What Is Sports Psychology?

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Sports psychology is the study of psychological factors that influence athletic performance and how participation in sports and exercise can affect the psychological and physical well-being of athletes.

Researchers in this field explore how psychology can be used to optimize athletic performance and how exercise can be utilized to improve mood and lower stress levels.

Sports psychologists teach cognitive and behavioral strategies to help athletes improve their experiences, athletic performance, and mental wellness when participating in sports.

They can assist with performance enhancement, motivation, stress management, anxiety control, or mental toughness. They also can help with injury rehabilitation, team building, burnout, or career transitioning.

Sports psychologists don”t just work with athletes. They can work with coaches, parents, administrators, fitness professionals, performers, organizations, or everyday exercises to demonstrate how we can utilize exercise, sport, and athletics to enhance our lives and psychological development.

Types of Sports Psychologists

Educational sports psychologists.

An educational sports psychologist educates clients on how to utilize psychological skills effectively to enhance sports performance and manage the mental factors of sports.

These skills could include goal setting, imagery, self-talk, or energy management (discussed in more detail below).

Clinical Sports Psychologists

Clinical sports psychologists work with athletes who have mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders, or substance abuse.

They utilize strategies from both sports psychology and psychotherapy, helping athletes improve their mental health and sports performance concurrently. Being a clinical psychologist requires a doctoral degree in clinical or counseling psychology.

Commonly Used Techniques

Arousal regulation.

- Arousal regulation techniques involve the control of the overall level of neuronal activity, and thus arousal levels, in the brain. Arousal refers to how emotionally activated an athlete is before or during performance.

- Techniques for arousal regulation could include muscle relaxation, deep breathing, medication, listening to music, or mindfulness.

- The role of a sports psychologist is to assist an athlete in reaching their optimal level of arousal at which their athletic performance is maximized.

Goal Setting

- Goal setting involves planning out ways to achieve an accomplishment and envisioning the outcome you are pursuing.

- These goals should be specific, measurable, attainable, time-based, and challenging.

- You can make outcome goals, performance goals, or process goals.

- Imagery refers to using multiple senses to create mental images of experiences in your mind.

- Athletes use imagery to practice activating the muscles associated with an action, recognizing patterns in activities and performance, making mental recreations of an event or game, or visualizing correcting a mistake or doing something properly.

Pre-Performance Routines

- A pre-performance routine refers to the actions, behaviors, or methods an athlete implements before for a game or performance.

- This could include eating the same foods, putting on clothes in a particular order, listening to a specific playlist of songs, wearing specific clothing, or warming up in a particular way.

- This helps develop stability and predictability, triggering concentration and decreasing anxiety levels.

- Self-talk refers to the inner monologues, whether thoughts, words, or quotes, we say to ourselves.

- Athletes can utilize self-talk to instill optimism, improve focus, manage stress, or inspire confidence.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation is a technique within arousal regulation. It involves alternating between tensing and relaxing target muscle groups.

- This helps with lowering blood pressure, reducing state anxiety, improving performance, and decreasing stress hormones.

Hypnosis involves being in a state of increased attention, concentration, and suggestibility. Sports psychologists sometimes use this strategy to help clients control state anxiety and arousal levels. Most typically, though, it is used among health psychologists to help patients quit smoking.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- CBT is a type of psychotherapeutic treatment that helps people identify and change destructive thinking patterns, emotional responses, or behaviors.

- While CBT is used by all kinds of people, athletes could especially benefit from its effects.

Biofeedback

- Biofeedback involves using external technology to measure one’s internal physiological processes such as heart rate, brain waves, or muscle tension.

- This information can be used to monitor or control these effects to maximize performance and obtain a more beneficial biological response.

How to Become a Sports Psychologist

Most positions in this field require a master’s or doctoral degree in clinical, counseling, or sport psychology. You are also required to take classes in kinesiology, physiology, sports medicine, business and marketing.

Then, you must practice directly under a licensed psychologist for at least two years. In order to obtain a professional board certification from

The American Board of Sport Psychology, you must pass a qualifying exam. Board certification is not required for a state license, but many employers prefer or require it.

Specialties within this field could include applied sport psychology, clinical sport psychology, or academic sport psychology.

The salaries for sports psychologists vary depending on whether you are in private practice or work within a team or organization.

The American Psychological Association (APA) reports that sport and performance psychologists in university athletic departments can earn $60,000 to $80,000 a year, while salaries working in a private practice can exceed $100,000 annually.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can sports psychologists prescribe medications.

A sports psychologist cannot prescribe medication unless they have a medical degree. If a sports psychologist has this degree, then they are usually referred to as a sports psychiatrist. Sports psychiatrists are medical doctors who serve a similar role as sports psychologists, but they focus more on psychopathology and mental disorders in athletes.

What jobs can I get with a sports psychology degree?

In addition to being a licensed clinical sport psychologist, you could also be a mental performance consultant, a personal trainer, a sports coach, a research specialist, a sports psychology professor, or a physical therapist, to name a few.

Why is sports psychology important?

Mental health and overall well-being are fundamental to athletic competition and performance.

Seeking the support of a sports psychologist can help athletes achieve their overall performance improvement goals.

Sports psychologists can help better one’s attitude, focus, confidence, and mental game, empowering athletes to stay engaged in the sports they love.

How does sports psychology help athletes?

Sports psychology can help athletes and non-athletes cope with the pressures of competition, enhance athletic performance, and achieve their goals.

Mental training alongside physical training is more profitable than physical training alone. Athletes can learn to overcome pressures associated with sporting performance and develop more focus, commitment, and enjoyment.

Where can you study sports psychology?

There are both undergraduate and graduate degrees available in sports psychology. Several colleges and universities offer undergraduate bachelor’s degrees and/or master’s and doctoral degrees in clinical, counseling, or sport psychology.

Depending on the institution, you might also be able to study sports psychology online.

How can sports psychology improve performance?

Sports psychology can improve performance in several ways – reducing anxiety, enhancing focus, improving mental toughness, developing confidence, adopting a healthy level of motivation, or uncovering obstacles that might be limiting an athlete’s performance.

American Psychological Association. (2014). Pursuing a career in sport and performance psychology. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/educationcareer/guide/subfields/performance/education-training

Audette, J., & Bailey, A.M. (2007). CHAPTER 23 – Complementary and Alternative Medicine and the Athlete.

Cherry, K. (2022, February 14). An overview of sports psychology. Verywell Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-sports-psychology-2794906#toc-what-is-sports-psychology

Psychology.org Staff. (2022, February 16). How to become a sports psychologist. Psychology.org | Psychology’s Comprehensive Online Resource. Retrieved from https://www.psychology.org/careers/sports-psychologist/

Sports psychology: Mindset can make or break an athlete. Oklahoma Wesleyan University. (2018, July 5). Retrieved from https://www.okwu.edu/news/2018/07/sports-psychology-make-or-break/

Related Articles

Soft Determinism In Psychology

Branches of Psychology

Social Action Theory (Weber): Definition & Examples

Adult Attachment , Personality , Psychology , Relationships

Attachment Styles and How They Affect Adult Relationships

Personality , Psychology

Big Five Personality Traits: The 5-Factor Model of Personality

Learning Theories , Psychology

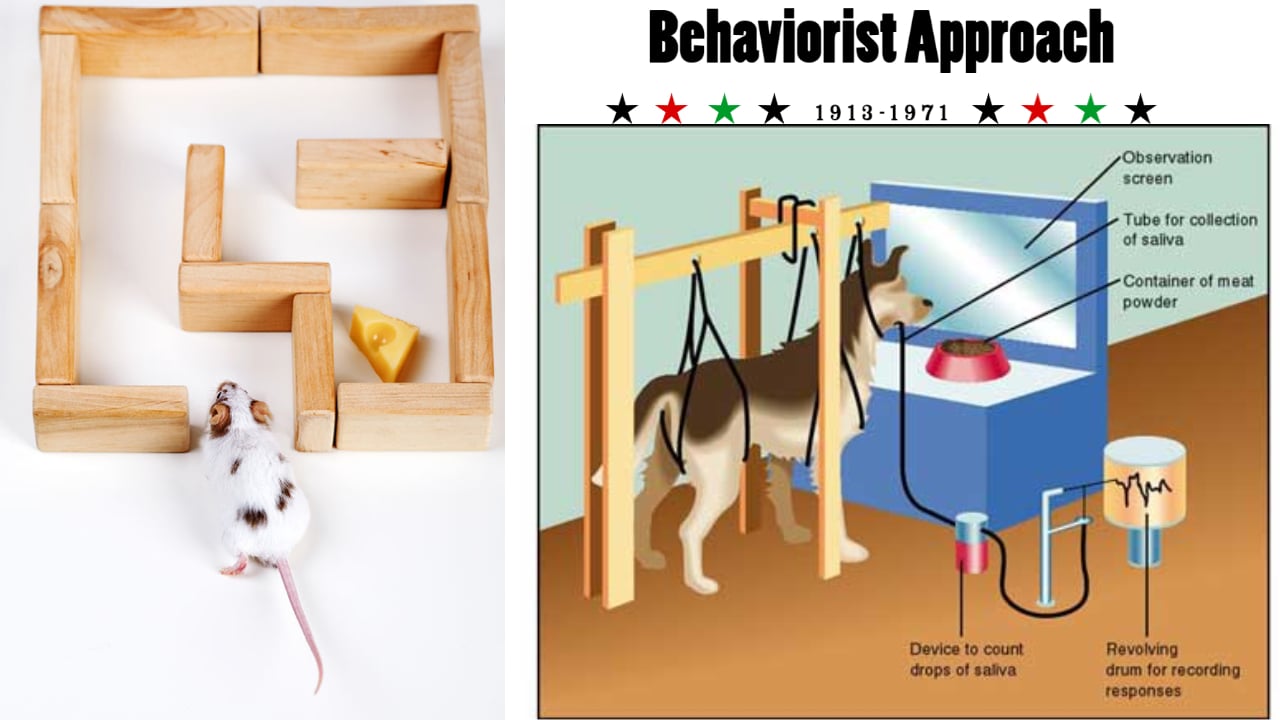

Behaviorism In Psychology

What Is Sports Psychology? 9 Scientific Theories & Examples

And maintaining focus when your team is behind and heading into the final few minutes of the game requires mental toughness.

Sports are played by the body and won in the mind, says sports psychologist Aidan Moran (2012).

To provide an athlete with the mental support they need, a sports psychologist considers the individual’s feelings, thoughts, perceived obstacles, and behavior in training, competition, and their lives beyond.

This article introduces some of the key concepts, research, and theory behind sports psychology and its ability to optimize performance.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

What is sports psychology, 4 real-life examples, 5 theories and facts of sports psychology, why is sports psychology important, brief history of sports psychology, top 4 sports psychology podcasts, positivepsychology.com’s helpful resources, a take-home message.

“Sport psychology is about understanding the performance, mental processes, and wellbeing of people in sporting settings, taking into account psychological theory and methods.”

Meijen, 2019

Sports psychology is now widely accepted as offering a crucial edge over competitors. And while essential for continuing high performance in elite athletes, it also provides insights into optimizing functioning in areas of our lives beyond sports.

As a result, psychological processes and mental wellbeing have become increasingly recognized as vital to consistently high degrees of sporting performance for athletes at all levels where the individual is serious about pushing their limits.

Indeed, as cognitive scientist Massimiliano Cappuccio (2018) writes, “physical training and exercise are not sufficient to excel in competition.” Instead, key elements of the athlete’s mental preparation must be “perfectly tuned for the challenge.”

For example, in recent research attempting to understand endurance limits , psychological variables have been confirmed as the deciding factor in ceasing effort rather than muscular fatigue (Meijen, 2019). The brain literally limits the body.

Beyond endurance, mental processes are equally crucial in other aspects of sporting success, such as maintaining focus, overcoming injury, dealing with failure, and handling success.

As psychologists, we can help competitors enhance their performance by “providing advice on how to be their best when it matters most” (Moran, 2012).

Pushing from within

As long ago as 2008, Tiger Woods confirmed the importance of his mental strength and ability to push himself from within (Moran, 2012):

“It’s not about what other people think and what other people say. It’s about what you want to accomplish and do you want to go out there and be prepared to beat everyone you play or face?”

And golf experts agree. While Tiger Woods’s natural gifts are self-evident, you can never count him out when he is losing, because of his robust mindset. He is always prepared and always has a plan (Bastable, 2020).

Vision and the right mindset will overcome

When sports scientist and motivational expert Greg Whyte met Eddie Izzard, the British comedian didn’t even own a pair of running shoes. Yet Whyte had six weeks to prepare her for the monumental challenge of running 43 consecutive marathons.

Vision, belief, science-led training, psychological support, and Izzard’s epic degree of determination were the essential ingredients that resulted in success (Whyte, 2015).

Reframing arousal

When sports psychologist John Kremer was approached by an international sprinter complaining that pre-race anxiety was impacting his races, he took time to understand what he was experiencing and how it felt.

Kremer helped reframe the athlete’s perception of his pounding heart from stress negatively affecting his performance to being primed and ready for competition (Kremer, Moran, & Kearney, 2019).

Visualizing success

Diver Laura Wilkinson broke three bones in her foot in the lead-up to the U.S. trials for the 2000 Olympics.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Sports psychology is not one theory, but the combination of many overlapping ideas and concepts that attempt to understand what it takes to be a successful athlete.

Indeed, in many sports, endurance in particular, there has been a move toward more multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches, looking at the interactions between psychological, biomechanical, physiological, genetic, and training aspects of performance (Meijen, 2019).

With that in mind, and considering the many psychological constructs affecting performance in sports, the following areas are some of the most widely studied:

- Mental toughness

- Goal setting

- Anxiety and arousal

1. Mental toughness

Coaches and athletes recognize mental toughness as a psychological construct vital for performance success in training and competition (Gucciardi, Peeling, Ducker, & Dawson, 2016).

Mental toughness helps maintain consistency in determination, focus, and perceived control while under competitive pressure (Jones, Hanton, & Connaughton, 2002).

While much of the early work on mental toughness relied on the conceptual understanding of the related concepts of resilience and hardiness, reaching an agreed upon definition has proven difficult (Sutton, 2019).

Mentally tough athletes are highly competitive, committed, self-motivated , and able to cope effectively and maintain concentration in high-pressure situations. They retain a high degree of self-belief even after setbacks and persist when the going gets tough (Crust & Clough, 2005; Clough & Strycharczyk, 2015).

After interviewing sports professionals competing at an international level, Jones et al. (2002) found that being mentally tough takes an unshakeable self-belief in the ability to achieve goals and the capacity and determination to bounce back from performance setbacks.

Mental toughness determines “how people deal effectively with challenges, stressors, and pressure… irrespective of circumstances” (Crust & Clough, 2005). It is made up of four components, known to psychologists as the “four Cs”:

- Feeling in control when confronted with obstacles and difficult situations

- Commitment to goals

- Confidence in abilities and interpersonal skills

- Seeing challenges as opportunities

For athletes and sportspeople, mental toughness provides an advantage over opponents, enabling them to cope better with the demands of physical activity.

Beyond that, mental toughness allows individuals to manage stress better, overcome challenges, and perform optimally in everyday life.

2. Motivation

Motivation has been described as what maintains, sustains, directs, and channels behavior over an extended amount of time (Ryan & Deci, 2017). While it applies in all areas of life requiring commitment, it is particularly relevant in sports.

Not only does motivation impact an athlete’s ability to focus and achieve sporting excellence, but it is essential for the initial adoption and ongoing continuance of training (Sutton, 2019).

While there are several theories of motivation, the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) has proven one of the most popular (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Based on our inherent tendency toward growth, SDT suggests that activity is most likely when an individual feels intrinsically motivated, has a sense of volition over their behavior, and the activity feels inherently interesting and appealing.

Optimal performance in sports and elsewhere occurs when three basic needs are met: relatedness, competence, and autonomy (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

3. Goal setting and focus

Setting goals is an effective way to focus on the right activities, increase commitment, and energize the individual (Clough & Strycharczyk, 2015).

Goal setting is also “associated with increased wellbeing and represents an individual’s striving to achieve personal self-change, enhanced meaning, and purpose in life” (Sheard, 2013).

A well-constructed goal can provide a mechanism to motivate the individual toward that goal. And something big can be broken down into a set of smaller, more manageable tasks that take us nearer to achieving the overall goal (Clough & Strycharczyk, 2015).

Athletes can use goals to focus and direct attention toward actions that will lead to specific improvements; for example, a swimmer improves their kick to take 0.5 seconds off a 100-meter butterfly time or a runner increases their speed out of the blocks in a 100 meter sprint.

Goal setting can define challenging but achievable outcomes, whatever your sporting level or skills.

A specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound (SMART) goal should be clear, realistic, and possible. For example, a runner may set the following goal:

Next year, I want to run the New York City Marathon in three hours by completing a six-month training schedule provided by a coach .

4. Anxiety and arousal

Under extreme pressure and in situations perceived as important, athletes may perform worse than expected. This is known as choking and is typically caused by being overly anxious (Kremer et al., 2019).

Such anxiety can have cognitive (erratic thinking), physical (sweating, over-breathing), and behavioral (pacing, tensing, rapid speech) outcomes. It typically concerns something that is not currently happening, such as an upcoming race (Moran, 2012).

It is important to distinguish anxiety from arousal . The latter refers to a type of bodily energy that prepares us for action. It involves deep psychological and physiological activation, and is valuable in sports.

Therefore, if psychological and physiological activation is on a continuum from deep sleep to intense excitement , the sportsperson must aim for a perceived sweet spot to perform at their best. It will differ wildly between competitors; for one, it may be perceived as unpleasant anxiety, for another, nervous excitement.

The degree of anxiety is influenced by (Moran, 2012):

- Perceived importance of the event

- Trait anxiety

- Attributing outcomes to internal or external factors

- Perfectionism – setting impossibly high standards

- Fear of failure

- Lack of confidence

While the competitor needs a degree of pressure (or arousal) and nervous energy to perform at their best, too much may cause them to crumble. Sports psychologists work with sportspeople to better understand the pressure and help manage it through several techniques including:

- Visualization

- Breathing and slowing down

- Sticking to pre-performance routines

Ultimately, it may not be the amount of arousal that affects performance, but its interpretation.

5. Confidence

While lack of confidence is an essential factor in competition anxiety, it also plays a crucial role in mental toughness.

As Gaelic footballer Michael Nolan says, “it’s not who we are that holds us back; it’s who we think we’re not” (Clough & Strycharczyk, 2015).

Confidence is ultimately a measure of how much self-belief we have to see through to the end something beset with setbacks.

Those with a high degree of self-confidence will recognize that obstacles are part of life and take them in stride. Those less confident may believe the world is set against them and feel defeated or prevented from completing their task (Clough & Strycharczyk, 2015).

Self-confidence also taps into other, similar self-regulatory beliefs such as staying positive and maintaining self-belief (Sheard, 2013). An athlete high in self-confidence will harness their degree of self-belief and meet the challenge head on.

However, there are risks associated with being too self-confident. Overconfidence in abilities can lead to taking on too much, intolerance, and the inability to see underdeveloped skills.

And yet, that can only ever be part of the success story.

Sports place tremendous pressure on the competitor’s mind in competition and in training, and that pressure must be supported by robust and reliable psychological constructs (Kumar & Shirotriya, 2010).

The abilities to maintain focus under such pressure and also control actions during extreme circumstances of uncertainty can be strengthened by the mental training and skills a sports psychologist provides.

Mental preparation helps ready the individual and team for competition and offers an edge over an adversary while optimizing performance.

Not only that, but the skills learned in sports psychology are transferable; we can take them to other domains such as education and the workplace.

Jim Loehr and Tony Schwartz (2018) recognized the parallels between achieving “sustained high performance in the face of ever-increasing pressure and rapid change” in the workplace and on the sports field.

Perhaps the earliest known formal study of the mental processes involved in sports can be attributed to Triplett in 1898.

Triplett explored the positive effect of having other competitors to race against in the new sport of cycling. He found that the presence of others enhances the performance of well-learned skills.

In the decades that followed, the focus turned to a range of sports, including archery and baseball, with the first dedicated psychology research center called the Athletic Research Laboratory set up at the University of Illinois in 1925.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that sports psychology formally emerged as a distinct discipline from psychology, specifically with the International Society of Sport Psychology in 1965. However, it wasn’t until 1986 that sports psychology had its own division in the American Psychology Association (Moran, 2012).

The following recommendations all engage with professional psychologists, coaches, and competitors to provide psychological theory and practical guidance:

- Mental Preparation Secrets of Top Athletes, Entertainers, and Surgeons In this episode of Harvard Business Review’s IdeaCast, Dan McGinn talks about how top performers in sports and the world of business “prepare for their big moments.”

- Science of Ultra A podcast that explores the psychology and physiology of endurance through fascinating conversations with scientists, psychologists, trainers, coaches, and athletes.

- The Sport Psych Show Sports psychologist Dan Adams takes listeners on a journey to demystify the psychological tools and techniques available to drive sporting participation and performance.

- Sports Psychology Podcast by Peaksports.com Patrick Cohn helps athletes, coaches, and sports parents understand how to adopt the right mindset to improve confidence and boost performance.

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

We have many tools and worksheets that can help you or your clients identify and work toward goals, develop resilience, and grow self-confidence:

- Setting SMART+ Goals Capture SMART goals and their accountability to ensure they receive the appropriate focus to ensure completion.

- Confidence Booster Add confidence boosters to your daily and weekly schedule.

- Understanding Self-Confidence Gain insight into your self-confidence and use that understanding to begin to improve your self-esteem.

- 17 Motivation & Goal-Achievement Exercises If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others reach their goals, this collection contains 17 validated motivation & goals-achievement tools for practitioners. Use them to help others turn their dreams into reality by applying the latest science-based behavioral change techniques.

- Sports Psychology Books Another great way to get a better understanding of Sports Psychology, is to read recommended books. Our article listing the top 20 Sports Psychology Books is the perfect place to start.

- Sports Psychology Techniques & Tips Explore these Sports Psychology techniques and tips that can help athletes up their game, overcome obstacles, and deliver peak performances.

- Sports Psychology Courses Last but not least, to find out where you can study Sports Psychology, this article shares 17 of the best Sports Psychology Degrees, Courses, & Programs .

Becoming an elite performer results from years of careful planning and hard work. The winners get to the top by identifying, defining, and achieving a series of smaller goals along the way to reaching the podium.

But being at that level takes sustainable motivation and the ability to remain calm under considerable pressure. Successful performance requires the right mindset and psychological tools to allow the sportsperson to overcome both defeat and success. Neither of which is easy.

Modern athletes (professional and amateur), coaches, and team managers recognize the challenges within their sport and the competitive edge gained from seeking sports psychologists’ help.

Time-crunched athletes require focused, pragmatic support and solutions that allow them to deliver a consistent high-quality performance.

Even in the world outside the sporting arena, we are all competing. Understanding the psychological mechanisms involved in overcoming obstacles, hitting our goals, and achieving success is invaluable.

As academic philosopher David Papineau writes, many have come to realize that “sporting prowess has much to teach us about the workings of our minds” (Cappuccio, 2018).

Review the examples, theories, and approaches introduced in this article, and consider how they can benefit performance at any level of competition and be applied to manage stress, overcome obstacles, and improve performance.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

- Afremow, J. A. (2014). The champion’s mind: How great athletes think, train, and thrive . Rodale.

- Bastable, A. (2020). Secret to Tiger Woods’ success was revealed in these 2 remarkable hours. Golf. Retrieved March 5, 2021, from https://golf.com/news/secret-tiger-woods-success-revealed-2-hours/

- Cappuccio, M. (2018). Handbook of embodied cognition and sport psychology . MIT Press.

- Clough, P., & Strycharczyk, D. (2015). Developing mental toughness: Coaching strategies to improve performance, resilience and wellbeing . Kogan Page.

- Crust, L., & Clough, P. J. (2005). Relationship between mental toughness and physical endurance. Perceptual and Motor Skills , 100 , 192–194.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality , 19 , 109–134.

- Gucciardi, D. F., Peeling, P., Ducker, K. J., & Dawson, B. (2016). When the going gets tough: Mental toughness and its relationship with behavioural perseverance. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport , 19 (1), 81–86.

- Jones, G., Hanton, S., & Connaughton, D (2002). What is this thing called mental toughness? An investigation with elite performers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology , 14 , 211–224.

- Kremer, J., Moran, A. P., & Kearney, C. J. (2019). Pure sport: Practical sport psychology . Routledge.

- Kumar, P., & Shirotriya, A. K. (2010). ‘Sports psychology’ a crucial ingredient for athletes success: Conceptual view. British Journal of Sports Medicine , 44 (Suppl_1), i55–i56.

- Loehr, J., & Schwartz, T. (2018). The making of a corporate athlete. In HBR’s 10 must reads: On mental toughness . Harvard Business Review Press.

- Meijen, C. (2019). Endurance performance in sport: Psychological theory and interventions . Routledge.

- Moran, A. P. (2012). Sport and exercise psychology: A critical introduction . Psychology Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness . Guilford Press.

- Sheard, M. (2013). Mental toughness: The mindset behind sporting achievement . Routledge.

- Sutton, J. (2019). Psychological and physiological factors that affect success in ultra-marathoners (Doctoral thesis, Ulster University). Retrieved from https://pure.ulster.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/psychological-and-physiological-factors-that-affect-success-in-ul

- Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. The American Journal of Psychology , 9 (4), 507–533.

- Whyte, G. P. (2015). Achieve the impossible: How to overcome challenges and gain success in life, work and sport . Bantam Press.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Hello, my name is Ali, and I have a question about something. I graduated last year from the Faculty of Physical Education in my country, Egypt, Helwan University, and I got a bachelor’s degree with excellent grades. I was majoring in sports psychology. I am really interested and very passionate about this field. The articles I read helped me in fact. On this site about this specialization, it increases my desire to stick to work in this field, but I am currently facing a problem, which is I do not know where to start specifically, should I complete postgraduate academic studies in this specialty until I get at least a master’s degree in order to work in clubs As a sports psychologist? Or do I apply directly to one of the clubs and ask to work as a sports psychologist in it? And with which team, in particular, or in what sport? What are the required conditions and qualifications that allow me to work in this field? What are the types of books that I should read in order to improve my cognitive, scientific and applied skills in this field? Thank you very much

Yes, if you want to become a registered psychologist in any discipline, you will need to complete a Master’s degree. You’ll need to do this before you can work as a psychologist in the field. You can learn more about the process in this article , and also in our digital guidebook on becoming a therapist (which also covers what’s involved in becoming a psychologist).

We also have a dedicated blog post full of sport psychology book recommendations here . I imagine once you’ve gone through a sports psychology Master’s program and done further reading, you may discover which specific sports and teams you are most likely to enjoy working with — ultimately that decision is up to you!

Hope these materials help.

– Nicole | Community Manager

Do you think this translates to a 1:1 with digital athletes (like in esports)? Or do you think the physical athlete’s connection with physical exercise during competition may change the way this type of anxiety is dealtwith?

That’s a great question! I can’t give you a clear answer as research in this space is still very much new and emerging. However, at face value, I think many of the components here do equally apply to esports. For instance, it is just as important to set effective goals and manage anxiety/arousal in esports as it is in traditional sports.

As you note, however, mechanisms for effective goal-setting, management of anxiety, etc. may be different from traditional sports, as they may not rely on the mind-body connection in the same way, or draw more on cognitive resources and capabilities.

For a review that sets the stage for research in this space, definitely check out Pedraza-Ramirez et al. (2020) .

Hope this helps a little!

Hi am a Nigerian students of physical and health education my question is what are d criteria to work as a physiotherapist after study physical and health education

Hi Abigial,

The laws re: practicing as a physiotherapist will vary depending on country and state, so could you please let me know where you were hoping to practice? Then I can point you in the direction of some advice.

How can we use sports psychology to motivate people to get moving again outside, especially because of Covid-19? Can the answer/s also encourage society to create new gender neutral sports that keeps players separate without hands or head touching shared equipment? Can the lack of exercise be a big contributing factor why some students are not doing so well with Covid-19 forced remote learning?

Sounds like this post inspired some big questions for you! And I’ve no doubt the nature of sports around the world is likely to change in the wake of the pandemic. Early thinking seems to suggest that the impact of COVID on people’s exercise habits (and flow-on effects to things like study and mental health) depends somewhat on people’s preferred sports. E.g., this article suggests that, due to the nature of restrictions, cyclists, runners, etc. are well catered for, but those used to doing other sports may not be. A search for ‘exercise covid’ in Google Scholar will reveal some other interesting and emerging research in this space if you’d like to read more.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Hierarchy of Needs: A 2024 Take on Maslow’s Findings

One of the most influential theories in human psychology that addresses our quest for wellbeing is Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. While Maslow’s theory of [...]

Emotional Development in Childhood: 3 Theories Explained

We have all witnessed a sweet smile from a baby. That cute little gummy grin that makes us smile in return. Are babies born with [...]

Using Classical Conditioning for Treating Phobias & Disorders

Does the name Pavlov ring a bell? Classical conditioning, a psychological phenomenon first discovered by Ivan Pavlov in the late 19th century, has proven to [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Sports Psychology?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Frequently Asked Questions

Sports psychology is the study of how psychological factors influence sports, athletic performance, exercise, and physical activity. Sports psychologists investigate how participating in sports can improve health and well-being. They also help athletes utilize psychology to improve their athletic performance and mental wellness.

As an example, a sports psychologist working with Michael Jordan, Shaquille O'Neal, and Kobe Bryant helps these athletes perform better on the basketball court by teaching them psychological techniques for "being in the flow" and getting in "the zone."

A sports psychologist doesn't just work with elite and professional athletes either. This type of professional also helps non-athletes and everyday exercisers learn how to enjoy sports and stick to an exercise program. They utilize exercise and athletics to enhance people’s lives and mental well-being .

History of Sports Psychology

Sports psychology is a relatively young discipline in psychology ; the first research lab devoted to the topic opened in 1925. The first U.S. lab closed a short while later (in the early 1930s) and American research did not resume in this area until the late 1960s when there was a revival of interest.

In 1965, the International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP) was established. By the 1970s, sports psychology had been introduced as a university course offered at educational institutions throughout North America.

By the 1980s, sports psychology became the subject of a more rigorous scientific focus. Researchers began to explore how psychology could be used to improve athletic performance. They also looked at how exercise could be utilized to improve mood and lower stress levels .

Types of Sports Psychologists

Just as there are different types of psychologists —such as clinical psychologists, developmental psychologists, and forensic psychologists—there are also different types of sports psychologists.

Educational Sports Psychologists

An educational sports psychologist uses psychological methods to help athletes improve sports performance. This includes teaching them how to use certain techniques such as imagery , goal setting , or self talk to perform better on the court or field.

Clinical Sports Psychologists

Clinical sports psychologists work with athletes who have mental health conditions such as depression or anxiety . This work involves using strategies from both sports psychology and psychotherapy . A clinical sports psychologist helps athletes improve their mental health and sports performance at the same time.

Exercise Psychologists

An exercise psychologist works with non-athlete clients or everyday exercisers to help them learn how to make working out a habit. This work can include some of the same techniques used by other sports psychologists, such as goal setting, practicing mindfulness , and the use of motivational techniques .

Uses of Sports Psychology

Contemporary sports psychology is a diverse field and there are a number of different topics that are of special interest to sports psychologists. Here are a few areas of sports psychology and how they are utilized.

Attentional Focus

Attentional focus involves the ability to tune out distractions (such as a crowd of screaming fans) and focus on the task at hand. This allows athletes to manage their mental focus , even in the face of other things that are vying for their attention.

Common strategies that might be used for this purpose include deep breathing, paying attention to bodily signals and sensations, and mindfulness. All of these can help athletes stay focused on the present moment.

Mental Toughness

Mental toughness has become an area of increasing interest in sports psychology. The term refers to the psychological characteristics that are important for an athlete to reach optimal performance.

Among these characteristics are having an unshakeable belief in one's self , the ability to bounce back from setbacks , and an insatiable desire to succeed. Reacting to situations positively, remaining calm under pressure, and retaining control are a few others that contribute to mental toughness.

Visualization and Goal-Setting

Setting a goal, then visualizing each step needed to reach that goal can help mentally prepare the athlete for training or competition. Visualization involves creating a mental image of what you "intend" to happen. Athletes can use this skill to envision the outcome they are pursuing. They might visualize themselves winning an event, for instance, or going through the steps needed to complete a difficult movement.

Visualization can also be useful for helping athletes feel calmer and more focused before an event.

Motivation and Team-Building

Some sports psychologists work with professional athletes and coaches to improve performance by increasing motivation . A major subject in sports psychology, the study of motivation looks at both extrinsic and intrinsic motivators .

Extrinsic motivators are external rewards such as trophies, money, medals, or social recognition. Intrinsic motivators arise from within, such as a personal desire to win or the sense of pride that comes from performing a skill.

Team building is also an important topic in this field. Sports psychologists might work with coaches and athletes to help develop a sense of comradery and assist them in working together efficiently and effectively.

Professional sports psychologists help athletes cope with the intense pressure that comes from competition. This often involves finding ways to reduce performance anxiety and combat burnout.

It is common for athletes to get nervous before a game, performance, or competition. But these nerves can have a negative impact on performance. So, learning tactics to stay calm is important for helping athletes perform their best.

Tactics that might be the focus of this area of sports psychology include things like relaxation techniques , changing negative thoughts , building self-confidence , and findings distractions to reduce the focus on anxiety.

Burnout can also happen to athletes who frequently experience pressure, anxiety, and intense practice schedules. Helping athletes restore their sense of balance, learn to relax, and keep up their motivation can help combat feelings of burnout.

Rehabilitation

Another important focus of sports psychology is on helping athletes recover and return to their sport after an injury. A sports injury can lead to emotional reactions in addition to physical injury, which can include feelings of anger , frustration , hopelessness , and fear .

Sports psychologists work with these athletes to help them mentally cope with the recovery process and to restore their confidence once they are ready to return to their sport.

Impact of Sports Psychology

Research indicates that using various sports psychology techniques can help improve the performance of all types of athletes, from very young gymnasts (aged 8 to 13) to some of the top Olympians . Sports psychology also has impacts that extend into other areas of wellness.

For example, one study noted that it's common for doctors to have negative reactions when treating acutely unwell patients. Yet, when the doctors used the same psychological routines as athletes, they were able to better control these reactions. It also improved their patient care.

Others suggest that sports psychologists can play an important role in reducing obesity , particularly in children. By helping kids increase their physical activity and their enjoyment of the activity, a sports psychologist can help kids achieve and maintain a healthy weight.

Techniques in Sports Psychology

Some professionals use one specific technique when helping their clients while others use a wide range of sports psychology techniques.

Progressive Relaxation

Relaxation techniques offer athletes many benefits. Among them are an increase in self-confidence, better concentration, and lower levels of anxiety and stress—all of which work together to improve performance.

One of the relaxation strategies sports psychologists use with their clients is progressive muscle relaxation . This technique involves having them tense a group of muscles, hold them tense for a few seconds, then allow them to relax.

Some health professionals use hypnosis to help their patients quit smoking. A sports psychologist might use this same technique to help their clients perform better in their sport of choice.

Research indicates that hypnosis (which involves putting someone in a state of focused attention with increased suggestibility) can be used to improve performance for athletes participating in a variety of sports, from basketball to golf to soccer.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback involves using feedback provided by the body to notice how it feels physiologically in times of stress (elevated heart rate, tense muscles, etc.). This information can then be used to help control these effects, providing a more positive biological response.

One systematic review noted that using heart rate variability biofeedback improved sports performance in more than 85% of the studies. Other research supports using biofeedback to reduce an athlete's stress and anxiety.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is used to help all kinds of people identify and change destructive thoughts and behaviors. Therefore, it would only stand to reason that athletes would also benefit from its effects.

One case study involving a 17-year-old female cross-country skier noted that CBT helped reduce performance anxiety while improving sport-specific behaviors. Another piece of research involved 16 NCAA Division I athletes with severe injuries and found that CBT enhanced their emotional well-being during recovery.

Becoming a Sports Psychologist

Becoming a sports psychologist could be exciting for many psychology students, and it may be a good career choice for those with a strong interest in sports and physical activity.

The American Psychological Association (APA) describes sports psychology as a "hot career," suggesting that those working in university athletic departments earn around $60,000 to $80,000 per year.

If you are interested in this career, start by learning more about the educational requirements, job duties, salaries, and other considerations about careers in sports psychology .

A Word From Verywell

Sports psychology, or the use of psychological techniques in exercise and sports, offers benefits for athletes and non-athletes alike. It also encompasses a wide variety of techniques designed to boost performance and strengthen exercise adherence.

If you have a passion for sports and psychology, becoming a sports psychologist could be a good career choice. And it offers a few different career options, enabling you to choose the one that interests you most.

Sports psychology offers athletes many benefits, from improved performance to a healthier mental recovery after sustaining a physical injury. It can help these athletes stay engaged in the sports they love. Sports psychology also offers benefits for non-athletes, such as by helping them stick to an exercise program. Getting regular exercise improves brain health , reduces the risk of disease, strengthens bones and muscles, and makes it easier to maintain a healthy weight—while also increasing longevity.

Different sports psychology techniques work in different ways. Some are used to promote self-confidence. Others are designed to reduce anxiety. Though they all have one goal in common and that goal is to help the athlete improve their performance.

Sports psychologists can take a few different career paths. If you want to teach athletes how to improve their performance through psychological techniques, you can do this as an educational sports psychologist. If you want to work with athletes who have a mental illness, a clinical sports psychologist offers this service. If you want to work with the everyday exerciser versus athletes, becoming an exercise psychologist might be a good career choice for you.

A number of colleges and universities offer a sports psychology program. Some are undergraduate programs, offering a bachelor's degree in sports psychology. Others are higher-level programs, providing a master's degree or above. Depending on the educational institution, you may also be able to study sports psychology online.

In some cases, sports psychology improves performance by reducing anxiety. In others, it works by improving focus or increasing mental toughness. A sports psychologist can help uncover issues that might be limiting the athlete's performance. This information is then used to determine which psychological techniques can offer the best results.

Effron L. Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant's meditation coach on how to be 'flow ready' and get in the zone . ABC News .

American Psychological Association. Sports psychologists help professional and amateur athletes .

University of Michigan. Lecture 1: History of sports psychology .

International Society of Sports Psychology. ISSP mission .

American Psychological Association. Educational sport psychology .

American Psychological Association. A career in sport performance psychology .

Liew G, Kuan G, Chin N, Hashim H. Mental toughness in sport . German J Exerc Sport Res . 2019;49:381-94. doi:10.1007/s12662-019-00603-3

NCAA Sport Science Institute. Mind, body and sport: anxiety disorders .

National Athletic Trainers' Association. Burnout in athletes .

Mehdinezhad M, Rezaei A. The impact of normative feedback (positive and negative) on static and dynamic balance on gymnast children aged 8 to 13 . Sport Psychol . 2018;2(1):61-70.

Olympic Channel. Visualisation .

Church H, Murdoch-Eaton D, Sandars J. Using insights from sports psychology to improve recently qualified doctors' self-efficacy while managing acutely unwell patients . Academic Med . 2020;96(5):695-700. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003809

Morelli V, Davis C. The potential role of sports psychology in the obesity epidemic . Prim Care . 2013;40(2):507-23. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.001

Parnabas V, Mahamood Y, Parnabas J, Abdullah N. The relationship between relaxation techniques and sport performance . Universal J Psychol . 2014;2(3):108-112. doi:10.13180/ujp.2014.020302

Milling L, Randazzo E. Enhancing sports performance with hypnosis: An ode for Tiger Woods . Psychol of Consciousness: Theory Res Pract . 2016;3(1):45-60. doi:10.1037/cns0000055

Morgan S, Mora J. Effect of heart rate variability biofeedback on sport performance, a systematic review . App Psychophysiol Biofeed . 2017;42:235-45. doi:10.1007/s10484-017-9364-2

Dziembowska I, Izdebski P, Rasmus A, Brudny J, Grzelczak M, Cysewski P. Effects of heart rate variability biofeedback on EEG alpha asymmetry and anxiety symptoms in male athletes: A pilot study . App Psychophysiol Biofeed . 2015;41:141-150. doi:10.1007/s10484-015-9319-4

Gustafsson H, Lundqvist C, Tod D. Cognitive behavioral intervention in sport psychology: A case illustration of the exposure method with an elite athlete . J Sport Psychol Action . 2017;8(3):152-62. doi:10.1080/21520704.2016.1235649

Podlog L, Heil J, Burns R, et al. A cognitive behavioral intervention for college athletes with injuries . The Sport Psychol . 2020;34(2):111-21. doi:10.1123/tsp.2019-0112

Voelker R. Hot careers: Sport psychology . American Psychological Association. GradPSYCH Magazine.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical activity: Benefits of physical activity .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Christina DeBusk is a personal trainer and nutrition specialist.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ScreenShot2021-08-17at1.12.05PM-a64236e03c694b66b60a61d85ba3b023.png)

Introduction: Sport and Exercise Psychology—Theory and Application

- First Online: 26 February 2023

Cite this chapter

- Julia Schüler 5 ,

- Mirko Wegner 6 ,

- Henning Plessner 7 &

- Robert C. Eklund 8

2943 Accesses

1 Altmetric

The introduction to this textbook gives an overview of the scientific field of the psychology of sport and exercise. It is explained that sport psychologists try to describe, explain, predict, and change human experience and behavior in the area of physical activity. We display how sport psychology is concerned with phenomena in competitive rule-governed physical activities, while exercise psychology rather deals with health-related physical activity. We further show how one and the same phenomenon can be viewed from different theoretical perspectives in each subdiscipline of sport psychology, including cognition, motivation, emotion, personality, development, and social psychology. The present textbook is further divided into a theoretical and a practical part. However, we emphasize that both theory and practice in sport psychology are intertwined and influence each other strongly. Finally, we give a selective overview on the history of sport psychology and organization and institutionalization of the scientific subject of sport psychology.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bäumler, G. (2009). The dawn of sport psychology in Europe, 1880–1930. In C. D. Green & L. T. Benjamin (Eds.), Psychology gets in the game: Sport, mind, and behavior, 1880–1960 (pp. 20–77). University of Nebraska Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Carron, A. V., Brawley, L. R., & Widmeyer, W. N. (1998). The measurement of cohesiveness in sport groups. In J. L. Duda (Ed.), Advances in sport and exercise psychology measurement (pp. 213–226). Fitness Information Technology.

Google Scholar

de Coubertin, P. (1900). Psychologie du sport. Revue des Deux Mondes, 160 (4), 167–179.

Eklund, R. C., & Crocker, P. R. E. (2018). The nature of sport, exercise and physical activity psychology. In T. S. Horn & A. L. Smith (Eds.), Advances in sport psychology (4th ed., pp. 3–16). Human Kinetics.

Eklund, R. C., & Tenenbaum, G. (Eds.). (2014). Encyclopedia of sport and exercise psychology . Sage.

Gill, D. L., & Reifsteck, E. J. (2014). History of exercise psychology. In R. C. Eklund & G. Tenenbaum (Eds.), Encyclopedia of sport and exercise psychology (pp. 340–345). Sage.

Green, C. D. (2003). Psychology strikes out: Coleman r. Griffith and the chicago cubs. History of Psychology, 6 (3), 267–283.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Griffith, C. R. (1925). Psychology and its relation to athletic competition. American Physical Education Review, 30 , 193–199.

Article Google Scholar

Griffith, C. R. (1926). The psychology of coaching: A study of coaching methods from the point of psychology . Scribner’s.

Griffith, C. R. (1928). Psychology and athletics: A general survey for athletes and coaches . Scribner’s.

Kornspan, A. S. (2009). Fundamentals of sport and exercise psychology . Human Kinetic.

Book Google Scholar

Kornspan, A. S. (2012). History of sport and performance psychology. In S. M. Murphy (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of sport and performance psychology . Oxford University Press.

Landers, D. M. (1995). Sport psychology: The formative years, 1950–80. The Sport Psychologist, 9 , 406–419.

Lewin, K. (1951). Problems of research in social psychology. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers . Harper & Row.

Nitsch, J. R. (1978). Zur Lage der Sportpsychologie [State of sport psychology]. In J. R. Nitsch & H. Allmer (Hrsg.), Sportpsychologie—Eine Standortbestimmung (S. 1–11). Köln: bps.

Popper, K. (1935). Logik der Forschung: Zur Erkenntnistheorie der modernen Naturwissenschaft [Logic of research: On the epistemology of modern natural science] . Verlag Julius Springer.

Scripture, E. W. (1894). Tests of mental ability as exhibited in fencing. Studies from the Yale Psychological Laboratory, 2 , 122–124.

Seiler, R. (2018). 50 Jahre Sportpsychologie: Von Wegen und Umwegen (50 Years of sport psychology: Of paths and detours) . Senior Lecture at the 50th Annual Meeting of the German Society for Sport Psychology, May 10th, 2018, in Cologne.

Seiler, R., & Wylleman, P. (2009). FEPSAC’s role and position in the past and in the future of sport psychology in Europe. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10 , 403–409.

Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. The American Journal of Psychology, 9 (4), 507–533.

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). (1996). Physical activity and health: A report of the surgeon general . USDHHS.

Wiggins, D. K. (1984). The history of sport psychology in North America. In J. M. Silva & R. S. Weinberg (Eds.), Psychological foundations of sport (pp. 9–22). Human Kinetics.

Wuchty, S., Jones, J. F., & Uzzi, B. (2007). The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science, 316 , 1036–1039.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Konstanz, Constance, Germany

Julia Schüler

University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Mirko Wegner

Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany

Henning Plessner

Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA

Robert C. Eklund

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Julia Schüler .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Universität Konstanz, Constance, Germany

Ruprecht-Karls-University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Schüler, J., Wegner, M., Plessner, H., Eklund, R.C. (2023). Introduction: Sport and Exercise Psychology—Theory and Application. In: Schüler, J., Wegner, M., Plessner, H., Eklund, R.C. (eds) Sport and Exercise Psychology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-03921-8_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-03921-8_1

Published : 26 February 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-03920-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-03921-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Sport Psychology Services

- Professionals

- Sport Psychology Articles

- Preliminary Assessment

- Colleges & Degrees

- Mental Edge Athletics

What is Sport Psychology?

In 1897, an Indiana University psychologist, Dr. Norman Triplett, wrote what was considered the first scientific paper on sport psychology, on the social facilitation behavior of bicyclists.

In the early 1920’s, the first sport psychology laboratory was created in Berlin, Germany, by Dr. Carl Diem. Soon after, sport psychology arrived in America when Dr. Coleman R. Griffith created the first sport psychology laboratory in the U.S., in the state of Illinois. Dr. Griffith also created and taught the first university level courses in sport psychology at the University of Illinois, in 1923. In addition, Dr. Griffith was the first sport psychologist ever hired by a professional sports team, the Chicago Cubs baseball team. For his pioneering efforts, he is considered the father of the science of sport psychology in the United States.

We can define psychology as the study of the human mind, emotions and behavior. Psychology is an academic and applied field. The American Psychological Association (APA) states that sport psychology is the “scientific study of the psychological factors that are associated with participation and performance in sport, exercise, and other types of physical activity.” The most important certifying body in sport psychology, the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP), states that they “promote the ethical practice, science, and advocacy of sport and exercise psychology”.

Virtually every college, national, professional and Olympic sports team has a sports psychologist on staff, and countless individual college, Olympic and professional athletes work closely with sports psychology consultants. Look at a few of the big names in pro golf who have used sports psychology consultants. It’s estimated that well over 300 of the pro game’s players regularly use sports psychologists:

Do these 55 golf professionals convince you that sport psychology is a must to get the mental edge? They play golf for a living and want every edge possible. They are already strong mentally, but want to continue to improve and so seek the services of a sport psychologist. You can benefit too.

Let’s take a look at the field of sport psychology and discover how it can help you as an athlete, parent of an athlete, or as a coach. Here are ten areas that sport psychology studies, and how it applies this knowledge to sport learning and performance.

- Sport Psychology Helps You Understand Yourself As An Athlete. You need to have mental strategies for learning, practice and performance factors. Sport psychology gives you the methods and approaches to become aware of what you need so you and your coach can craft custom interventions.

- Sport Psychology Helps You Work Better With Your Parents. Your parents should be part of your success team, at least at some level. It does not necessarily mean they should coach you, but it would be nice to have a solid relationship with them, and excellent communication skills so they can assist you in your career.

- Sport Psychology Helps You Work Better With Your Coaches. Your coach is perhaps the most important person on your team. You need a great working relationship with this person. Sport psychology can help you create this relationship, and nurture it.

- Sport Psychology Helps You Navigate Your Sport Career. There are many blind alleys, pitfalls and false paths in a sport career. Sport psychology helps you create a vision for success, and goals and objectives, so you can execute that master plan.

- Sport Psychology Helps You Prepare Your Mind. It is critical that you know how to prepare mentally and emotionally for lessons, practices and performances. Sport psychology helps you devise a customized mental readiness process that helps you transition from your normal work, school or social worlds into the special world of competition.

- Sport Psychology Helps You Concentrate So You Can Enter The Zone. Attentional control is psychologist-speak for concentration or focus. Sport psychology helps you create strong control over where and how you place your attention so you can concentrate on the proper attentional cues, and you are able to block out unwanted, distracting cues.

- Sport Psychology Helps You Bounce Back From Set-Backs. It is critical that you become resilient to the inevitable problems and set-backs that competitive sport brings. You need solid mental toughness that helps you refocus, reset and re-energize for what is to come.

- Sport Psychology Helps You Increase Motivation And Drive. Successful athletes who have long careers fuel them with exciting goals, a vision for the legacy they want to leave, and dreams of how they want to play. Sport psychology helps you craft engaging goals that create positive energy within you, so you have huge amounts of drive and determination to achieve your potential.

- Sport Psychology Helps You Handle Stress and Pressure. One of the major ways sport psychology helps you is through stress reduction in learning and performance. While some stress is inevitable and natural, levels of stress that are excessive damage performance. Sport psychology helps you manage stress and turn it into success.

- Sport Psychology Helps You Handle The Paradox Of Success. An issue that every athlete faces at some time is the paradox of success. As you become more successful, there are more pressures and more distractions pulling at you. Sport psychology helps you address these, stay focused, and helps you continue to sustain your best performances.

Now that this article has provided you with the big picture about sport psychology, you can gain more information and perspective from these helpful links in the psychology of sport:

Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP) http://appliedsportpsych.org/

The International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP) http://www.issponline.org/

The European Federation of Sport Psychology (FEPSAC) http://www.fepsac.com/

The North American Society for the Psychology of Sport and Physical Activity http://www.naspspa.org/

International Society for Sports Psychiatry (ISSP) http://www.theissp.com/

Directory of Graduate Programs in Applied Sport Psychology http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/1885693109/atheltinsightheo

Whether you are interested in sport psychology from a coaching, athlete or parent perspective, I suggest you investigate this fascinating field more in depth. Sport psychology can help in so many ways, and it makes sense to get every advantage you can get.

About the author:

Bill Cole, MS, MA , a leading authority on peak performance, mental toughness and coaching, is founder and CEO of William B. Cole Consultants, a consulting firm that helps organizations and professionals achieve more success in business, life and sports.

hello could you please tell me some relif technique to me for relax mind.

Try to focus in the present moment rather then on previous performances or end results. Focus on your mental preparation (what you need to do before a competition to perform successfully) Keep your expectations in check by applying process goals (see articles on the formula for success and process goals) Listen to music and establish a routine that helps you relax your mind before games. During games let go of the last play and stay focused on what you need to do in the present moment to perform successfully. Try positive self-talk and positive affirmations. Eliminate irrelevant thoughts (things that will not help you perform) such as doubts, play your game!

Breath in for six seconds, hold for two seconds, breath our for 7 seconds..repeat this to slow heartrate and accept the fact that your choking when you are. and fix it.

Hello, i find myself i always recognized a person stopped at my web site therefore i arrived at gain this desire? . I am trying to find what you should develop my site! I guess its ample to utilize a number of ones principles!

Sport Psychology helps for more then just sports it, I have used that to get my self ready for big events in my life.

Leave a Reply

Mail (will not be published)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Sport Psychology Degree

Get your degree.

Find schools and get information on the program that’s right for you.

Powered by Campus Explorer

Peak Performance

Sports psychology today, follow us on twitter, free resource, sport psychology today disclaimer, important: this website is produced and managed by sport psychology and performance psychology experts..., the purpose of this website is to educate visitors on the mental skills needed to succeed in sports and competitive business today., as the leading link in sports psychology between practitioners, educators, and the sports community, we connect competent professionals with their prospective audience through publishing and professional marketing services., all articles, products, and programs are copyrighted to their respective owners, authors, or mental edge athletics., the mental edge athletics team respects the intellectual property rights of others and expects you to do the same., youth sports psychology, sports psychology research, sport psychology schools, as seen in….

© 2010-2019 All Rights Reserved Worldwide by Michael J Edger III MS, MGCP and Mental Edge Athletics, LLC - (267) 597-0584 - Sports Psychology, Sport Psychology, Sport Psychologists, Sport Performance, Sports Psychology Articles, Peak Performance, Youth Sports, Sports Training, Performance Enhancement, Education, Coaching, Mental Training, SITE BY YES! SOLUTIONS

What We’ve Learned Through Sports Psychology Research

Scientists are probing the head games that influence athletic performance, from coaching to coping with pressure

Tom Siegfried, Knowable Magazine

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3c/1c/3c1cf8e9-0694-438d-89ef-6ea678a8239e/sports-psychology-1600x1200_web.jpg)

Since the early years of this century, it has been commonplace for computerized analyses of athletic statistics to guide a baseball manager’s choice of pinch hitter, a football coach’s decision to punt or pass, or a basketball team’s debate over whether to trade a star player for a draft pick.

But many sports experts who actually watch the games know that the secret to success is not solely in computer databases, but also inside the players’ heads. So perhaps psychologists can offer as much insight into athletic achievement as statistics gurus do.

Sports psychology has, after all, been around a lot longer than computer analytics. Psychological studies of sports appeared as early as the late 19th century. During the 1970s and ’80s, sports psychology became a fertile research field. And within the last decade or so, sports psychology research has exploded as scientists have explored the nuances of everything from the pursuit of perfection to the harms of abusive coaching.

“Sport pervades cultures, continents and indeed many facets of daily life,” write Mark Beauchamp, Alan Kingstone and Nikos Ntoumanis, authors of an overview of sports psychology research in the 2023 Annual Review of Psychology .

Their review surveys findings from nearly 150 papers investigating various psychological influences on athletic performance and success. “This body of work sheds light on the diverse ways in which psychological processes contribute to athletic strivings,” the authors write. Such research has the potential not only to enhance athletic performance, they say, but also to provide insights into psychological influences on success in other realms, from education to the military. Psychological knowledge can aid competitive performance under pressure, help evaluate the benefit of pursuing perfection and assess the pluses and minuses of high self-confidence.

Confidence and choking

In sports, high self-confidence (technical term: elevated self-efficacy belief) is generally considered to be a plus. As baseball pitcher Nolan Ryan once said, “You have to have a lot of confidence to be successful in this game.” Many a baseball manager would agree that a batter who lacks confidence against a given pitcher is unlikely to get to first base.

And a lot of psychological research actually supports that view, suggesting that encouraging self-confidence is a beneficial strategy. Yet while confident athletes do seem to perform better than those afflicted with self-doubt, some studies hint that for a given player, excessive confidence can be detrimental. Artificially inflated confidence, unchecked by honest feedback, may cause players to “fail to allocate sufficient resources based on their overestimated sense of their capabilities,” Beauchamp and colleagues write. In other words, overconfidence may result in underachievement.

Other work shows that high confidence is usually most useful in the most challenging situations (such as attempting a 60-yard field goal), while not helping as much for simpler tasks (like kicking an extra point).

Of course, the ease of kicking either a long field goal or an extra point depends a lot on the stress of the situation. With time running out and the game on the line, a routine play can become an anxiety-inducing trial by fire. Psychological research, Beauchamp and co-authors report, has clearly established that athletes often exhibit “impaired performance under pressure-invoking situations” (technical term: “choking”).

In general, stress impairs not only the guidance of movements but also perceptual ability and decision-making. On the other hand, it’s also true that certain elite athletes perform best under high stress. “There is also insightful evidence that some of the most successful performers actually seek out, and thrive on, anxiety-invoking contexts offered by high-pressure sport,” the authors note. Just ask Michael Jordan or LeBron James.

Many studies have investigated the psychological coping strategies that athletes use to maintain focus and ignore distractions in high-pressure situations. One popular method is a technique known as the “quiet eye.” A basketball player attempting a free throw is typically more likely to make it by maintaining “a longer and steadier gaze” at the basket before shooting, studies have demonstrated.

“In a recent systematic review of interventions designed to alleviate so-called choking, quiet-eye training was identified as being among the most effective approaches,” Beauchamp and co-authors write.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/db/00/db007d50-eb78-4314-aff0-6be80d65ec0b/gettyimages-1946568854_web.jpg)

Another common stress-coping method is “self-talk,” in which players utter instructional or motivational phrases to themselves in order to boost performance. Saying “I can do it” or “I feel good” can self-motivate a marathon runner, for example. Saying “eye on the ball” might help a baseball batter get a hit.

Researchers have found moderate benefits of self-talk strategies for both novices and experienced athletes, Beauchamp and colleagues report. Various studies suggest that self-talk can increase confidence, enhance focus, control emotions and initiate effective actions.