The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

6 Chapter 6: Qualitative Research in Criminal Justice

Case study: exploring the culture of “urban scrounging” 1.

Research Purpose

To describe the culture of urban scrounging, or dumpster diving, and the items that can be found in dumpsters and trash piles.

Methodology

This field study, conducted by Dr. Jeff Ferrell, currently a professor of sociology at Texas Christian University, began in 2002. In December of 2001, after resigning from an academic position in Arizona, Ferrell returned home to Fort Worth, Texas. An avid proponent for and participant in field research throughout his career, he decided to use the next eight months, prior to the 2002 academic year beginning, to explore a culture in which he had always been interested, the urban underground of “scrounging, recycling, and secondhand living” (p. 1). Using the neighborhoods of central Fort Worth as a backdrop, Ferrell embarked, often on his bicycle, into the fife of a dumpster diver. While he was not completely homeless at the time, he did his best to fully embrace the lifestyle of an urban scrounger and survive on what he found. For this study, Ferrell was not only learning how to survive off of the discarded possessions of others, he was systematically recording and describing the contents of the dumpsters and trash piles he found and kept. While in the field, Ferrell was also exploring scrounging as a means of economic survival and the social aspects of this underground existence. A broader theme of Ferrell’s research emerged as he encountered the number and vast array of items he found discarded in trash piles and dumpsters. This theme concerns the “hyperconsumption” and “collective wastefulness” (pp. 5–6) by American citizens and the environmental destruction created by the accumulating and discarding of so many material goods.

Results and Implications

Ferrell’s time spent among the trash piles and dumpsters of Fort Worth resulted in a variety of intriguing yet disturbing realizations regarding not only material excess but also social and personal change. While encounters with others were kept to a minimum, as they generally are for scroungers, Ferrell describes some of the people he met along the way and their conversations. Whether food, clothes, building materials, or scrap metal, the commonality was that scroungers could usually find what they were looking for among the trash heaps and alleyways. Throughout his book, Ferrell often focuses on the material items that he discovered while scrounging. He found so much, he was able to fill and decorate a home with perfectly good items that had been discarded by others, including the bicycle he now rides and a turquoise sink and bathtub. He found books and even old photographs and other mementos meant to document personal history. While discarded, these social artifacts tell the stories of society and often have the chance to find altered meaning when possessed by someone new.

Beyond the things found and people met, Ferrell discusses the boundary shift that has taken urban scrounging from deviant to criminal as lines are often blurred between public access and ownership. Not only do these urban scroungers face the stigma associated with their scrounging activities, those who dive in dumpsters and dig through trash piles can face criminal charges for trespassing. While this makes scrounging more challenging, due to basic survival or interest, the wealth of items and artifacts to be found are often worth the risk. Ultimately, Ferrell’s experiences as an urban scrounger provide not only a description of this subculture but also a critique on American consumption and wastefulness, a theme that becomes more important as Americans and others continue in economically tenuous times.

In This Chapter You Will Learn

To explain what it means for research to be qualitative

To describe the advantages of field research

To explain the challenges of field studies for researchers

To provide examples of field research in the social sciences

To discuss the case study approach

Introduction

In Chapter 2, you read about the differences between quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Whereas methods that are quantitative in nature focus on numerical measurements of phenomena, qualitative methods are focused on developing a deeper understanding regarding groups of people, or subcultures, about which little is known. Using detailed description, findings from qualitative research are generally more sensitizing, providing the research community and the interested public information about these generally elusive groups and their behaviors. A debate rages between criminologists as to which type of research should be achieved and referenced more often. The truth is that both have something valuable to offer regarding the study of deviance, crime, and victimization.

Field Research

Qualitative methodologies involve the use of field research, where researchers are out among these groups collecting information rather than studying participant behavior through surveys or experiments that have been developed in artificial settings. Field research provides some of the most fascinating reading because the researcher is observing closely or acting as part of the group and is therefore able to describe in depth not only the subjects’ behaviors, but also consider the motivations that drive their behaviors. This chapter focuses on the use of qualitative methods in the social sciences, particularly the use of participant observation to study deviant, and sometimes criminal, behaviors. The many challenges as well as advantages of conducting this type of research will be discussed as will well-known examples of past field research and suggestions for conducting this type of research. First, however, it is important to understand what sets qualitative field research apart from the other methodologies discussed in this text.

The Study of Behavior

It is common for criminal justice researchers to rely on survey or interview methodologies to collect data. One advantage of doing so is being able to collect data from many respondents in a short period of time. Technology has created other advantages with survey methodology. For example, Internet surveys are a convenient, quick, and inexpensive way to reach respondents who may or may not reside nearby. Researchers often survey community residents and university students, but may also focus specifically on offender or victim samples. One significant limitation of using survey methodologies is that they rely on the truthfulness of the respondents. If researchers are interested in attitudes and behaviors that may be illegal or otherwise controversial, it could be that respondents will not be truthful in answering the questions placed before them. Survey research has focused on past or current drug use (see the Monitoring the Future Program), past victimization experiences (see the National Criminal Victimization Survey), and prison sexual assault victimization (see the Prison Rape Elimination Act data collection procedures conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics), just to name a few. If a student uses marijuana but does not want anyone to know, they may choose to falsify their survey responses when asked about marijuana use. If a citizen or prison inmate has been sexually assaulted but is too ashamed or afraid to tell anyone, they may be untruthful when asked about such victimization experiences on a survey. The point is, although researchers attempt to better understand the attitudes and behaviors of a certain population through the use of surveys, there is one major drawback to consider: the disjunction between what people say and what they actually do. As mentioned previously, a student may be a drug user but not admit to it. Someone may be a gang member, but say they are not when asked directly about it. Someone may respond that they have never committed a crime or been victimized when in fact they have. In short, people sometimes lie and there are many potential reasons for doing so. Perhaps the offender or drug user has not yet been caught and does not want to be caught. Whatever the reason, this is a hazard of measuring attitudes and behaviors through the use of surveys. One way to overcome the issue of untruthfulness is to conduct research using various forms of actual participation or observation of the behaviors we want to study. By observing someone in their natural environment (or, “the field”), researchers have the ability to observe behaviors firsthand, rather than relying on survey responses. These research strategies are generally known as participant observation methods.

Types of Field Research: A Continuum

Participant observation strategies involve researchers studying groups or individuals in their natural setting. Think of participant observation as a student internship. Students may read about law enforcement in their textbooks and discuss law enforcement issues in class, but only through an internship with a law enforcement agency will a student have a chance to understand how things actually happen from firsthand observation. Field strategies were first developed for social science, and particularly crime, research in the 1920s by researchers working within the University of Chicago’s Department of Sociology. The “Chicago School,” as this group of researchers is commonly known, focused on ethnographic research to study urban crime problems. Emerging from the field of anthropology, ethnographic research relies on field research methodologies to scientifically examine human culture in the natural environment. Significant theoretical developments within the field of criminology, such as social disorganization, which focused on the impact of culture and environment, were advanced at this time. For example, researchers such as Shaw and McKay, Thrasher, and others used field research to study the activities of subcultures, particularly youth gangs, as well as areas of the city that were most impacted by crime. These researchers were not interested in studying these problems from afar. Instead, they were interested in understanding social problems, including the impact of environmental disintegration, from the field.

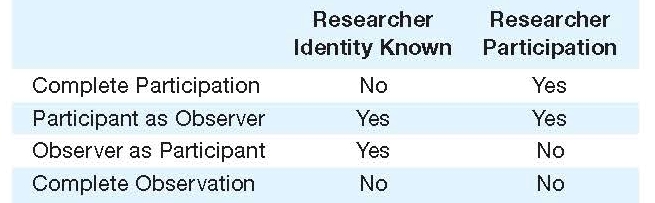

There are various ways to conduct field research, and these can be placed on a continuum from most to least invasive and also from more qualitative to more quantitative. In attempting to understand phenomena from the standpoint of the actors, a researcher may participate fully in the behaviors of the group or may instead choose to observe from afar as activities unfold. The most invasive, and also most qualitative, form of participant observation is complete participation. The least invasive, and also most quantitative, is complete observation. In between these two are participant as observer and observer as participant. Each of these strategies will now be discussed in more detail.

Complete participation, sometimes referred to as disguised observation, is a method that involves the researcher becoming a full-fledged member of a particular group. For example, if a researcher is interested in understanding the culture of correctional officers, she may apply to be hired on as a correctional officer. Once hired on, the researcher will wear the uniform and obtain firsthand experience working in a prison environment. To study urban gangs, a researcher may attempt to be accepted as a member or associate of the gang. In complete participation, the true identity of the researcher is not known to the members of the group. Therefore, they are ultimately just like any other member of the group under study. Not only will the researcher have the ability to observe the group from the inside, he can also manipulate the direction of group activity through participation or through the use of confederates. This method is considered the most qualitative because, as a complete participant, the researcher will be fully sensitized to what it is like to be a member of the group under study, and will fully participate in the group’s activities. The researcher can then share the information he has gathered on the group’s inner workings, motivations, and activities from the perspective of a group member.

Researchers utilizing the participant as observer method will also participate in the activities of the group under study. The difference between the complete participant strategy and participant as observer strategy is that in the participant as observer method, the researcher reveals herself as a researcher to the group. Her presence as a researcher is known. Accordingly, the researcher does not overtly attempt to influence the direction of group activity. While she does participate, the researcher is more interested in observing the group’s activity and corresponding behaviors as they occur naturally. So, if a researcher wanted to examine life as a homeless person, she might go to where a group of homeless persons congregate. The researcher would introduce herself as such but, if safe, stay one or many days and nights out with the homeless she meets in order to conduct observations and participate in group activities.

The third participant observation strategy is observer as participant. As with the participant as observer method, researchers using the observer as participant method reveal themselves to the group as a researcher. Here again, their presence as a researcher is known. What makes this strategy different from the first two is that the researcher does not participate in the group’s activities. While he may interact with the participants, he does not participate. Instead, the researcher is there only to observe. An example of this method would be a researcher who conducts “ride-alongs” in order to study law enforcement behavior during traffic stops. The researcher will interact with the officers, but he will not participate or even exit the car during the traffic stops being observed.

The least invasive participant observation strategy is complete observation. As you will learn in Chapter 7, this is a totally unobtrusive method; the research subjects are not aware that they are being observed for purposes of research. Think of a law enforcement officer being on a stakeout. These officers generally sit in unmarked vehicles down the street as they observe the movements and activities of a certain person or group of people. Researchers who are complete observers work much the same way. While being the least invasive, complete observation is also the least qualitative. Studying an individual or group from afar means that there is no interaction with that individual. Without this interaction, researchers are unable to gain a more sensitized understanding of the motivations of the group. This strategy is considered to be more quantitative because researchers must rely on counts of activities or movements. For example, if you are a researcher interested in studying how many drivers run a stop sign on campus, you may sit near the intersection and observe driver behavior. In collecting the data, you will count how many drivers make a complete stop, how many come to a rolling stop, and how many run the stop sign altogether. Now, although you may have these counts, you will not know why drivers stopped or not. It could be that one driver had a sick passenger who he was rushing to the hospital and that is why he did not come to a complete stop. As with most quantitative research, as a complete observer, questions of “why?” often go unanswered.

FIGURE 6.1 | Differences among Participant Observation Methods

Advantages and Disadvantages of Field Research by Method

As with any particular research method, there are advantages and disadvantages to conducting field research. Some of these are specific to the type of field research a researcher decides to conduct. One general advantage to participant observation methods is that researchers are able to study “hard to reach” populations. A disadvantage is that these groups may be difficult to study for a number of reasons. It could be that the group is criminal in nature, such as a youth gang, a biker gang, or the Mafia. While perhaps not criminal, the individual or group may be involved in deviant behaviors that they are unwilling to discuss even with people they know. An additional disadvantage is that there could be administrative roadblocks to conducting such research. If a researcher wants to understand the correctional officer culture but the prison will not allow the researcher to conduct the study, she may have to get hired on and conduct the research as a full participant. Examples of research involving each of these situations will be discussed later in this chapter.

Another challenge for field researchers is the ability to maintain objectivity. In Chapter 2, the importance of objectivity for scientific research was discussed. If data gathered is subjective or biased in some way, research findings will be impacted by this subjectivity and will therefore not be reflective of reality. While objectivity would be easier to maintain from afar, the closer a researcher becomes to a group and its members, the easier it may be to lose objectivity. This is true particularly for complete participants. For researchers who participate as members of the group under study, it may become difficult not to begin to identify with the group. When this occurs, and the researcher loses sight of the research goals in favor of group membership, it is called “ going native. ” This is a hazard of field research in which the researcher spends a significant amount of time, perhaps years, within a group. The researcher may begin to see things from the group’s perspective and therefore not be able to objectively complete the intended study. To balance this possible hazard of complete participation is the advantage of not having reactivity. Because the research subjects do not know they are being observed, they will not act any differently than they would under normal circumstances. Researchers therefore avoid the Hawthorne Effect when conducting field research as a complete participant.

There is the possibility that a researcher who incorporates the participant as observer strategy may also go native. Although his presence as a researcher is known, he is interacting with the group and participating in group activities. Therefore, it is possible he may begin to lose objectivity due to an attachment to or identification with the group under study. Whereas complete participants can avoid the Hawthorne Effect, participants as observers do not have this luxury. Even though these researchers may be participating in group activities, because their presence as a researcher is known, it can be expected that the group may in some way alter their behavior because they are being observed. An additional disadvantage to this strategy is that it may take time for a researcher to be accepted by group members who are aware of the researcher’s presence. If certain group members are uncomfortable with the researcher’s presence, they may make it difficult for the researcher to interact with other members or join in group activities.

Researchers on the observing end of the participant observation continuum face some similar and some unique challenges. Those who conduct observer as participant field studies will also face reactivity, or the Hawthorne Effect, because their presence as a researcher is known to the group under study. As in the ride-along example discussed previously, if a patrol officer knows she is being observed, she may alter her behavior in such a way that the researcher is not observing a realistic traffic stop. Additionally, these researchers may face difficulties gaining access or being accepted into the group under study, especially since they are there only to observe and not to participate with the group. In this case, the researcher may be ostracized even further by the group because she is not acting as one of them.

Researchers acting as complete observers to gather data on an individual or group are not limited by reactivity. Because the research subjects are unaware they are being observed, the Hawthorne Effect will not impact study findings. The advantage is that this method is totally unobtrusive, or noninvasive. The main disadvantage here is that the researcher is too far away to truly understand the group and their behaviors. As mentioned previously, at this point, the research becomes quite quantitative because the researcher can only observe and count movements and interactions from afar. Lacking in context, these counts may not be as useful in understanding a group as findings would be from the use of another participant observation method.

Costs One of the more important factors to consider when determining whether field research is the best option is the demand such research may place on a researcher. If you remember from the opening case study, Ferrell spent months in the field to collect information on urban scrounging. Researchers may spend weeks, months, and even years participating with and/or observing study subjects. Due to this, they may experience financial, personal, and sometimes professional costs. Time away from family and friends can take a personal toll on researchers. If the researcher is funding his own research or otherwise not able to earn a salary while undergoing the field study, he may suffer financially. Finally, also due to time away and perhaps due to activities that may be considered unethical, fieldwork can have a negative impact on a researcher’s career. While these demands are very real, past researchers have found ways to successfully navigate the world of field research resulting in fascinating findings and ultimately coming out unscathed from the experience.

Gaining Access Gaining access to populations of interest is also a difficult task to accomplish as these populations are often small, clandestine groups who generally keep out of the public eye. Field research is unlike survey research in that there is not a readily available list of gang members or dumpster divers from which you can draw a random sample. Instead, researchers often rely on the snowball sampling technique. If you remember from Chapter 3, snowball sampling entails a researcher meeting one or a handful of group members and receiving introductions to other group members from the initial members. One member leads you to the next, who then leads you to the next.

When gathering information as an observer as participant, a researcher should be straightforward and announce her intentions to group members immediately. It may be best to give a detailed explanation of her presence and purpose to group leaders or other decision-makers. If this does not happen, when the group does find out a researcher is in their presence, they may feel the researcher was trying to hide something. If the identity of the researcher is known, it is important that the researcher be a researcher, and that she not pretend to be one of the group, as this may also cause problems. It may be disconcerting to group members if an outsider thinks she is closer to the group than members are willing to allow her to be.

While complete participant researchers may be introduced to one or more members, this does not mean that they will be readily accepted as part of the group. This is true even if they are acting as full participants. There are some things researchers can do to increase their chances of being accepted. First, researchers should learn the argot, or language, of the group under study. Study subjects may have a particular way of speaking to one another through the use of slang or other vernacular. If a researcher is familiar with this argot and is able to use it convincingly, he will seem less of an outsider. It is also important to time your approach. A researcher should be aware, as much as possible, about what is happening in the group before gaining access. If a researcher is studying drug dealers and there was just a big drug bust or if a researcher is studying gangs and there was recently a fight between two gangs, it may not be the best time to gain access as members of these groups may be immediately suspicious of people they do not know.

Researchers often must find a gatekeeper in order to join a group. Gatekeepers are those individuals who may or may not know about the researcher’s true identity, who will vouch for the researcher among the other group members and who will inform the researcher about group norms, territory, and the like. Gatekeepers may lobby to have a researcher become a part of the group or to be allowed access to the place where the group gathers. While this is helpful for the researcher, it can be dangerous for the gatekeeper, especially if something goes wrong. If the researcher is attempting to be a full participant but her identity as a researcher is exposed, the gatekeeper may be held responsible for allowing the researcher in. This may be the case even if the gatekeeper was not aware of the researcher’s true identity. If a researcher does not want to enter the group himself, he may find an indigenous observer, or a member of the group who is willing to collect information for him. The researcher may pay or otherwise remunerate this person for her efforts as she will be able to see and hear what the researcher could not. A similar problem may arise, however, if this person is caught. There may be negative consequences to pay if it is found out that she is revealing information about the group. Additionally, the researcher must be careful when analyzing the information provided as it may not be objective, or may not even be factual at all.

Maintaining Objectivity Once a researcher gains access, there is another issue she must face. This is the difficulty of remaining an outsider while becoming an insider. In short, the researcher must guard against going native. Objectivity is necessary for research to be scientific. If a researcher becomes too familiar with the group, she may lose objectivity and may even be able to identify with and/or empathize with the group under study. If this occurs, the research findings will be biased and not an objective reflection of the group, what drives the group, and the activities in which the group members participate. For these reasons, it is not suggested that a researcher conduct field research among a group of which he is a member. If a researcher has been a member of a social organization for many years and is friends, or at least acquaintances, with many of the members, it would be very difficult for her to objectively study the group. The researcher may consider the group and the group’s activities as normal and therefore miss out on interesting relationships and behaviors. This is also why external researchers are often brought in to evaluate agency programs. If employees of that program are tasked with evaluating it, they may—consciously or not—design the study in such a way that findings are sure to be positive. This may be because they feel that a negative evaluation will mean an end to the program and ultimately an end to their jobs. Having such a stake in the findings of research is sure to impact the objectivity of the person tasked with conducting the study. While bringing in external researchers may ensure objectivity, these researchers face their own challenges. Trulson, Marquart, and Mullings 3 offer some tips for breaking in to criminal justice agencies, specifically prisons, as an external researcher. The first two tips pertain to obtaining access through the use of a gatekeeper. The third tip focuses on the development and cultivation of relationships within the agency in order to maintain access. The remaining tips describe how a researcher can make a graceful exit once the research project is completed while still maintaining those relationships, as well as building new ones, for potential future research endeavors.

❑ Tip #1: Get a Contact

❑ Tip #2: Establish Yourself and Your Research

❑ Tip #3: Little Things Count

❑ Tip #4: Make Sense of Agency Data by Keeping Contact

❑ Tip #5: Deliver Competent Readable Reports on Time

❑ Tip #6: Request to Debrief the Agency

❑ Tip#7: Thank Everyone

❑ Tip #8: Deal with Adversity by Planning Ahead

❑ Tip #9: Inform the Agency of Data Use

❑ Tip #10: Maintain Trust by Staying in for the Long Haul (pp. 477–478)

CLASSICS IN CJ RESEARCH

Youth Violence and the Code of the Street

Research Study

Based on his ethnography of African American youth living in poor, inner-city neighborhoods, Elijah Anderson 2 developed a comprehensive theory regarding youth violence and the “code of the street.” Anderson explains that, stemming from a lack of resources, distrust in law enforcement, and an overall lack of hope, aggressive behavior is condoned by the informal street code as a way to resolve conflict and earn respect. Anderson’s detailed description and analysis of this street culture provided much needed awareness regarding the context of African American youth violence. Like other research discussed in this chapter, these populations could not be sent an Internet survey or be surveyed in a classroom. The only way for Anderson to gain this knowledge was to go out to the streets and observe and interact with the youth himself. To do this, he conducted four years of field research in both the inner city and the more suburban areas of Philadelphia. During this time, he conducted lengthy interviews with youth and acted as a direct observer of their activities. Anderson’s research is touted for bringing attention to and understanding of inner-city life. Not only does he describe the “code of the street,” but, in doing so, he provides answers to the problem of urban youth violence.

Documenting the Experience Researchers must also decide how best to document their experiences for later analysis. There is a Chinese Proverb that states, “the palest ink is better than the best memory.” Applied here, researchers are encouraged to document as much as they can, as giving a detailed account of things that have occurred from memory is difficult. When taking notes, it is important for researchers to be as specific as possible when describing individuals and their behaviors. It is also important for researchers not to ignore behaviors that may seem trivial at the time, as these may actually signify something much more meaningful.

Particularly as a complete participant, researchers are not going to have the ability to readily pull out their note pad and begin taking notes on things they have seen and heard. Even careful note taking can be dangerous for a researcher who is trying to hide his identity. If a researcher is found to be documenting what is happening within the group, this may breed distrust and group members may become suspicious of the researcher. This suspicion may cause the group members to act unnaturally around the researcher. Even if research subjects are aware of the researcher’s identity, having someone taking notes while they are having a casual conversation can be disconcerting. This may make subjects nervous and unwilling to participate in group activities while the researcher is present. Luckily, with the advance of technology, documentation does not have to include a pen and a piece of paper. Instead, researchers may opt for audio and/or visual recording devices. In one-party consent states, it is legal for one person to record a conversation they are having with another. Not all states are one-party consent states, however, so researchers must be careful not to break any laws with their plan for documentation.

WHAT RESEARCH SHOWS: IMPACTING CRIMINAL JUSTICE OPERATIONS

Application of Field Research Methods in Undercover Investigations

Participant observation research not only informs criminal justice operations, but police and other investigative agencies use these methods as well. Think about an undercover investigation. While the purpose of going undercover for a law enforcement officer is to collect evidence against a suspect, the officer’s methods mirror those of an academic researcher who joins a group as a full participant. In the 1970s, FBI agent Joe Pistone 4 went undercover to obtain information about the Bonnano family, one of the major Sicilian organized crime families in New York at the time. Assuming the identity of Donnie Brasco, the jewel thief, Pistone infiltrated the Bonnano family for six years. Using many of the techniques discussed here—learning the argot and social mores of the group, finding a gatekeeper, documenting evidence through the use of recording devices—by the early 1980s, Pistone provided the FBI with enough evidence to put over 100 Mafioso in prison for the remainder of their lives. Many of you may recognize his alias, as Pistone’s experiences as an undercover agent were brought to the big screen with the release of Donnie Brasco, starring Johnny Depp. Depp’s portrayal of Pistone showed not only his undercover persona but also the difficulties he had maintaining relationships with his loved ones. Now, more than 30 years later, people are still interested in Pistone’s experiences as Brasco. As recently as 2005, the National Geographic Channel premiered Inside the Mafia, a series focused on Pistone’s experiences as Brasco. While this is a more well-known example of an undercover operation, undercover work goes on all the time. Whether making drug busts, infiltrating gangs or other trafficking organizations, or conducting a sting operation on one of their own, investigators employ many of the same techniques as field researchers rely upon.

Ethical Dilemmas for Field Researchers

As you can tell, field research poses unique complications for researchers to consider prior to and while conducting their studies. Ethical issues posed by field research, particularly field research in which the researcher’s identity is not known to research subjects, include the use of deception, privacy invasion, and the lack of consent. How can a researcher obtain informed consent from research subjects if she doesn’t want anyone to know research is taking place? Is it ethical to include someone in a research study without his or her permission? When the first guidelines for human subjects research were handed down, they caused a huge roadblock for field researchers. Later, however, it was determined that social science poses less risk to human subjects, particularly those being observed in their natural setting. Because it was recognized that the risk for harm was significantly less, field researchers were allowed to conduct their studies without conditions involving informed consent. The debate remains, however, as to whether it is truly ethical to conduct research on individuals without them knowing. A related issue is confidentiality and anonymity. If researchers are living among study subjects, anonymity is impossible. One way field researchers protect their subjects in this regard is through the use of pseudonyms. A pseudonym is a false name given to someone whose identity needs to be kept secret. In writing up their study findings, researchers will use pseudonyms instead of the actual names of study subjects.

Beyond the ethical nature of the research itself, field studies may introduce other ethical dilemmas for the researcher. For example, what if the researcher, as a participating member of a group, is asked to participate in an illegal activity? This may be a nonviolent activity like vandalism or graffiti, or it may be an activity that is more sinister in nature. Researchers, as full participants, have to decide whether they would be willing to commit the crime in question. After all, if caught and arrests are made, “I was just doing research,” will not be a justification the researcher will be able to use for his participation. Even if not a full participant, a researcher may observe some activity that is unlawful. The researcher will then have to decide whether to report this activity or to keep quiet about it. If a researcher is called to testify, there could be consequences for not cooperating. Depending on what kind of group is being studied, these dilemmas may occur more or less frequently. It is important that researchers understand prior to entering the field that they may have to make difficult decisions that like the research itself, could have great costs to them personally and professionally.

RESEARCH IN THE NEWS

Field Research Hits Prime Time

In 2009, CBS aired a new reality television series, Undercover Boss, 5 in which corporate executives go “undercover” to experience life as an employee of their company. Fully disguised, the executives are quickly thrown into the day-to-day operations of their workplaces. From the co-owner of the Chicago Cubs, to the CEO of Norwegian Cruise Line, to the mayor of Cincinnati, these executives conduct field research on camera to gain a better understanding of how their company, or city administration, runs from the bottom up. Often, they find hard-working, talented employees who are deserving of recognition, which is given as the episode comes to a close and the executive reveals himself and his undercover activities to his employees. Other times, they find employees that are not so good for business. Ultimately, the experience provides these executives with awareness they did not have prior to going undercover, and they hope to be able to utilize this knowledge to position their workplaces for continued success. Not only has this show benefited the companies and other workplaces profiled, with millions of viewers each week, it has certainly brought the adventures of field research into prime time.

Examples of Field Research in Criminal Justice

If you recall from Chapter 2, Humphreys’ Tea Room Trade is an example of field research. Humphreys participated to an extent, acting as a “watchqueen” so that he could observe the sexual activities taking place in public restrooms and other public places. Another study exploring clandestine sexual activity was conducted by Styles. 6 Styles was interested in the use of gay baths, places where men seeking to have sexual relationships with other men could have relatively private encounters. While Styles was a gay man attempting to study other gay men, at the outset his intention was to be a nonparticipant observer. Having a friend vouch for him, he easily gained access into the bath and began figuring out how to best observe the scene. After observing and conducting a few interviews, Styles was approached by another man for sexual activity. Although he was resolved to only observe, this time he gave in. From this point on, he began attending another bath and collecting information as a complete participant. Styles’ writing is informative, not only for the description regarding this group’s activity, but also for the discussion he provides about his travels through the world of field research, beginning as an observer and ending as a complete participant. His writing on insider versus outsider research resulted in four main reflections for readers to consider:

There are no privileged positions of knowledge when it comes to scrutinizing human group life;

All research is conditioned by value biases and factual preconceptions about the group being studied;

Fieldwork is a process of building up images from one’s biases, preconceptions, and new information, testing these images against one’s observations and the reports of informants, and accepting, modifying, or discarding these images on the basis of what one observes and what one has been told; and

Insider and outsider researchers will differ in the ways they go about building and testing their images of the group they study. (pp. 148–150)

Reviewing the literature, one finds that field researchers often choose sexual deviance as a topic for their field studies. Tewksbury and colleagues have researched gender differences in sex shop patrons 7 and places where men have been found to have anonymous sexual encounters 8 such as sex shop theaters. 9 Another interesting field study was conducted by Ronai and Ellis. 10 For this study, Ronai acted as a complete participant, drawing from her past as a table dancer and also gaining access as an exotic dancer in a Florida strip bar for the purpose of her master’s thesis research. Building on Ronai’s experiences and her interviews with fellow dancers, the researchers examined the interactional strategies used by dancers, both on the stage and on the floor, to ensure a night where the dancers were well paid for their services. In conducting these studies, these researchers were able to expose places where many are either unwilling or afraid to go, or perhaps afraid to admit they go.

In their study of women who belong to outlaw motorcycle gangs, Hopper and Moore 11 used participant observation methods as well as interviews to better understand the biker culture and where women fit into this culture. Moore provided access, as he was once a member and president of Satan’s Dead, an outlaw biker club in Mississippi. Like Styles, Hopper and Moore discuss the challenges of conducting research among the outlaw biker population. Having to observe quietly while bikers committed acts opposite to their personal values and not being able to ask many questions or give uninvited comments were just some of the hurdles the researchers had to overcome in order to conduct their study. The male bikers were, at the least, distrustful of the researchers, and the women bikers even more so. While these challenges existed, Hopper and Moore were able to ascertain quite a bit about the female experience as relates to their role in or among the outlaw biker culture.

Ferrell has been one of the most active field researchers of our time. He is considered a founder and remains a steadfast proponent of cultural criminology, 12 a subfield of criminology that examines the intersections of cultural activities and crime. Not only did he conduct the ethnography on urban scrounging discussed at the beginning of this chapter, he has spent more than a decade in the field studying subcultural groups who defy social norms. Crossing the United States, and the globe, Ferrell has explored the social and political motivations of urban graffiti artists, 13 anarchist bicycle group activists, and outlaw radio operators, 14 just to name a few. The research conducted by Ferrell, and others discussed here, has been described as edgework, or radical ethnography. This means that, as researchers, Ferrell and others have gone to the “edge,” or the extreme, to collect information on subjects of interest. Ferrell and Hamm 15 have put together a collection of readings based on edgework, as have Miller and Tewksbury. 16 While dangerous and wrought with ethical challenges, their research has shed light on societal groups who, whether by choice or not, often reside in the shadows.

Although ethnographers have spent years studying criminal and other deviant activities, field research has not been limited to those groups. Other researchers have sought to explore what it’s like to work in criminal justice from the inside. In the 1960s, Skolnick 17 conducted field research among police officers to better understand how elements of their occupation impacted their views and behaviors. He wrote extensively about the “working personality” of police officers as shaped by their occupational environment, including the danger and alienation they face from those they are sworn to protect, and the solidarity that builds from shared experiences. Beyond law enforcement, there have also been a variety of studies focused on the prison environment. When Ted Conover, 18 a journalist interested in writing from the correctional officer perspective, was denied permission from the New York Department of Correctional Services to do a report on correctional life, he instead applied and was hired on as an actual correctional officer. In Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing, Conover offers a compelling account of his journalistic field research, which resulted in a one-year stint as a corrections officer. From his time in training until his last days working in the galleries, Conover’s experiences provide the reader a look into the challenges faced by correctional officers, stemming not only from the inmates but the correctional staff as well.

Prior to Conover’s writing, Marquart was also interested in correctional work and strategies utilized by prison guards to ensure control over the inmate population. Specifically, in the 1980s, Marquart 19 examined correctional officials’ use of physical coercion and Marquart and Crouch 20 explored their use of inmate leaders as social control mechanisms. In order to conduct this field study, Marquart, with the warden’s permission, entered a prison unit in Texas and proceeded to work as a guard from June 1981 until January 1983. He was able to work in various posts within the institution so that he could observe how prison guards interacted with inmates. Marquart not only observed the prison’s daily routine, he examined institutional records, conducted interviews, and also developed close relationships with 20 prison guards and inmate leaders, or building tenders, whom he relied on for their insider knowledge of prison life and inmate control. Based on his fieldwork, Marquait shared his findings regarding the intimidation and physical coercion used by prison guards to discipline inmates. This fieldwork also provided a fascinating look into the building tender system that was utilized as a means of social control in the Texas prison system prior to that system being discontinued.

In the early 1990s, Schmid and Jones 21 used a unique strategy to study inmate adaptation from inside the prison walls. Jones, an offender serving a sentence in a prison located in the upper midwestern region of the United States, was given permission to enroll in a graduate sociology course focused on methods of research. This course was being offered by Schmid and led to collaborative work between the two men to study prison culture. They specifically focused on the experiences of first-time, short-term inmates. With Jones acting as the complete participant and Schmid acting as the complete observer, the pair began their research covertly. While they were aware of Jones’s meeting with Schmid for purposes of the research methods course in which he was enrolled, correctional authorities and other inmates perceived Jones to be just another inmate. In the 10 months that followed, Jones kept detailed notes regarding his daily experiences and his personal thoughts about and observations of prison life. Also included in his notes was information about his participation in prison activities and his communications with other similar, first-time, short-term inmates. Once his field notes were prepared, Jones would mail them to Schmid for review. Over the course of these letters, phone calls, and intermittent meetings, new observation strategies and themes began to develop based on the observations made by Jones. Upon his release from prison and their analyzing of the initial data, Jones and Schmid reentered the prison to conduct informed interviews with 20 first-time, short-term inmates. Using these data, Schmid and Jones began to write up their findings, which focused on inmate adaptations over time, identity transformations within the prison environment, 22 and conceptions of prison sexual assault, 23 among other topics. Schmid and Jones discussed how their roles as a complete observer and a complete participant allowed them the advantage of balancing scientific objectivity and intimacy with the group under study. The unfettered access Jones had to other inmates within the prison environment as a complete participant added to the unusual nature of this study yielding valuable insight into the prison experience for this particular subset of inmates.

Case Studies

Beyond field research, case studies provide an additional means of qualitative data. While more often conducted by researchers in other disciplines, such as psychology, or by journalists, criminologists also have a rich history of case study research. In conducting case studies, researchers use in-depth interviews and oral/life history, or autobiographical, approaches to thoroughly examine one or a few illustrative cases. This method often allows individuals, particularly offenders, to tell their own story, and information from these stories, or case studies, may then be extrapolated to the larger group. The advantage is a firsthand, descriptive account of a way of life that is little understood. Disadvantages relate to the ability to generalize from what may be an atypical case and also the bias that may enter as a researcher develops a working relationship with their subject. Most examples of case studies involving criminological subjects were conducted more than 20 years ago, which may be due to criminologists’ general inclination toward more quantitative research during this time period.

The earliest case studies focused on crime topics were conducted in the 1930s. Not only was the Chicago School interested in ethnographic research, these researchers were also among the first to conduct case studies on individuals involved in criminal activities. Shaw’s The Jack Roller (1930) 24 and Sutherland’s The Professional Thief (1937) 25 are not only the oldest but also the most well-known case studies related to delinquent and criminal figures. Focused on environmental influences on behavior, Shaw profiled an inner city delinquent male, “Stanley” the “jack roller,” who explained why he was involved in delinquent behavior, specifically the crime of mugging intoxicated men. Fifty years later, Snodgrass 26 updated Shaw’s work, following up with an elderly “Stanley” at age 70. Sutherland’s case study, resulting in the publication of The Professional Thief, was based on “Chic Conwell’s” account of his personal life and professional experience surviving off of what could be stolen or conned from others. The 1970s and 1980s witnessed numerous publications based on case studies. Researchers examined organized crime figures and families, 27 heroin addicts, 28 thieves, 29 and those who fence stolen property. 30 As with participant observation research, case studies have not been relegated to offenders only. In fact, more recently the case study approach has been applied to law enforcement and correctional agencies. 33 These studies have examined activities of the New York City Police Department, 34 the New Orleans Police Department’s response in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, 35 and Rhode Island’s prison system. 36

As with field research, the case study approach can provide a deeper understanding of individuals or groups of individuals, such as crime families, who live outside of the mainstream. Case studies inform us about the motivations for why individuals or groups behave the way they do and how those experiences or activities were either beneficial or detrimental for them. The same goes for agency research. One department or agency can learn from the experiences of another department or agency. With more recent research utilizing the case study approach, it could be that this methodology will be seen more often in the criminal justice literature.

Making Critical Choices as a Field Researcher

In conducting field studies, researchers often must make decisions that impact the viability of their research. Sometimes, researchers don’t make the best choices. In the 1990s, Dr. Ansley Hamid was an esteemed anthropologist, well-known for his field research focused on the drug subculture. 31 Based on his previous success as a researcher documenting the more significant trends in drug use and addiction, he, through his position as a university professor, was awarded a multimillion-dollar federal research grant to examine heroin use on the streets of New York. It was not long after the grant was awarded, however, that Hamid was accused of misusing the funds provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, even going so far as to use the funds to purchase heroin for his own use and the use of his research subjects. While the criminal charges were eventually dismissed, Hamid paid the ultimate professional price for his behavior, particularly his use of the drug, which was documented in his handwritten field notes. 32 As of 2003, the professor was no longer connected to John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the City University of New York. In fact, Hamid is no longer working in higher education at all due to the accusations and accompanying negative publicity. Instead, he owns a candle shop in a small Brooklyn neighborhood. He does not plan to stop researching and writing though. His book, Ganja Complex: Rastafari and Marijuana, was published in 2002. This case is a prime example of what can happen when researchers cross the boundary of objectivity. Hamid’s brief experience in the shoes of a heroin user led to his ultimate downfall as an objective and respected researcher.

Chapter Summary

Qualitative research strategies allow researchers to enter into groups and places that are often considered off limits to the general public. The methods and studies discussed here provide excellent examples of the use of field research to discover motivations for the development and patterns of behavior within these groups. These qualitative endeavors offer a unique look into the lives of those who may live or work on the fringes of modern society. As it would be nearly impossible to conduct research on these groups using methods such as experiments, surveys, and formal interviews, participant observation techniques extend the ability of researchers to study activities beyond the norm by participating with and observing subjects in their natural environment and later describing in detail their experiences in the field.

Critical Thinking Questions

1. What are the advantages to using a more qualitative research method?

2. Compare and contrast the four different participant observation strategies.

3. What must a researcher consider before conducting field research?

4. What did Styles learn about conducting research as an insider versus an outsider?

5. How has the case study approach been applied to criminal justice research?

case study: In-depth analysis of one or a few illustrative cases

complete observation: A participant observation method that involves the researcher observing an individual or group from afar