How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

How to write a speech that your audience remembers

Whether in a work meeting or at an investor panel, you might give a speech at some point. And no matter how excited you are about the opportunity, the experience can be nerve-wracking .

But feeling butterflies doesn’t mean you can’t give a great speech. With the proper preparation and a clear outline, apprehensive public speakers and natural wordsmiths alike can write and present a compelling message. Here’s how to write a good speech you’ll be proud to deliver.

What is good speech writing?

Good speech writing is the art of crafting words and ideas into a compelling, coherent, and memorable message that resonates with the audience. Here are some key elements of great speech writing:

- It begins with clearly understanding the speech's purpose and the audience it seeks to engage.

- A well-written speech clearly conveys its central message, ensuring that the audience understands and retains the key points.

- It is structured thoughtfully, with a captivating opening, a well-organized body, and a conclusion that reinforces the main message.

- Good speech writing embraces the power of engaging content, weaving in stories, examples, and relatable anecdotes to connect with the audience on both intellectual and emotional levels.

Ultimately, it is the combination of these elements, along with the authenticity and delivery of the speaker , that transforms words on a page into a powerful and impactful spoken narrative.

What makes a good speech?

A great speech includes several key qualities, but three fundamental elements make a speech truly effective:

Clarity and purpose

Remembering the audience, cohesive structure.

While other important factors make a speech a home run, these three elements are essential for writing an effective speech.

The main elements of a good speech

The main elements of a speech typically include:

- Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your speech and grabs the audience's attention. It should include a hook or attention-grabbing opening, introduce the topic, and provide an overview of what will be covered.

- Opening/captivating statement: This is a strong statement that immediately engages the audience and creates curiosity about the speech topics.

- Thesis statement/central idea: The thesis statement or central idea is a concise statement that summarizes the main point or argument of your speech. It serves as a roadmap for the audience to understand what your speech is about.

- Body: The body of the speech is where you elaborate on your main points or arguments. Each point is typically supported by evidence, examples, statistics, or anecdotes. The body should be organized logically and coherently, with smooth transitions between the main points.

- Supporting evidence: This includes facts, data, research findings, expert opinions, or personal stories that support and strengthen your main points. Well-chosen and credible evidence enhances the persuasive power of your speech.

- Transitions: Transitions are phrases or statements that connect different parts of your speech, guiding the audience from one idea to the next. Effective transitions signal the shifts in topics or ideas and help maintain a smooth flow throughout the speech.

- Counterarguments and rebuttals (if applicable): If your speech involves addressing opposing viewpoints or counterarguments, you should acknowledge and address them. Presenting counterarguments makes your speech more persuasive and demonstrates critical thinking.

- Conclusion: The conclusion is the final part of your speech and should bring your message to a satisfying close. Summarize your main points, restate your thesis statement, and leave the audience with a memorable closing thought or call to action.

- Closing statement: This is the final statement that leaves a lasting impression and reinforces the main message of your speech. It can be a call to action, a thought-provoking question, a powerful quote, or a memorable anecdote.

- Delivery and presentation: How you deliver your speech is also an essential element to consider. Pay attention to your tone, body language, eye contact , voice modulation, and timing. Practice and rehearse your speech, and try using the 7-38-55 rule to ensure confident and effective delivery.

While the order and emphasis of these elements may vary depending on the type of speech and audience, these elements provide a framework for organizing and delivering a successful speech.

How to structure a good speech

You know what message you want to transmit, who you’re delivering it to, and even how you want to say it. But you need to know how to start, develop, and close a speech before writing it.

Think of a speech like an essay. It should have an introduction, conclusion, and body sections in between. This places ideas in a logical order that the audience can better understand and follow them. Learning how to make a speech with an outline gives your storytelling the scaffolding it needs to get its point across.

Here’s a general speech structure to guide your writing process:

- Explanation 1

- Explanation 2

- Explanation 3

How to write a compelling speech opener

Some research shows that engaged audiences pay attention for only 15 to 20 minutes at a time. Other estimates are even lower, citing that people stop listening intently in fewer than 10 minutes . If you make a good first impression at the beginning of your speech, you have a better chance of interesting your audience through the middle when attention spans fade.

Implementing the INTRO model can help grab and keep your audience’s attention as soon as you start speaking. This acronym stands for interest, need, timing, roadmap, and objectives, and it represents the key points you should hit in an opening.

Here’s what to include for each of these points:

- Interest : Introduce yourself or your topic concisely and speak with confidence . Write a compelling opening statement using relevant data or an anecdote that the audience can relate to.

- Needs : The audience is listening to you because they have something to learn. If you’re pitching a new app idea to a panel of investors, those potential partners want to discover more about your product and what they can earn from it. Read the room and gently remind them of the purpose of your speech.

- Timing : When appropriate, let your audience know how long you’ll speak. This lets listeners set expectations and keep tabs on their own attention span. If a weary audience member knows you’ll talk for 40 minutes, they can better manage their energy as that time goes on.

- Routemap : Give a brief overview of the three main points you’ll cover in your speech. If an audience member’s attention starts to drop off and they miss a few sentences, they can more easily get their bearings if they know the general outline of the presentation.

- Objectives : Tell the audience what you hope to achieve, encouraging them to listen to the end for the payout.

Writing the middle of a speech

The body of your speech is the most information-dense section. Facts, visual aids, PowerPoints — all this information meets an audience with a waning attention span. Sticking to the speech structure gives your message focus and keeps you from going off track, making everything you say as useful as possible.

Limit the middle of your speech to three points, and support them with no more than three explanations. Following this model organizes your thoughts and prevents you from offering more information than the audience can retain.

Using this section of the speech to make your presentation interactive can add interest and engage your audience. Try including a video or demonstration to break the monotony. A quick poll or survey also keeps the audience on their toes.

Wrapping the speech up

To you, restating your points at the end can feel repetitive and dull. You’ve practiced countless times and heard it all before. But repetition aids memory and learning , helping your audience retain what you’ve told them. Use your speech’s conclusion to summarize the main points with a few short sentences.

Try to end on a memorable note, like posing a motivational quote or a thoughtful question the audience can contemplate once they leave. In proposal or pitch-style speeches, consider landing on a call to action (CTA) that invites your audience to take the next step.

How to write a good speech

If public speaking gives you the jitters, you’re not alone. Roughly 80% of the population feels nervous before giving a speech, and another 10% percent experiences intense anxiety and sometimes even panic.

The fear of failure can cause procrastination and can cause you to put off your speechwriting process until the last minute. Finding the right words takes time and preparation, and if you’re already feeling nervous, starting from a blank page might seem even harder.

But putting in the effort despite your stress is worth it. Presenting a speech you worked hard on fosters authenticity and connects you to the subject matter, which can help your audience understand your points better. Human connection is all about honesty and vulnerability, and if you want to connect to the people you’re speaking to, they should see that in you.

1. Identify your objectives and target audience

Before diving into the writing process, find healthy coping strategies to help you stop worrying . Then you can define your speech’s purpose, think about your target audience, and start identifying your objectives. Here are some questions to ask yourself and ground your thinking :

- What purpose do I want my speech to achieve?

- What would it mean to me if I achieved the speech’s purpose?

- What audience am I writing for?

- What do I know about my audience?

- What values do I want to transmit?

- If the audience remembers one take-home message, what should it be?

- What do I want my audience to feel, think, or do after I finish speaking?

- What parts of my message could be confusing and require further explanation?

2. Know your audience

Understanding your audience is crucial for tailoring your speech effectively. Consider the demographics of your audience, their interests, and their expectations. For instance, if you're addressing a group of healthcare professionals, you'll want to use medical terminology and data that resonate with them. Conversely, if your audience is a group of young students, you'd adjust your content to be more relatable to their experiences and interests.

3. Choose a clear message

Your message should be the central idea that you want your audience to take away from your speech. Let's say you're giving a speech on climate change. Your clear message might be something like, "Individual actions can make a significant impact on mitigating climate change." Throughout your speech, all your points and examples should support this central message, reinforcing it for your audience.

4. Structure your speech

Organizing your speech properly keeps your audience engaged and helps them follow your ideas. The introduction should grab your audience's attention and introduce the topic. For example, if you're discussing space exploration, you could start with a fascinating fact about a recent space mission. In the body, you'd present your main points logically, such as the history of space exploration, its scientific significance, and future prospects. Finally, in the conclusion, you'd summarize your key points and reiterate the importance of space exploration in advancing human knowledge.

5. Use engaging content for clarity

Engaging content includes stories, anecdotes, statistics, and examples that illustrate your main points. For instance, if you're giving a speech about the importance of reading, you might share a personal story about how a particular book changed your perspective. You could also include statistics on the benefits of reading, such as improved cognitive abilities and empathy.

6. Maintain clarity and simplicity

It's essential to communicate your ideas clearly. Avoid using overly technical jargon or complex language that might confuse your audience. For example, if you're discussing a medical breakthrough with a non-medical audience, explain complex terms in simple, understandable language.

7. Practice and rehearse

Practice is key to delivering a great speech. Rehearse multiple times to refine your delivery, timing, and tone. Consider using a mirror or recording yourself to observe your body language and gestures. For instance, if you're giving a motivational speech, practice your gestures and expressions to convey enthusiasm and confidence.

8. Consider nonverbal communication

Your body language, tone of voice, and gestures should align with your message . If you're delivering a speech on leadership, maintain strong eye contact to convey authority and connection with your audience. A steady pace and varied tone can also enhance your speech's impact.

9. Engage your audience

Engaging your audience keeps them interested and attentive. Encourage interaction by asking thought-provoking questions or sharing relatable anecdotes. If you're giving a speech on teamwork, ask the audience to recall a time when teamwork led to a successful outcome, fostering engagement and connection.

10. Prepare for Q&A

Anticipate potential questions or objections your audience might have and prepare concise, well-informed responses. If you're delivering a speech on a controversial topic, such as healthcare reform, be ready to address common concerns, like the impact on healthcare costs or access to services, during the Q&A session.

By following these steps and incorporating examples that align with your specific speech topic and purpose, you can craft and deliver a compelling and impactful speech that resonates with your audience.

Tools for writing a great speech

There are several helpful tools available for speechwriting, both technological and communication-related. Here are a few examples:

- Word processing software: Tools like Microsoft Word, Google Docs, or other word processors provide a user-friendly environment for writing and editing speeches. They offer features like spell-checking, grammar correction, formatting options, and easy revision tracking.

- Presentation software: Software such as Microsoft PowerPoint or Google Slides is useful when creating visual aids to accompany your speech. These tools allow you to create engaging slideshows with text, images, charts, and videos to enhance your presentation.

- Speechwriting Templates: Online platforms or software offer pre-designed templates specifically for speechwriting. These templates provide guidance on structuring your speech and may include prompts for different sections like introductions, main points, and conclusions.

- Rhetorical devices and figures of speech: Rhetorical tools such as metaphors, similes, alliteration, and parallelism can add impact and persuasion to your speech. Resources like books, websites, or academic papers detailing various rhetorical devices can help you incorporate them effectively.

- Speechwriting apps: Mobile apps designed specifically for speechwriting can be helpful in organizing your thoughts, creating outlines, and composing a speech. These apps often provide features like voice recording, note-taking, and virtual prompts to keep you on track.

- Grammar and style checkers: Online tools or plugins like Grammarly or Hemingway Editor help improve the clarity and readability of your speech by checking for grammar, spelling, and style errors. They provide suggestions for sentence structure, word choice, and overall tone.

- Thesaurus and dictionary: Online or offline resources such as thesauruses and dictionaries help expand your vocabulary and find alternative words or phrases to express your ideas more effectively. They can also clarify meanings or provide context for unfamiliar terms.

- Online speechwriting communities: Joining online forums or communities focused on speechwriting can be beneficial for getting feedback, sharing ideas, and learning from experienced speechwriters. It's an opportunity to connect with like-minded individuals and improve your public speaking skills through collaboration.

Remember, while these tools can assist in the speechwriting process, it's essential to use them thoughtfully and adapt them to your specific needs and style. The most important aspect of speechwriting remains the creativity, authenticity, and connection with your audience that you bring to your speech.

5 tips for writing a speech

Behind every great speech is an excellent idea and a speaker who refined it. But a successful speech is about more than the initial words on the page, and there are a few more things you can do to help it land.

Here are five more tips for writing and practicing your speech:

1. Structure first, write second

If you start the writing process before organizing your thoughts, you may have to re-order, cut, and scrap the sentences you worked hard on. Save yourself some time by using a speech structure, like the one above, to order your talking points first. This can also help you identify unclear points or moments that disrupt your flow.

2. Do your homework

Data strengthens your argument with a scientific edge. Research your topic with an eye for attention-grabbing statistics, or look for findings you can use to support each point. If you’re pitching a product or service, pull information from company metrics that demonstrate past or potential successes.

Audience members will likely have questions, so learn all talking points inside and out. If you tell investors that your product will provide 12% returns, for example, come prepared with projections that support that statement.

3. Sound like yourself

Memorable speakers have distinct voices. Think of Martin Luther King Jr’s urgent, inspiring timbre or Oprah’s empathetic, personal tone . Establish your voice — one that aligns with your personality and values — and stick with it. If you’re a motivational speaker, keep your tone upbeat to inspire your audience . If you’re the CEO of a startup, try sounding assured but approachable.

4. Practice

As you practice a speech, you become more confident , gain a better handle on the material, and learn the outline so well that unexpected questions are less likely to trip you up. Practice in front of a colleague or friend for honest feedback about what you could change, and speak in front of the mirror to tweak your nonverbal communication and body language .

5. Remember to breathe

When you’re stressed, you breathe more rapidly . It can be challenging to talk normally when you can’t regulate your breath. Before your presentation, try some mindful breathing exercises so that when the day comes, you already have strategies that will calm you down and remain present . This can also help you control your voice and avoid speaking too quickly.

How to ghostwrite a great speech for someone else

Ghostwriting a speech requires a unique set of skills, as you're essentially writing a piece that will be delivered by someone else. Here are some tips on how to effectively ghostwrite a speech:

- Understand the speaker's voice and style : Begin by thoroughly understanding the speaker's personality, speaking style, and preferences. This includes their tone, humor, and any personal anecdotes they may want to include.

- Interview the speaker : Have a detailed conversation with the speaker to gather information about their speech's purpose, target audience, key messages, and any specific points they want to emphasize. Ask for personal stories or examples they may want to include.

- Research thoroughly : Research the topic to ensure you have a strong foundation of knowledge. This helps you craft a well-informed and credible speech.

- Create an outline : Develop a clear outline that includes the introduction, main points, supporting evidence, and a conclusion. Share this outline with the speaker for their input and approval.

- Write in the speaker's voice : While crafting the speech, maintain the speaker's voice and style. Use language and phrasing that feel natural to them. If they have a particular way of expressing ideas, incorporate that into the speech.

- Craft a captivating opening : Begin the speech with a compelling opening that grabs the audience's attention. This could be a relevant quote, an interesting fact, a personal anecdote, or a thought-provoking question.

- Organize content logically : Ensure the speech flows logically, with each point building on the previous one. Use transitions to guide the audience from one idea to the next smoothly.

- Incorporate engaging stories and examples : Include anecdotes, stories, and real-life examples that illustrate key points and make the speech relatable and memorable.

- Edit and revise : Edit the speech carefully for clarity, grammar, and coherence. Ensure the speech is the right length and aligns with the speaker's time constraints.

- Seek feedback : Share drafts of the speech with the speaker for their feedback and revisions. They may have specific changes or additions they'd like to make.

- Practice delivery : If possible, work with the speaker on their delivery. Practice the speech together, allowing the speaker to become familiar with the content and your writing style.

- Maintain confidentiality : As a ghostwriter, it's essential to respect the confidentiality and anonymity of the work. Do not disclose that you wrote the speech unless you have the speaker's permission to do so.

- Be flexible : Be open to making changes and revisions as per the speaker's preferences. Your goal is to make them look good and effectively convey their message.

- Meet deadlines : Stick to agreed-upon deadlines for drafts and revisions. Punctuality and reliability are essential in ghostwriting.

- Provide support : Support the speaker during their preparation and rehearsal process. This can include helping with cue cards, speech notes, or any other materials they need.

Remember that successful ghostwriting is about capturing the essence of the speaker while delivering a well-structured and engaging speech. Collaboration, communication, and adaptability are key to achieving this.

Give your best speech yet

Learn how to make a speech that’ll hold an audience’s attention by structuring your thoughts and practicing frequently. Put the effort into writing and preparing your content, and aim to improve your breathing, eye contact , and body language as you practice. The more you work on your speech, the more confident you’ll become.

The energy you invest in writing an effective speech will help your audience remember and connect to every concept. Remember: some life-changing philosophies have come from good speeches, so give your words a chance to resonate with others. You might even change their thinking.

Boost your speech skills

Enhance your public speaking with personalized coaching tailored to your needs

Elizabeth Perry, ACC

Elizabeth Perry is a Coach Community Manager at BetterUp. She uses strategic engagement strategies to cultivate a learning community across a global network of Coaches through in-person and virtual experiences, technology-enabled platforms, and strategic coaching industry partnerships. With over 3 years of coaching experience and a certification in transformative leadership and life coaching from Sofia University, Elizabeth leverages transpersonal psychology expertise to help coaches and clients gain awareness of their behavioral and thought patterns, discover their purpose and passions, and elevate their potential. She is a lifelong student of psychology, personal growth, and human potential as well as an ICF-certified ACC transpersonal life and leadership Coach.

10+ interpersonal skills at work and ways to develop them

How to write an impactful cover letter for a career change, 6 presentation skills and how to improve them, 18 effective strategies to improve your communication skills, what are analytical skills examples and how to level up, what is gig work and does it make the dream work, the 11 tips that will improve your public speaking skills, self-management skills for a messy world, how to be more persuasive: 6 tips for convincing others, similar articles, how to write an executive summary in 10 steps, how to pitch ideas: 8 tips to captivate any audience, how to give a good presentation that captivates any audience, anxious about meetings learn how to run a meeting with these 10 tips, writing an elevator pitch about yourself: a how-to plus tips, 9 elevator pitch examples for making a strong first impression, how to write a memo: 8 steps with examples, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead™

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care®

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

paper-free learning

- conjunctions

- determiners

- interjections

- prepositions

- affect vs effect

- its vs it's

- your vs you're

- which vs that

- who vs whom

- who's vs whose

- averse vs adverse

- 250+ more...

- apostrophes

- quotation marks

- lots more...

- common writing errors

- FAQs by writers

- awkward plurals

- ESL vocabulary lists

- all our grammar videos

- idioms and proverbs

- Latin terms

- collective nouns for animals

- tattoo fails

- vocabulary categories

- most common verbs

- top 10 irregular verbs

- top 10 regular verbs

- top 10 spelling rules

- improve spelling

- common misspellings

- role-play scenarios

- favo(u)rite word lists

- multiple-choice test

- Tetris game

- grammar-themed memory game

- 100s more...

Parts of Speech

What are the parts of speech, a formal definition.

Table of Contents

The Part of Speech Is Determined by the Word's Function

Are there 8 or 9 parts of speech, the nine parts of speech, (1) adjective, (3) conjunction, (4) determiner, (5) interjection, (7) preposition, (8) pronoun, why the parts of speech are important, video lesson.

- You need to dig a well . (noun)

- You look well . (adjective)

- You dance well . (adverb)

- Well , I agree. (interjection)

- My eyes will well up. (verb)

- red, happy, enormous

- Ask the boy in the red jumper.

- I live in a happy place.

- I caught a fish this morning! I mean an enormous one.

- happily, loosely, often

- They skipped happily to the counter.

- Tie the knot loosely so they can escape.

- I often walk to work.

- It is an intriguingly magic setting.

- He plays the piano extremely well.

- and, or, but

- it is a large and important city.

- Shall we run to the hills or hide in the bushes?

- I know you are lying, but I cannot prove it.

- my, those, two, many

- My dog is fine with those cats.

- There are two dogs but many cats.

- ouch, oops, eek

- Ouch , that hurt.

- Oops , it's broken.

- Eek! A mouse just ran past my foot!

- leader, town, apple

- Take me to your leader .

- I will see you in town later.

- An apple fell on his head .

- in, near, on, with

- Sarah is hiding in the box.

- I live near the train station.

- Put your hands on your head.

- She yelled with enthusiasm.

- she, we, they, that

- Joanne is smart. She is also funny.

- Our team has studied the evidence. We know the truth.

- Jack and Jill went up the hill, but they never returned.

- That is clever!

- work, be, write, exist

- Tony works down the pit now. He was unemployed.

- I will write a song for you.

- I think aliens exist .

Are you a visual learner? Do you prefer video to text? Here is a list of all our grammar videos .

Video for Each Part of Speech

The Most Important Writing Issues

The top issue related to adjectives, the top issue related to adverbs.

- Extremely annoyed, she stared menacingly at her rival.

- Infuriated, she glared at her rival.

The Top Issue Related to Conjunctions

- Burger, Fries, and a shake

- Fish, chips and peas

The Top Issue Related to Determiners

The Top Issue Related to Interjections

The top issue related to nouns, the top issue related to prepositions, the top issue related to pronouns, the top issue related to verbs.

- Crack the parts of speech to help with learning a foreign language or to take your writing to the next level.

This page was written by Craig Shrives .

Learning Resources

more actions:

This test is printable and sendable

Help Us Improve Grammar Monster

- Do you disagree with something on this page?

- Did you spot a typo?

Find Us Quicker!

- When using a search engine (e.g., Google, Bing), you will find Grammar Monster quicker if you add #gm to your search term.

You might also like...

Share This Page

If you like Grammar Monster (or this page in particular), please link to it or share it with others. If you do, please tell us . It helps us a lot!

Create a QR Code

Use our handy widget to create a QR code for this page...or any page.

< previous lesson

next lesson >

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

English lessons and resources

Direct speech writing rules in English

7th January 2019 by Andrew 14 Comments

In the above picture, Mark is talking to Jane. The words inside the blue box are the exact words that he speaks.

Here is how we express this:

This is direct speech. Direct speech is when we report the exact words that somebody says.

In this English lesson, you will learn:

- The rules for writing direct speech.

- The correct punctuation.

- Vocabulary to report direct speech.

Reporting clause before the direct speech

The reporting clause of direct speech is the short clause that indicates who is talking. It is the clause that is outside of the inverted commas. It is therefore not the words being spoken.

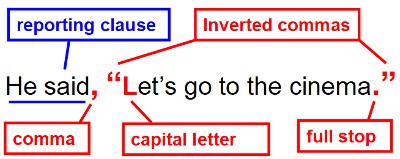

We can write the reporting clause either before or after the direct speech. If the reporting clause is before the direct speech, we write it as follows:

Grammar rules – If the reporting clause is before the direct speech:

We write a comma (,) before the direct speech. We write the exact words inside the inverted commas. The first letter is a capital letter. We write a full stop (.) before the closing inverted commas.

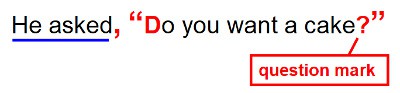

Reporting clause before a question or exclamation

If the reporting clause is before a question or exclamation:

We write a comma (,) before the direct speech. We write the exact words inside the inverted commas. The first letter is a capital letter. We write a question mark (?) before the closing inverted commas. or We write an exclamation mark (!) before the closing inverted commas.

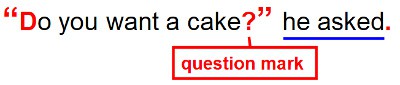

Reporting clause after the direct speech

If the reporting clause is after the direct speech:

We write the exact words inside the inverted commas. The first letter is a capital letter. We write a comma (,) before the closing inverted commas. We write a full stop (.) at the end of the reporting clause.

Reporting clause after a question or exclamation

If the reporting clause is after a question or exclamation:

We write the exact words inside the inverted commas. The first letter is a capital letter. We write a question mark (?) before the closing inverted commas. or We write an exclamation mark (!) before the closing inverted commas. We write a full stop (.) at the end of the reporting clause.

Advanced rules for direct speech

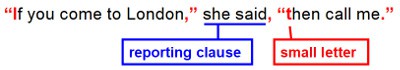

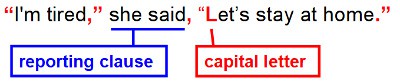

Sometimes we break up the direct speech into 2 parts:

The second part of the direct speech starts with a small letter if it is the same sentence as the first part of the direct speech.

The second part of the direct speech starts with a capital letter if it is a new sentence.

Vocabulary of direct speech

We have several names for the above punctuation marks:

Inverted commas Speech marks Quotation marks Quotes

Other reporting verbs

Here are some other useful reporting verbs:

reply (replied) ask (asked) shout (shouted) agree (agreed) comment (commented) admit (admitted)

They are often used for writing direct speech in books, newspapers and reports. It is more common to use them in reporting clauses after the direct speech.

“I really don’t like her dress,” she commented . “I don’t love you anymore,” he admitted .

Other English lessons

Private online English lessons How to pass the IELTS with a band 8 Adverbs of frequency Indefinite article “a” and “an” The prepositions FOR and SINCE All of our lessons

Direct speech video lesson

Reader Interactions

Matěj Formánek says

3rd November 2019 at 5:54 pm

How about this sentence: I know the satnav is wrong!” exclaimed Zena. – Why the subject and predicate are swapped? It’s sentence from textbook so I’m confused.

17th June 2020 at 4:07 pm

Can we write multiple sentences in direct speech that comes before reporting clause? In case if this is allowed, what punctuation mark should be used after the last sentence?

Example: “I entered the class room. As I did not find anybody there, I left the class room and went to buy a coffee.” explained the student to the teacher for his delay to come to the class.

Should the punctuation mark after the word coffee be comma instead of full stop?

Joaquim Barretto says

14th September 2020 at 1:25 pm

No full stop, but comma after the word coffee.

19th January 2021 at 2:34 pm

HI IM DAISY

courtney says

27th January 2021 at 12:07 pm

Clare Hatcher says

12th March 2021 at 9:55 am

Hello I like the layout of this – very clear. Just wondering if it is correct to use a comma in between two separate sentences in direct speech. I think that now in published material you find this instead. ‘I’m tired,’ she said. ‘Let’s stay at home.’ Would appreciate your thoughts Thanks

27th March 2021 at 8:54 am

If I wrote something with a comma at the end to continue speech like this:

“Hello,” he waved to the new student, “what’s you’re name?”

Do I have to use a capital letter even if I’m continuing with a comma or is it lowercase?

Sylvia Edouard says

30th September 2023 at 9:17 am

Yes, you need to use a capital letter as speech from someone has to start with a capital letter. Always.

15th April 2022 at 12:12 pm

which of the following is correct?

1. Should the status go missing when the metadata states, “Sign & return document?”

2. Should the status go missing when the metadata states, “Sign & return document,”? (comma inside)

3. Should the status go missing when the metadata states, “Sign & return document.”? (full stop inside)

Jan Švanda says

7th September 2023 at 1:31 pm

I presume the quotation is there to specify the exact phrase (for the metadata entry). I also encounter this from time to time, when writing technical documentation. I believe in that case you should write the phrase as it is, proper grammar be damned; beautifully looking documentation is useless if it leads to incorrect results.

In this case, I don’t even think this is “direct speech”, the metadata entry isn’t walking around and saying things, the quotation mark is there to indicate precise phrase – similar to marking strings in programming languages. Because of this, I don’t think direct speech rules apply, or at least, they should take back seat. If the expected status includes full stop at the end, the sentence would be:

4. Should the status go missing when the metadata states “Sign & return document.”? (no comma before, since it is not a direct speech; full stop inside, as it is part of the quoted status)

From grammatical perspective the end looks a bit ugly, but again, if this should be technical documentation, that is less important than precision.

A person says

15th August 2022 at 7:16 pm

One extra thing: YOU MUST NOT USE THE WORD SAID IN A REPORTING CLAUSE. EVER. IT’S UNIMAGINATIVE.

no joke, it’s actually discouraged and even close to banned at my school

7th September 2023 at 1:49 pm

This is stupid. You shouldn’t use it in _every_ sentence, there should be variety, but outright banning it doesn’t make sense.

Case in point:

Book: ‘Pride and Prejudice’. Phrase to search: ‘,” said’ (comma, followed by quotation mark, followed by space, followed by word ‘said’). Number of occurrences: 211. Total number of ‘,”‘ (comma, followed by quotation mark) strings is 436, so “said” is used in almost 50% cases of direct speech of this type.

I don’t think it would be right for your school to ban Jane Austin, do you?

blaire says

30th March 2024 at 5:36 pm

How do you use names in direct speech?

Is it: “I really don’t like her dress,” Ashley said. or “I really don’t like her dress,” said Ashley.

I’ve seen both and I’m so confused which one is correct, please help me.

Andrew says

3rd April 2024 at 11:31 am

Hello and thanks for your comment and question.

After the direct speech, both are correct.

Before the direct speech, only the first one is correct:

Ashley said, “I really don’t like her dress.” (correct) Said Ashley, “I really don’t like her dress.” (wrong)

I hope that helps you. Andrew https://www.youtube.com/@CrownAcademyEnglish/

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Follow us on social media

Privacy policy

- 8 ways to say that something is FREE in English

- English idioms and expressions related to CRIME

- How to use either and neither – English lesson

- Learn English vocabulary – Vegetables

- English Idioms related to speed

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Grammar: Sentence Structure and Types of Sentences

Definitions and examples of basic sentence elements.

The Mastering the Mechanics webinar series also describes required sentence elements and varying sentence types. Please see these archived webinars for more information.

Key: Yellow, bold = subject; green underline = verb, blue, italics = object, pink, regular font = prepositional phrase

Independent clause : An independent clause can stand alone as a sentence. It contains a subject and a verb and is a complete idea.

- I like spaghetti .

- He reads many books .

Dependent clause : A dependent clause is not a complete sentence. It must be attached to an independent clause to become complete. This is also known as a subordinate clause.

- Although I like spaghetti,…

- Because he reads many books,…

Subject : A person, animal, place, thing, or concept that does an action. Determine the subject in a sentence by asking the question “Who or what?”

- I like spaghetti.

- He reads many books.

Verb : Expresses what the person, animal, place, thing, or concept does. Determine the verb in a sentence by asking the question “What was the action or what happened?”

- The movie is good. (The be verb is also sometimes referred to as a copula or a linking verb. It links the subject, in this case "the movie," to the complement or the predicate of the sentence, in this case, "good.")

Object : A person, animal, place, thing, or concept that receives the action. Determine the object in a sentence by asking the question “The subject did what?” or “To whom?/For whom?”

Prepositional Phrase : A phrase that begins with a preposition (i.e., in, at for, behind, until, after, of, during) and modifies a word in the sentence. A prepositional phrase answers one of many questions. Here are a few examples: “Where? When? In what way?”

- I like spaghetti for dinner .

- He reads many books in the library .

English Sentence Structure

The following statements are true about sentences in English:

- H e obtained his degree.

- He obtained his degree .

- Smith he obtained his degree.

- He obtained his degree.

- He (subject) obtained (verb) his degree (object).

Simple Sentences

A simple sentence contains a subject and a verb, and it may also have an object and modifiers. However, it contains only one independent clause.

Key: Yellow, bold = subject; green underline = verb, blue, italics = object, pink, regular font =prepositional phrase

Here are a few examples:

- She wrote .

- She completed her literature review .

- He organized his sources by theme .

- They studied APA rules for many hours .

Compound Sentences

A compound sentence contains at least two independent clauses. These two independent clauses can be combined with a comma and a coordinating conjunction or with a semicolon .

Key: independent clause = yellow, bold ; comma or semicolon = pink, regular font ; coordinating conjunction = green, underlined

- She completed her literature review , and she created her reference list .

- He organized his sources by theme ; then, he updated his reference list .

- They studied APA rules for many hours , but they realized there was still much to learn .

Using some compound sentences in writing allows for more sentence variety .

Complex Sentences

A complex sentence contains at least one independent clause and at least one dependent clause. Dependent clauses can refer to the subject (who, which) the sequence/time (since, while), or the causal elements (because, if) of the independent clause.

If a sentence begins with a dependent clause, note the comma after this clause. If, on the other hand, the sentence begins with an independent clause, there is not a comma separating the two clauses.

Key: independent clause = yellow, bold ; comma = pink, regular font ; dependent clause = blue, italics

- Note the comma in this sentence because it begins with a dependent clause.

- Note that there is no comma in this sentence because it begins with an independent clause.

- Using some complex sentences in writing allows for more sentence variety .

Compound-Complex Sentences

Sentence types can also be combined. A compound-complex sentence contains at least two independent clauses and at least one dependent clause.

Key: independent clause = yellow, bold ; comma or semicolon = pink, regular font ; coordinating conjunction = green, underlined ; dependent clause = blue, italics

- She completed her literature review , but she still needs to work on her methods section even though she finished her methods course last semester .

- Although he organized his sources by theme , he decided to arrange them chronologically , and he carefully followed the MEAL plan for organization .

- T hey studied APA rules for many hours , and they decided that writing in APA made sense because it was clear, concise, and objective .

- Using some complex-compound sentences in writing allows for more sentence variety .

- Pay close attention to comma usage in complex-compound sentences so that the reader is easily able to follow the intended meaning.

Sentence Structure Video Playlist

Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

- Structuring Sentences: Types of Sentences (video transcript)

- Structuring Sentences: Simple Sentences (video transcript)

- Structuring Sentences: Compound Sentences (video transcript)

- Structuring Sentences: Complex Sentences (video transcript)

- Structuring Sentences: Combining Sentences (video transcript)

- Common Error: Unclear Subjects (video transcript)

- Mastering the Mechanics: Punctuation as Symbols (video transcript)

- Mastering the Mechanics: Commas (video transcript)

- Mastering the Mechanics: Periods (video transcript)

- Mastering the Mechanics: Semicolons (video transcript)

Related Resources

Knowledge Check: Sentence Structure and Types of Sentences

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Main Parts of Speech

- Next Page: Run-On Sentences and Sentence Fragments

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Writing Basics and Resources: Grammar and Figures of Speech

- Research This link opens in a new window

- Writing Reference eBooks

- Grammar and Figures of Speech

- Outlining a Paper

- Academic Integrity This link opens in a new window

- Cover Letters & Resumes

- Internet and Computer Basics

- Copyright Basics

Grammar / Mechanics / Punctuation Handouts

- Clauses and Phrases

- Comma Our Beloved Friend

- Commas and Nonessential Modifiers

- Common Confusions, Quotations, Apostrophes and More

- Common Verb Errors That Can Choke You to Death

- Fragments, Comma Splices and Fused Sentences

- Grammar Rudiments

- Six Comma Rules Guaranteed to Change Your Life

- Understanding and Avoiding Comma Splices

- Grammar Bytes One of the best sites for grammar help. It includes interactive exercises, video tutorials, presentations, and rules for fixing many different kinds of grammar gremlins.

- Grammar: Topic Page Description of the structure of a language, consisting of the sounds (see phonology); the meaningful combinations of these sounds into words or parts of words, called morphemes; and the arrangement of the morphemes into phrases and sentences, called syntax.

- Semantics: Topic Page [Gr.,=significant] in general, the study of the relationship between words and meanings. The empirical study of word meanings and sentence meanings in existing languages is a branch of linguistics; the abstract study of meaning in relation to language or symbolic logic systems is a branch of philosophy.

- Syntax From Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics A traditional term for the study of the rules governing the way words are combined to form sentences in a language. In this use, syntax is opposed to morphology, the study of word structure.

- Punctuation: Topic Page [Lat.,=point], the use of special signs in writing to clarify how words are used; the term also refers to the signs themselves. In every language, besides the sounds of the words that are strung together there are other features, such as tone, accent, and pauses, that are equally significant (see grammar and phonetics).

Parts of Speech

- Parts of speech From Good Word Guide Words can be grouped into classes, commonly called parts of speech, which share the same grammatical function within sentences.

- Nouns From Good Word Guide Nouns are the names of things, places, or people. The main division of nouns is into ‘countable’ and ‘uncountable’: countable nouns are those which can be preceded by a or the, or by a number or word denoting number . . . Uncountable nouns are nouns of mass.

- Adjective: Topic Page Grammatical part of speech for words that describe noun (for example, new, as in ‘a new hat’, and beautiful, as in ‘a beautiful day’).

- Adverb From Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics A term used in the grammatical classification of words to refer to a heterogeneous group of items whose most frequent function is to specify the mode of action of the verb.

Related Terms

- Allusion From The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics A poet’s deliberate incorporation of identifiable elements from other sources, preceding or contemporaneous, textual or extratextual. A. may be used merely to display knowledge, as in some Alexandrian poems; to appeal to those sharing experience or knowledge with the poet; or to enrich a poem by incorporating further meaning.

- Onomatopoeia From The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics The traditional term for words which seem to imitate the things they refer to, as in this line from Collins’ “Ode to Evening”: “Now the air is hushed, somewhere the weak-eyed bat / With short shrill shriek flits by on leathern wing.”

- Hyperbole From The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics A figure or trope, common to all lits., consisting of bold exaggeration, apparently first discussed by Isocrates and Aristotle (Rhetoric 1413a28).

Representation

- Symbolism: Topic Page In the arts, the use of symbols to concentrate or intensify meaning, making the work more subjective than objective. In the visual arts, symbols have been used in works throughout the ages to transmit a message or idea, for example, the religious symbolism of ancient Egyptian art, Gothic art, and Renaissance art.

- Simile From The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics A figure of speech most conservatively defined as an explicit comparison using “like” or “as”—e.g. “black, naked women with necks / wound round and round with wire / like the necks of light bulbs” (Elizabeth Bishop).

- Trope From Encyclopedia of Postmodernism A trope is a figure of speech that denotes or connotes meaning through a chain of associations. It employs a word or phrase out of its ordinary usage in order to further demonstrate or illustrate a particular idea.

- Synecdoche From Encyclopedia of Postmodernism Synecdoche means literally understanding one thing with another; as a rhetorical trope, the substitution of part for whole or vice versa. When defined as the use of an attribute or adjunct as a substitution for that of the thing meant, synecdoche is directly related to metonymy.

- << Previous: Writing Reference eBooks

- Next: Take Notes >>

- Last Updated: May 28, 2024 9:57 AM

- URL: https://library.tctc.edu/writing

The slippery grammar of spoken vs written English

Senior Lecturer in Linguistics, University of Waikato

Disclosure statement

Andreea S. Calude receives funding from the Royal Society Marsden Grant and Catalyst Seeding Grant .

University of Waikato provides funding as a member of The Conversation NZ.

University of Waikato provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

My grammar checker and I are on a break. Due to irreconcilable differences, we are no longer on speaking terms.

It all started when it became dead set on putting commas before every single “which”. Despite all the angry underlining, “this is a habit which seems prevalent” does not need a comma before “which”. Take it from me, I am a linguist.

This is just one of many challenging cases where grammar is slippery and hard to pin down. To make matters worse, it appears that the grammar we use while speaking is slightly different to the grammar we use while writing. Speech and writing seem similar enough – so much so that for centuries, people (linguists included) were blind to the differences.

Read more: How students from non-English-speaking backgrounds learn to read and write in different ways

There’s issues to consider

Let me give you an example. Take sentences like “there is X” and “there are X”. You may have been taught that “there is” occurs with singular entities because “is” is the present singular form of “to be” – as in “there is milk in the fridge” or “there is a storm coming”.

Conversely, “there are” is used with plural entities: “there are twelve months in a year” or “there are lots of idiots on the road”.

What about “there’s X”? Well, “there’s” is the abbreviated version of “there is”. That makes it the verb form of choice when followed by singular entities.

Nice theory. It works for standard, written language, formal academic writing, and legal documents. But in speech, things are very different .

It turns out that spoken English favours “there is” and “there’s” over “there are”, regardless of what follows the verb: “there is five bucks on the counter” or “ there’s five cars all fighting for that Number 10 spot ”.

A question of planning

This is not because English is going to hell in a hand basket, nor because young people can’t speak “proper” English anymore.

Linguists Jen Hay and Daniel Schreier scrutinised examples of old recordings of New Zealand English to see what happens in cases where you might expect “there” followed by plural, (or “there are” or “there were” for past events) but where you find “there” followed by singular (“there is”, “there’s”, “there was”).

They found that the contracted form “there’s” is a go-to form which seems prevalent with both singular and plural entities. But there’s more. The greater the distance between “be” and the entity following it, the more likely speakers are to ignore the plural rule.

“There is great vast fields of corn” is likely to be produced because the plural entity “fields” comes so far down the expression, that speakers do not plan for it in advance with a plural form “are”.

Even more surprisingly, the use of the singular may not always necessarily have much to do with what follows “there is/are”. It can simply be about the timing of the event described. With past events, the singular form is even more acceptable. “There was dogs in the yard” seems to raise fewer eyebrows than “there is dogs in the yard”.

Nothing new here

The disregard for the plural form is not a new thing (darn, we can’t even blame it on texting). According to an article published last year by Norwegian linguist Dania Bonneess , the change towards the singular form “there is” has been with us in New Zealand English ever since the 19th century. Its history can be traced at least as far back as the second generation of the Ulster family of Irish emigrants .

Editors, language commissions and prescriptivists aside, everyday New Zealand speech has a life of its own, governed not so much by style guides and grammar rules, but by living and breathing individuals.

It should be no surprise that spoken language is different to written language. The most spoken-like form of speech (conversation) is very unlike the most written-like version of language (academic or other formal or technical writing) for good reason.

Speech and writing

In conversation, there is no time for planning. Expressions come out more or less off the cuff (depending on the individual), with no ability to edit, and with immediate need for processing. We hear a chunk of language and at the same time as parsing it, we are already putting together a response to it – in real time.

This speed has consequences for the kind of language we use and hear. When speaking, we rely on recycled expressions, formulae we use over and over again, and less complex structures.

For example, we are happy enough writing and reading a sentence like:

That the human brain can use language is amazing.

But in speech, we prefer:

It is amazing that the human brain can use language.

Both are grammatical, yet one is simpler and quicker for the brain to decode.

And sometimes, in speech we use grammatical crutches to help the brain get the message quicker. A phrase like “the boxes I put the files into” is readily encountered in writing, but in speech we often say and hear “the boxes I put the files into them”.

We call these seemingly unnecessary pronouns (“them” in the previous example) “shadow pronouns”. Even linguistics professors use these latter expressions no matter how much they might deny it.

Speech: a faster ride

There is another interesting difference between speech and writing: speech is not held up on the same rigid prescriptive pedestal as writing, nor is it as heavily regulated in the same way that writing is scrutinised by editors, critics, examiners and teachers.

This allows room in speech for more creativity and more language play, and with it, faster change. Speech is known to evolve faster than writing, even though writing will eventually catch up (at least for some changes).

I would guess that by now, most editors are happy enough to let the old “whom” form rest and “who” take over (“who did you give that book to?”).

- New Zealand

- Linguistics

- Spoken language evolution

- written language

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

Chief Operating Officer (COO)

Clinical Teaching Fellow

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

He Said, She Said: How to Use Speech Tags & Dialogue Tags Effectively

by Fija Callaghan

What is dialogue?

Dialogue is the spoken interaction between two or more characters. Usually, dialogue is spoken out loud, but it can also be things like sign language or telekinesis — it’s any form of expression, as long as the characters can understand each other. Dialogue can be used to develop characters, convey exposition about your story’s world, or move the plot forward.

Ultimately, learning how to write dialogue in a story is one of the most important skills in a writer’s toolbox.

In order to write clear, concise dialogue that will elevate your story and engage your readers, you’ll need to understand how to use dialogue tags. Also called speech tags, these unassuming words can make or break an otherwise well-written scene. But what is a dialogue tag, exactly, and how do we use it to take our story to the next level? By following a few basic principles, you’ll be writing compelling dialogue in no time. Let’s dive in.

What are dialogue tags?

Dialogue tags (or speech tags) are short phrases that identify the speaker of a line of dialogue. They can occur before, during, or after a character’s spoken dialogue. They’re used to make it clear who’s speaking and help the reader follow the conversation. The most common dialogue tag in writing is “he said” or “she said.”

There are a few different ways to write dialogue tags, and we’ll look at them all in more detail below. Here’s a quick example:

“I made some coffee,” said Julie.

Here, “‘I made some coffee’” is the dialogue, and “said Julie” is the dialogue tag. They both appear on the same line in the story.

Why do we use dialogue tags in fiction writing?

We use dialogue tags and speech tags in a story to clarify who’s talking so that the reader doesn’t get confused, as well as to give more depth and context to the words that are being said. If your on-page conversation goes too long without a dialogue tag, your reader can lose track of who’s saying what. When this happens, they need to stop reading, go back to the top of the conversation, and count each line to try and remember whose turn it is to talk. At this point, you’ve broken their connection to the story.

However, be mindful of using repetitive dialogue tags. Punctuating dialogue with too many tags is one of the common mistakes new writers often make. Using too many can weigh down the actual dialogue and distract from the story. Instead, use tags only when needed or when they add another layer to the characters speaking.

Dialogue tags also give us a way to break up long stretches of story dialogue, to add movement to the scene, and to reveal something new about the character. Here are a few examples of effective dialogue tags:

“So you’re finally done with that jerk?” he said, leaning forward.

She took a sip of her drink. “Looks that way.”

The first speaker has an action attached to his speech tag that gives us a hint about how he’s feeling. The second speaker has an action preceding her dialogue that also gives a hint about how she’s feeling. With just these two simple lines, we can already imagine the story building up around them.

Sometimes, a speech tag can change the inflection of a line of story dialogue. For example,

“Look at that!” he said, spreading his cards out on the table. “A full house.”

“You’ve had a lot of luck this evening,” said John irritably.

What if we changed the dialogue tag?

“You’ve had a lot of luck this evening,” said John, grinning.

The dialogue stays exactly the same, but the context and the relationship between the two characters shifts because we’ve used a different dialogue tag. If you were to just use “said John” as your dialogue tag, the reader could imagine several different scenarios. You’d have to find other places to sneak in the background information they needed to understand the dialogue’s subtext.

Used in this way, a well-placed dialogue tag can communicate something a lot bigger about your story. We’ll look at different ways to say “said” in writing and other words for “said” when writing story dialogue later on in this article.

You may also notice that the capitalization changes when the line ends in an exclamation mark. We’ll take a closer look at placing dialogue tags and the rules of appropriate punctuation below.

When to use speech tags in writing

You’ll notice from the examples above that the placement of the dialogue tags can shift from one line to another; they don’t always stay in the same place. Let’s look at how to format dialogue when using dialogue tags before, during, and after a line of speech.

How to use speech tags before dialogue

In some older novels, you’ll see speech tags being used before the dialogue:

Shane said, “I didn’t think you’d mind.”

This sentence structure has generally fallen out of favor in contemporary writing. The exception? If your character is quoting someone else:

“And then what happened?”

“Well, then Shane said, ‘I didn’t think you’d mind.’”

Usually, the best way to use a dialogue tag before a line of speech is to choose an action for your character:

Sheila gasped. “He really said that?”

Here, the action tag identifies Sheila as the speaker. We’ll look closer at using action tags further below.

How to use speech tags in the middle of dialogue

Using dialogue tags can be a good way to break up long lines of dialogue, to imply a natural pause in the line, or to convey a shift in tone. For example:

“I just feel so tired all the time,” she said. “Like nothing matters anymore.”

Compare with the dialogue tag used at the end:

“I just feel so tired all the time. Like nothing matters anymore,” she said.

In the latter, the line of dialogue feels faster, like a singular thought. In the former, we feel like the speaker has paused for breath, or paused to add a new idea. Neither one of these is right or wrong; it’s up to you to decide which one is the best fit for that particular moment of your story.

Here’s another example:

“I just feel so tired all the time. Like nothing matters anymore,” she said. “But after tomorrow, things will be different.”

Here, the dialogue tag serves as an axis between one tone and another. The line begins feeling despondent, hinges on the dialogue tag, and ends feeling hopeful.

How to use tags at the end of the dialogue

Many contemporary writers favor placing speech tags after a line of dialogue. For example:

“It smells wonderful in here,” said Kate.

This structure puts the emphasis on the dialogue, rather than the dialogue tag. The reader’s attention focuses on what the character is saying, and the speech tag works on a near-subconscious level to make sure they don’t get confused about who’s saying what.

You can also give the character an action after their dialogue:

“It smells wonderful in here.” Kate opened the oven and peeked inside.

This gives the reader a bit more context about what’s happening and makes the scene come alive.

How to punctuate dialogue tags

You may have noticed in some of these examples that the punctuation in a dialogue tag can change. Let’s take a closer look at how to format dialogue tags, as well as some alternative speech tag formats you might come across in literature.

Using double and single quotation marks

In North American literature, lines of dialogue are enclosed in double quotation marks, like this:

“I love this song.”

In European English, however, you’ll often see single quotation marks used instead, like this:

‘I love this song.’

For this article we’ll be focusing on using standard North American grammar.

If your dialogue stands alone without any speech tag (like just above), you’ll end the line in a period. If you’re adding a speech tag in the form of a verb that describes the dialogue—said, whispered, shouted, etc—you’ll end the line of dialogue in a comma just before the closing quotation mark, and start the dialogue tag with a lowercase letter:

“I love this song,” she said.

(Unless your dialogue tag begins with a proper noun, such as “Charlotte said”—always capitalize these!)

However , if you follow the line of dialogue with an action that is separate from the speech, you’ll end the dialogue with a period and begin the next bit with a capital letter, the same as if you didn’t use any tag at all:

“I love this song.” She reached over and turned up the volume.

Always include your dialogue’s punctuation inside quotation marks.

So far so good? Now things are about to get a little weird. What happens if your dialogue ends in a question mark or an exclamation point? Strangely enough, the rules for capitalization actually stay the same:

“I love this song!” she said.

“I love this song!” She reached over and turned up the volume.

North American English does use single quotation marks too. As we saw in one of our earlier examples, single quotes are used for dialogue within dialogue. This is called “nested dialogue.”

“In the words of Shakespeare, ‘To thine self be true.’”

“I was on my way out when I overheard him say, ‘I’ll meet you at our old spot.’ What old spot was he talking about?”

In European English, the rules for nested dialogue is reversed, like this:

‘I was on my way out when I overheard him say, “I’ll meet you at our old spot.” What old spot was he talking about?’

Sometimes you’ll see dialogue being set off from the rest of the text with em-dashes. This can create a vivid, cinematic effect in your writing; however, you’ll have to be very careful that your dialogue doesn’t blur into your narrative. Here’s an example from Roddy Doyle’s Oh, Play That Thing :

—I want an American suit, I told him.

—Suit? I had the rest of the anarchist’s cash burning a hole in the pocket of my old one.

—American, I told him.—A good one.

You can see how the dialogue tags—“I told him”—are kept deliberately simple, and the longer action is set apart on its own line. The em-dashes show us when the speech starts up again. However, this type of dialogue punctuation is very rare and experimental; the safest option is always to use standard quotation marks, like we looked at above.

No punctuation

Sometimes authors will experiment with using no distinguishing punctuation at all. This makes the story read very smoothly and intimately, like the reader is really there in person. However, just like using em-dashes, care must be taken to keep the dialogue and the narrative very distinct from each other so that the reader understands what’s being said and what’s being thought or described.

Here’s an example from The Houseboat , by Dane Bahr:

This have something to do with that grave robbery?

No sir, Clinton said. I don’t believe so. That was down in Cedar Rapids.

I see. Well. Ness leaned back and closed his eyes again. What can I do for you, Deputy?

Yeh get the mornin paper up there? The Tribune I think it is?

Looking at it right now, Ness said. He leaned forward in his chair and looked at the picture on the front page.

Even though this is written in third person narrative, you can see how each dialogue tag begins with a name—“Clinton said,” rather than “said Clinton.” This gives the reader a subconscious cue that the words are shifting from dialogue to description. Stripping away the punctuation of your dialogue like this gives the reader a feeling like they’re listening in on a private conversation in the next room.

Experimenting with alternative dialogue tag punctuation can be a great way to stretch your comfort zone as a writer. However, clarity for the reader should always be at the forefront of your mind.

These two alternative punctuation methods are fun to work with, but they are very experimental and an unusual choice in modern literature. In professional writing, both fiction and non-fiction, quotation marks are the universal standard.

Other words for “said” when writing dialogue

Writers are big fans of using “said” for their dialogue tags, because it doesn’t draw attention away from what really matters: your story. But sometimes you might want to enhance your dialogue tag with another word to give it some more emphasis. Let’s look at different ways to say “said” in writing.

How to use verbs as dialogue tags

You may remember your primary school teacher telling you to look for other words for “said” in dialogue: whispered, shouted, chastised, sulked, muttered, screeched, sobbed… you can have a lot of fun digging up synonyms for “said” in story dialogue, but most of the time, less is more. You want your reader’s attention to be on the words that your characters are saying and the story surrounding them, rather than the mechanics of your dialogue tags.

However, there are times when using a different verb for your speech tag can enhance the narrative or convey new information. For example, compare the following:

“I hate you,” she said.

“I hate you!” she shouted.

“I hate you,” she whispered.

Each dialogue tag gives the line a slightly different feel. Because the words are so simple, “said” feels a bit empty and non-committal; using a different word gives the reader context for the words that are being spoken.

Now compare these two lines:

“Look at the state of your clothes! People are going to think you’ve been sleeping in a barn,” she chastised.

“Look at the state of your clothes! People are going to think you’ve been sleeping in a barn,” she said.

In this instance, the verb “chastised” is redundant because we can already tell that she’s chastising from what she’s saying. It doesn’t give the reader any new information. In this case, it’s better to fall back on “said” and allow the dialogue to do the (literal and figurative) talking.

When you’re considering using other verbs for your speech tag, ask yourself if it reveals something new about what the person is saying. If not, simpler is always better.

How to use dialogue tags with adverbs

Adverbial dialogue tags are where you use a modifying word to enhance your dialogue tag, such as “said angrily,” or “whispered venomously.” As with using other verbs instead of “said,” most of the time, less is more. However, sometimes using adverbial tags can contribute surprising new information about the scene.

Consider these examples:

“I hate you,” she said scathingly.

“I hate you,” she said gleefully.

“I hate you,” she said nervously.

Each adverb tells us something different about what’s being said. But do you need them?

Telling someone you hate them is already pretty scathing, so you probably don’t need to show it a second time with your dialogue tag. Saying it gleefully is very different in tone, and makes us wonder: what’s this person so happy about? What makes this moment special to her? Saying it nervously is different again, and raises questions about the scene—is this the first time it’s been said? What are the consequences for saying it?

“Gleefully” is probably the strongest adverb choice in these examples, because it’s at odds with what’s being spoken; it gives the line a whole new context. “Nervously” is nicely specific too, but you can also find other ways to show nervousness in the character’s actions, which might feel more natural and organic to the reader. “Scathingly” doesn’t really tell us anything new about what’s being said.

When considering adverbs for your dialogue tag, again ask yourself if they communicate something new to the reader that the dialogue doesn’t show on its own. If it does, then ask yourself if it communicates that something in the most natural, efficient way possible. You can explore different ways of conveying these emotions or details in your scene to find which one works best for your dialogue.

Dialogue tags vs. actions tags

Dialogue tags, as we’ve seen, begin with a speech verb—usually “said,” but sometimes other words like “whispered,” “yelled,” or “mumbled.” They work to identify the person who is speaking.

Action tags, on the other hand, work like a dialogue tag but aren’t directly connected to the line of dialogue. They can be related, but they stand independently. Just like dialogue tags, action tags work to identify the person speaking. These are especially helpful if you’re writing a scene with three or more people, where things can get confusing pretty quickly.

Additional speech tags examples

Here’s an example of action tags and dialogue tags working together:

“So here’s how it’s going to go down,” said Donny. “We’ll meet at midnight, after the cinema closes.”

Mark took a sip of his drink. “What about the night patrol?”

“The night patrol is a sixteen-year-old kid on minimum wage.” Roger leaned back in his chair. “You worry too much.”

“I’m not getting rough with a kid, Donny.”