Vieira, M. (2019). Innovative pedagogical practices in higher education: An integrative literature review. Nurse Educ. Today Churchill Livingstone 72, 12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.10.003

Seok, S., DaCosta, B., Kinsell, C., and Tung, C. K. (2010). Comparison of instructors’ and students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of online courses. Q. Rev. Distance Educ. 11, 25–36.

Shahzad, A., Hassan, R., Aremu, A. Y., Hussain, A., and Lodhi, R. N. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 in E-learning on higher education institution students: the group comparison between male and female. Qual. Quant. doi: 10.1007/s11135-020-01028-z [Epub ahead of print].

CrossRef Full Text | PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Silva, M., and Cartwright, G. F. (2017). The internet as a medium for education and educational research. Educ. Libr. 17:7. doi: 10.26443/el.v17i2.44

Siripongdee, K., Pimdee, P., and Tuntiwongwanich, S. (2020). A blended learning model with IoT-based technology: Effectively used when the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Educ. Gift. Young Sci. 8, 905–917. doi: 10.17478/JEGYS.698869

Spataro, J. (2020). Microsoft Teams Reaches 115 Million DAU—Plus, a New Daily Collaboration Minutes Metric for Microsoft 365 - Microsoft 365 Blog. Available online at: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/blog/2020/10/28/microsoft-teams-reaches-115-million-dau-plus-a-new-daily-collaboration-minutes-metric-for-microsoft-365/ (accessed January 15, 2021).

Statista (2020). Most Popular Social Media Platforms [Updated April 2020]. Available online at: https://www.oberlo.com/statistics/most-popular-social-media-platforms (accessed November 14, 2020).

Stec, M., Smith, C., and Jacox, E. (2020). Technology enhanced teaching and learning: exploration of faculty adaptation to iPad delivered curriculum. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 25, 651–665. doi: 10.1007/s10758-019-09401-0