- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- Image & Use Policy

- Translations

UC MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY

Understanding Evolution

Your one-stop source for information on evolution

- ES en Español

Mutations are changes in the information contained in genetic material. For most of life, this means a change in the sequence of DNA, the hereditary material of life. An organism’s DNA affects how it looks, how it behaves, its physiology — all aspects of its life. So a change in an organism’s DNA can cause changes in all aspects of its life.

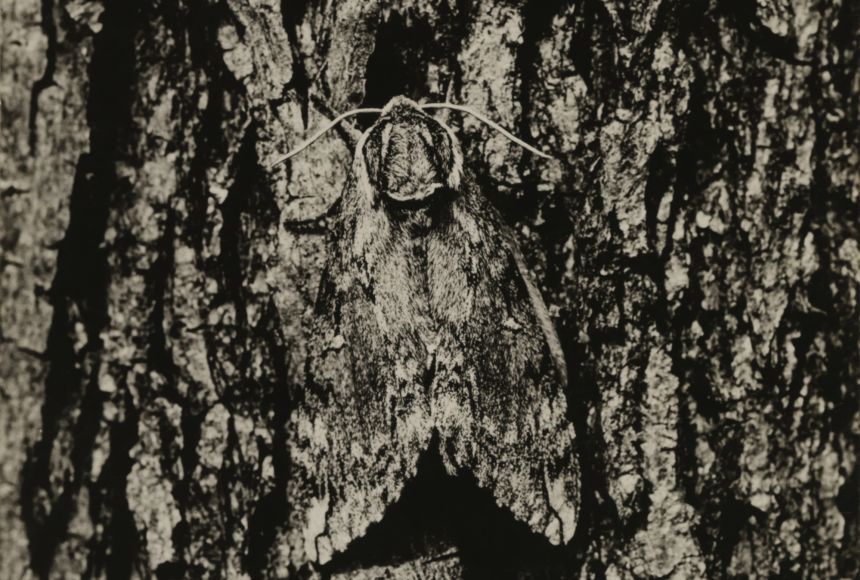

Mutations are random Mutations can be beneficial, neutral, or harmful for the organism, but mutations do not “try” to supply what the organism “needs.” In this respect, mutations are random — whether a particular mutation happens or not is unrelated to how useful that mutation would be.

Not all mutations matter to evolution Since all cells in our body contain DNA, there are lots of places for mutations to occur; however, not all mutations matter for evolution. Somatic mutations occur in non-reproductive cells and so won’t be passed on to offspring.

For example, the yellow color on half of a petal on this red tulip was caused by a somatic mutation. The seeds of the tulip do not carry the mutation. Cancer is also caused by somatic mutations that cause a particular cell lineage (e.g., in the breast or brain) to multiply out of control. Such mutations affect the individual carrying them but are not passed directly on to offspring.

The only mutations that matter for the evolution of life’s diversity are those that can be passed on to offspring. These occur in reproductive cells like eggs and sperm and are called germline mutations .

- More Details

- Evo Examples

- Teaching Resources

Read more about how mutations are random and the famous Lederberg experiment that demonstrated this. Or read more about how mutations factored into the history of evolutionary thought . Or dig into DNA and mutations in this primer.

Learn more about mutation in context:

- Evolution at the scene of the crime , a news brief with discussion questions.

- A chink in HIV's evolutionary armor , a news brief with discussion questions.

Find lessons, activities, videos, and articles that focus on mutation.

Reviewed and updated June, 2020.

Genetic variation

The effects of mutations

Subscribe to our newsletter

- Teaching resource database

- Correcting misconceptions

- Conceptual framework and NGSS alignment

- Image and use policy

- Evo in the News

- The Tree Room

- Browse learning resources

- Biology Article

- Mutation Genetic Change

Mutation - A Genetic Change

Mutation definition.

“Mutation is the change in our DNA base pair sequence due to various environmental factors such as UV light, or mistakes during DNA replication.”

Table of Contents

Classification & types of mutations, frequently asked questions, what are mutations.

The DNA sequence is specific to each organism. It can sometimes undergo changes in its base-pairs sequence. It is termed as a mutation. A mutation may lead to changes in proteins translated by the DNA. Usually, the cells can recognize any damage caused by mutation and repair it before it becomes permanent.

A mutation is a sudden, heritable modification in an organism’s traits. The term “mutant” refers to a person who exhibits these heritable alterations. Mutations usually produce recessive genes.

Causes of Mutations

The mutation leads to genetic variations among species. Positive mutations are transferred to successive generations.

E.g. Mutation in the gene coding for haemoglobin causes sickle cell anaemia. The R.B.Cs become sickle in shape. However, in the African population, this mutation provides protection against malaria.

A mutation in the gene controlling the cell division leads to cancer.

Let us have an overview of the causes and impacts of mutation.

Also Read: Mutagens

The mutation is caused due to the following reasons:

Internal Causes

Most of the mutations occur when the DNA fails to copy accurately. All these mutations lead to evolution. During cell division , the DNA makes a copy of its own. Sometimes, the copy of the DNA is not perfect and this slight difference from the original DNA is called a mutation.

External Causes

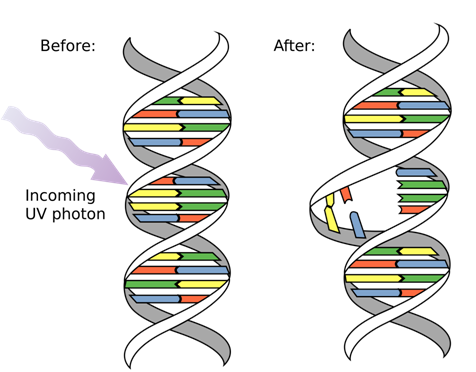

When the DNA is exposed to certain chemicals or radiations, it causes the DNA to break down. The ultraviolet radiations cause the thymine dimers to break resulting in a mutated DNA.

DNA Mutation

Effects of Mutation

There are several mutations that cannot be passed on to the offsprings. Such mutations occur in the somatic cells and are known as somatic mutations.

The germline mutations can be passed on to successive generations and occur in the reproductive cells.

Let us have a look at some of the effects of mutation:

Beneficial Effects of Mutation

- Few mutations result in new versions of proteins and help the organisms to adapt to changes in the environment. Such mutations lead to evolution.

- Mutations in many bacteria result in antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria that can survive in the presence of antibiotics.

- A unique mutation found in the population of Italy protects them from atherosclerosis, where fatty materials build up in the blood vessels.

Effects of Mutations

- Genetic disorders can be caused by the mutation of one or more genes. Cystic fibrosis is one such genetic disorder caused by the mutation in one or more genes.

- Cancer is another disease caused by the mutation in genes that regulate the cell cycle.

For more information on mutation, its causes and effects, keep visiting BYJU’S website or download BYJU’S app for further reference.

Give the meaning of mutation.

Mutation means an alteration in the genes or chromosomes of a cell. This shift in the gametes may impact the development and structure of the progeny. A mutation in biology is a modification of the nucleic acid sequence of a virus, extrachromosomal DNA, or the genome of an organism. The observable traits of an organism (phenotype) may or may not change as a result of a mutation.

Define gene mutation. Give examples.

Gene or genetic mutations are modifications to the DNA sequence that take place as the cells divide and generate copies of themselves. The DNA provides instructions on how to develop and run the human body. Genetic changes may result in diseases like cancer or, in the long run, enable people to adapt to their surroundings more successfully.

Examples include animals possessing extra body parts after birth, such as four-legged ducks, cyclops kittens, and snakes with two heads. Genetic disorders in humans, like Sickle-cell disease, are frequently brought on by gene mutations or chromosomal aberrations. Angelman syndrome, Canavan disease, colour blindness, cystic fibrosis, cri-du-chat syndrome, Down syndrome, haemophilia, Klinefelter syndrome, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, phenylketonuria, Prader-Willi syndrome, Tay-Sachs disease, and Turner syndrome are additional examples of common mutations in human beings.

What is DNA mutation?

A DNA mutation is a long-lasting alteration to the nucleotide sequence of DNA that can occur during replication and recombination. Most of the time, mutations are benign unless they result in tumour growth or cell death. Base pair substitution, deletion, or insertion can all result in mutations in damaged DNA. Cells have developed processes for repairing damaged DNA owing to the deadly consequences of DNA mutations.

Base substitutions, deletions, and insertions are the three different forms of DNA mutations.

What are the causes of gene mutation?

A gene mutation is a permanent change to a DNA sequence that makes it different from the sequence found in other people. A genetic mutation occurs during cell division when the grow and divide and replicate. Mutations can impact anything from a single DNA base pair (a unit of genetic composition) to a significant portion of a chromosome that contains numerous genes.

How does mutation affect genetic change?

A population can acquire new alleles through mutations, increasing the genetic diversity of the population. For mutations to impact an organism’s offspring, they must: 1) arise in cells that give rise to the succeeding generation; and 2) alter the genetic code. Diversity among organisms is ultimately produced through the interaction of hereditary mutations and environmental stresses.

Put your understanding of this concept to test by answering a few MCQs. Click ‘Start Quiz’ to begin!

Select the correct answer and click on the “Finish” button Check your score and answers at the end of the quiz

Visit BYJU’S for all Biology related queries and study materials

Your result is as below

Request OTP on Voice Call

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post My Comment

Superbb explanation

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Middle school biology

Course: middle school biology > unit 7.

- Apply: mutations

Key points:

- A mutation is any change to the nucleotide sequence of a DNA molecule. Some mutations arise as DNA is copied. Others are due to environmental factors.

- A mutation in a gene can change the structure and function of the protein encoded by that gene. This, in turn, can affect an organism’s traits.

- Harmful mutations have negative effects on an organism’s health and survival. For example, some mutations cause inherited disorders such as sickle cell anemia and cystic fibrosis.

- Beneficial mutations have positive effects on an organism’s health and survival. For example, some people have mutations that lower their risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

- Neutral mutations have no observable effect on an organism’s traits. For example, some gene mutations do not lead to amino acid changes, and so do not affect protein function.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Previous Article

Cover Image

Introduction, the human genome and variation, chromosome structure and chromosomal disorders, the sex chromosomes, x and y, single-gene disorders, mitochondrial disorders, epigenetics, complex disorders, cancer: mutation and epigenetics, genetic testing in the diagnostic laboratory, diagnosis, management and therapy of genetic disease, challenges in delivering a genetics service, competing interests, author contribution, appendix. glossary of terms, abbreviations, further reading: the human genome and variation, the genetic basis of disease.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

Maria Jackson , Leah Marks , Gerhard H.W. May , Joanna B. Wilson; The genetic basis of disease. Essays Biochem 3 December 2018; 62 (5): 643–723. doi: https://doi.org/10.1042/EBC20170053

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Genetics plays a role, to a greater or lesser extent, in all diseases. Variations in our DNA and differences in how that DNA functions (alone or in combinations), alongside the environment (which encompasses lifestyle), contribute to disease processes. This review explores the genetic basis of human disease, including single gene disorders, chromosomal imbalances, epigenetics, cancer and complex disorders, and considers how our understanding and technological advances can be applied to provision of appropriate diagnosis, management and therapy for patients.

When most people consider the genetic basis of disease, they might think about the rare, single gene disorders, such as cystic fibrosis (CF), phenylketonuria or haemophilia, or perhaps even cancers with a clear heritable component (for example, inherited predisposition to breast cancer). However, although genetic disorders are individually rare, they account for approximately 80% of rare disorders, of which there are several thousand. The sheer number of rare disorders means that, collectively, approximately 1 in 17 individuals are affected by them. Moreover, our genetic constitution plays a role, to a greater or lesser extent, in all disease processes, including common disorders, as a consequence of the multitude of differences in our DNA. Some of these differences, alone or in combinations, might render an individual more susceptible to one disorder (for example, a type of cancer), but could render the same individual less susceptible to develop an unrelated disorder (for example, diabetes). The environment (including lifestyle) plays a significant role in many conditions (for example, diet and exercise in relation to diabetes), but our cellular and bodily responses to the environment may differ according to our DNA. The genetics of the immune system, with enormous variation across the population, determines our response to infection by pathogens. Furthermore, most cancers result from an accumulation of genetic changes that occur through the lifetime of an individual, which may be influenced by environmental factors. Clearly, understanding genetics and the genome as a whole and its variation in the human population, are integral to understanding disease processes and this understanding provides the foundation for curative therapies, beneficial treatments and preventative measures.

With so many genetic disorders, it is impossible to include more than a few examples within this review, to illustrate the principles. For further information on specific conditions, there are a number of searchable internet resources that provide a wealth of reliable detail. These include Genetics Home Reference ( https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/ ), Gene Reviews ( https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1116/ ), the ‘Education’ section from the National Human Genome Research Institute ( https://www.genome.gov/education/ ) and Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man ( https://www.omim.org/ ). In this review, an understanding and knowledge of basic principles and techniques in molecular biology, such as the structure of DNA and the PCR will be assumed, but explanations and animations of PCR (and some other processes) are available from the DNA Learning Center ( https://www.dnalc.org/resources/ ). The focus here will be on human disease, although much of the research that defines our understanding comes from the study of animal models that share similar or related genes.

The human genome and the human genome reference sequence

The complete instructions for generating a human are encoded in the DNA present in our cells: the human genome, comprising roughly 3 billion bp of DNA. Scientists from across the world collaborated in the ‘Human Genome Project’ to generate the first DNA sequence of the entire human genome (published in 2001), with many additions and corrections made in the following years. Genome sequence information for humans and many other species is freely accessible through a number of portals, including the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ ) and Ensembl ( http://www.ensembl.org/ ), which also provide a wealth of related information.

The majority of our DNA is present within the nucleus as chromosomes (the nuclear DNA or nuclear genome), but there is also a small amount of DNA in the mitochondria (the mtDNA or mitochondrial genome). Most individuals possess 23 pairs of chromosomes ( Figure 2 ), therefore much of the DNA content is present in two copies, one from our mother and one from our father.

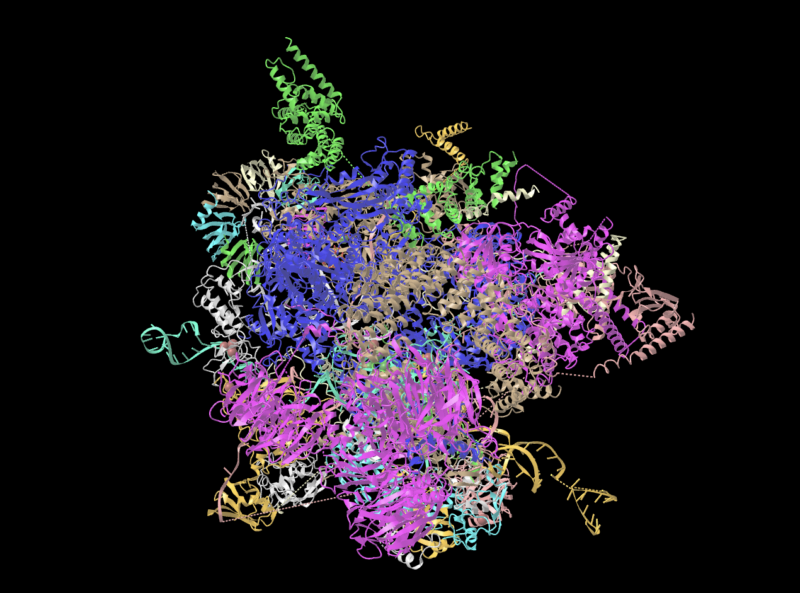

The human nuclear genome encodes roughly 20000 protein-coding genes, which typically consists of both protein-coding (exon) and non-coding (intron) sequences. Our genome also contains roughly 22000 genes that encode RNA molecules only; some of these RNAs form components of the translation machinery (rRNA, tRNA) but there are many more that perform various roles within the cell, including regulation of expression of other genes. In fact it is now believed that as much as 80% of our genome has biological activity that may influence structure and function. The human genome also contains over 14000 ‘pseudogenes’; these are imperfect copies of protein-coding genes that have lost the ability to code for protein. Although originally considered as evolutionary relics, there is now evidence that some may be involved in regulating their protein-coding relatives, and in fact dysregulation of pseudogene-encoded transcripts has been reported in cancer. Additionally, sequence similarity between a pseudogene and its normal counterpart may promote recombination events which inactivate the normal copy, as seen in some cases of perinatal lethal Gaucher disease. Furthermore, some pseudogenes have the potential to be harnessed in gene therapy to generate functional genes by gene editing approaches. The distribution of genes between chromosomes is not equal: chromosome 19 is particularly gene-dense, while the autosomes for which trisomy is viable (13, 18, 21) are relatively gene-poor ( Table 1 ).

Note that although these numbers seem very precise they should be taken as indicative only, since (i) chromosomes of each individual will vary from the reference sequence, and (ii) the human reference genome sequence is continuously updated with corrections (the data here are from GRCh38.p12, which represents a particular ‘build’ of the human genome). Note that the data for the acrocentric chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21, 22 does not include the shared ribosomal DNA array repeats present on the p arms (see Figure 2 ). Data from Ensembl, June 2018.

From the very beginning of the Human Genome Project, it was recognised that there was a huge amount of DNA sequence variation between healthy individuals, and therefore there is no such thing as a ‘normal’ human DNA sequence. However, if we are to describe changes to the DNA sequence, we need to describe these changes with respect to some baseline; this baseline is the human reference genome sequence.

Variation versus mutation

A geneticist’s definition of mutation is ‘any heritable change to the DNA sequence’, where heritable refers to both somatic cell division (the proliferation of cells in tissues) and germline inheritance (from parent to child). Such changes to the DNA may have no consequences but sometimes lead to observable differences in the individual (the ‘phenotype’). Consequently, in the past such alterations in the human population, particularly when they were associated with a disease state, were referred to as ‘mutations’. However, for many people this terminology has negative connotations, and brings to mind the ‘mutants’ seen in science fiction and zombie films! Therefore modern practice, particularly for medical genetics within the context of a health service, is to refer to differences from the reference sequence as ‘variants’. Variants may be further classified as benign (not associated with disease) or pathogenic (associated with disease), although there are increasing numbers of human DNA variants identified for which we are still not sure of the effect; these are termed ‘variants of uncertain significance’ or VUS ( Table 2 ).

Although this system was designed for classification of variants in relation to a potential role in cancer predisposition, it can also be used to classify variants in other situations.

Where two (or more) different versions of a DNA sequence exist in the population, these are referred to as ‘alleles’: each allele represents one particular version (or variant) of that sequence. By analysing many human genomes we can calculate the frequency at which a particular variant occurs in the population, often expressed as the ‘minor allele frequency’ or MAF. Where the MAF is at least 1%, a variant can be called a ‘polymorphism’, although this is a fairly arbitrary cut-off.

Single nucleotide variants: The most frequent variants in our genome are substitutions that affect only one base pair (bp), referred to as single nucleotide variants (SNV) or as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) ( Figure 1 ) depending upon the MAF. It has been estimated that there are at least 11 million SNPs in the human genome (averaging approximately 1 per 300 bp). It also seems likely that if we sequenced the genomes of everyone on the planet, for most positions in our genome we would discover at least one individual with an SNV, wherever such variation is compatible with life.

Some types of variants found in human genomes

Variation involving one or a few nucleotides are shown above the chromosome icon, and structural variants below; in each case the variants are depicted in relation to the reference sequence. For depiction of structural variants A, B, C and D represent large segments of DNA; Y and Z represent segments of DNA from a different chromosome. Note that differentiation between CNVs and deletions/insertions depends upon the size of the relevant DNA segment (see text for further details). Abbreviation: CNV, copy number variant. Chromosome ideogram from NCBI Genome Decoration Page.

Insertions and deletions (indels): Insertions or deletions of less than 1000 bp are also relatively common in the human genome, with the smallest indels being the most numerous.

Structural variants: Structural variants are defined as variants affecting segments of DNA greater than 1000 bp (1 kb). They include translocations, inversions, large deletions and copy number variants (CNV). CNVs are segments of our genome that range in size from 1000 to millions of bp, and which, in healthy individuals, may vary in copy number from zero to several copies ( Figure 1 ). By analysis of many human genomes it is apparent that CNV exists for approximately 12% of the human genome sequence. The largest CNVs may contain several entire genes. Where the population frequency of a CNV reaches 1% or more, it may be referred to as a copy number polymorphism (CNP).

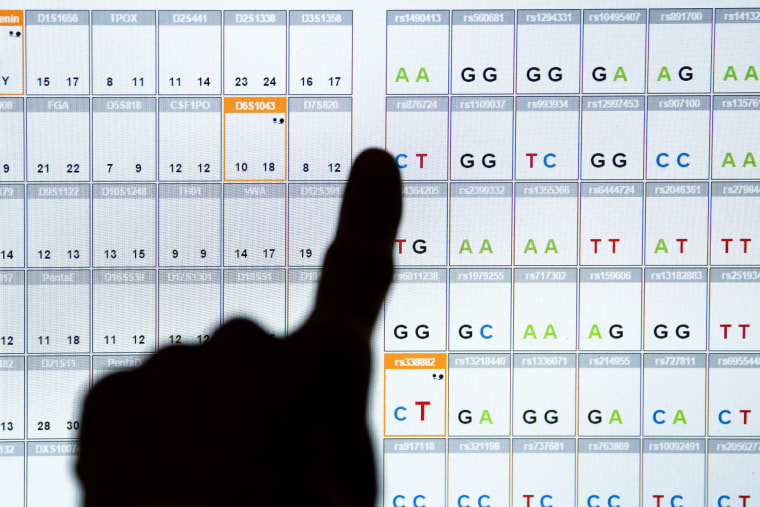

Repeat variations: Human genomes contain large numbers of repetitive sequences. These include ‘interspersed repeats’ which constitute approximately 45% of our genome, and represent remnants of mobile DNA elements (transposons). There are also several classes of ‘tandem repeats’, in which the repeated units are side-by-side in a head-to-tail fashion forming arrays of repeats of the same (or very similar) sequence. The number of repeats in each array can vary, generating multiple alleles, so that these loci have high variability within the population, and can be used in identifying individuals (see below). Tandem repeats include minisatellites and microsatellites ( Figure 1 / Table 3 ). Although generally inherited stably (i.e. with the same number of repeats) from parent to child, expansions in some microsatellites are associated with disease.

Note that repeats with unit lengths of 7–9 bp may be classified as micro- or minisatellites depending on their biological behaviour.

Many (but not all) authors include mononucleotide repeats in the category of microsatellites.

Variation between healthy individuals

Given that no two individuals look exactly alike (apart from identical twins) it will come as no surprise that this is reflected in our DNA. What is surprising is the amount of variation between us. Looking at any one human genome, compared with the reference sequence, we would find approximately 3 million SNPs, and approximately 2000 structural variants. The genomes of any two unrelated individuals will differ in approximately 0.5% of their DNA (approximately 15 million bp), and most of this variation can be attributed to CNVs and large deletions. Although much of the variation in our genome lies within the non-coding DNA, we now know that, on average, each individual has several hundred variants that are either known, or predicted, to be damaging to gene function, including roughly 85 variants that lead to truncated (incomplete) protein products. Furthermore, the total number of functional genes per human genome may vary by up to 10% between individuals as a consequence of CNVs, large deletions and loss-of-function variants. Faced with this enormous level of variation you might wonder, not why some individuals are affected by disease due to inherited ‘mutations’, but rather how any of us manage to remain relatively healthy! Clearly there is no requirement for all of our genes to be functional: for many genes only one working copy is required, and in other cases there appears to be a level of redundancy or plasticity built into the system. However it is becoming increasingly apparent that some of the variations in our genomes may lead to higher susceptibility to common diseases.

Variation between populations

The greatest amount of variation is found within populations of African ancestry, which is consistent with initial migration out of Africa, with each group of migrants taking subsets of variants with them. Common variants tend to be shared between all populations, whereas rare variants are more likely to be specific to particular populations or related populations. Some of the differences will be related to environmental adaptation, for example skin pigmentation or enzymes to detoxify dietary plant toxins. These same enzymes are also responsible for the metabolism of many pharmaceutical (and recreational) drugs; genetic variants may lead to some individuals being ultrarapid metabolisers or poor metabolisers, which may translate into poor drug response or adverse side effects. For example, deficiency in dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, leading to a toxic response to the cancer treatment 5-fluorouracil, is two to three times more common in African-American populations than in Caucasians.

DNA profiling

In the early 1980s, with the discovery of minisatellites, which are highly variable within the population but inherited stably from parent to child, it became possible to use these in forensic analyses and paternity testing, to generate unique patterns (similar to supermarket barcodes) for each individual, a technique referred to as ‘DNA fingerprinting’. This technology needed large amounts of sample (micrograms of DNA) and tended to be time-consuming (1–2 weeks) in addition to requiring use of radioactive labels. Towards the end of the 1980s, microsatellites were first reported and since these could be analysed with simple and rapid PCR-based assays, needing only approximately 1 nanogram of sample DNA, ‘DNA profiling’ using microsatellites quickly replaced the earlier DNA fingerprinting approach. Forensic DNA profiling in the U.K. currently analyses 16 microsatellites from across the genome, together with a region from the amelogenin gene present on both X and Y chromosomes that is 4 bp different in size between them, allowing gender identification. The process is similar to QF-PCR for prenatal aneuploidy testing, which will be discussed later. Finding a perfect match between the two samples (e.g. from crime scene and suspect) strongly suggests that these came from the same individual – the likelihood of finding a perfect match between samples from two different individuals is estimated at 1 in a billion – unless of course they are identical twins. On the other hand, if the two samples do not match, it can be concluded that the crime scene sample was not from the suspect. Likewise, in paternity testing, DNA profiling can exclude a man as the father of a child, but cannot prove he is the father with absolute certainty. DNA profiling is also useful in helping to identify human remains, for example where decomposition makes physical identification difficult. The fact that certain variants (including microsatellite alleles) are more frequently found in populations of particular ancestry means that the capability already exists to make some inferences on likely ancestral origin based on only a DNA sample and research is underway to establish whether particular features (for example, eye colour, hair colour and even facial characteristics) can be predicted from DNA. Thus the DNA profiling of the future may generate an identikit image of a wanted individual.

De novo mutations and mosaicism

Most of the variants in our genome were inherited from one of our parents. However, our DNA is constantly bombarded with DNA damaging agents and furthermore every time a cell’s DNA is replicated prior to division there is opportunity for errors. Genomic sequencing of trios (child plus both parents) has demonstrated that on average each individual has 74 de novo SNVs that were not present in either parent, in addition to approximately three de novo insertions/deletions. Approximately 1–2% of children will have a de novo CNV greater than 100 kb in size. Microsatellites have a relatively high mutation frequency, with gain or loss of a repeat unit occurring in roughly 1 per 1000 microsatellites per gamete per generation. In contrast with aneuploidy, which is most often a consequence of meiotic error during oocyte generation, new mutations are almost four times more common in the male germline than the female germline, which is likely to relate to the high number of cell divisions during spermatogenesis. For both sexes the new mutation rate increases with age, though again, the increase is more marked in the male germline. Most new mutations will have little or no effect on health, particularly those outside coding sequences, but some are associated with disease.

If a new mutation occurs during embryogenesis or development this can lead to mosaicism, where some cells in the individual have that new variant while others do not. Mosaicism for a new mutation may also be present in the gonads (‘gonadal mosaicism’), such that a new variant may be transmitted to less than 50% of the offspring, depending upon the percentage of gonadal cells in which the new variant is present. New mutations occurring during embryogenesis and development also generate a few differences between the genomes of identical twins.

Very rarely fusion of two embryos will generate a chimera: an individual that has two genetically distinct cell lines present. Where the same sex chromosome constitution is present in both cell lines chimerism might only come to light with the observation of apparent non-maternity or non-paternity amongst offspring (where one cell line predominates in the gonads and the other predominates in blood cells). Fusion of two embryos of different sex can lead to characteristics of both genders being present, and chimerism is found in approximately 13% of cases of hermaphroditism.

The massive amount of variation between individual human genomes can make it very difficult to determine which variants are benign and which might be associated with a disease. Even where a disease-associated variant is present, this will be present within a genomic context of millions of other differences from the ‘reference’ sequence, some of which may impact upon the severity of that disease in the individual. Thus it will become increasingly common to investigate wider genomic influences when considering contribution of variants to disease. Note that several scientific conventions are used when referring to chromosomes, genes, proteins and variants affecting them; these ensure unambiguous communication between scientists and health professionals. International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN) is used for describing karyotypes and changes at the chromosomal level. Individual loci and genes, for which there are often multiple different historical names, have now been assigned specific unique names by the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGCN) ( https://www.genenames.org/ ). Sequence variants are described according to Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) guidelines ( http://varnomen.hgvs.org/ ) for both DNA and proteins. Finally, since the same names are applied to genes and the proteins they encode, italics are used to refer to the gene, with standard font used when referring to the protein.

Almost every human cell contains a full diploid genome, consisting of 2 metres of DNA arranged into 46 chromosomes: 22 homologous autosomal pairs, and the sex chromosomes comprising two X chromosomes in females and an X and a Y in males. The exceptions are anucleate cells like erythrocytes (red blood cells), cell fragments (platelets) and haploid germline cells (sperm and eggs) which contain 23 chromosomes. Although mechanisms have evolved which ensure that during cell division, daughter cells will inherit a complete genome, those mechanisms occasionally make mistakes. This can lead to cells with chromosomal abnormalities, which can be categorised as numerical abnormalities, i.e. the resulting daughter cell contains too many or too few chromosomes, or structural abnormalities, where more complex rearrangements of the genome have taken place.

The normal chromosome complement of a species (i.e. the number, size and shape of chromosomes) is called its karyotype. According to the ISCN, the ‘normal’ human karyotype is denoted by either 46,XX (female) or 46,XY (male). Human chromosomes consist of DNA which is wrapped around a core of histone proteins to form chromatin. Most of the time, chromatin exists in a diffuse form within a cell’s nucleus, however, during metaphase of the cell division cycle, the chromosomes condense. It is these condensed chromosomes which can be stained with a variety of chemicals, and which can then be observed under a light microscope, to reveal the characteristic banding patterns. The bands reflect regions of chromatin with different characteristics, and therefore different functional elements. A photographic representation of a person’s metaphase chromosomes, arranged by size, may be referred to as a karyogram or karyotype ( Figure 2 A,B) and a graphical representation is called an ideogram ( Figure 2 C). The available stains for chromosomes differ in their chemical properties and consequently in the resulting banding pattern. The most commonly used stain is called Giemsa after the chemist who developed it in 1904; the resulting banding pattern of chromosomes is referred to as G-banding. The microscopic analysis of stained chromosomes is termed cytogenetics. Depending on the quality of the chromosome preparation, trained cytogeneticists can identify abnormalities with a resolution of approximately 3–4 Mb (millions of bp), however, abnormalities below this resolution threshold cannot be identified using conventional cytogenetics and require alternative, molecular techniques (see section ‘Genetic testing in the diagnostic laboratory’).

Giemsa banding (G-banding) to form a karyogram

( A ) Metaphase spreads like this are obtained from cultured cells arrested in metaphase using colcemid, followed by Giemsa staining to create characteristic light and dark bands. Generally the dark bands represent regions which are AT-rich and gene-poor. ( B ) The chromosomes from the spread are arranged in pairs to view the karyotype, often using specialist software like Cytovision. ( C ) Diagrammatic representations of the G-banding patterns, called ideograms, are used as a reference. The ideograms have been aligned at the centromere (dotted line); blue shaded regions are highly variable – note for example the variation between p arms of chromosome 13, 14 and 15 in (B). In fact the p arms of the acrocentric chromosomes (13, 14, 15, 21, 22) all have very similar content, which includes the nucleolar organiser regions or NORs. Each NOR contains a tandem repeat of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) which encodes the rRNAs. Between all five acrocentrics there are approximately 300–400 rDNA repeats, though the actual number varies between individuals. Chromosome ideograms from NCBI Genome Decoration Page.

When viewing condensed metaphase chromosomes under a microscope, some key features can be identified ( Figure 3 ). All mammalian chromosomes have a centromere, which appears like a narrow waist, here proteins attach for separation of chromosomes during cell division. In humans, the centromere is located between the two arms of the chromosome, the shorter arm is called the ‘p’ arm (for ‘petite’), while the longer arm is called ‘q’ (‘queue’). Depending on the location of the centromere relative to the two arms, human chromosomes are classified as ‘metacentric’, where the centromere is more or less in the middle of the chromosome, ‘submetacentric’, where the centromere is somewhat offset from the centre or ‘acrocentric’, where the centromere is significantly offset from the centre, with only a very short p arm. In some species such as the mouse, the centromere is located at one end of the chromosome, termed as telocentric. In humans, chromosomes 1, 3, 16, 19 and 20 are metacentric, chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21, 22 and Y are acrocentric, while the remainder are submetacentric. In eukaryotes, the structures at the ends of each linear chromosome are called telomeres and consist of 300–8000 repeats of the sequence TTAGGG, which forms a loop at the end. One function of telomeres is to protect the ends of chromosomes from being recognised as ‘damaged DNA’ and erroneously repaired by the cell’s DNA repair machinery. They also accommodate the loss of sequences during each round of replication, which occurs as a result of the so-called ‘end replication problem’. In cells without the enzyme telomerase (which extends existing telomeres), a short stretch of sequence is lost from the 5′ end of the newly replicated strand with each cell division, which ultimately can lead to cell senescence.

Chromosome structure and band nomenclature

![what is genetic mutation essay This ideogram of the complete chromosome 8 illustrates the general structure of all human chromosomes: short (p) and long (q) arms, joined at the centromere. Each chromosome has a characteristic G-banding pattern, with each band annotated, for example p22 or q23. In chromosomes which are less condensed, more bands are seen as separate entities, while bands may merge together in more condensed chromosomes (for example, q21.1, q21.2 and q21.3 appear as a single band [q21] in a more condensed chromosome 8). The approved way of stating the location q21.1 is q-two-one-point-one (not q-twenty-one-point-one). Telomeres, with a shared structure, are present at both ends of each chromosome. Each telomere is composed of arrays of TTAGGG repeats, followed by a subtelomere, which is formed of repetitive sequences which can be similar between several telomeres. Chromosome ideogram from NCBI Genome Decoration Page.](https://port.silverchair-cdn.com/port/content_public/journal/essaysbiochem/62/5/10.1042_ebc20170053/2/m_ebc-2017-0053ci003.jpeg?Expires=1718722264&Signature=aOY3wo~9tZJbPIuv5pYQ9-8evM46w1t4hfv0GmH8glj3-dCWj9k8IfS7224rjBUGHLiJ2qSrNdoRQZd0pECGzjXzUB9laMc0h1amSa4ofvQxZRnVi~GE003abefrNPbmkTLXfF7yYiYfl9cXIWaieuexx3dqraTRwPru0VnT5~bf2ItsEzkb-ltz1NO3t6GhrLLvG1vWTequNKZmXF0mDymBsmCEwH4isvDLX0HB7XMzDrVhsE2WmBxHfc5gR5ZHASBmw4ye8nKCArpWRnD-Q11n7YiPmevj-jph4WGRFkC3NNkUHc4~9bG2js1Z2fm~Tz1gtTxB8L62QJp~P69zyw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This ideogram of the complete chromosome 8 illustrates the general structure of all human chromosomes: short (p) and long (q) arms, joined at the centromere. Each chromosome has a characteristic G-banding pattern, with each band annotated, for example p22 or q23. In chromosomes which are less condensed, more bands are seen as separate entities, while bands may merge together in more condensed chromosomes (for example, q21.1, q21.2 and q21.3 appear as a single band [q21] in a more condensed chromosome 8). The approved way of stating the location q21.1 is q-two-one-point-one ( not q-twenty-one-point-one). Telomeres, with a shared structure, are present at both ends of each chromosome. Each telomere is composed of arrays of TTAGGG repeats, followed by a subtelomere, which is formed of repetitive sequences which can be similar between several telomeres. Chromosome ideogram from NCBI Genome Decoration Page.

Numerical abnormalities

An abnormality where a cell contains more than two complete sets of the human haploid genome (69 chromosomes or more) is termed as polyploidy. Triploidy (three haploid sets of chromosomes) occurs in 1–3% of pregnancies and usually arises from fertilisation of a single egg with two sperms or sometimes from fertilisation involving a diploid gamete (egg or sperm). Viability of triploid foetuses is usually very low and leads to early spontaneous abortion during pregnancy while tetraploidy (four haploid sets of chromosomes) is even rarer and not compatible with life. However, a situation where the chromosome number is not an exact multiple of the haploid chromosome number is called aneuploidy.

Aneuploidy usually arises because a gamete is formed that contains more or fewer chromosomes than the normal complement. This results from a phenomenon called non-disjunction, where the replicated chromosomes do not separate properly at cell division, and can happen during either meiosis I (non-disjunction of paired chromosomes) or meiosis II (non-disjunction of sister chromatids) ( Figure 4 ). Non-disjunction generates germ cells which either contain an extra copy of one of the chromosomes or lack one chromosome. Fertilisation then leads to the formation of a zygote with an extra chromosome or a missing chromosome respectively ( Figure 5 ). Non-disjunction most commonly occurs during meiosis II of oocyte formation, and is influenced by the mother’s age and other environmental factors. The risk of delivering a trisomic foetus increases from 1.9% in women aged 25–29 years to over 19% in women aged over 39 years. There is also evidence that folic acid deficiency, smoking, obesity and low-dose irradiation with radioactive contaminants increases the risk of non-disjunction.

Principles of meiosis and non-disjunction

For simplicity, only one pair of newly replicated autosomes is shown in two different colours to distinguish the maternal from the paternal chromosome and crossover is not considered. During spermatogenesis, all four meiotic products can form the gametes (sperm), while in oogenesis, only one of the four products will actually become the ovum (egg) as one daughter cell forms a polar body at meiosis I (MI) and another forms a polar body at meiosis II (MII). For clarity, all four potential meiotic products are shown. ( A ) During normal meiosis, four haploid meiotic products are formed. ( B ) If non-disjunction occurs during MI, two daughter cells are formed which completely lack this particular chromosome (nullisomic for this chromosome), while two others contain two copies of the chromosome (disomic). ( C ) If non-disjunction occurs during MII, one nullisomic and one disomic daughter cell is formed, while the remaining two form normally.

Fertilisation outcomes

( A ) Fertilisation of a normal oocyte with a normal sperm cell leads to the formation of a diploid (2n) zygote. ( B ) If a nullisomic oocyte is fertilised, the resulting zygote will be monosomic for one chromosome. ( C , D ) Fertilisation of a disomic oocyte results in trisomic zygotes. Note that in (C), the oocyte has resulted from non-disjunction in meiosis I, and the resulting zygote contains one chromosome (ignoring crossover) from each maternal grandparent as well as the paternal contribution. In (D), the oocyte has resulted from non-disjunction in meiosis II, and the resulting zygote contains two chromosomes (aside from crossover regions) from one grandparent.

Examples of syndromes caused by aneuploidy

Most aneuploidies are lethal. However, those that are viable are listed in Table 4 , together with approximate incidence rates and common symptoms. Foetuses with trisomy 13 or 18 may survive to term, while individuals with trisomy 21 can survive beyond the age of 40. Presence of an extra autosome generally leads to severe developmental abnormalities, and only trisomies of small, gene-poor chromosomes ( Table 1 ) appear to be tolerated. Autosomal monosomies have even more severe consequences, as they invariably lead to miscarriage during the early stages of pregnancy. The developmental consequences of such trisomies and monosomies are a result of an imbalance of the levels of critical gene products encoded on the affected chromosomes. For example, the major features of Down syndrome (DS) are associated with the presence of three copies of a 1.6-Mb region at chromosome location 21q22.2, called the Down Syndrome Critical Region.

Common names are given, where available, together with estimated incidence rates and symptoms frequently associated with the condition.

Having an abnormal number of sex chromosomes generally has milder consequences than abnormal numbers of autosomes and is discussed in more detail in the section ‘The sex chromosomes, X and Y’.

Structural abnormalities

DNA damage, e.g. by radiation or mutagenic chemicals, can lead to chromosome breaks. Complex cell cycle checkpoints prevent cells with unrepaired chromosome breaks, in particular free broken ends (i.e. ends without telomeres), from entering mitosis. DNA repair mechanisms exist which recognise chromosome breaks and attempt to repair them. However, these mechanisms occasionally repair broken chromosomes incorrectly, which can then result in chromosomes with structural abnormalities. Errors during recombination, e.g. between mispaired homologues, may also result in such abnormalities.

If a single chromosome sustains breaks, incorrect repair can lead to material being lost (deletion), inverted or incorporated into a circular structure: a ring chromosome. The resulting structurally abnormal chromosomes can be stably propagated during cell division, as long as they possess a single centromere. Chromosomes without a centromere are eventually lost. Chromosomes with two centromeres are rarely found, in these cases one centromere appears to be suppressed.

If single breaks occur in two separate chromosomes, incorrect joining of the resulting fragments may lead to the exchange of material between chromosomes (translocation). In a balanced reciprocal translocation DNA from two different chromosomes is exchanged without net loss. If both resulting hybrid (or ‘derivative’) chromosomes carry one centromere, they will be replicated and segregated stably. However, during gamete formation, it can happen that only one of the hybrid chromosomes, together with one of the unaltered chromosomes, are segregated into a gamete ( Figure 6 ). Fertilisation of such gametes leads to the formation of a zygote with partial trisomy of genetic material from one of the chromosomes involved in the translocation, and partial monosomy of material from the other participating chromosome. Depending on the location of the breakpoints, and therefore on how much genetic material is present in trisomic or monosomic form, such embryos can be viable, but have a high risk of developmental abnormalities. Nevertheless, approximately 1 in 500 individuals carry a balanced reciprocal translocation. These carriers frequently appear asymptomatic, however, there is an increased miscarriage rate associated with either parent being a translocation carrier and offspring of carriers may present with congenital abnormalities.

Segregation of reciprocal translocations

( A ) A carrier of a reciprocal translocation has one unaltered copy of each chromosome that participates in the translocation, together with two hybrid chromosomes. Only the relevant chromosomes are shown, for illustration each is labelled with a circled number. ( B ) During meiosis, replicated sister chromatids pair up with their homologues. In the case of a translocation carrier, so-called ‘quadrivalents’ can form, in which four instead of two chromosomes pair up. ( C ) Three possible segregation paths are illustrated. During ‘alternate’ segregation, chromosomes 1 and 4, and chromosomes 2 and 3 are segregated into separate gametes. ‘Adjacent 1’ and ‘Adjacent 2’ segregation leads to different combinations as indicated. Note that other segregation patterns can also occur, e.g. where three chromosomes segregate into one gamete, and only one into the other. ( D ) Only alternate segregation leads to gametes which either carry the two unaltered, ‘normal’ chromosomes, or the two hybrid chromosomes. Zygotes formed from these gametes are expected to be phenotypically normal (unless there is a critical gene disruption at the translocation breakpoint). However, in the other two instances, all gametes carry one unaltered and one hybrid chromosome. Fertilisation of these gametes leads to zygotes carrying partial trisomy of one chromosomal segment, and partial monosomy of a different segment.

A second type of translocation is the Robertsonian translocation. Here, two acrocentric chromosomes both break at the centromere, lose their short p arms, and form a single chromosome, containing one centromere and the q arms of both original chromosomes. Carriers of Robertsonian translocations are usually phenotypically normal since only a small amount of genetic material, the nucleolar organiser region (NOR), is present in the short arms of all acrocentric chromosomes (see Figure 2 ). Therefore, the loss of two short arms can be compensated by the remaining acrocentric chromosomes. However, similar to reciprocal translocations, gamete formation and subsequent fertilisation can lead to the formation of zygotes with either monosomy or trisomy of one of the participating acrocentric chromosomes and therefore children with chromosomal imbalances. As is the case with meiosis in carriers of translocations, meiosis in carriers of inversions can also lead to the formation of gametes carrying an unbalanced combination of chromosomes. Therefore, such carriers may also have children with chromosomal imbalances. Carrier frequencies for Robertsonian translocations and inversions which are not considered normal variants are estimated to be 1:1000 and 1:2000 respectively.

Truly balanced translocations and inversions do not lead to the net loss of genetic material, therefore only affect the phenotype of the carrier if either a chromosome break has disrupted an important gene or a break affects the expression of a gene without disrupting its coding region, e.g. by juxtaposing the complete coding region of one gene to the control sequences of a different gene.

Microdeletions, microduplications, CNVs

Molecular genetic analysis of patients with symptoms that cannot be explained using cytogenetics can lead to the identification of the underlying causes, which in many cases are microdeletions, microduplications and other CNVs. Such variations can involve single genes or relatively few genes, which can then allow researchers to determine which particular gene is responsible for specific symptoms. Table 5 shows example of microdeletion and microduplication syndromes, together with key genes, where known, and associated symptoms. Note that in some cases, both microdeletion of a key region as well as microduplication of the same region have been identified as causative for ‘reciprocal’ syndromes. An example is a 3.6-Mb region at 17p11.2, which, when deleted, causes Smith–Magenis syndrome, but when duplicated, causes Potocki–Lupski syndrome.

Where specific genes have been identified as associated with particular features of the syndrome these are noted, but this does not exclude a role for additional genes in the region. Extent of the deletions/duplications often varies between patients but in general larger imbalances are associated with greater severity of symptoms.

Primary sex determination in mammals is chromosomal, meaning that the development of the gonads into male (testes) or female (ovary) is determined by the sex chromosomes. The female caries two X chromosomes (46,XX) and the male has one X and one Y chromosome (46,XY). In some animals, sex determination is in part, or whole, environmentally determined (for example by temperature in most turtles), but in mammals, initiation of sexual fate is entirely driven by the chromosomes. Along with the haploid set of autosomes (22 in humans), each egg of the female has a single X chromosome, while the male can generate a sperm carrying either an X or a Y chromosome. If the egg receives an X chromosome from the sperm, the resulting XX individual will form ovaries through development and be female. If the egg receives a Y chromosome from the sperm, the resulting XY individual will form testes and be male ( Figure 7 ). The Y chromosome is relatively small (57 Mb, with 171 genes and of these only approximately one-third are protein encoding (see Table 1 )), but carries a gene that is crucial for the formation of the testes, encoding a testis-determining factor (TDF), also known as the sex-determining region Y ( SRY ) ( Figure 8 ). All else being wild-type, an individual carrying a normally functioning copy of this gene will develop as a male. Thus, if the Y chromosome is missing (45,X) or if SRY is deleted, female development will ensue, although, two X chromosomes are needed for complete ovarian development. Development of primary sexual characteristics aside from the gonads, that is the reproductive structures (penis, epididymides, seminal vesicles and prostate gland in males; oviducts, vagina, cervix and uterus in females) as well as secondary sexual characteristics (mammary glands in females, along with other sex-specific features such as size, musculature, facial hair and vocal cartilage) are determined by hormones that are secreted by the gonads and this is influenced by many other genetic and environmental factors. Oestrogen, secreted by the ovaries, directs female development, while the newly formed testes secrete anti-Müllerian duct hormone and testosterone which masculinises the foetus.

The X and Y chromosomes determine male or female sexual development

Males produce haploid gametes (sperm) that are either 23,X or 23,Y. Females produce haploid gametes (eggs) that are 23,X. Daughters inherit an X chromosome from their mother and an X chromosome from their father. Sons inherit an X chromosome from their mother and a Y chromosome from their father (paternal chromosomes indicated in blue, maternal chromosomes indicated in green).

Schematic map of the X and Y chromosomes

The X and Y chromosomes are depicted, showing the short (p) and long (q) arms and centromeres (black circle). The pseudoautosomal regions (PAR) 1 and 2 are highlighted in red. The sex-determining genes SRY and DAX1 are indicated. The location of the X inactivation centre (XIC) and the XIST gene is shown. Locations of other genes specifically mentioned in the text are indicated.

The X chromosome is relatively large (156 Mb) and incorporates approximately 1500 genes more than half of which are protein encoding (see Table 1 ), the vast majority of these have nothing to do with sex determination and are needed by both males and females. As such, the imbalance between males and females with respect to the number of X chromosomes in the genome (and therefore potential gene expression levels) needs to be rectified and this is accomplished by different mechanisms in different animal species. This balancing phenomenon, referred to as ‘dosage compensation’ is achieved in mammals by a process termed X chromosome inactivation. Early in development, in every cell in the female embryo, one of the two X chromosomes becomes inactivated, such that the majority, but not all, of the genes are not expressed from the inactive chromosome (Xi). As a consequence, the levels of expression of these genes on the active X chromosome (Xa) in female cells are equivalent to levels in male cells that only have one X chromosome. With respect to which of the two X chromosomes are inactivated, this occurs randomly from one cell to another, but then persists through subsequent cell divisions. This means that as development continues, female tissues become a patchwork, an expression-mosaic, with one of the two X chromosomes activated in some patches and the other X chromosome activated in adjacent patches. The result of this process is visible in female tortoiseshell cats, which are heterozygous for X-linked black and orange coat colour genes; the consequence of X inactivation is evident as random black and orange patches of fur in the adult. As a stochastic process, the proportion of cells that have inactivated the paternally inherited X chromosome, versus the maternally inherited X chromosome, will average 50% each. However, from one individual to another and even from one tissue to another within an individual, there can be considerable skewing from the 50% mean. Think of the tortoiseshell cat, most show roughly equivalent areas of orange and black fur, but some are more black than orange, while others are more orange than black. All female mammals are effectively expression-mosaics with respect to their X chromosomes.

One consequence for geneticists of the male-specific Y chromosome and X-inactivation in females is that the terminology of recessive and dominant allele variants becomes complicated. In addition, as described below, pathogenic allele variants on the X-chromosome can show hugely variable disease penetrance in females.

The pseudoautosomal regions

During human oogenesis, the two X chromosomes synapse in meiosis I and engage in crossover, exactly as the autosomes do. In male spermatogenesis, despite the X and Y chromosomes being of very different sizes and different genetic make-up, the chromosomes do pair (and undergo recombination) in meiosis, at short regions of homology at the ends of each chromosome. These regions are termed pseudoautosomal regions (PAR) 1 and 2 ( Figure 8 ), because they are present on both the X and Y chromosomes; most of the genes in these regions are not subject to X inactivation in females and they behave like autosomal sequences in terms of inheritance patterns. All genes tested within the larger PAR1 escape inactivation in female cells, thus both alleles are expressed in both male and female cells. The smaller PAR2 region has been a recent acquisition in evolutionary terms, there is no equivalent in the mouse (and even some primates). PAR2 genes behave differently. The two most telomeric genes of PAR2, IL9R and CXYorf1 , escape inactivation and are expressed from the Xi as well as Xa in female cells. However, two other genes of PAR2, SYBL1 and HSPRY3 , do become inactivated on Xi. To compensate for this in male cells, the Y chromosome alleles of these two genes are hypermethylated and not expressed, thus in both female and male cells, only one allele is expressed.

In addition to genes within the PARs, there are several homologous gene pairs (or gametologues) present on the X and Y chromosomes, that are located in the X and Y-specific regions, that do not undergo recombination. Consequently these gene pairs have diverged from one another through evolution and often have quite different sequence from each other, although may retain a similar function. An example is the RPS4X and RPS4Y pair, which encode ribosomal proteins of essentially the same function, but differ in 19 of the 263 encoded amino acids. RPS4X escapes inactivation, therefore both alleles are expressed in female cells, while male cells express both single alleles RPS4X and RPS4Y .

SRY, DAX1 and sex determination

The SRY gene is located on the short arm of the Y chromosome, just 5 kb away from the PAR1 boundary ( Figure 8 ). It encodes a transcription factor and is a trigger for driving male sexual development. In 46,XY individuals where the gene is dysfunctional or deleted, female development ensues. Furthermore, in approximately 80% of 46,XX male cases, the SRY gene is found translocated to an X chromosome.

In the developing embryo, a long and narrow structure called the genital ridge is the precursor to gonad formation in both sexes. The somatic cells of the genital ridge differentiate into either Sertoli cells, which promote the testicular differentiation programme or into granulosa cells, which promote ovarian differentiation. Expression of SRY in the genital ridge induces the start of Sertoli cell differentiation. While expression of SRY is brief, it initiates a cascade of events that will lead to male development. The next gene in the cascade is SOX9 , an autosomal gene (located on chromosome 17) which also encodes a transcription factor and is essential for testes development. Expression of SOX9 in the genital ridge acts to induce the expression of several other genes required for testicular development, and also anti-Müllerian duct hormone which suppresses ovarian development. Thus the reverse is the case during ovarian development in XX individuals, where SOX9 is repressed. Some rare 46,XX individuals who have an extra copy of the SOX9 gene, develop as males (despite the absence of an SRY gene). Conversely, individuals who have a non-functional variant of SOX9 or gene deletion, develop a syndrome called campomelic dysplasia (which involves multiple organ systems) and 75% of 46,XY patients with this syndrome develop as phenotypic females or hermaphrodites.

It was initially thought that female development was the default state in the absence of SRY, however, this does not accurately reflect the situation that female sexual development is an active, genetically controlled process. A gene on the X chromosome, DAX1 (aka NROB1 ), which encodes a hormone receptor/transcriptional regulator, is required for female sexual development. DAX1 is expressed in the genital ridge shortly after SRY and antagonises the function of SRY by interfering with the induction of SOX9 , in a dose-dependent manner. Normally, in 46,XY genital ridge cells, DAX1 is expressed from the X chromosome and SRY from the Y chromosome, in a ratio that leads to testes development. In 46,XX genital ridge cells, one copy of DAX1 is expressed (the other is inactivated on Xi), in the absence of SRY, to produce ovaries. However, if there are two active copies of DAX1 (for example, through gene duplication on Xa), along with SRY in 46,XY individuals, this leads to poorly formed gonads that produce neither anti-Müllerian duct hormone nor testosterone and individuals appear phenotypically female.

Following initiation of the female developmental pathway, several genes play a key role in female sexual development. The WNT4A gene (chromosome 1) encodes a secreted factor that is essential for the growth of ovarian follicle cells and is down-regulated by SOX9. The gene NR5A1/SF1 (on chromosome 9) encodes another transcriptional regulator important in both male and female pathways (as well as in the adrenal glands). Along with SRY, SF1 co-regulates SOX9 expression and is therefore critical in male sex determination. However, this multifunctional protein also plays a role later in ovarian follicular development. Thus, mutations in this gene can lead to disorders of sex development (DSD), including sex reversal, in both XX and XY individuals. Thus the SRY and DAX1 genes (present on Y and X chromosomes respectively) determine sex, as they act to flip the switch between male and female sexual fates. However, in each case, there are critical downstream regulators that promote one programme and/or inhibit the other programme and variant or mutated forms of these genes can cause DSD.

The human Y chromosome has 63 protein encoding genes, and aside from genes within the PARs and the gametologues, the majority are expressed in the testis and are involved in male fertility. The Y chromosome also has a large number (392 at last count) of pseudogenes. These have resulted from the fact that the Y chromosome (outside the PARs) has no recombination partner. As a consequence, through evolution, harmful gene mutations cannot uncouple (and thereby be selected against) from necessary genes and therefore such deleterious mutations, now in the form of pseudogenes, hitchhike along with the necessary genes.

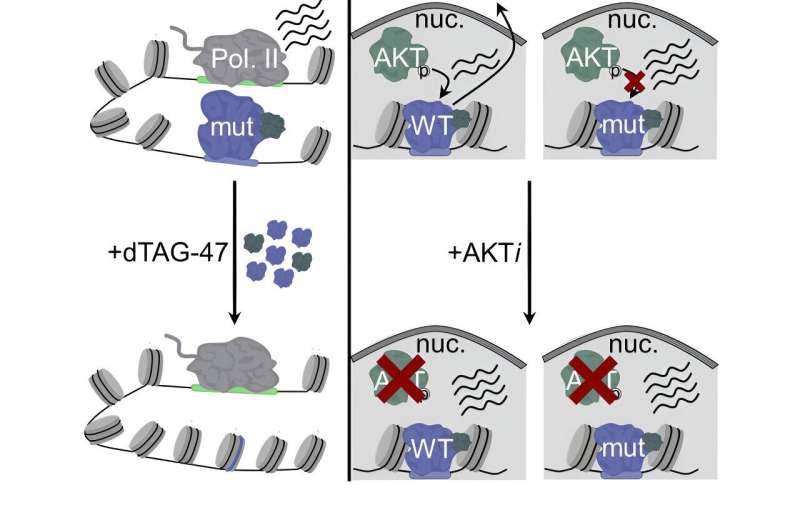

The process of X inactivation

Early in female development (the early blastocyst), one X chromosome in each 46,XX cell becomes inactivated. This is initiated from a region called the X-inactivation centre (XIC) at Xq13 and in humans occurs at random, it can be either the X chromosome inherited from the mother, or the one inherited from the father. Inactivation starts with the expression of a long, non-coding RNA located within the XIC, called the X-inactive specific transcript ( XIST ), from the chromosome that will be silenced ( Figure 9 ). XIST RNA coats the chromosome from which it is expressed, spreading from the XIC outwards in both directions along the entire length of the chromosome. This then leads to several epigenetic changes along the coated chromosome, including depletion of RNA polymerase II, loss of histone acetylation and an increase in histone ubiquitination and repressive methylation to silence gene expression on Xi. The Xi chromosome becomes condensed and can be seen microscopically as a dense area to the side of the nucleus referred to as the Barr body (as it was first described by the cytogeneticist Murray Barr). The inactivation is stable through subsequent cell divisions so that the same Xi is maintained in each cell lineage throughout development and adult life, with the exception of the germline. In germ cells X inactivation is reversed, so that all oocytes contain an active X.

A simplified view of genes located at the XIC (not to scale), which maps at Xq13.2 on the human X chromosome and spans over 1 Mb. XIST (red) is surrounded by a number of other non-coding RNA genes (blue), which have an effect upon XIST regulation, including TSIX . Additionally, there are protein encoding genes (yellow), within the XIC region and recently RLIM has been shown to regulate XIST expression. Deletions across this region affect the process of X chromosome inactivation, but the function of all the genes and sequence regions located at XIC are yet to be fully understood.

At the XIC another non-coding transcript is expressed, partially overlapping and in the opposite (antisense) direction to XIST , the TSIX transcript is specifically expressed from the active X chromosome Xa ( Figure 9 ). TSIX acts locally as a negative regulator of XIST expression and protects Xa against inactivation. In conditions of aneuploidy, with more than two X chromosomes, only one X remains activated, which reveals that there is a counting mechanism at play. For each autosome set, one X chromosome remains active, although how this occurs is currently poorly understood. Deletion of XIC sequences (including the XIST and TSIX genes) from one X chromosome still allows inactivation of the other, wild-type X chromosome, in 46,XX individuals. Furthermore, in transgenic mice, introduction of an XIC into an autosome, renders the autosome subject to silencing. These studies show that the XIC (and XIST ) is required for initiation of chromosome inactivation in cis , but that the counting mechanism must involve factors and regions outside XIST and TSIX . It is thought that X chromosome inactivation (and the counting mechanism) must be regulated by X-encoded activators and autosomally encoded suppressors which control XIST . Recently, an X-linked gene, RLIM (or RNF12 ), located 500 kb upstream of XIST , has been identified as an important regulator of XIST expression, as the RLIM protein works to degrade an inhibitor of XIST transcription. However, the complexities of this process are yet far from being fully understood.

Approximately one-fifth of the genes on the X chromosome escape inactivation on Xi. These either have a Y chromosome homologue (for example, located in a PAR, as described above), or those that do not have a Y homologue tend to lie in clusters (mostly on the short arm, Xp) and apparently the 2:1 dosage (expression in female:male cells) is not problematic. It is thought that these genes are surrounded by a DNA sequence that binds a protein factor (termed CTCF) that can insulate the genes from the actions of XIST .

Due to the low gene count of the Y chromosome and the process of X inactivation, having an abnormal number of sex chromosomes has milder consequences than abnormal numbers of autosomes. Females with Triple X syndrome (47,XXX) or males with 47,XYY tend to be taller than average, but usually show few other physical differences ( Table 4 ) and have normal fertility, thus can go undiagnosed. X inactivation in 47,XXX cells will lead to the inactivation of two X chromosomes, so despite the presence of the trisomy, the vast majority of the X-linked genes will be expressed from just the single Xa in each cell. However, overexpression of genes that escape X inactivation (as described above) gives rise to the syndrome. In 47,XYY men, there is double the Y chromosome gene dose. Therefore, there will be double the levels of Y-specific gene expression and an extra dose of products of the genes that have an X chromosome homologue (one dose from X and two doses from Y). Males with 47,XYY, as well as the above noted features, tend to have an increased risk of behavioural, emotional and social difficulties.

Men with Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) carry an extra X chromosome and tend to be sterile, however symptoms are frequently very subtle ( Table 4 ) and only noticed at puberty. Again, one of the two X chromosome will be inactivated (Xi) in each cell, therefore, 47,XXY cells will only show overexpression of genes (compared with 46,XY cells) that escape X inactivation (in 47,XXX individuals, this extra expression is in the context of female development, while in 47,XXY individuals it is in the context of male development, so can have different consequences). Men with 48,XXXY display a more severe syndrome, resulting from the extra overexpression of genes that escape X inactivation, as well as the expression of Y-specific genes.

Complete loss of the X chromosome, 45,Y is early embryonic lethal. However, females with monosomy of chromosome X (45,X) or partial loss of an X chromosome, develop Turner syndrome ( Table 4 ). In 45,X cases where an entire sex chromosome (X or Y) is lost, the remaining X chromosome does not undergo inactivation, however, this leads to half the normal expression levels of genes that do not undergo X chromosome inactivation. As such, the loss of dosage of several of these genes contributes to the syndrome. In cases where there is only partial loss of the X chromosome, such individuals will display some features of the syndrome. A gene that lies within PAR1, with alleles on both X and Y chromosomes, SHOX ( Figure 8 ), is responsible for approximately two-thirds of the height deficit seen in Turner syndrome individuals. With loss of this region of the X chromosome, SHOX is expressed from the other allele, therefore at only half the usual levels and this is not sufficient (haploinsufficiency) to fully achieve its required growth-related function. Heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in this gene alone in both males and females causes Leri–Weill dyschondrosteosis which is characterised by skeletal dysplasia and short stature. Loss of function in both alleles causes Langer mesomelic dysplasia, which is associated with severe limb aplasia and severe height deficit. Conversely, duplication of the SHOX gene is associated with tall stature.

Pathogenic single gene variants

Haemophilia a, an example of x-linked recessive inheritance.

Haemophilia A is a condition where blood clotting is defective, due to deficiency in the activity of one of the blood clotting factors, factor VIII. Symptoms can vary considerably, from mild cases, where patients only bleed excessively after major trauma or surgery, to severe cases, where patients suffer up to 30 annual episodes of spontaneous or excessive bleeding, even after minor trauma. Factor VIII is encoded by the F8 gene, located on chromosome Xq28 ( Figure 8 ) and the gene is subject to X inactivation. There is no Y homologue, therefore if males inherit a pathogenic variant allele on the maternal X chromosome (or in 30% cases have a de novo mutation), they will be affected and disease severity will reflect the type of mutation (ranging from expression of a dysfunctional protein to complete absence of the factor). Females who are heterozygous, carrying one copy of a pathogenic variant allele, are generally asymptomatic and thus haemophilia shows a typical X-linked recessive inheritance pattern (see section on ‘Single-gene disorders’). However, as a result of X inactivation, some cells will express the wild-type F8 allele (from Xa), while other cells will express the pathogenic variant allele and the overall expression ratio between the two alleles can be 50:50 or skewed to one or the other. No cell will express both alleles. As a consequence, most female carriers produce enough factor VIII (between 30 and 70% of normal circulating levels, the variation depending both upon the nature of the variant allele and the degree to which it is Xi silenced) to appear largely unaffected. However, a significant proportion of female carriers do show some bleeding problems (for example, heavy menstrual bleeding) and in some cases (carriers who have less than 30% of normal factor VIII levels) can show mild haemophilia symptoms. In rare cases, where females inherit two variant alleles, they are more severely affected, as in males.

Rett syndrome, an example of X-linked dominant inheritance

Rett syndrome is an X-linked, dominant, neurodevelopmental disorder seen predominantly in females and becomes apparent in babies between the age of 6 and 18 months. After an initial phase of apparently normal development, individuals develop severe mental and physical disabilities, displaying coordination problems, slower growth, repetitive movements, seizures, scoliosis and other problems. The age at which symptoms first appear and the severity, varies considerably from one individual to another. Rett syndrome affects approximately 1 in 10000 females and is a single gene disorder involving the X-linked MECP2 gene. Due to the severity of symptoms, this usually arises as a de novo mutation. Boys with a similar mutation have a more severe phenotype, for example congenital encephalopathy, and die shortly after birth. MECP2 encodes a protein that binds to methylated DNA and has an important epigenetic function as a repressor of gene expression. Although the gene is normally expressed throughout the body, its function is essential in mature nerve cells and the phenotypic consequences of loss-of-function mutations (for example, loss of expression mutations or mutations that give rise to a non-functional protein) are most profound in the brain. The nature of the mutation and the extent to which the allele has lost function dictates one variable seen in disease severity. Additionally, the MECP2 gene is subject to X chromosome inactivation, this therefore also contributes to the variation seen in disease severity. If the mutant allele shows skewed inactivation (such that this allele is more frequently inactivated on Xi than the wild-type allele), this can result in considerably milder symptoms. It has been proposed that following X inactivation during development, cells which inactivated the chromosome carrying the wild-type MECP2 allele and therefore express the mutant MECP2 allele, may be selected against, resulting in a skewed X inactivation body pattern. In addition other genetic factors may exacerbate or alleviate the disease pathogenicity to contribute to the variation observed. The levels of MECP2 are critical and both too little and too much are deleterious. Therefore, mutations that result in overexpression of this gene give rise to a different syndrome ( MECP2 duplication syndrome). In males MECP2 duplication leads to severe intellectual disability and epilepsy; similar duplications in females lead to a more variable condition depending upon the proportion of cells that inactivate the X chromosome containing the duplication.

In conclusion, the presentation and severity of syndromes and diseases resulting from variants of the sex chromosomes are not only influenced by the nature of the variant itself, but also by the sex-linked ploidy of these chromosomes and the consequences of X chromosome inactivation.

Many conditions and diseases depend on the genotype at a single locus (or gene), with inheritance following Mendel’s laws of segregation, independent assortment and dominance. Therefore, these diseases are often called ‘Mendelian’ although not all inherited disorders follow Mendel’s laws (e.g. triplet-repeat diseases and imprinting disorders). To date, over 6000 phenotypes have been identified for which the molecular basis is known, these phenotypes and the associated genes are collected in the database OMIM (‘Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man’, https://www.omim.org/ ). Some well-characterised examples are shown in Table 6 .

Diseases are shown together with their inheritance patterns, the affected gene, the most commonly found types of mutation, and estimated incidence rates. Note, some diseases, for example osteogenesis imperfecta (of which there are several forms), can be caused by pathogenic variants in one of a number of different genes.

Modes of inheritance and examples