- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Scholarly Voice: Varying Sentence Structure

Sentence structure refers to the physical nature of a sentence and how the elements of that sentence are presented. Just like word choice, writers should strive to vary their sentence structure to create rhythmic prose and keep their reader interested. Sentences that require a variation often repeat subjects, lengths, or types.

Related information about varying sentence structures can be found through these links:

- Sentence Structure and Types of Sentences

- Run-On Sentences and Sentence Fragments

- Parallel Construction

- Relative, Restrictive, and Nonrestrictive Clauses

- Conjunctions

Varying Subject or Word Choice

One of the easiest ways to spot text that requires variety is by noting how each sentence opens. Writers can often overuse the same word, like an author’s name, or a subject, like pronouns to refer to an author, when beginning sentences. This lack of subject variety can be distracting to a reader. Review the following paragraph’s sentence variety:

My philosophy of education is derived from my personal experiences. I have been an educator for 4 years, and I have learned a lot from more experienced teachers in my district. I also work mainly with students from a low socioeconomic background; my background was quite different. I will discuss how all of these elements, along with scholarly texts, have impacted my educational philosophy.

Notice how the writer of this paragraph starts each sentence and clause with a personal pronoun. Although the writer does alternate between “I” and “my”, both pronouns refer to the same subject. This repetition of personal pronouns is most common when writing a Personal Development Plan (PDP) or other personal papers. To avoid this type of repetition, try adjusting the placement of prepositional phrases or dependent clauses so the subject does not open each sentence:

My philosophy of education is derived from my personal experiences. Having been an educator for 4 years, I have learned a lot from more experienced teachers in my district. I also work mainly with students from a low socioeconomic background that is quite different from mine. In this paper, I will discuss how all of these elements, along with scholarly texts, have impacted my educational philosophy.

Varying Sentence Length

Another way to spot needed sentence variety is through the length of each sentence. Repeating longer sentences can inundate a reader and overshadow arguments, while frequently relying on shorter sentences can make an argument feel rushed or stunted.

Overusing Long Sentences

The company reported that yearly profit growth, which had steadily increased by more than 7% since 1989, had stabilized in 2009 with a 0% comp, and in 2010, the year they launched the OWN project, actually decreased from the previous year by 2%. This announcement stunned Wall Street analysts, but with the overall decrease in similar company profit growth worldwide, as reported by Author (Year) in his article detailing the company’s history, the company’s announcement aligns with industry trends and future industry predictions.

Notice how this paragraph is comprised of just two sentences. While each clause does provide relevant information, the reader may have difficulty identifying the subject and purpose of the whole paragraph.

Overusing Short Sentences

In 2010, the company’s yearly profit growth decreased from the previous year by 2%. This was the year they launched the OWN project. The profit growth had steadily increased by more than 7% since 1989. (They stabilized in 2009.) This announcement stunned Wall Street analysts. However, it aligns with the decrease in similar company profit growth worldwide. It also supports future predictions for the industry (Author, Year).

Notice how this paragraph uses the same information as the previous one but breaks it into seven sentences. While the information is more digestible through these shorter sentences, the reader may not know what information is the most pertinent to the paragraph’s purpose.

Alternating Sentence Length

Alternating between lengths allows writers to use sentences strategically, emphasizing important points through short sentences and telling stories with longer ones:

The company reported that profit growth stabilized in 2009, though it had steadily increased by more than 7% since 1989. In 2010, the year they launched the OWN project, company profit growth decreased from the previous year. This announcement stunned Wall Street analysts. According to Author (Year), however, this decrease was an example of a trend across similar company profit growth worldwide; it also supports future predictions for the industry.

Varying Sentence Type

One of the trickiest patterns to spot is that of repetitive sentence type. Just like subject and length, overusing a sentence type can hinder a reader’s engagement with a text. There are four types of sentences: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. Each sentence is defined by the use of independent and dependent clauses, conjunctions, and subordinators.

- Simple sentences: A simple sentence is an independent clause with no conjunction or dependent clause.

- Compound sentences: A compound sentence is two independent clauses joined by a conjunction (e.g., and, but, or, for, nor, yet, so).

- Complex sentences: A complex sentence contains one independent clause and at least one dependent clause. The clauses in a complex sentence are combined with conjunctions and subordinators, terms that help the dependent clauses relate to the independent clause. Subordinators can refer to the subject (who, which), the sequence/time (since, while), or the causal elements (because, if) of the independent clause.

- Compound-complex sentences: A compound-complex sentence contains multiple independent clauses and at least one dependent clause. These sentences will contain both conjunctions and subordinators.

Understanding sentence type will help writers note areas that should be varied through the use of clauses, conjunctions, and subordinators.

In her article, Author (Year) noted that the participants did not see a change in symptoms after the treatment. Even during the treatment, Author observed no change in the statements from the participants regarding their symptoms. Based on these findings, I will not use this article for my final project. Because my project will rely on articles that note symptom improvement, Author’s work is not applicable.

Notice how the writer relies solely on complex sentences in this paragraph, even placing dependent clauses at the beginning of each sentence. Here is an example of merely adjusting the placement of these dependent clauses but not the sentence type:

In her article, Author (Year) noted that the participants did not see a change in symptoms after the treatment. Author observed, even during treatment, no change in the statements from the participants regarding their symptoms. I will not use this article for my final project based on these findings. Because my project will rely on articles that note symptom improvement, Author’s work is not applicable.

While this change in the placement of dependent clauses does avoid a repetitive rhythm to the paragraph, try combining sentences or using conjunctions to create compound or compound-complex sentences to vary sentence type:

In her article, Author (Year) noted that the participants did not see a change in symptoms after the treatment. Author observed, even during treatment, no change in the statements from the participants regarding their symptoms, and based on these findings, I will not use this article for my final project. Because my project will rely on articles that note symptom improvement, Author’s work is not applicable.

Making these slight adjustments to sentence type helps the reader engage with the narrative rather than focus on the structure of the text. Adjusting your sentence type during a final revision is a great way to create effective prose for any scholarly document.

Varying Sentence Structure Video Playlist

Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

- Engaging Writing: Overview of Tools for Engaging Readers (video transcript)

- Engaging Writing: Tool 1—Syntax (video transcript)

- Engaging Writing: Tool 2—Sentence Structure (video transcript)

- Engaging Writing: Tool 3—Punctuation (video transcript)

- Structuring Sentences: Simple Sentences (video transcript)

- Structuring Sentences: Compound Sentences (video transcript)

- Structuring Sentences: Complex Sentences (video transcript)

- Structuring Sentences: Combining Sentences (video transcript)

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Writing Concisely

- Next Page: Point of View

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Sentence Structure: A Complete Guide (With Examples & Tasks)

This article is part of the ultimate guide to language for teachers and students. Click the buttons below to view these.

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO SENTENCE STRUCTURE

This article aims to inform teachers and students about writing great sentences for all text types and genres. I would also recommend reading our complete guide to writing a great paragraph here. Both articles will find great advice, teaching ideas, and resources.

WHAT IS SENTENCE STRUCTURE?

When we talk about ‘sentence structure’, we are discussing the various elements of a sentence and how these elements are organized on the page to convey the desired effect of the author.

Writing well in terms of sentence structure requires our students to become familiar with various elements of grammar and the various types of sentences that exist in English.

In this article, we will explore these areas and discuss various ideas and activities you can use in the classroom to help your students on the road to mastering these different sentence structures. This will help make their writing more precise and interesting in the process.

TYPES OF SENTENCE STRUCTURE

In English, students need to get their heads around four types of sentences. They are:

Mastering these four types of sentences will enable students to articulate themselves effectively and with personality and style.

Achieving this necessarily takes plenty of practice, but the process begins with ensuring that each student has a firm grasp on how each type of sentence structure works.

But, before we examine these different types of structures, we must ensure our students understand the difference between independent and dependent clauses. Understanding clauses and how they work will make it much easier for students to grasp the following types of sentences.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING SENTENCE STRUCTURE

This complete SENTENCE STRUCTURE UNIT is designed to take students from zero to hero over FIVE STRATEGIC LESSONS to improve SENTENCE WRITING SKILLS through PROVEN TEACHING STRATEGIES covering:

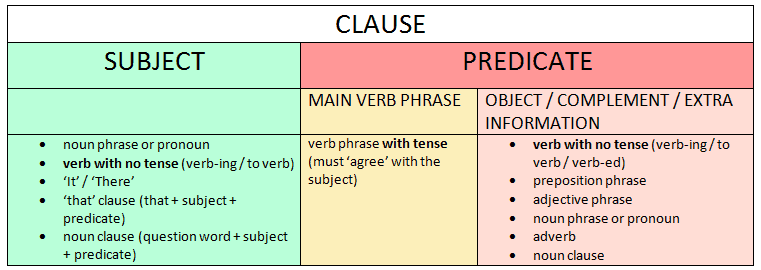

SENTENCE CLAUSES

Teaching sentence clauses requires a deep understanding of the topic and an ability to explain it in an engaging and easy way for students to understand. In this article, we’ll discuss the basics of sentence clauses and provide some tips for teaching them to students.

What are Sentence Clauses?

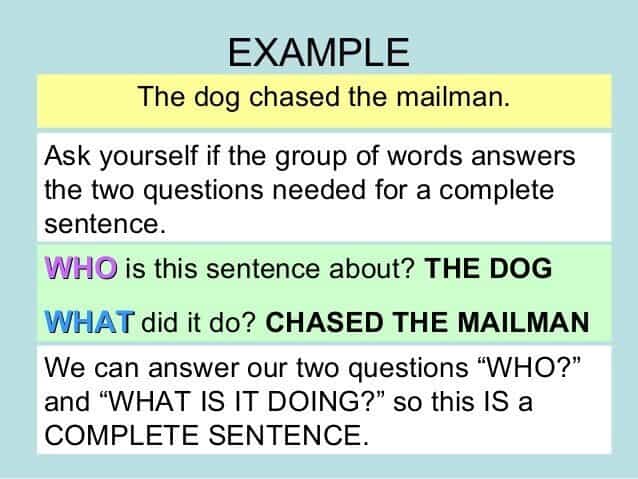

A sentence clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb. It can be a complete sentence on its own or a part of a larger sentence. There are two types of sentence clauses: independent and dependent.

Independent Clauses

Put simply; clauses are parts of a sentence containing a verb. An independent clause can stand by itself as a complete sentence. It expresses a complete thought or idea and includes a subject and a verb – more on this shortly!

Here’s an example of an independent clause in a sentence:

“I went to the store.”

In this sentence, “I went to the store” is an independent clause because it can stand alone as a complete sentence and expresses a complete thought. It has a subject (“I”) and a verb (“went”), and it can be punctuated with a period.

Dependent Clauses / Subordinate Clauses

Dependent clauses, on the other hand, are not complete sentences and cannot stand by themselves. They do not express a complete idea. To become complete, they must be attached to an independent clause. Dependent clauses are also known as subordinate clauses .

An excellent way to illustrate the difference between the two is by providing an example that contains both.

For example:

Even though I am tired, I am going to work tonight.

The non-underlined portion of the sentence doesn’t work as a sentence on its own, so it is a dependent clause. The underlined portion of the sentence could operate as a sentence in its own right, and it is, therefore, an independent clause.

Now we’ve got clauses out of the way, we’re ready to look at each type of sentence in turn.

Teaching sentence clauses to students is essential because it helps them understand sentence structure. Understanding the structure of sentences is essential for effective writing and communication. It also helps students to identify and correct common errors in their writing, such as sentence fragments and run-on sentences.

Simple Sentences

Simple sentences are, unsurprisingly, the easiest type of sentence for students to grasp and construct for themselves. Often these types of sentences will be the first sentences that children write by themselves, following the well-known Subject – Verb – Object or SVO pattern.

The subject of the sentence will be the noun that begins the sentence. This may be a person, place, or thing, but most importantly, it is the doer of the action in the sentence.

The action itself will be encapsulated by the verb, which is the action word that describes what the doer does.

The object of the sentence follows the verb and describes that which receives the action.

This is again best illustrated by an example. Take a look at the simple sentence below:

Tom ate many cookies.

In this easy example, the doer of the action is Tom , the action is ate , and the receiver of the action is the many cookies .

Subject = Tom

Object = many cookies

After some practice, students will become adept at recognizing SVO sentences and forming their own. It’s also important to point out that simple sentences don’t necessarily have to be short.

This research reveals that an active lifestyle can have a great impact for the good on the life expectancy of the average person.

Despite this sentence looking more sophisticated (and longer!), this is still a simple sentence as it follows the SVO structure:

Subject = research

Verb = reveals

Object = that an active lifestyle can have a great impact for the good on the life expectancy of the average person.

Though basic in construction, it is essential to note that a simple sentence is often the perfect structure for dealing with complex ideas. Simple sentences can effectively provide clarity and efficiency of expression, breaking down complex concepts into manageable chunks.

MORE SIMPLE SENTENCE EXAMPLES

- She ran to the store.

- The sun is shining.

- He likes to read books.

- The cat is sleeping.

- I am happy.

Simple Sentence Reinforcement Activity

To ensure your students grasp the simple sentence structure, have them read a photocopied text pitched at a language level suited to their age and ability.

On the first run-through, have students identify and highlight simple sentences in the text. Then, students should use various colors of pens to pick out and underline the subject, the verb, and the object in each sentence.

This activity helps ensure a clear understanding of how this structure works and helps to internalize it. This will reap rich rewards for students when they come to the next stage, and it’s time for them to write their own sentences using this basic pattern.

After students have mastered combining subjects, verbs, and objects into both long and short sentences, they will be ready to move on to the other three types of sentences, the next of which is the compound sentence .

EXAMPLES OF SIMPLE, COMPLEX AND COMPOUND SENTENCES

Compound sentence s.

While simple sentences consist of one clause with a subject and a verb, compound sentences combine at least two independent clauses that are joined together with a coordinating conjunction .

There’s a helpful acronym to help students remember these coordinating conjunctions; FANBOYS .

Some conjunctions will be more frequently used than others, with the most commonly used being and , but , or , and so .

Whichever of the conjunctions the student chooses, it will connect the two halves of the compound sentence – each of which could stand alone as a complete sentence.

Compound sentences are an essential way of bringing variety and rhythm to a piece of writing. The decision to join two sentences together into one longer compound sentence is made because there is a strong relationship between the two. Still, it is important to remind students that they need not necessarily be joined as they can remain as separate sentences.

The decision to join or not is often a stylistic one.

For example, the two simple sentences:

1. She ran to the school.

2. The school was closed.

It can be easily joined together with a coordinating conjunction that reveals an essential relationship between the two:

She ran to the school, but the school was closed.

As a bonus, while working on compound sentences, a convenient opportunity arises to introduce the correct usage of the semicolon. Often, where two clauses are joined with a conjunction, that conjunction can be replaced with a semicolon when the two parts of the sentence are related, for example:

She ran to the school; the school was closed.

While you may not wish to muddy the waters by introducing the semicolon while dealing with compound sentences, more advanced students may benefit from making the link here.

MORE COMPOUND SENTENCE EXAMPLES

- I want to go to the beach this weekend, but I also need to finish my homework.

- She loves to sing and dance, so she decided to audition for the school musical.

- I enjoy reading books, and my brother prefers to watch movies.

- The dog barked at the mailman, and the mailman quickly walked away.

- He ate his breakfast, and then he went for a run in the park.

Reinforcement Activity:

A good way for students to practice forming compound sentences is to provide them with copies of simple books from early on in a reading scheme. Books for emergent readers are often written in simple sentences that form repetitive patterns that help children internalize various language patterns.

Challenge your students to rewrite some of these texts using compound sentences where appropriate. This will provide valuable practice in spotting such opportunities in their writing and experience in selecting the appropriate conjunction.

COMPLEX SENTENCES

There are various ways to construct complex sentences, but essentially any complex sentence will contain at least one independent and one dependent clause. However, these clauses are not joined by coordinating conjunctions. Instead, subordinating conjunctions are used.

Here are some examples of subordinating conjunctions:

● after

● although

● as

● as long as

● because

● before

● even if

● if

● in order to

● in case

● once

● that

● though

● until

● when

● whenever

● wherever

● while

Subordinating conjunctions join dependent and independent clauses together. They provide a transition between the two ideas in the sentence. This transition will involve a time, place, or a cause and effect relationship. The more important idea is contained in the sentence’s main clause, while the less important idea is introduced by the subordinating conjunction.

Although Catherine ran to school , she didn’t get there in time.

We can see that the first part of this complex sentence (in bold ) is a dependent clause that cannot stand alone. This fragment begins with the subordinating conjunction ‘although’ which joins it to, and expresses the relationship with, the independent clause which follows.

When complex sentences are organized this way (with the dependent clause first), you’ll note the comma separates the dependent clause from the independent clause. If the structure is reorganized to place the independent clause first, with the dependent clause following, then there is no need for this comma.

You will not do well if you refuse to study.

Complex sentences can be great tools for students to not only bring variety to their writing but to explore complex ideas, set up comparisons and contrasts, and convey cause and effect.

MORE COMPLEX SENTENCE EXAMPLES

- Despite feeling exhausted from a long day at work, she still managed to summon the energy to cook a delicious dinner for her family.

- In order to fully appreciate the beauty of the artwork, one must take the time to examine it closely and consider the artist’s intentions.

- The new student, who had just moved to the city from a small town, felt overwhelmed by the size and complexity of her new school.

- Although he had studied diligently for weeks, he was still nervous about the upcoming exam, knowing that his entire future depended on his performance.

- As the sun began to set, the birds flew back to their nests, signalling the end of another day and the beginning of a peaceful evening.

Reinforcement Activity

A helpful way to practice writing complex sentences is to provide students with a subordinating conjunction and dependent clause and challenge them to provide a suitable independent clause to finish out the sentence.

After returning home for work,…

Although it was late,…

You may also flip this and provide the independent clause first before challenging them to come up with a suitable dependent clause and subordinating conjunction to finish out the sentence.

Daily Quick Writes For All Text Types

Our FUN DAILY QUICK WRITE TASKS will teach your students the fundamentals of CREATIVE WRITING across all text types. Packed with 52 ENGAGING ACTIVITIES

COMPOUND-COMPLEX SENTENCES

Compound-complex sentences are, not surprisingly, the most difficult for students to write well. If, however, your students have put the work in to gain a firm grasp of the preceding three sentence types, then they should manage these competently with a bit of practice.

Before teaching compound-complex sentences, it’ll be worth asking your students if they can make an educated guess at a definition of this type of sentence based on its title alone.

The more astute among your students may well be able to work out that a compound-complex sentence refers to joining a compound sentence with a complex one. More accurately, a compound-complex sentence combines at least two independent clauses and one dependent clause.

Since the school was closed, Sarah ran home and her mum made her some breakfast.

We can see here the sentence begins with a dependent clause followed by a compound sentence. We can also see a complex sentence nestled there if we look at the bracketed content in the version below.

( Since the school was closed, Sarah ran home ) and her mum made her some breakfast.

This is a fairly straightforward example of complex sentences, but they can come in lots of guises, containing lots more information while still conforming to the compound-complex structure.

Because most visitors to the city regularly miss out on the great bargains available here, local companies endeavor to attract tourists to their businesses and help them understand how to access the best deals the capital has to offer.

A lot is going on in this sentence, but it follows the same structure as the previous one on closer examination. That is, it opens with a dependent clause (that starts with subordinating conjunction) and is then followed by a compound sentence.

With practice, your students will soon be able to quickly identify these more sophisticated types of sentences and produce their own examples.

Compound-complex sentences can bring variety to a piece of writing and help articulate complex things. However, it is essential to encourage students to pay particular attention to the placement of commas in these sentences to ensure readers do not get confused. Encourage students to proofread all their writing, especially when writing longer, more structurally sophisticated sentences such as these.

MORE COMPOUND-COMPLEX SENTENCE EXAMPLES

- Despite the fact that he was exhausted from his long day at work, he went to the gym and completed a gruelling hour-long workout, but he still managed to make it home in time for dinner with his family.

- The orchestra played beautifully, filling the concert hall with their harmonious melodies, yet the soloist stole the show with her hauntingly beautiful rendition of the final movement.

- Although the road was treacherous and steep, the hiker persevered through the difficult terrain, and after several hours, she reached the summit and was rewarded with a breathtaking view of the valley below.

- The chef prepared a mouth-watering feast, consisting of a savory roast beef, a colorful array of fresh vegetables, and a decadent chocolate cake for dessert, yet the dinner party was still overshadowed by the heated political debate.

- After a long and tiring day, the student sat down to study for her final exam, but she couldn’t concentrate because her mind was consumed with worries about her future, so she decided to take a break and go for a run to clear her head.

Regenerate response

You could begin reinforcing student understanding of compound-complex sentences by providing them with a handout featuring several examples of this type of sentence.

Working in pairs or small groups, have the students identify and mark the independent clauses (more than 1) and dependent clauses (at least 1) in each sentence. When students can do this confidently, they can then begin to attempt to compose their own sentences.

Another good activity that works well as a summary of sentence structure work is to provide the students with a collection of jumbled sentences of each of the four types.

Challenge the students to sort the sentences into each of the four types. In a plenary, compare each group’s findings and examine those sentences where the groups disagreed on their categorization.

In teaching sentence structure, it is essential to emphasize to our students that though the terminology may seem quite daunting at first, they will quickly come to understand how each structure works and recognize them when they come across them in a text.

Much of this is often done by feel, especially for native English speakers. Just as someone may be a competent cyclist and struggle to explain the process verbally, grammar can sometimes feel like a barrier to doing.

Be sure to make lots of time for students to bridge the gap between the theoretical and the practical by offering opportunities to engage in activities that allow students to get creative in producing their own sentences.

WRITING CHECKLISTS FOR ALL TEXT TYPES

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (92 Reviews)

WHAT IS A SENTENCE FRAGMENT?

A sentence fragment is a collection of words that looks similar to a sentence but actually isn’t a complete sentence. Sentence fragments usually lack a subject or verb or don’t express a complete thought. Whilst a fragmented sentence can be punctuated to appear similar to a complete sentence; it is no substitute for a sentence.

Sentence fragment features:

These are the distinguishing features of a sentence fragment:

- Example: Jumped further than a Kangaroo. (Who jumped?)

- Example: My favorite math teacher. (What did the teacher do or say?)

- Example: For better or worse. (What is better or worse? What is it modifying?)

- Example: When my mother married my father. (What happened when “my mother married my father?”)

- Example: Such as, my brother was practising martial arts. (It is unclear; did something happen when my brother was practising martial arts?)

The methods for correcting a sentence fragment are varied, but essentially it will boil down to three options. Either attach it to a nearby sentence, revise and add the missing elements or rewrite the entire passage or fragment until they are operating in sync with each other.

Let’s explore some of these methods to fix a fragmented sentence. Firstly, one must identify the subject and verb to ensure that the fragment contains the necessary components of a complete sentence. For instance, in the sentence “Running down the street, I saw a dog,” the subject (“I”) and verb (“saw”) are present, making it a complete sentence.

Furthermore, it is important to check for a complete thought within the sentence fragment. In other words, the fragment should express a complete idea; if it doesn’t, it should be revised accordingly. An example of a sentence fragment with a complete thought is “Running down the street, I saw a dog chasing a cat.”

Lastly, combining sentence fragments with independent clauses can help create complete sentences. For instance, “Running down the street, I saw a dog. It was chasing a cat” can be combined into one sentence: “Running down the street, I saw a dog chasing a cat.” This not only creates a complete sentence but also enhances the overall coherence and readability of the text.

In summary, sentence fragments can hinder effective communication and must be avoided in writing. To fix a sentence fragment, one must identify the subject and verb, ensure a complete thought is expressed, and consider combining it with an independent clause. By doing so, writers can create clear, concise, and meaningful sentences that easily convey their intended message.

TOP TIPS FOR TEACHING SENTENCE STRUCTURE

- Start with the basics: Begin by teaching students about the different parts of a sentence, such as subject, verb, and object. Use examples and visual aids to help them understand the function of each part.

- Use varied sentence structures: Show students examples of different sentence structures, such as simple, compound, and complex sentences. Please encourage them to use varied sentence structures in their writing.

- Practice with sentence combining: Give students several short, simple sentences and ask them to combine them into a longer sentence using conjunctions or other connecting words. This exercise will help them understand how to construct complex sentences.

- Use real-life examples: Incorporate examples from everyday life to help students understand how sentence structure affects meaning. For example, “I saw the man with the telescope” and “I saw the man, with the telescope” have different meanings due to the placement of the comma.

- Provide feedback: Give students feedback on their writing, focusing on the structure of their sentences. Encourage them to revise and improve their writing by experimenting with different sentence structures. Please provide specific examples of how they can improve their sentence structure.

SENTENCE STRUCTURE VIDEO TUTORIALS

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES RELATED TO SENTENCE STRUCTURE

Glossary of literary terms

The Writing Process

Perfect Paragraph Writing: The Ultimate Guide

Teaching Proofreading and Editing Skills

How to write a perfect 5 Paragraph Essay

Northern Illinois University Effective Writing Practices Tutorial

- Make a Gift

- MyScholarships

- Huskie Link

- Anywhere Apps

- Huskies Get Hired

- Student Email

- Password Self-Service

- Quick Links

- Effective Writing Practices Tutorial

- Sentence Structure

Vary sentence structure in writing so that what you write doesn't look like a list of things on the one hand or a long winding sentence that might never end on the other hand.

Varying sentence structure keeps your writing alive and readers interested . As Andrea Lunsford indicates, "Constant uniformity in anything, in fact, soon gets tiresome, while its opposite, variation, is usually pleasing to readers. Variety is important in sentence structures because too much uniformity results in dull listless prose" (189).

Monotonous tone can be avoided by varying:

- sentence types

- sentence openings

- sentence length (Lunsford, 190-191).

Sentence Types

The easiest way to bore readers is to use simple Subject + Verb structure in all sentences. Consider the following example:

Vincent van Gogh was born in the southern Netherlands in 1853 to the family of a Dutch church minister. He started working as an art dealer at the early age of fifteen. He worked there for five years. Vincent fell in love with one of the girls at his boarding house. He finally decided to confess his love for her, but she rejected him. He was devastated. Vincent quit the art gallery and decided that his true passion was to become a pastor.

He lived with his relatives for a while in Amsterdam and prepared to study theology at the university. Vincent failed in his studies. He then worked as a missionary in a coal-mining village in Belgium for a year. His missionary work unfortunately didn't bring him closer to becoming a pastor. Vincent often turned to drawing when life proved hard. He liked to portray the everyday life of ordinary people. In this period, he produced one of his early famous paintings "The Potato Eaters."

Here's a revised version which has a combination of simple , compound , and complex sentences:

Born to the family of a Dutch church minister in the southern Netherlands in 1853, Vincent van Gogh received his first exposure to art at the age of fifteen when he started working as an art dealer. Saddened by unrequited love, Vincent quit the gallery after only five years and turned to religion, setting his goals on becoming a pastor.

For a while, he lived with his relatives in Amsterdam preparing for the study of theology. Despite his passion and hard work, Vincent failed at his studies. Undeterred by his failure to get into the university, Vincent continued his pursuit of religion as a missionary in a coal-mining village in Belgium. He often drew to escape the harsh reality of life in this impoverished region. The everyday life of ordinary people seemed to attract his attention the most. It was during this period that he produced one of the most famous paintings of his early career, "The Potato Eaters."

A combination of simple, compound, and complex sentences not only makes the flow of information more interesting, but it also improves the readability of the passage.

If sentences in a paragraph begin with the same opening subject, the writing becomes monotonous.

In the previous example, we saw a lot of repetitions of the pronoun he . To avoid this monotonous effect, start the sentences with adverb modifiers or clauses, transitional expressions, prepositional or infinitive phrases .

Rule to Remember

Vary your sentences by starting them with adverb modifiers or clauses, transitional expressions, prepositional or Infinitive phrases.

Adverb modifier

Relentlessly , the artist worked on his sketching technique until it was perfected.

Adverb Clause

Until his style improved , the artist spent most of the time perfecting his sketching technique.

Infinitive Phrase

To achieve perfection , the artist worked relentlessly on his sketching technique.

Transitional Expressions

He was a promising artist. However , he still needed to work a lot on his sketching technique.

Sentence Length

Varying sentence length can help keep the rhythm in writing. A succession of long sentences should be interrupted from time to time with a few short ones to keep readers' interest alive.

On the other hand, don't keep all your sentences short or your paragraph will look like a list. Consider the following example:

The Renaissance was a cultural movement. It lasted from the 14th until the 17th century. Its biggest representatives were Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

There are many ways to combine short sentences. You can use either a coordinating or a subordinating conjunction, introduce a dependent clause, a participial or prepositional phrase, or use an appositive.

Combining clauses by introducing a dependent clause :

The Renaissance was a cultural movement which lasted from the 14th until the 17th century . Its biggest representatives were Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

Combining sentences using an appositive :

The Renaissance, a cultural movement between the 14th and 17th century , produced some of most famous artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

In summary, vary your sentence structure to avoid monotony and keep your readers' interest.

- Punctuation

- Organization

- General Document Format

- Formatting Visuals

- In-text Citations

- List of Sources

- Bias-free Language

- Formal and Informal Style

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.1 Sentence Variety

Learning objectives.

- Identify ways to vary sentence structure.

- Write and revise sentence structure at the beginning of sentences.

- Write and revise sentence structure by connecting ideas.

Have you ever ordered a dish in a restaurant and been not happy with its taste, even though it contained most of your favorite ingredients? Just as a meal might lack the finishing touches needed to spice it up, so too might a paragraph contain all the basic components but still lack the stylistic finesse required to engage a reader. Sometimes writers have a tendency to reuse the same sentence pattern throughout their writing. Like any repetitive task, reading text that contains too many sentences with the same length and structure can become monotonous and boring. Experienced writers mix it up by using an assortment of sentence patterns, rhythms, and lengths.

In this chapter, you will follow a student named Naomi who has written a draft of an essay but needs to refine her writing. This section discusses how to introduce sentence variety into writing, how to open sentences using a variety of techniques, and how to use different types of sentence structure when connecting ideas. You can use these techniques when revising a paper to bring life and rhythm to your work. They will also make reading your work more enjoyable.

Incorporating Sentence Variety

Experienced writers incorporate sentence variety into their writing by varying sentence style and structure. Using a mixture of different sentence structures reduces repetition and adds emphasis to important points in the text. Read the following example:

During my time in office I have achieved several goals. I have helped increase funding for local schools. I have reduced crime rates in the neighborhood. I have encouraged young people to get involved in their community. My competitor argues that she is the better choice in the upcoming election. I argue that it is ridiculous to fix something that isn’t broken. If you reelect me this year, I promise to continue to serve this community.

In this extract from an election campaign, the writer uses short, simple sentences of a similar length and style. Writers often mistakenly believe that this technique makes the text more clear for the reader, but the result is a choppy, unsophisticated paragraph that does not grab the audience’s attention. Now read the revised paragraph with sentence variety:

During my time in office, I have helped increase funding for local schools, reduced crime rates in the neighborhood, and encouraged young people to get involved in their community. Why fix what isn’t broken? If you reelect me this year, I will continue to achieve great things for this community. Don’t take a chance on an unknown contender; vote for the proven success.

Notice how introducing a short rhetorical question among the longer sentences in the paragraph is an effective means of keeping the reader’s attention. In the revised version, the writer combines the choppy sentences at the beginning into one longer sentence, which adds rhythm and interest to the paragraph.

Effective writers often implement the “rule of three,” which is basically the thought that things that contain three elements are more memorable and more satisfying to readers than any other number. Try to use a series of three when providing examples, grouping adjectives, or generating a list.

Combine each set of simple sentences into a compound or a complex sentence. Write the combined sentence on your own sheet of paper.

- Heroin is an extremely addictive drug. Thousands of heroin addicts die each year.

- Shakespeare’s writing is still relevant today. He wrote about timeless themes. These themes include love, hate, jealousy, death, and destiny.

- Gay marriage is now legal in six states. Iowa, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine all permit same-sex marriage. Other states are likely to follow their example.

- Prewriting is a vital stage of the writing process. Prewriting helps you organize your ideas. Types of prewriting include outlining, brainstorming, and idea mapping.

- Mitch Bancroft is a famous writer. He also serves as a governor on the local school board. Mitch’s two children attend the school.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Using Sentence Variety at the Beginning of Sentences

Read the following sentences and consider what they all have in common:

John and Amanda will be analyzing this week’s financial report.

The car screeched to a halt just a few inches away from the young boy.

Students rarely come to the exam adequately prepared.

If you are having trouble figuring out why these sentences are similar, try underlining the subject in each. You will notice that the subject is positioned at the beginning of each sentence— John and Amanda , the car , students . Since the subject-verb-object pattern is the simplest sentence structure, many writers tend to overuse this technique, which can result in repetitive paragraphs with little sentence variety.

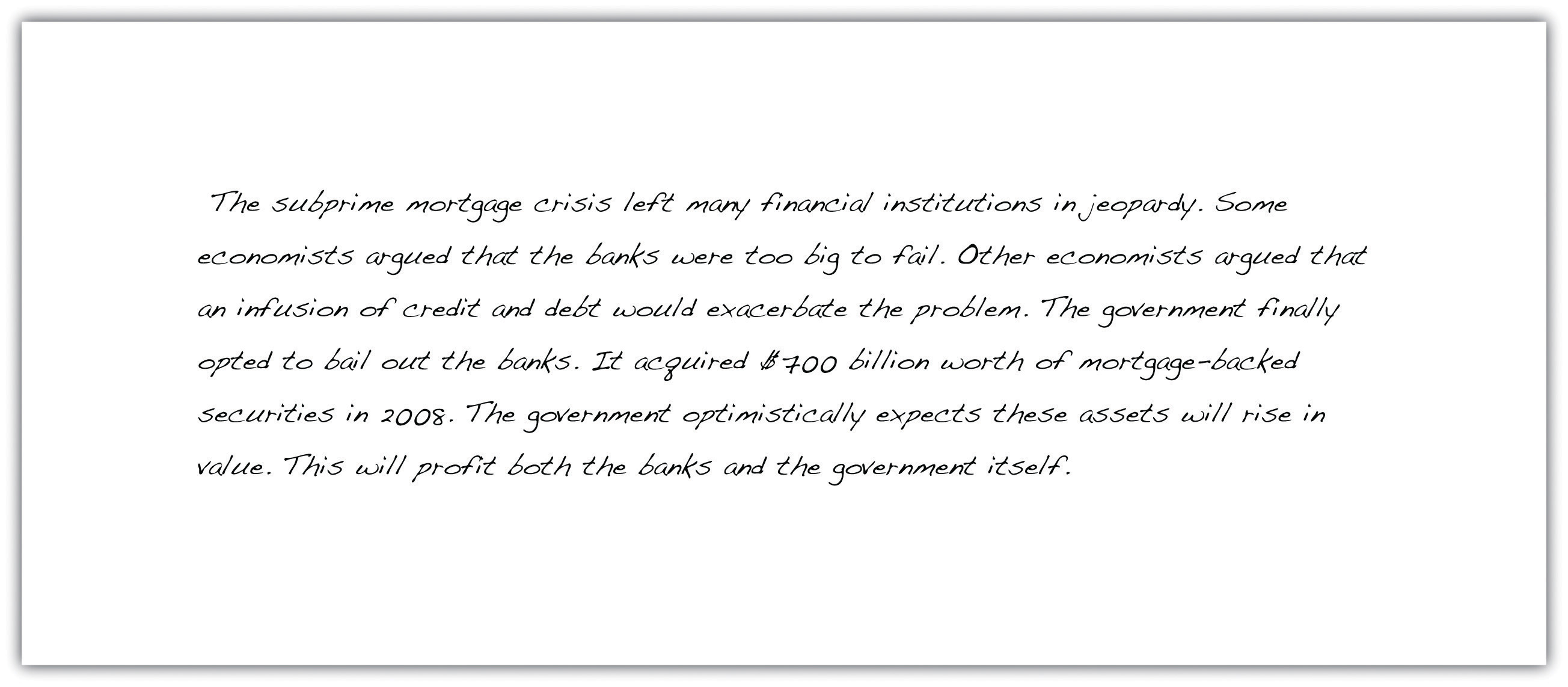

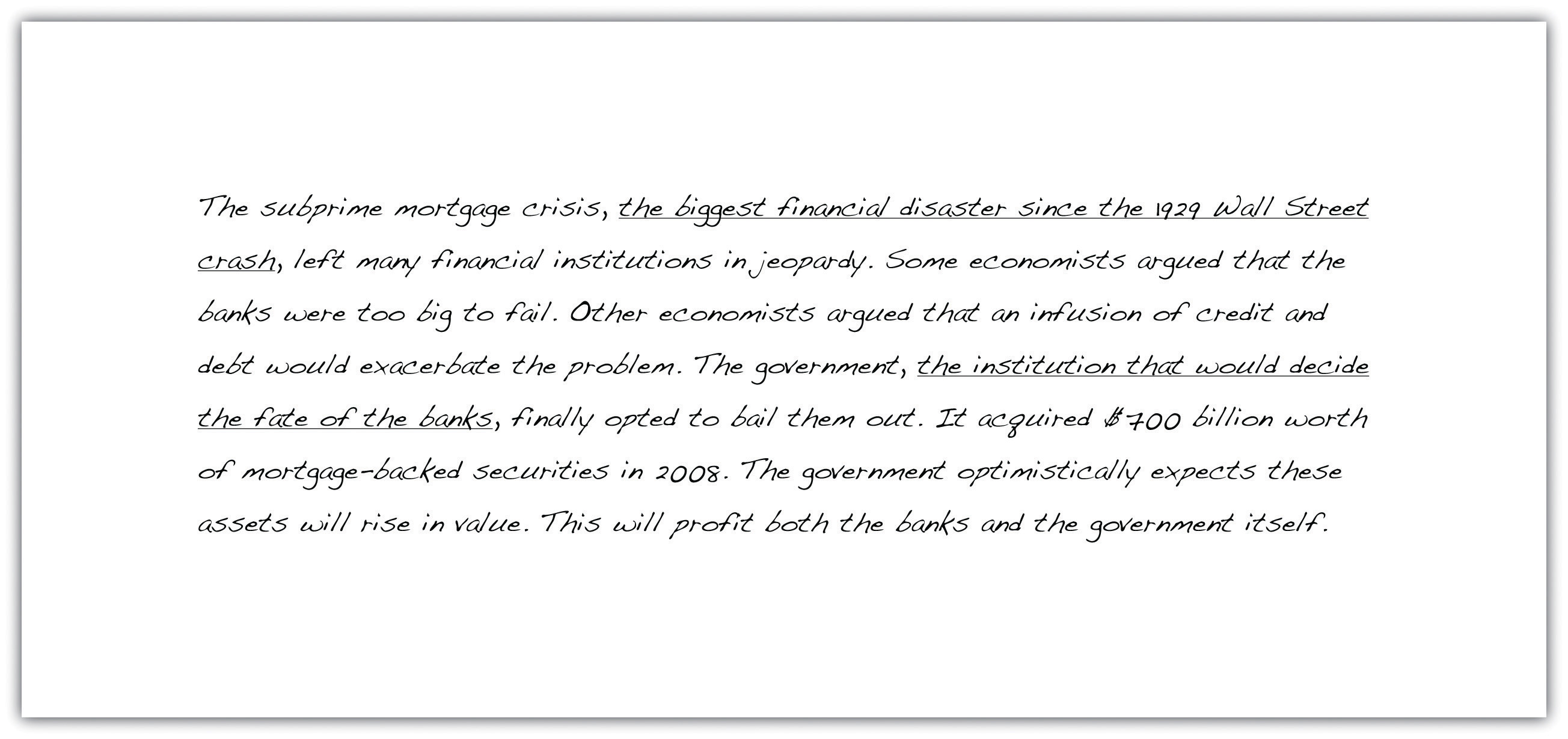

Naomi wrote an essay about the 2008 government bailout. Read this excerpt from Naomi’s essay:

This section examines several ways to introduce sentence variety at the beginning of sentences, using Naomi’s essay as an example.

Starting a Sentence with an Adverb

One technique you can use so as to avoid beginning a sentence with the subject is to use an adverb. An adverb is a word that describes a verb, adjective, or other adverb and often ends in – ly . Examples of adverbs include quickly , softly , quietly , angrily , and timidly . Read the following sentences:

She slowly turned the corner and peered into the murky basement.

Slowly, she turned the corner and peered into the murky basement.

In the second sentence, the adverb slowly is placed at the beginning of the sentence. If you read the two sentences aloud, you will notice that moving the adverb changes the rhythm of the sentence and slightly alters its meaning. The second sentence emphasizes how the subject moves—slowly—creating a buildup of tension. This technique is effective in fictional writing.

Note that an adverb used at the beginning of a sentence is usually followed by a comma. A comma indicates that the reader should pause briefly, which creates a useful rhetorical device. Read the following sentences aloud and consider the effect of pausing after the adverb:

Cautiously, he unlocked the kennel and waited for the dog’s reaction.

Solemnly, the policeman approached the mayor and placed him under arrest.

Suddenly, he slammed the door shut and sprinted across the street.

In an academic essay, moving an adverb to the beginning of a sentence serves to vary the rhythm of a paragraph and increase sentence variety.

Naomi has used two adverbs in her essay that could be moved to the beginning of their respective sentences. Notice how the following revised version creates a more varied paragraph:

Adverbs of time—adverbs that indicate when an action takes place—do not always require a comma when used at the beginning of a sentence. Adverbs of time include words such as yesterday , today , later , sometimes , often , and now .

On your own sheet of paper, rewrite the following sentences by moving the adverbs to the beginning.

- The red truck sped furiously past the camper van, blaring its horn.

- Jeff snatched at the bread hungrily, polishing off three slices in under a minute.

- Underage drinking typically results from peer pressure and lack of parental attention.

- The firefighters bravely tackled the blaze, but they were beaten back by flames.

- Mayor Johnson privately acknowledged that the budget was excessive and that further discussion was needed.

Starting a Sentence with a Prepositional Phrase

A prepositional phrase is a group of words that behaves as an adjective or an adverb, modifying a noun or a verb. Prepositional phrases contain a preposition (a word that specifies place, direction, or time) and an object of the preposition (a noun phrase or pronoun that follows the preposition).

Table 7.1 Common Prepositions

Read the following sentence:

The terrified child hid underneath the table .

In this sentence, the prepositional phrase is underneath the table. The preposition underneath relates to the object that follows the preposition— the table . Adjectives may be placed between the preposition and the object in a prepositional phrase.

The terrified child hid underneath the heavy wooden table .

Some prepositional phrases can be moved to the beginning of a sentence in order to create variety in a piece of writing. Look at the following revised sentence:

Underneath the heavy wooden table , the terrified child hid.

Notice that when the prepositional phrase is moved to the beginning of the sentence, the emphasis shifts from the subject—the terrified child—to the location in which the child is hiding. Words that are placed at the beginning or end of a sentence generally receive the greatest emphasis. Take a look at the following examples. The prepositional phrase is underlined in each:

The bandaged man waited in the doctor’s office .

In the doctor’s office , the bandaged man waited.

My train leaves the station at 6:45 a.m .

At 6:45 a.m. , my train leaves the station.

Teenagers exchange drugs and money under the railway bridge .

Under the railway bridge , teenagers exchange drugs and money.

Prepositional phrases are useful in any type of writing. Take another look at Naomi’s essay on the government bailout.

Now read the revised version.

The underlined words are all prepositional phrases. Notice how they add additional information to the text and provide a sense of flow to the essay, making it less choppy and more pleasurable to read.

Unmovable Prepositional Phrases

Not all prepositional phrases can be placed at the beginning of a sentence. Read the following sentence:

I would like a chocolate sundae without whipped cream .

In this sentence, without whipped cream is the prepositional phrase. Because it describes the chocolate sundae, it cannot be moved to the beginning of the sentence. “Without whipped cream I would like a chocolate sundae” does not make as much (if any) sense. To determine whether a prepositional phrase can be moved, we must determine the meaning of the sentence.

Overuse of Prepositional Phrases

Experienced writers often include more than one prepositional phrase in a sentence; however, it is important not to overload your writing. Using too many modifiers in a paragraph may create an unintentionally comical effect as the following example shows:

The treasure lay buried under the old oak tree, behind the crumbling fifteenth-century wall, near the schoolyard, where children played merrily during their lunch hour, unaware of the riches that remained hidden beneath their feet.

A sentence is not necessarily effective just because it is long and complex. If your sentence appears cluttered with prepositional phrases, divide it into two shorter sentences. The previous sentence is far more effective when written as two simpler sentences:

The treasure lay buried under the old oak tree, behind the crumbling fifteenth-century wall. In the nearby schoolyard, children played merrily during their lunch hour, unaware of the riches that remained hidden beneath their feet.

Writing at Work

The overuse of prepositional phrases often occurs when our thoughts are jumbled and we are unsure how concepts or ideas relate to one another. If you are preparing a report or a proposal, take the time to organize your thoughts in an outline before writing a rough draft. Read the draft aloud, either to yourself or to a colleague, and identify areas that are rambling or unclear. If you notice that a particular part of your report contains several sentences over twenty words, you should double check that particular section to make certain that it is coherent and does not contain unnecessary prepositional phrases. Reading aloud sometimes helps detect unclear and wordy sentences. You can also ask a colleague to paraphrase your main points to ensure that the meaning is clear.

Starting a Sentence by Inverting Subject and Verb

As we noted earlier, most writers follow the subject-verb-object sentence structure. In an inverted sentence , the order is reversed so that the subject follows the verb. Read the following sentence pairs:

- A truck was parked in the driveway.

- Parked in the driveway was a truck.

- A copy of the file is attached.

- Attached is a copy of the file.

Notice how the second sentence in each pair places more emphasis on the subject— a truck in the first example and the file in the second. This technique is useful for drawing the reader’s attention to your primary area of focus. We can apply this method to an academic essay. Take another look at Naomi’s paragraph.

To emphasize the subject in certain sentences, Naomi can invert the traditional sentence structure. Read her revised paragraph:

Notice that in the first underlined sentence, the subject ( some economists ) is placed after the verb ( argued ). In the second underlined sentence, the subject ( the government ) is placed after the verb ( expects ).

On your own sheet of paper, rewrite the following sentences as inverted sentences.

- Teresa will never attempt to run another marathon.

- A detailed job description is enclosed with this letter.

- Bathroom facilities are across the hall to the left of the water cooler.

- The well-dressed stranger stumbled through the doorway.

- My colleagues remain unconvinced about the proposed merger.

Connecting Ideas to Increase Sentence Variety

Reviewing and rewriting the beginning of sentences is a good way of introducing sentence variety into your writing. Another useful technique is to connect two sentences using a modifier, a relative clause, or an appositive. This section examines how to connect ideas across several sentences in order to increase sentence variety and improve writing.

Joining Ideas Using an – ing Modifier

Sometimes it is possible to combine two sentences by converting one of them into a modifier using the – ing verb form— singing , dancing , swimming . A modifier is a word or phrase that qualifies the meaning of another element in the sentence. Read the following example:

Original sentences: Steve checked the computer system. He discovered a virus.

Revised sentence: Checking the computer system, Steve discovered a virus.

To connect two sentences using an – ing modifier, add – ing to one of the verbs in the sentences ( checking ) and delete the subject ( Steve ). Use a comma to separate the modifier from the subject of the sentence. It is important to make sure that the main idea in your revised sentence is contained in the main clause, not in the modifier. In this example, the main idea is that Steve discovered a virus, not that he checked the computer system.

In the following example, an – ing modifier indicates that two actions are occurring at the same time:

Noticing the police car, she shifted gears and slowed down.

This means that she slowed down at the same time she noticed the police car.

Barking loudly, the dog ran across the driveway.

This means that the dog barked as it ran across the driveway.

You can add an – ing modifier to the beginning or the end of a sentence, depending on which fits best.

Beginning: Conducting a survey among her friends , Amanda found that few were happy in their jobs.

End: Maria filed the final report, meeting her deadline .

Dangling Modifiers

A common mistake when combining sentences using the – ing verb form is to misplace the modifier so that it is not logically connected to the rest of the sentence. This creates a dangling modifier . Look at the following example:

Jogging across the parking lot, my breath grew ragged and shallow.

In this sentence, jogging across the parking lot seems to modify my breath . Since breath cannot jog, the sentence should be rewritten so that the subject is placed immediately after the modifier or added to the dangling phrase.

Jogging across the parking lot, I felt my breath grow ragged and shallow.

For more information on dangling modifiers, see Chapter 2 “Writing Basics: What Makes a Good Sentence?” .

Joining Ideas Using an – ed Modifier

Some sentences can be combined using an – ed verb form— stopped , finished , played . To use this method, one of the sentences must contain a form of be as a helping verb in addition to the – ed verb form. Take a look at the following example:

Original sentences: The Jones family was delayed by a traffic jam. They arrived several hours after the party started.

Revised sentence: Delayed by a traffic jam, the Jones family arrived several hours after the party started.

In the original version, was acts as a helping verb —it has no meaning by itself, but it serves a grammatical function by placing the main verb ( delayed ) in the perfect tense.

To connect two sentences using an – ed modifier, drop the helping verb ( was ) and the subject ( the Jones family ) from the sentence with an – ed verb form. This forms a modifying phrase ( delayed by a traffic jam ) that can be added to the beginning or end of the other sentence according to which fits best. As with the – ing modifier, be careful to place the word that the phrase modifies immediately after the phrase in order to avoid a dangling modifier.

Using – ing or – ed modifiers can help streamline your writing by drawing obvious connections between two sentences. Take a look at how Naomi might use modifiers in her paragraph.

The revised version of the essay uses the – ing modifier opting to draw a connection between the government’s decision to bail out the banks and the result of that decision—the acquisition of the mortgage-backed securities.

Joining Ideas Using a Relative Clause

Another technique that writers use to combine sentences is to join them using a relative clause. A relative clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb and describes a noun. Relative clauses function as adjectives by answering questions such as which one? or what kind? Relative clauses begin with a relative pronoun, such as who , which , where , why , or when . Read the following examples:

Original sentences: The managing director is visiting the company next week. He lives in Seattle.

Revised sentence: The managing director, who lives in Seattle, is visiting the company next week.

To connect two sentences using a relative clause, substitute the subject of one of the sentences ( he ) for a relative pronoun ( who ). This gives you a relative clause ( who lives in Seattle ) that can be placed next to the noun it describes ( the managing director ). Make sure to keep the sentence you want to emphasize as the main clause. For example, reversing the main clause and subordinate clause in the preceding sentence emphasizes where the managing director lives, not the fact that he is visiting the company.

Revised sentence: The managing director, who is visiting the company next week, lives in Seattle.

Relative clauses are a useful way of providing additional, nonessential information in a sentence. Take a look at how Naomi might incorporate relative clauses into her essay.

Notice how the underlined relative clauses can be removed from Naomi’s essay without changing the meaning of the sentence.

To check the punctuation of relative clauses, assess whether or not the clause can be taken out of the sentence without changing its meaning. If the relative clause is not essential to the meaning of the sentence, it should be placed in commas. If the relative clause is essential to the meaning of the sentence, it does not require commas around it.

Joining Ideas Using an Appositive

An appositive is a word or group of words that describes or renames a noun or pronoun. Incorporating appositives into your writing is a useful way of combining sentences that are too short and choppy. Take a look at the following example:

Original sentences: Harland Sanders began serving food for hungry travelers in 1930. He is Colonel Sanders or “the Colonel.”

Revised sentence: Harland Sanders, “the Colonel,” began serving food for hungry travelers in 1930.

In the revised sentence, “the Colonel” is an appositive because it renames Harland Sanders. To combine two sentences using an appositive, drop the subject and verb from the sentence that renames the noun and turn it into a phrase. Note that in the previous example, the appositive is positioned immediately after the noun it describes. An appositive may be placed anywhere in a sentence, but it must come directly before or after the noun to which it refers:

Appositive after noun: Scott, a poorly trained athlete, was not expected to win the race.

Appositive before noun: A poorly trained athlete, Scott was not expected to win the race.

Unlike relative clauses, appositives are always punctuated by a comma or a set commas. Take a look at the way Naomi uses appositives to include additional facts in her essay.

On your own sheet of paper, rewrite the following sentence pairs as one sentence using the techniques you have learned in this section.

- Baby sharks are called pups. Pups can be born in one of three ways.

- The Pacific Ocean is the world’s largest ocean. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south.

- Michael Phelps won eight gold medals in the 2008 Olympics. He is a champion swimmer.

- Ashley introduced her colleague Dan to her husband, Jim. She speculated that the two of them would have a lot in common.

- Cacao is harvested by hand. It is then sold to chocolate-processing companies at the Coffee, Sugar, and Cocoa Exchange.

In addition to varying sentence structure, consider varying the types of sentences you are using in a report or other workplace document. Most sentences are declarative, but a carefully placed question, exclamation, or command can pique colleagues’ interest, even if the subject material is fairly dry. Imagine that you are writing a budget analysis. Beginning your report with a rhetorical question, such as “Where is our money going?” or “How can we increase sales?” encourages people to continue reading to find out the answers. Although they should be used sparingly in academic and professional writing, questions or commands are effective rhetorical devices.

Key Takeaways

- Sentence variety reduces repetition in a piece of writing and adds emphasis to important points in the text.

- Sentence variety can be introduced to the beginning of sentences by starting a sentence with an adverb, starting a sentence with a prepositional phrase, or by inverting the subject and verb.

- Combine ideas, using modifiers, relative clauses, or appositives, to achieve sentence variety.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Sentence Patterns

What this handout is about.

This handout gives an overview of English sentence patterns. It will help you identify subjects, verbs, and clause connectors so you can analyze your writing style and improve it by using a variety of sentence patterns. Click here for a one page summary of the English sentence patterns discussed on this handout.

Subjects, Verbs, and Clauses

In its simplest form, an English sentence has two parts: a subject and a verb that express a complete thought when they are together.

- The subject shows who or what is doing the action. It is always some form of noun or pronoun.

- The verb shows the action or the state of being. It can be an action verb, like “run,” or a state verb, like “seem.”

Examples of simple two word sentences include:

Marvin slept.

Isotopes react.

Real sentences are rarely so short. We usually want to convey much more information, so we modify the main subject and verb with other words and phrases, as in the sentences below:

Unfortunately, Marvin slept fitfully.

Dogs bark louder after midnight.

Heavy isotopes react more slowly than light isotopes of the same element.

Despite the extra information, each of these sentences has one subject and one verb, so it’s still just one clause. What’s a clause?

A clause is the combination of a subject and a verb. When you have a subject and verb, you have a clause. Pretty easy, isn’t it? We’re going to concentrate on clauses in this handout, with emphasis on these two in particular:

- Independent clause: a subject and verb that make a complete thought. Independent clauses are called independent because they can stand on their own and make sense.

- Dependent clause: a subject and verb that don’t make a complete thought. Dependent clauses always need to be attached to an independent clause (they’re too weak to stand alone).

We’ll talk more about dependent clauses later on, but also see our handout on fragments for a more detailed description of these types of clauses.

Something tricky

Before we move on to the sentence types, you should know a little trick of subjects and verbs: they can double up in the same clause. These are called “compound” subjects or verbs because there are two or more of them in the same clause.

Compound subject (two subjects related to the same verb):

Javier and his colleagues collaborated on the research article.

Compound verb (two verbs related to the same subject):

Javier conducted the experiment and documented the results.

Compound subject with compound verb:

Javier, his colleagues, and their advisor drafted and revised the article several times.

Notice that they don’t overlap. You can tell that it’s only one clause because all of the subjects in one clause come before all of the verbs in the same clause.

Four Basic Patterns

Every sentence pattern below describes a different way to combine clauses. When you are drafting your own papers or when you’re revising them for sentence variety, try to determine how many of these patterns you use. If you favor one particular pattern, your writing might be kind of boring if every sentence has exactly the same pattern. If you find this is true, try to revise a few sentences using a different pattern.

NOTE: Because nouns can fill so many positions in a sentence, it’s easier to analyze sentence patterns if you find the verbs and find the connectors. The most common connectors are listed below with the sentence patterns that use them.

In the descriptions below, S=Subject and V=Verb, and options for arranging the clauses in each sentence pattern given in parentheses. Connecting words and the associated punctuation are highlighted in brown. Notice how the punctuation changes with each arrangement.

Pattern 1: Simple Sentence

One independent clause (SV.)

Mr. Potato Head eats monkeys.

Try this: Look for sentences in your own text that have only one clause. Mark them with a certain color so they stand out.

Pattern 2: Compound Sentence

Two or more independent clauses. They can be arranged in these ways: (SV, and SV.) or (SV; however, SV.) Connectors with a comma, the FANBOYS: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so (See our handout on commas for more info.) Connectors with a semicolon and comma: however, moreover, nevertheless, nonetheless, therefore

Example compound sentences:

Mr. Potato Head eats them for breakfast every day, but I don’t see the attraction.

Eating them makes him happy; however, he can’t persuade me.

- Scan your own text to find the compound connectors listed above. Circle them.

- Find the verb and the subject of the clauses on both sides of the connectors.

- Highlight your compound sentences with a color that’s different from the one you used to mark your simple sentences.

Pattern 3: Complex Sentence

One independent clause PLUS one or more dependent clauses. They can be arranged in these ways: (SV because SV.) or (Because SV, SV.) or (S, because SV, V.)

Connectors are always at the beginning of the dependent clause. They show how the dependent clause is related to the independent clause. This list shows different types of relationships along with the connectors that indicate those relationships:

- Cause/Effect: because, since, so that

- Comparison/Contrast: although, even though, though, whereas, while

- Place/Manner: where, wherever, how, however

- Possibility/Conditions: if, whether, unless

- Relation: that, which, who, whom

- Time: after, as, before, since, when, whenever, while, until

Examples of complex sentences:

He recommends them highly because they taste like chicken when they are hot.

Although chicken always appeals to me, I still feel skeptical about monkey.

Mrs. Potato Head, because she loves us so much, has offered to make her special monkey souffle for us.

She can cook it however she wants.

Although I am curious, I am still skeptical.

- Scan your own text to find the complex connectors listed above. Circle them.

- Find the verb and the subject of the clauses that goes with each connector, remembering that the dependent clause might be in between the subject and verb of the independent clause, as shown in the arrangement options above.

- Highlight your complex sentences with a color that’s different from the one you used to mark your simple sentences.

Pattern 4: Compound-Complex Sentence

Two or more independent clauses PLUS one or more dependent clauses. They can be arranged in these ways: (SV, and SV because SV.) or (Because SV, SV, but SV.)

Connectors: Connectors listed under Patterns 2 & 3 are used here. Find the connectors, then find the verbs and subjects that are part of each clause.

Mr. Potato Head said that he would share the secret recipe; however, if he does, Mrs. Potato Head will feed him to the piranhas, so we are both safer and happier if I don’t eat monkeys or steal recipes.

Try this: Use a fourth color to highlight the compound-complex sentences in your text (the ones with at least two independent and at least one dependent clauses).

Look at the balance of the four different colors. Do you see one color standing out? Do you notice one missing entirely? If so, examine your text carefully while you ask these questions:

- Could you separate some of the more complex sentences?

- Could you combine some of the shorter sentences?

- Can you use different arrangement options for each of the sentence patterns?

- Can you use different connectors if you change the order of the clauses?

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

A clear, arguable thesis will tell your readers where you are going to end up, but it can also help you figure out how to get them there. Put your thesis at the top of a blank page and then make a list of the points you will need to make to argue that thesis effectively.

For example, consider this example from the thesis handout : While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake”(54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well”(51) is less convincing.

To argue this thesis, the author needs to do the following:

- Show what is persuasive about Sandel’s claims about the problems with striving for perfection.

- Show what is not convincing about Sandel’s claim that we can clearly distinguish between medically necessary enhancements and other enhancements.

Once you have broken down your thesis into main claims, you can then think about what sub-claims you will need to make in order to support each of those main claims. That step might look like this:

- Evidence that Sandel provides to support this claim

- Discussion of why this evidence is convincing even in light of potential counterarguments

- Discussion of cases when medically necessary enhancement and non-medical enhancement cannot be easily distinguished

- Analysis of what those cases mean for Sandel’s argument

- Consideration of counterarguments (what Sandel might say in response to this section of your argument)

Each argument you will make in an essay will be different, but this strategy will often be a useful first step in figuring out the path of your argument.

Strategy #2: Use subheadings, even if you remove them later

Scientific papers generally include standard subheadings to delineate different sections of the paper, including “introduction,” “methods,” and “discussion.” Even when you are not required to use subheadings, it can be helpful to put them into an early draft to help you see what you’ve written and to begin to think about how your ideas fit together. You can do this by typing subheadings above the sections of your draft.

If you’re having trouble figuring out how your ideas fit together, try beginning with informal subheadings like these:

- Introduction

- Explain the author’s main point

- Show why this main point doesn’t hold up when we consider this other example

- Explain the implications of what I’ve shown for our understanding of the author

- Show how that changes our understanding of the topic

For longer papers, you may decide to include subheadings to guide your reader through your argument. In those cases, you would need to revise your informal subheadings to be more useful for your readers. For example, if you have initially written in something like “explain the author’s main point,” your final subheading might be something like “Sandel’s main argument” or “Sandel’s opposition to genetic enhancement.” In other cases, once you have the key pieces of your argument in place, you will be able to remove the subheadings.

Strategy #3: Create a reverse outline from your draft

While you may have learned to outline a paper before writing a draft, this step is often difficult because our ideas develop as we write. In some cases, it can be more helpful to write a draft in which you get all of your ideas out and then do a “reverse outline” of what you’ve already written. This doesn’t have to be formal; you can just make a list of the point in each paragraph of your draft and then ask these questions:

- Are those points in an order that makes sense to you?

- Are there gaps in your argument?

- Do the topic sentences of the paragraphs clearly state these main points?

- Do you have more than one paragraph that focuses on the same point? If so, do you need both paragraphs?

- Do you have some paragraphs that include too many points? If so, would it make more sense to split them up?

- Do you make points near the end of the draft that would be more effective earlier in your paper?

- Are there points missing from this draft?

- picture_as_pdf Tips for Organizing Your Essay

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue Online Writing Lab

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Online Writing Lab at Purdue University houses writing resources and instructional material, and we provide these as a free service of the Writing Lab at Purdue. Students, members of the community, and users worldwide will find information to assist with many writing projects. Teachers and trainers may use this material for in-class and out-of-class instruction.

The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives. The Purdue OWL offers global support through online reference materials and services.

A Message From the Assistant Director of Content Development

The Purdue OWL® is committed to supporting students, instructors, and writers by offering a wide range of resources that are developed and revised with them in mind. To do this, the OWL team is always exploring possibilties for a better design, allowing accessibility and user experience to guide our process. As the OWL undergoes some changes, we welcome your feedback and suggestions by email at any time.

Please don't hesitate to contact us via our contact page if you have any questions or comments.

All the best,

Social Media

Facebook twitter.

Sentence Structure Examples: Rules & Tips for Writers

Sentence structure is fundamental to writing clear and engaging content. Varying sentence structure can enhance the rhythm of your writing and keep the reader engaged. Mostly happens if anyone says, Write an introduction for an essay ; people become terrified, thinking how we are going to do it? Here below, you will come to have a deep understanding of it.

Sentence structure refers to the way words and phrases are arranged to form a complete sentence. It determines how the elements of a sentence fit together, including where subjects, verbs, and objects are placed and how clauses are organized.

What is sentence structure?

Sentence structure refers to the way words and phrases are arranged to form sentences in a language. It involves the order and organization of elements such as subjects, verbs, objects, and modifiers within a sentence. Proper sentence structure is essential for clear communication, allowing speakers and writers to convey their ideas effectively and ensuring that listeners and readers can understand those ideas.

There are several key components to understanding sentence structure:

- Subject : The part of the sentence that tells who or what the sentence is about.

- Predicate : The part of the sentence that tells what the subject does or is. It includes the verb and often an object or complement.

- Object : This can be a direct object (receiving the action of the verb directly) or an indirect object (to whom or for whom the action is done).

- Modifiers : These are words, phrases, or clauses that provide additional information about other elements in the sentence, often describing or clarifying.

In English, the basic and most common sentence structure is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO). However, sentences can be more complex and can include multiple clauses, both dependent and independent, creating compound, complex, or compound-complex sentences. Understanding and using various sentence structures can enhance writing, providing clarity, variety, and interest.