Site Content

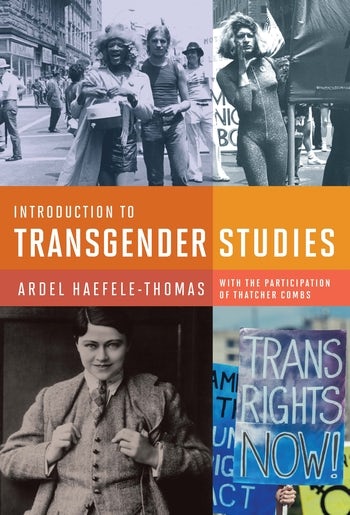

Introduction to transgender studies.

Ardel Haefele-Thomas. With the participation of Thatcher Combs. Foreword by Susan Stryker

Harrington Park Press, LLC

Pub Date: February 2019

ISBN: 9781939594273

Format: Paperback

List Price: $59.00 £50.00

Shipping Options

Purchasing options are not available in this country.

ISBN: 9781939594280

Format: E-book

List Price: $54.99 £45.00

- EPUB via the Columbia UP App

- PDF via the Columbia UP App

Named a top ten book of 2020 by the Over the Rainbow committee of the American Library Association Over the Rainbow committee of the American Library Association

I can’t imagine a better textbook introducing students to transgender studies. Ardel Haefele-Thomas lucidly explains the complexities of gender nonconformity using clear analysis, together with rich and nuanced historical examples. These are elucidated further with the delightful details they deserve. Paisley Currah, coeditor of Transgender Studies Quarterly

This is a groundbreaking textbook and significant development in transgender studies. Students will relate to all aspects of each chapter, including the personal stories, rich histories, interactive questions, inspiring trans figures, and much more. This is a must read and a truly intersectional accomplishment. Breana Bahar Hansen, City College of San Francisco and University of San Francisco

The cultural historian, queer theorist, and trans activist Ardel Haefele-Thomas has written an indispensable textbook on gender and sexuality for schools and universities. I have field-tested it with students across ethnicities and nationalities. They are invariably drawn to the well-researched multicultural histories, precise definitions of LGBTQ+, and the very personal stories of members of the community that the author has assembled. This volume will further transgender tolerance and challenge the binary as much as any single work can do. Regenia Gagnier, University of Exeter

Ardel Haefele-Thomas has done a commendable job presenting what transgender has meant up to our present moment, thereby giving the rising generation a generous gift to use as they see fit for the ongoing project of creating a less straitjacketed, more expansive sense of what a human life can be. It offers a useful place to start thinking about basic concepts like sex and gender, sexual orientation, and identity. Susan Stryker, University of Arizona, from the foreword

It makes me so honored and happy to write the introduction to Ardel Haefele-Thomas’s groundbreaking and profoundly important Introduction to Transgender Studies . A book like this matters to everybody. Jo Clifford, independent playwright, poet, and performer and former professor of theater at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, Scotland

Pragmatic, philosophical, urgent, and inclusive, Introduction to Transgender Studies is a crucial introduction to an important area of study. . . . With high-level theories that often tie into current-day examples—like bathroom discrimination and the concerning rate of violence against trans people–– Introduction to Transgender Studies is a powerful work and a constant reminder that what we learn is significant to real lives, every day. Foreword Reviews

A must-read for anyone needing an education on transgender history. Advocate

- Read Susan Stryker's foreword to Introduction to Transgender Studies

- Read Jo Clifford's introduction to Introduction to Transgender Studies

- Read a review of Introduction to Transgender Studies in Foreword Reviews

- Supplemental Powerpoints for Introduction to Transgender Studies

About the Author

- Gender and Sexuality Studies

- LGBTQIA Studies

- About Us History Jobs, Fellowships & Internships Annual & Financial Reports Racial Justice at NCTE Contact Us

- Support NCTE

- Get Updates

- Press Tips for Journalists Releases

Understanding Transgender People: The Basics

See other materials like this at our About Transgender People resource hub !

Understanding what it is like to be transgender can be hard, especially if you have never met a transgender person.

Transgender is a broad term that can be used to describe people whose gender identity is different from the gender they were thought to be when they were born. “Trans” is often used as shorthand for transgender.

To treat a transgender person with respect, you treat them according to their gender identity, not their sex at birth. So, someone who lives as a woman today is called a transgender woman and should be referred to as “she” and “her.” A transgender man lives as a man today and should be referred to as “he” and “him.”

(Note: NCTE uses both the adjectives “male” and “female” and the nouns “man” and “woman” to refer to a person’s gender identity.)

Gender identity is your internal knowledge of your gender – for example, your knowledge that you’re a man, a woman, or another gender. Gender expression is how a person presents their gender on the outside. That might include behavior, clothing, hairstyle, voice or body characteristics. Everyone has a gender identity, including cisgender – or non-transgender – people. If someone’s gender identity matches the gender they were assigned at birth, then they are cisgender , or “ci s" for short.

Sex is often used in a medical or scientific contexts . Sex is a label — male or female — that you’re assigned by a doctor at birth based on the appearance of the genitals you’re born with. It doesn’t define who you are, or what your gender identity might turn out to be.

When a person begins to live according to their gender identity, rather than the gender they were thought to be when they were born, this time period is called gender transition . Deciding to transition can take a lot of reflection. Many transgender people risk social stigma, discrimination, and harassment when they tell other people who they really are. Despite those risks, being open about one’s gender identity can be life-affirming and even life-saving.

Possible steps in a gender transition may or may not include changing your clothing, appearance, name, or the pronoun people use to refer to you (like “she,” “he,” or “they”). If they can, some people change their identification documents, like their driver’s license or passport, to better reflect their gender. And some people undergo hormone therapy or other medical procedures to change their physical characteristics and make their body match the gender they know themselves to be. All transgender people are entitled to the same dignity and respect, regardless of whether or not they have been able to take any legal or medical steps.

Some transgender people identify as neither a man nor a woman, or as a combination of male and female, and may use terms like nonbinary or genderqueer to describe their gender identity. Those who are nonbinary often prefer to be referred to as “they” and “them.”

It is important to use respectful terminology, and treat transgender people as you would treat any other person. This includes using the name the person has asked you to call them (not their old name) as well as the pronouns they want you to use. If you aren’t sure what pronouns a person uses, just ask politely.

Visit our About Transgender People resource hub for more information! Some suggestions:

For more information about transgender people generally, see Frequently Asked Questions about Transgender People .

For more information about non-binary people, see Understanding Non-Binary People .

For more information about how to be supportive of the transgender people in your life, see Supporting the Transgender People in Your Life .

Join Our Mailing List

Introduction to Transgender Studies

This is the first introductory textbook intended for transgender/trans studies at the undergraduate level. The book can also be used for related courses in LGBTQ, queer, and gender/feminist studies. It encompasses and connects global contexts, intersecting identities, historic and contemporary issues, literature, history, politics, art, and culture. Ardel Haefele-Thomas embraces the richness of intersecting identities—how race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, nation, religion, and ability have cross-influenced to shape the transgender experience and trans culture across and beyond the binary. Written by an accomplished teacher with experience in a wide variety of higher learning institutions, this new text inspires readers to explore not only contemporary transgender issues and experiences but also the global history of gender diversity through the ages. Introduction to Transgender Studies features: -A welcoming approach that creates a safe space for a wide range of students, from those who have never thought about gender issues to those who identify as transgender, trans, nonbinary, agender, and/or gender expansive. -Writings from the Community essays that relate the chapter theme to the lived experiences of trans and LGB people and allies from different parts of the world. -Key concepts, film and media suggestions, topics for discussion, activities, and ideas for writing and research to engage students and serve as a review at exam time. -Instructors’ resources that will be available that include key teaching points with discussion questions, activities, research projects, tips for using the media suggestions, PowerPoint presentations, and sample syllabi for various course configurations. Intended for introductory transgender, LGBTQ+, or gender studies courses through upper-level electives related to the expanding field of transgender studies, this text has been successfully class-tested in community colleges and public and private colleges and universities.

Related Readings:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Introduction : Trans/Feminisms

Susan Stryker is associate professor of gender and women's studies and director of the Institute for LGBT Studies at the University of Arizona and general coeditor of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly.

Talia M. Bettcher is a professor of philosophy at California State University, Los Angeles, and she currently serves as chair of the Department of Philosophy.

- Standard View

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Susan Stryker , Talia M. Bettcher; Introduction : Trans/Feminisms . TSQ 1 May 2016; 3 (1-2): 5–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-3334127

Download citation file:

- Reference Manager

This special issue of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly on trans/feminisms profiles the remarkable breadth of work being carried on at the intersections of transgender and feminist scholarship, activism, and cultural production, both in the United States as well as in many countries around the world. It emerged from discussions within the journal's editorial board about how to respond—if at all—to the April 2014 publication of Sheila Jeffreys's Gender Hurts: A Feminist Analysis of the Politics of Transgenderism . As feminist scholars ourselves, we were concerned that Jeffreys's work, published by a leading academic publisher and written by a well-known feminist activist and academic who has expressed hostility toward trans issues since the 1970s, might breathe new life into long-standing misrepresentations of individual trans experience and collective trans history and politics that have been circulated for decades by Mary Daly, Germaine Greer, Robin Morgan, Janice Raymond, and like-minded others. We wanted to trouble the transmission of those ideas—but how best to do so?

We were concerned as well that Jeffreys's book would add momentum to a wave of antitransgender discourse that has recently been gaining greater strength in certain corners of academia, some feminist circles, and in pockets of the mainstream liberal press.

We understand the current wave of antitransgender rhetoric to be in reaction to recent gains for transgender human and civil rights, a concomitant rise in visibility for transgender issues, and the vague sense that public opinion is shifting, however haltingly or unevenly, toward greater support of trans lives. Those of us who are old enough remember a similar wave in the early 1990s when the contemporary queer and trans movements first emerged in the United States; those of us who are older still, or who have studied our history, can speak of other antitransgender backlashes in the early 1970s—when the women's movement, gay liberation, and the sexual revolution were all accelerating, and the role of trans people in these movements became a divisive issue. Simply put, we understand there to be a relationship between antitransgender scholarship and the concrete manifestation of antitransgender politics, such as the well-known controversy surrounding trans women's exclusion from the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival that had raged beginning with Nancy Jean Burkholder's forcible expulsion in 1991 until 2015, the final year of the festival.

Whatever the cause, over the past few years we have indeed witnessed an escalating struggle over public speech, perhaps most vitriolic in the United Kingdom, in which transgender opposition to what many consider harmful speech from some feminists is perceived by others as an abrogation of the right to free speech by feminists hostile to transgender issues—a debate that engages arguments similar to those advanced regarding what some consider to be the disparagement of Islam within the context of what others consider to be protected political speech in the West. We have seen liberal publications such as the New Yorker magazine and the Guardian newspaper run features that characterize transgender people as censorious zealots when they protest the animus directed against them by some feminists. We have seen more than three dozen well-known feminists—including novelist Marge Piercy, black cultural studies scholar Michele Wallace, French feminist icon Christine Delphy, and radical feminist foremother Ti-Grace Atkinson—sign an open letter titled “Forbidden Discourse: The Silencing of Feminist Criticism of ‘Gender’” ( Hanisch 2013 ) that complains, as does Jeffreys's book, that the very concept of gender (which they see as a depoliticizing substitution for the concept of sexism) is an ideological smokescreen that masks the persistence of male supremacy and oppression of women by men, and assert that “transgender” is the nonsensical and pernicious outcome of this politically spurious set of beliefs (a stance that places them in odd congruence with the conservative Christian position, espoused by the last three popes, that opposes the “ideology of gender,” which they have seen as offering support for unnatural interventions into reproductive biology, improper social roles for men and women, and assaults on heteronormative family life [ McElwee 2015 ]). More recently, in the wake of the Caitlyn Jenner media barrage, the New York Times published an op-ed piece by Elinor Burkett, “What Makes a Woman?,” in which the author, a feminist filmmaker, assumed she was entitled to answer that question in a way that prevented transgender women from being included in her definition—for which feminist biologist Anne Fausto-Sterling, author of the widely taught Sexing the Body , unexpectedly tweeted her enthusiastic support.

Given the broader context of a backlash against recent transgender gains among some feminists for which Jeffreys's Gender Hurts might conceivably become a standard-bearer or cause célèbre, it seemed important for TSQ to somehow address that book and thereby intervene in the conversation about the vexed relationship between transgender and feminist movements, communities, and identities. We asked the editorial board: should the book be critiqued, reviewed, editorialized against, or simply ignored?

After we actually read Jeffreys's text, the prevailing opinion was that the work lacked scholarly merit (a view shared by the few reviews that the book has garnered in academic journals). It completely ignores the question of transgender agency—that is, of trans people making conscious, informed choices about the best way to live their own embodied lives—and instead represents trans people as having no will of their own; for Jeffreys, they serve only as tools or victims of a patriarchal conspiracy to destroy feminism and harm girls and women. Rather than review or editorialize against Gender Hurts , the board suggested, we should instead publish a special issue on feminist transgender scholarship that recontextualizes and reframes the terms of the conflict. Rather than cede the label feminist to a minority of feminists who hold a particular set of negative opinions about trans people, and rather than reducing all transgender engagement with feminism to the strategy embraced by some trans people of vigorously challenging certain forms of antitransgender feminist speech, we should instead demonstrate the range and complexity of trans/feminist relationships. Rather than fighting a battle on the same terrain that has been contested in Anglo-US feminist movements and in English-language feminist literature for decades, we should contextualize the battle lines within a far richer and more complicated world history of trans/feminist engagement. As white North American anglophone feminist scholars, we see promoting a more global perspective on trans/feminisms as being particularly important for decentering the linguistic, cultural, racial, and national hegemony of anglocentric trans studies and politics. So that's what we set out to do.

In Trans/Feminisms , a special double-issue of TSQ , we will explore feminist work taking place within trans studies; trans and genderqueer activism; cultural production in trans, genderqueer, and nonbinary gender communities; and in communities and cultures across the globe that find the modern Western gender system alien and ill-fitting to their own self-understanding. Simultaneously, we want to explore as well the ways in which trans issues are addressed within broader feminist and women's organizations and social movements around the world. We want this issue to expand the discussion beyond the familiar and overly simplistic dichotomy often drawn between an exclusionary transphobic feminism and an inclusive trans-affirming feminism. We seek to highlight the many feminisms that are trans inclusive and that affirm the diversity of gender expression, in order to document the reality that feminist transphobia is not universal nor is living a trans life, or a life that contests the gender binary, antithetical to feminist politics. How are trans, genderqueer, and non-binary issues related to feminist movements today? What kind of work is currently being undertaken in the name of trans/feminism? What new paradigms and visions are emerging? What issues still need to be addressed? Central to this project is the recognition that multiple oppressions (not just trans and sexist oppressions) intersect, converge, overlap, and sometimes diverge in complex ways, and that trans/feminist politics cannot restrict itself to the domain of gender alone.

We could not be more pleased with the response to this CFP, or with the thirty-four feature article authors from seventeen different countries we have been able to publish.

We do not have the misguided notion that it is their maleness, per se—i.e., their biological maleness—that makes them what they are. As Black women we find any type of biological determinism a particularly dangerous and reactionary basis upon which to build a politic. We must also question whether Lesbian separatism is an adequate and progressive political analysis and strategy, even for those who practice it, since it so completely denies any but the sexual sources of women's oppression, negating the facts of class and race. ( Combahee River Collective [1977] 1983 )

In foregrounding the necessity of attending to class and race as well as sex and gender, intersectional feminism raised the question of whether “woman” itself was a sufficient analytical category capable of accounting for the various forms of oppression that women can experience in a sexist society, which in turn opened the question of whether it was sufficient to talk about sexual “difference” in the singular, between men and women, or whether instead feminism called for an account of multiple “differences” of embodied personhood along many different but interrelated axes. This intersectional version of feminism laid the foundation for transfeminist theories and practices in the 1990s and subsequently. Another clear theme to emerge was the importance of queer and poststructuralist approaches to gender and feminism that enabled a more varied understanding of the complex and ever-shifting processes through which identity, embodiment, sexuality, and gender can be configured.

Clear, too, is the recognition that transfeminist perspectives have a decades-long history within intersectional feminisms and were crucial to early formulations of transgender studies. As one contribution to this issue of TSQ notes, trans issues played a role in the life of Dr. Pauli Murray, a black gender-nonconforming woman who explored hormonal masculinization in the 1940s, and whose legal activism in the 1950s and 1960s helped lay a conceptual foundation for intersectional feminist theory; other contributors note that trans people played active roles in second-wave feminist groups in the 1960s and 1970s, many of which were actively welcoming of trans people.

Angela Douglas, for example, founded the Transsexual/Transvestite Activist Organization (TAO) in 1970 in Los Angeles, while “crashing” for a few months at the Women's Center, where she immersed herself in the feminist literature in the center's library, attended classes, and participated in the Lesbian Feminist organization that met in the building—noting (with her characteristic self-aggrandizement), “To some, I was a walking monument to the women's movement, a man who had voluntarily given up male privilege to be a woman—and was now fighting for women's rights” ( Douglas 1983 : 31). In 1973, when Sylvia Rivera—Stonewall veteran and cofounder of the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR)—fought her way onto the stage of the Christopher Street Liberation Day rally in New York, after having first been blocked by antitrans lesbian feminists and their gay male supporters, she spoke defiantly of her own experiences of being raped and beaten by predatory heterosexual men she had been incarcerated with, and of the work that she and others in STAR were doing to support other incarcerated trans women. She chastised the crowd for not being more supportive of trans people who experienced exactly the sort of gendered violence that feminists typically decried and asserted, with her own characteristic brio, that “the women who have tried to fight for their sex changes, or to become women, are the women's liberation” ( Rivera 1973 ). The point here is not to debate how well or how deeply early trans radicals like Douglas and Rivera understood or engaged with feminism and the women's movement, but rather simply to document that second-wave feminist spaces in the United States could be inclusive of trans activism, and that radical trans activism drew upon tenets of the women's movement, perhaps even more than it did from gay liberation rhetoric.

Suzan Cooke, one of the first peer counselors at the path-breaking National Transsexual Counseling Unit established in San Francisco in 1968, moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1970s and became a staff photographer at the Lesbian Tide , a lesbian feminist publication. Early US female-to-male community organizer Lou Sullivan ([1974] 2006 ) tackled feminist transphobia head-on in his 1974 article “A Transvestite Answers a Feminist,” while Margo Schulter ( 1974 , 1975a , 1975b , 1975c ), a self-proclaimed lesbian feminist transsexual living in Boston in the late 1960s and early 1970s, penned a series of remarkably astute articles in the gay and feminist press on what she called “the lesbian/transsexual misunderstanding.” As the next decade dawned, Carol Riddell, a feminist transsexual woman and radical professor of sociology at Lancaster University, authored Divided Sisterhood , published in 1980 , the first feminist rebuttal of Janice Raymond's notorious 1979 publication The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male . Riddell's leftist scholarship—such as a 1972 conference paper titled “Transvestism and the Tyranny of Gender,” which characterized the two-gender system as an oppressive feature of capitalism—influenced Richard Ekins and David King, two of the leading academic researchers of transgender phenomena in the 1980s and 1990s ( Gender Variance Who's Who 2008 ).

It is, however, Sandy Stone's “Posttranssexual Manifesto” ( [1992] 2006 ) often credited as the founding document of contemporary trans studies, that most fully activates the protean relationship between trans and feminist theorizing. Written in response to the trans-exclusionary radical feminist activism that resulted in Stone's leaving the Olivia women's music collective where she had been working as a recording engineer in the 1970s, Stone's manifesto integrated many different strands of feminist, queer, and trans analysis into a potent conceptual tool kit that remains vital for the field today. The manifesto, first published in 1991, was originally presented at “Other Voices, Other Worlds: Questioning Gender and Ethnicity,” a conference on intersectional feminism held in 1988 at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where Stone was then a doctoral student in the history of consciousness at a time when that program boasted such faculty members as Angela Davis, Gloria Anzaldúa, Donna Haraway, and Teresa de Lauretis. It bears mentioning that Stone's formulation of a “posttranssexual” politics took shape in the same milieu that generated Anzaldúa's “new mestiza,” Haraway's “cyborg,” and de Lauretis's coinage of queer theory . Like its contemporaneous figurations, Stone's “posttranssexual” offered a compelling new way to think in the interstices of gender, embodiment, and sexuality.

Since the early 1990s, a distinct body of transfeminist literature has taken shape. Stone's manifesto provided the impetus for Davina Anne Gabriel's TransSisters: A Journal of Transsexual Feminism (1993–95), which explored the underarticulated middle ground between medicalized transsexuality and radical feminism that Stone's essay had pointed toward. Other contemporary ’zines expressing similar transfeminist perspectives include Anne Ogborne's Rites of Passage (1991–92) and Gail Sondergaard's TNT: Transsexual News Telegraph (1992–2000), both from San Francisco; and Mirha-Soleil Ross and Xanthra McKay's Gendertrash , from Montreal (1992–95). The first significant wave of peer-reviewed transgender studies scholarship to wash ashore in academia, in 1998, in special issues of such journals as GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies , Social Text , Sexualities , and Velvet Light-Trap , also produced a special issue of the British feminist Journal of Gender Studies (guest edited by Stephen Whittle). US activists Diana Courvant and Emi Koyama are generally credited with coining the term transfeminism itself circa 1992, in the context of their intersectional work on trans, intersex, disability, and survivorship of sexual violence. Although various other writers were using the term by the late 1990s, including Patrick Califia and Jessica Xavier, it was Koyama's “Transfeminist Manifesto,” published on her Transfeminism.org website in 2001, that gave it a greater reach. Her earlier Whose Feminism Is It Anyway? (2000) is also of particular note in its explicit discussion of the intersections of race and class in the debates over the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival.

The first anthology of explicitly transfeminist writing, Krista Scott-Dixon's Trans/Forming Feminisms: Trans/feminist Voices Speak Out , was published in 2006 , a year before Julia Serano's influential Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity ( 2007 ) brought transfeminist concepts into even wider circulation. Since then, at least three special issues of leading English-language feminist journals have engaged with trans studies. In 2008 , WSQ published “Trans-” (edited by Paisley Currah, Lisa Jean Moore, and Susan Stryker); in 2009 , Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy published “Transgender Studies and Feminism: Theory, Politics, and Gender Realities” (edited by Talia Bettcher and Ann Garry); and in 2011 , Matt Richardson and Leisa Meyers, on behalf of the editorial collective of Feminist Studies , issued “Race and Transgender Studies.” More recently, A. Finn Enke's 2013 Lambda Literary Award–winning edited volume, Transfeminist Perspectives in and beyond Transgender and Gender Studies (Temple University Press) has been reaching students in feminist classrooms throughout the anglophone academy. Beyond the United States, important transfeminist writings include Ray Tanaka's work on the intersection of trans and feminist concerns in antidomestic violence activism in Japan, Toransujendā feminizumu ( Transgender Feminism ; 2006 ); Miriam Solá and Elena Urko's Transfeminismos: Epistemes, fricciones y flujos ( Transfeminisms: Epistemes, Frictions, and Flows ; 2013 ), and Jaqueline Gomes de Jesus et al., Transfeminismo: Teorias e práticas ( Transfeminism: Theory and Practice ; 2014 ).

In English, transfeminism , written all as one word, usually connotes a “third wave” feminist sensibility that focuses on the personal empowerment of women and girls, embraced in an expansive way that includes trans women and girls. It is adept at online activism and makes sophisticated use of social media and Internet technologies; it typically promotes sex positivity (such as support for kink and fetish practices, sex-worker rights, and opposition to “slut shaming”) and espouses affirming attitudes toward stigmatized body types (such as fat, disabled, racialized, or trans bodies); it often analyzes and interprets pop cultural texts and artifacts and critiques consumption practices, particularly as they relate to feminine beauty culture. In Spanish and Latin American contexts, transfeminismo carries many of these connotations as well, but it has also become closely associated with the “postporn” performance art scene, squatter subcultures, antiausterity politics, post- Indignado and post-Occupy “leaderless revolt” movements, and support for immigrants, refugees, and the undocumented; in some contexts, it is understood as a substitute for, and successor to, an anglophone queer theory and activism deemed too disembodied, and too linguistically foreign, to be culturally relevant. Transfeminismo , rather than imagining itself as the articulation of a new form of postidentitarian sociality (as queer did), is considered a polemical appropriation of, and a refusal of exclusion from, existing feminist frameworks that remain vitally necessary; the trans- prefix not only signals the inclusion of trans* people as political subjects within feminism but also performs the lexical operation of attaching to, dynamizing, and transforming an existing entity, pulling it in new directions, bringing it into new arrangements with other entities.

The “Trans/Feminisms” issue of TSQ includes a number of articles by authors who consider themselves transfeminist in the ways just described and that chronicle self-styled transfeminist practices and theories in the United States, Brazil, Ecuador, Mexico, Spain, France, Russia, and Turkey. By choosing the forward slash (/) to mark a break between the two halves of the neologistic portmanteau transfeminism , however, we intend to make space for a wider range of work that explores the many ways that transgender and feminist work can relate to one another. Some pieces are historical, looking back at trans/feminist interactions over the past half-century, in Italy as well as the United States. Others critique the contemporary upsurge of transphobia in some feminist circles, such as Sara Ahmed's analysis of the “no-platforming” debate in the United Kingdom. Still others chart the tentative emerging dialogs between established feminist cultures and newer transgender perspectives in such locations as francophone Canada, South Korea, and mainland China. Transfeminist heuristic lenses are applied to feminist science studies in the biological sciences, the relevance of the new materialism for trans studies, khwaja sira activism in Pakistan, radical hip-hop in Germany, grass-roots health activism in the United States and Latin America, questions of assisted reproduction for trans women of color in the United States, decolonial readings of gender diversity in South America, and the resurgence of two-spirit perspectives on erotic sovereignty. We make room as well for more disciplinary sorts of work, such as a sociological account of feminist attitudes among a cohort of trans men in the United States; whimsical cartoon artwork; work that offers personal reflections on the authors' participation in, or experience of, trans and feminist scholarship and activism; and documents of transfeminist activism.

Finally, we also include interviews—both original and archival—that help round out the scope of trans/feminisms we wish to represent. Tommi Avicolli Mecca discusses the history of the Radical Queens Collective in Philadelphia in the 1970s and their relationship with the lesbian separatist DYKETACTICS group, and long-time Los Angeles butch, lesbian, and feminist activist Jeanne Córdova recalls the 1973 Lesbian Conference that witnessed the controversy surrounding Beth Elliott's performance and discusses the trans-inclusive politic of the Lesbian Tide . We are also pleased to include an edited version of a 1995 interview with Sandy Stone, portions of which originally appeared in Wired magazine ( Stryker 1996 ), that help document the social, political, and intellectual contexts of early transfeminist theorizing.

In bringing together this unprecedented collection of transnational trans/feminist work, we hope to counter the most vituperative and sadly persistent forms of feminist transphobia by showcasing the truly inspiring work currently being undertaken around the world under the banner of transfeminism, as well as by documenting the already long history of transfeminist activism. We hope as well to foster even more radical visions of a social order that makes room for all of us regardless of race, class, sex, gender, sexuality, ability, language, nation, or any other status that now renders us vulnerable to violence and injustice. Transfeminism is a part, but only a part, of this larger struggle.

Data & Figures

- Previous Issue

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Advertisement

Supplements

Citing articles via, email alerts, related articles, related topics, related book chapters, affiliations.

- About TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly

- Editorial Board

- For Authors

- Rights and Permissions Inquiry

- Online ISSN 2328-9260

- Print ISSN 2328-9252

- Copyright © 2024

- Duke University Press

- 905 W. Main St. Ste. 18-B

- Durham, NC 27701

- (888) 651-0122

- International

- +1 (919) 688-5134

- Information For

- Advertisers

- Book Authors

- Booksellers/Media

- Journal Authors/Editors

- Journal Subscribers

- Prospective Journals

- Licensing and Subsidiary Rights

- View Open Positions

- email Join our Mailing List

- catalog Current Catalog

- Accessibility

- Get Adobe Reader

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

117 Transgender Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Transgender issues have become increasingly prominent in recent years, as society grapples with questions of identity, equality, and acceptance. For students looking to explore these topics in their academic writing, we have compiled a list of 117 transgender essay topic ideas and examples to spark inspiration and encourage thoughtful analysis.

- The history of transgender rights movements

- The impact of media representation on transgender individuals

- Transgender healthcare access and disparities

- Transgender discrimination in the workplace

- The intersectionality of race and transgender identity

- The role of religion in shaping attitudes towards transgender individuals

- Transgender youth and mental health

- Transgender representation in literature and film

- The experiences of transgender individuals in the military

- Transgender rights and legal protections in different countries

- Transgender activism and advocacy

- The effects of hormone therapy on transgender individuals

- Transgender identity in non-binary and genderqueer communities

- Transgender athletes and the debate over inclusion in sports

- The portrayal of transgender characters in popular culture

- Transgender parenting and family dynamics

- Transgender identity and mental health

- The relationship between gender dysphoria and transgender identity

- Transgender individuals in the criminal justice system

- Transgender representation in the arts

- The impact of social media on transgender visibility and activism

- Transgender health disparities in marginalized communities

- Transgender identity and the prison system

- Transgender individuals in the foster care system

- The role of education in promoting transgender acceptance and understanding

- Transgender identity and access to public facilities

- Transgender rights and the political landscape

- Transgender identity and homelessness

- The experiences of transgender individuals in healthcare settings

- Transgender identity and aging

- Transgender representation in the fashion industry

- The portrayal of transgender individuals in reality TV shows

- Transgender identity and sex work

- Transgender identity and military service

- Transgender representation in the music industry

- The experiences of transgender individuals in the workplace

- Transgender identity and body image

- Transgender identity and access to reproductive healthcare

- The impact of conversion therapy on transgender individuals

- Transgender identity and self-acceptance

- Transgender representation in video games

- The experiences of transgender individuals in the healthcare system

- Transgender identity and substance abuse

- Transgender identity and disability

- Transgender representation in the beauty industry

- The experiences of transgender individuals in the criminal justice system

- Transgender identity and the foster care system

These essay topics cover a wide range of issues related to transgender identity, rights, and experiences, providing ample opportunities for exploration and analysis. Whether you are interested in the social, political, or cultural dimensions of transgender issues, there is sure to be a topic on this list that sparks your interest and inspires your academic writing. By delving into these complex and compelling topics, you can contribute to a deeper understanding of transgender issues and help promote greater acceptance and equality for transgender individuals everywhere.

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

The Experiences, Challenges and Hopes of Transgender and Nonbinary U.S. Adults

Findings from pew research center focus groups, table of contents, identity and the gender journey, navigating gender day-to-day, seeking medical care for gender transitions , connections with the broader lgbtq+ community, policy and social change.

- Focus groups

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

- Panel recruitment

- Sample design

- Questionnaire development and testing

- Data collection protocol

- Data quality checks

- Acknowledgments

Introduction

Transgender and nonbinary people have gained visibility in the U.S. in recent years as celebrities from Laverne Cox to Caitlyn Jenner to Elliot Page have spoken openly about their gender transitions. On March 30, 2022, the White House issued a proclamation recognizing Transgender Day of Visibility , the first time a U.S. president has done so.

More recently, singer and actor Janelle Monáe came out as nonbinary , while the U.S. State Department and Social Security Administration announced that Americans will be allowed to select “X” rather than “male” or “female” for their sex marker on their passport and Social Security applications.

At the same time, several states have enacted or are considering legislation that would limit the rights of transgender and nonbinary people . These include bills requiring people to use public bathrooms that correspond with the sex they were assigned at birth, prohibiting trans athletes from competing on teams that match their gender identity, and restricting the availability of health care to trans youth seeking to medically transition.

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that 1.6% of U.S. adults are transgender or nonbinary – that is, their gender is different from the sex they were assigned at birth. This includes people who describe themselves as a man, a woman or nonbinary, or who use terms such as gender fluid or agender to describe their gender. While relatively few U.S. adults are transgender, a growing share say they know someone who is (44% today vs. 37% in 2017 ). One-in-five say they know someone who doesn’t identify as a man or woman.

In order to better understand the experiences of transgender and nonbinary adults at a time when gender identity is at the center of many national debates, Pew Research Center conducted a series of focus groups with trans men, trans women and nonbinary adults on issues ranging from their gender journey, to how they navigate issues of gender in their day-to-day life, to what they see as the most pressing policy issues facing people who are trans or nonbinary. This is part of a larger study that includes a survey of the general public on their attitudes about gender identity and issues related to people who are transgender or nonbinary.

The terms transgender and trans are used interchangeably throughout this essay to refer to people whose gender is different from the sex they were assigned at birth. This includes, but is not limited to, transgender men (that is, men who were assigned female at birth) and transgender women (women who were assigned male at birth).

Nonbinary adults are defined here as those who are neither a man nor a woman or who aren’t strictly one or the other. While some nonbinary focus group participants sometimes use different terms to describe themselves, such as “gender queer,” “gender fluid” or “genderless,” all said the term “nonbinary” describes their gender in the screening questionnaire. Some, but not all, nonbinary participants also consider themselves to be transgender.

References to gender transitions relate to the process through which trans and nonbinary people express their gender as different from social expectations associated with the sex they were assigned at birth. This may include social, legal and medical transitions. The social aspect of a gender transition may include going by a new name or using different pronouns, or expressing their gender through their dress, mannerisms, gender roles or other ways. The legal aspect may include legally changing their name or changing their sex or gender designation on legal documents or identification. Medical care may include treatments such as hormone therapy, laser hair removal and/or surgery.

References to femme indicate feminine gender expression. This is often in contrast to “masc,” meaning masculine gender expression.

Cisgender is used to describe people whose gender matches the sex they were assigned at birth and who do not identify as transgender or nonbinary.

Misgendering is defined as referring to or addressing a person in ways that do not align with their gender identity, including using incorrect pronouns, titles (such as “sir” or “ma’am”), and other terms (such as “son” or “daughter”) that do not match their gender.

References to dysphoria may include feelings of distress due to the mismatch of one’s gender and sex assigned at birth, as well as a diagnosis of gender dysphoria , which is sometimes a prerequisite for access to health care and medical transitions.

The acronym LGBTQ+ refers to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (or, in some cases, questioning), and other sexual orientations or gender identities that are not straight or cisgender, such as intersex, asexual or pansexual.

Pew Research Center conducted this research to better understand the experiences and views of transgender and nonbinary U.S. adults. Because transgender and nonbinary people make up only about 1.6% of the adult U.S. population, this is a difficult population to reach with a probability-based, nationally representative survey. As an alternative, we conducted a series of focus groups with trans and nonbinary adults covering a variety of topics related to the trans and nonbinary experience. This allows us to go more in-depth on some of these topics than a survey would typically allow, and to share these experiences in the participants’ own words.

For this project, we conducted six online focus groups, with a total of 27 participants (four to five participants in each group), from March 8-10, 2022. Participants were recruited by targeted email outreach among a panel of adults who had previously said on a survey that they were transgender or nonbinary, as well as via connections through professional networks and LGBTQ+ organizations, followed by a screening call. Candidates were eligible if they met the technology requirements to participate in an online focus group and if they either said they consider themselves to be transgender or if they said their gender was nonbinary or another identity other than man or woman (regardless of whether or not they also said they were transgender). For more details, see the Methodology .

Participants who qualified were placed in groups as follows: one group of nonbinary adults only (with a nonbinary moderator); one group of trans women only (with a trans woman moderator); one group of trans men only (with a trans man moderator); and three groups with a mix of trans and nonbinary adults (with either a nonbinary moderator or a trans man moderator). All of the moderators had extensive experience facilitating groups, including with transgender and nonbinary participants.

The participants were a mix of ages, races/ethnicities, and were from all corners of the country. For a detailed breakdown of the participants’ demographic characteristics, see the Methodology .

The findings are not statistically representative and cannot be extrapolated to wider populations.

Some quotes have been lightly edited for clarity or to remove identifying details. In this essay, participants are identified as trans men, trans women, or nonbinary adults based on their answers to the screening questionnaire. These words don’t necessarily encompass all of the ways in which participants described their gender. Participants’ ages are grouped into the following categories: late teens; early/mid/late 20s, 30s and 40s; and 50s and 60s (those ages 50 to 69 were grouped into bigger “buckets” to better preserve their anonymity).

These focus groups were not designed to be representative of the entire population of trans and nonbinary U.S. adults, but the participants’ stories provide a glimpse into some of the experiences of people who are transgender and/or nonbinary. The groups included a total of 27 transgender and nonbinary adults from around the U.S. and ranging in age from late teens to mid-60s. Most currently live in an urban area, but about half said they grew up in a suburb. The groups included a mix of White, Black, Hispanic, Asian and multiracial American participants. See Methodology for more details.

Most focus group participants said they knew from an early age – many as young as preschool or elementary school – that there was something different about them, even if they didn’t have the words to describe what it was. Some described feeling like they didn’t fit in with other children of their sex but didn’t know exactly why. Others said they felt like they were in the wrong body.

“I remember preschool, [where] the boys were playing on one side and the girls were playing on the other, and I just had a moment where I realized what side I was supposed to be on and what side people thought I was supposed to be on. … Yeah, I always knew that I was male, since my earliest memories.” – Trans man, late 30s

“As a small child, like around kindergarten [or] first grade … I just was [fascinated] by how some people were small girls, and some people were small boys, and it was on my mind constantly. And I started to feel very uncomfortable, just existing as a young girl.” – Trans man, early 30s

“I was 9 and I was at day camp and I was changing with all the other 9-year-old girls … and I remember looking at everybody’s body around me and at my own body, and even though I was visually seeing the exact shapeless nine-year-old form, I literally thought to myself, ‘oh, maybe I was supposed to be a boy,’ even though I know I wasn’t seeing anything different. … And I remember being so unbothered by the thought, like not a panic, not like, ‘oh man, I’m so different, like everybody here I’m so different and this is terrible,’ I was like, ‘oh, maybe I was supposed to be a boy,’ and for some reason that exact quote really stuck in my memory.” – Nonbinary person, late 30s

“Since I was little, I felt as though I was a man who, when they were passing out bodies, someone made a goof and I got a female body instead of the male body that I should have had. But I was forced by society, especially at that time growing up, to just make my peace with having a female body.” – Nonbinary person, 50s

“I’ve known ever since I was little. I’m not really sure the age, but I just always knew when I put on boy clothes, I just felt so uncomfortable.” – Trans woman, late 30s

“It was probably as early as I can remember that I wasn’t like my brother or my father [and] not exactly like my girl cousins but I was something else, but I didn’t know what it was.” – Nonbinary person, 60s

Many participants were well into adulthood before they found the words to describe their gender. For those focus group participants, the path to self-discovery varied. Some described meeting someone who was transgender and relating to their experience; others described learning about people who are trans or nonbinary in college classes or by doing their own research.

“I read a Time magazine article … called ‘Homosexuality in America’ … in 1969. … Of course, we didn’t have language like we do now or people were not willing to use it … [but] it was kind of the first word that I had ever heard that resonated with me at all. So, I went to school and I took the magazine, we were doing show-and-tell, and I stood up in front of the class and said, ‘I am a homosexual.’ So that began my journey to figure this stuff out.” – Nonbinary person, 60s

“It wasn’t until maybe I was 20 or so when my friend started his transition where I was like, ‘Wow, that sounds very similar to the emotions and challenges I am going through with my own identity.’ … My whole life from a very young age I was confused, but I didn’t really put a name on it until I was about 20.” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

“I knew about drag queens, but I didn’t know what trans was until I got to college and was exposed to new things, and that was when I had a word for myself for the first time.” – Trans man, early 40s

“I thought that by figuring out that I was interested in women, identifying as lesbian, I thought [my anxiety and sadness] would dissipate in time, and that was me cracking the code. But then, when I got older, I left home for the first time. I started to meet other trans people in the world. That’s when I started to become equipped with the vocabulary. The understanding that this is a concept, and this makes sense. And that’s when I started to understand that I wasn’t cisgender.” – Trans man, early 30s

“When I took a human sexuality class in undergrad and I started learning about gender and different sexualities and things like that, I was like, ‘oh my god. I feel seen.’ So, that’s where I learned about it for the first time and started understanding how I identify.” – Nonbinary person, mid-20s

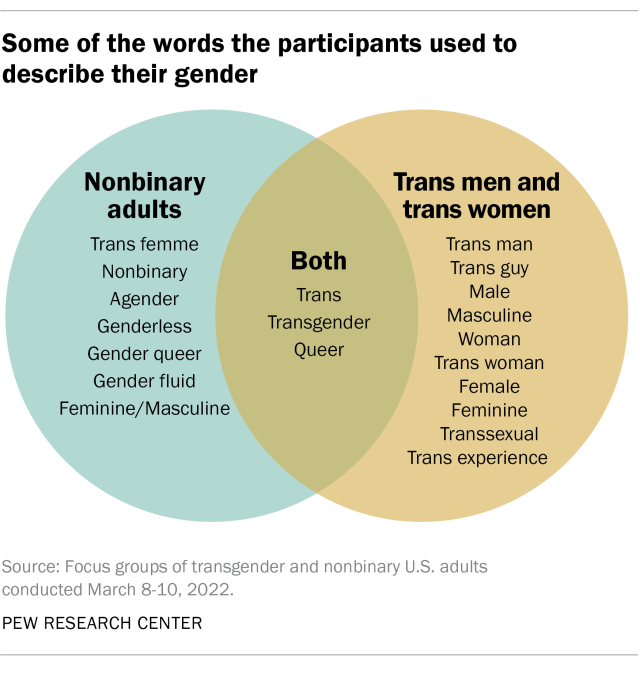

Focus group participants used a wide range of words to describe how they see their gender. For many nonbinary participants, the term “nonbinary” is more of an umbrella term, but when it comes to how they describe themselves, they tend to use words like “gender queer” or “gender fluid.” The word “queer” came up many times across different groups, often to describe anyone who is not straight or cisgender. Some trans men and women preferred just the terms “man” or “woman,” while some identified strongly with the term “transgender.” The graphic below shows just some of the words the participants used to describe their gender.

The way nonbinary people conceptualize their gender varies. Some said they feel like they’re both a man and a woman – and how much they feel like they are one or the other may change depending on the day or the circumstance. Others said they don’t feel like they are either a man or a woman, or that they don’t have a gender at all. Some, but not all, also identified with the term transgender.

“I had days where I would go out and just play with the boys and be one of the boys, and then there would be times that I would play with the girls and be one of the girls. And then I just never really knew what I was. I just knew that I would go back and forth.” – Nonbinary person, mid-20s

“Growing up with more of a masculine side or a feminine side, I just never was a fan of the labelling in terms of, ‘oh, this is a bit too masculine, you don’t wear jewelry, you don’t wear makeup, oh you’re not feminine enough.’ … I used to alternate just based on who I felt I was. So, on a certain day if I felt like wearing a dress, or a skirt versus on a different day, I felt like wearing what was considered men’s pants. … So, for me it’s always been both.” – Nonbinary person, mid-30s

“I feel like my gender is so amorphous and hard to hold and describe even. It’s been important to find words for it, to find the outlines of it, to see the shape of it, but it’s not something that I think about as who I am, because I’m more than just that.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“What words would I use to describe me? Genderless, if gender wasn’t a thing. … I guess if pronouns didn’t exist and you just called me [by my name]. That’s what my gender is. … And I do use nonbinary also, just because it feels easier, I guess.” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

Some participants said their gender is one of the most important parts of their identity, while others described it as one of many important parts or a small piece of how they see themselves. For some, the focus on gender can get tiring. Those who said gender isn’t a central – or at least not the most central – part of their identity mentioned race, ethnicity, religion and socioeconomic class as important aspects that shape their identity and experiences.

“It is tough because [gender] does affect every factor of your life. If you are doing medical transitioning then you have appointments, you have to pay for the appointments, you have to be working in a job that supports you to pay for those appointments. So, it is definitely integral, and it has a lot of branches. And it deals with how you act, how you relate to friends, you know, I am sure some of us can relate to having to come out multiple times in our lives. That is why sexuality and gender are very integral and I would definitely say I am proud of it. And I think being able to say that I am proud of it, and my gender, I guess is a very important part of my identity.” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

“Sometimes I get tired of thinking about my gender because I am actively [undergoing my medical transition]. So, it is a lot of things on my mind right now, constantly, and it sometimes gets very tiring. I just want to not have to think about it some days. So, I would say it’s, it’s probably in my top three [most important parts of my identity] – parent, Black, queer nonbinary.” – Nonbinary person, mid-40s

“I live in a town with a large queer and trans population and I don’t have to think about my gender most of the time other than having to come out as trans. But I’m poor and that colors everything. It’s not a chosen part of my identity but that part of my identity is a lot more influential than my gender.” – Trans man, early 40s

“My gender is very important to my identity because I feel that they go hand in hand. Now my identity is also broken down into other factors [like] character, personality and other stuff that make up the recipe for my identity. But my gender plays a big part of it. … It is important because it’s how I live my life every day. When I wake up in the morning, I do things as a woman.” – Trans woman, mid-40s

“I feel more strongly connected to my other identities outside of my gender, and I feel like parts of it’s just a more universal thing, like there’s a lot more people in my socioeconomic class and we have much more shared experiences.” – Trans man, late 30s

Some participants spoke about how their gender interacted with other aspects of their identity, such as their race, culture and religion. For some, being transgender or nonbinary can be at odds with other parts of their identity or background.

“Culturally I’m Dominican and Puerto Rican, a little bit of the macho machismo culture, in my family, and even now, if I’m going to be a man, I’ve got to be a certain type of man. So, I cannot just be who I’m meant to be or who I want myself to be, the human being that I am.” – Trans man, mid-30s

“[Judaism] is a very binary religion. There is a lot of things like for men to do and a lot of things for women to do. … So, it is hard for me now as a gender queer person, right, to connect on some levels with [my] religion … I have just now been exposed to a bunch of trans Jewish spaces online which is amazing.” – Nonbinary person, mid-40s

“Just being Indian American, I identify and love aspects of my culture and ethnicity, and I find them amazing and I identify with that, but it’s kind of separated. So, I identify with the culture, then I identify here in terms of gender and being who I am, but I kind of feel the necessity to separate the two, unfortunately.” – Nonbinary person, mid-30s

“I think it’s really me being a Black woman or a Black man that can sometimes be difficult. And also, my ethnic background too. It’s really rough for me with my family back home and things of that nature.” – Nonbinary person, mid-20s

For some, deciding how open to be about their gender identity can be a constant calculation. Some participants reported that they choose whether or not to disclose that they are trans or nonbinary in a given situation based on how safe or comfortable they feel and whether it’s necessary for other people to know. This also varies depending on whether the participant can easily pass as a cisgender man or woman (that is, they can blend in so that others assume them to be cisgender and don’t recognize that they are trans or nonbinary).

“It just depends on whether I feel like I have the energy to bring it up, or if it feels worth it to me like with doctors and stuff like that. I always bring it up with my therapists, my primary [care doctor], I feel like she would get it. I guess it does vary on the situation and my capacity level.” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

“I decide based on the person and based on the context, like if I feel comfortable enough to share that piece of myself with them, because I do have the privilege of being able to move through the world and be identified as cis[gender] if I want to. But then it is important to me – if you’re important to me, then you will know who I am and how I identify. Otherwise, if I don’t feel comfortable or safe then I might not.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“The expression of my gender doesn’t vary. Who I let in to know that I was formerly female – or formerly perceived as female – is kind of on a need to know basis.” – Trans man, 60s

“It’s important to me that people not see me as cis[gender], so I have to come out a lot when I’m around new people, and sometimes that’s challenging. … It’s not information that comes out in a normal conversation. You have to force it and that’s difficult sometimes.” – Trans man, early 40s

Work is one realm where many participants said they choose not to share that they are trans or nonbinary. In some cases, this is because they want to be recognized for their work rather than the fact that they are trans or nonbinary; in others, especially for nonbinary participants, they fear it will be perceived as unprofessional.

“It’s gotten a lot better recently, but I feel like when you’re nonbinary and you use they/them pronouns, it’s just seen as really unprofessional and has been for a lot of my life.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“Whether it’s LinkedIn or profiles [that] have been updated, I’ve noticed people’s resumes have their pronouns now. I don’t go that far because I just feel like it’s a professional environment, it’s nobody’s business.” – Nonbinary person, mid-30s

“I don’t necessarily volunteer the information just to make it public; I want to be recognized for my character, my skill set, in my work in other ways.” – Trans man, early 30s

Some focus group participants said they don’t mind answering questions about what it’s like to be trans or nonbinary but were wary of being seen as the token trans or nonbinary person in their workplace or among acquaintances. Whether or not they are comfortable answering these types of questions sometimes depends on who’s asking, why they want to know, and how personal the questions get.

“I’ve talked to [my cousin about being trans] a lot because she has a daughter, and her daughter wants to transition. So, she always will come to me asking questions.” – Trans woman, early 40s

“It is tough being considered the only resource for these topics, right? In my job, I would hate to call myself the token nonbinary, but I was the first nonbinary person that they hired and they were like, ‘Oh, my gosh, let me ask you all the questions as you are obviously the authority on the subject.’ And it is like, ‘No, that is a part of me, but there are so many other great resources.’” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

“I don’t want to be the token. I’m not going to be no spokesperson. If you have questions, I’m the first person you can ask. Absolutely. I don’t mind discussing. Ask me some of the hardest questions, because if you ask somebody else you might get you know your clock cleaned. So, ask me now … so you can be educated properly. Otherwise, I don’t believe it’s anybody’s business.” – Trans woman, early 40s

Most nonbinary participants said they use “they/them” as their pronouns, but some prefer alternatives. These alternatives include a combination of gendered and gender-neutral pronouns (like she/they) or simply preferring that others use one’s names rather than pronouns.

“If I could, I would just say my name is my pronoun, which I do in some spaces, but it just is not like a larger view. It feels like I’d rather have less labor on me in that regard, so I just say they/them.” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

“For me personally, I don’t get mad if someone calls me ‘he’ because I see what they’re looking at. They look and they see a guy. So, I don’t get upset. I know a few people who do … and they correct you. Me, I’m a little more fluid. So, that’s how it works for me.” – Nonbinary person, mid-30s

“I use they/she pronouns and I put ‘they’ first because that is what I think is most comfortable and it’s what I want to draw people’s attention to, because I’m 5 feet tall and 100 pounds so it’s not like I scream masculine at first sight, so I like putting ‘they’ first because otherwise people always default to ‘she.’ But I have ‘she’ in there, and I don’t know if I’d have ‘she’ in there if I had not had kids.” – Nonbinary person, late 30s

“Why is it so hard for people to think of me as nonbinary? I choose not to use only they/them pronouns because I do sometimes identify with ‘she.’ But I’m like, ‘Do I need to use they/them pronouns to be respected as nonbinary?’ Sometimes I feel like I should do that. But I don’t want to feel like I should do anything. I just want to be myself and have that be accepted and respected.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“I have a lot of patience for people, but [once someone in public used] they/them pronouns and I thanked them and they were like, ‘Yeah, I just figure I’d do it when I don’t know [someone’s] pronouns.’ And I’m like, ‘I love it, thank you.’” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

Transgender and nonbinary participants find affirmation of their gender identity and support in various places. Many cited their friends, chosen families (and, less commonly, their relatives), therapists or other health care providers, religion, or LGBTQ+ spaces as sources of support.

“I’m just not close with my family [of origin], but I have a huge chosen family that I love and that fully respects my identity.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“Before the pandemic I used to go out to bars a lot; there’s a queer bar in my town and it was a really nice place just being friends with everybody who went and everybody who worked there, it felt really nice you know, and just hearing everybody use the right pronouns for me it just felt really good.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“I don’t necessarily go to a lot of dedicated support groups, but I found that there’s kind of a good amount of support in areas or groups or fandoms for things that have a large LGBT population within them. Like certain shows or video games, where it’s just kind of a joke that all the gay people flock to this.” – Trans woman, late teens

“Being able to practice my religion in a location with a congregation that is just completely chill about it, or so far has been completely chill about it, has been really amazing.” – Nonbinary person, late 30s

Many participants shared specific moments they said were small in the grand scheme of things but made them feel accepted and affirmed. Examples included going on dates, gestures of acceptance by a friend or social group, or simply participating in everyday activities.

“I went on a date with a really good-looking, handsome guy. And he didn’t know that I was trans. But I told him, and we kept talking and hanging out. … That’s not the first time that I felt affirmed or felt like somebody is treating me as I present myself. But … he made me feel wanted and beautiful.” – Trans woman, late 30s

“I play [on a men’s rec league] hockey [team]. … I joined the league like right when I first transitioned and I showed up and I was … nervous with locker rooms and stuff, and they just accepted me as male right away.” – Trans man, late 30s

“I ended up going into a barbershop. … The barber was very welcoming, and talked to me as if I was just a casual customer and there was something that clicked within that moment where, figuring out my gender identity, I just wanted to exist in the world to do these natural things like other boys and men would do. So, there was just something exciting about that. It wasn’t a super macho masculine moment, … he just made me feel like I blended in.” – Trans man, early 30s

Participants also talked about negative experiences, such as being misgendered, either intentionally or unintentionally. For example, some shared instances where they were treated or addressed as a gender other than the gender that they identify as, such as people referring to them as “he” when they go by “she,” or where they were deadnamed, meaning they were called by the name they had before they transitioned.

“I get misgendered on the phone a lot and that’s really annoying. And then, even after I correct them, they keep doing it, sometimes on purpose and sometimes I think they’re just reading a script or something.” – Trans man, late 30s

“The times that I have been out, presenting femme, there is this very subconscious misgendering that people do and it can be very frustrating. [Once, at a restaurant,] I was dressed in makeup and nails and shoes and everything and still everyone was like, ‘Sir, what would you like?’ … Those little things – those microaggressions – they can really eat away at people.” – Nonbinary person, mid-40s

“People not calling me by the right name. My family is a big problem, they just won’t call me by my name, you know? Except for my nephew, who is of the Millennial generation, so at least he gets it.” – Nonbinary person, 60s

“I’m constantly misgendered when I go out places. I accept this – because of the way I look, people are going to perceive me as a woman and it doesn’t cause me huge dysphoria or anything, it’s just nice that the company that I keep does use the right pronouns.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

Some participants also shared stories of discrimination, bias, humiliation, and even violence. These experiences ranged from employment discrimination to being outed (that is, someone else disclosing the fact that they are transgender or nonbinary without their permission) without their permission to physical attacks.

“I was on a date with this girl and I had to use the bathroom … and the janitor … wouldn’t let me use the men’s room, and he kept refusing to let me use the men’s room, so essentially, I ended up having to use the same bathroom as my date.” – Trans man, late 30s

“I’ve been denied employment due to my gender identity. I walked into a supermarket looking for jobs. … And they flat out didn’t let me apply. They didn’t even let me apply.” – Trans man, mid-30s

“[In high school,] this group of guys said, ‘[name] is gay.’ I ignored them but they literally threw me and tore my shirt from my back and pushed me to the ground and tried to strip me naked. And I had to fight for myself and use my bag to hit him in the face.” – Trans woman, late 20s

“I took a college course [after] I had my name changed legally and the instructor called me out in front of the class and called me a liar and outed me.” – Trans man, late 30s

Many, but not all, participants said they have received medical care , such as surgery or hormone therapy, as part of their gender transition. For those who haven’t undergone a medical transition, the reasons ranged from financial barriers to being nervous about medical procedures in general to simply not feeling that it was the right thing for them.

“For me to really to live my truth and live my identity, I had to have the surgery, which is why I went through it. It doesn’t mean [that others] have to, or that it will make you more or less of a woman because you have it. But for me to be comfortable, … that was a big part of it. And so, that’s why I felt I had to get it.” – Trans woman, early 40s

“I’m older and it’s an operation. … I’m just kind of scared, I guess. I’ve never had an operation. I mean, like any kind of operation. I’ve never been to the hospital or anything like that. So, it [is] just kind of scary. But I mean, I want to. I think about all the time. I guess have got to get the courage up to do it.” – Trans woman, early 40s

“I’ve decided that the dysphoria of a second puberty … would just be too much for me and I’m gender fluid enough where I’m happy, I guess.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“I’m too old to change anything, I mean I am what I am. [laughs]” – Nonbinary person, 60s

Many focus group participants who have sought medical treatment for their gender transition faced barriers, although some had positive experiences. For those who said there were barriers, the cost and the struggle to find sympathetic doctors were often cited as challenges.

“I was flat out turned down by the primary care physician who had to give the go-ahead to give me a referral to an endocrinologist; I was just shut down. That was it, end of story.” – Nonbinary person, 50s

“I have not had surgery, because I can’t access surgery. So unless I get breast cancer and have a double mastectomy, surgery is just not going to happen … because my health insurance wouldn’t cover something like that. … It would be an out-of-pocket plastic surgery expense and I can’t afford that at this time.” – Nonbinary person, 50s

“Why do I need the permission of a therapist to say, ‘This person’s identity is valid,’ before I can get the health care that I need to be me, that is vital for myself and for my way of life?” – Nonbinary person, mid-40s

“[My doctor] is basically the first person that actually embraced me and made me accept [who I am].” – Trans woman, late 20s

Many people who transitioned in previous decades described how access has gotten much easier in recent years. Some described relying on underground networks to learn which doctors would help them obtain medical care or where to obtain hormones illegally.

“It was hard financially because I started so long ago, just didn’t have access like that. Sometimes you have to try to go to Mexico or learn about someone in Mexico that was a pharmacist, I can remember that. That was a big thing, going through the border to Mexico, that was wild. So, it was just hard financially because they would charge so much for testosterone. And there was the whole bodybuilding community. If you were transitioning, you went to bodybuilders, and they would charge you five times what they got it [for], so it was kind of tough.” – Trans man, early 40s

“It was a lot harder to get a surgeon when I started transitioning; insurance was out of the question, there wasn’t really a national discussion around trans people and their particular medical needs. So, it was challenging having to pay everything out of pocket at a young age.” – Trans man, early 30s

“I guess it was hard for me to access hormones initially just because you had to jump through so many hoops, get letters, and then you had to find a provider that was willing to write it. And now it’s like people are getting it from their primary care doctor, which is great, but a very different experience than I had.” – Trans man, early 40s

The discussions also touched on whether the participants feel a connection with a broader lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) community or with other people who are LGBTQ+. Views varied, with some saying they feel an immediate connection with other people who are LGBTQ+, even with those who aren’t trans or nonbinary, and others saying they don’t necessarily feel this way.

“It’s kind of a recurring joke where you can meet another LGBT person and it is like there is an immediate understanding, and you are basically talking and giving each other emotional support, like you have been friends for 10-plus years.” – Trans woman, late teens

“I don’t think it’s automatic friendship between queer people, there’s like a kinship, but I don’t think there’s automatic friendship or anything. I think it’s just normal, like, how normal people make friends, just based on common interests.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“I do think of myself as part of the LGBT [community] … I use the resources that are put in place for these communities, whether that’s different health care programs, support groups, they have the community centers. … So, I do consider myself to be part of this community, and I’m able to hopefully take when needed, as well as give back.” – Trans man, mid-30s

“I feel like that’s such an important part of being a part of the [LGBTQ+] alphabet soup community, that process of constantly learning and listening to each other and … growing and developing language together … I love that aspect of creating who we are together, learning and unlearning together, and I feel like that’s a part of at least the queer community spaces that I want to be in. That’s something that’s core to me.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“I identify as queer. I feel like I’m a part of the LGBT community. That’s more of a part of my identity than being trans. … Before I came out as trans, I identified as a lesbian. That was also a big part of my identity. So, that may be too why I feel like I’m more part of the LGB community.” – Trans man, early 40s

While many trans and nonbinary participants said they felt accepted by others in the LGBTQ+ community, some participants described their gender identity as a barrier to full acceptance. There was a sense among some participants that cisgender people who are lesbian, gay or bisexual don’t always accept people who are transgender or nonbinary.

“I would really like to be included in the [LGBTQ+] community. But I have seen some people try to separate the T from LGB … I’ve run into a few situations throughout my time navigating the [LGBTQ+] community where I’ve been perceived – and I just want to say that there’s nothing wrong with this – I’ve been perceived as like a more feminine or gay man in a social setting, even though I’m heterosexual. … But the minute that that person found out that I wasn’t a gay man … and that I was actually a transgender person, they became cold and just distancing themselves. And I’ve been in a lot of those types of circumstances where there’s that divide between the rest of the community.” – Trans man, early 30s