Research Skills

Developing a research focus.

What is the difference between a subject and a topic ? What about between a research question and a research problem ? We often use these terms interchangeably, but they mean different things. As you begin to develop a personal research process, it is important to define these terms and be able to differentiate them. By the end of this section, you will be able to articulate a research question and develop a framework for a future study.

Topic vs. Subject

The best way to think about the difference between a topic and a subject is to think about the classes you took in high school. You took classes called “American History” and “World Literature,” but within those classes you studied more specific topics, like the Spanish-American War or The Aeneid . Academic research is similar. Your “subject” is your specialization within your major. If you are majoring in Communication Sciences and Disorders, for example, you may be most interested in the field of Audiology. Audiology is a research subject .

You wouldn’t be able to write a research paper on audiology, however. It’s far too broad; there are entire courses—and graduate degrees—for audiology. The first step in developing a research focus is to narrow your general subject to a more specific topic .

Here are some examples of how common subjects can be broken up into more specific topics:

As you can see from the chart above, topics are much more specific than subjects and they are more manageable to use when determining a research focus. A topic doesn’t give you enough to dive in and start drafting, but it is enough to help you develop a framework for turning the topic into a successful research project.

So how do you get from subject to topic ? The next section will give you some strategies.

Finding your Topic

Now that you understand the connections between your major and your discipline and how these create an academic discourse community, you are ready to begin sifting through the current topics, issues, and concerns that your discourse community is focused on at present. In academia, as elsewhere, there are trending topics. These topics reflect what people in your discipline think is most important at the moment. It might be helpful for you to consider what you have discussed in your major courses, or what you and those in your major discuss most often. What challenges do your field and its practitioners face now and in the future? When determining your topic, you will likely go through a number of steps. These will help you to sort through the many topics you will encounter and to select a topic that is relevant, current, and interesting to you. The best research topics are well defined, sufficiently narrow, and part of a larger problem in your discipline.

Identifying a topic

To select a viable topic for your research project, you should:

- Brainstorm about topics that you have encountered in your discourse community;

- Select several potential topics based on your interest(s);

- Ensure that the topic is manageable (i.e., that it is narrow enough);

- Ensure that scholarly material is available;

- Ensure that the topic is focused on a solvable problem;

- List academic terms associated with this topic;

- Use generated academic terms to search databases focused on your discipline; and

- Define your topic as a focused research question.

First, have a look at this resource that describes the rather intricate process of finding a research topic that is sufficiently narrow, yet still present enough in the literature of your discourse community to support a semester-long project:

Check your understanding

Let’s say your assignment is to research an environmental issue. This is a broad starting point, which is a normal first step.

One way to customize your topic is to consider how different disciplines approach the same topic in different ways. For example, here’s how the broad topic of “environmental issues” might be approached from different perspectives:

- Social Sciences: Economics of Using Wind to Produce Energy in the United States

- Sciences : Impact of Climate Change on the Habitat of Desert Animals in Arizona

- Arts and Humanities : Analysis of the Rhetoric of Environmental Protest Literature

- Determining your Topic. Authored by : Andrew Davis & Kerry Bowers. Provided by : University of Mississippi. Project : WRIT 250 Committee . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- OER Commons: Begin your Research. Provided by : OER Commons. Located at : https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/module/11888/overview . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

Privacy Policy

How to Write a Research Paper: Developing a Research Focus

- Anatomy of a Research Paper

- Developing a Research Focus

- Background Research Tips

- Searching Tips

- Scholarly Journals vs. Popular Journals

- Thesis Statement

- Annotated Bibliography

- Citing Sources

- Evaluating Sources

- Literature Review

- Academic Integrity

- Scholarship as Conversation

- Understanding Fake News

- Data, Information, Knowledge

Developing a Research Question

Developing a Strong Research Topic

Steps for Developing Your Research Focus

The ability to develop a good research topic is an important skill. An instructor may assign you a specific topic, but most often instructors require you to select your own topic of interest. When deciding on a topic, there are a few things you will need to do:

- Brainstorm for ideas.

- Choose a topic that will enable you to read and understand the articles and books you find.

- Ensure that the topic is manageable and that material is available.

- Make a list of key words.

- Be flexible. You may have to broaden or narrow your topic to fit your assignment or the sources you find.

Selecting a good topic may not be easy. It must be narrow and focused enough to be interesting, yet broad enough to find adequate information. Before selecting your final topic, make sure you know what your final project should look like. Each class or instructor will likely require a different format or style of research project.

1. Brainstorming for a Topic

Choose a topic that interests you. Use the following questions to help generate topic ideas.

- Do you have a strong opinion on a current social or political controversy?

- Did you read or see a news story recently that has piqued your interest or made you angry or anxious?

- Do you have a personal issue, problem, or interest that you would like to know more about?

- Is there an aspect of a class that you are interested in learning more about?

Write down any key words or concepts that may be of interest to you. These terms can be helpful in your searching and used to form a more focused research topic.

Be aware of overused ideas when deciding a topic. You may wish to avoid topics such as abortion, gun control, teen pregnancy, or suicide unless you feel you have a unique approach to the topic. Ask the instructor for ideas if you feel you are stuck or need additional guidance.

2. Read General Background Information

Read a general encyclopedia article on the top two or three topics you are considering.

Reading a broad summary enables you to get an overview of the topic and see how your idea relates to broader, narrower, and related issues. It also provides a great source for finding words commonly used to describe the topic. These keywords may be very useful to your research later.

If you can't find an article on your topic, try using broader terms and ask for help from a librarian.

The databases here is a good start to find general information. The library's print reference collection can also be useful and is located on the main floor of the library.

3. Focus Your Topic

Keep it manageable and be flexible. If you start doing more research and not finding enough sources that support your thesis, you may need to adjust your topic.

A topic will be very difficult to research if it is too broad or narrow. One way to narrow a broad topic such as "the environment" is to limit your topic.

Some common ways to limit a topic are by:

- geographic area

- time frame:

- population group

Remember that a topic may be too difficult to research if it is too:

- locally confined - Topics this specific may only be covered in local newspapers and not in scholarly articles.

- recent - If a topic is quite recent, books or journal articles may not be available, but newspaper or magazine articles may. Also, websites related to the topic may or may not be available.

- broadly interdisciplinary - You could be overwhelmed with superficial information.

- popular - You will only find very popular articles about some topics such as sports figures and high-profile celebrities and musicians.

Putting your topic in the form of a question will help you focus on what type of information you want to collect.

If you have any difficulties or questions with focusing your topic, discuss the topic with your instructor or with a librarian.

Tips for Choosing a Topic

Can't think of a topic to research?

Interest : Choose a topic of interest to you and your reader(s); a boring topic translates into a boring paper.

Knowledge : You can be interested in a topic without knowing much about it at the beginning, but it's a good idea to learn a little about it before you begin your research. Read about the issue in a good encyclopedia or a short article to learn more, then go at it in depth. The research process mines new knowledge – you’ll learn as you go!

Breadth of Topic : How broad is the scope of your topic? Too broad a topic is unmanageable -- for example, "The Education of Children" or "The History of Books" or "Computers in Business." A topic that is too narrow and/or trivial, such as "My Favorite Pastime," is uninteresting and extremely difficult to research.

Guidelines : Carefully follow the instructor's guidelines. If none are provided in writing, ask your professor about his or her expectations. Tell your professor what you might write about and ask for feedback and advice. This should help prevent you from selecting an inappropriate topic.

- << Previous: Anatomy of a Research Paper

- Next: Background Research Tips >>

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2024 5:51 PM

- URL: https://libguide.umary.edu/researchpaper

Airport Passenger-Related Processing Rates Guidebook (2009)

Chapter: chapter 3 - defining the research: purpose, focus, and potential uses.

Below is the uncorrected machine-read text of this chapter, intended to provide our own search engines and external engines with highly rich, chapter-representative searchable text of each book. Because it is UNCORRECTED material, please consider the following text as a useful but insufficient proxy for the authoritative book pages.

14 Chapter 3 identifies roles, relationships, and responsibilities of stakeholders. It examines principal steps involved in planning an airport passenger-rate data collection effort. It begins with the ques- tion of whether the potential benefits of the proposed effort outweigh the anticipated cost; describes different types of research (i.e., exploratory, descriptive, inferential); summarizes the questions each type addresses; and notes the ends to which the data might be used. 3.1 Roles and Responsibilities When an airport data collection event is first mentioned, it invariably raises numerous ques- tions: Who is asking for the data? How will it be used? Whatâs the budget? Whatâs the schedule? What kind of resources can be made available? Without answers to these fundamental questions, the success of your research is in jeopardy. This section will help the researcher establish the role of key stakeholders and their interrelationships within the team. Many entities can sponsor a data collection study, including airports, airlines, manufacturers, and various agencies. Likewise, there are many ways of managing and staffing the event and pro- moting involvement with stakeholders. There are therefore myriad ways of organizing a study. Exhibit 3-1 is an example of how a study could be arranged with the airport as the sponsor. 3.1.1 Client/Sponsor For airports, oversight is guided by a board, commission, or an authority consisting of appointed or elected officials. While these agencies typically provide oversight to airport man- agement and approve long-term plans and large capital expenditures, usually it is the airport director or manager who makes day-to-day decisions. Depending on the size of the airport, there may be several departments, each having its own manager. In such cases, passenger terminal-related studies would typically fall within the purview of the planning and/or engineering department and would be managed by its director. Regardless of the affiliation of the project sponsor(s), it is essential that the following ques- tions be answered clearly and unambiguously as they pertain to the sponsor at the beginning of any project: ⢠Who has primary responsibility for defining the questions the study is intended to address? ⢠What preference does this person or group have regarding ongoing involvement with the project? â What information would they like to receive, in what format, and with what frequency? â Who should be the principal point-of-contact (POC) on the clientâs side for questions that might emerge related to the studyâs focus, direction, etc.? C H A P T E R 3 Defining the Research: Purpose, Focus, and Potential Uses

Defining the Research: Purpose, Focus, and Potential Uses 15 ⢠Who is the designated project manager, and what information would he or she like to receive, in what format, and with what frequency? ⢠If the person given responsibility for day-to-day issues pertaining to access, authorizations, etc. is different from the project manager, who is that person, and what is the scope of issues he or she is authorized to address? ⢠If problems or obstacles arise in implementing the study, and the project manager is not able or authorized to resolve them, what is the chain of persons through which the issue should be escalated? 3.1.2 Study Team The size of the study team will depend on the teamâs depth and organization, and the size, duration, and complexity of the study itself. For a typical medium- to large-scale study, the roles listed in the following sections are the most typical. Multiple roles might be assumed by a single person or distributed across multiple persons. Titles vary as well, but the functions are largely universal. Project Manager The project manager is typically a mid-level to senior person who has the long-term, day-to- day relationship with his or her client counterpart. The need for the passenger-related process- ing rate study may initially originate from discussions between the project manager and those within the airport or airline. Survey Manager The survey manager is usually a mid-level staff person. His/her role on the project would be to oversee the day-to-day management of the data processing rate study, including leading the development of the scope, schedule, and budget; developing the team; and assigning roles and responsibilities. The survey manager would have the responsibility of ensuring the survey goals were adequately defined and met. Decision Maker Survey Manager Admin. Support Staffing Source (e.g., airport personnel, mkt. research firm) Surveyor Surveyor Surveyor Sponsor/Client (Airport) (Large Airport: Dir./Mgr.) Project Manager (Large Airport: Dir. Planning/Eng.) (Small Airport: Apt. Mgr.) Project Manager (Typ. oversees multiple tasks of which survey is but one part) Study Team (Typically, Consultant) Statistical Technical Expert Survey Assistant Data Analyst IT Analyst Other Stakeholders ⢠Airlines ⢠Agencies ⢠Concessionaires Exhibit 3-1. Typical sponsor and study team roles (assuming an airport is the sponsor).

16 Airport Passenger-Related Processing Rates Guidebook Research and Statistical Expert A person(s) with expertise in research methodology and quantitative/statistical analysis should be consulted to develop, or provide comments and recommendations about, the overall methodology, the sampling plan, and so forth. Most of this personâs input would occur at the projectâs initiation. A distinction is sometimes drawn in the consulting literature among differ- ent approaches to consulting. One such approach, generally referred to as process consultation might be of particular appeal.1 When acting in this role, the consultant not only provides tech- nical expertise related to the specific project, but also works with the client to develop expertise. This arrangement has the goal of, over time, reducing the reliance on the consultant. Survey Assistant The survey assistant has primary responsibility for assisting the survey project manager and secondarily to assist others on the project team throughout the duration of the study. Typically, this staff person will be at a junior level. The degree of assistance this person can provide is based on his/her level of education and current skill sets. Data Analyst The data analyst should not only be well-versed in technical analysis, but should also have a strong familiarity with the airport terminal environment. This person could be a terminal or air- port planner or aviation architect. The analyst is often largely responsible for documenting results, and responsibilities might extend to presenting findings to the client. Administrative Support Data collection efforts are inherently complex and, as such, often require a significant level of coordination and administration. The staff person serving this function would be responsible for such things as making travel plans, scheduling visits to the airportâs security office, buying supplies, shipping and receiving materials, scheduling meetings, preparing invoices and con- tracts, and editing/proofing the report. Data Collection Staff For small studies (e.g., small airports where only a few functional elements are being observed for a limited time period), airport/airline or consultant staffing may be used. For larger studies, typically examining multiple functional elements of a medium or large airport over a multi-day period, a market-research firm is frequently employed. The data collection staff reports directly to the survey manager. 3.2 Is the Study Needed? While the need for data collection is often justifiable, the benefit of validating the need, and avoiding what might be a costly, and possibly unjustified, effort well exceeds the relatively minor cost of pausing to consider a few basic questions (see Appendix C for more information). Exhibit 3-2 illustrates these questions. 3.3 Research Fundamentals This section summarizes a number of fundamental issues and terms related to the research process. (Additional detail is included in Appendix C.) 1 Schein, E. H. (1999). Process Consultation Revisited: Building the Helping Relationship. NY: Addison Wesley.

Research is a dynamic process with both deductive and inductive dimensions. This differs in some ways from what some present as the âtraditionalâ approach to research, i.e., that theory drives hypothesis testing. Sometimes it does, but sometimes it doesnât work this way. 3.3.1 Theory, Hypotheses, and Evidence The word âtheoryâ often implies a formal set of laws, propositions, variables, and the like, whose relationships are clearly defined. A related implication is that theory may not be particu- larly germane to the everyday world of work. This view of theory is not incorrect, but neither is it complete. While theory can be abstract and complex in its detail, it does not necessarily have to be abstract, complex, or formal. It can be thought of more broadly and simply as an explanation of âhow the world works.â For exam- ple, an organization might develop a mission or a value statement (or both); engrave the words in a medium intended to last millennia; and prominently display the statement in the workplace with the intent of communicating to all its perspective clients on issues pertinent to its view. In Defining the Research: Purpose, Focus, and Potential Uses 17 Question Things to Consider Have relevant data been collected at this airport in the past that might be used rather than collecting new data? Might you be able to get data from another airport similar in key ways to this airport? Are there data available that might help answer the research question? Might access to the data be blocked due to proprietary or security issues? Sometimes the data are perceived to be so sensitive that the âownerâ of the data may not give permission to share it. Has the decision already been made, and the data are being collected to legitimize the decision? Is there anything to suggest that the study is an attempt to âproveâ something true or false? What role will the results play in the decision being considered? To what extent will the decision makers be persuaded by the results? What will the decision makers accept as credible evidence? Before collecting data, make certain that the research plan will result in data that the sponsors will accept. It is better to learn beforehand, for example, that the proposed sampling plan does not meet the sponsorâs criteria for rigor. What is the cost of the potential investment that the data will help inform? What is the cost of conducting the research? Does the benefit equal or outweigh the cost? Cost should be considered not only in economic terms, but as safety, inconvenience, and so forth. Exhibit 3-2. Considerations to determine need for data collection.

2008, British Airways announced a new venture: OpenSkies. The âtheoryâ OpenSkies used to define its clients is reflected in its advertising as shown in Exhibit 3-3. So, how does this relate to airport processing rate studies? It relates in the following two ways: 1. The published research literature may well contain formal theories relevant to what data to collect and how to collect it. For example, Appendix B includes a bibliography of recent research articles related to passenger and baggage processing in airports. It is intended to illustrate the scope and diversity of research available on a given topic. Before embarking on an investigation, review the literature to see how it might enhance the quality of the planned research. The Internet provides access to numerous sources for such scholarly documents. 2. Informally, the key decisions about how to go about collecting data are grounded in assump- tions about how things work (i.e., oneâs own theory). For example, you might choose to col- lect passenger security screening data between 6:00 a.m. and 8:00 a.m. on a Monday because your experience is that this time period reflects peak checkpoint activity. While this âtheoryâ may be correct in some circumstances, it may also be wrong in others. For example, at many vacation-oriented airports, the peak at the checkpoint occurs in the late morning due to check-out times at hotels. Another common view of research is of the stereotypical scientist, objectively testing hypothe- ses (or an âeducated guessâ) arising from theory. Exhibit 3-4 reflects this general approach to research. This is certainly one way in which research proceeds, but, similar to theory, it is not the only way. Before considering an âevidence firstâ approach, we wish to mention a variation on the tra- ditional approach displayed in Exhibit 3-4 that has been gaining dominance in recent years. In particular, this is a confidence interval (CI) approach rather than a hypothesis driven approach. In a hypothesis driven approach, the researcherâs primary interest is in testing a population parameter, and uses a sample drawn from the population. When the researcher takes a CI approach, the intent is to calculate an interval within which the population parameter is likely 18 Airport Passenger-Related Processing Rates Guidebook Exhibit 3-3. OpenSkies advertisement. Question key assumptions, even if they seem to be âcommon sense,â by checking with informants, look- ing at the literature, etc.

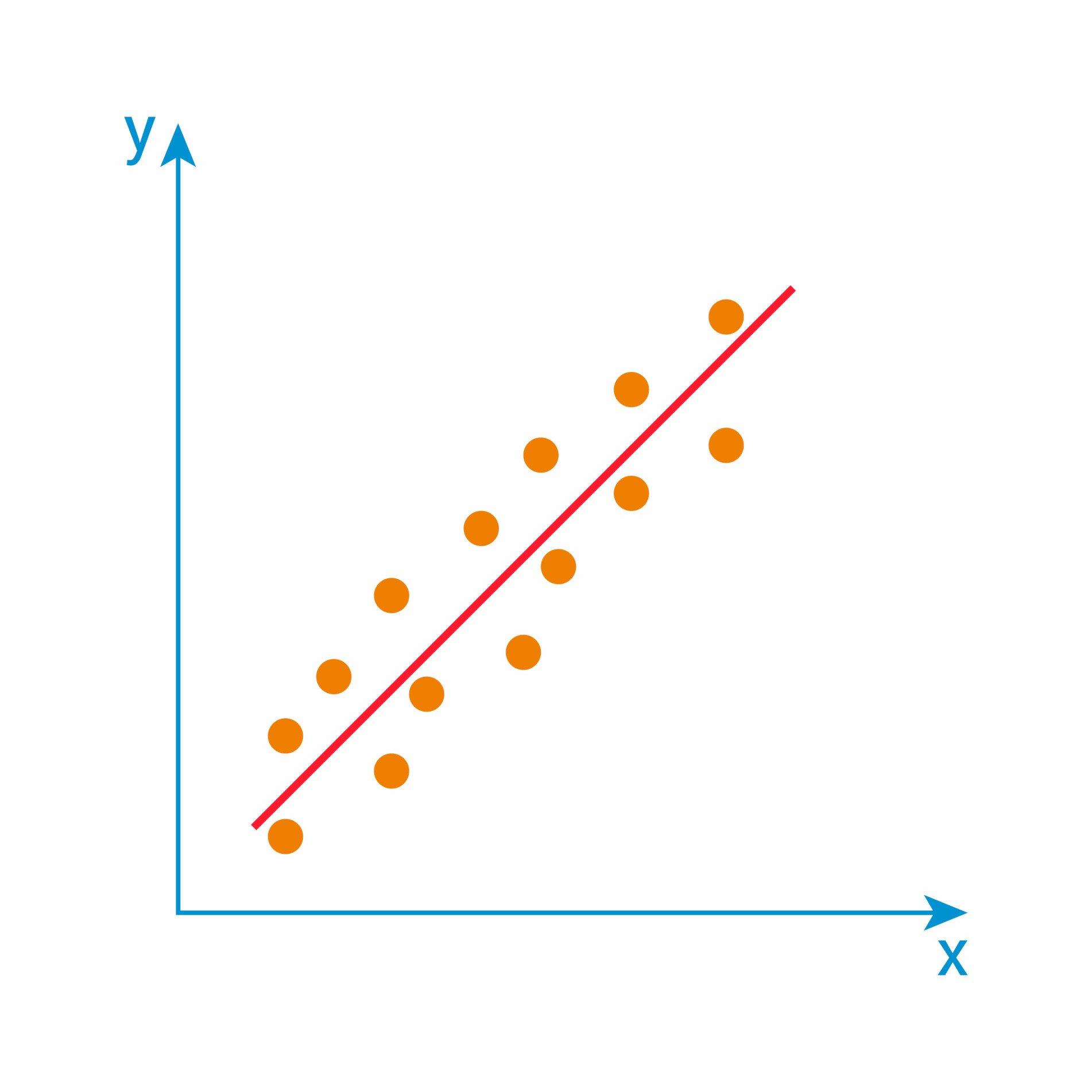

to fall. Hypotheses are stated before data collection; CIs are calculated after data are collected.2 In conducting passenger-processing rate research in airport environments, the CI approach is going to be the most appropriate in most instances. A markedly different approach to those described above is shown in Exhibit 3-5. In contrast to beginning with a theory and then collecting evidence to test the theory or estimate a popula- tion parameter within some CI, this approach begins with evidence for which one seeks poten- tial explanations, or âtheoriesâ to explain the evidence. This approach is subsumed under the broad heading of Bayesian Law, so named after the 18th Century English clergyman, Thomas Bayes, credited with developing the approach. Depending on where one begins can result in potentially dramatic conclusions (see Exhibit 3-6). This is important because limiting oneself to a particular perspective of how research should be conducted and how data ought to be gathered may impose unnecessary constraints. What is important is that the research is executed systematically and with rigor. The documented ways in which science proceeds are often idealized: portraying what is inherently a very dynamic and nonlinear process as logical and linear. 3.3.2 Research Questions and Purposes A basic issue in research is specifying the question the research will help answer. Penning a specific question also helps in determining what approach might be best used in seeking an Defining the Research: Purpose, Focus, and Potential Uses 19 Theory Drives questions & hypotheses Hypothesis: Installing n kiosks will reduce the average time of passengers waiting in line by 10% over check-in agents. Leading to a conclusion Drives data collection Followed by analysis Exhibit 3-4. Hypothesis driven approach. Evidence leads to speculation about possible explanations Which may or may not drive more data collection & analysis Theory Exhibit 3-5. Bayesian approach. 2 While these approaches are presented here as mutually exclusive, they might be integrated in practice.

answer. One classic text in research methodology5 suggests that a research question should express a relationship between two or more variables, and it should imply an empirical approach, that is, it should lend itself to being measured using data. A variable is, not surprisingly, some- thing that can vary, or assume different values. In the next section, illustrative questions are given, categorized by the purpose of research with which they are best matched. The five research purposes are presented as the following: 1. Explore, 2. Describe, 3. Test, 4. Evaluate, and 5. Predict. The distinctions among these purposes are not absolute, nor are they necessarily exclusive of one another. A research initiative might be directed at answering questions with multiple pur- poses. Indeed, this is but one of many ways of classifying research. In addition, the reader whose practice lies primarily in the arena of modeling and simulation might note their absence from this list. Although modeling and simulation applications require input data, for example, to gen- erate distributions and parameters for use as stochastic varieties in modeling, the techniques used to collect data are largely independent of specific applications (such as simulation and model- ing). Those issues unique to modeling are beyond the scope of this guidebook. Explore (Exploratory Research) Exploratory research is sometimes defined as âwhat to do when you donât know what you donât know.â Its aim is discovery and to develop an understanding of relevant variables and their interactions in a real (field) environment. Exploratory research, as such, is appropriate when the 20 Airport Passenger-Related Processing Rates Guidebook If your intent is to⦠And take action based on⦠Use⦠Example Test a hypothesis regarding a population parameter Whether you reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis Hypothesis testing approach The proportion of coach passengers checking in more than 60 min prior to scheduled departure is 80% H A : p > .80 3 H 0 : p .804 Estimate a population parameter The confidence interval selected CI approach Plus or minus 5%, what is the average time coach passengers check in prior to scheduled departure? Determine the likelihood of an event given some evidence The calculated probability Bayesian approach What is the probability that a passengerâs carry on- luggage will be subject to secondary security screening given that the passenger is boarding an international flight? Exhibit 3-6. Research approaches. 3 This is the research, or Alternative, hypothesis. It reads: The proportion is greater than 80%. 4 This is the null hypothesis. It is what is tested, and reads: The proportion is less than or equal to 80%. 5 Kerlinger F. & Lee, H. (2000). Foundations of Behavioral Research, 4th ed. NY: Harcourt Brace.

problem is not well defined. For example, passenger complaints about signs within a facility might prompt the following exploratory question: ⢠âWhere should signage be located to minimize passenger confusion?â As another example, if a new security checkpoint configuration is proposed, it may be too novel to rely on variables used in other studies. The question, therefore, might then be the following: ⢠âHow does a given alternative security checkpoint configuration affect capacity?â This type of research is often qualitative rather than quantitative. That is, it employs verbal descriptors of observations, rather than counts of those observations (see Appendix C for more information). Describe (Descriptive Research) Descriptive research, as the name implies, is intended to describe phenomena. While descrip- tive research might involve collecting qualitative data by asking open-ended questions in an interview, it typically employs quantitative methods resulting in reporting frequencies, calculat- ing averages, and the like. The following two questions illustrate the nature of descriptive research. Each implies that the relevant variables have been identified as well as the conditions under which the data should be collected. ⢠âWhat is the average number of passengers departing on international flights on weekday evenings in July at a given airport?â ⢠âHow many men use a given restroom at a particular location at a given time?â Test (Experimental and Quasi-experimental Research and Modeling) Often, the intent of the research is not simply to describe something, but to test the impact of some intervention. In an airport environment, such research might be initiated to evaluate the relative effectiveness of a security screening technology in accurately detecting contraband. It is similar in approach to research conducted to assess the relative effectiveness of an experimental drug in comparison to a control (placebo) or another drug. Variables are often manipulated and controlled. This research lies largely outside the scope of this guidebook and, as such, will not receive much attention. Examples of questions that might be asked in this type of research include the following: ⢠âWhat is the impact of posting airline personnel near check-in waiting lines on the average passenger waiting time?â In addition to the classic âexperiment,â simulation modeling might be used, employing rep- resentative data to help answer questions such as the following: ⢠âWhat would be the impact on processing time of a new security measure being considered?â ⢠âHow many agents are needed to keep passenger waiting time below an average of 10 min?â Evaluate (Evaluative Research) Sometimes, the intent of the research is to assess performance against some standard or stated requirement. Basically, evaluation research is concerned with seeing how well something is work- ing, with an eye toward improving performance, as illustrated by the following two questions: ⢠âIs the performance of a given piece of equipment in the field consistent with manufacturerâs specifications?â ⢠âOn average, what proportion of passengers waits in a security checkpoint line longer than the 10-minute maximum threshold specified by an airline?â Defining the Research: Purpose, Focus, and Potential Uses 21

Predict Finally, research might be initiated to attempt to predict or anticipate potential emerging pat- terns before they occur. This is related to environmental scanning, insofar as it represents a delib- erate attempt to monitor potential trends and their impact. For example, in the early 1970s, one might have posed the following question: ⢠âWhat would be the impact of an increase in the number of women in the workforce on air- port design?â There are numerous documented approaches to answering questions such as these. While well beyond the scope of this guidebook, here is one as illustrative: scenario planning. This method involves convening persons with relevant expertise to identify those areas that might most impact the industry (e.g., regulation, fuel costs, demographic changes), and then to systemati- cally consider what the best, worst, and might likely scenarios might be. The principal value of such an approach is that it facilitates deliberate consideration of future trends, and in so doing, presumably leaves people better prepared. When the goal of the research is to predict, data from multiple sources might be sought. The scenario planning example relies, to an extent, on the judgments of experts. Probabilities can also be drawn from historical data to help identify patterns and trends. Exhibit 3-7 is a summary of the key characteristics of each research type. 3.4 Developing the Research Plan Large research studies, particularly when funding is being requested, often require the researchers to adhere to a specific set of technical requirements. The Research Team is aware that the ad hoc and short timeline of many airport-planning research efforts makes developing a âfor- malâ research plan impracticable. Nonetheless, even though you might not have the âluxuryâ of 22 Airport Passenger-Related Processing Rates Guidebook Research Purpose Characteristics Explore Primary purpose: to better define or understand a situation. Data will help answer the research question. The benefit of conducting the research justifies the cost. Qualitative data are recorded, using observation. Describe Primary purpose: to provide descriptive information about something. Test Primary purpose: to assess the impact of a proposed change in procedure or policy. Evaluate Primary purpose: to assess performance against requirements. Predict Primary purpose: to consider possible future circumstances with the purpose of being better prepared for emerging trends. Exhibit 3-7. Summary of research types.

developing such a plan, there are benefits to considering the issues described in this section, as well as documenting basic information. The following are the three major elements the Research Team believes worth documenting, regardless of the size of the research endeavor.6 1. Goals or aims. 2. Background and significance. 3. Research design and methods. Each is described in the sections that follow. 3.4.1 Goals or Aims Specify the question the research is intended to help answer or the specific purpose of the research. The experience of having to translate an intended purpose into words can help clarify your intent. In addition, a written statement can serve as a way of ensuring that your understand- ing of the purpose of the research is consistent with that of the sponsor and other stakeholders. Two examples follow: Statement of PurposeâExample 1 The purpose of this study is to aid decision makers in determining if extending the dwell time of the airportâs automated guideway transit system (AGTS) vehicles from 30 sec to 35 sec at the Concourse C station might improve overall system capacity by providing more boarding time for passengers. Statement of PurposeâExample 2 The goal of this study is to provide airport management with recent data showing the percent- age of arriving flights whose first checked bag reaches the claim device within the airportâs goal of 15 min. 3.4.2 Background and Significance Document what is already known, and specify how the proposed research initiative will add to this knowledge. Consider a âdevilâs advocateâ perspective by asking what the consequences of not doing the research might be. 3.4.3 Research Design and Methods In this section, describe how you will go about collecting and analyzing data. Additional infor- mation about these issues, including sampling strategies and sample size, is presented in Chapter 5 and in Appendix C. The research plan does not need be lengthy. It should, however, capture key information that, were it not documented and those familiar with the research were not available, would be diffi- cult to ascertain. Defining the Research: Purpose, Focus, and Potential Uses 23 6 This section is partly based on guidelines published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.ahrq.gov/fund/esstplan.htm.

TRB’s Airport Cooperative Research Program (ACRP) Report 23: Airport Passenger-Related Processing Rates Guidebook provides guidance on how to collect accurate passenger-related processing data for evaluating facility requirements to promote efficient and cost-effective airport terminal design.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

- University Libraries Databases

- WMU Research Guides

- Philosophy Research Guide

- Develop a Research Focus

- Library Resources to Start With

Forming a Focus

Exploring information.

- Advanced Search Techniques

- Collecting Information

After seeing some directions that your topic can take, you need to find your research focus. Visualize your topic as branching arrows with the different subsections of your topic flowing out from your topic. Your research focus can be one of these arrows (aspect) or a grouping of arrows (theme).

Some topics can be broken down into many individual parts and while they are all related, one part stands out to you. It can be discussed on its own and has enough resources available for your project. This can be a specific instance of your broad topic. For example, if your topic is LGBTQIA2S+ representation in media, an aspect would be a specific character.

Other topics have individual parts that are best discussed in small groups. There's an overarching theme that ties them all together. While this is more specific than the broad topic, it still has a few separate ideas. The theme approach is best used when each individual aspect of a topic does not have enough information on its own. For example, if your topic is social media influencers, a theme would be authenticity which can be broken down into self-branding, ethics, and self-image.

Now that you have a research topic, you need to find a focus. Think back on the questions you answered for the topic you choose:

- What words are being used in titles and abstracts (article summaries) to describe the topic?

- Are there names, dates, places, things, etc. that are repeatedly mentioned?

- Is there anything more specific about a topic that sounds interesting?

The words, names, dates, places, things, etc. you found earlier are all threads that are a part of your broad topic. Search using those terms in Google , Library Search , and Google Scholar . Are you finding anything different or more specific about a certain aspect of your topic?

Exploring in Library Search

In Library Search, scroll down to find the Subjects listed on an Item Record. These are terms you can use to search for similar sources. They can also narrow your focus.

In Library Search, some resources have Related Reading on the right side of the Item Record. These are recommended items with similar topics or are a more specific aspect of your topic. Sometimes these Related Reading lists have what you were looking for even if it was not including in the search results.

Exploring in Google Scholar

Similar to Related Reading in Library Search, Google Scholar has a Related Articles link on most items to find similar sources.

- << Previous: Library Resources to Start With

- Next: Advanced Search Techniques >>

Research Focus vs Thesis/Argument

An argument or thesis statement is best developed closer to when you begin to write your paper or create your project. At that point, you have found most of the available information on your topic and can form a solid, unchanging opinion or idea around it.

A research focus helps guide your research just as a thesis statement guides your writing but a research focus changes and evolves as you encounter new information.

- Last Updated: Mar 21, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wmich.edu/philosophy

Search form

You are here, developing your central research focus.

In order to identify a relevant and useful research question it is first necessary to define an initial research focus. It is essential to select an area of research that interests you as this will help to maintain your motivation, in what is a long and rigorous process. In addition the relevance of the research focus needs to be considered in relation to how it links to current policies, research and developments in education (Menter, Elliot, Hulme, Lewoin, and Lowden, 2011). The feasibility of the project relates to the timeline for the research and researcher expertise in developing and using the chosen methods. In addition it is necessary to consider the study population, i.e. where or from whom you plan to obtain your data to enable you to select the most appropriate groups or contexts for answering your research questions and to ensure that there is sufficient accessibility for you to carry out your research (Kumar 2011).

Key things to consider:

Which aspects of education would you be interested in researching? It is very important for you to select an area of research that you are interested in as the research process is very intensive and you will be far more motivated to research an area of interest.

Are there aspects of your own practice or of the educational setting in which you work which you would like to investigate as a precursor to implementing change? This can be a rewarding field as research as findings can directly influence practice, however it is necessary to ensure that any area you choose an area that where there is existing research for you to build on.

Some features which characterise the early stages of a successful research project are listed below (Campbell 1982, cited in Robson, 2000):

The research arises out of a real world problem.

The researcher develops a good understanding of relevant theoretical perspectives by reading literature focussing on theory and research in the area of interest.

Well-developed contacts are developed with professionals within that field of study.

A framework devised by Cresswell (2011) as a template for structuring the development of a research problem has been adapted below to help you identify areas that you need to consider when developing your central research focus:

Topic: general statement of the area to be researched

Research problem: an issue within that research area which could form the basis of research

Justification for the research problem: evidence of some form which identifies the issue as being one which would benefit from further exploration e.g. deficiencies in existing research; personal observations; research findings.

Relating the discussion to audiences: explicit identification of audiences who would benefit from the research or find it of interest.

You may find it helpful to use the questions below which are based on Cresswell’s framework to help you evaluate your ideas for possible central research questions:

How could you justify researching this issue?

What evidence do you have for your justification?

Who would be interested in / benefit from this research?

Often it is necessary to have some form of stimulus to help you develop your initial ideas about what you want to research. Different starting points for research from which it is possible to develop your research focus include:

published research which focuses on effective practice

reflections on personal practical experiences and observations

educational theories

contemporary issues of significance in development of policy, exploring the possible impact of policy decisions on practice

responding to stakeholder needs e.g. those of a particular group of pupils.

Identifying issues to research

Identify some issues within education and write three questions in relation to this that could be a starting point for research. You can get ideas from this from your educational setting or from current issues, for example see resources below:

Websites for organisations which fund research projects:

Economic and Social Research Council

http://www.esrc.ac.uk

The Nuffield Foundation

http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/

The Leverhulme Trust

http://www.leverhulme.ac.uk/

The Times Educational Supplement and Times Higher Education Supplement

Evaluate the questions you have identified and choose a question to develop further and carry out some reading on related research. Rework your question based on the ideas from your readings. How has your initial question changed?

- Research Design

Creative Commons

Focusing a Research Topic

Ask these questions:

What is it?

Why should I do it?

How do I do it?

For example: Say you have to do a research project about World War II, and you don't know a thing about it, nor are you at all interested in it. Try to find a subtopic that connects to your interests. If you like cars, try comparing the land vehicles used by the Germans and the Americans. If you like fashion, look at women's fashions during the war and how they were influenced by military uniforms and the shortage of certain materials. If you like animals, look at the use of dogs by the US Armed Forces. If you like puzzles and brain teasers, look at the fascinating topic of decoding secret messages. If you like music, find out what types of music American teenagers were listening to during the war years. If you are a pacifist, find out what the anti-war movement was like during the war in any country. Find out what was happening during the war on your birth date. Find out if any of your relatives fought in the war and research that time and place.

TODAY'S HOURS:

Research Process

- Select a Topic

- Find Background Info

Focus Your Topic

- List Keywords

- Search for Sources

- Evaluate & Integrate Sources

- Cite and Track Sources

- Scientific Research & Study Design

Related Guides

- Research Topic Ideas by Liz Svoboda Last Updated May 30, 2024 150135 views this year

- Identifying Information Sources by Liz Svoboda Last Updated Mar 13, 2024 2600 views this year

- Understanding Journals: Peer-Reviewed, Scholarly, & Popular by Liz Svoboda Last Updated Jan 10, 2024 1606 views this year

Have a Question? Need Some Help?

Email: [email protected] Phone: (810) 762-3400 Text message: (810) 407-5434 (text messages only)

Keep it manageable and be flexible. If you start doing more research and not finding enough sources that support your thesis, you may need to adjust your topic.

A topic will be very difficult to research if it is too broad or narrow. One way to narrow a broad topic such as "the environment" is to limit your topic. Some common ways to limit a topic are:

- by geographic area

Example: What environmental issues are most important in the Southwestern United States?

Example: How does the environment fit into the Navajo world view?

- by time frame

Example: What are the most prominent environmental issues of the last 10 years?

- by discipline

Example: How does environmental awareness effect business practices today?

- by population group

Example: What are the effects of air pollution on senior citizens?

Remember that a topic may be too difficult to research if it is too:

- locally confined - Topics this specific may only be covered in local newspapers and not in scholarly articles.

Example: What sources of pollution affect the air in Genesee County?

- recent - If a topic is quite recent, books or journal articles may not be available, but newspaper or magazine articles may. Also, websites related to the topic may or may not be available.

- broadly interdisciplinary - You could be overwhelmed with superficial information.

Example: How can the environment contribute to the culture, politics and society of the Western United States?

- popular - You will only find very popular articles about some topics such as sports figures and high-profile celebrities and musicians.

Putting your topic in the form of a question will help you focus on what type of information you want to collect.

If you have any difficulties or questions with focusing your topic, discuss the topic with your instructor, or with a librarian.

- Topic Concept Map Download and print this PDF to create a concept map for your topic. Put your main topic in the middle circle and then put ideas related to your topic on the lines radiating from the circle.

- << Previous: Find Background Info

- Next: List Keywords >>

- Last Updated: May 29, 2024 1:31 PM

- URL: https://libguides.umflint.edu/research

What Is a Focus Group?

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

A focus group is a qualitative research method that involves facilitating a small group discussion with participants who share common characteristics or experiences that are relevant to the research topic. The goal is to gain insights through group conversation and observation of dynamics.

In a focus group:

- A moderator asks questions and leads a group of typically 6 to 12 pre-screened participants through a discussion focused on a particular topic.

- Group members are encouraged to talk with one another, exchange anecdotes, comment on each others’ experiences and points of view, and build on each others’ responses.

- The goal is to create a candid, natural conversation that provides insights into the participants’ perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, and opinions on the topic.

- Focus groups capitalize on group dynamics to elicit multiple perspectives in a social environment as participants are influenced by and influence others through open discussion.

- The interactive responses allow researchers to quickly gather more contextual, nuanced qualitative data compared to surveys or one-on-one interviews.

Focus groups allow researchers to gather perspectives from multiple people at once in an interactive group setting. This group dynamic surfaces richer responses as participants build on each other’s comments, discuss issues in-depth, and voice agreements or disagreements.

It is important that participants feel comfortable expressing diverse viewpoints rather than being pressured into a consensus.

Focus groups emerged as an alternative to questionnaires in the 1930s over concerns that surveys fostered passive responses or failed to capture people’s authentic perspectives.

During World War II, focus groups were used to evaluate military morale-boosting radio programs. By the 1950s focus groups became widely adopted in marketing research to test consumer preferences.

A key benefit K. Merton highlighted in 1956 was grouping participants with shared knowledge of a topic. This common grounding enables people to provide context to their experiences and allows contrasts between viewpoints to emerge across the group.

As a result, focus groups can elicit a wider range of perspectives than one-on-one interviews.

Step 1 : Clarify the Focus Group’s Purpose and Orientation

Clarify the purpose and orientation of the focus group (Tracy, 2013). Carefully consider whether a focus group or individual interviews will provide the type of qualitative data needed to address your research questions.

Determine if the interactive, fast-paced group discussion format is aligned with gathering perspectives vs. in-depth attitudes on a topic.

Consider incorporating special techniques like extended focus groups with pre-surveys, touchstones using creative imagery/metaphors to focus the topic, or bracketing through ongoing conceptual inspection.

For example

A touchstone in a focus group refers to using a shared experience, activity, metaphor, or other creative technique to provide a common reference point and orientation for grounding the discussion.

The purpose of Mulvale et al. (2021) was to understand the hospital experiences of youth after suicide attempts.

The researchers created a touchstone to focus the discussion specifically around the hospital visit. This provided a shared orientation for the vulnerable participants to open up about their emotional journeys.

In the example from Mulvale et al. (2021), the researchers designated the hospital visit following suicide attempts as the touchstone. This means:

- The visit served as a defining shared experience all youth participants could draw upon to guide the focus group discussion, since they unfortunately had this in common.

- Framing questions around recounting and making meaning out of the hospitalization focused the conversation to elicit rich details about interactions, emotions, challenges, supports needed, and more in relation to this watershed event.

- The hospital visit as a touchstone likely resonated profoundly across youth given the intensity and vulnerability surrounding their suicide attempts. This deepened their willingness to open up and established group rapport.

So in this case, the touchstone concentrated the dialogue around a common catalyst experience enabling youth to build understanding, voice difficulties, and potentially find healing through sharing their journey with empathetic peers who had endured the same trauma.

Step 2 : Select a Homogeneous Grouping Characteristic

Select a homogeneous grouping characteristic (Krueger & Casey, 2009) to recruit participants with a commonality, like shared roles, experiences, or demographics, to enable meaningful discussion.

A sample size of between 6 to 10 participants allows for adequate mingling (MacIntosh 1993).

More members may diminish the ability to capture all viewpoints. Fewer risks limited diversity of thought.

Balance recruitment across income, gender, age, and cultural factors to increase heterogeneity in perspectives. Consider screening criteria to qualify relevant participants.

Choosing focus group participants requires balancing homogeneity and diversity – too much variation across gender, class, profession, etc., can inhibit sharing, while over-similarity limits perspectives. Groups should feel mutual comfort and relevance of experience to enable open contributions while still representing a mix of viewpoints on the topic (Morgan 1988).

Mulvale et al. (2021) determined grouping by gender rather than age or ethnicity was more impactful for suicide attempt experiences.

They fostered difficult discussions by bringing together male and female youth separately based on the sensitive nature of topics like societal expectations around distress.

Step 3 : Designate a Moderator

Designate a skilled, neutral moderator (Crowe, 2003; Morgan, 1997) to steer productive dialogue given their expertise in guiding group interactions. Consider cultural insider moderators positioned to foster participant sharing by understanding community norms.

Define moderator responsibilities like directing discussion flow, monitoring air time across members, and capturing observational notes on behaviors/dynamics.

Choose whether the moderator also analyzes data or only facilitates the group.

Mulvale et al. (2021) designated a moderator experienced working with marginalized youth to encourage sharing by establishing an empathetic, non-judgmental environment through trust-building and active listening guidance.

Step 4 : Develop a Focus Group Guide

Develop an extensive focus group guide (Krueger & Casey, 2009). Include an introduction to set a relaxed tone, explain the study rationale, review confidentiality protection procedures, and facilitate a participant introduction activity.

Also include guidelines reiterating respect, listening, and sharing principles both verbally and in writing.

Group confidentiality agreement

The group context introduces distinct ethical demands around informed consent, participant expectations, confidentiality, and data treatment. Establishing guidelines at the outset helps address relevant issues.

Create a group confidentiality agreement (Berg, 2004) specifying that all comments made during the session must remain private, anonymous in data analysis, and not discussed outside the group without permission.

Have it signed, demonstrating a communal commitment to sustaining a safe, secure environment for honest sharing.

Berg (2004) recommends a formal signed agreement prohibiting participants from publicly talking about anything said in the focus group without permission. This reassures members their personal disclosures are safeguarded.

Develop questions starting general then funneling down to 10-12 key questions on critical topics. Integrate think/pair/share activities between question sets to encourage inclusion. Close with a conclusion to summarize key ideas voiced without endorsing consensus.

Krueger and Casey (2009) recommend structuring focus group questions in five stages:

Opening Questions:

- Start with easy, non-threatening questions to make participants comfortable, often related to their background and experience with the topic.

- Get everyone talking and open up initial dialogue.

- Example: “Let’s go around and have each person share how long you’ve lived in this city.”

Introductory Questions:

- Transition to the key focus group objectives and main topics of interest.

- Remain quite general to provide baseline understanding before drilling down.

- Example: “Thinking broadly, how would you describe the arts and cultural offerings in your community?”

Transition Questions:

- Serve as a logical link between introductory and key questions.

- Funnel participants toward critical topics guided by research aims.

- Example: “Specifically related to concerts and theatre performances, what venues in town have you attended events at over the past year?”

Key Questions:

- Drive at the heart of study goals, and issues under investigation.

- Ask 5-10 questions that foster organic, interactive discussion between participants.

- Example: “What enhances or detracts from the concert-going experience at these various venues?”

Ending Questions:

- Provide an opportunity for final thoughts or anything missed.

- Assess the degree of consensus on key topics.

- Example: “If you could improve just one thing about the concert and theatre options here, what would you prioritize?”

It is vital to extensively pilot test draft questions to hone the wording, flow, timing, tone and tackle any gaps to adequately cover research objectives through dynamic group discussion.

Step 5 : Prepare the focus group room

Prepare the focus group room (Krueger & Casey, 2009) attending to details like circular seating for eye contact, centralized recording equipment with backup power, name cards, and refreshments to create a welcoming, affirming environment critical for participants to feel valued, comfortable engaging in genuine dialogue as a collective.

Arrange seating comfortably in a circle to facilitate discussion flow and eye contact among members. Decide if space for breakout conversations or activities like role-playing is needed.

Refreshments

- Coordinate snacks or light refreshments to be available when focus group members arrive, especially for longer sessions. This contributes to a welcoming atmosphere.

- Even if no snacks are provided, consider making bottled water available throughout the session.

- Set out colorful pens and blank name tags for focus group members to write their preferred name or pseudonym when they arrive.

- Attaching name tags to clothing facilitates interaction and expedites learning names.

- If short on preparation time, prepare printed name tags in advance based on RSVPs, but blank name tags enable anonymity if preferred.

Krueger & Casey (2009) suggest welcoming focus group members with comfortable, inclusive seating arrangements in a circle to enable eye contact. Providing snacks and music sets a relaxed tone.

Step 6 : Conduct the focus group

Conduct the focus group utilizing moderation skills like conveying empathy, observing verbal and non-verbal cues, gently redirecting and probing overlooked members, and affirming the usefulness of knowledge sharing.

Use facilitation principles (Krueger & Casey, 2009; Tracy 2013) like ensuring psychological safety, mutual respect, equitable airtime, and eliciting an array of perspectives to expand group knowledge. Gain member buy-in through collaborative review.

Record discussions through detailed note-taking, audio/video recording, and seating charts tracking engaged participation.

The role of moderator

The moderator is critical in facilitating open, interactive discussion in the group. Their main responsibilities are:

- Providing clear explanations of the purpose and helping participants feel comfortable

- Promoting debate by asking open-ended questions

- Drawing out differences of opinion and a range of perspectives by challenging participants

- Probing for more details when needed or moving the conversation forward

- Keeping the discussion focused and on track

- Ensuring all participants get a chance to speak

- Remaining neutral and non-judgmental, without sharing personal opinions

Moderators need strong interpersonal abilities to build participant trust and comfort sharing. The degree of control and input from the moderator depends on the research goals and personal style.

With multiple moderators, roles, and responsibilities should be clear and consistent across groups. Careful preparation is key for effective moderation.

Mulvale et al. (2021) fostered psychological safety for youth to share intense emotions about suicide attempts without judgment. The moderator ensured equitable speaking opportunities within a compassionate climate.

Krueger & Casey (2009) advise moderators to handle displays of distress empathetically by offering a break and emotional support through active listening instead of ignoring reactions. This upholds ethical principles.

Advantages and disadvantages of focus groups

Focus groups efficiently provide interactive qualitative data that can yield useful insights into emerging themes. However, findings may be skewed by group behaviors and still require larger sample validation through added research methods. Careful planning is vital.

- Efficient way to gather a range of perspectives in participants’ own words in a short time

- Group dynamic encourages more complex responses as members build on others’ comments

- Can observe meaningful group interactions, consensus, or disagreements

- Flexibility for moderators to probe unanticipated insights during discussion

- Often feels more comfortable sharing as part of a group rather than one-on-one

- Helps participants recall and reflect by listening to others tell their stories

Disadvantages

- Small sample size makes findings difficult to generalize

- Groupthink: influential members may discourage dissenting views from being shared

- Social desirability bias: reluctance from participants to oppose perceived majority opinions

- Requires highly skilled moderators to foster inclusive participation and contain domineering members

- Confidentiality harder to ensure than with individual interviews

- Transcriptions may have overlapping talk that is difficult to capture accurately

- Group dynamics adds layers of complexity for analysis beyond just the content of responses

Goss, J. D., & Leinbach, T. R. (1996). Focus groups as alternative research practice: experience with transmigrants in Indonesia. Area , 115-123.

Kitzinger, J. (1994). The methodology of focus groups: the importance of interaction between research participants . Sociology of health & illness , 16 (1), 103-121.

Kitzinger J. (1995). Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311 , 299-302.

Morgan D.L. (1988). Focus groups as qualitative research . London: Sage.

Mulvale, G., Green, J., Miatello, A., Cassidy, A. E., & Martens, T. (2021). Finding harmony within dissonance: engaging patients, family/caregivers and service providers in research to fundamentally restructure relationships through integrative dynamics . Health Expectations , 24 , 147-160.

Powell, R. A., Single, H. M., & Lloyd, K. R. (1996). Focus groups in mental health research: enhancing the validity of user and provider questionnaires . International Journal of Social Psychiatry , 42 (3), 193-206.

Puchta, C., & Potter, J. (2004). Focus group practice . Sage.

Redmond, R. A., & Curtis, E. A. (2009). Focus groups: principles and process. Nurse researcher , 16 (3).

Smith, J. A., Scammon, D. L., & Beck, S. L. (1995). Using patient focus groups for new patient services. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement , 21 (1), 22-31.

Smithson, J. (2008). Focus groups. The Sage handbook of social research methods , 357-370.

White, G. E., & Thomson, A. N. (1995). Anonymized focus groups as a research tool for health professionals. Qualitative Health Research , 5 (2), 256-261.

Download PDF slides of the presentation ‘ Conducting Focus Groups – A Brief Overview ‘

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

Convergent Validity: Definition and Examples

Chapter 12. Focus Groups

Introduction.

Focus groups are a particular and special form of interviewing in which the interview asks focused questions of a group of persons, optimally between five and eight. This group can be close friends, family members, or complete strangers. They can have a lot in common or nothing in common. Unlike one-on-one interviews, which can probe deeply, focus group questions are narrowly tailored (“focused”) to a particular topic and issue and, with notable exceptions, operate at the shallow end of inquiry. For example, market researchers use focus groups to find out why groups of people choose one brand of product over another. Because focus groups are often used for commercial purposes, they sometimes have a bit of a stigma among researchers. This is unfortunate, as the focus group is a helpful addition to the qualitative researcher’s toolkit. Focus groups explicitly use group interaction to assist in the data collection. They are particularly useful as supplements to one-on-one interviews or in data triangulation. They are sometimes used to initiate areas of inquiry for later data collection methods. This chapter describes the main forms of focus groups, lays out some key differences among those forms, and provides guidance on how to manage focus group interviews.

Focus Groups: What Are They and When to Use Them

As interviews, focus groups can be helpfully distinguished from one-on-one interviews. The purpose of conducting a focus group is not to expand the number of people one interviews: the focus group is a different entity entirely. The focus is on the group and its interactions and evaluations rather than on the individuals in that group. If you want to know how individuals understand their lives and their individual experiences, it is best to ask them individually. If you want to find out how a group forms a collective opinion about something (whether a product or an event or an experience), then conducting a focus group is preferable. The power of focus groups resides in their being both focused and oriented to the group . They are best used when you are interested in the shared meanings of a group or how people discuss a topic publicly or when you want to observe the social formation of evaluations. The interaction of the group members is an asset in this method of data collection. If your questions would not benefit from group interaction, this is a good indicator that you should probably use individual interviews (chapter 11). Avoid using focus groups when you are interested in personal information or strive to uncover deeply buried beliefs or personal narratives. In general, you want to avoid using focus groups when the subject matter is polarizing, as people are less likely to be honest in a group setting. There are a few exceptions, such as when you are conducting focus groups with people who are not strangers and/or you are attempting to probe deeply into group beliefs and evaluations. But caution is warranted in these cases. [1]

As with interviewing in general, there are many forms of focus groups. Focus groups are widely used by nonresearchers, so it is important to distinguish these uses from the research focus group. Businesses routinely employ marketing focus groups to test out products or campaigns. Jury consultants employ “mock” jury focus groups, testing out legal case strategies in advance of actual trials. Organizations of various kinds use focus group interviews for program evaluation (e.g., to gauge the effectiveness of a diversity training workshop). The research focus group has many similarities with all these uses but is specifically tailored to a research (rather than applied) interest. The line between application and research use can be blurry, however. To take the case of evaluating the effectiveness of a diversity training workshop, the same interviewer may be conducting focus group interviews both to provide specific actionable feedback for the workshop leaders (this is the application aspect) and to learn more about how people respond to diversity training (an interesting research question with theoretically generalizable results).

When forming a focus group, there are two different strategies for inclusion. Diversity focus groups include people with diverse perspectives and experiences. This helps the researcher identify commonalities across this diversity and/or note interactions across differences. What kind of diversity to capture depends on the research question, but care should be taken to ensure that those participating are not set up for attack from other participants. This is why many warn against diversity focus groups, especially around politically sensitive topics. The other strategy is to build a convergence focus group , which includes people with similar perspectives and experiences. These are particularly helpful for identifying shared patterns and group consensus. The important thing is to closely consider who will be invited to participate and what the composition of the group will be in advance. Some review of sampling techniques (see chapter 5) may be helpful here.

Moderating a focus group can be a challenge (more on this below). For this reason, confining your group to no more than eight participants is recommended. You probably want at least four persons to capture group interaction. Fewer than four participants can also make it more difficult for participants to remain (relatively) anonymous—there is less of a group in which to hide. There are exceptions to these recommendations. You might want to conduct a focus group with a naturally occurring group, as in the case of a family of three, a social club of ten, or a program of fifteen. When the persons know one another, the problems of too few for anonymity don’t apply, and although ten to fifteen can be unwieldy to manage, there are strategies to make this possible. If you really are interested in this group’s dynamic (not just a set of random strangers’ dynamic), then you will want to include all its members or as many as are willing and able to participate.

There are many benefits to conducting focus groups, the first of which is their interactivity. Participants can make comparisons, can elaborate on what has been voiced by another, and can even check one another, leading to real-time reevaluations. This last benefit is one reason they are sometimes employed specifically for consciousness raising or building group cohesion. This form of data collection has an activist application when done carefully and appropriately. It can be fun, especially for the participants. Additionally, what does not come up in a focus group, especially when expected by the researcher, can be very illuminating.

Many of these benefits do incur costs, however. The multiplicity of voices in a good focus group interview can be overwhelming both to moderate and later to transcribe. Because of the focused nature, deep probing is not possible (or desirable). You might only get superficial thinking or what people are willing to put out there publicly. If that is what you are interested in, good. If you want deeper insight, you probably will not get that here. Relatedly, extreme views are often suppressed, and marginal viewpoints are unspoken or, if spoken, derided. You will get the majority group consensus and very little of minority viewpoints. Because people will be engaged with one another, there is the possibility of cut-off sentences, making it even more likely to hear broad brush themes and not detailed specifics. There really is very little opportunity for specific follow-up questions to individuals. Reading over a transcript, you may be frustrated by avenues of inquiry that were foreclosed early.

Some people expect that conducting focus groups is an efficient form of data collection. After all, you get to hear from eight people instead of just one in the same amount of time! But this is a serious misunderstanding. What you hear in a focus group is one single group interview or discussion. It is not the same thing at all as conducting eight single one-hour interviews. Each focus group counts as “one.” Most likely, you will need to conduct several focus groups, and you can design these as comparisons to one another. For example, the American Sociological Association (ASA) Task Force on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology began its study of the impact of class in sociology by conducting five separate focus groups with different groups of sociologists: graduate students, faculty (in general), community college faculty, faculty of color, and a racially diverse group of students and faculty. Even though the total number of participants was close to forty, the “number” of cases was five. It is highly recommended that when employing focus groups, you plan on composing more than one and at least three. This allows you to take note of and potentially discount findings from a group with idiosyncratic dynamics, such as where a particularly dominant personality silences all other voices. In other words, putting all your eggs into a single focus group basket is not a good idea.

How to Conduct a Focus Group Interview/Discussion

Advance preparations.

Once you have selected your focus groups and set a date and time, there are a few things you will want to plan out before meeting.